Child maltreatment (CM) remains a signficant problem in the United States, with dire consequences for children's developmental competencies, particularly socioemotional and relational outcomes (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009; Toth, Gravener-Davis, Guild, & Cicchetti, Reference Toth, Gravener-Davis, Guild and Cicchetti2013). Parenting interventions such as Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) have been shown to improve positive, responsive parenting and lower risk for CM, including among families for whom CM has already been documented (Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Silovsky, Funderburk, Valle, Brestan, Balachova and Bonner2004; Lieneman, Brabson, Highlander, Wallace, & McNeil, Reference Lieneman, Brabson, Highlander, Wallace and McNeil2017). Though PCIT is particularly effective among child welfare-involved families who engage in treatment, many such families are reluctant to engage in child and family interventions, and thus decline to enter treatment or drop out early (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Phillips, Wagner, Barth, Kolko, Campbell and Landsverk2004). As such, understanding the potentially modifiable risk factors for child welfare-involved families’ treatment engagement and attrition is crucial for addressing CM as a public health concern. Modifiable risk factors for the perpetration of CM include deficits in self-control and emotion regulation, greater attunement to threat-related cues, and holding negative, threat-sensitive attributions of children (Bugental, Reference Bugental1987; Reference Bugental and Sameroff2009; Skowron & Woehrle, Reference Skowron, Woehrle, Fouad, Carter and Subich2012). These characteristics in turn have been associated with deficits in sensitive, effective parenting strategies (e.g., Sturge-Apple, Davies, Cicchetti, & Fittoria, Reference Sturge-Apple, Davies, Cicchetti and Fittoria2014). In this study, we sought to examine whether these modifiable parental risk factors (e.g., self-regulation, social cognitions) also predicted persistence and dropout in PCIT among child welfare-involved families, and further examined whether there are distinct predictors of engagement in and persistence through key stages of PCIT.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

PCIT is an active, directive behavioral parenting intervention wherein parents practice the behaviors taught in the intervention with their child during sessions. PCIT uses a unique “bug-in-the-ear” method where parents receive live coaching from a trained therapist to improve their parenting in real time. PCIT is divided into two phases – child-directed interaction (CDI) and parent-directed interaction (PDI). Phases are delivered sequentially, and each phase begins with a teaching session where parents learn and practice new parenting techniques, followed by several coaching sessions during which the parent receives live therapist support while practicing new skills with their child (Eyberg, Reference Eyberg1988; Eyberg & Funderburk, Reference Eyberg and Funderburk2011; Funderburk & Eyberg, Reference Funderburk, Eyberg, Norcross, VandenBos and Freedheim2010; Herschell & McNeil, Reference Herschell, McNeil, Briesmeister and Schaefer2005). Further, coaching focus in PCIT is guided by observation of parents’ developing skills, informed by brief coding at the outset of each weekly session.

The CDI phase of treatment focuses on strengthening warm, positive relationships between parents and children. Parents are taught to: (a) use positive parenting (i.e., PRIDE) skills consisting of specific labeled praises for positive child behavior (e.g., “Great job picking up the toys!”), reflection of the child's speech and behavior, imitation, behavioral descriptions (e.g., “You're stacking the blocks on top of each other”), and demonstrating enjoyment of time spent together; (b) follow their child's lead in the play; and (c) avoid use of “Don't skills” that include negative talk/criticism and parent directives during the play. In the PDI phase of treatment, parents learn safe, effective child behavior management strategies that center around giving simple, developmentally appropriate, direct commands (e.g., “Please sit down on your chair”) instead of commands that focus on what not to do (e.g., “Cut it out!”) or that take the form of indirect suggestions for how to behave (e.g., “Do you want to sit down now?”). Parents are then coached to follow through with either praise for child compliance (e.g., “Great job listening!”) or a safe and consistent time-out procedure for noncompliance. These child behavior management skills are designed to replace harsh or inconsistent forms of discipline often observed among families with histories of child maltreatment.

PCIT is particularly well suited for families with a history of CM (Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Silovsky, Funderburk, Valle, Brestan, Balachova and Bonner2004; see meta-analyses by Euser, Alink, Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, Reference Euser, Alink, Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2015; Kennedy, Kim, Tripodi, Brown, & Gowdy, Reference Kennedy, Kim, Tripodi, Brown and Gowdy2016). Maltreating parents may resort to physical punishment during episodes of discipline as a consequence of escalating coercive behavior between parent and child (Herschell & McNeil, Reference Herschell, McNeil, Briesmeister and Schaefer2005; Patterson, Reference Patterson, Reid, Patterson and Snyder2002). Implementing the skills taught in PCIT helps to disrupt coercive cycles and reduce harsh, aversive parenting by providing caregivers with alternative, nonviolent discipline strategies (e.g., Hakman, Chaffin, Funderburk, & Silovsky, Reference Hakman, Chaffin, Funderburk and Silovsky2009). PCIT enables caregivers to effectively discipline their child while avoiding use of harsh punishment. However, development of positive parenting skills and safe, effective child behavior management skills is likely aided by certain competencies, such as regulating negative arousal in stressful disciplinary contexts and inhibiting the tendency to “give in” to child aversive behavior (Skowron & Funderburk, Reference Skowron and Funderburkunder review).

Predictors of attrition in family-based interventions

PCIT is effective when families engage, but as is the case for family-based interventions in general and with high-risk families in particular, attrition rates are high (Danko, Garbacz, & Budd, Reference Danko, Garbacz and Budd2016). On average, studies of family-based interventions report estimates of 40%–60% attrition (Prinz & Miller, Reference Prinz and Miller1994; Reyno & McGrath, Reference Reyno and McGrath2006; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, Reference Wierzbicki and Pekarik1993). Comparatively, reports of attrition rates in PCIT range from 18% to 74.5% (Eyberg et al., Reference Eyberg, Funderburk, Hembree-Kigin, McNeil, Querido and Hood2001; Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, Reference Eyberg, Boggs and Algina1995; Fernandez & Eyberg, Reference Fernandez and Eyberg2009; Lieneman, Quetsch, Theodorou, Newton, & McNeil, Reference Lieneman, Quetsch, Theodorou, Newton and McNeil2019; Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson, & Touyz, Reference Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson and Touyz2003, Reference Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson and Touyz2004; Schuhmann, Foote, Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, Reference Schuhmann, Foote, Eyberg, Boggs and Algina1998). Sociodemographic factors are among the most common barriers to treatment retention in family-focused interventions (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin1996; Kazdin, Mazurick, & Bass, Reference Kazdin, Mazurick and Bass1993), including educational attainment, single parenthood, and income (Danko et al., Reference Danko, Garbacz and Budd2016; Fernandez & Eyberg, Reference Fernandez and Eyberg2009; Gross, Belcher, Budhathoki, Ofonedu, & Uveges, Reference Gross, Belcher, Budhathoki, Ofonedu and Uveges2018). Family-centered therapies also must contend with accessibility issues (Comer et al., Reference Comer, Furr, Miguel, Cooper-Vince, Carpenter, Elkins and Chase2017), and parent factors such as parenting stress (Kazdin & Mazurick, Reference Kazdin and Mazurick1994) and history of psychopathology (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Belcher, Budhathoki, Ofonedu and Uveges2018; Kazdin et al., Reference Kazdin, Mazurick and Bass1993; Werba, Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, Reference Werba, Eyberg, Boggs and Algina2006).

As is the case with other evidence-based family interventions, patterns of engagement and attrition in PCIT may depend on the family's presenting concerns and the manner in which PCIT is delivered. For example, lower attrition rates are generally reported among lower risk families with children presenting with disruptive behavior concerns (Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson and Touyz2003, Reference Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson and Touyz2004). Perhaps not surprisingly, higher risk families, such as those referred for treatment by child welfare services, show higher rates of treatment attrition (e.g., Lanier et al., Reference Lanier, Kohl, Benz, Swinger, Moussette and Drake2011). Studies of treatment persistence and dropout in PCIT also vary considerably in how attrition is defined, further complicating matters. For example, in studies of attrition in mastery-based PCIT (i.e., in which sessions continue until parents meet criteria for skills mastery), treatment dropout is defined as leaving treatment prior to reaching skills mastery. Thus, families may be considered “dropouts” even after attending more than 25 sessions. By contrast, studies of time-limited PCIT employed in randomized clinical trials define attrition as dropping out before the total number of sessions available to a family, which may be far fewer in some cases. These differences in conceptualizing the timing of attrition deserve careful attention in studies of PCIT dropout and treatment effectiveness, given that PCIT is effective in modifying children's behavioral problems even among families who fail to meet PCIT mastery (e.g., Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Silovsky, Funderburk, Valle, Brestan, Balachova and Bonner2004; Lieneman et al., Reference Lieneman, Quetsch, Theodorou, Newton and McNeil2019).

Some studies of attrition from PCIT document a host of sociodemographic predictors, including single parent status, employment, and lower parent educational levels and income (e.g., Bagner & Graziano, Reference Bagner and Graziano2013; Fernandez & Eyberg, Reference Fernandez and Eyberg2009; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Belcher, Budhathoki, Ofonedu and Uveges2018). However, other studies found that socioeconomic status (SES) factors were not significant when factors such as parenting stress were also considered (Capage, Bennett, & McNeil, Reference Capage, Bennett and McNeil2001; Werba et al., Reference Werba, Eyberg, Boggs and Algina2006). In addition, some evidence suggests that greater levels of observed negative parenting at treatment-entry may increase odds of dropout from time-unlimited, mastery-based PCIT (Fernandez & Eyberg, Reference Fernandez and Eyberg2009; Lieneman et al., Reference Lieneman, Brabson, Highlander, Wallace and McNeil2017).

Identifying predictors of PCIT attrition in child welfare-involved families

Few studies have examined predictors of attrition from PCIT in child welfare populations. Many sociodemographic risk factors for dropout from various family-based interventions are shown to be more prevalent in child welfare-involved families (e.g., single parent status, lower income levels; Gopalan et al., Reference Gopalan, Bannon, Dean-Assael, Fuss, Gardner, LaBarbera and McKay2011), though notably such sociodemographic factors are not easily intervened upon. Randomized clinical trials of PCIT for child maltreating families generally employ shorter, standard-length protocols for treatment averaging 16–20 sessions (Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Silovsky, Funderburk, Valle, Brestan, Balachova and Bonner2004; Nekkanti et al., Reference Nekkanti, Jeffries, Scholtes, Shimomaeda, DeBow, Norman Wells and Skowron2020; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Thomas and Zimmer-Gembeck2012); however, few of these studies have examined predictors of attrition. Among these, Thomas and Zimmer-Gembeck (Reference Thomas and Zimmer-Gembeck2012) found retention was unrelated to sociodemographic factors. Discovery of new, potentially modifiable predictors of dropout and retention is critically important to inform efforts to support persistence in PCIT treatment among child welfare-involved families and improve outcomes for children and families who may need it the most.

In the current study, we focused our attention on individual difference factors known to heighten risk for CM perpetration, namely, behavioral and physiological markers of parent dysregulation and maladaptive socio-cognitive processes (described below). We reasoned that these difficulties also may leave families more vulnerable to non-engagement or at increased risk for dropping out of PCIT, and thus, sought to test these as predictors of dropout and persistence in child welfare-involved families. Furthermore, because few studies of treatment retention in family-based interventions have considered timing of dropout (cf. Gross et al., Reference Gross, Belcher, Budhathoki, Ofonedu and Uveges2018), another aim of this study was to examine the timing of dropout in PCIT to better understand differential predictors of treatment engagement and retention in PCIT for child welfare-involved families. At the time of this study, we were aware of no published studies examining this collection of individual difference predictors of PCIT engagement nor of efforts to differentiate predictors of non-engagement, early- and late-stage dropout, and treatment completion, among child welfare-involved families.

Parent self-regulation

Inhibitory control

Self-regulation skills facilitate flexible and intentional behavior that is essential for warm, responsive parenting, whereas parent dysregulation highlights risk for perpetrating CM and other forms of harsh parenting (Fontaine & Nolin, Reference Fontaine and Nolin2012; Skowron, Reference Skowron, Noone and Papero2015). One aspect of self-regulation, inhibitory control, enables parents to flexibly respond to their children by switching or alternating their attention as needed, and inhibiting automatic behavioral responses in favor of alternatives that better suit the child's needs and situational demands. For example, a tired and stressed parent with good inhibitory control skills might consciously refrain from yelling “stop it!” at their child when they find her jumping on the couch in muddy shoes, and instead, calmly instruct their child “please sit down on your bottom and take off your shoes.” Prior studies have found clear links between inhibitory control in parents and sensitive, involved parenting (e.g., Crandall, Deater-Deckard, & Riley, Reference Crandall, Deater-Deckard and Riley2015), use of effective discipline strategies (Chen & Johnston, Reference Chen and Johnston2007), and responding positively to children's negative emotion (Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, & Reiser, Reference Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant and Reiser2007). Conversely, poor inhibitory control is associated with the use of harsh, aversive parenting (Deater-Deckard, Wang, Chen, & Bell, Reference Deater-Deckard, Wang, Chen and Bell2012) and increased CM risk (Crandall et al., Reference Crandall, Deater-Deckard and Riley2015; Fontaine & Nolin, Reference Fontaine and Nolin2012).

Parent coaching in early PCIT sessions (i.e., CDI phase) often involves searching for positive child behaviors to praise while purposefully ignoring children's negative, attention-seeking behaviors (e.g., grabbing, yelling) and other minor misbehavior. In later PCIT sessions (i.e., PDI phase), parents must inhibit harsh, reactive responses to disobedient child behavior in order to follow a sensitive discipline protocol, making inhibitory control particularly important for treatment success. Given the natural demands of parenting on parents’ self-regulation skills together with documented deficits in self-control among CM parents, we sought to test whether parents’ pretreatment self-regulation skills and social cognitions would predict PCIT engagement and persistence in the current study.

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia

In addition to behavioral measures of parent self-regulation (e.g., inhibitory control), respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) represents a peripheral physiological marker of regulation. Bagner and colleagues have investigated RSA responding in PCIT with premature infants (e.g., Bagner et al., Reference Bagner, Sheinkopf, Miller-Loncar, Vohr, Hinckley, Eyberg and Lester2009; Graziano, Bagner, Sheinkopf, Vohr, & Lester, Reference Graziano, Bagner, Sheinkopf, Vohr and Lester2012); however to our knowledge, no studies to date have investigated parent RSA as an predictor of engagement and persistence in PCIT. RSA is a measure of the cyclical oscillations in heart rate (HR) across successive respiratory cycles (i.e., HR acceleration during inhalation and HR deceleration during exhalation), and indexes parasympathetic nervous system (PNS)-linked cardiac activity (Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, 1996). RSA values are used frequently to assess physiological activity at rest and change in RSA from resting conditions to emotionally evocative contexts, such as in Parent×Child interactions.

Lower resting RSA is thought to reflect deficits in top-down control of self- and emotion-regulation and has been observed in both child welfare-involved parents (Creaven, Skowron, Hughes, Howard, & Loken, Reference Creaven, Skowron, Hughes, Howard and Loken2014; Skowron et al., Reference Skowron, Loken, Gatzke-Kopp, Cipriano-Essel, Woehrle, Van Epps and Ammerman2011), parents at risk for perpetrating child physical abuse (Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Hiraoka, McCanne, Reo, Wagner, Krauss and Skowronski2015), and a wide range of psychopathology (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015). In terms of RSA reactivity to emotionally evocative events, excessive RSA withdrawal (i.e., decreases in RSA from baseline levels) in stressful contexts also is linked to a range of psychopathology (Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Bell, Knapton, McDonough-Caplan, Shader and Zisner2019). Previous research has shown that parents who display more negative, aversive parenting behaviors evidence lower RSA scores (i.e., greater RSA withdrawal) during interactions with their children (Lorber & O'Leary, Reference Lorber and O'Leary2005; Smith, Woodhouse, Clark, & Skowron, Reference Smith, Woodhouse, Clark and Skowron2016). In contrast, parents who display warm, responsive parenting show higher RSA during mutually positive interactions with their children (Augustine & Leerkes, Reference Augustine and Leerkes2019; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Woodhouse, Clark and Skowron2016), and greater RSA withdrawal while interacting with their distressed children (i.e., following the still-face paradigm; Ablow, Marks, Shirley Feldman, & Huffman, Reference Ablow, Marks, Shirley Feldman and Huffman2013; Joosen, Mesman, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, Reference Joosen, Mesman, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2013; Leerkes, Su, Calkins, Supple, & O'Brien, Reference Leerkes, Su, Calkins, Supple and O'Brien2016).

Numerous studies indicate that child welfare-involved parents show heightened physiological reactivity to their children (McCanne & Hagstrom, Reference McCanne and Hagstrom1996), with some recent work suggesting these parents may experience positive parent-child interactions as physiologically taxing. For example, in a study of CM families, Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Benjamin, Pincus, and Van Ryzin (Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Benjamin, Pincus and Van Ryzin2013) documented a pattern of decreasing RSA scores in physically abusive mothers while they engaged in positive play with their child, and links between RSA withdrawal and subsequent increases in harsh, aversive parenting moments later in the interaction (Skowron et al., Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Benjamin, Pincus and Van Ryzin2013). In another study with the same CM families, Norman Wells, Skowron, Scholtes, and DeGarmo (Reference Norman Wells, Skowron, Scholtes and DeGarmo2020) found that physically abusive mothers responded to their children's prosocial bids for guidance with subsequent RSA withdrawal, whereas nonmaltreating mothers responded to their child bids for guidance with increasing RSA (i.e., greater physiological calm; Norman Wells et al., Reference Norman Wells, Skowron, Scholtes and DeGarmo2020). Together these findings suggest that one reason CM parenting is so difficult to modify may be because physiological reactivity appears to fuel aversive parenting. We reasoned that parents’ RSA responding during emotionally evocative interactions with their children, namely less RSA activation during a positive social engagement task (SET) and less RSA withdrawal during a more challenging toy clean-up task, may predict risk for dropout.

Parent social cognitive processes

Attributions about child

Parental attributions, or the ways parents interpret and evaluate their child and their child's behavior (Beckerman, van Berkel, Mesman, & Alink, Reference Beckerman, van Berkel, Mesman and Alink2017), may influence parents’ willingness to engage and persist in PCIT. Studies show that parents who think of their children in positive, developmentally sensitive ways tend to engage in warm, responsive parenting and enjoy parenting more (Beckerman, van Berkel, Mesman, Huffmeijer, & Alink, Reference Beckerman, van Berkel, Mesman, Huffmeijer and Alink2019; Hastings & Rubin, Reference Hastings and Rubin1999). In contrast, parents who hold negative attributions of their children, and consequently view their children as intentionally misbehaving, deliberately hostile, controlling, and acting with malice, are more likely to engage in harsh parenting, acts of child physical abuse (Azar & Twentyman, Reference Azar, Twentyman and Kendall1986; Bradley & Peters, Reference Bradley and Peters1991; Bugental, Reference Bugental and Sameroff2009; Larrance & Twentyman, Reference Larrance and Twentyman1983), and dropout from family-based interventions (Mattek, Harris, & Fox, Reference Mattek, Harris and Fox2016). As such we hypothesized that negative parent attributions might also predict risk for family dropout from PCIT.

Threat-related attentional bias

CM parents show heightened vigilance to threat detection and tend to privilege attention to negative emotional cues during caregiving interactions. Meta-analysis has shown that anxious adults and children both display threat-related attentional bias, and overgeneralize anger to neutral stimuli (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, Reference Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2007), or in the case of CM-exposed children, recognize facial displays of anger more quickly than their nonmaltreated peers (e.g., Pollak, Cicchetti, Hornung, & Reed, Reference Pollak, Cicchetti, Hornung and Reed2000; Pollak, Klorman, Thatcher, & Cicchetti, Reference Pollak, Klorman, Thatcher and Cicchetti2001). However, to our knowledge, no research to date has studied the effects of threat-related attentional biases on parent engagement or success in parenting interventions, and in particular among child welfare involved parents. We reasoned that parents who tend to overgeneralize perceptions of anger when exposed to neutral facial cues may find it more difficult to perceive positive changes in their child's behavior or recognize increasing warmth and positive connection in their relationship with their child. In this way, we predicted parents with greater threat-related attentional bias would be at greater risk for dropout from PCIT.

Readiness for change

Parents’ readiness or motivation for change has been examined as a predictor of PCIT treatment engagement in child welfare-involved families (e.g., Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Valle, Funderburk, Gurwitch, Silovsky, Bard and Kees2009). Readiness for change may be linked with parental attributions; if parents believe that their behavior has an impact on children's challenging behaviors, they may be more willing to engage in parenting treatment. One study found that for parents who expressed lower readiness to change, engagement in a “motivational enhancement” (ME) session prior to the start of PCIT increased treatment retention (Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Valle, Funderburk, Gurwitch, Silovsky, Bard and Kees2009). However, enhancing motivation does not always promote treatment engagement among child welfare-involved families, which may suggest that other factors are at play in determining treatment engagement (Webb, Thomas, McGregor, Avdagic, & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Webb, Thomas, McGregor, Avdagic and Zimmer-Gembeck2017). One explanation for diverging findings is that motivation is an important factor for choosing to enter treatment rather than sticking with treatment (or vice versa). More research is necessary to test whether parents’ readiness to change impacts attrition to a different extent depending on the stage of treatment.

Current study

There is a paucity of research on predictors of engagement and persistence in PCIT among child welfare-involved families. Given that PCIT is effective as well as cost-effective (Aos, Lieb, Mayfield, Miller, & Pennucci, Reference Aos, Lieb, Mayfield, Miller and Pennucci2004), better identification of predictors of treatment persistence could inform strategies to extend the reach of this program ,which has significant implications for public health and safety for children. In the current study, we tested whether parents’ self-regulation skills and social-cognitive processes at pre-treatment play an important role in whether child welfare-involved families persist in PCIT or are at risk for dropping out. We theorized that these factors which confer risk for CM also pose challenges for family engagement in PCIT. Thus, we tested whether markers of parent self-regulation (i.e., inhibitory control, RSA responses during mutually positive and challenging dyadic interaction task, and self-reported executive functions), and social-cognitive processes (i.e., quality of parent attributions, threat sensitivity, and readiness for change) would predict engagement and attrition in PCIT for a sample of child welfare-involved families. We hypothesized that greater parent self-regulatory skills and more adaptive social cognitions would predict persistence in PCIT.

Next, we operationalized treatment persistence using four ordinal categories to distinguish families who (a) declined to engage in PCIT, (b) dropped out during the CDI phase, (c) dropped out during the PDI phase, and (d) completed treatment, and treated these analyses to be exploratory in nature. To our knowledge, this is the first study of PCIT in child welfare families to consider parent self-regulatory and socio-cognitive processes as predictors of PCIT attrition across four different stages of treatment.

Method

Participants

The present study is an National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded randomized clinical trial investigating the biological and behavioral mechanisms of change in PCIT among a sample of child welfare-involved families. Participants were recruited directly through the Department of Human Services (DHS) by their child welfare or self-sufficiency caseworkers. Eligible families met the following criteria at study enrollment: (a) the parent was 18+ years old, (b) the parent was the participating child's biological parent or custodial caregiver, (c) the child was 3–7 years old, (d) the participating parent and all caregivers in the home had no prior documented history of perpetrating child sexual abuse, and (e) the parent provided written informed consent for both themselves and their child to participate. Participants included 204 child welfare-involved parents and their 3–7-year-old children. Of these families, 120 were randomly selected to receive PCIT and were included in the analyses in the present study. (For more information on the larger clinical trial, including recruitment information, the services-as-usual control group, and further study protocol, please see the study protocol in Nekkanti et al., Reference Nekkanti, Jeffries, Scholtes, Shimomaeda, DeBow, Norman Wells and Skowron2020.)

Of this intervention subsample of 120 participants, 89% of parents were mothers (11% fathers), and 67.5% were White/European American, 22.5% were Multi-Ethnic, 2.5% were Latinx/Hispanic American, 2.5% were Pacific Islanders, 1.7% were Black/African American, 0.8% were Native American/Alaskan Native, and 2.5% were of unknown race/ethnicity or did not report. Average parent age was 32.4 years, with a range of 18–64 years, and average child age was 4.7 years, with a range of 3–8 years. The mean household income for families was $19,046 per year and ranged from $0 to $66,000 annually. With regard to educational attainment, 0.8% of parents had less than a seventh-grade education, 2.5% completed junior high school, 13.3% completed partial high school, 48.4% completed high school or GED, 13.3% completed technical or vocational training, 15% completed an associate's or junior college degree, 5% completed a bachelor's degree, and 1.7% completed a graduate degree. The large majority of participating caregivers (N = 117, 97.5%) were biological parents of the child, one was an adoptive parent, and two were grandparents.

Procedure

Dyads randomized to receive PCIT participated in assessments conducted at three time points: Time 1 (pre-treatment), Time 2 (mid-treatment), and Time 3 (post-treatment). All assessment visits included parent–child dyadic interaction tasks, individual child tasks, individual parent tasks, and parent reports of their own functioning, their child's functioning, sociodemographic characteristics, and the parent–child relationship. Cardiac physiology was monitored for both parents and children at resting baseline, during solo tasks, during parent-child interaction tasks, and during recovery periods following all tasks. For all assessments, tasks were split across two visits to the lab scheduled approximately one week apart. The present study utilizes data collected at Time 1 (pre-treatment) to predict persistence and dropout in the PCIT intervention. Families were randomized to the PCIT treatment group or a Family Services as Usual (SAU) control condition upon completion of their Time 1 assessment via a double-blind, sealed letter. Overallocation to the PCIT condition occurred at a rate of approximately 1.5:1. Families in the SAU condition received only the services typically provided by child welfare agencies, including in-home family visitation, respite childcare, individual child counseling, and/or parent training. Families were compensated $90 for completing the first visit and $65 for completing the second visit, and received childcare, snacks, a gift for the participating child and $10 for transportation costs at each visit.

Pretreatment, Visit 1

At the initial 2.5-hr visit, parents completed the informed consent procedures and then parent and child were fitted with seven disposable pre-gelled electrodes to record electrocardiogram (ECG). ECG electrodes were placed in a modified Lead II arrangement on the right clavicle, lower left rib, and lower right abdomen. The remaining four electrodes were used to collect impedance data. ECG data were wirelessly transmitted via an ambulatory impedance cardiograph (Mindware Technologies, Westerville, OH, USA) to a desktop computer. Parents and children each wore a vest containing their own Mindware mobile device throughout the entirety of the visit to allow for freedom of movement during the study tasks. All tasks were videotaped for offline behavioral coding.

Dyadic interaction tasks

Following electrode placement, a 3-min resting baseline of parent and child cardiac physiology was collected while the dyad sat together quietly, without touching, and watched a neutral video.

Next, dyads participated in the standardized PCIT Dyadic Assessment Protocol (Eyberg & Funderburk, Reference Eyberg and Funderburk2011), using a standard set of toys in the lab's playroom. Parents received task instructions via a microphone earpiece while they were alone in the room with their child. The PCIT Dyadic Assessment Protocol consists of three standardized 5-min tasks: child-led play, parent-led play, and clean-up. Parents were instructed to follow their child's lead during the first portion, then were told to lead the play and attempt to gain their child's compliance during the second portion. During clean-up, parents were instructed to have their child clean up all the toys in the playroom without physically helping their child put the toys away. Of these three phases of PCIT, RSA was examined only during the clean-up task for the current study (i.e., referred to below as the “challenge task”), as it was believed to be the most challenging task and prior work has shown that similar tasks produce the greatest parasympathetic withdrawal responses in parents and children (Lunkenheimer, Tiberio, Skoranski, Buss, & Cole, Reference Lunkenheimer, Tiberio, Skoranski, Buss and Cole2018). Following this interaction, dyads participated in a 2-min joint recovery while watching the same neutral video as was shown during the resting period.

Next, dyads participated in the SET (adapted from Weismer Fries, Ziegler, Kurian, Jacoris, & Pollak, Reference Weismer Fries, Ziegler, Kurian, Jacoris and & Pollak2005). This task was designed to assess attachment-related neurophysiology from institutionalized children who experienced early neglect when paired with their adoptive caregivers. Parents and children sat in close physical proximity and completed three interactive tasks: (a) gently pointing to features of one another's face (e.g., nose, ears, hair, etc.), (b) touching and counting one another's fingers, and (c) taking turns softly whispering a story in each other's ears. Each task was presented for a fixed time interval and the activity order remained consistent across dyads. Parents’ average RSA was assessed during the duration of the SET as a measure of parasympathetic physiology during a positive, prosocial activity with their child.

Finally, dyads received a brief break and were offered a snack prior to transitioning onto individual tasks. At that time, parents were taken to a separate assessment room in the lab and participated in two cognitive-behavioral tasks, described below.

Pretreatment, Visit 2

Families returned to the lab for a second 2-hr visit approximately one week following their initial appointment. During this visit, parents completed a variety of questionnaires while their child participated in individual tasks. Questionnaires administered assessed a variety of parent, child, and relational characteristics, including parent executive functioning (BRIEF-A), parent attributions of their child (Parent Attribution Test [PAT] and structural analysis of social behavior [SASB]), and parents’ readiness to change their parenting behavior (REDI; each described below). To account for variations in parent literacy, all questionnaires were read aloud to parents and their answers were entered into a laptop computer by a trained research assistant. Upon completion of this visit, families received a sealed letter randomizing them to either the PCIT treatment group or the SAU control condition. Families randomized to the PCIT treatment group received information on the basic structure and goals of PCIT as well as a brief tour of the PCIT clinical rooms.

Intervention

PCIT was delivered to families randomized to the intervention condition in three sequential modules: ME, CDI, PDI in a 22-session standard length protocol consisting of two ME sessions, and a maximum of nine CDI sessions (one teach, eight coaching), and 11 total PDI sessions (one teach, 10 coach). Four intervention families who enrolled early in the trial received greater than the 22 total sessions (23 to 30 sessions) due to extensions granted to help them try to achieve PCIT mastery. No family was denied fewer than 22 PCIT sessions. Families first received two individual ME sessions adapted from a six-week group-based model (Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Silovsky, Funderburk, Valle, Brestan, Balachova and Bonner2004). Following ME, dyads participated in CDI, which promotes the development of positive parenting skills, then PDI, which promotes safe, effective child behavior management skills. During coaching sessions, parents wore a small earpiece and received live support, feedback, and guidance from the therapist, who watched the dyads’ interaction from behind a one-way mirror. PCIT was delivered by eight therapists, including six doctoral-level graduate students, a licensed social worker, and a licensed psychologist. Therapist training conformed to PCIT international standards for observed case practice and intervention fidelity criteria. All therapists received ongoing weekly remote consultation and live supervision of therapy sessions by master PCIT trainers at the University of Oklahoma. All sessions were videotaped, and therapists completed fidelity ratings at the end of each session. Independent raters blind to family outcomes also monitored ongoing fidelity to the treatment model by coding 15% of session videotapes.

Measures

Executive functioning

Parents reported on their own executive functioning abilities on an abbreviated version of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – Adult Version (BRIEF-A; Roth, Isquith, & Gioia, Reference Roth, Isquith and Gioia2005). The abbreviated BRIEF-A administered included 38 items and responses to each item were rated on a three-point frequency scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often). The Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI) was utilized in the current study and includes items from the Inhibit, Shift, Emotional Control, and Self-Monitor scales. Participants’ self-ratings on these scales and indexes are characterized by T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10), with higher scores indicating greater difficulty with behavioral regulation. Internal reliability for raw BRI ratings was strong among this sample (Cronbach's α = 0.92).

Inhibitory control

Parents completed two 6-min blocks of the Stop Signal Task (Aron, Robbins, & Poldrack, Reference Aron, Robbins and Poldrack2004) to assess response inhibition and impulse control. Each trial began with a cue indicating the start of a trial (500 ms), followed by an arrow pointing either left or right (at 1:1 relative frequency) that served as the go signal (1000 ms), followed by an inter-trial interval of variable duration. Parents were instructed to press the left or right arrow indicated during each trial as quickly as possible in response to the go signal. On 25% of the trials, an auditory stop signal is played after the go signal at a variable latency known as the stop-signal delay (SSD). On trials where the stop signal was present, parents were instructed to withhold their button press. Each block of the task consisted of 128 trials, for a total testing time of approximately 12 min and 256 trials. A stop signal response time (SSRT) was calculated by first calculating the overall percent accuracy, and finding the SSD that corresponded to this percent accuracy, then taking the difference between the participant's reaction time on go trials at the percentile which corresponded with the participant's percent accuracy and this SSD, which reflects the efficiency of an individual's inhibitory control process (Aron et al., Reference Aron, Robbins and Poldrack2004). (For instance, if an individual achieved 52% accuracy on the task, their SSRT would be calculated as the difference between their go reaction time at the 52nd percentile and the SSD that corresponded with 52% accuracy.) Higher SSRT scores indicated slower reaction times (i.e., lower inhibitory control).

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia

ECG data were acquired using Mindware's Biolab (2.4) acquisition software, which integrates simultaneously recorded audio and video. Behavioral and procedural event markers were inserted into the physiological data stream during data collection to create time-locked behavioral and physiology data within tasks. Parent RSA was derived from high-frequency heart rate variability measured in the ECG (0.12 to 0.40 Hz). RSA was measured in 30-second epochs and averaged across tasks. Data were visually inspected and cleaned for movement artifacts and equipment errors offline using Mindware HRV Analysis software version 3.1.3. In the present study, parents’ RSA was examined in three situations: the resting baseline, the dyadic toy clean-up (i.e., challenge) task, and the dyadic SET (each described above). Baseline RSA was measured as the average parent RSA during the joint resting period. Two RSA reactivity scores were calculated: first, RSA reactivity for the challenge task was measured as the difference between parent RSA during the toy clean-up task and their baseline RSA. Parents’ RSA reactivity for the SET was similarly measured as the difference between parent RSA during the SET and their baseline RSA. In both cases, higher scores indicated RSA increases and lower scores indicated RSA withdrawal from baseline to task. We elected to use “raw” change scores rather than residualized change scores due to the fact that baseline RSA was also included as a predictor in our models, thus controlled for in the analysis of RSA change.

Parental attributions

Structural analysis of social behavior (SASB)

The short form of the SASB Intrex questionnaires (Benjamin, Rothweiler, & Critchfield, Reference Benjamin, Rothweiler and Critchfield2006) was used to assess parent perceptions of their child's harsh, controlling behavior toward them. Specifically, parents’ responses on two items (Cluster 15 – “strict control” and Cluster 16 – “harsh, critical control”) from the Child with Me – Transitive scale were summed to create a total child harsh control toward parent score. Parents responded to each item with a score ranging from 0 (does not apply at all/never) to 100 (applies perfectly/all the time), thus, measures of harsh child control could range from 0 and 200.

Parent Attribution Test

The Parent Attribution Test (PAT; Bugental, Blue, & Cruzcosa, Reference Bugental, Blue and Cruzcosa1989) is a short questionnaire that utilizes vignettes to determine the amount of control an individual perceives themselves and a child as having during a hypothetical caregiving situation. Parents were asked about factors that may produce a successful versus unsuccessful interaction with a hypothetical neighbor's child. Some factors place the locus of control with the parent (e.g., using the wrong approach for this child; being in a bad mood that day) while others place control with the child (e.g., the child was stubborn and resisted your efforts; the child made little effort to attend to what you said or did). Parents rated each factor on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = not at all important to 7 = very important. Average scores were then calculated for parents’ perception of the parent being in control of disputes (referred to as “parent control” in the current study) and parents’ perception of the child being in control (referred to as “child control”). Individual scores were used rather than a composite because the scores are not mutually exclusive, meaning that parents could rate both themselves and children as equally high or equally low on control.

Threat-related attentional bias

The emotional go/no-go task (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Fan, Magidina, Marks, Hahn and Halperin2007; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Clerkin, Halperin, Newcorn, Tang and Fan2009) was used to assess parents’ attentional bias to angry facial cues. Parents were instructed to press a response key when a target emotion was presented and refrain from responding when a nontarget emotion was presented. Stimuli included images of neutral, angry, happy, sad, and fearful facial expressions. Parents completed eight blocks; during four blocks, neutral faces were the target expression, and during the four remaining blocks one of the four emotions (angry, happy, sad, or fearful) was the target expression. Each block consisted of 30 trials with 15 go trials and 15 no-go trials, making a total of 240 trials across all eight blocks. The target designation was counterbalanced across each block of trials, such that target emotions were presented in a random order. Rates of correct responding (i.e., pressing the button when the target is presented, also referred to as “correct gos”) and false alarms to distractors (i.e., pressing the button when the nontarget stimulus is presented) were calculated. In the current study, the rate of false alarms to neutral facial displays during the angry target blocks was used to assess threat-related attentional bias, in which neutral expressions were misinterpreted as anger (Pollak et al., Reference Pollak, Klorman, Thatcher and Cicchetti2001).

Readiness for parenting change

The REDI (Mullins, Suarez, Ondersma, & Page, Reference Mullins, Suarez, Ondersma and Page2004) was originally developed for substance-abusing parents involved in combined substance use and child welfare services and assesses motivation to change parenting. The REDI was adapted by Chaffin et al. (Reference Chaffin, Valle, Funderburk, Gurwitch, Silovsky, Bard and Kees2009) by modifying items to reflect parent motivation for engaging in PCIT and adding items related to program content and goals of reducing harsh punishment, producing a 23-item scale with an overall total score. Items on the adapted REDI measure parent readiness to change their parenting behavior, problem recognition, beliefs about harsh discipline, attitude towards participating in a parenting program, and self-efficacy. In the present study, total scores from the REDI were collected to assess parents’ readiness to change across all assessed domains. The REDI scale has demonstrated high internal reliability in prior studies (e.g., Cronbach's α = 0.84; Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Valle, Funderburk, Gurwitch, Silovsky, Bard and Kees2009). Reliability for the current sample of intervention participants was good (Cronbach's α = 0.81).

Negative parenting behavior

Video-recorded parenting behaviors were transcribed and observationally coded during the standard PCIT dyadic assessment protocol (i.e., child-led play, parent-led play, and clean-up tasks) using the well-validated Dyadic Parent–Child Interaction Coding System, fourth edition (DPICS-IV; Eyberg, Nelson, Ginn, Bhuiyan, & Boggs, Reference Eyberg, Nelson, Ginn, Bhuiyan and Boggs2013). In the present study, negative parenting behaviors comprised direct and indirect commands that took control during child-led play, and negative talk/criticisms coded during child-led play, parent-led play, and toy clean-up. Negative talk/criticism is defined by the DPICS-IV coding system as verbal expressions suggesting disapproval of a child's attributes, activities, products, or choices, as well as speech considered to be sarcastic, rude, or impudent (Eyberg et al., Reference Eyberg, Nelson, Ginn, Bhuiyan and Boggs2013). Commands are defined as statements directing children to perform a vocal or motor behavior, mental or internal action, or unobservable action (e.g., think, decide) that may be direct or indirect (Eyberg et al., Reference Eyberg, Nelson, Ginn, Bhuiyan and Boggs2013). Negative talks are broadly considered to characterize harsh parenting during any condition, while commands during child-led play were characterized as negative parenting behaviors due to the parent being instructed during this task to let their child choose an activity and follow their child's lead in play. These negative parenting behaviors were summed and then divided by the total number of coded parent behaviors to create a proportion of negative parenting during the dyadic interaction task. Coders completed 20 hr of intensive training prior to coding and continued to meet regularly to maintain 80% inter-rater reliability. All coders were blind to participants’ assessment wave and condition group. Reliability coding was completed on 20% (n = 89) of study families and 84% inter-rater reliability was achieved. Of the 89 families coded for reliability, 30% (n = 27) were also coded for consensus.

Results

Data analysis plan

The goal of the present study was to predict engagement and retention with a PCIT program for child-welfare involved families. The focus was on discerning whether attributes of the parent, including ability to self-regulate and perceptions of their child's and their own behavior, would predict engagement in some or all of the treatment in a sample already at high-risk for early program dropout. Further, we sought to investigate unique predictors of dropout at each stage of the program, as each involves different challenges and thus may require different skill sets. We implemented multinomial logistic regression (MLR) to examine which of these factors predicted dropout at various stages throughout treatment. MLR produces odds ratios for each parameter indicating whether higher scores predict greater or lesser odds of dropping out during a particular stage versus dropping out earlier, later, or completing the treatment. Our outcome variable was a four-level categorical variable indicating where in treatment an individual dropped out: before treatment (non-engagers), during the CDI phase, during the PDI phase, or completed treatment.

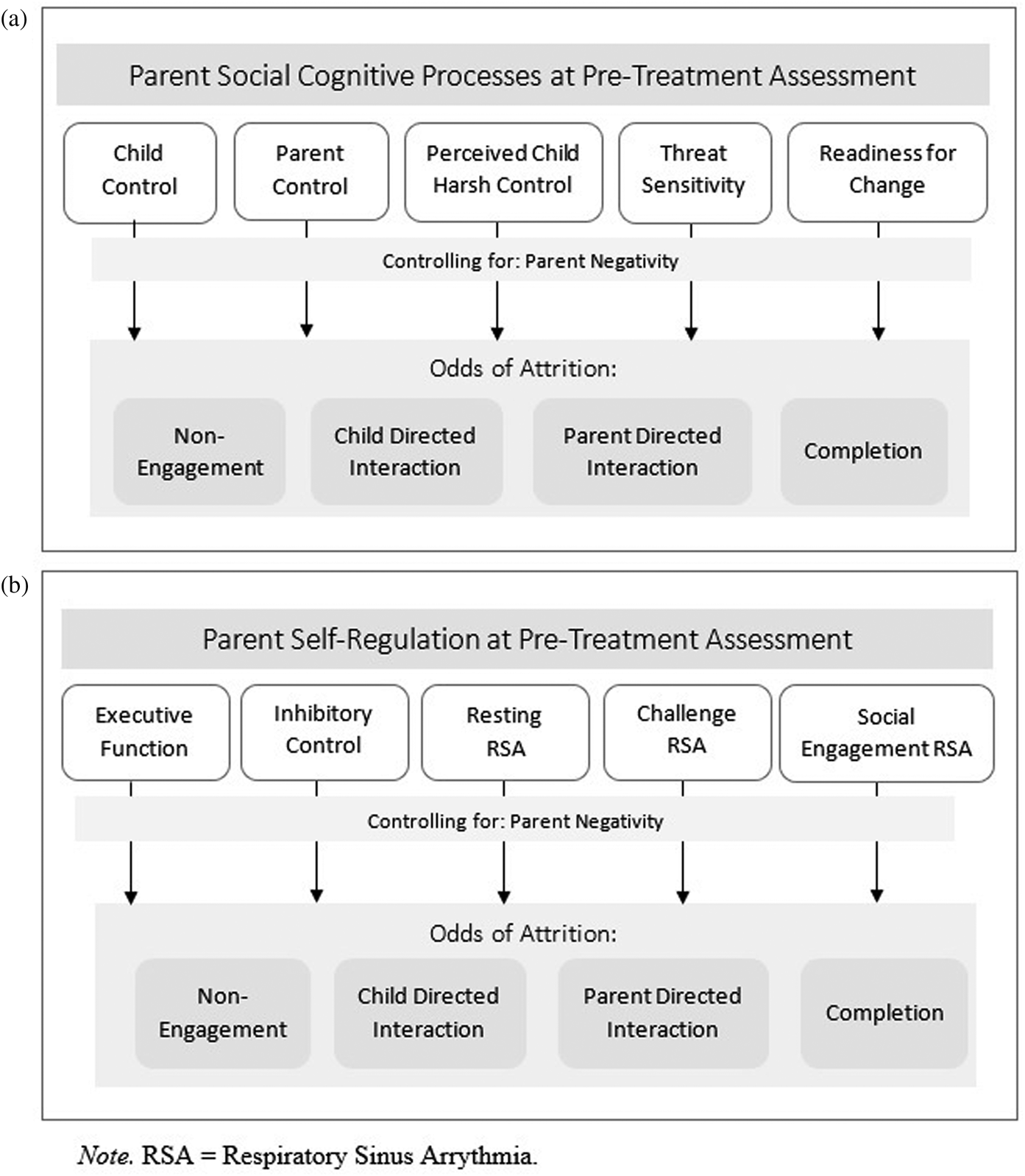

Figure 1 displays the conceptual models that guided our analyses. Both models included negative parenting proportion as a control variable to enable the observation of the effects of parent characteristics on treatment persistence independently of their potential effects on parenting. Each of these models was run several times, alternating the reference category to allow for the comparison of each attrition category to the other three.

Figure 1. Conceptual illustrations of multinomial logistic regression models for (a) parents’ pre-treatment social cognitive processes and (b) parents’ pre-treatment self-regulation skills predicting attrition at four stages of Parent×Child interaction therapy (PCIT) treatment.

Preliminary analyses

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for the key predictors are displayed in Table 1. Of the total N = 120, 41 parents did not engage in treatment (34.5%), 26 parents engaged in treatment but dropped out during CDI (21.7%), 16 parents dropped out during PDI (13.3%), and 37 completed treatment (30.8%). Participants who dropped out during CDI attended 4.19 CDI sessions on average (SD = 3.30). Participants who dropped out during PDI attended an average of 8.88 CDI sessions (SD = 2.45) and 3.69 PDI sessions (SD = 1.85). Participants who completed treatment attended an average of 8.59 CDI sessions (SD = 1.52) and 10.41 PDI sessions (SD = 2.42). On average, the change in parent RSA from baseline to the challenge (cleanup) task was moderately negative (M = −0.16, SD = 0.86), and scores ranged from −3.06 to 2.70, with 54.7% of the sample showing a withdrawal response (negative change score), while a sizable proportion of parents posted RSA increases instead. In contrast, the average change in RSA from the resting baseline to the SET was moderately positive (M = 0.21, SD = 0.81); scores ranged from −2.43 to 2.83, with 61.3% of the sample showing an increase in RSA (positive change score). Thus on average, RSA increased during this task relative to baseline, which may be expected given the role of parasympathetic activation in facilitating social engagement during face-to-face interactions (Norman Wells et al., Reference Norman Wells, Skowron, Scholtes and DeGarmo2020; Skowron et al., Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Benjamin, Pincus and Van Ryzin2013), though a number of parents in the sample displayed decreases in RSA scores instead.

Table 1. Means, ranges, and bivariate correlations among parent social cognitive and self-regulation predictors of Parent×Child interaction therapy (PCIT) attrition

^p < .1, *p < .05, **p < .01.

PAT = Parent Attribution Test, higher scores indicate greater perceived child control or parent control over Parent×Child interaction dynamics; SASB = structural analysis of social behavior, higher child harsh control scores indicate greater perceived harsh and controlling behavior from child to parent; Emo % false alarms anger = proportion of trials where neutral faces were misidentified as angry on the emotional go/no-go task, higher scores indicate greater threat sensitivity; REDI = readiness for parenting change inventory, higher scores indicate greater readiness to change; BRIEF-A = behavioral rating inventory of executive functioning – adult version; BRI = Behavioral Regulation Index, higher scores indicate greater problems with behavioral regulation; SSRT = stop signal reaction time, higher scores indicate slower reaction time; RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; ΔRSA Challenge = change in RSA from baseline to challenging cleanup task; ΔRSA social engagement = change in RSA from baseline to social engagement task, higher scores indicate greater RSA increases (i.e., less RSA withdrawal); proportion negative parenting = higher scores indicate greater observed negative parenting.

There were minimal missing data for some of the predictors, baseline RSA (three cases), challenge RSA change (three cases), social engagement RSA change (five cases), SSRT (11 cases), emotional go/no-go (one case), and PAT (one case). The most common reason cases were missing was due to noncompletion of the assessment tasks, or in a few cases, equipment malfunction. As the multinomial logistic regression models were run using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation, missing data were accounted for and the full sample of 120 was retained. A few predictors (SSRT, percentage of false alarm responses to angry faces in the emotional go/no-go task, change in RSA from resting to the challenge task, and change in RSA from resting to the SET) had cases that would be considered outliers based on the criteria of being more than 3 SD above or below the mean. Rather than dropping the data, a winnowing procedure was used to adjust outliers to be equal to the value of 3 SD above or below the mean. This allows for retaining information about parents who may have extreme scores, as would be expected in a high-risk sample, but limits the influence outliers may have in statistical analyses.

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were run to determine the extent to which sociodemographic values differed based on treatment engagement and dropout. Contrary to prior research, no relationships were observed between parents’ income [F(98) = 0.22, p = .88], education level [F(119) = 2.10, p = .10], or household size [F(119) = 1.25, p = .29] and persistence; however, this may be expected in a high-risk sample with restricted variability in these domains. Further, we did not observe any relationships between parents’ age [F(119) = 0.284, p = .83] or race/ethnicity [F(118) = 0.48, p = .69], or children's age [F(119) = 0.88, p = .45] and treatment persistence. Considering these null findings, and in line with our theoretical models and goals of the present study, the sociodemographic parameters were trimmed from our final models.

Primary analyses

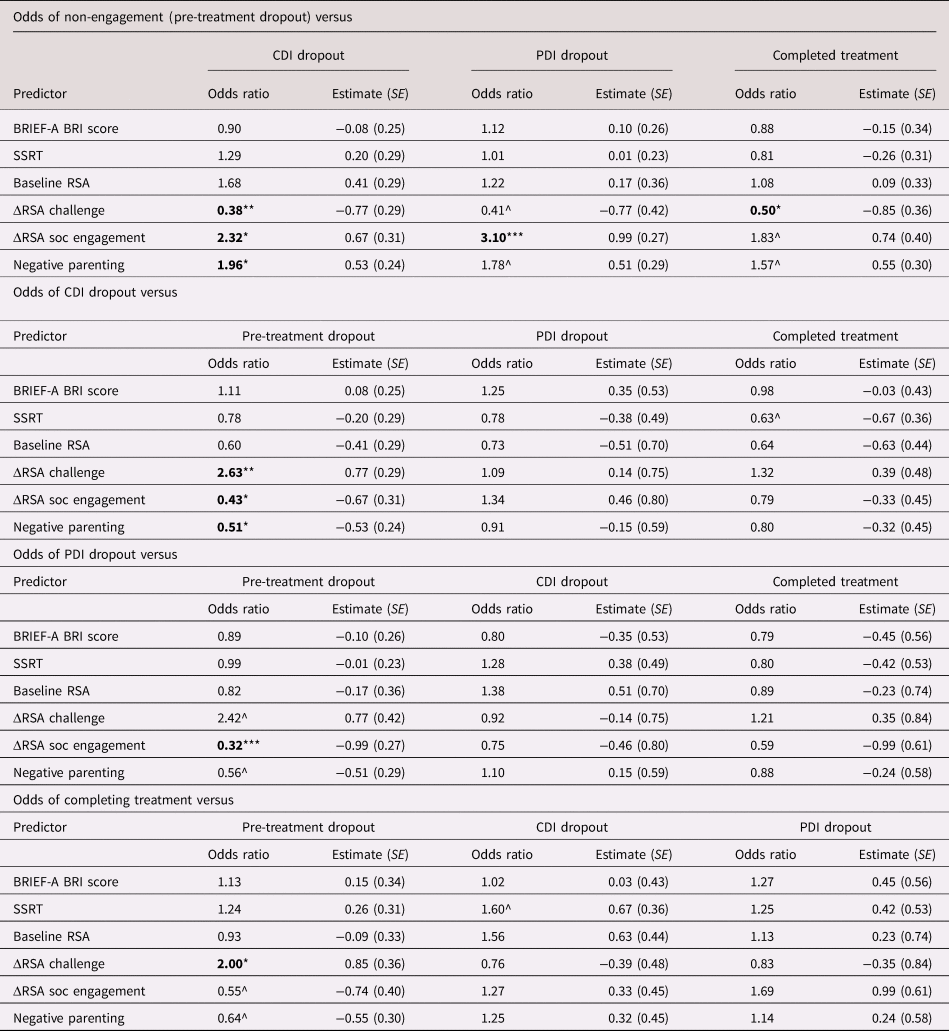

Estimates, standard errors, p values, and odds ratios are displayed in Table 2 for the self-regulation model and in Table 3 for the social-cognitive processes model.

Table 2. Results of multinomial logistic regression parent self-regulation predicting Parent×Child interaction therapy (PCIT) engagement model

^p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Double lines divide treatment phases that occur before the target category versus after.

BRIEF-A = behavioral rating inventory of executive functioning – adult version; BRI = Behavioral Regulation Index; CDI = child-directed interaction; PDI = parent-directed interaction; RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SSRT = stop signal response time

Table 3. Results of multinomial logistic regression parent social cognitive processes predicting Parent×Child interaction therapy (PCIT) engagement model

^p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Double lines divide treatment phases that occur before the target category versus after.

BRIEF-A = behavioral rating inventory of executive functioning – adult version; BRI = Behavioral Regulation Index; CDI = child-directed interaction; Emo % false alarms anger = proportion of trials where neutral faces were misidentified as angry on the emotional go/no-go task, higher scores indicate greater threat sensitivity; PDI = parent-directed interaction; REDI = readiness to change their parenting behavior; RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SSRT = stop signal response time

Pre-treatment dropout (non-engagement). Levels of observed negative parenting during the pre-treatment assessment were salient in predicting who would decline treatment in PCIT. In the self-regulation model, greater negative parenting predicted greater odds of non-engagement versus engaging in treatment and dropping out during the CDI phase (OR = 1.96, β = 0.53, p = .025), and marginally versus dropping out in PDI (OR = 1.78, β = 0.99, p = .078) or completing the intervention (OR = 1.57, β = 0.55, p = .078). Similarly, in the social-cognitive processes model, greater observed negative parenting during the pre-treatment assessment predicted greater odds of non-engagement versus dropping out during either the CDI phase (OR = 1.71, β = 0.56, p = .009) or PDI phase (OR = 1.94, β = 0.50, p = .020).

In the self-regulation model, parents’ RSA reactivity to the challenge task (i.e., toy clean-up) and the SET also predicted who would decline treatment. Greater parent RSA withdrawal from baseline to the toy clean-up challenge task predicted increased odds of not engaging in PCIT versus dropping out during the CDI phase (OR = 2.63, β = 0.77, p = .008), marginally versus dropping out during PDI (OR = 2.42, β = 0.77, p = .066), or versus completing treatment (OR = 2.00, β = 0.85, p = .020). Further, results also showed that greater RSA increases from baseline to the SET predicted greater odds of non-engagement versus dropping out during the CDI phase (OR = 2.32, β = 0.67, p = .029) or the PDI phase (OR = 3.10, β = 0.99, p < .001), and marginally versus completing treatment (OR = 1.83, β = 0.55, p = .065).

In the social-cognitive processes model, parents’ attributions on the PAT also appeared salient for predicting who would decline treatment. Parents who perceived that children have greater responsibility and control in shaping interaction dynamics had greater odds of not engaging in treatment versus dropping out later during PDI (OR = 1.91, β = 0.49, p = .022) or completing treatment (OR = 1.61, β = 0.49, p = 027).

CDI dropout. Parents’ elevated threat sensitivity, measured as a greater percentage of “false alarm” responses to neutral faces during the angry condition, was a significant predictor of dropout during the CDI phase of treatment. Parents who more frequently erred in perceiving anger in neutral facial expressions had greater odds of dropping out during the CDI phase of PCIT versus non-engagement (OR = 2.00, β = 0.72, p < .001), dropping out later during PDI (OR = 1.87, β = 0.53, p = .008), or completing treatment (OR = 2.56, β = 0.81, p < .001).

PDI dropout. Parents who perceived their children as being more harshly controlling toward them had greater odds of dropping out during the PDI phase versus non-engagement (OR = 2.36, β = 0.65, p = .004), dropping out earlier during CDI (OR = 2.16, β = 0.65, p = .004), or completing treatment (OR = 1.76, β = 0.79, p = .017).

Treatment completion. Parents’ self-reported readiness for change scores significantly predicted treatment completion. Specifically, parents who reported greater readiness to change on the REDI questionnaire had greater odds completing the intervention versus treatment non-engagers (OR = 1.73, β = 0.57, p = .013).

Discussion

This study is the first to report on aspects of parents’ social-cognitive and self-regulatory processes that predict engagement and attrition timing in PCIT among a sample of child welfare-involved families. In addition, through the use of a novel multicategory treatment engagement variable, this study revealed unique predictors of PCIT engagement and timing of attrition. Findings lend support to the prospect that malleable aspects of parents’ functioning, such as quality of parenting, child attributions, attentional biases to anger, and parasympathetically-mediated cardiac control (i.e., RSA), predict engagement and attrition in PCIT among child welfare-involved parents. As such, results of this study highlight plausible new targets of intervention that may promote treatment engagement and retention in these high-risk families. Below, we outline the significant predictors of family engagement and dropout from PCIT at four stages: pre-treatment (non-engagement), CDI, PDI, and treatment completion.

Treatment non-engagement

In the current study, 36% of families randomized to the intervention condition declined to engage in treatment. Findings indicate that observed negative parenting and perceptions of children as more in control and responsible for the outcomes of adult-child interactions were both salient for predicting non-engagement. Parents who engaged in more negative (i.e., harsh, controlling) parenting during the preintervention assessment were less likely to accept the invitation to engage in treatment at all. Likewise, parents who perceived children as more in control and responsible for the outcome of adult–child exchanges relative to adults also were more likely to decline treatment. These findings are in line with other evidence suggesting that parental attributions are important in determining engagement in family-focused interventions, specifically with high-risk, low-income families (Mattek et al., Reference Mattek, Harris and Fox2016). If parents believe that they have little influence over their child's negative behavior, they may be less likely to engage in parenting-focused interventions such as PCIT, which contradict those perceptions (Mattek et al., Reference Mattek, Harris and Fox2016). In line with this idea, prior research on family-focused intervention has evidenced higher attrition rates for parents who believe that they have less control over their child's behavior (Mattek et al., Reference Mattek, Harris and Fox2016; Miller & Prinz, Reference Miller and Prinz2003), whereas parents who perceive their own behavior as the cause of or contributor to their child's problem behavior (or within the parent's control) are more likely to complete treatment (Peters, Calam, & Harrington, Reference Peters, Calam and Harrington2005). The contrast between non-engagers and treatment completers suggests that parents’ locus of control may be an important factor in the decision whether or not to engage in PCIT. Parents who do not perceive adults as more responsible in the context of interactions with a child may recognize a disconnect between the way they parent and the fundamental tenants of evidence-based parenting interventions such as PCIT, which necessitate parent engagement and behavior change along with child behavior change as necessary components of treatment. In such cases, parents may believe that individual child-focused interventions are more suitable for their family needs, given their views that children are more responsible for their own behavior and for the outcomes of their interactions with parents as well. Along these lines, it is also possible that these parents hold beliefs about parenting and child development that are not well aligned with PCIT's core principles, and may further hold beliefs that authoritarian parenting is acceptable and perhaps even preferred for ensuring child compliance.

In addition to displaying negative parenting during interactions with their child, parents who declined treatment also showed greater RSA withdrawal to the challenging joint clean-up task and RSA activation to the prosocial engagement task. The fact that greater RSA withdrawal during the clean-up task with their child, taken together with greater harsh control parenting, predicted increased likelihood of declining treatment suggests that these parents may experience elevated stress reactivity in disciplinary contexts. In contrast to the SET, the toy clean-up challenge task employed in this study is generally unpleasant for children, and evokes negative emotional responses from the child (e.g., resisting, complaining), while the task requires that parents work to gain their child's compliance to clean up a roomful of scattered toys. Prior research with CM families has shown that decreases in RSA during parent-child interactions are followed by increases in harsh, negative parenting among physically abusive parents (Skowron et al., Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Benjamin, Pincus and Van Ryzin2013). Considering that parents who were more likely to forego treatment also displayed greater negative parenting, we may be observing a similar pattern among treatment non-engagers. Parents with these characteristics may have found the prospect of engaging in PCIT to be overwhelming, prompting greater likelihood of non-engagement.

The SET utilized in this study was a prosocial task that prompted gentle physical contact and face-to-face engagement between parent and child. The finding of greater RSA activation among non-engaging parents contradicted our predictions and runs counter to some prior research that documents higher RSA in other warm prosocial parent-child interaction contexts (e.g., Augustine & Leerkes, Reference Augustine and Leerkes2019; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Woodhouse, Clark and Skowron2016). It is important to note that the SET employed in this study was highly structured and further, that parenting behavior was not coded during this task. Therefore it is possible that treatment non-engaging parents behaved in qualitatively different ways with their child than did PCIT engaging parents (i.e., more negative, less engaged, and so forth). Alternately, the non-engaging parents, who viewed children as more responsible for the success of parent-child interactions, may have displayed increased RSA during the task because they felt less responsible for the success of the interactions with their children. Were these parents generally more physiologically reactive to their children than the PCIT-engaging parents, and thus displayed greater physiological calm because their children were pleasant interactive partners, or because the task was so highly structured, unlike the clean-up task? Alternately, were RSA increases helping to compensate for possible sympathetically mediated increases in the arousal levels of these non-engaging parents (i.e., Gatzke-Kopp, Benson, Ryan, & Ram, Reference Gatzke-Kopp, Benson, Ryan and Ram2020)? Comparatively, parents who engaged in treatment and dropped out showed relatively lower RSA in this context, likely indicating the need to mobilize more attentional resources to engage with their child during the interactions required in the task. This finding raises important questions and directions for future research aimed at better understanding the coupling of RSA reactivity and parenting behavior, and the contributions of sympathetic nervous system responding during prosocial parent-child activities in maltreatment parents.

Taken together, this constellation of predictive factors (negative parenting, greater child control attributions, RSA withdrawal to challenge, and RSA increases to social engagement) provide rich new insights into which child welfare-involved parents are more likely to decline a parenting-focused treatment. Given that similar risk factors are observed in parents at risk for perpetrating CM, these findings are especially notable. Parents who are most at risk for perpetrating maltreatment are also among the least likely to voluntarily engage in a treatment shown to be effective at reducing CM recidivism (e.g., Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Kim, Tripodi, Brown and Gowdy2016). Maltreating parents show a pattern of harsh parenting and threat-sensitive attributions in which children are believed to be the cause of dysfunctional interactions, which is accompanied by activation of parent physiological stress response systems during difficult child behavior (i.e., increased cortisol; Lin, Bugental, Turek, Martorell, & Olster, Reference Lin, Bugental, Turek, Martorell and Olster2002; increases in heart rate; Bugental et al., Reference Bugental, Blue, Cortez, Fleck, Kopeikin, Lewis and Lyon1993, Bugental, Lewis, Lin, Lyon, & Kopeikin, Reference Bugental, Lewis, Lin, Lyon and Kopeikin1999; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Bugental, Turek, Martorell and Olster2002; increases in electrodermal activity; Bugental & Cortez, Reference Bugental and Cortez1988; and decreases in RSA; Norman Wells et al., Reference Norman Wells, Skowron, Scholtes and DeGarmo2020). An important avenue for future research will be to quantify observed parenting behaviors among parents at risk for non-engagement; specifically, we may want to know whether RSA increases are associated with low dyadic engagement processes (e.g., less verbalization, lower dyadic synchrony, and more relationship ruptures) from parents, or whether RSA decreases are accompanied by other signs of stress, and whether they drive increases in aversive parenting. Greater understanding into the role of sympathetic input into cardiac responses that support adaptive parenting is also needed.

Attrition during CDI

Among families that engaged in the intervention, 22% dropped out at some point during the CDI phase of treatment, during which parents are taught strategies for interacting with their children in warm, positive ways and sensitively reinforcing children's positive behavior. In CDI, parents learn to use specific praise for positive behavior, describe and reflect their children's behavior and speech, and show enthusiasm and enjoyment of their time together. During CDI sessions, parents become more attuned with their child's behavior, emotions, and thoughts, which in turn could promote increased ability to understand and respond positively to their child's needs (Eyberg et al., Reference Eyberg, Funderburk, Hembree-Kigin, McNeil, Querido and Hood2001). Though interactions are mainly positive during this phase of treatment, parents are asked to follow their child's lead in the play, and to relinquish some control in doing so. Parents are also asked to ignore minor child misbehavior. As such, there are some qualities that the parent brings to the room that could make these activities feel more challenging, and increase the odds of dropout during this phase.

Findings from this study suggest that one such quality may be a threat-related bias toward perceiving anger in facial expressions where none is present. Parents who were more likely to dropout in this CDI phase of treatment were also more likely to see anger in neutral facial expressions in the emotional go/no-go task, relative to other conditions (i.e., not engage, persist to PDI and then dropout, or to complete treatment). Parents with a bias toward perceiving anger may find it more difficult to recognize their children's positive emotional expressions, and acknowledge when their children are behaving in positive, prosocial ways. Such perceptual biases toward angry facial cues also may make it more challenging for parents to ignore their children's minor misbehavior, and respond accurately to positive or neutral cues from their child. Likewise, these more threat-sensitive parents may find it more difficult to relinquish control during the CDI phase's child-led play. It is well established that maltreating parents are more likely to view themselves as victims of their child's misbehavior, and perceive such behavior as threatening and intentional (Bugental, Reference Bugental and Sameroff2009; Bugental & Happaney, Reference Bugental and Happaney2004; Bugental, Blue, & Lewis, Reference Bugental, Blue and Lewis1990; Martorell & Bugental, Reference Martorell and Bugental2006). As such, relinquishing control to the child may cause anxiety for parents who hold threat-sensitive attentional biases in which they perceive anger where none is present, prompting increased likelihood of dropout during the child-led phase of treatment.

Although no research has yet examined general threat sensitivity among maltreating parents using methods we have employed here, prior studies have found that in maltreating families, children who were abused or neglected show a bias wherein they respond more quickly to angry facial expressions (Pollak & Sinha, Reference Pollak and Sinha2002). This bias is interpreted as reflecting a greater vigilance toward aggressive, threatening emotions, arising from experiences with perpetrators of maltreatment and enabling them to more quickly identify threat in social interactions (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Guyer, Hodgdon, McClure, Charney, Ernst and Monk2008; Pollak & Sinha, Reference Pollak and Sinha2002). It is also possible that parents in maltreating families possess related biases, a tendency to perceive anger in neutral facial displays more readily, fueling a heightened sense of threat where there may be none, and lash out in harsh ways as a result. It is possible these findings converge to mark a familial vulnerability or a source of socialization of threat sensitivity from parent to child. This idea is supported in part by prior work that suggests that in families where parents experience symptoms of internalizing psychopathology, both parents and children exhibit threat biases (Bar-Haim et al., Reference Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2007; Morales et al., Reference Morales, Brown, Taber-Thomas, LoBue, Buss and Pérez-Edgar2017; Morales, Pérez-Edgar, & Buss, Reference Morales, Pérez-Edgar and Buss2015).

Attrition during PDI

Thirteen percent (13%) of families dropped out during the PDI phase of treatment during which sessions focus on helping parents building safe, effective discipline skills to use with their children. In this phase, parents are prompted to deliver direct commands and offer praise for child compliance or apply a consistent time-out procedure for handling child misbehavior. As such, the ability to maintain a calm authority during this phase of treatment is crucial. There are characteristics of both the parent and the parent–child relationship that may make this phase difficult to master and increase risk for dropout. For instance, parents may experience challenges with this phase of treatment if they are typically lax in their discipline, allowing misbehavior to continue, or making threats of consequences without following through.

In the current study, we discovered that parents who perceived their children as more harshly controlling had greater odds of dropping out during the PDI phase than non-engagement, dropping out during CDI, or completing treatment. This finding is in line with prior research identifying negative attributions about a child as a propagating factor in the perpetration of CM (Azar & Twentyman, Reference Azar, Twentyman and Kendall1986; Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Hiraoka, McCanne, Reo, Wagner, Krauss and Skowronski2015; Larrance & Twentyman, Reference Larrance and Twentyman1983). In addition, viewing children's misbehavior as intentionally provocative and due to negative dispositional traits may lead parents to believe they are unable to affect change in their child's behavior or successfully interrupt coercive processes, and thus drop out from treatment as a result (Mattek et al., Reference Mattek, Harris and Fox2016). Alternately, parents may resist therapists’ efforts to modify their parenting behaviors and feel little confidence that therapy can modify their child's problem behavior. In these contexts, such beliefs may lead a parent to react defensively to children's behavior or react with anger in retaliation (Bugental, Reference Bugental and Sameroff2009). When applied to the PDI phase of treatment, these parents may have a greater amount of difficulty adhering to guidance provided by PCIT therapists and following through on children's non-compliance with parental directives in a calm and consistent manner to achieve child compliance.

Completing treatment

Approximately one-third (29%) of parents completed a full course of PCIT, in line with other studies of child welfare-involved families’ engagement in family-based interventions (e.g., Lanier et al., Reference Lanier, Kohl, Benz, Swinger, Moussette and Drake2011). Perhaps not surprisingly, child welfare parents who posted higher scores on the readiness to change scale were more likely to complete the PCIT intervention, relative to non-engaging parents. Items on this scale are meant to assess motivation to engage in a parenting intervention and for improving one's parenting skills (i.e., recognizing that there is a problem, wanting to change the problem, and believing that a parenting intervention could be effective for change). Similarly, research on addiction treatment outcomes has documented that individuals who perceive a problem and have the motivation to change are the most likely to institute behavior change when provided adequate means to achieve that goal (Mullins et al., Reference Mullins, Suarez, Ondersma and Page2004). Prior studies have shown that motivation enhancement supplements can be effective for improving persistence in PCIT among child welfare families for whom readiness for change was low, but may be unnecessary or even detrimental for those who are already highly motivated change (e.g., Chaffin, Funderburk, Bard, Valle, & Gurwitch, Reference Chaffin, Funderburk, Bard, Valle and Gurwitch2011; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Thomas, McGregor, Avdagic and Zimmer-Gembeck2017). Findings such as these underscore the central importance of positive beliefs about making changes in parenting and the parent–child relationship for addressing the problem of attrition among these higher risk families.

Clinical implications