On October 6, 2015, the White House launched the Stop the Bleed initiative. Stop the Bleed seeks to build personal resilience and safeguard the nation by empowering the public to stop life-threatening hemorrhage. 1 , Reference Jackson 2 This initiative, created by a 2-year federal government interagency working group, is built on more than a decade of US military research showing that rapid bystander action is essential to surviving severe traumatic injuries on the battlefield.Reference Kotwal, Montgomery and Kotwal 3 , Reference Eastridge, Mabry and Seguin 4 The Hartford Consensus, an expert group formed in response to a 2011 presidential national preparedness directive, has consistently emphasized that bystanders are “immediate responders” and are key to providing point-of-injury hemorrhage control.Reference Jacobs 5 , Reference Jacobs, Wade and McSwain 6 Trauma victims can bleed to death from severe wounds in minutes. Therefore, immediate hemorrhage control by bystanders at the time of injury may save lives during terrorist attacks or other disasters prior to the arrival of emergency medical providers. The Hartford Consensus calls for the placement of “bleeding control bags” to empower responders and recommends increased public education about effective hemorrhage control. Stop the Bleed, through its national focus on hemorrhage control, will boost preparedness and provide laypeople access to effective personal and public bleeding control kits. 1 , Reference Jackson 2

While this landmark effort may prove immensely beneficial for future trauma victims, much remains unknown about optimal devices and ideal just-in-time (JiT) training methods for layperson responders. Recently, Schroll et alReference Schroll, Smith and McSwain 7 compared the use of tourniquets in the civilian population to previous military studies. The investigators analyzed patients brought to 9 level 1 trauma centers and discovered that 89% of them had effective hemorrhage control via tourniquet placement. Interestingly, 20% of these patients had makeshift tourniquets placed by nonmedically trained bystanders prior to arrival by emergency medical services. In a precursor study to this one, Goolsby et alReference Goolsby, Branting and Chen 8 showed that JiT instructions more than double the proportion of successful tourniquet applications by untrained laypeople from a baseline of 20% success without instructions to 44% with instructions.

This study evaluated layperson success utilizing a modified color-coded tourniquet designed for layperson use versus a black Combat Application Tourniquet (C-A-T; Composite Resources, Rock Hill, SC). Data collected in this study provide evidence of laypeople’s ability and willingness to provide life-saving hemorrhage control.

Methods

Study Design

This was a prospective randomized study. The Uniformed Services University (USU) Institutional Review Board approved this study as an exempt educational protocol (#404505-4).

Study Setting and Population

Investigators from USU recruited study participants on the University of Maryland campus in College Park, Maryland, during the Maryland Day celebration. Investigators used posters asking for volunteers to test a potentially life-saving medical device. Maryland Day is a public event drawing more than 50,000 guests annually. Data collection occurred on April 25, 2015, over a 6-hour period.

A total of 218 volunteers completed pre-study questionnaires to determine eligibility and 157 people completed the study (Figure 1). Baseline comfort levels and attitudes about tourniquets were collected via the pre-study questionnaire. Demographic data were collected through a post-study questionnaire after the participant had attempted the tourniquet application (Table 1). A participant was excluded for being aged less than 18 years, having served in the military in the past 15 years, having had prior tourniquet training or use, having a history of being a licensed medical provider (physician, nurse, medic, etc), or having had medical training beyond that consider to be included in a high school health course or basic first aid/CPR.

Figure 1 Participant Enrollment and Exclusions. Abbreviation: JiT, just-in-time training. A participant was excluded for age less than 18 years, military service in the past 15 years, prior tourniquet training, or a history of being any type of licensed medical provider (physician, nurse, medic, etc).

Table 1 Demographic Data of the Participants in the Two Study Groups

a Based on a t-test for independent samples.

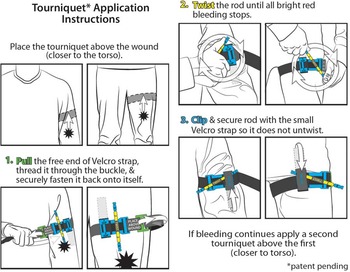

Investigators developed the color-coded tourniquet used in this study on the basis of feedback from a pilot study conducted in 2014.Reference Goolsby, Branting and Chen 8 The color-coded tourniquets contain fluorescent colors designed to guide participants through the application process. Printed instructions on the tourniquet, labeled, “pull, twist, and clip,” attempted to simplify the process. The modified tourniquet also contained a mechanism to block participants from threading the buckle through the strap incorrectly. A professional medical illustrator on our team created an instruction card (Figure 2).Reference Goolsby, Branting and Chen 8

Figure 2 Tourniquet Application Instructions.

Study Protocol

A participant was randomized in a 1:1 ratio via an online block randomization generator into the color-coded tourniquet test arm or the black tourniquet control arm. The participant then followed the primary observer back to a private testing area. The primary observer read aloud a scenario describing an explosion at a public event. The primary observer then asked participants to apply a tourniquet to the lower limb of a static lower-body mannequin (waist-down) with a simulated wound that served to indicate the site of injury. The lower-body mannequin was located on a table in the testing area and did not bleed during the study.

A participant tested individually with his or her primary observer assessing successful tourniquet placement. The primary observer began timing the application upon handing the participant a tourniquet, with a 4-step illustrated JiT instruction card, at the end of reading the scenario aloud. The participant had access to the JiT card for the full duration of the experiment. Both arms of the study received the same JiT instruction card. The participant applied the tourniquet until he or she indicated completion, or until 7 minutes had passed, at which point the primary observer stopped the procedure. Afterwards, the participant left the study area to complete the post-study questionnaire, which collected demographic and qualitative information about the participant.

During this time, a secondary observer, if available, independently assessed the efficacy of the tourniquet placed by the participant. There were too few secondary observers to witness each tourniquet placement; however, 117 of 157 participants were observed by 2 observers. The secondary observer did not witness the participant placing the device. The primary and secondary observer independently assessed the tourniquet to determine whether it was successfully applied and recorded their decisions on separate observer forms. The observers noted the anatomic position of the tourniquet and whether the straps and windlass were properly utilized and secured. The appropriate tightness was determined as a combination of the tourniquet distorting the underlying mannequin flesh and an observer being unable to force his or her index and middle fingers (held side-by-side and laid flat on the mannequin) between the tourniquet and the mannequin leg. If the participant did not apply the tourniquet appropriately, the observers documented the reason(s) for failure. If either observer thought the participant had failed, the application was deemed a failure during data analysis.

Eight observers were utilized in this study. No feedback was given to the participant until after they had completed their post-study questionnaire. The entire process took less than 15 minutes. The C-A-T was chosen for this study, instead of other tourniquet devices, because of the US military’s success with its use by nonmedical soldiers on the battlefield and previous evidence supporting its use by laypersons supplied with JiT instructions.Reference Kotwal, Montgomery and Kotwal 3 , Reference Eastridge, Mabry and Seguin 4 , Reference Goolsby, Branting and Chen 8

Outcomes

The study’s primary outcome was the proportion of successfully applied tourniquets by participants receiving color-coded tourniquets compared to participants who received black tourniquets with identical JiT instructions. Secondary outcomes included the median time for successful tourniquet placement, reasons for failed tourniquet application, and self-reported subjective assessments of participant willingness and comfort of using tourniquets in potential real-life settings. The possible influence of demographic variables was also investigated. Finally, an assessment of inter-rater reliability was conducted.

Data Analysis

Comparisons between the color-coded and black tourniquet group (Table 1) were made by using chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests for proportions. Mann-Whitney testing was completed for comfort level and time to successful application. Paired pre-post comparisons were made by using the Stuart-Maxwell test for willingness to use a tourniquet and the Wilcoxon signed ranks test for comfort level. The target sample size was 192 with a 1:1 ratio of color-coded to standard issue black C-A-T tourniquets to have 80% power to detect a significant difference if the proportion of correct applications was 65% vs 45%. The achieved sample size of 157 has 71.2% power for the same comparison. Data were analyzed by using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Participants

Analysis of participant demographics according to their randomized placement in the test or control group revealed no statistically significant differences between groups by sex, age, race, education, or income (Table 1). In a multivariate model adjusted for sex, age, race, education, and income, there were no significant differences in success rates for any of the demographic variables.

Primary Outcome

A total of 157 participants finished the study and all were utilized in the data analysis. All participants received JiT instructions. A total of 72 participants received color-coded tourniquets, and 51.38% of this group (n=37) successfully applied the device. A total of 85 participants received a black tourniquet, and 44.71% of this group (n=38) successfully applied the device. The 6.67% difference between the color-coded and black devices was not statistically significant (risk ratio [RR]: 1.15; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.83-1.59; P=0.404, chi-square test).

Secondary Outcomes

The median time for successful application (excluding failed applications) in the color-coded group was 100.5 s (interquartile range [IQR]: 78-137) compared with 82 s (IQR: 64.5-109.5) in the black tourniquet control group. This was an increase of 18.5 s in the test group compared with the control group (P<0.05, Mann-Whitney U test).

No statistically significant differences were detected between the color-coded and black devices in terms of reasons for failed applications (Table 2 ). Applying the tourniquet too loosely was the single leading reason for failure.

Table 2 Comparison of Factors Observed Throughout the Tourniquet Application ProcessFootnote a

a Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; JiT, just-in-time training.

b Calculated by using chi-square test unless otherwise indicated.

c Calculated by using Mann-Whitney U test.

d Calculated by using Fisher’s exact text for small number of subjects.

Before the study, 40.8% of the participants reported that they would use a tourniquet in a real-life situation; after the study, this percentage was 80.3% (P<0.05, Stewart Maxwell test). The participants’ self-reported comfort level using both devices rose significantly from before to after the study (P<0.05, Wilcoxon signed ranks test; Table 3).

Table 3 Analysis of Participant Opinions and Perceived Comfort With Using Tourniquets

a Unless otherwise indicated.

b Calculated by using the Stewart-Maxwell test across all groups.

c Calculated by using Wilcoxon signed ranks test for nonparametric analysis of paired ordinal data.

d No statistically significant difference between black and color-coded tourniquet groups (Mann-Whitney test).

e Calculated by using Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric comparison of independent groups.

In the assessment of inter-rater reliability, 117 of the 157 participants were observed by 2 observers. There were 8 total observers, with each seeing an average of 34 application attempts as either the first or second rater. For the 117 participants rated by 2 observers, the observers agreed on 56 successes and 54 failures (94% overall agreement) and disagreed for 7 participants, yielding a kappa statistic of 0.88.

Limitations

This study had important limitations. It assessed the technical skill of tourniquet application without assessing laypeople’s ability to recognize indications for tourniquet use. The study occurred in a controlled environment that differs from the stressful environment a layperson might experience during a real traumatic situation. Soliciting study participants with posters could introduce selection bias. It is not possible to know if those who volunteered for the study are more or less likely to attempt tourniquet placement during a real-life event. This study involved a limited sample size thereby increasing the potential for a type II error. The time constraints of our study design resulted in too few participants enrolling. The Maryland Day activity is a single-day event that occurs annually. Although enough participants volunteered initially, our exclusion criteria appropriately eliminated too many to reach the desired sample size. We elected to analyze and report these findings rather than waiting another year to collect additional data. Finally, the JiT instruction card contains illustrations, but written and verbal instructions were provided only in English.

Discussion

Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for Americans aged 1 to 44 years and claimed 46,019 lives in 2013. 9 Furthermore, it is possible that there may be an increase in combat-type injuries inside the United States as a result of penetrating trauma and mass casualty events like those seen at the Boston Marathon bombing. Similar to the concepts that underpinned the out-of-hospital cardiac arrest movement, empowering bystanders with the knowledge and tools to act during a traumatic injury may prove vital to saving lives.Reference Kellermann and Mabry 10

Tourniquets have repeatedly been shown to be safe and effective when used by bystanders on the battlefield, and Stop the Bleed’s recent launch serves to translate these lessons to the general public.Reference Kotwal, Montgomery and Kotwal 3 - Reference Eastridge, Mabry and Seguin 4 , Reference Kragh, O’Neill and Walters 11 , Reference Mabry 12 This study provides important baseline information about laypeople’s ability and willingness to use tourniquets during an emergency.

Given the exceptionally small body of literature looking at layperson tourniquet use, this study serves the important role of reproducing the results found in Goolsby et al’s pilot study of layperson tourniquet use while exploring a color-coded device. About half of laypeople can successfully apply tourniquets using JiT instructions. The numbers for black tourniquets in the present study match our previous pilot study data almost exactly: 44.71% success in this study and 44.14% in the prior study.Reference Goolsby, Branting and Chen 8 While 51.38% of participants successfully applied the color-coded tourniquet, there was no statistically significant difference between the color-coded and black tourniquet groups. Our study was designed with a significance level of 0.05, at a power of 80%, to show a minimum improvement of 20 percentage points from the control group. This design would have required 96 participants in each of the control and test arms, a target we did not quite reach. A 50% success rate may not seem high to some readers, but in fact these results are encouraging. This success rate is similar to those found when assessing CPR skill retention.Reference Einspruch, Lynch and Aufderheide 13 Additionally, Kragh et al demonstrated that partially effective tourniquets result in lower mortality rates compared to uncontrolled hemorrhage.Reference Kragh, Walters and Baer 14 As we have seen during other mass casualty events, like the Boston Marathon Bombing, it is likely a crowd will contain people with more experience than the general public; a nurse, or EMT, or army soldier might also be available to respond, which would likely boost overall success rates. In addition, Stop the Bleed will increase the availability of public hemorrhage control kits. These bags will include tourniquets and bandages that might be mounted on the wall next to an AED (automated external defibrillator). If half of laypeople can successfully apply a tourniquet with JiT instructions, and a supply of tourniquets is nearby, it is quite possible bystanders could prove very successful in controlling exsanguinating hemorrhage.

In addition to technical skill, determining laypeople’s willingness to use tourniquets is important. This study found that 80% of laypeople expressed willingness to use the device after a brief exposure to it during the course of this study. This doubled the prestudy willingness proportion of 40% and is consistent with the 84% of laypeople who expressed willingness to use the device after brief exposure in our preceding pilot study.Reference Goolsby, Branting and Chen 8 This number will likely grow as the Stop the Bleed message reaches an ever-larger population. Interestingly, the percentage of laypeople willing to use a tourniquet in these 2 studies is very similar to Urban et al’s 2013 study that reported that 77.8% of people are willing to perform hands-only CPR on a stranger.Reference Urban, Thode and Stapleton 15 We also noted statistically significant increases in participant comfort using either device following brief exposure during the study.

The study quantified the median time for successful tourniquet application as 82 to 101 s. This time range is less than the median of 108 s found in our previous pilot study and is likely secondary to the shorter illustrated instructions used in this study compared with those utilized previously.Reference Goolsby, Branting and Chen 8 The time frame for exsanguinating hemorrhage in humans would vary based on injury location and severity. However, the application time of either tourniquet in less than 2 minutes is likely fast enough to help most hemorrhage victims. The 19-s average difference between the color-coded and black tourniquet groups was likely due to the additional time participants spent reading the color-coded device. We suggest that this small time difference is unlikely to be clinically significant.

Quantifying reasons for failure will help future researchers and designers overcome these deficiencies. We found that applying the tourniquet too loosely was the single biggest reason for failed application.

This study represents a wide range of incomes, ages, ethnic backgrounds, education levels, and ethnic backgrounds. These demographic factors did not affect laypeople’s ability to successfully apply tourniquets. The use of 2 independent observers to assess successful tourniquet application yielded a high Kappa value (0.88).

Conclusions

Laypeople can successfully apply tourniquets using JiT instructions about half the time. Laypeople express a strong willingness to use tourniquets after brief exposure to the device. Demographic differences do not affect laypeople’s success. The median application time is likely fast enough to allow people to save lives during traumatic emergencies. Stop the Bleed aims to empower people to save lives from severe hemorrhage, and our results suggest that the general public can be successful in this endeavor. Going forward, further research to explore JiT educational techniques related to layperson hemorrhage control, such as short video self-instruction, and device optimization will help make Stop the Bleed truly scalable to the public at large.

Funding

This project was supported by the USU Office of Research and the Office of the Dean through the Capstone Student Research Program (USU Grant #M015282415).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the US Government.