Disaster exercises and other forms of training should be followed by thorough evaluation. Various methods are used to evaluate exercises and the disaster preparedness of a medical institution.Reference Williams, Nocera and Casteel 1 Traditionally, the evaluation is based on input from 3 dimensions: surveys, direct live observation, and video analysis.Reference Kaji, Langford and Lewis 2 Data from registration systems and observational cameras can also be reviewed to judge the performance of a hospital during the response to a major incident. However, these observation techniques only show a part of the process the patients are put through. The events are reviewed by a single observer or are subject to personal interpretation of the evaluator or observer. To provide accurate insight into patient experience during hospital disaster response, we equipped mock victims with point-of-view video cameras. This additional fourth dimension provides the evaluator with footage that can illustrate the course of the patient during trauma care. Furthermore, the performance of the medical care provided to the patient can be analyzed on the basis of treatments and time. The Major Incident Hospital (MIH) in Utrecht, the Netherlands, organizes large full-scale trauma drills with mock victims on a yearly basis. These drills function as a tool to optimize the response to future major incidents. The MIH serves as a standby, highly prepared hospital that can deploy 200 additional beds within 30 minutes to the Dutch medical system in case of major incidents.Reference Marres, Bemelman and van der Eijk 3 , Reference Marres, van der Eijk and Bemelman 4 In short, it is a backup hospital for the Dutch health care system that is equipped with the full range of medical options for patients from major incidents. The hospital is deployed only when the surge from an incident exceeds the capability of the regular health care system. The hospital includes accident and emergency, intensive care unit, medium care, and low care beds, as well as 3 operating rooms and equipment to care for pediatric patients. Staffing takes place from the University Medical Center Utrecht and the military hospital adjacent to the MIH. The aim of this concept study was to test the feasibility of evaluating video from the patient’s perspective and to develop a prospective standardized method for evaluating hospitals’ major incident response exercises with the use of such video footage.

METHODS

During the full-scale trauma drill in 2014, two mock patients were each equipped with a point-of-view camera to gain a first experience with the new system (Figure 1). The drill involved 100 mock victims with traumatic injuries and additional need for decontamination resulting from the crash of a train transporting hazardous substances. The drill was mainly conducted in the MIH of the University Medical Center Utrecht. The regular emergency department of the University Medical Center Utrecht continued patient care. The emergency medical services and Dutch armed forces participated in patient transport and care. Mock victims were professional actors specifically trained to play patients with medical and surgical conditions. The observers consisted of medical specialists, trained observers from the armed forces, and experts in the field of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) incidents.

Figure 1 A Mock Patient Wearing the Action Camera During a Trauma Drill.

The footage from the point-of-view camera gave insight into the patient’s experience of the decontamination process and the primary survey in the shock room of the MIH (Figure 2). The footage was analyzed by the principal investigator, and the information extracted from the images was used to create a protocol to measure the performance of medical care during a hospital’s major incident response. The protocol was designed to follow the course of the patient from the initial arrival in the ambulance bay to admittance on a ward. The protocol focused on registration and time and resource management.

Figure 2 The Patient’s Perspective in the Trauma Bay During the Primary Survey.

During the second full-scale trauma drill in 2015, two mock victims were again equipped with point-of-view cameras. The drill was set up as a major traffic crash that resulted in 120 victims, some of whom needed decontamination as the result of hazardous substance contamination from a transport wagon. The drill was designed to be similar to the 2014 drill but with a different scenario. The involved agencies, mock victims, and observers were similar to 2014. The drill served as a basis to test the protocol prospectively and determine the feasibility of evaluation of video from the patient perspective.

RESULTS

Feasibility

During the first drill, 2 mock patients were successfully equipped with point-of-view cameras. The audiovisual results were of adequate quality for evaluation.

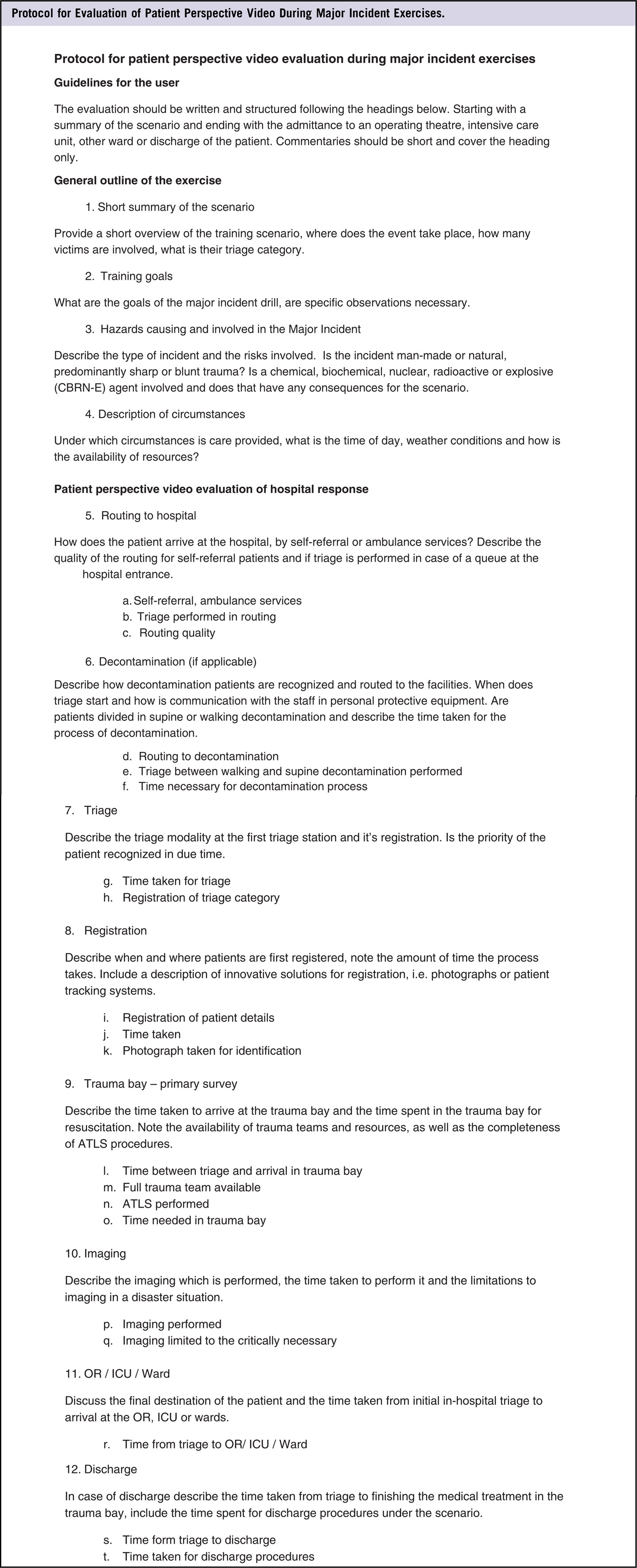

Video 1 and video 2 in the online data supplement show short clips of decontamination and a trauma bay scenario to illustrate the footage obtained during the drills. The obtained videos were a good addition to the observers’ feedback and offered new insights that were not gained by use of the traditional methods. For the first time, it was possible to see the care process through the eyes of the patient. These insights were useful for communication training of the medical staff. Furthermore, from this footage from the patient’s perspective it was possible to evaluate the care given and the time and resources consumed for the individual patient during damage control care. The information was used to set up the evaluation protocol, which is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Protocol for Evaluation of Patient Perspective Video During Major Incident Exercises.

In a second trauma drill, the evaluation protocol was first tested live. The resulting footage was reviewed and was successfully implemented into the evaluation protocol. Registration of all subfields was possible, and time effectiveness could be evaluated as well as completeness of the trauma care and decontamination process.

Outcome

The implementation of the point-of-view cameras and the protocol in the 2015 major trauma drill was successful. Review of the footage provided new insights in addition to the traditional methods. During the drill in 2015, one observer was constantly present in the decontamination facilities; the feedback had focused on the medical process and the communication within the medical team. The footage from the patient’s perspective taught us that the nonmedical aspects of decontamination needed improvement. Particularly, the routing to the decontamination unit was confusing, and communication with the mock victim upon arrival at the decontamination unit was insufficient. The traditional observer did not note these observations. Furthermore, the footage gave insight into adherence to the lead times set for the primary survey within the trauma bay. In general, footage from the patient’s perspective could serve 2 purposes in training of medical staff. First, it can improve patient communication through review by the involved personnel. Second, it can illustrate how a treatment is experienced by a patient.

DISCUSSION

This concept study introduces a fourth evaluation dimension for medical training and hospital operations in addition to the traditional methods. By use of action cameras, footage was taken from the patient’s perspective to capture the patient’s experience in order to judge the performance of a medical system during trauma drills. On the basis of the experiences from one major trauma drill, a protocol was designed and tested in a second trauma drill. The evaluation method provided additional insights to the traditional methods.

The protocol proposed is designed to be generic and widely usable without adaptation. The protocol is to be used with free text or can be adapted to be quantifiable, based on a hospital’s specific major incident response design (ie, lead times for patient transport or primary survey). It is a new type of evaluation tool that can be extended to many types of training, including communications training for medical students.

Most literature on disaster education and training is based on reporting of lessons learned and other mostly subjective measures.Reference Williams, Nocera and Casteel 1 , Reference Auf der Heide 5 Various efforts have been made to create and promote standardized and objective tools; however, implementation has been minimal.Reference Williams, Nocera and Casteel 1 , Reference Markenson, DiMaggio and Redlener 6 - Reference Klein, Brandenburg and Atas 8 Video evaluation has the benefit of reproducibility. The exact same footage can be studied several times by any number of people, making it a method open to objectification.Reference Tiel Groenestege-Kreb, van Maarseveen and Leenen 9 The added value of video registration in trauma care has been described in the literature and can serve 3 main goals: first, for educational purposes by reviewing tapes of trauma care; second, to assess quality, such as guideline adherence; and last, for research purposes.Reference Tiel Groenestege-Kreb, van Maarseveen and Leenen 9 , Reference Santora, Trooskin and Blank 10 To remove the subjective assessment, guidelines should be written and followed by reviewers in the analysis process.Reference Blank-Reid and Kaplan 11 Video analysis has been shown to be useful in assessment of teamwork and leadership as well.Reference Santora, Trooskin and Blank 10 Assessment of communication with patients can be further improved by the patient perspective. Video review has further proven to assist with rapid and sustained learning and was shown to be more effective in behavioral improvement than purely verbal feedback.Reference Scherer, Chang and Meredith 12

This study was a limited first experience with a new approach to drill evaluation. Although multiple observers have used the images for evaluation purposes, the principal investigator was the only one to analyze the footage entirely to set up the evaluation protocol. Further work should be done to validate the protocol and the use of evaluation from the patient’s perspective.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a fourth dimension can be added to the evaluation process by using point-of-view cameras to capture the patient’s perspective during trauma care exercises and major incident drills. On the basis of our initial experiences, a protocol was developed to evaluate the medical system during a major incident trauma drill and tested in a consecutive drill. New insights have been gained from this perspective that were not obtained through traditional surveys, observers, and traditional video footage. Video evaluation can be a valuable addition to medical training and other goals involving the patient’s experience of the medical system.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https:/doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2016.179.