Exposure to maternal perinatal mood disturbance adversely affects children's socioemotional, behavioral, and cognitive development (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014). As well as influencing diverse child outcomes, the effects of exposure to maternal perinatal mood disturbance are remarkably persistent. For example, early exposure to maternal symptoms of depression or anxiety predicts reduced academic achievement and poorer behavioral adjustment in adolescence (e.g., Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Evans, Kounali, Lewis, Heron, Ramchandani and Stein2013). Exposure to fathers’ perinatal mood disturbance also has long-term consequences on child adjustment (for a systematic review, see Sweeney & MacBeth, Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016). Given the complexity of within-family processes that mediate and moderate parental influences on child outcomes (e.g., Cummings, Keller, & Davies, Reference Cummings, Keller and Davies2005) and the steady rise in fathers’ involvement in childcare (Bianchi, Robinson, & Melissa, Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milke2006), a dual focus on the impact of mothers’ and fathers’ well-being on child adjustment is important from scientific and societal perspectives. Early clinical studies showed that paternal psychiatric problems amplify the impact of maternal depression (e.g., Conrad & Hammen Reference Conrad and Hammen1993), but the current study is one of the first community studies to consider the impact of maternal and paternal perinatal mood disturbance on child adjustment in tandem.

Consistent with evidence for assortative mating, mothers and fathers show significant concordance in perinatal mood disturbance (Paulson & Bazemore, Reference Paulson and Bazemore2010), providing a valuable opportunity to investigate buffering effects of partner well-being (e.g., attenuated impact of maternal depressive symptoms in the context of low paternal symptomatology). Pathways between parental depression and child outcomes may also be similar in nature for mothers and fathers. For example, direct genetic effects (Harold, Leve, & Sellers, Reference Harold, Leve and Sellers2017) and indirect effects of marital conflict (Hanington, Heron, Stein, & Ramchandani, Reference Hanington, Heron, Stein and Ramchandani2012) each contribute to associations between child problems and well-being in both mothers and fathers. Rather than reflecting the effects of emotional contagion, the emotional security hypothesis (Davies & Cummings, Reference Davies and Cummings1994) suggests that child well-being is adversely affected by any factor that threatens children's feelings of safety and security. Supporting this hypothesis, meta-analytic data from 146 studies of 5- to 18-year-old children and youths indicates moderate associations between interparental conflict and child adjustment (Buehler et al., Reference Buehler, Anthony, Krishnakumar, Stone, Gerard and Pemberton1997). Meta-analytic evidence from 39 studies points to strong associations between interparental conflict and parenting behavior, supporting the view that there are spillover effects of couple conflict (Krishnakumar & Buehler, Reference Krishnakumar and Buehler2000). Interparental conflict therefore provides a salient example of a family-wide stressor that may mediate associations between parental well-being and child adjustment.

In contrast, biologically mediated effects, such as fetal exposure to stress hormones (Talge, Neal, & Glover, Reference Talge, Neal and Glover2007), are specific to mothers. The meta-analytic finding that associations between child externalizing problems and parental depression weaken with child age for maternal depression but strengthen with child age for paternal depression (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002) also suggests distinct underlying mechanisms. While reduced sensitivity to infant cues and needs appears to mediate the impact of maternal depression on child outcomes (Bernard, Nissim, Vacczro, Harris, & Lindhiem, Reference Bernard, Nissim, Vaccaro, Harris and Lindhiem2018), effects of paternal perinatal mood disturbance may rely on contextual mediators such as marital conflict (Sweeney & MacBeth, Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016). Moreover, in contrast to many potential mediators (e.g., parenting quality) that appear salient in the context of low socioeconomic status (e.g., Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Evans, Kounali, Lewis, Heron, Ramchandani and Stein2013), couple relationship problems are linked with symptoms of depression and lead to adverse child outcomes even in relatively low-risk samples (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Keller and Davies2005).

Similarities and contrasts between parents might also be expected with regard to the specific impact of parental perinatal mood disturbance on internalizing problems (i.e., emotional problems) versus externalizing problems (e.g., hyperactivity and conduct problems). Supporting the developmental psychopathology notion of multifinality (Cicchetti & Rogosch Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996), meta-analytic findings indicate that maternal symptoms of depression show similarly small associations with children's internalizing and externalizing problems (Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002). However, it would be premature to conclude that the mechanisms underpinning these effects of exposure to parental mood disturbance are also nonspecific. For example, while paternal and maternal depression show similar links with externalizing problems, maternal depression appears especially salient for internalizing problems (e.g., Connell & Goodman, Reference Connell and Goodman2002). Unfortunately, with few notable exceptions (e.g., Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, O'Connor, Evans, Heron, Murray and Stein2008), studies of the impact of fathers’ perinatal depressive symptoms have typically not distinguished between internalizing and externalizing problems. It is therefore difficult to establish whether similar or distinct mechanisms underpin associations between poor paternal well-being and children's internalizing and externalizing problems. A further goal of the current study was to address this second gap in the literature.

Perhaps the most striking limitation of existing research concerns the scarcity of studies that include multiple assessments of parental mood disturbance. Reflecting this gap, the meta-analysis conducted by Goodman et al. (Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011) focused on moderation effects of contextual factors (e.g., family income), but did not include sufficient studies with multiple assessments of mood disturbance to enable moderating effects of chronicity of exposure to be examined. Moreover, of the 21 articles reviewed by Sweeney and MacBeth (Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016), only those based on the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (Hanington et al., Reference Hanington, Heron, Stein and Ramchandani2012; Hanington, Ramchandani, & Stein, Reference Hanington, Ramchandani and Stein2010; Ramchandani et al., Reference Ramchandani, O'Connor, Evans, Heron, Murray and Stein2008; Ramchandani, Stein, Evans, & O'Connor, Reference Ramchandani, Stein, Evans and O'Connor2005) included perinatal paternal well-being at more than one time point. As a result, the independence of associations between child outcomes and prenatal versus postnatal paternal well-being remains unclear.

In addition, although some studies have adopted latent growth models to examine how exposure to parental perinatal mood disturbance affects children's developmental trajectories (e.g., Garber et al., Reference Garber, Keiley and Martin2002), no study has yet, to our knowledge, applied latent growth models to investigate how the trajectory of parental mood disturbance contributes to child outcomes. This is important for at least two reasons. First, although studies show associations between fetal exposure to maternal stress and child psychopathology (Talge et al., Reference Talge, Neal and Glover2007), the uniqueness of these associations from effects of postnatal exposure to maternal stress remains underinvestigated (Van Battenburg-Eddes et al., Reference Van Batenburg-Eddes, Brion, Henrichs, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2013). Second, fine-grained temporally sensitive analyses may elucidate mechanisms that have either domain-specific (i.e., on internalizing or externalizing) or parent-specific effects. The current study therefore obtained self-report measures from expectant first-time mothers and fathers who were followed up at three postnatal time points (4, 14, and 24 months), and applied latent growth models to compare the relative salience of prenatal intercepts and postnatal slopes for mothers’ and fathers’ well-being as predictors of both early internalizing and externalizing problems.

In sum, we sought to examine for the first time the relative influence of both mothers’ and fathers’ prenatal and postnatal well-being on children's adjustment at 14 and 24 months of age, controlling for parents’ prior history of poor well-being. Our use of latent growth curve analyses enabled us to examine how changes over time in parental well-being were related to child outcomes, while the inclusion of prenatal measures of parental well-being allowed greater clarity in interpreting associations between parental well-being and child outcomes. Our design enabled us to examine the unique and overlapping influence of both mothers and fathers and to assess the specificity of effects on child outcomes by examining early externalizing and internalizing symptoms in the study children. In addition, we investigated the potential mediating effects of variation in couple relationship quality, assessed via multi-informant measures. In doing so, our study sought to distinguish biological (e.g., fetal exposure to maternal distress as indicated by unique effects of maternal prenatal well-being on child adjustment) and social (e.g., unique effects of interparental conflict on child adjustment) mechanisms underpinning the links between parental well-being and child adjustment in the first 2 years of life.

Method

Participants

We recruited 484 expectant couples attending antenatal clinics, ultrasound scans, and parenting fairs in the East of England, New York State, and the Netherlands. To be eligible participants had to (a) be first-time parents and currently living together (being married was not an inclusion criterion); (b) be expecting delivery of a healthy singleton baby; (c) be planning to speak English (or Dutch) as a primary language with their child; (d) be expecting to live in the area for the next 3 years; and (e) have no disclosed history of severe mental illness (i.e., psychosis or bipolar disorder) or substance misuse. We selected first-time parents to minimize confounding effects of parity and because the transition to parenthood is often perceived as a more significant life event than the arrival of a second child. Ten families were not eligible for follow-up when the infants were 4 months old due to birth complications or having left the country. Of the remaining 474 families, 23 families withdrew and 445 (93.8%) agreed to a home visit when their infants (224 boys, 221 girls) were 4 months old, M Age = 4.26 months, SD = 0.46 months, range: 2.97–6.23 months.

At the next time point, 13 of the 451 remaining families became ineligible for follow-up due to having left the country. Six families withdrew from the study, and 6 families who missed appointments at 4 months took part. Thus, 422 out of 438 eligible families (96.3%) took part when their infants (214 boys, 208 girls) were 14 months old, M Age = 14.42 months, SD = 0.57 months, range: 9.47–18.40 months. At the final time point, 12 of the remaining 438 families became ineligible for follow-up due to having left the country. Sixteen families declined to take part in the home visit, and 10 families returned to the study having missed their previous appointment. Thus, 404 out of 426 eligible families (94.8%) took part when their children (209 boys, 195 girls) were 24 months old, M Age = 24.47 months, SD = 0.78 months, range: 19.43–26.97 months. At the birth of their child, mothers were, on average, 32.24 years old, SD = 3.92 years, range: 21.16–43.76 years, and fathers were 34.07 years old, SD = 4.73 years, range: 23.10–55.95 years. Both mothers and fathers had high levels of educational attainment: 84.3% of mothers and 76.3% of fathers had an undergraduate degree or higher. During the prenatal phase, 76.7% of mothers and 92.8% of fathers were in full-time paid employment.

Procedure

The study protocol was approved by the National Health Service (NHS UK) Research Ethics Committee. Following written consent, expectant parents completed an online questionnaire and in-person interview during the final month of their pregnancy (estimated as 1 month before the due date). Families participated in a 4-month, 14-month, and 24-month questionnaire and home visit. Questionnaires were administered in a fixed order at each time point: demographic questions, General Health Questionnaire, Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, and State–Trait Anxiety Inventory. Mothers and fathers completed the Couple Satisfaction Questionnaire and the Conflict Tactics Scale at 4 months. Mothers and fathers completed the Infant Behavior Questionnaire at 4 months, the Brief Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment at 14 months. Mothers in all three sites and fathers in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire at 24 months.

Measures

Parental well-being

Mothers and fathers completed three questionnaires to record symptoms of anxiety and depression at each time point: the 20-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977), the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli, Gureje and Rutter1997), and the 6-item State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Speilberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg and Jacobs1983). The summed scale items for each measure showed excellent internal consistency in mothers and fathers across all time points of the study (see Table 1). Higher scores on each scale indicated greater levels of symptoms.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Note: IBQ distress, Infant Behavior Questionnaire distress to limitations subscale. BITSEA, Brief Infant and Toddler Socio-Emotional Assessment. SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. CSI16, Couple Satisfaction Index. CTS6, Conflict Tactics Scale. CESD20, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. GHQ12, General Health Questionnaire. STAI6, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory. Ladder, mean rating from Time 2 to Time 4 on Ladder of Subjective Social Standing. Paternal involvement, mean rating of paternal involvement in childcare from Time 2 to Time 4.

Child behavior problems

Prior to the 4-month home visit, mothers and fathers completed the Brief Infant Behavior Questionnaire, a questionnaire suitable for rating 3- to 12-month-old infants’ behavior (Putnam, Helbig, Garstein, Rothbart & Leerkes, Reference Putnam, Helbig, Garstein, Rothbart and Leerkes2014). Parents rated the frequency of behaviors from never (1) to always (7) on 7 items measuring distress to limitations. Items were averaged across mothers and fathers and then summed to create a single score with higher scores indicating greater levels of negative affect and distress. Mothers and fathers completed the Brief Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel, & Cicchetti, Reference Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel and Cicchetti2004) as part of the 14-month questionnaire. The Brief Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment consists of 30 items measuring internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, dysregulation, and behaviors classed as “red flags” (e.g., “does not make eye contact”) and is suitable for rating children aged between 12 and 24 months. Each item was rated as 0 (not true/rarely), 1 (somewhat true/sometimes), or 2 (very true/often). Items were averaged across parents and summed together to create a total problems score. Mothers in all three sites completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Reference Goodman2001) as part of the 24-month questionnaire. Fathers in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands also completed the SDQ. In response to negative feedback from fathers in the New York sample (who worked longer hours than fathers in the UK or Dutch samples) regarding the length of the online questionnaire, only maternal ratings on the SDQ were available for this site. The SDQ consists of 20 items measuring emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems and is suitable for rating children aged between 2 and 4 years (note that it was not possible therefore to administer this measure at 14 months). Each item is rated as 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true), or 2 (certainly true). Where available, items were averaged across mothers and fathers and summed together to create an internalizing score and an externalizing score with higher scores indicating more problems in that domain (Goodman, Lamping, & Ploubidis, Reference Goodman, Lamping and Ploubidis2010). We compared our sample against population norms for British 2- to 3-year-olds on SDQ total difficulty scores (M = 7.3, SD = 5.0; i.e., the sum of internalizing and externalizing scores; Goodman, Reference Goodman2014). Our sample of children had significantly elevated levels of problems on the SDQ, M = 8.90, SD = 3.59, t (363) = 8.53, p < .0001, M Diff = 1.60, 95% confidence interval; CI [1.23, 1.97].

Relationship quality

Mothers and fathers completed the 16-item Couple Satisfaction Index (Funk & Rogge, Reference Funk and Rogge2007) and the 6-item Conflict Tactics Scale (Strauss, Hamby, & Boney-McCoy, Reference Strauss, Hamby and Boney-McCoy1996). In the Couple Satisfaction Index, parents rated their level of agreement to items measuring their overall happiness with their relationship, the extent to which their relationship is rewarding, and the emotions evoked by their relationship. Items were summed together to create a total score for both mothers and fathers. In the 6-item Conflict Tactics Scale, parents reported on the frequency with which they engaged in negative interactions with their partner. Negative items were reverse-scored so that high scores reflected low levels of conflict.

Covariates

Parents also provided information about their highest level of educational attainment during the prenatal phase. At the prenatal visit, parents also reported on whether they had ever been diagnosed with depression or anxiety prior to their pregnancy. At each postnatal phase, parents completed the Ladder of Subjective Social Status (Singh-Manoux, Adler, & Marmot, Reference Singh-Manoux, Adler and Marmot2003) in which their placement on a 10-rung ladder was used to indicate their self-perceived education, income, and employment. We calculated the mean level of perceived social standing for mothers and for fathers across the three postnatal waves. Parental involvement in childcare duties was assessed at each time point using the Who Does What Questionnaire (Cowan & Cowan, Reference Cowan and Cowan1988). Both parents reported on how day-to-day childcare tasks were shared between the respondent and their partner using a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (I do it all) to 9 (My partner does it all). We reverse coded the items for fathers so that a 9 indicated that the father had sole responsibility for a given childcare task. We averaged items within each time point. Maternal and paternal ratings of paternal involvement in childcare activities were strongly correlated at the 4-month, r (372) = .63, 14-month, r (339) = .66, and 24-month, r (298) = .58, visits, all ps < .001. We created a paternal involvement in childcare score using an average of all ratings, α = .82. High scores indicated greater paternal involvement in childcare. While it would have been useful to also covary hours of employment for each parent, this measure was not available across all three sites. Moreover, multi-informant, multi-time point ratings of each parent's involvement in childcare are, one might argue, of more direct relevance to child outcomes.

Results

Analytic strategy

We analyzed the data using a latent variable framework in Mplus (Version 8; Muthen & Muthen, Reference Muthèn and Muthèn2017). We used structural equation modeling to examine relations between variation in initial levels and slopes of parental well-being as well as couple relationship quality with children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms at 24 months (controlling for stability in problem behaviors over time). We used a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors in each of our models to account for the nonnormal distribution of our indicators. We evaluated model fit using three primary criteria: comparative fit index (CFI) > .90, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > .90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .08 (Brown, Reference Brown2015). Table 1 illustrates the extent of missing data on each questionnaire. Missing data were judged to be missing at random (see online-only Supplemental Materials Appendix A). We used a full information approach (where model parameters and standard errors were estimated using all available data) under the assumption that data were missing at random so that all eligible families who participated in the prenatal and at least one follow-up phase (N = 438) were included.

Parental well-being, couple relationship quality, and children's behavior problems

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for each study measure. Note that at the prenatal phase 31.5% of mothers and 19.3% of fathers scored at or above the clinical cutoff (≥3) on the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli, Gureje and Rutter1997). The Supplemental Appendix A contains information about how we constructed the latent variables. Table 2 shows the standardized estimates for the covariances between each of the study variables. We used autoregressive modeling to examine the developmental relations between maternal and paternal well-being intercepts and slopes and children's behavior problems at 4, 14, and 24 months. We controlled for stability in behavior problems over time by regressing the 24-month internalizing and externalizing latent factors onto the 14-month problem behavior latent factor. This 14-month score was in turn regressed onto the 4-month problem behavior latent factor. We regressed each of the behavior problem latent factors and the maternal and paternal latent growth factors onto socioeconomic status, two dummy variables representing country of origin with the United Kingdom as the reference group, paternal involvement in childcare, and child gender (1 = male, 2 = female) to control statistically for the influence of these variables. To examine cross-lagged effects, we regressed the child problem behavior latent factors onto maternal and paternal well-being intercepts and slopes. We also examined the cross-lagged association between 4-month problem behaviors and maternal and paternal well-being slopes. Our model capitalized on the availability of developmental longitudinal data examining the impact of prenatal parental well-being (i.e., the intercepts) on later child outcomes while controlling for stability in children's problem behaviors and parental well-being trajectories in the postnatal period. Our model also examined the impact of child behavior on later parental well-being while controlling for initial levels of parental well-being.

Table 2. Standardized estimates for latent variable covariances

Note: T2 behavior, 4-month problem behavior latent factor score. T3 behavior, 14-month problem behavior latent factor score. T4 internalizing, 24-month internalizing latent factor score. T4 externalizing, 24-month externalizing latent factor score. T2 couple qual, 4-month couple relationship quality latent factor score. SES, socioeconomic status latent factor score. Mat. WB intercept, maternal well-being intercept latent factor score. Mat. WB slope, maternal well-being slope latent factor score. Pat. WB intercept, paternal well-being intercept latent factor score. Pat. WB slope, paternal well-being slope latent factor score. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

This initial model provided an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (117) = 275.882, CFI = .938, TLI = .900, RMSEA = .056, 90% CI [0.047, 0.064]. Table 3 (Model 1) shows the path coefficients for each child outcome in the model. The full output is in online-only Supplemental Table S.2. There was rank-order stability in children's behavior problems across the first 2 years of life such that children with high levels of distress at 4 months were more likely to have high levels of behavior problems at 14 months and high levels of externalizing and internalizing problems at 24 months. Maternal well-being intercepts were uniquely associated with 4-month problem behaviors and 24-month externalizing behaviors. Paternal well-being intercepts were uniquely associated with 14-month behavior problems.

Table 3. Unstandardized and standardized estimates for predictors of child problem behaviors

Note: SES, socioeconomic status latent factor score. Mat. WB intercept, maternal well-being intercept latent factor score. Mat. WB slope, maternal well-being slope latent factor score. Pat. WB intercept, paternal well-being intercept latent factor score. Pat. WB slope, paternal well-being slope latent factor score. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Next, we examined the influence of parental relationship quality in the early postnatal period on children's behavior problems at 4, 14, and 24 months. To this end, we regressed the 14- and 24-month child problem behavior latent factors onto the couple relationship quality latent factor. We included each of the covariates reported in the first model. This model provided an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (64) = 102.442, CFI = .966, TLI = .938, RMSEA = .037, 90% CI [0.023, 0.050]. Table 3 (Model 2) shows the path estimates for each child outcome in the model. The full output is in online-only Supplemental Table S.3. Couple relationship quality at 4 months had a unique effect on 24-month internalizing. Children whose parents’ relationship was characterized by high levels of satisfaction and low levels of conflict in the early postnatal period were less likely to have internalizing problems at 24 months. Couple relationship quality was not related to any other measure of child behavioral problems.

In our final model, we investigated whether couple relationship quality at 4 months mediated the link between initial levels of parental well-being and later child behavioral problems. We regressed problem behavior latent factors onto maternal and paternal well-being intercepts and slopes and 24-month behavior problem latent factors onto 4-month couple relationship quality. We omitted the direct paths between maternal and paternal intercepts and 24-month internalizing as neither path was significant in the earlier model. To control for the influence of postnatal parental well-being, we regressed the 24-month problem behavior latent factors onto both maternal and paternal well-being slopes. We regressed couple relationship quality at 4 months onto parental well-being intercepts to investigate the impact of prenatal well-being on postnatal relationship quality. Parental well-being slopes were in turn regressed onto 4-month couple relationship quality. We controlled for history of depression or anxiety prior to pregnancy, socioeconomic status, country of origin, paternal involvement in childcare, and child gender. Predictor variables and measures within the same time point covaried in the model.

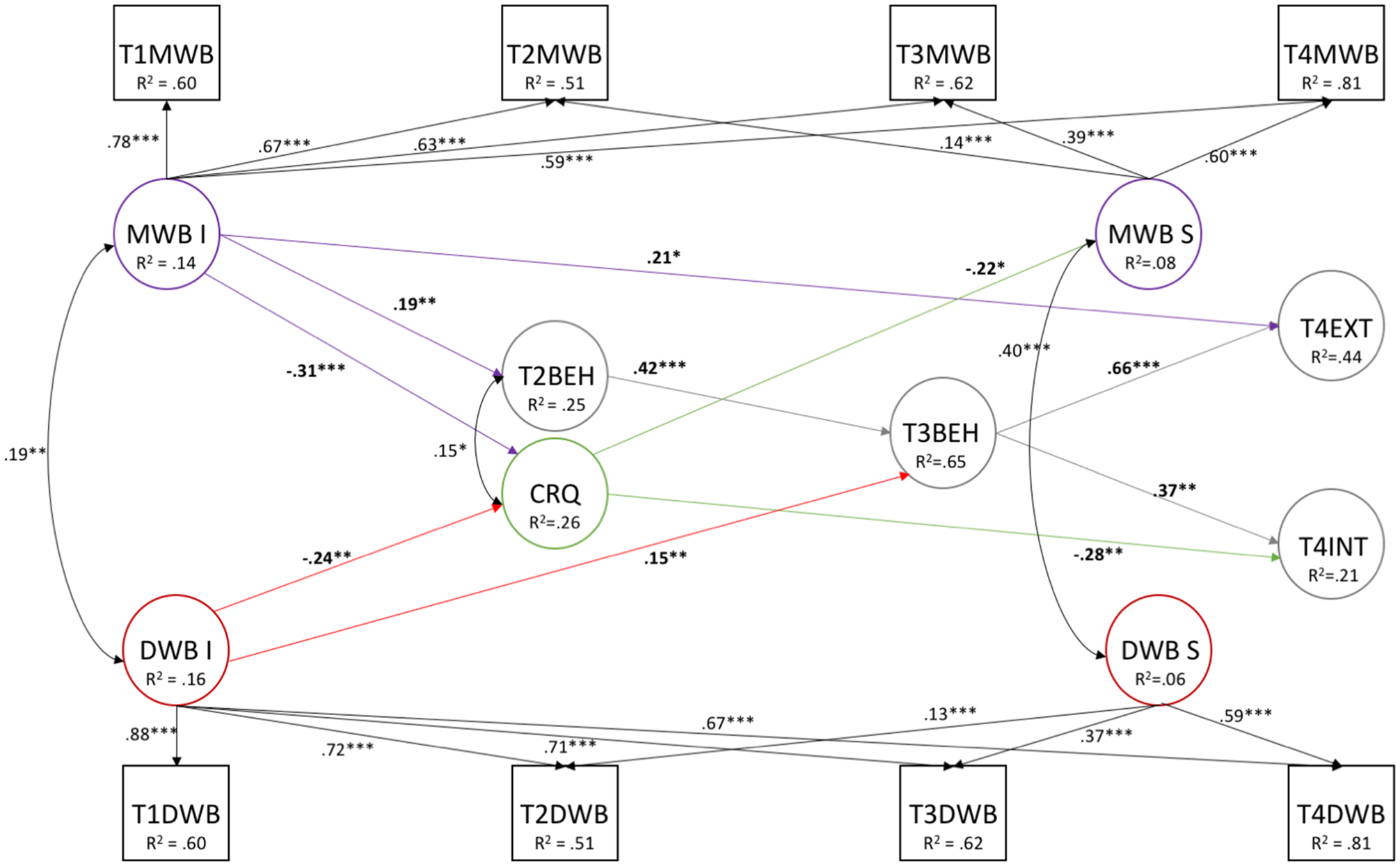

The model provided an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (215) = 386.980, CFI = .944, TLI = .917, RMSEA = .043, 90% CI [0.036, 0.050]. Figure 1 shows a simplified path diagram depicting the results in (a) mothers and (b) fathers. The full model output is in online-only Supplemental Table S.4. There was a significant indirect effect of maternal well-being intercepts on 24-month internalizing via couple relationship quality at 4 months, β = 0.085, SE = 0.035, Z = 2.424, p = .015, 95% CI [0.016, 0.154], and a significant indirect effect of paternal well-being intercepts on 24-month internalizing via couple relationship quality at 4 months, β = 0.067, SE = 0.033, Z = 2.069, p = .039, 95% CI [0.004, 0.131]. There was a significant indirect effect of paternal well-being intercepts on 24-month externalizing via 14-month behavior problems, β = 0.100, SE = 0.036, Z = 2.747, p = .006, 95% CI [0.029, 0.171]. Both maternal and paternal prenatal well-being contribute to children's externalizing problems.

Figure 1. Simplified path diagram depicting standardized estimates for predictors of child behavior problems at 4, 14, and 24 months. Only statistically significant paths are shown. MWB, mums’ well-being. DWB, dads’ well-being. I, intercept. S, slope. T1, prenatal visit. T2, 4-month visit. T3, 14-month visit. T4, 24-month visit. BEH, behavior problems. EXT, externalizing. INT, internalizing. CRQ, couple relationship quality at T2. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

We tested two follow-up models to examine the interactions between the effects of maternal and paternal prenatal and postnatal well-being on children's adjustment. To this end, we extended the final model by regressing child internalizing and externalizing onto a multiplicative interaction between (a) the maternal and paternal latent intercepts in one model and (b) the maternal and latent paternal slopes in a separate model. The latent intercept interaction term did not uniquely predict internalizing, Std. Est. = 0.03, SE = 0.03, Z = 1.06, p = .29, 95% CI [–0.03, 0.10], or externalizing, Std. Est. = –0.07, SE = 0.06, Z = –1.09, p = .27, 95% CI [–0.18, 0.05]. The latent slope interaction term did not uniquely predict internalizing, Std. Est. = –0.01, SE = 0.06, Z = –0.24, p = .81, 95% CI [–0.12, 0.10], or externalizing, Std. Est. = 0.07, SE = 0.05, Z = 1.49, p = .14, 95% CI [–0.02, 0.17]. In two further models we investigated the effect on child adjustment of the interactions between (a) maternal intercepts and paternal slopes and (b) between paternal intercepts and maternal slopes. The first interaction did not predict internalizing, Std. Est. = 0.03, SE = 0.04, Z = 0.67, p = .50, 95% CI [–0.10, 0.20], or externalizing, Std. Est. = 0.04, SE = 0.04, Z = 0.96, p = .34, 95% CI [–0.05, 0.16]. Likewise, the second interaction did not predict internalizing, Std. Est. = 0.05, SE = 0.08, Z = 0.54, p = .59, 95% CI [–0.12, 0.21], or externalizing, Std. Est. = 0.03, SE = 0.10, Z = 0.30, p = .76, 95% CI [–0.17, 0.23]. These results suggest that the effects of paternal and maternal well-being on child adjustment are distinct.

Discussion

The objectives of this longitudinal study of 438 mothers and fathers and their first-born children were to identify whether prenatal and postnatal measures of parental well-being made unique contributions to variation in children's early adjustment (adopting a dual focus on behavioral and emotional problems) and to examine potential mediating effects of couple relationship quality. Beyond stability in both parental and child measures, our analyses showed direct effects of prenatal well-being in mothers on externalizing problems at 24 months, even when prior history of depression and anxiety and postnatal exposure to poor maternal well-being were controlled. Likewise, variation in fathers’ prenatal well-being was directly related to socioemotional problems at 14 months, which in turn mediated the association between fathers’ prenatal well-being and externalizing problems at 24 months. In contrast, variation in couple relationship quality fully mediated effects of parental well-being on internalizing symptoms at 24 months.

Findings from our latent growth models of both maternal and paternal well-being support the view that symptom severity is stable across the transition to parenthood (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014). Given this stability, it is striking that both mothers’ and fathers’ prenatal well-being showed unique predictive associations with children's behavioral problems at 24 months. This complements existing evidence for a link between paternal prenatal mental health and children's adjustment at 36 months (Kvalevaag et al., Reference Kvalevaag, Ramchandani, Hove, Assmus, Eberhard-Gran and Biringer2013), and extends this work by including postnatal symptoms. In contrast with the findings from prior studies, both maternal and paternal prenatal well-being in the current study showed unique associations with child adjustment. This may be because our analyses focused on the first 2 years of life when infants have particularly extended periods of contact with their parents. In contrast, previous investigations have examined how exposure to poor parental well-being affects child adjustment using age groups that are often exposed to nonfamilial environments, such as the preschool years (e.g., Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion, & Wilson, Reference Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion and Wilson2008), early school age (e.g., Van Baternburg et al., Reference Van Batenburg-Eddes, Brion, Henrichs, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2013), or adolescence (e.g., Shelton et al., Reference Shelton, Harold, Fowler, Rice, Neale, Thapar and Van Den Bree2008). Our focus on the first 2 years of life was motivated by meta-analytic evidence (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011) that early exposure amplifies the impact of maternal depression on child adjustment. Factors that may contribute to this effect include heightened vulnerability in young children (i.e., infancy as a “sensitive period”); buffering effects of early healthy development on the impact of later exposure (e.g., the acquisition of sociocognitive and emotion regulation skills enables children to make adaptive responses); and age-related increases in the salience of children's relationships with nonparental caregivers and peers.

At first glance, unique associations between fathers’ prenatal well-being and child externalizing problems suggest genetic effects, because socially mediated effects of postnatal exposure have been controlled. Our results are consistent with genetically sensitive adoption studies, which show that fetal exposure to maternal depression is associated with later externalizing problems in adopted children (Pemberton et al., Reference Pemberton, Neiderhiser, Leve, Natsuaki, Shaw, Reiss and Ge2010). However, it is worth noting that prenatal well-being showed unique effects on children's externalizing over and above effects of either paternal or maternal prepregnancy history of depression/anxiety, a possible marker of genetic predisposition (Davey Smith, Reference Davey Smith2008; Van Battenburg et al., Reference Van Batenburg-Eddes, Brion, Henrichs, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2013). Given the concordance in levels of well-being in expectant mothers and fathers, an alternative explanation is that mothers’ exposure to partners’ difficulties mediated the association between fathers’ prenatal well-being and children's externalizing problems.

In contrast with the findings for children's externalizing problems, prenatal parental well-being showed no direct association with child internalizing problems at 24 months. Instead, our model showed that postnatal couple relationship quality mediated the association between prenatal well-being and internalizing problems at 24 months, even when effects of postnatal exposure to poor parental well-being were considered. Our results extend existing meta-analytic evidence (based largely on older children), which shows consistent associations between interparental conflict and child maladjustment, by providing evidence that parental relationship quality in the first months of life may have adverse consequences on children as early as the second year of life (Buehler et al., Reference Buehler, Anthony, Krishnakumar, Stone, Gerard and Pemberton1997; Rhoades, Reference Rhoades2008). In addition, our results support evidence that marital conflict plays a mediating role in the associations between maternal and paternal perinatal well-being and behavior problems at age 42 months (Hannington et al., Reference Hanington, Heron, Stein and Ramchandani2012). While our models elucidate one mechanism by which parental well-being impacts on child internalizing, understanding the cognitive and physiological processes by which exposure to interparental conflict gives rise to internalizing problems requires further research (Cummings & Davies, Reference Cummings and Davies2002; Rhoades, Reference Rhoades2008).

Our results contribute to the field by demonstrating that couple relationship difficulties play a mediating role in the intergenerational transmission of internalizing problems from as early as 24 months of age. In addition, our results indicated domain-specific pathways. That is, interparental conflict played a mediating role in relation to children's internalizing problems but no parallel mediating effect was found in relation to children's externalizing problems. Note that this second point contrasts with South, Krueger, and Iaconos (Reference South, Krueger and Iacono2011) conclusion that interparental distress had a broad, nonspecific, impact upon child psychopathology. Arguably, this contrast hinges on our focus on the first years of life, in which externalizing problems are so common as to be developmentally normative. Further replication work involving older children is needed.

Caveats and conclusions

Two sets of limitations deserve note. First, despite the three-site international design of our study, the relatively small Dutch and American subsamples precluded analysis of the cross-country consistency of study findings. There are clear contrasts in health and social care systems in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands (e.g., statutory paid maternity leave entitlement is 0 weeks in the US, 16 weeks in the Netherlands, and 39 weeks in the UK; OECD, 2019). In view of these contrasts, it would be interesting to explore differences between sites in future work using larger samples. While the demographically and medically low-risk nature of the sample ensured a clean test of how parental well-being influences child adjustment (by limiting potential socioeconomic confounds), the relatively homogeneous sample limits the generalizability of our results. For instance, meta-analytic data indicate that socioeconomic status is a modest but significant predictor of divorce (Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, Reference Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi and Goldberg2007). Inclusion of a more diverse sample would provide an opportunity to examine whether heightened interparental conflict mediates the association between parental well-being and child outcomes. In addition, meta-analytic evidence (Grigoriadis, VonderPorten, & Mamisashvili, Reference Grigoriadis, VonderPorten and Mamisashvili2013) indicates that prenatal depression is associated with premature birth and, in low-/middle-income countries at least, with low birthweight. Thus, several different pathways are likely to underpin the relation between prenatal exposure to poor parental well-being and child outcomes.

Second, our analyses drew exclusively on parent questionnaire data, such that further work including an independent measure of children's behavior problems is needed (e.g., Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Keller and Davies2005). Just 1 of the 21 studies reviewed by Sweeney and MacBeth (Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016) included nonparental ratings of children's adjustment, suggesting that a key methodological challenge for future studies in this field is to assess the importance of informant effects. Further work involving directly observed parent–child interactions and physiological measures of parent and child stress will help to identify the processes that underpin associations between parental well-being and child adjustment.

The current study stands apart from the field in its use of latent growth models to examine the unique contribution of prenatal and postnatal well-being in both mothers and fathers as predictors of child adjustment in the first 2 years of life. Our results demonstrate that both maternal and paternal perinatal well-being have a unique impact on child adjustment in the first 2 years of life. Our results also suggest that parental well-being is linked to child externalizing and internalizing problems via distinct mechanisms. Specifically, interparental relationship quality appears to mediate associations between parental well-being and child internalizing (Hanington et al., Reference Hanington, Heron, Stein and Ramchandani2012), but not child externalizing. In addition, by statistically controlling for postnatal well-being trajectories (i.e., postnatal environmental influence) and parents’ prior history of depression and anxiety (i.e., a proxy indicator for genetic predisposition), our results provide strong evidence for unique prenatal effects on later child externalizing (Davey-Smith, Reference Davey Smith2008; Van Battenburg-Eddes et al., Reference Van Batenburg-Eddes, Brion, Henrichs, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2013). Together these results highlight the prenatal period as a salient window for research on clinical interventions to improve couple relationship quality and well-being in both expectant mothers and expectant fathers, with potential downstream benefits for child outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000804.

Author Contributions

The NewFAMS Team (in alphabetical order): Lenneke Alink, Marjolein Branger, Wendy Browne, Rosanneke Emmen, Sarah Foley, Lara Kyriakou, Anja Lindberg, Gabrielle McHarg, Andrew Ribner, Mi-Lan Woudstra.

Financial Support

This work was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, UK (Grant Number: ES/LO16648/1); Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research; and the National Science Foundation, USA. The NewFAMS Team (in alphabetical order): Lenneke Alink, Marjolein Branger, Wendy Browne, Rosanneke Emmen, Sarah Foley, Lara Kyriakou, Anja Lindberg, Gabrielle McHarg, Andrew Ribner, Mi-Lan Woudstra.