Bullying is a prevalent concern, with approximately one out of three to one out of five adolescents between the ages of 12–18 reporting being victimized (Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra, & Runions, Reference Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra and Runions2014; Musu, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, & Oudekerk, Reference Musu, Zhang, Wang, Zhang and Oudekerk2019). Bullying is a form of peer victimization that includes three components of (a) unwanted aggressive behavior done with intent to harm, (b) perpetrated by a peer or group of peers where there is an imbalance of power, and (c) repetition over time (Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger, & Lumpkin, Reference Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger and Lumpkin2014; Olweus, Reference Olweus, Smith, Morita, Junger-Tas, Olweus, Catalano and Slee1999). Aggressive acts perpetrated by a peer that do not include all three of these components are referred to more broadly as peer victimization. Although multiple studies have linked both peer and bullying victimization to internalizing problems and depressive symptoms (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd, & Marttunen, Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010), this relationship is complex with regard to stability of these constructs, predictive and simultaneous influences, mediating factors (e.g., family cohesion), and age and sex effects. Further, there is a lack of research examining these processes using a random intercepts cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Hamaker, Kuiper, & Grasman, Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman2015), which overcomes limitations of the traditional cross-lagged panel models (CLPM) by parceling out between-person (i.e., stable, time-invariant) and within-person variance (i.e., dynamic, time-varying) through the inclusion of random intercepts. In this study, we used a RI-CPLM to investigate whether peer victimization for a participant predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms at a subsequent time point beyond what would be expected for this participant (as opposed to the sample mean). We also investigated the role of family cohesion in the relation between peer victimization and depressive symptoms. To obtain a more precise understanding of these processes, we further investigated the moderating effects of sex and victimization status (i.e., bullying victimization vs. peer victimization).

The relation between peer victimization and depressive symptoms

Peer victimization and internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, negative affect) are consistently related in meta-analyses (e.g., Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim, & Sadek, Reference Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim and Sadek2010; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010; van Geel, Goemans, Zwaanswijk, Gini, & Vedder, Reference van Geel, Goemans, Zwaanswijk, Gini and Vedder2018). There is evidence for a reciprocal relationship, where peer victimization predicts later depression (r = .18), and, after controlling for peer victimization, depression also predicts later peer victimization (r = .08; standardized beta coefficients and odds ratios (ORs) converted to r in Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010's meta-analysis). Daily diary studies also reveal that bullying victims report more sadness and negative affect on the day victimization occurs (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Derrick, Testa, Wang, Nickerson, Espelage and Miller2019; Morrow, Hubbard, Barhight, & Thomson, Reference Morrow, Hubbard, Barhight and Thomson2014; Nishina, Reference Nishina2012), indicating proximal effects.

There are three theoretical models for understanding the relation between peer relationships and depressive symptoms, including: (a) an interpersonal risk model, where peer relationship problems and victimization are stressors that precede depressive symptoms; (b) a symptoms-driven model, in which depressive symptoms interfere with peer relations and contribute to victimization; and (c) a transactional model, where peer victimization and depression are reciprocally related across time, each perpetuating the other (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Kochel, Ladd, & Rudolph, Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012). The transactional model is inclusive of both directions of effects and thus can be considered a combination of the interpersonal risk and symptoms-driven models. It is particularly important to test these theories during adolescence, as this is a critical developmental period for emerging depressive symptoms and the importance of peer relations (Desjardins & Leadbeater, Reference Desjardins and Leadbeater2011; Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, Reference Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon and Aikins2005).

According to the interpersonal risk model, poor peer relations, including rejection, low acceptance, and peer victimization, are significant stressors that thwart the basic need to belong and cause depression (Baumeister & Leary, Reference Baumeister and Leary1995). There is empirical support for the interpersonal risk model, including studies of students in mid-to late-elementary school examining these relations over a one-year period finding that peer victimization predicts subsequent depressive symptoms (Panak & Garber, Reference Panak and Garber1992; Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto, & Toblin, Reference Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto and Toblin2005). Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, and Bates (Reference Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit and Bates2015) used multilevel modeling, revealing that peer victimization in 3rd and 4th grade led to within-person increases in mother-rated internalizing problems over a 9-year period spanning into late-adolescence. Peer rejection in middle school also predicts later depression (Nolan, Flynn, & Garber, Reference Nolan, Flynn and Garber2003; Vernberg, Reference Vernberg1990). Cross-lagged studies have also found that victimization predicts subsequent depression across early- to mid-adolescence (e.g., Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010), with Kaltiala-Heino et al. (Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010) finding that involvement in bullying served as more of an independent risk factor for later depressive symptoms for boys. Some longitudinal studies, however, have not found peer victimization to predict subsequent depression (Healy & Sanders, Reference Healy and Sanders2018; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Craven, Parker, Parada, Guo, Dicke and Abduljabbar2016). Overall, findings suggest that peer victimization leads to later depression, although this has been studied primarily with regard to peer victimization and rejection for students in childhood and early adolescence.

The underlying assumption of a symptoms-driven model is that depressive symptoms drive peer victimization experiences, exclusion, and isolation (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012). Relatedly, scar theories of depression indicate that internalizing symptoms lead to long-lasting problems, in part due to the symptoms’ interference with the ability to develop social skills and healthy relationships (Rohde, Lewinsohn, Tilson, & Seeley, Reference Rohde, Lewinsohn, Tilson and Seeley1990). There is a burgeoning body of research finding that depressive symptoms precede peer relation problems and victimization (Bilsky et al., Reference Bilsky, Cole, Dukewich, Martin, Sinclair, Tran and Maxwell2013; Chen & Li, Reference Chen and Li2000; Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Ladd and Rudolph2012; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Craven, Parker, Parada, Guo, Dicke and Abduljabbar2016; Prinstein et al., Reference Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon and Aikins2005; Schacter, White, Chang, & Juvonen, Reference Schacter, White, Chang and Juvonen2015; Tran, Cole, & Weiss, Reference Tran, Cole and Weiss2012), supporting a symptoms-driven model. Marsh et al. (Reference Marsh, Craven, Parker, Parada, Guo, Dicke and Abduljabbar2016) studied Australian adolescents at six time periods over two years, finding that prior depression had a significant effect on subsequent victimization. In Schacter et al.'s (Reference Schacter, White, Chang and Juvonen2015) study, victimization from one time point to another was partially mediated by depressive symptoms and self-blame. Some theorists and researchers have asserted that depressive symptoms may be a selective factor or sign of vulnerability for peers to target through bullying (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Craven, Parker, Parada, Guo, Dicke and Abduljabbar2016; Tran et al., Reference Tran, Cole and Weiss2012). The symptoms-driven model may be moderated by sex, although findings have been inconsistent. Some studies finding this relation include female-only samples (e.g., Prinstein et al., Reference Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon and Aikins2005) or find that depression precedes victimization for girls but not boys (Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010), whereas others find the predictive association of depressive symptoms with victimization one year later to be stronger for boys than girls (Tran et al., Reference Tran, Cole and Weiss2012).

It should be noted that although most studies testing these theories do not explicitly parcel out within-person variance, there is some evidence that the stability of these constructs is important (Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010; Schacter et al., Reference Schacter, White, Chang and Juvonen2015). For example, in the Kaltiala-Heino et al. (Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010) study, peer victimization at age 15 predicted depression at age 17 for boys (OR = 4.6), but depression at age 15 led to higher likelihood of being depressed at age 17 (OR = 6.6 for boys), particularly for girls (OR = 13.4). In terms of the stability of victimization, hierarchical regression analyses with a middle school sample revealed that although depressive symptoms in the fall predicted peer victimization in the spring (β = .12), peer victimization in the fall was a stronger predictor (β = .42). In addition, some studies indicate that internalizing symptoms do not predict victimization and rejection (Healy & Sanders, Reference Healy and Sanders2018; Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Flynn and Garber2003).

The transactional model conceptualizes the relation between victimization and depression as reciprocal (i.e., a combination of the interpersonal risk and symptoms-driven models), where individuals with depressive symptoms experience peer relation difficulties (e.g., victimization), which in turn perpetuate and intensify depressive symptoms (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Sameroff & Mackenzie, Reference Sameroff and Mackenzie2003). In a large sample of Swiss adolescents (mean age of 13) studied four times in 6-month intervals, associations between victimization and depressive symptoms were bidirectional and positive at each wave (Burke, Sticca, & Perren, Reference Burke, Sticca and Perren2017). In a large sample of Scottish adolescents, victimization and depression were reciprocally predicted from ages 11–13, but depression at age 13 was a stronger predictor of victimization at age 15 (particularly for boys), rather than the inverse smaller effect (Sweeting, Young, West, & Der, Reference Sweeting, Young, West and Der2006). Davis et al. (Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019) used an auto-regressive latent trajectory model with structured residuals (ALT-SR; Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane, & McGinley, Reference Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane and McGinley2014), which allows for the disaggregation of between-person from within-person variance, to test all three of the aforementioned models in a sample of 11- to 15-year-old students. At the between-person level, higher bullying victimization was associated with more depression, and the within-person analyses supported the transactional model for the relation between depression and victimization; in addition, the symptoms-driven and interpersonal risk models were supported for girls but not for boys.

In sum, there has been mixed support for all three of these models (i.e., interpersonal risk, symptoms-driven, and transactional). This suggests there are other factors operating that can serve to exacerbate or mitigate the association between peer victimization and depressive symptoms, or that the association only holds under certain conditions. There is a need for more research to examine the potential mechanisms that underlie this association. Studies are also needed that use advanced statistical approaches to disentangle between-person and within-person variance to better understand these relations around the overall average but also for an individual's own trajectory (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019).

Role of family cohesion in relation between peer victimization and depression

Although numerous studies have focused on the relations between peer victimization and depression, very few have integrated mediating factors (e.g., family cohesion, school belonging, social support) in longitudinal models, as most studies use cross-sectional designs or make estimates without disentangling between-person and within-person variance (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019). Stressful experiences such as peer victimization can certainly change or influence aspects of family support (e.g., family cohesion), which in turn can impact outcomes such as depression (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Compas, Stuhlmacher, Thurm, McMahon and Halpert2003). The role of family cohesion as a factor that may lead to decreased victimization, as well as decreased depression both directly and indirectly, was the focus of this study.

Family cohesion, also referred to as connectedness (Reinherz et al., Reference Reinherz, Stewart-Berghauer, Pakiz, Frost, Moeykens and Holmes1989), includes affective qualities in a family relationship, such as support, affection, and helpfulness (Baer, Reference Baer2002). A number of correlational studies have found that family cohesion is correlated inversely with adolescents’ internalizing behaviors, including depression and withdrawal (Barber & Buehler, Reference Barber and Buehler1996; Farrell & Barnes, Reference Farrell and Barnes1993; Manzi, Vignoles, Regalia, & Scabini, Reference Manzi, Vignoles, Regalia and Scabini2006; McKeown et al., Reference McKeown, Garrison, Jackson, Cuffe, Addy and Waller1997; Reinherz et al., Reference Reinherz, Stewart-Berghauer, Pakiz, Frost, Moeykens and Holmes1989), consistent with social support theory (Farrell & Barnes, Reference Farrell and Barnes1993). Sex differences have been inconsistent, where the inverse relation between family cohesion and depression is stronger for girls rather than boys (Wentzel & Feldman, Reference Wentzel and Feldman1996), whereas in other studies lower family cohesion predicted depressive symptoms for adolescent boys but not girls (Queen, Stewart, Ehrenreich-May, & Pincus, Reference Queen, Stewart, Ehrenreich-May and Pincus2013).

Fewer studies have used longitudinal designs when studying family cohesion, but extant research has indicated that increased family cohesion predicted fewer depressive symptoms in female adolescents (McKeown et al., Reference McKeown, Garrison, Jackson, Cuffe, Addy and Waller1997; White, Shelton, & Elgar, Reference White, Shelton and Elgar2014), although these inverse associations were stronger when assessed concurrently (McKeown et al., Reference McKeown, Garrison, Jackson, Cuffe, Addy and Waller1997). In order to test theoretical relations (e.g., deterioration in family cohesion negatively impacting adolescents’ internalizing symptoms), it is important to focus on within-family processes controlling for between-family differences (Mastrotheodoros, Canário, Gugliandolo, Merkas, & Keijsers, Reference Mastrotheodoros, Canário, Gugliandolo, Merkas and Keijsers2020). Using a RI-CLPM to study longitudinal relations between family functioning (including family cohesion) and internalizing and externalizing problems in a sample of Greek adolescents (mean age 15.73) at three points over 12 months, Mastrotheodoros et al. (Reference Mastrotheodoros, Canário, Gugliandolo, Merkas and Keijsers2020) found no significant within-person estimates between family functioning and internalizing symptoms. Interestingly, when the authors conducted alternative models using traditional CLPM, they found between-person associations; adolescents who reported higher depressive symptoms at earlier waves (compared to adolescents with lower depressive symptoms) reported lower family functioning at subsequent waves, although family functioning did not predict depressive symptoms at subsequent waves. The authors concluded that associations between family functioning and internalizing and externalizing problems are not a within-family process in which adolescent behavior and family systems affect each other, but rather may reflect stable differences between families. In other words, these family processes may only be meaningful when the group is taken into account, reflecting that adolescents who develop more symptoms of depression are statistically at higher risk for problems with family functioning compared to their peers that do not experience increased depressive symptoms, but the relation is not causal (Mastrotheodoros et al., Reference Mastrotheodoros, Canário, Gugliandolo, Merkas and Keijsers2020).

With regard to family support and cohesion in relation to peer victimization, most studies have found an inverse association (Albayrak, Biçer, & Aşık, Reference Albayrak, Biçer and Aşık2014; Forster et al., Reference Forster, Dyal, Baezconde-Garbanati, Chou, Soto and Unger2013; Lereya, Samara, & Wolke, Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Van Hoof, Raaijmakers, Van Beek, Hale, & Aleva, Reference Van Hoof, Raaijmakers, Van Beek, Hale and Aleva2008). Cross-sectional studies with adolescents experiencing peer victimization have also found this inverse association between family support and cohesion in relation to internalizing symptoms (Egon, Marius, & Herbert, Reference Egon, Marius and Herbert2018; Foster et al., Reference Foster, Horwitz, Thomas, Opperman, Gipson, Burnside and King2017; Van Hoof et al., Reference Van Hoof, Raaijmakers, Van Beek, Hale and Aleva2008). Some longitudinal studies have also found the family environment (e.g., more family support, lower conflict with parents, less victimization by siblings) for victimized youth relates to decreased depression and delinquency one year later (Sapouna & Wolke, Reference Sapouna and Wolke2013), and also decreases the need for long-term social welfare benefits (Strom, Thoresen, Wentzel-Larsen, Sagatun, & Dyb, Reference Strom, Thoresen, Wentzel-Larsen, Sagatun and Dyb2014).

Despite the need for studying theoretical relations and processes, there are very few studies that have examined mediation in the relations between victimization, depression, and social support and no known studies to date have parceled out between and within-person differences. Forster et al.'s (Reference Forster, Dyal, Baezconde-Garbanati, Chou, Soto and Unger2013) study of Hispanic adolescents found that although lower family cohesion in ninth grade predicted higher depression in tenth grade, this relation was mediated by bullying victimization, which accounted for 24% of the variance in the relation between family cohesion and depression. In studies of the mediating role of family support in the relation between bullying victimization and later depression, a cross-sectional study with pre-adolescents found victimization to lead to decreased social support, which in turn related to more depression (Pouwelse, Bolman, Lodewijkx, & Spaa, Reference Pouwelse, Bolman, Lodewijkx and Spaa2011), although a longitudinal study revealed that family support in mid-adolescence neither mediated nor moderated the relation between bullying victimization in late childhood and depressive symptoms in late adolescence (van Harmelen et al., Reference van Harmelen, Gibson, St Clair, Owens, Brodbeck, Dunn and Goodyer2016).

Overall, there is clear and consistent evidence from cross-sectional studies that family cohesion correlates inversely with adolescents’ internalizing symptoms (Barber & Buehler, Reference Barber and Buehler1996; Farrell & Barnes, Reference Farrell and Barnes1993; Manzi et al., Reference Manzi, Vignoles, Regalia and Scabini2006; McKeown et al., Reference McKeown, Garrison, Jackson, Cuffe, Addy and Waller1997; Reinherz et al., Reference Reinherz, Stewart-Berghauer, Pakiz, Frost, Moeykens and Holmes1989), although a longitudinal study that disentangled between-person variance from within-person variance did not find this in the within-person analyses (Mastrotheodoros et al., Reference Mastrotheodoros, Canário, Gugliandolo, Merkas and Keijsers2020). Similarly, family cohesion and support are related inversely to peer victimization (Albayrak et al., Reference Albayrak, Biçer and Aşık2014; Forster et al., Reference Forster, Dyal, Baezconde-Garbanati, Chou, Soto and Unger2013; Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Samara and Wolke2013; Van Hoof et al., Reference Van Hoof, Raaijmakers, Van Beek, Hale and Aleva2008). Although a cross-sectional mediation study indicated that victimization decreases social support and in turn increases depression (Pouwelse et al., Reference Pouwelse, Bolman, Lodewijkx and Spaa2011), a longitudinal study did not find a mediating role of family support in the relation between bullying victimization and depression in late adolescence (van Harmelen et al., Reference van Harmelen, Gibson, St Clair, Owens, Brodbeck, Dunn and Goodyer2016). There is a clear need to investigate the transactional relations between family cohesion, depression, and victimization using longitudinal designs that disentangle within-person and between-person effects to allow for better testing of these processes within an adolescent's own trajectory.

Distinctions between bullying and peer victimization

Existing studies on the relations between victimization, depression, and the potential role of family cohesion do not differentiate bullying from other forms of peer victimization. As stated previously, bullying is a form of peer victimization that involves an intent to harm, imbalance of power, and repetition (Gladden et al., Reference Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger and Lumpkin2014; Olweus, Reference Olweus, Smith, Morita, Junger-Tas, Olweus, Catalano and Slee1999). Together, the three components of bullying make it distinct from other forms of peer victimization and aggression (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim and Sadek2010; Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong, & Tanigawa, Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011; Gladden et al., Reference Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger and Lumpkin2014).

Despite this differentiation of bullying from other forms of peer victimization, there is great variation in the measurement of bullying, particularly with regard to the repetition and power imbalance criteria (Cascardi, Brown, Iannarone, & Cardona, Reference Cascardi, Brown, Iannarone and Cardona2014; Felix et al., Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011). Studies that include a single or infrequent experience of unwanted aggression yield higher prevalence rates of bullying (Bear, Mantz, Glutting, Yang, & Boyer, Reference Bear, Mantz, Glutting, Yang and Boyer2015; Blake, Lund, Zhou, Kwok, & Benz, Reference Blake, Lund, Zhou, Kwok and Benz2012; Swearer, Wang, Maag, Siebecker, & Frerichs, Reference Swearer, Wang, Maag, Siebecker and Frerichs2012) than those that use frequency criteria of at least two or more times per month (Felix et al., Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011; Solberg & Olweus, Reference Solberg and Olweus2003). Measures that include a single question about bullying victimization also yield lower prevalence rates than those that include several items of bullying specific behaviors (Bear et al., Reference Bear, Mantz, Glutting, Yang and Boyer2015). When the term bully is defined, self-reported bullying rates are lower (Kert, Codding, Tryon, & Shiyko, Reference Kert, Codding, Tryon and Shiyko2010; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, McDougall, Hymel, Krygsman, Miller, Stiver and Davis2008). Few measures assess power imbalance, although asking about differential power led to more accurate classifications of peer-nominated bullying (Ybarra, Boyd, Korchmaros, & Oppenheim, Reference Ybarra, Boyd, Korchmaros and Oppenheim2012). Although these measurement issues impact prevalence rates, Cook et al.'s (Reference Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim and Sadek2010) meta-analysis of predictors of victimization did not find moderating effects of measurement in terms of labels, definitions, and descriptions in bullying compared to peer victimization. The variation in measurement and the lack of assessment of all three components of bullying may be one of the reasons for the mixed findings in the relations between victimization, depression, and social support discussed previously. The current study examined whether type of victimization (i.e., bullying victimization vs. peer victimization) moderated the role of family cohesion in the relation between peer victimization and depressive symptoms.

Current study

The primary aim of the current study is to make a nuanced examination of the relations among peer victimization, family cohesion, and depressive symptoms over time. The current study extends present understandings of the association between victimization and depression through use of the RI-CLPM, which permits the examination of both individual and between group level changes in peer victimization, family cohesion, and depressive symptoms over time. Prior longitudinal research examining these relations have relied on traditional cross-lagged panel models (e.g., Bilsky et al., Reference Bilsky, Cole, Dukewich, Martin, Sinclair, Tran and Maxwell2013; Sweeting et al., Reference Sweeting, Young, West and Der2006), which is problematic as this model assumes there are not trait-like individual differences in the constructs (Hamaker et al., Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman2015). We posit that these relations should be re-examined with rigorous methodology that allows us to account for the trait-like components of each construct to better examine how peer victimization, family cohesion, and depressive symptoms influence each other over time.

We hypothesized that we would find support for a transactional relationship, with victimization predicting subsequent depression, which in turn would be associated with victimization at a later time point (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Sticca and Perren2017; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Sweeting et al., Reference Sweeting, Young, West and Der2006). It was anticipated that depression would predict later victimization in our adolescent sample, and that this finding may be more pronounced for girls (Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010; Prinstein et al., Reference Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon and Aikins2005). We further expected that depression would be a consistent predictor of subsequent depression, particularly for girls (Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010) and that peer victimization would also predict later victimization (Schacter et al., Reference Schacter, White, Chang and Juvonen2015). With regard to family cohesion, we hypothesized that family cohesion would be inversely related to internalizing symptoms (McKeown et al., Reference McKeown, Garrison, Jackson, Cuffe, Addy and Waller1997; White et al., Reference White, Shelton and Elgar2014) and peer victimization at the between-person level (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Dyal, Baezconde-Garbanati, Chou, Soto and Unger2013; Sapouna & Wolke, Reference Sapouna and Wolke2013). We also expected family cohesion to mediate the relation between victimization and depression, with victimization decreasing subsequent family cohesion, and higher family cohesion, in turn, predicting less depression based on theory and some past research (Egon et al., Reference Egon, Marius and Herbert2018; Sapouna & Wolke, Reference Sapouna and Wolke2013; Van Hoof et al., Reference Van Hoof, Raaijmakers, Van Beek, Hale and Aleva2008), although we anticipated these effects may not hold at the within-person, longitudinal level (Mastrotheodoros et al., Reference Mastrotheodoros, Canário, Gugliandolo, Merkas and Keijsers2020; van Harmelen et al., Reference van Harmelen, Gibson, St Clair, Owens, Brodbeck, Dunn and Goodyer2016). Finally, we examined the moderating role of sex and victimization status among these relations; however, given the mixed findings in the research literature, we had no specific hypotheses other than the sex differences mentioned above.

Method

Participants and recruitment

A community sample of adolescents (N = 801, 57% female) were recruited between October of 2014 and June 2016 to participate in a study of Teen Relationships and Health. Participants were between 13 and 15 years of age (M = 14.45, SD = 0.85) at baseline recruitment. Consistent with the demographics of the county from which they were drawn, 6.6% of participants self-identified as Hispanic/Latino, 81% as White, 12% as Black/African American, 4% as multiracial, 1% Asian, and <1% as Native American. Participants were in 7th (7%), 8th (32%), 9th (35%), 10th (23%), and 11th (2%) grades and attended a public (85%), private (12%) or charter school (3%). Seventy-five percent of adolescents came from two-parent homes with a median income of $80,000 or higher.

Procedure

Recruitment

Address-based sampling was used to recruit adolescent participants from a large county in Western New York State. Mailing lists were purchased from Click2Mail, a company that collates targeted mailing lists based on publicly available data. The lists comprised household addresses from neighborhoods that contained a high concentration of families with children in the targeted age range. Additional sample targeting households in urban communities and with high concentrations of ethnic and racial minorities was also purchased. At least two mailings were sent to each household on the lists, with up to four mailings for addresses in ethnically diverse and low-income neighborhoods. Mailings were addressed to the head of household or current resident. The first mailing consisted of a recruitment packet describing the study, and an invitation to participate along with study contact information (phone, e-mail, US mail). Two weeks later, a postcard was sent to the same addresses, thanking those who had responded and encouraging those who had not yet responded to contact the study. For more difficult to reach samples, a second round of letters and postcards was sent to households that had not responded to the first mailing approximately one year later.

Individuals who responded to mailings were screened for eligibility over the phone. To be eligible, adolescents had to be between the ages of 13 and 15 years, attending a public, charter, or private school (i.e., not home schooled), and living with a mother or legal female guardian. Out of 1,152 individuals who responded to the mailing, 916 met eligibility criteria and were enrolled in the study. Of these, 29 who screened eligible declined to participate and 86 adolescents who were sent links failed to complete the baseline survey. A total of 801 adolescents completed the baseline surveys.

Survey

The web-based surveys were administered using a secure server. Prior to beginning the survey, electronic parental consent and adolescent assent were obtained. Surveys completed by adolescents assessed demographics, family cohesion, victimization and perpetration of peer aggression, and internalizing symptoms. Mothers provided demographic information (e.g., family income) at baseline only. Following completion of the baseline survey, every six months over the next two years adolescent participants completed a similar follow-up survey, for a total of five waves of data. Each survey took about 1 ½ hours to complete and participants received a $25 check for their participation in each wave. All procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board. Retention across the five waves was excellent: 93.9% at Wave 2, 91.9% at Wave 3, 90.4% at Wave 4, and 89.5% at Wave 5.

Measures

Demographics

Adolescents reported their date of birth, sex, race and ethnicity, and year in school at baseline. Mothers provided data on family income at baseline; all other data were provided by adolescent participants. At each wave, participants indicted whether they lived with their mother, father, both parents, or someone else. A dichotomous family composition variable (living with both parents yes/no) was created for each time point and used to control for changes in family composition over time.

Bullying and peer victimization

The California Bully Victimization Scale (CBVS; Felix et al., Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011) was used to assess bullying and peer victimization perpetrated by and against peers in the past six months. The measure consists of six items to assess verbal, relational, and physical bullying. This measure captures characteristics needed to meet the definition of bullying. Intentionality is assessed by specifying that each behavior was done “in a mean or hurtful way.” The frequency of each experience was assessed (e.g., “In the past 6 months, how often have you been… in a mean or hurtful way”), with responses including 0 = never happened, 1 = less than once a month, 2 = about once a month, 3 = 2 or 3 times per month, 4 = about once a week, 5 = several times per week, and 6 = every day or almost every day. These six items were utilized as indicator variables for the victimization latent construct (i.e., bullying and peer victimization). The CBVS is a commonly used measure of peer victimization and has established evidence of test–retest reliability and concurrent and predictive validity (Felix et al., Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted for the current study with the total sample at baseline initially did not indicate adequate fit, χ2 (9) = 102.716, p < .001, comparative fit index (CFI) = .807, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .114, standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = .079. Modification indices indicated a relation among three items assessing an aspect of physical bullying (i.e., being physically hurt, having things stolen or damaged, or being threatened). When these items were allowed to covary; the CFA indicated good fit to the data, χ2 (6) = 21.14, p < .01, CFI = .969, RMSEA = .056, SRMR = .030. These modifications were kept in the model as it theoretically makes sense for items assessing physical bullying to have an association with one another.

At baseline, participants were categorized as “bully victims” if all three criteria for bullying were met. That is, they experienced intentionally mean and hurtful behavior from peers two or more times a month (or three or more types of bullying one time a month) in which there was a perceived power differential (n = 196). Power imbalance was assessed with six questions through which the respondent compares themselves with the perpetrator (e.g., “How popular is this student?” Responses were 1 = less than me, 2 = same as me, 3 = more than me, 4 = not sure, and 5 = does not apply). Power differential was a dichotomized score (0 = no, 1 = yes) if the perpetrator was rated as being “More than me” on at least one item. Participants were categorized as “peer victims” if they experienced intentional peer aggression at levels that did not meet the frequency and power differential criteria needed to be classified as bullying. Those classified as peer victims experienced peer aggression one or more times a month, but there was no power differential (n = 295).

Family cohesion

Family cohesion was assessed with 10 items from the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES III; Olson, Portner, & Lavee, Reference Olson, Portner and Lavee1985). Participants reported how frequently (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always) family members act cohesively. (e.g., “We like to do things with just our immediate family.”). This scale has been validated for use as a global indicator of social support within a family (Farrell & Barnes, Reference Farrell and Barnes1993) and prior research has found evidence of high internal consistency (α = .83 to .86; Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, Reference Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell and Dintcheff2006). A CFA conducted for the current study with baseline data indicated acceptable model fit (χ2 [35] = 184.22, p < .001, CFI = .958, RMSEA = .073, SRMR = .033).

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Short Form (CESD-10; Bradley, Bagnell, & Brannen, Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010), a 10-item self-report measure, was used to assess depressive symptoms experienced in the past week. Responses were on a 4-point (0–3) ordinal scale “rarely or none of the time (<1 day), some or a little of the time (1–2 days), occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3–4 days), most or all of the time (5–7 days).” Scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating more symptoms. Although the CESD-10 is not used for diagnostic purposes, at baseline, 32% of the sample had a score of 10 or higher, indicating a clinically significant level of depressive symptoms. Prior research has found high internal consistency (α = .87) and the CESD-10 has been validated for use with adolescents (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010). A CFA conducted for the current study with baseline data initially did not indicate good model fit, χ2 (35) = 212.62, p < .001, CFI = .887, RMSEA = .080, SRMR = .060. Examination of factor loadings indicated low loadings (<.30) for the item assessing “everything I did was an effort” and for a reverse coded item “I felt hopeful about the future.” Low loadings on these items have been commonly identified in the literature (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010; Chen & Mui, Reference Chen and Mui2014; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Prencipe, Hjelm, Peterman, Handa and Palermo2018; Lee & Chokkanathan, Reference Lee and Chokkanathan2008; Mohammadreza et al., Reference Mohammadreza, Nguyen, McNeil, Woods, Nelson and Shah2018). These items were deleted; the CFA then indicated acceptable model fit, χ2 (20) = 61.37, p < .001, CFI = .968, RMSEA = .051, SRMR = .032.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used to calculate descriptive statistics and Mplus version 8.0 was used for all main analyses. The maximum likelihood robust estimator (MLR) was used in Mplus to account for nonnormality and full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) for handling missing data. Seventy-five percent of the sample (n = 597) completed all five waves of data collection. We first investigated model fit of the measurement model and measurement invariance across time, sex, and victimization group. Model fit was evaluated by examining chi-square statistics, the CFI, the root RMSEA, and the SRMR. RMSEA and SRMR values below .08 and CFI values above .90 are considered adequate model fit (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen2008). Examining measurement invariance involved comparing an unconstrained model that specified the same factor structure for each group (i.e., configural model) to a model that constrained factor loadings (i.e., metric model) and intercepts (i.e., scalar model) across groups. As recommended by Cheung and Rensvold (Reference Cheung and Rensvold2002), ΔCFI > .01 and ΔRMSEA > .015 were used as criteria for determining invariance. We then estimated the RI-CLPM, which accounts for the trait-like components of each construct over time through the inclusion of a random intercept for each construct (i.e., peer victimization, depressive symptoms, family cohesion; Hamaker, Reference Hamaker2018). See Figure 1 for our conceptual model of the RI-CLPM. We compared the fit of the CLPM and RI-CLPM (i.e., nested models) and constrained auto-regressive paths, cross-lagged paths, and within-wave covariances across time points to be equal and compared model fit with the freely estimated models. The Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square difference test was used for all chi-square difference testing. In order to examine sex differences, we conducted a multi-group RI-CLPM in which paths and covariances were constrained to be equal across sex in one model and freely estimated in another model. Chi-square difference testing was conducted to examine differences in model fit. The same procedure was utilized to examine differences by victimization status (i.e., “peer victims” and “bullying victims”) based on baseline CBVS scores. Family composition (living with parents yes/no) was included as a covariate for all models.

Figure 1. Conceptual random intercepts cross lagged panel model depicting the relation between peer victimization (PV), family cohesion (Fam) and depressive symptoms (Dep) across five waves. Note. Observed variables not shown. Circles represent latent constructs. Specific time points are indicated by numbers after PV, Fam, and Dep.

Results

Table 1 provides means, standard deviations, and response rates for all variables at each time point by total sample, sex, and victimization status. Tables 2 and 3 provide bivariate correlations among all variables and variances/covariances of the random intercepts, respectively. Thirty percent (30%) of the variance in peer victimization, 12% of depressive symptoms, and 42% of family cohesion was explained by trait-like elements (i.e., differences at the between-person level). At the between-person level (i.e., trait-like elements), covariances among the random intercepts indicated that peer victimization and depressive symptoms were significantly and positively correlated (r = .47, SE = .05, p < .001) and family cohesion was significantly negatively correlated with peer victimization (r = −.27, SE = .05, p < .001) and depressive symptoms (r = −.52, SE = .05, p < .001), as expected. Family composition (covariate) was significantly associated with family cohesion at T1 to T4 (.54, .42, .37, .45, respectively, p < .001) for males only.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for total sample, by sex, and by victim status

Note. T1 = Time 1. T2 = Time 2. T3 = Time 3. T4 = Time 4. T5 = Time 5.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations for total sample

Note. T1 = Time 1. T2 = Time 2. T3 = Time 3. T4 = Time 4. T5 = Time 5. All correlations significant at p < .01

Table 3. Random intercepts variances and covariances

Note. Standard error in parentheses. RI = random intercept. All variances and covariances unstandardized and significant at p < .001.

Measurement invariance and model comparisons

The measurement model included five latent constructs (i.e., representing each wave) for peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and family cohesion – measured by each scale's respective items as indicators. The measurement model indicated good fit (χ2 [6,736] = 11,091.07, p < .001; CFI = .906, RMSEA = 0.028, SRMR = .051. Configural, metric, and scalar invariance was evident across the five waves for peer victimization and family cohesion. Configural and metric invariance, but only partial scalar invariance, was established for depressive symptoms (see Table 4). Configural, metric, and scalar invariance was evident across sex for family cohesion and depressive symptoms. Configural invariance, but only partial metric and scalar invariance, was established for peer victimization. After releasing the equality constraints on an item assessing physical bullying, partial metric and scalar invariance was evident for peer victimization across sex (see Table 5). Configural, metric, and scalar invariance was established across victim status (peer victim, bully victim) for family cohesion and depressive symptoms. Configural, metric, but only partial scalar invariance was found for peer victimization (see Table 6).

Table 4. Measurement invariance across time

Note. CBVS = California Bully Victimization Scale (Felix et al., Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011); CESD-10 = Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Short Form (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010); FACES III = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Portner and Lavee1985); CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation

a Item 8 (Time 5 only) released.

*** p < .001.

Table 5. Measurement invariance across sex

Note. CBVS = California Bully Victimization Scale (Felix et al., Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011); CESD-10 = Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Short Form (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010); FACES III = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Portner and Lavee1985); CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation

a Item 4 factor loadings released across all waves.

b Item 4 factor loadings and intercepts released across all waves.

*** p < .001.

Table 6. Measurement invariance across victimization group

Note. CBVS = California Bully Victimization Scale (Felix et al., Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011); CESD-10 = Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Short Form (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010); FACES III = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Portner and Lavee1985); CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation

*** p < .001.

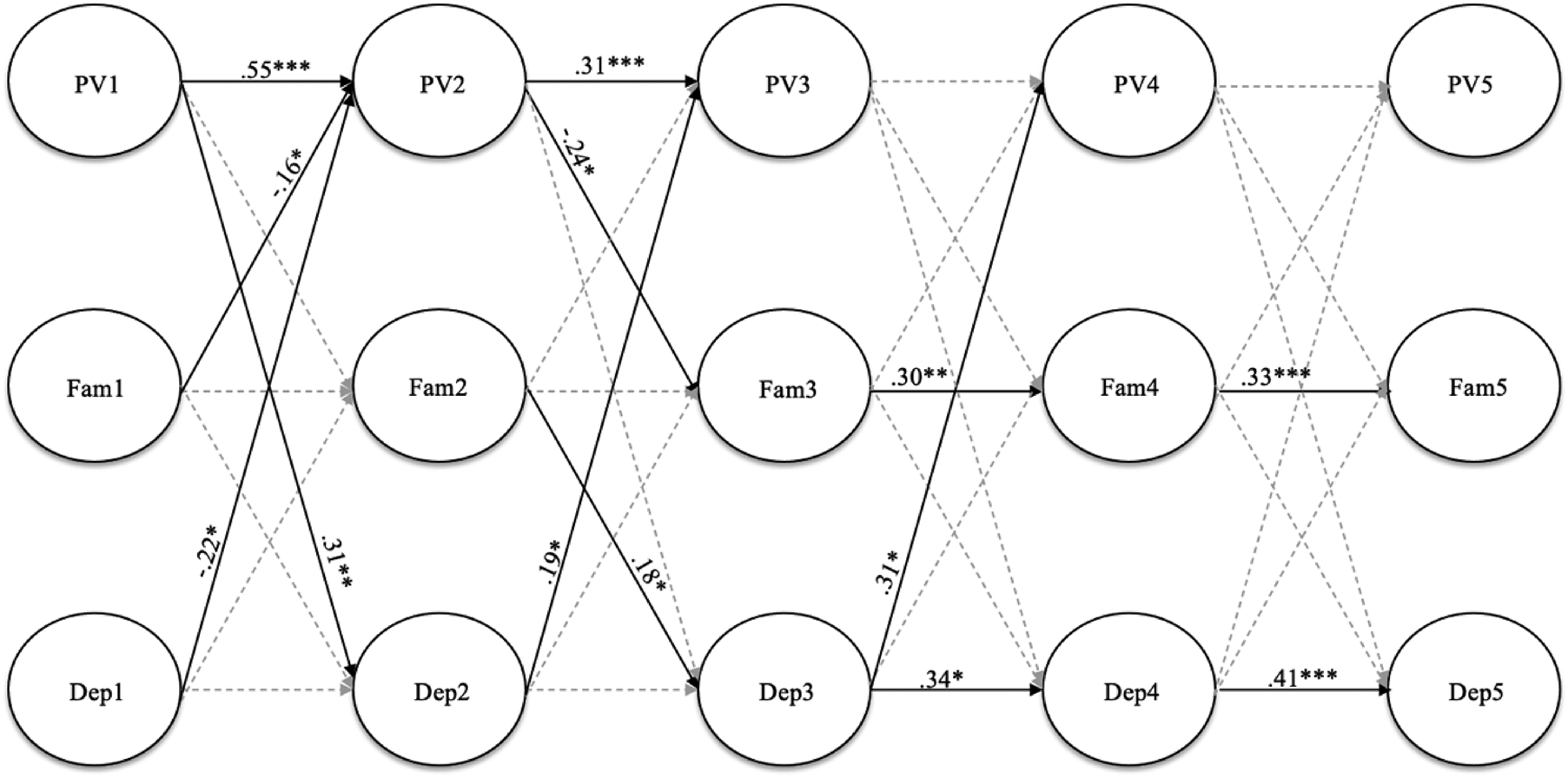

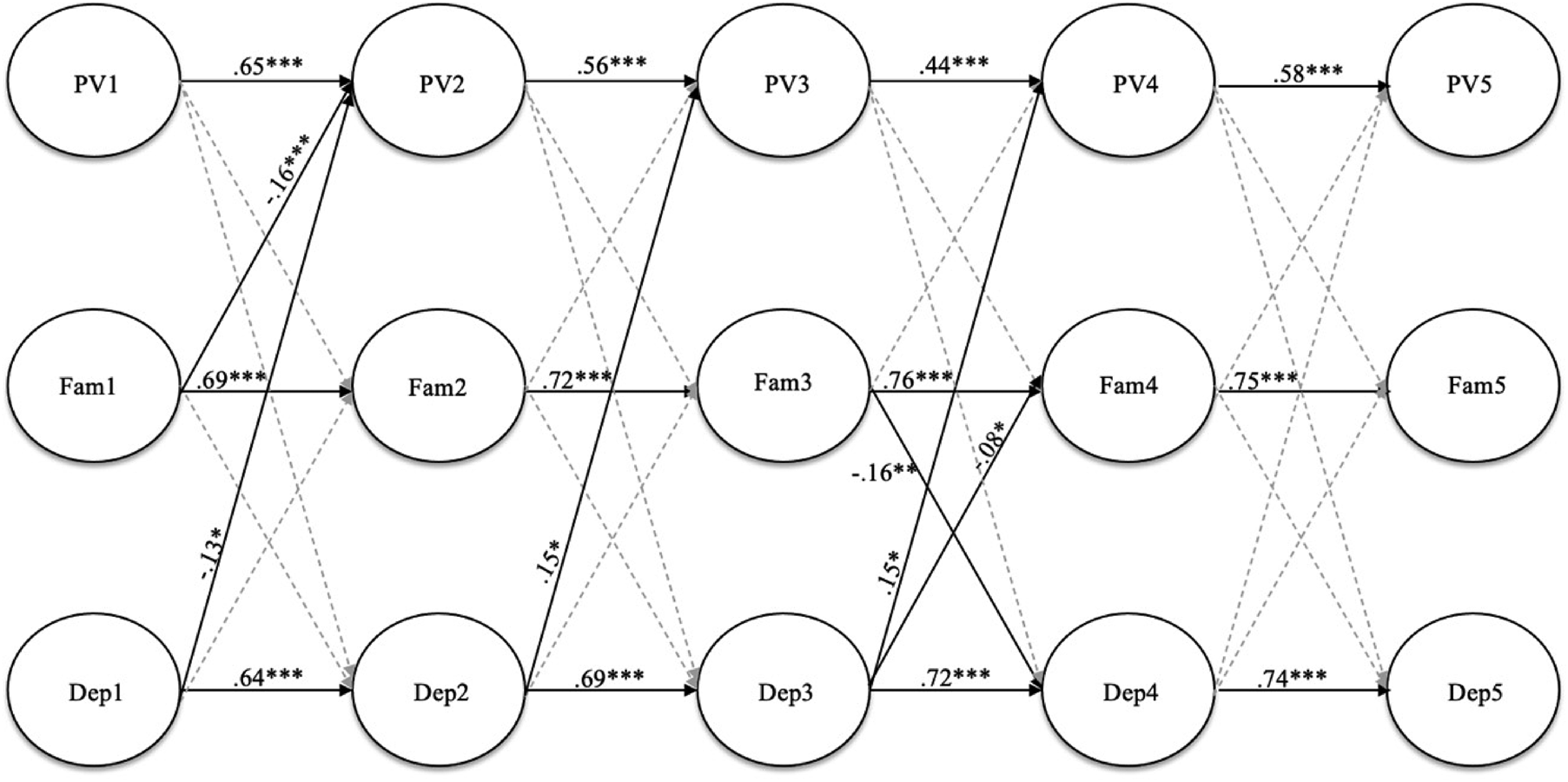

The RI-CLPM fit significantly better than the CLPM (ΔS-B χ2 [21] = 289.35, p < .001). Residual within-wave covariances, cross-lagged paths, and autoregressive paths were then constrained across time and compared with the freely estimated RI-CLPM; the freely estimated model fit the data significantly better (ΔS-B χ2 [39] = 130.68, p < .001). Similarly, the freely estimated RI-CLPM fit the data significantly better when residual within-wave covariances (ΔS-B χ2 [27] = 72.38, p < .001), cross-lagged paths (ΔS-B χ2 [21] = 101.61, p < .001), and auto-regressive paths (ΔS-B χ2 [30] = 98.79, p < .001) were released. Thus, the RI-CLPM with freely estimated auto-regressive paths, cross-lagged paths, and residual within-wave covariances was retained for analyses. Since prior longitudinal studies have relied on the CLPM to examine peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and family cohesion, results of the CLPM were also investigated. Results of the RI-CLPM and the CLPM can be found in Figures 2 and 3, respectively, for the total sample.

Figure 2. Random intercepts cross lagged panel model showing relations among peer victimization (PV), family cohesion (Fam), and depressive symptoms (Dep) for total sample across five waves. Note. Standardized estimates reported. Gray dashed paths indicate nonsignificant estimates. Indicators, between level intercepts, family composition covariate, and within-wave covariances not shown; estimates reported in paper. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Figure 3. Cross lagged panel model showing relations among peer victimization (PV), family cohesion (Fam), and depressive symptoms (Dep) for total sample across five waves. Note. Standardized estimates reported. Gray dashed paths indicate nonsignificant estimates. Indicators, family composition covariate, and within-wave covariances not shown. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Peer victimization and depressive symptoms

Residual within-wave covariances (i.e., state-like elements) were significant and positive for T1, T2, and T3 only (rs = .61, .39, .36, p < .001, respectively). Significant auto-regressive paths were observed for peer victimization from T1 to T2 (B = .51, SE = .09, p < .001) and from T2 to T3 (B = .28, SE = .09, p < .001). Significant auto-regressive paths were also observed for depressive symptoms from T3 to T4 (B = .34, SE = .11, p = .001) and from T4 to T5 (B = .42, SE = .09, p < .001). Thus, within-person deviations in levels of peer victimization at T2 and T3 are predicted by the individual's prior deviations from their own scores at T1 and T2, respectively. For depressive symptoms, within-person deviations predicted only later waves (i.e., T4 and T5); see Figure 2. In contrast, the traditional CLPM revealed significant auto-regressive paths across all waves (see Figure 3).

Overall, RI-CLPM results indicated a reciprocal relation between peer victimization and depressive symptoms (Figure 2). Cross-lagged effects were observed from T1 peer victimization to T2 depressive symptoms (B = .10, SE = .04, p = .005), indicating that when an adolescent's score on T1 peer victimization was higher than expected (based on their mean levels across all waves), they also reported higher than expected levels of depressive symptoms at T2. Cross-lagged effects were also observed from T2 and T3 depressive symptoms to T3 and T4 peer victimization (B = .46, SE = .19, p = .02, B = .40, SE = .19, p = .02, respectively), such that within-person deviations in depressive symptoms predicated within-person deviations in peer victimization across the two time points (see Figure 2). In the traditional CLPM, cross-lagged effects were observed such that depressive symptoms predicted peer victimization only (and not nice versa; Figure 3).

Family cohesion

Residual within-wave covariances indicated peer victimization was significantly negatively associated with family cohesion at T2 only (r = −.20, SE = .08, p = .02). Depressive symptoms were significantly negatively associated with family cohesion at T1 and T4 only (r = −.27, SE = .07, p < .001, r = −.12, SE = .06, p = .03, respectively). Positive auto-regressive paths for family cohesion were observed from T3 to T4 (B = .35, SE = .11, p = .001) and from T4 to T5 (B = .35, SE = .07, p < .001). A reciprocal relation was also found between peer victimization and family cohesion with negative cross-lagged effects observed from T1 family cohesion to T2 peer victimization (B = −.30, SE = .13, p = .03), and from T2 peer victimization to T3 family cohesion (B = −.12, SE = .05, p = .02). When adolescents reported lower than expected scores on T1 family cohesion, they also reported higher than expected levels of T2 peer victimization (and vice versa). Unexpectedly, a positive cross-lagged path was observed from T2 family cohesion to T3 depressive symptoms (B = .12, SE = .05, p = .03). Overall, cross-lagged effects between the RI-CLPM and CLPM were different in that a reciprocal relation between peer victimization and family cohesion was found in the RI-CLPM, but not the CLPM (Figure 3).

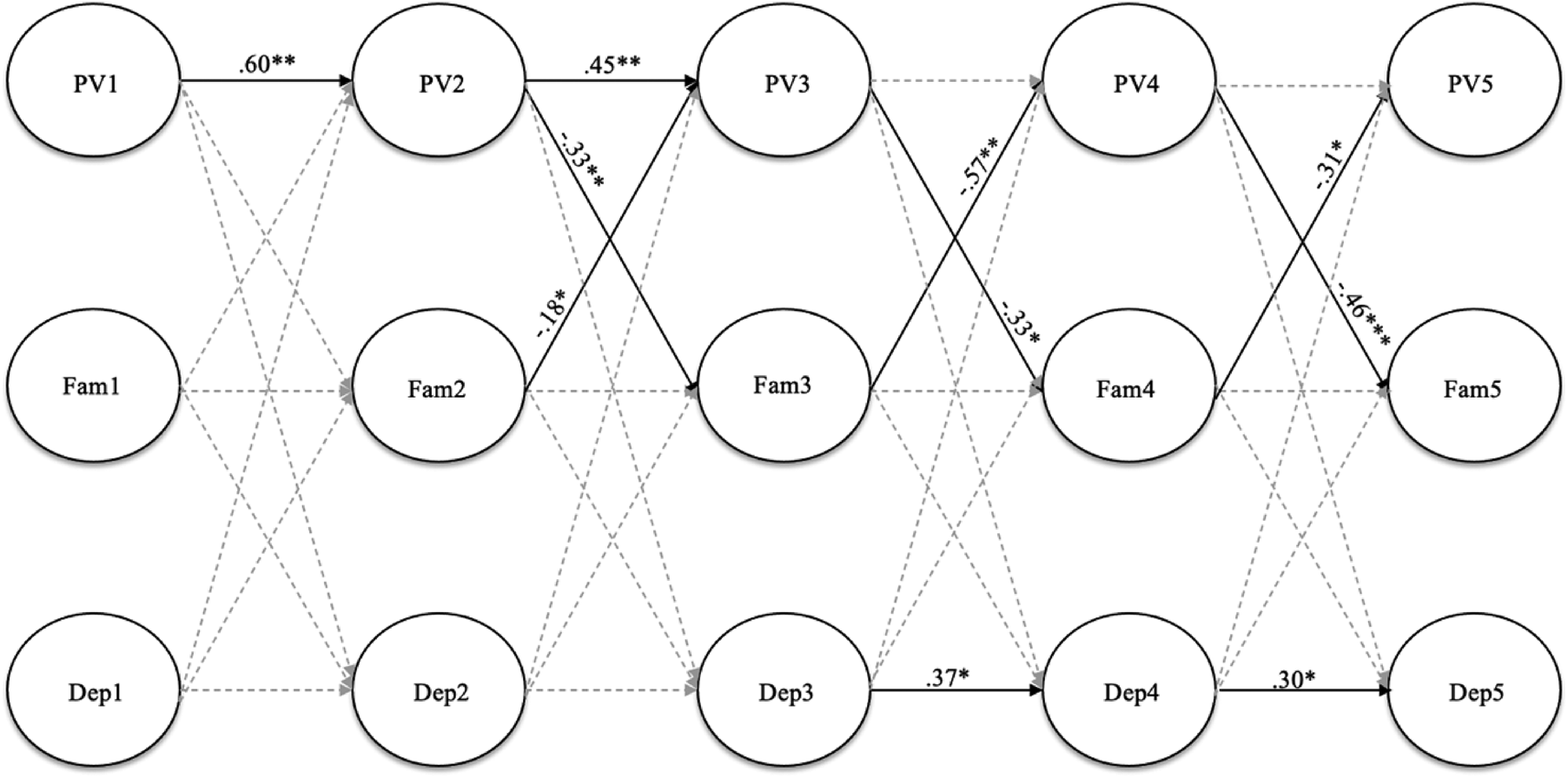

Sex differences

To examine sex differences in the RI-CLPM, a series of multiple group analyses were conducted across sex (i.e., male, female). Crossgroup equality constraints were imposed on the auto-regressive and cross-lagged paths, as well as residual within-wave covariances. The chi-square difference between the unconstrained and constrained model was significant, ΔS-B χ2 [51] = 93.52, p < .001, indicating the fit of the constrained model was significantly worse than that of the unconstrained model. Thus, the unconstrained model was retained. For males, at the between-person level (i.e., covariances among random intercepts), peer victimization was positively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = .47, SE = .10, p < .001) and depressive symptoms was negatively correlated with family cohesion (r = −.50, SE = .06, p < .001). At the within-person level, a reciprocal relation between peer victimization and family cohesion was found across T2, T3, T4, and T5 (see Figure 4). Neither peer victimization nor family cohesion predicted depressive symptoms for males. Significant auto-regressive paths were found for peer victimization (T1 to T2) and depressive symptoms (T3 to T5).

Figure 4. Random intercepts cross lagged panel model showing relations among peer victimization (PV), family cohesion (Fam), and depressive symptoms (Dep) for males across five waves. Note. Standardized estimates reported. Gray dashed paths indicated nonsignificant estimates. Indicators, between level intercepts, family composition covariates, and within-wave covariances not shown; estimates reported in paper. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

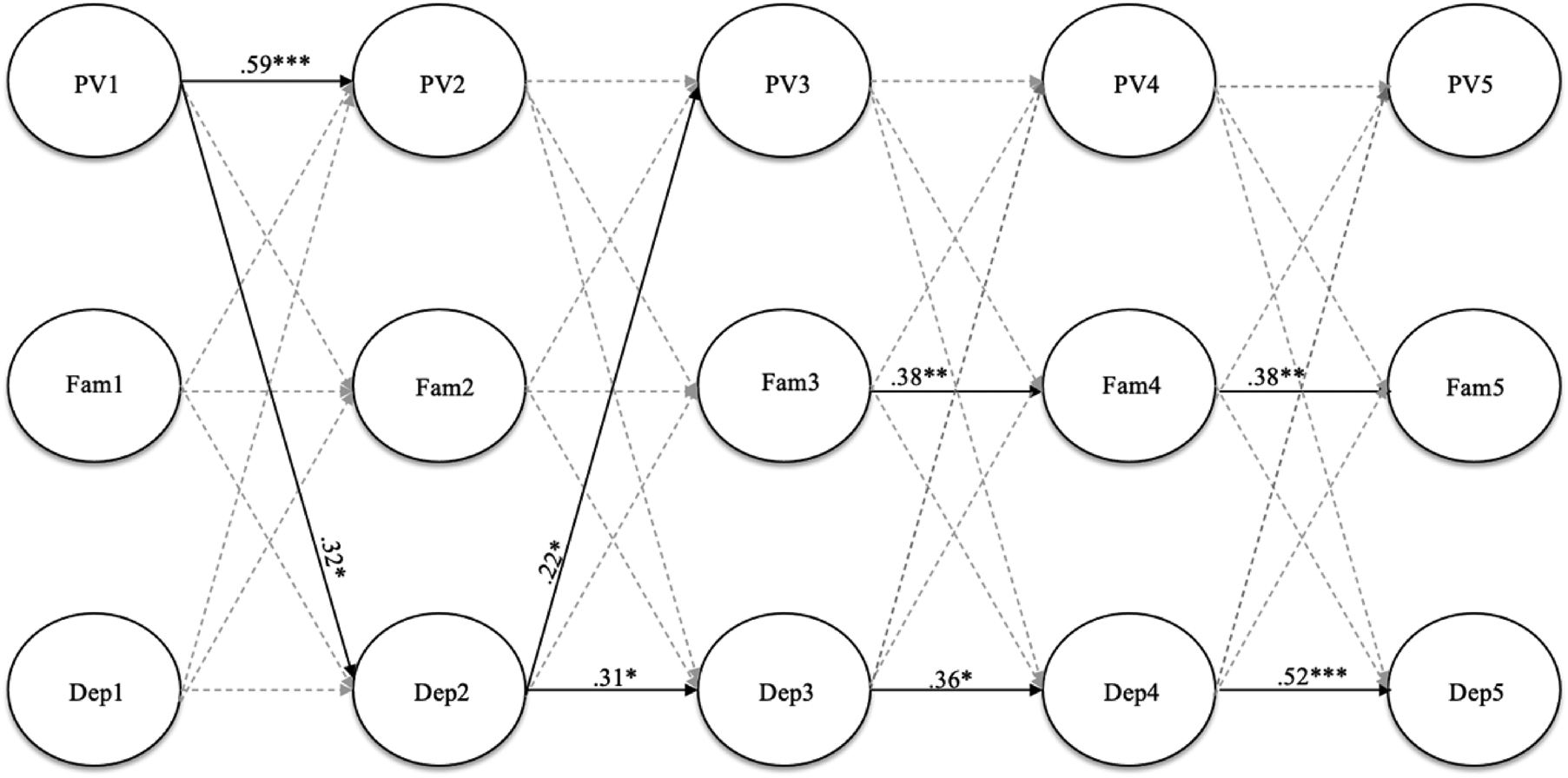

For females, at the between-person level, peer victimization was significantly correlated with both depressive symptoms (r = .43, SE = .07, p < .001) and family cohesion (r = −.33, SE = .07, p < .001), and family cohesion was significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (r = −.59, SE = .06, p < .001). At the within-person level, a reciprocal relation between peer victimization and depressive symptoms was found with positive cross-lagged paths from T1 peer victimization to T2 depressive symptoms (B = .11, SE = .05, p = .04) to T3 peer victimization (B = .57, SE = .26, p = .03). Significant auto-regressive paths were found for peer victimization (T1 to T2) and depressive symptoms (T2 to T5; see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Random intercepts cross lagged panel model showing relations among peer victimization (PV), family cohesion (Fam), and depressive symptoms (Dep) for females across five waves. Note. Standardized estimates reported. Gray dashed paths indicated nonsignificant estimates. Indicators, between level intercepts, family composition covariates, and within-wave covariances not shown; estimates reported in paper. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Victimization status

A similar procedure was employed to examine differences across bullying victims and peer victims. The chi-square difference between the unconstrained and constrained model was not significant, ΔS-B χ2 [51] = 42.24, p = .804, indicating the fit of the constrained model was not significantly worse than that of the unconstrained model. Thus, the constrained and more parsimonious model was retained. In other words, the longitudinal relations among peer victimization, family cohesion, and depressive symptoms were similar for adolescents experiencing peer victimization and bullying victimization.

Discussion

Although there has been a focus in the literature on examining the relations between peer victimization and depression longitudinally, a dearth of existing studies parcels out trait and state-like components of these constructs in order to examine these complex relations in a meaningful way. We sought to extend these prior studies and fill important methodological gaps in the literature by examining the longitudinal relations among peer victimization, family cohesion, and depressive symptoms with five waves of data from a large sample of adolescents through use of RI-CLPM. This methodological approach revealed new and unexpected findings, particularly at the within-person level and in relation to sex differences. Of note, the data fit the RI-CLPM better than the CLPM, indicating these constructs do in fact have trait-like components that should be accounted for in future scholarly work. Further, model fit was significantly better when we allowed for auto-regressive, cross-lagged, and residual within-wave covariances to be freely estimated across time. This is in contrast to prior longitudinal studies that found constraining paths and covariances across time did not result in worsened model fit (e.g., Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019); thus, developmental considerations are important in the interpretation of our findings.

Covariances among the random intercepts indicated that at the between-person level, peer victimization was positively associated with depressive symptoms for both males and females. In other words, males and females with high levels of peer victimization compared to other adolescents were more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms (and vice versa). This is consistent with prior studies and meta-analytic findings (Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010; van Geel et al., Reference van Geel, Goemans, Zwaanswijk, Gini and Vedder2018). Depressive symptoms were also negatively associated with family cohesion at the between-person level for both males and females. Much of the existing research shows an inverse relationship between family cohesion and depressive symptoms for adolescent females (e.g., Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Kremer, Douglas, Toumborou, Hameed, Patton and Williams2015). Finally, peer victimization was negatively associated with family cohesion for females, as expected, but not for males. Females with high levels of peer victimization (compared to other females) were also more likely to report low levels of family cohesion (compared to other females).

Within-person stability of depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and family cohesion

The RI-CLPM revealed critical differences by sex and developmental period in the within-person stability of constructs across time. State-like elements of depressive symptoms were predictive of later state depressive symptoms for both males and females, although this relation developed earlier for females. That is, an individual's level of depressive symptoms is related to future risk of depressive symptoms and this begins earlier for females. Participants were between the ages of 13.5 and 16 years at T2, and 14 and 16.5 years at T3. Past research has found that depression at age 15 is a consistent predictor of subsequent depression at age 17, particularly for girls (Kaltiala-Heino et al., Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010).

The predictive relation of state peer victimization predicting future peer victimization was found for both males and females across the first wave (i.e., T1 to T2); however, this predictive relation extended across the next wave (i.e., T2 to T3) for males only. Thus, peer victimization experiences leading to re-victimization may be more robust at earlier developmental periods when bullying activity is more common compared to later in adolescence (Ladd, Ettekal, & Kochenderfer-Ladd, Reference Ladd, Ettekal and Kochenderfer-Ladd2017; National Center for Education Statistics, 2018). The lack of long-term stability in peer victimization may also be due to environmental and maturational changes occurring over adolescence, including the transition from middle school to high school, changes in peer group, or increased social competence (Pouwels, Souren, Lansu, & Cillesson, Reference Pouwels, Souren, Lansu and Cillesson2016). It is unclear as to why the path remained stable over a longer period for males compared with females, although this pattern has been observed in other studies (Cillessen & Lansu, Reference Cillessen and Lansu2015). One possibility is that males react more aggressively when victimized, which may provoke continued victimization (Cillessen & Lansu, Reference Cillessen and Lansu2015).

Finally, state-like elements of family cohesion predicting future family cohesion was significant for females and only across the last three waves. Several studies have found perceived support from mothers to play an important role, particularly for females in late adolescence (Colarossi & Eccles, Reference Colarossi and Eccles2003; Meadows, Brown, & Elder, Reference Meadows, Brown and Elder2006), with females reporting higher quality relationships with mothers compared to males (Branje, Hale, Frijns, & Meeus, Reference Branje, Hale, Frijns and Meeus2010). Further, early adolescence is associated with drastic changes in development and this transitional period has been linked with changes in parent–child relationships (Lippold, Fosco, Hussong, & Ram, Reference Lippold, Fosco, Hussong and Ram2019). Females may have more stable, cohesive relationships with their parents, particularly their mothers, in mid-to-late adolescence.

Within-person relations among peer victimization and depressive symptoms

For the total sample, there was some support for a reciprocal relation (i.e., transactional model) between peer victimization and depressive symptoms across the first three waves; however, more robust support was found for a symptoms-driven model, with depressive symptoms predicting peer victimization across the first four waves. Of note, there are important differences by sex. Unexpectedly, there were no significant cross-lagged effects between peer victimization and depressive symptoms for males. This is in contrast to prior longitudinal research that shows reciprocal relations (transactional model) between peer victimization and depression for males (Lester, Dooley, Cross, & Shaw, Reference Lester, Dooley, Cross and Shaw2012). However, the prior research was conducted with a younger sample (11–14 years) and thus there may be developmental factors at play. For females, findings support a transactional model across the first three waves, with peer victimization predicting depressive symptoms, which in turn predicted peer victimization. Prior research has shown that girls experience more adverse psychological effects from victimization than boys, including depression (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Gruber & Fineran, Reference Gruber and Fineran2016), and that psychological symptoms place girls at risk for subsequent victimization. Consistent with this finding, Kaltiala-Heino et al. (Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Fröjd and Marttunen2010) found that depression and victimization at 15 predicted later victimization at age 17. They theorized that for girls, being bullied may be partially explained by negative attributions about social interactions and perhaps being less adept at social relationships when depressed.

Within-person relations among peer victimization, family cohesion, and depressive symptoms

Contrary to our predictions, family cohesion did not play a significant role in the relation between peer victimization and depressive symptoms for either males nor females. Prior research has focused on family social support – as opposed to family cohesion specifically – and although findings on family support have been mixed, van Harmelen et al. (Reference van Harmelen, Gibson, St Clair, Owens, Brodbeck, Dunn and Goodyer2016) found that family support in adolescence did not play a mediating or moderating role in the relation between bullying victimization and later depressive symptoms. The mediating role of social support may not operate consistently within individuals; for example, higher than expected levels of victimization could lead to higher than expected social support and then lower than expected distress (Jenkins, Fredrick, & Wenger, Reference Jenkins, Fredrick and Wenger2018), or it could lead to lower than expected social support (by victimization eroding this support) and potentially exacerbate depression (Pouwelse et al., Reference Pouwelse, Bolman, Lodewijkx and Spaa2011). Thus, it is possible that these variations, combined with parceling out between-person variance, resulted in no consistent pattern of significant effects. It is also possible that family cohesion may play a more critical role when it is more proximal to the victimization incident, whereas effects may have dissipated over the six-month assessment interval.

A reciprocal relation between peer victimization and family cohesion (from T2 to T5) was found for males. In other words, when a male experienced high levels of peer victimization, the same male subsequently experienced low levels of family cohesion (and vice versa). Similarly, when males experienced low levels of family cohesion, they subsequently experienced high levels of peer victimization (and vice versa). Males especially under-report their experiences of bullying because they do not want to be perceived as being weak or not being able to handle the situations on their own (Lai & Kao, Reference Lai and Kao2018). This may change their perceptions of their relationships with their parents and subsequently they may perceive less family cohesion and support. Alternatively, the negative reciprocal relationships between peer victimization and family cohesion may reflect pre-existing difficulties within the family relationships. For boys, exposure to negative parenting and inter-parental aggression has been linked to aggressive and externalizing behaviors, which in turn create social problems with peers and contribute to peer victimization (Espelage, Low, Rao, Hong, & Little, Reference Espelage, Low, Rao, Hong and Little2014).

Interestingly, for females, the RI-CLPM did not indicate a relation between peer victimization and family cohesion. That is, experiences of peer victimization were not predictive of changes in perceptions of family cohesion. Females in early adolescence are more likely than males to have more trust, communication and attachment in peer relations (Nickerson & Nagle, Reference Nickerson and Nagle2005). Given the value that females often place on peer relationships, it may be that peer victimization impacts peer relationships more so than family relationships for females. Our results also showed that there was more within-person stability in family cohesion across the later waves for females than males. These within-person results differ from the between-person level findings, which found that peer victimization was negatively associated with family cohesion for females.

Bullying victimization and peer victimization

A novel contribution of the current study was the examination of the influence of both peer victimization and traditionally defined bullying victimization on depressive symptoms. The study findings hold for both adolescents that experience peer victimization, as well as adolescents that experience bullying victimization. The use of the CBVS, which assesses the three components of bullying victimization (unwanted aggression, repetition, and power imbalance), allowed for an examination of possible different patterns of findings for bullying as opposed to more general peer victimization, which past studies have found may differ with regard to prevalence (e.g., Bear et al., Reference Bear, Mantz, Glutting, Yang and Boyer2015; Ybarra et al., Reference Ybarra, Boyd, Korchmaros and Oppenheim2012). Similar to Cook et al. (Reference Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim and Sadek2010) meta-analytic review where the measurement of bullying and peer victimization did not moderate findings about predictors of peer victimization, this study indicates no differences between peer victims and bullying victims in the relations among victimization, family support, and depression. This suggests that peer victimization, even if it does not meet criteria for bullying victimization (e.g., a single distressing incident that is not repeated, aggression that occurs among peers with relatively equal power) may still have a similar pattern of relations between victimization, later depression, and role of family cohesion. Therefore, attending to the youth's experience, impact, and support may be more important than narrowly focusing on the extent to which the victimization was from bullying specifically.

Implications for practice

The findings of the current study provide important implications for mental health practitioners and physicians working with adolescents, as well as families. First, peer victimization may not be as strongly associated with depressive symptoms for males as previously thought, particularly later in adolescence. Thus, when working with or supporting adolescent males experiencing peer victimization, other related factors should be considered, including substance abuse, or externalizing problems (Carbone-Lopez, Esbensen, & Brick, Reference Carbone-Lopez, Esbensen and Brick2010; Sullivan, Farrell, & Kliewer, Reference Sullivan, Farrell and Kliewer2006). In contrast, females experiencing peer victimization may subsequently experience depressive symptoms, which in turn could exacerbate experiences of victimization. A focus on prevention of depressive symptoms for females at an early age may be helpful not only for preventing future mental health difficulties, but also for promoting positive peer relationships concurrently and in the future. Families should also consider the ways that experiencing peer victimization may impact adolescents’ (particularly males’) perceptions of family cohesion and support. It is often the case that youth (especially males) do not report their experiences of victimization to trusted adults, including parents (deLara, Reference deLara2012), because they are afraid adults will make the situation worse. Therefore, practitioners working with parents should be aware of this and encourage families, especially for males, to communicate openly about peer relations and coping strategies from a young age.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the strengths of this study, including the large sample, excellent retention across five waves of data collection, and rigorous methodological and statistical approach that allowed for parceling out between-individual and within-individual effects, there are some limitations. First, although the racial and ethnic constitution of the sample was representative of the county from which it was drawn, it was largely White, which limits generalizability of the results to more diverse racial and ethnic groups. In addition, the majority of participants came from two-family homes with a relatively high median income, thus results may not generalize to youth from single-parent or low-income families. With regard to methodology, peer victims and bullying victims were classified based on their baseline scores, which may not have accounted for the differing experiences of victimization across the waves of data collection. Further, participants were classified as “bully victims” based on dichotomous categorization and future research should examine peer victimization and bully victimization as a spectrum of aggressive behavior as opposed to focusing on classifying bullying behavior. Although the measures used were psychometrically sound, it should be noted that only partial metric invariance was found for peer victimization across sex. Model modifications were also required to obtain adequate model fit (i.e., deleting two items from CESD-10, allowing CBVS items to covary). However, all modifications made to the factor structures made theoretical sense (e.g., all covarying items on the CBVS assessed aspects of physical bullying) and the items deleted from the CESD-10 have been found to have lower loadings in prior research (e.g., Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Prencipe, Hjelm, Peterman, Handa and Palermo2018). In addition, we included family cohesion, but there are other family factors (e.g., marital or sibling conflict) that may be important but were not assessed. Time-varying confounding variables regarding past exposure (e.g., experiences of peer victimization, perceptions of family cohesion, and levels of depressive symptoms prior to the study) may also have impacted findings (Mansournia, Etminan, Danaei, & Collins, Reference Mansournia, Etminan, Danaei and Collins2017). For example, prior levels of family cohesion may impact experiences of peer victimization during the course of the study. Further, other time-varying confounding variables, including substance use and abuse (Espelage et al., Reference Espelage, Low, Rao, Hong and Little2014; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Derrick, Testa, Wang, Nickerson, Espelage and Miller2019), peer relationships (especially for females; Nickerson & Nagle, Reference Nickerson and Nagle2005), and relationships with teachers or staff at school (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Fredrick and Wenger2018) may also impact study findings and should be incorporated into future longitudinal RI-CLPM studies. Additional victimization that occurred within the six-month intervals may also not have been captured within the models of the current study.

Nonetheless, findings from this study contribute to the literature and also provide a foundation for future research. Results of the CLPM and RI-CLPM underscore the importance of future work accounting for within-person and between-person effects when examining peer victimization, depression, and other constructs that have trait-like elements to better disentangle these effects. Given that depression was not predicted for boys by peer victimization in the RI-CLPM, it may be important for future research to examine other outcomes, such as aggression and other externalizing behaviors. Although the current study differentiated between peer victimization and bullying victimization, it did not examine the different forms (e.g., physical, verbal, relational, and cyber victimization), which could be important in examining the potential protective role of family cohesion for victimized youth (Yeung-Thompson & Leadbeater, Reference Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater2013). In addition, different forms of victimization are associated with different outcomes for males and females (Carbone-Lopez et al., Reference Carbone-Lopez, Esbensen and Brick2010; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Farrell and Kliewer2006). Other sources of social support (e.g., friends) also should be included to test how these different sources of social support may complement or compensate each other in terms of outcomes for adolescents who experience peer victimization. Future research should also examine family cohesion as a moderator in order to test the stress buffering model of social support for peer victimization. Finally, this study used a six-month interval in between waves; however, the effects of victimization on internalizing symptoms may occur more proximal to the victimization experience. Efforts should be made in future studies to determine the optimal time lag needed to observe the effects of interest (Dormann & Griffin, Reference Dormann and Griffin2015). Alternatively, research designs that incorporate longitudinal surveys along with multiple short-duration bursts of daily-level assessments may be particularly useful for examining proximal and long-term effects of peer victimization on depressive symptoms (Sliwinski, Reference Sliwinski2008).

Conclusions

The current study filled important methodological gaps in the literature by examining the relations among peer victimization, family cohesion, and depressive symptoms across five waves through a RI-CLPM. Overall, findings supported both a symptoms-driven and transactional model regarding peer victimization and depressive symptoms for the total sample. However, results revealed important differences from prior studies that have relied on traditional CLPM, particularly related developmental and sex differences. Future research should continue to account for within-person and between-person differences when examining peer victimization and associated risk and protective factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Haas, Cynthia Warthling, Ashley Rupp, and Carrie Pengelly for their assistance with data collection. We would also like to thank Weijun Wang and Denise Feda for their assistance with data management.

Financial Statement

This research was funded by R01 AA021169 awarded to Jennifer A. Livingston by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Conflicts of Interest

None.