Introduction

Childhood maltreatment, including neglect, and physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, is a major public health concern experienced by approximately 1 in 4 US children (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck and Hamby2013). Maltreatment is a devastating form of early life stress (ELS) and is associated with increased risk for anxiety and depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), cognitive dysfunction, behavioral disorders, substance abuse, obesity, and inflammation, in both humans and nonhuman primates (NHPs) (Asok, Bernard, Roth, Rosen, & Dozier Reference Asok, Bernard, Roth, Rosen and Dozier2013; Danese & Tan, Reference Danese and Tan2014; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Theall, Gleason, Smyke, De Vivo, Wong and Nelson2012; Drury, Sanchez, & Gonzalez, Reference Drury, Sanchez and Gonzalez2016; Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Flannery, Goff, Humphreys, Telzer and Tottenham2013; Gunnar & Quevedo, Reference Gunnar and Quevedo2007; Howell & Sanchez, Reference Howell and Sanchez2011; McLaughlin et al., Reference Mclaughlin, Sheridan, Tibu, Fox, Zeanah and Nelson2015; Petrullo, Mandalaywala, Parker, Maestripieri, & Higham, Reference Petrullo, Mandalaywala, Parker, Maestripieri and Higham2016; Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Andersen-Wood, Beckett, Bredenkamp, Castle, Groothues and O'Connor1999; Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Alagbe, Felger, Zhang, Graff, Grand and Miller2007; Teicher et al., Reference Teicher, Andersen, Polcari, Anderson, Navalta and Kim2003). However, the developmental consequences of maltreatment vary in complex ways depending on several factors, including the duration and age of exposure (Kaplow & Widom, Reference Kaplow and Widom2007; Kisiel et al., Reference Kisiel, Fehrenbach, Torgersen, Stolbach, McClelland, Griffin and Burkman2014; Spinazzola et al., Reference Spinazzola, Hodgdon, Liang, Ford, Layne, Pynoos and Kisiel2014; Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg, Pynoos, Briggs, Gerrity, Layne, Vivrette and Fairbank2014), form and severity of maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse -which are often co-morbid-), and co-occurrence with other forms of emotional and psychological trauma (Kisiel et al., Reference Kisiel, Fehrenbach, Torgersen, Stolbach, McClelland, Griffin and Burkman2014; Spinazzola et al., Reference Spinazzola, Hodgdon, Liang, Ford, Layne, Pynoos and Kisiel2014). Despite the well-established links between early life adversity and the emergence of psychopathology, the specific neurobiological and developmental mechanisms that translate early adversity into poor health outcomes are not well understood, due in part to the complexities described above.

Alterations in the development of brain networks that control arousal, stress, threat, and emotional responses, particularly the amygdala and its connectivity with prefrontal cortex (PFC), have been proposed as potential neural mediators of the behavioral alterations associated with ELS (Foa & Kozak, Reference Foa and Kozak1986; Teicher, Samson, Anderson, & Ohashi, Reference Teicher, Samson, Anderson and Ohashi2016; VanTieghem & Tottenham, Reference VanTieghem and Tottenham2018; Weber, Reference Weber2008). However, understanding how these neurobiological changes unfold has been challenging. This stems in part from the challenges inherent in conducting prospective, longitudinal studies in children at risk, lack of experimental control, and complex comorbid conditions and environmental confounds (e.g., diet, prenatal exposure to drugs or alcohol, access to health care, socioeconomic status – SES –, etc.). As an alternative, rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) provide an ethologically valid, translational animal model to address the questions raised in human studies through longitudinal, prospective experimental designs that can combine random assignment of infant monkeys to rearing groups at birth with collection of highly dense, longitudinal neurobehavioral sampling from infancy through the juvenile period. Additional strengths of the NHP model for examining the impact of maternal maltreatment include the ability to apply longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, neurodevelopmental speed that progresses about four times faster than humans, and complex social behavior, including mother–infant attachment (Howell & Sanchez, Reference Howell and Sanchez2011; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006; Sanchez, Ladd, & Plotsky, Reference Sanchez, Ladd and Plotsky2001).

The quality of the relationship between a macaque mother and her infant is, as in humans, highly influential of offspring neurobehavioral development (Hinde & Spencer-Booth, Reference Hinde and Spencer-Booth1967). Poor maternal care in the form of infant maltreatment, including abuse and rejection, occurs in NHP species spontaneously and with prevalence rates similar to humans’ (2%–5%) (Brent, Koban, & Ramirez, Reference Brent, Koban and Ramirez2002; Johnson, Kamilaris, Calogero, Gold, & Chrousos, Reference Johnson, Kamilaris, Calogero, Gold and Chrousos1996; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006; Troisi & D'Amato, Reference Troisi and D'Amato1984). Developmental consequences include chronic activation of stress response systems and alterations in socioemotional functioning (Bramlett et al., Reference Bramlett, Morin, Guzman, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2017, Reference Bramlett, Wakeford, Morin, Guzman, Siebert, Howell and Sanchez2018; Brent et al., Reference Brent, Koban and Ramirez2002; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell, Neigh, & Sánchez, Reference Howell, Neigh, Sánchez and D.2016; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Kamilaris, Calogero, Gold and Chrousos1996; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998; Morin, Howell, Meyer, & Sanchez, Reference Morin, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2019; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006; Sanchez, Hearn, Do, Rilling, & Herndon, Reference Sanchez, Hearn, Do, Rilling and Herndon1998; Troisi & D'Amato, Reference Troisi and D'Amato1984). The naturalistic rhesus model of maternal infant maltreatment studied here is operationalized as both early life physical abuse and comorbid maternal rejection, both of which are associated with infant distress (Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri1999; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Newman, Higley, Maestripieri and Sanchez2009; McCormack, Sanchez, Bardi, & Maestripieri, Reference McCormack, Sanchez, Bardi and Maestripieri2006; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006). As in humans, there is transgenerational transmission of maltreatment through the maternal line in macaques (Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri2005; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998). Maltreating mothers reliably maltreat subsequent offspring, suggesting this is a stable maternal trait (Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri2005; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998). Such generational perpetuation of maltreatment parallels findings in humans with a history of childhood adverse care, providing further validation of this NHP model for use in studies of mechanisms underlying developmental outcomes (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Russig, Weiss, Graff, Linder, Michalon and Mansuy2010; Huizinga et al., Reference Huizinga, Haberstick, Smolen, Menard, Young, Corley and Hewitt2006; Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri2005; Tarullo & Gunnar, Reference Tarullo and Gunnar2006).

Macaque infant studies have recapitulated alterations reported in maltreated children (and those with other adverse caregiving experiences), including increased anxiety, emotional reactivity and aggression, impaired impulse control, social deficits, elevated levels of stress hormones indicative of chronic stress exposure, activation of pro-inflammatory pathways, structural alterations in cortico-limbic tracts, and larger amygdala volumes (Bramlett et al., Reference Bramlett, Morin, Guzman, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2017, Reference Bramlett, Wakeford, Morin, Guzman, Siebert, Howell and Sanchez2018; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Grand, McCormack, Shi, LaPrarie, Maestripieri and Sanchez2014; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McCormack, Grand, Sawyer, Zhang, Maestripieri and Sanchez2013; Koch, McCormack, Sanchez, & Maestripieri, Reference Koch, McCormack, Sanchez and Maestripieri2014; Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri1998; McCormack, Newman, Higley, Maestripieri, & Sanchez, Reference McCormack, Newman, Higley, Maestripieri and Sanchez2009; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Sanchez, Bardi and Maestripieri2006; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2019; Petrullo et al., Reference Petrullo, Mandalaywala, Parker, Maestripieri and Higham2016; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006; Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, McCormack, Grand, Fulks, Graff and Maestripieri2010). Of particular interest for this study are the maltreatment effects on the structural integrity of cortico-limbic white matter tracts involved in socioemotional processing and responses during rhesus development previously reported by our group (Howell et al., Reference Howell, McCormack, Grand, Sawyer, Zhang, Maestripieri and Sanchez2013; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019). It is possible that repeated exposure to elevated levels of cortisol due to the adverse experience, among other factors, alters the microstructural organization of white matter tracts through alterations in cellular developmental processes that contribute to these indices of microstructural organization, including myelination, leading to subsequent impacts in functional connectivity (FC) between these regions.

Myelination of axons is a critical cellular process that serves to increase conductance of action potentials, supporting FC between distant brain regions (Fields, Reference Fields2008; Thomason & Thompson, Reference Thomason and Thompson2011; Zatorre, Fields, & Johansen-Berg, Reference Zatorre, Fields and Johansen-Berg2012). Myelination changes drastically during early development (Deoni, Dean, O'Muircheartaigh, Dirks, & Jerskey, Reference Deoni, Dean, O'Muircheartaigh, Dirks and Jerskey2012; Dubois et al., Reference Dubois, Dehaene-Lambertz, Kulikova, Poupon, Huppi and Hertz-Pannier2014; Eluvathingal et al., Reference Eluvathingal, Chugani, Behen, Juhasz, Muzik, Maqbool and Makki2006; Geng et al., Reference Geng, Gouttard, Sharma, Gu, Styner, Lin and Gilmore2012; Govindan, Behen, Helder, Makki, & Chugani, Reference Govindan, Behen, Helder, Makki and Chugani2010; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Behen, Singsoonsud, Veenstra, Wolfe-Christensen, Helder and Chugani2014). This rapid increase in myelination early in life makes this process vulnerable to environmental influences, including adverse care and ELS, and the elevated glucocorticoid levels associated with these experiences (Jauregui-Huerta et al., Reference Jauregui-Huerta, Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo, Gonzalez-Castaneda, Garcia-Estrada, Gonzalez-Perez and Luquin2010; Kumar, Cole, Chiappelli, & de Vellis, Reference Kumar, Cole, Chiappelli and de Vellis1989). In addition, suboptimal maternal care also impacts the ability of the mother to buffer the infant's stress, fear, and arousal responses (Sanchez, McCormack, & Howell, Reference Sanchez, McCormack and Howell2015). These infant's responses are buffered through maternal signals that regulate emotion and stress circuitry (Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017), especially amygdala connections with the hypothalamus and relevant brain stem regions, as well as with PFC, for top-down emotional regulation (Moriceau & Sullivan, Reference Moriceau and Sullivan2006). Thus, maternal care seems to play a critical role in the development of these self-regulatory amygdala circuits as infants reach independence (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Sanchez and Gonzalez2016; Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Telzer, Humphreys, Goff, Shapiro and Tottenham2014; Gunnar & Sullivan, Reference Gunnar and Sullivan2017; Gunnar, Hostinar, Sanchez, Tottenham, & Sullivan, Reference Gunnar, Hostinar, Sanchez, Tottenham and Sullivan2015; Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, McCormack and Howell2015; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015), providing a likely mechanism through which infant maltreatment impacts neural and socioemotional development (Casey, Duhoux, & Malter Cohen, Reference Casey, Duhoux and Malter Cohen2010; Fairbanks, Reference Fairbanks1996; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998). As recently reviewed by VanTieghem and Tottenham (VanTieghem & Tottenham, Reference VanTieghem and Tottenham2018), although different forms of early adversity in children impact amygdala–prefrontal circuits, issues related to the chronicity and complexity of these experiences in humans do not allow differentiation of timing (age) versus duration effects. Thus, the authors called for preclinical studies with animal models of ELS to address these questions using longitudinal designs.

Thus, in this study we used a translational NHP model of infant maltreatment that occurs during an early and discrete developmental phase (the first 3–6 months of life, equivalent to the infant and toddlerhood period in humans) to examine: (a) its longitudinal impact on development of amygdala FC, which may underlie the increased emotional reactivity reported in maltreated animals (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Grand, McCormack, Shi, LaPrarie, Maestripieri and Sanchez2014; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Newman, Higley, Maestripieri and Sanchez2009; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Sanchez, Bardi and Maestripieri2006; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2019; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Wakeford, Howell, Guzman, Siebert, Kazama and Sanchez2018); and (b) whether the prolonged exposure to high cortisol during infancy reported in maltreated animals – measured as high hair cortisol concentrations from birth through 6 months (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017) – predicted alterations in amygdala FC. Although this NHP model of infant maltreatment does not span all adversity that maltreated children experience (e.g., sexual abuse), one of its critical strengths lies in its ability to quantify maltreatment during a known postnatal period, providing frequency, duration, and severity of the adverse experience (i.e., abuse and rejection rates), as well as the concurrent levels of stress it elicits (i.e., cortisol accumulation in hair during the postnatal ELS exposure), all of which are difficult to measure in children. NHP models also provide strong control over environmental variables that are known confounders of behavioral outcomes of ELS in human studies, such as drug use, nutrition, obesity, prenatal stress, SES, and access to medical care. Our experimental design also provides a tool to control for the effects of heritable and prenatal factors on postnatal experience by utilizing cross-fostering and randomized assignment to experimental group at birth (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019), which is not possible in humans.

Thus, we used this translational NHP model of infant maltreatment to examine developmental alterations in amygdala FC longitudinally, from infancy through the juvenile prepubertal period (at 3, 6, 12, 18 months of age) which could underlie behavioral and stress outcomes already reported in these animals (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019). We collected resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) data to examine the developmental impact of maltreatment on amygdala FC (a) with the whole brain, using an exploratory voxel-wise amygdala seed-based FC analysis at the group level; in parallel to (b) specific region of interest (ROI) analysis to examine alterations in amygdala–PFC FC. Based on previous work in both humans and NHPs we predicted that maltreated animals would show decreases in amygdala–PFC FC as they aged. In addition, we examined whether the elevated hair cortisol accumulation from birth through 6 months of age reported in maltreated infants (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017) – a marker of chronic exposure to stress – predicted developmental changes in amygdala FC.

Method

Subjects

These studies included 20 rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) raised by their mothers in large social groups at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center Field Station (YNPRC, Lawrenceville, GA). Animals were studied from birth through to 18 months of age (juvenile, prepubertal age) as part of a larger longitudinal study of developmental consequences of infant maltreatment (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Howell, Guzman, Villongco, Pears, Kim and Sanchez2015; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2019). In this model, maternal infant maltreatment is a spontaneous and stable maternal trait exhibited during the first 3–6 months postpartum that leads to infant distress (Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri1999; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006) and activation of infant stress systems (e.g., the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis) (Bramlett et al., Reference Bramlett, Morin, Guzman, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2017, Reference Bramlett, Wakeford, Morin, Guzman, Siebert, Howell and Sanchez2018; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McCormack, Grand, Sawyer, Zhang, Maestripieri and Sanchez2013). Half of the animals in this study experienced maternal maltreatment, including physical abuse and rejection (maltreated, n = 10; 6 males, 4 females), and the other half received high quality maternal care (control, n = 10; 4 males, 6 females). Subjects lived with their mothers and families in large social groups with a matrilineal social hierarchy consisting of 75–150 adult females, their subadult, juvenile and infant offspring, and 2–3 adult breeder males. Based on this social complexity we were able to use a balanced distribution of social dominance ranks, in addition to sex, across experimental caregiving groups. Infants were assigned from different matrilines and paternities to provide high genetic and social diversity, as previously reported (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2019). Because birth weight is a strong predictor of neurobehavioral development in humans and NHPs (Coe & Shirtcliff, Reference Coe and Shirtcliff2004; Vohr et al., Reference Vohr, Wright, Dusick, Mele, Verter, Steichen and Kaplan2000), we only studied infants with ≥450 gm birth weight, which is a safe veterinary clinical cut off to rule out prematurity in rhesus monkeys. Furthermore, while 7 of the animals were raised by their biological mothers (4 maltreated: 3 males, 1 female; 3 control: 1 male, 2 females), the other 13 were randomly assigned at birth to be cross-fostered (CF) to either mothers with a history of nurturing maternal care or to maltreating foster mothers (7 control CF: 3 males, 4 females; 6 maltreated CF: 3 males, 3 females), in an effort to counter-balance the potential confounding effect of biological factors (e.g., heritability, prenatal confounders) on the effect of postnatal caregiving experience, following published protocols by our group (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2019) and previous methods (Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri2005). Social groups were housed in outdoor compounds, with access to climate-controlled indoor areas. As well as a standard, high fiber, and low-fat monkey chow diet (Purina Mills Int., Lab Diets, St. Louis, MO), seasonal fruits and vegetables were provided twice dail, in addition to enrichment items. Water was available ad libitum. All procedures were in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and approved by the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Behavioral characterization of maternal care

The infant rhesus maltreatment model and the methods used for selection of potential mothers and behavioral characterization of competent maternal care (control care) versus infant maltreatment have been described in previous publications (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Ahn, Shi, Godfrey, Hu, Zhu and Sanchez2019; Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri1998; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Sanchez, Bardi and Maestripieri2006; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Newman, Higley, Maestripieri and Sanchez2009; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2019). Briefly, because maltreating mothers consistently maltreat subsequent offspring –suggesting this is a stable maternal trait (Maestripieri, Reference Maestripieri2005; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998) – we identified potential multiparous control and maltreating mothers for assignment to experimental group based on maternal care quality exhibited with prior offspring. Following birth (and cross-fostering where applicable) we performed focal observations of maternal care across the first three postnatal months to substantiate and quantify maltreatment (rates of abuse and rejection) and competent maternal care (cradling, grooming, etc.) towards biological or fostered infants. These were 30 min long focal observations of mother–infant interactions performed on separate days (5 days/week during month 1, 2 days/week during month 2, and 1 day/week during month 3) for a total of 16 hr/mother–infant pair. This observation protocol is optimal to document early maternal care in this species, given that physical abuse rates are the highest during the first month and decline by the third month, after which it is rarely observed (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Sanchez, Bardi and Maestripieri2006). Observations were performed between 7:00 and 11:00 a.m., when monkeys are most active. Behavioral observations were collected by experienced coders (interobserver reliability >90% agreement, Cohen k > 0.8). Competent maternal care is defined as species-typical behaviors, such as nursing, cradling, grooming, ventral contact, and protection (retrieve from potential danger, restrain) of the infant. In contrast, maltreatment is aberrant, defined as the co-morbid occurrence of physical abuse (operationalized as violent behaviors directed towards the infant that cause pain and distress, including dragging, crushing, throwing, etc.) and early infant rejection (i.e., prevention of ventral contact and pushing the infant away during the first weeks of life). Both abuse and rejection cause high levels of infant distress (e.g., scream vocalizations, tantrums) and elevations in stress hormones (Bramlett et al., Reference Bramlett, Morin, Guzman, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2017, Reference Bramlett, Wakeford, Morin, Guzman, Siebert, Howell and Sanchez2018; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McCormack, Grand, Sawyer, Zhang, Maestripieri and Sanchez2013; Maestripieri & Carroll, Reference Maestripieri and Carroll1998; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Sanchez, Bardi and Maestripieri2006; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006). Control foster mothers in this study exhibited competent maternal care (e.g., high maternal sensitivity, infant protection, and responsivity) (McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Howell, Guzman, Villongco, Pears, Kim and Sanchez2015) and did not exhibit maltreating behaviors (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017).

MRI scanning session

MRI images were acquired longitudinally, at 3 and 6 months (infancy), and at 12 and 18 months (juvenile period) of age using a 3T Siemens Magnetom Tim Trio MRI scanner (Siemens Med. Sol., Malvern, PA, USA), and an eight-channel phase array knee coil (YNPRC Imaging Center). Subjects were transported with their mothers from the YNPRC Field Station to the YNPRC Main Station on the main Emory campus in Atlanta on the day before or early in the morning of the day of the scan. All MRI data were acquired during a single scanning session, with the animals scanned supine in the same orientation and the head immobilized in a custom-made head holder with ear bars and a mouthpiece to minimize motion. A vitamin E capsule was placed on the right temple to mark the right side of the brain.

Following initial induction of light anesthesia with telazol (3.9 ± 0.83 mg/kg BW, i.m. mean ± standard deviation) and intubation, scans were collected under the lowest possible level of isoflurane anesthesia (1.0 ± 0.1%, inhalation; mean ± standard deviation) to minimize its reported dampening effect on blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD signal) (Hutchison, Womelsdorf, Gati, Everling, & Menon, Reference Hutchison, Womelsdorf, Gati, Everling and Menon2013; Li, Patel, Auerbach, & Zhang, Reference Li, Patel, Auerbach and Zhang2013; Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Grayson, Woodall, Grant, Kroenke and Fair2014b; Tang & Ramani, Reference Tang and Ramani2016; Vincent et al., Reference Vincent, Patel, Fox, Snyder, Baker, Van Essen and Raichle2007). MRI images were acquired and processed following approaches optimized by our group for studies of macaque neurodevelopment (Kovacs-Balint et al., Reference Kovacs-Balint, Feczko, Pincus, Earl, Miranda-Dominguez, Howell and Sanchez2018; Mavigner et al., Reference Mavigner, Raper, Kovacs-Balint, Gumber, O'Neal, Bhaumik and Chahroudi2018) and protocols developed and widely used for macaques (Grayson et al., Reference Grayson, Bliss-Moreau, Machado, Bennett, Shen, Grant and Amaral2016; Hutchison et al., Reference Hutchison, Womelsdorf, Gati, Leung, Menon and Everling2012; Li et al., Reference Li, Patel, Auerbach and Zhang2013; Margulies et al., Reference Margulies, Vincent, Kelly, Lohmann, Uddin, Biswal and Petrides2009; Sallet et al., Reference Sallet, Mars, Noonan, Andersson, O'Reilly, Jbabdi and Rushworth2011; Vincent et al., Reference Vincent, Patel, Fox, Snyder, Baker, Van Essen and Raichle2007). Our isoflurane levels are even lower than previously used in macaque studies of sensory, motor, visual, and cognitive-task related systems that reported patterns of coherent BOLD fluctuations similar to those observed in awake behaving monkeys (Vincent et al., Reference Vincent, Patel, Fox, Snyder, Baker, Van Essen and Raichle2007; Hutchison et al., Reference Hutchison, Womelsdorf, Gati, Everling and Menon2013; Li et al., Reference Li, Patel, Auerbach and Zhang2013; Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Grayson, Woodall, Grant, Kroenke and Fair2014b; Tang & Ramani, Reference Tang and Ramani2016). Ideally, these animals would have been scanned awake, but training socially housed infants and juveniles for awake scanning is not currently feasible. Each animal was fitted with an oximeter, rectal thermometer, and blood pressure and heart rate monitor for physiological monitoring during the scans. An intravenous catheter was placed in the saphenous vein to administer dextrose/NaCl (0.45%) to maintain hydration. Each animal was placed on an MRI-compatible heating pad to maintain normal body temperature and was monitored by veterinary staff throughout the scan procedures. Infants were immediately returned to their mothers after full recovery from anesthesia, and mother–infant/juvenile pairs were returned to their social groups the day after the scan.

Structural MRI acquisition

Structural images were acquired for registration of functional data to the age-specific atlas spaces. High-resolution structural MRI images (T1-weighted) were collected with a 3D magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (3D-MPRAGE) parallel image sequence (TR/TE = 3000/3.31 ms, 116 mm FOV, voxel size: 0.6 mm3, 6 averages, GRAPPA, R = 2). T2-weighted scans were also collected in the same direction as the T1 during the same scanning session (TR/TE = 2500/84 ms, 128 mm FOV, voxel size: 0.7 × 0.7 × 2.0 mm, 1 average, GRAPPA, R = 2) to aid with registration and delineation of anatomical borders.

rsfMRI acquisition

Two 15-min rsfMRI T2*-weighted scans with a gradient-echo echoplanar imaging (EPI) sequence (400 volumes, TR/TE = 2060/25 msec, voxel size: 1.5 mm3 isotropic) were collected to measure temporal changes in regional BOLD signals. An additional short field map scan was also acquired for unwarping distortions in the EPI scans. The first three volumes were removed from each EPI scan to ensure scan environment stabilization, resulting in a total of 794 concatenated volumes per 15-min scan. These protocols and scan sequences have been optimized at the YNPRC for longitudinal infant macaque imaging (Kovacs-Balint et al., Reference Kovacs-Balint, Feczko, Pincus, Earl, Miranda-Dominguez, Howell and Sanchez2018; Mavigner et al., Reference Mavigner, Raper, Kovacs-Balint, Gumber, O'Neal, Bhaumik and Chahroudi2018; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Budin, Yapuncich, Rumple, Young, Payne and Styner2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Jiang, Zhang, Howell, Zhao, Zhang and Liu2017).

rsfMRI data preprocessing

Data pre-processing was done using the FMRIB Software Library (FSL, Oxford, UK; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Jenkinson, Woolrich, Beckmann, Behrens, Johansen-Berg and Matthews2004; Woolrich et al., Reference Woolrich, Jbabdi, Patenaude, Chappell, Makni, Behrens and Smith2009), 4dfp, and an in-house pipeline built using Nipype (Gorgolewski et al., Reference Gorgolewski, Burns, Madison, Clark, Halchenko, Waskom and Ghosh2011), modified based on published functional MRI (fMRI) analysis methods (Fair et al., Reference Fair, Dosenbach, Church, Cohen, Brahmbhatt, Miezin and Schlaggar2007; Fair et al., Reference Fair, Cohen, Power, Dosenbach, Church, Miezin and Petersen2009; Fair et al., Reference Fair, Nigg, Iyer, Bathula, Mills, Dosenbach and Milham2012; Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Shafran, Grayson, Gates, Nigg and Fair2013; Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Carpenter, Grant, Kroenke, Nigg and Fair2014a), and optimized for macaques (Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Grayson, Woodall, Grant, Kroenke and Fair2014b), including resting state fMRI (rsfMRI) studies in infant rhesus by our group (Kovacs-Balint et al., Reference Kovacs-Balint, Feczko, Pincus, Earl, Miranda-Dominguez, Howell and Sanchez2018; Mavigner et al., Reference Mavigner, Raper, Kovacs-Balint, Gumber, O'Neal, Bhaumik and Chahroudi2018). This procedure consisted of (a) quantification and correction of dynamic field map changes, (b) slice-time correction of intensity differences as a result of interleaved slice image acquisition, (c) combined resampling of: within-run rigid-body motion correction, registration of the EPI to the subject's own averaged T1-weighted structural image, and registration of the T1 to age-specific T1-weighted rhesus infant and juvenile brain structural MRI atlases developed by our group (publicly available at: https://www.nitrc.org/projects/macaque_atlas), using nonlinear registration methods in FSL (FNIRT), (d) BOLD signal normalization to mode of 1000, to scale BOLD values across participants at an acceptable range, (e) BOLD signal detrending, (f) regression of rigid body head motion (six directions), global brain signal, BOLD signal of the ventricles and white matter (derived from manually drawn masks), and first-order derivatives of these signals, and (g) low-pass (f < 0.1 Hz) temporal filter (second order Butterworth filter) (Fair et al., Reference Fair, Dosenbach, Church, Cohen, Brahmbhatt, Miezin and Schlaggar2007; Fair et al., Reference Fair, Cohen, Power, Dosenbach, Church, Miezin and Petersen2009; Fair et al., Reference Fair, Nigg, Iyer, Bathula, Mills, Dosenbach and Milham2012; Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Grayson, Woodall, Grant, Kroenke and Fair2014b).

The infant and juvenile atlases were previously registered to the 112RM-SL atlas in F99 space (McLaren et al., 2009, 2010; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Budin, Yapuncich, Rumple, Young, Payne and Styner2017) as shown in (Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Grayson, Woodall, Grant, Kroenke and Fair2014b) and were templates made using scans acquired longitudinally at 3, 6, and 12 months of age on 40 infant rhesus monkeys from the YNPRC social colony, balanced by sex and social rank. Based on best match of neuroanatomical characteristics, we registered the earliest scan age (3 months) to the 3 months atlas, the 6 months scans to the 6 months atlas and the later ages (12, 18 months) to the 12 months rhesus atlas. All the atlases were transformed to conform to the T1-weighted 112RM-SL atlas image in F99 space, following previously described protocols (Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Grayson, Woodall, Grant, Kroenke and Fair2014b) and allowing the EPI images to be transformed into F99 space in one interpolation step.

Global signal regression (GSR) was performed based on previous literature showing the importance of removing systematic artifacts, including global artifacts that arise as a consequence of movement, respiration, and other physiological noise (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Kandala, Nolan, Laumann, Power, Adeyemo and Barch2016; Ciric et al., Reference Ciric, Wolf, Power, Roalf, Baum, Ruparel and Satterthwaite2017; Nalci, Rao, & Liu, Reference Nalci, Rao and Liu2017; Power, Laumann, Plitt, Martin, & Petersen, Reference Power, Laumann, Plitt, Martin and Petersen2017; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Cheung, Kelly, Colcombe, Craddock, Di Martino and Milham2013), including macaque rsfMRI FC studies (Grayson et al., Reference Grayson, Bliss-Moreau, Machado, Bennett, Shen, Grant and Amaral2016; Miranda-Dominguez et al., Reference Miranda-Dominguez, Mills, Grayson, Woodall, Grant, Kroenke and Fair2014b). Without doing so, spurious artifacts would become problematic, especially in longitudinal studies of FC throughout development. Notwithstanding the above defense of GSR, we acknowledge that controversy regarding this method persists (Murphy & Fox, Reference Murphy and Fox2017). Because of this, we previously compared infant macaque FC with and without GSR and obtained similar results throughout development (Kovacs-Balint et al., Reference Kovacs-Balint, Feczko, Pincus, Earl, Miranda-Dominguez, Howell and Sanchez2018), including the current dataset, in which similar effects of maltreatment were detected on amygdala FC with and without GSR (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Howell, Reding, Guzman, Feczko, Earl and Shi2015 ).

Motion artifacts were further minimized by removing frames displaced more than 0.2 mm (Power et al., Reference Power, Mitra, Laumann, Snyder, Schlaggar and Petersen2014; Power, Barnes, Snyder, Schlaggar, & Petersen, Reference Power, Barnes, Snyder, Schlaggar and Petersen2012). Following preprocessing, data quality was further inspected, and several scans were removed from the analysis due to a significant image acquisition artifact (nonbiological high intensity signal band passing axially through the temporal lobe). Therefore, of the 20 animals included in the study, 17 scans were included in the analyses at 3 months (2 were removed due to the image artifact, and 1 scan was not usable), all 20 scans were included at 6 months, 13 scans were included at 12 months (4 were removed due to image artifact, 1 scan was not usable and 2 animals could not be scanned due to sickness), and 8 scans at 18 months (1 scan was removed due to image artifact, 1 scan was not usable and the other 10 animals could not be scanned because they were no longer assigned to the study).

Definition of amygdala and PFC ROIs

ROIs were selected from published anatomical parcellations (Lewis & Van Essen, Reference Lewis and Van Essen2000; Markov et al., Reference Markov, Misery, Falchier, Lamy, Vezoli, Quilodran and Knoblauch2011; Paxinos, Huang, & Toga, Reference Paxinos, Huang and Toga2000), defined using macaque atlases (Logothetis & Saleem, Reference Logothetis and Saleem2012; Schmahmann & Pandya, Reference Schmahmann and Pandya2006), and mapped onto the 3, 6, and 12 months UNC (University of North Carolina)–Emory rhesus infant atlases (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Budin, Yapuncich, Rumple, Young, Payne and Styner2017) registered to the F99 space as described above. The amygdala ROI was drawn by neuroanatomists using cytoarchitectonic maps in the UNC–Wisconsin adolescent atlas (Styner et al., Reference Styner, Knickmeyer, Joshi, Coe, Short and Gilmore2007), and propagated to the UNC–Emory rhesus 3, 6, and 12 months infant atlases in F99 space using deformable registration via ANTS (for details see Shi et al., Reference Shi, Budin, Yapuncich, Rumple, Young, Payne and Styner2017). The amygdala ROI included all amygdaloid nuclei, excluding perirhinal cortex. PFC ROIs were manually edited in each age-appropriate atlas according to established anatomical landmarks (Logothetis & Saleem, Reference Logothetis and Saleem2012; Paxinos et al., Reference Paxinos, Huang and Toga2000) and under guidance of an expert on amygdala and PFC developmental neuroanatomy (Jocelyne Bachevalier, Emory University), before removing voxels that covered regions where at least one animal showed signal dropout, determined as the mean intensity of each subjects’ BOLD signal intensity across the whole-brain mask minus two standard deviations. PFC ROI subregions included the dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC) (Brodmann areas [BA] 9 & 46), medial PFC (mPFC) (BA 25 & 32), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) (BA 11 & 13), and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (BA 24).

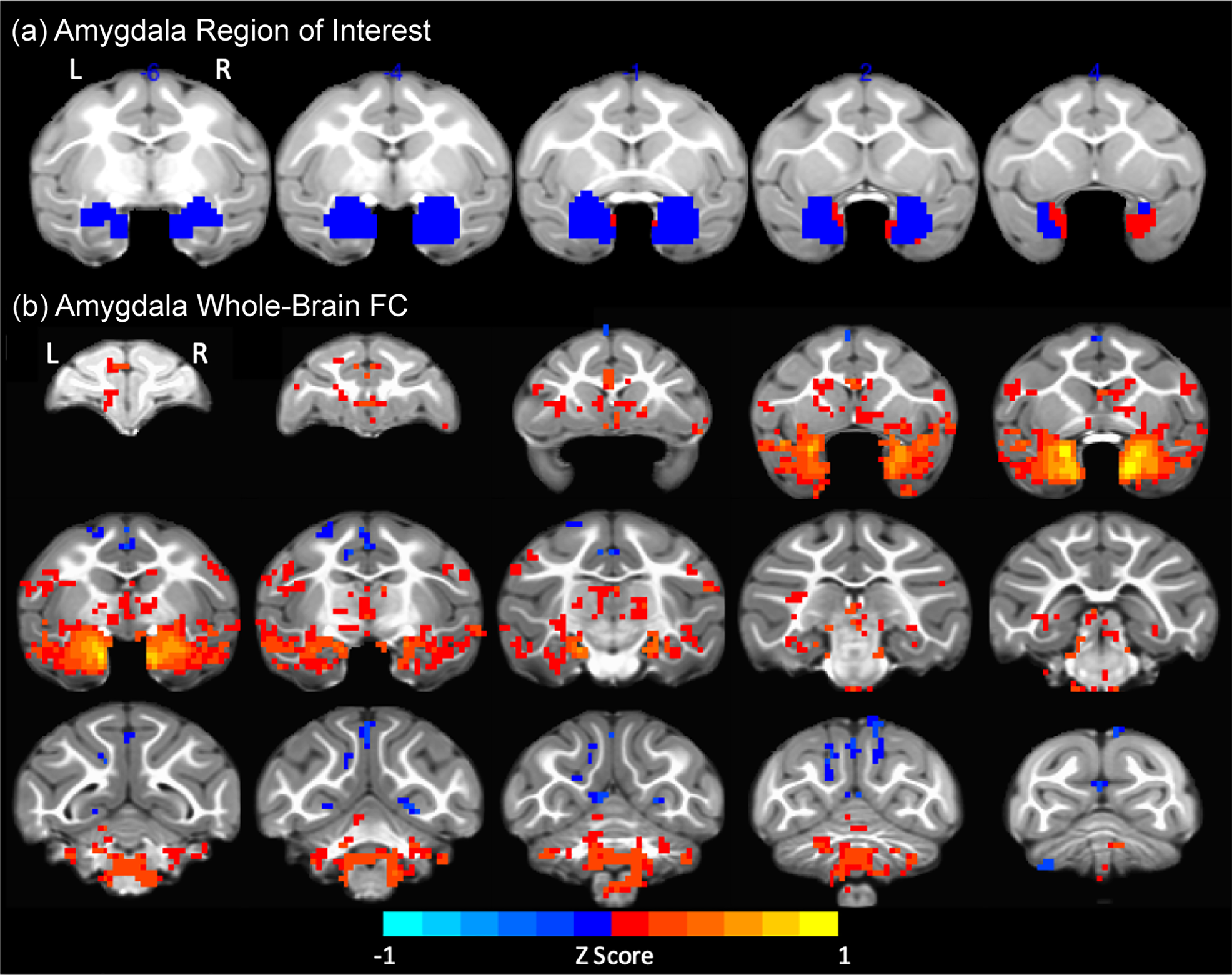

Whole brain voxel-wise amygdala FC analysis

Seed-based maps of right and left amygdala FC with other voxels in the brain were created for each subject across all ages. A secondary seed-based analysis was limited to voxels which were significantly correlated with amygdala activity (false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected q = 0.05, cluster size ≥ 10 contiguous voxels), using data-reduction methods similar to those in previous macaque amygdala seed-based voxel-wise analyses (Grayson et al., Reference Grayson, Bliss-Moreau, Machado, Bennett, Shen, Grant and Amaral2016; Reding et al., Reference Reding, Grayson, Miranda-Dominguez, Ray, Wilson, Toufexis and Sanchez2020). These FC maps were included in a mixed linear model (MLM), AFNI's (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages) 3dLME (linear mixed-effects) statistical model, described in more detail in the Statistical Analysis section below. Statistically significant clusters after multiple comparisons correction using FDR were displayed on the infant atlases (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Budin, Yapuncich, Rumple, Young, Payne and Styner2017), and their anatomical localization identified with established combined stereotaxic/MRI rhesus macaque brain atlases (Logothetis & Saleem, Reference Logothetis and Saleem2012; Paxinos et al., Reference Paxinos, Huang and Toga2000); see Figure 2b.

Amygdala-PFC FC: ROI–ROI analyses

ROIs were selected, defined, and mapped to infant atlases as described above. BOLD time series were then parcellated and averaged across all voxels within each ROI, and averaged across the time course. Pearson correlations were calculated between amygdala and subregions of the PFC (dlPFC - BA 9, BA 46; mPFC -=– BA 25, BA 32; ACC – BA 24; OFC – BA 11, BA 13) for each age and Fisher Z-transformed to stabilize variance.

Postnatal hair cortisol measures

At birth, one square inch of hair was shaved from the infant's head just above the foramen magnum (nuccal area) in a subset of subjects (control: 3 male, 2 female; maltreated: 3 male, 2 female). Hair that had grown in that area was shaved again at 6 months of age. Hair samples collected at 6 months were assayed to measure cortisol accumulated in the growing hair shafts from birth through 6 months of age as a measure of HPA axis activity, which was higher in maltreated than control animals (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017). Hair samples were processed and assayed using previously described protocols (Meyer, Novak, Hamel, & Rosenberg, Reference Meyer, Novak, Hamel and Rosenberg2014). Hair was first weighed and washed in isopropanol to remove external contamination, then ground to powder and extracted with methanol overnight. After the methanol evaporated, the resulting residue was re-dissolved in assay buffer, and cortisol was measured using the Salimetrics (Carlsbad, CA) enzyme immunoassay kit (cat. # 1-3002). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <10%.

Statistical Analyses

Infancy–juvenile period longitudinal amygdala–PFC FC: ROI–ROI analyses

Linear mixed models (LMM) were used to assess the effects of age (3, 6, 12, 18 months), caregiving group (control, maltreated), sex (male, female), and hemisphere (right, left), on PFC–amygdala FC from infancy to the juvenile (prepubertal) period. The model was also run excluding sex for comparison with the amygdala-seed based voxel-wise LMM models. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Student t tests when significant caregiving group interaction effects were detected in the LMM, and Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons. Linear regression was used to test whether postnatal cortisol exposure was predictive of PFC–amygdala FC when significant caregiving group effects were detected in the LMM. Statistical significance level was set at p < .05.

Longitudinal whole brain voxel-wise amygdala FC

The seed-based maps of amygdala FC with other voxels in the brain were included in a MLM, AFNI's 3dLME group analysis program to examine the effects of age (3, 6, 12, 18 months), caregiving group (control, maltreated) and hemisphere (right, left) on amygdala FC. Statistically significant voxel clusters following multiple comparison corrections using FDR (FDR-corrected q = 0.05, cluster size ≥ 2 voxels) are shown in Figure 2b. Sex was not included as a factor in these MLM models due to lack of power.

Post hoc Student t tests were conducted on clusters with significant main group or group by age interaction effects, using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. We then performed regression analyses to test whether early postnatal cortisol exposure were predictive of amygdala FC in clusters with significant group or group by age post hoc effects. FC in these clusters (Fisher's Z-transformed) was normally distributed. Statistical significance level was set at p < .05.

Results

ROI–ROI FC

Left amygdala-right amygdala FC

A significant main effect of group (F (1,20.4) = 4.4, p = .0496) was detected with maltreated animals showing higher FC than controls across age (Figure 1a). Although a trend toward a main effect of age (F (3,20.0) = 2.7, p = .0764) was found, no other significant main or interaction effects were detected.

Figure 1. Development of amygdala–prefrontal cortex (PFC) functional connectivity (FC) from infancy through the juvenile period (3–18 months of age): region of interest (ROI)–ROI analysis. (a) Amygdala–amygdala and amygdala–PFC subregions FC across four ages are plotted separately by group, PFC subregion, respective Brodmann Areas (BA) and hemisphere: macaque amygdala and PFC coronal diagrams showing ROIs (adapted from Barbas, Saha, Rempel-Clower, & Ghashghaei, Reference Barbas, Saha, Rempel-Clower and Ghashghaei2003) – top, left; amygdala–amygdala FC was higher in maltreated than control animals across ages (#: (F (1,20.4) = 4.4, p = .0496) –top, right, whereas amygdala FC with BA13 was stronger in control than maltreated animals (#: F (1,60.0) = 5.0, p = .0289) –third row from top-; an age by group by hemisphere effect was detected for amygdala–BA9 FC (F (3,36.7) = 4.3, p = .0106), with positive FC in the left and negative in the right hemisphere of controls, and opposite coupling in maltreated animals at 12 months (*: t(1,6) = 4.2, p = .0056) –fourth row from top. (b) Significant interaction effects of: group by sex on amygdala–medial PFC (mPFC) FC (BA 25; #: F (1,48.3) = 5.3, p = .0258), with higher FC in control than maltreated females, though post hoc tests did not confirm significant differences – first from left; group by sex by hemisphere on amygdala–BA 25 FC (F (1,48.3) = 6.1, p = .0169) with higher positive FC in control than maltreated females in the right hemisphere (*: t(1, 12.0) = 2.3, p = .0431) –second from left-; and age by group by sex for amygdala–ACC (BA 24) FC (F (2,42.3) = 3.7, p = .0337), showing different coupling between female groups at 12 months (*: t(1,3.9) = 3.2, p = .0334), with positive FC in control, and negative FC in maltreated females –right. ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; dlPFC: dorsolateral PFC; mPFC: medial PFC; OFC: orbitofrontal cortex. Plots represent mean±standard error of the mean (SEM).

When sex was excluded from the LMM model no main or interaction effects were detected.

Amygdala-mPFC FC

Amygdala-BA 25 FC

A significant group by sex interaction effect (F (1,48.3) = 5.3, p = .0258) with higher FC in control than maltreated females was detected (Figure 1b); however, post hoc t tests did not confirm significant differences between means. A group by sex by hemisphere interaction (F (1,48.3) = 6.1, p = .0169) was also found, with higher positive FC in control than maltreated females in the right hemisphere (t (1, 12.0) = 2.3, p = .0431, η2 = 0.187; Figure 1b). No other significant main or interaction effects were detected.

When sex was excluded from the LMM model, no main or interaction effects were detected.

Amygdala-BA 32 FC

A significant main effect of age (F (3,36.5) = 3.0, p = .0426) was detected, with the highest (positive) FC observed at 3 months, and decreasing through 18 months, although remaining positive (Figure 1a). A significant sex by hemisphere interaction effect was also found (F (1,56.3) = 4.4, p = .0401) with females showing higher FC than males in the right hemisphere; however, post hoc t tests did not confirm significant differences between means. No other significant main or interaction effects were detected.

When sex was excluded from the LMM model, the main effect of age remained significant (F (3,45.2) = 3.1, p = .0363).

Amygdala-ACC (BA 24) FC

A significant age by group by sex interaction effect (F (2,42.3) = 3.7, p = .0337) was detected in amygdala–ACC FC (Figure 1b). Post hoc t tests, showed significantly different functional coupling between female groups at 12 months of age (t (1,3.9) = 3.2, p = .0334, η2 = 0.535), with positive FC in control females but negative FC in maltreated females. No other significant main or interaction effects were detected.

When sex was excluded from the LMM model no main or interaction effects were detected.

Amygdala–OFC FC

Amygdala–BA 11 FC

Apart from a trend effect of hemisphere (F (1,42.6) = 3.2, p = .0820) with higher positive FC seen in the right than left hemisphere (Figure 1a), no significant main or interaction effects were detected.

When sex was excluded from the LMM model, a main effect of hemisphere was detected (F (1,90.8) = 5.4, p = .0225).

Amygdala–BA 13 FC

A main effect of group (F (1,60.0) = 5.0, p = .0289) was detected, with higher positive FC in control than maltreated animals (Figure 1a), and a trend for Group×Age (F (3,41.3) = 2.7, p = .0573). Post hoc t tests revealed significant differences at 3 months, with controls showing stronger (positive) FC than maltreated animals, who showed either uncoupling or negative FC (t (1,32) = 3.83, p = .001, η2 = 0.298). No other significant main or interaction effects were detected.

When sex was excluded from the LMM model, the main effect of group remained (F (1,77.9) = 6.7, p = .0117), a significant main effect of age emerged (F (3,50.5) = 3.5, p = .0216) and the group by age interaction effect remained (F (3,47.5) = 2.8, p = .0474).

Amygdala–dlPFC FC

Amygdala–BA 9 FC

A significant age by group by hemisphere interaction effect (F (3,36.7) = 4.3, p = .0106) was detected. Post hoc tests found significant differences between groups at 12 months, with positive FC in the left and negative in the right hemisphere of controls, whereas maltreated animals had negative FC in the left and positive in the right hemisphere (t(1,6) = 4.2, p = .0056, η2 = 0.50; Figure 1a). A significant age by sex by hemisphere interaction effect (F (3,36.4) = 3.8, p = .0189) and trend for group by sex (F (1,44.7) = 3.6, p = .0654) were also detected. No other significant main or interaction effects were found.

When sex was excluded from the LMM model, a main group effect emerged (F (1,42.2) = 4.8, p = .0340), with controls showing weaker positive FC than maltreated animals.

Amygdala–BA 46 FC

A main effect of sex (F (1,74.5) = 4.8, p = .0318) was found, with higher positive FC in females than males (data not shown in Figure 1). No other significant main or interaction effects were detected.

When sex was excluded from the LMM model there was a trend for an age by group interaction effect (F (3,47.7) = 4.8, p = .0842).

Whole-brain voxel-wise amygdala FC

Amygdala seed-based FC maps were FDR-corrected (q = 0.05, t > 2.630, p < .0085), and clusters with ten or more contiguous voxels (faces touching) were selected to increase stringency for the secondary analyses (Figure 2b). The amygdala FC maps obtained in this infant and juvenile macaque dataset during development closely resemble those published in adult macaques (Amaral & Price, Reference Amaral and Price1984; Grayson et al., Reference Grayson, Bliss-Moreau, Machado, Bennett, Shen, Grant and Amaral2016; Reding et al., Reference Reding, Grayson, Miranda-Dominguez, Ray, Wilson, Toufexis and Sanchez2020; Russchen, Bakst, Amaral, & Price, Reference Russchen, Bakst, Amaral and Price1985). Thus, significant positive amygdala FC – red to yellow voxels in Figure 2b – was found throughout regions in the temporal lobe, including bilateral amygdala and hippocampal regions, and PFC subregions and ACC (consistent with the mostly positive AMY–PFC/ACC FC detected in the ROI–ROI analysis; Figure 1), subcortical regions (e.g., thalamus, caudate, and ventral striatum, including nucleus accumbens, and hypothalamus), cerebellum, and brainstem areas. Negative amygdala FC was found dispersed in the posterior cingulate cortex and cerebellum, as well as throughout motor, posterior parietal, and occipital (visual) cortices (blue voxels in Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Amygdala functional connectivity (FC) with the rest of the brain. (a) Amygdala region of interest (ROI) in blue, after removing voxels with blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal dropout (in red). (b) Amygdala FC maps obtained from the seed-based whole-brain analysis collapsed across group, age and hemisphere (red to yellow voxels: positive FC; blue voxels: negative FC). L: left; R: right.

Secondary MLM (AFNI 3dLME) analysis restricted to these significant clusters of contiguous voxels selected from the amygdala FC maps showed a main effect of age that primarily reflected increased positive FC with age between amygdalae and bilateral corticomedial/medial amygdaloid nucleus, right anterior amygdaloid area; cortical regions, such as bilateral superior temporal sulcus (STS: TE anteroventral, TE anterodorsal, temporo–parieto–occipital junction), left parainsular cortex, left visual cortex (V1), left posterior cingulate, left perirhinal cortex, left entorhinal cortex, right periamygdaloid cortex and bilateral ventral/dorsal tegmental area, bilateral dorsal raphe nuclei, left lateral parabrachial nucleus, bilateral cerebellum, bilateral laterodorsal/lateroventral amygdala, left trigeminus, left abducens/facial nucleus/pontine reticular formation, and left pre/pro/parasubiculum (hippocampus) (FDR-corrected q = 0.05, t > 5.242, p < .0023, cluster threshold ≥ 2 voxels; Figures 3 & 4).

Figure 3. Voxel-wise analysis of developmental changes in amygdala FC with the rest of the brain (3–18 months of age). Amygdala functional connectivity (FC) obtained from the seed-based, whole-brain analysis. Clusters with significant main effect of age, false discovery rate (FDR) corrected (q = 0.05): 1 – Parainsular cortex, 2&3 – Perirhinal cortex,4 – Corticomedial/medial amygdaloid nucleus, 5 – Anterior amygdaloid area, 6 – Laterodorsal/lateroventral amygdala, 7 – Laterodorsal amygdala, 8 – Perirhinal cortex, 9 – TPO/STS, 10 – TEa, STS ventral bank, 11 – Teav, Tead, 12 – Presubiculum/Prosubiculum, 13 – Posterior Cingulate, 14 – Parasubiculum, 15 – Dorsal & Laterodorsal tegmental area, 16 – Lateral parabrachial complex, 17 – Principal sensory, 18 – Dorsoventral tegmental area/dorsal Raphe-caudal nuclei, 19&20 – Cerebellum. L: left; R: right.

Figure 4. Representative examples of brain clusters with significant developmental changes in functional connectivity (FC) with amygdala. FC between right/left amygdala and four representative clusters showing a significant main effect of age. L: left; R: right.

Although there were no main effects of maltreatment, a caregiving group by age interaction effect was detected in amygdala FC with two main clusters: the left locus coeruleus (LC)/laterodorsal tegmental area (LDTA) and left periamygdaloid cortex (PAC)/basal amygdala (BA). Maltreatment effects emerged with age so that, while controls’ FC strengthened between 12 and 18 months, maltreated animals’ FC with LC/LDTA weakened (became uncoupled) or became negatively coupled with PAC/BA (FDR-corrected (q = 0.05), t > 7.146, p < 2.5 × 10−4, cluster threshold ≥ 2 voxels; Figure 5). Post hoc (t test) comparison of the means confirmed controls had stronger FC with both clusters than maltreated animals at 18 months (PAC/BA t (5.9) = 4.47, p = .0043, η2 = 0.44; LC/LDTA t 4.3 = 3.7, p = .0179, η2 = 0.24) and also at 12 months for the LC/LDTA (t (11) = 2.49, p = .0302; η2 = 0.07) but not PAC/BA (t (10.3) = −0.36, p = .7274, η2 = 0.002). Although not significant based on post hoc comparisons, LC/LDTA seems higher in maltreated than controls initially (at 3 months), followed by gradual decoupling at later ages.

Figure 5. Brain clusters showing a significant group (condition) by age interaction effect on functional connectivity with amygdala. (a) Periamygdaloid cortex/basal amygdala (PAC/BA). (b) Locus coeruleus (LC)/laterodorsal tegmental area (LDTA). L: left; R: right. (c) Developmental trajectories of amygdala FC with these two clusters show maltreatment effects emerging with age (between 12 and 18 months) so that, while control animals’ FC strengthens, maltreated animals’ FC with LC/LDTA weakens (becomes uncoupled) or becomes negatively coupled with PAC/BA (left).

Associations between postnatal cortisol exposure and maltreatment effects on amygdala FC

Associations with amygdala-PFC FC from ROI–ROI analysis

Linear regression models were run to test whether hair cortisol concentrations at 6 months predicted amygdala–PFC FC group effects detected in the LMM analysis. Hair cortisol at 6 months significantly predicted amygdala-dlPFC (BA9) at 12 months in the right hemisphere (β = 0.0036, F (1,5) = 6.6, p = .0497; adjusted R 2 = 0.48; Figure 6a); higher cortisol was associated with a switch from negative to positive coupling. No other significant associations were found between postnatal cortisol exposure and amygdala–PFC FC.

Figure 6. Associations between hair cortisol levels at 6 months and amygdala functional connectivity (FC). Higher hair cortisol accumulation from birth through 6 months predicts: (a) switch from negative to positive coupling between dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) (BA 9) and the amygdala; (b) weaker FC between periamygdaloid cortex/basal amygdala and locus coeruleus (LC)/laterodorsal tegmental area (LDTA) clusters and the amygdala.

Associations with whole brain voxel-wise amygdala FC

Linear regression models were run to test whether hair cortisol concentrations at 6 months predicted the maltreatment effects identified in the MLM (AFNI 3dLME) analysis on amygdala FC with PAC/BA and LC/LDTA clusters at 18 months of age. Hair cortisol at 6 months significantly predicted amygdala FC with the PAC/BA cluster (β = −0.0027, F (1,5) = 8.2, p = .0351; adjusted R 2 = 0.56) and with the LC/LDTA cluster (β = −0.0028, F (1,5) = −8.7, p = .0003;adjusted R 2 = 0.9) at 18 months (Figure 6b).

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to determine the developmental impact of infant maltreatment on amygdala FC longitudinally, from macaque infancy through the juvenile (prepubertal) period, which may underlie the enhanced emotional and stress reactivity reported previously by our group in maltreated animals. This study utilized a well-established rhesus monkey model of infant maltreatment by the mother leading to infant distress. RsfMRI scans were collected longitudinally on these animals during infancy (at 3 and 6 months of age) and during the juvenile prepubertal period (at 12 and 18 months of age). ROI–ROI analyses examined specific alterations in amygdala–PFC circuit FC that could explain the higher emotional reactivity, anxiety, and stress neuroendocrine activity reported in these maltreated animals (Bramlett et al., Reference Bramlett, Morin, Guzman, Howell, Meyer and Sanchez2017, Reference Bramlett, Wakeford, Morin, Guzman, Siebert, Howell and Sanchez2018; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017). From infancy to the juvenile period, maltreated animals showed weaker amygdala FC with subgenual cingulate (BA 25) and ACC (BA 24) than controls –although only in females – and with OFC (BA 13) and dlPFC (BA 9) in both sexes. Stronger FC was also found between left and right amygdala in maltreated than control animals. The amygdala FC voxel-wise analysis detected developmental increases with age with many regions, likely reflecting increased processing of socioemotionally relevant stimuli from infancy to the juvenile period. It also identified maltreatment effects on amygdala FC that emerged with age. Thus, whereas controls’ amygdala functional coupling with regions implicated in arousal and stress (i.e., LC/LDTA) increased during the juvenile period, it became weaker in maltreated animals, and was predicted by higher cortisol exposure during infancy. These findings suggest that maternal maltreatment results in developmental alterations of amygdala circuits that include a weakened amygdala FC with PFC and brainstem arousal centers, some of them predicted by exposure to elevated cortisol levels during infancy. Future studies are needed to identify the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the dynamic developmental changes and alterations we have uncovered in theses circuits, which could generate useful neural biomarkers for future studies testing interventions in individuals with childhood maltreatment and other adverse experiences.

Our exploratory, seed-based voxel-wise analysis showed, first of all, that amygdala FC with PFC subregions and the ACC (BA 24) are positively coupled, which is consistent with the findings from the ROI-ROI analysis. In contrast to a previous study in adult macaques reporting absence of negative FC between amygdala and other regions of the brain (Grayson et al., Reference Grayson, Bliss-Moreau, Machado, Bennett, Shen, Grant and Amaral2016), we found negative FC with the posterior cingulate cortex, cerebellum, and motor, posterior parietal, and occipital (visual) cortices. These findings are consistent with other reports in adult macaques (Reding et al., Reference Reding, Grayson, Miranda-Dominguez, Ray, Wilson, Toufexis and Sanchez2019), including a lack of negative FC between amygdalae and hypothalamus. Our results are also consistent with studies in adult humans reporting positive amygdala FC with regions throughout the temporal lobe, bilateral amygdalae and hippocampal regions, subcortical regions (e.g., thalamus and caudate), insula, and brainstem, and negative FC with cerebellum, and occipital and parietal lobes (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Shehzad, Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, Gotimer and Milham2009).

Secondly, the seed-based analyses showed brain wide strengthening of amygdala FC with many regions in the brain as infants mature. This may support increased processing of social and emotional stimuli as the infants mature, especially in relation to the emergence of threat and fear responses as the animals go through weaning (3–6 months), and increased exploration, play with peers, and independence from the mother, particularly during the juvenile period (12, 18 months) (Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, McCormack and Howell2015). Similar changes in amygdala FC have already been mapped to amygdala functional maturation during weaning in rat pups (Sullivan, Landers, Yeaman, & Wilson, Reference Sullivan, Landers, Yeaman and Wilson2000). The developmental changes in amygdala FC were also region-specific, including certain amygdaloid nuclei, regions along the ventral visual pathway and other temporal sensory areas, and the cerebellum.

Some of the discrepancies between our voxel-wise analysis results and other macaque reports in relation to positive versus negative FC valence might be explained by developmental changes in amygdala FC with these regions. Among regions showing a main effect of age, amygdala FC increased with age in regions of the ventral visual pathway (STS, TEav, TEad, TPO), which may support the emergence of face processing and facial expression recognition during the first few months of life (Kuwahata, Adachi, Fujita, Tomonaga, & Matsuzawa, Reference Kuwahata, Adachi, Fujita, Tomonaga and Matsuzawa2004; Lutz, Lockard, Gunderson, & Grant, Reference Lutz, Lockard, Gunderson and Grant1998; Muschinski et al., Reference Muschinski, Feczko, Brooks, Collantes, Heitz and Parr2016; Parr et al., Reference Parr, Murphy, Feczko, Brooks, Collantes and Heitz2016; Sugita, Reference Sugita2008). Interestingly, prior to 18 months of age, amygdala FC with right TPO/STS was close to zero, consistent with previous reports in children (Gabard-Durnam et al., Reference Gabard-Durnam, Flannery, Goff, Gee, Humphreys, Telzer and Tottenham2014), and interpreted by the authors as functional uncoupling between these regions, which becomes stronger during the juvenile period when higher-order face processing has matured and inputs from the amygdala are pruned and refined (Webster, Ungerleider, & Bachevalier, Reference Webster, Ungerleider and Bachevalier1991a, Reference Webster, Ungerleider and Bachevalier1991b) to inform on the valence of facial expressions.

Amygdala FC with the cerebellum was found to decrease with age, in contrast to what has been reported in humans, where a strengthening between centromedial amygdala (CMA) and the cerebellum emerges with age (Qin, Young, Supekar, Uddin, & Menon, Reference Qin, Young, Supekar, Uddin and Menon2012), as the CMA and its connections regulate reflexive and defensive behaviors in response to fear (LeDoux, Reference LeDoux2000, Reference LeDoux2007). Other regions involved in sensory processing and memory (entorhinal cortex, parasubiculum, perirhinal cortex) also showed decreased FC with the amygdala with age in our animals, although it has been reported to be strong in adulthood, especially amygdala–BLA (basolateral amygdala). Perhaps this is another circuit that is still developing and may “switch” and become stronger during adolescence and adulthood (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Young, Supekar, Uddin and Menon2012), as this connectivity is important for detecting and perceiving fearful stimuli.

Our seed-based analysis also showed a maltreatment by age interaction effect in the left LC/LDTA and left PAC/BA, regions implicated in arousal, vigilance, and fear learning, with maltreatment effects emerging with age. Thus, while controls’ amygdala FC with LC/LDTA and PAC/BA strengthened between 12 and 18 months, maltreated animals’ FC weakened (became uncoupled) between amygdala–LC/LDTA or became negatively coupled with PAC/BA. Interestingly, FC with LC/LDTA seemed initially higher in maltreated than controls (at 3 months), which parallels the hyperarousal and reactivity observed during infancy, followed by gradual decoupling of the two regions at later ages (12 and 18 months: juvenile period). Although this is speculative, such decoupling could potentially serve an adaptive role to downregulate the arousal system, as reported in some studies with maltreated children (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Gold, Duys, Lambert, Peverill and Pine2016).

Our finding that hair cortisol at 6 months is predictive of FC in LC/LDTA and PAC/BA clusters at 18 months of age, although from a very small subset of animals, is consistent with previous reports of effects of cortisol/glucocorticoid exposure on FC. Exposure to chronic stress and/or glucocorticoids affects spine density and dendritic arborization, in circuitry vulnerable to the effects of trauma (McEwen, Reference McEwen2004; Roozendaal, McEwen, & Chattarji, Reference Roozendaal, McEwen and Chattarji2009; Vyas, Mitra, Shankaranarayana Rao, & Chattarji, Reference Vyas, Mitra, Shankaranarayana Rao and Chattarji2002). Some of these regions, such as PFC, the amygdala, and hippocampus, have high levels of glucocorticoid receptors, which suggests they are particularly sensitive to chronic exposure to cortisol (Anisman, Zaharia, Meaney, & Merali, Reference Anisman, Zaharia, Meaney and Merali1998; Sanchez, Milanes, Pazos, Diaz, & Laorden, Reference Sanchez, Milanes, Pazos, Diaz and Laorden2000a; Sanchez, Young, Plotsky, & Insel, Reference Sanchez, Young, Plotsky and Insel2000b). FC studies in adult men given a one-time dose of hydrocortisone, have also reported uncoupling of the amygdala, especially a reduction in positive FC with regions involved in initiating and maintaining the stress response, such as the LC, in addition to reducing negative FC with regions involved in executive functions (Henckens, van Wingen, Joels, & Fernandez, Reference Henckens, van Wingen, Joels and Fernandez2012). Thus, exposure to chronically high glucocorticoid levels during early development (as we previously reported in (Drury et al., Reference Drury, Howell, Jones, Esteves, Morin, Schlesinger and Sanchez2017) could initiate effects that may last into the juvenile period in maltreated animals, through such FC disconnection between amygdala–LC/LDTA and -PAC/BA clusters.

Cortisol fluctuations occur normally across the circadian rhythm and during ultradian oscillations on a smaller temporal scale, aiding in the stabilization of spines and pruning of pre-existing synapses, a balance important in learning and plasticity (Liston et al., Reference Liston, Cichon, Jeanneteau, Jia, Chao and Gan2013). However, exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids, even as little as 30 min of increased exposure (Chen, Dube, Rice, & Baram, Reference Chen, Dube, Rice and Baram2008), prevents the formation of new spines and pruning of synapses during development, a time of enhanced plasticity and remodeling (Liston & Gan, Reference Liston and Gan2011). Deficits in spine stabilization, formation, maintenance, and synaptic pruning during this period of development could lead to reduced structural connectivity of amygdala circuits, potentially resulting in a weaker FC of the amygdala to LC/LDTA and PAC/BA, and may mediate increased synaptic transmission in thalamic sensory neurons (by way of activating cholinergic projections), during states of fear. In studies of early developmental exposure to glucocorticoids in rodents, increased recruitment of cholinergic neurons in the LDTA can lead to prolonged hyperanxious states (Borges et al., Reference Borges, Coimbra, Soares-Cunha, Ventura-Silva, Pinto, Carvalho and Sousa2013; Kaufer, Friedman, Seidman, & Soreq, Reference Kaufer, Friedman, Seidman and Soreq1998). This “programming” of LDTA neurons towards increased activity could lead to heightened arousal and vigilance reported in maltreated animals despite weakened FC with the amygdala. Rodent studies have shown that cholinergic neurons in the LDTA also project to the LC (Jones & Yang, Reference Jones and Yang1985). Activation of these terminals through perfusions of cholinoceptor agonists in the LC increase neuronal firing rate and arousal, suggesting that the LDTA projections to the LC are bolstering arousal through excitatory connections (Egan & North, Reference Egan and North1985; Engberg & Svensson, Reference Engberg and Svensson1980). In response to stressful stimuli, LC neurons are activated (Abercrombie & Jacobs, Reference Abercrombie and Jacobs1987; Aston-Jones, Chiang, & Alexinsky, Reference Aston-Jones, Chiang and Alexinsky1991; Grant, Aston-Jones, & Redmond, Reference Grant, Aston-Jones and Redmond1988; Rasmussen, Morilak, & Jacobs, Reference Rasmussen, Morilak and Jacobs1986) and facilitate norepinephrine increase in the amygdala through terminals in the BLA (Asan, Reference Asan1998). This pathway is thought to support proper neuroendocrine responses to a stressor or fearful stimulus. Reciprocal connections from the amygdala to the LC (Van Bockstaele, Bajic, Proudfit, & Valentino, Reference Van Bockstaele, Bajic, Proudfit and Valentino2001) provide feedback to facilitate an increase in responding to stressful stimuli, and therefore arousal (Goldstein, Rasmusson, Bunney, & Roth, Reference Goldstein, Rasmusson, Bunney and Roth1996), which may be implicated in the development of maladaptive responses to stress in fear disorders (Buffalari & Grace, Reference Buffalari and Grace2007). Norepinephrine (NE) projections to the amygdala also modulate memories of aversive stimuli (McGaugh, Reference McGaugh2002) through consolidation of learning within the BLA (Gallagher, Kapp, Musty, & Driscoll, Reference Gallagher, Kapp, Musty and Driscoll1977). Thus, a weakened amygdala FC (or uncoupling) of this pathway in maltreated animals, could potentially contribute to abnormal regulation of fear learning to specific cues, and noise in this circuit during memory consolidation, leading to increased generalized fear and stress responses.

Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), a peptide hormone involved in the stress response, also plays a role in the LC NE system. In response to chronic stress, there is a postsynaptic sensitization to CRF in the LC, leading to an increased release of NE to downstream targets (Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Jedema, Rabinovic, Mana, Zigmond and Sved1997). This plasticity may result in hyperactivity or hyperresponsiveness of the LC–NE system. As detailed above, disconnection between amygdala and LC could result from exposure to chronic stress-induced increased cortisol, as previously shown in human studies (Henckens et al., Reference Henckens, van Wingen, Joels and Fernandez2012). One could speculate that such amygdala decoupling could be adaptive, downregulating the arousal system and resulting in blunted emotional or physiological responses prioritizing activity in other networks to avoid overwhelming the system (or even helping normalize the HPA axis activity). Indeed, blunted physiological responses (skin conductance [SCR] and heart rate acceleration) to threatening stimuli have been reported in children and adolescents with a history of childhood maltreatment (Busso, McLaughlin, & Sheridan, Reference Busso, Mclaughlin and Sheridan2017; Machlin, Miller, Snyder, McLaughlin, & Sheridan, Reference Machlin, Miller, Snyder, Mclaughlin and Sheridan2019; MacMillan et al., Reference Macmillan, Georgiades, Duku, Shea, Steiner, Niec and Schmidt2009; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Gold, Duys, Lambert, Peverill and Pine2016; Ouellet-Morin et al., Reference Ouellet-Morin, Odgers, Danese, Bowes, Shakoor, Papadopoulos and Arseneault2011; Trickett, Gordis, Peckins, & Susman, Reference Trickett, Gordis, Peckins and Susman2014), as well as in adults that experienced trauma across the lifespan, in parallel to blunted startle responses (D'Andrea, Pole, DePierro, Freed, & Wallace, Reference D'Andrea, Pole, DePierro, Freed and Wallace2013; Heleniak, McLaughlin, Ormel, & Riese, Reference Heleniak, Mclaughlin, Ormel and Riese2016; Lovallo, Farag, Sorocco, Cohoon, & Vincent, Reference Lovallo, Farag, Sorocco, Cohoon and Vincent2012; McTeague & Lang, Reference Mcteague and Lang2012), supporting our speculative interpretation. Interestingly, these blunted physiological responses have been reported in fear conditioning paradigms, where maltreated children exhibit reduced SCR towards the fear stimulus (CS+), and do not show a dissociable SCR between fear/safety stimuli (CS+/CS-) (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Gold, Duys, Lambert, Peverill and Pine2016). This may suggest deficits in fear learning/associative learning and is consistent with blunted fear conditioning responses and impaired discrimination of fear/safety stimuli we have identified in our maltreated animals when they reach adolescence (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Wakeford, Howell, Guzman, Siebert, Kazama and Sanchez2018).

Regarding the results of the amygdala–PFC ROI-ROI analysis, weaker FC was found between amygdala and ACC/mPFC in maltreated animals, particularly in females (i.e., weaker amygdala FC with mPFC regions: BA 25 (subgenual cingulate), BA 24 (ACC)) as well as with dlPFC region BA 9, and OFC region BA 13. These findings are consistent with previous reports in human populations with early adverse experiences (VanTieghem & Tottenham, Reference VanTieghem and Tottenham2018), including adolescents and adults with histories of childhood maltreatment (Thomason et al., Reference Thomason, Marusak, Tocco, Vila, McGarragle and Rosenberg2015) and in humans with PTSD (Fonzo et al., Reference Fonzo, Simmons, Thorp, Norman, Paulus and Stein2010b). A weak amygdala–mPFC FC is linked to impaired stress and emotional regulation, and can contribute to arousal dysregulation through hypervigilance and attention bias to threat.

Weaker FC between amygdala and left periamygdala/basal amygdala in maltreated than control animals also emerged at the later age (18 months). In fact, at this age controls’ FC gets stronger (positive) and maltreated animals’ FC becomes uncoupled. The periamygdaloid cortex receives direct connections from the olfactory bulb and is involved in conditioning to explicit environmental sensory stimuli. The basal amygdala also plays a critical role in fear learning, specifically conditioned fear expression and extinction (Amano, Duvarci, Popa, & Pare, Reference Amano, Duvarci, Popa and Pare2011). Previous studies in humans have reported increased activation of the amygdala when subjects have prior awareness of the aversive nature of the stimuli (Morris, Ohman, & Dolan, Reference Morris, Ohman and Dolan1998). Perhaps the reduced FC between amygdalae subnuclei (such as the left basal amygdala) could interfere with the modulation of the fear response to learned aversion of environmental stimuli in maltreated animals.

We would also like to discuss briefly the potential interpretations of negative or anticorrelated FC. In previous studies, negative resting state FC has been shown to reflect competition between brain networks (i.e., default mode and task positive networks; (Kelly, Uddin, Biswal, Castellanos, & Milham, Reference Kelly, Uddin, Biswal, Castellanos and Milham2008) or a history of regulation on one region over another (i.e., limbic circuits; (Liang, King, & Zhang, Reference Liang, King and Zhang2012; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Shehzad, Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, Gotimer and Milham2009). However, some of the negative FC (correlations) between regions in our study are very close to zero, which may in fact be due to the regression of the global signal, which would center all correlations about zero, and not represent a true negative correlation. Additionally, near-zero correlations could be interpreted as an uncoupling of the amygdala with other regions in maltreated animals. Uncoupling or disconnection between limbic and regulatory regions, such as the amygdala and insula with the ACC, has been shown in individuals with PTSD when evaluating fearful/threatening stimuli (Fonzo et al., Reference Fonzo, Simmons, Thorp, Norman, Paulus and Stein2010a; Rockstroh & Elbert, Reference Rockstroh and Elbert2010).