There is increasing evidence of the sensitivity of biological processes to a wide range of social experiences and contexts (Adam, Klimes-Dougan, & Gunnar, Reference Adam, Klimes-Dougan, Gunnar, Coch, Dawson and Fischer2007; Del Giudice, Ellis, & Shirtcliff, Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011; Sterling, Reference Sterling and Schulkin2004), and emerging research is discovering biological adaptation to various dimensions of culture (Busse, Yim, Campos, & Marshburn, Reference Busse, Yim, Campos and Marshburn2017; Causadias, Reference Causadias2013). In accordance with the theme of this Special Issue focused on cultural development and psychopathology (Causadias, Reference Causadias2013) and recent calls to integrate research on culture and biology (Causadias, Telzer, & Gonzales, Reference Causadias, Telzer and Gonzales2017), the current study examined associations between patterns of cultural adaptation (i.e., acculturation) and stress-sensitive neurobiological processes, specifically the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis among Mexican American youths who were born and raised in the United States by predominantly immigrant parents. The study aims broadly to examine whether culturally linked processes of adaptation “get under the skin” to shape and mold biological systems (Boyce & Ellis, Reference Boyce and Ellis2005; Del Giudice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011). In so doing, this research also seeks to answer two questions about adaptive calibration of stress responsivity that have long been of central interest in research on cultural adaptation: whether and how acculturation to US mainstream culture shapes adaptive functioning among racial/ethnic minorities, and whether bicultural individuals have an adaptive advantage compared to other acculturating individuals.

Cultural Adaptation and Stress Biology

Our longitudinal focus on cultural adaptation and stress biology rests on the premise that the acquisition of a cultural self is an essential developmental process (Causadias, Reference Causadias2013). All individuals are exposed to culturally linked institutions, social contexts, practices, values, and experiences across the life span (Adams & Markus, Reference Adams, Markus, Schaller and Crandall2004) that progressively shape the way they think about their world, social roles and relationships, and life goals (Causadias, Reference Causadias2013). In this way, models of the cultural self and others begin to form early in life to shape and organize experiences, the individual's social, linguistic, cognitive, and behavioral patterns, and later developmental outcomes, including patterns of adaptation and maladaptation. The current study examines HPA functioning as one aspect of individual adaptation to cultural context.

Although the embedding of culture in development is a relevant process for all individuals (Causadias, Vitriol, & Atkin, Reference Causadias, Vitriol and Atkin2018), there are important ways in which cultural development poses unique challenges for individuals who are members of racial/ethnic minority groups and migrant communities that are culturally distinct from the dominant White majority population in the United States. For racial/ethnic minorities, cultural development often involves experiences of marginalization and discrimination (Pascoe & Smart Richman, Reference Pascoe and Smart Richman2009) and a heightened need to reconcile differing cultural norms and expectations, as well as the potential social and psychological costs and benefits associated with one's integration within the dominant and heritage cultures (Gonzales, Jensen, Montano, & Wynne, Reference Gonzales, Jensen, Montano, Wynne, Caldera and Lindsey2015; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Des Rosiers, Huang, Zamboanga, Unger, Knight and Szapocznik2013). The terms acculturation (i.e., “Anglo” cultural orientation) and enculturation (i.e., “Mexican” cultural orientation) describe dual aspects of cultural adaptation for Mexican Americans in the United States (Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, Reference Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz and Sirolli2002; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Gonzales, Saenz, Bonds, German, Deardorff and Updegraff2010).

The process by which minorities adapt as they navigate from one cultural context to another has long been thought to have implications for physical and mental health (Rogler, Cortes, & Malgady, Reference Rogler, Cortes and Malgady1991; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, Reference Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga and Szapocznik2010), and more recently for physiological processes implicated in health (Mangold, Mintz, Javors, & Marino, Reference Mangold, Mintz, Javors and Marino2012; Nicholson, Miller, Schwertz, & Sorokin, Reference Nicholson, Miller, Schwertz and Sorokin2013; Steffen, Smith, Larson, & Butler, Reference Steffen, Smith, Larson and Butler2006). The HPA axis is one biological system that may be affected by the experience of cultural adaptation (i.e., acculturation) because the HPA axis is sensitive to environmental challenges and responds by releasing cortisol. The stress hormone cortisol's main physiological function is to mobilize biological and psychological resources to prepare the body to respond to cues of threat or opportunities in the environment by increasing alertness, vigilance, and energy, and by sensitizing memory (Roozendaal, Reference Roozendaal2000). In comparison with more immediate physiological stress indicators (e.g., the autonomic nervous system), cortisol's response profile is relatively delayed, with a peak typically observed between 10 and 30 min poststressor and effects that persist anywhere from an hour to several hours and days after an HPA stress response (Del Giudice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011). This means that cortisol typically elevates only to the most salient environmental cues that cannot be mitigated through more immediate low-threshold stress pathways, or comprise environmental cues that are particularly meaningful for the HPA axis. For example, the HPA axis is sensitive to social evaluative threat (Dickerson & Kemeny, Reference Dickerson and Kemeny2004) because it provides important feedback about the presence (or absence) of social opportunities and challenges, status and support (de Weerth, Zijlmans, Mack, & Beijers, Reference de Weerth, Zijlmans, Mack and Beijers2013; Phan et al., Reference Phan, Schneider, Peres, Miocevic, Meyer and Shirtcliff2017). Such feedback is acutely relevant for youths who must navigate social interactions across contexts (i.e., home, school, and community) on a daily basis. Thus, high or rising cortisol levels in response to socially evaluative contexts may be adaptive by allowing the individual to be open and physiologically responsive to social information (Shirtcliff, Peres, Dismukes, Lee, & Phan, Reference Shirtcliff, Peres, Dismukes, Lee and Phan2014). For acculturating youth, physiological responsivity might facilitate attention and processing of subtle social cues as well as development of social and cognitive competencies needed to interact across cultural contexts and in different languages (Hong, Morris, Chiu, & Benet-Martinez, Reference Hong, Morris, Chiu and Benet-Martinez2000; Tadmor, Tetlock, & Peng, Reference Tadmor, Tetlock and Peng2009). However, while cortisol reactivity in response to stress may be adaptive, there are trade-offs such that low or blunted reactivity may allow the individual to be physiologically shielded from social evaluative threat and less able to encode or amplify negative social experiences (Del Giudice, Ellis, & Shirtcliff, Reference Del Giudice, Ellis, Shirtcliff, Laviola and Macri2013; Ellis, Del Giudice, & Shirtcliff, Reference Ellis, Del Giudice, Shirtcliff, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2012). Thus, the extent to which increased acculturation may also expose individuals to acculturative stressors that chronically impact the HPA axis must be interpreted as a physiological trade-off between the benefits of being open to salient social information and harnessing such arousal to cope with the social context and the costs of amplifying cues of social judgment and evaluative feedback.

To our knowledge, prior studies of culture and HPA functioning have not modeled patterns of stress responsivity and recovery in relation to acculturation, nor have they considered cultural processes that potentially enhance capacity to adapt to social opportunities and challenges (Doane, Sladek, & Adam, Reference Doane, Sladek, Adam, Causadias, Telzer and Gonzales2018). However, an emerging literature has started to document acculturation-linked variations in other stress-relevant biological systems (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Smith, Larson and Butler2006). In a study of Mexican immigrant farmworker families in Oregon, cumulative experiences in the United States (i.e., years living in the United States, adapting to mainstream culture) were associated with indicators of allostatic load that suggest dysregulation across multiple stress-response system measures such as blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, and immune function (McClure et al., Reference McClure, Josh Snodgrass, Martinez, Squires, Jimenez, Isiordia and Small2015). Whereas allostatic load provides a comprehensive index of the “wear and tear” across stress biomarkers (McEwen, Reference McEwen1998) within young populations, a subset of primary allostatic mediators are often examined as developmental precursors to allostatic load (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, Ouellet-Morin, Hupbach, Tu, Buss, Walker, McEwen, Cicchetti and Cohen2006); arguably, the most common primary allostatic mediator that indicates the first straws of allostatic load (Bush, Obradovic, Adler, & Boyce, Reference Bush, Obradovic, Adler and Boyce2011) is HPA functioning as measured by cortisol. For example, in 2011, Development and Psychopathology published a two-part Special Issue on developmental studies on allostatic load (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2011) in which 7 out of the 18 empirical studies used cortisol as the sole allostatic load measure (Badanes, Watamura, & Hankin, Reference Badanes, Watamura and Hankin2011; Blair et al., Reference Blair, Raver, Granger, Mills-Koonce and Hibel2011; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Obradovic, Adler and Boyce2011; Cicchetti, Rogosch, Toth, & Sturge-Apple, Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch, Toth and Sturge-Apple2011; Davies, Sturge-Apple, & Cicchetti, Reference Davies, Sturge-Apple and Cicchetti2011; Essex et al., Reference Essex, Shirtcliff, Burk, Ruttle, Klein, Slattery and Armstrong2011; Skinner, Shirtcliff, Haggerty, Coe, & Catalano, Reference Skinner, Shirtcliff, Haggerty, Coe and Catalano2011) and several other studies included cortisol as a primary target measure of allostatic load (e.g., Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Shirtcliff, Klimes-Dougan, Allison, Derose, Kendziora and Zahn-Waxler2011; Johnson, Bruce, Tarullo, & Gunnar, Reference Johnson, Bruce, Tarullo and Gunnar2011). The few available studies specifically linking cortisol with acculturation among Latinos have focused on diurnal cortisol patterns and have generally supported this link, but findings have been mixed. A study of pregnant Latinas reported that high levels of acculturation predicted increased total cortisol levels (Ruiz, Pickler, Marti, & Jallo, Reference Ruiz, Pickler, Marti and Jallo2013); however, another study of pregnant Mexican American women and their infants found patterns of blunted maternal cortisol (flatter diurnal slopes) during the prenatal and postpartum period that mediated associations between acculturation and adverse infant outcomes (D'Anna-Hernandez et al., Reference D'Anna-Hernandez, Hoffman, Zerbe, Coussons-Read, Ross and Laudenslager2012). A study of Latino men found increased time in the United States was associated with blunted total cortisol output (Squires et al., Reference Squires, McClure, Martinez, Eddy, Jimenez, Isiordia and Snodgrass2012), and a study of young children of Latino immigrant parents found an interaction between economic hardship and acculturation in the prediction of total diurnal cortisol, with lower cortisol output found except when children were protected by low acculturation and low economic hardship (Mendoza, Dmitrieva, Perreira, Hurwich-Reiss, & Watamura, Reference Mendoza, Dmitrieva, Perreira, Hurwich-Reiss and Watamura2017). Studies also report linkages between acculturation and the cortisol awakening response, a biological marker of HPA activity that indicates the flexibility or elasticity of the HPA axis to elevate when appropriate and provides a physiological “jumpstart” for the day (Clow, Hucklebridge, Stalder, Evans, & Thorn, Reference Clow, Hucklebridge, Stalder, Evans and Thorn2010; Fries, Dettenborn, & Kirschbaum, Reference Fries, Dettenborn and Kirschbaum2009). Among Mexican American men, high levels of adherence to the Anglo or mainstream culture, measured by self-reported comfort with the English language and with English-language music, books, and television, as well as with English-speaking European American friends, were associated with a decrease in the cortisol awakening response (Mangold et al., Reference Mangold, Mintz, Javors and Marino2012; Mangold, Wand, Javors, & Mintz, Reference Mangold, Wand, Javors and Mintz2010). This may indicate that the stress and challenge of acculturation may be overwhelming and fatiguing, blunting the cortisol awakening response and altering the HPA axis from a system of increased responsivity to one with a more diminished response (Heim, Ehlert, & Hellhammer, Reference Heim, Ehlert and Hellhammer2000). Among a small sample of adult Latinas, Torres, Mata-Greve, & Harkins (Reference Torres, Mata-Greve and Harkins2018) also found increased levels of acculturative stress were associated with a blunted cortisol awakening response and a flatter diurnal cortisol pattern.

As a whole, these findings suggest that acculturation may calibrate HPA response systems in ways that compromise the health of acculturating Latino immigrants and their children who must adapt and live effectively in relation to two or more cultural groups. However, the empirical literature regarding the nature of cortisol dysregulation in relation to cultural variables among US Latinos is characterized by discrepancies, some of which may stem from methodological differences. A meta-analysis synthesizing the more abundant literature on the association between experiences of racial discrimination and cortisol output (k = 16 studies, N = 1,506 participants) indicated a very small association across studies, with varying effects sizes as a function of research design and the cortisol measure being examined (Kouros, Causadias, & Casper, Reference Korous, Causadias and Casper2017). In general and in contrast to studies of diurnal cortisol, most experimental studies found more pronounced cortisol reactivity in response to racial discrimination. The authors acknowledge that neither method (naturally occurring diurnal cortisol vs. experimentally induced reactivity) captures the effect of racial discrimination and cortisol output more sufficiently, but rather, the two methodologies address the question from different perspectives that each offer valuable insights. From this perspective, the current study offers an important extension of current research by examining acculturation in relation to cortisol reactivity, and by testing whether cultural adaptation is linked to heightened cortisol reactivity or to a pattern of blunted cortisol response suggested by the majority of studies (albeit few in number) linking acculturation with diurnal cortisol output.

The current study also advances current research by considering dual axes of cultural adaptation (i.e., bidimensional assessment of acculturation and enculturation) for the first time in research on stress biology. One question not yet addressed by prior research is whether acculturation–stress biology associations are due primarily to adoption and exposure to dominant cultural ways and related stress processes (i.e., acculturative stress), as typically surmised, or whether they might be explained, instead, by the loss of protective elements of one's heritage culture as individuals becomes more acculturated. Peek et al. (Reference Peek, Cutchin, Salinas, Sheffield, Eschbach, Stowe and Goodwin2010), found that US-born individuals of Mexican descent had higher allostatic load scores than their counterparts who had been born in Mexico, but this was not accounted for by English language use, social integration, or cultural assimilation, raising the possibility that other aspects of cultural adaptation (i.e., loss of heritage culture) may explain these differences. Neither has this research accounted for the possibility that acculturating individuals may integrate and function well in American society while also retaining their cultural roots and their ethnic language (e.g., Lopez & Contreras, Reference Lopez and Contreras2005), a pattern known as integration (Berry, Reference Berry1997) or biculturalism (e.g., LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, Reference LaFromboise, Coleman and Gerton1993). Accumulating findings on social and psychological outcomes show that biculturalism may be the most adaptive strategy in multicultural societies (Berry, Reference Berry1989; Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin, & Szapocznik, Reference Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin and Szapocznik2005; Nguyen & Benet-Martinez, Reference Nguyen and Benet-Martinez2013; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Schwartz, Prado, Huang, Pantin and Szapocznik2007). However, this hypothesis has never been tested in studies of stress biology because these studies have not utilized bidimensional frameworks to assess patterns of cultural adaptation.

Bidimensional Model of Cultural Adaptation and the Advantages of Biculturalism

Influenced by the work of Berry (Reference Berry and Padilla1980, Reference Berry1997), the bidimensional model of acculturation is based on the premise that acculturating individuals must negotiate two central issues: the extent to which they will identify and participate in the mainstream or dominant culture; and the extent to which they will retain identification and involvement with their culture of origin, or ethnic culture. The negotiation of these two issues broadly allows for four adaptation patterns depending on the opportunities, inclinations, and abilities of the individual: assimilation (involvement and identification with the dominant culture only), integration (involvement and identification with both cultures, that is, biculturalism), separation (involvement and identification with the ethnic culture only), or marginalization (lack of involvement and identification with either) (Schwartz & Zamboanga, Reference Schwartz and Zamboanga2008). It should be noted, however, that studies have not found empirical support for marginalization (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, Reference Berry, Phinney, Sam and Vedder2006; Coatsworth et al., Reference Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin and Szapocznik2005; Schwartz & Zamboanga, Reference Schwartz and Zamboanga2008).

In contrast to unidimensional assessment of acculturation, bidimensional assessment allows that individuals may strongly endorse values and behavioral practices from both the receiving and heritage cultural contexts (Benet-Martinez & Haritatos, Reference Benet-Martinez and Haritatos2005; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodriguez, & Wang, Reference Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodriguez and Wang2007; Tadmor & Tetlock, Reference Tadmor and Tetlock2006). Thus, these individuals maintain some degree of continuity with their culture of origin yet also participate as an integral part of the dominant or host society (Dona & Berry, Reference Dona and Berry1994), which may offer at least three adaptive advantages of flexibility and a wider range of context-specific behavioral responses. First, bicultural individuals are able to interact with people from the larger society and from the heritage community, affording access to more instrumental and emotional sources of support (Chen, Benet-Martinez, & Harris Bond, Reference Chen, Benet-Martinez and Harris Bond2008). Second, they are able to use coping strategies and coping resources from both cultures (LaFromboise et al., Reference LaFromboise, Coleman and Gerton1993). For example, facility with English and dominant cultural ways can offer greater access to educational opportunities, networking, and behavioral repertories that are critical for the integration of immigrants into American schools and society (Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, Reference Phinney, Romero, Nava and Huang2001). In contrast, proficiency in one's maternal language and a strong sense of cultural solidarity reminds individuals about their heritage cultural strengths and values that can serve as a coping resource as adolescence expand their social worlds and encounters with new social contexts and challenges (Portes & Schauffler, Reference Portes and Schauffler1994). Third, the competencies and flexibility (social and cognitive) that bicultural individuals acquire in the process of learning and using two cultures may enhance executive functioning (Bialystok & Craik, Reference Bialystok and Craik2010) and make bicultural youth more adept at adjusting to a wider range of people in either of their cultures and possibly in other cultures (Benet-Martinez, Lee, & Leu, Reference Benet-Martinez, Lee and Leu2006; Gonzales, Knight, Birman, & Sirolli, Reference Gonzales, Knight, Birman, Sirolli, Maton, Schellenbach, Leadbeater and Solarz2004; Leung, Maddux, Galinsky, & Chiu, Reference Leung, Maddux, Galinsky and Chiu2008). Research informed by this perspective has generated a body of evidence to support the position that biculturalism is the most adaptive pattern in pluralistic societies. In a meta-analysis of 83 studies (N = 23,197 participants), Nguyen and Benet-Martínez (Reference Nguyen and Benet-Martinez2013) reported a strong and positive association between biculturalism and adjustment that was stronger than the association between having a strong orientation toward only one culture (dominant or heritage) and adjustment. Results based on the random-effects approach found a significant, strong, and positive association between biculturalism (high orientation to both dominant and heritage cultures) and adjustment that was significantly stronger when biculturalism was measured bilinearly (separate assessments for each dimension), for the psychological and sociocultural adjustment domains, for individuals living in the United States, and for people of Latin, Asian, and European descent (vs. unilinear or typological acculturation scales, health-related adjustment, participants living outside the United States, and African and Indigenous samples, respectively).

Along with the unique benefits of biculturalism, it is possible that being strongly oriented only to the dominant culture (i.e., assimilation) has additional costs resulting from the loss of shared values and positive ethnic identity that have been shown to buffer experiences of ethnic and racial discrimination when interacting within the dominant culture (Bondolo, Brady ver Halen, Pencille, Beatty, & Contrada, Reference Bondolo, Brady ver Halen, Pencille, Beatty and Contrada2009; Umaña-Taylor et al., Reference Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, Lee, Cross, Rivas-Drake and Schwartz2014). One of the defining Latino cultural values is familismo (familism), which involves strong identification with and attachment to immediate and extended family and feelings of loyalty, reciprocation, and solidarity among family members (Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, & Perez-Stable, Reference Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal and Perez-Stable1987). Familism may facilitate adaptation in a variety of ways, such as by increasing the amount of social support available from family members, deterring deviant behaviors that could bring shame to the family, providing youth with a strong sense of purpose or meaning, and promoting healthy family interactions (Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Jensen, Montano, Wynne, Caldera and Lindsey2015; Telzer, Tsai, Gonzales, & Fuligni, Reference Telzer, Tsai, Gonzales and Fuligni2015). When acculturation results in the loss of connection to core familism values, youth may lose this central motivating framework and source of support for coping with challenges they face outside the family (Germán, Gonzales, & Dumka, Reference Germán, Gonzales and Dumka2009). Among second-generation US Latinos, adoption of the dominant culture at the expense of one's ethnic culture may also lead youths to ascribe to mainstream “American” values organized around individuality that may clash with the traditional family-centered values of their parents and give rise to parent–child conflict (Gonzales, Deardorff, Formoso, Barr, & Barrera, Reference Gonzales, Deardorff, Formoso, Barr and Barrera2006; Szapocznik & Coatsworth, Reference Szapocznik, Coatsworth, Glantz and Hartel1999). Marital conflicts may be exacerbated as well, owing to shifting cultural values within and between parents (Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Deardorff, Formoso, Barr and Barrera2006; Parke et al., Reference Parke, Coltrane, Duffy, Buriel, Dennis, Powers and Widaman2004). It is possible these family disruptions also account for alterations in stress physiology for acculturating youth as the protective effects of family and community are diminished and potentially replaced by social evaluative threat, judgment, and family conflict (Doom, Doyle, & Gunnar, Reference Doom, Doyle and Gunnar2017; Doom, Hostinar, VanZomeren-Dohm, & Gunnar, Reference Doom, Hostinar, VanZomeren-Dohm and Gunnar2015; Hostinar, Johnson, & Gunnar, Reference Hostinar, Johnson and Gunnar2015).

By assessing heritage (i.e., Mexican) cultural orientation and dominant (i.e., Anglo) cultural orientation as separate dimensions in the current study, we were able to examine their unique associations with the youths’ HPA axis stress response. We also capitalized on this bidimensional approach to examine their interactive effects (i.e., the product of Mexican and Anglo orientation) and test our hypothesis that acculturated youths who have greater ability to operate effectively within both worlds (i.e., bicultural) will show a more adaptive stress response. In addition, we examined whether family conflict and youth familism values accounted for culture–biology associations in our Mexican American adolescent sample.

The Present Study

We examined patterns of association between adolescents’ cultural orientation and stress reactivity using an ongoing longitudinal birth cohort study of Mexican American families in California called the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS). CHAMACOS means “kids” in Mexican Spanish and reflects the study's focus on youth in a predominantly Mexican-origin migrant farmworker community that have been assessed every 1 to 2 years since birth. This study focused on assessments at ages 12 and 14 years to examine whether Mexican and Anglo cultural orientations of youth at age 12, and their interaction, predict cortisol response to stress at age 14.

Our focus on the early to middle adolescent transition offered an important window to examine cultural orientation and stress responsivity at a time when developing youths are acutely attuned to their social worlds and experiences of social evaluative threat (Juvonen, Graham, & Schuster, Reference Juvonen, Graham and Schuster2003), and when cultural orientation has shifted from being primarily parent driven to more self-determined (Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, Reference Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen and Guimond2009). The prospective design and developmental timing of the study are further relevant to the premise that an individuals’ emerging cultural self serves to organize and predict later aspects of development (Causadias, Reference Causadias2013). Prior studies support a sensitive window for cultural acquisition, with younger children being especially receptive, particularly in the language domain (Cheung, Chudek, & Heine, Reference Cheung, Chudek and Heine2011). Emerging English and Spanish language abilities are critical markers of cultural adaptation because language originates and is transmitted through ethnic and mainstream participation (Giles, Bourhis, & Taylor, Reference Giles, Bourhis and Taylor1977) and subsequently serves to condition access to future community participation (Causadias, Reference Causadias2013), including the formation of peer networks that provide a primary source for cultural continuity and change in adolescence. Prior research has shown that, by the time second-generation youths enter adolescence, they exhibit distinct patterns of linguistic cultural adaptation that remain relatively stable thereafter (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Vargas-Chanes, Losoya, Cota-Robles, Chassin and Lee2009; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Des Rosiers, Huang, Zamboanga, Unger, Knight and Szapocznik2013). Although other aspects of cultural adaptation, such as ethnic identity and cultural values, show more pronounced changes over time (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Vargas-Chanes, Losoya, Cota-Robles, Chassin and Lee2009; Padilla, McHale, Rovine, Updegraff, & Umaña-Taylor, Reference Padilla, McHale, Rovine, Updegraff and Umaña-Taylor2016; also Gonzales, et al., in this issue), most youths achieve stability by early to middle adolescence on the aspects of cultural adaptation (language and affiliation patterns) used to assess Mexican and Anglo orientation in the current study.

We examined 2-year prospective effects of Mexican and Anglo cultural orientation (main effects and their interaction) on cortisol reactivity and recovery (Model 1), and follow-up mediation analyses to examine whether family conflict (Model 2) or youth familism values (Model 3) explained variations in cortisol reactivity and recovery associated with Mexican and Anglo cultural orientation. Three hypotheses were tested. First, we hypothesized that bicultural adaptation (high on both Anglo and Mexican cultural orientation) would be associated with a more adaptive stress response, and those high on Anglo orientation but low on Mexican orientation (assimilation pattern) would evidence compromised stress-response patterns compared to their peers. Second, we hypothesized that a compromised stress response for those high on acculturation (assimilation) would be partially explained by heightened levels of family conflict. Third, we hypothesized that a compromised stress response for those high on acculturation (assimilation) would be partially explained by reduced levels of familism values among these youths. The effects of sex and family income-to-poverty ratio were tested as potential covariates because previous research has shown sex effects for cortisol reactivity and individuals of higher socioeconomic status could have more adaptive cortisol responses as well as more opportunities to be bicultural (Moyerman & Forman, Reference Moyerman and Forman1992).

Method

Participants

The CHAMACOS parent study includes two cohorts of children: a birth cohort of children born to women who were enrolled during pregnancy, and a second cohort of same-age children enrolled at 9 of age years. The current study focuses specifically on the original birth cohort of families who were recruited during pregnancy to investigate the effects of pesticides and other environmental exposures on child development and health. Pregnant women were eligible if they were (a) 18 years of age or older and less than 20 weeks gestation; (b) Spanish- or English-speaking; (c) eligible for California's low-income health insurance program (Medi-Cal); (d) receiving prenatal care; and (e) planning to deliver at the county hospital. Detailed methods of the CHAMACOS cohort have been published (e.g., Eskenazi et al., Reference Eskenazi, Huen, Marks, Harley, Bradman, Barr and Holland2010). In brief, 1,800 pregnant women were screened for eligibility between October 1999 and 2000 at six prenatal clinics serving primarily farmworker families. Of the 1,130 eligible women, 601 women initially enrolled, and 531 were followed through delivery of 536 liveborn children (including 5 sets of twins); of these 536 children, 324 remained active in the study at child age 14 years (i.e., they attended a visit and completed a youth questionnaire). Overall, we maintained contact with 61% of the original birth cohort youth with most attrition occurring between birth and 6 months. Retention for birth cohort since age 5 years has averaged 95% between visits. This represents notably strong retention given the low-income, highly mobile nature of this largely farmworker sample.

Participants are Mexican-origin families living in the largely agricultural Salinas Valley community in Monterey County, California. The majority of mothers in this sample were born in Mexico (85%), with the remainder born in the United States, over half were recent immigrants (in the US <5 years) at the time of pregnancy, and 96% fell below 200% of the poverty line. The children who participated at age 14 (54% female) were assessed every 6 months to 2 years since they were in utero. The current study focuses on the 264 youths (81% of the original birth cohort participants who participated at 14 years) who completed the Trier Social Stress Test and provided saliva samples (procedure described below) as part of the 14-year-old wave of data collection. These youths (52% females; mean age = 14.19 years, SD = 0.29) also completed measures of cultural orientation (12-year wave), family conflict (14-year wave), and familism (14-year wave).

Procedures

At ages 12 and 14, youths and their caregivers (predominantly mothers) attended visits at the CHAMACOS field office. At age 12, this visit included an interview with the mother and child, biospecimen sample collection, anthropometry, and a brief neurodevelopmental assessment. At age 14, youth also participated in the Trier Social Stress Test and provided saliva samples (described below) to assess cortisol levels. Bilingual, bicultural research assistants administered questionnaires and conducted measurements and collected samples. Prior to data collection, consent and assent forms were read aloud to parents and their children, respectively, and consent/assent was obtained. Visits at 12 years old lasted approximately 2.5 hr for both parents and children. At 14 years old, visits were approximately 3.5 hr for parents and youth. Participants were compensated $100 (mothers) and $20 (youth) at the 12-year visit and $100 (mothers) and $75 (youth) at the 14-year visit. Interviews with youth at age 12 years and 14 years were administered using Computer-Assisted Personalized Interviewing procedures in order to ensure youths’ confidentiality when responding to sensitive subjects.

During the 14-year wave of data collection, participants began the study protocol between 12:30 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. to control for diurnal variability of resting cortisol. Participants were asked to swish with water upon arriving to the office, and then sit down to rest for at least 10 min to acclimate to the environment. Participants completed noninvasive questionnaires during this time (i.e., contact forms) and watched a 3-min peaceful video of sea life. After youth had rested for at least 10 min, they were asked to deposit 1 mL of saliva into a cryovial via passive drool through a straw, following established procedures (Sample 1; Schwartz, Granger, Susman, Gunnar, & Laird, Reference Schwartz, Granger, Susman, Gunnar and Laird1998). Next, participants engaged in the modified Trier Social Stress Test (discussed below). Saliva samples were taken again immediately after the Trier Social Stress Test was completed (Sample 2), and again at 15 min (Sample 3) and 30 min after the completion of the Trier Social Stress Test (Sample 4). Participants were debriefed between Samples 2 and 3 and completed self-report measures in between providing saliva samples.

Measures

Trier Social Stress Test

The Trier Social Stress Test is one of the most widely used and well-validated psychological stressor that has been shown to induce a two- to four-fold increase in cortisol (e.g., Dickerson & Kemeny, Reference Dickerson and Kemeny2004; Kirschbaum, Pirke, & Hellhammer, Reference Kirschbaum, Pirke and Hellhammer1993). A modified version of the Trier Social Stress Test was administered to youth, and detailed explanation of modifications are discussed in Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Deardorff, Parra, Alkon, Eskenazi and Shirtcliff2017). In brief, the Trier Social Stress Test consisted of asking the youths to prepare a speech in solitude (3 min) about why they are good friend, which was to be delivered to two trained experts (confederates). After the 3-min preparation period, participants were walked to the Trier Social Stress Test room, where they delivered their speech to the confederates (5 min). Immediately after the 5-min speech, participants were asked to complete a math task aloud for 5 min. The participants were recorded via videorecorder as part of the stressor (Kirschbaum et al., Reference Kirschbaum, Pirke and Hellhammer1993).

Cultural orientation

Cultural orientation was assessed using the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (Bauman, Reference Bauman2005), a 12-item questionnaire adapted from the original 30-item Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans–II (Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, Reference Cuellar, Arnold and Maldonado1995), the most frequently used measure of acculturation that was created for clinical practice and research. Like the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans–II, the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans–II yields independent assessments of self-reported orientation to Mexican culture (6 items) and Anglo culture (6 items). The items from each subscale were summed and divided by 6, and the mean was used in subsequent analyses. Items evaluate the frequency (e.g., “How often is this true for you?”) with which youths interact and function within each cultural group and language in their daily lives. Items are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely, often, or almost always). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the two-orientation dimensional model. The items were under acceptable ranges of skewness and kurtosis for normal distribution of data (i.e., skewness ≤ 2 and kurtosis ≤ 7; see West, Finch, & Curran, Reference West, Finch, Curran and Hoyle1995). Mplus (Version 8; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017) was used to conduct CFA, using the maximum likelihood estimation. After allowing “I enjoy Spanish language” and “I enjoy Spanish language movies” to correlate and “I speak English” and “My friends are Anglos (Anglos are non-Latino people who speak English)” to correlate due to shared content, the model fit adequately, χ2 (51) = 183.41, p < .01, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .065, comparative fit index (CFI) = .924. The two orientation constructs were essentially independent to each other, with r = .014 (p = .81).

Family conflict

Adolescents’ report of family conflict were based on the family conflict subscales of the Multicultural Events Scale for Adolescents (Gonzales, Tein, Sandler, & Friedman, Reference Gonzales, Tein, Sandler and Friedman2001). The Multicultural Events Scale for Adolescents is a 70-item checklist of negative life events, which was created specifically for adolescents living in multiethnic environments. The family conflict subscale includes 9 items that index parent–child, interparental, and extended family conflicts (e.g., “You had a serious disagreement with your parents”), including culture-related conflicts among family members (e.g., “Family members disagreed about cultural traditions”). Adolescents endorsed whether each event happened in the past 3 months, and scores were based on a count of all items endorsed. Cronbach's α was 0.72 for the family conflict subscale for the current sample.

Youth familism

Familism was assessed using the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults (MACVS; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Gonzales, Saenz, Bonds, German, Deardorff and Updegraff2010). MACVS is a 50-item measure of different Latino cultural expectations. The MACVS is made up of nine subscales that assess both traditional and mainstream values on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely). Three of the five subscales that make up the Mexican American values scale were included in the current study: familism-support (6 items, e.g., “Parents should teach their children that the family always comes first”), familism-obligations (5 items, e.g., “If a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible”), and familism-referent (5 items, e.g., “A person should always think about their family when making important decisions”). Using a sample of 5th-grade Mexican American adolescents and another sample of 7th-grade Mexican American adolescents and their responses on MACVS, respectively, Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Gonzales, Saenz, Bonds, German, Deardorff and Updegraff2010) examined the dimensionality of the Mexican American values with a higher order CFA. Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Gonzales, Saenz, Bonds, German, Deardorff and Updegraff2010) concluded that the items and subscales were reliable lower order and higher order indicators of the overall construct, familism. Accordingly, the mean of the three subscales, which were in the same metrics (i.e., 0–5), was computed to make a composite score of familism. Internal consistency was good for the current sample (Cronbach's α = 0.84).

Salivary hormones

Saliva was collected following published protocols (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Granger, Susman, Gunnar and Laird1998) and frozen immediately (–80 °C). On the day of assay, each saliva sample was thawed and assayed within 24 hr for cortisol in duplicate using well-established highly sensitive enzyme immunoassay kits (www.salimetrics.com). All samples from an individual were assayed on the same kit to minimize measurement error. Hormones were assayed on the same day to minimize freeze-thaw cycles. Mean intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 12.4%, and mean inter-assay CVs were 6.9%. The sample was reanalyzed if the CV for the duplicate measurements were greater than 10%. To normalize distributions, extreme values were winsorized and raw hormones were log-transformed.

Analytic strategy

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the hypotheses using Mplus (Version 8; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017. Prior research confirms cortisol has a 15-min delay in response to stress (Dickerson & Kemeny, Reference Dickerson and Kemeny2004). Thus, piecewise growth curve modeling was used to model cortisol levels to the Trier Social Stress Test across the four assessments. We created our piecewise model based on sample statistics indicating that most participants (76.39%) reached their peak cortisol at 30 min post–Trier Social Stress Test onset (approximately 15 min after the Trier Social Stress Test was completed; Time 3). In comparison, 19.91% reached their peak 15 min after the Trier Social Stress Test onset (Time 2), 0.93% reached their peak at 45 min after Trier Social Stress Test onset (Time 4), and 2.77% were nonresponders (i.e., their peak was at baseline, Time 1). Therefore, cortisol concentration was modeled to reflect cortisol increase from Sample 1 to Sample 3 (reactivity), and a subsequent decline from Sample 3 to Sample 4 (recovery). The model was centered at Sample 3 as this strategy allowed the intercept to reflect peak cortisol levels given that most participants’ cortisol peaked at this sample. Such piecewise growth curve modeling allowed us to separately examine the effects of cultural orientation on three distinct HPA indices (i.e., peak cortisol levels, and reactivity and recovery phases), which is advantageous as the underlying mechanisms for the rise and subsequent fall in cortisol levels are distinct (Khoury et al., Reference Khoury, Gonzalez, Levitan, Pruessner, Chopra, Santo Basile and Atkinson2015; Kudielka, Hellhammer, & Wust, Reference Kudielka, Hellhammer and Wust2009), differentially index dysregulation (Siever & Davis, Reference Siever and Davis1985), and, in addition, HPA recovery from the Trier Social Stress Test has unique correlates (Kudielka, Buske-Kirschbaum, Hellhammer, & Kirschbaum, Reference Kudielka, Buske-Kirschbaum, Hellhammer and Kirschbaum2004a) and neural underpinnings (Herman, McKlveen, Solomon, Carvalho-Netto, & Myers, Reference Herman, McKlveen, Solomon, Carvalho-Netto and Myers2012). We considered alternative approaches to model the HPA response to stress, such as linear and quadratic slopes, but opted for piecewise slopes given the ease of interpretability of linear slopes and the advantage of having cortisol levels centered on Sample 3 (typically peak cortisol levels). Another common strategy is use of the area under the curve (Pruessner, Kirschbaum, Meinlschmid, & Hellhammer, Reference Pruessner, Kirschbaum, Meinlschmid and Hellhammer2003), which provides information about overall cortisol output (with respect to ground or Sample 1), but area under the curve would have provided limited information about the time course of the stress response (i.e., reactivity vs. recovery).

These growth factors (i.e., intercept and slopes) were then modeled as the dependent variables for testing the mediating effects of family conflict and familism on the relationship between cultural orientation and cortisol reactivity and recovery. It is important to note that each of these three HPA parameters is simultaneously modeled in a nested multilevel model; predictors are consequently exerting independent effects on cortisol levels or slopes, respectively. We conducted a sequence of SEMs to test the main and follow-up hypotheses. In the first model, the predictive effect of cultural orientation was tested on cortisol reactivity and recovery (Model 1). Next, separate mediating models were run to test whether family conflict (Model 2) and familism (Model 3) accounted for the relationship between cultural orientation and HPA functioning (peak cortisol levels, cortisol reactivity, and recovery to the Trier Social Stress Test). Figure 1 illustrates the mediation model with cultural orientation as the independent variable, family conflict as the mediator variable, and cortisol responsivity as the dependent variable. The same model was tested with familism as the mediator. We added the interaction between orientation to Mexican culture and orientation to Anglo culture for examining the effect of biculturalism (i.e., integration with both cultures). If the interaction was significant, then we probed for simple mediation effects for participants high on both cultures, or high on one culture, given hypotheses were made for these combinations of cultural identity. Fewer than 5% of participants were low on both cultural identities.

Figure 1. Structural equation model testing the mediation of family conflict in the relationship between cultural orientation and cortisol functioning.

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the study variables. Before examining Models 1–3, we first tested the effects of sex and income-to-poverty ratio as potential covariates in our models. Only sex significantly affected the cortisol model. We then conducted multigroup SEMs to examine whether the effects of cultural orientation on cortisol reactivity and recovery to the Trier Social Stress Test and whether the mediation effects of family conflict and familism for the relationship between cultural orientation and cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test differed across males or females. We compared the model that had the paths among cultural orientation, mediator, and the growth factors for cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test to be equivalent across sex (i.e., constrained model) with the model that had these paths to be different across sex (i.e., unconstrained model). If the constrained model was significantly different from the unconstrained model, we would conclude that some of the relations among cultural orientation, mediator, and the growth factors were significantly different between males and females and would present the model separately by sex. Otherwise, we included youth sex as a covariate, as boys tended to respond with steeper cortisol response to the Trier Social Stress Test, as previously found in other studies (Kirschbaum et al., Reference Kirschbaum, Pirke and Hellhammer1993). To determine model fit, we used the CFI (critical value .90; Bentler, Reference Bentler1990), and the RMSEA (critical value .08; Steiger, Reference Steiger1990). For all models, maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used. Missing data were handled with full information maximum likelihood estimation. We reported unstandardized regression coefficients and the corresponding confidence interval. In addition, we reported the standardized regression coefficients for the indications of the effect sizes (i.e., .14 for small effect, .39 for medium effect, and .59 for large effect; see Fritz & Mackinnon, Reference Fritz and Mackinnon2007).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Note: BARSMA-II, Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans–II. MESA, Multicultural Events Scale for Adolescents.

MACVS, Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults.

*p < .05.

Results

Sex differences

There were no sex differences for Model 1, unconstrained model: χ2 (12) = 16.70, p = .16, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .99; constrained model: χ2 (21) = 28.151, p = .14, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .985; difference of df (Δdf) = 9 and difference of χ2 (Δ χ2) = 11.45, p = .75; Model 2, unconstrained model: χ2 (8) = 26.83, p < .001, RMSEA = .08, CFI = .97; constrained model: χ2 (23) = 40.16, p = .02, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .97; Δdf = 15 and Δ χ2 = 13.33, p = .42; and Model 3, unconstrained model: χ2 (8) = 23.02, p < .003, RMSEA = .07, CFI = .97; constrained model: χ2 (23) = 38.28, p = .02, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .97; Δdf = 15 and Δ χ2 = 15.26, p = .28. As a result, we conducted the models only including sex as a covariate.

Model 1: Does cultural orientation predict cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test?

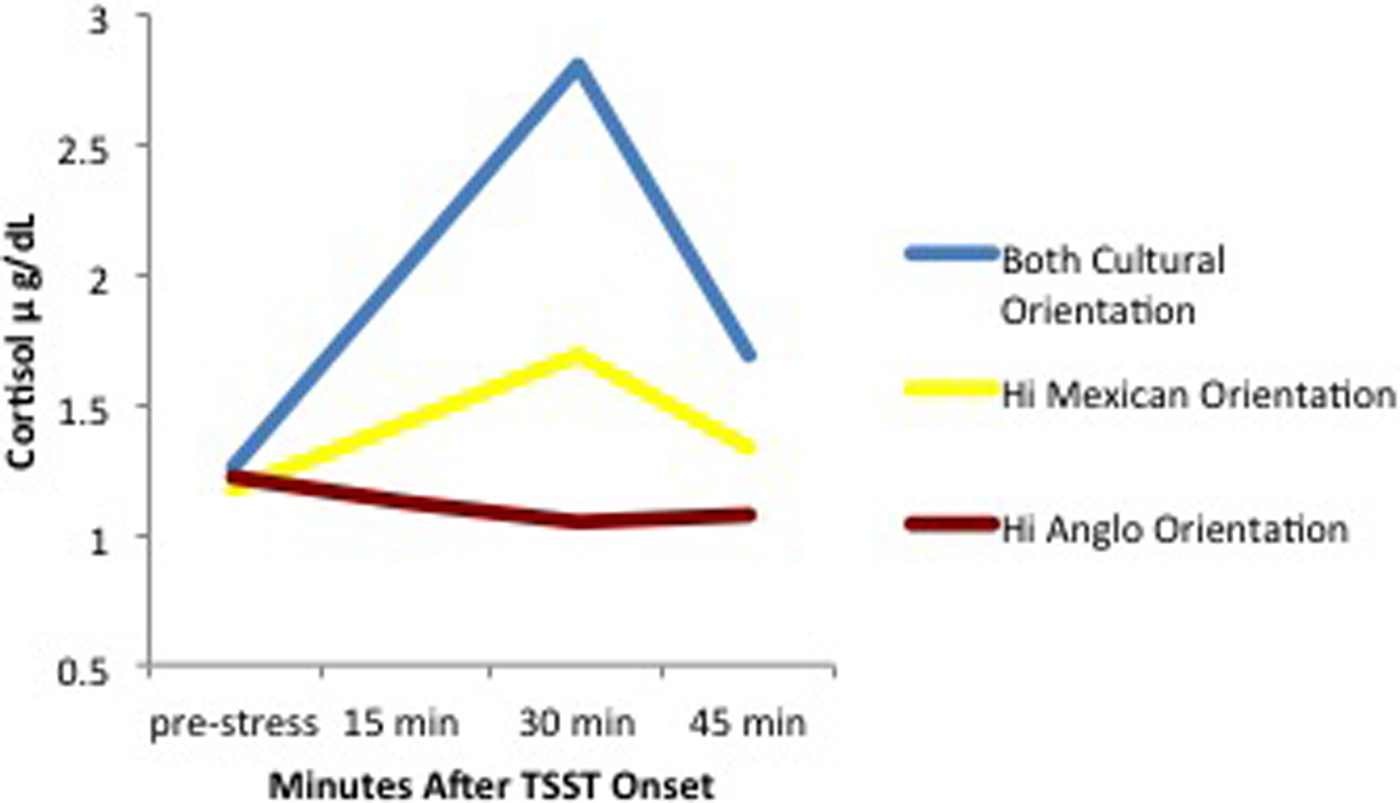

The effects of Mexican orientation, Anglo orientation, and the interaction between the two were estimated in prediction of cortisol reactivity, intercept (i.e., peak), and recovery from the Trier Social Stress Test, while controlling for sex. Model fit was acceptable: χ2 (10) = 15.06, p = .13, RMSEA = .02, CFI = .99. Table 2 provides the complete parameter estimates for the effects of cultural orientation variables to the growth factors of cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test for Model 1. After controlling for the effect of sex, the interaction between Mexican and Anglo orientations significantly predicted cortisol reactivity slope, cortisol peak, and recovery. Specifically, as depicted in Figure 2, individuals reporting high levels of both Mexican and Anglo orientation demonstrated a steeper increase in cortisol reactivity and higher cortisol peak. Conversely, individuals endorsing only high levels of Anglo orientation had the flattest cortisol reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Test, with lower peak. Fewer than 5% of people self-reported being low on both cultural orientations (i.e., less than a 3 on Mexican and Anglo orientation on the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans–II), and thus this group was not considered when probing interactions.

Figure 2. Cortisol reactivity to stress as predicted by structural equation modeling at 2 SD above and below the estimated mean on Mexican and Anglo orientation.

Table 2. Parameter estimates for the effects of cultural orientation variables to the growth factors of cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test for Model 1

*p ≤ .01.

Model 2: Does family conflict mediate the relationship between cultural orientation and cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test?

The mediating effect of family conflict was estimated in the relationship between cultural orientation and cortisol responsivity, controlling for sex. Model fit was acceptable: χ2 (8) = 24.57, p < .001, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97. Table 3 provides the complete parameter estimates for the effects from cultural orientation variables to family conflict and from family conflict to the growth factors of cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test for Model 2. Mexican orientation, Anglo orientation, and the interaction of the two did not significantly predict family conflict. In contrast, after controlling for the cultural orientation variables (i.e., the predictors), family conflict significantly predicted blunted cortisol reactivity, lower cortisol peak, and less recovery from the Trier Social Stress Test. The interaction between Mexican and Anglo orientations remain significant in its effects on cortisol reactivity slope, cortisol peak, and recovery. These effects in general were in the small to medium range. In sum, the criterion for mediation was not met, as the independent variables (cultural orientation) and their interaction did not predict the mediator (family conflict).

Table 3. Parameter estimates for the effects from cultural orientation variables to family conflict and from family conflict to the growth factors of cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test for Model 2

a90% confidence interval.

*p ≤ .05.

Model 3: Does familism mediate the relationship between cultural orientation and cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test?

The mediating effect of familism was estimated in the relationship between cultural orientation and cortisol responsivity, controlling for sex differences. Model fit was acceptable: χ2 (8) = 20.55, p < .01, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .98. Table 4 provides the complete parameter estimates for the effects from cultural orientation variables to familism and from familism to the growth factors of cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test for Model 3. The direct effect from interaction between Mexican and Anglo orientations to the cortisol growth factors remained significant: cortisol reactivity slope, cortisol peak, and recovery. These effects in general were in the small to medium range. However, Mexican orientation, Anglo orientation, and the interaction of the two did not significantly predicted familism. After controlling for the cultural orientation variables (i.e., the predictors), familism also did not significantly predict cortisol reactivity, cortisol peak, or recovery from the Trier Social Stress Test. Thus, the criterion for mediation was not met.

Table 4. Parameter estimates for the effects from cultural orientation variables to familism and from familism to the growth factors of cortisol responsivity to the Trier Social Stress Test for Model 3

a90% confidence interval.

*p ≤ .05.

Discussion

There is a dearth of studies that consider race/ethnicity and HPA functioning, despite theories that both stressful and protective experiences shape HPA development and responsivity. Prior studies have shown that, relative to Whites, minority adolescents or young adults have lower cortisol levels (Brondolo, Reference Brondolo2015; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Shirtcliff, Haggerty, Coe and Catalano2011), diminished cortisol reactivity (Hostinar, McQuillan, Mirous, Grant, & Adam, Reference Hostinar, McQuillan, Mirous, Grant and Adam2014; Lewis, Ramsay, & Kawakami, Reference Lewis, Ramsay and Kawakami1993), as well as attenuated cortisol decline across the day (Cohen, Doyle, & Baum, Reference Cohen, Doyle and Baum2006; DeSantis et al., Reference DeSantis, Adam, Doane, Mineka, Zinbarg and Craske2007). Racial/ethnic differences persist even when examining correlates of inequity (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Shirtcliff, Haggerty, Coe and Catalano2011), and yet group comparisons of the correlates of race/ethnicity do not shed light on salient experiences that may uniquely shape HPA development in minority youth. Examining both risk and protective processes within Mexican American youth fills an important knowledge gap because they are a vastly understudied population in psychobiological research (Luecken et al., Reference Luecken, Lin, Coburn, MacKinnon, Gonzales and Crnic2013; Obasi et al., Reference Obasi, Shirtcliff, Brody, MacKillop, Pittman, Cavanagh and Philibert2015, Reference Obasi, Shirtcliff, Cavanagh, Ratliff, Pittman and Brooks2017) and because such studies stand to inform about basic underlying processes related to cultural influences on stress and adaptation. Addressing this gap, the present study found that Mexican American adolescents’ cultural orientation significantly altered their cortisol reactivity to an acute laboratory stressor, but this was not mediated by family-related risk (conflict) or protective (familism) resources. Instead, we found youth who reported a strong orientation to both their Mexican (Spanish-language) culture as well as the Anglo (English-language) culture showed the expected cortisol reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Test and recovery after stress, and this pattern was significantly different from youth strongly aligned with only one culture (Mexican or Anglo).

Finding that bicultural youth have elevated cortisol reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Test raises the question of whether elevated cortisol is advantageous for these youth. The HPA axis is dynamic, and individual differences in cortisol responsivity are important (Gunnar, Wewerka, Frenn, Long, & Griggs, Reference Gunnar, Wewerka, Frenn, Long and Griggs2009; Kudielka, Buske-Kirschbaum, Hellhammer, & Kirschbaum, Reference Kudielka, Buske-Kirschbaum, Hellhammer and Kirschbaum2004b; McRae et al., Reference McRae, Saladin, Brady, Upadhyaya, Back and Timmerman2006; O'Leary, Loney, & Eckel, Reference O'Leary, Loney and Eckel2007), with most of cortisol's variability attributable to social contextual factors and the interaction of the individual with their environment (Shirtcliff & Essex, Reference Shirtcliff and Essex2008; Shirtcliff, Granger, Booth, & Johnson, Reference Shirtcliff, Granger, Booth and Johnson2005). Many stressors succeed in stimulating other stress-responsive physiological systems (Gordis, Granger, Susman, & Trickett, Reference Gordis, Granger, Susman and Trickett2006), but are not sufficient for the HPA axis (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Hamrick, Rodriguez, Feldman, Rabin and Manuck2000). Dickerson and Kemeny's (Reference Dickerson and Kemeny2004) meta-analysis found that the Trier Social Stress Test emerged as the most robust stressor because it contained social evaluative threat (Kirschbaum et al., Reference Kirschbaum, Pirke and Hellhammer1993). Since that meta-analysis, several studies have explored how modifications to the Trier Social Stress Test influence cortisol reactivity by, for example, changing the number of confederates (Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, de Geus, Carroll, Goedhart, Anane, van Zanten and Edwards2009; Bouma, Riese, Ormel, Verhulst, & Oldehinkel, Reference Bouma, Riese, Ormel, Verhulst and Oldehinkel2009; Dickerson, Mycek, & Zaldivar, Reference Dickerson, Mycek and Zaldivar2008; Het, Rohleder, Schoofs, Kirschbaum, & Wolf, Reference Het, Rohleder, Schoofs, Kirschbaum and Wolf2009) or using a distant audience (Kelly, Matheson, Martinez, Merali, & Anisman, Reference Kelly, Matheson, Martinez, Merali and Anisman2007; Wadiwalla et al., Reference Wadiwalla, Andrews, Lai, Buss, Lupien and Pruessner2010; Westenberg et al., Reference Westenberg, Bokhorst, Miers, Sumter, Kallen, van Pelt and Blote2009). Adding negative commentary increases cortisol reactivity (Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson, Mycek and Zaldivar2008; Phan et al., Reference Phan, Schneider, Peres, Miocevic, Meyer and Shirtcliff2017; Schwabe, Haddad, & Schachinger, Reference Schwabe, Haddad and Schachinger2008), whereas positive or supportive commentary reduces reactivity (Het et al., Reference Het, Rohleder, Schoofs, Kirschbaum and Wolf2009; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Seeman, Eisenberger, Kozanian, Moore and Moons2010; Wiemers, Schoofs, & Wolf, Reference Wiemers, Schoofs and Wolf2013). Cortisol reactivity is also influenced by increasing participants’ psychosocial resources or self-confidence prior to the Trier Social Stress Test (Britton, Shahar, Szepsenwol, & Jacobs, Reference Britton, Shahar, Szepsenwol and Jacobs2012; Brown, Weinstein, & Creswell, Reference Brown, Weinstein and Creswell2012; Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Welch, Taylor, Sherman, Gruenewald and Mann2005; Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell, & Pedersen, Reference Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell and Pedersen2009; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Burklund, Eisenberger, Lehman, Hilmert and Lieberman2008) or their vigilance to the stressor (Cavanagh & Allen, Reference Cavanagh and Allen2008; Lam, Dickerson, Zoccola, & Zaldivar, Reference Lam, Dickerson, Zoccola and Zaldivar2009; Pilgrim, Marin, & Lupien, Reference Pilgrim, Marin and Lupien2010). It would be tempting to conclude from these studies that HPA reactivity is problematic, but an alternative interpretation is that these studies reveal that most individuals are sensitive to social evaluative threat, with about 70% of individuals typically responsive to the Trier Social Stress Test, and this cortisol reactivity can be increased further by systematically increasing the salience of the social context. That is, there are contexts that call for a stress response, and the Trier Social Stress Test has been designed and refined (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Deardorff, Parra, Alkon, Eskenazi and Shirtcliff2017) to be a context that delivers consistent, robust cortisol responsivity. If that is the case, then bicultural youth were more likely to express the common or typical cortisol response to this salient social evaluative context.

Conversely, the present study found that Mexican American youth who exclusively endorsed either high Anglo or high Mexican cultural orientation were more likely to be stress nonresponsive. This pattern was most pronounced for the most assimilated (Anglo-oriented) youth in the sample. Cortisol hypoarousal may be problematic for some individuals in a social context where the majority of individuals are reactive (Petrowski, Herold, Joraschky, Wittchen, & Kirschbaum, Reference Petrowski, Herold, Joraschky, Wittchen and Kirschbaum2010) as it may signal a low capacity to mount a stress response even if the situation calls for it. Lack of HPA malleability may reduce an individual's ability to recalibrate physiological functioning to meet the demands of a changing environment. Given that one of the main functions of the HPA axis is to terminate a diversity of stress responses, nonresponders may also be paradoxically at heightened risk for stress-related diseases (Miller, Chen, & Zhou, Reference Miller, Chen and Zhou2007; Raubenheimer, Young, Andrew, & Seckl, Reference Raubenheimer, Young, Andrew and Seckl2006) including psychopathology symptoms (Gunnar & Vazquez, Reference Gunnar and Vazquez2001; Shirtcliff et al., Reference Shirtcliff, Vitacco, Graf, Gostisha, Merz and Zahn-Waxler2009; Yehuda, Reference Yehuda2000). This does not imply that all nonresponders are maladaptive, as extant theory emphasizes that both high and low cortisol levels come with trade-offs (Del Giudice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Ellis, Shirtcliff, Laviola and Macri2013). Some individuals may be Trier Social Stress Test nonresponders when they appraise a stressor, but regulate responsivity prior to crossing the relatively high stress threshold of the HPA (Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, de Geus, Carroll, Goedhart, Anane, van Zanten and Edwards2009). In that case, low cortisol responsivity indicates that the stressor was mild, or the individual was able to cope or self-regulate prior to stimulating HPA activity (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Oakes, Stone, McAuliff, Kirschbaum and Davidson2008).

Outside of our own work with this CHAMACOS cohort (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Deardorff, Parra, Alkon, Eskenazi and Shirtcliff2017), there are no studies (to our knowledge) that have examined cortisol reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Test in Mexican American youth, so it is difficult to determine whether the cortisol hypoarousal evident in youth with either an Anglo or Mexican cultural orientation is advantageous. Our finding that family conflict was associated with blunted cortisol reactivity emphasizes the costs of cortisol hypoarousal. Within rural African Americans, Obasi et al. (Reference Obasi, Shirtcliff, Cavanagh, Ratliff, Pittman and Brooks2017) found that blunted reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Test was linked with greater stress and lower family support within a minority sample. We draw from Mangold et al.’s (Reference Mangold, Wand, Javors and Mintz2010) research on the cortisol awakening response (another HPA measure in which blunted levels may indicate lack of malleability or physiological flexibility) in order to interpret cortisol hypoarousal in Mexican Americans. This research group initially found that higher acculturation was associated with a blunted cortisol awakening response. A blunted cortisol awakening response was also associated with depressive symptomatology (Mangold, Marino, & Javors, Reference Mangold, Marino and Javors2011), neuroticism (Mangold et al., Reference Mangold, Wand, Javors and Mintz2010), and poorer self-reported health (Garcia, Wilborn, & Mangold, Reference Garcia, Wilborn and Mangold2017). This research fits with the idea that hypoarousal may be problematic if it signals physiological inflexibility (Obasi et al., Reference Obasi, Shirtcliff, Brody, MacKillop, Pittman, Cavanagh and Philibert2015). However, Mangold et al. (Reference Mangold, Wand, Javors and Mintz2010) found a blunted cortisol awakening response was associated with increased acculturation and acculturative stress (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Wilborn and Mangold2017). While potentially seeming incongruent with our finding of high cortisol reactivity in bicultural individuals, we suggest instead that this emphasizes the trade-offs of high cortisol: while Mexican Americans may benefit from the flexibility of a contextually responsive HPA axis and bicultural orientation, there are also costs of high cortisol allowing the individual to be more open to acculturative stress of living in an Anglo world. Perhaps our findings show that when bicultural youths retain cultural practices and integration with their ethnic culture in the process, they simultaneously remain open and responsive to social opportunities and challenges yet receive protective benefits that may serve to facilitate recovery and reduce the wear and tear of acculturative stress over time. Prior research has not previously considered acculturation and enculturation together to tease out more nuanced patterns of adaptation, but these findings clearly indicate that both axes should be considered in future research linking cultural orientation with HPA functioning.

One important takeaway message from the present study findings and those of the extant literature is that there is no clear HPA profile that signals an adaptive or desirable stress response. This complexity of the HPA axis was emphasized in a meta-analysis by Korous et al. (Reference Korous, Causadias and Casper2017), who reached the conclusion that the association between racial discrimination is likely nonlinear, such that a nonsignificant overall effect size was apparent across 16 studies; nonetheless, this average was misleading, collapsing across studies that revealed clear links with HPA hypoarousal while others found HPA hyperarousal. Within a single study, Skinner et al. (Reference Skinner, Shirtcliff, Haggerty, Coe and Catalano2011) reached similar conclusions such that stress exposure was associated with both lower and higher cortisol levels within African American youth. Put another way, the present study cautions against an interpretation in which high (or low) cortisol is good or bad, but rather the interplay of the HPA axis in context matters (Korous et al., Reference Korous, Causadias and Casper2017; Shirtcliff et al., Reference Shirtcliff, Peres, Dismukes, Lee and Phan2014). Consider results of an experimental study that found greater cortisol exposure in emerging adults exposed to indirect discrimination as compared to the control group (Huynh, Huynh, & Stein, Reference Huynh, Huynh and Stein2017); this arousal could be interpreted as an undesirable stress response or it may represent an open and flexible HPA axis that is still attuned to the social and emotional tenor of witnessing ethnic discrimination from one's peers. Prior studies have found HPA axis attunement within the most sensitive individuals and dyads (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Gonzalez, Kashy, Santo Basile, Masellis, Pereira and Levitan2013; Hibel, Granger, Blair, Finegood, & Family Life Project Key Investigators, Reference Hibel, Granger, Blair and Finegood2015; Ruttle, Serbin, Stack, Schwartzman, & Shirtcliff, Reference Ruttle, Serbin, Stack, Schwartzman and Shirtcliff2011; van Bakel & Riksen-Walraven, Reference van Bakel and Riksen-Walraven2008), and extant theories postulate this is an important mechanism for social buffering and support (Gunnar & Hostinar, Reference Gunnar and Hostinar2015; Hostinar & Gunnar, Reference Hostinar and Gunnar2013). While exposure to stress, discrimination, and racism is inarguably an undesirable context, it is important to resist the temptation to pathologize the physiological response to such adversity as evidence of dysregulation or maladaptation and instead recognize the complexities of physiological costs and benefits of adaptation (Del Giudice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011, Reference Del Giudice, Ellis, Shirtcliff, Laviola and Macri2013; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Del Giudice, Shirtcliff, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2012).

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

The current study introduced a bidimensional approach to research on HPA functioning that better aligns this research with contemporary theories of acculturation (Berry, Reference Berry1997) and with growing evidence of the adaptive significance of biculturalism and the superiority of bidimensional assessments relative to typological and unidimensional measures of biculturalism (Celenk & Van de Vijver, Reference Celenk and Van de Vijver2011; Nguyen & Benet-Martinez, Reference Nguyen and Benet-Martinez2013). However, our assessments were limited to the linguistic and affiliation dimensions of cultural orientation that do not capture the full range of cultural dimensions relevant in research on cultural adaptation (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga and Szapocznik2010). Nevertheless, the novel and striking effects we found to predict patterns of cortisol response suggest that cultural adaptation plays a role in the adaptive calibration of stress responsivity, and adds to the growing evidence that biculturalism may offer unique advantages for acculturating adolescents (Nguyen & Benet-Martinez, Reference Nguyen and Benet-Martinez2013). Our prospective design was another strength that allowed stronger causal inferences, but we did not model changes in cultural adaptation that might have occurred between the assessments of cultural orientation (age 12) and later cortisol reactivity (age 14). Although prior research supports relative stability in adolescence on the domains of cultural orientation assessed, future studies would benefit from a more comprehensive assessment of cultural orientation to capture additional dimensions, such as ethnic identity and values, and assessments of cortisol reactivity concurrently as well as prospectively.

Our sample of second-generation youth provided a relevant context to examine cultural adaptation of youths exposed to traditional and dominant or mainstream cultural systems. All of the CHAMACOS youths lived in the United States since birth, attended schools in English, and were exposed to both Mexican and Anglo peer groups. Yet the surrounding community made it possible for continued immersion in Mexican-oriented communities where many youths could continue to interact in predominantly Spanish-speaking settings. Given the lower income status of the sample and social stratification of Latinos in this broader community, it is likely these Latino youths were exposed to daily challenges generated by a racially stratified society (e.g., segregated high schools or discrimination on campus). Although these conditions are increasingly common in communities across the United States and globally, particularly with recent historic rates of immigration and rising social inequality, it is important to remember the opportunities for bicultural adaptation and the adaptiveness of biculturalism are likely to be context specific and may not generalize across community contexts (Schwartz & Zamboanga, Reference Schwartz and Zamboanga2008).

Although we did not find evidence of mediation through family conflict or familism to account for cultural adaptation effects on stress responsivity, the study did not assess the broad array of plausible underlying mechanisms, including other cultural risk factors (i.e., discrimination experiences; Zeiders, Doane, & Roosa, Reference Zeiders, Doane and Roosa2012) or cultural resources (i.e., ethnic identity; Umaña-Taylor et al., Reference Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, Lee, Cross, Rivas-Drake and Schwartz2014) that are theoretically relevant to our theorizing about the potential costs and benefits of acculturation and biculturalism. Studies specifically linking discrimination with diurnal cortisol (i.e., flatter diurnal slopes) among racial/ethnic minority youth (including Mexican Americans) suggests it may be a key factor in heightened stress responsivity and long-term wear and tear as early as adolescence (DeSantis et al., Reference DeSantis, Adam, Doane, Mineka, Zinbarg and Craske2007; Zeiders et al., Reference Zeiders, Doane and Roosa2012). Continued focus on racial/ethnic or culturally based stressors is thus warranted. However, we also acknowledge that cultural resources and strengths are also important to inform transactions between culture and neurobiology (Causadias et al., Reference Causadias, Telzer and Gonzales2017), and to identify promotive cultural processes that enable some racial/ethnic minorities to achieve positive adaptation despite the challenges of bicultural integration.