During early adolescence, experiences of peer inclusion and exclusion become of central importance in adolescent lives. Peer rejection might be particularly detrimental for developing youth whose needs of social belonging are likely to thwarted. Indeed, peer rejection in early adolescence prospectively predicts increases in physical aggression and antisocial behavior (for reviews, see Dodge, Lansford, Burks, et al., Reference Dodge, Lansford, Burks, Bates, Pettit, Fontaine and Price2003; Prinstein, Rancourt, Adelman, et al., Reference Prinstein, Rancourt, Adelman, Ahlich, Smith, Guerry, Bukowski, Laursen and Rubin2018). Several mechanisms have been posited to explain how rejected youth are at a greater risk for development of antisocial behavior (AB), including socio-information processing deficits and hostile attribution bias (Dodge, Greenberg, Malone, et al., Reference Dodge, Greenberg and Malone2008; Lansford, Malone, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, Reference Lansford, Malone, Dodge, Pettit and Bates2010) and lack of opportunities to develop vital social competencies (Dodge et al., Reference Dodge, Lansford, Burks, Bates, Pettit, Fontaine and Price2003). Because peers play crucial role in both social rejection and development of antisocial behavior, the focus on peer ecology as explanatory mechanism has also been advocated.

Specifically, Dishion, Patterson, & Griesler (Reference Dishion, Patterson, Griesler and Huesmann1994) introduced the concept of confluence, describing how adolescents’ antisocial behavior evolves in the context of their friendships and shaped by (a) experiences of peer rejection, (b) initial selection of friends, and (c) peer influence among friends through peer reinforcement processes (i.e., deviancy training). Two propositions of the confluence model have been supported: antisocial youth are likely to befriend one another and are influenced by their peers (Dishion & Tipsord, Reference Dishion and Tipsord2011; Gallupe, McLevey, & Brown, Reference Gallupe, McLevey and Brown2018; Sijtsema & Lindenberg, Reference Sijtsema and Lindenberg2018); however, the role of peer rejection in these processes has received limited empirical attention (Light & Dishion, Reference Light, Dishion, Rodkin and Hanish2007).

Social marginalization in the form of peer rejection is thought to augment the value of any peer interaction, even a low-quality one, which leads to rejected youth selecting each other as friends and resulting in clustering of rejected peers (Dishion, Piehler, & Myers, Reference Dishion, Piehler, Myers, Prinstein and Dodge2008). From an evolutionary perspective, social rejection can be seen as a survival threat, leading to self-organization into peer groups that promote an array of problem behaviors, including AB, because such behaviors are reinforced by peers and serve a function of securing and maintaining group membership (Dishion, Ha, & Véronneau, Reference Dishion, Ha and Véronneau2012). Taken together, these lines of research underscore a complex pattern of associations among peer networks, rejection, and AB.

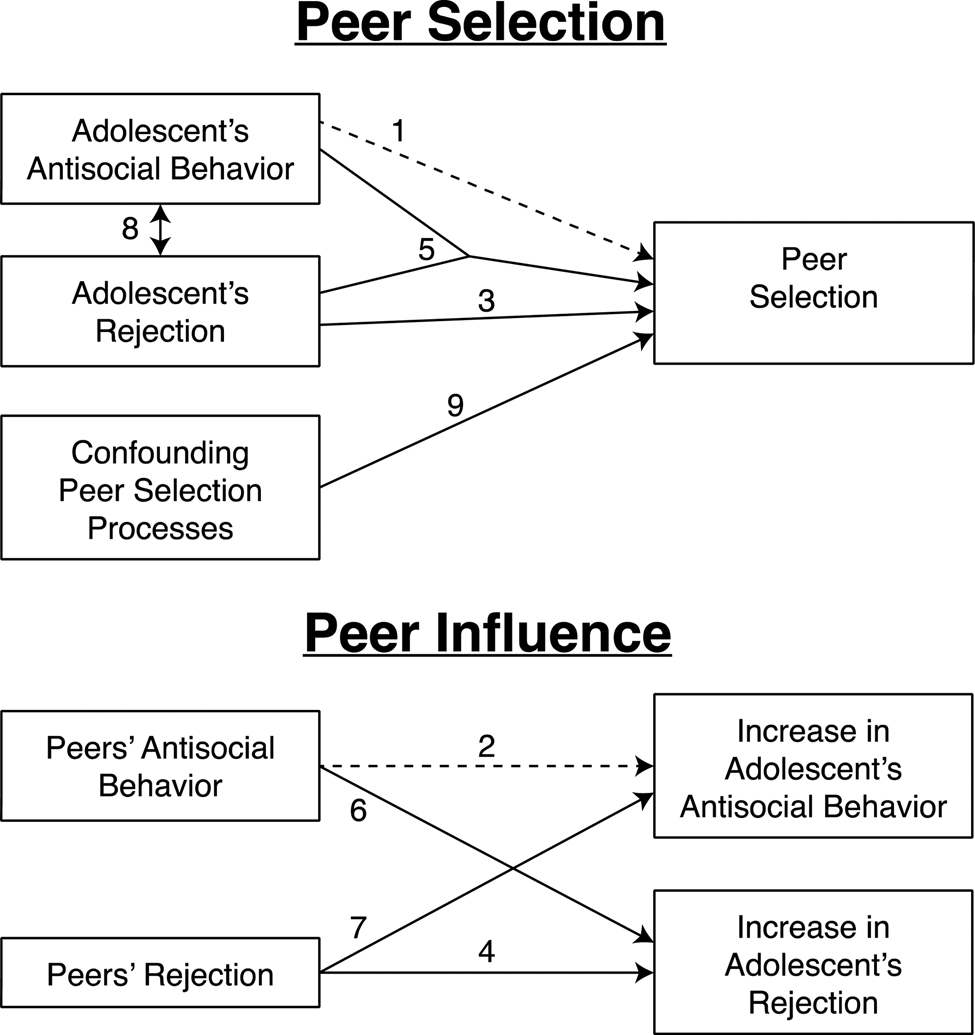

Drawing on recent advances in conceptualizing and testing the role of peer network dynamics for behavior development (Veenstra, Dijkstra, Steglich, & Van Zalk, Reference Veenstra, Dijkstra, Steglich and Van Zalk2013; Veenstra, Dijkstra, & Kreager, Reference Veenstra, Dijkstra, Kreager, Bukowski, Laursen and Rubin2018), we updated and tested the confluence model by examining co-evolving developmental trajectories of peer rejection and AB in the context of peer network dynamics. The peer network dynamics perspective and its corresponding longitudinal social network analysis (SNA) methods (Snijders, van de Bundt, & Steglich, Reference Snijders, van de Bunt and Steglich2010) underscores that to understand how peers shape problem behavior requires not only looking at them as sources of influence (peer influence), but also in accounting for how adolescents come to have particular friends (peer selection). Applied to the confluence model, the peer network dynamics perspective suggests that several new pathways need to be examined to describe the role that peer rejection may play for developmental trajectories of AB. Specifically, in addition to the two established pathways of peer selection and influence on AB (Figure 1, dashed lines), we also need to examine peer selection and influence on rejection, interactive associations between AB and rejection as contributing to peer selection, and indirect peer influences between rejection and AB and vice versa. Given that we know substantially less about how peer rejection shapes peer network dynamics related to progression of AB, the updated confluence model articulated in this study aims to fill these theoretical and empirical gaps.

Figure 1. Updated Confluence Model

Confluence model: Established pathways

Peer selection on antisocial behavior

Earlier generations of developmental research using static snapshots of deviant peer groups (i.e., cross-sectional designs without controlling for network interdependence) revealed that antisocial youth were more likely to have antisocial friends (e.g., Dishion, Andrews, & Crosby, Reference Dishion, Andrews and Crosby1995; Vitaro, Tremblay, Kerr, Pagani, & Bukowski, Reference Vitaro, Tremblay, Kerr, Pagani and Bukowski1997). Moreover, a history of AB, academic skill deficits, and poor monitoring practices predicted increased deviant peer clustering (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, Reference Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller and Skinner1991). This research has relied on individual-level analyses and was unable to disentangle distinct contributions of deviant peer clustering from peer contagion that jointly operate in peer networks.

With the advent of longitudinal SNA modeling approaches (Snijders et al., Reference Snijders, van de Bunt and Steglich2010), developmental and criminology researchers have focused on distinguishing between peer selection and influence processes at the level of a peer network. Several studies relying on longitudinal SNA analysis have shown that peer selection dynamics are relevant to AB (Figure 1, path 1). Studies of US high schoolers documented that adolescents befriended those with similar levels of delinquency (Jose, Hipp, Butts, Wang, & Lakon, Reference Jose, Hipp, Butts, Wang and Lakon2015) and violent offending (Turanovic & Young, Reference Turanovic and Young2016). Several studies with Western European samples also provided support for peer selection on AB (Burk, Steglich, & Snijders, Reference Burk, Steglich and Snijders2007; Franken, Prinstein, Dijkstra, et al., Reference Franken, Prinstein, Dijkstra, Steglich, Harakeh and Vollebergh2016; Knecht, Snijders, Baerveldt, Steglich, & Raub, Reference Knecht, Snijders, Baerveldt, Steglich and Raub2010; Svensson, Burk, Stattin, & Kerr, Reference Svensson, Burk, Stattin and Kerr2012). A recent meta-analysis of 28 effect sizes from longitudinal SNA studies of peer selection on offending behavior (i.e., shoplifting, fighting, aggression, property crime) documented a significant positive effect size, revealing that adolescents had 5% greater odds of selecting a friend with a same level of offending behavior compared with befriending someone with a different level of offending behavior (i.e., Cohen d of 0.03, or a small effect size; Gallupe et al., in press). Taken together, these studies provide support for peer selection for AB.

Peer influence on antisocial behavior

Multiple studies have shown significant peer influence effects on AB in longitudinal SNA studies (Figure 1, path 2). In a study of US high schoolers, adolescents changed their levels of delinquency to become similar to their friends (Jose et al., Reference Jose, Hipp, Butts, Wang and Lakon2015). Several studies with Western European samples also provided support for peer influence effects on AB. Specifically, one study documented that peer influence on delinquency operated friendship networks of Swedish youth (12–16 years of age; Svensson et al., Reference Svensson, Burk, Stattin and Kerr2012), whereas another investigation documented that peer influence on delinquency existed only among mutual friends (Burk et al., Reference Burk, Steglich and Snijders2007). The same meta-analysis of 24 effect sizes of peer influence on offending behavior documented a significant positive effect size (Gallupe et al., in press). Specifically, the odds of an adolescent changing their levels of offending to become one unit closer to their friends are 21% greater than not changing them (i.e., Cohen d of 0.68, or a medium to large effect size). This research provides a robust evidence for peer influence on AB in adolescent networks.

Confluence model: New pathways

Peer selection as a function of rejection

Developmental scientists have long been interested in understanding antecedents and consequences of peer rejection. Historically, this work has focused on identifying how antisocial and aggressive behavior, academic achievement, and social skill deficits precedes or forecasts being rejected for a peer group (Coie & Kupersmidt, Reference Coie and Kupersmidt1983; Dishion, Reference Dishion and Leone1990; Dodge, Reference Dodge1983). An important insight emerging from this work was that rejected youth were more likely to self-organize in peer groups with other rejected and antisocial adolescents (Bagwell, Newcomb, & Bukowski, Reference Bagwell, Newcomb and Bukowski1998; Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman, Gest, & Gariépy, Reference Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman, Ferguson and Gariépy1989; Dishion, Reference Dishion1987; Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller and Skinner1991; Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maumary-Gremaud, et al., Reference Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maumary-Gremaud and Bierman2002).

Moving beyond the individual level of analysis, recent research advocates that rejection needs to be investigated from a relational perspective (Bierman, Reference Bierman2004; Erath, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, Reference Erath, Pettit, Dodge and Bates2009; Mikami, Lerner, & Lun, Reference Mikami, Lerner and Lun2010). Accordingly, more attention has turned to understanding how rejection contributes to peer network dynamics (Fujimoto, Snijders, & Valente, Reference Fujimoto, Snijders and Valente2017; Huitsing, Snijders, Van Duijn, & Veenstra, Reference Huitsing, Snijders, Van Duijn and Veenstra2014; Pál, Stadtfeld, Grow, & Takács; Reference Pál, Stadtfeld, Grow and Takács2016; Rambaran, Dijkstra, Munniksma, & Cillessen, Reference Rambaran, Dijkstra, Munniksma and Cillessen2015). Considering the effect of rejection status on peer selection processes, evidence points that adolescents from the US middle schools befriended those who had experienced similar levels of rejection in five of eight school contexts (Light & Dishion, Reference Light, Dishion, Rodkin and Hanish2007). Additional support for the need to examine how peer status contributes to peer selection comes from the evidence that network dynamics are driven by peer preference, which is a measure of peer status that lies on the opposite side of status continuum from peer rejection and represents the degree to which one is admired and liked by their peers (Marks, Cillessen, & Crick, Reference Marks, Cillessen and Crick2012). Given that rejected youth are not entirely socially isolated and they have a smaller number of friends (Gest, Graham-Bermann, & Hartup, Reference Gest, Graham-Bermann and Hartup2001), research needs to elucidate how rejected youth are selecting their friends (Figure 1, path 3).

Peer influence on rejection

Research at the individual level of analysis has shown that friends’ levels of rejection are positively correlated with those of the focal youth (Dishion, Reference Dishion1987), suggesting a potential for peer influence processes (Figure 1, path 4). To the best of our knowledge, no research using longitudinal SNA has examined peer influence on rejection as occurring among friends.

Interactive associations between antisocial behavior and rejection that contribute to peer selection

Default selection by rejected youth

One of the key, yet overlooked, propositions of the confluence model is that youth who confront rejection from their peers are more likely to befriend antisocial youth, who themselves are also likely to deal with peer marginalization (Dodge, Coie, Pettit, & Price, Reference Dodge, Coie, Pettit and Price1990). In other words, when encountering a limited pool of potential friends, rejected youth befriend others who were not their first choices as friends but who are available, resulting in a default selection pattern (Figure 1, path 5). Such a pool of potential friends is likely to exhibit academic and social skill deficits, antisocial behavior, and increased likelihood of subsequent gang involvement (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller and Skinner1991; Dishion, Nelson & Yasui, Reference Dishion, Nelson and Yasui2005). Recent research using longitudinal SNA approaches has provided support for the default selection pattern by showing that highly aggressive boys tended to form friendships with other aggressive peers despite their preference to select prosocial peers (Sijtsema, Lindenberg, & Veenstra, Reference Sijtsema, Lindenberg and Veenstra2010). Default selection has also been documented for friendship formation processes among victimized children and youth (Sentse, Dijkstra, Salmivalli, & Cillessen, Reference Sentse, Dijkstra, Salmivalli and Cillessen2013; Sijtsema, Rambaran, & Ojanen, Reference Sijtsema, Rambaran and Ojanen2013). It is plausible therefore that rejected youth are more likely to select friends who are also rejected and delinquent.

“Shopping” by antisocial youth

Adolescents are not passive recipients of their social environment; they actively create their own social niche fitting their temperament and learning history (Scarr & McCartney, Reference Scarr and McCartney1983). Evidence shows that, especially in early adolescence with the start of puberty, high-risk youth actively pull away from normative prosocial school contexts and parental supervision and seek out engagement in unsupervised activities, a process called wandering (Stoolmiller, Reference Stoolmiller1990). Patterson referred to the active process of finding unsupervised settings in which to connect with other high-risk youth as the “shopping” hypothesis (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, Reference Patterson, Reid and Dishion1992). It is a plausible but untested assumption that antisocial youth might be actively befriending rejected youth (Figure 1, path 5).

Indirect peer influence

A recent conceptualization of the pathways linking peer relations to developmental psychopathology suggests that, in addition to having direct peer influence on one another (i.e., modeling), youth may be influenced by peers via indirect pathways (Brechwald & Prinstein, Reference Brechwald and Prinstein2011; Prinstein & Gileta, Reference Prinstein, Giletta and Cicchetti2016). It has been theorized that indirect peer influence (i.e., focal youth changes behavior X as a function of their friends’ behavior Y) may operate for similarly themed behaviors or through socialization of underling processes (Prinstein & Gileta, Reference Prinstein, Giletta and Cicchetti2016). Because peer rejection status and antisocial behavior are reciprocally associated at the level of an individual (Dodge, Reference Dodge1983) and may stem from hostile attributional biases (Dodge et al., Reference Dodge, Greenberg and Malone2008), a possibility exists that an indirect peer influence between AB and rejection status and vice versa may operate in peer networks over time. As an exploratory goal, we examine such indirect peer influences between peers’ AB and the focal adolescent's rejection status (Figure 1, path 6) and between peers’ rejection status and the focal adolescent's AB (Figure 1, path 7).

Reciprocal associations between rejection and antisocial behavior

Previous research has shown that their peers are likely to reject youth who exhibit aggressive and delinquent behavioral tendencies (Coie & Kupersmidt, Reference Coie and Kupersmidt1983; Dishion, Reference Dishion and Leone1990; Dodge, Reference Dodge1983). The picture becomes more complex in early adolescence, however, because antisocial youth can be controversial; that is, their peers like them and reject them at the same time (Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, & Van Acker, Reference Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl and Van Acker2000). Considering the opposite pattern of association, peer rejection, accompanied by academic skill deficits, leads to AB and deviant peer clustering (e.g., Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller and Skinner1991; Dodge et al., Reference Dodge, Coie, Pettit and Price1990). In sum, considered at the level of an individual, peer rejection and antisocial behavior appear to be reciprocally associated (Figure 1, path 8; Sentse, Kretschmer, & Salmivali, Reference Sentse, Kretschmer and Salmivalli2015; Tseng, Banny, Kawabata, Crick, & Gau, Reference Tseng, Banny, Kawabata, Crick and Gau2013).

Current study

The goal of this study was to update and test the confluence model using conceptual and analytical insights from the peer network dynamics perspective. The confluence model posited that dynamic associations among peer rejection, deviant peer clustering, and AB contribute to emergence of AB during adolescence, whereas the peer network dynamics perspective clarified reciprocal processes through which peer rejection and antisocial behavior jointly shape peer selection and influence processes. To do so, we tested a comprehensive host of the established and new pathways linking peer rejection and AB in changing peer networks using a longitudinal SNA approach (i.e., stochastic actor-based modeling, SABM; Snijders et al., Reference Snijders, van de Bunt and Steglich2010). Figure 1 depicts these pathways, which include the established pathways: (1) peer selection on AB and (2) peer influence on AB; and the new confluence pathways: (3) peer selection on rejection status, (4) direct peer influence on rejection, (5) interactive dynamics between peer rejection and AB as contributing to peer network selection (default selection and shopping), (6) indirect peer influence of AB on rejection, (7) indirect peer influence of rejection on AB, while controlling for (8) reciprocal associations between rejection and AB at the level of an individual as well as (9) peer network structural effects.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 997 adolescents recruited in sixth grade from three ethnically diverse metropolitan middle schools in the northwestern United States. These schools were in a neighborhood with high rates of crime. We invited parents of all Grade 6 students to participate; 90% provided consent. The sample included 526 males (52.8%) and 471 females (47.2%) and consisted of 423 European Americans (42.4%), 291 African Americans (29.2%), 68 Latino/a Americans (6.8%), 52 Asian Americans (5.2%), and 164 adolescents of other races, including biracial (16.4%). The median annual family income was between $30,000 and $40,000, with incomes ranging from $5,000 to more than $90,000 (in US dollars).

Procedures and intervention protocol

Data collection took place in two cohorts: cohort 1 was in 1997–1998 and cohort 2 in 1999–2000; 85% of the recruited students participated in three waves of data collection during middle school: spring of Grade 6 (Wave 1), spring of Grade 7 (Wave 2), and spring of Grade 8 (Wave 3). The schools and researchers integrated the multilevel family intervention into the public school system at three levels (for a complete description, see Dishion & Kavanagh, Reference Dishion and Kavanagh2003). The intervention randomization took place at the individual level at the end of Grade 6. Participating schools agreed to assign the Grade 7 homeroom class in response to the research team's randomization. The universal level involved a 6-week curriculum called SHAPE, which was delivered in the homeroom class (fall of Grade 7, before the Wave 2 assessment) and designed to engage both parents and students in a variety of exercises to promote school success, healthy adolescent choices, and positive peer group functioning and to diminish problem behaviors and violence. Students from the control group received the middle school curriculum as usual. The second and third levels of the intervention are beyond the focus of this study because they took place after the measurement period used in this study: at the end of the Grade 7, during the summer, and at the beginning of Grade 8. We therefore control simply for the intention-to-treat effects of participating in the intervention study, knowing that for these youth, the Grade 7 SHAPe curriculum potentially had the greatest effect on peer selection and influence processes.

Measures

Antisocial behavior and rejection assessments used peer reports. To assess antisocial behavior, we used unlimited peer nominations elicited by the following question: “Which children start fights, pick on other kids, and tease them?” A composite measure of antisocial behavior was calculated by adding the number of incoming peer nominations, standardizing within grade, and computing a standardized z-score across schools. To assess peer rejection, students responded to the question, “Which children do you like least?” Students could nominate an unlimited number of their classmates of either gender. Similar procedures helped to compute peer rejection composites as described previously. Finally, because SABM requires discrete ordinal behavioral outcome variables, we transformed the z-scored AB and rejection measures into an ordinal variable with three levels using these increments of the continuous z-score: z < 0, 0 ≤ z < 1, and z ≥ 1 (e.g., Delay, Ha, Van Ryzin, Winter, & Dishion, Reference DeLay, Ha, Van Ryzin, Winter and Dishion2016).

Peer affiliation assessment consisted of asking students, “Which children do you hang around with?” Students could nominate as many others from their grade as they wanted; there were no gender restrictions. We used a directed measure of peer affiliation such that a peer affiliation relationship existed if student A nominated student B that they hang around together (1 = affiliation, 0 = no affiliation).

We included several sociodemographic and contextual variables in the analyses. Adolescents reported on their gender (1 = female, 0 = male) and ethnic-racial background (1 = European American, 2 = African American, 3 = Native American, 4 = Hispanic or Latino/a, 5 = Asian American, and 6 = other). Finally, to control for contributions of intervention curriculum to peer selection and influence processes, we included a dummy-coded variable for students who participated in the SHAPe curriculum in Wave 1 (1 = treatment, 0 = control).

Analytical approach

Model overview

The SABM consists of two submodels that are jointly estimated. The network submodel tests the likelihood of friendship ties between adolescents based on various network selection processes. The behavior submodel captures effects related to changes in behavior over time. Snijders et al., Reference Snijders, van de Bunt and Steglich2010, and Veenstra et al., Reference Veenstra, Dijkstra, Steglich and Van Zalk2013, provide more detailed information about the modeling approach.

Model effects

For the network submodel specification, we considered three types of effects of AB and rejection on network selection; we provide their illustrations by focusing on AB, while including the same effects for rejection. The AB ego effect estimates the effect of AB on an adolescent's tendency to nominate others as friends. A positive effect would indicate that adolescents with greater levels of AB nominated more friends over time. The AB alter effect describes how AB is associated with an adolescent's tendency to receive nominations from peers. A positive effect would indicate that adolescents with higher levels of AB were more likely to be nominated as friends by their peers. The AB similarity effect estimates the tendency of adolescents to nominate friends with similar levels of AB. A positive effect of AB similarity would mean that adolescents were more likely to befriend peers with similar levels of AB.

Next, we included effects to examine interactive associations between AB and rejection in predicting peer selection. Specifically, an interaction between rejection ego and AB alter effects was included to test the default selection of antisocial peers by rejected youth mechanism. We included an interaction between AB ego and rejection alter to examine delinquent peer shopping hypothesis: whether delinquent youth preferred to befriend other socially marginalized youth who might be subsequently more amenable to peer influence in adopting AB of the focal adolescent. Because individual attributes could be associated with peer selection processes via ego, alter, and similarity effects, we also included three additional interactive associations rejection and AB to provide unbiased estimates of the two theoretically relevant interactive effects. An interaction between rejection ego and AB ego examined whether rejected youth who were also high on AB sent out a higher number of outgoing nominations to peers. We also included an interaction between rejection ego and AB similarity to estimate whether rejected youth were more likely to befriend those who resembled them on AB, as well as an interaction between AB ego and rejection similarity to estimate whether antisocial youth were more likely to befriend those who resembled them on rejection status.

Our selection model estimated these effects, while statistically controlling for important confounding processes (Snijders et al., Reference Snijders, van de Bunt and Steglich2010). Specifically, we estimated whether similarity on gender, ethnic/racial background, and treatment condition increased the likelihood of peer selection. We also included parameters for several network structural processes. Reciprocity captured whether adolescents were more likely to nominate peers who had nominated them. We included several degree-related effects. The indegree popularity effect estimated whether students who previously received more nominations were more likely to receive additional nominations over time. The indegree activity effect estimated whether students who received more nominations were more likely to send out a greater number of nominations. Finally, the outdegree activity effect estimated whether students who previously sent out a higher number of ties were more likely to subsequently send many ties. We used a square-root transformation of these activity and popularity effects to give greater weight to differences in popularity and activity at low versus high levels. To assess whether the presence of multiple friends in common increased the likelihood of tie formation (“friends of my friends are my friends”), we included three types of geometrically weighted edgewise shared partners (GWESP) effects. Guided by goodness of fit analyses, we selected a GWESP forward backward effect because it stands for the tendency to form transitive ties over multiple incoming ties. Additionally, a GWESP backward forward effect was included to model the tendency to close structural holes, and GWESP reciprocated ties effect to model the interaction between reciprocity and transitivity. We also included three-cycles effect to model whether having more intermediary ties increases the likelihood of tie formation (without hierarchical ordering). Balance effect modeled the tendency to select ties to other actors who make the same choices as ego (i.e., structural equivalence with respect to outgoing ties; Snijders et al., Reference Snijders, van de Bunt and Steglich2010). Jaccard similarity with respect to outgoing ties was included to model the preference for structural equivalence in outgoing ties. The network function also included effects for outdegree, which controlled for the number of ties. Finally, network rate represented network change opportunities and ln(outdegree+1) was included to account for the dispersion of outdegrees.

For the behavior submodel, we estimated the peer influence effect on AB and rejection using average alter effect; this predicts that a focal adolescent whose friends have a higher average value of the AB and rejection over time also has a stronger tendency toward high values on the AB and rejection, respectively. A positive effect indicates that, over time, focal adolescents increase their AB and rejection status when they affiliate with friends have higher levels of AB and rejection, respectively. To evaluate how participation in the intervention affected the levels of AB and rejection, we estimated effects of treatment on the levels of AB and rejection for changes between Grades 6 and 7 (effFrom). We controlled for gender differences in the mean levels of AB and rejection by estimating effects of gender on the levels of AB and rejection (effFrom). Similarly, to examine whether a reciprocal relationship existed between AB and rejection at the individual level, we examined their main effects on each other. To examine the indirect peer influence effects from peer rejection status to AB and from AB on peer rejection status, we included two alter's covariate average effects, which were defined as (a) a product of ego's AB multiplied by the average of alters’ rejection status, which was used to predict ego's AB over time and (b) a product of ego's rejection status multiplied by the average of alters’ AB in predicting ego's rejection status over time. We then included two reciprocal effects for associations between AB and rejection at the level of an individual by estimating whether (a) ego's levels of AB were associated with ego's levels of rejection and (b) ego's levels of rejection showed an association with ego's levels of AB. Last, for each of the behavioral dimensions, two effects that represent feedback (linear and quadratic shape effects) and rates for behavior change opportunities were included.

Modeling approach

We conducted SABM analyses using RSiena 4.0 (version 1.1-290; Ripley, Snijders, Boda, Voros, & Preciado, Reference Ripley, Snijders, Boda, Voros and Preciado2017) in R. Because we were interested in examining developmental differences across early adolescence, our three-wave panel data allowed us to separately investigate changes in networks and behaviors that occurred in period 1 (from Grades 6 to 7) and period 2 (from Grades 7 to 8). To gain sufficient power to detect peer influence on AB and rejection, we used a multigroup option (Ripley et al., Reference Ripley, Snijders, Boda, Voros and Preciado2017) to assemble one multigroup object across the five networks in period 1 and four networks in period 2 (one network was dropped because of model convergence issues). Whereas the multigroup option has the advantage of boosting the power to detect peer influence effects, it assumes that all parameter estimates are the same across the contexts; thus, we tested whether this assumption was justified by examining school-related heterogeneity by including dummies into our models (i.e., dummy 1 compared an effect for the second school with that of the first school; dummy 2 compared an effect for the third school with that of the second). We conducted the joint score-type tests for school heterogeneity of the final models to show that parameter estimates were homogeneous. We discuss the school differences in parameters in the supplementary analyses. Finally, we assessed goodness of fit for the final models.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for AB, peer rejection, and friendship networks.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics on School-Level Peer Networks

Note. Moran I is a measure of autocorrelation; stability of AB and rejection status as well as Jaccard Index describe stability of behavior and affiliation ties over time, here from Grade 6 to 7 (period 1) from Grade 7 to 8 (period 2). Peer affiliation ties are directed. AB = antisocial behavior; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Confluence model: Testing established pathways

Peer selection on AB

With respect to our SABM results (Table 2), we found that similarity on AB increased the likelihood of peer affiliation from Grades 6 to 7 (AB similarity estimate = 0.49, p < .001) and from Grades 7 to 8 (AB similarity estimate = 0.35, p < .05); these effects appear in path 1 (Figure 1). Moreover, in both cohorts, youth with higher levels of AB were less active in making friends over time (AB outdegree estimate = −0.20, p < .001 for both periods), yet they were more popular as a potential friend (AB indegree estimate = 0.20, p < .001 for both periods).

Table 2. SABM Test of Updated Confluence Model

Note: Pathways are numbered in line with Figure 1. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (all two-tailed). All parameter convergence t-ratios ≤ 0.1; overall maximum convergence ratios were 0.143 for period 1 and 0.117 for period 2. Gender: 1 = female, 0 = male. AB = antisocial behavior; GWESP = geometrically weighted edgewise shared partners; par. = parameter; REJ = rejection status; SE = standard error.

a Treatment was SHAPe curriculum for sixth graders (see Dishion & Kavanagh, Reference Dishion and Kavanagh2003).

Peer influence on AB

We found a significant and positive effect for peer influence on AB (Figure 1, path 3.A) in the younger age cohort (AB average alter estimate = 2.85, p < .001). This suggests that, over time, focal adolescents increased their AB when they affiliated with friends who had higher levels of AB.

Confluence model: New pathways

Peer selection on rejection

Our results documented that, in both cohorts, youth with higher levels of rejection status were more active in sending out friendship nominations over time (rejection outdegree estimate = 0.27, p < .001 for period 1 and rejection outdegree estimate = 0.28, p < .001 for period 2). Additionally, younger adolescents preferred to befriend others with similar levels of rejection status as themselves (rejection similarity estimate = 0.40, p < .05); these effects appear in Figure 1, path 1.B.

Peer influence on rejection

We documented a significant and positive effect for peer influence on rejection status (Figure 1, path 3.B) in the younger age cohort (rejection average alter estimate = 2.18, p < .001). This suggests that, over time, focal adolescents were more likely to become rejected by their peers when they affiliated with friends who had higher levels of rejection status.

Interaction between rejection and AB as contributing to peer selection

To examine confluence processes shaping peer selection (Figure 1, path 2), we tested several interaction effects to examine how focal youth's AB and rejection status interacted to predict friendship selection. We documented a significant and negative interaction between ego rejection status and AB alter effect (estimate = −0.15, p < .05) and significant and negative interaction between ego rejection status and AB similarity effect (estimate = −0.41, p < .05) during the transition from Grades 6 to 7. During the transition from Grades 7 to 8, another significant and negative interaction between ego rejection status and AB similarity effect emerged (estimate = −0.51, p < .05). To better understand these interactions, we calculated separate estimates for rejected and nonrejected youth in the section below (i.e., similar to a simple slope analysis in ordinary least squares regression).

Indirect influence on AB and rejection

Our results did not reveal that a significant indirect influence (Figure 1 path 6) operated such that friends’ levels of AB were not associated with changes in the focal adolescent's rejection status (Grades 6 to 7 estimate = −0.84, p = .20; Grades 7 to 8 estimate = −0.66, p = .31) and that friends’ rejection status was not associated with changes in the focal adolescent's AB (Figure 1, path 7; Grades 6 to 7 estimate = −0.91, p = .30; Grades 7 to 8 estimate = −5.57, p = .23).

Reciprocal associations between AB and rejection

Considering reciprocal associations between AB and rejection status (Figure 1, path 8), we found that during both transitions adolescents who had higher levels of AB were more likely to increase in their rejection status over time (estimate = 0.77, p < .01 for period 1 and rejection outdegree estimate = 0.93, p < .05 for period 2), but adolescents who had higher rejection status were not more likely to increase in their AB over time (Grades 6 to 7 estimate = 0.30, p = .75; Grades 7 to 8 estimate = 2.04, p = .79).

Controlling for gender and classroom-based intervention status differences in predicting AB, rejection status, and friendship selection

We did not find significant gender differences in the changes in main levels of AB (Grades 6 to 7 estimate = 0.17, p = .72; Grades 7 to 8 estimate = −0.28, p = .72) and rejection (Grades 6 to 7 estimate = −0.07, p = .64) over time; however, girls were more likely to increase their rejection status from Grades 7 to 8 (estimate = 0.52, p < .05). Random assignment to the SHAPe curriculum affected network selection such that adolescents who participated in the classroom-based intervention were more likely to affiliate with one another from Grades 6 to 7 (treatment similarity estimate = 0.10, p < .001) and intervention group youth sent out more friendship nominations between Grades 6 and 7 compared with control group (treatment ego estimate = 0.05, p < .05). We also tested whether participating in the SHAPe curriculum contributed to changes in AB (estimate = 0.32, p = .84) and rejection (estimate = 0.04, p = .29) from Grades 6 to 7 and documented no significant associations.

Controlling for potentially confounding network selection processes

We obtained these results while statistically controlling (i.e., estimated in the same model) for network selection processes (e.g., preference to affiliate with friends of the same gender, race; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001). Our results indicated that younger by not older cohort adolescents were more likely to select peers of the same gender (younger estimate = 0.12, p < .001; older estimate = 0.03, p = .75). We did not document a significant preference for homophily on race-ethnicity (younger estimate = 0.06, p = .78; older estimate = 0.01, p = .56). Finally, we also examined several commonly observed network structural processes and documented that, across both developmental transitions, youth were more likely to nominate peers who had nominated them (reciprocity estimates of 0.79 and 1.05, p < .001). We also found evidence that the presence of multiple friends in common increased the likelihood of tie formation (“friends of my friends are my friends”; Davis, Reference Davis1970). Specifically, we documented a significant and positive tendencies (a) to form transitive ties across multiple incoming ties (GWESP forward backward effect estimates of 0.44 and 0.65, p < .001), (b) to close structural holes (GWESP backward forward effect estimates of 0.39 and 0.22, p < .001), and (c) to reciprocate ties with others who have friends in common (GWESP reciprocated ties effect estimates of 0.25 and 0.28, p < .001). We also found that, controlling for the previously discussed effects, having more intermediary ties decreased the likelihood of tie formation (without hierarchical ordering; three-cycles effect of −0.10 and −0.07, p < .001) and that youth preferred selecting ties to other actors who make the same choices as ego (Jaccard similarity with respect to outgoing ties effect of 7.92 and 4.64, p < .001). We also found that students who previously received more nominations were more likely to receive additional nominations over time (indegree popularity effect of 0.22 and 0.26, p < .001), whereas those students who sent out an increasing number of friendships nomination were less likely to receive a higher number of incoming nominations (indegree activity effect of −0.57 and −0.64, p < .001) and send out even more outgoing nominations (outdegree activity effect of −0.23 and −0.10, p < .001) over time. Finally, network rate represented network change opportunities, and ln(outdegree+1) was included to account for the dispersion of outdegrees. Taken together, these findings point that our friendship networks formed according to fundamental network processes.

Follow-up analyses for the significant interaction between rejection and AB as contributing to peer selection

To further elaborate on how peer selection processes regarding AB were different for rejected and nonrejected youth, we calculated two separate ego-alter tables following the formulas presented in Lomi et al. (Reference Lomi, Snijders, Steglich and Torló2011). These ego-alter tables illustrate the model-predicted probabilities that rejected and nonrejected youth with particular levels of AB were likely to select friends of a particular level of AB. Because our models revealed that estimates for multiple network selection processes with respect to AB and rejection status are jointly unfolding in networks, constructing ego-later selection enables a holistic look across all significant processes (Ripley et al., 2018). The values presented in each table are the odds that an ego of a specified AB level selects as a friend an alter with a certain AB level versus an alter with any other level of AB; these values are calculated separately for rejected and nonrejected youth (Table 3). To compute the ego-alter table for rejected and nonrejected youth, we used parameter values from the related effects in the model including rejection ego, main effects of AB ego, AB alter, and AB similarity as well as two significant interactions for period 1 and one significant interaction for period 2 (Table 2). Again, because of internal centering of variables in SABM, we calculated these group-specific selection values using (1-mean rejection) for nonrejected youth and (3- mean rejection) for rejected youth.

Table 3. Ego-Alter Tables for Log Odds of Friend Selection Based on Antisocial Behavior for Rejected and Nonrejected Status Adolescents

AB = antisocial behavior.

Group differences revealed by these ego-alter selection tables elaborate on the results from the group-specific AB selection patterns for each period. Specifically, during transition from Grades 6 to 7, a rejected adolescent with lowest level of AB had 5.5% lower odds of choosing a friend with the same lowest level of AB than a friend with the highest level of AB (= exp (0.251)/exp. (0.307)) × 100–100 = −5.5%). A rejected adolescent with highest level of AB had 12% lower odds of choosing a friend with the same highest level of AB than a friend with the lowest level of AB (=exp (−0.187)/exp (−0.055)) × 100–100 = −12%). On the other hand, a nonrejected adolescent with lowest level of AB had 15% higher odds of choosing a friend with the same lowest level of AB than a friend with the highest level of AB. A nonrejected adolescent with highest level of AB had 255% higher odds of choosing a friend with the same highest level of AB than a friend with the lowest level of AB.

Furthermore, during transition from Grades 7 to 8, a rejected youth with lowest level of AB had 56% lower odds of choosing a friend who reports the same lowest level of AB than a friend with highest level of AB. A rejected adolescent with the highest level of AB had 2% lower odds of choosing a friend with the same highest level of AB than a friend who reported the lowest level of AB. Finally, a nonrejected youth with lowest level of AB had 22% higher odds of choosing a friend who reported the same lowest level of AB than a friend with the highest level of AB. A nonrejected adolescent with highest level of AB had 172% higher odds of choosing a friend with the same highest level of AB than a friend with the lowest level of AB.

As the last steps in our modeling approach, we conducted additional analyses to ascertain that (a) the reported peer selection and influence effects were homogeneous across the five school contexts and (b) the final models provided adequate fit to the data (see Online Appendix for details).

Discussion

Given the personal and societal costs incurred from adolescent AB (Greenberg & Lippold, Reference Greenberg and Lippold2013; Loeber & Farrington, Reference Loeber and Farrington2000), our goal was to better understand multiple peer processes through which these behaviors emerge and become amplified within school settings. Expanding the peer confluence model of AB (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Patterson, Griesler and Huesmann1994) from a peer network dynamics perspective, we tested a host of complex and reciprocal pathways between AB and rejection status that are co-evolving within changing peer networks during adolescence. In line with previous findings supporting the established pathways of the confluence model (for reviews see Gallupe et al., in press; Sijtsema & Lindenberg, Reference Sijtsema and Lindenberg2018), our results also documented peer selection and influence patterns related to AB during adolescence. Additionally, through an extension of the confluence model, we found that rejection status was associated with friendship selection and that adolescents became rejected by their peer group if they were friends with others who were rejected by their peers. Moreover, our findings also pointed to an interactive pattern of associations among peer rejection, AB, and network selection. Specifically, for both developmental transitions in middle school, rejected youth with low levels of AB were more likely to befriend others with higher levels of AB. This pattern could stem from the proposed default peer selection dynamics. In contrast, nonrejected youth preferred to befriend others with similarly high or low levels of AB. Significant patterns of peer influence were documented in the younger cohort, in that youth increased their AB and rejection status when they were friends with others who were also rejected and delinquent. In sum, these findings provide support for the updated confluence model underlying peer contagion on AB (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Patterson, Griesler and Huesmann1994).

This study makes several novel contributions to research and theory on the role of peer relationships in the development of antisocial behavior. Among key contributions of this study is the documentation of new interactive dynamics that underpin aggregation and peer influence processes with respect to rejection status. We found that, across both developmental transitions, rejection status was associated with friendship network selection patterns such that rejected youth were not socially isolated but were active in creating new friendships and maintaining existing ones. Of interest, among the younger cohort, friendship network selection was significantly affected by the preference to befriend others who have similar levels of rejection as the focal youth. Whereas a preference to affiliate with similarly nonrejected friends is expected given adolescents’ heightened sensitivity to and pursuit of social status (Sijtsema & Lindenberg, Reference Sijtsema and Lindenberg2018), befriending similarly rejected youth might occur because of a limited pool of potential friends (i.e., default selection pattern; Sijtsema et al., Reference Sijtsema, Rambaran and Ojanen2013). This finding is consistent with the theorized mechanisms of peer rejection homophily such that peer rejection augments the value of any peer interaction, even a low-quality one, which leads to rejected youth selecting each other as friends and resulting in clustering of rejected peers (Dishion, Piehler, & Myer, Reference Dishion, Piehler, Myers, Prinstein and Dodge2008). These observations contribute to a small body of evidence revealing that rejected youth do have friends and that these friends are more likely to be rejected from the peer group (Deptula & Cohen, Reference Deptula and Cohen2004; Gest et al., Reference Gest, Graham-Bermann and Hartup2001). Taken together, this evidence underscores the need for continued attention to how rejected adolescents are forming their friendships to mitigate their aggregation into clusters of rejected youth in which limited opportunities may exist for mastery of social skills (Coie & Kupersmidt, Reference Coie and Kupersmidt1983; Dishion, Reference Dishion and Leone1990; Dodge, Reference Dodge1983) and engagement in risk-taking behaviors is likely to occur (Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Banny, Kawabata, Crick and Gau2013) and be amplified via deviancy training processes (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Patterson, Griesler and Huesmann1994).

Our results documented, for the first time, a significant peer influence on rejection status, suggesting that, over time, youth tend to shift their peer rejection status in the direction of their friends. This finding extends an emerging body of research documenting that, over time, adolescents influenced one another's popularity levels over time and that this effect was above and beyond preferences to affiliate with popular youth and network structural processes (Dijkstra, Cillessen, & Borch, Reference Dijkstra, Cillessen and Borch2013; Marks, Cillessen, & Crick, Reference Marks, Cillessen and Crick2012). Although more evidence is needed to support firm conclusions, given the documented pattern of elevated risks of deviant peer involvement associated with being rejected, a peer contagion of rejection is particularly problematic for adolescents. Thus, directing future empirical attention to the mechanisms through which peer influence on rejection operates in networks appears to be warranted. Our exploratory attempt to examine whether indirect socialization operated in peer networks such that friends’ levels of rejection contributed to the focal adolescent's levels of antisocial behavior and vice versa did not provide evidence for such cross-dimensional peer influence effects, which has been previously reported for nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors and depressive symptoms (Giletta, Burk, Scholte, Engels, & Prinstein, Reference Giletta, Burk, Scholte, Engels and Prinstein2013) and academic achievement and risk-taking behavior (Gremmen, Berger, Ryan, Steglich, Veenstra, & Dijkstra, Reference Gremmen, Berger, Ryan, Steglich, Veenstra and Dijkstra2018).

Another contribution of this study focuses on uncovering interactive pathways of the confluence model through which AB and rejection jointly shape friendship selection processes. Our results showed that rejected youth with low levels of AB were less likely to befriend others with similarly low levels of AB and tended to affiliate with others who had highest levels of AB. This finding provides specific evidence for interpersonal mechanisms through which socially excluded but not yet engaging in antisocial behavior adolescents create deviancy-promoting peer ecologies in which they are likely to subsequently adopt and escalate their antisocial behavior. This pattern may also stem from the default selection processes that have been documented in previous research (Lodder et al., Reference Lodder, Scholte, Cillessen and Giletta2016; Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Dijkstra, Salmivalli and Cillessen2013; Sijtsema et al., Reference Sijtsema, Rambaran and Ojanen2013). This pattern suggests that, when faced with a limited pool of potential friends, rejected youth befriend others who are available, those who become increasingly likely to exhibit academic skill deficits and antisocial behavior (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller and Skinner1991) and, over time, become involved in gangs (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Nelson and Yasui2005). Being rejected by one's social group is a major survival threat, according to an evolutionary perceptive, signaling the need to adopt and escalate an array of problem behaviors because such behaviors may serve a function of securing and maintaining a group membership (Dishion, Reference Dishion, Dishion and Snyder2016; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Del Giudice, Dishion, Figueredo, Gray, Griskevicius and Wilson2012).

Of interest, rejected youth who were already engaging in higher levels of AB were less likely to befriend others with similarly high levels of AB. This seemingly contradictory finding may need to be considered within the broader context of engagement with nonaggressive peers as a means of boosting one's social status by befriending non-AB individuals and influencing them to engage in AB (Dishion et al., 1996; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt1993). This pattern of friendship selection is also in line with the shopping hypothesis (Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, Reid and Dishion1992; Stoolmiller, Reference Stoolmiller1990) that we now find to be applicable to friendship formation processes of adolescents who are both rejected by their peers and engage in high levels of delinquent activities. Taken together, these findings underscore a certain degree of heterogeneity in the friendship selection processes for rejected and nonrejected youth, which would be of vital importance to understand to devise and implement effective intervention programs for rejected youth.

Our results from interactive pathways between rejection status and AB revealed a different pattern of friendship selection through which nonrejected adolescents appear to have been structuring their peer ecologies. For both developmental transitions within middle school, we found that nonrejected youth have a strong preference for homophilous selection on AB; in other words, those with low levels of AB prefer friends with low levels of AB and those with high levels befriend those with high levels of AB. It is noteworthy that the strength of this preference was much stronger for youth who were engaging in higher levels of AB compared with those with lower levels of AB (i.e., 255% vs. 15% higher odds for the younger cohort and 172% vs. 22% higher odds for the older cohort). These observations are in line with decades of theorizing that antisocial behavior is used as a means of social status acquisition during adolescence (Dishion et al., 1996; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt1993).

This study advances an ecological understanding of the development of adolescent problem behaviors, guided by the developmental cascades perspective (Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010) and an interactive view on an individual adaptation and developmental contexts (Dishion, Véronneau, & Myers, Reference Dishion, Véronneau and Myers2010). These perspectives suggest that even small deviations from normative development (e.g., child noncompliance) interact with the environment and, over the course of development, develop into antisocial and violent behavior (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Véronneau and Myers2010). Prior research has corroborated cascading effects over longer periods, in which initial behavior problems continue and intensify into violent behavior within family and school systems (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Véronneau and Myers2010; Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010). Complementing the emphasis on the long-term developmental cascades, the present study unpacked a host of transactional dynamics on a shorter timescale through which peer networks shape rejection and AB in the school context. Social network perspective and analytical tools used in this study revealed a complex pattern of associations among rejection and AB, characterized by feedback loops that peer ecology has shaped. As such, this study advances the developmental cascade and transactional models by outlining distinct contributions of peer rejection and network dynamics to the etiology of AB.

These novel contributions emerged because of methodological advantages applied to the examination of the dynamic links between peer dynamics linking rejection and AB. Specifically, our use of longitudinal SNA modeling (Snijders et al., Reference Snijders, van de Bunt and Steglich2010) allowed us to disentangle peer selection from influence processes on AB and rejection, while controlling for important confounding processes. Deploying this modeling approach yields more accurate estimates of peer selection and influence contributions to AB and rejection because the model simultaneously estimates a host of confounding processes (i.e., network structural processes, school contextual dynamics, and selection on individual attributes such as gender and race or ethnicity). Failure to account for these alternative mechanisms that promote peer selection risks overestimating the role of AB and rejection in peer selection and influence. Moreover, longitudinal SNA modeling framework permits considering both main effects and interactive associations between AB and rejection as embedded in peer network dynamics. Identifying significant moderators of peer selection and influence dynamics sheds light on mechanisms of peer contagion, uncovering which is critical for advancing developmental theory and informing interventions to disrupt peer contagion (Dishion & Tipsord, Reference Dishion and Tipsord2011; Prinstein & Giletta, Reference Prinstein, Giletta and Cicchetti2016).

An additional strength of this study is its use of peer-reported measures of antisocial behavior and rejection, creating a score for each youth that reflects an aggregated perspective of the peers providing the ratings, thus reducing self-report bias. Although this score has methodological strengths, the AB reported by peers is likely restricted to the school setting. In this sample, we observed that some of the middle school students engaged in gang activity, which involved problem behaviors that occurred largely outside the school context (e.g., drug use, drug sales, stealing, vandalism); thus, there are some limitations to testing the interaction of rejection status and AB hypotheses with the network data derived solely from a school setting. For example, in early adolescence, the sheer number of hours youth spend with peers unsupervised by adults predicts growth in problem behavior from ages 12 to 15 (Dishion, Bullock, & Kiesner, Reference Dishion, Bullock, Kiesner, Kerr, Stattin and Engels2008). Moreover, antisocial males tend to select friends more often from the neighborhood and less from school settings (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Andrews and Crosby1995; Kiesner, Kerr, & Stattin, Reference Kiesner, Kerr and Stattin2004).

Our findings on peer influence of AB during the Grade 6 to 7 transition, which we assessed with peer-reported measures in this study, diverge from prior results from this sample relying on self-reported frequency of antisocial and violent behaviors, most likely because of the use of reciprocated hang out ties as well as a differing operationalization of peer influence (Kornienko, Dishion, & Ha, Reference Kornienko, Dishion and Ha2017). Of interest, peer-reported measures of AB used in this study had a stronger effect on peer network selection dynamics compared with self-reported measures of deviancy and violence, which could be done covertly, outside of school, leading to a restricted knowledge by school peers, as examined by Kornienko and colleagues (Reference Kornienko, Dishion and Ha2017).

Future research needs to examine what role academic functioning, which is another integral aspect of adaptation to the school environment (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Véronneau and Myers2010), plays in a complex web of associations between problem behavior and rejection in school peer networks. Earlier intervention studies show that academic and peer domains relate reciprocally during adolescence in that mitigation of peer problems improves academic functioning (Stormshak, Connell, & Dishion, Reference Stormshak, Connell and Dishion2009). Another set of potent contributors to the etiology of externalizing behavior uncovered in developmental cascade models includes poor family management, parental monitoring, and coercive processes (Dishion & Patterson, Reference Dishion, Patterson, Cicchetti and Cohen2006) as well as neuropsychological deficits such as inattention and impulsivity coupled with family adversity (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt1993). These processes could therefore also contribute to amplifying rejection-antisocial behavior dynamics in peer networks. Future research would benefit from detailed attention to these variables as moderators of peer mechanisms. Understanding these dynamics as unfolding in peer networks is important for designing effective interventions.

Considering clinical implications, this study included a randomized, multiphase intervention in which randomization placed Grade 6 students into their Grade 7 homerooms, with intervention classrooms receiving a universal SHAPe curriculum aimed to reduce substance use and other health-risk behaviors. Based on this randomization, schools created a homeroom environment that encouraged discussions of norms and behaviors related to health, which included antisocial behavior (Dishion & Kavanagh, Reference Dishion and Kavanagh2003). Our analyses revealed that friendships were more likely to form during the transition from Grades 6 to 7 among students who participated in SHAPe curriculum and that these youth were more active in sending out friendship nominations, suggesting their better social integration over time. Although the intervention delivered in the homeroom may have created more camaraderie among students, it is equally likely that simple proximity led to increases in friendship formation. Previous research with this sample found that in one of three schools that implemented the SHAPe curriculum, youth in the intervention classrooms were more likely to befriend others with similarly high or similarly low delinquency levels (Delay et al., Reference DeLay, Ha, Van Ryzin, Winter and Dishion2016). It is noteworthy that self-reported frequency of deviant peer affiliation examined by DeLay and colleagues (Reference DeLay, Ha, Van Ryzin, Winter and Dishion2016) included behaviors targeted in the SHAPe curriculum; they explicitly focused on examining intervention effects on targeted behaviors as mediated by peer network dynamics. Perhaps youth involved in the intervention classes reduced their reports on delinquent behaviors that their classes discussed. Taken together, these studies underscore that a simple intervention such as randomly assigning youth to a homeroom class can affect students’ choices of friends.

In summary, using the conceptual and analytical tools of the peer network dynamics perspective enabled us to provide a comprehensive test of the updated confluence model. Consistent with the model's propositions, we documented a joint interplay between peer rejection and AB that created conditions leading to self-organization into deviant clusters in which peer contagion on problem behaviors operated. This study elucidated a distinct role of peer network processes that shape and are shaped through interactive contributions of antisocial behavior and peer rejection within the school context. Although additional research is needed on specific mechanisms underlying these dynamics, our findings point to a possibility that successful interventions that disrupt the etiology of antisocial behavior within school context also can disrupt peer rejection dynamics. We advocate for the focus on peer rejection because it amplifies deviant peer clustering, thus creating a social context for deviancy training and amplification of antisocial into violent behavior (Dishion & Patterson, Reference Dishion, Patterson, Cicchetti and Cohen2006).

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418001645

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thomas J. Dishion for his contribution and invaluable support. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the Project Alliance staff, Portland Public Schools, and the participating youths and families.

Financial support

A National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Award (L30 DA042448) supported Olga Kornienko for her work on this manuscript. Thao Ha and Thomas J. Dishion were supported by Grants DA07031 and DA13773 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Grant AA022071 from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.