In the last decade, more than 2.6 billion people have been affected world-wide by natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, cyclones and floods. 1 An estimated 1.2 million people are killed and as many as 50 million are injured every year in serious man-made incidents, of which a large number are from mass casualty incidents. 2 In recent years there has also been a rise in global terrorism and civil unrest across the world. All these events have led to a significant number of casualties which can easily overwhelm existing healthcare systems. 3 Indonesia has had its fair share of man-made disasters, such as bomb blasts, air-crashes and civil disorder events. Since 1900, 429 natural disasters have been recorded, with floods and earthquakes being the most frequent. Reference Djalante, Garschagen, Thomalla, Shaw, Djalante, Garschagen, Thomalla and Shaw4

Most health sectors consider mass casualty management as an immediate priority in an emergency. 3 During times of disaster, hospitals play an integral role within the health-care system by providing essential emergency medical care to their communities. Without appropriate emergency planning, local health systems can easily become overwhelmed during a critical event. Limited resources, a surge in demand for medical services, disruption of communication and resource uncertainty pose significant challenges in providing care. 5 Trauma care is time sensitive and proper time management in initial patient care can result in better clinical outcomes. It is therefore important that hospitals organize their care processes to cope efficiently in disaster situations and ensure that the care provided is swift and the best possible under the circumstances. Reference Sauer, McCarthy, Knebel and Brewster6

Hospital staff will require guidance in their responses to civil emergencies. A hospital response plan for disasters and civil emergencies can enable hospital staff to be better prepared, and equipped with the knowledge and systems to ensure better management and flow of casualties. Reference Skryabina, Reedy, Amlot, Jaye and Riley7

Background

In 2003, a number of senior doctors in Indonesia teamed up to promote the conduct of the Hospital Preparedness for Emergencies (HOPE) course, promulgated by the Program for Enhancement of Emergency Response (PEER), and supported by the United States Agency for International Development / Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance. To date, the numbers of local instructors trained in the HOPE courses have been limited, and the overall number of HOPE-trained healthcare workers in the country is considered to be very small, although the real numbers are not available. There is no literature demonstrating that HOPE has been able to enhance the initial response of medical personnel or hospitals to disaster events, either in the country or elsewhere.

In 2014, the Singapore Health Services (SingHealth) was invited by the University of Hasanuddin (located in Makassar, Indonesia), to review hospital disaster preparedness in the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi, especially in the region of the province’s capital city of Makassar. The SingHealth team was also requested to design a hospital disaster management training system for the province, conduct training programs and build up a pool of Master Trainers to ensure continuance of the training system, at least in that part of the country.

Makassar has an area of 199.3 square kilometers and a local population of more than 1.6 million. Its built-up (or metro) area has 1976168 inhabitants, covering Makassar City and 15 districts. 8 Disaster preparedness plans vary widely across these districts. A needs assessment conducted by the SingHealth team in 2014 had noted a lack of standardization in hospital organizational systems in various hospitals in the area. Such dissimilarities in disaster management practices were noted across the spectrum of care provided at these hospitals, including emergency departments, operating theatres, intensive care units and inpatient wards. Hospital command and control systems varied widely in structure and functionality, from almost nil to a few nominal, incident-based, structures that had not been exercised in any organized fashion. In addition, there was neither a common curriculum for training of hospitals nor a standard training package to prepare hospitals for casualty management during disasters.

This paper focuses on the development and conduct of the hospital disaster support training program for South Sulawesi by SingHealth, in collaboration with Hasanuddin University, Makassar. The aim was to design a curriculum based on the hospital preparedness needs assessment, and implement a training program that has both theory and practical simulation exercises, to better enable participants to understand the concepts of disaster response in medicine. Instructors were also identified during the program, and trained to ensure the sustainability of this program in the future.

METHODS

Summary of Needs Assessment Study for Hospitals in Makassar

To better tailor the program for hospital staff in Indonesia, a needs assessment study was conducted by SingHealth in February 2014 in the greater Makassar area. Hospitals were visited and meetings were held with the stakeholders involved (Table 1). Stakeholders included the heads of department of the primary health clinics and hospitals, hospital administrators, and nursing heads in the various hospitals. Essential information was collected and used to create the curriculum, to address the needs of the local hospitals. Overall standards for the course were defined in the local context and candidate requirements for training were described. The key findings in the Hospital needs assessment study were as follows:

Table 1 Stakeholders Consulted During Needs Assessment Phase

Table 2 Curriculum With Suggested Modes of Delivery of Instruction

Lack of Acuity-Based Triage System

None of the hospitals in Makassar practiced acuity-based triage at their Emergency Departments. Casualties arriving in the Emergency Department were classified by the service that was thought to be appropriate for their care (medical or surgical), rather than their acuity. This meant that sicker patients requiring urgent care might be seen later than healthier patients who arrived earlier. This could potentially result in worse outcomes for sicker casualties.

Inappropriate Utilization of Resources

There was a tendency for hospitals to keep light casualties within the Emergency Department even if large numbers of patients presented there. There was also a marked reluctance to move such patients to nearby outpatient clinic areas in the hospitals. Moving such patients would have allowed the Emergency Departments to focus on the really ill casualties. Every patient was placed on a trolley, including the ambulant ones.

Hospitals not Taking Responsibility for Disaster Management

Many hospitals did not appreciate that in a disaster situation, the whole hospital had to get involved in managing casualties brought there from the disaster site, instead of simply leaving it to the emergency department doctors to manage the situation.

No Planned Manpower or Logistics for Surge Capacity

There were no clear plans for increasing manpower at Emergency departments or other key areas of hospitals to cope with increased workload due to more severe disasters. The expectation was that each department in the hospital had to continue managing their own casualties without cutting back on their elective workload. Neither were there spare supplies for acute surges in casualty scenarios.

Training for Front-Line Staff

There was a serious lack of trained persons staffing the front-line Emergency Departments in Makassar. Training programs in Basic Trauma and Cardiac Life Support that were being conducted by the Public Safety Centre fell short of addressing the numbers that needed to be trained. Inpatient care staff were also hardly trained in basic life support core skills.

Lack of Disaster Planning in Hospitals

The team also noted the lack of structured Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for hospital operations in disaster situations. In addition, most hospitals did not have a plan for internal hospital disaster management.

Curriculum

Based on the lapses noted during the needs assessment phase, a curriculum was developed for Hospital Management of Disasters (Table 2). The requirements covered all areas of hospital operations. The curriculum was developed to address the noted requirements based on international best practices, concepts in disaster management, and in the context of Indonesian healthcare system and disaster management regulations. 9 This became the template for the development of the Medical Disaster Support courses. The curriculum (Table 3) would allow personnel with various backgrounds, including emergency department and inpatient doctors and nurses, surgeons, operating theatre and intensive care unit staff, and hospital administrators] to develop the requisite knowledge, skills and attitude for disaster management.

Table 3 Hospital Disaster Medical Support Course Programme

Legend:

![]() Small Group Workshops / Practical Exercises

Small Group Workshops / Practical Exercises

The rationale for the various components of the curriculum was as follows:

1) Overview of Disaster Management: This was to ensure that all participants had a uniform understanding of the threats facing Indonesia, the definitions used in disaster management, the effects of disasters on people and hospitals, how hospitals relate to other agencies in the different phases of disaster operations, and the various roles hospitals can play in disasters.

2) Activation and Mobilization of Hospitals: The need for manpower and logistics planning for disasters, the ability to identify the manpower and materiel requirements of various key areas of the hospitals, and the timely sourcing of these were also required in the curriculum. This was to ensure that hospitals plan for and allocate appropriate manpower and resources to for casualty management instead of leaving emergency department staff to manage the situation.

3) Triage Systems: There was a need to identify critically ill patients and ensure that they received immediate resuscitation. Without a triage system, sicker patients might not get the crucial treatment they required in the ensuing chaos, leading to a high morbidity and mortality rate. Implementing a triage system for classifying patients according to their acuity was felt to be necessary. The red, yellow, green, and black priority system was implemented. Reference Lee10 The principle of disaster management is to “do the most good for the most people.” In a disaster during which resources may be limited, in order to maximize care for the majority of patients, some patients with little or no chance of survival may not be resuscitated. There was also a need to include in the curriculum the need for adjustments to be made to allow light casualties to be managed either in an ambulatory setting, sent directly from the disaster-site to identified primary care polyclinics during such incidents, or allocated to different areas of a hospital based on different acuity.

4) Roles of Clinical Departments in Hospitals during Disasters: Hospitals needed to appreciate that disaster management was not just an Emergency Department affair, but involved the efforts of the whole hospital right from the moment word is received that the hospital may receive casualties. Therefore, operating theatres, intensive care units, inpatients wards (whether to be used as disaster wards or as areas to house patients transferred from designated disaster wards) needed clearly set-out standard operating procedures that hospital staff needed to be aware of and understand. These procedures would also need to be reviewed in the case of disasters occurring within the hospital.

5) Administrative Support Systems in Disasters: Hospitals need to know how to move the institution from the pre-disaster situation, reorganize resources, and support the additional and special casualties that may occur during disasters. This would require command and control systems, good communication, and active participation of support mechanisms for management of the dead, media care, and other clinical support functions.

6) Special Disaster Situations: A review of previous disasters that have occurred in Indonesia revealed that certain disaster situations required special solutions. This included floods, bomb blast incidents, chemical incidents and infectious disease outbreaks, all of which required special arrangements for hospitals to ably manage such incidents.

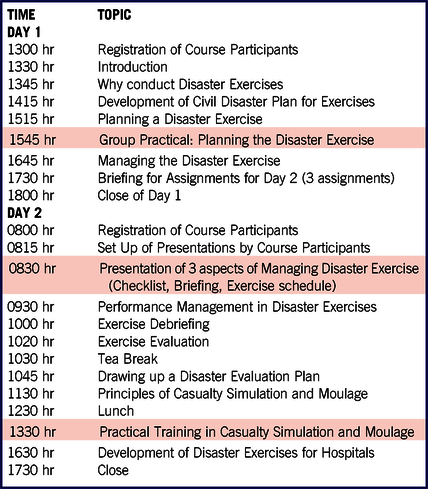

7) Disaster Planning and Exercises for Hospitals: There is a need to address this in the curriculum, not just in general but for each hospital and constituent department, so that every area of the hospital would have a clear set of procedures that could be practiced and improvised upon. Front-line staff of hospitals needed to be better trained to ensure an acceptable standard of initial assessment of trauma and basic resuscitation skills. This could be achieved by increasing the frequency of courses and exercises conducted, increasing the pool of trainers and establishing more training centers across the province to reach out to a wider audience. The SingHealth team recommended that all staff working in emergency departments or those who might be sent as disaster medical response teams be trained in the technical and managerial skills of disaster management. Such courses were seldom conducted in Makassar. With the large numbers of healthcare workers in the many hospitals in the city and the larger numbers of members of the community, there was a need to set up training centers for the teaching of the vital skills needed to function effectively in disasters. A supplementary course in Disaster Exercise Planning and Implementation (Table 4) was added for the master trainers to enable them to plan for disaster exercises and simulation drills.

Table 4 Disaster Exercise Planning and Implementation Course Programme

Training Program

Teaching disaster medicine can be difficult, so we attempted to make it as practical as possible. learning benefits most from simulating multi-faceted environments, we incorporated not only didactic lectures, small group discussions, practical sessions, and exercises for hands-on training. Reference Ernst and Bernd11 The curriculum was translated into three-and-a half days of training that included the following:

-

A two-day program focusing on the core knowledge and skills required for hospital management in disaster scenarios, cutting across emergency departments, operating theatres, intensive care units, hospital wards, senior management, etcetera. (Table 3)

-

A one-and-half day Disaster Exercise Planning and Implementation Course (DEPIC – Table 4) that focused on a variety of disaster exercises, their planning, conduct, and debrief, and also simulations in the form of casualty moulage to increase the realism that can brought about in disaster training. This was only for those identified as potential trainers.

Exercises

Simulation exercises had been found to improve the understanding and level of confidence in learning the principals of disaster response medicine. Reference Ismail, Mohd, Husyairi and Shamsuriani12,Reference Behar, Uperman and Ramirez13 Exercises were held to put into practice what had been taught. This brought a more realistic and hands-on element to the trainers and participants. Three disaster exercises involving hospitals were conducted:

-

The first focused on the organization and management of hospital emergency departments, hospital command posts, casualty flow, and management in the emergency department, and involved two emergency departments.

-

The second involved the organization and management of intensive care units, operating theatres, disaster wards, and hospital command posts of three hospitals and two primary care polyclinics, with emphasis on casualty flow and management.

-

The third was the largest disaster exercise ever to have been conducted in Makassar. It involved five hospitals (three in the public sector, one in the private sector and one military hospital) together with three primary care polyclinics. The simulated exercise scenario involved multiple explosions occurring simultaneously across the city. The hospitals were to be prepared to send teams to the disaster sites, receive casualties, treat the casualties on initial arrival in the emergency department with proper triage, and manage their disaster wards, operating theatres and intensive care units for the disaster.Various disaster response agencies were involved in organizing the disaster site and managing casualty evacuation to the various hospitals and primary care centers. This is important in a disaster because the public health system needs to know how to interact and coordinate casualty care with all hospitals in the community. The exercise was an excellent illustration of the need for inter-agency cooperation for disaster management. It demonstrated the need for coordination not only between departments within the hospitals, but also within the community.

These exercises were important as they helped bring to life what had been taught in theory during the training visits. They demonstrated to the participants what can be achieved through practice and participation. Communication between departments within a hospital, between hospitals, and with the various disaster agencies were all highlighted and taught during the exercises. During the workshop sessions, many participants had initially felt it would be difficult to coordinate between different departments and hospitals. The exercises showed the importance of bringing various departments, hospitals and agencies together in the community and how it was possible to do so. All the institutions participated actively in the debrief sessions conducted after the exercises.

RESULTS

Number of Participants

This program was carried out over a two-year period with six visits to Makassar by the SingHealth Team. Each visit was to different healthcare staff of various departments in various hospitals. Two days were focused on teaching the core knowledge and skills required for general hospital management in disasters, with an additional one-and-half day program to teach planning and conducting disaster response implementation and simulation. The last visit involved a large disaster exercise in Makassar involving five hospitals and other primary health care clinics. The training program was successfully concluded in February 2016. As a result of the popularity with the various local agencies, there was a higher than expected number of participants in the final exercise, including 310 participants trained in the Medical Support Program and Disaster Exercise Planning and Implementation courses; 340 participants in the focused disaster exercises; and an estimated 650 participants in the community-wide summary exercise.

To ensure sustainability of the program, potential candidates were identified as master trainers based on recommendations by local agencies, as well as their attendance and performance at the training sessions. By equipping them with knowledge and skills to become instructors of this program, we planned for the program to be handed over and sustained by a local team. A total of 73 master trainers were identified above the initial target of 50. They were in turn supported by local agencies to conduct further training programs in Makassar.

Challenges Faced During the Program

There were a number of challenges and opportunities to address them during the program. These included:

Language Challenges

The main language spoken in Makassar is Bahasa Indonesia. Interpreters were required during the initial teaching sessions. Training materials needed to be translated into the local language for better understanding of the participants. This required time, commitment of linguistic expertise, and active support from the local institutions and master trainers.

Liaison Difficulties with Different Hospitals and Agencies

The exercises required the participation of other hospitals, polyclinics and external agencies such as the police, rescue services, the office of the mayor, the local district health office, and many others. This meant meeting with the various hospitals and agency representatives and initially getting their consent to be part of the exercises. At the beginning of the program, multiple half-day familiarization and awareness sessions with the local community were conducted to increase awareness of the importance of joint efforts for the most effective local management of disasters. One-to-one meetings were needed with the main hospitals and polyclinics. Regular engagement of the various local disaster agencies and hospitals was needed to ensure that all stakeholders continued to feel the need for the various important roles in a disaster.

Promoting Communication Between Hospitals

The exercises helped give the participants a greater understanding of how important it was for different hospitals and agencies to come together during a disaster to manage the casualties. The exercises conducted were the first opportunity for all hospitals and other agencies to meet in the same rooms and plan and work together. Communication between hospitals is important for distribution of casualties during a disaster. Hospitals and external agencies need to coordinate and communicate with one another in preparation for and during a civil disaster. The local community understood the need for a health services coordinator. Regular engagement of the local disaster response agencies with University Hasanuddin will be needed to ensure that all agencies continue to embrace their important roles in disaster management and work together in a collaborative manner.

Long Term Sustainability

As with any other program, there has to be active application of the knowledge and concepts learnt. The small workshop-type discussions and practical exercises allowed course participants to appreciate and relate the relevance of each aspect of hospital management to their own healthcare institution. In addition, the University set up a Disaster Management Training secretariat office within its campus to serve as a coordinating center for all such courses.

DISCUSSION

These were not the first hospital disaster management courses held in Indonesia. There had been previous courses such as the HOPE (Hospital Preparedness for Emergencies) Reference Dey, Vu, Herbosa and Collier14 program which had been available in Indonesia for more than ten years. Although a few hundred had been trained in the program, there has been an apparent inability to translate the concepts taught into definitive practice. The aim of the HDMS program that we designed and introduced into Indonesia was not just to teach concepts, but translate these concepts into actions at the level of the individual clinical and non-clinical departments in hospitals and other health clinics. The HDMS program included manpower planning, determining manpower norms for the various departments, logistic requirements, detailed procedures, and how to obtain resources and implement processes in the response to a civil emergency. The program also did not aim to teach basic life support or advanced trauma support in a disaster. Such skills were already well taught in established training programs. Rather, we wanted to teach the pertinent organizational and management concepts for a disaster situation and translate these into standard operating procedures and processes in the hospital system. The simulations and practical exercises helped greater understanding of procedures that required implementation in the hospitals. Tabletop exercises and simulations have been said to be superior to other traditional teaching methods, such as didactic lectures, for disaster management Reference Ismail, Mohd, Husyairi and Shamsuriani12,Reference Behar, Uperman and Ramirez13,Reference Khorram-Manesh16

Hospitals that intend to improve their levels of preparedness for emergencies need to focus on two major areas. These are training and preparedness of hospital staff and availability of management tools, procedures, and resources to utilize when responding to the disaster. Both of these can be achieved during the preparedness phase of the disaster management cycle.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has produced an excellent monograph 15 the “Health Sector Emergency Preparedness Guide,” to explain these concepts to the healthcare community. This guide covers general concepts in disaster preparation that healthcare planners will need to understand and that should form the basis for the evolution of the detailed procedures for implementation in each community. WHO has also produced a document for Europe 5 that lists out the targets to be achieved at each area of the hospital and phase of disaster management. Such lists may also be used with suitable modification for other regions of the world. The HOPE program Reference Dey, Vu, Herbosa and Collier14 similarly explains strategies and over-arching guidelines that would be useful for hospitals preparing for disasters. The challenge for healthcare facilities has, in most instances, been one of translating these strategies and guidelines into action, and testing their hospital disaster plans to better ensure preparedness.

The HDMS program has tried to bridge that translation gap by focusing on interactive training and exercises to address human preparedness through clear operating procedures. Majority of the participants felt the field exercises were engaging and enabled them to understand the concepts of disaster response better. This was similar to other teaching centres where simulated drills were the most effective method to teach disaster medicine. Reference Khorram-Manesh16,Reference Hsu, Jenckes and Catlett17 The program also aims for all institutions to have clear disaster plans and inventories of their manpower and logistics needs; identify resource needs for disasters, including how they would acquire, store and maintain those resources; have all arrangements made in the preparation phase; and then activating and deploying these when emergencies strike.

CONCLUSION

This project was a collaborative effort between SingHealth, Hasanuddin University, and major stakeholders of disaster management in Indonesia. It was a good learning experience for both the Singapore Team and the local participants, as we learnt from one another.

The program helped equip local hospitals and staff with the knowledge and skills for hospital disaster preparedness, and enabled them to draw up detailed procedures for functioning during disasters. With constant support from the major stakeholders, continuous training and exercises by the local community, the sustainability of this program in Makassar will be better assured.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to University of Hasanuddin, Makassar for inviting the SingHealth team to design and conduct the program. We would like to thank all the stakeholders in Makassar: Hasanuddin University, District Health Office of Makassar, the Office of the Mayor, hospitals, community clinics, Badan Penanggulangan Bencana Daerah (BPBD), Badan Search and Rescue Nasional Makassar (BaSARNas), the military, and the Police force. We are thankful to Temasek Foundation for the support and funding of this course. The enthusiasm of the local trainers made the process easier.

Our deep appreciation also goes to the other members of the SingHealth Team who were involved in the program: Assistant Prof. Mark Leong, Dr. Gene Ong, Dr. Wong Ting Hway, Dr. Chng Siew Ping, Dr. Jade Kua, Dr. Juliana Poh, Dr. Lim Jiahao, Dr. Geraldine Leong, Dr. Vincent Lum, Dr. Ivan Chua, Dr. Chan Jing Jing, Mrs. Angela Lee, and Mr. Wayan Tjoa Irwanto.