The pubertal transition represents an important period for psychological development. Normative changes in maturation have been shown consistently to influence psychological changes that occur in many youth (such as increased risk taking) and to trigger psychopathology in vulnerable youth. Variations in pubertal development also have psychological consequences. The best-documented links are between early maturation in girls and a host of behavior problems in adolescence (for reviews, see Ge & Natsuaki, Reference Ge and Natsuaki2009; Graber, Reference Graber2013; Negriff & Susman, Reference Negriff and Susman2011), with some problems likely persisting into adulthood (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Miller, Costello, Angold and Maughan2010; Graber, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Graber, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Brooks-Gunn1997; Graber, Seeley, Brooks-Gunn, & Lewinsohn, Reference Graber, Seeley, Brooks-Gunn and Lewinsohn2004; Mendle, Ryan, & McKone, Reference Mendle, Ryan and McKone2018). There is also evidence that off-time maturation in boys confers psychological risk, with the best evidence showing that late maturing boys are at risk for depression in adulthood (Beltz, Reference Beltz2018; Gaysina, Richards, Kuh, & Hardy, Reference Gaysina, Richards, Kuh and Hardy2015; Graber, Reference Graber2013).

These studies linking early puberty to psychological problems are generally premised on the idea that puberty induces a change in psychological functioning, but this is generally not tested. Instead, studies focus on contemporaneous associations between puberty and behavior, and some focus on the long-term consequences of pubertal timing (whether puberty continues to have behavioral significance in adulthood). It is thus important to examine the role of puberty in inducing change from childhood through puberty to the postpuberty period, not just changes in behavior at or after puberty.

Does Puberty Induce Behavioral Change? The Role of Early Events in Links Between Puberty and Adolescent Problem Behavior

Links between puberty and problem behaviors are generally assumed to be causal, with puberty inducing psychological change directly through hormone effects on the brain, and indirectly through new social experiences that affect the developing brain and stress systems (e.g., Blakemore, Burnett, & Dahl, Reference Blakemore, Burnett and Dahl2010; Dahl & Gunnar, Reference Dahl and Gunnar2009). Nevertheless, puberty effects may be complex and may depend on behaviors present before puberty. Thus, it is important to consider how events before puberty contribute to links between puberty and subsequent behavior.

Stability of behavior

Many behavior problems have their origins in childhood, and behavior problems are moderately stable across age, including from childhood to adolescence. For example, behavior problems on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) show moderate to large correlations (.37 to .57) in both sexes from ages 7 to 10 to ages 15 to 18 (Verhulst & van der Ende, Reference Verhulst and van der Ende1995); similar correlations are found for broad categories and specific behavior problems such as aggression (e.g., Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, Reference Bornstein, Hahn and Haynes2010; McElroy, Shevlin, & Murphy, Reference McElroy, Shevlin and Murphy2017; Obradović, Pardini, Long, & Loeber, Reference Obradović, Pardini, Long and Loeber2007; Olweus, Reference Olweus1979). Thus, puberty may not trigger those problems so much as reflect the continuity of psychological processes started in childhood.

The limited evidence on links between childhood behavior and pubertal development is inconsistent. In one study (Mensah et al., Reference Mensah, Bayer, Wake, Carlin, Allen and Patton2013), 8- to 9-year-old children who had already started puberty (by parent report) were seen to have poorer (parent-reported) psychosocial adjustment at those ages and beforehand (ages 4 to 5 and 6 to 7) than those who had not started puberty early, and early maturing boys, but not girls, also had more behavioral difficulties than those who had not yet started puberty. The results suggest that children with early puberty are psychologically different from on-time peers well before puberty starts, but interpreting these results is complicated by several factors including stronger effects in boys than in girls (links between pubertal timing and adolescent behavior are stronger in girls than in boys); the confounding effects of child race, body-mass index, and family socioeconomic status (covariate analyses showed these factors to only partially explain links between early puberty onset and behavior, but their effects may be nonlinear); reliance on a single, weak measure of pubertal onset (grouping based on parent report); and an unusually high proportion of children with early pubertal onset (perhaps reflecting sample characteristics). Furthermore, assessments only went to ages 10 or 11, so it is not clear that adolescent behavior problems were being assessed.

In contrast, another study found no significant links between girls’ (parent-reported) behavior problems at ages 7 and 9 and menarcheal age (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1991). There do not appear to be any other studies that examined associations between childhood behavior problems and pubertal timing.

Individual differences in the significance of puberty

Puberty has been seen to have particular psychological significance for girls who are already at psychological risk (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1991). Behavior problems were highest among girls who had both early menarche (by self report, with missing data supplemented by mother report) and (parent-reported) childhood behavior problems. Several methodological issues complicate interpretation, however, including the confounding of pubertal timing and status (adolescent problems were assessed at ages 13 and 15, when participants varied in pubertal status); reliance on a single retrospective measure of menarche by different reporters (mostly girls but sometimes mothers); and reduced power with use of categories for pubertal timing. The study results also do not appear to have been replicated.

Effects of early environment

Early environmental factors that are linked to behavior problems may also influence pubertal timing (for discussion, see Ellis, Reference Ellis2004), although links between early adversity and pubertal timing are inconsistent. Consider some examples. Sexual abuse has been linked to earlier puberty in girls (Negriff, Blankson, & Trickett, Reference Negriff, Blankson and Trickett2015). Father absence also has been linked to earlier puberty in girls (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Steinberg, Houts, Friedman, DeHart, Cauffman and Susman2007), but this may apply only to some girls (e.g., those in families with high income; Deardorff et al., Reference Deardorff, Ekwaru, Kushi, Ellis, Greenspan, Mirabedi and Hiatt2011). Similarly, maternal harshness has been linked to accelerated puberty in girls in some studies (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Steinberg, Houts, Friedman, DeHart, Cauffman and Susman2007) but not in others (Kim & Smith, Reference Kim and Smith1999) and with some measures of puberty but not others (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Steinberg, Houts, Friedman, DeHart, Cauffman and Susman2007). Within a study, girls’ pubertal development has been linked to one measure of parenting but not to other related ones (e.g., to maternal harshness, but not to maternal sensitivity, father presence, or father harsh control, Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Steinberg, Houts, Friedman, DeHart, Cauffman and Susman2007). Clearly, the effects of early family function on pubertal timing are complex.

Further evidence about the importance of prepubertal behavior comes from a study (James, Ellis, Schlomer, & Garber, Reference James, Ellis, Schlomer and Garber2012) showing that childhood adversity is associated with early puberty, which in turn is associated with sexual risk taking. Childhood adversity is itself associated with behavior problems contemporaneously and later in life; for example, children who receive negative parenting (e.g., harsh, controlling) are more likely to have behavior problems at the time (e.g., Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, Reference Campbell, Shaw and Gilliom2000; Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller, & Snyder, Reference Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller and Snyder2004; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017) and in adolescence (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017), although the associations are small. This indirectly implicates prepuberty behavior in links between puberty and adolescent behavior.

Focus on Girls

A limitation of previous work is its focus on girls, with limited attention to boys. Some of this emphasis is conceptual. Girls’ reproductive development may be particularly influenced by context. However, most of the focus on girls reflects methodology; there is no convenient marker in boys that corresponds to menarche in girls (Dorn, Dahl, Woodward, & Biro, Reference Dorn, Dahl, Woodward and Biro2006). There is value in understanding the links between puberty and behavior problems in both sexes.

Present Study

Given the considerable interest in the consequences of pubertal development for psychological and neural development, it is important to study the open questions regarding the role of prepuberty behavior problems in the link between puberty and later problems. In particular, the causal role of pubertal timing needs to be studied. Does early puberty cause adolescent behavior problems, as is often assumed, or does the timing-behavior link reflect the continuity of behavior and early behavioral influences on pubertal timing? Also, does pubertal timing matter more for some youth than for others, with the maximum effect for early maturers with a childhood history of behavior problems (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1991)? Furthermore, the focus should extend beyond girls to consider the psychological significance of puberty in boys, too. Therefore, we examined in both sexes (a) the links among behavior problems in childhood, pubertal timing, and behavior problems in middle to late adolescence and early adulthood to determine whether puberty produces change in behavior from prepuberty to adolescence and whether pubertal timing mediates links between childhood and adolescent behavior and (b) the moderating effects of pubertal timing on the links between childhood and adolescent behavior problems, examining whether early puberty is particularly significant for children with a history of childhood behavior problems. We used data from two longitudinal studies spanning childhood to early adulthood, with estimates of pubertal timing for both boys and girls based on longitudinal modeling (not simply self-reported menarche in girls).

Method

This study is an extension of previously reported work concerned with links between puberty and adolescent development. Previous work was focused on puberty and subsequent behavior. Longitudinal self-reports of physical features were used to model pubertal development, and pubertal variations were then linked to postpuberty psychological problems and the genetic and environmental sources of covariations between puberty and behavior were examined (Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth, & Berenbaum, Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014; Corley, Beltz, Wadsworth, & Berenbaum, Reference Corley, Beltz, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2015). In brief, those studies showed that self-reports of pubertal development from ages 9 to 15 were best described by a logistic model. Linear and logistic estimates of pubertal timing correlated highly with each other in both boys and girls and with age at menarche in girls, and all of the estimates of pubertal timing correlated similarly with internalizing and externalizing problems in middle to late adolescence/early adulthood. Early puberty was associated more with some psychological outcomes (drug symptom counts, age at first sex) than others (depression, conduct disorder), with links more likely to be significant in girls than in boys. The estimates of pubertal tempo were not consistent across methods, and they were not clearly correlated with psychological outcomes. Also, there was a large genetic contribution to all of the estimates of pubertal timing for both boys and girls; genetic covariation accounted for most of the phenotypic correlations among estimates of pubertal timing and between pubertal timing and adolescent behavioral outcomes.

The current study provides new data on the longitudinal chain from childhood behavior problems to puberty to postpuberty behavior problems by adding behavioral measures obtained before puberty. The participants and postpuberty measures are those reported previously. Novel data include those for prepuberty behavior.

Participants

The participants came from two longitudinal genetically informative studies, the Colorado Longitudinal Twin Study (LTS) and the Colorado Adoption Project (CAP), which examine genetic and environmental contributors to variations in cognition, personality, and behavior problems (Plomin & Defries, Reference Plomin and Defries1985; Rhea, Gross, Haberstick, & Corley, Reference Rhea, Gross, Haberstick and Corley2006). The participants are being followed into adulthood in CATSLife. The original LTS sample consisted of 966 individuals from 483 twin pairs and the original CAP sample consisted of 732 subjects from 490 families.

The current sample of 1,084 participants (534 girls, 550 boys) is a subset of a sample whose pubertal development was modeled and linked to adolescent behavior (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014). The initial sample included 1,460 individuals with longitudinal data on pubertal status, of whom 1,359 also had data on at least one measure of behavior problems in adolescence. For this study, we also required that participants have data on childhood behavior problems (described below). We also added six participants for whom data on age at first sex became available but who had no other data on adolescent behavior. The sample includes 550 participants from LTS (167 monozygotic [MZ] girls, 114 dizygotic [DZ] girls, 125 MZ boys, and 144 DZ boys), and 534 participants from CAP (114 adopted girls, 139 nonadopted girls, 120 adopted boys, and 161 nonadopted boys). Most of the participants were White (92%) and not Hispanic (95%). Within-family dependencies were handled in the analyses as described below.

The participants were assessed on multiple occasions from infancy through young adulthood; the focus here is on assessments of behavior problems in childhood and middle to late adolescence/early adulthood and on pubertal timing. Prepuberty behavior problems were indexed by parent report at age 7. This age was specifically chosen to reflect the period before pubertal onset for all participants. Postpuberty behavior problems were assessed by self- and parent-report between ages 16 and 18, except for age at sexual initiation, which was assessed at multiple times from age 17 to young adulthood. Puberty was assessed annually with self report from the end of grade 3 to the end of grade 9, with an in-person visit after grade 6 and telephone interviews at the other ages. All of the assessments also included other measures that are not reported here.

Adopted children are known to have more behavior problems (e.g., Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Iacono, & McGue, Reference Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Iacono and McGue2008), and adopted girls to have earlier puberty (Brooker, Berenbaum, Bricker, Corley, & Wadsworth, Reference Brooker, Berenbaum, Bricker, Corley and Wadsworth2012; Mason & Narad, Reference Mason and Narad2005) than children who are genetically related to their parents. In the CAP sample, both adopted girls and boys tended to show earlier and higher levels of adolescent substance experimentation (Wadsworth et al., Reference Wadsworth, Corley, DeFries, Fulker, Carey and Plomin1997) than did nonadopted children; adopted girls were seen to have earlier menarche, earlier sexual initiation, and more conduct disorder symptoms in adolescence than nonadopted girls (Brooker et al., Reference Brooker, Berenbaum, Bricker, Corley and Wadsworth2012), with age at menarche partially mediating the link between adoption status and age at sexual initiation but not conduct disorder symptoms. Therefore, adoption status was included as a covariate in the analyses.

Measures

Pubertal timing

Puberty was assessed by annual self report on the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer1988). The longitudinal data were used in growth curve modeling separately for girls and boys to estimate pubertal timing (i.e., age at mid-puberty) based on a logistic model (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014). For girls, age at menarche was also recorded, using self reports at each age. (Details of the modeling procedures and results and a discussion of the strengths and limitations of self-reported PDS scores are provided in Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014.)

Behavior problems in childhood and adolescence

At ages 7 and 16, participants’ behavior problems were assessed with parent reports on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991). We used raw scores for higher-order scales of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems (age-corrected within sex), which have been shown to relate to a variety of clinical conditions. At age 7, we used Total Behavior Problems, as it was the best measure to use to replicate previous work (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1991). At age 16, we used the separate scales for Internalizing and Externalizing Problems, also consistent with previous work on correlates of pubertal timing (e.g., Negriff & Susman, Reference Negriff and Susman2011). Internal consistency reliabilities were high in this sample: For Total Problems at age 7, alpha = .94; for Internalizing and Externalizing Problems at age 16, alpha = .88 and .92, respectively.

Adolescent depression

At age 17, the participants described their mood over the past week using The Center for Epidemiologic Studies at the National Institute of Mental Health Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). The psychometric properties of this 20-item survey are good: Internal consistency reliability is .85–.90 (.87 in this sample), and the scores discriminate between clinical and general population samples and correlate with other scales of depression.

Adolescent substance use

At ages 16 to 18, the participants reported involvement with substances including alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines, opiates, cocaine, sedatives, inhalants, PCP, and hallucinogens, using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM; Cottler & Keating, Reference Cottler and Keating1990), which has discriminative and convergent validity (Crowley, Mikulich, Ehlers, Whitmore, & MacDonald, Reference Crowley, Mikulich, Ehlers, Whitmore and MacDonald2001). For each substance, participants retrospectively reported whether they had had any of seven lifetime dependence symptoms during assessments between ages 16 and 18. An overall measure of an individual's substance involvement was the mean number of lifetime symptoms that were reported during adolescence across all substances (alpha = .73). The scores were normed with regard to sex and age on adolescents from several samples, with participants in the current study comprising about one-third of the norming sample (Button, Hewitt, Rhee, Corley, & Stallings, Reference Button, Hewitt, Rhee, Corley and Stallings2010; Rhea et al., Reference Rhea, Gross, Haberstick and Corley2006; Stallings et al., Reference Stallings, Corley, Hewitt, Krauter, Lessem, Mikulich and Crowley2003).

Adolescent conduct disorder symptoms

At age 17, the participants reported on lifetime symptoms of conduct disorder (CD) by completing the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, Reference Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan and Schwab-Stone2000). Symptoms range from truancy and disobeying parental curfews to initiating fights and committing crimes (e.g., breaking into a car). Overall CD symptom severity was measured as the number of endorsed symptoms (alpha = .67), with scores normed with regard to sex and age on adolescents from several samples (Rhea et al., Reference Rhea, Gross, Haberstick and Corley2006; Stallings et al., Reference Stallings, Corley, Hewitt, Krauter, Lessem, Mikulich and Crowley2003); the scores ranged from 0 to 11 (out of 15 possible).

Age at first sex

Sexual history was self-reported at multiple times from age 17 into early adulthood. Although methods varied across age, all of the participants provided information on the age of their first sexual experience if it had occurred (Bricker et al., Reference Bricker, Stallings, Corley, Wadsworth, Bryan, Timberlake and DeFries2006). Reported ages below 10 and above 29 were considered outliers and excluded from analyses. This paper includes data on this measure from more participants than in our earlier report (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014) because it includes data that were obtained in follow-up assessments beyond age 17 or 21.

Missing data

The details of missing data on measures of puberty and behavioral outcomes in late adolescence are provided in our earlier report (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014)Footnote 1. For this study, we also excluded participants who did not have data on behavior problems at age 7. Analyses conducted separately for boys and girls using p-values of .01 corrected for multiple comparisons showed that those with data were not significantly different from those without data on pubertal timing, but there was one difference on adolescent behavior problems for boys. Specifically, compared with boys with data on childhood behavior problems, those with missing data (and therefore excluded from this study) reported an earlier age at first sex. In sum, data on pubertal timing were missing because insufficient data were available to estimate trajectories, and behavioral data were missing primarily because of the assessment schedule. The amount of missing behavioral data was not significantly associated with pubertal development, and participants who were missing data were not different from those with the requisite data, with the one exception that is considered in the discussion. When participants were missing data, they were excluded only from analyses with the missing variable(s).

Analysis Plan

Multilevel modeling was used to test pubertal timing as both a mediator and as a moderator of the link between childhood and adolescent behavior problems. Separate models were used for boys and girls because statistical power might not be sufficient to detect three-way interactions between sex, puberty, and childhood behavior problems. For all of the analyses, pubertal timing was indexed by age at middle puberty estimated from logistic growth models in both sexes, and, separately, by age at menarche in girls. All of the predictors were grand mean centered within sex prior to analyses. The analyses were conducted in SPSS version 24.

Transformations

Multilevel models assume normality of residuals. There is not an objective test of this assumption, but distributions of study variables can be examined as an approximation (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). The scores on measures of behavior problems are typically skewed, so scores on measures of age 7 and late adolescent behavior problems (CBCL, depression, substance use, conduct disorder symptoms) were subjected to square-root transformations using all of the data from LTS and CAP (which best situates individuals’ scores within their samples). After the transformations, the distributions appeared to be normal. Skewness estimates ranged from .22 to 1.14, and kurtosis estimates ranged from −.29 to 1.24.

Mediation

In order to test a formal model of mediation (whether pubertal timing mediated links between childhood and adolescent behavior problems), it was necessary to determine that childhood behavior problems predicted pubertal timing. This was done with adolescents nested within families in a random intercepts-only model with a variance components error structure. Adoption status was a covariate, childhood behavior problems were predictors, and pubertal timing was the outcome. Full mediation models were not tested because no link between childhood behavior problems and pubertal timing was significant, as discussed in the results section.

Moderation

Separate main effects and interaction models were used to predict each adolescent behavior problem. In the main effects models, adoption status was a covariate, childhood behavior problems and pubertal timing were predictors, and outcomes were adolescent internalizing behavior problems, externalizing behavior problems, depression, substance use, conduct symptoms, and age at sexual initiation. The same variables were included in the interaction models along with the two-way interaction of childhood problems and pubertal timing as an additional predictor. Adolescents were nested within families, and random intercepts-only models were estimated with a variance components error structure. For each outcome, we selected and interpreted the final model (main effects only or interaction) based solely on fit (AIC; Akaike, Reference Akaike1974), which is recommended over null hypothesis testing of the predictor coefficients (Hamaker, van Hattum, Kuiper, & Hoijtinkim, Reference Hamaker, van Hattum, Kuiper, Hoijtink, Hox and Roberts2011).

In our initial report about the links between pubertal timing and adolescent problems (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014), we used correlations in two replicates (subsamples) to address within-family dependences (with each replicate containing one member of each family) and to permit cross-validation of the modeling approach. The current multilevel modeling provides increased power. It is the most efficient for addressing substantive questions, and it allows both siblings from each family to be included in all of the analyses.

Other analyses

Two additional sets of analyses were conducted for completeness and to facilitate the presentation of the results. First, sex differences in pubertal timing and behavior problems were tested. Multilevel random intercepts-only models with a variance components error structure were used, with adolescents nested within families. Sex was the predictor, and all of the other (untransformed) variables of interest were outcomes (in separate models). Standard t-tests are inaccurate because of the inclusion of multiple siblings in a family. Second, correlations among the study variables were computed to examine the links between prepuberty and postpuberty behavior and between pubertal timing and behavior. These zero-order correlations provide standardized comparisons across behavioral outcomes (before accounting for family relatedness in the multilevel models).

Results

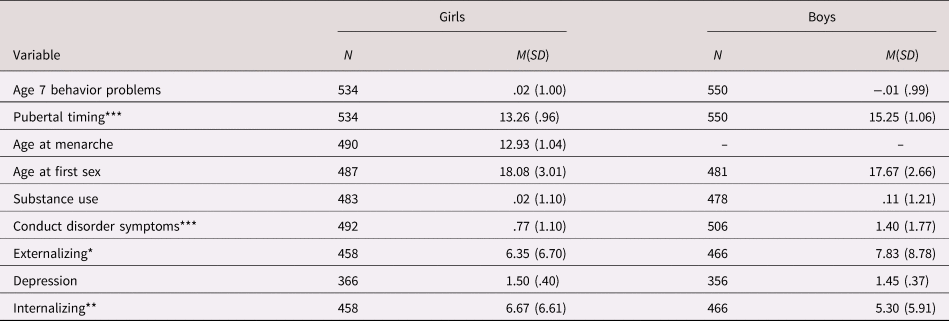

The descriptive data for the behavioral and pubertal variables are presented in Table 1, for boys and for girls. (The scores for behavioral variables are untransformed scores to facilitate comparisons with other studies.) The multilevel models revealed expected sex differences. Girls reported earlier puberty than did boys, and the sexes differed on several behavioral measures. In late adolescence, boys had more externalizing problems and fewer internalizing problems than did girls. In childhood, there were no sex differences in behavior problems, which was likely a function of combining internalizing and externalizing problems.

Table 1. Descriptive data for study variables by sex

Note: Untransformed scores are shown for the behavior variables. Sex differences from multilevel models with adolescents nested within families, a variance components error structure, and random intercepts significant at: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Correlations among all of the study variables are shown in Table 2, with boys above the diagonal and girls below the diagonal. (Scores for the behavioral variables were transformed, as noted in the Method section.) There are several points of note. First, the correlations between child and adolescent behavior problems (average r = .24) demonstrated modest stability of behavior problems, consistent with other work (e.g., Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Hahn and Haynes2010; McElroy et al., Reference McElroy, Shevlin and Murphy2017; Obradović et al., Reference Obradović, Pardini, Long and Loeber2007; Olweus, Reference Olweus1979; Verhulst & van der Ende, Reference Verhulst and van der Ende1995). Second, correlations between pubertal timing and late adolescent/early adult behavior problems showed more and stronger links in girls than in boys, consistent with our previous report (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014) and with other work (e.g., Marceau, Ram, Houts, Grimm, & Susman, Reference Marceau, Ram, Houts, Grimm and Susman2011). Behavioral risk was associated with early puberty. Pubertal timing (age at middle puberty) was positively related to age at first sex and negatively related to substance use and conduct disorder symptoms in both girls and boys and also to externalizing behavior problems in girls. Age at menarche was also negatively associated with internalizing problems in girls. Third, correlations between pubertal timing and childhood behavior problems were generally nonsignificant in either sex. These findings are new.

Table 2. Correlations of behavior problems across age and with pubertal timing

Note: The data for girls are below the diagonal, and the data for boys are above the diagonal. Transformed scores for the behavioral variables were used in the analyses. Correlations, which do not correct for nesting within families, are significant at: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Multilevel models adjusting for family nesting and covarying adoption status provided an explicit test of the relationship between childhood behavior problems and pubertal timing. For girls, neither measure of pubertal timing was predicted by childhood behavior problems (logistic estimate, b = −.12, p = .22; age at menarche, b = −.11, p = .33); for both pubertal measures, adoption status was a significant covariate, b = −.33, p < .001 and b = −.29, p < .05, respectively, and the random intercepts variances were significant (estimates = .52 and .67, both p < .001). For boys, pubertal timing (logistic estimate) was not significantly predicted by childhood behavior problems, b = .01, p = .91. Again, adoption status was a significant covariate, b = −.31, p < .01, and the random intercepts variance was significant (estimate = .35, p < .001). These findings preclude the testing of pubertal timing as a mediator of the link between child and adolescent behavior problems; pubertal timing cannot be a mediator because it was not significantly related to child problems.

The results for the multilevel models examining interactions are shown in Table 3 (girls) and Table 4 (boys). The tables show the results with pubertal timing indexed by estimates from the logistic model. Similar results were found for menarcheal age in girls and are shown in Supplemental Table S1. For each outcome, the results are presented first for the model with main effects only (first column) and then for the full model with main effects and the interaction between child behavior problems and pubertal timing (second column). Included are unstandardized estimates (and standard errors) for each predictor and the relative fit of the model. Because the data were grand mean centered, the intercepts are adjusted means and the predictor coefficients reflect a combination of individual adolescent and family effects.

Table 3. Multilevel model results for girls: Childhood behavior problems, pubertal timing (from logistic growth models), and their interaction predicting late adolescent behavior problems

Note: The preferred model is shaded, and the significant predictors of interest (i.e., main effects and interaction) are in bold: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 4. Multilevel model results for boys: Childhood behavior problems, pubertal timing (from logistic growth models), and their interaction predicting late adolescent behavior problems

Note: The preferred model is shaded, and the significant predictors of interest (i.e., main effects and interaction) are in bold: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The main effects were generally consistent with expectations and with the correlations in Table 2. For both sexes, behavior problems were stable from childhood to adolescence. Behavior at age 7 significantly predicted behavior in adolescence except for depression in girls. Earlier pubertal timing significantly predicted some adolescent outcomes: earlier age at first sex in both sexes, increased substance use in girls, and increased conduct disorder symptoms in boys. Adoption status was a significant predictor of most outcomes for girls (with the exception of depression), but it was not a significant predictor of any outcome for boys, and adopted girls had higher problem scores than did nonadopted girls. Within-family random effects were also significant for most outcomes for both sexes (with the exception of depression in boys), reflecting differences across families.

Interactions between pubertal timing and child behavior problems were not significant for any outcome for girls and for only one outcome (substance use) for boys. As seen in Tables 3 and 4, the model fit was poorer with the interaction included than with main effects only, with that one exception, and the estimated effects for the predictors were very similar under both models. The significant interaction for boys, probed with continuous simple main effects analyses (with values of the pubertal timing moderator at one standard deviation above and below the mean), reflected a significant link between childhood and late adolescence problems in earlier maturers but not in later maturers, b = .24, p < .01 versus b = .03, p = .69.

Discussion

Addressing questions about the nature and causality of the link between pubertal timing and postpuberty adolescent behavior problems, we found that the link is unaffected by childhood prepuberty behavior problems, which independently influenced problems in late adolescence/early adulthood. As expected, adolescent behavior problems were correlated with pubertal timing and with childhood behavior problems. Pubertal timing was hypothesized to mediate the relation, but it was not related to childhood behavior problems, so it could not act as a mediator. Thus, pubertal timing uniquely predicted adolescent problems. Pubertal timing was also hypothesized to moderate the stability in behavior problems such that early timing would lead to more behavior problems specifically in children with a childhood history of problems. There was minimal evidence for such moderation. The only evidence for the moderating effect of pubertal timing was for substance use in boys.

Puberty as a Trigger for Behavior Problems

We studied how links between pubertal timing and late adolescent/early adult behavior problems might be affected by childhood behavior problems. In particular, we tested whether the well-documented psychological risk of early puberty in girls was influenced by prepuberty behavior problems. We also attempted to clarify the psychological significance of pubertal timing in boys.

Puberty as a mediator of the link between childhood and adolescent behavior problems

The novel data provided by this study suggest that early puberty is directly associated with some behavior problems. There has long been evidence that early pubertal timing in girls is associated with increased risk of behavior problems (reviewed in Graber, Reference Graber2013; Mendle, Turkheimer, & Emery, Reference Mendle, Turkheimer and Emery2007; Negriff & Susman, Reference Negriff and Susman2011). There is increasing evidence that variations in pubertal timing matter for boys too, with both early and later maturation conferring risk for behavior problems (reviewed in Graber, Reference Graber2013). Crucially, there have been no previous longitudinal data testing the causal nature of the links. Our data show that pubertal timing is not related to childhood behavior problems in typically developing girls or boys, so the link between early puberty and adolescent behavior problems is not a reflection of prior childhood behavior problems. This does not rule out the possibility that adverse events, such as harsh parenting in early childhood, lead to both child behavior problems (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017) and early puberty (Brown, Cohen, Chen, Smailes, & Johnson, Reference Brown, Cohen, Chen, Smailes and Johnson2004). Our results confirm some previous data in girls (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1991), and they initially appear to be at odds with other data (Mensah et al., Reference Mensah, Bayer, Wake, Carlin, Allen and Patton2013), but the methodological limitations and inconsistent results noted above prevent straightforward interpretation of those data.

The results also indicate that pubertal timing makes a unique contribution to some late adolescent and early adult behavior problems (age at first sex, substance use, conduct disorder symptoms). In those cases, pubertal timing is significantly related to adolescent but not childhood behavior problems, indicating that pubertal timing directly precipitates change in behavior.

Puberty as a moderator of the link between childhood and adolescent behavior problems

Our data also show that pubertal timing effects do not vary by history of behavior problems in girls. In the multilevel models, adolescent behavioral outcomes were not significantly predicted by an interaction between pubertal timing and childhood behavior problems. There are several possible reasons for our failure to confirm an early finding that pubertal timing increases risk of adolescent behavior problems more in girls with childhood problems than in those without (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1991), including the clear separation of pubertal timing and status, earlier age at which childhood behavior problems were assessed, and different methods for measuring puberty and analyzing the data. Nevertheless, the current findings also warrant replication.

In boys, however, there was some suggestion that childhood behavior problems moderated the effect of pubertal timing. In particular, adolescent substance use scores were highest in boys with childhood behavior problems and early puberty. This is similar to others’ results found in girls for overall behavior problems and supports the idea that transitions accentuate individual differences (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1991). The potential importance of childhood behavior problems in qualifying pubertal timing effects on adolescent behavior problems in boys may contribute to the inconsistencies regarding timing effects in boys (Graber, Reference Graber2013). Nevertheless, caution is warranted in interpreting this single significant effect.

Puberty in a Developmental Context

It may be surprising that pubertal timing was not significantly associated with childhood behavior problems. Behavior problems are relatively stable, so problems at two development points might both be expected to correlate with another variable. Nevertheless, there is good evidence from multiple sources that adolescence is a period of psychological change that includes both normative change and change in individuals’ relative positions (Blakemore et al., Reference Blakemore, Burnett and Dahl2010; Icenogle et al., Reference Icenogle, Steinberg, Olino, Shulman, Chein, Alampay and Uribe Tirado2017). Furthermore, early puberty has been hypothesized to result from early childhood adversity, which is also linked to childhood behavior problems (e.g., Ellis, Reference Ellis2004), so it is reasonable to expect a link between early puberty and those problems. However, the link between early adversity and puberty is small and inconsistent, as was discussed above. It is likely that environmental conditions have to be extremely unfavorable before they affect reproductive function, and this situation is not present in our sample. Thus, our results are most applicable to typical children.

Furthermore, we conducted a rigorous test of family influences because we assessed siblings and therefore accounted for within-family variance. This is a major study strength allowing us to account for within-family variability that might otherwise be attributed to associations among variables: A sibling design controls for links among variables (e.g., pubertal timing and psychological characteristics) that reflect shared family variance (e.g., shared genes within a family), and this would not be recognized in a nonsibling design. It is possible that other findings linking childhood problems with early puberty actually reflect within-family differences rather than individual differences. This suggestion is supported by data from father-absent families showing earlier puberty in younger daughters than in their older sisters (Tither & Ellis, Reference Tither and Ellis2008). That our analyses statistically accounted for the similar family experiences of siblings may have resulted in an attenuation of the links between childhood problems and pubertal timing compared with studies of unrelated youth.

Strengths and Limitations

This study extends other work in important ways. The longitudinal data enabled us to show that well-known links between early puberty in girls and adolescent behavior problems do not reflect prepuberty behavior problems, and our findings provide support for early puberty as a direct risk factor for some behavior problems in girls and boys. Part of the story may be different in boys, however, and the results for substance use suggest that more work is needed to clarify the psychological significance of pubertal timing in boys, echoing other calls for that work (Graber, Reference Graber2013).

Several methodological strengths characterized the study. Behavioral data were available at multiple ages that clearly preceded and followed the pubertal transition. This means that behavior was assessed outside of the pubertal period, so it was not affected by any distress that was specifically tied to pubertal events. Adolescent behavior problems were assessed in multiple ways. One measure directly paralleled those used by others to assess childhood behavior problems (the CBCL), and others provided measures of similar constructs. Pubertal timing measures were derived from growth curve models based on yearly assessments over several years. The sample was large enough to detect relatively small effects.

Nevertheless, several methodological limitations need to be considered in interpreting the results. Puberty was assessed by self-report rather than by conducting physical exams or measuring hormones, but a variety of evidence supports the validity of self reports, and it remains the most widely used measure (e.g., Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Hillman, Biro, Ding, Dorn and Susman2012; Shirtcliff, Dahl, & Pollak, Reference Shirtcliff, Dahl and Pollak2009). Furthermore, pubertal development seems to be best described by a logistic growth model (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014; Marceau et al., Reference Marceau, Ram, Houts, Grimm and Susman2011).

The sample was selected in several ways, and it consisted of twins and adoptees and their controls, with limited variability in social class, race, or ethnicity. It is important to replicate this work in samples with broader representation. Furthermore, this study, as does most other work on the origins of behavior problems in childhood and adolescence, focuses on typical children. Although they vary in the characteristics studied, few children experience extreme adversity, very early puberty, or severe psychopathology, so our results can only be generalized to variations within the normal range. It is possible that different findings would emerge in children with large deviations from typical development.

Behavioral measures may not capture all important behavior problems, although the measures are all widely used and psychometrically sound. It would be valuable to use additional measures of prepuberty behavior problems, but it seems unlikely that different effects would be found with other measures. We had more measures of externalizing problems than of internalizing problems. This makes it difficult to interpret the general lack of prediction for depression in late adolescence. It may reflect the lower comparability of childhood parent-reported internalizing problems and adolescent self-reported depression that is associated with the relative difficulty of measuring some problems by parent report. For example, parents are less accurate at reporting internalizing than externalizing problems (Edelbrock, Costello, Dulcan, Conover, & Kala, Reference Edelbrock, Costello, Dulcan, Conover and Kala1986; Seiffge-Krenke & Kollmar, Reference Seiffge-Krenke and Kollmar1998; Sourander, Helstela, & Helenius, Reference Sourander, Helstela and Helenius1999). There were also fewer children who provided data on the adolescent depression measure, so failure to find effects could simply reflect lower power in that case than others.

The assessment of substance use and conduct disorder was not, strictly speaking, limited to the postpubertal period. Substance use is uncommon in this sample in childhood. Conduct disorder symptoms may have occurred in childhood, but any “contamination” of the postpuberty measures by prepuberty behavior would also have increased the chances of finding links between prepuberty behavior and pubertal timing (given that scores on these postpuberty measures were associated with pubertal timing), and we did not find such effects.

Despite the strengths of the inferential analyses noted above, some limitations apply. First, only linear associations were tested, so nonlinear effects may have been missed (e.g., if pubertal timing was a mediator of childhood and late adolescent behavior problems for early and late maturing girls but not for girls with on-time development). It was not practical to test nonlinear associations, given limited literature supporting them and the number of models that would need to be run to examine them. Second, grand mean centering was used because it maintains the relationship between means and variances in multilevel models, and within-family centering is arguably underpowered (due to small family sizes). This procedure blends person- and family-level variations, so the effects are not pure reflections of individual differences in predictors. Third, no analysis can replace systematically missing data. Although this was generally not an issue for the study, boys who did not have data on childhood behavior problems had an earlier age at first sex than did boys with data. Therefore, it is possible that puberty influences the link between early behavior problems and age at first sex but that such effects could not be detected because of missing data from a meaningful set of children. However, this is unlikely because the data for boys with and without childhood behavior problems did not differ in pubertal timing or other adolescent outcome measures and the multilevel modeling results are similar for age at first sex and other outcome measures (that were not related to patterns of missing data for childhood behavior problems). Thus, the single effect of missing data likely arose by chance or was related to the features of the particular measure (e.g., age-related variation in methods used during data collection).

Although our samples contained genetically-related participants, we did not explore genetic influences in this study but, as noted above, took advantage of the sibling design to account for within-family influences (using multilevel modeling, with siblings nested within families). Nevertheless, it is possible that genetic effects are operative here in two ways. First, gene-environment correlations could contribute to our findings. These effects can only be tested in an adoption design that includes data on pubertal timing in biological parents, which are not available in this study. Second, bivariate genetic models could be used to determine whether the same genes affect behavior problems and pubertal timing. But, the lack of significant links between early behavior problems and pubertal timing means that there are no shared genetic influences.

Summary and Conclusions

Longitudinal data from a relatively large sample of boys and girls across the pubertal transition—spanning childhood to early adulthood—indicate that early puberty is a unique risk factor for externalizing behavior problems in middle to late adolescence in girls and generally in boys. Childhood behavior problems have moderate continuity into adolescence, but puberty is directly associated with psychological change in at least some behavioral domains. Findings also highlight the importance of considering adolescent behavior in a developmental context.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941900141X.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally-Ann Rhea for overseeing the data collection and management. We are grateful for the continuing participation of the CAP and LTS subjects who make longitudinal data analyses possible.

The data that are reported here are part of a longitudinal study. Aspects of the data on puberty and adolescent behavior problems have been reported elsewhere (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014; Corley et al., Reference Corley, Beltz, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2015). The overlap is described in the manuscript.

Financial Support

The research reported here was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG046938, HD010333, HD036773, and DA011015.