Socioeconomic status (SES), often measured by income, occupation, and education, is a matter of access to and distribution of resources, with low SES, or poverty, equating to low access to and availability of resources (Hackman, Farah, & Meaney, Reference Hackman, Farah and Meaney2010; Vidyasagar, Reference Vidyasagar2006). According to recent reporting from the US Census Bureau, nearly 20% of families with children under the age of 18 are living below the federal poverty threshold (US Census Bureau, 2015). Children living in poverty are more likely to experience a scarcity of material resources, less parental nurturance, greater family instability, more crowded homes, elevated stress levels, increased exposure to violence, and less cognitive stimulation (Evans, Reference Evans2004). Impoverished children are also at greater risk for exposure to poorer quality diets, as well as air and water pollution (Darmon & Drewnowki, Reference Darmon and Drewnowski2008). Thus, poverty greatly increases the potential for children and families to experience a host of adverse exposures. In turn, exposure to these poverty-related risk factors increases the likelihood of poor neurobehavioral development, including cognitive and social–emotional, behavioral, and physical health problems (Yoshikawa, Aber, & Beardslee, Reference Yoshikawa, Aber and Beardslee2012). Such developmental outcomes ultimately contribute to greater risk of poor academic achievement and worse employment outcomes throughout life (Barnett, Reference Barnett1998; Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, Reference Brooks-Gunn and Duncan1997; Duncan, Ziol-Guest, & Kalil, Reference Duncan, Ziol-Guest and Kalil2010).

Human studies have established a general association between poverty and brain development, with developmental imaging studies providing great insights into the potential neural consequences of poverty in early life (for review, see Johnson, Riis, & Noble, Reference Johnson, Riis and Noble2016). On average, findings provide evidence of slower trajectories of brain growth and lower volumes of gray matter in children living in poverty (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Hair, Shen, Shi, Gilmore, Wolfe and Pollak2013). In addition, low SES is associated with smaller hippocampi (Staff et al., Reference Staff, Murray, Ahearn, Mustafa, Fox and Whalley2012), and less regulated prefrontal cortex and amygdala activation during emotion processing tasks (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Evans, Angstadt, Shaun Ho, Sripada, Swain and Luan Phan2013). Thus, infants may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of low SES, perhaps due to their heightened, rapid brain development and the role of early life experience in sculpting brain structure and function (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Hair, Shen, Shi, Gilmore, Wolfe and Pollak2013; Johnson, Reference Johnson2001; Noble, Houston, Kan, & Sowell, Reference Noble, Houston, Kan and Sowell2012). However, further research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which poverty can influence brain development, particularly in infancy, and to connect brain development with behavioral development. Identifying neurobehavioral phenotypes in the earliest stages of development can potentially provide invaluable insight into the mechanisms by which poverty can affect development.

The specific mechanisms by which poverty affects neurobehavioral development remain unclear and are challenging to disentangle given the variety of poverty-related risks ranging from psychosocial to ecological factors (Evans, Reference Evans2004). However, thus far, a majority of studies exploring possible pathways by which poverty impacts development have focused on family psychosocial characteristics, and parenting quality in particular (Blair & Raver, Reference Blair and Raver2016). Results of these studies largely support a mediating role of parenting quality as it relates to the influence of environmental scarcity-adversity and early life indicators of later life social–emotional and cognitive competence (Gee, Reference Gee2016; Perry, Blair, & Sullivan, Reference Perry, Blair and Sullivan2017; Tang, Reeb-Sutherland, Romeo, & McEwen, Reference Tang, Reeb-Sutherland, Romeo and McEwen2014; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015). Specifically, stressful rearing environments place parents at risk for less sensitive caregiving (Asok, Bernard, Roth, Rosen, & Dozier, Reference Asok, Bernard, Roth, Rosen and Dozier2013; Finegood et al., Reference Finegood, Blair, Granger, Hibel and Mills-Koonce2016; McLoyd, Reference McLoyd1998). In turn, this lower caregiving quality has been shown to mediate the effects of adversity on child outcomes, including emotion dysregulation, behavioral problems, and executive function (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Granger, Willoughby, Mills-Koonce, Cox and Greenberg2011; Mills-Koonce et al., Reference Mills-Koonce, Willoughby, Garrett-Peters, Wagner and Vernon-Feagans2016; Raver, Roy, Pressler, Ursache, & McCoy, Reference Raver, Roy, Pressler, Ursache and McCoy2016).

On a physiological level, adversity is associated with disrupted regulation in both parents and infants. This includes altered regulation of the physiological response to threat, primarily as indicated by activity in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Blair, Willoughby, Granger and Mills-Koonce2017; Blair et al., Reference Blair, Granger, Kivlighan, Mills-Koonce, Willoughby and Greenberg2008) and connectivity among brain areas important for physiological and behavioral regulation (Jedd et al., Reference Jedd, Hunt, Cicchetti, Hunt, Cowell, Rogosch and Thomas2015; Luby et al., Reference Luby, Belden, Botteron, Marrus, Harms, Babb and Barch2013). Furthermore, regulation of infant physiology by way of sensitive caregiving has been proposed to provide early life programming, which guides appropriate socioemotional and cognitive development (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Blair and Sullivan2017). Together, these findings suggest that the quality of parental care is critical for guiding optimal socioemotional and cognitive development. Improving parenting quality despite environmental adversity has become the central goal of many intervention efforts for low SES families, such as the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (Bernard, Meade & Dozier, Reference Bernard, Meade and Dozier2013) and Play and Learning Strategies interventions (Landry, Smith, Swank, & Guttentag, Reference Landry, Smith, Swank and Guttentag2008). Further research is needed, however, to understand the neurobiological mechanisms by which parenting quality guides infant development.

Overall, while human studies have provided strong support for the hypothesis that parenting quality is at least one pathway by which socioeconomic adversity influences infant development, these studies are primarily observational or correlational. Some intervention studies have utilized randomized controlled trials to assess relationships between caregiver interventions and outcomes (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindheim and Carlson2012; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Zeanah, Fox, Marshall, Smyke and Guthrie2007). Even in these studies, however, experimenters could not control the initial selection process of research participants into poverty conditions, nor the participants' histories or other potentially confounding variables. Thus, human studies are fundamentally limited in establishing causation to inform mechanisms by which poverty-related adversity influences development. Human researchers also face technical challenges when it comes to the assessment of neurobiological correlates of poverty in young infants. Finally, human research studies primarily employ a “cumulative risk” approach to studying low SES, by assessing the cumulative influence of poverty-related risk factors (ranging from ecological to psychosocial) on development. More specifically, a cumulative risk approach creates a risk score by totaling exposure to a range of distinct adverse experiences. Even with its strengths, this approach is unlikely to disentangle specific mechanisms by which different aspects of poverty-related adversity influence development (Evans, Li, & Whipple, Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013).

To address these challenges, our field has increasingly turned to animal models of early life adversity. While there are limitations to animal models (such as the inability to fully model social and cultural phenomena), their use in conjunction with human research can isolate candidate mechanisms for cause–effect relationships between poverty-related variables and neurobehavioral development (Hackman et al., Reference Hackman, Farah and Meaney2010; Poldrack & Farah, Reference Poldrack and Farah2015; Thapar et al., Reference Thapar, Rutter, Thapar, Pine, Leckman, Scott, Snowling and Taylor2015). Animal models allow for the controlled manipulation of poverty-related variables in a way that cannot be achieved with humans. Furthermore, they allow for random assignment of subjects into group conditions, giving experimenters the ability to control the selection process into poverty-like conditions. Based on this, the experimenter has the ability to rule out potential confounding variables related to subjects' histories and timing of exposure to adversity leading up to testing, which pose challenges to the study of poverty in human samples. Animal models also provide technical advantages when it comes to assessing neurobiological, genetic, and epigenetic mechanisms by which early life adversity influences parenting style and infant development. Understanding such mechanisms is central to disentangling the directionality and cause–effect nature of relationships between exposure to poverty, an individual's attributes (i.e., genetics), and experience-driven and/or intergenerational changes (i.e., epigenetics). Finally, through the use of animal models, researchers can create and experimentally test taxonomies of early life adversity in order to understand how different dimensions of adversity influence different aspects of development (Sheridan & McLaughlin, Reference Sheridan and McLaughlin2014). For example, our field recently witnessed a renewed effort to create animal models that will allow for the study of effects of early life deprivation separately from the effects of early life threat on neurobehavioral development (McLaughlin & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan2016). Of note, while poverty is commonly categorized as a form of deprivation, it is increasingly recognized as an indicator of exposure to threat as well (Blair & Raver, Reference Blair and Raver2016; McLaughlin, Sheridan, & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014). Thus, the strict orthogonalization of deprivation and threat using animal models may not be ideal for modeling poverty-related adversity in a translationally meaningful way. Altogether, the comparative strengths and weaknesses of human and animal research underscore the need for animal models of poverty-related adversity that maintain high translational validity, while permitting assessment of causal mechanisms using multiple levels of analyses.

Thus far, animal researchers have failed to develop animal models that are optimized to inform mechanisms by which poverty affects neurobehavioral development. Therefore, the present study tested a novel application of a previously developed animal model to evaluate its appropriateness for studying developmental processes as a function of poverty-related adversity exposure. Specifically, we leveraged a “limited bedding” rodent protocol, which was originally developed as a model of chronic early life stress (Raineki, Moriceau, & Sullivan, Reference Raineki, Moriceau and Sullivan2010; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Bath, Joels, Korosi, Larauche, Lucassen and Baram2017). In this model, rodent families (the dam and her offspring) are supplied with insufficient nesting materials, so that the mother cannot build a proper nest for her pups (Perry & Sullivan, Reference Perry and Sullivan2014). In keeping with current efforts to create taxonomies appropriate for measuring the effects of specific dimensions of adversity on development, this study utilized a domain-specific approach by modeling resource depletion to create conditions of scarcity-adversity. Following random assignment of rodent dams and her pups into control versus scarcity-adversity rearing environments, we measured the impact of resource depletion on caregiving quality, and pup neurobehavioral development, which was determined using early life neurobehavioral indicators of later life social–emotional and cognitive competence (Landers & Sullivan, Reference Landers and Sullivan2012). Furthermore, we assessed the ecological validity of this rodent model by considering our rodent findings to a parallel set of analyses that we conducted with a large sample of children and families (N = 1,292) followed longitudinally from birth in predominantly low-income and nonurban communities in the United States (Vernon-Feagans & Cox, Reference Vernon-Feagans and Cox2013). In this human study, we adopted a similar “cumulative risk” approach to what has been previously used. However, we created a targeted “scarcity-adversity” risk index related to indicators of resource depletion only, with the aim of identifying a domain-specific mechanism through which poverty-related risk affects child development. Furthermore, we assessed the extent to which this cumulative risk index significantly predicted parenting quality, and through parenting quality we tested key measures of infant social–emotional and cognitive competence. Thus, this cross-species approach allows for the assessment of process-level similarities and differences between species as it relates to scarcity-adversity exposure, parenting quality, and infant social–emotional and cognitive development. Through the use of cross-species research, we explore the potential for scientifically advancing the understanding of mechanisms by which poverty impacts development.

Methods

Rodent

Subjects

Male and female Long–Evans rats (originally from Harlan, IN) were born and bred in our colony using multiparous mothers, which are preferred because they increase the consistency of maternal care relative to primiparous mothers (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Bath, Joels, Korosi, Larauche, Lucassen and Baram2017). On the day of birth, infants were considered postnatal day (PN) 0, and litters were culled to 12 infants each (6 male, 6 female) on PN1. Infants were housed in a light and temperature controlled room (20 ± 1 °C, 12 hr light/dark cycle) in polypropylene cages (34 × 29 × 17 cm) with their mother. Animals had ad libitum access to food (Purina LabDiet #5001) and water.

Scarcity-adversity treatment

Litters were randomly assigned to control or scarcity-adversity conditions a week after birth. In control conditions, mothers were provided with abundant wood shavings materials (4-cm layer), so that they were able to build nests for their pups, which served as a secure base for the pups and the center for caregiving. In scarcity-adversity conditions, mothers were provided with scarce amounts of wood shavings materials (100 ml shavings, <1 cm layer), so that the mothers could not build a proper nest for their pups (see Figure 1a). Litters were exposed to scarcity-adversity conditions from PN8 to PN12. This age of exposure was based on prior research that tested this model over a variety of different intervals in early development (i.e., PN1–7, 2–9, 3–8, 8–12, or 10–14) and demonstrated that the scarcity-adversity model produces the greatest impact on neurobehavioral development from PN8 to PN12 (for review, see Walker et al., Reference Walker, Bath, Joels, Korosi, Larauche, Lucassen and Baram2017). This age range begins during the rodent pup's sensitive period for attachment (before PN10), and continues into an age range when the mother has significant effects on regulation of pups' neurobehavioral function (after PN10; Moriceau & Sullivan, Reference Moriceau and Sullivan2006; Sarro, Wilson, & Sullivan, Reference Sarro, Wilson and Sullivan2014). Scarcity-adversity exposure was terminated at the end of PN12, because pups then enter an age range of reduced impact by maternal care. However, terminating scarcity-adversity conditions also allowed for the experimenter to be blind to early life rearing conditions during testing at PN14 (±1 day). Each subject was tested only once. All procedures were approved by our institute's Animal Care and Use Committee, in accordance with the National Institutes of Health's guidelines.

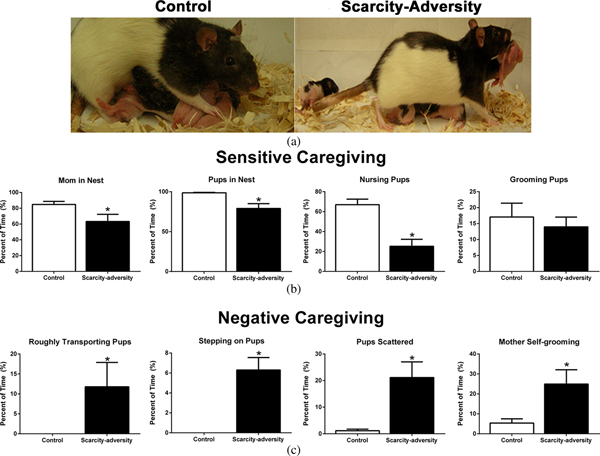

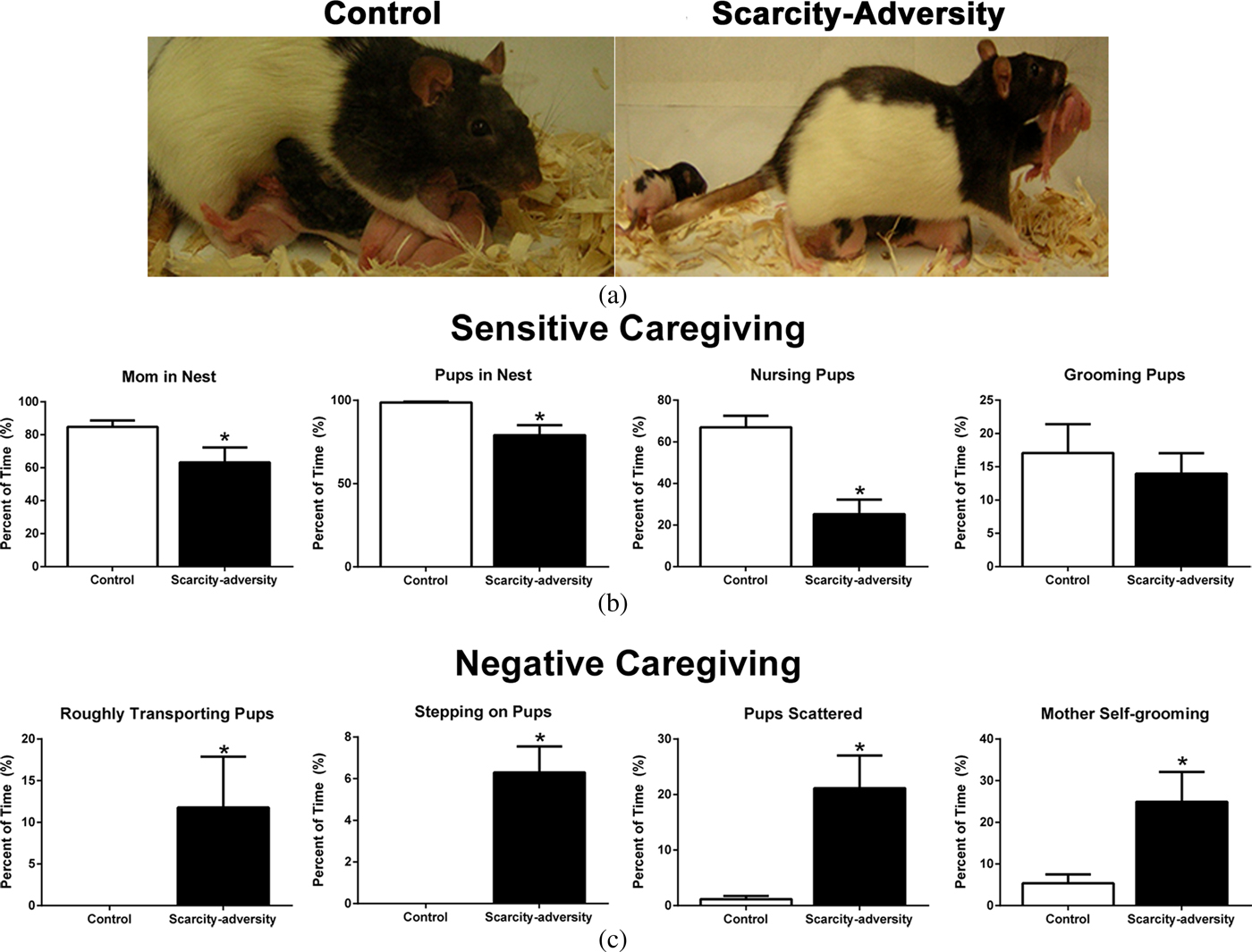

Figure 1. A rodent model of scarcity-adversity decreased sensitive caregiving and increased negative caregiving. (a) Using a rodent model, litters were randomly assigned to control conditions (left), with ample bedding needed by the mother for nest building, or to scarcity-adversity conditions (right), where mothers were provided with insufficient nest-building materials. These environmental conditions directly influenced maternal behavior. For example, in the image on the left, a mother is shown nursing her pups in an arch-back position, which applies the least amount of pressure on her pups. In the image on the right, a mother is depicted stepping on her pups while carrying a pup in her mouth by its limb. (b) Scarcity-adversity conditions caused a decrease in multiple measures of sensitive caregiving, relative to control conditions, as indicated by the percent of time mothers spend in the nest with their pups, nursing their pups, as well as the percent of time all pups are present in the nest (n = 10–11/group, *p < .05). (c) Scarcity-adversity conditions caused an increase in measures of negative caregiving, relative to control conditions. These measures include the percent of time mothers spent roughly transporting their pups (i.e., carrying pup by limb), stepping on pups, and self-grooming, as well as the percent of time pups were scattered throughout the home cage (n = 10–11/group, *p < .05).

Mother–infant interaction: Caregiving behaviors

Interactions between the rodent mothers and pups were observed in a 30-min nonstructured assessment of behavior within the home cage during control and scarcity-adversity conditions. The interaction was video recorded and later coded by trained coders to assess levels of caregiving behaviors. Maternal behavior was scored for 30-min observation periods on 3 days (PN8; PN9, 10, or 11; and PN12) by experienced researchers using Cowlog software (www.cowlog.org). Nurturing caregiver behaviors that ensure survival of offspring and attachment formation were categorized as “sensitive” and included the mother's presence in the nest with her pups, keeping pups together in the nest, nursing, and grooming (Rilling & Young, Reference Rilling and Young2014; Table 1). Caregiver behaviors categorized as “negative” included behaviors that placed the pup at increased risk of threat (rough transport of pups and stepping on pups) or deprivation (pups scattered throughout home cage and mother self-grooming; Drury, Sanchez, & Gonzalez, Reference Drury, Sanchez and Gonzalez2016; Table 1). While self-grooming is a common animal behavior serving the primary purpose of hygiene and thermoregulation (Sprujit, van Hooff, & Gispen, Reference Sprujit, van Hooff and Gispen1992), increased self-grooming occurs as a result of increased stress hormones (D'Aquila, Peana, Carboni, & Serra, Reference D'Aquila, Peana, Carboni and Serra2000; Dunn, Berridge, Lai, & Yachabach, Reference Dunn, Berridge, Lai and Yachabach1987). Thus, we coded mother self-grooming to allow for the assessment of altered levels of self-grooming as a function of scarcity-adversity exposure, where heightened self-grooming reflects a negative caregiving style indicative of increased stress and decreased time interacting with pups.

Table 1. Rodent caregiving behaviors

To assess caregiving behaviors in undisturbed conditions within the home cage, coders could not be blinded to control versus scarcity-adversity conditions (home cage wood shavings levels were visible in the video recording). However, the mother's presence in the nest was verified using automated tracking software (Ethovision, Noldus). Further assessment of pup interactions with the mothers (described below) were conducted in semistructured and structured environments, outside of the home cages, by experimenters blind to rearing conditions.

Nipple attachment test

Infant rat pups require maternal odor to attach to their mother's nipples for nursing. Without maternal odor, nipple attachment does not occur (Hofer, Shair, & Singh, Reference Hofer, Shair and Singh1976; Teicher & Blass, Reference Teicher and Blass1977). Here we tested the ability of maternal odor to guide nipple attachment following control and scarcity-adversity rearing, through the use of a semistructured nipple attachment test conducted by experimenters blind to rearing conditions. Mothers were anesthetized with urethane (2 g/kg, intraperitoneally) prior to testing, to prevent milk letdown. For this test, the natural maternal odor was eliminated from the mother's ventrum and reintroduced into the testing environment via an airstream infused from underneath a mesh floor supporting the mother and pup. To remove the natural maternal odor, the ventrum of the mother was washed with acetone, alcohol, and water, (Hofer et al., Reference Hofer, Shair and Singh1976; Teicher & Blass, Reference Teicher and Blass1977). The washed mother was then placed on her side in the testing cage (25 × 40 × 20 cm), so that the pups had access to her nipples, and the odor from a separate lactating female was delivered via a flow dilution olfactometer (2 l/min flow rate, 1:10 odor:air, 4 min intertrial interval [ITI]) from under the mesh floor. The pup was then placed on the opposite side of the chamber, and latency to attach to a nipple and time spent attached to the nipple was recorded during the 3-min test, by a researcher blind to experimental conditions (Raineki, Moriceau et al., Reference Moriceau, Roth and Sullivan2010; Rincón-Cortés et al., Reference Rincón-Cortés, Barr, Mouly, Shionoya, Nunez and Sullivan2015; Sarro et al., Reference Sarro, Wilson and Sullivan2014). Maternal odor is diet dependent, and thus pups cannot distinguish between the odor of their own mother or another mother on the same diet (Leon, Reference Leon1975, Reference Leon, Muller-Schware and Silverstein1980; Sullivan, Wilson, Wong, Correa, & Leon, Reference Sullivan, Wilson, Wong, Correa and Leon1990).

Y-maze testing of approach/avoidance

In a structured test of pup behavior, a Y-maze test was used to assess infant preference or aversion to maternal odor. The subject was placed in a start box (10 × 8.5 × 8 cm), which was separated from two equal-length arms (24 × 8.5 × 8 cm) by sliding doors. The end of one arm contained maternal odor (from a lactating female), while the end of the second arm contained a control odor (clean wood shavings). The biological maternal odor was delivered via a flow dilution olfactometer (2 l/min flow rate, 1:10 odor:air, 4 min ITI), and the control odor was a familiar odor of clean wood shavings (20 ml) in a petri dish. Maternal odor is diet dependent, and thus pups will approach any lactating mother on the same diet as their own mother (Leon, Reference Leon1975, Reference Leon, Muller-Schware and Silverstein1980; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Wilson, Wong, Correa and Leon1990). Following a 5-s holding period in the start box, the sliding doors were lifted and the pup was given 1 min to make a choice. It was considered a choice when the entire body of the subject entered the alleyway of an arm. The subject was given a total of five trials to select between maternal odor and the control odor, and all trials were conducted by a researcher blind to experimental conditions (Moriceau, Shionoya, Jakubs, & Sullivan, Reference Moriceau, Shionoya, Jakubs and Sullivan2009; Raineki, Moriceau, et al., Reference Moriceau, Roth and Sullivan2010; Raineki et al., Reference Raineki, Sarro, Rincón-Cortés, Perry, Boggs, Holman and Sullivan2015; Sullivan & Wilson, Reference Sullivan and Wilson1991).

Ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs)

Similar to human crying, infant USV is a valid measure of pup distress, and serves an important communicative role in eliciting caregiving behaviors (Branchi, Santucci, & Alleva, Reference Branchi, Santucci and Alleva2001). In this structured assessment of infant USVs outside of the nest, USVs were recorded for 1 min while pups were isolated in a beaker (2000 ml), and then for an additional 1 min once being placed with an anesthetized mother, with all testing occurring in a temperature-regulated room (32 °C) by an experimenter blind to experimental conditions. The mother was anesthetized with urethane (2 g/kg, intraperitoneally), and placed with her abdomen against the bottom and side of the testing cage to prevent the possibility of pups attaching to her nipples during the test (Hofer & Shair, Reference Hofer and Shair1978). All recordings were made following a 1-min habituation period, using an Ultramic 200k USB microphone (Dodotronic), with a 200-kHz sampling rate, and USVs were visualized using SeaWave (CIBRA) software. Spectral analysis of USV data was performed using the Spectral Analysis Toolbox from the open source code repository Chronux (chronux.org). The code was implemented using MATLAB (MathWorks) and utilized a moving window, multi-taper spectral analysis. A detailed description and validation of these specific procedures is provided elsewhere (Bokil, Andrews, Kulkarni, Mehta, & Mitra, Reference Bokil, Andrews, Kulkarni, Mehta and Mitra2010; Mitra & Bokil, Reference Mitra and Bokil2008). Moving windows were set to 300 ms and 100 ms. Sampling frequency of the USV data was 200 kHz, meaning that the Nyquist frequency of the computation (100 kHz) was well above the target frequency band of 30–60 kHz, which is the frequency at which pups elicit “distress” calls, such as when socially isolated (Cacioppo, Hawkley, Norman, & Berntson, Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley, Norman and Berntson2011; Hofer, Reference Hofer1996; Insel, Hill, & Mayor, Reference Insel, Hill and Mayor1986; Shair, Reference Shair2007). Following computation of the spectral analysis, data in the 30- to 60-kHz band were isolated during the second minute of data recording under all four conditions. Total spectral power in the frequency band was calculated in decibels (dB). The mother's ability to reduce infant USV emission was calculated as the percent reduction of USV power (dB) from the socially isolated condition to the anesthetized mother condition ([dB alone – dB with mom] / dB alone × 100). All recordings and data processing were conducted by experimenters blind to rearing conditions

Neurobiology

Infant brain activity in response to maternal odor presentations was assessed using 14C 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) autoradiography (Boulanger Bertolus et al., Reference Boulanger Bertolus, Hegoburu, Ahers, Londen, Rousselot, Szyba and Mouly2014; Debiec & Sullivan, Reference Debiec and Sullivan2014; Landers & Sullivan, Reference Landers and Sullivan1999; Moriceau et al., Reference Moriceau, Shionoya, Jakubs and Sullivan2009; Sullivan, Landers, Yeaman, & Wilson, Reference Sullivan, Landers, Yeaman and Wilson2000; Sullivan & Wilson, Reference Sullivan and Wilson1995), which provides data that permits functional assessment of the brain that is similar to positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging (Casquero-Veiga et al., Reference Casquero-Veiga, Hadar, Pascau, Winter, Desco and Soto-Montenegro2016; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Rincón-Cortés, Raineki, Sarro, Colcombe, Guilfoyle and Castellanos2017). Five minutes prior to maternal odor presentations, pups were injected with 14C 2-DG (20 μCi/100g, subcutaneous injection), which allows labeling of cells via 14C 2-DG uptake into active cells. Pups were then placed individually into beakers (2000 ml), where they received 11 maternal odor presentations delivered via a flow dilution olfactometer (2 l/min flow rate, 1:10 odor:air, 4 min ITI) controlled by Ethovision software (Noldus). The natural maternal odor was sourced from two anesthetized mothers that were placed in an airtight chamber connected to the flow dilution olfactometer (Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan, & Wilson, Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016). Brains were dissected following the end of odor presentations, and stored in a −80 °C freezer before being sectioned in a cryostat (20 μm) at −20 °C. Every other brain section was collected onto a cover slip and exposed to X-ray film (Kodak) for 5 days with 14C standards (10 × 0.02 mCi, American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc.; Coopersmith, Henderson, & Leon, Reference Coopersmith, Henderson and Leon1986; Sullivan & Wilson, Reference Sullivan and Wilson1995). ImageJ software (NIH), which is a computer-based system for quantitative optical densitometry, was used to compute levels of brain activity in brain regions of interest (ROI). To compute 2-DG uptake, autoradiographic density was measured in both hemispheres of the brain within each ROI (described below), and then averaged across both hemispheres. All 2-DG uptake measures were expressed relative to 2-DG uptake in the corpus callosum to control for differences in section thickness or exposure levels (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Landers, Yeaman and Wilson2000). A total of four brain sections per ROI were analyzed per animal, and the reported results reflect an average of relative 2-DG uptake across all four sections. An increase in autoradiographic density indicates increased neural activation but does not differentiate between inhibitory and excitatory activity. All experiments and analyses were conducted by a data collector blind to experimental conditions. Our neurobiological assessment focused on developing olfactory–limbic brain regions underlying attachment learning and social–emotional and cognitive development in humans and rodents (Callaghan, Sullivan, Howell, & Tottenham, Reference Callaghan, Sullivan, Howell and Tottenham2014; Landers & Sullivan, Reference Landers and Sullivan2012; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Blair and Sullivan2017; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015), as well as areas thought to be vulnerable to impact from scarcity rearing (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Hair, Shen, Shi, Gilmore, Wolfe and Pollak2013; Johnson, Reference Johnson2001; Noble et al., Reference Noble, Houston, Kan and Sowell2012; Rincón-Cortés & Sullivan, Reference Rincón-Cortés and Sullivan2016). All odor presentations and image analysis were conducted by experimenters blind to rearing conditions.

Anterior piriform cortex (aPCX)

NIH ImageJ software was used to measure 2-DG uptake within the olfactory cortex (aPCX), by using a stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos & Watson, Reference Paxinos and Watson1986) to outline the region. Anatomical landmarks within aPCX were visible in the autoradiographs, and thus no cresyl violet staining was required for analysis.

Amygdala and hippocampus

Anatomical landmarks within the amygdala and hippocampus were not visible in the autoradiographs. Therefore, specific nuclei and anatomical landmarks were identified by staining brain sections with cresyl violet following exposure, which were used to make template overlays for the autoradiographs (Debiec & Sullivan, Reference Debiec and Sullivan2014; Moriceau et al., Reference Moriceau, Shionoya, Jakubs and Sullivan2009; Raineki, Holman, et al., Reference Raineki, Holman, Debiec, Bugg, Beasley and Sullivan2010). Analyses within the amygdala and hippocampus included medial, basolateral, central, and cortical nuclei of the amygdala, as well as CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus of the dorsal hippocampus.

Prefrontal cortex (PFC)

Cresyl violet staining was not used for analysis of the PFC because anatomical landmarks were visible in the autoradiographs. Rather, brain areas were outlined with the aid of a stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos & Watson, Reference Paxinos and Watson1986). Analyses within the PFC included the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, prelimbic cortex, and infralimbic cortex.

Functional connectivity network analyses

Relative 2-DG uptake data across individual animals was calculated for the aPCX, amygdala (average of medial, basolateral, central, and cortical nuclei), hippocampus (average of CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus), and PFC (average of anterior cingulate cortex, prelimbic cortex, infralimbic cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex). Pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients were then calculated for all possible combinations of brain regions for each animal, and transformed into Fisher z values to allow quantitative analyses of functional connectivity (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016). Fisher z values greater than 0.5 were considered to be meaningful measures of functional connectivity between brain ROIs.

Statistical analyses

Behavioral and 2-DG ROI data were analyzed by analysis of variance, followed by Fisher post hoc tests between individual groups, or Student t tests in cases with only two experimental groups. For functional connectivity network analyses, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were converted to z score values using Fisher r-to-z transformation, and z scores were compared and analyzed for statistical significance by calculating the observed z test statistic formula: (z observed = [z 1 + z2] / [square root of {1 / N 1 – 3} + {1 / N 2 – 3}]). All differences were considered significant when p < .05.

Human

Participants

Data were from the Family Life Project (FLP), a population-based, longitudinal study of 1,292 children and their primary caregivers (99.61% biological mothers) living in low-income rural communities in eastern North Carolina (NC) and central Pennsylvania (PA). Families were recruited in local hospitals shortly after the birth of the target child, oversampling low-income families in both states and African American families in NC. A detailed description of the sampling plan and recruitment procedures has been published elsewhere (Vernon-Feagans & Cox, Reference Vernon-Feagans and Cox2013). The data presented here come from a series of data collected in families' homes when infants were approximately 2, 6, and 15 months of age. Home visits were completed by two trained home visitors, lasting 2–3 hr and included self-reported measures and semistructured interviews assessing household characteristics, family demographics, and infant behavior, as well as a mother–infant interaction task.

For this sample, 59.8% of families resided in NC, and 40.2% resided in PA, with 57% of the study population being Caucasian, the remaining 43% African American. At 6 months postpartum, mothers were on average 26.37 years of age (±6.12 years), and infants were on average 0.64 years old (±0.12), and near evenly split as male (49.10%) and female (50.9%). On average, families lived approximately 192% above the poverty level (income-to-needs ratio [INR] = 1.92) with 34% of families living in poverty (INR <= 1.0) and half of those families, 17%, in deep poverty (INR <= 0.50).

Scarcity-adversity exposure

Scarcity-adversity exposure was assessed by creating a composite poverty-related risk index. As with prior analyses of the FLP (Vernon-Feagans & Cox, Reference Vernon-Feagans and Cox2013), we computed a cumulative risk composite of six variables measured at 6 months: family INR, economic strain, household density, neighborhood noise/safety, maternal education, and consistent partnership of a spouse/partner living in the home. A continuous cumulative risk index was generated by reverse-scoring the positively framed indicators, standardizing each risk measure, and averaging the standardized variables. Correlation coefficients among the six indicators included in the cumulative risk index ranged from r = .13 to .53, p < .001.

Parent–infant interaction: Parenting behaviors

Interactions between primary caregivers and their infants were observed in a 10-min semistructured, free-play task during the 15-month home visit. In this task, primary caregivers were instructed to play with their infant using a provided set of standardized toys. The interaction was video recorded and later coded by highly trained coders to assess levels of primary caregivers' sensitivity (responses to infant's signals of physical and emotional needs), detachment (emotional involvement and level of physical activity with infant, e.g., rarely making eye contact), intrusiveness (degree to which the caregiver imposed their agenda on their infant), stimulation (cognitive stimulation of infant), positive regard (expression of positive affect and delight in interacting with infant), negative regard (expression of negative affect), and animation (enthusiasm for infant; Cox & Crnic, Reference Cox and Crnic2002; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 1999). Each behavioral dimension was coded using a scale from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 5 (highly characteristic) by a team of coders, which included a master coder. Coders underwent training with their master coder until acceptable reliability was established, as determined by intraclass correlation coefficients (>0.80). Once acceptable reliability was established, coders coded in pairs while continuing to complete at least 30% of the videos with their master coder. Each coding pair met biweekly to reconcile scoring discrepancies, and the scores used in analysis were the final scores arrived at after reconciling.

Two distinct dimensions of parenting behavior emerged from principle factor analyses of parenting measures conducted with an oblique rotation (i.e., Promax) at each time point. These dimensions included sensitive parenting (the average of sensitivity, stimulation, positive regard, detachment [reversed], and animation) and negative parenting (the average of detachment, intrusiveness, and negative regard; Mills-Koonce et al., Reference Mills-Koonce, Garrett-Peters, Barnett, Granger, Blair and Cox2011; Vernon-Feagans & Cox, Reference Vernon-Feagans and Cox2013).

Infant affect

Interactions between primary caregivers and their infant were observed in a 10-min semistructured, free-play task during the 15-month home visit, as described above. Videos were coded for infant positive affect (infant satisfied, content, or pleased with overall situation) and negative affect (infant fussing, frowning, tensed body, or discontent). Each behavioral dimension was coded using a scale from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 5 (highly characteristic) by a team of four to five coders. Coders were trained by a master coder, before formally coding in pairs as described above. Each coder maintained an intraclass correlation of 0.80 or higher to their master coder and completed at least 30% of the videos with their master coder.

Infant mental development

The Mental Development Index (MDI) was measured using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development—II (Bayley, Reference Bayley1993), which was administered at the 15-month time point. The Bayley Scales of Infant Development—II is the most widely used measure of cognitive developmental status for children in the first 2 years of life. The MDI is a standard series of developmental tasks that measures children's cognitive skills in infancy. These scores are norm-referenced standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15).

Infant attention

At the 15-month home visit, infant attention was assessed using a subscale from an adaptation of the Infant Behavior Record (Bayley, Reference Bayley1969). The Infant Behavior Record was applied to behavior observed globally across the entire home visit (Stifter & Corey, Reference Stifter and Corey2001). Ratings were completed independently by both home visitors whose scores were averaged. For the attention subscale α = 0.88.

Covariates

To control for site differences in study variables, state of residence (PA = 0, NC = 1) was included as a covariate. Additional demographic covariates included the primary caregiver's report of the sex (Male = 0, Female = 1), and race (African American = 1, not African American = 0) of their infant during the 2-month home visit, as well as the reported age of the primary caregiver and their infant at the time of the 6-month visit.

Missing data

The full sample of the FLP consisted of 1,292 families at the time of study entry, with 1,204 families seen at 6 months postpartum and 1,169 families seen at 15 months postpartum. To assess possible differential attrition in the sample at each time point, we examined a number of variables for which we had complete information collected at infant age of approximately 2 months. Few variables indicated differences between families who were present and those who were missing at each time point. Complete information on missing data is available from the first author upon request.

Participants were included in the analysis if they had nonmissing data on at least one or more assessments of parenting, infant affect, infant mental development, or infant attention, resulting in an analytic sample of N=1,169, which was used in all analyses. All models were specified and fitted using full information maximum likelihood estimation, to reduce potential bias in estimates related to missing data (Enders, Reference Enders2010).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses and bivariate correlations were computed for study variables in IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21. Mediation analyses were conducted in Mplus 7 software (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2012) using the bootstrapping (resampling) procedure, a method developed to assess multiple mediator effects simultaneously (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). To quantify effect size, we report the completely standardized indirect effects (Preacher & Kelley, Reference Preacher and Kelley2011). These standardized coefficients (β) for the indirect effects indicate how much the dependent variable would be expected to change for a single standard deviation change in the predictor variable, and are therefore expressed on the metric of standard deviations.

Results

Rodent

Resource scarcity impairs parenting

Using our rodent model of scarcity-adversity, we first demonstrated that resource conditions experienced by rodent mothers and their pups directly influence maternal interactions with pups. Rodent mothers randomly assigned to the scarcity-adversity environment showed a significant decrease in time spent displaying sensitive caregiving behaviors toward their pups (Figure 1b). This included a significant decrease in time the mothers spent in the nest, t (19) = 2.253, p = .0362, decreased time that all pups spent huddled together in the home cage, t (19) = 3.045, p = .0073, and decreased time the mothers spent nursing pups, t (19) = 4.721, p = .0001, relative to mothers in control conditions. Despite decreased time spent nursing, pups gained weight normally as indicated by no significant group difference in weights measured at PN14 (control M ± SEM: 28.790 g ± 0.846; scarcity-adversity M ± SEM: 29.220 g ± 0.679), t (19) = 0.397, p = .6940. No significant group difference was found in time spent by the mothers grooming their pups, t (19) = 0.569, p = .5761.

In addition, in the scarcity-adversity conditions, mothers spent increased time displaying negative caregiving behaviors toward their pups (Figure 1c). This included increased time spent roughly transporting their pups (Figure 1a), t (19) = 2.406, p = .0317, and stepping on pups (Figure 1a), t (19) = 8.496, p < .0001. Furthermore, mothers in scarcity-adversity conditions showed a significant increase in time spent grooming themselves, t (19) = 2.607, p = .0178. Finally, pups in scarcity-adversity conditions spent a significantly higher amount of time scattered throughout the home cage, relative to pups in control conditions, t (19) = 3.357, p = .0035.

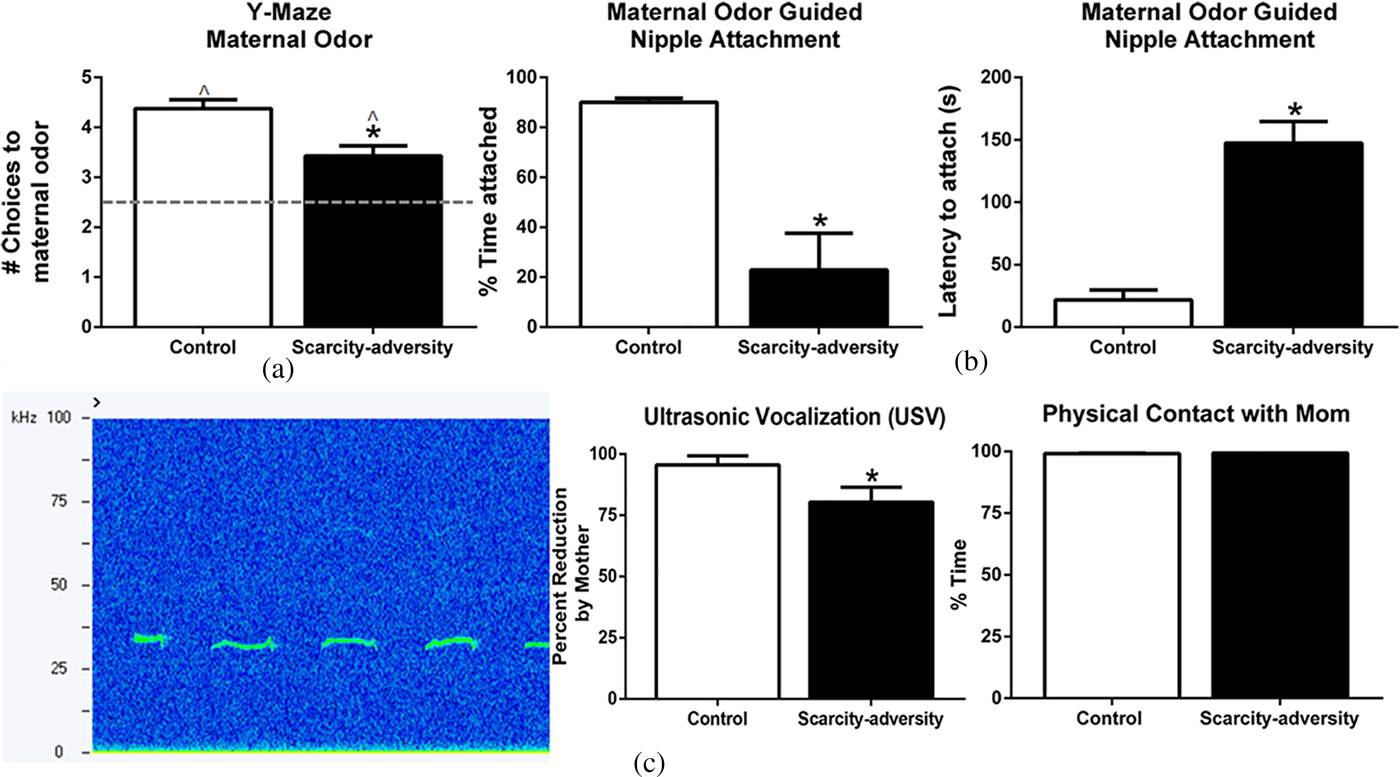

Scarcity-adversity rearing impairs maternal regulation of infant behavior

Next we demonstrated that scarcity-adversity rearing negatively impacts the effect of maternal odor on pup behavior (Figure 2). Pups reared in the scarcity-adversity condition were significantly less likely to approach maternal odor relative to a control odor in a Y-maze odor choice test (Figure 2a), t (14) = 3.480, p = .0041. However, both control and scarcity-adversity reared pups displayed a preference to maternal odor, as indicated by choices toward the odor at levels significantly greater than chance, control: t (7) = 10.250, p < .0001; scarcity-adversity: t (7) = 4.596, p = .0037. Furthermore, in a maternal odor-guided nipple attachment test, pups reared in scarcity-adversity conditions showed a significant decrease in time spent nipple attached to an anesthetized mother, t (14) = 4.522, p = .0007, and a significant increase in the latency to attach to a nipple, relative to control reared pups (Figure 2b), t (14) = 7.281, p < .0001. Finally, scarcity-adversity exposure significantly impacted the mother's ability to reduce infant distress USV emissions (30–60 kHz) following a brief period of social isolation (Figure 2c; Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley, Norman and Berntson2011; Hofer, Reference Hofer1996; Insel et al., Reference Insel, Hill and Mayor1986; Shair, Reference Shair2007). Specifically, following a brief period of social isolation, presentation of an anesthetized mother almost completely reduced USV emissions in control-reared pups, but led to a significantly decreased reduction of USV emissions in scarcity-adversity reared pups, t (10) = 2.112, p = .0304. When in the presence of an anesthetized mother, all pups remained in physical contact with the mother throughout the duration of USV recordings (SEM = 0). Together, these findings display impaired maternal regulation of infant behavior from scarcity-adversity rearing. When infant behaviors were analyzed with sex as a variable, no significant sex differences were found.

Figure 2. Scarcity-adversity rearing reduced maternal regulation of infant behavior. (a) Maternal odor regulates infant proximity to the caregiver to guide attachment formation via odor-preference learning. Following scarcity-adversity rearing, pups showed a significant decrease in choices toward the maternal odor in a Y-maze test (n = 8/group, *p < .05). However, both control and scarcity-adversity reared pups displayed a preference to maternal odor, as indicated by choices toward the odor at levels significantly greater than chance (*p < .05). (b) Infant rat pups require maternal odor to nipple attach to the mother. Pups reared in scarcity-adversity conditions showed a significant decrease in the percent of time spent attached to the nipple of an anesthetized mother during a nipple attachment test. Furthermore, scarcity-adversity reared pups showed a significant increase in the latency to attach to a nipple during the nipple attachment test (n = 8/group, *p < .05). (c) Maternal presence regulates infant reactivity in times of distress. Infant rat pups emit ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs; 30–60 kHz) when socially isolated, as indicated by the representative spectrogram on the left. Following social isolation, presenting control pups with an anesthetized dam led to almost a complete reduction of USVs. Presenting scarcity-adversity reared pups with an anesthetized dam led to a significantly decreased reduction in USVs, relative to control pups (middle, n = 6/group, *p < .05). In both rearing conditions, pups remained in physical contact with the anesthetized dam during the entire duration of the USV recording (right).

Scarcity-adversity rearing alters infant brain processing of maternal cues

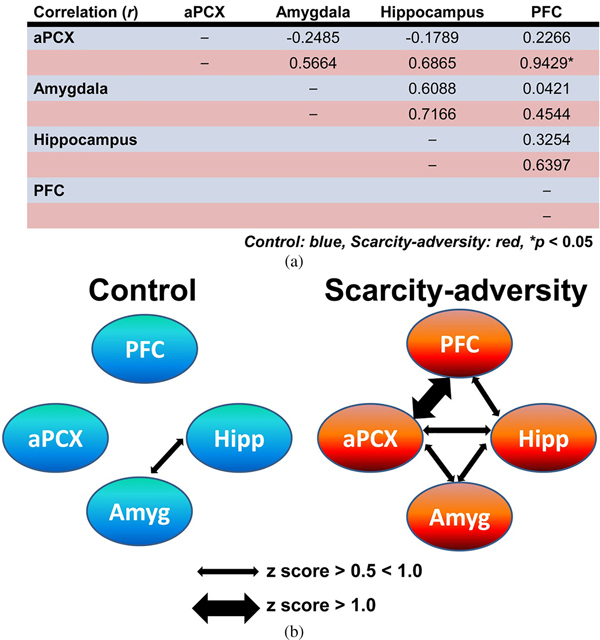

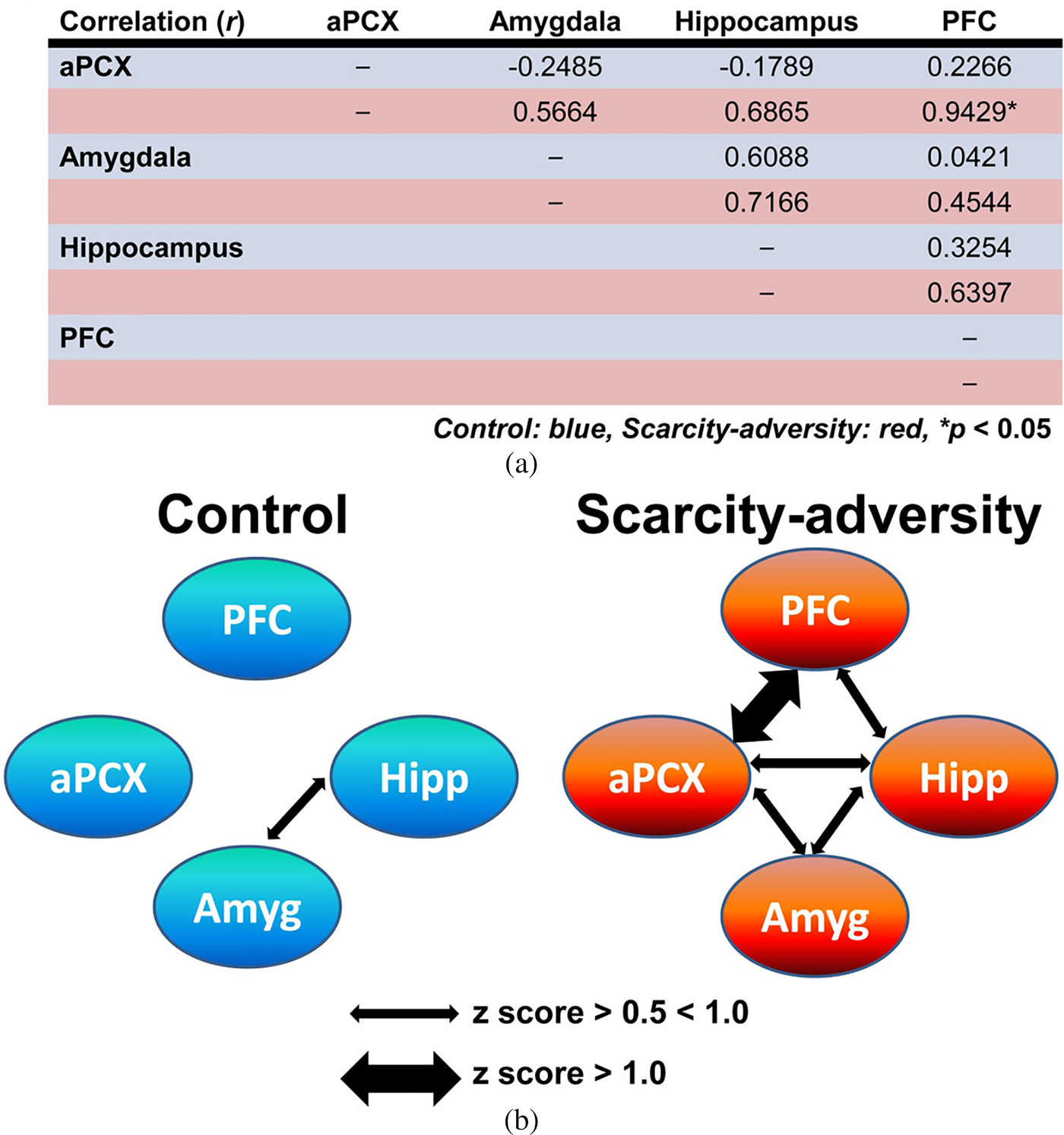

Finally, we demonstrated that rearing in the scarcity-adversity condition altered the processing of maternal odor in the infant's brain. Relative 2-DG uptake measures across individual animals were used to compute Pearson correlation coefficients (r) for all pairwise combinations of brain ROIs in response to maternal odor (Figure 3a). Pearson correlation coefficients were then transformed to Fisher z values to allow for the determination of the significance of difference between the correlation coefficients between groups (Figure 3a), and visual depiction of functional connectivity within each group (Figure 3b). Z scores indicated greater network activity in scarcity-adversity reared pups in response to maternal odor presentations. Overall, more instances of significant functional connectivity between the aPCX, hippocampus, amygdala, and PFC were observed in the scarcity-adversity group (z score > 0.5). Specifically, statistical analyses revealed a significant increase in functional connectivity between the aPCX and PFC in scarcity-reared pups, relative to control reared pups (z observed = –2.290, p = .022). No significant group differences were found for aPCX–amygdala (z observed = –1.340, p = .1802), aPCX–hippocampus (z observed = 1.520, p = .1285), amygdala–hippocampus (z observed = –0.290, p = .7718), amygdala–PFC (z observed = –0.67, p = .5029), or hippocampus–PFC (z observed = –0.630, p = .5287) modules of network activity. No significant sex differences were found when 2-DG responses to maternal odor were analyzed with sex as an analysis variable.

Figure 3. Scarcity-adversity rearing increases olfactory–limbic network functional connectivity in response to maternal odor. (a) Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were calculated from relative 2-deoxyglucose uptake in brain regions of interest and displayed here in blue rows for control reared animals and red rows for scarcity-adversity reared animals. Scarcity-adversity reared pups showed overall greater functional connectivity, with a significant increase in functional connectivity between the anterior piriform cortex and prefrontal cortex, relative to control reared pups (n = 7–8/group, *denotes significant difference between groups, p < .05). (b) Within each rearing condition, functional connectivity between the anterior piriform cortex, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala are visually depicted here, based on z score values calculated from r. Normally weighted arrows indicate a z score value between 0.5 and 1.0. Bolded arrows indicate stronger functional connectivity between brain regions, with a z score greater than 1.0.

Human

In order to assess translational validity of our rodent model of scarcity-adversity, we considered our rodent results in relation to a longitudinal study of human children and families followed from birth in predominantly low-income and nonurban communities in the United States (Vernon-Feagans & Cox, Reference Vernon-Feagans and Cox2013).

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Descriptive statistics for demographic variables and analysis variables from the human longitudinal data are presented in Table 2. Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 3. Poverty-related scarcity-adversity exposure at 6 months was significantly related to parenting quality at 15 months, such that higher scarcity-adversity exposure was associated with decreased sensitive caregiving (r = –.50, p < .01), and increased negative caregiving (r = .32, p < .01). Furthermore, poverty-related scarcity-adversity at 6 months was significantly associated with infant positive affect during the parent–infant interaction, as well as measures of infant mental development and attention, such that greater adversity was associated with decreased positive affect (r = –.13, p < .01), decreased mental development (r = –.24, p < .01), and decreased attention (r = –.07, p < .05). Parenting quality was also associated with infant affect, mental development, and attention. Specifically, sensitive parenting positively correlated with infant positive affect (r = .31, p < .01), mental development (r = .25, p < .01), and attention (r = .12, p < .01). Conversely, negative parenting positively correlated with infant negative affect (r = .29, p < .01), and was associated with lower scores on measures of mental development in infancy (r = .19, p < .01). Together, this pattern of statistically significant pathways lent support to a mediating model of scarcity-adversity for infant outcomes, which is empirically tested below.

Table 2. Demographics and descriptive statistics for all study variables

Table 3. Correlations among analysis variables

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Mediation

Infant affect

Next, we tested the hypothesis that parenting quality mediates the association between poverty-related scarcity-adversity and infant affect in the presence of the primary caregiver. Specifically, two potential aspects of parenting at 15 months (sensitive parenting and negative parenting) were assessed as potential mediators of the association between scarcity-adversity at 6 months and infant positive and negative affect at 15 months (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Multiple mediation model exploring mediation of parenting quality on infant affect. The statistically significant directional paths are depicted here (bolded) with standardized coefficients (β). Sensitive parenting mediates the predictive role of early life scarcity-adversity exposure for infant positive affect, while negative parenting mediates the predictive role of early life scarcity-adversity exposure for infant negative affect. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .0001.

After controlling for our covariates (state of residence, race, infant sex and age, and caregiver age), we found that the association between scarcity-adversity and infant affect was statistically mediated by parenting quality, with sensitive parenting mediating the predictive role of scarcity-adversity for positive infant affect (β = –0.14, p < .0001) and negative parenting mediating the predictive role of scarcity-adversity for negative child affect (β = 0.08, p < .0001). These indirect pathways are also listed in Table 4. The model is depicted (without covariates) in Figure 4.

Table 4. Mediation analysis: Direct and indirect effects of poverty-related scarcity-adversity on infant affect in caregiver's presence

Note: B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error; β = standardized coefficient; SA = scarcity-adversity; *p < 0.01; **p < 0.0001.

Mental development and attention

To further examine the potential mediation of scarcity-adversity on infant development through parenting quality, we next examined measures of infant cognitive ability at age 15 months, specifically the MDI of the Bayley Scales and an observational rating of infant attentiveness during the approximately 2-hr data collection period at 15 months. Findings are presented in Table 5 and indicate that the association between scarcity-adversity exposure and child attention was also statistically mediated by parenting quality. Sensitive parenting served as a significant mediator for the role of scarcity-adversity in predicting infant attention (β = –0.05, p < .0001) and mental development (β = –0.05, p < .0001), while negative parenting mediated the predictive role of scarcity-adversity for infant mental development (β = –0.02, p < .05). The model is depicted (without covariates) in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Multiple mediation model exploring mediation of parenting quality on early life measures of cognitive abilities. The statistically significant directional paths are depicted here (bolded) with standardized coefficients (β). Sensitive parenting mediates the predictive role of early life scarcity-adversity exposure for infant attention and mental development, while negative parenting mediates the predictive role of early life scarcity-adversity exposure for infant mental development. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .0001.

Table 5. Mediation analysis: Direct and indirect effects of poverty-related scarcity-adversity on infant cognitive abilities

Note: B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error; β = standardized coefficient; SA = scarcity-adversity; *p < 0.01; **p < 0.0001.

Alternative models

In addition to testing the hypothesized model described above, in which the predictive role of scarcity-adversity for infant affect was mediated by parenting quality, we also evaluated an alternative model in which the pathways were reversed (i.e., the role of scarcity-adversity on parenting quality would be mediated by infant affect). Our results yielded some support for this alternative model, with significant direct effects of scarcity-adversity on sensitive parenting (β = –0.36, SE = 0.04, p < .0001) and negative parenting (β = 0.24, SE = 0.04, p < .0001), as well as a statistically significant mediating predictive role of infant positive affect for sensitive parenting (β = –0.03, SE = 0.009, p = .005). We next evaluated an alternative model in which scarcity-adversity exposure on parenting quality would be mediated by child cognitive abilities. Our results provided some support for this alternative model, with significant direct effects of scarcity-adversity on sensitive parenting (β = –0.36, SE = 0.04, p < .0001) and negative parenting (β = 0.22, SE = 0.04, p < .0001), as well as a statistically significant mediating predictive role of infant mental development for sensitive parenting (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = .011), and infant mental development for negative parenting (β = 0.01, SE = 0.01, p = .021).

Discussion

Children raised in poverty are at increased risk for a host of negative physical and mental health outcomes (Blair & Raver, Reference Blair and Raver2012, Reference Blair and Raver2016; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Ziol-Guest and Kalil2010; Hackman et al., Reference Hackman, Farah and Meaney2010; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Riis and Noble2016; Yoshikawa et al., Reference Yoshikawa, Aber and Beardslee2012). However, specific mechanisms by which this occurs remain unclear, and understanding them is of critical public health importance. Over the past decades, a growing number of studies on children have identified parenting quality as one likely mechanism through which poverty affects child development (Blair & Raver, Reference Blair and Raver2012; Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, Reference Brooks-Gunn and Duncan1997; McLoyd, Reference McLoyd1998; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Blair and Sullivan2017). In addition, recent evidence has suggested that parenting quality is at least one mediator of poverty on child brain as well as behavioral development in humans (Granero, Louwaars, & Ezpeleta, Reference Granero, Louwaars and Ezpeleta2015; Hackman, Gallop, Evans, & Farah, Reference Hackman, Gallop, Evans and Farah2015; Holochwost et al., Reference Holochwost, Gariépy, Propper, Gardner-Neblett, Volpe, Neblett and Mills-Koonce2016; Luby et al., Reference Luby, Belden, Botteron, Marrus, Harms, Babb and Barch2013). As noted above, however, research on the effect of poverty on child development is necessarily correlational. While human research provides valuable insight into relationships among poverty, parenting, and child development, one limitation is that most studies cannot control the selection process into poverty, and thus are potentially confounded by the host of factors that covary with poverty status and are potential “third variable” explanations for observed associations among poverty, parenting, and child outcomes. Thus, in order to allow for more strongly controlled experiments and the study of causal mechanisms related to poverty, parenting, and neurobehavioral development, the present study assessed the appropriateness of modeling domain-specific aspects of poverty through the use of a rodent model.

Operationalizing the impact of poverty on development: Threat versus deprivation

Operationalizing poverty in a way that allows for controlled experiments (e.g., via animal models) is challenging given the variety of poverty-related risks ranging from psychosocial to ecological factors (Evans, Reference Evans2004). Thus, as a first approach to modeling poverty using a rodent model, the current study took a domain-specific approach by manipulating only one poverty-related factor: resource levels. This procedure has high face validity in that rodent mothers randomly assigned to the treatment condition were provided with limited quantities of an essential parenting resource, namely, wood shavings with which to build the nest. Mothers in the control condition were similar in all respects other than the amount of material available to build a proper nest. Resource-depleted mothers were less sensitive in the care that they provided to their offspring as demonstrated by a number of well-established indicators of caregiving competence, including time spent with pups in the nest and nursing, as well as pup transport, rough handling, and placement within the home cage (for review, see Drury et al., Reference Drury, Sanchez and Gonzalez2016). These results mirror the present study's human findings. Specifically, scarcity-adversity as indicated by cumulative scarcity-related risk indicators was inversely correlated with sensitive parenting, positively correlated with negative parenting, and parenting fully mediated the association of poverty-related risk with infant affect and cognitive abilities. While parenting is only one potential pathway of many by which poverty can influence child development (Evans, Reference Evans2004), the current findings support the idea that altered parenting is at least one point of commonality for cross-species mammalian research. Thus, future rodent research with our scarcity-adversity rodent model may be leveraged for discovering specific mechanisms by which poverty influences development via altered parenting quality.

Our rodent model impacted caregiving behaviors by exposing scarcity-adversity reared pups to increased maternal neglect (i.e., decreased time spent in nest, with pups, and nursing) as well as increased threat from the mother (i.e., increased rough transport and stepping on pups). This finding is in agreement with growing evidence from human research studies indicating that poverty shapes neurodevelopment by depriving the brain of vital input (e.g., maternal neglect, decreased cognitive stimulation, and compromised nutrition), while increasing its exposure to negative input (e.g., heightened stress, environmental toxins, and adverse parenting behaviors; for reviews, see Blair & Raver, Reference Blair and Raver2016; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Riis and Noble2016). Together, these findings are of particular interest due to current efforts to study early life adversity along core dimensions of deprivation (the absence of expected positive input) versus threat (the presence of aversive input), which are argued to have distinct influences on neural development (McLaughlin & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan2016; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014; Sheridan & McLaughlin, Reference Sheridan and McLaughlin2014). This orthogonalization is important for discerning distinct mechanisms by which threat versus deprivation influences neurobehavioral development. However, our findings suggest that animal models that study the interaction of deprivation and threat may be the most optimal for informing mechanisms by which poverty-related adversity affects development.

The foregoing stands in contrast to models of early life adversity that prevailingly conceptualize adverse childhood experiences within a stress perspective focused on either deprivation or threat (Brett, Humphreys, Fleming, Kraemer, & Drury, Reference Brett, Humphreys, Fleming, Kraemer and Drury2015; Howell et al., Reference Howell, McMurray, Guzman, Nair, Shi, McCormack and Sanchez2017; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014; Szyf, Weaver, & Meaney, Reference Szyf, Weaver and Meaney2007). Other laboratories are even using a rodent model of resource depletion similar to the one used for the present study, for the purpose of studying early life stress or abuse (i.e., threat; Blaze, Asok, & Roth, Reference Blaze, Asok and Roth2015; Molet et al., Reference Molet, Heins, Zhuo, Mei, Regev, Baram and Stern2016; Molet, Maras, Avishai-Eliner, & Baram, Reference Molet, Maras, Avishai-Eliner and Baram2014). However, these models have not been leveraged for informing poverty-related research. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to integrate an animal model alongside human developmental research related to poverty, in order to maximize translational validity of the animal model and allow for multiple levels of analyses. By leveraging the ecological validity of our rodent model, continued research may determine mechanisms by which the interaction of deprivation and threat shape infant neurobehavioral development.

Scarcity-adversity and developmental competence

A major goal of this study was to explore cross-species developmental impacts as a result of scarcity-adversity in very early life, a vulnerable period due to heightened and rapid brain development (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Blair and Sullivan2017). In order to assess infant outcomes related to social–emotional and cognitive developmental competence, we chose well-established species-specific indicators. For rodent pups, such indicators encompassed pup responses to maternal olfactory and somatosensory stimuli as measures of healthy, typical development. Rodent pups rely on chemosensory and somatosensory systems for survival in early life, as infant auditory and visual systems only begin to emerge around PN15 (Ehret, Reference Ehret1976; Weber & Olsson, Reference Weber and Olsson2008). For example, maternal odor and somatosensory cues regulate mother–infant social behavior, nipple attachment, infant USVs in the presence of threat, and infant amygdala activity to permit maternal social buffering of pups' stress hormones (Al Aïn et al., Reference Al Aïn, Perry, Nunez, Kayser, Hochman, Brehman and Sullivan2016; Hill & Almli, Reference Hill and Almli1981; Hofer et al., Reference Hofer, Shair and Singh1976; Hostinar, Sullivan, & Gunnar, Reference Hostinar, Sullivan and Gunnar2014; Moriceau & Sullivan, Reference Moriceau and Sullivan2006; Oswalt & Wilson, Reference Oswalt and Wilson1979; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016; Raineki, Pickenhagen, et al., Reference Raineki, Pickenhagen, Roth, Babstock, McLean, Harley and Sullivan2010; Singh & Tobach, Reference Singh and Tobach1975; Takahashi, Reference Takahashi1992; Teicher & Blass, Reference Teicher and Blass1977).

In the present study, scarcity-adversity rearing produced profound neurobehavioral impacts on the developing infant rat pup's response to maternal olfactory and somatosensory stimuli. We interpret these effects as indicative of the extent to which maternal caregiving behaviors function to regulate and foster ongoing behavior and development. This view is consistent with Hofer's (Reference Hofer1994) concept that maternal sensory cues function as “hidden regulators of development.” For example, within this framework, maternal tactile stimulation regulates levels of growth hormone, and warmth from the mother regulates overall activity levels. Maternal odor is a particularly powerful regulator for pups; it evokes approach to the mother and permits nipple attachment, which is needed for pup survival (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016). It is important to note that maternal odor-guided behaviors are dependent on pups first learning about the maternal odor, which occurs via their exposure and experiences with the maternal odor (beginning in the womb; Logan et al., Reference Logan, Brunet, Webb, Cutforth, Ngai and Stowers2012; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016). That is, the infant rat pup's response to maternal odor is not innate. Young pups learn to approach maternal odor regardless of the quality of maternal care, presumably to ensure survival (Perry & Sullivan, Reference Perry and Sullivan2014). However, our present results demonstrate that scarcity-adversity exposure in early life impacts the strength of maternal odor's ability to regulate the pup's neurobehavioral responses. The failure of maternal cues to optimally regulate infant pup behavior has been shown to precede social–emotional and cognitive deficits throughout development, including into adulthood (Al Aïn et al., Reference Al Aïn, Perry, Nunez, Kayser, Hochman, Brehman and Sullivan2016; Perry & Sullivan, Reference Perry and Sullivan2014; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016; Raineki, Moriceau, et al., Reference Moriceau, Roth and Sullivan2010; Raineki et al., Reference Raineki, Sarro, Rincón-Cortés, Perry, Boggs, Holman and Sullivan2015; Rincón-Cortés & Sullivan, Reference Rincón-Cortés and Sullivan2014; Sullivan & Perry, Reference Sullivan and Perry2015; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Bath, Joels, Korosi, Larauche, Lucassen and Baram2017). Furthermore, across species, maternal regulation of infant behavior and physiology has been proposed as vital to the early life programming of brain areas underlying life-long emotionality and developmental competence, although the neural mechanisms by which this occurs remain to be elucidated (for reviews, see Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Telzer, Humphreys, Goff, Shapiro and Tottenham2014; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015).

Our rodent research findings are similar to the present study's human findings demonstrating that scarcity-adversity is associated with altered early life indicators of social–emotional and cognitive competence, namely, infant affect during a mother–infant interaction test and indices of infant attention and mental development. However, our rodent findings extend these human findings by providing experimental evidence that random assignment into scarcity-adversity conditions produces alterations in indicators of developmental competence as early as in infancy. Finally, the comparable nature of these cross-species findings provides ecological support for the use of our rodent model for studying developmental aspects of poverty-related adversity exposure. Thus, our rodent model may be further leveraged to study potentially translationally relevant neurobehavioral mechanisms by which scarcity-adversity influences development.

Exploring neural phenotypes of scarcity-adversity

Finally, in search of candidate neural mechanisms by which scarcity-adversity may impact key brain areas related to later life social–emotional and cognitive abilities, we assessed the effects of scarcity-adversity on infant brain activity in response to the primary regulatory cue of infant rat pup behavior: maternal odor. Using a measure of glucose uptake into brain cells (14C 2-DG), which is an indicator of neural activity, we found scarcity-adversity-induced functional connectivity differences between brain ROIs in young pups in response to presentations of maternal odor. These regions of interest included brain areas previously identified in the human literature as impacted by early life adversity, including the PFC and amygdala (for reviews, see Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Telzer, Humphreys, Goff, Shapiro and Tottenham2014; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015). Functional connectivity is a sensitive indicator in both rodents and humans of circuit function, and disruptions (increases or decreases) of functional connectivity are associated with an increased risk for a variety of pathologies during development (Di Martino et al., Reference Di Martino, Zuo, Kelly, Grzadzinski, Mennes, Schvarcz and Milham2013; Scheinost et al., Reference Scheinost, Sinha, Cross, Kwon, Sze, Constable and Ment2017; Sheffield & Barch, Reference Sheffield and Barch2016; Wilson, Peterson, Basavaraj, & Saito, Reference Wilson, Peterson, Basavaraj and Saito2011; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Rincón-Cortés, Raineki, Sarro, Colcombe, Guilfoyle and Castellanos2017).

Here we found enhanced functional connectivity within the olfactory–limbic network, with a greater number of significantly connected brain areas in the scarcity-adversity group. Specifically, functional connectivity between the cortical region for odor processing (aPCX) and the PFC was statistically significantly greater in the scarcity-adversity group than in the control group. The aPCX is critical for supporting mother–infant interactions and keeping pups within the nest, via an olfactory bulb/aPCX-dependent circuit that supports strong odor preference learning (Landers & Sullivan, Reference Landers and Sullivan2012; Moriceau, Roth, & Sullivan, Reference Moriceau, Roth and Sullivan2010; Moriceau & Sullivan, Reference Moriceau and Sullivan2004; Morrison, Fontaine, Harley, & Yuan, Reference Morrison, Fontaine, Harley and Yuan2013). The PFC, which has been implicated in executive function and emotion regulation processes, shows protracted development continuing through adolescence (Hackman & Farah, Reference Hackman and Farah2009). Thus, it is unclear if the PFC is functionally developed and contributing to rat behavior at this young age (Andersen, Lyss, Dumont, & Teicher, Reference Andersen, Lyss, Dumont and Teicher1999; Andersen, LeBlanc, & Lyss, Reference Andersen, LeBlanc and Lyss2001; Bertolino et al., Reference Bertolino, Saunders, Mattay, Bachevalier, Frank and Weinberger1997; Cunningham, Bhattacharyya, & Benes, Reference Cunningham, Bhattacharyya and Benes2002; Seminowicz et al., Reference Seminowicz, Mayberg, McIntosh, Goldapple, Kennedy, Segal and Rafi-Tari2004; Sripanidkulchai, Sripanidkulchai, & Wyss, Reference Sripanidkulchai, Sripanidkulchai and Wyss2004; Sturrock, Reference Sturrock1978; Zhang, Reference Zhang2004). Taken together, our findings suggest that the basic olfactory network that is important for maternal odor responses in infant pups has altered functional interactions with a brain area important for cognitive and emotional regulation across species (Landers & Sullivan, Reference Landers and Sullivan2012; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015).

Because data were collected only following maternal odor presentations, it is not possible to discern if the pattern of altered functional connectivity between aPCX and PFC observed in scarcity-adversity reared pups is specific to differences in processing maternal odor or differences in overall brain development and function. However, a recent study explored systems-level brain activation to odors of varying hedonic values (e.g., appetitive and aversive) relative to “no odor” control conditions across early development (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016). Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Al Aïn, Raineki, Sullivan and Wilson2016) found evidence that while aPCX activity is similarly elevated in response to both appetitive (i.e., maternal odor) and aversive odor (i.e., predator odor) stimuli relative to no odor controls, it is the functional connectivity between olfactory cortex (e.g., aPCX) and limbic/cortical brain regions (e.g., PFC, hippocampus, and amygdala) that varies as a function of an odor's hedonic value. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the assignment of a hedonic value to an odor stimulus is highly plastic in early life, and is based on the pup's prior experiences with the odor. For example, altering the smell of rat mothers' natural odor via manipulation of their diet led to a devaluation of the natural maternal odor as assessed by behavioral indicators of odor preference as well as corresponding changes in olfactory cortex–limbic/cortical brain functional connectivity, following 2 weeks of rearing with these “newly scented” mothers. Therefore, one possible interpretation of the present study's findings is that the altered functional connectivity between aPCX and limbic/cortical brain regions reflects a change in the hedonic value of maternal odor as a function of scarcity-adversity rearing, such that the odor becomes less appetitive, perhaps due to the pairing of maternal odor with negative caregiver–infant interactions in scarcity-adversity rearing conditions. While scarcity-adversity reared pups still displayed a preference for maternal odor in the Y-maze test, they showed a significant reduction in approach to maternal odor relative to control reared pups, indicative of a reduced preference for maternal odor following scarcity-adversity rearing.

It should be noted, however, that these functional connectivity changes may also be reflective of overall differences in brain function following scarcity-adversity rearing, rather than being specific to maternal odor presentations. There has been extensive work on early life experience and brain programming, which indicates that early life adversity, and even prenatal adversity (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Cha, Roy, Peterson, Bansal, Gustafsson and Monk2016), alters the developmental trajectory of limbic areas such as the PFC and amygdala (for review, see Callaghan et al., Reference Callaghan, Sullivan, Howell and Tottenham2014). For example, a pattern of functional connectivity that is similar to the present findings was found in previously institutionalized youth who had faced caregiver adversity (Silvers et al., Reference Silvers, Lumian, Gabard-Durnam, Gee, Goff, Fareri and Tottenham2016). Specifically, previously institutionalized youth displayed significantly increased prefrontal–amygdala/hippocampal functional connectivity during an aversive learning task involving non-odor stimuli. Furthermore, increased prefrontal–amygdala/hippocampal functional connectivity was associated with resilience against anxiety, suggesting that these neural changes may provide some adaptive advantages (Silvers et al., Reference Silvers, Lumian, Gabard-Durnam, Gee, Goff, Fareri and Tottenham2016). However, findings regarding the adaptive nature of adversity-induced changes in corticolimbic structure and activity have been mixed. For example, poverty-related changes in the PFC have been associated with difficulties in executive functions, such as planning, attentional control, and impulse control following exposure to early life adversity (Hackman & Farah, Reference Hackman and Farah2009). Understanding the causal role of adversity-induced PFC alterations, particularly as it relates to the emergence of psychopathologies versus resilience, should be the focus of future mechanistic research.

Together, we suggest that the neural phenotype observed in our rodent model of scarcity-adversity is likely reflective of differences in the learned value of the maternal odor, combined with overall differences in the brain's developmental trajectory.

Limitations and future directions