UNPRECEDENTED EVENT

At 4:53 PM on January 12, 2010, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake shook Haiti for 43 seconds. It was the worst natural disaster in a country plagued by disasters. By many measures, it was the worst natural disaster in modern history (Table 1). The earthquake destroyed the capital of the poorest country in the Western hemisphere and incapacitated a government and health care system weakened by decades of mismanagement, corruption, and dependence on foreign assistance. In addition to the Haitian people, victims of the event included the Haitian government, the United Nations (UN), and the US embassy. The costs of reconstruction have been an estimated $14 billion.Reference Cavallo, Powell and Becerra1

Table 1. Deadliest Natural Disasters 1970-2010a

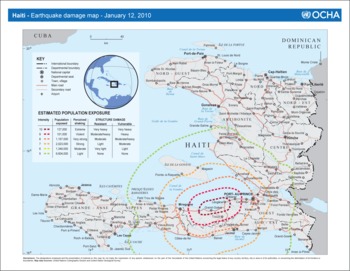

The epicenter was 25 km from the densely-populated capital Port-au-Prince (Figure 1). An estimated 97 000 dwellings were destroyed and 188 000 were damaged, resulting in 222 750 dead, 300 572 injured, and more than 1.5 million homeless.2 At the end of May 2010, there were still 1342 sites of internally displaced persons.3 Many government buildings were destroyed, including the national palace, parliament, supreme court, 14 of 16 ministry buildings, major courts and police facilities, and 90% of schools in the Port-au-Prince region.4 Almost one-third of the country's 60 000 civil servants died, including 2 senators, and many senior political leaders were injured. Almost everyone in the government lost family members or friends, which made the already weak government even less capable of responding.

Figure 1. Earthquake Damage Map, United Nations, Haiti 2010. From the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

UNPRECEDENTED SETTING—HAITI

Haiti is one of the poorest nations in the world, with 80% of the population living below the poverty line.5Reference Rencoret, Stoddard, Haver, Taylor and Harvey6 In 2006, 42% of the population lacked access to safe water and 81% had no access to adequate sanitation.7 More than 2.4 million people were food-insecure, and 23% of children younger than 5 years suffered from chronic malnutrition.89

The population of Port-au-Prince, an estimated 3 to 3.5 million, has expanded by more than 40% since 1982.10 Before the earthquake, more than 85% of the urban population lived in unplanned slums in haphazard housing built from cinderblock and poor-quality cement.Reference Rencoret, Stoddard, Haver, Taylor and Harvey6 Most slums have no building codes, municipal services, or roads, and are connected only by narrow paths between crowded structures (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Port-au-Prince Neighborhoods, January 2009.

At the time of the earthquake, Haiti's government was barely functioning; it was rated as one of the most corrupt in the world.11 Public services such as education, sanitation, and health care were often provided by private institutions or nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and not by the government. As a result, the government lacked the financial resources, management, and leadership infrastructure to respond effectively. Haiti also has no standing army, fire, or prehospital services, and only a small, unprofessional police force, which represented the usual core of local disaster response. Finally, Haiti has a long history of political and civil violence. To provide for stability and law and order, the UN established the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) as a peacekeeping force in 2004, following the removal of President Aristide.12

Haiti has had a complex relationship with the US government, including long-term financial support and prior interventions by the US military. Because Haiti is also only 600 miles from Florida, it was easily accessible by the media, US response agencies, and thousands of individuals wanting to help. These factors led to an unprecedented response from the US government, which closely resembled a multi-agency domestic disaster response rather than a limited foreign one.

UNPRECEDENTED RESPONSE

The response was rapid and massive in scope, but the leadership and logistical support were not sufficient to manage the scale of response, particularly during the first month after the disaster. The unrelenting and sometimes sensationalized media coverage amplified the frenzy of the relief efforts.

The Government of Haiti's Response

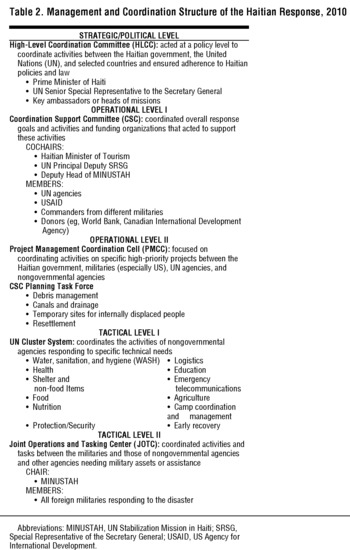

The Haitian government was severely affected by the earthquake. In addition to the loss of ministry buildings, the national disaster risk management system sustained heavy losses, and the emergency operations center was destroyed. Local police stations collapsed, killing staff and destroying vehicles. In spite of their losses, the government attempted to coordinate relief efforts with the assistance of the US government and international agencies. Within two weeks, a government response framework led by the high-level coordination committee (HLCC), the coordination support committee (CSC), and the presidential commission on recovery and reconstruction was created. It included the UN, development agencies, international militaries, and bilateral donors (Table 2). The government also established working groups to coordinate efforts with the UN clusters. The US embassy provided critical logistic and communication support to the Haitian president and prime minister and collaborated with the World Bank to fund government of Haiti emergency response projects, including rebuilding the state's capacity to operate. In addition, the World Bank took over the payroll functions of the government employees to encourage their return to work.

Table 2. Management and Coordination Structure of the Haitian Response, 2010

A post disaster reconstruction assessment by the Haitian government, the UN, the Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank, and the European Union led to the government's “Action Plan for the Reconstruction and the Development of Haiti.” The action plan estimated that $3.9 billion was needed for the first 18 months and $11.5 billion for long-term reconstruction. On March 31, 2010, the plan was presented to an international donors' conference, where more than $9 billion was pledged, $5 billion of which was for 2010-2011.13

International Response

Search and Rescue

In total, 67 international urban search and rescue teams from almost a dozen countries deployed to Haiti and made 136 live rescues.141516 The first teams, including one from the United States, arrived the day after the event, and by day 4 there were 26 teams in Haiti. The US government deployed six teams with 511 members, four of which were domestic teams supported by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. They made 47 live rescues, at the cost of $51 million.17 On January 26, 2010, the Haitian government called off search and rescue efforts.18

THE UNITED NATIONS

The UN headquarters collapsed, killing 101 UN staff including most MINUSTAH leadership, making the UN a victim and devastating its response capacity.19 With the loss of local leadership, the UN struggled to respond and collaborate. Their effectiveness was further complicated because humanitarian response was not part of MINUSTAH's mission. This shortcoming was resolved when the UN Security Council extended MINUSTAH's mandate to include humanitarian activities and provided additional personnel. Even Sir John Holmes, the Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs, criticized UN management and specifically the UN's delayed implementation of the cluster system.Reference Lynch20

The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is the UN agency that leads international humanitarian response. OCHA immediately deployed a disaster assessment and coordination team to begin organizing. The MINUSTAH logistics base at the airport became the center of operations for the UN and many NGOs. UN leaders sat on or cochaired key response committees including the HLCC and CSC. To better coordinate with the military response, MINUSTAH and OCHA established a joint operations and tasking center (JOTC) with militaries from the United States, Canada, the European Union, and the Caribbean.21

OCHA and the Inter-Agency Standing Committee implemented the UN humanitarian cluster system to manage and coordinate the response. Most headed by UN agencies, each of the 11 clusters cover a technical area such as water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), nutrition, health, security, and others. The cluster system, in general, did not function well early in the Haitian response for numerous reasons. The UN was not sufficiently staffed, leaders had limited experience, facilities were insufficient, and the sites were overwhelmed by the number of attendees at meetings. For example, more than 400 organizations attended the health cluster meetings, which are usually attended by 15 to 20. Furthermore, some cluster meetings were held in English, and local officials and NGOs were unable to participate. Intercluster coordination was also weak; no interagency coordination meeting occurred for three weeks. Management improved gradually as more senior and experienced UN and OCHA leaders were deployed. In February, a high-level coordinating body, the humanitarian country team, was established to address key strategic issues.

THE MILITARY

Twenty-six countries provided military assets including field hospitals and hospital ships, transportation (air and sea), troops for security, and heavy equipment. The United States provided the largest contingent, with a total of 22 000 troops involved in the overall response. The CSC oversaw strategic coordination between the Haitian government, UN, and all of the military forces, while the JOTC provided operational coordination between military forces and the humanitarian community.

One of the greatest difficulties in the response was that the infrastructure was not sufficient to absorb the massive volume of equipment, personnel, and supplies arriving. Much of it simply piled up, and personnel waited for days to receive an assignment. Historically in a foreign disaster, specific needs are identified by the host country or international assessment and then resources are requested and brought into the field. The Haitian response was more like a US domestic response, in which resources are prepositioned and “pushed” into the field and are not based on needs assessments but on a historical knowledge of a specific disaster's impact. Pushing resources into a country without local infrastructure to support their use is inefficient and expensive and makes the response more difficult.

NONGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS

In the first year after the disaster, charities raised $1.4 billion for the Haitian response.Reference Lieu22 An estimated 2000 NGOs responded to Haiti, including 400 providing health care3; few had previous experience or the skills and tools needed for such a complex environment. The UN cluster system struggled to incorporate these NGOs but was overwhelmed by their numbers and lack of experience. The onsite operations and coordination center attempted to coordinate Haitian authorities and organizations with international NGOs but with limited success. InterAction and International Council of Voluntary Agencies tried to establish principles of coordination for the NGOs through an NGO coordination support office.

US GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

Management of the US response to foreign disasters is led by the US Agency for International Development's (USAID) Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). The OFDA works with the local US embassy and within the UN response system to assist the affected country's government. The OFDA uses a response management team in Washington and a disaster assistance response team (DART) that deploys to the affected country. The DART's functions are assessment, coordination, and technical support; delivery of relief supplies; grant making; and monitoring and evaluation. The response management team manages the DART from Washington and coordinates with the military, other US agencies, the Congress, and key stakeholders.23

According to international law, the Haitian government had the primary responsibility for the response, but because of the scope of the catastrophe and the loss of Haitian and UN capacity, other leadership was needed.24 To a large extent, the US government and military filled this vacuum. The US government had the largest number of personnel and contributed the largest amount of all countries, totaling $1.1 billion in six months (Table 3). The proximity of Haiti to the United States and the prior history between the countries led the president to call for a “whole of government” response that was an unprecedented departure from the normal foreign disaster response and was more typical of a domestic response. USAID OFDA technically remained the lead, but it was augmented by other agencies including the departments of Defense (DoD), Homeland Security (DHS), State, Transportation, Treasury, and Health and Human Services (DHHS), among others. With so many agencies responding and a high-level of political involvement in Washington, new leadership and management approaches were needed.25

Table 3. Total US Government Funding for the Haitian Responsea

The response was ultimately led by a committee of senior officials from National Security Council, State, USAID, and the DoD in Washington. However, the management structure evolved rapidly and led to new positions, participants, and committees being added and replaced during the first month. Two important new management structures were created: the Interagency Task Force in Washington and the Office of the Response Coordinator (ORC) in Haiti. The task force served an operational role, with representatives from more than a dozen agencies and the military. It was intended to augment the response management team but often worked in parallel with limited coordination. Many of the participants in Washington had limited experience in disasters or humanitarian response, leading to further difficulties in the chain of command and limiting the autonomy of the OFDA in Washington and Haiti.24

In Haiti the staff of the US embassy was also affected by the earthquake, losing homes and friends. The initial focus of the embassy was to support the Haitian government, the well-being of staff, and the safety and evacuation of nearly 17 000 Americans. However, the embassy was almost overwhelmed by hundreds of US staff from a dozen agencies and the military seeking to establish operations and living quarters in Haiti. The embassy did not have the space, resources, or staff to support all of the responders and many (including disaster medical assistance teams) were trapped on embassy grounds for days due to lack of vehicles, drivers, and interpreters.24

The response in Haiti also deviated significantly from the past in terms of the number of US government agencies and personnel involved, the massive presence of the US military, and the creation of the ORC.26 The traditional leader of the US response, the OFDA-DART team, had at most 34 specialists physically in Haiti, while the US military had 8000 troops on the ground. In spite of this, USAID provided more than $400 million to address food, water, health, and shelter needs within six weeks.27 Because the DART did not have the capacity or authority to manage the many US agencies in Haiti, the ORC was created.28 Headed by a special ambassador, the ORC was supposed to coordinate activities for the entire US response, but the role was not well-defined or well-communicated and was understaffed, with a limited budget and no logistical resources. The many different leadership positions in the country (ie, the military, the ambassador, the DART, and the ORC) led to tensions among agencies and initially added to the coordination difficulties.

US Military

The DOD has unique disaster response capabilities in logistics, transportation, assessment, and security, and a great availability of human resources.29 In Haiti, the US military played a much larger role than usual, including one of the largest medical outreaches in history,30 because of the leadership vacuum, the overwhelming logistic needs, and the initial security concerns.28

The military response, called “Operation Unified Response” was conducted by Joint Task Force-Haiti under the direction of the Southern Command. The military's initial priorities were search and rescue, to support MINUSTAH in law and order operations, re-establish the logistic infrastructure (including the airport and port), deliver relief supplies, and direct medical response. Other activities included the evacuation of American citizens, the transportation of American and Haitian patients, and the repatriation of American citizens' remains to the United States.28

The military response was swift and massive. Within the first 10 days, the US Navy deployed 17 ships, 48 helicopters, and 12 fixed-wing aircraft to Haiti, and eventually more than 22 000 military personnel responded.4 The military provided heavy equipment, field hospitals, hospital ships and cargo ships, and made air deliveries of water, food, medical supplies, and non-food items. The Haitian government gave the US military control of the airport and port, and within 72 hours the US Air Force replaced the air traffic control system and increased daily landings from 30 to 140.Reference Garamone31

The early difficulties with the response management led the US military to play an enhanced role in coordination, planning, and leadership from strategic to tactical operations. In spite of concerns about the military's role in humanitarian response, other agencies recognized that the US military had the greatest resources and personnel and was acting to improve the capacities of the civilian coordination authorities.28 Although the military received some criticism regarding their leading role, generally they received praise, especially for re-opening ports, logistical capacities, and the low-key approach used to improve security.

KEY SECTOR ACTIVITIES

In spite of all of the difficulties and confusion in the early response, remarkable achievements also occurred.3 Some of the activities in the key sectors are included in the following sections.

Assessment

Information management was a major difficulty. OCHA was the focal point of assessment, but had limited staff and budget, so the agency relied on NGOs to collect and report through the UN clusters. However, NGO staff may have had little assessment training or skills, and the data that were collected were not consistent in content or collection methods. Dozens of different agencies, government, the military, and NGOs collected data, but compiling and sharing the results was limited in spite of innovative methods such as OneResponse and the US military's all partners access network.32 For example, the largest formal assessment, the rapid interagency needs assessment in Haiti began on January 23 but was not released until February 22. The results were not considered useful because of the delay and concerns about methodological flaws.Reference Bhattacharjee and Lossio33

Health

Prior to the earthquake, Haiti's health care system reached only 50% of the population, and the health indicators were essentially the worst in the Western hemisphere.7 Even in normal circumstances, Haiti's health care facilities could not care for 300 000 injured. With the Ministry of Health building collapsed, more than 200 staff dead, and 60% of hospitals in the Port-au-Prince area damaged, most institutions were incapable of providing services.3

The international health care response to the earthquake was massive but generally inefficient and poorly organized. Almost 400 organizations registered with the health cluster to provide health care.3 Field hospitals were deployed by many nations, and medical volunteers, especially surgeons, responded in large numbers. Many spontaneous volunteers or groups simply flew to Haiti to offer help, but often with little equipment, supplies, training, or logistic support. This influx created further confusion, made the response more difficult to coordinate, and used scarce resources. The United States deployed military health care assets, including the USNS Comfort on January 20, and disaster medical assistance teams from DHHS.

The deployment of so many specialized surgical assets led to complex operative procedures uncommon in Haiti. This, combined with the rapid rotation of health care providers (usually every one to two weeks), created problems with postoperative and long-term care. The USNS Comfort filled up with postoperative patients who had no homes; consequently, they could not be discharged and returned to overwhelmed hospitals. Resources were created for those with complex injuries and for those who needed long-term care, with variable success. Patients were transported to hospitals in the United States, plans were made for additional US government field hospitals, and NGOs began to provide these services.

Food and Nutrition

The initial response to the earthquake in Haiti involved the distribution of ready-to-eat-meals, food rations, and rice to prevent the development of a hunger crisis. Within a week, the World Food Programme had provided more than 200 000 people with more than 1 million food rations.34 Included were 550 000 children and pregnant or lactating women who received supplementary food. When the Haitian government ended distribution in March, more than 4 million people had received food.

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene

Providing clean water was accomplished quickly, but poor sanitation remained an issue. Within a month the Port-au-Prince water authority was producing more clean water than before the earthquake, increasing from 80 to 90 million liters to 120 to 150 million liters per day.35 By May, 1.3 million people were receiving treated water, and more than 11 000 latrines had been built.36

Shelter

In the first two months of the response, 277 000 tarps and 37 000 tents were distributed.3537 The shelter cluster estimated that 100 000 people per week were assisted during the first four months. By June, USAID/OFDA alone provided more than 1.3 million individuals with plastic sheets.353738 More than 1.5 million people received emergency shelter materials, and 2.1 million households received non-food items. In the reconstruction phase, the types of shelters shifted to long-term transitional structures, but by June only 96 504 transitional shelters were funded, including 47 500 by USAID/OFDA.39 One year after the event, almost 1 million people remained in temporary shelters.40

Rubble was a major impediment to the emergency response, and remains a problem for housing reconstruction and development. The earthquake generated 25 million tons of rubble; after six months, less than an estimated 1% had been cleared.

LESSONS LEARNED

The greatest lessons from the Haiti response are not new. They revolve around the difficulties of managing a complex operation in a resources-constrained environment when the surge capacity of the world is very limited.

Managing International Disaster Responses

The established systems to manage global disasters did not function well initially in the Haitian catastrophe. The UN struggled to recover and provide leadership, and the cluster system did not function well early in the response. The US government also struggled initially to adapt the existing management structure to a massive government-wide response as the emergency unfolded. Haiti was a particularly complicated event, but the UN cluster system has not functioned well on other occasions.Reference Steets, Gruenwald and Binder41 A more robust management and reporting system is needed, with more experienced leaders and a staff that can be rapidly deployed. Also, the USAID/OFDA structure was not sufficient to manage a government-wide response.

The domestic National Response Framework,42 a management structure that is flexible and scalable to address all hazards, could be a potential template for a more scalable response for the US government to catastrophic foreign disasters. This more hierarchical structure can be used to better integrate all different departments/agencies of the government, including the DoD and nontraditional global responders such as the DHHS. Such a structure will also reduce duplication and redundancy and, because of the unified chain of command, it may be easily integrated into the UN systems.

Surge

Disasters are rare events, and catastrophes are even less common, so relatively few persons are employed fulltime to respond. Even within international agencies and national governments, the number of disaster-specific positions can be counted in the hundreds. NGOs, even those with a focus on disaster response, are unable to maintain a readily available cadre of experts. Much of this scarcity is due to lack of funding. Little overhead is given to NGOs to maintain a larger staff for surge capacity; public perception is that all money donated for a disaster should go directly to the victims, which leaves no funds to develop the infrastructure needed to respond.

To improve surge capacity disaster response, personnel could come from a number of sources. The military is an obvious source, with personnel familiar with austere environments, but there are problems with mission, politics, and humanitarian law and precedents. Other sources of trained, experienced personnel could include retired government staff, academic institutions, and pools of volunteers such as the medical reserve corps and citizen corps. Included should be minimum experience and training standards for those eligible to deploy.

Civilian-Military Coordination

The US military's mission now includes humanitarian assistance and disaster response (HADR).This capacity combined with their human, logistics, and equipment resources make the military a key actor in global disaster response. There is a need for greater collaboration with the humanitarian response community, but the military faces difficulties. First, the military is not impartial, as required by humanitarian principles, leading to concerns in the humanitarian community about political motives. Second, the military lacks HADR institutional knowledge, because there is no career path in this area or centers or commands that focus on the HADR mission to the same standards as in other military missions. To meet its HADR mission, the military will have to develop institutional and managerial infrastructure.

Information and Data Management Systems

Information gathering and analysis was extensive, but not well coordinated or shared. The lack of standardized data collection methods, baseline parameters, and unified collation and analysis limited the utility of all the collected data.3

A more standardized system needs to be implemented, and data should be collected, analyzed, and distributed by an independent group that is not actively delivering aid. Especially early in a response, the limited human resources are overwhelmed by the direct aid needs and are unable to also effectively manage information. Standardized assessment methods and forms across agencies are needed to make reporting easier, more accurate, and more consistent.

Health Care Response

The health care response to the Haitian disaster was massive but fractured, and delivered services that were not sustainable by the existing health care system. It was also burdened by well-meaning but inexperienced and untrained individuals and organizations attempting to deliver services. International standards for training, staffing, and logistics should be set for NGOs, field hospitals, and individuals responding to disasters. These standards are already being proposed by the World Health Organization/PanAmerican Health Organization.43

CONCLUSION

The catastrophe in Haiti was a difficult response for the international humanitarian community as well as the US government. In spite of the complexity of the response, many successes were achieved. The lessons learned point to solutions that have been under discussion but not yet implemented. Some lessons, such as difficulties implementing the UN cluster system, the need for better civil-military integration, and the need to improve data management continue to require added attention.