Although the rate of divorce has decreased since the 1980s (National Center for Health Statistics, 2008), it is estimated that 1.1 million children in the United States experience divorce each year (Kreider & Ellis, Reference Kreider and Ellis2011). Compelling evidence has shown that this transition in family structure confers risk for multiple problems in childhood and adolescence including impairments in academic (Amato & Anthony, Reference Amato and Anthony2014; Strohschein, Roos, & Brownell, Reference Strohschein, Roos and Brownell2009) and social competence (Amato, Reference Amato2001), mental health problems (Amato, Reference Amato2001; Kim, Reference Kim2011), problematic substance use (Brown & Rinelli, Reference Brown and Rinelli2010), early sexual activity (Donahue et al., Reference Donahue, D'Onofrio, Bates, Lansford, Dodge and Pettit2010), and suicide attempts (Weitoft, Hjern, Haglund, & Rosén, Reference Weitoft, Hjern, Haglund and Rosén2003).

For a sizeable number of offspring, the effects of parental divorce continue into adulthood, with some research indicating that differences between offspring in two-parent versus divorced families widen from childhood to adulthood (Cherlin, Chase-Lansdale, & McRae, Reference Cherlin, Chase-Lansdale and McRae1998). Compared with adults who are raised in two-parent families, those from divorced families are more likely to experience difficulties in several domains of functioning. Specifically, adults who experienced parental divorce in childhood have lower educational and occupational attainment (Larson & Halfon, Reference Larson and Halfon2013), poorer marital quality (Amato, Reference Amato, Clarke-Stewart and Dunn2006), higher rates of divorce (Gähler, Hong, & Bernhardt, Reference Gähler, Hong and Bernhardt2009), and lower quality peer relationships (Kunz, Reference Kunz2001). They also have increased rates of problematic substance use (Barrett & Turner, Reference Barrett and Turner2006), more mental (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McLaughlin, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Benjet2010) and physical health problems (Lacey, Kumari, & McMunn, Reference Lacey, Kumari and McMunn2013) and earlier mortality (Larson & Halfon, Reference Larson and Halfon2013).

Several research groups have developed interventions that are designed to reduce or prevent the problems that are associated with parental divorce. Randomized trials have shown short-term effects of parent- and child-focused interventions on externalizing problems, noncompliance, anxiety, and learning problems (Forgatch & DeGarmo, Reference Forgatch and DeGarmo1999; Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, Reference Pedro-Carroll and Cowen1985; Sandler et al., Reference Sandler, Wolchik, Mazza, Gunn, Tein, Berkel and Porter2019; Stolberg & Mahler, Reference Stolberg and Mahler1994; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, West, Westover, Sandler, Martin, Lustig and Fisher1993, Reference Wolchik, West, Sandler, Tein, Coatsworth, Lengua and Griffin2000). Although less studied, positive short-term effects on peer social competence and academic performance have been reported in two trials (Crosbie-Burnett & Newcomer, Reference Crosbie-Burnett and Newcomer1990; Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, Reference Pedro-Carroll and Cowen1985).

The limited research on the longer-term effects of these programs has focused almost exclusively on problem outcomes. Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo, and Beldavs (Reference Forman, Olin, Hoagwood, Crowe and Saka2009) found that a parenting-focused program that was delivered in childhood reduced delinquency and arrests nine years after participation. Wolchik et al. (Reference Wolchik, West, Sandler, Tein, Coatsworth, Lengua and Griffin2002) found significant effects of a parenting-focused intervention 6 years after participation on multiple problem outcomes including externalizing problems, internalizing problems, alcohol use, drug use, and number of sexual partners when offspring were 15 to 19 years old. Program effects also occurred on multiple aspects of competence at the 6-year follow-up, including higher grade point average, more adaptive coping, higher self-esteem, and higher expectations about educational goals and job aspirations (Sigal, Wolchik, Tein, & Sandler, Reference Signal, Wolchik, Tein and Sandler2012; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2002, Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, Winslow, Briesmeister and Schaefer2007). Several of these effects were moderated by level of risk, with greater benefits occurring for those who entered the program at higher risk. At the 15-year follow-up, when the offspring were emerging adults (ages 24 through 28), this intervention led to a lower incidence of internalizing disorders (Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Tein, Mahrer, Millsap, Winslow and Reed2013) and less involvement with the criminal justice system (Herman et al., Reference Herman, Mahrer, Wolchik, Porter, Jones and Sandler2015). For males, program effects also occurred on drug use and substance use disorders (Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Tein, Mahrer, Millsap, Winslow and Reed2013). In addition, the program led to fewer problematic beliefs about divorce (Christopher et al., Reference Christopher, Wolchik, Tein, Carr, Mahrer and Sandler2017) and for males, more negative attitudes toward divorce (Wolchik, Christopher, Tein, Rhodes & Sandler, Reference Wolchik, Christopher, Tein, Rhodes and Sandler2019). In the only study to examine the effects of programs for divorced families on outcomes related to the developmental tasks of adulthood, Mahrer, Winslow, Wolchik, Tein and Sandler (Reference Mahrer, Winslow, Wolchik, Tein and Sandler2014) reported effects on positive attitudes toward parenting among the emerging adults in this cohort at the 15-year follow-up.

Examining the effects of prevention programs for divorced families on other aspects of competence in emerging adulthood is important given the many changes that occur in social and contextual roles and the multiple life choices that are being made during this period (Arnett & Tanner, Reference Arnett and Tanner2006; Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, Reference Schulenberg, Sameroff and Cicchetti2004). The consequences that are associated with competence become more significant and enduring as young people settle into the tasks of adulthood (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Moffitt, Caspi, Magdol, Silva and Stanton1996). For example, choices are made that can have a substantial influence on one's life course, such as investment in work or education and choice of romantic partners (Arnett & Tanner, Reference Arnett and Tanner2006; Elder, Reference Elder, Phelps, Furstenberg and Colby2002).

Although parental divorce is associated with impairments in the accomplishment of the salient developmental tasks of adulthood, researchers have not addressed whether prevention programs for divorced families affect the salient developmental tasks of emerging adulthood, most notably work, academic, social, and romantic competence. A few comprehensive prevention programs for other populations have shown positive program effects on various domains of adult competence such as educational attainment, occupational prestige, employment, and emotion regulation in adulthood (Campbell, Ramey, Pungello, Sparling, & Miller-Johnson, Reference Campbell, Ramey, Pungello, Sparling and Miller-Johnson2002; Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, Reference Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill and Abbott2005, Reference Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill and Abbott2008; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Bailey, Hawkins, Catalano, Kosterman, Oesterle and Abbott2014; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Robertson, Mersky, Topitzes and Niles2007; Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2011; Schweinhart et al., Reference Schweinhart, Montie, Xiang, Barnett, Belfield and Nores2005). However, all of these programs lasted a year or more. It is unknown whether much shorter prevention programs influence competence in adulthood. Evidence of long-term program effects on outcomes that have financial benefits, such as academic performance and work competence (Day & Newburger, Reference Day and Newburger2002; Trevor, Gerhart, & Boudreau, Reference Trevor, Gerhart and Boudreau1997; Wolla & Sullivan, Reference Wolla and Sullivan2017) could demonstrate a high return on investment, thereby leveraging support for implementing such programs. In addition, studying the associations between program-induced changes earlier in development and competence in later stages of development can advance theory about the spreading effects of interventions across development and identify the pathways through which prevention programs influence later outcomes (Coie et al., Reference Coie, Watt, West, Hawkins, Asarnow, Markman and Long1993; Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2016).

Interventions with parents or families that are intended to trigger positive and progressive effects over time offer compelling experimental tests of cascade models that are based on developmental systems theory as well as resilience theory (Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten and Cicchetti2010). Parenting can be viewed as a leverage point for changing children's behaviors and attitudes, with effects that spread across time, domains of function, and systems (Doty, Davis, & Arditti, Reference Doty, Davis and Arditti2017; Masten & Palmer, Reference Masten, Palmer and Bornstein2019).

The current study examines the effects of the New Beginnings Program, a relatively brief (11-session) parenting-focused program for divorced families, on competence in early adulthood. The conceptual model underlying the development of the New Beginnings Program drew from the risk and protective factor and person–environment transactional frameworks (IOM, 1990; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff, Steinberg and Silverman1987). The risk and protective factor model posits that the likelihood of mental health problems is affected by exposure to risk factors and the availability of protective resources (IOM, 1994). In the person–environment transactional model, dynamic person–environment processes are seen as affecting problems and competence, which then influence the social environment and competence and problems (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2000). The program was designed to reduce interparental conflict, one of the most harmful risk factors in divorced families, and to augment the empirically supported protective factors of mother–child relationship quality, contact with fathers, and effective discipline. From the perspective of developmental cascade models, the program's effects on these risk and protective factors in childhood were expected to lead to positive changes across domains of functioning (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Roisman, Long, Burt, Obradović, Riley and Tellegen2005; Rutter & Sroufe, Reference Rutter and Sroufe2000; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2000).

This project examined the long-term effects of the New Beginnings Program by testing its effects on competence in emerging adulthood. We expected that program-induced changes in parenting and behavior problems in childhood would have cascading effects on competencies and behavior problems in adolescence, which in turn would have cascading effects on competence in adulthood. This hypothesis is derived from two interconnected models, the organizational theory of development and the person–environment transactional model. The organizational theory posits that qualitative reorganizations among and within domains of functioning occur throughout development and that competence at one period of development influences competence at the next period (Cicchetti & Schneider-Rosen, Reference Cicchetti, Schneider-Rosen, Rutter, Izard and Read1986). Similarly, in the person–environment transactional model, individual as well as environmental processes are seen as affecting both problems and competence, which then influence the social environment as well as competence and problems within and across development periods (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2000). In both frameworks, developmental cascades, or the interactions and transactions that occur within and across developing domains of functioning, play a central role in explaining change and continuity in development.

The current research builds on prior work examining the long-term direct and cascade effects of the New Beginnings Program on problem outcomes. Wolchik, Tein, Sandler, and Kim (Reference Wolchik, Tein, Sandler and Kim2016) found that program-induced improvements in academic competence and adaptive coping in adolescence cascaded to fewer internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and binge drinking in emerging adulthood. The current study extends this work by testing whether the New Beginnings Program had positive direct effects on competence in emerging adulthood and whether the program's effects in childhood influenced outcomes in adolescence, which then led to increased competence in emerging adulthood. Based on a developmental cascade model, intervention-induced improvements in parenting were expected to lead to fewer internalizing problems and externalizing problems in childhood, which were expected to lead to improvements in mental health problems, substance use, peer competence, grades, and adaptive coping in adolescence. These improvements were then expected to lead to increases in work competence, academic competence, peer competence, and romantic competence in emerging adulthood. Given that sex and baseline risk moderated other program effects at the 15-year follow-up (Christopher et al., Reference Christopher, Wolchik, Tein, Carr, Mahrer and Sandler2017; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Tein, Mahrer, Millsap, Winslow and Reed2013, Reference Wolchik, Christopher, Tein, Rhodes and Sandler2019), their moderating effects were tested.

Method

Participants

The participants were 240 adult offspring and their mothers who had enrolled in a randomized trial of the intervention for divorced families (Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000) in late childhood/early adolescence. Court records of divorce decrees that had been granted in the last two years in a southwestern metropolitan county were the primary recruitment method, but 20% were recruited through the media or word of mouth. The eligibility criteria were as follows: the mother had a child between 9 and 12 years old who lived with her at least 50% of the time; the mother had not remarried, did not have a live-in partner, and did not plan to remarry during the program; and neither the mother nor child was in treatment for psychological problems (see Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000 for more information about eligibility and recruitment). Because of ethical considerations, families were excluded and referred to treatment if the child endorsed suicidal ideation or had severe internalizing or externalizing problems at the pretest. In families with multiple children in the age range, one was randomly selected to be interviewed. Eligibility was assessed in a phone call and reassessed during the pretest interview.

Of the 622 eligible families, 240 (39% of those eligible) completed an orientation session in which they were randomly assigned to (a) the mother-only program (MP, n = 81 families), (b) the mother-plus-child program (MPCP; separate, concurrent groups for mothers and children, n = 83 families), or (c) the literature control condition (LC, n = 76 families). Preliminary analyses comparing the MPCP and MP on all of the competence outcomes in emerging adulthood indicated that the two intervention conditions did not significantly differ on these variables. Given the lack of differences between the MP and MPCP programs on the competence outcomes and other outcome and mediator variables in our previous studies at posttest, 6-month, 6-year, and 15-year follow-ups (Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000, Reference Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein and Sandler2002, Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Tein, Mahrer, Millsap, Winslow and Reed2013), these conditions were combined and labeled as the New Beginnings condition.

Comparison of acceptors and refusers (i.e., completed the pretest but withdrew from the experimental trial of the program) showed that mothers who accepted the intervention had significantly higher incomes and education and fewer children than those who declined the intervention (Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000). The three experimental conditions did not differ significantly on child mental health problems nor demographics at pretest.

At pretest, 49% of the offspring were girls, and the average age was 10.4 years (SD = 1.1). The mothers’ mean age was 37.3 years (SD = 4.8); 98% had at least a high school education. The breakdown for the mothers’ ethnicity was 88% non-Hispanic White, 8% Hispanic, 2% Black, 1% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 1% other. The mothers had been separated and divorced an average of 2.2 years (SD = 1.4) and 1.0 year (SD = 0.5), respectively.

At the 6-year and 15-year follow-ups, the offspring's average age was 16.9 (SD = 1.1, range = 15–19) and 25.6 (SD = 1.2, range = 24–28), respectively. At both follow-ups, 50% of the offspring who were interviewed were female; ethnicity was 89% non-Hispanic White, 7% Hispanic, 2% African American, and 2% other. At the 15-year follow-up, educational attainment was less than high school (3%), high school (20%), some college (45%), college graduate (29%), and postgraduate (3%). The median income was $30,000, and 23% were married, 1% divorced, 1% separated, 28% living with a partner, and 46% were not previously married, currently married, or living with a partner.

Sample size and power

A sample size of 240 was selected so that small-to-medium effects, the magnitude of the effects that were found in the pilot study of the MP (Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, West, Westover, Sandler, Martin, Lustig and Fisher1993), could be detected with power ≥ .80.

Intervention Conditions

Description of conditions

The parent program consisted of 11 highly structured group sessions (1.75 hours) and two individual (1 hour) sessions that taught skills to improve mother–child relationship quality, increase effective discipline, decrease barriers to father–child contact, and reduce children's exposure to interparental conflict. The sessions included didactic presentations, modeling of the skills by leaders and videotaped actors, role plays of the skills, and review of the program skills that were practiced between sessions.

The 11-session child program was intended to increase effective coping strategies, enhance mother–child relationship quality, and reduce negative thoughts about divorce stressors. The sessions included didactic presentations, videotapes, leader modeling, role plays, and games. The children were expected to practice the program skills between sessions. For details about the programs see Wolchik et al. (Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000).

Each group was led by two master's-level clinicians (13 leaders for the mother groups; 9 for the child groups). Eight to 10 mothers or children were in each group. The leaders used highly detailed session manuals to deliver the groups. Extensive training (30 hr prior to the start of the program and 1.5 hr per week during delivery) and weekly supervision (1.5 hr per week) were provided by doctoral-level clinicians. Prior to the delivery of each session, the leaders were required to score 90% on a quiz about the content of the session. The average scores were 97% (SD = 3%) and 98% (SD = 1%) for the leaders in the mother and child groups, respectively.

Mothers and children in the LC each received three books on children's adjustment to divorce, which were mailed at 1-month intervals. The mothers and children reported reading about half of the books.

Leader completion of program segments

Using the detailed session outlines, each mother session was divided into 7–11 segments and each child session was divided into 7–10 segments. Using videotapes of the sessions, independent coders rated the degree to which each segment was completed (1 = not at all completed; 3 = completed). Interrater reliability, assessed for a randomly selected 20% of the sessions, averaged 98%. The mean degree of segment completion was 2.86 (SD = 0.39) and 3.00 (SD = 0.02) for the mother and child sessions, respectively.

Mother compliance with program

The mothers attended an average of 77% (M = 10.02; SD = 3.56) of the 13 sessions (11 group; 2 individual), and the children attended an average of 78% (M = 8.55; SD = -2.97) of 11 group sessions. When attendance at the make-up sessions was included, the mothers and children attended an average of 83% (M = 10.76; SD = 3.62) and 85% (M = 9.30; SD = 3.00) of the sessions, respectively.

The mothers completed weekly homework diaries reporting on the skills that they practiced. Two coders evaluated the diaries for appropriate completion of each assigned activity. One coder rated all of the diaries, and the other independently rated a randomly selected subset (20%). Interrater agreement averaged 98%. The proportion of assigned activities that was appropriately completed was .54 (SD = .15) and .55 (SD = .15) for the mother and mother-plus-child conditions, respectively.

Procedure

The families participated in six assessments: pretest (T1); posttest (T2); and 3-month (T3), 6-month (T4), 6-year (T5), and 15-year follow-ups (T6). Family-level participation was 98% at T2, T3, and T4; 91% at T5; and 90% at T6. Different trained staff conducted separate interviews with parents and youths/emerging adults. After confidentiality was explained, the children signed assent forms and the parents and offspring over 18 signed consent forms. The families received $45 compensation at T1, T2, T3, and T4, and the parents and youths each received $100 at T5. At T6, the emerging adults received $225 and the parents received $50. The university's Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures.

Measures

The measures are described in terms of the developmental period in which they were administered (e.g., T1–T4 for childhood, T5 for adolescence, and T6 for emerging adulthood). Measures with a timeframe referred to the last month, with exceptions noted. We report the reliability coefficients of the measures for the assessment points that were included in the models.

Childhood

Demographics

At the pretest, the mothers completed questions about demographic variables including their children's and their own age, ethnicity, income, and length of divorce and marriage.

Positive parenting

Positive parenting was a composite of mother and child reports of mother–child relationship quality and discipline at T1 and T2. The discipline and relationship quality composites were strongly related (r = .52 at T1; r = .51 at T2).

Mother–child relationship quality

The mothers and children completed 10 items each from the acceptance and rejection subscales of the Child Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Schaefer, Reference Schaefer1965). Cronbach alphas (α) for the acceptance and rejection subscales at T1 and T2, respectively, were .78 and .81 for the mother reports and .84 and .89 for the child reports. Adequate reliability and validity have been demonstrated for child and parent reports of these scales (e.g., Schaefer, Reference Schaefer1965; Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein, & Sandler, Reference Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein and Sandler2000). The mothers and children also completed the 10-item open family communication subscale of the Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes & Olson, Reference Barnes, Olson, Olson, McCubbin, Barnes, Larsen, Muxen and Wilson1982). Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale scores have been linked to adolescents’ psychological adjustment (Bhushan & Shirali, Reference Bhushan and Shirali1992). Cronbach alphas were .72 and .75 for mothers at T1 and T2, respectively, and .82 and .87 for children at T1 and T2, respectively. The mothers completed a seven-item adaptation of the Family Routines Inventory (Jensen, Boyce, & Hartnett, Reference Jensen, Boyce and Hartnett1983) that assessed mother–child dyadic interactions. Cronbach alphas were .67 and .63 for the mothers at T1 and T2, respectively. Previous research showed adequate reliability and validity of this measure (Cohen, Taborga, Dawson & Wolchik, Reference Cohen, Taborga, Dawson and & Wolchik2000). Consistent with previous studies on the New Beginnings Program, reports on these four scales were standardized and averaged to create a multimeasure, multireporter composite. The weighted alphas (Lord & Novick, Reference Lord and Novick1968) across the variables were .88 and .90 at T1 and T2, respectively. Using confirmatory factor analyses, Zhou, Sandler, Millsap, Wolchik, and Dawson-McClure (Reference Zhou, Sandler, Milsap, Wolchik and Dawson-McClure2008) showed the constructs of mother–child relationship quality and effective discipline (described in the next section) fit the T1 and T2 data adequately.

Effective discipline

Mothers and children completed the eight-item inconsistent discipline subscale of CRPBI (Schaefer, Reference Schaefer1965). Both mothers’ and children's reports of consistency of discipline have been shown to negatively relate to children's adjustment problems (e.g., Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein & Sandler, Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000). Cronbach alphas were .81 and .80 for mother report at T1 and T2, respectively, and .72 and .73 for child report at T1 and T2, respectively. The mothers completed 14 items on the appropriate/inappropriate discipline subscale (T1 α = 0.70, T2 α = 0.71) and 11 items on the follow-through subscale (T1 α = 0.80, T2 α = 0.76) of the Oregon Discipline Scale (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1991). This measure has adequate reliability and validity. These four scales were standardized and averaged to create a composite. The weighted Cronbach alphas were .84 and .89 at T1 and T2, respectively.

Internalizing and externalizing problems

The mothers completed the 31-item internalizing and 33-item externalizing subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991a; Achenbach & Edelbrock, Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock1983). Adequate reliability and validity have been reported (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991b). At T1 α =.88, at T3 α = .86, and at T4 α = .85 for internalizing problems, Cronbach alphas were .87 at T1, .87 at T3, and.87 at T4 for externalizing problems.

Child report of depression during the previous two weeks was measured with the 27-item Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, Reference Kovacs1981). The CDI has been shown to have high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity (Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, Reference Saylor, Finch, Spirito and Bennett1984). In this study, Cronbach alphas were .76 at T1, .78 at T3, and .80 at T4. Youth report of anxiety was assessed with the 28-item Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richard, Reference Reynolds and Richard1978). Convergent and discriminant validity are adequate (Reynolds & Paget, Reference Reynolds and Paget1981). At T1, T3, and T4, Cronbach alphas were .88, .91, and .91. For child report of internalizing problems, a composite of the CDI and RCMAS was formed as the mean of the standardized scores (r = .58–.67 of the two measures across assessments). For externalizing problems, 30 items from the aggression and delinquency subscales of the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991b) were used, and at T1 α = .87, at T3 α = .86, and at T4 α = .88. The reliability and validity of these subscales are adequate (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991b).

Given the 3-month interval, scores for T3 and T4 were averaged (i.e., short-term follow-up). Composite scores of internalizing problems and externalizing problems were constructed by averaging the standardized scores of the mother and child reports.

Adolescence

Symptoms of externalizing and internalizing disorders

Parents and adolescents reported on symptoms of externalizing disorders and internalizing disorders over the past year on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, Reference Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan and Schwab-Stone2000). Scores were computed separately for internalizing disorders (i.e., agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, eating disorders, and major depression) and externalizing disorders (i.e., conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) using symptom scores endorsed by either the parent or adolescent. The DIS has been validated against the WHO Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (Wing et al., Reference Wing, Babor, Brugha, Burke, Cooper, Giel and Sartorius1990).

Substance use

Frequency of marijuana use and alcohol use within the past year (7-point scale, 1 = 0 occasions to 7 = 40 or more occasions) was assessed by using the Monitoring the Future Scale (Johnston, Bachman, & O'Malley, Reference Johnston, Bachman and O'Malley1993). This scale has adequate validity (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Bachman and O'Malley1993). The mean of the frequencies of marijuana and alcohol use was used.

Peer competence

Peer competence was assessed by using adolescent's report of the six-item peer competence subscale of the Coatsworth Competence Scale (CCS; Coatsworth & Sandler, Reference Coatsworth and Sandler1993). This scale has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties (Spaccarelli, Coatsworth, & Bowden, Reference Spaccarelli, Coatsworth and Bowden1995). Cronbach alpha at T5 was .76.

Adaptive coping

Adolescents completed the 24-item active coping dimension of the Children's Coping Strategies Checklist–Revised (Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, Reference Ayers, Sandler, West and Roosa1996) and the seven-item Coping Efficacy Scale (Sandler, Tein, Mehta, Wolchik, & Ayers, Reference Sandler, Tein, Mehta, Wolchik and Ayers2000). Active coping reflected positive strategies for dealing with problems (e.g., behavioral actions to fix the problem or cognitive strategies to reduce the threat of the stressor). Coping efficacy assessed satisfaction with handling past problems and anticipated effectiveness in handling future problems. Both active coping and coping efficacy have been shown to relate to internalizing and externalizing problems (Sandler et al., Reference Sandler, Tein, Mehta, Wolchik and Ayers2000). For active coping and coping efficacy, Cronbach alphas were .88 and .71, respectively, for T1, and .92 and .82, respectively, at T5. The correlation between active coping and coping efficacy was .53 at T1 and .55 at T5. The two measures were standardized and averaged.

Academic performance

Cumulative high school grade point average (GPA) was obtained with questionnaires that were mailed to school principals that requested the unweighted (based on a 4.0 scale) cumulative GPA. Data were collected for all of the participants, regardless of current school enrollment.

Emerging adulthood

Competence

Competence was defined in terms of effective performance in age-salient developmental tasks (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Coatsworth, Neemann, Gest, Tellegen and Garmezy1995). Academic competence was assessed as highest year of education completed. Peer social competence, romantic competence, and work competence were assessed by using a paper-pencil version of the Status Questionnaire (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, Reference Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth and Tellegen2004). After achieving reliability (agreement within one rating scale point for 80% or more of the ratings), coders who were trained by one of the developers of the Status Questionnaire reviewed the responses on the questionnaire and made global ratings of peer, romantic, and work competence. The intraclass coefficients ranged from .70 to .90, with a mean of .83. The work competence score was based on an assessment of holding a job successfully and doing well in work. The peer competence score was based on the degree of involvement in friendships and presence of a close friendship. The romantic competence score was based on involvement in and quality of a romantic relationship. The construct validity of these aspects of competence has been established (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Coatsworth, Neemann, Gest, Tellegen and Garmezy1995).

Baseline covariates and risk

For the postintervention variables, we used the baseline measure of the same measure if administered or a similar measure as a covariate (e.g., T1 peer competence for T5 peer, work, and romantic competence; T1 internalizing problems for T5 internalizing symptoms). We also included baseline internalizing problems and self-esteem as covariates given that they significantly predicted attrition at the 15-year follow-up (Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Tein, Mahrer, Millsap, Winslow and Reed2013).

Previous studies have shown that the program had stronger effects for youths who had higher risk at baseline (Christopher et al., Reference Christopher, Wolchik, Tein, Carr, Mahrer and Sandler2017; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, Winslow, Briesmeister and Schaefer2007), and risk has been found to predict child mental health problems at the 6-year follow-up in the control group of this trial (Dawson-McClure, Sandler, Wolchik & Millsap, Reference Dawson-McClure, Sandler, Wolchik and Millsao2004). Therefore, risk was included as a covariate and we examined whether risk moderated the effects of the program. As in the study by Dawson-McClure et al. (Reference Dawson-McClure, Sandler, Wolchik and Millsao2004), risk was a composite score (i.e., the equally weighted sum of the standardized scores) of the following variables: (a) mother and child reports of child externalizing problems at baseline (the 33-item externalizing subscale of the CBCL for the mother report and 30 items from the aggression and delinquency subscales of the YSR for the child report) and (b) environmental stressors (i.e., the composite of interparental conflict, negative life events that occurred to the child, and per capita annual income).

Statistical Analysis

We first conducted correlational and descriptive statistics. Attrition analyses conducted by Wolchik et al. (Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Tein, Mahrer, Millsap, Winslow and Reed2013) showed that the rates of attrition did not differ significantly across the intervention and LC and there were no significant main effects for attrition or Group × Attrition interaction effects on the demographic and baseline variables except that baseline internalizing problems and self-esteem significantly predicted attrition at the 15-year follow-up. Participants in the 15-year follow-up had significantly more internalizing problems, -0.06 vs. -0.30, t = -2.05, p = .03, and lower self-esteem, 20.45 vs. 21.53; t = 2.33, p = .03, at baseline than those who did not participate. As noted above, we included baseline internalizing problems and self-esteem as covariates.

Separate multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine program effects on the competence measures. The models also included an Intervention × Baseline risk interaction. To reduce the number of parameter estimates and make the figures visually less complicated, we present the cascade mediation models separately for each competence outcome. However, we also ran analyses with all of the competence outcomes in one model for comparison purposes. The results for the path coefficients from the predictors and mediators to the outcomes were consistent between the model that included all of the competence outcomes in one model (results not shown) and those that included only one outcome at a time. All of the differences of the corresponding regression coefficients were less than (unstandardized) b = .02.

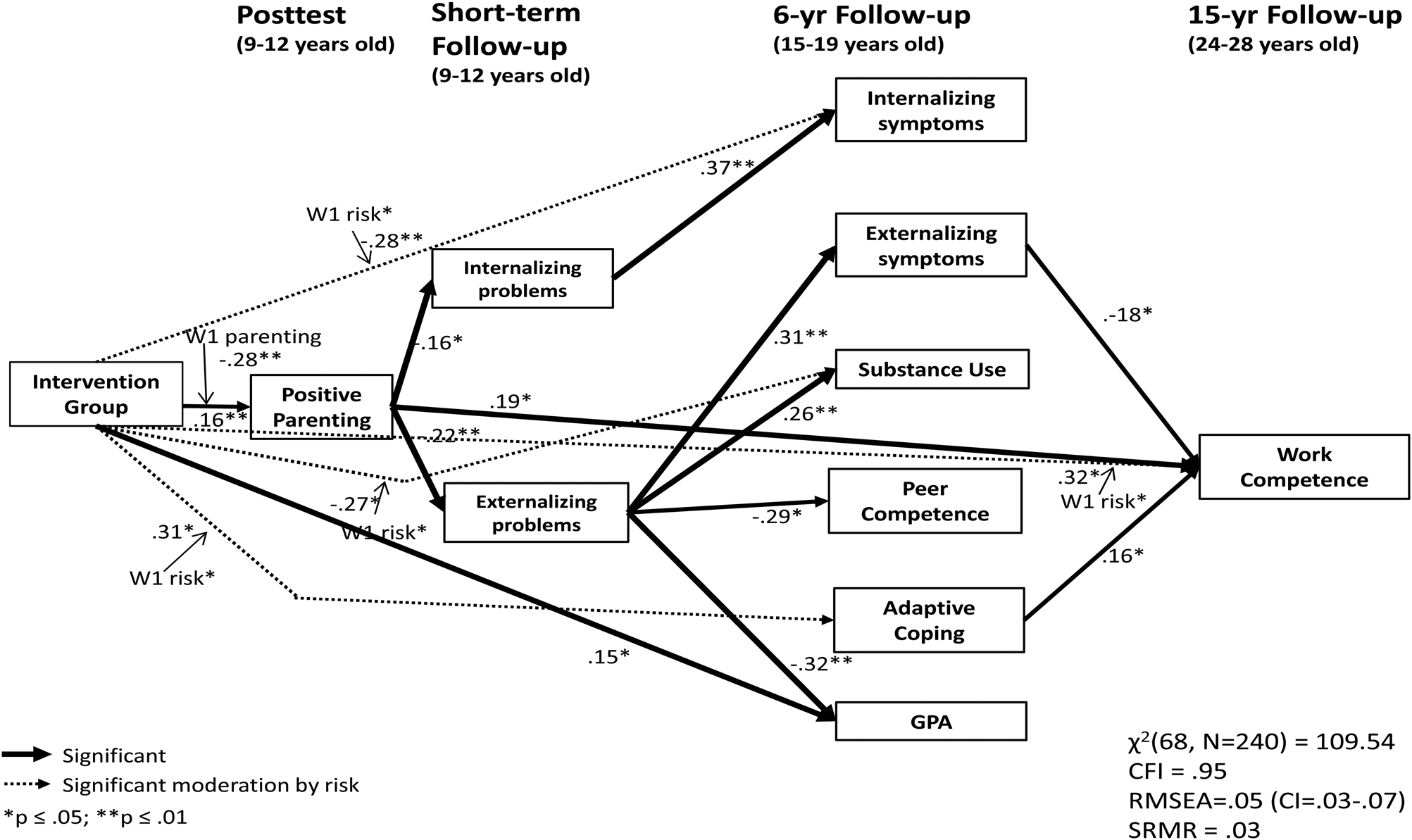

The cascade mediation models shown in Figures 1–3—intervention condition → posttest (T2) → short-term follow-up (3-month follow-up + 6-month follow-up; T3 + T4) → 6-year follow-up (T5) → 15-year follow-up (T6)—were tested by using structural equation modeling (i.e., path modeling with observed variables) that was completed by using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). The full information maximum likelihood method was applied to handle missing data. The skewness and kurtosis of the variables in the models were all within the acceptable range (skewness cutoff ≤ 2 and kurtosis cutoff ≤ 7; West, Finch, & Curren, Reference West, Finch, Curran and Hoyle1995), so we used the maximum likelihood method for parameter estimation.

Figure 1. Cascade effects of adolescent mental health problems, substance use, and competence on work competence in emerging adulthood.

Figure 2. Cascade effects of adolescent mental health problems, substance use, and competence on academic competence in emerging adulthood.

Figure 3. Cascade effects of adolescent mental health problems, substance use, and competence on peer competence in emerging adulthood.

For each postintervention childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood mediator and outcome measure, we also included direct paths from T1 covariates, the intervention condition (to test direct intervention effects), baseline risk, and the Intervention Condition × Risk interaction (to examine possible moderated intervention effects by risk). If an interaction was not significant, we deleted it and reran the model. We also added the baseline positive Parenting × Intervention interaction in predicting posttest positive parenting given that Wolchik et al. (Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000) showed that the program effect on parenting was stronger for families with lower baseline parenting scores. To make Figures 1–3 visually less complicated, we omitted the paths from the baseline covariates to the mediators and outcomes and the correlations among the study variables that were measured at the same time. Supplemental Tables 1–4 present the path coefficients from the baseline covariates to the mediators and from the mediators in the earlier assessments to the later assessments as well as the correlations among the contemporaneous variables.

We examined the potential mediation effects by using the bias-corrected bootstrapping method (Mackinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West and Sheets2002), a method that has been shown to have good statistical power and excellent control of Type I error rates. If zero were not included in the 90% or 95% confidence interval (CI), it was assumed that the mediated effect was statistically significant.

We conducted multigroup structural equation modeling to test for sex differences by examining which regression parameters were significantly different between males and females.

Results

Correlations

Tables 1, 2, and 3 present the correlations among the baseline measures, among the postintervention measures, and between the baseline and postintervention measures. Means, standard deviations, and skewness and kurtosis indices of these variables are also included. The correlations between the competence outcome variables ranged from .12 to .27.

Table 1. Correlations of the baseline measures

Note: **p ≤ .01. *p ≤ .05.

Table 2. Correlations of the postintervention measures

Note: **p ≤ .01. *p ≤ .05.

Table 3. Correlation between baseline measures and postintervention measures

Note: 1. T2 Positive parenting; 2. T3/T4 Internalizing problems; 3. T3/T4 Externalizing problems; 4. T5 Internalizing symptoms; 5. T5 Externalizing symptoms; 6. T5 Substance use; 7. T5 Peer competence; 8. T5 Positive coping; 9. T5 GPA; 10. T6 Work competence; 11. T6 Peer social competence; 12. T6 Romantic relationship competence; 13. T6 Academic competence. **p ≤ .01. *p ≤ .05.

Direct Effects on Competence

Multiple regression analyses showed that the effect of the intervention condition (intervention vs. LC) on work competence, unstandardized b = .43, SE = .22, z = 1.95, p = .052, was marginally significant and the interaction of Intervention × Baseline Risk on work competence, b = .59, SE = .28, z = 2.06, p = .04, was significant. On average, the participants in the intervention condition had higher work competence, M LC = 4.47, M I = 4.90; Cohen d = .27, than did those in the LC condition. The difference on work competence was greater for those who had higher levels of baseline risk (e.g., at one standard deviation above the mean of baseline risk, b = 1.02, SE = .41, z = 2.48, p = .01, d = .35. The direct effects of the intervention and the Intervention × Baseline Risk interaction on academic competence, peer competence, and romantic competence were not significant.

Cascade Effects

Childhood to adolescence

Figures 1–3 show the cascade models for (a) work competence, (b) academic competence, and c) peer competence. The figures include the model fit indices and standardized regression coefficients for the paths that were significant, excluding the significant paths from the covariates to the mediators and outcomes.

All three models fit the data adequately (comparative fit index ≥ .94, root mean square error of approximation ≤ .06; standardized root mean square residual ≤ .04; See Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). The mediation pathways from intervention condition to adolescence (6-year follow-up) were mostly consistent across outcomes, but the parameter estimates varied slightly across models due to the use of the maximum likelihood method with models that had different dependent variables.

As expected, the cascading mediation effects of the intervention to parenting and internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood and to mental health problems, substance use, and competence in adolescence were largely consistent with the findings that were presented in Wolchik et al. (Reference Wolchik, Tein, Sandler and Kim2016). Specifically, the intervention increased positive parenting at posttest and this effect was stronger for families with lower positive parenting scores at baseline. Posttest positive parenting was related to fewer internalizing and externalizing problems at the short-term follow-up (3-month and 6-month follow-ups). Internalizing problems in childhood were related to higher internalizing symptoms in adolescence. Externalizing problems in childhood were related to higher externalizing symptoms and substance use in adolescence as well as lower peer competence and GPA. In addition, the intervention had a direct positive effect on adolescent GPA. Baseline risk moderated the intervention effects on internalizing symptoms, substance use, and adaptive coping in adolescence such that the intervention was related to lower internalizing symptoms, lower substance use, and higher adaptive coping for those with higher baseline risk. Further, multigroup comparisons of the models across sex revealed that externalizing problems in childhood were positively related to internalizing symptoms in adolescence for females, standardized β = .33; unstandardized b = .43, SE = .12, z = 3.69, p ≤ .001, but not for males, β = .08; b = .09, SE = .15, z = .59, p = .56.

Adolescence to emerging adulthood

As shown in Figure 1, higher externalizing symptoms in adolescence were associated with lower work competence in emerging adulthood, β = -.18; b = -.10, SE = .05, z = -1.98, p = .048, and higher levels of adaptive coping were associated with higher work competence, standardized β = .16; b = .22, SE = .10, z = 2.23, p = .03. In addition to these paths, the intervention-induced improvements in positive parenting in childhood were positively related to work competence in emerging adulthood, β = .19; b = .46, SE = .19, z = 2.39, p = .02. After controlling for all of the intermediate variables in childhood and adolescence, the direct effect from the intervention on work competence was still significantly moderated by baseline risk, β = .32; b = .51, SE = .26, z = 1.98, p = .048, such that the intervention was related to higher work competence for youths with higher levels of baseline risk (e.g., at one standard deviation above the mean of baseline risk, β = .28; b = .84, SE = .39, z = 2.15, p = .03). Testing the mediation effects with the bias-corrected bootstrapping method showed that the mediation pathway of the intervention to positive parenting at posttest to externalizing problems in childhood to externalizing symptoms in adolescence to work competence was significant, mediation effect = .006, 95% CI [.001, .021]. In addition, the mediation pathway of the intervention to adaptive coping in adolescence to work competence was significant within a 90% confidence interval, mediation effect = .075, 90% CI [002, .228], for youths who had higher levels of baseline risk.

As shown in Figure 2, GPA in adolescence was positively related to academic competence in emerging adulthood, β = .44; b = 1.23, SE = .21, z = 5.90, p ≤ .001. The mediation pathway of the intervention to posttest positive parenting to externalizing problems in childhood to GPA in adolescence to academic competence was significant, mediation effect = .020, 95% CI [.005, .055].

As is shown in Figure 3, adaptive coping in adolescence was positively related to peer competence in emerging adulthood, β = .28; unstandardized b = .23, SE = .06, z = 3.63, p ≤ .001. Further, the mediation pathway of the intervention to adaptive coping in adolescence to peer competence was significant within a 90% confidence interval, mediation effect = .077, 90% CI [.007, .199], for youths with higher levels of baseline risk.

None of the paths from the variables in adolescence to romantic competence was significant. Analyses of sex differences showed that there were no significant differences in any of the paths from adolescent outcomes to the competence outcomes in emerging adulthood for any of the competence outcomes.

Discussion

This was the first study to test the effects of a relatively brief parenting-focused prevention program that was delivered during childhood on competence in emerging adulthood. Using a cascading effects model, the analyses examined competence in four salient developmental task domains of emerging adulthood: academic competence, work competence, romantic competence, and peer competence. The cascading effects tests were housed within a larger model in which positive cascade effects of the program occurred on mental health problems in childhood, which led to lower levels of mental health and other behavior problems as well as higher levels of competence in adolescence. Both direct and cascading significant effects of the program were found. For work competence, there was a significant direct effect of the intervention on work competence, which was stronger for those who entered the program at higher risk. Consistent with the organizational theory of development and person–environment transactional model, cross- and within-domain cascading effects were found. Cross-domain effects of externalizing problems and adaptive coping in adolescence were found for work competence. Also, adaptive coping in adolescence was related to peer competence. There was continuity in academic competence from adolescence to emerging adulthood, indicating that the earlier occurring cascade effects from parenting to externalizing problems to academic competence were sustained into adulthood. Because the analyses controlled for the longitudinal stability of functioning in these domains and for the within-assessment-period covariance among functioning in the domains that were assessed in adolescence, they provided conservative tests of these effects. Mediational analyses indicated that the intervention's effects on outcomes in emerging adulthood were partially accounted for by program-induced improvements that occurred in positive parenting in childhood, which led to improvements in externalizing problems, academic performance, and adaptive coping in adolescence. Below, we discuss the contributions of the study, how its findings relate to other work in the field, its limitations, and directions for future work.

Direct and Cascading Effects of the Intervention on Competence in Emerging Adulthood

Work competence

The domain of work is considered to be a developing area of competence in emerging adulthood (Masten, Desjardins, McCormick, Kuo, & Long, Reference Masten, Desjardins, McCormick, Kuo and Long2010; McCormick, Kuo, & Masten, Reference McCormick, Kuo, Masten, Fingerman, Berg, Smith and Antonucci2010; Roismann et al., Reference Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth and Tellegen2004). The program effects on work competence have important implications given the well-documented relation between success in the workplace and a wide array of outcomes in emerging adulthood and later developmental stages including occupational, financial, mental health outcomes as well as life satisfaction (Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo, & Mansfield, Reference Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo and Mansfield2012; Masten, Burt, & Coatsworth, Reference Masten, Burt, Coatsworth, Cicchetti and Cohen2006; Masten et al., Reference Masten, Desjardins, McCormick, Kuo and Long2010; Sampson & Laub, Reference Sampson and Laub1990; Scollon & Diener, Reference Scollon and Diener2006; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, Reference Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro2017). The intervention increased work competence in emerging adulthood for those with high risk at program entry. Although the effect size (d = .35) was small to medium, the potential contribution to improved public health could be sizeable if this intervention were widely disseminated. Previous analyses of the short-term and long-term effects of the intervention have found Baseline Risk × Intervention interaction effects on other outcomes (Christopher et al., Reference Christopher, Wolchik, Tein, Carr, Mahrer and Sandler2017; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, Winslow, Briesmeister and Schaefer2007). Similar interactive effects have been found for behavior problem outcomes in studies of other parenting-focused prevention programs (e.g., for a review see Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein & Winslow, Reference Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein and Winslow2015). Moreover, this result is congruent with findings from numerous passive studies implicating better parenting and family functioning as protective influences on the development of competence in at-risk children (Masten & Palmer, Reference Masten, Palmer and Bornstein2019).

In addition to this interactive effect, externalizing problems in adolescence were negatively associated with lower work competence. This finding is consistent with those of passive longitudinal studies (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, Reference Capaldi and Stoolmiller1999; Masten et al., Reference Masten, Desjardins, McCormick, Kuo and Long2010; Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter and Silva2001). Externalizing problems in adolescence may reduce environmental and interpersonal opportunities that promote competence in the work setting in emerging adulthood. Alternatively, it is possible that problems that are associated with externalizing problems, such as substance use or unreliability, may lead to later employment problems or that the continuity of externalizing problems may create interpersonal or behavior problems in the work setting that mitigate work competence in emerging adulthood. Adaptive coping in adolescence was significantly positively related to work competence. Adaptive coping includes problem solving and a sense of efficacy at handling problems, both of which may promote effective work functioning and management of stressors that occur in the workplace. Also, adolescents with higher levels of adaptive coping may also cultivate more positive employment and academic and interpersonal opportunities that lead to greater work competence. This finding is consistent with findings from studies of naturally occurring competence and resilience in the transition to adulthood (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Burt, Roisman, Obradović, Long and Tellegen2004).

In addition to these interactive and cascading effects, there was a significant positive path from intervention-induced improvements in parenting to work competence, suggesting that processes associated with positive parenting directly led to greater work competence in emerging adulthood. Perhaps by being more responsive, communicating more effectively, and having realistic expectations for their children's behavior, mothers in the intervention shaped behaviors that facilitated later success in the workplace. It may also be that higher quality parent–child relationships were associated with higher expectations and aspirations for success in work settings or mothers’ use of effective discipline increased their offspring's sense of being responsible for one's actions, which is likely associated with higher work competence.

Academic competence

By emerging adulthood, some individuals have completed their academic careers, whereas others are in the midst of completing college or advanced degrees. Given that educational attainment influences future employment (Johnson & Mortimer, Reference Johnson and Mortimer2011) and mid-life career and life satisfaction (Chow, Galambos, & Krahn, Reference Chow, Galambos and Krahn2017), a significant cascade effect from the program-induced effect on GPA in adolescence to educational attainment has implications for functioning beyond emerging adulthood. This within-domain continuity is consistent with the findings of passive, longitudinal research (French, Homer, Popovici, & Robins, Reference French, Homer, Popovici and Robins2015; Masten et al., Reference Masten, Roisman, Long, Burt, Obradović, Riley and Tellegen2005). This continuity may reflect the cumulative effect of early success on academic tasks to facilitate later academic competence through the use of skills and attitudes that are required for academic success as well as the stability of cognitive abilities and achievement motivation over development. This effect may also be partially due to the intervention's effects on educational expectations in adolescence (Sigal et al., Reference Signal, Wolchik, Tein and Sandler2012). Given the well-documented positive relation between educational level and earnings and the compounding of earning differences across the lifespan (Day & Newburger, Reference Day and Newburger2002), this program effect has important implications for reducing the public health burden of parental divorce.

Peer competence

Peer competence was significantly predicted by higher levels of adaptive coping in adolescence. It is possible that higher levels of adaptive coping are associated with skills that prevent, reduce, and resolve interpersonal problems. This finding and the finding that adaptive coping was associated with greater work competence extend the very limited literature on the relation between coping in adolescence and outcomes in adulthood (Hussong & Chassin, Reference Hussong and Chassin2004; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Tein, Sandler and Kim2016) by focusing on competence rather than behavior problems.

Romantic competence

Romantic competence in emerging adulthood was not affected by participation in the intervention either directly or indirectly through the aspects of adolescent functioning that were tested. Although there was a significant correlation between adaptive coping in adolescence and romantic competence, in the context of the other variables this relation became nonsignificant. The current findings are in contrast to other work that found that academic competence and peer competence around age 20 predicted romantic relationships at about age 30 (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, Reference Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth and Tellegen2004).

Mediational Pathways From Program Participation to Competence in Emerging Adulthood

The mediational analyses identified cascading effects pathways that partially explained the intervention's effects on three domains of competence in emerging adulthood. For peer competence, the indirect effects of the program were mediated by adaptive coping in adolescence for those who entered the program at high risk. For both work and academic competence, the long-term program effects were initiated by improvements in positive parenting at posttest, which led to cascading effects on externalizing problems in childhood and adolescence. In addition, for work competence, for those who entered the program at high risk, adaptive coping in adolescence mediated the long-term effect of the program. It is important to note that the power of detecting mediation effects with several mediators intervening in a series (i.e., cascade models) is smaller than the power of detecting mediation effects with only one mediator intervening between the independent and dependent variables (Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tein, Reference Taylor, MacKinnon and Tein2008). Therefore, the results of the mediational analyses support the robustness of the observed cascading effects.

The findings of the current study highlight the critical role of quality of parenting in promoting positive adaptation across development. These findings are consistent with a large body of cross-sectional and longitudinal research that has identified positive parenting as a key resilience resource (Baumrind, Reference Baumrind1971; Masten, Reference Masten2001; Masten et al., Reference Masten, Burt, Roisman, Obradović, Long and Tellegen2004; Masten & Palmer, Reference Masten, Palmer and Bornstein2019; Werner, Reference Werner, Goldstein and Brooks2013). They are also consistent with a growing body of studies that have demonstrated that program-induced improvements in parenting mediated program effects on long-term behavior problems through multilinkage effects (Forgatch et al., Reference Forgatch, Patterson, Degarmo and Beldavs2009; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Tein, Sandler and Kim2016).

Unique Contributions

This study contributes to the literature on the long-term effects of prevention programs as well as the long-term effects of parental divorce in several ways. First, it extends previous research on the long-term effects of relatively short, evidence-based parenting-focused programs that have examined problem behaviors such as mental health problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior (Sandler et al., Reference Sandler, Wolchik, Mazza, Gunn, Tein, Berkel and Porter2019; Spoth, Clair, & Trudeau, Reference Spoth, Clair and Trudeau2014; Spoth, Trudeau, Redmond, & Shin, Reference Spoth, Trudeau, Redmond and Shin2014; Trudeau et al., Reference Trudeau, Spoth, Mason, Randall, Redmond and Schainker2016; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Tein, Mahrer, Millsap, Winslow and Reed2013, Reference Wolchik, Tein, Sandler and Kim2016) by its focus on competence. It also extends the findings of the studies of comprehensive, lengthy prevention programs that have shown long-term effects on competence (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill and Abbott2005; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Robertson and Mann2001; Schweinhart et al., Reference Schweinhart, Montie, Xiang, Barnett, Belfield and Nores2005). Given the current emphasis on containing costs and ensuring that prevention programs achieve a reasonable return on investment (Forman et al., Reference Forman, Olin, Hoagwood, Crowe and Saka2009; Fosco et al., Reference Fosco, Seeley, Dishion, Smolkowski, Stormshak, Downey-McCarthy, Strycker, Weist, Lever, Bradshaw and Owens2014), the current findings have important implications for the potential effect on public health of the New Beginnings Program and other relatively short, evidence-based parenting interventions.

The second contribution relates to furthering our knowledge about the developmental processes that explain these long-term effects. In the early 1990s, Coie et al. (Reference Coie, Watt, West, Hawkins, Asarnow, Markman and Long1993) argued that the field of prevention science needs long-term follow-up of intervention samples to identify the processes that account for changes in outcomes across developmental stages. However, only a handful of researchers have done this (Forgatch, Patterson, Degarmo, & Beldavs, Reference Forgatch, Patterson, Degarmo and Beldavs2009; Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2011, Reference Reynolds and Ou2016; Spoth et al., Reference Spoth, Redmond, Shin, Greenberg, Feinberg and Schainker2013, Reference Spoth, Trudeau, Redmond and Shin2014; Trudeau et al., Reference Trudeau, Spoth, Mason, Randall, Redmond and Schainker2016; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Tein, Sandler and Kim2016), and nearly all of this research has focused on problem outcomes. The current study tracked developmental processes across three stages of development and identified links between program participation, parenting, changes in developmental processes in childhood and adolescence, and competence in emerging adulthood. This type of research not only strengthens causal inferences (Reynolds, Ou, & Topitzes, Reference Reynolds, Ou and Topitzes2004), it also furthers theories about the spreading effects of both problems and competence across development.

The third contribution is that this study experimentally tested the power of high-quality parenting to affect meaningful outcomes in emerging adulthood. The program-induced improvements generated cascading effects on developmental processes that led to increased competence in emerging adulthood. Although there is a large literature on the role of high-quality parenting in promoting positive development, few studies have experimentally manipulated the quality of parenting and examined the effect of these improvements across multiple periods of development, and even fewer have examined multiple domains of competence.

This study also contributes to research on the effects of parental divorce. Parental divorce is associated with impairments in competence in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Although other studies have found program effects on competence in earlier developmental periods (Crosbie-Burnett & Newcomer, Reference Crosbie-Burnett and Newcomer1990; Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, Reference Pedro-Carroll and Cowen1985; Wolchik et al., Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, Winslow, Briesmeister and Schaefer2007), this is the first study to show that a program for divorced families affected competence in emerging adulthood. That the program had effects on three of the four domains of competence that were examined and on outcomes that can be monetized, such as higher educational level and greater work competence, provides convincing evidence for the importance of disseminating this program.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are limitations of this study that need to be noted. First, there are several limitations related to the sample. The sample was almost exclusively non-Hispanic White and middle class. It is unclear whether these findings generalize to other sociocultural groups. Also, because the families were enrolled in a trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families that included multiple eligibility criteria, additional concerns are raised about the generalizability of the findings. Further, the participating mothers had higher incomes and education as well as fewer children than refusers. Finally, although the analytical strategy that was used to deal with missing data likely diminished the effects of attrition (Graham, Reference Graham2009), those who participated in the 15-year follow-up assessment had significantly higher internalizing problems and lower self-esteem than those who did not participate. These sample characteristics limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the sample was relatively modest, which reduced the power to detect direct and indirect effects of the program as well as interactive effects. Third, the intervals between assessments varied widely because data collection was determined by the length of the intervention and our interest in conducting short-term and long-term follow-ups.

There are several areas that could advance our understanding of the interplay between positive parenting, competence, problem behaviors, and substance use over development. Given the nature of the sample, replicating the current findings with larger, community-based samples that are more diverse would be important. Replication with other groups of at-risk youths is also important. In addition, research with larger samples would provide a more rigorous examination of sex differences in these cascading effects. Further, future research should examine whether other relatively short parenting programs have effects on competence in emerging adulthood. The increased attention to public return on investment (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009; Institute of Medicine, 2014) reinforces the importance of examining the long-term effects of these prevention programs on both problem behaviors and competence.

Summary

The current study demonstrated that a relatively brief parenting prevention program for divorced families improved offspring's competence in emerging adulthood. These program effects were accounted for by direct or indirect effects of program-induced improvements in quality of parenting. In the context of the previous studies on the New Beginnings Program, which have shown direct and indirect effects on a wide array of problem behaviors (Wolchik Reference Wolchik, WIlcox, Tain and Sandler2000, Reference Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein and Sandler2002, Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, Winslow, Briesmeister and Schaefer2007, Reference Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, Winslow, Briesmeister and Schaefer2013, Reference Wolchik, Tein, Sandler and Kim2016) and cost savings of about $1,600/family as assessed in the year prior to the 15-year follow-up (Herman et al., Reference Herman, Mahrer, Wolchik, Porter, Jones and Sandler2015), the positive cascade effects of this program across developmental stages have important public health implications. Given the large number of children who experience parental divorce in the United States each year, the widespread implementation of the New Beginnings Program could significantly reduce the public health burden of parental divorce.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941900169X.