Emotional availability (EA) has been called the “connective tissue of healthy socioemotional development” (Easterbrooks & Biringen, Reference Easterbrooks and Biringen2000, p. 123). The emotional dialogue between a child and caregiver, in which both partners are attuned, and responsive, to a range of emotional interactions with the other (Emde, Reference Emde and Taylor1980), is intimately interwoven with developing neurobiological, physiological, and emotional systems of regulation from the earliest days of infancy (Shonkoff & Phillips, Reference Shonkoff and Phillips2000).

The early role of caregivers in helping to establish patterns of emotion regulation via sensitive responsiveness to emotional cues forecasts individual differences in both infant–caregiver attachments and patterns of emotion regulation. Even beyond infancy, emotion regulation is an ongoing developmental issue for children as they enter and negotiate new developmental contexts and relationships beyond the sphere of the primary attachment figures (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, Reference Bernier, Carlson and Whipple2010; Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1979; Cassidy, Reference Cassidy, Cassidy and Shaver2008).

The present study examines several questions that are relevant to attachment and EA theories and that are consistent with a developmental psychopathology framework (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1993; Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009) that aims to understand developmental trajectories of adaptation and maladaptation and the “interplay of intrapsychic, interpersonal, and ecological influences on adjustment over time” (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, Reference Cummings, Davies and Campbell2000, p. 23).

Specifically, our goals in this study were to investigate, in a sample of children at high psychosocial risk: (a) whether maternal EA was related to children's attachment behavior in middle childhood, a developmental period where there is little empirical knowledge about the links between attachment and the emotional context (Kerns, Reference Kerns, Cassidy and Shaver2008); (b) whether maternal EA was associated with children's developmental organization and functioning outside of the mother–child relationship; and (c) whether problems in maternal EA in childhood would be foreshadowed years earlier, in aberrant maternal behavior in infancy. These goals are informed by a developmental psychopathology perspective that highlights such key questions as the interactive processes and developmental mechanisms associated with varying developmental trajectories of adaptation and maladaptation; the “critical role of timing in the organization of behavior” (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009); and patterns of competence in the context of risk or adversity.

We address some of these central questions and expand on the results of a previous paper (Easterbrooks, Biesecker, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Easterbrooks, Biesecker and Lyons-Ruth2000) in which we found that EA in the mother–child dyad during middle childhood was predicted by infant attachment security and by maternal depressive symptoms during infancy. In the present study we extend the previous work by examining infancy-period maternal behavioral precursors of later maternal EA, and we examine whether maternal EA is related to children's behavior both within and beyond the mother–child attachment relationship.

EA and Attachment

Emotion regulation is central to the core construct of attachment (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978; Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1979). According to Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1969), attachment behavior is activated under conditions of distress or fear. Felt security is achieved with the help of an accessible and sensitive caregiver, resulting in deactivation of the fear–wariness behavioral system in order that exploration and learning may take place. Thus, attachment and emotion regulation (particularly of negative emotions) are intricately intertwined, and emotions serve an important regulatory function within attachment relationships (Cassidy, Reference Cassidy, Cassidy and Shaver2008).

Cassidy (Reference Cassidy, Cassidy and Shaver2008, p. 7) remarked “individual differences in attachment security have much to do with the ways in which emotions are responded to, shared, communicated about, and regulated within the attachment relationship.” Attachment security is associated with more synchronous and “authentic” (in terms of the relation between felt and expressed emotions) emotional communications (Cassidy & Berlin, Reference Cassidy and Berlin1994; Mikulincer & Shaver, Reference Mikulincer, Shaver, Cassidy and Shaver2008; Thompson, Reference Thompson, Cassidy and Shaver2008), and more effective coping with stress (Contreras & Kerns, Reference Contreras, Kerns, Kerns, Contreras and Neal-Barnett2000). In insecure attachment relationships, emotions may be dismissed or dampened (characteristic of avoidant attachments), or heightened and not easily deactivated (characteristic of ambivalent attachments), no consistent strategy may be in evidence (characteristic of disorganized attachments); these emotion regulation behaviors serve to maintain the relationship with the attachment figure (Cassidy, Reference Cassidy, Cassidy and Shaver2008), but they are not without “cost” to the child. Difficulties in emotion regulation are featured prominently “in various forms of psychopathology across the lifespan” (DeKlyen & Greenberg, Reference DeKlyen, Greenberg, Cassidy and Shaver2008, p. 638).

The empirical literature documents robust links between assessments of attachment and EA in parent–child interactions, primarily concurrently (e.g., Easterbrooks et al., Reference Easterbrooks, Biesecker and Lyons-Ruth2000; Swanson, Beckwith, & Howard, Reference Swanson, Beckwith and Howard2000; Ziv, Aviezer, Gini, Sagi, & Koren-Karie, Reference Ziv, Aviezer, Sagi and Koren-Karie2000). Maternal EA, manifest in attunement and sensitive responsiveness is associated with secure attachments (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). Insecure (and particularly disorganized) attachments are linked with insensitive, intrusive, or hostile maternal behavior as assessed by the EA Scales (as reported in Biringen, Reference Biringen2008). These links are theoretically expected, particularly because the EA Scales are rooted in attachment theory. However, because the EA Scales may be applied to both low stress contexts (that may elicit positive EA) as well as stressful contexts (most salient for eliciting the attachment representational and behavioral systems) the connections between measures of attachment and EA may be moderate.

Most of the empirical work focuses on EA attachment linkages during the first 3 years of life; however, the development and consolidation of patterns of attachment and emotion regulation continue beyond infancy (Thompson, Reference Thompson, Cassidy and Shaver2008). According to Bowlby's (Reference Bowlby1973) developmental model of attachment, the goal-corrected phase of attachment, emerging in early childhood, focuses on the availability of attachment figures as sources of felt security (Kerns, Reference Kerns, Cassidy and Shaver2008; Marvin & Britner, Reference Marvin, Britner, Cassidy and Shaver2008). Changes in the attachment system from infancy to early childhood alter the focus of felt security from maintenance of physical proximity to the attachment figure to that of availability, including EA (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969). Absence of this felt security may stem from a lack of EA provided by the caregiver.

Despite these conceptual links between attachment and EA in childhood and adolescence (Allen, Reference Allen, Cassidy and Shaver2008), Kerns (Reference Kerns, Cassidy and Shaver2008) noted the dearth of studies examining aspects of attachment and emotion in middle childhood, either concurrently or longitudinally. One reason for this gap is the lack of valid assessments of these constructs for the period beyond early childhood. One goal of the present study was to address the links between EA and attachment beyond infancy, in the period of middle childhood; because the links between caregiver EA and developmental maladaptation may be particularly evident among children with disorganized attachments (DeKlyen & Greenberg, Reference DeKlyen, Greenberg, Cassidy and Shaver2008), we include that focus in our study.

Disorganized/Controlling Attachment Behavior

More specifically, we sought to investigate the links between disorganized and controlling attachment behavior in middle childhood and EA in mother–child interactions. Attachment behavior, both in infancy and beyond, may be demonstrated in organized patterns (e.g., secure, insecure avoidant, insecure ambivalent/resistant) or may be disorganized, lacking coherently organized patterns or strategies (Main & Solomon, Reference Main, Solomon, Brazelton and Yogman1986; Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Jacobvitz, Cassidy and Shaver2008). Disorganized and controlling attachments are considered “a potent risk factor” (DeKlyen & Greenberg, Reference DeKlyen, Greenberg, Cassidy and Shaver2008, p. 657), part of a developmental trajectory associated with various forms of psychopathology. Conceptually, EA and disorganized/controlling attachments are intertwined (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Jacobvitz, Cassidy and Shaver2008); emotional communication on the part of the attachment figure is featured prominently in conceptualizations of the genesis and maintenance of disorganized attachments. Purported mechanisms for the development of disorganized attachment behavior include difficulties or distortions in caregiver EA: frightening or frightened behavior on the part of the caregiver (Hesse & Main, Reference Hesse and Main2006) and caregiver unavailability in helping to regulate infant fear or distress (Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, & Parsons, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999). Difficulties in emotion regulation of stress are evident among infants with disorganized attachments (Hertsgaard, Gunnar, Erickson, & Nachmias, Reference Hertsgaard, Gunnar, Erickson and Nachmias1995; Spangler & Schieche, Reference Spangler and Schieche1998).

Across the developmental course of childhood, attachments that were disorganized in infancy most often (in 63%–75% of children) become organized, often in the form of controlling behaviors on the part of the child (Cicchetti & Barnett, Reference Cicchetti and Barnett1991; Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Jacobvitz, Cassidy and Shaver2008; Main & Cassidy, Reference Main and Cassidy1988; Moss, Cyr, Bureau, Tarabulsy, & Dubois-Comtois, Reference Moss, Cyr, Bureau, Tarabulsy and Dubois-Comtois2005; Wartner, Grossman, Fremmer-Bombik, & Suess (Reference Wartner, Grossman, Fremmer-Bombik and Suess1994). Organized controlling patterns frequently take the form of (a) caregiving behavior, manifest as attempts to support and maintain the availability of the caregiver through positive/helpful activities that provide structure to child–parent interactions; and (b) controlling punitive behavior that structures the interactions through directive behavior that may have a harsh, embarrassing, or humiliating quality. In the absence of effective external regulation provided by a sensitive caregiver, controlling behavior may serve to help children regulate the stress associated with fearful, frightening, or helpless behavior on the part of the attachment figure (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Jacobvitz, Cassidy and Shaver2008; Solomon, George, & DeJong, Reference Solomon, George and DeJong1995). They may be attempts to secure the attention and involvement, if not EA, of the parent.

Developmental correlates of disorganized and controlling attachment behavior in childhood

Little is known about the developmental correlates of attachment disorganization in middle childhood, in part because until recently there has been no behavioral coding system for capturing these patterns beyond the preschool years (Bureau, Easterbrooks, Killam, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Bureau, Easterbrooks, Killam and Lyons-Ruth2006). Recently, however, using the Middle Childhood Disorganization and Control (MCDC) scales, we demonstrated that children with controlling punitive, caregiving, and disorganized attachment behaviors in middle childhood were more likely to demonstrate greater externalizing and internalizing behavior problems at age eight as reported by their mothers (Bureau, Easterbrooks, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Bureau, Easterbrooks and Lyons-Ruth2009).

This relation in middle childhood replicates a pattern of association documented at preschool age (Bretherton et al., Reference Bretherton, Oppenheim, Buchsbaum and Emde1990). From 3 to 6 years of age, children with disorganized/controlling attachments show the highest levels of disruptive behaviors (externalizing problems) and internalizing symptoms, compared to secure and insecure-organized children (DeKlyen & Greenberg, Reference DeKlyen, Greenberg, Cassidy and Shaver2008; Greenberg, Speltz, DeKlyen, & Endriga, Reference Greenberg, Speltz, DeKlyen and Endriga1991; Moss, Bureau, Cyr, Mongeau, & St-Laurent, Reference Moss, Bureau, Cyr, Mongeau and St-Laurent2004; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Smolla, Cyr, Dubois-Comtois, Mazzarello and Berthiaume2006; Munson, McMahon, & Spieker, Reference Munson, McMahon and Spieker2001; O'Connor, Bureau, McCartney, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference O'Connor, Bureau, McCartney and Lyons-Ruth2011; Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, George and DeJong1995). Furthermore, disorganized/controlling children have somewhat poorer interactions with friends and worse relationships with teachers (McElwain, Cox, Burchinal, & Macfie, Reference McElwain, Cox, Burchinal and Macfie2003; O'Connor & McCartney, Reference O'Connor and McCartney2006). Fearon and Belsky (Reference Fearon and Belsky2011) recently reported that disorganized attachments, particularly among boys from risky social environments, conveyed an escalating risk for externalizing behavior problems across the elementary school years. These relationships with peers and teachers become increasingly important to children's mental health and thriving as they move through childhood. The present study extends this work to address the links between maternal EA and teacher-reported behavior problems, decoupling potential confounds with the mother–child relationship in both reporter (teacher vs. mother) and context (school vs. home).

This literature, then, clearly identifies the controlling/disorganized spectrum of attachment behavior as one indicator of risk for psychopathology. However, attachment assessments in middle childhood, while validated in relation to interactions in infancy (Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Easterbrooks and Lyons-Ruth2009), still have not been assessed in relation to concurrent patterns of parent–child interaction in middle childhood, and this is one goal of our study.

Present Study

The present study had several aims: (a) the first goal was to investigate links between the EA of mothers and their children's disorganized and controlling attachment behaviors in middle childhood among a group of children at high risk for developmental challenges due to low income, and in some cases, early parenting difficulties. Assessing EA in middle childhood (age 7) allowed us to investigate the gap in the literature concerning how attachment and emotion organization are associated beyond the early childhood period (Kerns, Reference Kerns, Cassidy and Shaver2008). (b) A second goal was to examine the longitudinal (6-year) coherence of maternal behavior in interactions with their children from infancy to middle childhood. (c) A third goal was to examine whether maternal EA in childhood was associated with aspects of children's adaptation outside of mother–child interactions (e.g., behavior problems in school; child depressive symptoms).

Method

Participants and design

Participants were 43 low-income mother–child dyads (19 girls) who were seen in infancy (12–18 months of age) and middle childhood (7–8 years of age). In this sample of 43 families, 80% of children were European American; 51% of mothers were single parents; most families were of low income (average per person weekly income was $90 per week); half of families had incomes below the federal poverty level. All families were recruited initially in infancy as part of a sample of 76 families participating in a study of the impact of social risk factors on infant development (Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll, & Stahl, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll and Stahl1987). Among the infant sample, 54% (41; 18 girls) were low-income families referred to the study by health or social service agency staff because of concerns about the quality of the parent–infant relationship; 46% (35; 15 girls) were families from the community demographically matched to referred families on the following seven factors: per person family income; mother's education, age, and race; and infant's age, sex, and birth order. Community families were screened for significant psychiatric histories, history of abuse or neglect of children, or obvious parenting difficulties during a 1-hr home observation. To participate in the study, all families were required to be below the official federal poverty level. In infancy, 66% of families had incomes under $50 per person/per week, and 62% received government aid. In infancy, the sample was 81% Caucasian, 11% Latino, 4% African American, and 4% biracial children. Forty percent of mothers were not high school graduates (40% had high school diploma only; 20% had some postsecondary training); 49% were single parents.

At the middle childhood follow-up (age 7), 56 families were relocated (74%), 51 agreed to participate (67%), and 5 refused participation. The remaining 20 families could not be relocated. Of the 51 participating families, 8 families' videotapes were not available due to equipment failure, scheduling difficulties, or having moved too far from the research lab. Thus, 43 families form the basis for this report.

The 43 families reported on here did not differ significantly from the rest of the 76 families in infancy on demographic measures including family income, F (1, 75) = 0.98, ns, maternal education, χ2 (76) = 0.32, ns, ethnicity, χ2 (76) = 0.87, ns, and marital status/single mother family, χ2 (76) = 0.55, ns. However, a higher proportion of families referred for parent–infant clinical services were not seen at follow-up, χ2 (76) = 4.53, p < .05; 54% referred versus 30% of comparison families. Attrition in middle childhood was also unrelated to any of the infancy period observations included in this report (see below): maternal involvement at home, F (1, 54) = 0.27, ns; maternal hostile-intrusiveness at home, F (1, 54) = 0.18, ns; maternal disrupted communication in the lab, F (1, 63) = 1.57, ns; infant attachment insecurity, F (1, 69) = 0.81, ns.

Measures

Because the EA assessment (the theme of this Special Section) was conducted in middle childhood, we present the middle childhood measures first, followed by the measures from infancy that we examine as predictors of EA.

Assessments in middle childhood

EA

EA was assessed in a laboratory setting when children were 7 years of age; mothers and children were observed in a 5-min reunion following an hour-long separation. Mothers and children were instructed to interact in any way that they chose. The interactions were coded for maternal behavior using the EA Scales (Biringen, Robinson, & Ende, Reference Biringen, Robinson and Emde1993) yielding scores on three maternal dimensions: (a) sensitivity (9-point scale), (b) nonhostility (5-point scale), and (c) nonintrusiveness (7-point scale).

These scores were derived from the EA Scales Scoring Manual (2nd edition; which was current at the time of the study) that contains scales for maternal sensitivity, nonhostility, and nonintrusiveness. The scoring differs from later editions in two ways: the second edition has three (vs. four) maternal scales, and several of the scales were curvilinear (in later editions optimal scores were high). Brief descriptions of the scales follow below. For maternal sensitivity, high scores indicated positive affect sharing, maternal awareness, and responsiveness to timing of child behavior; low scores indicated maternal behavior that lacked genuine positive affect, and appropriate awareness of, and responsiveness to, child bids. Maternal hostility (low end of the nonhostility scale) was represented by both overt (i.e., name calling, threats, critical blame) and covert (signs of boredom, eye rolling, sighing) behavior. Mothers who were optimally nonintrusive were aware of the child's needs and stepped in appropriately to facilitate the child's autonomous behavior. Maternal behavior that was either passive/withdrawn or poorly timed/negatively intrusive was considered not optimally “nonintrusive.”

This study utilized the second edition of the EA Scales in which the maternal nonintrusiveness scale was designed to be curvilinear (e.g., optimal scores were at midpoint). In order to address this, we calculated a new set of scores to represent “distance from the optimal EA score” (i.e., scores of 0, 1, 2, etc.) as the reference point. The maternal nonintrusiveness scale could represent behavior that was either highly intrusive (such as a mother who interfered in the child's play, or timed her bids to the child too rapidly to allow for child responsiveness) or maternal behavior that was nonoptimal in that mothers were passive, withdrawn, or emotionally/behaviorally removed from the mother–child interaction. In this sample, maternal nonintrusiveness was passive/withdrawn in nature rather than intrusive. In order to preserve clarity in interpretation, in the results and discussion we will refer to this nonintrusiveness score as “maternal passive/withdrawn” behavior, with high scores representing greater distance from the optimal score, thus greater passive/withdrawn behavior. Scores were examined to assess comparability to the third edition of the EA Scales; scores were deemed comparable in scope to the third edition (Z. Biringen, personal communication, August, 2008).

Coding of maternal EA in middle childhood was conducted by raters who were naive to the MCDC disorganized and controlling behavior coding in middle childhood and the maternal coding in infancy, as well as other study data. Intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated to assess interrater reliability (60% of cases were coded by two independent coders) for the three EA Scales: sensitivity (interclass correlation [ICC] = .98); nonhostility (ICC = .95); nonintrusiveness (passive/withdrawn behavior; ICC = .96).

Middle childhood attachment disorganization and controlling behavior

When children were 7 years of age, the MCDC scales (Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Easterbrooks, Killam and Lyons-Ruth2006) were used to score attachment behavior in the 5-min reunion following a 1-hr child–mother separation. MCDC yields scaled scores for three dimensions of children's attachment behavior: controlling–punitive, controlling–caregiving, and disorganized behaviors; higher scores indicate more punitive, controlling, or disorganized behavior.

The Controlling–Punitive Scale assesses indicators of frustration, annoyance, hostility, and humiliation toward the attachment figure. The high range of this scale is characterized by episodes of hostility toward the parent that are marked by a challenging, humiliating, cruel, or defying quality. The Controlling–Caregiving Scale includes behavior that intends to distract or modify parental affect, take charge of the interaction, or prioritize the parent's needs. The low range of this scale includes minor indications of caregiving behavior with the motivation of stimulating, modifying affect, or distracting the parent. The high range of the scale is marked by a more active form of organizing or taking charge of the interaction. Evidence of the child subordinating his/her own desires and prioritizing the parent's needs also is coded on this scale. For both of these scales, scores range from 1 (low) to 9 (high).

The Disorganized Behavior Scale codes for the extent of a diverse set of behaviors similar to the range of behaviors that characterize disorganized behavior in infancy, but adjusted for the increased verbal capacities of older children, including: (a) manifestations of fear; (b) lack of a consistent interaction strategy; (c) unpredictable, confused behavior; (d) behavior that invades the parent's intimate boundaries; (e) difficulties in expression when addressing the parent, in the absence of speech difficulties in other circumstances; (f) self-negation/self-injury; (g) disorientation/dissociation; and (h) clear preference for the stranger. Each type of disorganized behavior is coded as none, low, or high, and an overall summary rating is assigned. MCDC scores indicating greater disorganized and controlling behaviors are linked in expected ways to maternal behavior in infancy, childrearing history, and child behavior problems (Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Easterbrooks and Lyons-Ruth2009).

Coders were naive to the middle childhood EA scores and all other study data. Intraclass correlations (based on 51% of the tapes) for the MCDC scales were as follows: 0.97 punitive, 0.93 caregiving, 0.83 disorganized (M = 0.91).

Child behavior problems in school (Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL])

The Teacher Report Form of the CBCL (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991) was used to index children's behavior problems in the school setting at age seven. Children's classroom teachers completed the checklist that contains 118 problem behaviors that are scored on a 3-point scale (very true or often true, somewhat true or sometimes true, or not true, in describing the child's behavior). The CBCL generates scores on nine subscales; withdrawn, somatic complaints, anxious/depressed, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, delinquent behavior, aggressive behavior, and other problems. The addition of the delinquent behavior and aggressive behavior subscales yields an externalizing score, while the addition of the withdrawn, somatic complaints and anxious/depressed subscales yields an internalizing score. Standardized t scores for sex and age were used in this study. The instrument has excellent psychometric qualities. Test–retest reliability was established for short-term (7 days; average = 0.89 for all scales) as well as for long-term intervals (average = 0.75 after 1 year and 0.71 after 2 years for all scales). Analyses reveal that almost all the CBCL items discriminate between clinically referred and nonreferred children, indicating excellent construct validity.

Broadband summary scores are calculated for internalizing problems (e.g., somatic complaints, withdrawal, depressed behavior), externalizing problems (e.g., aggression, hostility, impulse control), and total behavior problems. Scores are standardized; standardized T scores of 70 and higher reflect clinical level problems.

Child depressive symptoms

The Dimensions of Depression Profile for Children and Adolescents (Harter & Nowakowski, Reference Harter and Nowakowski1987) was used to assess child depressive symptoms when children were 8 years of age. The self-report scale, appropriate for children aged 6 and older, consists of five, six-item subscales (self-blame, affect/mood, energy, self-worth, and suicidal ideation; upon recommendation from one of the authors of the scale, the suicidal ideation subscale was not utilized). Scores range from 1 to 4. In the original scoring high scores indicated less depressive symptomatology; in this paper we have reversed the scoring in order to enhance clarity of terms; thus, high scores indicate greater depressive symptoms. Examples of items include “Some kids feel kind of ‘down’ and depressed a lot of the time, but other kids feel ‘up’ and happy most of the time.” Factorial, convergent, discriminant, and construct validity have been demonstrated (Renouf & Harter, Reference Renouf and Harter1990). In the present sample, since the subscales were highly related to each other (α = 0.76), a composite score of depressive symptoms was used.

Maternal depressive symptoms

Mothers completed the Center For Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item, 60-point self-report scale used to measure current levels of depressive symptoms. The CES-D is a widely used instrument for assessing general depressive symptoms in nonclinical samples, and is among the most frequently used and well-validated self-report measures of depressive symptoms. The reliability and validity of the CES-D has been well established, with 100% sensitivity and 88% specificity in relation to clinical diagnosis using the cutoff scores (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977; Radloff & Locke, Reference Radloff, Locke, Weissman, Myers and Ross1986). The mothers rated items (e.g., “My sleep was restless”) according to how often they had felt that way over the course of the past week (rarely or never, little, occasionally, or much). Although a diagnosis of depression cannot be made based on CES-D results, scores of 16 or above indicate that an individual is exhibiting a clinically meaningful level of depressive symptoms (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). In the present study, the percentage of mothers reporting scores of 16 or above was 36% at the middle childhood assessment.

Assessments in Infancy

Clinical risk in infancy

Among the 43 families in the current report, 40% (n = 17) had been referred by service providers in infancy for parent–infant home-visiting services due to concerns about the quality of parental care. Referring service providers included pediatric nurses, child care staff, and mental health professionals. Of the 17 families in the referred group, 5 met criteria for infant maltreatment according to state child protective services staff; of these, 3 were categorized as infant neglect in the context of parental psychiatric disorder or substance abuse, and 2 families had maltreatment records for older siblings. The other 60% of families (n = 26) were from the community comparison group, composed of socioeconomically matched families from the same communities who were not referred for problems in care, had never been reported to state child protective services, had never been referred to clinical services oriented toward parenting, and were not observed to display problematic parenting behavior during a 1-hr screening in the home. Referred families were coded as clinical risk = 2; community families were coded as nonrisk = 1.

Maternal depressive symptoms

Mothers' depressive symptomatology was assessed when infants were 12 months old using the CES-D (see description above in section on middle childhood assessments). In the present study, the percentage of mothers reporting clinically meaningful symptoms scores of 16 or more was 44% at the infancy assessment.

Infant attachment security (18 months)

Mothers and infants were videotaped in the Strange Situation procedure (SSP; Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) at 18 months of age. In this procedure the infant is videotaped in a playroom during a series of eight structured 3-min episodes involving the baby, the mother, and a female stranger. During the observation the mother leaves and rejoins the infant twice, first leaving the infant with the female stranger, then leaving the infant alone to be rejoined by the stranger. The procedure is designed to be mildly stressful in order to increase the intensity of activation of the infant's attachment behavior. Videotapes were coded for traditional organized and disorganized attachment behavior (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978; Main & Solomon, Reference Main, Solomon, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990). The three original attachment classifications (secure, avoidant, ambivalent) were assigned both by a coder trained by Mary Main and by a computerized multivariate classification procedure developed on the original Ainsworth data (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll and Stahl1987; see also reference in Richters, Waters, & Vaughn, Reference Richters, Waters and Vaughn1988). Agreement between the two sets of classifications was 86%. Agreement on the disorganized classification between Mary Main and a second coder for 32 randomly selected tapes was 83% (k = 0.73). Additional information is available in Lyons-Ruth, Connell, and Grunehaum (Reference Lyons-Ruth, Connell and Grunehaum1990).

There were no infants who displayed organized ambivalent attachment patterns in this sample. All four infants classified as ambivalent also met criteria for the disorganized category and were classified as disorganized. The infant attachment distribution for the 43 children in the current cohort was secure 37%, insecure 21%, disorganized 42%. In the present analyses, security of attachment was indexed by a three-level variable (1 = secure, 2 = insecure-organized, 3 = insecure-disorganized).

Quality of mother–infant interaction at home at 12 months

This was coded using the Home Observation of Maternal Interaction Rating Scales (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll and Stahl1987). Naturalistic mother–infant interaction was videotaped in the home for 40 min when the infant was awake and alert. Videotapes were coded blind to other data in 10 4-min intervals on 12 5-point rating scales and one timed variable: 1 = sensitivity, 2 = warmth, 3 = verbal communication, 4 = quality of comforting touching (i.e., physical contact in the service of communicating affection, “touching-base,” or reducing distress), 5 = quantity of comforting touching, 6 = interfering manipulation, 7 = covert hostility, 8 = anger, 9 = quality of caregiving touching, 10 = quantity of caregiving touching, 11 = disengagement, 12 = flatness of affect, and 13 = time spent not in same room with baby.

Intraclass reliability coefficients for the 13 variables, coded on a randomly selected 20% of the videotapes ranged from 0.76 to 0.99. Principal components analysis of the 13 variables yielded two main factors that were used in the current study: (a) positive affective involvement (45% of variance; eigenvalue 5.81; negative loadings at >0.50 for maternal disengagement, anger, and time spent out of the room; and positive loadings for maternal sensitivity, warmth, verbal communication, quality and quantity of comforting touching, and quantity of caretaking touching); and (b) hostile-intrusiveness (14% of variance; eigenvalue 1.81; positive loadings for covert hostility and interfering manipulation). Two smaller factors, each accounting for 10% or less of the variance, have not been included in previous publications from the study and were also excluded from the present report in order to limit the number of analyses. Additional description of the Home Observation of Maternal Interaction Rating Scales and factor loadings are available in previous publications (Dutra, Bureau, Holmes, Lyubchik, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Dutra, Bureau, Holmes, Lyubchik and Lyons-Ruth2009; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll and Stahl1987).

Maternal disrupted communication

This communication with the infant was assessed in a laboratory SSP (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) when infants were 18 months of age using the Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification (AMBIANCE; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999). Scores were based on behavior over all mother–infant episodes of the SSP. The AMBIANCE assesses disrupted forms of maternal communication theoretically expected to be related to infant disorganized attachment. The AMBIANCE yields a scaled score (1–7) for extent of disrupted communication, based on frequency and severity of five types of disrupted communication with the infant: (a) affective communication errors (e.g., giving contradictory cues; nonresponse or inappropriate response to clear infant cues), (b) role confusion (e.g., self-referential or sexualized behavior), (c) negative-intrusive behavior (e.g., verbal negative remarks or physical intrusiveness), (d) disorientation (e.g., appearing frightened by infant; disoriented wandering), and (e) withdrawal (e.g., failing to greet infant; backing away from infant approach). (a) Affective communication errors, (b) role confused behavior, (c) negative-intrusive behavior, (d) fearful/disoriented behavior, and (e) withdrawal. Coders were naive to all other data on the sample. Interrater reliability on 15 randomly selected tapes for the Level of Disrupted Communication Scale was κ (weighted) = 0.93. A meta-analysis concluded that the AMBIANCE system showed stability over time (6 months to 5 years; stability coefficient 0.56, N = 203) and demonstrated concurrent and predictive validity in relation to infant disorganization (r = .35, N = 384; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Moran, Pederson and Benoit2006).

Analysis plan

Correlations between the three maternal EA scales and each of the study variables were first computed to determine which variables should be included in regression models. Then regression models were conducted separately for each of the three EA scales as dependent variables with the appropriate correlates/predictors. Regressions were rerun until only significant predictors remained. These correlational and regression analyses were conducted using multiple imputation to account for missing values (rather than listwise deletion). Multiple imputation procedures were used to estimate missing data using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo procedure (Gilks, Richardson, & Spiegelhalter, Reference Gilks, Richardson and Spiegelhalter1996). As is standard procedure for using multiple imputation after the multiple data sets were derived, analyses were conducted on each separately; the results were then converged automatically (SPSS-19.0). The benefit of multiple imputation is that the parameters, including mean and standard deviation estimates, are unbiased (Streiner, Reference Streiner2002). The percentages of missing data ranged from 0% to 28%, and these are presented in Table 1. Twenty data sets were generated with excellent efficiency (power to detect a significant effect of 98%) according to Rubin's (Reference Rubin1987, p. 114) guidelines.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of study variables in infancy and middle childhood

Note: HOMIRS, Home Observation of Maternal Interaction Rating Scales; AMBIANCE, Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification; EA, emotional availability; MCDC, Middle Childhood Disorganization and Control; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Table 1 presents descriptive information about the study variables (nonimputed data). In order to explore whether sociodemographic variables should be controlled, child gender, family income, marital status and child age were correlated with the three mother EA scale scores. There were no significant correlations (rs = −.26 to .19, ns). Therefore, demographic factors were not controlled for in regression analyses (described below) predicting the three mother–child EA scales (maternal sensitivity, maternal nonhostility, and maternal nonintrusiveness [passive/withdrawn behavior]). Mean EA scores (Table 1) indicated average maternal sensitivity that was in the nonoptimal range; an average maternal nonhostility score indicating slight, covert hostility; and maternal nonintrusiveness behavior that was moderately passive/withdrawn. Mean scores for child controlling and disorganized attachment behavior indicated punitive behavior suggesting multiple indicators of frustration, annoyance, or passive refusal; caregiving behavior suggesting brief indicators of role reversal, overbright greeting, or compulsive compliance; and low-level markers of bizarre or confused behavior, or disorientation/dissociation suggesting disorganization.

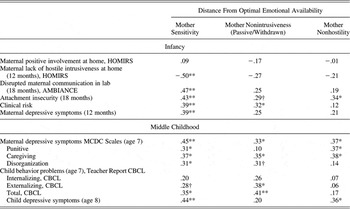

Associations between EA and indicators of child attachment, maternal interactive behaviors, and family risk in infancy and middle childhood

Pearson correlations were conducted to explore the associations between the middle childhood mother–child EA and (a) child controlling and disorganized attachment behaviors in middle childhood, (b) quality of parenting in infancy, (c) security of child attachment to mother in infancy, (d) clinical risk in infancy, and (e) maternal depressive symptoms in infancy and middle childhood. Results are presented in Table 2 and are described below. Based on these results, a series of hierarchical regressions was performed on each EA dimension, including only significantly correlated predictors in each model. Final models with significant predictors are presented in Table 3.

Table 2. Correlations between Maternal Emotional Availability Scales (age 7) and maternal behavior, caregiving risks, and child behavior in infancy and middle childhood

Note: HOMIRS, Home Observation of Maternal Interaction Rating Scales; AMBIANCE, Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification; MCDC, Middle Childhood Disorganization and Control; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Table 3. Hierarchical regression models predicting maternal EA in middle childhood

Note: EA, emotional availability; MCDC, Middle Childhood Disorganization and Control.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .01.

Correlations linking EA and middle childhood variables

The correlations showed the following contemporaneous associations between EA and the middle childhood variables.

1. Mother sensitivity: Mother insensitive behavior was associated with more punitive (p = .046), caregiving (p = .02), and disorganized (p = .046) child attachment behaviors in middle childhood as well as a higher rate of maternal depressive symptoms (p = .002).

2. Maternal nonintrusiveness (passive/withdrawn behavior): When mothers were more passive/withdrawn in interactions, children showed more caregiving behaviors (p = .035) as well as more disorganized behaviors (marginal [p = .055]) toward them. Passive/withdrawn behavior also was associated with more maternal depressive symptoms (p = .03).

3. Maternal nonhostility: When mothers showed greater hostile behavior, children showed more punitive (p = .01) and more caregiving (p = .01) attachment behavior. Maternal hostility also was associated with more maternal depressive symptoms (p = .01).

Correlations linking EA and infancy variables

The correlations revealed the following associations between early maternal behavior and later EA.

1. Mother sensitivity: Mothers who were more insensitive in interactions with their 7-year-olds had shown greater hostility in mother–child interactions at home at 12 months (p = .002), and exhibited more severely disrupted maternal communication in interactions with their infants in the lab at 18 months (p = .005). They were also more likely to be in the clinically referred group in infancy than in the community comparison group (p = .01), and they reported more depressive symptoms when children were 12 months of age (p = .008). Their infants showed greater attachment insecurity toward them at 18 months (p = .004).

2. Maternal nonintrusiveness (passive/withdrawn behavior): Mothers who showed greater passive/withdrawn behavior during middle childhood were also more likely to be in the clinically referred group in infancy than in the community comparison group (p = .05), and their infants also tended to show greater attachment insecurity toward them at 18 months (p = .07).

3. Maternal nonhostility: Children of mothers showing greater hostility during childhood were more insecure in their attachment behavior at 18 months (p = .03).

Summary of correlation analyses

In summary, there were both concurrent and longitudinal associations between mother–child EA and indicators of maternal behavior, child behavior, and characteristics of the caregiving environment. Concurrently in middle childhood, all three EA scales were associated with child disorganized and controlling attachment behaviors, and with maternal depression. Longitudinally, maternal insensitivity was associated with a plurality of risk factors in infancy, including early maternal depressive symptoms and clinical concerns about the quality of infant care. Moreover, maternal insensitive behavior in childhood was already forecast by nonoptimal mother–infant interaction, both at home and in the lab, and by insecure infant attachment. Maternal passive/withdrawn behavior and maternal hostility at age 7 also were associated with insecure attachment in infancy.

Regression models

In order to examine which variables of the significantly correlated variables were independent contributors to maternal EA, we conducted regression models for each maternal EA scale. The three final regression models including the significant predictors for each EA scale score are presented in Table 3. Results showed that maternal hostile behavior at home and disrupted communication in the lab during infancy, as well as child punitive and caregiving attachment behaviors at age 7 were significant independent contributors to the prediction of maternal sensitivity at age 7, explaining 59% of its variance. Child security of attachment in infancy and maternal depressive symptoms when children were 7 years of age predicted maternal nonintrusiveness (passive/withdrawn behavior), explaining 21% of the variance. Child insecurity of attachment in infancy, children's punitive and caregiving attachment behaviors in middle childhood, and maternal depressive symptoms in middle childhood were independently associated with maternal hostile behavior, explaining 47% of the variance.

Associations between EA and child behavior problems and depressive symptoms

A final set of analyses explored the associations between maternal EA scales and child social–emotional adaptation in childhood (see Table 2). Correlation analyses conducted between the EA Scales and teacher-reported behavior problems (age 7) and child depressive symptoms (self-reported at age 8) revealed several significant associations. Maternal insensitivity in middle childhood was associated with increased child depressive symptoms (p = .001) and increased overall child behavior problems (p = .03), as well as marginally with increased externalizing behaviors (p = .07). Greater maternal passive/withdrawn behavior in middle childhood also was associated with more child externalizing behavior (p = .02) and with more total behavior problems (p = .02); greater maternal hostility during childhood was associated with child depressive symptoms (p = .02).

In summary, as rated by teachers, externalizing and total behavior problem scores, but not internalizing behaviors, were associated with both maternal EA insensitivity and passive/withdrawn behavior). In addition, both maternal insensitivity and maternal hostility were associated with child depressive symptoms at age 8.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to investigate both the contemporaneous correlates and the developmental predictors of maternal EA in middle childhood. Attachment theory (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969, Reference Bowlby1973), and the tenets of developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1993; Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009), suggest that lack of maternal EA will compromise children's healthy emotional and behavioral organization, both within and outside of the mother–child relationship. In this study we employed a developmental psychopathology perspective that considers pathways, processes, and mechanisms toward and away from the development of adaptation and maladaptation (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1993; Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009). We investigated, in a sample of children at higher risk for maladaptive developmental trajectories due to early-life challenges (economic, psychosocial) within their immediate caregiving environments, the relations of disordered maternal EA (insensitivity, hostility, and passive/withdrawn behavior) with aspects of children's functioning during middle childhood (age 7). We expected, and found, coherence between maternal EA and children's functioning during the same developmental period; maternal EA during childhood was associated with (a) children's observed controlling and disorganized attachment behavior, (b) children's self-reported depressive symptoms, and (c) their teachers' reports of behavior problems in school. Moreover, we found evidence of developmental predictors from infancy that foreshadowed compromised maternal EA in childhood. Evidence of early mother–infant relationship dysfunction was manifest in early maternal hostility, disrupted communication, and infant attachment insecurity that was associated with similar constructs of maternal EA 6 years later.

EA and attachment in middle childhood

The literature demonstrates strong theoretical and empirical links between attachment and EA in infancy (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1973; Cassidy, Reference Cassidy, Cassidy and Shaver2008; Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, Beckwith and Howard2000; Ziv et al., Reference Ziv, Aviezer, Sagi and Koren-Karie2000), but these associations previously have not been established in middle childhood. The present study extended these connections to middle childhood, a developmental period that has not been fully addressed by scholars of either EA or attachment theory (Kerns, Reference Kerns, Cassidy and Shaver2008). Our results demonstrated considerable associations between children's controlling and disorganized attachment behaviors and EA behaviors of their mothers, furthering our understanding of disorganized and controlling attachment patterns in childhood and providing additional evidence for the validity of coding attachment in middle childhood (Bureau et al., Reference Bureau, Easterbrooks and Lyons-Ruth2009).

More specifically, when mothers were less sensitive in their EA during reunion following an hour-long separation in a lab setting, children showed more controlling (both punitive and caregiving) and disorganized attachment behaviors. In the operationalization of the EA Scales, the construct of maternal sensitivity focuses not only on behavioral sensitivity (e.g., appropriate behavioral responsiveness), but also on the awareness and interpretation of the “emotional climate” of the interaction. An emotionally available mother not only will acknowledge and provide appropriate regulatory assistance for negative emotions, but also shares genuinely in the experience of positive emotions with her child. In this way, connections between sensitivity and children's attachment behaviors might be expected.

When mothers acted in ways that were hostile, children were more punitive (e.g., annoyed, impatient, defiant, humiliating) and more caregiving (e.g., solicitous, organizing of the interaction, encouraging or “cheering up” their mothers) toward them. This may suggest that some children engage in matching affective states with their caregivers (e.g., maternal hostility and children's punitive behavior) in an attempt to control the relationship, whereas others take on a more solicitous role toward a hostile caregiver via efforts to appease or modify the negative affect. It also may be that mothers act in a hostile manner toward children who exhibit attempts to control the relationship (either by punitive or caregiving behavior). For some children, matching maternal hostility may lead to an escalation of the conflict; at the same time the dyad is engaged in interaction rather than disengaged. Caregiving behavior may be a way to avoid the negative escalation and may be successful in keeping the mother present in the interaction. Both strategies (punitive and caregiving) may be ways of reducing or gaining control over fear and anxiety that may be disorganizing for children; some children showed one or the other controlling behavioral strategy; some children showed evidence of both strategies in their interactions with their mothers.

Controlling child behaviors (punitive and caregiving) are thought to be styles of coping with an attachment figure who is frightened/helpless or frightening in early childhood (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Jacobvitz, Cassidy and Shaver2008; Main & Solomon, Reference Main, Solomon, Brazelton and Yogman1986). In this study, both forms of controlling behaviors were related to current maternal insensitivity and maternal hostility. Although one might expect greater punitive behaviors related to maternal hostility (i.e., returning “kind for kind” in terms of negative, humiliating, or coercive behavior) or verbal “sparring,” the link between maternal hostility and child caregiving is less obvious.

Theoretically, caregiving behavior may be understood as an attempt to placate and manage the interaction with a withdrawn or hostile parent in order to maintain some involvement or physical availability within the interaction. A child could appear like a “cheerleader,” for example, acting in ways that focused on raising maternal positive affect. This speaks to a possible adaptive role of caregiving behavior, and suggests a potential for resilient functioning among some children who have developed a strategy of controlling caregiving behaviors (Davis, Easterbrooks, & Crowell, Reference Davis, Easterbrooks and Crowell2011). This conjecture is consistent with a developmental psychopathology framework that questions “assumptions about what constitutes health or pathology” (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009).

Why would one child develop particular patterns of controlling behaviors (such and punitive and/or controlling) and another child show a different strategy or remain disorganized, without an organized strategy of control in the relationship? A developmental psychopathology perspective encourages consideration of multiple influences, alternative pathways, and the critical nature of developmental timing (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009). Different aspects of the child's “biopsychosocial ecology” at the individual (e.g., temperament, neurological organization), relational (e.g., maternal psychological health), and social context levels (e.g., kin networks, neighborhood resources) may play a role in determining the particular form of controlling behavior that a child uses in an interaction. Developing a strategy, be it punitive or caregiving behavior, or both, is an attempt to take control of the interaction in order to reduce the anxiety of unpredictable interactions. What leads a child to use caregiving behavior as a strategy to control the relationship, as opposed to punitive behavior, which also keeps the caregiver engaged through “sparring” or demeaning, hostile behavior? One of the tenets of developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009) is that there are multiple determinants of particular developmental trajectories; future research should address the issues of equifinality and multifinality (multiple pathways/multiple outcomes; Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996) related to patterns of EA and attachment.

EA and children's psychological and behavioral organization in childhood

In their review of the literature on attachment and developmental psychopathology in childhood, DeKlyen and Greenberg (Reference DeKlyen, Greenberg, Cassidy and Shaver2008) stated that “social relationships both affect and are affected by developing psychopathology in childhood (p. 637). Thus, several questions might be asked about the implications of the potential relational disturbances suggested here. Would a pattern of reciprocating hostile behavior seen in interactions with mothers marginalize children in peer interactions? Might caregiving behavior mitigate poor peer relationships or would such behaviors be rebuffed by peers? Would the bizarre, fearful, or disoriented characteristics of disorganized attachment behavior, if expressed outside of the mother–child relationship, result in alienation from teachers or peers?

Our study findings suggest that the influence of mother–child EA may extend more broadly, in children's psychological (e.g., depressive symptoms) and social (school-based behavior problems) functioning. Children themselves reported greater symptoms of depression when their mothers were more insensitive and more hostile in interactions with them. Moreover, teachers described children of mothers who were more insensitive as having more total behavior problems, and children of mothers who were more passive/withdrawn as both more externalizing and having more total behavior problems. This suggests that both children's emotional regulation and behavioral regulation may be affected by lack of EA in mother–child interactions. It is interesting that there were links between maternal EA and child-reported indicators of internalizing symptoms (e.g., depressive symptoms) but not teacher-reported internalizing behavior problems. One explanation may be that externalizing behavior problems are more evident, or problematic, in the classroom setting compared to internalizing symptoms. There is some evidence of greater agreement among multiple reporters' (mother, professional, child) views of externalizing problems compared to internalizing symptoms (Moss et al., Reference Moss, Smolla, Cyr, Dubois-Comtois, Mazzarello and Berthiaume2006). The implication for our study is that teachers may not be aware of children's somatic issues, or may interpret internalizing/depressive symptoms as temperamental shyness, or in other ways.

Mechanisms of developmental coherence seen in maternal behavior over time

A developmental psychopathology perspective (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1993; Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009) addresses the mechanisms in the dynamic systems by which children move toward and away from health and disorder. The EA Scales coding system may be well suited to identify potential mechanisms or aspects of mother–child interaction that mediate negative developmental trajectories. Positive shared affect, for example (measured in the EA Scale for maternal sensitivity), is a cornerstone of healthy relationships, beginning in, but not limited to, the early years of life (Tronick, Reference Tronick2007). The failure to provide this essential foundation of healthy socioemotional development in infancy may bode poorly for the dyad's positive engagement as the relationship develops. One of the goals of our study was to examine the extent to which maternal behaviors were stable across the 6 years from infancy to childhood assessments. Our study suggests coherence, if not continuity, in characteristics of maternal behavior over time. That is, continuity or coherence in children's developmental trajectories may be understood in relation to the extent to which the caregiving context remains stable or undergoes transformation either toward or away from support of children's healthy development.

Maternal dysfunctional behavior in interactions with their infants forecasts continued aberrant interaction during the middle childhood period. It is important to keep in mind that although the EA Scale for sensitivity applies to the adult's behavior (in this case the mother), the scales represent the dyadic nature of the interaction; extreme maternal insensitivity, hostility, and other indicators of nonoptimal interaction typically take place in concert with aberrant child behavior, as part of a dynamic system. In middle childhood interactions, mothers lacking in EA had children who acted in ways that were punitive, caregiving, and disorganized. Attachment insecurity in infancy (over 60% of the children in this sample were insecurely attached in infancy, including 40% who received insecure disorganized attachment classifications) also predicted maternal passive/withdrawn behavior and maternal hostility in childhood, suggesting a dynamic system of regulation in the mother–child relationship. Taking a developmental psychopathology perspective we assume that early risky caregiving ecologies and interactions sculpt the cortical structures of the brain that may initiate as well a “cascade of growth and function changes that . . . lead to the development of aberrant neural circuitry” (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009, p. 19) and atypical child behavioral and emotional regulation.

Early maternal disrupted or hostile behavior in infancy predicted later maternal insensitivity during middle childhood. In contrast, when other aspects of maternal and child functioning were entered in the regressions predicting more specific aspects of maternal EA (hostility and passive/withdrawn behavior), current maternal depressive symptoms, and attachment (infancy and childhood) were much more potent predictors than was early maternal behavior.

Overall, the regression analyses incorporating the significant infancy and middle childhood attachment behaviors and maternal depressive symptoms together accounted for considerable amounts of the variance in mothers' EA scores (59% variance insensitivity, 21% variance passive/withdrawn, 47% variance hostility) in middle childhood. Both early maternal behavior and children's attachment controlling and disorganized behaviors at age 7 made independent contributions to EA of mothers and their 7-year-olds.

Study limitations

Although this study is limited by a small sample size, its results are suggestive of the powerful organizing influence of early maternal–infant interactions for both later maternal behavior and children's developmental trajectories. Although we took care to locate families in the longitudinal follow-up, some of the families who could not be relocated were among those most vulnerable in infancy (e.g., had been referred for problems in mother–infant interaction). The fact that some of the most vulnerable families did not participate in the 7-year follow-up may result in a conservative view of the links between early attachment, EA, and later relationship and behavioral difficulties. Although the ecological circumstances (e.g., poverty) all of the families in our sample presented some level of risk to healthy child development (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Duncan and Brooks-Gunn2000), and a sizeable number (40%) of the families had been referred for clinical services in infancy due to concerns about the mother–infant relationship, not all families were of clinical concern. This suggests the possibility of resilient functioning in the midst of adversity and risk, and that compensatory and promotive factors may be operating at multiple levels of the child's biopsychosocial context. Further work in this area should determine whether the theoretically expected links remain in larger and more diverse longitudinal samples that would allow for causal modeling to examine developmental cascades (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Roisman, Long, Burt, Obradovic and Riley2005), and multiple pathways and potential mediation hinted at in our findings.

Conclusions

As predicted, our results revealed connections between the constructs of maternal sensitivity, attachment and EA in middle childhood. Prior studies have focused on infancy and early childhood (Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, Beckwith and Howard2000; Ziv et al., Reference Ziv, Aviezer, Sagi and Koren-Karie2000). The present study adds to this evidence by examining, specifically, controlling, and disorganized attachment behaviors in middle childhood, and documents coherent associations between EA and patterns of mother–child interaction across early childhood. Moreover, EA in the mother–child relationship was associated with children's broader adaptation outside of the relationship, in children's psychological health (depressive symptoms) and behavior problems in the school setting (with peers, classmates, and teachers).

Further, the results extend our understanding of attachment disorganization to middle childhood and provide evidence that disorganized behavior may be organized in punitive (e.g., hostile, humiliating) or caregiving (e.g., organizing/stimulating, generating positive affect) patterns or may remain disorganized (e.g., fearful, inconsistent, confused) at older ages. The study also provides important validity data that disorganized and controlling forms of behavior (punitive, caregiving) continue to be associated with nonoptimal parent–child interaction into middle childhood (Moss, Cyr, & Dubois-Comtois, Reference Moss, Cyr and Dubois-Comtois2004).

We began by speculating that EA was at the center of mother–child relationships, and that although attachment theory (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969, Reference Bowlby1973) and EA theory (Biringen & Robinson, Reference Biringen and Robinson1991; Biringen, Reference Biringen2008) may have slightly different emphases, there is a common core in focusing on the sharing and regulating of affective experiences. Having the experience of sharing positive affect or negative affect with a caregiver is a very powerful developmental organizer of both “selves” and relationships (Shonkoff & Phillips, Reference Shonkoff and Phillips2000; Tronick, Reference Tronick2007). The “affective self” (Emde, Reference Emde1983) may be the “affective relationship,” and may provide one mechanism for the developmental coherence evidenced in this investigation.