The events of September 11, 2001, followed by the anthrax attacks just 1 week later, highlighted existing vulnerabilities of the first-responder community in communicating and coordinating with health care partners.Reference Hanfling 1 In particular, the anthrax attacks proved that a large-scale disaster can primarily affect both health care and public health communities, yet require minimal effort from traditional first responders. This realization was the catalyst that led public health and medical leaders to create the Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) in 2002, with a primary focus on bioterrorism and utilizing a capacity-building approach centered around surge capacity, maintaining pharmaceutical stockpiles, decontamination, and disease diagnosis. 2 The field of preparedness is often reactionary, and it was quickly realized that the capacity-building approach for a low probability event was an inefficient use of funding. As such, in 2004, HPP shifted to an all-hazards, capability-based approach that required hospitals to demonstrate capabilities required to perform core functions common to all responses, rather than simply purchasing equipment. 2

The new federal program model had a significant impact on hospitals across the United States, and many facilities saw their preparedness levels substantially increase, with one major caveat. As demonstrated by the underwhelming responses to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009, hospitals had conducted the majority of their preparedness activities within the confines of their own infrastructure and seldom involved the community at large. As a result, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response of the US Department of Health and Human Services released national guidance for health care system preparedness that aligned the 15 Public Health Emergency Preparedness capabilities with the 8 HPP capabilities to form a synergistic workforce with a common operating picture. 3 This document also introduced and reinforced the concept of health care coalitions (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Alignment of Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Hospital Preparedness Program Capabilities.

By definition, a health care coalition is a group of health care organizations and public safety and public health partners that join forces for the common cause of making their communities safer, healthier, and more resilient. 4 The health care community has come to the realization that although all disasters start and end locally, they do not have a singular effect. It is incumbent upon all response partners, community leaders, businesses, etc to plan together to ensure resilience and improve overall outcomes. The main purpose of coalitions is to facilitate planning, communication, and coordination at the community level so that all resources are exhausted before reaching out to regional, state, and/or federal partners. By planning together with all response partners, community-level resources are identified and can be pooled. With preparedness funding steadily declining, pooling resources allows communities to jointly exercise scenarios at the top of their hazard vulnerability analysis rather than each individual agency conducting its own exercise that can be expensive and requires a tremendous amount of simulation.

The Georgia Model

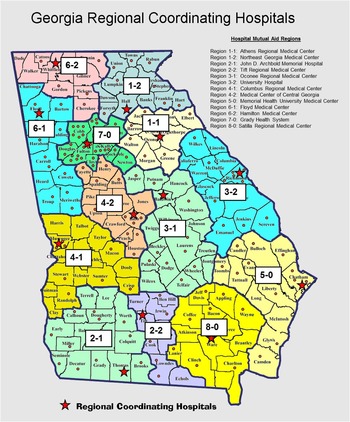

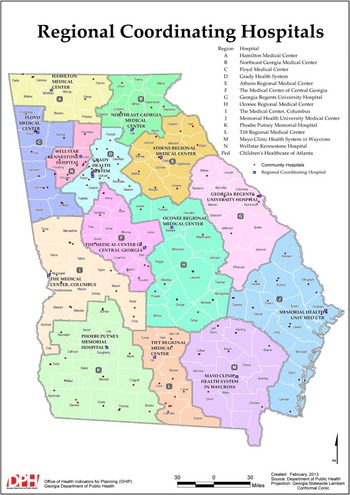

When HPP funding for coalition-based preparedness was first disbursed, each grant awardee was tasked with creating its own coalition model that would meet the needs of the health care response community. Leaders at the Georgia Department of Public Health (GDPH) were charged with deciding how best to generate an understandable, coalition map with regional lines that would allow for regional coordination yet still meet the state’s geographically diverse needs. Following the events of September 11, 2001, the Georgia Hospital Association (GHA) convened a group to explore preparedness gaps. This group was called the Mutual Aid Task Force and recommended that all hospitals enter into a Mutual Aid Compact and that a regional hospital system was needed. Each hospital in Georgia signed the Mutual Aid Compact and Georgia established the Regional Coordinating Hospital System through a joint venture of the GHA and the GDPH. Within this system, the state was divided into 13 Regional Coordinating Hospital (RCH) regions (Figure 2) with 1 hospital designated as the RCH lead expected to coordinate regional responses with the other hospitals. Selection of original Georgia RCH region boundaries was based around a division of health care populations and commonly utilized hospital and emergency medical services (EMS) referral patterns. Some regions are exceedingly large in terms of geographic area, whereas metro Atlanta, which is small in terms of land mass, is divided between 2 RCH regions. By fiscal year 2007-2008, Georgia realigned the RCH boundaries to include 1 additional region and a pediatric specialty coordinating facility (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Original Georgia Regional Coordinating Hospital Map.

Figure 3 Current Georgia Regional Coordinating Hospital Map.

Georgia is a home rule state with 159 counties divided into many different regions across many different disciplines with unaligned regional boundaries. For example, the 159 counties are divided into 18 public health districts, 14 RCH regions, 10 EMS regions, and 8 Georgia Emergency Management Agency areas. Workers in 1 public health district office may serve counties within 4 different RCH regions. Alternately, 1 RCH region may be divided among multiple EMS regions. This created an added layer of complication when seeking to identify agreeable coalition regions. Options included choosing an existing map and delegating existing regions as the state’s new coalition regions or scrapping existing options and drawing a completely new regional boundary map solely for health care coalitions. Following much deliberation and consultation with partners, leaders wisely chose to utilize the existing RCH region map and expand RCH leadership from a purely hospital coordinating function to one of health care community coordination. Regional response organizations (eg, public health districts, Georgia emergency management field coordinator, emergency medical services regions) did not change their boundaries to coincide with the coalition model but rather were asked to choose a coalition region where they had the most representation and identify in that coalition. Careful consideration was given to ensure that each coalition had representation from each response sector. Also, state public health officials attend all coalition meetings to ensure continuity of planning. This in turn created the earliest form of the 14 Georgia health care coalitions that exist today. While having overlapping regional boundaries among different response disciplines could create divisiveness if handled incorrectly, Georgia has utilized these redundancies to strengthen coalition capabilities. Georgia coalitions were afforded the opportunity to put their plans, policies, and procedures into practice during the major ice storm of 2014. During the event, regions G and H successfully engaged in the disaster response by supplying nursing homes and other long-term care facilities with life-saving medical and nonmedical supplies to sustain those vulnerable populations. This is one example of how Georgia’s coalitions have come together to help one another in a time of need.

Coalition Diversity

Within Georgia’s health care response community, it is often commented, “If you’ve seen one coalition, you’ve seen one coalition.” This statement is meant to reinforce the idea that both the state and the health care response communities serving each region are extremely diverse. Covering over 59,000 square miles, Georgia is the largest state in the United States east of the Mississippi River. In 2014, the US Census Bureau estimated Georgia’s census to be approximately 10.1 million persons 5 with almost half of the state’s residents living in the Atlanta Metropolitan Area. This in turn means that some coalitions serve extremely rural populations while others operate in a more urban environment. Some have large trauma systems and centers, while others include a larger percentage of critical access hospitals. Geographic diversity also means that identified top hazards and threats vary among the coalitions. For example, coastal coalitions work diligently on hurricane-based coastal evacuation plans while inland regions work to coordinate coastal health care receiving events. Ice storms and other winter weather may be significant threats for regions in north Georgia, but those in southern Georgia may have more concerns about wildfires and heat-related events.

Whereas some states may have been daunted by the challenge of finding a coalition model to fit the needs of such diverse regions, Georgia excelled by allowing each regional coalition group to develop its own leadership structure, including membership within a coalition executive team. Executive team members are generally a reflection of the overall coalition makeup and include representatives from health care organizations, district public health, and first responder agencies. Diversity of coalitions is also apparent in the types of member organizations that regularly attend meetings and participate in coalition activities. Although the RCH regions in 2002 were initially conceived to be hospital-centric, coalition membership now includes all health care organizations. Nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, hospice and home care organizations, behavioral health providers, dialysis clinics, federally qualified community health centers, military installations, volunteer and nonprofit groups, EMS providers, Veterans Affairs hospitals, local emergency management agencies, fire departments, and law enforcement agencies are just some of the groups joining in the coalition-based health care response efforts throughout the State of Georgia. Groups that typically compete for business during day-to-day operations are building relationships and supporting the coalition model for disaster response, which has helped improve disaster-related planning and coordination throughout the state. This has become especially apparent as regional coalitions continue to exercise newly developed regional emergency operations and coordination plans. Coalition exercises are conducted based on the Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program. In this model, participating organizations form an exercise planning team that seeks to integrate individual facility requirements with overall regional objectives. Every effort is made to ensure as many response partners participate in the exercise as possible to increase the realism of the event. However, it is understood that not every partner can, or is willing to, participate in exercises for a variety of reasons (eg, staffing and resource constraints, regulatory bodies conducting surveys on the day of the exercise, real-world events). To accommodate this realization, response partners have the option to participate via multiple modalities, including having a liaison either at the health care facility command center or in the county emergency operations center, participation via interoperable communications systems, or utilizing simulation cells to fulfill the role of a partner who cannot, or chooses not to, participate. At the conclusion of the exercise, a regional after-action report and improvement plan is generated to address operational gaps and update existing plans.

Conclusion

Developing coalitions can be an extraordinarily difficult process given the number of organizations involved, the geographic footprint of a given state, and the willingness of competing organizations to engage with one another in a mutually beneficial capacity. Fortunately for Georgia, an existing infrastructure, the RCH model, was already in place that allowed for a near seamless transition into coalitions. For 8-plus years the RCH system effectively fostered collaboration and coordination of first responders, public health, and hospital organizations. However, since the development of coalitions, additional organizations, both health care and non-health care, have come on board and identified new and emerging disaster-related issues, not previously considered. Reconciling these issues is, and will continue to be, a difficult endeavor as money and resources are declining year by year while the need for these assets is significantly expanding. Georgia coalitions are still very much a work in progress. We are learning on a daily basis how important it is to continue to work together to understand the needs of the community as a whole and how to most efficiently utilize available money and resources to serve the greater needs of the community.