Psychosocial adjustment in adulthood has been associated with a multitude of childhood risk factors (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2005; Farrington, Reference Farrington1995; Raudino, Fergusson, & Horwood, Reference Raudino, Fergusson and Horwood2013). Prior research has focused on the impact of single indicators of risk to identify specific areas for intervention, whereas more recent efforts have been undertaken to examine the impact of exposure to an accumulation of risk factors. This focus on examining the impact of quantity of risk is rooted in Rutter's (Reference Rutter, Kent and Rolf1979) accumulation of risk model, in which he posited that it may not be any particular risk, but instead the number of risk factors to which a child is exposed that leads to maladaptive outcomes. Research examining the effects of exposure to cumulative risk in childhood has incorporated a wide variety of risk factors and has found significant association between the number of childhood risk factors and mental and physical health outcomes across the life span (e.g., Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards1998). The present study adds to this increasing body of literature by examining the impact of cumulative childhood environmental risk on psychosocial adjustment in adulthood, as well as by examining the role of child abuse and/or neglect in this relationship.

Previous Research on Cumulative Risk

The majority of studies addressing the accumulation of risk model have operationalized cumulative risk through the creation of an index: the summation of the number of risk factors, often across multiple ecological levels. By creating such an index, these studies have examined the nature of the relationship between the number of risk factors to which an individual is exposed in childhood and a variety of behavioral, psychosocial, and health-related outcomes across the life span. Prior studies have focused primarily on Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, and Baldwin's (Reference Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin and Baldwin1993) additive model, in which a linear change in outcome is proposed: the higher one's cumulative risk score, the more likely he or she is to demonstrate maladaptive outcomes. A number of studies, however, have attempted to compare this additive model with a nonlinear model suggesting a threshold effect. This model postulates one of two effects: that there is little difference in outcomes before a certain cumulative risk score is reached, but after this threshold, there is a significant increase in maladaptive outcomes, indicating a quadratic relationship (Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulman, & Sroufe, Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe2005; Rutter, Reference Rutter, Kent and Rolf1979); or that there is a threshold beyond which there is a plateau, or leveling off, for the outcome in question (Morales & Guerra, Reference Morales and Guerra2006).

The rationale behind examining the influence of cumulative risk through this indexing method, as opposed to using models that keep risk factors as individual variables within models, is multifaceted. First, the creation of a cumulative risk index means that one is able to capture the natural covariation of many of these individual-, family-, and neighborhood-level risk factors (Flouri, Tzavidis, & Kallis, Reference Flouri, Tzavidis and Kallis2010; Raviv, Taussig, Culhane, & Garrido, Reference Raviv, Taussig, Culhane and Garrido2010). Second, previous studies examining the influence of childhood risk on maladaptive outcomes demonstrate findings that fit a developmental model characterized by equifinality; these outcomes are often multiply determined and cannot be explained by any single risk factor (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1996; Sameroff, Bartko, Baldwin, Baldwin, & Seifer, Reference Sameroff, Bartko, Baldwin, Baldwin, Seifer, Lewis and Feiring1998). Third, from a methodological standpoint, as an aggregate variable, an index is more stable than any individual measure and allows for increased power to detect effects, as errors of measurement decrease as the individual risk factors are summed and degrees of freedom are preserved (Flouri et al., Reference Flouri, Tzavidis and Kallis2010). The creation of an index of cumulative risk, therefore, allows for an examination of Rutter's (Reference Rutter, Kent and Rolf1979) theory that instead of any one particular risk factor leading to these maladaptive outcomes, it is the number of risk factors to which a child is exposed that accounts for the most variance and is most important in determining outcomes for the child.

Previous studies incorporating a cumulative risk index made up of individual-, family-, and neighborhood-level factors have focused on the impact of risk exposure on various domains of functioning across the life span. However, this literature documents the unresolved issue of whether the relationship between cumulative risk and maladaptive outcomes is best described as linear or nonlinear. Cross-sectional studies have identified linear relationships between childhood cumulative risk and concurrent internalizing and externalizing disorders (e.g., Atzaba-Poria, Pike, & Deater-Deckard, Reference Atzaba-Poria, Pike and Deater-Deckard2004; Gerard & Beuhler, Reference Gerard and Buehler2004), psychiatric disorders (e.g., Raviv et al., Reference Raviv, Taussig, Culhane and Garrido2010; Rutter, Reference Rutter, Kent and Rolf1979), academic problems (e.g., Forehand, Biggar, & Kotchick, Reference Forehand, Biggar and Kotchick1998), and distress symptoms (e.g., psychophysiological stress, delayed gratification, and perceptions of self-worth; Evans & English, Reference Evans and English2002; Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2012). Longitudinal studies have identified linear relationships between childhood cumulative risk and adolescent outcomes including internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Appleyard et al., Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe2005), academic problems (e.g., Forehand et al., Reference Forehand, Biggar and Kotchick1998; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2000), and academic performance and self-competence (Sameroff et al., Reference Sameroff, Bartko, Baldwin, Baldwin, Seifer, Lewis and Feiring1998).

Other studies have tested a threshold effect for the relationship between childhood cumulative risk and maladaptive outcomes. Rutter (Reference Rutter, Kent and Rolf1979) and Jones, Forehand, Brody, and Armistead (Reference Jones, Forehand, Brody and Armistead2002) found an increased risk of mental disorders for children exposed to more than three risk factors, while other studies have found that risk increases significantly after exposure to more than two risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Biederman et al., Reference Biederman, Milberger, Faraone, Kiely, Guite and Mick1995) and clinical diagnoses (i.e., oppositional defiant disorder and attention deficit disorder; Greenberg, Speltz, DeKlyen, & Jones, Reference Greenberg, Speltz, DeKlyen and Jones2001). Morales and Guerra (Reference Morales and Guerra2006) identified a saturation effect for concurrent and longitudinal academic achievement, depression, and aggression among children exposed to more than three risk factors. In addition to testing a linear model to examine the impact of cumulative risk on adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems, Appleyard et al. (Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe2005) tested a threshold effect, but they did not find support for this nonlinear model.

To our knowledge, only one previous study has examined the relationship between childhood cumulative risk and maladaptive outcomes in adulthood. Felitti et al.'s (Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards1998) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study has assessed the relationship between cumulative risk and numerous physical and mental health outcomes, including smoking, substance use, internalizing symptoms, attempted suicide, severe obesity, sleep disturbance, sexual concerns, intimate partner violence, and difficulty controlling anger (e.g., Dube, Anda, Felitti, Edwards, & Croft, Reference Dube, Anda, Felitti, Edwards and Croft2002; Dube et al., Reference Dube, Fairweather, Pearson, Felitti, Anda and Croft2009; Dube, Felitti, Dong, Giles, & Anda, Reference Dube, Felitti, Dong, Giles and Anda2003; Felitti, Reference Felitti2002; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards1998). However, there are a number of methodological limitations of this study that make its findings ambiguous. The ACE study relied on responses to surveys that solicited information about a limited number of childhood adversities and medical history from participants when they were approximately 55 to 57 years old. Thus, the ACE study is reliant on retrospective reports that are susceptible to recall bias, and the cross-sectional design makes it difficult to interpret the findings. Finkelhor et al. (Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2012) sought to improve the ACE study by measuring childhood risk at an earlier age and increasing the number and domains of risk factors included in the cumulative risk index, although this work is also cross-sectional in design, with data collected when children were between the ages of 10 and 17 years old. Nonetheless, Finkelhor et al. (Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2012) found that exposure to childhood cumulative risk was found to be linearly related to adolescent distress, operationalized by summing scores on indicators of anger, depression, anxiety, dissociation, and posttraumatic stress.

The Role of Child Maltreatment

Although extensive research has documented the relationship between childhood maltreatment and maladaptive outcomes across the life span (for a review, see Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009), no single pattern of outcome of maltreatment has been identified. Not all maltreated children demonstrate maladaptive outcomes either immediately or over the long term, and of those who do, their experiences are diverse and often complex (Masten & Wright, Reference Masten and Wright1998; Widom, Reference Widom1991). In addition, maltreatment often occurs in the context of other risk factors, across multiple ecological levels, complicating our understanding of the relationship between child abuse and/or neglect and maladaptive outcomes. Although some research has attempted to disentangle the consequences of maltreatment from the consequences of exposure to other forms of risk (Cicchetti, Rogosch, Lynch, & Holt, Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch, Lynch and Holt1993; Jouriles, Murphy, & O'Leary, Reference Jouriles, Murphy and O'Leary1989; Widom, Reference Widom1999), this has proven to be a difficult endeavor (Masten & Wright, Reference Masten and Wright1998). Studies have examined the influence of cumulative risk on maladaptive outcomes and have incorporated maltreatment into the cumulative risk indices (e.g., Appleyard et al., Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe2005; Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2012); however, this does not allow for an understanding of whether or not maltreated children demonstrate differential effects from exposure to cumulative risk in comparison to their nonmaltreated counterparts.

The present study adds to the literature by examining the specific role of childhood maltreatment in the relationship between cumulative risk and mental health, behavioral, and academic functioning in adulthood. To our knowledge, only one previous study has (partially) undertaken this endeavor. Raviv et al. (Reference Raviv, Taussig, Culhane and Garrido2010) conducted a study in which they examined the relationship between exposure to cumulative risk and mental health symptomology with a sample of youth who were court-ordered to out of home care due to substantiated maltreatment. Raviv et al. (Reference Raviv, Taussig, Culhane and Garrido2010) found there was a linear relationship between cumulative risk and youth reported anxiety, depression, anger, posttraumatic stress, sexual concerns, and dissociation, as well as parent-reported externalizing symptoms. While this study extended findings from studies with general samples of youth, the lack of a control group makes it impossible to directly compare these findings with findings for nonmaltreated youth. Given that maltreatment is a significant risk factor by itself for multiple outcomes, it is important to understand whether and how maltreatment impacts the nature of the relationship between cumulative risk and outcomes. Prior research has documented differences in psychosocial outcomes for maltreated and nonmaltreated children, including criminal behavior (e.g., Widom, Reference Widom1989a) and depressive symptomatology (e.g., Kaufman & Charney, Reference Kaufman and Charney2001). Given these findings, it is possible that child abuse and neglect may amplify the impact of exposure to cumulative risk on these outcomes. This could suggest an interaction where there may be a larger difference between abused and neglected children exposed to high and low risk compared to control group children in terms of their psychosocial functioning in adulthood.

An additional issue that needs to be considered is that previous literature examining the impact of childhood risk on adult academic, mental health, and behavioral outcomes has often identified significant differences by gender. For example, high school dropout rates are higher for males than for females (Sum & Harrington, Reference Sum and Harrington2003), and women are more likely to attain a college degree than men (Peter & Horn, Reference Peter and Horn2005). Research on internalizing and externalizing problems has been more inconsistent, with some studies identifying more symptoms of depression and anxiety in adulthood among females (e.g., Piccinelli & Wilkinson, Reference Piccinelli and Wilkinson2000) and more violence and criminal arrests in adulthood among males (e.g., Bennett, Farrington, & Huesmann, Reference Bennett, Farrington and Huesmann2005), but other studies finding few differences in internalizing and externalizing by gender (e.g., Forehand et al., Reference Forehand, Biggar and Kotchick1998). In addition, some studies have noted gender differences in responses to family stress (Beyers, Bates, Pettit, & Dodge, Reference Beyers, Bates, Pettit and Dodge2003; Gaylord, Kitzmann, & Lockwood, Reference Gaylord, Kitzmann. and Lockwood2003), suggesting that exposure to cumulative risk in childhood may differentially affect males and females. Given these findings, the present study included an analysis of potential gender differences in the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and academic, mental health, and behavioral outcomes in adulthood.

The Present Study

The present study attempts to build on previous research by testing a series of models to examine the nature of the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and adaptive functioning in adulthood. The longitudinal design allows for an examination of the relationship between childhood risk factors and three different domains of functioning in adulthood in a temporally correct sequence: educational attainment, mental health, and criminal behavior. We initially consider linear and quadratic models. The linear model examines whether there is a linear relationship between cumulative risk and the three outcomes (Figure 1a). The quadratic model examines whether two nonlinear effects exist: one that considers whether there is an accelerating effect, so that the addition of more risk factors at the higher end of a cumulative risk index has a bigger impact on psychosocial adjustment than addition of more risk factors at the lower end of the index (Figure 1b), and one that considers whether there is a saturation effect, that is, a tapering effect for the outcome with exposure to more risk factors (Figure 1c). Then, we examine the specific roles of child maltreatment and gender (in separate moderation analyses), considering whether either acts as a potential moderating factor in the relationship between cumulative risk and the three outcomes. Given the impact of child maltreatment on outcomes across the life span (e.g., Lansford et al., Reference Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, Bates, Crozier and Kaplow2002; Mullen, Martin, Anderson, Romans, & Herbison, Reference Mullen, Martin, Anderson, Romans and Herbison1996; Widom, Reference Widom1989b), child abuse and neglect is included as a risk factor within the cumulative risk index for all analyses except for the moderation analyses examining the interaction of child maltreatment with cumulative risk. We hypothesized that the impact of exposure to cumulative risk found in previous research through adolescence would continue into middle adulthood, affecting psychosocial outcomes across multiple domains, thus demonstrating the pervasive effects that negative childhood environments may have.

Figure 1. Theoretical figures demonstrating the impact of exposure to cumulative risk in childhood on psychosocial adjustment in adulthood with (a) a linear relationship between number of risk factors and maladaptive outcome; (b) a nonlinear relationship with an accelerating effect (Appleyard et al., Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe2005; Rutter, Reference Rutter, Kent and Rolf1979); and (c) a nonlinear relationship with a saturation effect (Morales & Guerra, Reference Morales and Guerra2006).

Method

Design

The research project upon which this proposal is based utilizes a cohort design (Leventhal, Reference Leventhal1982; Schulsinger, Mednick, & Knop, Reference Schulsinger, Mednick and Knop1981), in which abused and neglected children were matched with nonabused and nonneglected children, and followed prospectively into adulthood. Notable features of the design include (a) an unambiguous operationalization of child abuse and/or neglect; (b) a prospective design; (c) separate abused and neglected groups; (d) a large sample; (e) a comparison group matched as closely as possible on age, sex, race, and approximate social class background; and (f) assessment of the long-term consequences of abuse and/or neglect beyond adolescence and into adulthood (Widom, Reference Widom1989b).

The prospective nature of the study disentangles the effects of childhood victimization from other potential confounding effects. Because of the matching procedure, subjects are assumed to differ only in the risk factor, that is, having experienced childhood neglect or sexual or physical abuse. Because it is obviously not possible to randomly assign subjects to groups, the assumption of group equivalency is an approximation. The comparison group may also differ from the abused and neglected individuals on other variables nested with abuse or neglect.

Participants

The rationale for identifying the abused and neglected group was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court-substantiated cases of child abuse and/or neglect were included. Cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest from 1967 through 1971 (N = 908). To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality, and to ensure that the temporal sequence was clear (i.e., child abuse and/or neglect → subsequent outcomes), abuse and/or neglect cases were restricted to those in which children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, bone and skull fractures, and other evidence of physical injury. Sexual abuse charges ranged from felony sexual assault to “fondling or touching in an obscene manner,” rape, sodomy, and incest. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents' deficiencies in childcare were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time. These cases represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children.

A critical element of this design was the establishment of a comparison or control group, matched as closely as possible on the basis of sex, age, race, and approximate family socioeconomic status during the time period under study (1967–1971). To accomplish this matching, the sample of abused and neglected cases was first divided into two groups on the basis of their age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Children who were under school age at the time of the abuse or neglect were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (±1 week), and hospital of birth through the use of county birth record information. For children of school age, records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (±6 months); the same class in same elementary school during the years 1967 through 1971; and a home address within a five-block radius of the abused or neglected child, if possible. Overall, there were 667 matches (73.7%) for the abused and neglected children.

Matching for social class is important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse or neglect and later outcomes is confounded or explained by social class differences. It is difficult to match exactly for social class because higher income families could live in lower social class neighborhoods and vice-versa. The matching procedure used here is based on a broad definition of social class that includes neighborhoods in which children were reared and schools they attended. Similar procedures, with neighborhood school matches, have been used in studies of schizophrenics (Watt, Reference Watt1972) to match approximately for social class. A more recent textbook (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell2002) also recommended using neighborhood and hospital controls to match on variables that are related to outcomes, when random sampling is not possible. Busing was not operational at the time, and students in elementary schools in this county were from small, socioeconomically homogeneous neighborhoods.

If the control group included subjects who had been officially reported as abused or neglected, at some earlier or later time period, this would jeopardize the design of the study. Therefore, where possible, two matches were found to allow for loss of comparison group members. Official records were checked, and any proposed comparison group children who had official records of abuse or neglect in their childhood were eliminated. In these cases (n = 11), a second matched subject was assigned to the control group to replace the individual excluded. No members of the control group were reported to the courts for abuse or neglect (Widom, Reference Widom1989b); however, it is possible that some may have experienced abuse or neglect that was not reported.

The first phase of the study began as a prospective cohort design study based on an archival records check to identify a group of abused and neglected children and matched controls and conduct a criminal history search to assess the extent of delinquency, crime, and violence (Widom, Reference Widom1989a). Subsequent phases of the research involved tracing, locating, and interviewing the abused and/or neglected individuals (22–30 years after the initial court cases for the abuse and/or neglect) and the matched comparison group. Follow-up interviews were approximately 2–3 hr long and consisted of a series of structured and semistructured questions and rating scales. Throughout all waves of the study, the interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group, and to the participants' group membership. Similarly, the participants were blind to the purpose of the study. Participants were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional review board approval was obtained for the procedures involved in this study, and subjects who participated signed a consent form acknowledging that they understood the conditions of their participation and that they were participating voluntarily.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample at the different time points. The first follow-up interviews took place during 1989 to 1995 and included a psychiatric assessment as well as measures of IQ, reading ability, and basic functioning. Of the original 1,575 subject, 1,307 (83%) were located and 1,196 (76%) interviewed. Subsequent follow-up interviews were conducted in 2000–2002 (Interview 2) and 2003–2005 (Interview 3). The present study uses data from Interviews 1 and 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample at different waves of data collection

Initially, the sample was about half male (49.3%) and half female (51.7%), and about two-thirds White (66.2%) and one-third Black (32.6%). Because children were designated as primarily Black or White in the child welfare records (only a small number were identified as “Hispanic”), these percentages reflect assigned race/ethnicity. At the first interview (1989–1995), we asked participants to identify their race and ethnicity, and these self-definitions led to a higher prevalence of Hispanics in the sample. However, the sample remains predominantly White and Black, with a small group of Hispanics and others.

As can be seen in Table 1, there has been attrition associated with death, refusals, and our inability to locate individuals over the various waves of the study. However, the composition of the sample across time has remained about the same. The abuse and/or neglect group represented 56%–59% at each time period; White, non-Hispanics were 59%–66%; and males were 47%–51% of the samples. There were no significant differences across the samples on these variables or in mean age across these phases so far. In the present study, the current sample is 47.2% male, 59.3% White, non-Hispanic, and mean age is 39.5 (SD = 3.5) at Interview 2.

The average highest grade of school completed for the sample was 11.47 (SD = 2.19). Occupational status of the sample at the time of the first interview was coded according to the Hollingshead Occupational Coding Index (Hollingshead, Reference Hollingshead1975). Occupational levels of the subjects ranged from 1 (laborer) to 9 (professional). Median occupational level of the sample was semiskilled workers, and less than 7% of the overall sample was in levels 7–9 (managers through professionals). Thus, the sample overall is skewed toward the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum.

Variables and measures

Cumulative risk index

Based on prior cumulative risk literature (e.g., Appleyard et al., Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe2005; Evans & English, Reference Evans and English2002; Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2012), 12 indicators, coded as 0 (no exposure) or 1 (exposure), made up the cumulative risk index. Respondents participated in in-person interviews in which they provided information via self-report about 11 of these indicators during the first interview (1989–1995). Ten questions asked respondents about their family history before they were age 18, including questions about parental divorce, arrest, drug/alcohol abuse, sibling arrest, sibling drug/alcohol abuse, single-parent home, deceased parent, large family size (i.e., five or more children), homelessness, and removal from home (i.e., placement in foster care or institutionalization). Household economic stress, the 11th indicator, is a composite created from three self-report items (i.e., family welfare receipt, parental unemployment, and parental school dropout before completion of high school) that were standardized and averaged. In order to dichotomize this composite, participants who scored in the top 25th percentile on each composite variable were coded as 1 (high risk) and the remainder were coded as 0 (low risk).

The 12th indicator was having a documented history of child abuse and/or neglect, based on information from official records from county juvenile (family) and adult criminal courts from 1967 to 1971. Only court-substantiated cases involving children under the age of 12 at the time of abuse and/or neglect were included. Within the present sample, 78 participants (9.7%) had documented histories of physical abuse, 60 participants (7.5%) had documented histories of sexual abuse, and 368 participants (45.9%) had documented histories of neglect. Although the cases for most of the children in this sample involved only one type of abuse or neglect, a small proportion (n = 49, 6.1%) of the abused and neglected group had experienced more than one type of childhood maltreatment.

These risk factors were included in the cumulative risk index based on their associations with educational, mental health, and behavioral problems identified in previous literature (see Table 2 for references). Descriptive information for all indicators is also presented in Table 2 and correlations are presented in Table 3. To compute the cumulative risk index, dichotomous scores on the 12 indicators were summed, a standard procedure in the cumulative risk literature (for a review, see Evans, Li, & Whipple, Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013). Although 12 indicators were included, the maximum number of risk factors experienced by any participant was 11 (M = 5.20, SD = 2.59, range = 0–11).

Table 2. Variables included in the cumulative risk index, relevant citations, and percentage of sample with exposure to each risk factor

Table 3. Correlations between all variables comprising cumulative risk index

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Outcomes

Educational attainment

On average, participants reported completing 11.47 years (SD = 2.19 years) of education, with a range of 5 to 26 years. Years of education did not differ by gender. However, individuals with documented histories of abuse and/or neglect reported completing significantly fewer years of education than those in the control group (t = 8.88, p < .001), and White, non-Hispanic participants reported completing significantly more years of education than those from other racial/ethnic backgrounds (t = 3.70, p < .001).

Mental health symptoms

Current symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed in middle adulthood (2000–2002), when participants were mean age was 39.5 years.

Anxiety

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck and Steer, Reference Beck and Steer1990), a 21-item self-report scale developed to measure the severity of anxiety in clinical populations, has been used extensively in research with nonclinical samples and was used here. Respondents are asked to rate how much they have been bothered by each of the symptoms over the past week on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely—it bothered me a lot). The resulting summed scores ranged from 0 to 56 (M = 7.36, SD = 9.76). The BAI has been shown to have high internal consistency and test–retest reliability as well as good concurrent and discriminant validity (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer1988). Cronbach α for the current sample is 0.92.

Depression

We used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977), a 20-item self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptomatology in the general population. Respondents indicate how often within the past week they experienced symptoms, with responses ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). The resulting summed scores range from 0 to 56 (M = 11.42, SD = 11.44). The scale has been tested in household interview surveys and in psychiatric settings and found to have high internal consistency and adequate test–retest reliability (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). Cronbach α for the current sample is 0.91.

To create a composite variable of mental health symptomatology, scores on the BAI and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale were first summed, standardized, and then summed across the two measures to produce one composite measure of overall mental health symptomatology (M = 0.00, SD = 1.85), with higher scores indicative of more anxiety and depression symptoms. Females reported significantly more mental health symptoms than did males (t = 4.43, p < .001), but there were no race/ethnic differences in mental health symptoms. Individuals with documented histories of abuse and/or neglect reported significantly more mental health symptoms than those in the control group (t = 4.20, p < .001).

Criminal behavior

Official arrest records were collected from searches through three levels of law enforcement: local, state, and federal. These searches were conducted first in 1987 and 1988, when participants were approximately 26 years old, and then again in June 1994. In this study, adult criminal behavior was operationalized as a count of criminal arrests after age 18. Participants had experienced an average of 2.22 criminal arrests after age 18 (SD = 4.72), with a range between 0 and 45 arrests. Given the extreme skewness and kurtosis values of this variable, however, outliers were Winsorized such that they were replaced with the highest within-range values (those within 3 SD of the mean; Hoaglin, Mosteller, & Tukey, Reference Hoaglin, Mosteller and Tukey1983), resulting in a more normal distribution of arrests (M = 1.90, SD = 3.65). Individuals with documented histories of abuse and/or neglect had more arrests than those in the control group (t = 4.49, p < .001), males had significantly more arrests than females (t = 10.51, p < .001), and White, non-Hispanic participants had fewer arrests than those from other racial/ethnic backgrounds (t = 5.03, p < .001).

Statistical analysis

The present study was designed to test a series of models to examine the nature of the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and educational, emotional, and behavioral functioning in adulthood. First, descriptive statistics were computed. Second, a series of hierarchical multiple regression models were compared for each outcome to determine the nature of the relationship between cumulative childhood risk and the three outcomes. More specifically, for each outcome, linear and quadratic models were compared to determine whether a linear or curvilinear regression equation best fit the relationship between childhood cumulative risk exposure and the outcome. Third, moderation analyses were conducted to examine whether child abuse and/or neglect (using a modified version of the cumulative risk index that does not include child abuse/neglect, as described in more detail below) or gender moderates the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and the three outcomes. The main study analyses were conducted using MPlus version 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2012). Analyses controlled for participant gender and race/ethnicity, given that mean differences were found in each of the outcomes, and age at the time of the first interview, given that older participants in the study had more time and opportunity to pursue education, experience internalizing symptoms, and engage in criminal behavior. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to handle missing data, which uses all information available for each case and therefore avoids biases and loss of power (Allison, Reference Allison2003; Schafer & Graham, Reference Schafer and Graham2002).

Results

Individual risk factors and outcomes

Table 4 shows that there were significant differences in each of the outcome variables (years of education, mental health symptomatology, and criminal arrests) for many of the individual indicators of childhood risk. The majority of childhood risk factors were significantly related to at least one of these outcomes, with the exception of parental divorce and parental death.

Table 4. Educational, mental health, and criminal outcomes in adulthood by exposure to each childhood risk factor

Note: Mental health scores are standardized.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 5 presents mean years of education, mental health, and criminal arrests by number of childhood risk factors. From this preliminary analysis, it is clear that individuals exposed to any amount of risk in childhood are more likely to complete fewer years of education, report more mental health symptoms, and experience more criminal arrests in adulthood. The majority of participants in the present study were exposed to multiple risk factors in childhood.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for each outcome by number of childhood risk factors

Note: Mental health scores are standardized.

Cumulative childhood risk and adult outcomes

Table 6 presents the results of analyses examining the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and the three outcomes. For years of education, both the linear model and the quadratic models provided acceptable fit to the data (R 2 = .11, p < .001, and R 2 = .13, p < .001, respectively). Examination of the Akaike information criteria (5132.88 and 5105.58, for the linear and quadratic models, respectively) indicated that the quadratic model provided an improved fit to the data over and above the fit of the linear model. The curvilinear relationship suggests that while exposure to more childhood risk is related to fewer years of education attained, there may be a saturation effect, so that the decrease in years of education is less extreme, and appears to level off, at the higher end of the cumulative risk index.

Table 6. Linear and quadratic model comparisons for the relationship between cumulative childhood risk and all outcome variables

Note: Mental health scores are standardized. AIC, Akaike information criterion.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

In contrast, results for the models examining mental health symptomatology and criminal arrests indicated that only the linear model provided acceptable fit to the data (R 2 = .05, p < .01, and R 2 = .13, p < .001, respectively). The quadratic components were not significant for either outcome, and statistical comparison of the linear and quadratic models suggested that the quadratic models did not significantly improve the fit over and above the linear models for either outcome. These results suggest that exposure to more risk factors in childhood was significantly, positively related to symptoms of anxiety and depression and criminal arrests in adulthood.

Child abuse and/or neglect as a potential moderator

The next set of models examined whether child abuse and/or neglect moderated the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and the three outcomes. For this model, an alternative version of the cumulative risk index was created that did not include the child abuse/neglect indicator (range = 0–10, M = 4.56, SD = 2.32). To test the direct and moderation effects of child abuse and/or neglect, a dichotomous indicator of child abuse/neglect, and the interaction term (i.e., mean-centered cumulative risk indicator [without child abuse/neglect] × child abuse/neglect) were added to the best fitting model identified in the previous analyses. Results of these moderation analyses are presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Moderation effects of child abuse/neglect and gender for the relationship between cumulative childhood risk and outcomes

Note: Mental health scores are standardized.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The first model (see Table 7) examined whether child abuse and/or neglect moderated the quadratic relationship between cumulative risk and years of education. Participants with histories of child abuse or neglect reported completing fewer years of education than did controls (B = –0.66, t = 4.10, p < .001); however, this risk factor did not moderate the relationship between cumulative childhood risk and educational attainment (B = 0.07, t = 0.51, ns). As depicted in Figure 2a, saturation effects were seen for both the abused and/or neglected and the control groups, regardless of exposure to childhood cumulative risk, with controls reporting higher educational attainment in general.

Figure 2. Relationship between number of childhood risk factors and (a) years of education, (b) mental health symptomatology, and (c) adult criminal arrests in adulthood for the abused/neglected and control groups.

The second model examined whether child abuse and/or neglect moderated the linear relationship between cumulative risk and mental health symptomatology. In this model, there was a significant direct effect, so that abused and neglected children reported more symptoms of anxiety and depression in adulthood than did controls (B = 0.39, t = 2.68, p < .01); however, child abuse and/or neglect did not moderate the relationship between cumulative childhood risk and mental health symptomatology (B = −0.04, t = 0.29, ns). As shown in Figure 2b, participants with histories of child abuse or neglect consistently reported more symptoms of depression and anxiety, regardless of exposure to childhood cumulative risk.

The third model examined whether child abuse and/or neglect moderated the linear relationship between cumulative risk and criminal arrests. Although participants with histories of child abuse or neglect had significantly more criminal arrests in adulthood (B = 1.05, t = 3.61, p < .001), there was no evidence of moderation in the relationship between cumulative childhood risk and adult criminal arrests (B = −0.29, t = 1.00, ns). As depicted in Figure 2c, participants with histories of child abuse or neglect consistently had more criminal arrests in adulthood than did participants in the control group, regardless of exposure to childhood cumulative risk.

Gender as a moderator

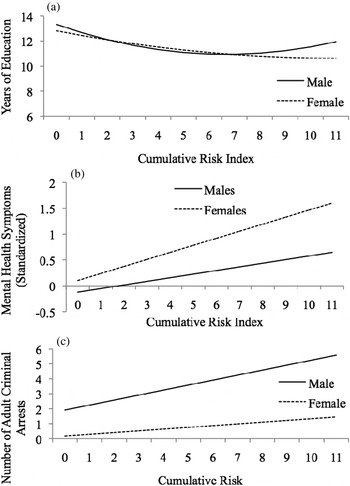

Gender was also examined as a potential moderator in the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and the outcomes in the present study, in order to determine whether the relationships differed for males and females in the present sample. Preliminary bivariate models indicated that gender was significantly related to adult mental health symptomatology (t = 4.43, p < .001), with females reporting more anxiety and depressive symptoms, and adult criminal arrests (t = 10.51, p < .001), with more arrests for males. There were no gender differences in the bivariate model examining educational attainment. In the full moderation models examining the interaction between gender and cumulative risk on these three outcomes (see Table 7), gender moderated the impact of cumulative risk on educational attainment (B = −0.24, t = 2.02, p < .05) and adult criminal arrests (B = −0.56, t = 2.21, p < .05), but not on anxiety and depressive symptoms (B = 0.17, t = 1.34, ns). Regarding educational attainment, for females, cumulative risk maintained the gradual decelerating effect that was identified with the whole sample. For males, however, our results indicated that those exposed to very high or very low risk (see Figure 3a) completed more years of education than those exposed to moderate risk in childhood. To probe this interaction, analyses examined differences in educational attainment at each value on the cumulative risk index (i.e., exposure to each number of risk factors between 0 and 11) between males and females. These analyses revealed that the relationship between cumulative risk and educational attainment was only significantly different for males and females exposed to nine or more risk factors. Regarding criminal arrests, while exposure to more risk factors was associated with more arrests for both males and females, the increase in number of arrests for those exposed to more risk factors in childhood was much steeper for males than for females (see Figure 3c). Again, this interaction was probed in the same manner, and analyses revealed that the relationship between cumulative risk and adult criminal arrests was significantly different for males and females exposed to two or more risks factors.

Figure 3. Relationship between number of childhood risk factors and (a) years of education, (b) mental health symptomatology, and (c) adult criminal arrests in adulthood for males and females separately.

Discussion

The present study sought to increase understanding of the relationship between exposure to an accumulation of risk factors in childhood and three indicators of psychosocial adjustment in adulthood: education, mental health symptomatology, and criminal behavior. The findings present a somewhat varied picture across these outcomes and provide important information regarding potential areas for intervention. In addition, this study examined whether the relationship between cumulative childhood risk and academic, mental health, and behavioral functioning differed for individuals with histories of abuse and/or neglect in comparison to a control group of individuals.

This study differs from much of the previously published literature on cumulative risk in that we examined several outcomes across three domains of adult functioning, instead of focusing on a single outcome. We found that the nature of this relationship is notably different for educational attainment in comparison to mental health symptomatology and criminal arrests. For educational attainment, findings indicated a saturation effect, that is, while there appears to be a significant drop in years of education between 0 to 2 risk factors, there appears to be less differentiation in years of education for individuals with 2 or more risk factors in childhood. For adult mental health symptomatology and criminal arrests, findings indicate a linear relationship: exposure to more childhood risk factors is related to more anxiety and depression symptomatology and more criminal arrests.

Although demonstrating a nonlinear effect, the curvilinear relationship for educational attainment is different from Rutter's (Reference Rutter, Kent and Rolf1979) threshold model, where there was an exponential increase in the particular maladaptive outcome after exposure to a certain number of risk factors. In the present study, the relationship is inverted so that at the lower end of risk exposure (zero to two risks), we see a significant decrease in educational attainment, which then levels off with exposure to more risks and remains at this lower level even as risk exposure increases. The pattern of results described here indicates that exposure to any accumulation of these risk factors may be significantly problematic regarding educational attainment. Specifically, there was a significant difference between exposure to zero, one, or two risks, but the differences between the number of risk factors above two were not significant (e.g., between four and five risks, between five and six risks, and so on). Furthermore, the decrease in years of education from 13.5 to 11.9 years between zero and two risks suggests that with exposure to two or more risk factors, an individual is less likely to obtain a high school degree. These results suggest that unless interventions can reduce childhood risk to fewer than two risk factors, traditional methods of intervention may not be effective in improving academic attainment. For situations where it is not possible to reduce risk to this low level, intervention efforts may need to focus on alternatives, such as identification of protective factors that can be instituted in attempts to combat the maladaptive effects of childhood risk exposure.

For adult mental health symptomatology and criminal arrests, the relationships with cumulative childhood risk were linear in nature. With exposure to more cumulative childhood risks, participants reported more anxiety and depression symptomatology and had more criminal arrests in adulthood, and these continued to increase with increased risk exposure. This finding suggests that eliminating any number of risk factors in childhood may be beneficial for reducing mental health problems and criminal behavior. The differences in the nature of the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and these indicators of psychosocial adjustment in adulthood suggest that intervention techniques must be carefully tailored to effectively improve these different areas of functioning.

The most effective interventions may be those that are multifaceted, addressing multiple domains of risk concurrently, in order to eliminate as many risk factors as possible. Preliminary analyses in the present study indicated that, with the exception of parental divorce and death, all of these childhood risk factors had an impact on at least one area of psychosocial adjustment in adulthood. Thus, effective interventions may involve parenting skills training that simultaneously focus on reducing parental and sibling antisocial behavior and increasing behaviors and interactions with children that foster warmth, love, and appreciation, and financial and employment issues to address socioeconomic concerns.

To ensure that no single indicator of childhood risk was accounting for the majority of the variance in educational attainment, mental health symptomatology, and criminal behavior, post hoc analyses were conducted where we removed each of the risk indicators one at a time and reran the models with that indicator excluded. The model fit for each outcome did not change based on the exclusion of any single risk indicator, suggesting that none of the childhood risk factors by themselves was responsible for the majority of the variance in any of the outcomes. (The results are available from the authors.) This provided further support for the hypothesis that it is the number of childhood risks to which individuals are exposed that affect these three later outcomes, rather than any one specific risk factor over and above others within the home environment.

In the present study, child abuse and/or neglect did not moderate the relationship between cumulative childhood risk exposure and academic, mental health, and behavioral functioning in adulthood, although there was a direct effect for all outcomes. Children with histories of abuse or neglect completed fewer years of education, reported more symptoms of anxiety and depression, and were arrested more often than controls, regardless of exposure to other childhood risk factors. Given these direct effects, our findings suggest that interventions need to target abused and/or neglected youths. However, the lack of moderation indicates that interventions may also be effective for youths exposed to multiple risk factors such as those examined here, regardless of whether or not they have a history of child maltreatment.

Our results indicate that gender interacts with cumulative risk to impact both educational attainment and criminal arrests. These moderation effects indicate that it may be important to consider tailoring interventions differently for males and females. Educational attainment among females was lower with exposure to more childhood risk factors and demonstrated a decreasing effect at the higher end of the risk index. In contrast, for males, educational attainment was lowest among those in the middle of the risk index. Although the reason for these gender differences is unclear, intervention efforts with males may demonstrate more effectiveness if focused specifically on providing support to males exposed to moderate risk. Future research efforts may shed light on these differences by identifying potential protective factors that may be playing a role in the educational attainment of males exposed to high risk.

Despite a number of strengths, several limitations of this study must be noted. First, because these cases were restricted to court-substantiated cases of child abuse and/or neglect, these findings cannot be generalized to cases that might not have come to the attention of the courts. Second, although the present study included outcome data that were collected prospectively, thus minimizing retrospective bias, the necessity of collecting data on some childhood risk factors retrospectively (aside from child abuse and/or neglect records) suggests a potential limitation of the study. However, given that much of the retrospective data was demographic and not subjective in nature, this weakness may not present a major limitation. Third, we were not able to examine the timing of risk factors, but we recognize that experiencing one risk factor may increase the risk for another (e.g., maltreatment and out of home placement). Fourth, there are limitations commonly found in cumulative risk studies (described in detail by Evans et al., Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013), including limitations in the selection of risk variables, our inability to examine dose–response relationships given our reliance on dichotomous risk factors, and the potential unaccounted for criminal behavior and educational attainments that might have occurred since the last wave of the study.

Despite these limitations, this study represents an important contribution to the literature on cumulative risk. Using a longitudinal sample spanning approximately 30 years, this study used a matched control design to compare the relationship between exposure to cumulative risk in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in middle adulthood among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Findings suggest that exposure to multiple risk factors in childhood has lasting effects on psychosocial outcomes in adulthood and that cumulative risk may be differentially related to various domains of psychosocial functioning, a finding that may shed light on the unresolved debate surrounding the suitability of linear versus nonlinear models. In addition, this study provides important information that can be used to guide effective interventions not only for children exposed to cumulative risk but also for other family members, including parents and siblings, who may contribute to risky home environments. While traditional child- or family-focused interventions may be effective in reducing some aspects of risk, future research may consider nontraditional approaches to mitigating other risk factors that play a role in affecting later psychosocial adjustment.