Depression is one of the most common mental disorders diagnosed in adolescents and adults (Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, He, Burstein, Swanson, Avenevoli, Cui and Swendsen2010) and is considered to be the most prominent cause of disability worldwide (Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine and Vos2013). The lifetime prevalence of depression is almost at 12% in North American youth and young adults, with nearly 8% having severe impairment (Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, He, Burstein, Swanson, Avenevoli, Cui and Swendsen2010; Statistics Canada, 2017). Depression involves multiple physiological, behavioral, cognitive, and affective symptoms, including hopelessness, sadness, feelings of worthlessness, inability to experience pleasure, social withdrawal, and disordered sleep (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Understanding the etiology of depression in adolescence is important because it is debilitating and consistently predicts depression later in adulthood (Aalto-Setälä, Marttunen, Tuulio-Henriksson, Poikolainen, & Lönnqvist, Reference Aalto-Setälä, Marttunen, Tuulio-Henriksson, Poikolainen and Lönnqvist2002). Some researchers have affirmed that the development of depression must be understood in its social context (Coyne, Reference Coyne1976), specifically in light of adverse peer experiences (Kochel, Ladd, & Rudolph, Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012). Peer victimization (i.e., being the target of bullying) is of particular interest as it is reliably linked to depression and elevated symptoms of depression in youth (Krygsman & Vaillancourt, Reference Krygsman and Vaillancourt2017; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010; Sweeting, Young, West, & Der, Reference Sweeting, Young, West and Der2006), and it is a pervasive phenomenon in schools worldwide, with approximately 30% of youth being bullied by peers and 10% being victimized severely on a regular basis (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Trinh, McDougall, Duku, Cunningham, Cunningham and Short2010).

Regarding the longitudinal associations between depression and peer victimization, two predominant developmental pathways have been evidenced in the literature: the symptoms-driven model, whereby youth first become depressed and then become targets of bullying (Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012), and the interpersonal risk model, whereby bullied youth become depressed as a consequence of negative peer experiences (Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel, & Loeber, Reference Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel and Loeber2011). Although most research to date supports the interpersonal risk model (Arseneault et al., Reference Arseneault, Walsh, Trzesniewski, Newcombe, Caspi and Moffitt2006; McDougall & Vaillancourt, Reference McDougall and Vaillancourt2015; Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, Reference Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit and Bates2015; Ttofi et al., Reference Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel and Loeber2011), several recent studies have provided evidence for a symptoms-driven pathway (Kljakovic & Hunt, Reference Kljakovic and Hunt2016; Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012; Krygsman & Vaillancourt, Reference Krygsman and Vaillancourt2017; Schacter & Juvonen, Reference Schacter and Juvonen2017; Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, & Duku, Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku2013). There is also evidence for both pathways occurring simultaneously (Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010; Sweeting et al., Reference Sweeting, Young, West and Der2006), supporting a transactional model, whereby depression and peer victimization predict one another over time.

The development of depression should be understood not only within the interpersonal context (considering peer difficulties) but also in light of psychological traits and processes, specifically self-perceptions (Beck, Reference Beck1970; Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011). Many researchers have called for the investigation of third variables that may influence functioning across multiple domains of development (e.g., emotional regulation and peer relations; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku2013). The examination of constructs highly correlated to both depression and peer victimization could help further elucidate the mechanisms involved in their relation and directionality. Low self-esteem qualifies as such because it is consistently correlated with depression (Sowislo & Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013) and peer victimization (Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2016). Accordingly, it is reasonable to suppose that self-esteem, defined as the affective self-perception or evaluation of one's own worth (Orth, Robins, & Widaman, Reference Orth, Robins and Widaman2012), could influence the onset and overlapping developmental trajectories of depression and peer victimization.

There are two major competing models regarding the developmental relation between depression and low self-esteem: the scar model is characterized by depression scarring the individual's self-concept and leading to decreased self-esteem, while the vulnerability model is characterized by low self-esteem rendering the individual vulnerable to developing depression (Sowislo & Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013). Most research to date supports the vulnerability model, although there is evidence supporting reciprocity (Sowislo & Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013). For example, both pathways were found over a 30-year period: adolescent self-esteem predicted adult depressive symptoms (vulnerability model) and adolescent depression predicted adult self-esteem (scar model), with the vulnerability paths having stronger coefficients than the scar paths (Steiger, Fend, & Allemand, Reference Steiger, Fend and Allemand2015). These reciprocal transactions suggest that low self-esteem (poor self-related affect) may disrupt emotional regulation and psychosocial development as well as anchor depressive symptomology in the developing youth (vulnerability pathway), and that the continued experience of depressive mood may leave a lasting sense of self-deprecation (scar pathway). This could partly explain relapse and continuity of depression in youths and adults, as individuals could fall into a vicious cycle where depression leads to scarred self-perceptions, which in turn, lead to heightened depressive symptoms. Concerning the vulnerability model specifically, low self-esteem has been shown to exert its effect on depressive symptomology even after controlling for biological sex, race/ethnicity, age, pubertal development, social support, maternal depression, stressful events, relational victimization, and clinical versus nonclinical samples (Orth & Robins, Reference Orth and Robins2013; Orth, Robins, Widaman, & Conger, Reference Orth, Robins, Widaman and Conger2014). Moreover, variation at any level of self-esteem has been shown to predict a change in depressive symptomology (Orth, Robins, Meier, & Conger, Reference Orth, Robins, Meier and Conger2016). According to Beck (Reference Beck1970), negative views of the self and the environment precede and maintain depressive mood and are key to understanding the mechanisms responsible for the onset of depressive disorders (Heimpel, Wood, Marshall, & Brown, Reference Heimpel, Wood, Marshall and Brown2002; Tennen, Herzberger, & Nelson, Reference Tennen, Herzberger and Nelson1987). Similarly, researchers have suggested that poor self-esteem could also play a role in the development of peer victimization (Tetzner, Becker, & Baumert, Reference Tetzner, Becker and Baumert2016).

Self-esteem and peer victimization are negatively correlated, with longitudinal findings suggesting complex prospective associations (Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2016). Peer victimization is thought to erode self-esteem (Boulton, Smith, & Cowie, Reference Boulton, Smith and Cowie2010; McDougall & Vaillancourt, Reference McDougall and Vaillancourt2015) as targets of bullying may internalize social adversity and self-blame (Schacter & Juvonen, Reference Schacter and Juvonen2017; Tennen et al., Reference Tennen, Herzberger and Nelson1987). Low self-esteem may also increase the likelihood of being abused by peers via behavioral and emotional patterns (e.g., dejected mood, passivity; Heimpel et al., Reference Heimpel, Wood, Marshall and Brown2002) that communicate a sense of vulnerability (Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012; Salmivalli & Isaacs, Reference Salmivalli and Isaacs2005; Schwartz, Dodge, & Coie, Reference Schwartz, Dodge and Coie1993; Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2016). Both pathways support the idea that self-esteem and peer victimization likely influence one another over time and that their reciprocal prospective associations could be integrated in one comprehensive model that also includes symptoms of depression.

To the best of our knowledge, the temporal sequence of depression, peer victimization, and self-esteem has not been examined across adolescence in any published article, although similar investigations have been conducted. For instance, Egan and Perry (Reference Egan and Perry1998) found that self-perceived peer social competence (a self-reported measure of social abilities that is related to, yet distinct from, global self-esteem) moderated longitudinal associations between internalizing problems (composite measure including anxiety and depression) and peer victimization in a sample of children from Grades 3 to 7. It has been argued that specific self-esteem dimensions cannot be equated with global self-esteem (Rosenberg, Schooler, Schoenbach, & Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg, Schooler, Schoenbach and Rosenberg1995), and therefore, results using a specific dimension of self-concept or a composite measure should not be generalized to global self-esteem without investigation. Nonetheless, researchers have found that self-esteem mediates longitudinal associations between different types of victimization (e.g., child maltreatment; Ju & Lee, Reference Ju and Lee2018) and depression, providing evidence for the influence of self-esteem on the development of mental health disorders. These effects may be difficult to examine with traditional moderator/mediator analyses due to the complexity of the developmental pathways (e.g., reciprocal associations) involving multiple domains that share varying influences across the developmental periods of childhood and adolescence. The multidirectional nature of the transactions between depression, peer victimization, and self-esteem could be best described in a developmental cascade, that is, a system of complex, cumulative interactions and transactions within and across multiple domains of functioning (Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010). In light of prior research, it is reasonable to expect that self-esteem will participate in, or even initiate, a cascade leading to peer victimization or depressive symptoms.

The Current Study

In the present study, we systematically explored the temporal sequence of depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and self-esteem, and tested competing models (Objective 1); built an integrated cascade model that accounted for the joint development of depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and self-esteem (Objective 2); and tested indirect effects (i.e., mediating pathways; Objective 3).

To achieve Objective 1, we examined competing theoretical models using a cascade modeling procedure that took into account within-time associations, across-time stability, and cross-lagged effects. Because of the mixed evidence supporting the competing models tested herein, we allowed statistics to dictate the directionality of associations. We controlled for biological sex considering notable sex differences in the levels of depression (girls more depressed than boys; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), peer victimization (boys generally more victimized than girls; Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim, & Sadek, Reference Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim and Sadek2010), and self-esteem (girls having lower self-esteem than boys; Quatman & Watson, Reference Quatman and Watson2001). We also accounted for parental education and income because socioeconomic status is an important predictor of mental health problems (Reiss, Reference Reiss2013). Finally, ethnicity/race was controlled in view of higher depression scores found in some ethnic groups (Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Twenge and Nolen-Hoeksema2002).

To achieve Objective 2, we examined if the vulnerability and symptoms-driven pathways could be coherently combined into an integrated model that we described as self-perception driven, whereby low self-esteem prospectively predicted depressive symptoms that, in turn, predicted peer victimization. To achieve Objective 3, we tested the indirect effect of self-esteem on peer victimization via depressive symptoms, the key integrated pathway of our final model.

Method

Participants

A normative sample of 612 Canadian adolescents (54% girls) assessed annually over 5 years (Grade 7 to Grade 11) was drawn from the ongoing McMaster Teen Study, which examines the stability and change of mental health and social experiences from childhood to adolescence. Although data collection began when participants were in Grade 5, data for the present investigation were selected from Grade 7 based on the availability of the measures of interest (self-esteem was only measured from Grade 7). The initial sample of students was recruited from Grade 5 classrooms from 51 randomly selected schools within a large Southern Ontario Public School Board (in our analyses clustering was based on initial school). Parental consent and youth assent were obtained each year, as well as yearly university ethics board approval. Online questionnaires (with options of paper questionnaires) were completed by youth who were compensated with gift cards of incremental value, ranging from $10 (CAN) in Grade 7 to $35 (CAN) in Grade 11. Participants’ data were retained in our sample if they had scores for at least two time points, and our analytic sample was anchored in Grade 7. The mean age in Grade 7 was approximately 12 years and 5 months, and all participants transitioned to high school within the 5 years of data collection. The majority of youth (83.1%) indicated having a European Canadian (White) racial background, with the next two largest groups being African/West Indian Canadian (3.4%) and South Asian Canadian (2.7%).

Measures

Peer victimization

The experience of peer victimization was measured using a modified version of the Olweus Bully/Victim questionnaire that has optimized specificity and sensitivity (i.e., modified version more accurately identifies true cases of bullying and noninvolvement; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Trinh, McDougall, Duku, Cunningham, Cunningham and Short2010). Participants were first provided with a standard definition of bullying that included all three criteria (i.e., intentionality, repetition over time, and power imbalance) and were then asked: “How often have you been bullied at school in the past year (since September).” Four other questions were asked about specific types of bullying experiences (i.e. physical, verbal, social, and cyber), with answers ranging from not at all to many times per week. These items were summed to form a composite measure of peer victimization, that had good internal consistency (α range = 0.79–0.82).

Depressive symptoms

The depression subscale of the Behavior Assessment System for Children—2nd edition (Self-Report of Personality—Adolescent) was used to assess depressive symptoms. This inventory is widely used and has shown high correlations with other measures of depression symptomology (Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus2004). Four items were assessed with a 4-point scale (never, sometimes, often, and almost always; e.g., “I feel like my life is getting worse and worse”) while the other eight items were rated as true or false (e.g., “I just don't care anymore”). Items were summed to form a composite score of depressive symptoms. Internal consistency was excellent (α range = 0.87–0.91).

Self-esteem

A subscale of the Behavior Assessment System for Children—2nd edition was also used to evaluate self-esteem with a total of 8 items. Four items were rated as true or false (e.g., “I feel good about myself”) while four others were rated with a 4-point scale (never, sometimes, often, and almost always; e.g., “I am good at things”). Half of these items were reverse coded (e.g., “I wish I were someone else”). Items were then summed to form the subscale score that had excellent internal consistency (α range = 0.85–0.91).

Covariates

Socioeconomic status indicators were compiled during the parent phone interview portion of the study. Parent income was measured in Grade 5. Parent education was also assessed in Grade 5 with a question asking about the highest level of education attained (e.g., completed high school or university graduate degree). Ethnicity/race was self-reported by youth and verified by parents.

Analytic plan

Path analysis was performed with maximum likelihood robust (MLR) and full information maximum likelihood in Mplus Version 8 to account for deviation from normality (skew range: –1.82 to 2.67; kurtosis range: 0.61 to 11.48), and to handle missing values (Muthén & Asparouhov, Reference Muthén and Asparouhov2002; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). The CLUSTER command with TYPE=COMPLEX was used for each model to account for the clustering by initial school (51 clusters), ensuring that the initial distribution of participants did not influence findings. Following standard conventions (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; Kline, Reference Kline2011; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017), model fit was assessed with the chi-square test (significant results indicating poor fit); the comparative fit index (values above .95 indicating adequate fit; Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999); and the root mean square error of approximation (values below .06 indicating an excellent fit; Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Nested models were compared using the Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square difference test (required when using MLR; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017), while nonnested models were compared with the Akaike information criterion, with preference for models with lower values (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Indirect effects were tested on the final model using the MODEL INDIRECT command in Mplus with bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs; 95%; N = 5,000) and Bayes credibility intervals (95%; N = 20,000), accounting for typical nonnormality of mediation pathways. Specifically, Bayesian analyses produce posterior distributions and nonsymmetric intervals that do not assume normality, ensuring more accurate results than methods that rely on normally distributed estimates (Muthén, Muthén, & Asparouhov, Reference Muthén, Muthén and Asparouhov2016). Indirect effects were considered statistically significant if confidence and credibility intervals excluded zero, thus rejecting the null hypothesis.

Step-by-step model building was used to test developmental pathways and ascertain temporal priority by evaluating whether each set improved the overall model fit (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku2013). If an addition did not contribute to model fit, it was removed to favor parsimony (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Model 1 included only within-time associations (covariance) between the three constructs. One-year stability paths were added in Model 2 and 2-year stability paths in Model 3. One-year cross-lagged paths from depressive symptoms to peer victimization were added in Model 4a, while 1-year cross-lagged paths from peer victimization to depressive symptoms were added in Model 4b to test competing models with regard to the association between depression symptoms and peer victimization (symptoms-driven vs. interpersonal risk models). These cross-lagged pathways were combined in Model 4c to test the transactional model. Based on results, we built on Model 4a (symptoms-driven) by adding cross-lagged pathways from self-esteem to depressive symptoms (vulnerability model) for an integrated Model 5 (self-perception driven model; integrating associations between all three main variables). Subsequent models were built solely on Model 5, as it remained the best fitting model; in Model 6, cross-lagged paths from depressive symptomology to self-esteem were added (scar pathways); cross-lagged paths from self-esteem to peer victimization and from peer victimization to self-esteem were tested in Model 7 and Model 8, respectively; finally, biological sex, race/ethnicity, as well as parental education and income were inserted as controls in Model 9. Each covariate was regressed on all main variables at each time point. Nonsignificant paths were removed for parsimony, starting with the least significant, and the resulting model was compared to Model 5. Finally, Model 5 was modified with the addition of two specific significant cross-lagged paths that improved model fit, and with the deletion of two nonsignificant cross-lagged paths (based on modification indices) in order to obtain our final model. Indirect effects analyses were conducted on our final model (i.e., Modified Model 5).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Correlations of our main variables at each time point are reported in Table 1. All correlations between study variables were statistically significant (p < .01). All variables had values of skewness and kurtosis below recommended ranges for path analysis (i.e., under 3 for skewness and below 10 for kurtosis; Kline, Reference Kline2011), with the exception of peer victimization in Grade 11, which was considered kurtotic for the purposes of structural equation modeling (kurtosis of 11.5). Because missing data ranged from 11.1% to 11.8% in Grade 7 to 28.9% in Grade 11, with a yearly mean of 21.13%, we examined if our data were missing systematically or at random. Little's missing completely at random test, χ2 = 779.743 (600), p < .001, indicated that the data for our analytic sample were not missing completely at random, which is common for longitudinal studies (Ibrahim & Molenberghs, Reference Ibrahim and Molenberghs2009), especially as missing completely at random tests tend to fail when conditions for normality are not fully met (Jamshidian & Jalal, Reference Jamshidian and Jalal2010). We further investigated patterns of missing data with t tests, comparing mean differences of study variables for participants with and without data at each time point. Using a Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple testing (Benjamini & Hochberg, Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995), only one statistically significant difference was found. Participants without Grade 9 self-esteem data had higher Grade 7 peer victimization scores than those with Grade 9 self-esteem data (missing: N = 104, M = 2.21, SD = 2.47; present: N = 437, M = 3.08, SD = 3.38; excluding cases not having Grade 7 peer victimization scores). Given this only difference, we considered the data to be missing at random. MLR was also used with full information maximum likelihood in Mplus to account for missing values and nonnormality (Muthén & Asparouhov, Reference Muthén and Asparouhov2002; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Note: DEP, depressive symptoms. PV, peer victimization. SE, self-esteem. Gr, grade. All correlations are significant at p < .01; 2-tailed.

Developmental models

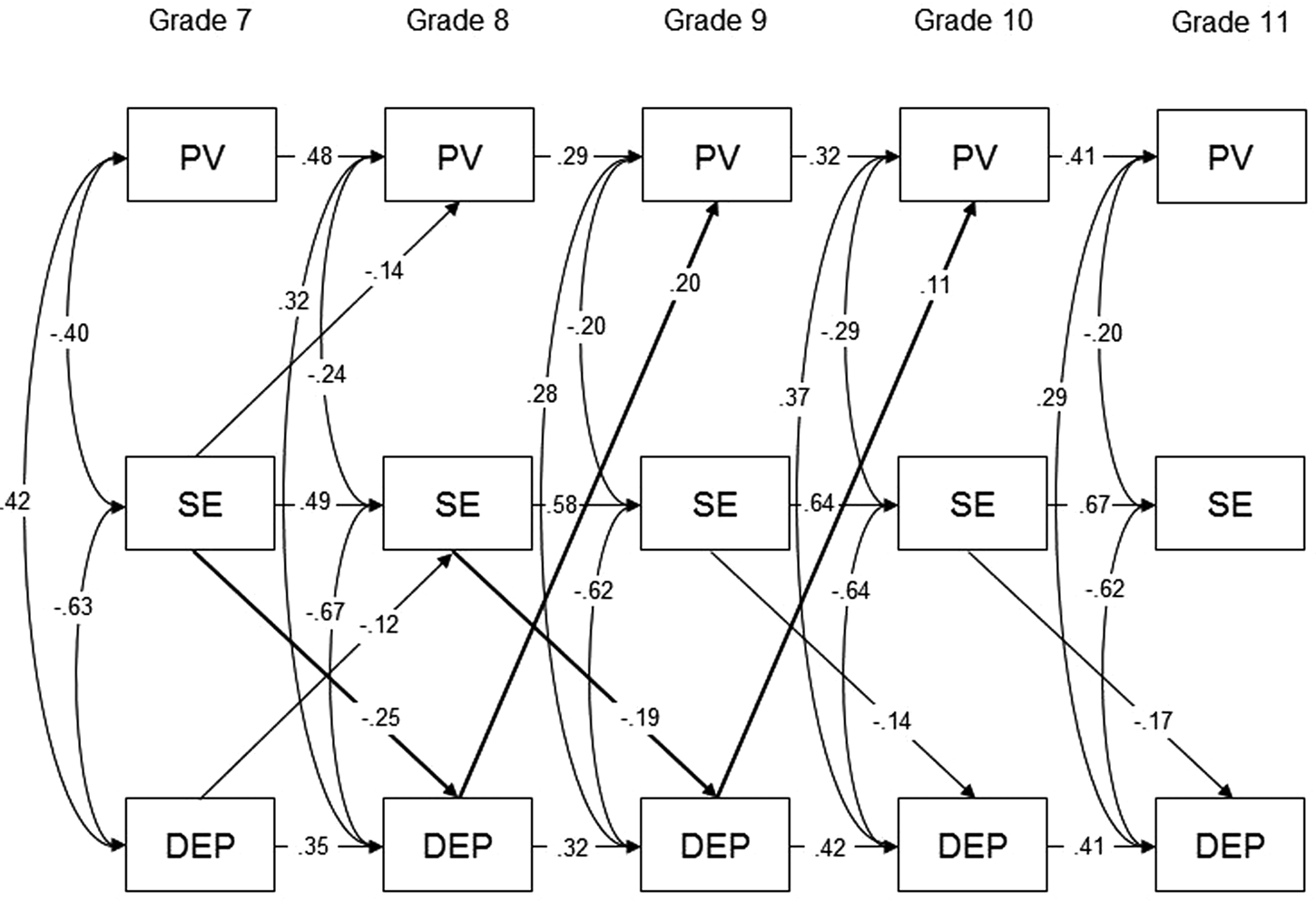

Model fit statistics are indicated in Table 2, and model fit comparison statistics are shown in Table 3. Model 1 (within-time covariance only) had poor fit as expected for the base model. Model 2 (with 1-year stability paths) also had poor fit but represented a significant improvement from Model 1. Model 3 (with 2-year stability paths) was a significant improvement in fit over Model 3. Model 4a (symptoms-driven pathways) and Model 4b (interpersonal risk model) had adequate fit according to comparative fit index and root mean square error of approximation values, but not according to chi-square test. Only Model 4a was superior to Model 3. We then tested the competing Models 4a and 4b (nonnested) and confirmed that the symptoms-driven model (Model 4a; depressive symptoms predicting peer victimization) was superior to the interpersonal risk model (Model 4b; peer victimization predicting depressive symptoms), specifically when controlling levels of self-esteem. Moreover, the transactional model (Model 4c) did not evidence significant improvement in model fit over the symptoms-driven model. Considering this finding, we discarded the interpersonal risk paths (peer victimization to future depressive symptoms) and continued to build on Model 4a. Model 5 (self-perception driven model: integrating vulnerability pathways [self-esteem to depressive symptoms] into the symptoms-driven model [depressive symptoms to peer victimization]) had excellent fit according to all indices and was superior in overall fit to Model 4a. Model 6 (depressive symptomology predicting self-esteem), Model 7 (self-esteem predicting peer victimization paths), Model 8 (peer victimization predicting self-esteem), and Model 9 (added controls) did not improve overall model fit compared to Model 5, and consequently, their respective added paths were discarded in favor of the more parsimonious model. Specifically, because covariates did not improve model fit, and because coefficients and significant pathways in compared models were very similar, the more parsimonious model (Model 5) was favored (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Finally, based on theory, modification indices, and paths significance, we modified Model 5 by retrieving two nonsignificant cross-lagged paths (Grade 7 depressive symptoms to Grade 8 peer victimization and Grade 10 depressive symptoms to Grade 11 peer victimization) and by adding two other specific cross-lagged paths (Grade 7 self-esteem to Grade 8 peer victimization and Grade 7 depressive symptomology to Grade 8 self-esteem). The modified Model 5 not only had excellent fit but also was superior to Model 5. Therefore, it was retained as our final model and is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2. Model fit statistics

Note: scf, scaling correction factor; CFI, comparative fit index. RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation. AIC, Akaike information criterion. Modified Model 5 was chosen as the final model. *p < .05. **p < .0001.

Table 3. Model comparison statistics

Note: Δχ2, Sattora–Bentler scaled chi-square difference. ΔAIC, difference in Akaike information criterion.

Figure 1. Self-perception driven cascade model of depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and self-esteem (Modified Model 5): characterized by the significant indirect effect of self-esteem on future peer victimization via depressive symptoms. Standardized coefficients (β) shown. Two-year stability paths omitted for ease of interpretation. PV = peer victimization; SE = self-esteem; DEP = depressive symptoms.

Indirect effects

Bootstrap CIs (N = 5,000; with 95% confidence) showed that Grade 7 self-esteem had a significant indirect effect on Grade 9 peer victimization via Grade 8 depressive symptoms (bootstrap = –.033, 95% CI [–.059, –.012]) and Grade 8 self-esteem had a significant indirect effect on Grade 10 peer victimization via Grade 9 depressive symptoms (bootstrap = –.014, 95% CI [–.034, –.001]), with lower self-esteem predicting increased depressive symptoms, which in turn, predicted increased peer victimization. These indirect effects were also confirmed with Bayesian credibility intervals (N = 20,000; with 95% credibility): Bayes = –.032, 95% credibility interval [–.055, –.015]; and Bayes = –.013, 95% credibility interval [–.028, –.003], respectively.

Discussion

We aimed to build an integrated cascade model that included depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and self-esteem over a 5-year period in order to examine temporal sequencing and test indirect effects (i.e., mediating pathways). Our findings supported the well-documented vulnerability model (lower self-esteem predicting higher depressive symptoms a year later, while controlling for concurrent peer victimization levels; Sowislo & Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013), and partially supported the scar model (depressive symptomology predicting lower self-esteem), lending some support for a cascade that includes reciprocal transactions. Beck's (Reference Beck1970) seminal work on depression outlined decades ago the maladaptive self-deprecations involved in mood disorders. Specifically, his cognitive triad states that individuals who are depressed hold pessimistic views of themselves (low self-esteem), of the world, and of the future. According to Beck, dejected mood is a consequence of depressogenic cognitive processes; cognitive distortions cause and maintain depressive symptoms. That is, the “way an individual structures his experiences [whether good or bad] determines his mood” (Beck, Reference Beck1970, p. 261). In line with this, researchers have shown that depressive (negative) attributional style, whereby depressed individuals tend to attribute adverse outcomes to internal causes (self-blame) and good outcomes to external causes (Seligman, Abramson, Semmel, & von Baeyer, Reference Seligman, Abramson, Semmel and von Baeyer1979), predicts future depression (Southall & Roberts, Reference Southall and Roberts2002; Tennen et al., Reference Tennen, Herzberger and Nelson1987). Not only can poor self-esteem account for negative attributional style (even more so than concurrent depressive symptoms), but researchers have shown that it can mediate the associations between negative attributional style and depression (Tennen et al., Reference Tennen, Herzberger and Nelson1987), suggesting that self-esteem (affective dimension of self-perception) is both maintaining depressogenic cognitions and attributional style and controlling their effect on internalizing symptoms. In addition, Heimpel et al. (Reference Heimpel, Wood, Marshall and Brown2002) reported that individuals with low self-esteem find negative mood more normal and acceptable; are more likely to not choose to improve their moods even when they know how to; and are even less likely to solve the negative outcome or problem that elicited their poor mood, making them vulnerable to chronic peer victimization experiences. These authors explained this with the self-verification possibility. That is, individuals with low self-esteem tend to not improve their mood as it validates their poor self-regard, while individuals with high self-esteem tend to improve their mood to corroborate their positive self-perceptions. Depressed individuals also display patterns of behavior (e.g., excessive reassurance seeking and mistrust of other's intentions) that can elicit negative responses (e.g., rejection or exclusion) from others that, in turn, confirm poor self-worth and enhance self-blame (Coyne, Reference Coyne1976; Krygsman & Vaillancourt, Reference Krygsman and Vaillancourt2017). These negative cognitive and interpersonal processes can explain how a vicious cycle is formed, where negative self-related affect (low self-esteem) leads to worsened mood and, in turn, poor mood leads to decreased self-esteem, thus establishing the temporal stability of depressive symptoms and poor self-esteem (Beck, Reference Beck1970; Heimpel et al., Reference Heimpel, Wood, Marshall and Brown2002; Sowislo & Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013). In contrast, individuals who maintain healthy self-esteem (e.g., by using self-protective attributions and social comparisons) would be able to avoid recurrent depressive symptoms (Heimpel et al., Reference Heimpel, Wood, Marshall and Brown2002; Tennen et al., Reference Tennen, Herzberger and Nelson1987).

Researchers have suggested that interventions that encourage healthy self-esteem may be effective in reducing depressive experiences of youth (Ju & Lee, Reference Ju and Lee2018; Sowislo & Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013). It is important to note that one of the core features of depression is feelings of worthlessness, which is also a key feature of low self-esteem (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2016). Although the literature demonstrates that self-esteem and depression share a substantial amount of variance, there is evidence to also suggest they are distinct: (a) their associations are not as strong as would be expected if they were the same construct; (b) self-esteem is more stable than depression over time, suggesting different underlying causal dynamics; (c) both constructs prospectively predict one another even after controlling for prior levels (e.g., in this investigation, self-esteem predicted future depressive symptoms at all time points, but the reverse prospective relation was only found once); and (d) self-esteem and depression have at least partially distinct genetic influences (Orth, Robins, & Roberts, Reference Orth, Robins and Roberts2008). The current investigation evidences different prospective associations from self-esteem to peer victimization than from depressive symptoms to peer victimization (suggesting distinct risk factors of peer victimization are measured). However, more research is needed to confirm if the behavioral patterns associated with low self-esteem that may place youth at risk for peer victimization are distinct from the affective patterns associated with depressive symptoms (i.e., dejected/negative mood, passivity, or feelings of worthlessness). Nonetheless, researchers have shown that decreased self-esteem constitutes a prodromal symptom for the onset of depression (Iacoviello, Alloy, Abramson, & Choi, Reference Iacoviello, Alloy, Abramson and Choi2010), and as such, could serve as an effective screening criterion for the identification of and early intervention with at-risk youth.

In the current study, we tested competing models with regard to the directionality of the associations between depressive symptoms and peer victimization, while controlling for self-esteem levels. Our results add to a growing body of literature supporting the symptoms-driven model (depressive symptoms leading to peer victimization; Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012; Schacter & Juvonen, Reference Schacter and Juvonen2017). Prospective symptoms-driven associations were described decades ago by Coyne (Reference Coyne1976), who showed that depressed individuals often induce negative responses from others due to their dejected mood and pessimistic attitudes that become a burden to others. Another explanation is that depressive symptoms communicate a sense of vulnerability to the peer group, making the depressed youth to be perceived as an easy target for bullying (Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012; Salmivalli & Isaacs, Reference Salmivalli and Isaacs2005; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Dodge and Coie1993; Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2016). Depression can also lead to lower social status (Agoston & Rudolph, Reference Agoston and Rudolph2013), a risk factor of peer victimization (Krygsman & Vaillancourt, Reference Krygsman and Vaillancourt2017).

Our results did not lend support to the interpersonal risk model (peer victimization leading to increased depression symptoms) nor to the transactional model (reciprocal associations across time) in adolescence. Sweeting et al. (Reference Sweeting, Young, West and Der2006) found both directions (transactional model) were present in a large longitudinal cohort study of youth aged 11–15, but that the relative associations from depression to peer victimization increased over time (especially for boys) relative to the associations from peer victimization to depression, suggesting a shift in the direction of the associations toward a symptoms-driven model during adolescence. Similarly, in Krygsman and Vaillancourt's (Reference Krygsman and Vaillancourt2017) study, symptoms-driven pathways only emerged in early adolescence (around age 13). In addition, Ttofi et al.’s (Reference Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel and Loeber2011) meta-analytic review found weaker effects in the interpersonal risk pathways (peer victimization leading to depression) when victimization occurred at an older age. It is likely that the longitudinal interpersonal risk pathways are stronger in childhood and shift to symptoms-driven pathways in adolescence as individuals’ psychosocial development unfolds. This is important to consider as the concurrent associations between internalizing symptomology (including depression) and peer victimization become stronger in adolescence compared to childhood (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim and Sadek2010), which highlights the need to intervene with both peer victimized and depressed youth who often find themselves spiraling into a vicious cycle of increasingly poor life outcomes (Hodges & Perry, Reference Hodges and Perry1999; Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010). For instance, in one longitudinal study, Vaillancourt and Haltigan (Reference Vaillancourt and Haltigan2018) found that 15.7% of adolescents were on a trajectory of increasing depression throughout middle and high school (Grade 7 to Grade 12). Similarly, Boivin, Petitclerc, Bei, and Barker (Reference Boivin, Petitclerc, Feng and Barker2010) found that 14.5% of children were on a high increasing or extreme decreasing trajectory of chronic peer victimization (Grade 3 to Grade 6). These types of trajectories likely overlap more often than by chance, as research shows that chronic or high peer victimization trajectories are associated with the greatest emotional distress (Biggs et al., Reference Biggs, Vernberg, Little, Dill, Fonagy and Twemlow2010; Goldbaum, Craig, Pepler, & Connolly, Reference Goldbaum, Craig, Pepler and Connolly2003). Inversely, decreasing peer victimization trajectories are associated with partial recovery with regard to poor affect (Biggs et al., Reference Biggs, Vernberg, Little, Dill, Fonagy and Twemlow2010). Because the effects of depression and peer victimization are often lasting (Aalto-Setälä et al., Reference Aalto-Setälä, Marttunen, Tuulio-Henriksson, Poikolainen and Lönnqvist2002; McDougall & Vaillancourt, Reference McDougall and Vaillancourt2015; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010), it is important that efforts are made to intervene with both victimized and depressed children and adolescents, even at the subclinical level (Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012), to orient them toward better life trajectories.

To conclude, our results support an integrated self-perception driven model characterized by the indirect effect of self-esteem on peer victimization via depressive symptoms. In our study, adolescents with poor self-regard were at higher risk of developing symptoms of depression, and subsequently to be victimized by their peers. These results evidence a true developmental cascade, where one developing domain affects other domains over time. What is of particular interest is that we found low self-esteem initiated a cascade that resulted in unfavorable outcomes (i.e., higher depressive symptoms and higher peer victimization). Researchers have found that poor self-esteem predicts mental and physical health difficulties, poorer economic prospects (Trzesniewski et al., Reference Trzesniewski, Donnellan, Moffitt, Robins, Poulton and Caspi2006), and multiple negative life events (Tetzner et al., Reference Tetzner, Becker and Baumert2016) during young adulthood. Such findings can be best explained by a developmental cascade initiated and maintained by self-perceptions. Furthermore, there is evidence that self-esteem is better modeled as a cause than a consequence of outcomes (e.g., affect, depression, and relationship satisfaction) across the life span (Orth et al., Reference Orth, Robins and Widaman2012). That is, self-esteem would precede unfortunate outcomes, more so than result from them.

Having negative self-regard is highly maladaptive (Beck, Reference Beck1970; Egan & Perry, Reference Egan and Perry1998; Heimpel et al., Reference Heimpel, Wood, Marshall and Brown2002; Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2016; Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011). Low self-esteem in adolescence even has long-term effects on adult mental health decades later (Steiger et al., Reference Steiger, Fend and Allemand2015), and can interact with other dimensions of cognitive processes to influence a wide array of psychosocial adjustment outcomes (Heimpel et al., Reference Heimpel, Wood, Marshall and Brown2002; Roberts & Monroe, Reference Roberts, Monroe, Joiner and Coyne1999; Southall & Roberts, Reference Southall and Roberts2002). Researchers have shown that adolescent self-esteem predicts poorer social constructs in adulthood (e.g., subjective social integration and support; Gruenenfelder-Steiger, Harris, & Fend, Reference Gruenenfelder-Steiger, Harris and Fend2016). Low self-esteem has also been shown to predict maladaptive emotional responses such as feeling more ashamed in the face of failure (Brown & Marshall, Reference Brown and Marshall2001). Individuals with low self-esteem may internalize failure more readily than individuals with healthy self-regard because they attribute negative outcomes to their concept of self (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Abramson, Semmel and von Baeyer1979). Moreover, low self-esteem per se (i.e., feeling devalued) is a notable chronic stressor (Schiller, Hammen, & Shahar, Reference Schiller, Hammen and Shahar2016). Thus, interventions aimed at enhancing self-regard could be considered an early form of mental difficulties prevention. An important implication for prevention is understanding how to identify the contextual features that can promote or detract from low self-esteem during development. Self-esteem is thought to develop depending on the approval and feedback from others and the evaluation of one's general sense of adequacy and desirability (Harter, Reference Harter and Kernis2006). Significant others (such as peers, parents, and teachers) play a major role in the development of healthy self-regard in childhood and adolescence. Negative social feedback and poor evaluation of one's adequacy would result in a negative valence toward the self and a lack of self-worth (low self-esteem; Harter, Reference Harter and Kernis2006). In addition, children who are not encouraged or confident to persevere would not likely perform as well as others in social, academic, and athletic contexts, and consequently might feel more devalued (low self-esteem) when comparing themselves to peers (social comparison), as well as being more likely to develop symptoms of depression. These vulnerable children may then be more rejected and bullied by their peers, and receive even more negative social feedback, reinforcing their low self-esteem. Poor self-perceptions could logically maintain such a deleterious developmental cascade throughout childhood and adolescence.

Limitations and future directions

The use of a cascade model is a key strength of the present study, as it constitutes the best design to assess mechanisms in the absence of a randomized control trial (Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010). However, an attempt at causality cannot be made, and future research should aim at replicating the current findings. Strong empirical support for temporal sequencing may be ascertained once the evidence from multiple investigations of similar pathways is accumulated. Furthermore, our results concerning the associations between self-esteem and depressive symptoms and between depressive symptoms and peer victimization are consistent with other studies assessing them separately (Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012; Sowislo & Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013), lending weight to the validity of their integration in our self-perception driven model.

As it is recommended to have no fewer than five cases per parameter to ensure that results of statistical analyses are trustworthy (Kline, Reference Kline2011), we controlled for biological sex as a covariate, due to our sample size and the high number of parameters in our model. Our lack of power was also confirmed using a Monte Carlo simulation, which indicated that at a reduced sample size for each sex, power estimates were insufficient to detect cross-lagged effects. To examine the moderating role of biological sex in our self-perception driven model, replication with larger samples and multigroup analyses is warranted, as notable sex differences exist in the respective measurement of depression, peer victimization, and self-esteem. Furthermore, using 1-year time lags resulted in having high-stability estimates that consumed a large proportion of variance and may have suppressed weaker cross-lagged effects. This could also explain why we did not find peer victimization to be predicting decreased self-esteem and heightened depressive symptoms at any time points in our analyses.

Assessing only peer victimization is also a limit in the present investigation as multiple forms of victimization (e.g., child maltreatment; Ju & Lee, Reference Ju and Lee2018) are linked to depression and elevated symptoms of depression. Other forms of victimization should be accounted for in future studies.

Because the present investigation used a normative/community sample and self-reported depressive symptoms, our self-perception driven model should also be replicated in clinical samples with diagnosed depression. However, as self-esteem has been found to negatively predict depression (vulnerability effect) in clinical samples as well (Orth & Robins, Reference Orth and Robins2013), and there is evidence suggesting that subclinical depression has the same prognosis as clinical depression (Angold, Costello, Farmer, Burns, & Erkanli, Reference Angold, Costello, Farmer, Burns and Erkanli1999; Rutter, Kim-Cohen, & Maughan, Reference Rutter, Kim-Cohen and Maughan2006), the current findings likely also apply in clinical contexts.

Another limitation of our study is that only self-reported measures were used, and results may be inflated by shared method variance. Specifically, depressed adolescents who tend to exhibit heightened sensitivity to social evaluation may be more likely to perceive that they are victimized by others (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku2013). Future investigations should focus on replicating our model with a multi-informant design (with different age groups, expecting potential shifts in directionality). Notwithstanding, the sole utilization of self-reports actually gives insight into the personal experiences of victimized and depressed youth. As Bronfenbrenner (Reference Bronfenbrenner1979) stated, “what matters for behavior and development is the environment as it is perceived rather than as it may exist in ‘objective’ reality” (p. 4). For the purposes of intervention, the reality that ultimately matters most is the perceived reality and personal experience of the child or adolescent (Krygsman & Vaillancourt, Reference Krygsman and Vaillancourt2017). Their affect corresponds to what is subjectively perceived, not necessarily to what is objectively factual (Beck, Reference Beck1970). Health care professionals should therefore help youth form a healthy identity and have a positive perspective on their experiences in order to avoid maladaptive attributions and cognitions that lead to internalizing symptomology and interpersonal difficulties.

Conclusion and clinical implications

The present study demonstrates that self-esteem can initiate and maintain developmental cascades that lead to poor life outcomes (e.g., depressive disorders and interpersonal problems). Our study highlights the importance of helping adolescents develop positive self-regard to promote mental health and good peer relations and the need to intervene with depressed and peer victimized youth to instill healthy self-perceptions. Interventions aimed at enhancing self-esteem and forming a healthy identity could break the vicious cycles of adverse outcomes that are driven by negative self-perceptions. In line with this, many modern approaches in psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011) target self-perceptions in their treatments of mental disorders (e.g., depression). Meta-analysis also suggest that improving self-esteem and self-concepts leads to concomitant improvement in behavioral and personality outcomes, and that interventions targeting self-perceptions (i.e., self-esteem and self-concepts) directly can be more efficient than programs that do not (Haney & Durlak, Reference Haney and Durlak1998). Self-esteem may even be instrumental in giving youth the confidence to seek help for their mental health difficulties (Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011). In sum, self-regard plays a central role in youth's well-being and should be considered an important component in the prevention and treatment of mental health and interpersonal difficulties.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heather Brittain and Dr. Amanda Krygsman for their help with this study.

Financial Support

This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Ontario Mental Health Foundation.