Utilization of ambulatory and outpatient services for primary, specialty, and surgical care (hereto referred to as outpatient facilities) has risen in the United States over the last decade. Reference Abrams, Balan-Cohen and Durbha1 Outpatient care refers to medical services and procedures of low acuity that do not require hospital admission or an overnight hospital stay. Subsequently, hospital revenue generated from outpatient services has grown from 30% in 1995 to 47% in 2016. Reference Abrams, Balan-Cohen and Durbha1 As utilization from inpatient to outpatient care has shifted, hospitals and health care systems have also increased their capital investments in outpatient facilities. Reference Abrams, Balan-Cohen and Durbha1 According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the health care industry employs approximately 14 million people, with 76% of those working outside of a traditional hospital setting, such as outpatient facilities. 2

Emergency management in the health care industry has simultaneously evolved over the last few decades, particularly as a result of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City. Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Brewster3,4,Reference Anderson5 Health care emergency management may be defined as the “science of managing complex systems to address emergencies and disasters in health care systems, across all hazards, and through each phase” of emergency management. Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Brewster3 Historically, hospital emergency management focused almost exclusively on mass casualty incidents, but with regulatory forums such as the Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS); policies like Presidential Directives 8 and 21; as well as lessons learned from real-life events, including hurricanes (Katrina 2005; Harvey 2017; Irma 2017), tornadoes (Joplin 2011), and wildfires (California 2017–2018) throughout the country, health care systems have expanded to have a more all-hazards approach for emergency management. 2,Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Brewster3,4 All-hazards denotes the strategy for managing activities in an emergency management program throughout the 4 phases – mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. 4 This expansion and the increased value in health care emergency management demonstrate the “growing perception that enhanced organizational resiliency is needed in the face of likely, enterprise-level hazard impacts.” Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Brewster3

Changes to regulatory requirements for ambulatory facilities have forced hospital clinicians and administrators, as well as other health care providers and suppliers, to change the way they view emergency management for their institutions. The oversight of emergency management is no longer considered an ancillary duty for hospital administrators, but rather a specific, dedicated role and responsibility of a hospital emergency manager. 4 Ensuring continuity of operations has long been the objective of hospital emergency management. “Organizational resiliency,” a phrase defined by the Veterans Health Administration, refers to continuity in both patient care, as well as business operations for health system readiness. Reference Petzel6 Emergency management professionals should take this opportunity to not only meet regulatory requirements, but also further strengthen their programs within the entire health care system enterprise, including primary and specialty care centers.

OBJECTIVES

The very nature of outpatient facilities is such that they are often not co-located – not even the same city, municipality, or sometimes even the same state as their parent systems. This physical geographic separation can lead to outpatient facilities feeling isolated from their parent institutions, particularly during emergency situations. However, it is imperative and mandated that all facets of a health system be prepared and ready to respond both individually, as well as in an enterprise-level response. 4

There is little research that describes outpatient facilities’ role in health care emergency management. Although health care emergency management has grown tremendously in significance, outpatient settings have yet to see the same growth. However, concepts of comprehensive emergency management and the incident command system are important and valuable across all health care system settings, including outpatient facilities. 4,Reference Petzel6 Indeed, the principles of emergency management call for programs to be comprehensive, integrated, collaborative, and coordinated. 4 The rationalization for the development of the CMS Emergency Preparedness Rule was to “establish consistent emergency preparedness requirements for healthcare providers participating in Medicare and Medicaid, increase patient safety during emergencies, and establish a more coordinated response to natural and human-caused disasters,” including ambulatory surgical locations. 7

The purpose of this article is to summarize regulatory requirements for outpatient health care emergency management, describe nuances of outpatient settings, and provide recommendations for how to successfully incorporate outpatient and ambulatory locations into the “Enterprise” model for comprehensive health care emergency management.

METHODS

Defining Regulatory Requirements

The 2009 revision of the Joint Commission Standards included a stand-alone chapter for emergency management. 4 Before this consolidation, emergency management had been addressed under the Joint Commission’s Environment of Care standards, with other directives dispersed throughout other accreditation areas. 4 Much of the progress in emergency management made over nearly 2 decades can be attributed to federal programs and accreditation requirements defined by the Joint Commission. 2

The Joint Commission standards include the adoption of many traditional emergency management principles, including the development of an emergency management program with a multidisciplinary committee, completion of a hazard vulnerability analysis (HVA), interface with community partners, and a comprehensive emergency management plan that covers 6 mission critical functions: (1) communications, (2) resources and asset management, (3) safety and security, (4) staff responsibilities, (5) utilities and facilities, and (6) clinical and support activities. 8 Emergency managers for health care systems are encouraged to take a leadership role in adopting these foundational principles to make compliance with the Joint Commission standards less “problematic.” Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Brewster3

Further regulation changes were made by CMS on September 8, 2016, when the Federal Register posted the final rule for Emergency Preparedness Requirements for Medicare and Medicaid Participating Providers and Suppliers. This regulation went into effect on November 16, 2016, with a requirement that all health care providers and suppliers affected by the rule be compliant 1 year after the effective date, November 15, 2017. 7,9 The final rule focused on ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), home health agencies, hospices, hospitals, and critical access hospitals. The “usual approaches” to emergency management applied and deemed that affected facilities:

-

Perform an HVA relevant to the organization and community

-

Develop an emergency management plan that covers critical areas and supports response to prioritized risks

-

Align staff training with response plans

-

Conduct exercises that test and stress the plan to identify opportunities for improvement

-

Review exercises and responses to actual emergencies to develop informed improvement plans 7,9

Nuances of Outpatient Settings

During emergencies, less urgent, elective services and procedures may need to be postponed; however, with the growth of services provided in outpatient settings, lifesaving and life-sustaining services must continue uninterrupted, including but not limited to dialysis, chemotherapy, medical follow-up to recent hospital discharges, distribution of pharmaceuticals, and so on. 2,Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Brewster3 Situations that negatively impact everyday services can have a serious reputational and financial consequence for a health system. Reference Boyd, Chambers and French10 While the outpatient population may be of lower acuity than their inpatient counterparts, interruption or delay in services may exacerbate illnesses and medical needs, leading to a need for emergency care or even long-term hospital admission. Not all emergencies create a new contingent of patients, but rather stress an organization to maintain optimal health service capabilities. 4

Comprehensive emergency management allows a health system to identify all sites of service delivery, which can assist in the appropriate redistribution of patients from the main hospital during times of surge (such as seasonal high volume or a mass casualty incident). This comprehensive structure is contingent upon a strong collaboration and coordination between hospitals and their outpatient environments. Emergency management has evolved into a push/pull approach, not only having the responsibility to support an outpatient space, but also include it into overall planning as a potential resource in increasing capacity and decreasing demand on the hospital. Medical staff and providers in outpatient settings may also be useful in supplementing staffing needs at their impacted parent-hospitals during surge. By leveraging these staff in a type of personnel pool, challenges with credentialing may be avoided. 2 If health systems expect to leverage outpatient sites and corresponding resources to maintain operations and provide care throughout an emergency, then proactive, integrated, collaborative planning is imperative. Reference Van Vactor11

RESULTS

Enhanced internal coordination to maintain services and maximize capability with available resources is a benefit to comprehensive emergency management. 4 Issues at individual locations are often addressed in isolation from one another, but by instituting a comprehensive program, emergency managers are able to break down silos and barriers between main hospital and outpatient areas. 4 Because of geographic disparity, outpatient locations are naturally first responders when emergencies occur. This reinforces the mantra that “all emergencies are local” – but by taking a systems approach, emergency managers can help strengthen local response capabilities while providing support when the needs of a situation require escalation. 4

Additionally, by including leaders from outpatient facilities in enterprise planning and incorporating elements of daily operations into emergency management, rapid notification to convene clinical and administrative leaders, subject matter experts (SMEs), and key stakeholders to identify issues, address concerns, determine gaps and resource needs, and deploy resources may occur to reduce interruptions and delays in patient care.

DISCUSSION

Recommendations for Comprehensive Emergency Management

Creating a comprehensive emergency management program is achieved by incorporating well-established fundamentals of emergency management throughout a health system enterprise. The key in creating a comprehensive program is forming relationships with clinical and administrative outpatient stakeholders. This partnership is crucial and is the catalyst for any and all future planning activities.

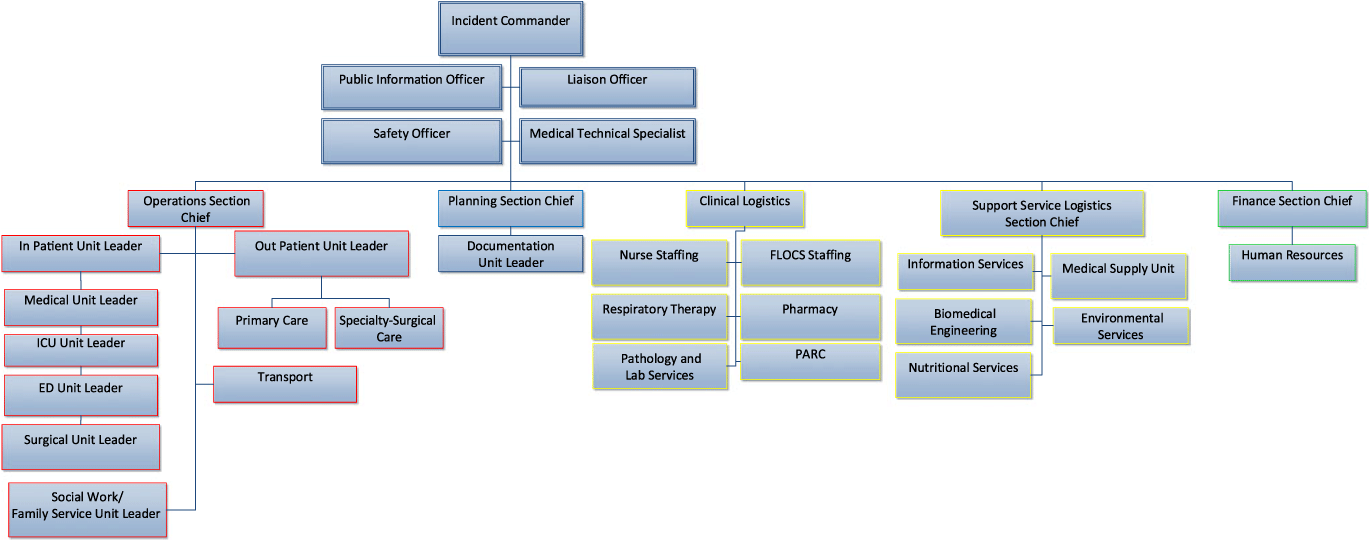

First, leaders from outpatient locations should be given a seat at the table during enterprise emergency management activities, including the hospital’s emergency management committee, to help address organizational disparity and prevent planning in silos. The systems approach should be taken during times of planning by incorporating outpatient leaders in committees and work groups, as well as during response by assigning outpatient leaders as branch directors in the Hospital Incident Command System (Figure 1). As much as possible, elements of daily operations should be incorporated into emergency management by matching roles during response with everyday positions and tasks. For example, consider developing the Incident Management Roll Call to reflect Enterprise briefings, which include outpatient medical and surgical leaders. 4,Reference Alves, Cagliuso and Dunne12 Within a single health system, different areas and facilities may not easily interface, but with effective coordination, emergency managers can help integrate whole systems into a comprehensive emergency management program. 4,Reference Boyd, Chambers and French10

FIGURE 1 Hospital Incident Command System Organizational Chart.

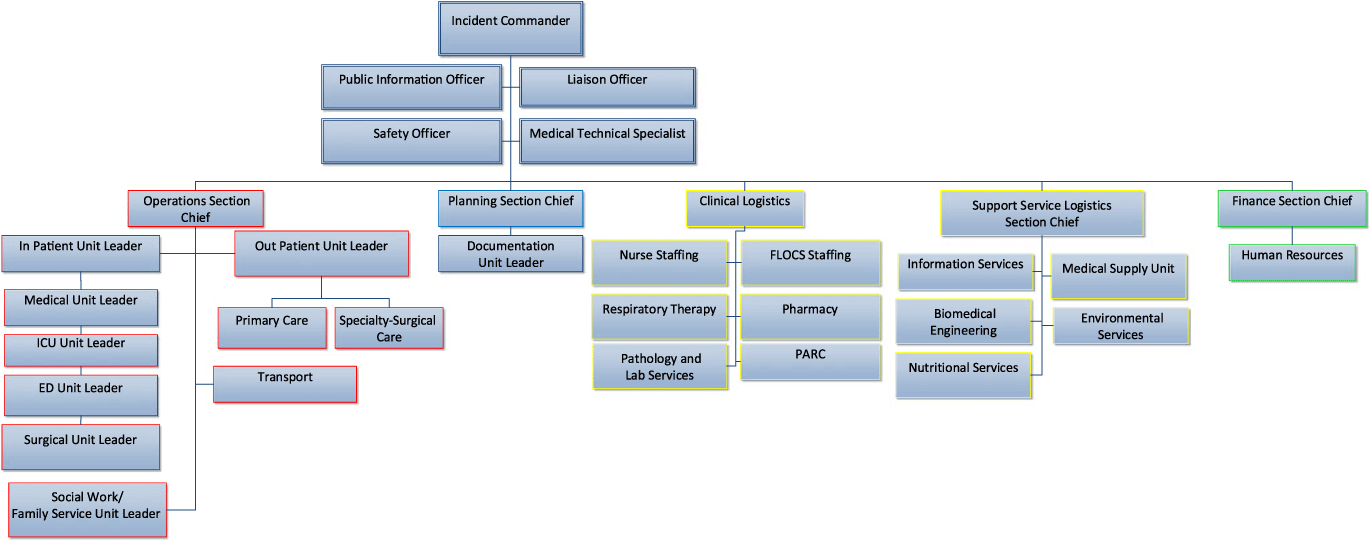

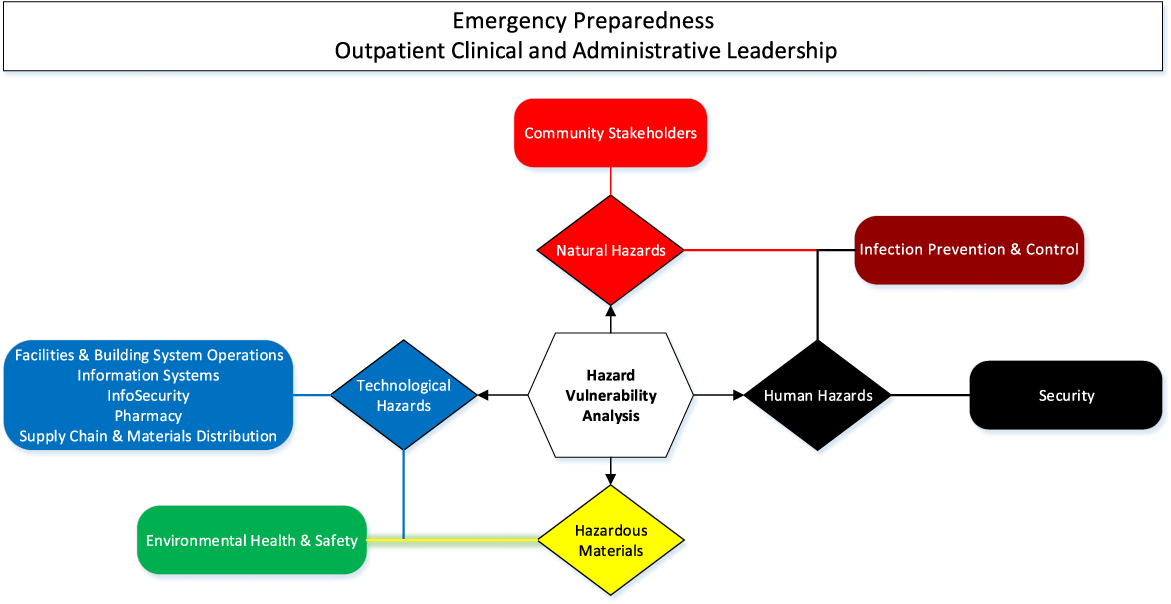

Second, an HVA should be completed by emergency managers in partnership with clinical and administrative leaders for each ASC. HVAs are the key to developing a risk-informed, all-hazards emergency management program, and identifies vulnerabilities and areas to focus on mitigation and preparedness. SMEs from relevant departments of the enterprise should also partner to provide expertise in hazard analysis (Figure 2). For example, Facilities and Building Systems Operations may assist in identifying the relative risk for Technological Hazards such as an electrical failure. If a particular location is not owned by a health system, emergency managers should engage with property management companies to conduct HVAs. This allows for a systematic, realistic assessment of hazards likely to impact operations at outpatient locations. Additionally, by taking an inclusive approach to HVA, administrative and clinical leaders in outpatient environments are given an opportunity to interface with enterprise resources and SMEs to ask questions and discuss redundancies and contingencies. It is not a regulatory requirement for primary and specialty locations to complete an HVA; however, based on geographic location, findings from the ASC HVAs may be extrapolated for primary and specialty care locations to help drive planning and preparedness activities. The third step in creating a comprehensive program is to conduct emergency operations planning for outpatient facilities. Planning is intended to address strategic functions for enterprise wide emergency preparedness, license-specific operational capabilities, and hazard-specific response tactics (Figure 3). Emergency Management Plans (EMP) are license-specific and used for local response when certain functions/locations of outpatient facilities are affected by disasters. When the needs of outpatient locations outweigh available resources within that domain, an Enterprise Emergency Operations Plan (EOP) should be used to increase capacity and capability to manage the incident. Each ASC must have an EOP to delineate all-hazards guidelines and procedures with location and hazard-specific considerations addressed. 9

FIGURE 2 Hazard Vulnerability Analysis Stakeholders.

FIGURE 3 Health System Plan Structure.

A single EMP may be created for primary and specialty care locations with geographic and service-providing similarities in order to effectively address the 4 phases of emergency management and 6 mission critical areas of the Joint Commission. 8 Hazard-specific planning should focus on a tactical response for hazards most likely to impact outpatient facilities. This type of planning should use findings from HVAs and real-life incidents to delineate steps for response.

An important fourth element in developing a comprehensive emergency management program is to take a multimodal approach to outreach, education, training, and exercising. Because everyone has a role during an emergency, it is imperative to involve all health care personnel in training and exercises. 4 ASCs must participate in 1 exercise annually to meet regulatory requirements. 9 Emergency managers should consider designing exercises to include stakeholders from across the health system to discuss resource sharing such as critical equipment, supplies, pharmaceuticals, and personnel, as well as testing communication flows throughout the enterprise.

In-person training is invaluable because it allows for relationship building, assessing the physical layout and structure of outpatient facilities, sharing resources available to assist in response, and better positioning of health care personnel to transition into an emergency response when necessary. However, because of geographic disparity, virtual training options may also be necessary in order to reach all outpatient employees. Emergency managers may consider developing online modules in the form of games to make training interactive and engaging for staff. Additionally, taking advantage of National Preparedness Month, recognized each September, provides an opportunity to share updates on health system emergency management; the importance of year-long planning; local, state, and national emergency management resources; and conduct training for staff.

A strong, successful health care emergency management program follows the basic tenants of the discipline that are well familiar to professionals in the field. The building blocks for organizational resiliency are encapsulated in emergency management tenants, including relationship building, risk-driven planning, and consistent, inclusive training and exercising.

CONCLUSION

When embraced and implemented effectively, enterprise health care emergency management can provide efficient and sustainable solutions that enhance the integration of many health-care-related emergency response initiatives. Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Brewster3 As innovation and technology evolve in health care, emergency managers should capitalize and use technologies to further engage outpatient locations in a systems approach for emergency management. Likewise, emergency management continues to be a vast and ever-growing field within health care. Regulatory requirements, as well as lessons learned from real-life events, have shown the value of emergency management for protecting people, property, environment, reputation, and revenue of a health system.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.