Introduction

Intergenerational transmission of mental health problems is believed to be a substantial contributor to psychiatric morbidity (Netsi, Pearson, Murray, & Cooper, Reference Netsi, Pearson, Murray and Cooper2018; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014) with children born to parents with mental health conditions being more likely to develop related psychiatric difficulties (Beardslee, Gladstone, & O'Connor, Reference Beardslee, Gladstone and O'Connor2011; van Santvoort, Hosman, van Doesum, Reupert, & van Loon, Reference van Santvoort, Hosman, van Doesum, Reupert and van Loon2015). In addition, children born to parents with mental health problems are at increased risk of developmental delays and other adverse outcomes such as poor academic performance, impaired cognitive abilities, elevated risks of suicide, and child abuse (Beardslee et al., Reference Beardslee, Gladstone and O'Connor2011; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011; Hosman, van Doesum, & van Santvoort, Reference Hosman, van Doesum and van Santvoort2009; Milgrom, Westley, & Gemmill, Reference Milgrom, Westley and Gemmill2004; van Santvoort et al., Reference van Santvoort, Hosman, van Doesum, Reupert and van Loon2015). These risks are largely mediated by the impact of parental mental illness on the Parent×Infant interaction, with the parent–infant relationship quality being a strong predictor of future infant attachment as well as impacting infant emotional and behavioral disorders (Barlow, Bennett, Midgley, Larkin, & Wei, Reference Barlow, Bennett, Midgley, Larkin and Wei2015; Skovgaard, Reference Skovgaard2010). It is thought that parental ability to interpret their infants’ internal emotional state and respond appropriately to this, termed “reflective function” (Beebe et al., Reference Beebe, Jaffe, Markese, Buck, Chen, Cohen and Feldstein2010) or “mind-mindedness” (Meins, Fernyhough, Fradley, & Tuckey, Reference Meins, Fernyhough, Fradley and Tuckey2001) is impacted by parental mental illness, and these difficulties mediate the effect of these mental health problems on infant outcomes (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Bennett, Midgley, Larkin and Wei2015; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van Ijzendoorn, Moran, Pederson and Benoit2006).

The perinatal period, defined here as from pregnancy through to the first year postpartum, presents an important opportunity for interventions to protect and improve children's mental health (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014; van Doesum & Hosman, Reference van Doesum and Hosman2009; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Hackney, Hughes, Barry, Glaser, Prior and McMillan2017) by supporting the parent–infant relationship (Meltzer-Brody et al., Reference Meltzer-Brody, Howard, Bergink, Vigod, Jones, Munk-Olsen and Milgrom2018; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014). Maternal mental health problems are associated with reduced parenting sensitivity, hostility, rejection, and low involvement (Hosman et al., Reference Hosman, van Doesum and van Santvoort2009), meaning that infants are more likely to develop insecure attachment styles, which consequently places them at risk of low social competence, internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and psychopathology later in childhood and throughout their life (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009; Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper, & Cooper, Reference Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper and Cooper1996; Velders et al., Reference Velders, Dieleman, Henrichs, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2011; Wan & Green, Reference Wan and Green2009; Korhonen, Luoma, Salmelin, & Tamminen, Reference Korhonen, Luoma, Salmelin and Tamminen2012). The benefits of these targeted early life interventions are thought to be long-lasting, and may prevent the occurrence of mental health difficulties in adolescence and adulthood (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn and Juffer2005; Hosman et al., Reference Hosman, van Doesum and van Santvoort2009; Leman, Bremner, Parke, & Gauvain, Reference Leman, Bremner, Parke and Gauvain2012; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014; van Doesum & Hosman, Reference van Doesum and Hosman2009; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Barry, Hughes, Trépel, Ali, Allgar and Gilbody2015).

Interventions for mental health currently delivered in perinatal specialist services are diverse, and include group and individual psychotherapies, infant massage, and video feedback interventions, in which Mother×Infant interactions are filmed to provide mothers with feedback on specific moments (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014). In the UK, service improvements are currently underway with a planned investment that will provide specialist care to 30,000 additional women per year by the end of 2021 (NHS England, 2016) to improve outcomes both for women experiencing perinatal mental health difficulties and for their infants. It is unlikely that a single intervention will be effective in improving infant outcomes for every mother–infant dyad, or be appropriate in all clinical settings. Therefore understanding whether common elements are found in effective perinatal mental health interventions is important to inform perinatal clinical practice, mental health service provision, and future research.

We reviewed studies of interventions carried out in the first year postpartum among women with perinatal mental health problems to identify components that successful interventions had in common. Previous reviews have included studies of mothers and infants at high risk for interaction difficulties for reasons other than mental health, for example low socioeconomic status or preterm birth (Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn and Juffer2003), mothers with antenatal or postnatal depression (Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic, & Linder, Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic and Linder2017), or mothers with older children than included in this review (Wright & Edginton, Reference Wright and Edginton2016). We focused on studies including women with any type of mental health problem, in which the intervention was initiated within the first year of the infant's life, in order to focus specifically on the perinatal period, and studies which included measures of infant development, mental health or wellbeing, or of Mother×Infant interaction quality. Our aim was to comprehensively review and synthesize published evidence of the effectiveness of interventions delivered to mothers experiencing serious perinatal mental health difficulties in improving infant and mother–infant relationship outcomes.

Method

Eligibility criteria

We sought to identify all papers published in the English language investigating the effectiveness of any perinatal intervention for mothers with perinatal mental health difficulties on infant mental health and/or development, and/or Mother×Infant interaction quality. The definition of the intervention was broad, encompassing talking therapies, video feedback on interactions and physical interventions such as infant massage.

Inclusion criteria for studies were:

(a) features an interventional study design using a control group, although randomization was not a requirement;

(b) involves mothers experiencing perinatal mental health difficulties, either during pregnancy or with infants with mean age <12 months at study entry;

(c) assesses any clearly described intervention aimed at improving or protecting Mother×Infant interaction quality and/or infant mental health and development, including dyadic, individual or group therapies, infant massage, or other forms of therapy; and

(d) includes at least one outcome measure of infant mental health, development or wellbeing, or a measure of mother–infant relationship quality.

Exclusion criteria for studies were:

(a) absence of control group, or a noninterventional study design (e.g. observational studies, review articles);

(b) includes infants with mean infant age >12 months at study entry;

(c) includes mothers without a defined mental health difficulties or focuses exclusively on fathers;

(d) assesses solely pharmacological treatment of maternal mental health difficulties; and

(e) does not measure any infant mental health, development or wellbeing outcomes or outcomes assessing mother–infant relationship quality.

Search strategy and data sources

Search strategies included electronic database searches and citation searching of included papers, in addition to hand-searching of reference lists of included studies.

Electronic searches

Nine electronic databases were searched from inception to 2nd January 2019, using three different interfaces: MEDLINE (via OvidSP), EMBASE (via OvidSP), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, via EBSCO), PsychINFO (via OvidSP), Education Resource Information Centre (ERIC, via EBSCO), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA, via ProQuest), Sociology and Social Services Abstracts (via ProQuest), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Web of Science. The search strategy was developed with help from an information search specialist at the University of Sheffield. The search terms used were adapted to each database and interface as required, and for some databases included a methodological filter. The searches made use of MeSH and other subject headings, adjacent word searching (e.g. adj3) and specific field searching where available (e.g. .ti,ab to search in only the titles and abstracts). Full search strategies are available in online Supplementary tables.

Additional searches

For all included papers, both reference list and citation searching were performed. Reference list searching was performed by hand, checking for potentially relevant titles. Citation searching was performed using the citation search function on Google Scholar.

Procedures

Retrieved records were downloaded into bibliographic software Mendeley Desktop Reference Manager (version 1.18, Mac 2012) and compiled into a Microsoft Excel (version 14.7.7, Mac 2011) spreadsheet. A single reviewer assessed all titles and then abstracts for potentially eligible papers, before discussing all decisions made at the full-text stage of study selection with a second reviewer.

Data extraction and quality assessment

An adaptation of the Cochrane Collaboration data extraction form for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012) was piloted using two eligible studies before being used across all eligible studies. Quality assessment was conducted using the Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias Tool (The Cochrane Collaboration, Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2011). The computer software Review Manager (version 5.3) was then used to create summary charts of the quality assessment results.

Analysis

Data on the components of the interventions were extracted and tabulated from all included papers, in order to develop a matrix mapping the key components of the studies against the study results, highlighting those that were most prevalent in the group of interventions that led to significant positive differences in infant or mother–infant relationship outcomes. Outcome data were assessed for the possibility of pooling quantitative measures via meta-analysis, where suitably homogenous. Two authors worked collaboratively to identify and agree the key components of the interventions. This analysis was based on the description of the interventions given in the papers, and was restricted to the information supplied therein.

Results

Search results

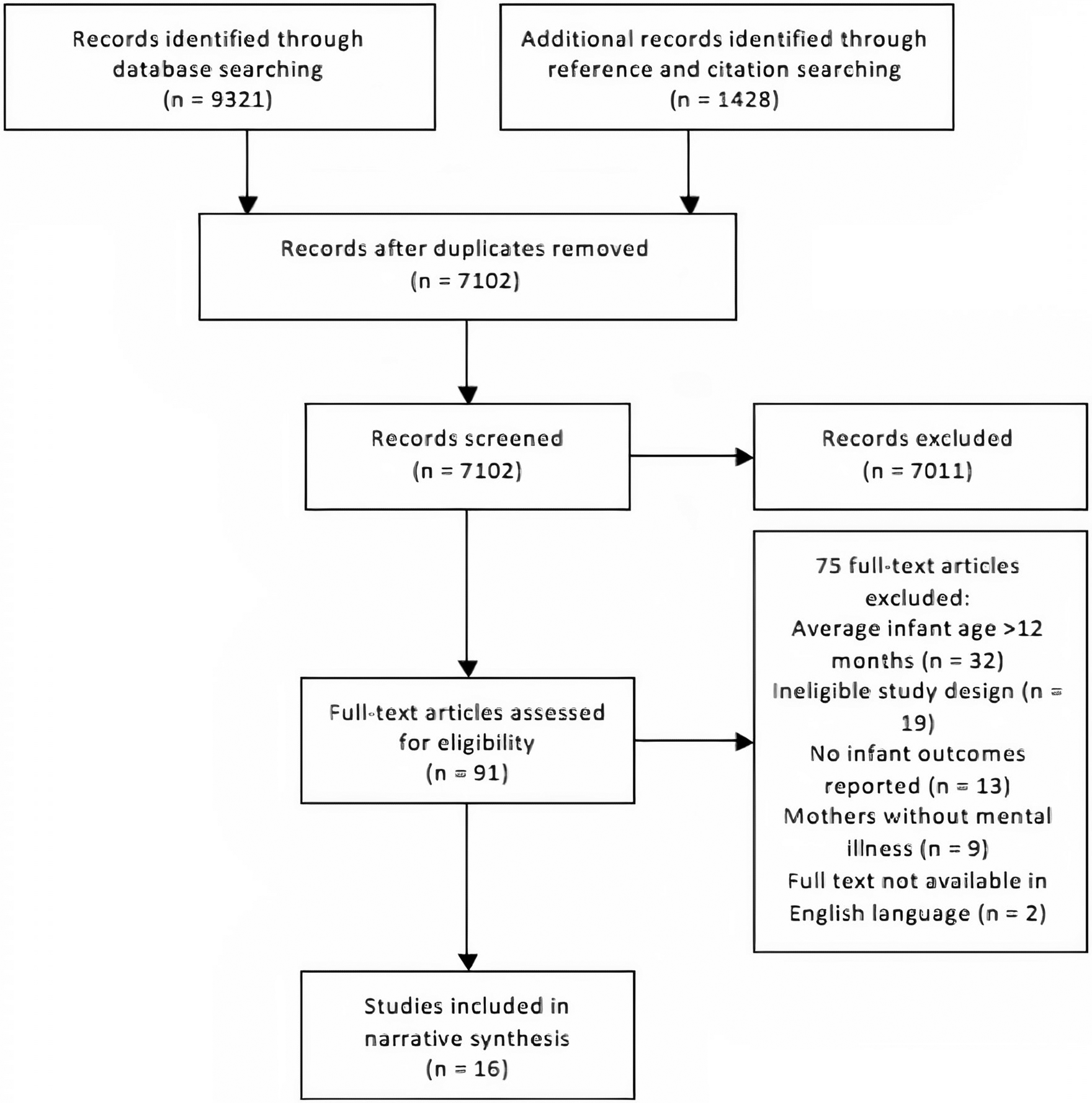

Searches retrieved 7,102 unique results, of which 7,011 were excluded after title and abstract screening (Figure 1). Niniey-one full-text publications were retrieved, of which 75 were excluded. Of these, 32 were excluded due to including children over 12 months old, 19 featured an ineligible study design (for example, lack of control group), 13 only assessed maternal outcomes, nine did not specifically include mothers with mental health difficulties and two were not available in English. A full table of reasons for exclusion for each study has been included in the online Supplementary.

Figure 1. Flow diagram displaying search results.

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 16 studies involving 1,075 participants were included in the review (see Table 1). Studies were published between 2001 (Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi, & Kumar, Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001) and 2018 (Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt, & Gemmill, Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018) and were conducted in the UK (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017; Fonagy, Sleed, & Baradon, Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016; Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne, & Pawlby, Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Murray, Cooper, Wilson, & Romaniuk, Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003; Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; O'Higgins, Reference O'Higgins2006; Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey, & Longford, Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017), the Netherlands (van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman, & Hoefnagels, Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008), Italy (Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino, & Ballarotto, Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015), Canada (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011), the USA (Clark, Tluczek, & Brown, Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008), and Australia (Ericksen et al., Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018).

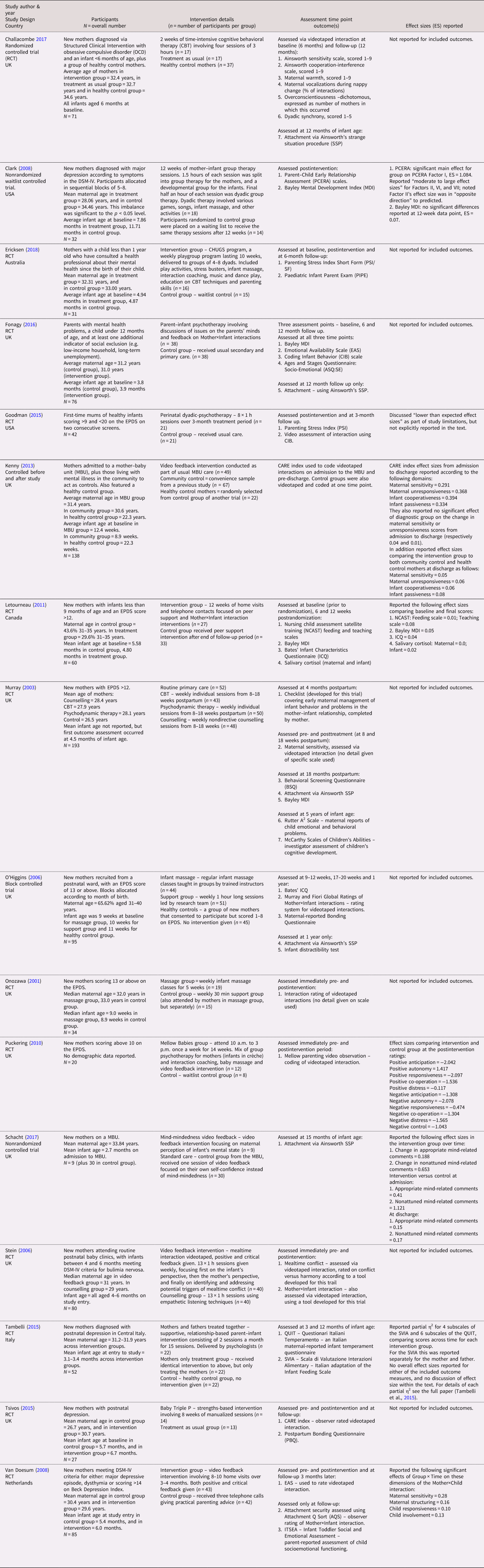

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies and relevant effect sizes where reported

Inclusion criteria and definitions of maternal mental health difficulties varied between papers. Eight studies included mothers with postnatal depression (PND; Goodman, Prager, Goldstein, & Freeman, Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015; Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003; Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; O'Higgins, Reference O'Higgins2006; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Tambelli et al., Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015; Tsivos, Calam, Sanders, & Wittkowski, Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015), two studies recruited participants from inpatient mother–baby units (MBUs; Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017), a further two recruited participants with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-IV) criteria (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008), and one included mothers with any “mental health problems” (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016). Finally, one study included mothers diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017), and another mothers with bulimia nervosa (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006). Of the three studies that did not specify a single diagnosis in their participant inclusion criteria (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016; Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017), only Kenny et al. (Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013) reported their outcomes as a function of the maternal diagnoses.

Included studies investigated a range of interventions and used 34 different outcome measures to evaluate the effects on infant mental health or development, and/or mother–infant relationship quality. Maternal outcomes were included in most studies but such outcomes, other than mother–infant relationship, were beyond the scope of this review. The methodological heterogeneity of studies that were frequently assessing similar outcomes using different measures prevented the use of meta-analytical techniques to synthesize data and compare the results of the included studies. Furthermore, many of the studies involved complex, multifaceted intervention programs with different formats, which meant it was not possible to group studies according to intervention type. While the methodological heterogeneity of included studies precluded formal synthesis of study outcome data, a narrative synthesis of the study results was conducted, drawing out the common components of interventions that were most associated with significant improvements in the outcomes of interest.

Quality assessment

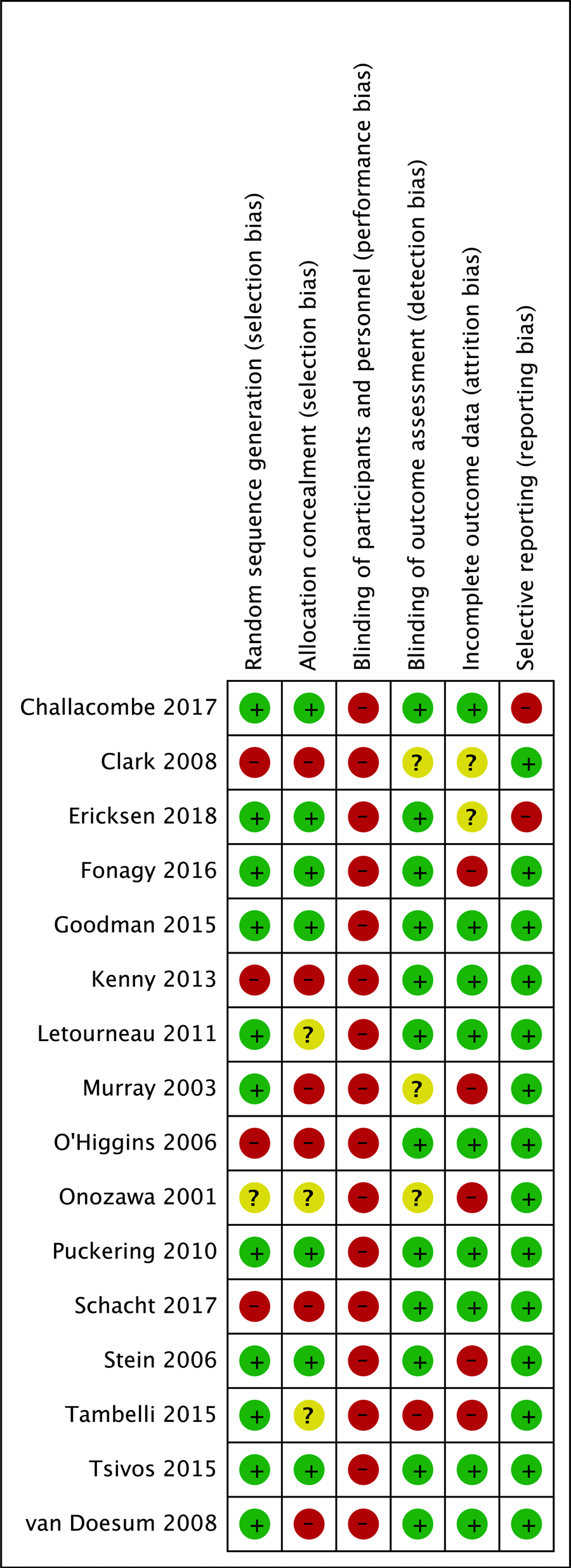

Figure 2 presents an overview of the quality of included studies. Twelve of the sixteen included studies reported the use of a RCT design (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017; Ericksen et al., Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018; Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015; Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003; Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; Tambelli et al., Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015; Tsivos et al., Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008), although four of these studies did not include adequate concealment of the allocation process in their design (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003; Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; Tambelli et al., Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015). Trials of psychological therapies are by nature at high risk of bias because it is not usually possible to blind participants and personnel to the nature of the intervention delivered (Skapinakis et al., Reference Skapinakis, Caldwell, Hollingworth, Bryden, Fineberg, Salkovskis and Lewis2016), which can result in performance bias or the placebo effect due to participants awareness of being allocated to the active treatment, as opposed to the control group. In addition, the included studied had high rates of attrition.

Figure 2. Chart displaying risk of bias per outcome for each included studies. + symbol denotes low risk of bias, - symbol denotes high risk of bias, anddenotes unclear risk of bias.

Study outcomes

Table 1 gives a brief summary of the interventions used in the included studies.

Interventions were classified into three groups:

-

Group A: Interventions demonstrating statistically significant improvements in infant or mother–infant outcomes.

-

Group B: Interventions demonstrating directional improvements in infant or mother–infant outcomes but the improvements did not reach statistical significance.

-

Group C: Interventions that did not identify improvements to infant or mother–infant outcomes.

Group A

The following studies all identified significant improvements in infant or mother–infant relationship outcomes: four studies using video feedback to guide positive Mother×Infant interactions (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008 and Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006), an infant massage study (Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001), a study of a mother–infant group therapy model (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008), and Puckering et al. (Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010), which evaluated the Mellow Babies group intervention. In addition, one arm of the Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) study, in which both parents received a supportive, relationship-based, parent–infant intervention aiming to promote positive Parent×Infant interactions, showed significant improvements. However, the arm in which only the mother received treatment showed no significant improvements.

The four video feedback studies used different outcome measures to assess the impact of the interventions on the infants and the mother–infant relationship. Schacht et al. (Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017) used Ainsworth's strange situation procedure (SSP; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) and found that significantly more infants in the intervention group were classed as securely attached at 15 months compared with the control group. Kenny et al. (Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013) used the CARE index (Crittenden, Reference Crittenden2003) and found that following the video feedback intervention there were significant improvements in the domains of maternal sensitivity and maternal unresponsiveness, while infants were significantly more cooperative and significantly less passive. Kenny et al. (Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013) was the only study included in this review to report infant outcomes as a function of maternal diagnoses, stratifying study participants according to three diagnostic groups: depression, schizophrenia, and mania. However, the study did not identify any significant effect of diagnostic group on the included outcomes, reporting similar significant improvements in the above domains across all three groups (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013). Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006) used scales developed specifically for their own study, and identified significant improvements in rates of marked or severe mealtime conflict for the video feedback group, compared to the supportive counselling control group, as well as a significant improvement in infant autonomy. van Doesum et al. (Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008) made use of the Emotional Availability Scales (EAS; Biringen, Robinson, & Emde, Reference Biringen, Robinson and Emde1998), identifying significant improvements in maternal sensitivity and structuring, and infant responsiveness and involvement. The attachment assessment, conducted using the Attachment Q-Sort (AQS; Waters & Deane, Reference Waters and Deane1985), found that infants in the experimental group had significantly higher scores for attachment security than the control group (van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008).

Onozawa et al. (Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001) reported outcomes using the Fiori Global Rating system for video assessment of Mother×Infant interaction quality (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper and Cooper1996), and found statistically significant improvements in the massage group compared to baseline, with no improvement seen in the support group used as a control. Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008) identified a statistically significant improvement using the Parent–Child Early Relationship Assessment (PCERA) scale (Clark, Reference Clark1985), indicating that mothers exhibited significantly more positive affective involvement (including: maternal warmth, pleasure in her child, eye contact, and mirroring of the infant's internal state [Clark, Reference Clark1999]) than the waitlist control group at 12 weeks. Puckering et al. (Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010) assessed outcomes via their own video coding system developed for this trial. Dyads taking part in the intervention were showed a statistically significant improvement in positive interactions, and a reduction in negative interactions. Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) used two Italian outcome measures, with the QUIT questionnaire (Axia, Reference Axia2002) assessing ratings of perceived infant behavior and demonstrating significant time effects across all treatment and control groups in the QUIT domains of social orientation, motor activity, negative emotionality and attention. The SVIA (Lucarelli et al., Reference Lucarelli, Cimino, Perucchini, Speranza, Ammaniti and Ercolani2002), an adaptation of the Infant Feeding Scale, found that for the mother and father treatment group only, there was a significant improvement compared to the other groups and across time, and it is this treatment group that has been included in Group A.

The quality of the Group A studies was largely poor (see Figure 2), with five of these studies reporting use of an RCT design (Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; Tambelli et al., Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008), but only two studies including both adequate randomization and allocation concealment (Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006).

Group B

Studies reporting directional improvements in infant or mother–infant relationship outcomes but which did not demonstrate statistical significance, included the infant massage study by O'Higgins (Reference O'Higgins2006), all three treatment arms of Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) (investigating cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT], psychodynamic therapy and nondirective counselling), a study of a parent–infant psychotherapy program (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016) and the study of the Baby Triple P program (Tsivos et al., Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015).

O'Higgins (Reference O'Higgins2006) assessed outcomes using the same Fiori Global Rating system as used by Onozawa et al. (Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001). This study found no significant difference in Mother×Infant interaction quality between study groups at each outcome assessment point; however, it is notable that O'Higgins (Reference O'Higgins2006) found no difference at baseline interaction quality between the depressed study groups (massage and support groups) and the healthy control group. O'Higgins (Reference O'Higgins2006) cited a possible “ceiling effect” of investigating mothers with mental health problems that had normal baseline interaction quality as a confounder of their results. Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) saw a significant improvement in maternally reported infant outcomes, using a checklist devised specifically for the study, regarding infant behavior at 4.5 months for all three intervention groups and at 18 months for the CBT group alone. Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) also assessed attachment via Ainsworth's SSP (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) but found no significant differences in attachment status between study groups.

Fonagy et al. (Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016) used the Bayley Mental Development Index (MDI) score (Bayley, Reference Bayley2006), and identified a marginal effect of time on the cognitive scale for both intervention and control groups, indicating a small, nonsignificant improvement in cognitive development between time points for the infants included in the study, but found no difference in development according to treatment group. Fonagy et al. (Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016) also identified a greater proportion of securely attached infants as assessed via Ainsworth's SSP (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) at 12 months of infant age, but this was not statistically significant. Tsivos et al. (Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015) assessed outcomes with the postpartum bonding questionnaire (PBQ; Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Oates, George, Turner, Vostanis, Sullivan and Murdoch2001) and the CARE Index (Crittenden, Reference Crittenden2003). The study identified nonsignificant improvements across various domains in each of these, but found no statistically significant results.

The quality of studies included in Group B was mixed (see Figure 2), including three RCTs (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003; Tsivos et al., Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015). Tsivos et al. (Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015) was one of the higher quality papers included in this review, failing the Risk of Bias assessment only on the blinding of participants and personnel domain; however, with a sample size of only 27 participants, the authors of this pilot RCT themselves acknowledged the need for a larger scale study.

Group C

Studies reporting no significant improvements to infant or mother–infant relationship outcomes were: the mothers-only treatment group of Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) the time-intensive CBT intervention evaluated by Challacombe et al. (Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017) the peer support home-visiting intervention studied by Letourneau et al. (Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011) the study of the “Community HUGS” therapeutic playgroup (Ericksen et al., Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018) and the perinatal dyadic psychotherapy intervention evaluated by Goodman et al. (Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015).

As discussed in Group A, Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) found some significant improvements for the infants in the QUIT questionnaire (Axia, Reference Axia2002) domains of social orientation, motor activity, negative emotionality and attention, across all treatment groups. However, this improvement was found to be an effect of time rather than intervention. There were no significant treatment effects using either the SVIA (Lucarelli et al., Reference Lucarelli, Cimino, Perucchini, Speranza, Ammaniti and Ercolani2002) or the QUIT (Axia, Reference Axia2002) for the mothers-only treatment group. Challacombe et al. (Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017) assessed outcomes using the Ainsworth SSP (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) and Bates’ Infant Characteristic Questionnaire (ICQ; Bates, Freeland, & Lounsbury, Reference Bates, Freeland and Lounsbury1979), reporting no significant treatment effects.

Letourneau et al. (Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011) assessed outcomes using the Nursing Child Assessment Satellite Training (NCAST) feeding and teaching scales (Sumner & Spietz, Reference Sumner and Spietz1994a, Reference Sumner and Spietz1994b), Bayley's MDI (Bayley, Reference Bayley2006), Bates’ ICQ (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Freeland and Lounsbury1979) and maternal and infant salivary cortisol. The ICQ indicated a highly statistically significant time effect in both the intervention and the control groups, demonstrating that mothers in the study tended to view their infants as less difficult over time. There was a statistically significant moderate effect size in favor of the control group seen in the NCAST teaching scales; however, there were no other significant results found.

Ericksen et al. (Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018) used the Paediatric Infant Parent Exam (PIPE; Fiese, Poehlmann, Irwin, Gordon, & Curry-Bleggi, Reference Fiese, Poehlmann, Irwin, Gordon and Curry-Bleggi2001) to evaluate Mother×Infant interaction quality, finding no significant differences between treatment groups at follow up. Ericksen et al. (Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018) also used the Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, Flens, & Austin, Reference Abidin, Flens and Austin2006). This found no significant posttreatment differences between groups, apart from on the difficult child domain, which remained higher in the intervention group than control, opposite to the intended treatment effect (Ericksen et al., Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018). Goodman et al. (Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015) also used the PSI-SF (Abidin et al., Reference Abidin, Flens and Austin2006), reporting no improvements in the treatment group. This study also assessed, with no treatment effect noted, was maternal sensitivity, infant engagement, and dyadic reciprocity, using these domains of the Coding Infant Behaviors (CIB; Feldman, Reference Feldman1998) video-assessment scales (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015).

The quality of studies included in Group C was also mixed (see Figure 2), although it is notable that they were all RCTs. Group C included the only two studies of this review with elements of reporting bias (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017; Ericksen et al., Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018).

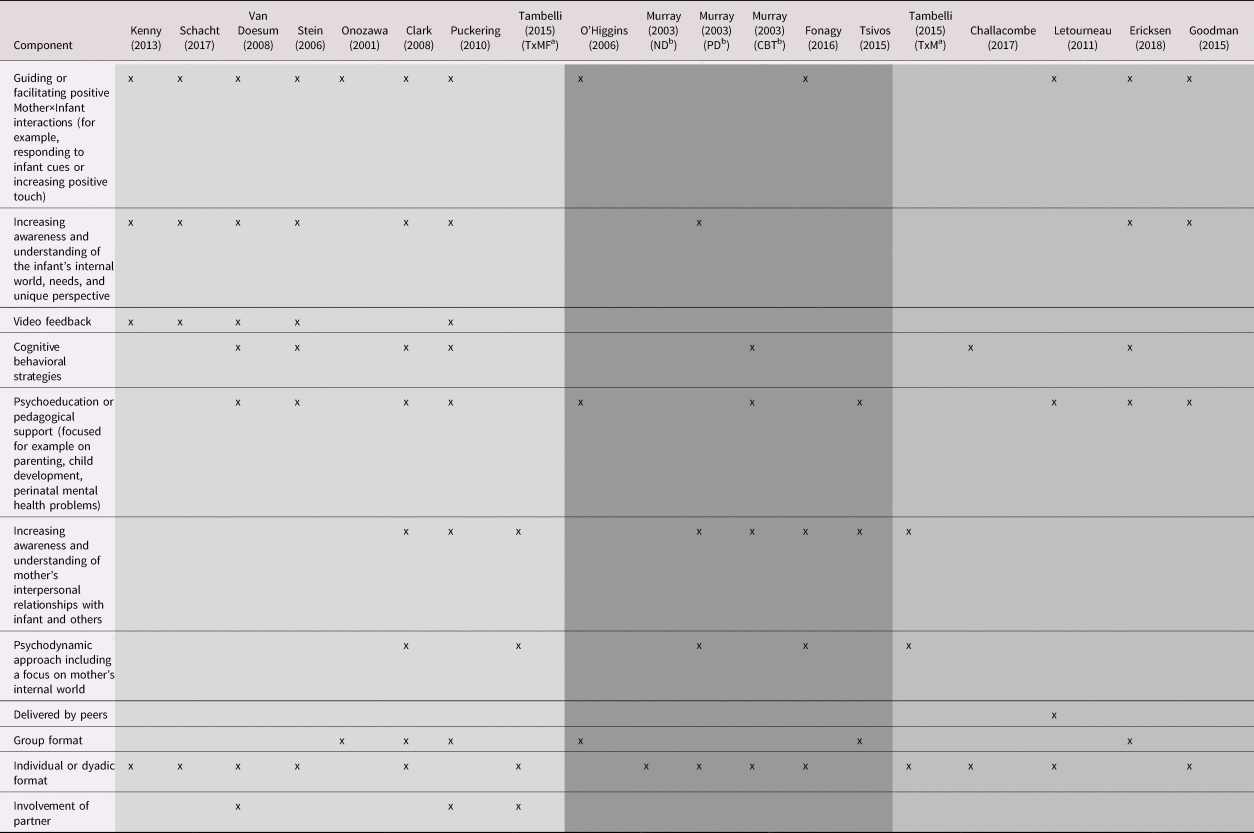

Key components

In addition to classifying the interventions into three groups according to their impact on infant or mother–infant relationship outcomes, the descriptions of the interventions were also analyzed to identify key components. A matrix was then created, mapping the key components of the studies against the study results (See Table 2). The components identified and their prevalence in the different groups are discussed below.

Table 2. Analysis of components of potentially effective interventions

Key:

Group A: Interventions demonstrating statistically significant improvements in infant or mother–infant outcomes.

Group B: Interventions demonstrating directional improvements in infant or mother–infant outcomes but the improvements did not reach statistical significance.

Group C: Interventions demonstrating statistically significant improvements in infant or mother–infant outcomes.

a Tambelli 2015 examined the impact of psychodynamic therapy delivered to either both parents (TxMF), or to the mother alone (TxM), compared to a control. These groups have been reported on separately due to their different findings.

b Murray 2003 examined three different approaches to maternal psychotherapy, with an additional routine care control group. The three treatment groups have been reported on separately in the below table to reflect their differing approaches. ND = nondirective counselling, PD = psychodynamic therapy, CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy.

Component 1: Guiding and facilitating positive Mother×Infant interactions

Of the eight interventions in Group A, seven had facilitation of positive Mother×Infant interactions as a key component (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008; Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). Techniques included interaction guidance or coaching to increase sensitivity to infant cues, and infant massage to encourage increased use of positive touch.

Guiding of maternal interactions was a key component of many interventions in Group A, but was also featured in some interventions in Groups B and C. In these groups the guidance appeared less likely to be a core component.

Guiding and facilitating positive Mother×Infant interactions is the main focus of infant massage interventions. Two studies were included in this review that investigated infant massage; however, they found conflicting results (O'Higgins, Reference O'Higgins2006; Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001). Onozawa et al. (Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001) reported statistically significant improvements in interaction quality for mother–infant dyads in the infant massage group compared to the control, while O'Higgins (Reference O'Higgins2006) noted no such improvement, although this may have been due to the cited “ceiling effect,” as there was no difference at baseline in interaction quality between the depressed study groups and the healthy control group (O'Higgins, Reference O'Higgins2006).

Component 2: Helping the mother to understand the infant's internal world, needs, and unique perspective

Six of the interventions in Group A aimed to help the mother understand her infant's internal world and unique perspective, with increased awareness of the infant's needs (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008; Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). For example, Schacht et al. (Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017) trialed a “mind-mindedness” focused intervention designed to encourage mothers to comment on their infants internal thoughts, feelings and states. The study found that significantly more infants in the intervention group were classed as securely attached at 15 months compared with the control group (p = .008) (Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017).

Other interventions in Group A that shared this focus included another four that made use of video feedback (discussed further below) to aid interaction guidance and improve maternal sensitivity to the infant's needs and perspective (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). In addition, Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008) investigated the use of a mother–infant therapy group that identified a statistically significant improvement in maternal positive affective involvement compared to the waitlist control group, as well as a significant main effect seen on mother's perception of how her infant reinforces positive interactions (PSI) “child reinforces” domain, p < .05) indicating that mothers in the treatment group found parenting their infants to be more rewarding compared to those in control group (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008).

There were less successful interventions, in terms of infant or mother infant relationship outcomes, that shared this focus. These included the psychodynamic therapy treatment group from Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) and the dyadic psychotherapy approach investigated by Goodman et al. (Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015). In addition, Ericksen et al. (Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018) included a focus on the infant's internal world as part of their therapeutic playgroup program (CHUGS). No significant posttreatment differences were identified in the CHUGS pilot RCT between intervention and the waitlist control groups, apart from in the average scores on the difficult child domain of the PSI, which remained higher in the intervention group, a statistically significant difference (p = .01) in the opposite direction to hypothesized. Mother–infant relationship outcomes had shown significant improvements in the feasibility study of CHUGS; however, due to the lack of control group the feasibility results have not been included in this review.

Component 3: Use of video feedback

Five of the interventions in Group A used videos of Mother×Infant interactions as a prompt for discussions with mothers focusing on moments of attunement and sensitivity to infant cues (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008), and sometimes also highlighting missed opportunities for positive interactions (van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008).

Four interventions (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008) had video feedback discussions as a core component, of which two were delivered within inpatient perinatal mental health services in MBUs (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017), and two within the community in the mothers’ homes (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). Although video feedback is highlighted as a core component of these interventions, it should be clarified that the selection of interactions to highlight and discuss is the critical factor, rather than the use of video per se. All of the video feedback interventions included in this review focused on highlighting and reinforcing attuned maternal responses and maternal sensitivity (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). In the case of Schacht et al. (Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017), one particular kind of attuned maternal response (“mind-minded” comments relating to internal states) was the sole focus of the intervention.

Puckering et al. (Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010) investigated a multicomponent group program that included an element of video feedback. The intervention comprised a weekly group with dyadic and individual components, involving many of the key components identified in Table 2. Dyads taking part in the intervention showed a statistically significant improvement in positive interactions (p = .015), and nonsignificant reduction in negative interactions (Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010).

Component 4: Cognitive behavioral strategies

Four studies from Group A included some use of cognitive behavioral strategies; however, this was not a core component of any of these interventions. One study in Group B had maternal CBT as a core component. Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) evaluated CBT in one arm of their study (the other arms being psychodynamic psychotherapy and nondirective counselling for mothers with PND, each of which are considered separately in this analysis). Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) identified scarce improvements for the CBT arm, with the exception of a significant improvement in maternal perception of relationship problems at 4.5 months that was seen for all three interventions trialed, all other outcomes and time points found no significant differences. A further study (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017) investigating the effects of iCBT (time-intensive CBT) in new mothers with OCD was classified into Group C and found no treatment effect for infant attachment or Mother×Infant interaction quality (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017).

Component 5: Psychoeducation/pedagogical support

Just over half of the interventions trialed involved some element of psychoeducation or pedagogical support (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008; Ericksen et al., Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015; Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; O'Higgins, Reference O'Higgins2006; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; Tsivos et al., Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). For some, such as the peer support intervention delivered in Letourneau et al. (Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011), this was a key focus. For others, such as Puckering et al. (Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010), Tsivos et al. (Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015) or Ericksen et al. (Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018), this was just one component of a complex, multi-focused intervention program. The use of psychoeducation or pedagogical support was seen in interventions spread across Groups A, B, and C, and so its association with improvements in infant or mother–infant relationship outcomes is unclear.

Component 6: Exploration and understanding of interpersonal relationships with infant and others

Exploring and understanding the mother's interpersonal relationships either with their infant, or with other individuals, was also identified as a core component in a number of interventions. Interventions from Group A that reported this focus were: the mother–infant therapy group model explored in Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008); the Mellow Babies multicomponent group intervention in Puckering et al. (Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010); and the arm of the Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) study in which both parents received a supportive, relationship-based, parent–infant intervention in the first year of infant life. Significant results found by Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) included improvements in the domains of motor activity, attention capacity, social orientation, and negative emotionality. They also found that parental interactions with the infant were significantly less maladaptive in this treatment group at follow up. Neither of these treatment effects were seen for the mothers-only treatment group, which is why this arm of the study has been placed in Group C (Tambelli et al., Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015).

Other studies which had a focus on exploring the mother's interpersonal relationships included three from Group B: Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003), Tsivos et al. (Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015) and Fonagy et al. (Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016). Tsivos et al. (Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015) investigated the Baby Positive Parenting Program (Triple P), a multicomponent intervention that focuses on maternal strengths in parenting, aiming to promote healthy infant development and improve maternal psychopathology symptoms by educating parents and encouraging a low-conflict environment for the infant. The study identified nonsignificant improvements across various outcomes, but found no statistically significant results. Only one intervention from the Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) paper included this component, and this was their investigation of maternal psychodynamic psychotherapy. This intervention was placed in Group B because, apart from the improvement in maternal perception of relationship problems seen at 4.5 months for all three interventions trialed in the paper, the psychodynamic therapy group saw no other statistically significant improvements.

Fonagy et al. (Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016) investigated a parent–infant psychotherapy (PIP) that took a psychoanalytic approach. They identified a small, nonsignificant improvement (p = .07) in the cognitive development subscale of their primary outcome measure and also found that a greater proportion of infants in the treatment group were securely attached at 12 months of infant age, but this was not statistically significant (p = .61) (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016). In addition, mothers in the PIP group reported lower overall levels of parenting stress over time relative to the mothers in the control group (p = .018) but no other treatment effects were identified (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016).

Component 7: Psychodynamic

Four studies investigated the use of psychodynamic therapy: Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008), Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015), Fonagy et al. (Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016) and Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003). Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008) and the mother and father treatment group of Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) were the only two psychodynamic interventions placed in Group A. The psychodynamic treatment arm of Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) and the psychoanalytic PIP intervention investigated by Fonagy et al. (Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016) were both associated with only directional, but not statistically significant improvements, as mentioned above, while the mothers-only group from Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) was associated with no treatment effects.

Component 8: Mode of delivery

In addition to analyzing the interventions according to their key components, we also considered the mode of delivery used. As can be seen in Table 2, group and individual delivery were spread across Groups A, B, and C. Most studies were delivered by trained professionals, with the exception of one study (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011), which investigated an intervention delivered by peers. This study identified no significant improvements in the treatment group when compared to control, instead they reported a statistically significant (p = .05) change in favor of the control group seen in the Teaching scale of the NCAST assessment, suggesting that the intervention was associated with worsened interaction quality between mother and infant during the teaching situations assessed (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011). However, with only one study investigating peer delivery, no significant conclusions can be drawn.

Of note, three studies included some involvement of the infants’ fathers in their interventions, and all of these reported significant improvements. The degree of involvement varied. Tambelli et al. (Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015) found significant results for the use of psychodynamic treatment in the first year of infant life, but only when this was delivered to both the mother and the father. The Mellow Babies intervention from Puckering et al. (Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010) involved the fathers by inviting them to group sessions that delivered psychoeducation on PND and included activities focused on strengthening Father×Infant interactions. van Doesum et al. (Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008) was the only paper to describe involving the father and mother together in their intervention; they described how the fathers were involved in reviewing the mother and infant's videotaped interactions as part of the video feedback sessions, although this was only when the father was available rather than a consistent feature of the intervention.

Discussion

The link between perinatal mental health difficulties and adverse outcomes for the child from infancy through to adulthood is well established (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009; Hosman et al., Reference Hosman, van Doesum and van Santvoort2009; Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, Smailes, & Brook, Reference Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, Smailes and Brook2001; Korhonen et al., Reference Korhonen, Luoma, Salmelin and Tamminen2012; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper and Cooper1996; Netsi et al., Reference Netsi, Pearson, Murray and Cooper2018; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014; van Doesum & Hosman, Reference van Doesum and Hosman2009; Velders et al., Reference Velders, Dieleman, Henrichs, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2011; Wan & Green, Reference Wan and Green2009). We undertook a review of interventions to support mothers with mental health difficulties that were designed to improve infant outcomes and mother–infant relationship outcomes in the first year postpartum, with no restriction on maternal diagnosis (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn and Juffer2003; Leman et al., Reference Leman, Bremner, Parke and Gauvain2012; Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic and Linder2017; Wright & Edginton, Reference Wright and Edginton2016). The 16 systematically identified included studies varied in terms of the content of the interventions, duration of intervention, specific perinatal mental health difficulties, and outcome measures. The resulting heterogeneity due to differences in participant diagnoses, study methods, and outcome measures meant that meta-analysis was not possible and therefore analysis of effectiveness was limited to reporting from the original studies. However, the key components of the diverse interventions highlight which of the particular elements may be associated with significant improvements in infant or mother–infant relationship outcomes. The analysis we undertook was a pragmatic attempt to identify the “active ingredients” that will help guide the planning of future interventions.

The aim of the review was to inform the design and implementation of parenting pathways within perinatal mental healthcare services, and as such the focus was specifically on infant and mother–infant relationship outcomes. The importance, however, for both mother and infant, of good maternal mental health is also paramount but has been considered elsewhere (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, McMillan, Kirkpatrick, Ghate, Barnes, Smith and Smith2010, Reference Barlow, Bennett, Midgley, Larkin and Wei2015; Dennis, Ross, & Grigoriadis, Reference Dennis, Ross and Grigoriadis2007).

This review indicated that interventions that focus on facilitating or guiding Mother×Infant interactions and maternal behavior, and interventions that focus on helping the mother to understand the child's internal world, were linked with significant improvements in infant or mother–infant outcomes (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008; Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; Tambelli et al., Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). Five studies were identified that included the use of video feedback, all of which produced significant improvements in infant outcomes or mother–infant relationship outcomes (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). Two community-based studies were RCTs of relatively high quality (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008), while those conducted in an MBU used nonrandomized designs and thus scored less well in the risk of bias assessment (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017). However, the inpatient studies of video feedback interventions demonstrated the most robust positive findings of the entire review.

Significant change was also reported in studies that addressed mothers’ understanding of their infant's internal world. Four of the video feedback intervention studies included a focus on this (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008), in addition to the mother–infant therapy group model described in Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008) and the Mellow Babies intervention investigated in Puckering et al. (Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010).

Strengths and limitations

This review employed a comprehensive search strategy that identified over 7,000 unique citations. The search was broad, including nine relevant bibliographic databases covering medical, nursing, and social science disciplines, consistent with previous literature on a similar topic (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, McMillan, Kirkpatrick, Ghate, Barnes, Smith and Smith2010). The diverse approaches of the included papers allowed this review to encompass a full range of perinatal mental health difficulties, and to examine different forms of interventions designed to improve infant outcomes. Final study selection and data extraction for the review was completed according to good practice in systematic reviews, involving double-scoring from two researchers to ensure accuracy and consistency; however, titles and abstracts were assessed by one reviewer only.

Time constraints limited the use of supplementary literature searching beyond the electronic databases searches. Citation and reference-list searching was performed; however, contacting of authors and hand searching of relevant journals was not. In addition, searches and inclusion of studies were limited to those published in the English language, possibly introducing an element of publication bias.

Heterogeneity of the studies in terms of methods and the variety of outcome measures used, limited this review. The included studies used 34 different outcome measures, frequently assessing similar outcomes but using different methods. This prevented the use of meta-analytical techniques to synthesize data and compare the results of the included studies. Furthermore, many of the studies involved complex, multifaceted intervention programms with different formats, which meant it was not possible to group studies according to intervention type. The interventions under investigation in the included studies varied in their timescales and there remains uncertainty therefore as to how timescale may potentially impact effectiveness, with previous research suggesting that briefer interventions may be more effective(Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn and Juffer2003).The analysis we therefore undertook was a pragmatic attempt to identify the key components of the most effective interventions. We constructed a matrix (shown in Table 2) to facilitate the analysis, our hope being that identifying the “active ingredients” will help guide the planning of future interventions.

Twelve of the included studies were described as RCTs (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017; Ericksen et al., Reference Ericksen, Loughlin, Holt and Gemmill2018; Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Sleed and Baradon2016; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Prager, Goldstein and Freeman2015; Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003;Onozawa et al., Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001; Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Woolley, Senior, Hertzmann, Lovel, Lee and Fairburn2006; Tambelli et al., Reference Tambelli, Cerniglia, Cimino and Ballarotto2015; Tsivos et al., Reference Tsivos, Calam, Sanders and Wittkowski2015; van Doesum et al., Reference van Doesum, Riksen-Walraven, Hosman and Hoefnagels2008). The majority of these used computer-generated randomization, although some less robust methods were used including the researcher choosing a colored ball (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003) or tossing a coin (Puckering et al., Reference Puckering, Mcintosh, Hickey and Longford2010), introducing significant opportunity for selection bias given the researcher was aware of the implication of which color/coin result was linked to which allocation. Four studies made no attempt at randomization (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tluczek and Brown2008; Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013; O'Higgins, Reference O'Higgins2006; Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017). All included studies were deemed to be at high risk of performance bias due to a lack of blinding of participants and personnel. This was likely due to the impracticality of attempting to blind participants when the interventions under investigation varied so greatly (O'Higgins, Reference O'Higgins2006). Blinding is challenging in the field of psychological research, and in the case of waitlist controls it can be impossible, which opens these studies to an increased risk of performance bias (Skapinakis et al., Reference Skapinakis, Caldwell, Hollingworth, Bryden, Fineberg, Salkovskis and Lewis2016) and in the case of studies with waitlist control groups, the placebo effect.

In trials of psychological therapies, researcher allegiance is often prevalent with the primary author of the studies frequently being a proponent, or even the psychotherapist in the active treatment arm (for example, Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2017). Some studies also fail to disclose or discuss details on the psychotherapist(s) that delivered the intervention (for example, Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Meins, Fernyhough, Centifanti, Bureau and Pawlby2017). The statistical analyses for the study may also be undertaken by the practicing psychotherapist (for example, Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Conroy, Pariante, Seneviratne and Pawlby2013). The included studies were often describing pilot interventions developed by the study authors and therefore the conception of study design, delivery, interpretation, and reporting of such studies are prone to selection, detection, and reporting bias. This review's reliance on the reported statistical benefits of these emerging interventions without further formal validation with high-quality, adequately powered trials means that these findings must therefore be interpreted with caution.

Implications for practice

Given the strong association between a mother's mental health and child outcomes (Hosman et al., Reference Hosman, van Doesum and van Santvoort2009; Netsi et al., Reference Netsi, Pearson, Murray and Cooper2018; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014), it is essential that perinatal mental health services continue to deliver well-researched evidence-based interventions to support and improve the mental health of mothers experiencing complex perinatal mental health problems. However, it is also imperative that perinatal services deliver interventions that support Infant×Mother interactions which affect infant and mother–infant outcomes. Guidance produced in the UK states that parent–infant services are an important part of a perinatal mental healthcare strategy, and should consist of “a variety of psychotherapeutic, psychological and psychosocial treatments and parenting interventions” (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2015), a recommendation that is mirrored in the focus on treating mother and infant together in the World Health Organisation's “Thinking Healthy” guidelines for treatment of perinatal depression (World Health Organization, 2015). This review highlights that future investment in parenting interventions should include a focus on guiding maternal behavior and interactions with her infant, and increasing mothers’ understanding of their infant's internal world. The use of video feedback in guiding attuned and sensitive interaction demonstrated the most robust evidence, and the greatest success for this was seen in an inpatient MBU setting. There was also promising evidence for the involvement of fathers in perinatal mental health interventions.

Implications for future research

The present review has highlighted a lack of high-quality, RCTs investigating the effectiveness of different perinatal interventions on infant outcomes. While 16 studies were identified and included in this review, due to the variety of interventions assessed there were only a small number of studies for each form of intervention. In addition, the studies in this review often assessed infant attachment and other outcomes in tandem with assessments of the mother–infant relationship or maternal sensitivity, with only one study following the infants up later in childhood (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2003, followed participants up to 5 years of age). It is thought that this may underestimate the treatment effect of parenting interventions, as the change in the relationship or maternal sensitivity has not had time to significantly impact the infant (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn and Juffer2003). Previous research has also highlighted that attachment security and other infant outcomes are more difficult to change than maternal outcomes, likely due to the long-term nature of such changes (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn and Juffer2003). This review has purposefully included studies that investigated interventions conducted in the first year of infant life, to maintain focus on perinatal mental health problems; however, the lack of long-term follow up in these studies means that the potential to capture the long-term benefits of the interventions has not been evidenced. Therefore, rigorous controlled studies are needed for different types of intervention, ideally with a focus on infant and mother–infant relationship outcomes with long-term follow up into childhood and later life.

Further controlled studies of infant massage are also needed to clarify the conflicting results found by Onozawa et al. (Reference Onozawa, Glover, Adams, Modi and Kumar2001) and O'Higgins (Reference O'Higgins2006). In addition, three included studies involved fathers in varying degrees and all reported significant improvements. Previous reviews have highlighted the potential positive impact of engaging fathers in perinatal mental health interventions; however, there is a lack of robust evidence for the impact of this on infant outcomes specifically (Panter-Brick et al., Reference Panter-Brick, Burgess, Eggerman, McAllister, Pruett and Leckman2014; Rominov, Pilkington, Giallo, & Whelan, Reference Rominov, Pilkington, Giallo and Whelan2016).

Future research into perinatal interventions should ensure sufficient attention is given to infant and mother–infant relationship outcomes, rather than focusing solely on evaluating maternal outcomes. In addition selection and pre-specification of such infant outcome measures should be considered in future primary studies of perinatal health so that more robust conclusions regarding their effectiveness in improving infant wellbeing, mental health, and development can be drawn from future systematic reviews.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001340.

Financial Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or non-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

This study was a systematic review of literature related to the review subject and did not involve participation of human subjects or the use of secondary data. Thus, ethical approval was neither required nor sought.