In recent decades, evidence of the harmful effects of early adversity on a range of crucial relational, social, cognitive, genetic, and neurological developments has grown exponentially (Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998; Fox, Levitt, & Nelson, Reference Fox, Levitt and Nelson2010; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017; Shonkoff, Reference Shonkoff2012); put simply, chronic stress is not good for children. Evidence has also proliferated that the quality of caregiving is central to the child's developing resilience in the face of adversity (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Guthrie, Smyke, Koga, Fox, Zeanah and Nelson2010; Julian, Lawler, & Rosenblum, Reference Julian, Lawler and Rosenblum2017), and that secure attachment is linked to a range of short- and long-term positive social, emotional, and cognitive developmental outcomes across a wide range of populations (Cassidy & Shaver, Reference Cassidy and Shaver2016; Slade & Holmes, Reference Slade and Holmes2013; Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, Reference Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson and Collins2005). Likewise, disorganized attachment, a pernicious outcome of disrupted relationships (Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, & Parsons, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999) as well as socioeconomic risk (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, Reference Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2010), has been linked to a range of long-term negative outcomes (Carlson, Reference Carlson1998; Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Jacobvitz, Cassidy and Shaver2016). Given the emerging evidence that disorganized attachment can be prevented with intervention (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012; Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2006; Grandqvist et al., Reference Grandqvist, Sroufe, Dozier, Hesse, Steele, van IJzendoorn and Duschinsky2018; Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Slade, Close, Webb, Simpson, Fennie and Mayes2013), there is a pressing need to intervene early and effectively in the lives of vulnerable infants, toddlers, and their families, and in particular to promote secure attachment relationships (see Steele & Steele, Reference Steele and Steele2017; Zeanah, Reference Zeanah2018, for reviews).

While there are many approaches to early intervention, home visiting remains one of the most effective ways to reach disenfranchised and traumatized families, and combat the intergenerational effects of severe poverty, disadvantage, and attachment disruption on a range of health and socioemotional outcomes (Garner, Reference Garner2013; Olds, Sadler, & Kitzman, Reference Olds, Sadler and Kitzman2007). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists home visiting as the primary way to prevent adverse childhood experiences in the next generation (https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/about_ace.html).

Minding the Baby® (MTB) is an attachment-based, interdisciplinary home visiting intervention aimed at improving developmental, health, and relationship outcomes in vulnerable young families having their first child. In 2014 it was designated by the Health and Human Services Administration as one of 18 evidence-based home visiting programs in the United States. In this report, we describe the impact of MTB on relationship and mental health outcomes in Phase 2 of a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Specifically, we compare intervention and control groups on the following outcomes: (a) the level of parental reflective functioning (RF), (b) the quality of dyadic affective communication, (c) the quality of infant attachment, and (d) maternal depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We begin with a brief description of the MTB model and its key elements; then, after a brief review of the results of Phase 1 of our RCT, we turn to the methods and results of the Phase 2 RCT.

Minding the Baby®

The MTB model

MTB provides intensive home visiting services to first-time mothers, babies, and their families beginning in the second trimester of pregnancy. Families are visited weekly through pregnancy, labor and delivery, and the child's first year, and then biweekly until the child turns 2. MTB is delivered by an interdisciplinary team made up of a master's prepared nurse and a clinical social worker.Footnote 1 The nurse and social worker alternate visits throughout the program, with occasional joint visits as indicated. The frequency of visits is adjusted according to each family's need, with more frequent visits offered at times of crisis. While the mother and her baby are the primary focus of the intervention, fathers are encouraged to participate, as are other key people in the mother's life, such as her own mother, a sibling, and so on. MTB practitioners are guided by a comprehensive treatment manual (Slade, Sadler, Webb, Simpson, & Close, Reference Slade, Simpson, Webb, Albertson, Close, Sadler, Steele and Steele2018) that provides the tools necessary to offer responsive, informed, and appropriate care across the periods of pregnancy, infancy, and toddlerhood (see Sadler Slade, Close, Webb, Simpson, Fennie, & Mayes, Reference Sadler, Slade, Close, Webb, Simpson, Fennie and Mayes2013, for more details on the intervention model).

MTB is a relationship-based program, meaning that the delivery of the intervention depends upon the quality of the relationship home visitors establish with mothers and their families. Thus, we endeavor from the very beginning to emotionally engage mothers, even when, as is often the case, they find it difficult to trust and open up to clinicians. Both the nurse and the social worker provide developmental guidance, scaffold parenting, and support the developing mother–infant attachment relationship. They also attend to families’ physical safety and basic necessities, supplying diapers, emergency food assistance, and the like. Each home visitor also has roles specific to her discipline. The nurse focuses on health promotion (including reproductive care, nutritional guidance, foreshadowing, links to the medical home, etc.), and may screen for depression (typically postpartum depression) and suggest nonpharmacological interventions such as exercise and rest. The social worker uses a variety of approaches to address what are typically a significant array of mental health difficulties, many of which are the sequelae of complex trauma (Courtois, Reference Courtois2004), including trauma symptoms, depression, and anxiety. Approaches include infant–parent psychotherapy, adult psychotherapy, family/couple counseling, and support for the mother to experience, explore, and move toward resolving the impact of trauma. The social worker also provides a wide range of concrete supports, including help with housing, food, schooling, and navigating a wide range of often overwhelming and challenging social systems. Crucially, MTB begins this work before the baby is born, when the caregiving system (Solomon & George, Reference Solomon and George1996) is just beginning to develop.

The key elements of MTB

In developing our intervention, we focused on potentiating two elements of the mother–child relationship that have been positively associated with secure attachment in infancy, and negatively associated with insecure, and particularly disorganized, attachment: maternal RF and affective communication between mother and child.

Parental RF refers to the ability to imagine or envision the baby's thoughts and feelings, as well as to understand the child's behavior as a function of underlying subjective experience (Slade, Reference Slade2002, Reference Slade2005). An individual's mentalizing capacityFootnote 2 can be assessed within the framework of a number of relationships (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Leigh, Kennedy, Mattoon, Target, Goldberg, Muir and Kerr1995; Slade, Reference Slade2005); parental RF refers specifically to the parent's capacity to make meaning of her child's thoughts, feelings, and behavior, as well as her own experience as a parent. Mentalizing about the child and about oneself as a parent begins to emerge in pregnancy (Pajulo et al., Reference Pajulo, Pyykkonen, Kalland, Sinkkonen, Helenius, Punamaki and Suchman2012; Sadler, Novick, & Meadows-Oliver, Reference Sadler, Novick and Meadows-Oliver2016; Slade & Sadler, Reference Slade, Sadler and Zeanah2018; Smaling et al., Reference Smaling, Huijbregts, Suurland, van der Heijden, van Goozen and Swaab2015, Reference Smaling, Huijbregts, Suurland, van der Heijden, Mesman, van Goozen and Swaab2016), and evolves as the child develops (Slade, Reference Slade2005; Sleed, Slade, & Fonagy, Reference Sleed, Slade and Fonagy2018).

Studies of high-risk samples consistently report lower baseline levels of parental RF (Muzik et al., Reference Muzik, Rosenblum, Alfafara, Schuster, Miller, Waddell and Kohler2015; Smaling et al., Reference Smaling, Huijbregts, Suurland, van der Heijden, van Goozen and Swaab2015; Stacks et al., Reference Stacks, Muzik, Wong, Beeghly, Huth-Bocks, Irwin and Rosenblum2014; Suchman, DeCoste, Leigh, & Borelli, Reference Suchman, DeCoste, Leigh and Borelli2010) than those found in low-risk populations (Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, Reference Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy and Locker2005). While the term “high risk” refers to a range of factors, chief among them are significant histories of early adversity or trauma, including abuse and neglect, substance use, family dysfunction, and parental psychopathology. Also common to many high-risk populations are the “socioeconomic risks” associated with poverty, namely, low maternal education, young maternal age at childbirth, single parenthood, minority group status, and substance use (Cyr et al., Reference Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2010).

A number of studies have linked moderate or high levels of maternal RF to secure infant attachment, in both low-risk (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Leigh, Kennedy, Mattoon, Target, Goldberg, Muir and Kerr1995; Meins, Fernyhough, Fradley, & Tuckey, Reference Meins, Fernyhough, Fradley and Tuckey2001; Slade, Grienenberger, et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005) and high-risk (Stacks et al., Reference Stacks, Muzik, Wong, Beeghly, Huth-Bocks, Irwin and Rosenblum2014) samples (see Katznelson, Reference Katznelson2014, for a review). Likewise, low maternal RF has been linked with disorganized attachment (Grienenberger, Kelly, & Slade, Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005). Maternal RF is also associated with an adult's security on the Adult Attachment Interview (Slade, Grienenberger, et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005), and is thought to arise within the framework of secure and safe early relationships (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Leigh, Kennedy, Mattoon, Target, Goldberg, Muir and Kerr1995).

Particularly in the earliest months and years of life, a parent's capacity to envision her child's internal experience is expressed through her behavior (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Leigh, Kennedy, Mattoon, Target, Goldberg, Muir and Kerr1995; Grienenberger et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999; Shai & Belsky, Reference Shai and Belsky2017; Slade, Grienenberger, et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005). Higher levels of maternal RF have been linked to sensitive maternal behavior when RF is measured both prenatally (Smaling et al., Reference Smaling, Huijbregts, Suurland, van der Heijden, Mesman, van Goozen and Swaab2016) and postnatally (Stacks et al., Reference Stacks, Muzik, Wong, Beeghly, Huth-Bocks, Irwin and Rosenblum2014). Maternal RF has also been inversely correlated with disrupted affective communication between mother and child (Grienenberger et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005), which is known to predict to disorganized attachment (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999). Mediational analyses suggest that both maternal RF and dyadic affective communication serve as mechanisms for the intergenerational transmission of attachment (Grienenberger et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005), with both impacting attachment outcomes. Moreover, the work of Smaling et al. (Reference Smaling, Huijbregts, Suurland, van der Heijden, Mesman, van Goozen and Swaab2016) suggests that prenatal maternal RF has a powerful impact on sensitive maternal behavior in the early months of life. Thus, the promotion of RF from pregnancy onward may be key to the development of regulated, positive interactions, and ultimately the development of secure attachment.

Phase 1 of the RCT

In Phase 1 of our RCT, (Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Slade, Close, Webb, Simpson, Fennie and Mayes2013), we demonstrated a range of beneficial health and attachment outcomes arising as a result of participation in MTB. In a sample of 60 MTB and 45 control families (who, as we will describe below, received treatment as usual at their Community Health Center [CHC]), MTB infants, mothers, and dyads compared favorably to controls in a number of areas. MTB infants were significantly more likely to be up-to-date with their pediatric immunizations at 1 year, and less likely to be referred to Child Protective Services. MTB mothers had significantly lower rates of rapid subsequent childbearing. Mother–infant affective communication in MTB dyads where the mother was less than 20 years of age was less likely to be disrupted at 4 months, and all intervention infants were more likely to be securely attached and less likely to be disorganized at 12–14 months of age. Finally, MTB mothers’ capacity to reflect on their own and their child's experience improved significantly over the course of the intervention in the most high-risk mothers, as compared with high-risk control mothers. A follow-up study of the Phase 1 cohort revealed that mothers in the MTB group reported significantly fewer externalizing behavior problems than did control mothers when their children were between 3 and 5 (Ordway, Sadler, Slade, Close, Dixon, & Mayes, Reference Ordway, Sadler, Slade, Close, Dixon and Mayes2014). In addition, we found significantly lower levels of obesity, and a significantly higher likelihood of being in the normal weight range in MTB Hispanic toddlers across the combined sample from Phases 1 and 2 (Ordway et al., Reference Ordway, Sadler, Holland, Slade, Close and Mayes2018).

Research Aims of Current Study

The current study, Phase 2 of our RCT, included a larger sample than Phase 1, drawn from two urban CHCs. We tested four main hypotheses, predicting that as compared to dyads in the control condition, (a) MTB mothers would have higher RF; (b) dyads participating in MTB would be less likely to have disrupted affective communication; (c) MTB infants would be more likely to be securely attached, and less likely to be disorganized; and (d) the MTB intervention would have a positive impact on maternal depression and PTSD.

Method

Design

We utilized a cluster two-group experimental design (Hauck, Gilliss, Donner, & Gortner, Reference Hauck, Gilliss, Donner and Gortner1991) to test the effects of the MTB program with young families attending two CHCs. In the first CHC site, most prenatal care was delivered in groups by nurse midwives, although some women chose to have individual prenatal care appointments. Cluster randomization was accomplished by randomizing prenatal groups (sealed envelope method) to minimize the chance of contamination among group members. Six groups were held throughout each year and were defined by the pregnant women's similar due dates. At the second site, all prenatal care was delivered in individual appointments by nurse midwives. Here we clustered pregnant women by their due dates to facilitate an equivalent randomization scheme. Thus, group status was randomly assigned (based on due dates and prenatal group membership) prior to participants being consented and enrolled into the study, and participants were informed of their intervention group assignment before consenting.

Setting

The CHCs from which participants were recruited deliver care to a medically underserved population of families, most of whom live at or below the poverty line and have diverse cultural and ethnic heritages, including African, Caribbean, Puerto Rican, Mexican, and South and Central American. Most home visits took place in participants’ homes unless the mother requested the visit occur elsewhere (such as a coffee shop, library, at the CHC, etc.). Research instruments were administered to both control and intervention mothers at home by a research assistant. For both intervention and control group mothers, the mother–child assessments took place in a laboratory space at a location convenient to families’ homes.

Recruitment

Primiparous women attending prenatal care sessions at the CHCs were approached to assess their interest in participating in the study. All participants who met inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria for mothers included the following: (a) able to speak and understand English; (b) between 14 and 25 years of age; (c) having a first child; (d) no active heroin or cocaine use (prescreened by the CHC as criteria for entry into prenatal care); (e) no DSM-IV psychotic disorder; and (f) no major or terminal chronic condition in the mother (AIDS, cancer, etc. [prescreened by the CHCs]).

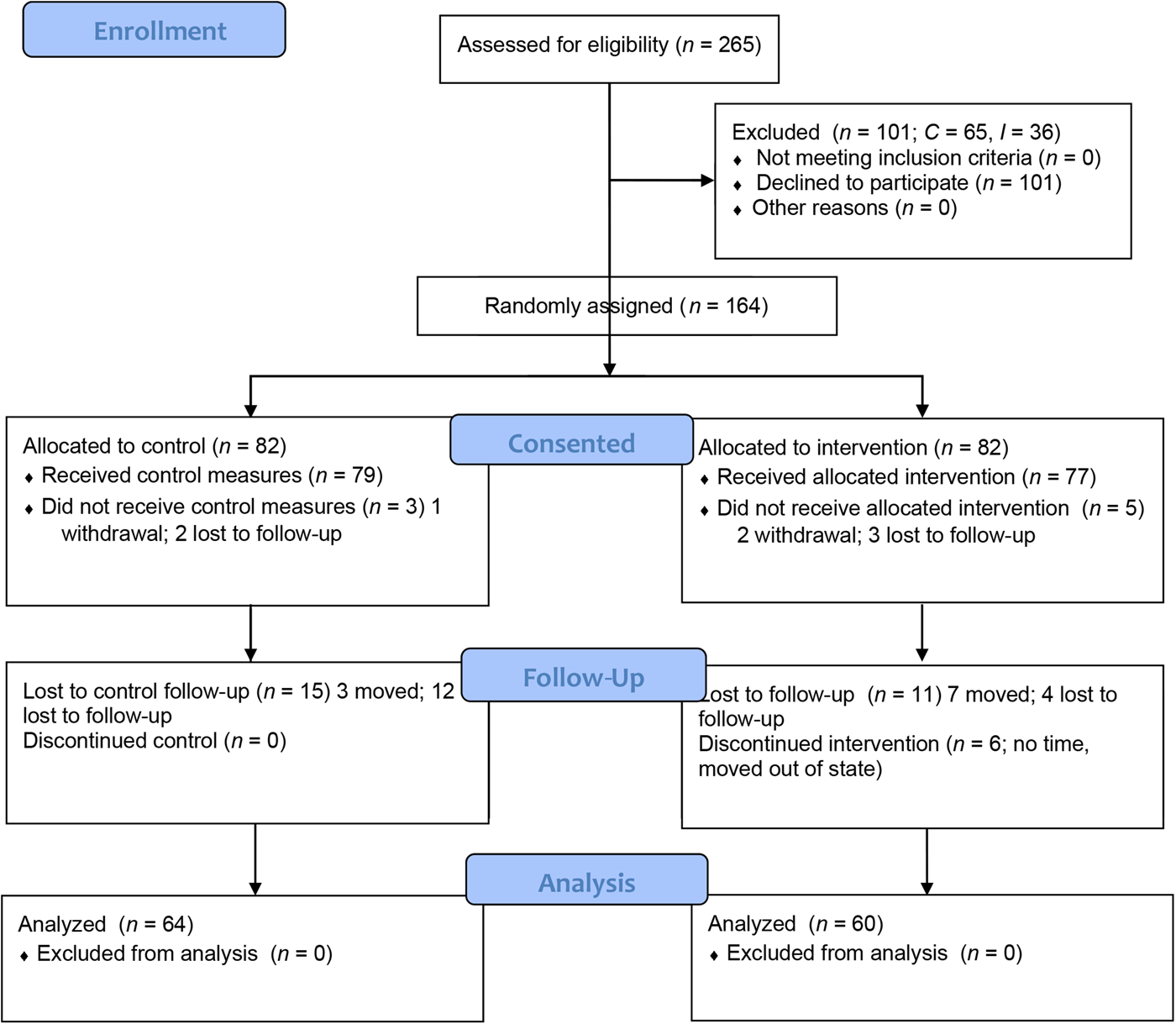

Two hundred and sixty-five families met criteria for the study; based on their due dates (see above), women were invited into the intervention or control group. Of this group, 164 agreed to participate (65 declined to participate in the control group, 36 declined the intervention). Eighty-two consented to be in each group; of these, 3 in the control group did not receive control group measures, and 5 in the intervention group did not receive the intervention. Thus, there were 156 mothers who participated in the study; of these, 79 were in the control group and 77 were in the intervention group (see Figure 1 for details of enrollment and retention).

Figure 1. MTB CONSORT flow diagram

In order to ensure continued enrollment and retention of intervention participants, home visits were set up at the mother's convenience around school and work schedules, and phone or text contacts were made to reschedule missed or cancelled visits. This process applied to research visits as well.

The study was approved by the university and CHC research review committees. Recruitment began in midpregnancy, and participation was voluntary. The CHC nurse midwives initially contacted potential research participants; those expressing interest to CHC staff were then approached by MTB staff, who explained the project. Women who volunteered, met inclusion criteria, and gave informed consent (or if younger than age 18, a parent provided written permission and the participant provided assent) were enrolled in the study. Both groups were followed for 27 months.

Treatment conditions

Minding the Baby® intervention group

As previously described, the team of home visitors began weekly home visits in the late second or early third trimester of pregnancy. These continued until the child's first birthday, when there was a celebratory “transition” visit acknowledging the growth and progress of the first year and setting goals for visits in the second year. After this point, the home visits occurred every other week until the child was 24 months old. During the intervention, all families continued to receive their routine prenatal, primary care, and pediatric care from the CHC clinicians. At graduation, there was a joint visit by both home visitors to celebrate the family's completion of the program.

Fidelity to the model was maintained through ongoing training and supervision. MTB practitioners first completed an introductory 3-day training, and became familiar with MTB's comprehensive treatment manual (Slade, Sadler, et al., Reference Slade, Sadler, Webb, Simpson and Close2018). Once they began seeing families (a full-time caseload was 20–25 families), they met weekly for an hour of discipline-specific supervision (i.e., the nurse met with a nurse supervisor, the social worker with a social work supervisor), an hour of interdisciplinary supervision, with supervisors from both disciplines in attendance, and a 90-min team meeting. All supervision (typically provided by program directors) incorporated case review, and clinical as well as reflective supervision (Weatherston & Barron, Reference Weatherston, Barron, Heller and Gilkerson2009). Clinicians also took part in quarterly professional training sessions led by program directors.

Control group treatment

Control group participants received routine prenatal and postnatal well-woman health visits, and well-baby health care visits as dictated by clinical guidelines and infant/child immunization schedules in place at the CHCs. Control group families were sent quarterly information from Healthy Steps (Kaplan-Sarnoff & Zuckerman, Reference Kaplan-Sarnoff and Zuckerman2007) materials about child development and health and were sent birthday and holiday cards. We maintained phone contact with control group families to schedule research sessions at baseline, 4, 12–14, and 20–24 months.

Data collection

Baseline data collection (at 20–24 weeks of pregnancy) included a demographic interview, baseline psychiatric instruments, and the Pregnancy Interview (Slade, Reference Slade2003), a clinical interview regarding the young women's experience of pregnancy and expectations about the baby. When the baby was 4 months old, mothers and infants were invited to a conveniently located developmental laboratory, and videotaped and observed in face-to-face interaction. At 12–14 months, the Strange Situation procedure (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) was administered in the same setting. At 24 months, a research assistant visited mothers in the home, preferably when they could be alone and undisturbed, and administered written surveys and the Parent Development Interview (Slade, Aber, Berger, Bresgi, & Kaplan, Reference Slade, Aber, Berger, Bresgi and Kaplan2004). Participants were paid $50.00 for their time for each of the research data collection visits. When travel to the lab was required, they were paid an additional $15.00 for transportation costs. Experienced female research assistants familiar with community families collected the data.

Measures

Mothers’ demographic and health information

Information regarding age, family background, educational background, and medical history was collected at baseline by interview and health record reviews (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics for intervention and control groups at baseline

Note: p values were obtained from two-sided t test for age and chi-square test for other categorical variables. ap value was obtained from two-side Cochran–Armitage Trend Test. bp values were obtained from two-side Fisher's exact test due to small cell sizes. cp values were obtained from ordered logistic regression. dp values were obtained from Wilcoxon rank-sum test due to a nonnormal distribution. RF, reflective functioning. PI, Pregnancy Interview. CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Maternal RF

Pregnancy Interview (PI; Slade, Reference Slade2003)

The PI is a 22-item clinical interview designed to assess a woman's emotional experience of pregnancy and the nature of her developing relationship with her baby. This interview has been used in a range of samples (Pajulo et al., Reference Pajulo, Pyykkonen, Kalland, Sinkkonen, Helenius, Punamaki and Suchman2012; Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Novick and Meadows-Oliver2016; Smaling et al., Reference Smaling, Huijbregts, Suurland, van der Heijden, van Goozen and Swaab2015, Reference Smaling, Huijbregts, Suurland, van der Heijden, Mesman, van Goozen and Swaab2016). Audio-taped responses were transcribed verbatim, and the transcript was scored by coders blind to group status, using the RF scoring system described below, adapted for use with the PI (Slade, Patterson, & Miller, Reference Slade, Patterson and Miller2005). For moderation analysis, we dichotomized PI at >2 versus ≤2, to distinguish prementalizing from emerging RF (Fonagy, Target, Steele, & Steele, Reference Fonagy, Target, Steele and Steele1998). The coders of the PI (senior RF/PI trainers) were naive to the group status of all interview transcripts. Already reliable on the PI/RF system, their reliability was assessed on an additional 13% of sample transcripts; the criterion for reliability was 80% agreement on individual variable and overall scores.

Parent Development Interview—Revised (PDI; Slade et al., Reference Slade, Aber, Berger, Bresgi and Kaplan2004)

The PDI is a 20-question interview that assesses the parent's representations of their relationship with their child. The interview takes approximately 45 min to administer; the parent is asked to describe their experience of the child, their relationship with the child, their own internal experience of parenting, and the child's reactions to normal separations, routine upsets, and parental unavailability. Transcribed interviews were scored for RF. RF is scored on a scale of –1 to 9 with lower scores (–1 to 2) indicating prementalizing processes, or the inability to consider one's own or another's thoughts and feelings, and higher scores reflecting increasing abilities to understand the nature of mental states and the relationship between internal experience and behavior (Slade, Bernbach, Grienenberger, Levy, & Locker, Reference Slade, Bernbach, Grienenberger, Levy and Locker2005).

Studies testing the validity of this measure have linked it to adult attachment, child attachment, and parental behavior both in normal and drug-using samples (Borelli, St. John, Cho, & Suchman, Reference Borelli, St. John, Cho and Suchman2016; Slade, Belsky, Aber, & Phelps, Reference Slade, Belsky, Aber and Phelps1999; Slade, Grienenberger, et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005; Stacks et al., Reference Stacks, Muzik, Wong, Beeghly, Huth-Bocks, Irwin and Rosenblum2014; Suchman, DeCoste, Leigh, et al., Reference Suchman, DeCoste, Leigh and Borelli2010). In a validation study of the PDI, Sleed, Slade, and Fonagy (Reference Sleed, Slade and Fonagy2018) reported high interrater reliability, internal consistency, and criterion validity. There were significant differences between clinical, normative, and prison populations on maternal RF scores; mothers in the prison sample had the lowest scores, the clinical sample fell in the middle, and the community sample had the highest scores. This same study found high levels of internal consistency for item and overall scores on the PDI. In the present study, coders (senior RF/PDI trainers) naive to the group status of all interview transcripts were trained to reliability on set of 25 PDI training transcripts, 16% of which were sample transcripts; the criterion for reliability was 80% agreement on individual variable and overall scores.

PDI/RF scores did not meet assumptions for normality, as the preponderance of scores fell between 1 and 5. We therefore collapsed the PDI/RF scores into 4 groups: prementalizing (scale scores of 1–2.5), low RF (3–3.5), moderate RF (4–4.5), and high (5+; see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Reflective functioning group by treatment group. Group difference by category: p = .04; p value and predicted distribution from ordered logistic regression controlling for baseline Pregnancy Interview/Reflective Functioning

Mother–infant interaction

Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification (AMBIANCE) Scale (Bronfman, Parsons, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Bronfman, Parsons and Lyons-Ruth1999)

The AMBIANCE scale is used to assess the quality of affective communication between mother and infant. Videotaped face-to-face interactions at 4 months, in which infants were placed in an infant seat and mothers were instructed to play with them as they normally would for 15 min, were coded on a 7-point scale, with a higher score denoting more disrupted communication. Scores of 5 or above indicate disrupted affective communication in the dyad, whereas scores below 5 indicate nondisrupted affective communication. This measure has been validated against the Strange Situation, and with maternal and infant behavior observed in the home (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999). We used a version of the AMBIANCE scale developed for 4-month-old infants and their mothers (Kelly, Slade, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Kelly, Slade and Lyons-Ruth2003). To establish interrater reliability, the developer of the 4-month code scored a subset (20/124) of the data set along with the primary coder. The intraclass correlation coefficient was .88. Both were naive to the group status of infant–mother dyads. For moderation analyses, we dichotomized AMBIANCE at ≥5 versus <5 (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999).

Infant attachment

The Strange Situation procedure (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978)

This is a 30-min laboratory separation procedure aimed at assessing the quality of the child's attachment to his caregiver. The procedure yields one of four primary attachment classifications: secure (B), avoidant (A), resistant (C), and disorganized (D). This well-validated and reliable procedure has been used in studies of attachment for 30 years. It has also has been used successfully with low-income mothers and mothers from various cultural backgrounds (see Cassidy & Shaver, Reference Cassidy and Shaver2016). This procedure was conducted and videotaped by a trained team at the Yale Child Study Center when the child was 12–14 months old. Coding was performed by an expert coder blind to the group status of the participants. Reliability was assessed on 15% of the sample with a reliability criterion of 80%. Due to small numbers in avoidant and resistant categories, we examined this measure as three categories: secure, insecure (avoidant/resistant), and disorganized.

Maternal mental health measures

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977)

The CES-D consists of 20 items selected from other depression scales; the six major symptom areas assessed include depressed mood, guilt/worthlessness, helplessness/hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbance. The reliability of the CES-D has been documented with high internal consistency, acceptable test–retest stability, and construct validity in both clinical and community samples and has been used successfully with urban adolescents and adolescent mothers. In this sample the Cronbach's α coefficients were 0.83 and 0.89, for baseline and 24 months, respectively. The cutoff for clinically significant depressive symptoms is 16. In addition to considering CES-D as a continuous measure, we examined the percentage of participants with depressive symptoms at or above this clinical cutoff.

Mississippi Scale for the Assessment of PTSD—Civilian Form (Keane, Caddell, & Taylor, Reference Keane, Caddell and Taylor1988)

This is a 39-item self-report instrument based on DSM criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD. Ratings are made on a 9-point Likert scale for each item describing symptoms of psychological trauma and distress. The measure has been shown to have acceptable psychometric properties (coefficient α = 0.89) when used with civilian samples. In this sample, the Cronbach's α coefficients were 0.85 and 0.87, for baseline and 24 months, respectively. In terms of clinical cutoffs, psychiatric patients’ average score is 86 (SD = 26), and PTSD patients’ average score is 130 (SD = 18). In addition to considering this as a continuous measure, we examined the percentage of participants with PTSD symptoms at or above the clinical cutoff, namely, psychiatric patients’ average score of 86.

Data analyses

Demographic characteristics were compared between the intervention and control groups. We also compared participant baseline characteristics from CHC Sites 1 and 2, and there were no statistically significant differences between participants in the two sites (see Table 1). Due to the sampling strategy, interclass correlations were calculated to determine whether women within each center were more similar to each other than they were to women in the other center. The largest interclass correlation was .007, suggesting the within-center correlations were low, and therefore it was not necessary to account for center differences in the subsequent analyses (Moneiddon, Matheson, & Glazier, Reference Moineddin, Matheson and Glazier2007).

For all interval-level measures, we used linear regression. For ordered categorical outcome variables (RF and the levels of infant attachment from the Strange Situation at 12 months), we used ordered logistic regression. For attachment, we also compared secure to insecure/disorganized and disorganized to secure/insecure to determine the roles of secure and organized attachment separately. We examined whether intervention effects were moderated in vulnerable subpopulations, such as 14- to 19-year-old mothers and mothers with less than high school education, by testing interactions between these characteristics and the intervention. All primary analyses were conducted with an intent-to-treat approach.

Results

Sample description

Complete sample descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Mothers in the sample were young (mean age 20.4), and a majority was Latina. Slightly more than half reported that they had graduated from high school, and all but four families had income levels that qualified them for the Women Infants and Children's nutritional supplement program. While over 80% of the women were single, more than half reported some father involvement at baseline. There were no significant differences between groups with respect to demographics. Although the difference between MTB and control mothers in baseline level of RF on the PI was not significant (RF/PI; p = .06), we controlled for baseline PI/RF in all remaining analyses. There were no differences in baseline levels of maternal depressive symptoms and PTSD, and so we did not control for these variables.

Participant retention

Attrition

The study attrition rate, the percentage of families who did not complete the study, was 22% for controls and 27% for intervention subjects. The program attrition rate, the percentage of families who did not complete the intervention, as opposed to the study, was 17%; the difference in the program and study attrition rates reflects the fact that of the 68 families who completed the intervention, 8 did not complete the research measures.

Missing data

As our attrition rates indicate, relatively few families declined to continue in this 27-month longitudinal study; there were, however, missing data at each assessment. This despite the fact that we attempted to contact all families at all time points, regardless of prior missed sessions. Missing data were highest at 12–14 months, when attachment was assessed (29% of control group and 36% of MTB group did not complete attachment assessments). Missing data were typically due to housing instability, or significant scheduling problems (changing work hours or other family obligations). In addition, some families would disappear for a time and then return to the study and the intervention. Although such occurrences are likely random, nonrandom reasons are also possible; this implies that methods to manage missing data, such as multiple imputation, are inappropriate.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis #1: The MTB intervention will have a positive impact on the development of maternal RF

We examined whether there were differences between the two groups on level of RF at 24 months, using the PDI (PDI/RF) and controlling for prenatal RF (PI), and found a significant difference (p < .04) between MTB (n = 60) and control (n = 64) mothers in the likelihood of falling into one of four possible RF categories (odds ratio; OR: 2.15; 95% confidence interval; CI [1.02, 4.53]). Participants in the intervention group were 2.15 times more likely than control group participants to be in a higher category of PDI/RF scores (see Figure 2).

Hypothesis #2: MTB dyads will be less likely to have disrupted affective communication

There were no differences between the MTB and control group in affective communication at 4 months, with both MTB (n = 61) and control (n = 63) dyads having a high percentage of disrupted interactions.

Hypothesis #3: MTB infants will be more likely to be securely attached, and less likely to be disorganized

The quality of attachment was compared in intervention and control dyads at 12–14 months across three classifications, and there was a significant difference (p < .01) between children in the intervention and control groups. In addition, examination of odds ratios indicate that infants in the MTB intervention were 2.69 times more likely to be classified as organized (secure or insecure vs. disorganized) than their control group peers, and 2.59 times more likely to be classified as secure (vs. insecure or disorganized) than their control group peers; see Table 2.

Table 2. Comparisons between intervention and control groups on attachment, based on the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP)

Note: Overall main effect, p = .01. P value was obtained from ordered logistic regression, controlling for baseline Pregnancy Interivew. *p < .05.

Hypothesis #4: The MTB intervention will result in lower depression and PTSD symptoms

We first examined whether there were differences between the MTB and control groups in either depressive symptoms or PTSD at baseline and at 24 months (Table 3). There were no differences at baseline. With respect to depressive symptoms at 24 months, there were no significant differences, although MTB mothers’ depressive symptoms scores were lower than those of control mothers at graduation (p = .07). There was not a significant difference between groups over time based on t test of the difference in scores (p = .44). The difference in the percent of scores above the clinical cutoff was in the expected direction (with the MTB percentage of scores above clinical cutoff improving at the end of the intervention), but not significant. There were no associations between baseline PTSD symptoms and PTSD at 24 months in either group (Table 3) or in change between baseline and 24 months by group (t test of difference: p < .88).

Table 3. Comparisons between intervention and control groups on measures of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Note: CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. PI, Pregnancy Interview. RF, reflective functioning. aClinical cutoff is ≥16 for CES-D and ≥86 for PTSD. bLinear regression controlling for baseline PI/RF and baseline values of the predicted measure, except as noted. Effect sizes reported are regression coefficients, except as noted. cLogistic regression; 24-month models include baseline values of the measure predicted as a covariate, and baseline PI. dEffect size is based on regression coefficient, transformed to percentage due to natural-log transformation. This may be interpreted as being in the intervention group decreased CES-D score by 22%. *p < .05.

Exploratory moderation analyses

Using a series of logistic and ordered logistic regressions, we then examined whether baseline PI, maternal age, education, depressive symptoms, and PTSD, as well as relationship quality (AMBIANCE) at 4 months, acted as moderators of intervention effects on PDI/RF, infant attachment, depressive symptoms, or PTSD. We found positive associations across groups between baseline PI/RF (dichotomized at ≤2 vs. >2) and PDI/RF (4 categories) at 24 months (OR: 15.8; 95% CI [4.40, 56.4]), between baseline depressive symptoms and 24-month depressive symptoms, both dichotomized (OR: 6.11; 95% CI [2.47, 15.1]); baseline depressive symptoms and PTSD at 24 months, both dichotomized (OR: 3.13; 95% CI [1.33, 7.36]); and between baseline and 24 month PTSD, both dichotomized (OR: 5.61; 95% CI [2.23, 14.1]).

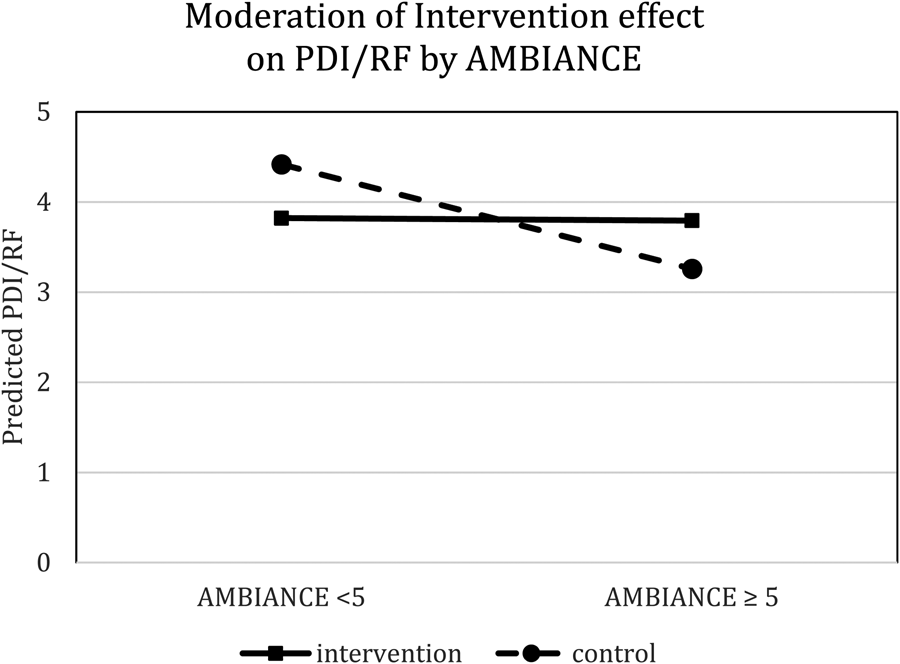

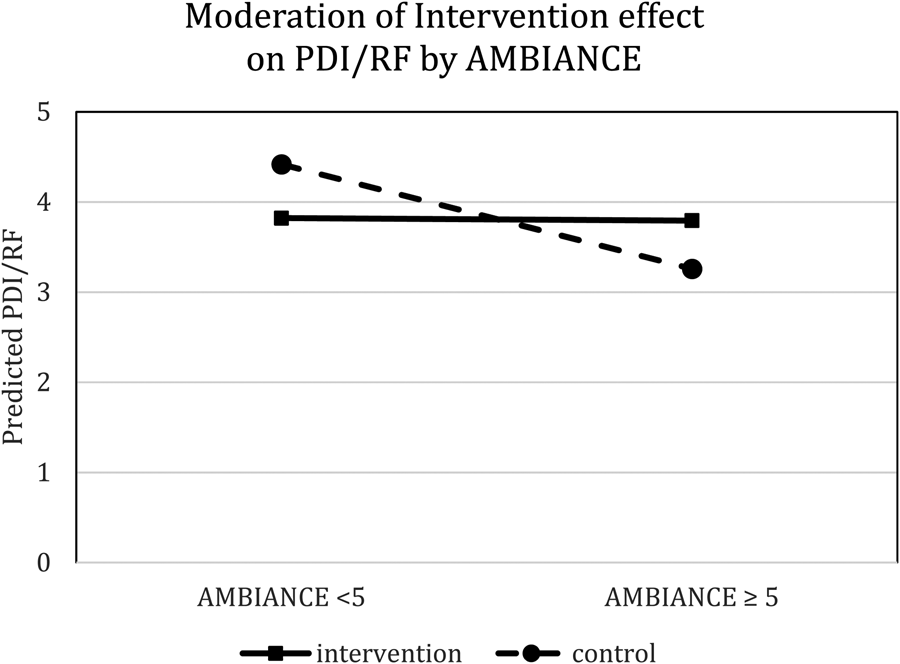

There were no moderation effects for baseline PI, maternal age, education, depressive symptoms, and PTSD on PDI/RF, infant attachment, depressive symptoms, or PTSD. There was evidence of moderation when we analyzed the impact of disrupted communication at 4 months on PDI/RF (interaction coefficient: 2.36; 95% CI [0.45, 4.27]). In the control group, disrupted communication on the AMBIANCE was significantly associated with low PDI/RF levels at 24 months (OR: 0.09; 95% CI [0.02, 0.38]), this being the expected association in the absence of intervention). In the intervention group, however, the level of PDI/RF at 24 months was not affected by the degree of disrupted communication on the AMBIANCE at 4 months. This suggests that MTB might have been protective against the expected negative impact of disrupted affective communication, and is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Predicted Parent Development Interview/reflective functioning, adjusted for baseline Pregnancy Interview/reflective functioning, by Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification Scale and intervention arm.

Discussion

The results of the Phase 2 RCT of MTB confirm many of the Phase 1 RCT findings (Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Slade, Close, Webb, Simpson, Fennie and Mayes2013), namely, that in a predominantly Latina sample of young mothers living below the poverty line, with limited education and other resources, and high levels of early childhood adversity (Albertson, Reference Albertson2016), the MTB intervention enhances two key protective factors: the mother's reflective capacities and the child's attachment security. This despite MTB mothers having low levels of RF during the prenatal period, and disrupted interactions at 4 months (7 months into the intervention). The chronology of positive findings, with secure attachment and maternal RF emerging despite disrupted interactions at 4 months, suggests that intervening across infancy and toddlerhood is key to bringing about long-term effects in both mother and child.

MTB's impact on RF

Mentalization theory (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Leigh, Kennedy, Mattoon, Target, Goldberg, Muir and Kerr1995) and affective neuroscience (Porges, Reference Porges2011) link the ability to engage higher level cortical functions, such as reasoning and planning, with lower levels of acute stress. As Allen (Reference Allen2012) puts it: “Stress is the enemy of mentalization” (p. 79). Thus, when an individual's survival mode, namely, fight, flight, or freezing, is triggered by threat, resulting in the overactivation of the limbic system, reflective processes believed essential to creating a secure and safe base for one's child are impaired. It is for this reason that enhancing parental RF is a goal of many attachment-based interventions aimed at improving outcomes in highly stressed populations (Camoirano, Reference Camoirano2017; Julian, Muzik, Kees, Valenstein, & Rosenblum, Reference Julian, Muzik, Kees, Valenstein and Rosenblum2017; Pajulo et al., Reference Pajulo, Pyykkonen, Kalland, Sinkkonen, Helenius, Punamaki and Suchman2012; Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, Reference Powell, Cooper, Hoffman and Marvin2013; Schechter et al., Reference Schechter, Myers, Brunelli, Coates, Zeanah, Davies and Liebowitz2006; Steele, Steele, Bonuck, Meissner, & Murphy, Reference Steele, Steele, Bonuck, Meissner, Murphy, Steele and Steele2018; Suchman, DeCoste, Castiglioni, et al., Reference Suchman, DeCoste, Castiglioni, McMahon, Rounsaville and Mayes2010; Suchman et al., Reference Suchman, DeCoste, McMahon, Dalton, Mayes and Borelli2017; Suchman, Ordway, de las Heras, & McMahon, Reference Suchman, Ordway, de las Heras and McMahon2016). A small number of noncontrolled studies of vulnerable mothers have reported significant (Pajulo et al., Reference Pajulo, Pyykkonen, Kalland, Sinkkonen, Helenius, Punamaki and Suchman2012; Schechter et al., Reference Schechter, Myers, Brunelli, Coates, Zeanah, Davies and Liebowitz2006; Suchman et al., Reference Suchman, Ordway, de las Heras and McMahon2016) or trend-level (Muzik et al., Reference Muzik, Rosenblum, Alfafara, Schuster, Miller, Waddell and Kohler2015) changes in RF over the course of an intervention. In addition, two randomized trials have documented change in RF over the course of an intervention. Suchman and her colleagues (Suchman et al., Reference Suchman, DeCoste, Castiglioni, McMahon, Rounsaville and Mayes2010; Suchman et al., Reference Suchman, DeCoste, McMahon, Dalton, Mayes and Borelli2017) reported that the RF of mothers increased significantly after participating in a 12-week, mentalization-based individual parenting therapy for substance abusing parents. Sleed, Baradon, and Fonagy (Reference Sleed, Baradon and Fonagy2013) likewise found that participation in an 8-week mentalization-based intervention for mothers and babies in a prison setting was associated with increases in RF. While the interventions, samples, and methods of coding RF differed in these studies, accumulating evidence suggests that a mentalization-based approach with vulnerable mothers is effective in enhancing maternal RF, and that the specific emphasis on RF, as the basis for sensitive responsiveness, is particularly important (Suchman, DeCoste, Rosenberger, & McMahon, Reference Suchman, DeCoste, Rosenberger and McMahon2012).

The accumulating evidence that RF can be enhanced by intervention should not obscure the fact that there are still a number of complexities in measuring this multidimensional construct. As is evident from all the research to date, progress in developing reflective capacities is slow, with mothers rarely increasing more than a scale point over the course of any intervention. In addition, in all studies reviewed here, likely because samples were typically high risk, with high exposure to trauma and other forms of family dysfunction, the range of RF scores was restricted, with mothers hovering toward the low end of the scale, even after intervention (although there were, of course, exceptions). This raises several issues. The RF scale was designed to measure the full range of reflective capacities; thus, the various forms of prementalizing seen in high-risk samples are not distinguished from each other, and are typically assigned the same low score, namely, a 1 or 2. Thus, there would be great value in expanding the lower end of the RF scale to distinguish levels and types of prereflective processes and potentially measure change in a more meaningful way. Recently, Leroux, Terradas, and Grenier (Reference Leroux, Terradas and Grenier2017) described early efforts to develop a prementalizing scale for the PDI. There have also been efforts to develop shorter interview protocols for measuring RF (Ensink, Borelli, Roy, Normandin, Slade, & Fonagy, Reference Ensink, Borelli, Roy, Normandin, Slade and Fonagy2018); these too are in the early stages of development. Two brief screening tools for the assessment of parental RF have been developed in recent years. Pajulo and her colleagues developed the Pregnancy Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (Pajulo et al., Reference Pajulo, Tovalnen, Karlsson, Luyten, Mayes and Karlsson2015). Responses load on three factors: opacity of mental states, reflecting on the fetus–child, and the dynamic nature of mental states. Both total and factor scores were correlated with the PI (Slade, Reference Slade2003). Luyten and his colleagues developed the Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (Luyten, Mayes, Nijssen, & Fonagy, Reference Luyten, Mayes, Nijssens and Fonagy2017) Responses load on three factors: curiosity about mental states, an appreciation of the opacity of mental states, and nonmentalizing modes. It has not yet been validated against the PDI (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Aber, Berger, Bresgi and Kaplan2004). As both Pajulo et al. and Luyten et al. note, neither the Pregnancy Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire nor the Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire is a substitute for in-depth clinical interviews.

MTB's impact on infant attachment

Given that the quality of an infant's attachment is linked to later outcomes, it is unsurprising that many early intervention, and particularly home visiting, programs are attachment-based (see Steele & Steele, Reference Steele and Steele2017, for an overview). Over the past 30 years, a small number of home visiting programs have assessed the quality of attachment directly using the Strange Situation procedure; these include, in addition to MTB, the following home based interventions: Infant–Parent Psychotherapy (IPP),Footnote 3 developed by Fraiberg (Reference Fraiberg1980), and operationalized and tested by Lieberman and her colleagues (Cicchetti et al., Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2006; Lieberman, Weston, & Pawl, Reference Lieberman, Weston and Pawl1991); Dozier and her colleagues’ Attachment Biobehavioral Catchup (ABC) program (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012; Dozier & Bernard, Reference Dozier and Bernard2017); Egeland and Erickson's STEEP program (Egeland & Erickson, Reference Egeland, Erickson, Kramer and Parens1993); Lyons-Ruth and her colleagues’ home visiting intervention (Lyons-Ruth, Connell, & Grunebaum, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Connell and Grunebaum1990); and Heinicke and his colleagues’ UCLA Family Development Project (see Borelli, Bond, Dudley, Ponce, & Mogil, Reference Borelli, Bond, Dudley, Ponce, Mogil, Steele and Steele2018, for a review). These programs vary greatly with respect to the length and intensity of the intervention, as well as the timing of initial implementation (pregnancy, infancy, or toddlerhood); all, however, are geared toward high-risk families living in poverty. Moreover, with the exception of the STEEP program, all have been effective in increasing rates of secure attachment, and lowering rates of disorganized attachment in intervention as compared to control children. When compared with a psychoeducational home visiting intervention, IPP was also found to significantly improve downstream indices of secure attachment, namely, children's representations of the self and mother during the preschool period (Toth, Maughan, Manly, Spagnola, & Cicchetti, Reference Toth, Maughan, Manly, Spagnola and Cicchetti2002).

MTB and ABC are presently the only two of these home visiting programs that are certified as evidence-based by the US Health Services and Research Administration. They are very different programs, however. ABC is a 10-session intervention based on a behavioral model of positive reinforcement that specifically targets three elements of the mother–child interaction: providing nurturance, following the child's lead, and avoiding frightening behavior (Dozier & Bernard, Reference Dozier and Bernard2017). It can be implemented with infants and toddlers, and is delivered by trained bachelor-level coaches. Based on the same set of attachment principles as MTB, ABC has been implemented with similar populations with similar results in the domain of attachment. Comparing these two programs is complex, because while some of the outcomes of the two programs are similar, their aims, broadly speaking, are not. In contrast to ABC, MTB aims to enhance the psychological processes (viz., RF) that underlie sensitive behavior as well as social and relational understanding.

MTB's impact on maternal mental health

While the central aims of MTB are to promote a secure mother–child relationship, many of the mothers in MTB are suffering emotionally, and if clinically evaluated, would likely carry one or more psychiatric diagnoses. However, they come to MTB looking for help becoming parents, not seeking treatment. In addition, even when it is appropriate to refer them for outside treatment, mothers tend to be extremely reluctant to seek psychological services. Mental health treatment is often seen as stigmatizing, and in our experience only a handful of mothers have ever followed up on outside treatment referrals. They have opened up to MTB clinicians, and rarely want to seek other “help.” This is the mental health work they are open to, and given their histories of complex trauma (with depression and anxiety being symptoms of this disorder), the work we do is likely a critical step in preparing them for later targeted treatments (Courtois, Reference Courtois2004).

Thus, following Fraiberg (Reference Fraiberg1980), we think of the mental health aspect of our work as “psychotherapy in the kitchen.” As such, mothers receive ongoing mental health treatment and promotion, intensive casework, and parenting support within the framework of complex and stimulating home environments. While MTB's mental health approaches are informed by evidence-based methods, they are implemented in a flexible way that accords with the family's needs, with the ultimate goal being to create safety, improve relationships and mentalizing capacities, and diminish dysregulated stress responses. Because we do see a number of downstream clinical effects resulting from these interventions (Slade, Simpson, et al., Reference Slade, Simpson, Webb, Albertson, Close, Sadler, Steele and Steele2018), including an increase in reflective capacities, we had hoped that one of the more holistic impacts of MTB would be to improve symptoms of depressive symptoms and PTSD. However, similar to the Phase 1 RCT, we found no significant impacts of MTB on maternal mental health, although the changes were consistently in the expected direction.

Over the course of the study, there were nonsignificant improvements in mean levels of depressive symptoms; that is, scores in the MTB group dropped from 14 to 11, whereas the control dropped only from 14 to 13. In addition, the percentage of MTB mothers’ scores above the clinical cutoff dropped from 39% to 22% over the course of the intervention, whereas the control groups’ percentage remained relatively stable (change from 32% to 33%). The trends raise the possibility that the general impact of MTB on maternal depressive symptoms might be evident in a future, larger sample. Yet, the finding that the New Beginnings program, also mentalization based (Sleed et al., Reference Sleed, Baradon and Fonagy2013), similarly had no significant effects on maternal depression, suggested that improving mentalization and attachment may not necessarily mitigate depression.

The PTSD findings are more ambiguous, for different reasons. Both MTB and control mothers had low rates of PTSD symptomatology as assessed by the Mississippi Scale, and there appeared to be little change in either group over time. The fact that so few mothers reported symptoms of PTSD was surprising, considering that so many of our mothers described having numerous adverse childhood experiences, including physical and sexual abuse, abandonment, extreme poverty, and family dysfunction (Albertson, Reference Albertson2016), and presented with a number of signs of “complex trauma” (Courtois, 20104; van der Kolk, Reference van der Kolk2014) or PTSD, with depression and anxiety being proxies for more pervasive underlying distress and dysregulation (Slade, Simpson, et al., Reference Slade, Simpson, Webb, Albertson, Close, Sadler, Steele and Steele2018).

In our view, the low level of self-reported PTSD may be a measurement problem. When we designed the study in 2001, there were few paper-and-pencil measures appropriate for measuring PTSD in samples of marginalized, culturally diverse inner-city families, as most PTSD measures were derived from studies of veterans. Since then, the understanding of trauma symptomatology and its impact on the parent–child relationship has changed dramatically (Courtois, Reference Courtois2004; Lieberman & Van Horn, Reference Lieberman and Van Horn2008; van der Kolk, Reference van der Kolk2014), and a number of more suitable measures have been developed, including, for example, the PTSD Checklist that is linked to the DSM 5. We are now using this and the Child Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia, Stokes and Zule2003) in our ongoing MTB studies. Unfortunately, however, there are, even now, few reliable and valid instruments for assessing complex trauma.

Why MTB?

Currently, there is understandably considerable impetus to develop and implement short-term effective attachment-based interventions that impact outcomes known to have downstream positive effects (Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017; Dozier & Bernard, Reference Dozier and Bernard2017). Support for this approach comes, in part, from the findings of a 2003 meta-analysis indicating that short-term interventions are more effective than long-term ones (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn and Juffer2003). Support also comes from the obvious differences in the cost and complexity of implementing short- and long-term models. While MTB is an anomaly within this social and economic climate, it is in good company. The Nurse–Family Partnership (NFP; Olds et al., Reference Olds, Robinson, O'Brien, Luckey, Pettitt, Henderson and Talmi2002), one of the inspirations for MTB, is also a 27-month home visiting intervention for highly stressed, marginalized families living in poverty that has been replicated widely and implemented in 42 of the 50 United States and in many countries in Western Europe. Ongoing follow-up research on the original samples continues to demonstrate significant downstream public health outcomes for families seen in NFP (Olds et al., Reference Olds, Holmberg, Donelan-McCall, Luckey, Knudtson and Robinson2014). Child–parent psychotherapy, the other inspiration for MTB, is also a long-term intervention for highly traumatized families that has been tested in a range of RCTs around the world (Lieberman, Ghosh-Ippen, & Van Horn, Reference Lieberman, Ghosh-Ippen and Van Horn2006; Lieberman, Van Horn, & Ghosh-Ippen, Reference Lieberman, Van Horn and Ghosh-Ippen2005; Toth, Michl-Petzing, Guild, & Lieberman, Reference Toth, Michl-Petzing, Guild, Lieberman, Steele and Steele2018; Toth, Rogosch, Manly, & Cicchetti, Reference Toth, Rogosch, Manly and Cicchetti2006).

Often lost in debates about the length and cost of interventions (which are often fueled as much by differences in theoretical orientation and treatment philosophy as by economic considerations) are two key questions: what are the goals of the intervention and for whom is it appropriate? In contrast to many short-term interventions, MTB's goals are broad: to improve health, developmental, attachment, mental health, and life course outcomes in vulnerable families. This is the rationale for the relationship-based, interdisciplinary nature of the intervention, as well as the sustained and intensive 27-month service delivery model. In addition, MTB, like NFP, was designed for families who need a wide level of such supports as they begin the transition to parenthood, helping them build the capacities that will lead to resilience and proactive engagement in their and their children's lives. Parents come to MTB with significant histories of attachment disruption and trauma, both in their own and in previous generations. Many are without the resources to take care of themselves and their families, lacking access to health care, social services, stable housing, and work, besieged by the effects of sustained socioeconomic risk (Cyr et al., Reference Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2010). Their sense of self-efficacy is often profoundly diminished by the circumstances of their lives, and they are at high risk for a number of poor outcomes, limited RF and insecure or disorganized infant attachment being only two domains among many.

We see the relationships that clinicians foster with mothers, children, and families as key to lowering the impact of multiple risk factors. These relationships serve as the foundation for a sense of safety or epistemic trust (Fonagy & Allison, Reference Fonagy and Allison2014), from which all exploration and resolution proceeds (Courtois, Reference Courtois2004; Lieberman et al., 2015; Lieberman & Van Horn, Reference Lieberman and Van Horn2008; van der Kolk, Reference van der Kolk2014). With MTB mothers, establishing relationships can be very challenging, as they are often have little experience trusting and relying on others, and invitations to connect can thus be threatening and triggering. Nevertheless, MTB clinicians aim to provide a secure and safe base for mothers’ developing representations of themselves as able to care and be cared for. They are caring, consistent, and nonjudgmental “angels in the nursery” (Lieberman, Padron, Van Horn, & Harris, Reference Lieberman, Padron, Van Horn and Harris2005), attachment figures who provide the relationship support and sense of safety that is key to biological and psychological reorganization (Holmes & Slade, Reference Holmes and Slade2018), and to buffering the prolonged stress response that can occur with chronic adversity (Shonkoff, Reference Shonkoff2012). They are reflective “others” who are curious about the mother and her experience, modeling the stance that they hope mothers will later adopt with their babies. Clinicians also incorporate “bottom-up” body-based practices to regulate arousal (van der Kolk, Reference van der Kolk2014), such as mindfulness and other stress reduction techniques. Once mothers feel more safe and more regulated, they are more prepared for targeted psychological treatment, and some mothers agree to therapy or counseling at the time of graduation.

MTB begins during the “transition to parenthood,” a sensitive period for the rapid physical, neuroendocrine, neurobiological, emotional, and social reorganization that readies the “parental brain” (Feldman, Reference Feldman2015a) for its work insuring the child's literal survival and entry into the human, social world (see Slade & Sadler, Reference Slade, Sadler and Zeanah2018, for a review). This includes the activation of both neuroendocrine (and specifically oxytocin) systems that ensure attachment and bonding and regulate stress, and dopaminergic reward centers that ensure pleasure in the early mother–child relationship (Feldman, Reference Feldman2015b; Toepfer et al., Reference Toepfer, Heim, Entringer, Binder, Wadhwa and Buss2017). Maternal early life stress as well as stress during the prenatal and postnatal periods (due to socioeconomic adversity, intimate partner violence, or the prolonged stress of hunger and isolation, or internal stressors such as depression, anxiety, or trauma related psychopathology) have a direct impact on “fetal development as well as the quality of postnatal dyadic mother-child interactions” (Toepfer et al., Reference Toepfer, Heim, Entringer, Binder, Wadhwa and Buss2017, p. 293). These maternal stressors also impact a child's capacities for stress and emotion regulation, cognitive functioning, motor development, as well as a range of physiological measures such as birth weight, gestational age, fetal heart rate, and fetal heart rate variability. They also greatly increase risk for psychopathology in the child (see Monk, Spicer, & Champagne, Reference Monk, Spicer and Champagne2012; O'Connor, Monk, & Fitelson, Reference O'Connor, Monk and Fitelson2014, for reviews). Thus, it is key that interventions start before intergenerational cycles of trauma and attachment disruption are set in motion.

Not everyone requires a lengthy, intensive trauma-informed home visiting intervention that is grounded in the development of transformative treatment relationships; not everyone requires interdisciplinary support for a range of health, developmental, and attachment outcomes; and not everyone needs wide support before the baby is born. However, there are parents and children who do. In the United States, intervention choice hinges largely on economics, with states and municipalities typically choosing a single, less expensive model to disseminate broadly. Thus, rather than have clinicians make intervention decisions on the basis of a family's level of need and complexity, such decisions are made by administrators (Condon, Reference Condonin press). In these circumstances, families such as those participating in MTB fall through the cracks: they are not organized enough to participate, or they drop out. Thus, we take the position that to create long-lasting change in truly vulnerable families, and develop capacities that will have significant downstream effects, we must cast a wide net, and begin to intervene early and continuously across the transition to parenthood, a key developmental period for mother, child, and family. In particular, we see the development of reflective capacities as undergirding a number of relational and interpersonal capacities that are broadly protective across the life span.

Strengths and limitations

This study has a number of strengths and limitations. We were able to follow a sample of intervention and control families for 27 months. Our study attrition rates were relatively low and consistent across Phase 1 (27% MTB; 31% controls) and Phase 2 (27% MTB; 22% controls). We were fortunate in being able to use gold standard measures of attachment (Strange Situation), RF (PI and PDI), and parental behavior (AMBIANCE) to directly measure key study constructs. The inclusion of a diverse sample and the fact that our program was embedded in CHCs also enhance the external validity of the findings. Our use of intent-to-treat analyses and the fact that we controlled for baseline levels of study constructs in analyses enhance confidence in the effects we observed.

The limitations of the study were the variable participation in the measurement visits over time. The resulting smaller sample sizes at various time points led to a relative lack of power, and limited certain subgroup analyses. While this is a common artifact of working with families with complex lives and multiple competing demands, it undoubtedly affected our ability to detect more intervention effects. In addition, the number of participants who declined to enroll in our intervention, as well as the rate of attrition over time, undoubtedly introduced some bias into the study because it is likely that those who declined were different in some way from those who participated. Finally, the lack of a suitable measure of PTSD and complex trauma at the time the study was undertaken clearly limited our ability to detect intervention effect on trauma psychopathology. Evaluating the impact of the level of trauma pathology seems crucial to tailoring choice of intervention to the level of a family's need.

Future directions

In future studies, we intend to pair attachment-based and psychosocial measures with biomarkers (measures of cortisol and inflammation) of neurological, endocrine, and immune system functioning. We hope that such efforts will help us to better understand the relations between behavioral measures and the stress regulation system, as well as the degree to which MTB buffers the impact of toxic stress (Shonkoff, Reference Shonkoff2012). We will also explore which of the families we have seen have been most helped by MTB. In addition, we are following the cohort described here longitudinally in order to look for longer lasting and potentially intergenerational effects of this early intensive intervention on both behavioral and biological systems. A follow-up study of the MTB control group revealed evidence of intergenerational transmission of toxic stress (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Holland, Slade, Redeker, Mayes and Sadlerin press); these findings will be compared with outcomes in MTB intervention families in future analyses. Efforts are under way to conduct a cost-analysis of MTB from both Phase 1 and 2 reports, as well as the documented differences in rates of obesity and overweight in MTB toddlers (Ordway et al., Reference Ordway, Sadler, Holland, Slade, Close and Mayes2018), and later prevalence of maternally reported behavior problems (Ordway et al., Reference Ordway, Sadler, Slade, Close, Dixon and Mayes2014).

Conclusions

Over the past decade, both developmental and economic science have made evident the fact that secure infant attachment, positive mother–child interactions, and maternal reflectiveness contribute to noncognitive, socioemotional development, a key ingredient in school success as well as future wellness (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Conti, Heckman, Moon, Pinto, Pungello and Pan2014; Jones, Greenberg, & Crowley, Reference Jones, Greenberg and Crowley2015). From the beginning, laying a solid foundation for both the child's and the mother's socioemotional development and ultimate success has been a key aim of Minding the Baby®. The results of the study presented here suggest that our attempts to promote secure attachment in first children and reflectiveness in young mothers have been fruitful, while at the same time raising questions for future research.

Financial support

This research was supported by NIH/NICHD (RO1HD057947) and NIH/NCRR (UL1 RR024139), and through the generous support of the FAR Fund, the Irving B. Harris Foundation, the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Foundation, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, the Child Welfare Fund, the New York Community Trust, the Edlow Family Foundation, and the Schneider Family.

Acknowledgments

None of this work could have been completed without our remarkable home visitors, Denise Webb, Tanika Simpson, Sarah Fitzpatrick, Bennie Finch, and Rosie Price, or without the support of Emily Bly, Elizabeth Graf, Melissa Ilardi, Crista Marchesseault, Andrea Miller, Patricia Miller, and Jasmine Ueng-McHale. A big thank you to Jessica Borelli for her most helpful read of an earlier version of the manuscript, and to our community partners for their support. Finally, our enormous gratitude to the families who were willing to share their lives and invite us into their homes.