Biological hazards refer to biological agents that pose a threat to the human health. Biological agents, including samples of a microorganism, viruses, or toxins (from a biological source) are used in bioterrorism to spread infectious diseases. Reference Masci and Bass1,Reference Sivanpillai2 Biological hazards can be classified as natural, accidental, or intentional. Reference Narayanan, Lacy and Cruz3 Natural biological hazards have caused epidemics, pandemics, and emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, resulting in a substantial rate of morbidity and mortality. Reference Buliva, Elhakim and Minh4 The burden of infectious diseases can be challenging because such diseases occur at different time scales and are influenced by demographic, epidemiological, and aging factors. Reference van Lier, Havelaar and Nanda5 Also, antimicrobial resistance is rising globally. It poses a significant threat of growing concern to human health and is the greatest challenge for countries around the world. Reference Aslam, Wang and Arshad6,Reference Tacconelli and Pezzani7 Intentional biological hazards, also known as biowarfare and bioterrorism, can be broadly defined as the deliberate use of biological agents against civilian populations to intentionally produce disease or intoxication. Reference Artenstein8-Reference Mondy, Cardenas and Avila10 Examples of accidental biological hazards are occupational exposure to biological agents and accidents in laboratories. Laboratory workers are exposed to biological hazards during collecting or testing biological materials and samples. In addition, physicians, nurses, and other health workers may be exposed when they perform medical activities such as surgical or invasive procedures. Reference Sacadura-Leite, Mendonça-Galaio, Shapovalova, Pereira, Rocha and Sousa-Uva11

The most common characteristics of biological hazards include biological weapons that are easily available and cheaper to produce and potentially could have destructive power. Also, even the low-scale use of biological weapons, as was observed in the anthrax attacks, can cause large-scale social, mental, and economic effects. Reference Ryan12 Biological hazards can cause great mortality, morbidity, and hospitalization with great impact on the community. Therefore, biological hazards have become one of the most serious public health threats to the health system, especially hospitals. Reference Fraser and Fisher13,Reference Patvivatsiri14

The arrival of the first Ebola patient in the emergency department of a hospital in metropolitan Dallas generated considerable media attention and fear of outbreak in the US. Rate of emergency department visits increased significantly and remained elevated for several months. Reference Molinari, LeBlanc and Stephens15 After the September 11, 2001 attacks, the United States experienced anthrax attacks as acts of bioterrorism. Letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to homes, the Senate, and major newsrooms, resulting in morbidity and mortality and effectively disrupting community and health systems. Reference Bush and Perez16,Reference Marmagas, King and Chuk17 The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China and then around the world created a serious challenge for hospitals due to its high human-to-human transmission. Reference Rothan and Byrareddy18

Health systems and hospitals are the first responders to biological threats, and they play a critical role. Therefore, large quantities of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies in hospitals may be required. Reference Fraser and Fisher13,Reference Treat, Williams, Furbee, Manley, Russell and Stamper19 Because of increasing worldwide threats of biological hazards, hospitals confront the challenge of implementing responses and providing medical services to such events that may require immediate decontamination, treatment, and care of large numbers of casualties, as well as increased attention on the protection and safety of personnel. Reference Treat, Williams, Furbee, Manley, Russell and Stamper19 Hospital preparedness measures are an essential component of disaster preparedness for mass casualty events, and they need to address all hazards, including biological hazards such as biowarfare agents, bioterrorism, emerging and reemerging infectious disease outbreaks, and pandemics. Reference Rebmann20,Reference Rebmann21 These measures offer practical guidance for hospitals.

Due to the important role of hospital preparedness, especially in response to biological hazards, it is important to focus on hospital and personnel preparation and in detail the activities and guidelines they must follow. In this regard, the previously performed studies mainly have focused on the importance of programs and plans. Some studies have shown that a large proportion of hospitals around the world are poorly prepared to confront biological hazards and inappropriately respond to massive casualty of any kind, either in their capacity to care for large numbers of victims or in their ability to provide care in coordination with external organizations and hospitals. Reference Case, West and McHugh22-Reference Wetter, Daniell and Treser24 Therefore, the objective of the present study was to perform a systematic review to summarize and review the existing models, programs, plans, or protocols for hospital preparedness against biological hazards. The output and results of the present study may help hospital managers, authorities in health systems, and policy-makers to promote hospital preparedness for appropriate response to biological hazards.

METHODS

Definitional Concepts

In this study, we conducted a systematic review of articles and documents related to hospital preparedness for biological hazards. This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman25

Data Sources and Searches

This systematic review was performed to review available published articles, documents, reports, and guidelines. The key terms were identified and selected by consulting experts in disaster management and biological hazards, and the search strategy was developed in partnership with a research team and medical information specialists. A comprehensive literature search was performed using scientific databases and gray literature from March 1950 to June 2019, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Databases and search strategy

After conducting a comprehensive search for the relevant articles, reference lists of the retrieved articles were searched to obtain unpublished relevant data. We used EndNote version X9 to manage the search library, screen for duplicate articles, and extract irrelevant articles.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows.

Inclusion criteria:

1. Articles or documents addresses the hospitals preparedness in disasters.

2. Consideration of at least one of the types of the biological hazards including natural and intentional.

3. The full text of articles was available and free.

4. The study was published in English language.

Exclusion criteria:

1. Articles published in a language other than English.

2. Literature that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria.

3. Studies that investigated the preparedness measures of locations other than hospitals.

Study Selection

In the first step, duplicate articles were eliminated via EndNote version X9. Articles were screened through assessing the titles and abstracts for eligibility by 2 reviewers independently. The full text of the retrieved articles was reviewed carefully and critically by the reviewers.

Data Extraction

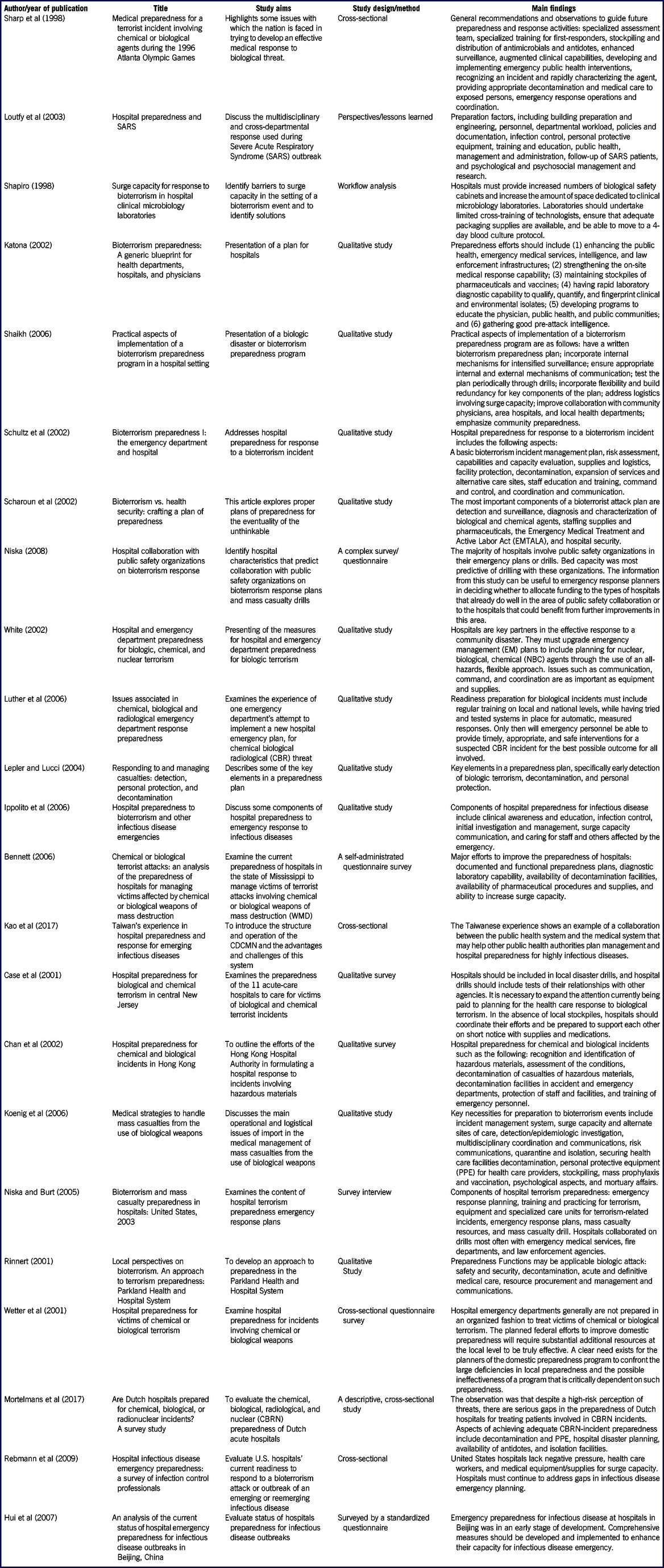

A form was used to extract the data and included the following factors: (1) name of the first author, (2) year of publication, (3) title, (4) study design, (5) aim of the study, and (6) main findings (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Characteristics of the included studies

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

Standard quality assessment of the retrieved articles was conducted by Critical Appraisal Skills Programmed (CASP) 26 and STROBE tools and checklists. Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke27 Two authors reviewed each article independently for the risk of bias. Any disagreements were resolved though discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of outcomes and the number of repeated or non-independent samples, the most appropriate approach for qualitative meta-synthesis is descriptive and contextual analysis of the collected data. Reference Sandelowski and Barroso28,Reference Thomas and Harden29 A thematic synthesis approach was used to gather information and identify all themes. The inductive analysis was performed by the 2 authors in 3 stages: (1) extraction of findings and coding of findings for each study; (2) grouping of findings (codes) according to their topical similarity to determine whether findings confirm, extend, or refute each other; and (3) abstraction of findings (analyzing the grouped findings to identify additional patterns, overlaps, comparisons, and redundancies to form a set of concise statements that capture the content of findings). The initial synthesis of studies was conducted separately for each of the included article formats. One author extracted data from the included studies into an extraction datasheet. The accuracy and completeness of the extracted data were checked by 2 other authors.

RESULTS

5251 articles from databases and 6 articles from other sources were identified. In total, 5257 articles were found in the primary literature search. First, 879 duplicated articles were removed by the first author. Then, 4378 articles were screened by reviewing their titles and abstracts and 4262 articles were deleted, so 116 articles remained. In the next stage, the full texts of the 116 articles were assessed and read. Finally, 23 articles met the criteria for entering the process of systematic review. Figure 1 illustrates the study identification and selection process.

FIGURE 1 Flow chart of study identification and selection process

Administrative and Management Hospital Preparedness Measures

Hospital Preparedness Plans

Disaster preparedness can be defined as planning, infrastructure, knowledge, capabilities, and education comprising the main elements of maintaining preparedness. Reference Adini, Goldberg, Laor, Cohen, Zadok and Bar-Dayan30 Appropriate preparedness can only be obtained through hospital preparedness plans. Reference Kaji, Koenig and Lewis31 Lack of preparedness plans in hospital negatively impacts the response activities of hospitals, such as managing victims and patients exposed to biological agents. Reference Bennett32 Plans must also establish orientation and training programs for staff who participate in response operations that address roles and responsibilities, information and skills required, monitoring of staff knowledge, skills, competencies, participation, incident reporting, and program evaluation. Reference Schultz, Mothershead and Field33 The plan should address the physical infrastructure needs of the biological hazards response plan, such as biocontainment areas in the emergency department, or the hot zones and isolation units. Reference Shaikh34 The hot zone is the area in which the incident occurred and in which contamination exists. All individuals entering the hot zone must wear the appropriate levels of PPE and be decontaminated before leaving. Reference McIsaac35 Components of hospital preparedness plans for biological hazards include procedures for activation, notification, structure of the command and response communications and media relations, evacuation and establishment of alternate care sites, personnel and facility protection, and recovery issues. Reference Schultz, Mothershead and Field33,Reference White36

Risk Assessments

Risk assessments include evaluation of hazards or potential threats, profiling of hazards maps, capacity assessment and estimation of potential human and economic losses based on the exposure and vulnerability of community or hospital to the threats and incidents. Reference Jonidi Jafari, Baba and Dowlati37 Assessments should be conducted in structural, nonstructural, and functional aspects. 38,Reference Ippolito, Puro and Heptonstall39

Vulnerabilities of hospital should be forecasted, and the risk assessment should include the entire service area of the hospital. Reference Schultz, Mothershead and Field33 Hospitals and laboratories are recommended to consider biosafety and biosecurity issues and to prepare their response plans based on the most likely risks and categorization of biological agent groups. Risk assessment identifies the severity of infection, the potential for transmission to exposed people and to the wider community or environment, the possibility of patient admissions, and availability of effective prophylaxes and treatments. Reference Ippolito, Puro and Heptonstall39

Hospital Incident Command System (HICS)

A biological hazards will need a developed incident management and command system to integrate the different response functions. Reference Schultz, Mothershead and Field33 An important strategy for organizing hospital staff for mass casualties resulting from exposure to a biological agent is to implement a Hospital Incident Command System (HICS). HICS provides a common disaster language, a representative authority or a commander, and a flexible infrastructure framework for the disaster response that can expand as needed, depending on the size and complexity of the incident. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40 According to the situation and the type of hazards, the commander may choose to activate a medical-technical specialist officer unit with an infectious disease physician on staff. In situations involving a hazardous material (HazMat), such as internal or external biological agent release, the commander activates the HazMat branch subgroup of the operations section. The HazMat branch will have the personnel and equipment to address agent recognition, monitoring, and victim decontamination. 41,Reference Vastag42

Hospital Collaboration

Biological hazards pose unique challenges to hospitals because they may go unrecognized for days, with the possibility of victims and patients admitting to different hospitals. Collaboration and information sharing with other hospitals and community physicians could provide the possibility of identifying suspected exposure to the biological agent. The local health department would obtain information from hospitals as part of the laboratory or syndromic surveillance system. Mutually, the hospitals would benefit from the health department’s information regarding a suspected case of biologic hazards or bioterrorist agent, in a timely manner. Reference Shaikh34,Reference Vastag42 Hospitals were required to collaborate with the following:

Local public health system and the medical system

Law enforcement

Emergency medical services (EMS)

HazMat teams

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the local health department

Environment agency

Water authority

Military medicine experts

Physicians and fire departmentsReference Kao, Ko, Guo, Chen and Chou43-Reference Niska45

During disasters and emergencies, hospitals must collaborate about surge capacity in equipment and supplies, deployment of physicians and other hospital staff, and use of spaces. Reference Gursky46

Health Risk Communications

Risk communication encompasses provision of exact, timely, complete, and easily understood information to the community about the following:

The incident

Control and mitigation effort

Safety self-protection

Provision of information to hospital staff about diagnosis

Interventions after and post exposure

Communication with families and others close to those affected by the emergency

Communication with the news media

Communication within and between all those involved in emergency managementReference Ippolito, Puro and Heptonstall39

Internal hospital communications involve the need to communicate with the following parties:

Staff concerning the nature of the event

Implement the hospital disaster plan

Activate the staff “call back” and rotation system to ensure adequate manpower

Provide critical incident stress debriefing for both personnel and their familiesReference Rinnert47

During biological incidents, effective risk communication will play an important role in providing essential information to the public and hospital staff. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40 Inappropriate communication could result in rumors and incorrect information spreading, which may result in overwhelming the hospital, especially emergency rooms, because of surge of patients and inappropriate induced demand. Reference Scharoun, van Caulil and Liberman48

Specialized Hospital Preparedness Measures

Early Detection and Surveillance System

The aim of a syndromic surveillance system is to provide an early warning for the onset of an epidemic, as well as tracking and quick recognition of epidemics, which allow more effective health care responses, especially in the event of a bioterrorist attack. Reference Buehler, Whitney, Smith, Prietula, Stanton and Isakov49 Early detection is essential for preparedness against a biological hazard, including the provision of chemoprophylaxis, early proper medical therapy and vaccination to improve the chance of survival, and also public health measures such as quarantine and isolation. 50,Reference Lepler and Lucci51 It is critical to recognize the symptoms of a bioterrorist agent and differentiate it from symptoms common to other disease. Reference Scharoun, van Caulil and Liberman48 Specifically, surveillance systems can reduce the infection with a pathogen in order to detect the disease or an outbreak caused by a biological agent and improve its early detection. Reference Buehler, Berkelman, Hartley and Peters52 Patients infected with a biological agent may initially appear to have a routine medical illness. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40 Syndromic surveillance uses health-related data that precede diagnosis and signal a sufficient probability of a case or an outbreak to warrant hospital response. Reference Romao, Martins, Germano, Cardoso, Cardoso and Freitas53

Diagnostic Laboratories

During biological hazards, hospitals should strengthen their diagnostic laboratory capability for rapid detection and identification of biological agents. For example, blood culture bottles and possibly continuous-monitoring blood culture instruments should be stockpiled. In the case of a surge of patients’ specimens, hospital laboratories should have a limited number of level II Biological Safety Cabinets (BSC), with isolation and negative pressure rooms. Reference Gilchrist54 Therefore, assigning additional space to diagnostic laboratories and modifying the existing airflow in rooms are essential. Reference Shapiro55 Laboratory experts and technicians should be trained in bioterrorism, because they are one of the first responders to detect the presence of an unusual biological agent or disease process. Procedures need to be in place for the safe handling and transport of specimens to specialized laboratories. Reference White36

Personnel and Facilities Protection

Most of the time, infected patients and victims exposed to biological agents are not decontaminated upon their arrival to the hospitals. Therefore, the staff and facilities may be exposed to the biological agents. Reference Chan, Yeung and Tang56 Hospital staff involved in direct handling of infectious patients should be protected by appropriate PPE. Also, hospital personnel should be trained and adapted to the use of PPE. Reference Mortelmans, Gaakeer, Dieltiens, Anseeuw and Sabbe23,Reference Chan, Yeung and Tang56,Reference Loutfy, Wallington and Rutledge57 PPE includes masks, gloves, protective clothing, eye shields, face shields, shoe covers, and also powered air purifying respirator (PAPR) devices. Reference Wetter, Daniell and Treser24,Reference Luther, Lenson and Reed58 Ideally, for agents transmitted by respiratory droplets, an N-95 mask would theoretically be adequate. In an ideal situation, a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter mask might be more appropriate. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40

Mass Prophylaxis and Vaccination

Some diseases caused by biological agents, such as anthrax, tularemia, and plague, can be prevented through adequate antibiotic prophylaxis. The aim of any hospital prophylaxis plan is to provide a unit in order to maintain staff such as emergency department and laboratory personnel who may have early exposure to the biological agent during and after a bioterrorism event. Staff and their family would get prophylaxis only if they were considered to have likely been exposed to biological agents. Reference Sharp, Brennan, Keim, Williams, Eitzen and Lillibridge59 Hospital staff may not want to come to the hospital, particularly without some prophylaxes. Reference Katona44,Reference Coelho and García Díez60 Thus, pharmaceuticals and vaccines must be distributed quickly and efficiently to first responders before disease transmission to others. Reference Katona44 Post-exposure vaccination and prophylaxes are essential measures to reduce morbidity and mortality after biological hazards. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40

Patients and Facility Decontamination

With biological hazards, such as overt release of a biological weapon, decontamination will play a role in patient management. The presence of decontamination facilities outside and downwind of a hospital is necessary. Reference Macintyre, Christopher and Eitzen61 For biological agents such as anthrax spores, which can survive in the environment for decades, decontamination has been recommended. Reference Inglesby, O’Toole and Henderson62,Reference Lepler and Lucci51 Specific hospital personnel who perform triage and stabilizing should be trained to perform decontamination activities. Reference Rinnert47 Decontamination facilities should consider shelter, warm water, and clothing for operations in winter. Reference Case, West and McHugh22 Use of external decontamination facilities that can be activated quickly, barriers to provide patient privacy, and the use of warm water and soap should be sufficient to remove most biological agents. Reference Schultz, Mothershead and Field33 Internal decontamination stations protect against warm and cold weather but have the disadvantage of permitting contaminated patients and victims to enter the hospital. Reference Cole63

Education and Exercise

All hospital staff should be trained and educated on all aspects of biological hazards. Reference Torani, Majd, Maroufi, Dowlati and Sheikhi64 The main components of an education plan include agent detection and recognition, hospital incident command structure, response support, personnel safety and protection, decontamination, isolation and quarantine, infection-control policies and procedures, triage, prophylaxis activities, psychological effect management, risk communication, treatment, and fatality management. Reference Luther, Lenson and Reed58 Hospitals should begin by testing their preparedness plan with regular exercises to assess performance and to ensure correct staff response. Reference Chan, Yeung and Tang56 Exercises should be performed to recognize weakness; enhance teamwork; improve coordination; and promote skills, knowledge, and competencies. Reference Shaikh34,Reference Klein, Brandenburg, Atas and Maher65 Hospital exercises might be crafted to reflect the hospital preparedness status for biological attacks and those for severe epidemics and pandemics, thus encouraging the hospital to review its status. Reference Niska and Burt66

Psychological Effects Management

A key component of any biological hazards preparedness plan will be providing psychological care to exposed victims, involved hospital personnel, and affected communities. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40 Psychological and psychosocial support for both patients and the hospital staff are necessary during the biological hazards. Staff are affected by the fear of contracting infectious disease and the anxiety caused by their families’, friends’, and colleagues’ disease. Patients experience stress because of their quarantine and isolation, fear for their lives, guilt, anger, anxiety, and depression. Psychological teams in hospitals (including social workers, security personnel, psychiatric nurses, psychiatrists, and infectious disease specialists) can developed a plan for biological hazards in relationship with hospitals’ psychiatry departments to manage and care for the psychological impact on patients and hospital staff. Reference Loutfy, Wallington and Rutledge57

Biological Hazard Specialized Team

One unique approach to biological hazards is developing special teams. Reference Loutfy, Wallington and Rutledge57 In general, multidisciplinary teams developed and organized for response should include disaster management experts, physical plant/engineering, facilities maintenance, bioengineering, occupational physicians, emergency physicians, emergency nurses, toxicologists, infectious disease physicians, epidemiologists, infection-control experts, security personals, safety officers, hospital administrators, facility engineers, mental health practitioners, volunteer services coordinators, pharmacists, and health educators. Reference Shaikh34,Reference White36,Reference Rinnert47

Infection Control Services and Isolation

Effective infection control services are important in biological agent control and may operationalize victim and patient isolation needs. Reference Rinnert47,Reference Rebmann, Carrico and English67 During a biological hazard, the safety officer should collaborate with medical-technical specialists (biological/infectious disease) to determine what information and protective measures are required. 41,Reference Loutfy, Wallington and Rutledge57 Major infection control practices for biological hazards include checking the availability of PPE, hand hygiene, sharps safety and disposal arrangements, removing and disposing of the PPE, arrangements for cleaning, and ensuring environmental hygiene. Also, infection control planning for biological hazards should identify and consider the extra space, such as negative airflow rooms suitable for airborne infection and respiratory systems of available isolation or single rooms. Reference Case, West and McHugh22 Isolation rooms and rooms under negative pressure should be established in a suitable location and in sufficient numbers, as it should be the case for a plan to increase this capacity through portable high efficiency particulate air devices. Reference White36

Logistical Hospital Preparedness Measures

Increase Capability

An ability to increase capability is a major issue for hospitals in disaster and overcrowding conditions. Reference Rebmann, Carrico and English67 Increasing capability, or the ability to rapidly respond to a sudden and dramatic increase in needs, has been addressed as one of the components of preparedness so hospitals can effectively respond to disasters. Reference Shapiro55 Increasing capability comprises 3 components: staff, stuff, and structure. Structure consists of both the management infrastructure as well as the physical space required to provide for infectious patients’ care. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40,Reference Koenig, Cone, Burstein and Camargo68 Hospitals must have a preparedness plan to increase capability for response to biological hazards, as the potential large number of victims requiring medical care would soon overwhelm hospital facilities. Plans to expand the hospital capability internally and then to alternate care sites can help mitigate the impact. Expansion requirements include personnel, supplies and equipment, and space. Reference Bennett32,Reference White36

Hospital Personnel and Volunteer Forces

Developing hospital personnel to meet the rapidly increasing demand for services and staff in the aftermath of a biological hazard may be one of the most challenging aspects of preparedness to respond to biological hazards. Some staff members may themselves be infected by exposure to the biological agents or may fail to come to work for a variety of reasons, such as caring for their families. A list of alternate personnel should be prepared and a recall system for mobilizing adequate on-call personnel should be developed. Sufficient numbers of hospital staff include infectious disease physicians, emergency medicine, surgeons, intensivists, nurses, pharmacists, radiology technicians, infection control, clinical laboratory experts, and respiratory therapy. These types of staff will be most useful in addressing an infectious disease outbreak. Reference Rebmann20,Reference Rinnert47 Possible sources of extra personnel could include staff from other hospitals, closed clinics, or outpatient surgery departments; hospital retirees; medical, nursing, and allied healthcare students; and volunteer forces. Reference White36 One solution for the shortage of specialized hospital staff could be pre-identified health care volunteers within or outside the affected community. Reference Salmani, Seyedin, Ardalan and Farajkhoda69 These individuals will require proper education and orientation and may be asked to perform beyond their levels of competency under supervision. Because it is possible that terrorists may seek to volunteer, these persons must be selected cautiously. Reference White36

Supplies and Equipment

A main consideration in the preparedness for biologic hazards is stockpiling of necessary medications, supplies, and equipment. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40,Reference Hui, Jian-Shi, Xiong, Peng and Da-Long70 Even if hospitals usually have proper and sufficient treatments and pharmaceutical procedures, during biological disasters their supplies (prophylaxis/medications) would be limited. Reference Bennett32,Reference White36 In the case of a biological hazard, casualties are likely to be widespread and medications may be in demand from multiple sources. Reference Koenig, Kahn and Schultz40,Reference Barbisch71 Hospitals must seek other possible sources of equipment, including neighboring medical facilities, pharmacies, medical suppliers, and veterinarians. Reference Schultz, Mothershead and Field33 These plans include increasing the ability of the hospital to quickly prepare large quantities of antibiotics, vaccines, and antitoxins; equipment to provide standard precautions; PPE; disposable clothing for decontaminated patients; ventilators and biohazard bags; HEPA filters, supplies routinely required for all patients, such as bed pans, linens, and other materials in excess of anticipated demand. Reference Schultz, Mothershead and Field33,Reference Katona44,Reference Shapiro55 Ventilators are one of type of equipment that is likely to be in short supply after a biological hazard, so purchasing portable, disposable ventilators is critical. Reference White36

Physical Space

One strategy for dealing with mass casualties from biological hazards is to use alternate sites of care. Reference Rebmann20 Spaces that may need early expansion include the emergency department, infectious department, inpatient units, the morgue, laundry, and possibly decontamination facilities in the case of an announced biological agent’s release. Establishing a secondary emergency department in another area of the hospital or adjacent to primary units permits increased hospital capacity. The number of active hospital beds can be increased by canceling or rescheduling of elective and unnecessary cases for surgery. Reference White36 Since biological hazards last for weeks, hospitals need to plan conjointly to use available land for temporary field hospitals, and then medical facilities can transfer patients there. Reference White36 Prearranged agreements for access to spaces such as hotels, care facilities, hospice, medical universities, schools, churches, mosques, public halls, and community centers may also expand the capacity of a hospital. Reference White36,Reference Rinnert47

Hospital Security

Hospitals may become terrorist targets especially during disasters and when the hospitals are overcrowded. Reference White36 Hence, hospital officials must improve their security personnel in an effort to provide crowd control and protection for staff and patients. Reference Bennett32 Patients should be isolated or quarantined for prevention of spread of infection. Patients must be restricted exit from isolation by security personnel. Reserve security personnel are needed at hospital entrances, triage points, emergency departments, and isolation units to prevent unauthorized access. Reporting the suspected terrorist events should begin with local law enforcement, police, and local health departments. Reference White36 During biological hazards, security personnel must be in place to control the flow of human gathering inside and around the hospital. In addition, security must monitor all vehicular traffic and assure that ambulances are able to transport patients rapidly. Reference Scharoun, van Caulil and Liberman48

DISCUSSION

Preparedness refers to actions taken to prepare for and mitigate the impact and proper response of disasters. The aim of disaster preparedness is to design a practical and coordinated plan for the hospital to ensure an effective response during disasters. Hospital disaster preparedness is an ongoing process resulting from a wide range of preparation and promotional activities. It necessitates the contributions of different external related organizations and all departments of the hospital. Major elements of preparedness include planning, early warning systems, education, and exercise. Reference Krajewski, Sztajnkrycer and Baez72 A hospital has an important and critical role in reducing mortality and morbidity due to disasters. The current systematic review synthesizes hospital preparedness measures to biological hazards. Hospital preparedness plans mainly are based on an all-hazard approach. Due to the consequences of biological hazards, having a specific plan that focuses on biological hazards for hospitals is crucial. Some studies evaluated the status of hospital preparedness during biological hazards. Based on the reported results of these studies, hospitals generally were prepared neither to manage biological hazards nor to protect the victims and personnel. Reference Mortelmans, Gaakeer, Dieltiens, Anseeuw and Sabbe23,Reference Wetter, Daniell and Treser24

The hospital preparedness plan for biological hazards should be in accordance with the comprehensive hospital disaster management plans and policies of the health system. Various studies have reported different measures and activities to prepare hospitals against biological hazards. Based on the findings of this systematic review, preparedness measures for biological hazards include administrative, specialized, and logistical issues. A comprehensive and inclusive hospital preparedness plan for biological hazards should consider basic and essential components, such as surge capacity, risk assessment, monitoring threats and rapid identification, staff, and patient perception. From administrative and management perspectives, activities such as planning for hospital preparedness for biological hazards, establishing and development of HICS, hospital collaboration with external agencies, health risk communications, effective education, and practical exercises and risk assessments are essential for preparation for biological hazards. Specialized issues for biological hazards include early detection and surveillance systems, diagnostic laboratories, psychological and psychosocial management, infection control services and isolation, personnel and facilities protection, patient and facility decontamination, and establishment of specialized biological teams. Logistical measures include increased capability, supplies and equipment, physical space, organization hospital personnel, volunteer forces, and hospital security. If hospitals neglect preparedness for biological hazards, they will be challenged during disasters. Also, deficiency in providing the above services may lead to personnel and victims’ health being threatened by a secondary contamination or infectious disease transmission.

Following a mass casualty incident (MCI), the number of patients temporarily exceeds the capability of the hospital to provide optimal care to all victims simultaneously. A sudden mass casualty incident (SMCI) may be the result of a natural disaster such as an earthquake, traffic accidents (road accident, train or plane crash), explosion, or chemical or radiological exposure to hazardous materials. MCIs occur without any warning or alert. Temporary state of insufficiency at the hospital may be due to insufficient number of personnel, space in the emergency department and intensive care unit(s), operating rooms available, drugs and medical supplies (especially ventilators), amount of supplies, and number of blood units available. A hospital plan for a SMCI should include the following:

Strategies to prevent patients flooding the hospital

Surge capacity (staff, space, supplies)

Call-in of additional staff

Organization of treatment areas

Opening and organization of alternate treatment sites with additional equipment and supplies

Hospital risk communication plan

Methods for identification, registration, and tracking of patients

Individualized plan for respiratory therapy

Blood bank

Laboratory

Radiology

Organization of a family information center

Activation of the SMCI plan and hospital response

Triage and principles of medical care during a SMCI

Planning and activation of hospital decontaminationReference Lynn73

The response phase of the SMCI includes various stages, including preparing the triage area, making space in the emergency department, and finding alternate sites of medical care and operating rooms. For response to the incident, the first priority is to prepare the triage area outside the emergency department (ED) and create space inside the ED for the incoming critical patients. Also, it is critical that a hospital has a mature identification and registration system, for multiple simultaneous patients, which could be easily accessed when tracking of patients is required by family members looking for their loved ones. Reference Lynn73

Biologic agent MCI, such as epidemic and pandemic diseases, may occur over a long period of time, such as days, weeks, months, or even years. The enormous amount of infected patients generally do not all arrive at the hospital simultaneously. Reference Lynn73 Comprehensive preparedness plans must therefore address the following:

Screening

Surveillance

Tracking of exposed individuals

Controlled hospital access

Prevention strategies

Isolation and cohorting

PPE use

Vaccination

Antiviral prophylaxis

Modification of environmental controls

Disease-specific admission criteria

Treatment and triage algorithms

Continuity of limited clinical operationsReference Daugherty, Carlson and Perl74

A fully deployed HICS should be beneficial for the hospital during a slowly developing biological epidemic, when a disease outbreak lasts for a few days or months. In these situations, there is enough time to schedule the key personnel listed in the HICS table of organization while verifying that they are actually available. Reference Lynn73 During biological hazards, such as an outbreak of infectious disease, an infections physician, virologist, or microbiologist should be appointed as a specialist consultant in HICS framework.

CONCLUSIONS

In general, biological hazards, such as bioterrorism and disease outbreak, have adverse consequences on human health. Hospitals have an important role in dealing with biological hazards and mitigation of their effects. Hospitals preparedness plans and activities for biological hazards are crucial, and any neglect can hurt personnel and victims during the disaster. In this systematic review, we provided a comprehensive discussion and summarized all aspects of the hospital preparedness for biological hazards. Some hospitals have planned for emergency and disasters, but these plans are based on an all-hazards approach. In conclusion, the findings of the present study could help health managers of hospitals to be prepared. These results may also improve the hospital response to biological hazards according to a situational assessment of the hospitals.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a study conducted by Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.SHMIS97-4-37-14382), Iran. The researchers hereby thank the School of Management & Medical Informatics, Department of Health in Disasters and Emergencies, which are supporting the study.

Funding

Funding for this article was provided by the Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.