American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) groups have faced centuries of systematic oppression and have borne the legacy of this history in the form of economic, social, and health disparities relative to non-AIAN communities (Bohn, Reference Bohn2003; Gone, Reference Gone2007; Gone & Trimble, Reference Gone and Trimble2012; Sarche & Spicer, Reference Sarche and Spicer2008; Shiels et al., Reference Shiels, Chernyavskiy, Anderson, Best, Haozous, Hartage and de Gonzalez2017). These disparities include higher rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) relative to other populations (Brockie, Dana-Sacco, Wallen, Wilcox, & Campbell, Reference Brockie, Dana-Sacco, Wallen, Wilcox and Campbell2015; Kenney & Singh, Reference Kenney and Singh2016; Koss et al., Reference Koss, Yuan, Dightman, Prince, Polacca, Sanderson and Goldman2003). ACEs include experiences of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction that occur before age 18 (Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998) and are related to later mental and physical health concerns (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004; Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012; Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, Reference Edwards, Holden, Felitti and Anda2003; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998). The long-term effects of ACEs may be the result of physiological changes in the immune, nervous, and endocrine systems, which contribute to allostatic load and overload (Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012). ACEs may also influence the next generation, with recent studies finding that among parents who experienced multiple ACEs, parent-reported child social–emotional functioning was also worse than those with lower ACE scores (Brown & Ash, Reference Brown, Ash and Brown2017; Schleuter et al., Reference Schleuter, Mendoza, Hurwich-Reiss, Barrow, Fisher, Watamura and Brown2017).

The current study sought to extend this body of research on the intergenerational effects of ACEs to an American Indian (AI) community population. We are not aware of any study to date that has specifically examined parent ACEs and young children's social–emotional development in an AI or Alaska Native (AN) community sample. In addition, the current study sought to elucidate the path by which past parent adversity might relate to current child social–emotional functioning, and to explore the role of parent–child relationship quality in moderating this path. To this end, a model was tested to examine the relations between parent ACEs, a latent variable of parent mental distress and children's social–emotional functioning among AIAN and non-AIAN parent–child dyads attending an Early Head Start (EHS) program in an AI community. A second model was then tested to examine parent–child relationship quality as measured by a categorical indicator of high versus low parent EA as a moderator, or potential buffer, of this pathway. With these analyses, we aimed to deepen the understanding of the link between parents’ early life adversity and children's social–emotional development in a population that may be particularly vulnerable to adversity and its intergenerational effects. A better understanding of this pathway can inform prevention and intervention efforts that aim to break intergenerational cycles of trauma and adversity in AIAN, as well as other, communities.

ACEs

Adverse experiences in early life, including abuse, neglect, and exposure to family hardship such as domestic violence and parental substance abuse, have long-term impacts on both physical and mental health (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004; Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Holden, Felitti and Anda2003; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998). Exposure to ACEs contributes to a heightened risk for depression, suicide, drug abuse, alcoholism, and risky sexual behaviors, with more ACEs posing greater health risks in a graded fashion (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Holden, Felitti and Anda2003; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998). ACEs lead to long-lasting changes in bodily systems, such as a smaller volume in the prefrontal cortex (Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012). In turn, such changes in the nervous, immune, and endocrine systems lead to allostatic load and overload, contributing to poorer physical and mental health outcomes across the life span (Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012). Considering that well over half (approximately 60%–64%) of adults from large, nationally representative samples report at least one ACE (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998), these findings highlight the need for closer examination of the impact of early adversity on individuals’ well-being, mental health, and relationships (Foege, Reference Foege1998).

AIAN communities experience higher rates of violent victimization, suicide, homicide, motor vehicle accidents, child abuse, and domestic violence relative to non-AIAN communities (CDC, 2003, 2013; Sarche & Spicer, Reference Sarche and Spicer2008), thus placing individuals living in these communities at greater risk for ACEs. Existing studies indicate that 72%–86% of AIAN individuals have experienced at least one ACE, and 17%–35% have experienced four or more (Brockie et al., Reference Brockie, Dana-Sacco, Wallen, Wilcox and Campbell2015; Kenney & Singh, Reference Kenney and Singh2016; Koss et al., Reference Koss, Yuan, Dightman, Prince, Polacca, Sanderson and Goldman2003). Research has explored the relation between early life adversity among AIAN populations and later life mental health and substance use concerns. In a study among seven AI tribes, Koss et al. (Reference Koss, Yuan, Dightman, Prince, Polacca, Sanderson and Goldman2003) found that childhood abuse increased the odds of alcohol dependence in adulthood, with a dose-response effect. In a large community-based study among one Southwest and two Northern Plains AI communities, Libby et al. (Reference Libby, Orton, Novins, Spicer, Buchwald and Beals2004, Reference Libby, Orton, Novins, Beals and Manson2005) found that childhood physical and sexual abuse were both significant predictors of depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders in adulthood. In another more recent study, Brockie et al. (Reference Brockie, Dana-Sacco, Wallen, Wilcox and Campbell2015) examined a modified ACEs measure and mental health among reservation-based AI adolescents and young adults and found that more ACEs increased the odds of depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, suicide attempts, and multiple drug use. Results from these studies suggest that ACEs may be significant contributors to the mental health disparities experienced by AIAN communities more broadly (Gone & Trimble, Reference Gone and Trimble2012).

Parent ACEs, Children's Development, and Parent–Child Relationship Quality

An emerging literature provides evidence for the intergenerational effects of ACEs. Recent studies (Brown & Ash, Reference Brown, Ash and Brown2017; McDonnell & Valentino, Reference McDonnell and Valentino2016; Narayan et al., Reference Narayan, Kalstabakken, Labella, Nerenberg, Monn and Masten2017; Schleuter et al. Reference Schleuter, Mendoza, Hurwich-Reiss, Barrow, Fisher, Watamura and Brown2017) have found that parents with higher ACE scores were more likely to report social–emotional problems among their children. Potential mediators of the relation between parent ACEs and children's social emotional development include parental stress and mental health, both of which may be more likely in the context of parent ACEs and may serve as proximal predictors of children's social–emotional development (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Robbins Broth, Hall and Heyward2011; Guajardo, Snyder, & Peterson, Reference Guajardo, Snyder and Peterson2009; Gutermuth Anthony et al., Reference Gutermuth Anthony, Anthony, Glanville, Naiman, Waanders and Shaffer2005).

Parent–child relationship quality and parent attachment-related behaviors may be an important moderator of the relation between parent ACEs and children's social–emotional development. In particular, a positive parent–child relationship may serve to buffer children from the negative impacts of parent, family, or other sources of adversity, keeping the stress response in the “normative” or “tolerable” as opposed to “toxic” range (Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwan, Reference Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen2009). Research has found that when parents are highly sensitive and responsive to their children's needs, children are less likely to demonstrate poor outcomes, even in the context of family stress and parental mental illness (Belsky & Fearon, Reference Belsky and Fearon2002; Milan, Snow, & Belay, Reference Milan, Snow and Belay2009).

Currently there are few studies in the research literature that address adversity and early childhood development in AIAN communities. Among the few, Sarche, Croy, Big Crow, Mitchell, and Spicer (Reference Sarche, Croy, Big Crow, Mitchell and Spicer2009) found that parents in one AI community sample reported greater social–emotional problems among their children relative to their nonnative peers. They also found that parent stress and substance abuse were associated with greater social–emotional concerns whereas parent cultural identity and social support were associated with fewer. Frankel et al. (Reference Frankel, Croy, Kubicek, Emde, Mitchell and Spicer2014) also found greater levels of maternal-rated child social–emotional concerns relative to data from another AI community sample, and that maternal social isolation and depressive symptoms were significant predictors of these concerns. Currently, there are no studies of the relation of parent ACEs to children's early social–emotional development in AIAN communities, nor the mechanisms by or conditions under which such intergenerational impacts might occur.

Emotional Availability as an Indicator of Parent–Child Relationship Quality

Emotional availability (EA) is the capacity of an adult–child dyad to share a healthy emotional connection (Biringen, Derscheid, Vliegen, Closson, & Easterbrooks, Reference Biringen, Derscheid, Vliegen, Closson and Easterbrooks2014). While EA is rooted in attachment theory (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969, Reference Bowlby1980), it also expands on attachment theory by emphasizing the importance of emotional expression and the bidirectional quality of the adult–child interaction (Biringen et al., Reference Biringen, Derscheid, Vliegen, Closson and Easterbrooks2014). Thus, high EA is not merely the presence of a secure attachment but also includes positive emotional expression and effective dyadic emotional regulation (Biringen et al., Reference Biringen, Derscheid, Vliegen, Closson and Easterbrooks2014; Saunders, 2016).

EA is assessed through the EA Scales and the Emotional Attachment Zones Evaluation (EA-Z; previously called Emotional Attachment and Emotional Availability Clinical Screener; Baker & Biringen, Reference Baker and Biringen2012; Biringen, Reference Biringen2008; Saunders & Biringen, Reference Saunders and Biringen2017). The EA Scales assess six dimensions, including four for the adult that include sensitivity, structuring, nonintrusiveness, and nonhostility, and two for the child that include responsiveness and involvement. The EA-Z is used with the EA Scales, and provides an overall summary of parent–child relationship quality, particularly attachment-related behaviors, for the adult and child. Specifically, the EA-Z is used to summarize the parent and child sides of the EA Scales, and ranges from high emotional availability (at 100) to complicated emotional availability, to detached emotional availability, and emotional unavailability/problematic (at 1).

An extensive body of literature has utilized the EA Scales and the EA-Z to measure the emotional health of an adult–child relationship (see review by Biringen et al., Reference Biringen, Derscheid, Vliegen, Closson and Easterbrooks2014). High EA is positively associated with several measures of child functioning, including attachment security, (Altenhofen, Clyman, Little, Baker, & Biringen, Reference Altenhofen, Clyman, Little, Baker and Biringen2013; Easterbrooks, Biesecker, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Easterbrooks, Biesecker and Lyons-Ruth2000), emotion regulation (Little & Carter, Reference Little and Carter2005; Martins, Soares, Martins, Terenod, & Osóriof Reference Martins, Soares, Martins, Terenod and Osóriof2012), compliance (Lehman, Setier, Guidash, & Wanna, Reference Lehman, Steier, Guidash and Wanna2002), adaptive stress regulation (Kertes et al., Reference Kertes, Donzella, Talge, Garvin, van Ryzin and Gunnar2009), and infant sleep patterns (Teti, Kim, Mayer, & Countermine, Reference Teti, Kim, Mayer and Countermine2010). Moreover, the EA-Z also corresponds in expected ways with measures of attachment security (Baker & Biringen, Reference Baker and Biringen2012; Saunders & Biringen, Reference Saunders and Biringen2017), as well as clinician ratings on the Parent–Infant Ratings Global Assessment Scale (Espinet et al., Reference Espinet, Jeong, Motz, Racine, Major and Pepler2013; ZERO TO THREE, 2005).

Healthy parent–child relationships, such as those measured by the EA Scales and the EA-Z, may be able to buffer young children against the negative effects of family adversity. Specifically, when a parent is highly sensitive and fosters a secure attachment bond, children are less likely to demonstrate poor outcomes, even in the context of family stress and parental mental illness (Belsky & Fearon, Reference Belsky and Fearon2002; Milan et al., Reference Milan, Snow and Belay2009). In contrast, some parents who have experienced adversity may be unresolved in their state of mind with respect to that adversity, which can, in turn, contribute to lower parental sensitivity and poorer child social–emotional functioning (George, Kaplan, & Main, Reference George, Kaplan and Main1996; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Moran, Pederson and Benoit2006). We are not aware of any studies in the research literature that have examined observed parent–child relationship quality in early childhood and its relationship to children's development in the context of adversity, or otherwise, within an AIAN community.

Summary and Present Study

Despite a significant body of literature on the long-term effects of early adversity on individual health, few studies have examined how parents’ ACEs relate to their children's functioning, or the mechanisms by which this effect may occur. This question is particularly important to examine in AIAN communities, where individuals may be more likely to experience early adversity (Sarche & Spicer, Reference Sarche and Spicer2008).

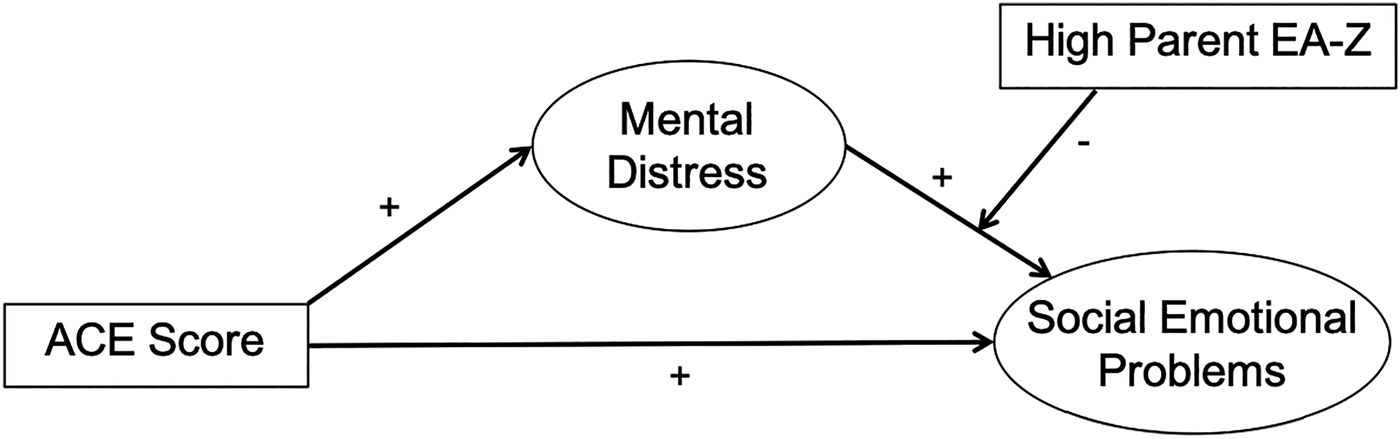

The present study examined how parents’ ACEs related to their current mental distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, and parent-related stress) and their children's social–emotional functioning in a sample of parent–child dyads, the majority of whom were AIAN, attending EHS in an AI community. In addition, emotional availability, summarized as parent EA-Z (Biringen, Reference Biringen2008; Biringen, Robinson, & Emde, Reference Biringen, Robinson and Emde1998; Saunders & Biringen, Reference Saunders and Biringen2017) was examined as a moderator of this pathway. Two models, as depicted in Figures 1 and 2, were explored. The first model predicted that greater parent ACEs would relate to greater mental distress, which, in turn, would relate to poorer child social–emotional functioning. The second model examined whether high or low parent EA-Z moderated the relation between parent mental distress and child social–emotional functioning.

Figure 1. Model 1: Testing the indirect effect of mental distress on the relation between ACEs and child social emotional problems.

Figure 2. Model 2: Indirect effect model with high emotional availability (EA) included as a moderator.

Method

Analyses relied on data gathered as part of a university–EHS research partnership. Protocols for the university and AI community institutional review boards’ review and approval were followed.

Participants

Participants were 100 parent–child dyads living in a semirural Southern plains AI community and enrolled in EHS. Parents age 16 and over were recruited when their child was within approximately 4 weeks of reaching a targeted study baseline window of 10–24 months old, a window that allowed for children to age into an appropriate window for a planned subsequent intervention phase of the study. Parents were recruited in person and enrolled in the study with their child following an informed consent procedure. Parents with two children in the targeted age range were permitted to participate with both. For the three parents with two children in the study, only data from participation with the first child were included in the current analyses to exclude potential bias, fatigue, or practice effects.

The majority of parents (84%) identified as the biological mother of the participating child. For simplicity, we refer to all as “parents,” despite some diversity in relationships. More than half of children were boys (56%), and fewer than half were girls (44%). Parents averaged 26.44 years old (SD = 7.6), and children averaged 16.68 months old (SD = 4.59). A majority of parents (63%) and children (82%) were AI based on parent report. Most who reported being AI indicated local tribal membership. Additional demographic information is reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Parent demographic information

Procedures

Procedures included parent surveys and parent–child video-recorded play sessions. Parents completed a self-report survey that included measures of family demographics, parent ACEs, and current mental health as well as a parent-report child survey that included measures of children's social–emotional functioning and parenting-related distress. Parents and their child participated in the video-recorded play sessions, which consisted of three segments (30 min total) filmed in a room in the EHS center designed to resemble a home environment. The three segments included a semistructured playtime (25 min), a separation and reunion episode (1–2 min), and a cleanup time (3–4 min). During the semistructured playtime, parents were instructed to “be with your child as if you were at home.” Parent–child pairs were then filmed while interacting with one another and the available play materials (e.g., scarves for peek-a-boo, a toy snake, stackable plastic cups, bubbles, a jack-in-the box, and magazines for parent interest). Filming continued while the parent was then asked to leave the room and return after a few minutes and then when, at last, the parent and child were instructed to clean up the toys together. Filming concluded after the cleanup time. The EA video-recorded sessions were later coded for EA (Biringen, Reference Biringen2008; Biringen et al., Reference Biringen, Robinson and Emde1998).

Measures

ACEs

ACEs (CDC, 2016; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998) were assessed with a 10-item self-report survey that asked participants to answer yes or no to questions about their first 18 years of life (Table 2). Questions addressed adverse experiences, including abuse (emotional/verbal, physical, and sexual), neglect (emotional and physical), and family hardship (parents divorced/separated, mother treated violently, substance abuse in the home, mental illness/suicide in the home, and household member in prison). ACE scores were calculated by adding the total number of yes responses for each individual. Out of the full sample of 100 participants, 89 completed the ACE survey. The predictive validity of the ACE survey has been established; it predicts mental illness (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Holden, Felitti and Anda2003) and poorer physical health in adulthood (Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998).

Table 2. EA-Z scores and zones

a Ainsworth et al., 1978; Main & Solomon, Reference Main, Solomon, Brazelton and Yogman1986.

Parent mental distress

Parental mental distress was operationalized as a latent variable composed of the Parenting Stress Index, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale.

<H4> Parenting-related stress. The short form of the Parenting Stress Index, 3rd edition (PSI-SF; Abidin, Reference Abidin1995) is a parent-report measure consisting of 36 items that ask about parenting stress. Items are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). For example, one item reads “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent.” The PSI-SF yields a total score and scores for three subdomains. The parent distress subdomain was used in the current analyses. Parent distress assesses the degree to which a parent feels depressed, incompetent, restricted, conflicted, and/or unsupported in the role of parent. Previous studies have demonstrated the convergent validity of the PSI-SF through observations of parent–child interactions and the child's attachment style (Abidin, Reference Abidin1995; Hasket, Ahern, Ward, & Allaire, Reference Hasket, Ahern, Ward and Allaire2006). The PSI-SF has also been shown to correlate with measures of child behavior a year later, demonstrating its predictive validity (Hasket et al., Reference Hasket, Ahern, Ward and Allaire2006). The PSI-SF has been used in other studies with AIAN participants and demonstrated meaningful relations with child social–emotional outcomes (Sarche et al., Reference Sarche, Croy, Big Crow, Mitchell and Spicer2009). Ninety participants completed the PSI-SF, and internal consistency, assessed using Cronbach's α, was α = 0.94.

Depression

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977) is a 20-item self-report scale that assesses depressive symptoms. Participants respond to each item by marking the frequency with which they experienced the symptom during the past week. Responses range from 0 (rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]) to 3 (most or all of the time [5–7 days]). The CES-D is widely used and has been established as a valid and reliable measure of depressive symptomatology in both community samples and AIAN samples (Eaton, Muntaner, Smith, Tien, & Ybarra, Reference Eaton, Muntaner, Smith, Tien, Ybarra and Maruish2004; Orme, Reis, & Herz, Reference Orme, Reis and Herz1986; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977; Whitbeck, McMorris, Hoyt, Stubben, & LaFromboise, Reference Whitbeck, McMorris, Hoyt, Stubben and LaFramboise2002). Ninety-four out of 100 participants completed the CES-D, and internal consistency, assessed with Cronbach's α, was α = 0.69.

Anxiety

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) measures the frequency of self-reported anxious feelings that are associated with generalized anxiety disorder. Each of the seven items describes a symptom, and items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day). Participants completed this survey regarding symptoms in the last 2 weeks. The GAD-7 has been validated in large samples, showing strong associations with anxiety-related functional impairment (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). Seventy-three participants completed the GAD-7, and internal consistency, assessed using Cronbach's α, was α = 0.90.

Child social–emotional functioning

The Infant Toddler Social–Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, Reference Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones and Little2003) is a parent-report measure of children's social–emotional functioning. It consists of 166 items that assess four domains: competence (empathy, motivation, prosocial peer relations, mastery motivation, compliance, attention, and imitation/play), internalizing (separation distress, inhibition to novelty, general anxiety, and depression/ withdrawal), externalizing (peer aggression, aggression/defiance, and activity/impulsivity), and dysregulation (emotional reactivity, sleep problems, eating problems, and sensory sensitivity). Parents rate the frequency of child behaviors on a 3-point scale from 0 (not true/rarely) to 2 (very true/often). Parents have the option to select “no opportunity” if they have not had the chance to observe the behavior in their child.

Results from a large, ethnically and economically diverse sample demonstrated internal consistency for domains ranging from 0.80 to 0.90, and test–retest reliability on domains ranged from 0.82 to 0.90 (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones and Little2003). Internal consistency in another AIAN community sample on the ITSEA domains ranged from α = 0.62 to 0.88 (Sarche et al., Reference Sarche, Croy, Big Crow, Mitchell and Spicer2009). In this study, data were entered using scoring software that only exported subscale and domain-level scores, so it was not possible to compute Cronbach's α from individual items for each domain. Considering this limitation, domain-level Cronbach's αs were computed based on subscale scores, and they ranged from 0.66 to 0.83. Criterion validity is supported by meaningful correlations with other parent-report and observational measures of child social–emotional functioning (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones and Little2003).

Parent–child relationship quality

The EA Scales and the EA-Z (4th edition; Biringen, Reference Biringen2008; Saunders & Biringen, Reference Saunders and Biringen2017) were used to assess parent–child relationship quality based on coding of the video-recorded play sessions described previously. The EA Scales consist of four adult (parent) dimensions, sensitivity, structuring, nonintrusiveness, and nonhostility, and two child dimensions, child responsiveness and child involvement. Each of the EA dimensions is coded on a 7-point scale from 1 (nonoptimal) to 7 (optimal). The EA-Z provides a summary relationship quality, with a special focus on attachment-related qualities and behaviors (Baker & Biringen, 2008; Biringen, Reference Biringen2008; Saunders & Biringen, Reference Saunders and Biringen2017). The EA-Z relies heavily on information from the EA Scales, and results in both a categorical “attachment zone” and a continuous score. The attachment zones are intended to correspond broadly to each of the four styles identified by Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, and Wall (Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) and Main and Solomon (Reference Main, Solomon, Brazelton and Yogman1986). They are emotionally available (secure), complicated (insecure–anxious/resistant), detached (insecure–avoidant), and problematic/traumatized (insecure–disorganized). For example, children who appear shutdown emotionally and do not turn to their parent for comfort in times of distress are coded in the “detached” zone.

Next, continuous EA-Z scores range from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating more optimal attachment behaviors and greater attachment security. EA-Z continuous scores correspond to the four EA-Z zones (see Table 2). In arriving at parent EA-Z scores, coders consider the sensitivity dimension of the EA Scales, as well as other EA dimensions (e.g., nonhostility and nonintrusivness), as appropriate. For the child, coders consider the responsiveness dimension of the EA Scales as well as the child involvement dimension. The EA-Z and the EA Scales, especially sensitivity and child responsiveness, correlate moderately with measures of attachment security (Saunders & Biringen, Reference Saunders and Biringen2017).

In the current study, each video was double-coded for the EA Scales and the EA-Z continuous and zone scores by two coders trained and certified as reliable by the developer of the EA system (Biringen, Reference Biringen2005). Interrater reliability of at least .80 was maintained for direct and total scores on each EA Scales dimension, as well as for EA-Z scores. The reliability and validity of these scales have been demonstrated in a variety of cultures, caregiver contexts, and child age ranges (for more detail, see review by Biringen et al., Reference Biringen, Derscheid, Vliegen, Closson and Easterbrooks2014). This is the first study to use the EA Scales and the EA-Z with AI families.

Analytic plan

Preliminary analyses were conducted in SPSS, and path analyses were examined using structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). In SEM, multiple indicators can contribute to constructs, and random error does not inform latent variables because it is modeled as residuals (Little, Reference Little2013). Both models (see Figures 1 and 2 above) were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR). MLR estimates missing data for latent and outcome variables. This method also estimates both standardized and unstandardized coefficients and is robust to nonnormal data (Klein & Moosbrugger, Reference Klein and Moosbrugger2000; Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). With MLR, 86 cases were estimated in the first model, and 83 cases were estimated in the second. Six participants were missing data on all variables; 5 were missing data on the ACEs measure; and 8 were missing video-recorded play sessions so could not be coded for EA-Z. In addition, models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation with bootstrapped confidence intervals, which provides accurate inferential tests for indirect effects (MacKinnon, Reference MacKinnon2008).

A mediation/indirect effect model was examined (Model 1) in which ACEs predicted child ITSEA problem domains, mediated by a latent variable of parent mental distress (i.e., CES-D depression, GAD-7 anxiety, and PSI parent distress). Next, we dichotomized the parent EA-Z continuous score into high (n = 25 parents) and low (n = 56 parents) in order to examine EA as a potential moderator of this pathway (Model 2). High parent EA-Z was defined as a score of 81 or higher, or the emotionally available zone. Low parent EA-Z was defined as a score of 80 and below and included the three lowest EA-Z zones (complicated, detached, and problematic/ traumatized). The EA-Z was chosen based on predictions from theory and prior research that parent–child relationship quality would serve as a moderator (e.g., Milan et al., Reference Milan, Snow and Belay2009), and was modeled as categorical in order to distinguish high parent–child relationship quality (i.e., emotionally available) from low (i.e., complicated, detached, or problematic/traumatized).

Results

Preliminary analyses

AI parents (n = 65) were compared to non-AI parents on key variables in order to determine whether their risk profiles were substantially different. Independent samples t tests using Bonferroni's correction (k = 7) tested whether AI and non-AI participants differed on number of ACEs, PSI scores, CES-D total score, GAD-7 score, education level, their children's ITSEA domain scores, and EA direct scores. AI participants and non-AI participants did not differ significantly on any of these key variables. The proportion of parents who offered full data was 72% AI, indicating that missing data also did not systematically differ by AI versus non-AI. Because the overall profile of AI participants was not substantially different than that of non-AI participants, results are reported for the sample as a whole.

Prevalence of ACEs

Next, we examined the overall prevalence of ACEs (see Table 3). The mean ACE score in the overall sample was M = 2.04 (SD = 2.49). Among parents with a low EA-Z score (80 and lower, n = 56), mean ACE score was M = 2.20 (SD = 2.69), and among parents with a high EA-Z score (81 and higher, n = 25), mean ACE score was M = 1.68 (SD = 2.14). These means were not significantly different.

Table 3. Adverse childhood experiences in full sample (N = 89)

Table 4 displays bivariate correlations among key variables. Bivariate correlations showed expected relations among our variables of interest, so we proceeded with path analyses. We examined the fit of the first model (see Figure 1), in which parent ACE score related to child ITSEA domains, mediated by parent mental distress, as well as the fit of the second model (see Figure 2), which added parent EA-Z as a moderator. Results and model fits are discussed below.

Table 4. ACEs, parent mental distress, child social–emotional functioning, and EA-Z (N = 94)

a Ranges from some 3 (high school) to 13 (master's degree). GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale. CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. PSI, Parenting Stress Index. ITSEA, Infant Toddler Social–Emotional Assessment. *p < .05. ** p < .01.

Path analyses

Model 1: Mediation of ACEs via mental distress

In Model 1, we predicted that the effect of parent ACEs on child social–emotional functioning would be mediated through parent mental distress. Temporal precedence (Cole & Maxwell, Reference Cole and Maxwell2003; MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, Reference MacKinnon, Fairchild and Fritz2007) was partially established. In theory, ACEs occurred prior to all other variables (i.e., during the parent childhood), but parent mental distress and child social–emotional functioning were reported at the same time. This limitation is discussed further in the Discussion section below.

Before testing Model 1, the measurement model was fit (see Figure 3). The mental distress latent variable was composed of CES-D, GAD-7, and PSI parenting distress total scores. These three indicator variables were rescaled using the percent of maximum score method so that they were on the same scale (Little, Reference Little2013). The ITSEA latent variable was composed of the dysregulation, externalizing, and internalizing domain raw scores, which were already on the same measurement scale.

Figure 3. Measurement model for path analysis from parent ACE score to child ITSEA.

Standardized factor loadings of observed variables onto latent variables were adequate, ranging from .63 for the ITSEA internalizing domain to .89 for the GAD-7. ACE score was correlated with the mental distress latent variable, r = .52, p < .001, and the ITSEA latent variable, r = .29, p = .02. The mental distress and ITSEA latent variables were also significantly related to each other, r = .53, p = .001. Model fit of the measurement model was good, χ2 (12) = 11.09, p = .52, 90% confidence interval (CI) of root mean square error of approximation [.00, .10], comparative fit index = 1.000, Tucker–Lewis index = 1.000.

Next, we examined the path analysis of an indirect effect of parent ACEs on the child ITSEA latent variable via the parent mental distress latent variable (see Figure 4). There was a significant standardized indirect effect of ACEs on ITSEA via mental distress, β = .274, 95% CI [.129, .517], SE = .10, p = .002. The whole model accounted for 27.3% of variance in the mental distress latent variable and 51.4% of variance in the ITSEA latent variable. Further, the ratio between the indirect and direct effect was 1.02, which means that the indirect accounted for more variance than the direct effect (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013).

Figure 4. Testing Model 1: Indirect effect of parent ACEs on child ITSEA via parent mental distress.

Model 2: EA-Z as a moderator

In Model 2, we predicted that the path from ACEs to mental distress to ITSEA would be moderated by low EA versus high EA. Thus, Model 1 was rerun grouped by low (80 and lower) and high (81 and higher) parent EA-Z score. As described earlier, categorizing EA-Z by high versus low was chosen on theoretical grounds. In addition, bivariate correlations showed that the continuous EA-Z scores were not related to any of the variables in the path analysis. Furthermore, when moderation models using continuous EA-Z scores were tested in SEM, they were not significant.

The measurement model was first fit for each of the EA-Z groups (see Figures 5 and 6). Within the low EA-Z group (n = 56), standardized factor loadings of observed variables onto latent variables were adequate (see Figure 5). ACE score was significantly correlated with the mental distress latent variable, r = .54, p < .001, and the ITSEA latent variable, r = .61, p < .001. The mental distress and ITSEA latent variables were also significantly related to each other, r = .76, p < .001. Within the high EA-Z group (n = 25), standardized factor loadings were also adequate (see Figure 6). ACE score was not significantly correlated with the mental distress latent variable, r = .37, p = .08, or the ITSEA latent variable, r = .37, p = .14. Mental distress was also not related to ITSEA, r = .29, p = .38. Model fit of the overall measurement model, which included both groups, was adequate, χ2 (32) = 34.20, p = .56, root mean square error of approximation = .00, 90% CI [.00, .11], comparative fit index = 1.000, Tucker–Lewis index = 1.014.

Figure 5. Measurement model for low EA-Z group.

Figure 6. Measurement model for high EA-Z group.

Next, the path analysis was run for each of the EA-Z groups (see Figures 7 and 8). In the low EA-Z group, the standardized indirect effect was significant, β = .121, 95% CI [.118, .623], SE = .05, p = .01. The model accounted for 29.4% of variance in the mental distress latent variable and 61.7% of variance in the ITSEA latent variable. In the high EA-Z group, the standardized indirect effect was not significant, β = .031, 95% CI [–.539, .907], SE = .16, p = .849. When the same model was run comparing groups based on child EA-Z, similar results were found.

Figure 7. Model 2: Path analysis for low EA-Z group.

Figure 8. Model 2: Path analysis for high EA-Z group.

Discussion

Path analyses

The first model that was tested predicted that greater parent ACEs would relate to greater symptoms of parent mental distress, which in turn would relate to poorer child social–emotional functioning. This mediated model was supported. The second model that was tested predicted that the quality of the parent–child relationship as measured by parent high versus low EA-Z would moderate this pathway and was also supported. In particular, among the high EA-Z participants, relations among key variables (ACEs, mental distress, and ITSEA) were no longer significant, whereas among the low EA-Z participants, the pathway remained significant.

The association of higher parent ACE scores with greater symptoms of depression, anxiety, and parenting-related distress (i.e., parent mental distress) is consistent with prior research demonstrating the association of ACEs with subsequent mental health problems in AIAN and non-AIAN populations (Brockie et al., Reference Brockie, Dana-Sacco, Wallen, Wilcox and Campbell2015; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Holden, Felitti and Anda2003; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998). The association of higher parent ACE scores with more social–emotional problems among children is also consistent with previous research (Brown & Ash, Reference Brown, Ash and Brown2017; McDonnell & Valentino, Reference McDonnell and Valentino2016; Narayan et al., Reference Narayan, Kalstabakken, Labella, Nerenberg, Monn and Masten2017; Schleuter et al., Reference Schleuter, Mendoza, Hurwich-Reiss, Barrow, Fisher, Watamura and Brown2017).

Findings from the current study add to our understanding of parent ACEs and child social emotional functioning in AIAN communities as well as other populations. First, the fact that AI and non-AI parents did not differ significantly in their ACE scores suggests that the higher rate of ACEs in the current sample relative to national non-Native samples may reflect a broader, community-level disparity in ACEs regardless of race. Second, the critical mediating role parent mental distress and the moderating role of relationship quality were highlighted. In particular, this study added to our understanding of the pathway by which parent childhood adversity exerts an intergenerational effect (i.e., through parent mental distress, a latent variable that consisted of parent depression, anxiety, and parenting distress and that this is true in the context of low but not high relationship quality). This study thus adds empirical support to the notion of early caregiving relationships as buffers against the negative effects of stress on children's early development.

These findings highlight the need for basic research and clinical interventions that are focused on preventing early adversity as well as helping individuals who experience early adversity to process their experiences and come to a state of cognitive and emotional resolution as might be suggested by attachment theory (George et al., Reference George, Kaplan and Main1996; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Moran, Pederson and Benoit2006). To this end, clinicians and researchers not only should assess for childhood adversity but also should use evidence-based, culturally sensitive practices (e.g., Dozier, Lindheim, & Ackerman, Reference Dozier, Lindhiem, Ackerman, Berlin, Ziv, Amaya-Jackson and Greenberg2005; Lieberman, Ippen, & Van Horn, Reference Lieberman, Ippen and Van Horn2006) to ameliorate the detrimental effects of such adversity, particularly when working with multiple generations.

Limitations

Several characteristics of this study restrict its internal and external validity. First, data used in the analyses were from a single point in time. As a result, the path analyses testing indirect effects should be interpreted with caution, as causality cannot be established without longitudinal data (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986; Maxwell & Cole, Reference Maxwell and Cole2007). Of note, however, Hayes (Reference Hayes2013) argues that path analyses can be run regardless of study design, given that the hypothesized pathways are based in theory. Nonetheless, it is possible these results reflected dynamic or bidirectional relations among variables. For example, even though the ACE survey asked about events from the past, it is possible that parents’ current mental state impacted their responses, contributing to over- or underreporting due to perceived stigma, lack of memory, or other factors affected by current mental state. In addition, parents reported on both themselves and their children, which may have introduced additional bias.

Second, the small sample size limited the power to detect differences in more advanced analyses. This was particularly true when testing the moderating effect of parent–child relationship quality among the small number of high EA-Z parents. The overall small sample size was compounded by missing data, which limited our ability to test hypotheses using certain measures. For example, the small sample size limited the complexity of the models that could be tested in Mplus.

Third, the internal consistency of the CES-D within this sample was just below what is considered acceptable (Tavakol & Dennick, Reference Tavakol and Dennick2011). This may limit the conclusions that can be drawn from our results, as the CES-D was part of the mental distress latent variable. Prior research has shown strong internal consistency of the CES-D but problems with its dimensional structure in AIAN samples (Manson, Ackerson, Dick, Baron, & Fleming, Reference Manson, Ackerson, Dick, Baron and Fleming1990). Future research should continue to examine whether the CES-D is an appropriate measure of depressive symptoms among AIAN populations, or whether a modification of the CES-D or another tool altogether would be performed better.

A fourth limitation relates to the fact that individuals in AIAN communities face high levels of contextual stress across the life span (Gone & Trimble, Reference Gone and Trimble2012; Sarche & Spicer, Reference Sarche and Spicer2008). It is therefore possible that other ongoing risk factors, such as economic stress, current trauma, or family dynamics, functioned as additional explanatory variables in this sample. However, this study did not examine those factors. Further research can elucidate the processes by which early adversity and other variables impact parent mental health and functioning, particularly in AIAN communities.

Fifth and finally, it is important to note that results from this particular AI community may not generalize to the AIAN population as a whole nor to other specific AIAN communities given the diversity among AIAN groups. Diversity is evident from tribe to tribe, from nation to nation, and between urban and rural AIAN populations. It should be noted, however, that both our sample and the sample studied by Brockie et al. (Reference Brockie, Dana-Sacco, Wallen, Wilcox and Campbell2015) experienced greater ACEs than did the sample in the original ACE study (Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998), suggesting that individuals in AIAN communities may be at greater risk for experiencing ACEs.

Strengths

Despite these limitations, the study's strengths were notable. First, it used both self-report and observational methods. Social science researchers have warned about the dangers of relying solely on self-report measures because participants are likely to respond based on social desirability bias (Cook & Campbell, Reference Cook and Campbell1979). Thus, using both self-report and observational methods may have reduced the bias that can accompany self-report measures.

The explicit measurement of childhood adversity with the Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey was a second strength. Luthar, Cicchetti, and Becker (Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker2000) and Rutter (Reference Rutter2012) have emphasized the importance of directly assessing risk exposure. Without such direct measurement, individuals considered resilient may not actually have been exposed to adversity. Furthermore, the experiences of AIAN individuals are quite diverse (e.g., Koss et al., Reference Koss, Yuan, Dightman, Prince, Polacca, Sanderson and Goldman2003), so even though, as a general population, AIAN individuals may be considered high risk, it is important to directly assess the level of such risk in order to make valid conclusions about its effects. This was particularly important in the current study, where not all participants identified as AIAN. Without directly examining the experience of ACEs, it would have been entirely inappropriate to assume a certain degree of risk among this diverse sample.

Conclusion

Acknowledging the study limitations and strengths, this study was the first to demonstrate relations between parents’ early adversity and the social–emotional functioning of their children in an AI community and the mechanisms that both mediate (i.e., parent mental distress) and moderate (i.e., parent–child relationship quality) these relations. Further, this is one of only a few recent studies to demonstrate a relation between parents’ ACEs and their child's social–emotional functioning in any population (Brown & Ash, Reference Brown, Ash and Brown2017; Schleuter et al., Reference Schleuter, Mendoza, Hurwich-Reiss, Barrow, Fisher, Watamura and Brown2017). Future studies should continue to examine this association, as well additional processes that mediate and moderate it (e.g., adult attachment; George et al., Reference George, Kaplan and Main1996) among larger and more diverse AIAN and other populations using multiple time point in order to replicate and extend these findings. Basic research such as this should then be used to justify and implement evidence-based and culturally sensitive prevention and intervention programs to work on breaking the intergenerational impact of adversity.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Administration for Children and Families for their funding in support of this research project (Grant 90YR0048; Sarche, PI). We also acknowledge the support and helpful feedback of the tribal review board and our Early Head Start partners. Thank you also to all of the research assistants and consultants who have worked on the project, especially Calvin Croy, Lia Closson, and Abby Derr-Moore, as well as to Dr. David MacPhee and Dr. Randall Swaim for their valuable feedback on the master's thesis that led to this paper. Finally, we greatly appreciate the time and commitment of the families and children who participated in the study.