It is well established that the development of children's conduct problems begins in the first few years of life (Shaw, Reference Shaw2013). In this study, early childhood conduct problems are defined primarily by aggressive, oppositional, and disruptive behaviors. These types of behaviors are fairly normative in the toddler period, and for most children, there is a decline during early childhood (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Boivin, Nagin, Japel, Xu, Zoccolillo and Tremblay2007). However, there is a subset of children, characterized by early onset conduct problems, who do not exhibit this normative decline in early childhood and continue to engage in higher levels of conduct problems throughout childhood, and even into adolescence (Shaw, Reference Shaw2013; Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2010).

Researchers have identified a host of contextual and individual (child) factors associated with the development of early onset conduct problems (Belsky, Pasco Fearon, & Bell, Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007; Choe, Olson, & Sameroff, Reference Choe, Olson and Sameroff2013; Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, Reference Eiden, Edwards and Leonard2007; Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, Reiser, Hofer and Michalik2010; Shaw, Reference Shaw2013; Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014; Yates, Obradović, & Egeland, Reference Yates, Obradović and Egeland2010). Among the contextual factors investigated, there has been a focus on children's familial experiences, including their exposure to prenatal substance use, socioeconomic adversity (e.g., poverty, low maternal education, single parent household, and family financial stress), maternal psychological adjustment (e.g., maternal depression), and parenting (e.g., maternal sensitivity, warmth, and hostility). At the individual level, investigators have focused much of their examination on children's self-regulation skills (e.g., internalization of rules and conscience). Although the independent associations of these environmental and individual factors on conduct problems are well established, one challenge that has remained is the integration of alternative developmental process models that offer competing conceptualizations of the dynamic concurrent and longitudinal interrelations among these factors from the prenatal period through middle childhood (Bada et al., Reference Bada, Das, Bauer, Shankaran, Lester, LaGasse and Higgins2007; Luthar & Sexton, Reference Luthar and Sexton2007; Shaw, Reference Shaw2013). Moreover, researchers have noted the need for repeated assessments and prospective longitudinal studies that can be used to provide stringent empirical tests of alternative developmental process models (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007; Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, Reiser, Hofer and Michalik2010; Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Obradović and Egeland2010).

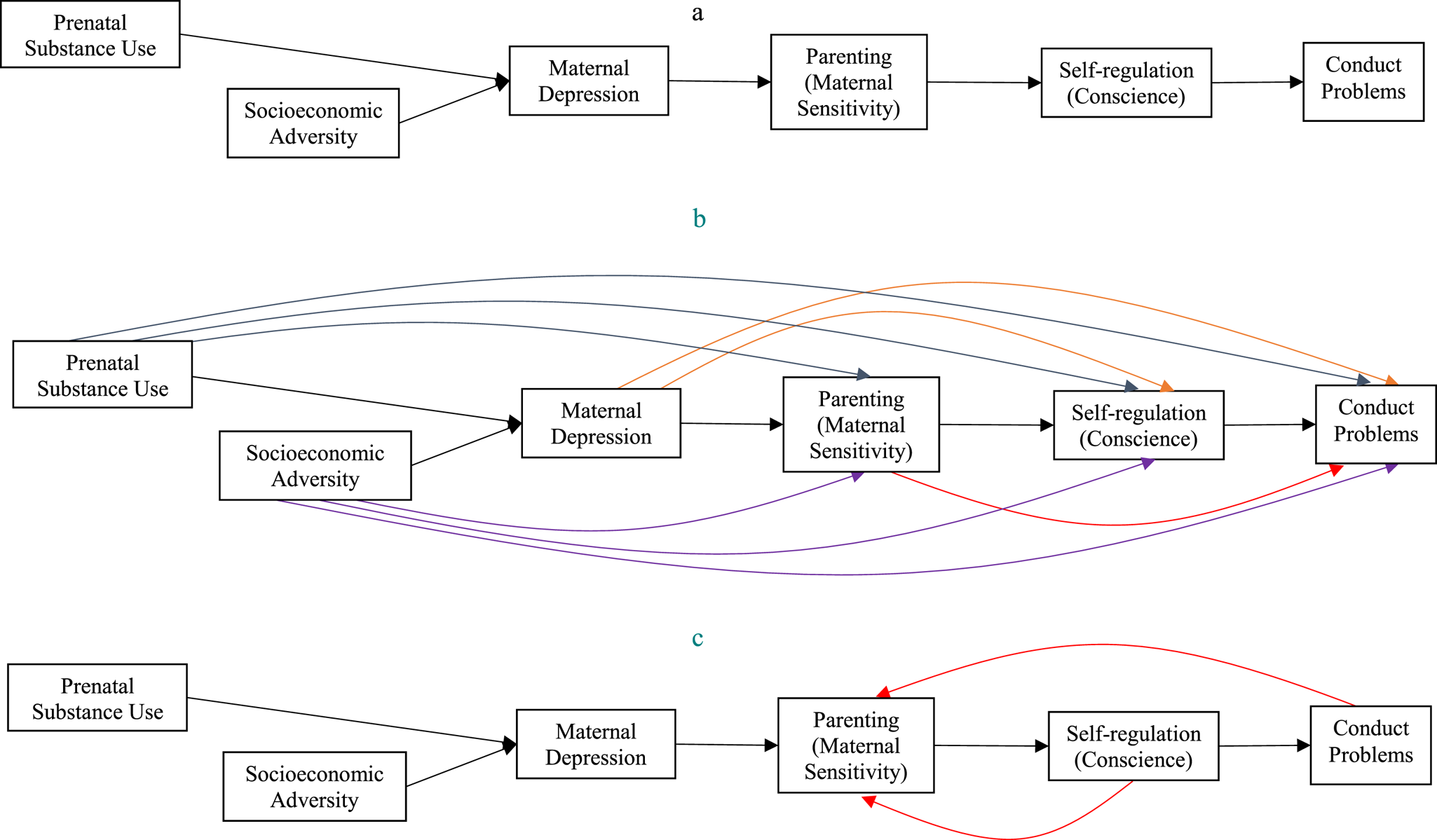

Building on this existing research, and applying a developmental psychopathology framework, the primary aims of this study were to investigate the associations among prenatal substance use, socioeconomic adversity, maternal depression, parenting processes, self-regulation, and conduct problems in a low-income, high-risk sample. Consistent with this framework, the development of childhood conduct problems is theorized to be a dynamic process characterized by continuities and discontinues over time. The developmental psychopathology framework emphasizes the need to investigate the developmental mechanisms (e.g., risk and resilience factors) that either enhance or mitigate continuities and discontinues in conduct problems, consistent with principles of equifinality. That is, that there are multiple different pathways to conduct problems (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996; Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, Reference Frick, Ray, Thornton and Kahn2014; Masten, Reference Masten2006; Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010). Consequently, we propose and evaluate empirically three alternative conceptual models: cascade (indirect or mediated), additive (cumulative), and transactional (bidirectional) effects models. These models were selected in consideration of the current state of theory and evidence on children's early conduct problems.

Implications of the Family Stress Perspective on the Associations Among Socioeconomic Adversity, Maternal Depression, and Parenting

There is a large body of evidence which suggests that the socioeconomic disadvantages associated with low family income and poverty collectively compromise adaptive parenting styles and place children at risk for poorer developmental outcomes (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, Reference Brooks-Gunn and Duncan1997; Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014; Votruba-Drzal, Reference Votruba-Drzal2006). Using a cumulative risk approach, socioeconomic adversity was characterized by low maternal education, single parenthood, low family income, meal unpredictability, and financial stress. A cumulative risk approach was used in this study for several reasons. First, aggregating multiple risk factors can more accurately ascertain the severity of socioeconomic adversity and has more predictive power than focusing on the effects of any single indicator (Evans, Reference Evans2004; Evans, Li, & Whipple, Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013). Second, with respect to low-income, urban populations, these risks tend to co-occur and rarely exist in isolation (Wilson, Hurtt, Shaw, Dishion, & Gardner, Reference Wilson, Hurtt, Shaw, Dishion and Gardner2009). Third, subjective measures of socioeconomic adversity and material hardship, which ascertain the perceptions and experiences of low-income families, may identify individual differences that are not accounted for in measures of family income that tend to have less variability in low-income samples (Barnett, Reference Barnett2008; Gershoff, Aber, Raver, & Lennon, Reference Gershoff, Aber, Raver and Lennon2007).

According to the family stress perspective, parents who face socioeconomic adversity are likely to experience a multitude of economic pressures (e.g., inability to purchase goods and services, employment instability, single incomes, and low wages), which collectively contribute to a stressful family environment and their ability to provide sensitive, warm, and consistent parenting styles (Conger & Donnellan, Reference Conger and Donnellan2007; Conger et al., Reference Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd and Brody2002). Although findings consistent with the family stress perspective have been ubiquitous among rural and urban populations, and across childhood and adolescence (Belsky & Jaffee, Reference Belsky, Jaffee, Cicchetti and Cohen2006; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, Gipson, Campbell and Westerholm2006; Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014), this is a particularly compelling perspective when applied to early childhood development in low-income urban contexts. During the early childhood years, children's daily experiences are strongly impacted by the quality of their parental care and their parent–child interactions. Compared to older children and adolescents, young children have less direct exposure to the possible adverse effects of living in impoverished neighborhoods. Therefore, the cumulative effects of socioeconomic adversity are more likely to be mediated by its impact on the family context (Ingoldsby & Shaw, Reference Ingoldsby and Shaw2002; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn2000). Moreover, these associations are likely to be exacerbated among families living in urban contexts because of their greater risk for experiencing multiple forms of socioeconomic adversity (Trentacosta et al., Reference Trentacosta, Hyde, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner and Wilson2008; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Hurtt, Shaw, Dishion and Gardner2009; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Obradović and Egeland2010).

Conceptualizations of the family stress perspective have typically postulated a sequential process model (Conger & Donnellan, Reference Conger and Donnellan2007; Conger et al., Reference Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd and Brody2002). In the first part of this sequence, socioeconomic adversity has been theorized to most directly impact maternal psychological adjustment, and in particular, maternal depression (Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014). In the second part, maternal depression is theorized to increase harsh parenting, and impede sensitive and warm parenting practices. Thus, the impact of maternal depression on children's conduct problems is accounted for via its influence on parenting (Campbell, Matestic, von Stuffenberg, Mohan, & Kirchner, Reference Campbell, Matestic, von Stauffenberg, Mohan and Kirchner2007; Goodman & Gotlib, Reference Goodman and Gotlib1999; McCabe, Reference McCabe2014). Empirical findings in support of the family stress perspective have been garnered from a number of studies based on heterogeneous samples with respect to race, ethnicity, and developmental periods (Gershoff et al., Reference Gershoff, Aber, Raver and Lennon2007; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, Gipson, Campbell and Westerholm2006; Jackson, Brooks-Gunn, Huang, & Glassman, Reference Jackson, Brooks-Gunn, Huang and Glassman2000; Linver, Brooks-Gunn, & Kohen, Reference Linver, Brooks-Gunn and Kohen2002; Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd, Reference Mistry, Vandewater, Huston and McLoyd2002; Rijlaarsdam et al., Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, van der Ende, Hofman, Jaddoe, Mackenbach and Tiemeier2013; Shelleby et al., Reference Shelleby, Votruba-Drzal, Shaw, Dishion, Wilson and Gardner2014; Yeung, Linver, & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Yeung, Linver and Brooks-Gunn2002).

In addition to the previously postulated sequential process model (i.e., socioeconomic adversity → maternal adjustment → parenting → child conduct problems), the reformulated family stress perspective proposed by Shaw and Shelleby (Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014) indicates that there is an independent effect of maternal adjustment on child conduct problems. In other words, maternal maladjustment, and maternal depression in particular, increases children's risks for conduct problems, in addition to its effects on parenting (Campbell, March, Pierce, Ewing, & Szumowski, Reference Campbell, March, Pierce, Ewing and Szumowski1991; Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Shaw, Connell, Gardner, Weaver and Wilson2008, Shaw, Bell, & Gilliom, Reference Shaw, Bell and Gilliom2000; Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, Reference Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson and Gardner2009; Shelleby et al., Reference Shelleby, Votruba-Drzal, Shaw, Dishion, Wilson and Gardner2014). There are several processes by which maternal depression may be associated with children's conduct problems, which are not accounted for by parenting effects, per se. For instance, maternal depression may increase children's exposure to marital or relationship conflicts and other contextual stressors. In addition, children of depressed mothers are at greater risk for having biological vulnerabilities to conduct problems (Cummings, Keller, & Davies, Reference Cummings, Keller and Davies2005; Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014).

Parental Socialization of Children's Self-Regulation (Conscience) and Conduct Problems

Integral to the family stress perspective is the premise that parenting processes are intricately linked to children's conduct problems (Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014). Expanding on this premise, this study incorporates research on the parental socialization of children's self-regulation to elucidate the processes by which parenting practices (maternal sensitivity, warmth, and low harshness) are associated with conduct problems via their influence on the development of children's conscience.

According to parental socialization perspectives, maternal sensitivity and warmth play an important role in the development of multiple facets of children's self-regulation skills across the early childhood years (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007; Colman, Hardy, Albert, Raffaelli, & Crockett, Reference Colman, Hardy, Albert, Raffaelli and Crockett2006; Eiden et al., Reference Eiden, Edwards and Leonard2007; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Zhou, Spinrad, Valiente, Fabes and Liew2005; Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, Reference Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg and Lukon2002). Self-regulation is a cornerstone of social–emotional development in early childhood (Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, Reference Kochanska, Coy and Murray2001). It consists of multiple interrelated domains, and developmentally, entails a shift from external monitoring to internal behavioral and emotional control (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad and Eggum2010; Kochanska, Reference Kochanska1995; Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan2006). The current investigation focused on the development of children's conscience as one of the primary facets of self-regulation in early childhood. The development of conscience in early childhood consists of multiple interrelated components including moral conduct, emotions, and cognitions (Aksan & Kochanska, Reference Aksan and Kochanska2005; Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan2006). In the current study, we focus more specifically on one of these components, moral conduct, primarily defined by internalization of rules (referred to as internalization), that is, a child's ability to comply with rules in the absence of direct supervision or surveillance (Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan2006). Internalization has been theorized to develop gradually throughout early childhood, and emerges from children's willingness to enthusiastically and cooperatively comply with maternal requests (i.e., committed compliance; Kochanska, Reference Kochanska1995; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Coy and Murray2001), as well as their temperamental ability to control their behaviors, impulses, and emotions (i.e., effortful control; Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad and Eggum2010; Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Eisenberg, William and Lerner2006).

Research by Kochanska et al. has been pivotal in conceptualizing the associations between parental socialization processes and conscience. They propose that when parent–child interactions are characterized by sensitivity (i.e., warmth, trust, security, mutual bond, expectations of reciprocity, and shared affective positivity), children become more intrinsically motivated to comply with their parents’ demands, even in the absence of direct supervision (Kochanska, Reference Kochanska1995; Kochanska, Forman, Aksan, & Dunbar, Reference Kochanska, Forman, Aksan and Dunbar2005; Kochanska, & Murray, Reference Kochanska and Murray2000).

In addition to sensitivity, harsh parenting and hostile parent–child interactions have also been found to predict children's self-regulation and conduct problems (Barnett; Reference Barnett2008; Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, Reference Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken and Deković2006; Pardini, Fite, & Burke, Reference Pardini, Fite and Burke2008; Smith, Calkins, Keane, Anastopoulos, & Shelton, Reference Smith, Calkins, Keane, Anastopoulos and Shelton2004). When harsh parenting practices foster children's reactive resentment and anger, children are more likely to devalue parent's rules and expectations of appropriate conduct, thereby increasing their risks for conduct problems (Gilliom et al., Reference Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg and Lukon2002; Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan2006; Kochanska, Aksan, & Nichols, Reference Kochanska, Aksan and Nichols2003; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Forman, Aksan and Dunbar2005). Furthermore, harsh parenting provides a model for children to use similar interaction styles with peers and siblings, increasing their risks for conduct problems and aggression (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Spieker, Vandergrift, Belsky and Burchinal2010; Combs-Ronto, Olson, Liunkenheimer, & Sameroff, Reference Combs-Ronto, Olson, Lunkenheimer and Sameroff2009; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Bell and Gilliom2000; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, Reference Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby and Nagin2003; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, Winter and Patterson2014). Taken together, there is evidence to suggest that both maternal sensitivity and harshness collectively predict children's conscience and conduct problems. Consistent with this reasoning, to evaluate the overall parent–child relationship, we aggregated multiple parenting practices including high maternal sensitivity and low harshness. For ease of presentation, this composite measure is referred to as maternal sensitivity.

Expanding on studies that have applied the family stress perspective to investigate the direct associations between parenting and conduct problems, investigators who have applied parental socialization perspectives have conceptualized a sequential (indirect) pathway, such that the effects of parenting on conduct problems are mediated by children's self-regulatory skills (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad and Eggum2010). The theoretical rationale for this sequential pathway is based on the premise that adaptive parenting practices enable children to effectively internalize and comply with external rules and standards, and exhibit moral conduct. In turn, children who have developed adaptive self-regulatory skills will be able to apply their internalized norms (conscience) to prohibit them from engaging in conduct problems (Kochanska, Barry, Aksan, & Boldt, Reference Kochanska, Barry, Aksan and Boldt2008).

Several studies have investigated the mediational role of self-regulation by using rigorous full-panel research designs to control for concurrent associations and stability effects. However, most have focused on effortful control or other constructs of self-regulation (e.g., inhibitory or attentional control) and have not considered the development of conscience in low-income samples (e.g., Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007; Choe et al., Reference Choe, Olson and Sameroff2013; Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, Reiser, Hofer and Michalik2010; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Barry, Aksan and Boldt2008; Spinrad et al., Reference Spinrad, Eisenberg, Gaertner, Popp, Smith, Kupfer and Hofer2007; Valiente et al., Reference Valiente, Eisenberg, Spinrad, Reiser, Cumberland and Liew2006; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Obradović and Egeland2010). Consequently, this study sought to contribute to this line of inquiry by further investigating whether and how conscience mediates the associations between maternal sensitivity and conduct problems across early childhood in the context of socioeconomic adversity.

Prenatal Substance Use

Considering that early childhood is a sensitive developmental period for the formation of conscience (Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan2006; Kochanska & Thompson, Reference Kochanska, Thompson, Grusec and Kuczynski1997) and early onset conduct problems (Shaw, Reference Shaw2013), applications of the family stress and parental socialization perspectives have typically focused on this developmental period. However, investigators have also noted the need for conceptualizing and testing developmental models that explicate how the sequelae of early conduct problems are set in motion in the prenatal period and progress throughout infancy, toddlerhood, and into early childhood (Shaw, Reference Shaw2013). Maternal prenatal substance use may be associated with maternal psychological symptoms, including maternal depression, and lower maternal sensitivity in infancy and toddlerhood, which in turn predict early conduct problems and conscience (Eiden, Granger, Schuetze, & Veira, Reference Eiden, Granger, Schuetze and Veira2011; Eiden, Godleski, Schuetze, & Colder, Reference Eiden, Godleski, Schuetze and Colder2015; Maughan, Taylor, Caspi, & Moffitt, Reference Maughan, Taylor, Caspi and Moffitt2004). Thus, in addition to the processes postulated in the family stress and parental socialization perspectives, prenatal substance use may pose as an additional stressor that places children at risk for early onset conduct problems. Using a sample of families with high rates of substance use, one of the primary aims of this study was to propose and test a series of integrative conceptual models on how prenatal substance use, socioeconomic adversity, maternal depression and sensitivity, and children's conscience are associated with the development of early onset conduct problems.

Developmental Cascade Model

Consistent with the assertions of the family stress perspective, we hypothesized a model (see Figure 1a) such that socioeconomic adversity was associated with greater maternal depression. Furthermore, by more explicitly integrating research on prenatal substance use, we hypothesized that maternal substance use was also associated with maternal depression. In turn, the associations of prenatal substance use and socioeconomic adversity on lower maternal sensitivity are hypothesized to be mediated by maternal depression. Integrating the family stress perspective with research on the parental socialization of children's self-regulation, we hypothesized that lower maternal sensitivity would be associated with decreases in children's conscience, which in turn predicts conduct problems. Collectively, this sequence of hypothesized associations was conceptualized as a developmental cascade model. Cascade models are predicated on the assumption that the determinants of conduct problems include a set of distal and proximal predictors. Over time, distal processes predict more proximal processes, which have a more direct impact (i.e., mediating effect) on the outcome (Dodge, Greenberg, Malone, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, Reference Dodge, Greenberg and Malone2008).

Figure 1. Alternative conceptual models depicting (a) developmental cascade, (b) additive, and (c) transactional processes.

Additive Effects Models

In consideration of extant theory and evidence, there are alternative conceptual models that also warrant further investigation, and may provide unique insights. Moreover, by comparing multiple alternative models, it is possible to have greater confidence in ruling out competing hypotheses. Additive (or cumulative) effects models are predicated on the assumption that the causal determinants of an outcome include a set of multiple predictors, each of which accounts for unique variance (Ladd, Reference Ladd2006). In contrast to the cascade model, which postulates a sequential (i.e., fully mediated) effect from more distal to proximal factors, the additive model stipulates that the effects of prenatal substance use, socioeconomic adversity, maternal depression, and maternal sensitivity each contribute in unique ways to the development of conscience and conduct problems.

Using the additive model framework, four hypotheses were tested empirically. First, with respect to prenatal substance use, it is plausible that substance using mothers engage in less sensitive parenting styles that are not accounted for via an indirect effect through maternal depression (Eiden et al., Reference Eiden, Granger, Schuetze and Veira2011). Furthermore, there may be adverse effects of prenatal substance use on children's conscience or conduct problems not accounted for by maternal depression or sensitivity (Bada et al., Reference Bada, Das, Bauer, Shankaran, Lester, LaGasse and Higgins2007; Maughan et al., Reference Maughan, Taylor, Caspi and Moffitt2004). Thus, an additive model was hypothesized that included effects from prenatal substance use to sensitivity, conscience, and conduct problems (see Figure 1b). Second, with respect to socioeconomic adversity, evidence gleaned from several studies indicates that it is predictive of maternal sensitivity (beyond its indirect effects via maternal depression), and that it is predictive of children's conscience and conduct problems (beyond its indirect effects via maternal depression and sensitivity; Gershoff et al., Reference Gershoff, Aber, Raver and Lennon2007; Shelleby et al., Reference Shelleby, Votruba-Drzal, Shaw, Dishion, Wilson and Gardner2014; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Obradović and Egeland2010; Yeung et al., Reference Yeung, Linver and Brooks-Gunn2002). Thus, to test for the hypothesized additive effects of socioeconomic adversity, we assessed its effects on maternal sensitivity, conscience, and conduct problems. Third, with respect to maternal depression, reformulations of the family stress perspective postulate that it has unique predictive effects on conduct problems, in addition to its indirect effects via parenting (Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014), and it may also contribute to lower self-regulation (Choe, Shaw, Brennan, Dishion, & Wilson, Reference Choe, Shaw, Brennan, Dishion and Wilson2014). Thus, to test these assertions empirically, we assessed the effects of maternal depression on children's conduct problems and conscience. Fourth, with respect to parenting, it is plausible that lower levels of sensitivity reinforce conduct problems, in addition to how they undermine children's self-regulatory skills (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007; Campbell, Pierce, March, Ewing, & Szumowski, Reference Campbell, Pierce, March, Ewing and Szumowski1994; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Winslow, Owens, Vondra, Cohn and Bell1998). Consistent with this viewpoint, we examined the effects of maternal sensitivity on conduct problems.

Transactional Effects Models

Although the family stress and parental socialization perspectives have often been conceptualized and tested as cascade models, researchers have also proposed transactional perspectives pertaining to early conduct problems (Shaw & Bell, Reference Shaw and Bell1993; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Bell and Gilliom2000; Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, Reference Shaw, Keenan and Vondra1994). Transactional perspectives postulate that development occurs as a function of bidirectional feedback between a child's individual characteristics and his or her contextual experiences across time (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti, Toth, Luthar, Burack, Cicchetti and Weisz1997; Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff and Sameroff2009).

Transactional perspectives pertaining to early conduct problems are congruent with coercion theory, a social-interactional framework focusing on the critical role of hostile parent–child interactions (Patterson, Reference Patterson, Reid, Patterson and Snyder2002; Scaramella & Leve, Reference Scaramella and Leve2004; Shaw & Bell, Reference Shaw and Bell1993; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Bell and Gilliom2000). According to this framework, children's early conduct problems foster a power struggle in which parents respond with increasingly aversive power assertion techniques and hostility. These techniques, however, are met with children's noncompliance and opposition and an escalation in their conduct problems. Over time, this coercive interaction pattern undermines children's self-regulation and willingness to internalize parental rules and expectations, and leads to sustained and stable conduct problems throughout childhood (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007; Combs-Ronto et al., Reference Combs-Ronto, Olson, Lunkenheimer and Sameroff2009; Pardini et al., Reference Pardini, Fite and Burke2008; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Bell and Gilliom2000; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Calkins, Keane, Anastopoulos and Shelton2004, Reference Smith, Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, Winter and Patterson2014).

With respect to developmental timing, researchers have theorized that coercive parent–child interactions are initiated in the early childhood years, and thus are a primary mechanism by which children exhibit conduct problems at school entry (Patterson, Reference Patterson, Reid, Patterson and Snyder2002; Shaw & Bell, Reference Shaw and Bell1993; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, Winter and Patterson2014). However, the empirical evidence has been equivocal with respect to the specific timing of these effects. Using full-panel repeated-measures designs, Eisenberg and colleagues did not find support for transactional effects during the early childhood years when examining the longitudinal bidirectional associations between parenting and children's conduct problems from 18, 30, and 42 months old (Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggunm, Silva, et al. Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, Reiser, Hofer and Michalik2010) and from ages 2, 3, and 4 years old (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Zhou, Spinrad, Valiente, Fabes and Liew2005). Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, Winter and Patterson2014) found that children's conduct problems predicted coercive parent–child interactions from ages 4 to 5 years old, but not from ages 2 to 3, or 3 to 4. Belsky et al. (Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007) reported that children's conduct problems predicted declines in maternal sensitivity from 4.5 years old to Grade 3 (~8 years old) and from Grade 1 to Grade 5 (~6 to 10 years old). Collectively, one implication of these findings is that provocative child effects (on parenting) appear to become more pronounced during the later parts of early childhood and the transition to middle childhood.

Building on these existing studies, we assessed the bidirectional effects of children's conscience and conduct problems on maternal sensitivity (see Figure 1c). To examine the potential timing of such effects, we assessed whether children's conscience and conduct problems were associated with maternal sensitivity during the transition to early childhood (i.e., from ages to 2 to 4 years old) and the transition to kindergarten (i.e., from 4 years old to kindergarten aged). In line with extant findings, we hypothesized that these associations would be more pronounced during the transition to kindergarten.

Study Aims

The overarching aims of this study were to investigate the prospective and dynamic longitudinal associations among prenatal substance use, socioeconomic adversity, maternal depression and sensitivity, and children's conscience and conduct problems from infancy to middle childhood using a multimethod, multi-informant, repeated-measures design with a low-income, high-risk sample. More specifically, six waves of data were used, including assessments of the prenatal period, infancy (i.e., child was 1 month old), toddlerhood (2 years old), early childhood (4 years old), kindergarten aged, and middle childhood (Grade 2). These assessment periods were selected to assess continuities and changes as children made significant developmental transitions. Across these developmental periods, three alternative models, including the developmental cascade, additive, and transactional models, were specified using path analysis and compared using nested model tests. Of note, when testing the alternative conceptual models, it was necessary to also consider stability effects of constructs (across time) and concurrent associations among the variables (within time). Consequently, a repeated-measures design was used such that most measures were assessed at multiple time points.

Method

Participants and procedures

The sample consisted of 216 mother–child dyads (49% boys) participating in an ongoing longitudinal study. All families were recruited from two urban hospitals serving a predominantly African American low-income population. All mothers were screened after delivery to identify a sample of participants with high rates of prenatal cocaine use. Exclusionary criteria consisted of maternal age less than 18 years, use of illicit substances other than cocaine or marijuana during pregnancy, plural births, and significant medical problems in the infant. Once a family was recruited into the cocaine group, the closest matching non-cocaine group family was recruited. Families were matched on maternal education, maternal race and ethnicity, and infant gender. Of mothers recruited who agreed to participate in the study, 116 had some level of prenatal cocaine use, and the remaining 100 were part of a demographically similar comparison group of non-cocaine exposed children. Compared to those who were eligible but not enrolled, mothers who participated were more likely to be in the cocaine group, between 18 and 25 years of age, and to have a high school or below high school education. There were no other differences on any demographic variables between those who participated and those who were eligible, but not enrolled. For a more detailed explanation of sampling procedures, see Eiden, Coles, Schuetze, & Colder (Reference Eiden, Coles, Schuetze and Colder2014). Participating mothers ranged in age from 18 to 42 years (M = 29.78; SD = 5.46). Approximately 72% of mothers indicated being African American, 16% Caucasian, and 10% Hispanic or Latino. Most were receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (76%) at the time of their first laboratory visit, and were single (66%).

About 2 weeks after delivery, mothers were contacted and scheduled for their first laboratory visit, which took place at the time that their infant was approximately 4–8 weeks old (i.e., 1-month assessment). Additional follow-up visits occurred every 6 months until the child was 2 years old, and annually at ages 3 and 4 years old. As children became school aged, the research design shifted from age-based to grade-based assessments to capture the developmental transition to kindergarten. Accordingly, additional follow-up assessments occurred when children began kindergarten (approximately 5 years old for most participants) and again in second grade (approximately 7 years old). Upon kindergarten entry, consent was obtained from the participating children's teachers, who provided behavioral assessments. Laboratory visits consisted of a combination of maternal interviews, observations of mother–child interactions, and laboratory assessments. Biological mothers were interviewed at the 1-month assessment in order to obtain accurate information about prenatal substance use. All subsequent assessments were conducted with the primary caregiver who had legal guardianship of the child at that time, although for ease of presentation the terms mother and maternal are used throughout the manuscript when referring to the primary caregiver.

Measures

Maternal prenatal substance use

Prenatal substance use was measured by aggregating prenatal cocaine, alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use based on a combination of self-report, urine toxicology, and hair analysis. To obtain self-reported substance use, trained interviewers administered the Timeline Follow-Back Interview (TLFB; Sobell, Sobell, Klajmer, Pavan, & Basian, Reference Sobell, Sobell, Klajmer, Pavan and Basian1986). Participants were provided a calendar and asked to identify events of personal interest (i.e., holidays, birthdays, and vacations) as anchor points to aid recall. The TLFB yielded data about the number of days of cocaine use, number of joints smoked, number of cigarettes smoked, and number of standard drinks per trimester during pregnancy. The TLFB is established as a reliable and valid method of obtaining longitudinal data on substance-use patterns, has good test–retest reliability, and is highly correlated with other intensive self-report measures (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Burgess, Sales, Whiteley, Evans and Miller1998). To supplement the self-report measure, prenatal substance use (cocaine, marijuana, opiates, PCP, and methamphetamines) was also measured via urine and hair samples (see Eiden, Coles, Schuetze, & Colder, Reference Eiden, Coles, Schuetze and Colder2014 for additional details on how samples were tested). Proportion scores were computed to indicate the amount of cocaine that was detected in these samples. A composite prenatal substance variable was then computed by aggregating across substances, trimesters, and data source, such that higher scores reflected higher levels of prenatal cocaine, alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use.

Maternal depression

The Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1993) is a shortened version (53 items) of the Symptom Checklist 90-R and is a widely used mental health screening measure in a variety of clinical and research settings. The 6-item depression subscale was used from the 1-month and 2-year assessments. Items included “feeling lonely,” “feeling blue,” “feeling hopeless about the future,” “feelings of worthlessness,” “thoughts of ending your life,” and “feeling no interest in things.” Respondents provided answers on a 5-point Likert type scale (from not at all to extremely) with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. This measure had adequate reliability (α = 0.82 at 1 month, α = 0.89 at 2 years). Although the mean subscale scores were used in subsequent analyses, for descriptive purposes, T scores were also computed to assess the degree of clinical pathology in the sample. Results indicated that 18.1% and 15.7% of mothers exceeded the cutoff score for clinical diagnoses at the 1-month and 2-year assessments, respectively.

Socioeconomic adversity

Socioeconomic adversity was assessed at the 1-month and age 2 waves based on a composite variable consisting of low maternal education, single parenthood, low family income, and meal and money unpredictability using an aggregation procedure proposed by Moran et al. (Reference Moran, Lengua, Zalewski, Ruberry, Klein, Thompson and Kiff2017). Mothers were asked to report their highest level of education, and a dichotomized variable was created to reflect those who had not completed high school (ranging from 40% at the 1-month assessment to 31% at the age 2 assessment). Single parenthood was assessed by asking mothers to report their living arrangements in the past month. Those who indicated not living with a sexual partner or the biological father of the child were coded as being single (ranging from 67% at the 1-month assessment to 60% at the age 2 assessment). Low family income was computed by dividing each family's total income (including public assistance) by the total number of family members this income supported. This variable was reverse-coded so that higher scores reflected lower income. A proportion score was then created by dividing each family's income to the highest reported income. Meal and money unpredictability were assessed when children were 2 years old using the 5-item meal unpredictability (α = 0.73) and 3-item money unpredictability (α = 0.66) subscales from the Family Unpredictability Scale (Ross & Hill, Reference Ross and Hill2000). For each subscale, the average score across all items was computed, and proportion scores were created by dividing by the maximum scores. To create composite socioeconomic adversity measures, across these indicators, an average score was computed based on the combination of the dichotomized and proportion scores.

Parenting (maternal sensitivity, warmth, and harshness)

At the age 2, 4, and kindergarten waves, a composite scale was formed that tapped indicators of maternal sensitivity, warmth, and harshness (reverse-scored). Using behavioral observations during laboratory assessments, at child ages of 2 and 4 years, mothers were asked to interact with their children as they normally would at home for 10 min (i.e., a free-play task). At kindergarten age assessments, mothers and children were asked to work on a craft project (decorating a picture frame) for 20 min (Kochanska & Murray, Reference Kochanska and Murray2000). These interactions were coded using the Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment (Clark, Reference Clark1999; Clark, Hyde, Essex, & Klein, Reference Clark, Hyde, Essex and Klein1997; Clark, Paulson, & Conlin, Reference Clark, Paulson, Conlin and Zeanah1993) by two sets of coders blind to any information regarding the families. These coders were trained on the Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment and coded maternal behavior across the entire free-play or craft project sessions. Coders used a collection of 5-point rating scales to assess the intensity, duration, and frequency of specific behaviors (i.e., a score of 1 being equal to a complete lack of, or minimal evidence for, the quality being rated, and a score of 5 being equal to an intense, consistent, or extreme reaction). Interrater reliability conducted on a random selection of 11% to 14% of the tapes ranged from r = .98 at 2 years old to r = .94 at kindergarten age. Maternal sensitivity was assessed by 11 indicators tapping tone of voice, positive affect and mood, contingent responsivity, quality of positive verbalizations, connectedness, and quality of parental involvement. Harshness was assessed by 6 indicators that reflected angry and hostile tone of voice and mood, negative affect, disapproval or criticism, rigidity, and intrusiveness (reverse coded so that higher scores indicated lower harshness). These indicators were averaged into subscale scores (M = 3.56 to 3.78, SD = 0.77 to 0.85, range = 1.75 to 5.00 for maternal sensitivity, and M = 3.78 to 4.56, SD = 0.50 to 0.85, range = 1.67 to 5.00 for maternal harshness). To create a composite measure at each age, the average scores for maternal sensitivity and low harshness were aggregated (α ranging from 0.90 at 2 years old to 0.97 at kindergarten age).

Self-regulation (conscience)

At ages 2 and 4, assessments of child internalization and conscience were conducted according to the paradigm developed by Kochanska and colleagues (Kochanska, Reference Kochanska1995; Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan1995; Kochanska, Padavich, & Koenig, Reference Kochanska, Padavich and Koenig1996). Mothers were instructed to show their child a shelf with attractive objects when they entered the observation room and instruct the child to not touch those objects. Mothers were told that they could repeat this prohibition and/or take whatever actions they would normally to keep their child from touching these prohibited objects during the hour-long session that followed. About an hour into the observation session, the experimenter asked the mother to move to the front of the observation room, and a screen, dividing the room in half, was partially closed so that the parent and the child were unable to see each other. In the absence of parental surveillance, children's internalization of the maternal directive not to touch the objects on the prohibited shelf was assessed during a 12-min observational paradigm. During the first 3 min, the child was left alone and asked to perform a task (sorting cutlery). A research assistant unfamiliar to the child came in and played with the prohibited objects with obvious enjoyment for 1 min and then left the room. Prior to leaving, the research assistant wound up a music box, started the music, and replaced it on the shelf. The child was left with the cutlery sorting for the next 8 min. The child's behavior was coded for every 15-s interval according to the coding criteria developed by Kochanska and Aksan (Reference Kochanska and Aksan1995), consisting of 6-point rating scales with 0 (playing with prohibited objects in a “wholehearted,” unrestrained manner) to 6 (sorting cutlery). The final composite score for internalization was computed by taking the average rating across the intervals, and it was then standardized.

Assessments of child conscience (moral conduct) at kindergarten age were conducted according to the “throwing game” paradigm developed by Kochanska, Aksan, and Koenig (Reference Kochanska, Aksan and Koenig1995). Compared to the internalization task used at younger ages, this assessment is more challenging and developmentally appropriate for this age group (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Aksan and Koenig1995). The experimenter invited the child to play a game in which they attempted to throw soft balls onto a target to win prizes. The experimenter described the rules, which required the participants to stand on a mat, face away from a target, and throw the balls with their nondominant hand, making it impossible to hit the target. The experimenter emphasized the importance of following these rules, and not cheating, and left the room to get the prizes. While the experimenter was away, the child's behaviors were recorded and later coded in 3-s segments for three behaviors: latency to cheat was computed as the amount of time it took for the child to begin cheating in the game, rule compatible conduct consisted of the total number of segments in which the child followed the rules, and extent of cheating consisted of the total number of segments in which the child performed a behavior that was not consistent with the stated rules. Scores in each category were standardized (after reverse coding the extent of cheating behaviors), and an average score was computed with higher scores reflecting higher levels of conscience. Conscience was coded by two independent coders blind to other information about families, and interrater reliability was computed for 15% of the sample at 2 years old, 10% of the sample at 4 years old, and 15% of the sample at kindergarten age. Interrater reliability for internalization and conscience was high (intraclass correlation coefficient of .99 at 2 and 4 years old, and kindergarten age).

Child conduct problems

Maternal reports of child conduct problems were obtained at 2 and 4 years of age using the 1.5- to 5-year version of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1992). Participants responded to 100 items on a 3-point response scale ranging from not true to very true. The 19-item aggressive behaviors subscale was used, which demonstrated adequate reliability (α = 0.92 at 2 years and 4 years). This subscale includes items that assess aggressive, disruptive, and oppositional behaviors. At kindergarten and Grade 2, mother and teacher reports of aggression were obtained using the Behavior Assessment System for Children (Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus2002) aggression subscale. The 11-item mother report demonstrated adequate reliability (α = 0.87 in kindergarten and α = 0.84 in Grade 2), as did the 10-item teacher report (α = 0.93 in kindergarten and α = 0.94 in Grade 2). For descriptive purposes, the degree of clinical pathology in the sample was evaluated. Although clinical diagnoses of young children tend to be rare, roughly and 5.3% and 4.3% of children exceeded the clinical cutoff on the Child Behavior Checklist at the 2-year and 4-year assessments, respectively. About 11.7% and 27.1% of children in kindergarten, and 22.8% and 40.5% of children in Grade 2 exceeded the cutoff on the Behavior Assessment System for Children based on mother and teacher reports, respectively.

Non-biological caretaker

Following the 1-month assessment, all subsequent assessments were conducted with the primary caregiver who had legal guardianship of the child at that time. In most cases when the primary caretaker of the child was no longer the biological mother, this occurred by the time the child was 2 years old. Between birth and 2 years, about 15% (n = 33) of children had a non-biological primary caretaker at some point. At age 2 years, 5 children were under the care of a relative who was the non-biological parent, and 15 had a foster parent. To control for the possible effects of the primary caretaker changing, a dummy-coded covariate was created (biological parent = 0, non-biological caretaker = 1).

Data analysis plan

First, preliminary analyses were performed to estimate missing data, descriptive statistics, and bivariate correlations. Second, path analysis was used to estimate and compare the hypothesized alternative models. These models were specified in Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017) using maximum likelihood with robust standard errors estimation. Model fit was assessed by multiple fit indices, including the root mean square error or approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and comparative fit index (CFI).

Across all of the alternative models, the stability effects of variables were measured over time including the stability of socioeconomic adversity and maternal depression in infancy and toddler years (1 month to age 2), maternal sensitivity (from age 2 to kindergarten), conscience (from age 2 to kindergarten), and conduct problems (from age 2 to Grade 2). Starting in kindergarten, teacher reports of child conduct problems were specified separately, and in addition to, maternal reports of conduct problems. Although it would have been interesting to include additional repeated measures for socioeconomic adversity and maternal depression in early childhood, the decision was made to not include these variables to allow for a more parsimonious model with fewer parameters. Moreover, this decision was consistent with the temporal ordering of effects described in the conceptual model in Figure 1a. In addition to stability effects, covariances and residual covariances (correlations) were specified for all variables measured within the same wave.

By using repeated measures over time, it was also possible to specify additive and transactional effects, and to empirically evaluate these alternative models using nested model comparisons. Because the alternative models were nested, Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square difference testing was used (Satorra, Reference Satorra, Heijmans, Pollock and Satorra2000) to compare the hypothesized models and to determine the most parsimonious (optimal) model. If this test statistic is statistically significant, it indicates that the additional parameters in the model resulted in an improvement in model fit. To empirically assess for mediated (indirect) effects, the model indirect command in Mplus was used with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals based on 5,000 estimations. If the 95% confidence intervals did not include zero, then a statistically significant mediation effect was supported (MacKinnon, Reference MacKinnon2008).

Although gender and having a non-biological caretaker were not explicitly included in the conceptual models, these variables were treated as covariates in each model. Due to concerns of statistical power, it was not possible to test multigroup models to compare differences across groups based on these two variables. However, it was possible to assess some of the effects of these variables by including them as covariates, and follow-up analyses were performed to further investigate the potential influence of having a non-biological caretaker.

Results

Preliminary analyses

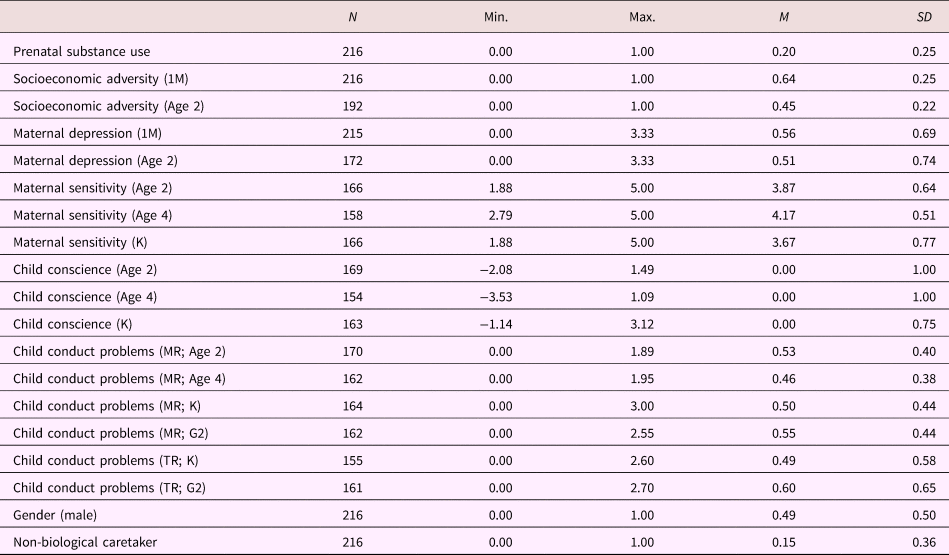

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and ranges are reported in Table 1. Across all variables, about 17.3% of the data were missing. Missing data increased with the passage of time such that 0.1% of the data were missing at the 1-month assessment and 25.2% of data were missing in Grade 2 (25.0% for mother reports and 25.5% for teacher reports). A series of univariate t tests were performed to test whether race, gender, non-biological caretaker, prenatal substance use, maternal depression (at 1 month), and socioeconomic adversity (at 1 month) were associated with higher rates of attrition and dropout across time. At the 2-year, 4- year, and kindergarten waves, the t tests were consistently nonsignificant, suggesting that participant attrition during these waves was not statistically associated with these indicators. In Grade 2, participants who had dropped out of the study had significantly higher levels of early maternal depression compared to those who remained in the study (t = –2.84, p < .01), but there were no statistically significant differences with respect to race, gender, non-biological caretaker, prenatal substance use, or socioeconomic adversity. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used in all subsequent path analyses. This missing data estimation technique retains all of the participants in the analyses and provides more accurate and less biased estimates than more traditional missing data techniques (e.g., listwise deletion; Enders, Reference Enders2010).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for study variables

Note: M, month. K, kindergarten. MR, mother report. TR, teacher report, G, grade.

The bivariate correlations (see Table 2) indicated moderate stability over time across the repeated measures. Prenatal substance use was positively correlated with socioeconomic adversity and maternal depression, and negatively correlated with maternal sensitivity. Higher socioeconomic adversity was associated with higher maternal depression, and lower sensitivity, and child conduct problems. Conscience was negatively associated with conduct problems. Among the covariate effects, having a non-biological caretaker was correlated with prenatal substance use and lower maternal depression, and boys had lower levels of conscience than girls.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations for all study variables

Note: SEA, socioeconomic adversity. M, month. Mat., maternal. K, kindergarten. CP, conduct problems. MR, mother report. TR, teacher report. G, grade. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Path analysis

A series of path models were estimated to test each of the alternative models. In all, six models were initially specified. Model 1 tested the cascade model. Models 2–5 tested the four hypotheses pertaining to the additive model. Model 6 tested the transactional model. Of note, for several of the models that were initially specified (e.g., Models 2, 3, and 4), additional modifications were made upon further examination. These modifications are discussed in detail below, and these corresponding models are denoted with an “m” (e.g., Model 2m). Model fit indices and nested model comparisons are reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Model fit indices and nested model comparisons for alternative models

Note: Model in bold indicates the final selected model.

The first model specified was the developmental cascade model (see Model 1 in Table 3). This model accounted for the sequential processes illustrated in the conceptual model shown in Figure 1a, as well as stability (autoregressive) effects and within-time correlations. Although prenatal substance use was not conceived as a causal predictor of socioeconomic adversity, a regression path was estimated to reflect their potential association and the temporal ordering of these variables (b = .19, p = .001). Contrary to expectations, prenatal substance use was not associated with maternal depression (at 1 month; b = .04, p = .56), socioeconomic adversity (at 1 month) was not significantly associated with increases in maternal depression (at 2 years: b = .11, p = .13), after accounting for significant stability in maternal depression (b = .42, p < .001), and maternal depression (at 1 month and 2 years) was not prospectively associated with maternal sensitivity (at 2 years: b = –.01, p = .89 and at 4 years: b = –.04, p = .53). Maternal sensitivity (at 4 years) was a significant predictor of conscience (at kindergarten age; b = .18, p = .03), controlling for the stability of conscience (b = .20, p < .01). Conscience (at 4 years and kindergarten age) significantly predicted declines in teacher, but not mother, reports of conduct problems (in kindergarten: b = –.25, p < .01 and in Grade 2: b = –.12, p = .03). In addition to these effects, the covariate effects indicated that prenatal substance use was associated with having a non-biological caretaker (b = .60, p < .001). In turn, having a non-biological caretaker was associated with lower socioeconomic adversity (at 2 years: b = –.15, p = .03) and maternal depression (at 2 years: b = –.20, p < .001), but not maternal sensitivity (at 2 years: b = –.03, p = .71), conscience (at 2 years: b = .04, p = .57), or conduct problems (at 2 years: b = –.10, p = .10). Boys had significantly lower rates of conscience (b = –.19, p = .01), but not conduct problems (b = –.01, p = .89) than girls.

After specifying the developmental cascade model, specific hypotheses pertaining to the additive effects models were tested in separate models (Models 2–5). Each of these models included the parameters specified in the cascade model in addition to potential additive effects. First, to test for the additive effects of prenatal substance use on maternal sensitivity, conscience, and conduct problems (at 2 years old), a model (i.e., Model 2) was specified that included three additional paths (i.e., direct effects). This model was compared to the cascade model (Model 1), and results indicated that these additional paths did not collectively improve model fit (see Table 3). Although the overall model fit was not significantly better, the path from prenatal substance use to maternal sensitivity (at 2 years) was significant (b = –.19, p = .05), and therefore, retained in subsequent models (referred to as a modified Model 2; i.e., Model 2m).

Second, to test for the additive effects of socioeconomic adversity (at 1 month and 2 years) on maternal sensitivity, conscience, and conduct problems (at 2 years and 4 years), a model (i.e., Model 3) was specified that included six additional paths (i.e., direct effects). This model was compared to the prior model (Model 2m), and results indicated that these additional paths significantly improved model fit. Findings revealed that the significant improvement in model fit was mostly attributable to one path, from socioeconomic adversity (at 1 month) to maternal sensitivity (at 2 years; b = –.23, p < .01). Therefore, this individual path was retained in subsequent models and referred to as a modified Model 3 (i.e., Model 3m).

Third, to test for the additive effects of maternal depression (at 1 month and 2 years) on conscience and conduct problems (at 2 years and 4 years), a model (i.e., Model 4) was specified that included four additional paths. This model was compared to the prior model (Model 3m). These paths did not significantly improve model fit; however, the nested model test approached statistical significance (p = .08). The individual paths were further assessed to determine if they contributed to improvements in model fit. The path from maternal depression (at 2 years) to conduct problems (at 4 years) was significant (b = .17, p = .04), and was retained in subsequent models, and referred to as a modified Model 4 (i.e., Model 4m).

Fourth, to test for the additive effects of maternal sensitivity (at 2 years, 4 years, and kindergarten) on conduct problems (at 4 years, kindergarten, and Grade 2), a model (i.e., Model 5) was specified that included five additional paths. This model was compared to the prior model (Model 4m), and results indicated that these paths did not significantly improve model fit; however, the nested model test approached statistical significance (p = .09). The individual paths were also assessed to determine if they contributed to improvements in model fit. Because none of these paths were statistically significant, Model 4m was retained.

Fifth and finally, the transactional model (Model 6) was specified. This model included the parameters specified in Model 4m in addition to transactional effects. More specifically, this model included six additional paths from conscience and conduct problems (at 2 years and 4 years) to maternal sensitivity (at 4 years and kindergarten), and from conduct problems (at 2 years and 4 years) to conscience (at 4 years and kindergarten). This model was compared to Model 4m, and results indicated that these effects did not significantly improve model fit. Because none of the individual paths were statistically significant, Model 4m was retained.

Results for Model 4m are presented in Figure 2. Findings from this model provided support for many of the hypotheses postulated in the conceptual model pertaining to developmental cascade processes, and some support was garnered for additive effects. More specifically maternal sensitivity (at 4 years) was positively associated with conscience (at kindergarten), and conscience (at age 4 and kindergarten) was negatively associated with teacher-reported conduct problems (at kindergarten and Grade 2). Contrary to expectations (as hypothesized in the cascade model), maternal depression was not associated with maternal sensitivity. However, findings indicated that there were significant associations (i.e., additive effects) from prenatal substance use and socioeconomic adversity (at 1 month) to maternal sensitivity (at 2 years). Moreover, maternal depression (at 2 years) was significantly and positively associated with conduct problems (at 4 years).

Figure 2. Path diagram for final model (Model 4m: RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .06, CFI = .95, χ = 141.18, df = 108, p = .02). Standardized estimates are reported for statistically significant effects (solid lines). Dashed lines represent paths that were estimated but not statistically significant. Within-time correlations (i.e., covariances and residual covariances) were estimated in the model, but are not illustrated here to simplify the presentation of results. SEA, socioeconomic adversity. CP, conduct problems. MR, mother report. TR, teacher report. *p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

In consideration of the effects that were found in the final selected model, several mediation (indirect) effects were estimated. Because it is not possible to estimate bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) using the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors estimator, the final model was estimated again using maximum likelihood estimation. Of note, significance tests were similar using these two estimators. First, a significant indirect effect was found from prenatal substance use to maternal sensitivity (at 2 years) via socioeconomic adversity (at 1 month; b = –.112, 95% CI [–.262, –.031]). Second, a significant indirect effect was found from prenatal substance use to maternal sensitivity (at 4 years) via maternal sensitivity (at 2 years; b = –.126, 95% CI [–.327, –.004]). Third, a significant indirect effect was found from maternal sensitivity (at 4 years) to teacher-reported conduct problems (at Grade 2) via conscience (at kindergarten age; b = –.027, 95% CI [–.080, –.001]). Fourth, a significant indirect effect was found from maternal depression in infancy to mother-reported conduct problems (at age 4) via maternal depression (at 2 years; b = .040, 95% CI [.004, .090]).

As previously noted, a control variable was included in the path models to assess the role of having a non-biological caretaker. Results indicated that greater maternal prenatal substance use increased the likelihood that children would have a non-biological caretaker, which in turn was associated with lower levels of maternal depression and socioeconomic adversity (at 2 years). Although the sample size was insufficient to perform a multigroup analysis to investigate more comprehensively the differences between children with a biological versus non-biological primary caretaker, follow-up analyses were performed to further ascertain whether the inclusion of these children in the same model substantially altered the overall pattern of findings. Specifically, children who had a non-biological caretaker (n = 33) were excluded and the path estimates for the final selected model (Model 4m) were reexamined (χ2 = 148.28, df = 99, p < .01, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .07, CFI = .89). The analyses indicated that these two models were comparable with respect to the path estimates and significance tests, with one notable exception. After removing children who had a non-biological caretaker, maternal prenatal substance use was positively associated with maternal depression in infancy (b = .19, p = .02).

Discussion

This study provides insights into the developmental pathways of early onset conduct problems. Findings elucidated several processes by which prenatal substance use, socioeconomic adversity, maternal depression and sensitivity, and children's conscience contributed to children's conduct problems. By testing three alternative conceptual models (Figure 1), it was possible to account for competing hypotheses and build greater confidence in the obtained findings. The results corroborated several of the hypotheses stipulated in the developmental cascade model, and there was some support for additive effects. More specifically, consistent with principles of equifinality, the results implicated multiple distinct pathways to children's conduct problems. In the first pathway, maternal prenatal substance use was associated with greater socioeconomic adversity, which in turn was associated with lower maternal sensitivity. Of note, additive effects also emerged in this pathway such that prenatal substance use was associated with lower maternal sensitivity, over and above its indirect association via socioeconomic adversity. Subsequently, lower maternal sensitivity was associated with decreases in children's conscience, and lower conscience predicted increases in teacher-reported conduct problems in middle childhood. In the second pathway, there was a progression from sustained maternal depression (from infancy to toddlerhood) to early childhood conduct problems (at age 4). Of note, less support was garnered for transactional effects of early conduct problems. However, because this study was primarily interested in investigating coercive processes between maternal sensitivity and children's adjustment (i.e., conscience and conduct problems), there were other transactional processes that were not investigated here, but which warrant further attention in future research (e.g., potential bidirectional associations involving maternal substance use, socioeconomic adversity, maternal depression, and conduct problems).

By utilizing an integrative model, these findings have implications for how prenatal substance use, family and socioeconomic stress, maternal depression, and parental socialization of children's self-regulation collectively function as determinants of children's conduct problems. Contributing to the strengths of this study was a repeated-measures, multimethod, multi-informant design consisting of maternal and toxicology reports of prenatal substance use, maternal reports of socioeconomic adversity and depression, observational reports of parenting, laboratory assessments of children's internalization and conscience and mother and teacher reports of children's conduct problems. Thus, concerns pertaining to shared method variance were reduced, and it was possible to control for concurrent associations (i.e., within-time covariances) and stability (autoregressive) effects for several of the primary constructs over time.

Prenatal substance use, socioeconomic adversity, and maternal sensitivity

The findings indicated a significant association between prenatal substance use and maternal sensitivity (at 2 years old), which was partially mediated by socioeconomic adversity in infancy. With respect to the association between prenatal substance use and socioeconomic adversity, the results imply that substance-using mothers may have greater difficulty obtaining financial resources and stability, and are at risk for remaining in poverty. However, because the current analytic design did not account (i.e., control) for prenatal socioeconomic adversity, or postnatal substance use, alternative explanations about the potential direction of effect between these two variables cannot be ruled out.

In addition to its indirect association (via socioeconomic adversity), prenatal substance use also had a direct effect on lower maternal sensitivity. Although prenatal substance use and socioeconomic adversity were associated with each other, the presence of an additive effect on maternal sensitivity indicates that these risk factors represent distinct processes by which maternal sensitivity is compromised. Of note, in the current investigation, multiple substances including alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and tobacco use were aggregated because of the high co-occurrence across these substances, and to reduce the overall model complexity. Thus, the independent effects of each substance could not be determined. Although these findings pertaining to the aggregated substance use variable provided support for the premise that substance-using mothers were less likely to engage in sensitive and warm parenting styles, these associations may be further scrutinized in future research by differentiating both the severity and the type of mother's substance use (Bada et al., Reference Bada, Das, Bauer, Shankaran, Lester, LaGasse and Higgins2007; Eiden et al., Reference Eiden, Granger, Schuetze and Veira2011).

In light of the findings that indicated a nonsignificant association from prenatal substance use to conduct problems (in toddlerhood), assessed in the additive model, prenatal substance was a more distal predictor of children's conduct problems. That is, its association with children's conduct problems was explained primarily by lower maternal sensitivity. Integrating these findings with the family stress perspective, we contend that prenatal substance use may function as an additional risk factor that exacerbated early childhood conduct problems, beyond the effects of socioeconomic adversity, and via its association with maternal sensitivity.

The findings also indicated a significant association from socioeconomic adversity (in infancy) to lower maternal sensitivity (in the toddler years). This association was consistent with the central assertions of the family stress perspective (Conger & Donnellan, Reference Conger and Donnellan2007; Conger et al., Reference Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd and Brody2002), according to which family-related stresses associated with socioeconomic adversity lead to declines in parents’ abilities to engage in sensitive and warm parenting styles, and abstain from being overly harsh. However, considering that this association was significant from infancy to toddlerhood (age 2), but not from toddlerhood to early childhood (age 2 to age 4), there may be developmental variations in these associations. One possible explanation for these findings pertains to how the toddler years are a particularly challenging time, as children become more physically active and mobile, but have only rudimentary self-regulation and cognitive skills (Shaw & Shelleby, Reference Shaw and Shelleby2014). Due to these challenges, it is possible that socioeconomic adversity during this developmental period is particularly problematic because it undermines and exacerbates a stressful childrearing period.

With respect to the additive effects model, this study tested the hypothesis that socioeconomic adversity has a unique effect on early onset conduct problems, beyond its potential influence on maternal sensitivity; however, the findings did not support this hypothesis. Taken together, the lack of support for an additive effect and evidence of a mediated effect imply that the influence of socioeconomic adversity during the early childhood years is more distal and primarily via its effects on more proximal family and parenting processes. This interpretation is consistent with the premise that young children are less likely to have direct exposure to the effects of broader contextual stressors. However, by the time children reach school age and begin to spend greater amounts of time outside of their immediate home environments, it is plausible that the effects of socioeconomic adversity and broader contextual influences become more pronounced and are less consistently mediated by parenting (Criss, Shaw, Moilanen, Hitchings, & Ingoldsby, Reference Criss, Shaw, Moilanen, Hitchings and Ingoldsby2009; Doan, Fuller-Russell, & Evans, Reference Doan, Fuller-Rowell and Evans2012; Shaw, Hyde, & Brennan, Reference Shaw, Hyde and Brennan2012). In support of this viewpoint, Shaw, Sitnick, Brennan, et al. (Reference Shaw, Sitnick, Brennan, Choe, Dishion, Wilson and Gardner2016) found more consistent additive effects of neighborhood deprivation on children's externalizing behaviors after children had reached school age (i.e., during middle and late childhood) than during their early childhood years.

Maternal sensitivity, children's conscience, and conduct problems

The findings indicated that maternal sensitivity was positively associated with increases in children's conscience (from age 4 to kindergarten). Consistent with parental socialization perspectives (Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan2006), this association provided support for the premise that maternal sensitivity contributes to a nurturing parent–child relationship in which parental power assertions are reduced and children become internally motivated to comply with parental rules and standards, even in the absence of parental supervision (Kochanska, Reference Kochanska1995; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Forman, Aksan and Dunbar2005). Considering that early childhood is a sensitive period for the development of conscience (Aksan & Kochanska, Reference Aksan and Kochanska2005), it was unexpected that the association from maternal sensitivity to conscience was not also significant from 2 to 4 years old. Nonetheless, these findings indicate that parental socialization processes influence the continuing development of conscience as children are making the transition to kindergarten. Of note, in the current study, the measurement of conscience primarily reflected moral conduct (i.e., how children engage in rule-compatible behaviors). Thus, the findings pertaining to conscience should be qualified by their focus on moral conduct, and it was not possible to determine whether similar findings would have emerged for other components of conscience, such as moral emotions (e.g., guilt and empathic distress; Aksan & Kochanska, Reference Aksan and Kochanska2005; Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan2006).

These findings complement existing research on children's self-regulation more broadly, and provide support for the proposition that self-regulatory processes, including conscience (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Barry, Aksan and Boldt2008), effortful control (Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, Reiser, Hofer and Michalik2010; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Zhou, Spinrad, Valiente, Fabes and Liew2005; Valiente et al., Reference Valiente, Eisenberg, Spinrad, Reiser, Cumberland and Liew2006), and attentional control (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Pasco Fearon and Bell2007), mediate the associations between parenting and conduct problems. However, findings from other investigations using comparable research designs (e.g., repeated-measures full-panel models) have not consistently found support for this mediated effect based on either lower income or higher income samples (e.g., see Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad, Eggum, Silva, Reiser, Hofer and Michalik2010; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Obradović and Egeland2010). Considering variations across these studies with respect to sampling (e.g., family income levels), developmental period, and measurement (constructs of parenting, self-regulation, and externalizing problems), there are several possible explanations for these divergent findings.

Of note, much of the existing research on the parental socialization of self-regulation has been done with Caucasian middle-class samples, and there remains a need to investigate processes of self-regulation in diverse ethnic and socioeconomic populations, and to further consider the intersections of race and class (Moilanen, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner, & Wilson, Reference Moilanen, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner and Wilson2010; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Obradović and Egeland2010). Investigators have theorized that in the context of socioeconomic adversity, parental expectations for children's obedience and autonomy may increase and that parents have greater demands for their children to be self-sufficient at younger ages in order to prepare for greater environmental challenges (Supplee, Skuban, Shaw, & Prout, Reference Supplee, Skuban, Shaw and Prout2009). In this context, the role of internalization may be particularly important because it functions as an essential component for children to be autonomous, self-regulated, and obedient. Moreover, children who have difficulty meeting these expectations may be at greater risk for conduct problems. Consistent with this viewpoint, the results indicated that children who showed lower levels of conscience were at greater risk for having increases in conduct problems. Moreover, these associations became more pronounced in the latter parts of early childhood as opposed to the earlier years (i.e., from ages 2 to 4), presumably because children are in the process of developing conscience during these earlier years, and its associations with conduct problems are stronger once it becomes more established.

By including both mother and teacher reports of conduct problems, it was possible to further assess informant differences in the findings. Of note, discordant findings emerged by informant type; laboratory assessments of conscience were more strongly associated with teacher-reported conduct problems than mother reports, which may reflect the different perspectives on which mother and teacher reports are typically based (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, Reference De Los Reyes and Kazdin2005). For instance, aggressive and disruptive behaviors within a school setting are generally contrary to teacher expectations and school rules. However, within the home context, if parents are more lenient about their children's conduct problems, then it would not necessarily be associated with children's conscience or their internalization of rules. Alternatively, there may be variations in children's compliance to rules in different settings. Perhaps compliance to rules within a laboratory setting is more predictive of children's behaviors within a structured school setting than their behaviors at home. Although it is difficult to interpret the exact causes of these informant differences, Roisman, Fraley, Haltigan, Cauffman, and Booth-Laforce (Reference Roisman, Fraley, Haltigan, Cauffman and Booth-Laforce2016) also reported stronger mediated effects for teacher- versus mother-reported externalizing problems.