Suicide is a serious public health concern, with numerous previous studies exploring the relationship between disasters and suicide. Although some of these studies found increases in suicide as a direct consequence of disaster,Reference Chou, Huang and Lee 1 - Reference Larrance, Anastario and Lawry 5 other research did not detect an increase in disaster-related suicide after such events.Reference Krug, Kresnow and Peddicord 6 - Reference Nishio, Akazawa and Shibuya 11 A recent review of the literature revealed that lack of baseline data, varied cultural perspectives, and different research methodologies hamper efforts to settle the question of whether deaths by suicide actually increase as a consequence of disaster-induced psychopathology or disaster exacerbation of existing psychopathology.Reference Krug, Kresnow and Peddicord 6 , Reference Kloves, Kloves and DeLeo 10 , Reference Bonanno, Brewin and Kaniasty 12 What is generally accepted is that depression, anxiety, and feelings of hopelessness are common precursors of suicide ideation.Reference Nock, Hwang and Sampson 13 - Reference Beck 17 What remains unclear is who will progress from suicide ideation to suicide plans and attempts.Reference Nock, Hwang and Sampson 13

Research examining the effects of disaster on mental health has consistently demonstrated that affected individuals are at increased risk for developing depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorders, among other mental health problems.Reference Caldera, Palma and Penayo 18 - Reference Norris, Perilla and Riad 22 A meta-analysis of the psychological effects of natural disasters found that the prevalence rate of psychopathology increased approximately 17% following natural disasters.Reference Rubonis and Bickman 23 Such increases in psychopathology may result from other severe, adverse postdisaster outcomes including the loss of loved ones, injuries, loss of property, disruption of social support, and predisaster behavioral health disorders.Reference Chou, Huang and Lee 1 , Reference Yang, Xirasagar and Chung 3 , Reference Bonanno, Brewin and Kaniasty 12 , Reference Caldera, Palma and Penayo 18 , Reference Tang, Yen and Cheng 24 - Reference Jones, Allen and Norris 32 Approximately 95% of those who die by suicide have a mental disorder at the time of their death.Reference Cavanagh, Carson and Sharpe 33 , Reference Harris and Barraclough 34

Given that psychosocial disruption is common after disasters, it is advantageous and reasonable to expect that crisis counselors are able to identify and address suicidal ideation and behaviors. However, the extent and depth of training to detect signs of suicide may vary widely by educational program and disciplinary background. Moreover, the absence of professional behavioral health resources after disasters frequently prompts state and local agencies to employ counselors from the community who may have little formal training or experience in providing crisis counseling.Reference Acierno, Ruggiero and Galea 35 , Reference Norris, Hamblen and Brown 36 Although suicide is acknowledged as a major concern and the need to be professionally prepared to effectively deal with such situations is recognized, if counselors are in fact able to identify and respond to suicidal ideation in clients is less clear.

As previous work has not explored the ability of counselors to detect the presence of suicidal ideation or behaviors, the present study had 2 major objectives. The first was to assess the awareness of risk and protective factors for suicidal behaviors on the part of counselors with different disciplinary backgrounds. The second aim was to evaluate the ability of these same professionals in detecting potentially suicidal clients, as well as their self-perception of the adequacy of their preparation to manage suicide threat.

Background

In 2004, the state of Florida was overwhelmed by an intense and prolonged hurricane season. Beyond the destruction inflicted on homes and communities were the intangible consequences such as depression, PTSD, stress, and suicidal ideation. Approximately 11% of Florida residents met criteria for at least 1 of 3 disorders (PTSD-general, generalized anxiety disorder, or major depressive episode) following the hurricanes.Reference Warheit, Zimmerman and Khoury 37

As a result, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration provided funding for Project Recovery, a program that was administered by the Florida Department of Children and Families (DCF) to provide disaster behavioral health services to those who had been adversely affected by the storms. Project Recovery was designed to enhance and extend the state’s capacity to help individuals with severe emotional distress. The Project Recovery model was grounded in the notion that most survivors require assistance in mobilizing positive coping skills and maintaining a realistic understanding of what is considered “normal” under abnormal circumstances.Reference Castellanos, Perez and Lewis 8

In 7 DCF districts (27 counties) that were most affected by the storms, multidisciplinary teams comprised of certified addiction professionals, vocational counselors, clinical social workers, psychologists, and family services and school case managers offered services and treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy, vocational case management, family case management, alcohol or substance abuse treatment, play therapy for children, and education for developing general coping skills. Affected populations targeted for outreach included people who were displaced from their homes, adults and children exhibiting continued disaster-related stress, older persons, migrant families, persons with disabilities, teachers and caregivers working with children in highly impacted areas, and individuals from Cuban, Haitian, Filipino, and Southeast Asian cultures. Services were offered at local mental health agencies, schools, churches, migrant camps, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)-sponsored and private trailer parks, senior service centers, clients’ homes, and mobile units in rural areas. Purchase of service funding was used for clients who had treatment-related needs and had to be referred to outside agencies for specialized services such as transportation assistance and alcohol or drug detoxification. As Project Recovery’s services were not intended to be a substitute for people in need of long-term mental health or substance abuse treatment, the program did not pay for long-term services.

Project Recovery crisis counselors received disaster-specific crisis counseling training from the National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Crisis counselors who received specialized training were taught cognitive behavioral therapy for use with adults and brief postdisaster interventions for use with children and adolescents. To complement the child specific training given by the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress, crisis counselors with previous professional experience using art assessment and play therapy also used these techniques with children. As needed, clients received a variety of services from different members of the Project Recovery team.

Although behavioral health services were offered to clients, minimal research has explored how hurricane survivors with suicidal ideation utilize such services. Further, little is known about the concerns of counselors who treated clients with suicidal ideation. Because Florida experiences a recurrent but unpredictable yearly hurricane season, it is imperative to investigate if disaster behavioral health services meet the needs of those with suicidal ideation following hurricanes.

Methods

Sample

The study protocol was approved by the University of South Florida's Institutional Review Board. A mixed-methods approach was used to explore suicidal ideation in hurricane survivors, as well as counselor treatment considerations and perspectives of such clients using Project Recovery services. Deidentified client data (n=207) were used to identify counselors who had treated clients who had positively endorsed an item on the Short Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview–Extended (SPRINT-E), a disaster mental health measure, “Is there any possibility that you might hurt or kill yourself?” The clients’ results were examined and compared to those of clients who did not endorse this item (n=200).Reference Vehid, Alyanak and Eksi 38 Semistructured telephone interviews were conducted with the counselors (n=7).

Data Collection

Data from Project Recovery were analyzed to evaluate disaster-related stress symptoms (ie, depression, anxiety) as well as the number and types of services provided. Quantitative data on psychological distress and use of client behavioral health services were collected by Project Recovery behavioral health counselors.

To understand counselors’ practices and perspectives of client risk for suicide, a semistructured telephone interview was developed. Seven counselors who had administered the SPRINT-E to clients who had endorsed the suicide item were sent letters that provided informed consent information, described the study, and invited them to participate in a telephone interview. Five days after the letters were sent the counselors were contacted and interviews were scheduled and conducted by telephone.

Measures

The SPRINT-E was used with Project Recovery clients to assess distress and dysfunction to the recent hurricanes.Reference Vehid, Alyanak and Eksi 38 The 12-item measure includes items such as unwanted memories, depression, and suicidal ideation. Answers were given on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, not at all, to 5, very much. Three or more reactions listed as a 4 or 5 indicated a referral for more in-depth evaluation and behavioral health services should be offered. A client service use form was used to keep a record of demographic information and use of service type.

The counselor interview consisted of 22 open-ended questions that asked about suicidal ideation in clients as well as protocol issues. Previously collected quantitative data guided the development of the interview questions. Sample questions included, “Did your agency provide you with any specific guidelines or a protocol to follow with suicidal clients?” and “What types of suicidal thoughts or behaviors did your client have?”

Data Analyses

SPSS V.17 analysis software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to analyze assessment data. Missing values were evaluated and appropriate methods of imputation were determined. Data on clients experiencing suicidal ideation were examined and compared to data for clients who did not have suicidal ideation to examine the differences in SPRINT-E scores. Audiotaped interviews with counselors were transcribed and compared for accuracy. A coding guide was created and data were coded and analyzed using an inductive approach informed by grounded theory. Interview passages were sorted by category and reviewed for reoccurring themes, patterns, and structures.

Results

The 64 Project Recovery personnel represented all districts across the state. In total, 75% (n=48) were female and 25% (n=16) were male, with an average age of 48 years (range: 26-72 years). Almost three-quarters of the sample (73%) identified as white (n=47), followed by Hispanic (n=7) and black (including African American and Haitian; n=6); 4 others were missing responses or did not answer. The majority (73%) held master's degrees or higher. Slightly more than half (53%) did not speak a language other than English, but 21% were fluent in another language and another 21% considered themselves to have very basic to moderate second language skills. Of interest in Florida, 9 team members (14%) were bilingual English and Spanish speakers, but only 2 endorsed providing behavioral health services. Five of the 7 counselors who were interviewed were female, 6 were white, 1 was bilingual in Spanish, and all had master's degrees or higher. Professional degrees held by the crisis counselors included psychology (1), clinical social work (4), marriage and family therapist (1), and mental health counselor (1).

Although not all team members had prior experience working with survivors of natural disasters, the majority had experience with other types of trauma, ranging from sexual offenders to domestic violence to severely mentally ill patients. In addition, more than half reported at least “minimal” firsthand material damage or other trauma resulting from hurricanes, describing situations of evacuating their families and pets; having to make alternate living arrangements; having other family or friends move in with them after the storm; living without electricity; dealing with long lines and shortages of food, water, gas, and other supplies; and negotiating the bureaucracy of FEMA for assistance. Several of those who experienced more severe effects said that their own situations helped them empathize with their Project Recovery clients.

Quantitative Results

Most Project Recovery clients were women (78%). One-third of the clients (34%) were age 18-39, 52% were age 40-59, and 15% were 60 years of age or older. Slightly more than half were non-Hispanic white (58%), followed by non-Hispanic black (21%) and Hispanic (any race, 21%). More than half had attained a high school degree (64%), 19% were college graduates, and 17% had less than a high school education. Disaster-related stressors reported by clients included life threat (35%), witnessing injury (20%), participating in rescue or recovery efforts (19%), personal injury (18%), family member missing or dead (9%), or friend missing or dead (13%). Other stressors included damage to home (78%), financial loss (74%), and disaster-related unemployment (43%).

The characteristics of the 7 adults (3.4%) who endorsed the suicidal ideation item on the SPRINT-E were compared to those of the other clients who were not endorsing suicidal ideation on the measure (n=200). The characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1. An independent-samples t test determined that there were no significant differences in age between the 2 groups, t 193=−.512, p=ns.

Table 1 Group Characteristics

Although service use data were not available on 3 of the 7 clients with suicidal ideation, vocational case management was the primary service most often used by the other clients who reported suicidal ideation (57.1%). Three clients used alcohol or substance abuse counseling services (42.9%). One client used family case management (14.3%).

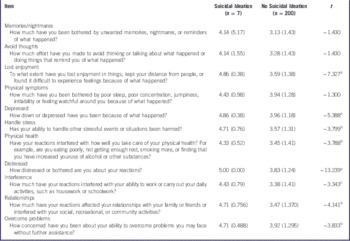

Table 2 provides group scores on the SPRINT-E. An independent-samples t test determined that there were significant differences on a majority of the items. Clients who reported suicidal ideation had significantly higher scores on items indicating a loss of enjoyment, feelings of depression, feeling less able to handle stress, feeling reactions were interfering with physical health, being distressed about reactions, feeling reactions were interfering with work as well as relationships, and an increased concern about being able to overcome problems.

Table 2 Comparison of SPRINT-E Scores Across Groups

SPRINT-E indicates Short Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview–Extended.

a P<.001.

b P<.01.

c P<.05.

Qualitative Results

The experiences and perceptions of 7 counselors with clients who endorsed the suicidal ideation item on the SPRINT-E were captured within 5 major themes: Assessment and Action, Client Characteristics, Services, Counselor Training and Preparedness, and Future Directions. Out of the 7 counselors, only 4 reported that they had clients who had suicidal ideation.

Assessment and Action

Assessment and Action referred to the process of identifying clients at risk for suicide by using the SPRINT-E measure. Those identified as having suicidal ideation were referred through various means for additional treatment. Within this category 2 themes emerged: Usefulness of the SPRINT-E and Referral Behavior.

Usefulness of the SPRINT-E

Most counselors felt that the SPRINT-E was helpful in guiding their clinical care. Counselors emphasized that it was useful as a tool to begin interactions with clients having thoughts of self-harm. However, not all of the counselors recognized that their client had suicidal ideation based on results of the SPRINT-E. Some indicated that they used their professional knowledge, not the SPRINT-E assessment tool, to recognize warning signs.

I had such a background working with individuals with mental illness that I just have a natural tendency to listen for those key points when people are down and out like that.

Referral Behavior

Once clients had been identified as having suicidal ideation, counselors often referred them for a more thorough assessment at a mental health center. If the client was an immediate threat to himself or herself, then a Baker Act, Florida's involuntary commitment law, was enacted and the individual was taken to a crisis stabilization unit.

She had some real serious suicidal ideation because of the hopelessness of the situation, we called law enforcement immediately because of her tendency to disappear pretty quickly. So they Baker Acted her and put her on the unit [crisis stabilization unit].

Client Characteristics

The characteristics of clients who were experiencing suicidal ideation appeared to follow several common themes. These included Thoughts and Behaviors, Mental Health Problems, and Expressed Reasons for Suicidal Behavior.

Thoughts and Behaviors

Counselors reported that most of their clients with suicidal ideation were also having thoughts of hopelessness, a common sign associated with suicidality. Many clients reported feeling helpless and unable to improve their situations.

They had thoughts such as “I can't go on,” a sense of hopelessness, lost everything, sense of loss, not being able to rebuild, having mental health problems, and feeling helpless about being able to recover physically along with recovering their lifestyle and regain living normally.

One counselor reported that her client often cried and was not sleeping well. He was reluctant to speak openly about his thoughts, but his behaviors were telling.

He wouldn’t talk about it openly, but I observed that he kept a lot in. He would cry. Our first several sessions he would cry a lot. He kind of admitted that at times he felt that way, but he really did not openly say, “I want to kill myself.”

Mental Health Problems

Most of the clients were experiencing feelings of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress, characteristic of psychological distress following natural disasters. Several had relationship difficulties occurring at the same time, negatively impacting current mental health problems. Although some clients developed new mental health problems, many had preexisting problems that were exacerbated by the hurricanes.

There was some PTSD, some posttraumatic stress, depression was pretty high on the list of course, mixed with some anxiety, generalized anxiety of loss and fear of not being able to ever have their lives back again, loss of support systems that generated the depression and anxiety. On the other hand, there were several clients that were already diagnosed… after the hurricanes they lost that support system one way or another and were left alone and become very unstable.

Some of the traumatic experiences endured by clients were a significant barrier to their healing process. Those who were directly affected by the devastation of the hurricanes seemed to have a more difficult time with PTSD.

We counted a lot of flashbacks and some very serious instances he had been involved in during the hurricanes. He had tried to save an elderly lady who had drowned in front of him. He had been up to his neck in water and he had a lot of traumatic experiences, and he was very estranged from his family.

Expressed Reasons for Suicidal Behavior

Many of the reasons for feeling suicidal among clients paralleled their current mental health problems. Damage to property, feeling helpless to change their situation, and experiencing losses in their lives seemed to play a role in creating suicidal thoughts among clients. For those dealing with relationship problems, fluctuations in interpersonal distress seemed to mediate severe psychological problems.

With the relationship problems, once he got better and he started to work and to improve, the relationship problem started to come up and he was getting depressed over that too.

Services

Counselors had varying perspectives in regards to whether services were sufficient for meeting the mental health needs of clients with suicidal ideation. The following themes were found: Adequacy of Services and Differences in Care.

Adequacy of Services

Whether services were viewed as sufficient in meeting the needs of clients with suicidal ideation differed among counselors. The reason for this difference may lie in the variations between agencies in terms of available services and resources.

It [Project Recovery] was definitely useful and they utilized it. It was good because we were able to provide both the case management and the therapy component and if the addiction piece was there we had the CAP [certified addiction professional] on staff. I think it was a good program and overall met their needs.

Conversely, other counselors thought the clinical care was inadequate for clients with suicidal ideation.

Well, I would say they were sufficient for being able to identify and begin to address the needs of the client. I don't think it was sufficient in the sense that of course we had to connect them to other services within the mental health system for any inpatient services and that was not included under Project Recovery.

Differences in Care

All counselors agreed that clinical care for clients with suicidal thoughts differed from that of other clients. At times it was appropriate to send clients to a crisis stabilization unit before engaging in standard cognitive behavioral treatment. If sending the client to an inpatient unit was not necessary, a contract for safety was completed. Most counselors reported that they checked in and maintained contact with their clients with suicidal thoughts more frequently.

She just needed more frequent contact and more support. She was less likely to follow through with things, so she needed a lot of prompting, encouragement, and reminders.

Counselor Training and Preparedness

An issue that arose during the interviews that engendered considerable discussion was the comprehensiveness of trainings given to counselors, including the lack of a Project Recovery protocol for clients with thoughts of self-harm. Two themes emerged within this category: Protocols and Adequate Training.

Protocols

Most counselors reported that Project Recovery had a protocol that was to be followed with clients experiencing suicidal ideation. Although 5 of the 7 counselors reported that a protocol was present, most of the protocols were part of the existing agency for which the counselors worked rather than a procedure created through Project Recovery.

Yes, we had a regular protocol that we followed because our agency is the community behavioral health center so this was something that is standardized within our systems.

Adequate Training

Whether counselors felt they were adequately prepared to handle suicidality in clients paralleled the situational factors that arose in relation to the existence of protocols. Although many of the counselors believed they had been adequately trained, it was often because of experience they had attained and trainings they had received from their mental health agency and not from Project Recovery training.

Through Project Recovery itself I don’t think that there was adequate training. Our agency, with all the training that we provide to our folks, that that was sufficient. One of the ways we were different from some of the other centers where they hired all new staff to do the project was we used almost entirely all existing staff from our agency.

Other counselors supported the notion that most of their training was from their own professional experience, rather than through Project Recovery itself.

I don’t recall ever having any training whatsoever or it ever even being brought up. We knew how to do contracts for safety from previous clinical training and previous jobs so we knew how to do that and we knew where other resources were. I think we felt we knew our roles were beyond Project Recovery, that our roles were counselors and therapists.

Future Directions

One of the most valuable categories for service improvement that emerged was the perspectives counselors had regarding what safeguards should be in place during future disasters for clients with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Having a protocol in place prior to disasters was deemed essential. It was also noted by several counselors that an important part of getting individuals treatment was increasing public awareness of the availability of disaster crisis counseling. Because disaster crisis counseling programs are discontinued when the demand for services significantly decreases or funding ends, it is difficult for providers to be ready with a team of well-trained counselors when a disaster strikes unexpectedly.

It’d be important to have a treatment team that is on call, or in reserve; have somebody who has a go-kit with all the forms for screening and all the practical items needed to do the crisis counseling, because that's when the suicide risk is highest when people are feeling the most desperate.

Discussion

Suicidal behavior is a serious mental health emergency, leading researchers and counselors to dedicate significant resources to understanding the etiology of such behaviors, developing and refining assessment methods, and determining interventions to effectively treat those at risk. Yet this remains challenging as suicidal behaviors are complex and disaster survivors with suicidal ideation may experience more intense psychological reactions to the event. Survivors with suicidal ideation expressed lost enjoyment, keeping their distance from people, or difficultly experiencing feelings because of what happened to a greater extent than those without suicidal ideation. Clients with suicidal ideation also had higher levels of depression and were more distressed about their reactions to the event. The postdisaster honeymoon phase, a relatively short period when media attention and external resources are dedicated to the afflicted area, is followed by a longer period when survivors experience additional daily hassles and ongoing challenges with reestablishing their lives. For those who were struggling predisaster with medical problems, financial issues, or employment concerns, the additional demands of dealing with insurance companies and government agencies, contending with a disrupted lifestyle, living in a damaged community, and coping with a diminished social network because of those who evacuated to other locations after the event, levels of depression, anxiety, and frustration may be exacerbated and increase during the recovery process.

Interviews with counselors added rich qualitative information about their clients. Counselors were able to provide a more descriptive portrayal of the characteristics of clients with suicidal ideation than what was available through quantitative data alone. Many of the clients had intense experiences as a result of the hurricanes and were coping with PTSD, depression, hopelessness, and anxiety, as well as tangible issues such as damage to their homes. There was a general consensus among counselors that although many of them felt adequately trained to handle clients with suicidal ideation, it was often because of their previous training in the mental health field. Counselors also provided insight into what future disaster mental health programs should require in order to protect the safety of clients experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Previous disaster studies have reported increases in suicidal ideation associated with postdisaster depression.Reference Joiner, Brown and Wingate 39 , Reference Chioqueta and Stiles 40 Research on the topic of suicide suggests that depression is a key risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicide.Reference Mattisson, Bogren and Horstmann 41 - Reference Neimeyer and Bonnelle 43 Further, some studies have found that individuals who were diagnosed with depression or another serious mental illness before a disaster occurrence were at greater need of more assistance postevent.Reference Chou, Huang and Lee 1 , Reference Rosen, Matthieu and Norris 27

Closely linked to depression is a sense of hopelessness, and a sense of ineffectiveness, which can reduce one’s ability to deal with change or stress.Reference Mattisson, Bogren and Horstmann 41 , Reference Carney and Hazler 42 According to Project Recovery crisis counselors, hurricane survivors with thoughts of suicide also experienced feelings of hopelessness. Many clients reported difficulties with obtaining shelter, repairs to their homes, employment, and transportation. This is consistent with previous studies of other disaster survivors finding a theme of hopelessness among those affected.Reference Chen, Yeh and Yang 25 , Reference Akbiyik, Coskun and Sumbulogulu 28

Counselors also frequently mentioned that clients with suicidal ideation often had symptoms of PTSD. Clients with suicidal thoughts scored significantly higher on SPRINT-E items indicating their reactions to the disasters were interfering with both their personal and professional lives as well as causing substantial distress. These results support previous research indicating that PTSD is a common outcome following natural disasters.Reference Caldera, Palma and Penayo 18 , Reference David, Mellman and Mendoza 19 Furthermore, in combination, PTSD and major depression could lead to more intense reactions and lower functioning among survivors and longer treatment recovery.Reference Larrance, Anastario and Lawry 5

Of concern is that some counselors may not receive sufficient training on working with suicidal individuals.Reference Elrod, Hamblen and Norris 44 , Reference Soliman, Lingle and Raymond 45 Training on important suicide risk factors is essential for decision-making and selecting interventions for these clients.Reference Elrod, Hamblen and Norris 44 This study demonstrates that even experienced counselors would benefit from additional training on assessing survivors who have depression, anxiety, and PTSD to identify those individuals who are particularly at risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors.

Counselors are expected to refer survivors who appear to be in need of immediate crisis intervention to designated mental health professionals for further assessment.Reference Rosen, Matthieu and Norris 27 , Reference Acierno, Ruggiero and Galea 35 Given the challenges encountered by trained counselors it is not surprising that the ability of paraprofessionals to accurately identify survivors in need of immediate intervention has been questioned.Reference Elrod, Hamblen and Norris 44 This study suggests that it is advantageous for all disaster responders to receive training in suicide detection and to have a protocol for referring those who are at risk.

The findings of this study emphasize the importance of understanding the needs of clients experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors who are using disaster behavioral health services. To effectively and expeditiously reduce immediate crises, counselors must be able to identify clients at risk.

In this study, several counselors did not realize that their clients had positively endorsed the self-harm item on the SPRINT-E; however, these counselors were still able to recognize that their client had thoughts of suicide. Items on assessment measures such as the SPRINT-E should never be ignored. Counselors should be encouraged to use multiple methods to identify clients with suicidal ideation and not totally rely on their previous experience and training.

Limitations

Several study limitations should be noted. Although interviews with counselors may have been affected by recall bias and not all details may have been recalled with as much specificity as desired, the counselors indicated that their encounters with clients expressing suicidality were more memorable than their impressions of clients who were only struggling with disaster-related distress. However, this study is limited by the small number of crisis counselors who were interviewed about their interactions with clients who endorsed suicidal ideation. Future studies should examine the experiences of crisis counselors who encountered clients with disaster-related suicide ideation.

The small sample of clients with suicidal ideation limits external validity. Although this study is enlightening regarding the concerns of counselors who treated clients with suicidal ideation, it only partially answers the question of how hurricane survivors with suicidal ideation use behavioral health services, as service use data for 3 of the 7 clients was unavailable. Finally, this study did not have data on these clients' level of functioning before the hurricanes. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to examine the experiences of counselors who treated clients with suicidal ideation.

Conclusions

Natural disasters may have deleterious effects on the mental health of survivors, including suicidal ideation as well as related depression, hopelessness, and PTSD. The ability of counselors providing disaster behavioral health services to give adequate care to survivors experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors is essential. In addition to evaluating for depression, anxiety, or increased substance abuse, warning signs for suicide that should be assessed for among distressed survivors are listed in Table 3. In general, the more warning signs, the greater the risk for suicide. In addition to administering the SPRINT-E, crisis counselors should be well trained to detect these warning signs for suicide risk and take steps to insure the safety of the survivor. A standard suicide protocol should be developed for use by crisis counseling programs that are administered to affected populations in the aftermath of natural or human-made disasters.

Table 3 Suicide Warning Signs

Future research should include personal perspectives from disaster behavioral health service clients who are experiencing suicidal ideation. Identifying personal experiences, prior to and during natural disasters, that may have led to suicidal thoughts and behaviors may help to gain a better understanding of this particular client population. As new protocols are developed and implemented for disaster response, adequate training in suicide risk assessment for both counselors and paraprofessionals who respond to such events is imperative.