The intergenerational transmission of victimization is commonly described as a dynamic process whereby the experience of victimization across generations is explained by the interplay of transgenerational processes (e.g., parenting) and individual risk factors (e.g., caregiver victimization history; Pears & Capaldi, Reference Pears and Capaldi2001). The examination of such intergenerational cascade models has generally upheld the hypothesis that experiences of victimization permeate generational boundaries, highlighting the critical importance of incorporating caregiver experiences of trauma into understandings of family-wide functioning (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011; Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish, & MacMillan, Reference Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish and MacMillan2018; Widom, Czaja, & Dutton, Reference Widom, Czaja and Dutton2014; Widom & Wilson, Reference Widom and Wilson2015). The experience of victimization has direct negative effects on the health and wellbeing of both caregivers and children, including a heightened risk for psychopathology, low self-esteem, sleep disturbances, hypersensitivity of fear responses, and physical health problems (Breiding et al., Reference Breiding, Smith, Basile, Walters, Chen and Merrick2014; Dillon, Hussain, Loxton, & Rahman, Reference Dillon, Hussain, Loxton and Rahman2013; Evans, Davies, & DiLillo, Reference Evans, Davies and DiLillo2008; Graham-Bermann & Levendosky, Reference Graham-Bermann and Levendosky2011; Howell, Reference Howell2011; Howell, Barnes, Miller, & Graham-Bermann, Reference Howell, Barnes, Miller and Graham-Bermann2016).

This intergenerational transmission of risk places alarming burdens on families across the globe by posing continuous and cyclical threats to high-risk and vulnerable adults and children (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011; Widom et al., Reference Widom, Czaja and Dutton2014; Widom & Wilson, Reference Widom and Wilson2015). Although individual victimization of both caregivers and children exerts within-person direct effects, some studies also demonstrate that victimization of caregivers exerts indirect effects on child functioning via parenting practices (Grasso et al., Reference Grasso, Henry, Kestler, Nieto, Wakschlag and Briggs-Gowan2016; Pears & Capaldi, Reference Pears and Capaldi2001). Despite support for the critical role of parenting in the intergenerational transmission of victimization, there remain several gaps in the research literature. First, models of intergenerational transmission of risk have generally failed to examine competing hypotheses to determine whether the effect of parenting practices on child victimization are best described as direct, indirect (i.e., mediating), or buffering/fomenting (i.e., moderating). Further, models have generally focused on a particular parenting characteristic, most commonly harsh parenting or positive parenting, rather than examining relative influences of multiple types of parenting behaviors. The objective of the current study is to address these gaps in the literature by testing a range of competing models for the intergenerational transmission of risk, including diverse aspects of parenting behavior.

Intergenerational transmission of victimization

Extant research on the intergenerational transmission of victimization between caregivers and children has focused primarily on risk factors, including low socioeconomic status, maternal mental health symptoms and psychopathology, and disrupted attachment (Benavides, Almonte, & de Leon Marquina, Reference Benavides, Almonte and de Leon Marquina2015; Berthelot et al., Reference Berthelot, Ensink, Bernazzani, Normandin, Luyten and Fonagy2015; McCloskey, Reference McCloskey2017). Few studies investigated resilience or protective factors that moderate or buffer children's victimization, but those that have found support for the roles of social competence, fewer parental mental health problems, and positive parenting (Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz, & Lilly, Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010; Jackson, Chou, & Browne, Reference Jackson, Chou and Browne2017). Additionally, studies on pathways of risk and resilience are limited in that they often focus on specific types of victimization or trauma, rather than polyvictimization, more broadly (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Chou and Browne2017). Incorporating broad understanding of types of violence that individuals can experience is critically important in better typifying and understanding their functioning (Hamby & Grych, Reference Hamby and Grych2013). More research is therefore required to analyze risk and resilience pathways with a wide perspective on victimization to provide insight into potential opportunities to foster positive outcomes across generations.

Furthermore, few studies have investigated the intergenerational cascade of victimization in cultures and contexts outside of the United States (Kimber et al., Reference Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish and MacMillan2018). Some international studies demonstrated support for intergenerational transmission of risk, but these studies primarily focused on specific types of victimization (e.g., war-affected contexts, child maltreatment victimization, mass trauma) or emphasized children's mental health symptoms in relation to trauma, rather than analyzing general victimization transmission across generations (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Edwards, Creamer, O'Donnell, Forbes, Felmingham and Van Hooff2018; Catani, Jacob, Schauer, Kohila, & Neuner, Reference Catani, Jacob, Schauer, Kohila and Neuner2008; Saile, Ertl, Neuner, & Catani, Reference Saile, Ertl, Neuner and Catani2014). With potentially different views on violence, societal support systems, and other culturally varying factors, research needs to investigate mechanisms and moderators of the intergenerational transmission of victimization in other cultural contexts (Kimber et al., Reference Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish and MacMillan2018). Given the relevance of culture and context in developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti & Aber, Reference Cicchetti and Aber1998), research on the intergenerational transmission of victimization in novel contexts stands to elucidate potential risk and resilience pathways of this cascade, contributing to our understanding of universal versus context-specific pathways of victimization, violence, and trauma across generations.

Trauma and victimization in Peru

Peruvians report high prevalence rates of violence, victimization, and trauma. Population-based surveys in schools estimate 57–68% of Peruvian children and adolescents report lifetime exposure to psychological violence, 58–65% indicate they have experienced physical violence, and around 35% endorse sexual violence (Ames, Anderson, Martin, Rodriguez, & Potts, Reference Ames, Anderson, Martin, Rodriguez and Potts2018; Fry et al., Reference Fry, Anderson, Hidalgo, Elizalde, Casey, Rodriguez and Fang2016). Additionally, other studies in Peru indicate around 45.1% to 61% of Peruvian women reported they experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) in their lifetimes (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006; Perales et al., Reference Perales, Cripe, Lam, Sanchez, Sanchez and Williams2009). As in other contexts, there is also compelling evidence to suggest the presence of intergenerational cycles of victimization in Peru. One study in Peru found mothers’ history of child abuse and current IPV increased their risk for using physical punishment with their children (Gage & Silvestre, Reference Gage and Silvestre2010). Besides this study, few studies have addressed roles of parenting with children's victimization in Peru. With high rates of potential victimization for adults and children, more research is needed to understand the intergenerational transmission of victimization in Peru from a developmental psychopathology perspective that emphasizes processes and pathways of risk and resilience.

Potential pathways from caregiver to child victimization

Caregivers’ trauma history

One proposed risk pathway is caregiver trauma history. Given extant literature on the intergenerational victimization in American and Peruvian contexts, households with high-risk caregivers, due to prior victimization histories, also include children at heightened risk for their own victimization (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011; Kimber et al., Reference Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish and MacMillan2018; Widom et al., Reference Widom, Czaja and Dutton2014; Widom & Wilson, Reference Widom and Wilson2015). However, most existing research focuses primarily on one type of violence or victimization, such as IPV or child abuse, rather than broad definitions of victimization (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011; Kimber et al., Reference Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish and MacMillan2018). Recent theoretical and empirical work has highlighted the importance of assessing multiple types of victimization across domains to better typify risk pathways, as individuals exposed to one type of violence are disproportionately more likely to experience others (Hamby & Grych, Reference Hamby and Grych2013). Additionally, few studies in Peru analyze polyvictimization from an intergenerational perspective, and existing studies focus primarily on maltreatment from parents and bullying from peers (Benavides Abanto, Jara-Almonte, Stuart, & La Riva, Reference Benavides Abanto, Jara-Almonte, Stuart and La Riva2018).

Caregivers’ depression symptoms

Caregiver depression symptoms have been shown to heighten children's risk for myriad maladaptive outcomes, including psychopathology and behavior problems (Cummings & Davies, Reference Cummings and Davies1994; Villodas, Bagner, & Thompson, Reference Villodas, Bagner and Thompson2018). Research suggests parental depression symptoms may affect children's outcomes through various pathways, such as increased parent–child aggression and lax or inconsistent parenting practices (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011; Cummings & Davies, Reference Cummings and Davies1994; Villodas et al., Reference Villodas, Bagner and Thompson2018). Little research has investigated parental depression symptoms specifically in relation to children's victimization, especially in international contexts, and these mental health symptoms may serve as an important control variable to include with caregivers’ trauma histories and parenting behaviors.

Negative parenting behaviors

Prior studies have found negative parenting practices to heighten children's risk for victimization and mediate the intergenerational transmission of victimization, including IPV, sexual victimization, and peer victimization (Chiesa et al., Reference Chiesa, Kallechey, Harlaar, Ford, Garrido, Betts and Maguire2018; Kokkinos, Reference Kokkinos2013; Lereya, Samara, & Wolke, Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Testa, Hoffman, & Livingston, Reference Testa, Hoffman and Livingston2011). For example, one study demonstrated lower parental monitoring mediated the association between mothers’ sexual victimization and daughters’ sexual victimization (Testa et al., Reference Testa, Hoffman and Livingston2011). A study in Peru found mothers’ prior child abuse and current IPV were associated with physical punishment of children (Gage & Silvestre, Reference Gage and Silvestre2010). This study demonstrates the link between children's victimization with both parental victimization and negative parenting behaviors. Taken together, these studies suggest negative parenting behaviors may be potential risk pathways for children's victimization, especially when caregivers have been previously victimized themselves. Nevertheless, most studies have analyzed negative parenting behaviors as mediating factors towards children's victimization or self-worth outcomes (Chiesa et al., Reference Chiesa, Kallechey, Harlaar, Ford, Garrido, Betts and Maguire2018; Kokkinos, Reference Kokkinos2013; Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Millones, Ghesquière, & Van Leeuwen, Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014b; Testa et al., Reference Testa, Hoffman and Livingston2011), but more research needs to evaluate potential moderating pathways of this transmission (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011).

Further, there is very little empirical research on parenting and family systems in Peru – in either English or Spanish. Psychologists in Peru have described the nuclear family as the core familial unit in Peru, but have noted that extended family networks do appear to confer benefit for child developmental outcomes in this context, and may take on particular importance in the context of socioeconomic disadvantage (Quintana Peña, Reference Quintana Peña2000). Research has described the parenting style in Peru as authoritarian, increasingly so in relation to poverty (Majluf, Reference Majluf1989; Pimentel, Reference Pimentel1988). Previous research on parenting behaviors in Peru has shown that harsh punishment and discipline significantly related to poorer family environment, including lower in-home safety, fewer learning/educational materials, lower parental modeling of prosocial behaviors, lower emphasis on independence, authoritative rule structures, time spent together by the family in enjoyable activities, and lower perceptions of parent–child relationship quality (Millones, Ghesquière, & Van Leeuwen, Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014a). In this study, discipline and harsh punishment were found to be negative parenting behaviors in Peru, insomuch as they were associated with poorer family environment, but further research is needed to evaluate additional processes by which parenting behaviors act as potential risk pathways for children's victimization, especially in light of caregivers’ own victimization.

Positive parenting behaviors

Prior research has found initial support for positive parenting behaviors as protective factors for children, especially in the context of victimization (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010; Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Millones et al., Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014b). It also appears that low levels of positive parenting behaviors may mediate the relationship between caregiver violence exposure and consequent child adjustment problems (Miller-Graff, Nuttall, & Lefever, Reference Miller-Graff, Nuttall and Lefever2018). However, this research has primarily occurred in the United States and has largely focused on children's adjustment outcomes rather than on children's experiences of victimization. More research examining parenting in other cultural contexts, especially in relation to child victimization, is therefore needed (Cowan & Cowan, Reference Cowan and Cowan2002; Parke & Buriel, Reference Parke, Buriel and Eisen-berg1998). Furthermore, research needs to assess specific, positive parenting behaviors as resilience pathways for the intergenerational transmission of victimization by buffering the effects of caregivers’ trauma history because this research may help identify those most at risk or potential opportunities for optimal intervention (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011). If positive parenting can be identified as a promotive factor, intervention programs or policies may be able to enhance these behaviors, thus mitigating the effects of caregivers’ victimization on child risk.

The current study

The current study aims to analyze the roles of caregivers’ trauma history and various parenting behaviors on child victimization. Further, the study will examine competing models of parenting behaviors as mediators or moderators of the relationship between caregiver trauma and child victimization. By advancing understanding of these potential pathways, the current study may serve to highlight prospective opportunities to promote positive trajectories and disrupt the intergenerational transmission of victimization among high-risk caregivers and children in Peru. Specifically, the current study hypothesizes:

1. Controlling for depression symptoms, child age, and child gender, caregivers’ trauma history will relate to child victimization.

2. Positive parenting behaviors (positive parenting, monitoring) will negatively relate to child victimization, while negative parenting behaviors (punishment, discipline) will be positively related.

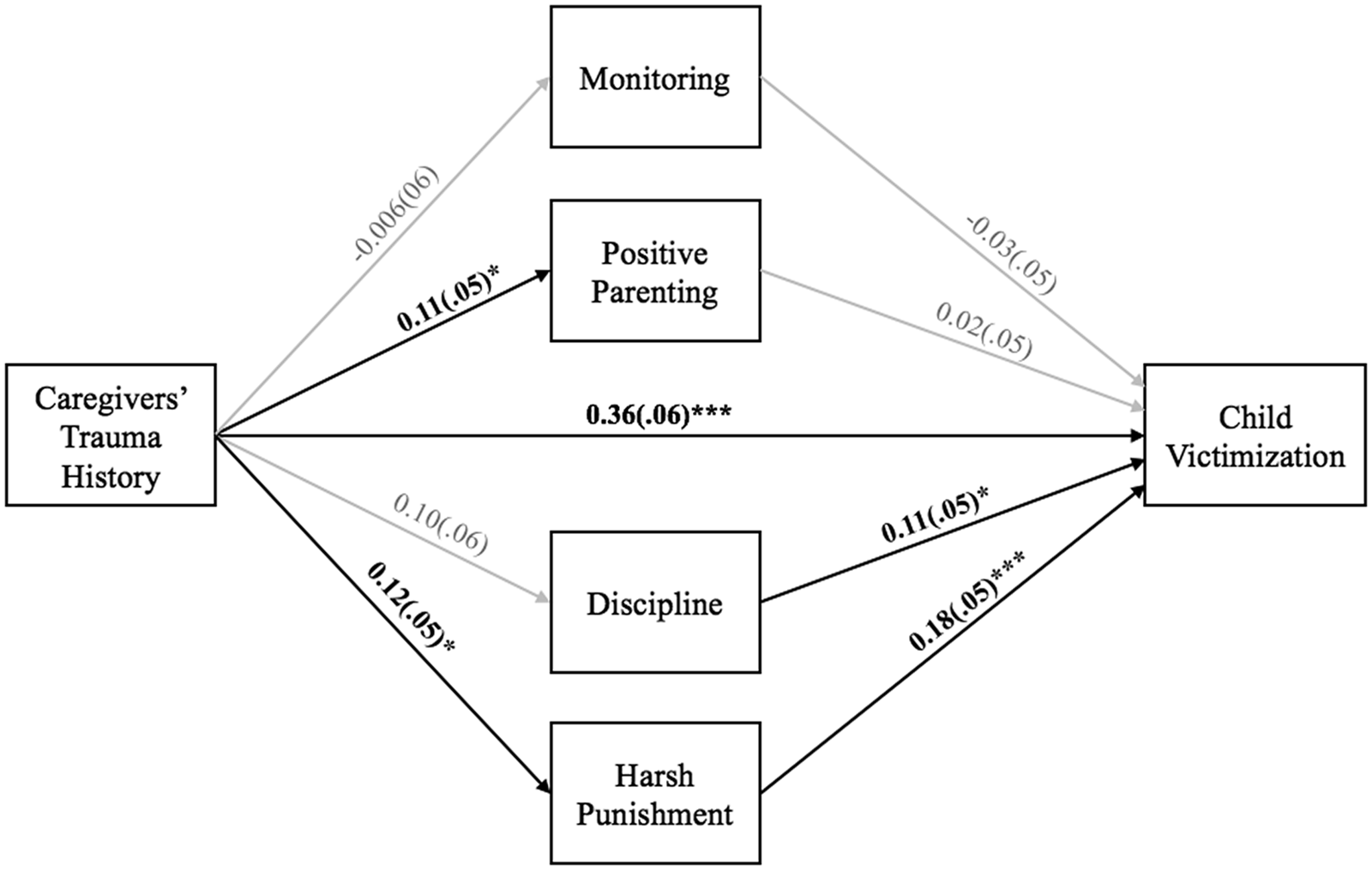

3. It is hypothesized that positive parenting behaviors (positive parenting, monitoring) will significantly mediate the association between caregivers’ trauma history and child victimization, and negative parenting behaviors (punishment, discipline) will also mediate the relation. See Figure 1 for the proposed direct and mediation model.

4. It is hypothesized that positive and negative parenting behaviors will moderate the relation between caregivers’ trauma history and child victimization, such that positive parenting buffers the association and negative parenting exacerbates the relation. See Figure 2 for the proposed moderations.

Figure 1. Proposed direct and mediation model.

Figure 2. Proposed moderation model. Note. *All parenting behaviors (e.g., monitoring, positive parenting, discipline, and harsh punishment) are included in separate, moderating models.

Method

Participants

Participants included caregiver-child dyads drawn from N = 402 households in a representative neighborhood study conducted in San Juan de Lurigancho District in Lima, Peru. San Juan de Lurigancho is a neighborhood located in the urban zone of Canto Grande in the Lima district of Peru. The population of San Juan de Lurigancho is approximately one million, making it one of the most populous areas of Lima. San Juan de Lurigancho experiences numerous development challenges, including problems with infrastructure and housing (e.g., sanitation), high levels of poverty, high rates of crime and victimization, and historically high levels of gang activity (Ciudad Nuestra, 2012; Development Progress, 2015; United Nations High Commission on Refugees, 2017). It is considered one of Lima's most dangerous neighborhoods (Ciudad Nuestra, 2012). The survey analyzed in the current study was initiated by the Instituto de Pastoral de la Familia (INFAM), a social service organization located in San Juan de Lurigancho that is run by the Holy Cross order of Catholic priests and brothers. The organization provides psychosocial supports and cultural programming to families living in San Juan de Lurigancho. They undertook the survey described here as part of their strategic planning process, with the goal of better understanding the experiences of families in their area in order to inform programming decisions.

The response rate for households declining participation was low, accounting for less than the anticipated 15% of approached families, which is similar to response rates for household surveys on violence (Garcia-Moreno et al., Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006). Primary caregivers were mainly female (91.90%), and their ages ranged from 17 to 82 years (M = 42.00, SD = 13.48). In relation to the children involved in the study, 78.48% of primary caregivers were children's parents, 14.43% were grandparents, 3.04% were siblings, 3.80% were other relatives, and 0.25% were unknown. Participating children ranged in age from 4 to 17 years (M = 11.26, SD = 3.97), with almost equal proportions of boys and girls (52.51% boys, 47.49% girls). Ethnicity in Lima, according to the most recent city census, is composed predominately of Mestizo (70%) and Quechua (17%) individuals, but also Aymara, Afro-Peruvian, White, and other groups; however, ethnicity for this sample was not collected (Lima [City Population], 2017). Among primary caregivers, 27.61% identified as single, and 72.39% reported that they were married and/or cohabitating with a partner.

Procedure

Data were collected with the aim of identifying social service needs in the district, with the goal of improving available services available through local organizations. Institutional Review Board approval for secondary use of these survey data for research purposes was obtained by the University of Notre Dame. The parish survey was a representative sampling of households in the district, as determined by random allocations drawn from a geographic map of the neighborhood. Enumerators visited selected addresses and interviewed the identified head of household as well as one randomly selected caregiver-child dyad per eligible household. These caregiver-child dyads were selected based on demographic information provided by the heads of the households on all members of the residences. Children were considered eligible when they were between the ages of 4 and 17 years, based on the valid administration age range of the measures used. Among households with eligible children, electronic surveys randomly selected one index child per household. This sampling strategy was chosen to minimize survey length and burden on caregivers. Once the index child was selected, interviewers asked who the primary caregiver of the index child was, such that primary caregivers were individuals who provided principal roles in care and parenting of chosen children. Interviewers returned to households later if primary caregivers were unavailable at the initial visit. Caregivers completed measures about parenting, depression symptoms, their own trauma histories, and children's victimization experiences.

Measures

Demographics

To obtain basic demographic information, caregivers were asked various background questions, including age and sex for both caregivers and children, religious affiliation, and other demographic information.

Caregivers’ trauma history

The Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ) is a 16-item questionnaire assessing individuals’ lifetime histories of traumatic exposures (Green, Reference Green and Stamm1996). This measure includes a diverse variety of trauma types, such as physical or sexual trauma, general disaster, and crime-related trauma. On each endorsed item, interviewers recorded frequency, occurrence, and age at the time of the traumatic experience. The THQ was scored by summing all events caregivers reported across their history, ranging from 0–16 events in the current study. In both clinical and nonclinical samples, prior research supports the THQ as a reliable and valid measure (Hooper, Stockton, Krupnick, & Green, Reference Hooper, Stockton, Krupnick and Green2011). The THQ has been translated and successfully used in Spanish-speaking contexts (Heilemann, Lee, & Kury, Reference Heilemann, Lee and Kury2002). Internal consistency was not calculated for this scale because individuals could experience one event without necessarily having experienced another.

Caregivers’ depression symptoms

Caregivers’ depression symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which is a self-report measure evaluating depression symptoms in the prior two weeks (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). For each item, caregivers indicated if they experienced the symptoms “not at all” (0) to “nearly every day” (3). The item of the PHQ-9 assessing self-harm and suicidal ideation was not included in the survey. Therefore, the maximum total score for this study was 24. Prior studies have supported the PHQ-9's validity and reliability (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Löwe, Kroenke, Herzog, & Gräfe, Reference Löwe, Kroenke, Herzog and Gräfe2004; Martin, Rief, Klaiberg, & Braehler, Reference Martin, Rief, Klaiberg and Braehler2006), including the Spanish version in Peruvian samples (Zhong, Gelaye, Fann, Sanchez, & Williams, Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Fann, Sanchez and Williams2014a; Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Rondon, Sánchez, García, Sánchez and Williams2014b). Reliability in the current study is α = .80.

Caregivers’ parenting behaviors

The Parent Behavior Scale (PBS) is a questionnaire assessing parenting behaviors. The current study assessed four of the domains included in the PBS, resulting in a 25-item assessment. These items are based on the theory that observed parent–child interactions are central to determining children's socialization (Patterson, Reference Patterson1982; Van Leeuwen & Vermulst, Reference Van Leeuwen and Vermulst2004; Van Leeuwen & Vermulst, Reference Van Leeuwen and Vermulst2010). On each item, caregivers indicated how often they perform each parenting behavior on a 5-point Likert scale, from “never” to “always.” Subscales include Positive Parenting (e.g., making time for children), Monitoring (e.g., supervising children's activities), Discipline (e.g., punishment after misbehavior), and Harsh Punishment (e.g., using corporal punishment and verbal blames), and subscales were scored as means of caregivers’ reports for items in each category. Notably, the Discipline subscale predominately captures punitive punishment of children, rather than positive reinforcement strategies to shape children's behaviors. Existing research has demonstrated the PBS items, especially Discipline and Harsh Punishment subscales, are related to children's behavior problems and families’ home environments (Millones et al., Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014a). Use of the Spanish version of the PBS for families in Peru has been supported in prior research (Millones et al., Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014a). Reliability in the current study is α = .82.

Children's victimization

The Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ; Youth Lifetime, Reduced Item Version) is a 12-item caregiver-report and lifetime measure assessing a variety of victimization experiences for children, and this measure incorporates information about frequency and severity of victimizations (Finkelhor, Hamby, Ormrod, & Turner, Reference Finkelhor, Hamby, Ormrod and Turner2005). Victimization categories on the JVQ are property crime, physical assault, sexual victimization, peer/sibling victimization, and witnessed/indirect victimization (Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Hamby, Ormrod and Turner2005). This version of the JVQ does not include items asking about physical victimization or punishment from caregivers. Caregivers indicated whether children had experienced the victimization event or not (i.e., “yes” or “no”), and confirmations were summed to yield total victimization scores that could range from 0 to 12. Internal consistency was not calculated for this scale because children could experience one event without necessarily experiencing another (Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Hamby, Ormrod and Turner2005). Although this assessment has not previously been used in Peru, it was reviewed by the survey team and items were determined to be appropriate for the context. The measure was forward translated and discussed by the bilingual team to confirm semantic equivalence across contexts.

Data analytic plan

Path analyses were performed using the structural equation modeling (SEM) functions in STATA 15.1, with child victimization as the dependent variable. Data were missing on child age (1.00%), child gender (1.00%), parenting behaviors (4.23%), child victimization (11.69%), and caregiver trauma (12.69%). Missingness on any given variable was not significantly related to children's age and victimization nor caregivers’ education, age, trauma history, and depression symptoms. Based on these analyses, data were determined to be missing completely at random (MCAR). Extant research has identified full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) as the optimal method for producing unbiased coefficient estimates in these cases (Enders, Reference Enders2010), and was therefore used in the current study.

Due to distributional skew, child victimization was log-transformed. A parallel mediation model was performed with caregivers’ trauma history and all four parenting behaviors in one path model, including caregivers’ depression, child age, and child gender as control variables (Hayes, Reference Hayes2017). Direct and indirect effects of mediation variables were evaluated using the SEM and bootstrapping functions in STATA, using 1000 replications for bootstrapping standard errors; estimates were standardized. Mediation was considered to be present if the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect did not include zero; indirect effects were estimated using the Monte Carlo method. To test moderating effects, interaction terms between trauma and parenting behaviors were added to SEM models without mediation paths, but included caregivers’ trauma, four parenting behaviors, caregivers’ depression, child age, and child gender. Each parenting subscale was added as an interaction term with caregivers’ trauma in four separate SEM analyses. If any of the moderating variables were significant, analyses of marginal means were performed to disentangle roles of interaction terms. In addition to examining coefficients in mediation and moderation models, model effect sizes (i.e., Cohen's ƒ2) were also calculated to determine which models provided the best explanatory power for understanding potential intergenerational pathways of risk and resilience (ƒ2: .02 = small effect; .15 = medium effect; .35 = large effect).

Results

Descriptive statistics

In this sample, caregivers indicated children had about one victimization experience on average (M = 1.26, SD = 1.86) and total scores in this sample ranged from 0 to 9. Descriptive statistics and correlations between children's victimization and other variables of interest are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlation matrix of main study variables

Note: aCorrelations with log-transformed variable. Correlations with child gender are point-biserial. *p < .05; **p < .01;***p < .001.

Main effects from caregivers to child victimization

Caregivers’ depression symptoms, child age, and child gender were included in models as control variables, but only depression symptoms (β = 0.15, SE = 0.05, p < .05; see Table 2) and child age (β = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p < .05; see Table 2) were significant predictors of child victimization. In the first hypothesis, caregivers’ trauma history was proposed as a significant predictor of children's victimization while controlling for aforementioned variables, and this relation was significant (β = 0.36, SE = 0.06, p < .001; see Table 2). Thus, the first hypothesis was supported. Positive parenting behaviors (positive parenting, monitoring) were hypothesized to negatively relate to children's victimization, while negative parenting behaviors (harsh punishment, discipline) were hypothesized to be positively related. This second hypothesis was partially supported; harsh punishment (β = 0.18, SE = 0.05, p < .001; see Table 2) and discipline (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p < .05; see Table 2) positively related to children's victimization, with higher use of punishment and discipline being associated with higher reports of child victimization. In contrast, positive parenting and monitoring were not significantly associated with children's victimization. The second hypothesis was supported for negative parenting behaviors, but not for positive parenting behaviors. See Table 2 for details on these analyses.

Table 2. Direct effects on child victimization

Note: Child victimization is log-transformed. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Parenting behaviors as mediators of intergenerational cycle of victimization

In the third hypothesis, the current study proposed negative parenting behaviors would significantly mediate the association between caregivers’ trauma history and child victimization, and positive parenting behaviors would also serve as mediators. To account for small to moderate correlations between parenting behaviors, parallel mediation was run to include all four mediators in one model, while controlling for caregivers’ depression symptoms, child age, and child gender. The overall model explained a significant portion of the variance in child victimization (R 2 = .30) and demonstrated a large effect size (Cohen's ƒ2 = .43). Caregivers’ trauma history had a significant direct effect on positive parenting behaviors (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p < .05) and harsh punishment (β = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p < .05), but not for monitoring nor discipline. Only discipline (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p < .05) and harsh punishment (β = 0.18, SE = 0.05, p < .001) had significant direct effects on child victimization, so positive parenting behaviors and discipline were not significant mediators between caregivers’ trauma history and child victimization. To test the indirect association of caregivers’ trauma history on child victimization through the mediation path of harsh punishment, the indirect effect was analyzed. The indirect effect of harsh punishment (95% CI [0.002, 0.048]) was significantly different from zero. Thus, the third hypothesis was partially supported because negative parenting behaviors (i.e., harsh punishment) partially mediated the association between caregivers’ trauma history and child victimization. See Table 3 for the parallel mediation model with indirect and direct effects and Figure 3 for the model results.

Figure 3. Results of mediation model. Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. All analyses were performed with caregivers' depression symptoms, child age, and child gender as control variables.

Table 3. Indirect effects on child victimization

Note: aChild victimization was log-transformed. All analyses were performed with caregivers’ depression symptoms, child age, and child gender as control variables. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Parenting behaviors as moderators of intergenerational cycle of victimization

Finally, to test competing moderation models, the fourth hypothesis posited that positive parenting behaviors would buffer the association between caregivers’ trauma history and child victimization, and negative parenting behaviors would exacerbate this association. Interaction terms between each of the four parenting behaviors and caregivers’ trauma history were created and added to individual path models. For all moderation analyses, caregivers’ depression, child age, and child gender were added as covariates, and caregivers’ trauma history and all four parenting behaviors were included as primary predictors. Interaction terms were added to evaluate unique contributions of these moderations as models competing with mediation paths. None of the four parenting behaviors significantly moderated the association between caregivers’ trauma history and child victimization, including positive parenting, monitoring, discipline, and harsh punishment. Thus, the fourth hypothesis was not supported.

Post-hoc analyses: Moderation of family type

To further explore familial and cultural contributions within households, a binary variable of family type was created from caregivers’ reports of being single (e.g., family type = 0) or married and/or cohabitating (e.g., family type = 1). This variable was added as a predictor and interaction term with caregivers’ trauma history and parenting behaviors to determine if associations with child victimization varied by family type in post-hoc analyses, above and beyond mediation path analyses. Family type had a significant direct effect on child victimization (β = -0.71, SE = .25, p < .05), suggesting children of caregivers who identified as single were at heightened risk for victimization. As a moderator, family type did not significantly interact with caregivers’ trauma history, monitoring, discipline, and harsh punishment. However, family type significantly moderated positive parenting in association with child victimization (β = 0.81, SE = .25, p < .05); positive parenting also had a negative direct effect in this model (β = −0.19, SE = .07, p < .05). The addition of family type and the interaction between family type and positive parenting significantly contributed to the effect size of the mediation model (R2 change = .06; p < .05) and demonstrated a large effect size (Cohen's ƒ2 = .56). Simple slopes analyses indicated that both single and married/cohabitating households had significant, negative associations between positive parenting and child victimization at low and moderate levels, but this link was not significantly different from zero for married/cohabitating caregivers who endorsed highest levels of positive parenting (see Figure 4). Thus, positive parenting had a stronger buffering effect for single-caregiver households. See Table 4 and Figure 4 for post-hoc results and marginal means of family type as a moderator of positive parenting.

Figure 4. Post-hoc moderation: 95% confidence intervals for marginal means. Note. Marginal means' analyses are not compatible with SEM functions in STATA, so confidence intervals and Figure 4 are based on analyses from hierarchical regression and listwise deletion (N = 313); patterns of significance for predictors were consistent with the moderation model in SEM analyses.

Table 4. Post-hoc moderation of family type on child victimization

Note: a0 = single caregiver and 1 = married/cohabitating caregiver. Child victimization is log-transformed. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

The current study provides insight into the intergenerational transmission of victimization in Peru, with an emphasis on various parenting behaviors. The overall mediation model of intergenerational factors demonstrated a large effect on child victimization, while the model evaluating the moderating effect of parenting did not indicate significant protective roles of parenting behaviors. Consistent with prior literature, the intergenerational transmission of risk was supported, even when controlling from caregivers’ depression, child age, and child gender (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011; Kimber et al., Reference Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish and MacMillan2018; Pears & Capaldi, Reference Pears and Capaldi2001; Widom et al., Reference Widom, Czaja and Dutton2014; Widom & Wilson, Reference Widom and Wilson2015). This finding indicates that even in the context of a neighborhood with high rates of crime and violence, caregivers’ history of victimization remains a significant risk factor for child victimization.

In this context, positive parenting behaviors were not significantly related to child victimization directly, indirectly or as moderators of risk in primary analyses, which was contrary to expectation and prior literature that identified positive parenting as a protective factor in other contexts (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010; Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Millones et al., Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014b). One possible explanation is that positive parenting behaviors alone are insufficient for protecting children from victimization in this context, or this study was underpowered to address these behaviors in light of other risks. Similar findings have been noted in other high-risk contexts, with researchers suggesting that positive parenting behaviors may fail to sufficiently provide adequate protection in high-risk contexts, as compared to low-risk contexts (e.g., Lee, Reference Lee2012). Future research should therefore examine the possible moderating role of community factors, such as cohesion, disorder, and macro-assessments of community crime as possible factors “competing” with parental protective mechanisms.

In post-hoc analyses, positive parenting and family type interacted in relation to child victimization. Here, positive parenting served as a particularly strong buffering factor in households where caregivers were single. Findings on positive parenting as a buffer of child victimization are consistent with prior research (e.g., Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010; Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Millones et al., Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014b; Tillyer, Ray, & Hinton, Reference Tillyer, Ray and Hinton2018), and findings from this study indicate that positive parenting may be a particular boon for children in households with single caregivers. Prior research also found two-parent households to be protective of offspring victimization exposure (Paat & Markham, Reference Paat and Markham2019; Pereda, Abad, & Guilera, Reference Pereda, Abad and Guilera2016), but this study uniquely contributes the interaction between family type and positive parenting in relation to children's risk in Peruvian households. In conjunction with results from primary analyses, findings may suggest the need to account for family type and positive parenting when considering children's risk for victimization in Lima.

The second and third hypotheses were partially supported because negative parenting behaviors (e.g., harsh punishment) were positively associated with child victimization directly and as mediators of caregivers’ trauma histories, which supports prior studies identifying these negative behaviors as risk factors for child outcomes (Chiesa et al., Reference Chiesa, Kallechey, Harlaar, Ford, Garrido, Betts and Maguire2018; Gage & Silvestre, Reference Gage and Silvestre2010; Kokkinos, Reference Kokkinos2013; Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Maldonado-Molina, Jennings, Tobler, Piquero, & Canino, Reference Maldonado-Molina, Jennings, Tobler, Piquero and Canino2010; Millones et al., Reference Millones, Ghesquière and Van Leeuwen2014b; Testa et al., Reference Testa, Hoffman and Livingston2011). Notably, the child victimization measure did not include questions about caregivers’ physical punishment or maltreatment of children, so these findings do not reflect overlap between corporal punishment and child victimization. These results suggest caregivers who engage in more negative parenting behaviors are more likely to have children who experience victimization. Such negative parenting behaviors may be particularly relevant risk factors for child victimization, even in the context of high levels of community violence and disorder. These data suggest high-risk caregivers with extensive trauma histories may be more likely to engage in negative parenting behaviors, which in turn may relate to child victimization. Although the current study did not support negative parenting behaviors as moderators of the intergenerational transmission of victimization, direct and indirect pathways of negative parenting behaviors highlight the association of these behaviors directly on children and with caregivers’ trauma. These findings are consistent with systematic reviews of parenting intervention literature in high-risk, low-income contexts, which suggests that interventions addressing a diverse array of parenting behaviors are most likely to be effective (Knerr, Gardner, & Cluver, Reference Knerr, Gardner and Cluver2013). Programs and policies specifically addressing the adverse impact of negative parenting behaviors, including corporal punishment and harsh punishment, may therefore be important. Specifically, programs and policies can aim to identify caregivers who have trauma histories and heightened risk for harsh punishment and teach these families positive and effective caregiving behaviors.

Although the current study provides novel contributions to international research on the intergenerational transmission of victimization and parenting, limitations should be noted. The cross-sectional design of this study limits causal inferences, and the analyzed pathways should be further investigated in longitudinal research to be able to make better causal inferences. Another limitation in this sample is the lack of ethnicity information collected from participants; future research should investigate roles of ethnicity, parenting, and victimization in Peru. Furthermore, the current study's measures rely on caregivers’ reports, so future research would benefit from incorporating multi-informant and multi-method data from children's reports and observational data, particularly for parenting. With single reporters, data are limited because caregivers may not be aware of some children's victimization experiences outside of the household, especially for older offspring or for caregivers with low levels of monitoring, so these events may be underreported. Reports from children and other informants (e.g., teachers) may provide additional detail on offspring's experiences. Additionally, caregivers may want to present their parenting strategies in a positive light and/or depression symptoms may relate to negative views on parenting, thus potentially biasing reports of caregiving behaviors. Caregivers’ partners or other individuals in households may affect caregivers’ parenting or children's victimization, so data from these sources may help explain caregivers’ trauma and parenting or children's victimization. Although this study's post-hoc analyses included caregiver marital status in an attempt to capture influences from the greater household structure, future studies should incorporate reports and information from additional household data. In future studies, information from multiple sources may mitigate possible biases or corroborate findings. However, as an initial foray into research on the intergenerational transmission of victimization and parenting in Peru, the current study provides valuable understanding into possible risk and resilience pathways for future research.

Despite limitations of the current study, these analyses may provide critical insight into the intergenerational transmission of victimization through various pathways. Primarily, this study stands to contribute to international and intergenerational research on victimization by amplifying support of the intergenerational transmission of victimization and parenting in an international context, which has been lacking (Cowan & Cowan, Reference Cowan and Cowan2002; Parke & Buriel, Reference Parke, Buriel and Eisen-berg1998). Prior research also acknowledged the need for more research using mediation and moderation models to identify possible intervention opportunities (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Appleyard and Dodge2011), and the current study responds to this gap by incorporating both of these competing models. These analyses provide novel information in documenting the risk and protective factors relevant to Peruvian families’ cascades of victimization across generations. Parenting supports for high-risk families in Peru might be particularly important, especially those focused on the reduction of negative parenting behaviors. Additionally, the current study suggests public policy in Peru may help improve or prevent child victimization by identifying and targeting supports for caregivers with extensive trauma histories. Specifically, policies and programs should aim to recognize caregivers at elevated risk for negative parenting behaviors due to prior trauma and provide services to teach caregivers how to augment positive parenting behaviors and decrease reliance on harsh punishment.

Financial support

Funding for this study was provided by Holy Cross Family Ministries and the Ford Program in Human Development and Solidarity Studies at the University of Notre Dame.