Psychopathy is characterized by interpersonal features such as superficial charm and grandiosity, affective features such as callousness and lack of empathy, and behavioral features such as impulsivity and antisocial behavior (Hare, Reference Hare2003). Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), a diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) significantly associated with psychopathy (Crego & Widiger, Reference Crego and Widiger2015), is characterized by the pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others. Across different version of the DSM, ASPD has been characterized more by the behavioral features of psychopathy than its affective features (Crego & Widiger, Reference Crego and Widiger2015), although the DSM-5's “emerging measures and models” section includes a more dimensional approach for diagnosis that is more convergent with the construct of psychopathy (Few, Lynam, Maples, MacKillp, & Miller, Reference Few, Lynam, Maples, MacKillop and Miller2015). Although much more research has been conducted on psychopathy than ASPD (Crego & Widiger, Reference Crego and Widiger2015), ASPD is also recognized as a disorder associated with substantial clinical, public health, and economic burden (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Chou, Saha, Smith, Jung, Zhang and Grant2017).

Low empathy is a hallmark trait of psychopathy (Hare, Reference Hare2003). However, there is not research addressing whether empathy deficits assessed as early as toddlerhood predict adulthood psychopathy. To address this gap in the literature, the present study examined whether empathy deficits assessed in toddlerhood (14 to 36 months) predict psychopathy and ASPD symptoms in adulthood (age 23 years), with the goal of early identification of individuals most at risk for stable antisocial outcomes.

Early Empathy Deficits as a Predictor of Psychopathy

Empathy is an “emotional response that is congruent with and stems from the apprehension of another's emotional state or condition” (Zahn-Waxler & Radke-Yarrow, Reference Zahn-Waxler and Radke-Yarrow1990, p. 108). Empathy includes both affective (i.e., feelings of empathic or sympathetic concern for the other person in distress) and cognitive (i.e., apprehending or understanding the other person's experience) components, and can lead to prosocial behaviors that alleviate the distress of others. Measuring empathy in toddlers is challenging. Assessments must address the emerging affective, cognitive, and behavioral components that develop in children's empathic responses (Knafo, Zahn-Waxler, Van Hulle, Robinson, & Rhee, Reference Knafo, Zahn-Waxler, Van Hulle, Robinson and Rhee2008). Despite the challenges, substantial progress has been made in constructing reliable and valid measures of empathy in young children (e.g., Davidov, Zahn-Waxler, Roth-Hanania, & Knafo, Reference Davidov, Zahn-Waxler, Roth-Hanania and Knafo2013; Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Spinrad, Damon and Eisenberg2006; Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, Reference Svetlova, Nichols and Brownell2010; Vaish, Carpenter, & Tomasello, Reference Vaish, Carpenter and Tomasello2009). Researchers have shown that the capacity for empathy and prosocial behavior occurs as early as the second year of life (Zahn-Waxler, Schoen, & Decety, Reference Zahn-Waxler, Schoen, Decety, Roughly and Schramme2018). There are also significant individual differences in empathy and prosocial behavior in very young children (Knafo et al., Reference Knafo, Zahn-Waxler, Van Hulle, Robinson and Rhee2008).

Although there is a lack of longitudinal research examining whether very early observed empathic deficits are a propensity for psychopathy in adulthood, research examining callous–unemotional (CU) traits is informative. CU traits, a childhood construct primarily characterized by empathy deficits, lack of guilt, and shallow emotions, are significantly associated with later psychopathy (Frick & Dickens, Reference Frick and Dickens2006). Several studies show that CU traits can be assessed reliably in preschool children (Kimonis et al., Reference Kimonis, Frick, Boris, Smyke, Cornell, Farrell and Zeanah2006, Reference Kimonis, Fanti, Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, Mertan, Goulter and Katsimicha2016; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Dishion, Shaw, Gardner, Wilson and Hyde2016). A recent meta-analysis indicates that there is a cross-sectional association between CU traits and conduct problem severity assessed prior to age 5 years (r = .39, p < .001; Longman, Hawes, & Kohlhoff, Reference Longman, Hawes and Kohlhoff2016). In addition, CU behaviorFootnote 1 assessed at age 3 years uniquely predicts CU behavior assessed at age 9.5 years (β = .33 to .38, p < .001), suggesting the stability of CU behavior (Waller et al., Reference Waller, Dishion, Shaw, Gardner, Wilson and Hyde2016). There is also evidence of association between interpersonal callousness in later childhood (age 7 to 12 years) and psychopathy in young adulthood (age 18 to 19 years; β = .04 to .07, p < .01 to .001; Burke, Loeber, & Lahey, Reference Burke, Loeber and Lahey2007), and between psychopathy assessed during adolescence (age 13 years) and adulthood (age 24 years; r = .31, p < .001; Lynam, Caspi, Moffitt, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, Reference Lynam, Caspi, Moffitt, Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber2007). CU traits also characterize individuals with particularly severe, aggressive, and stable antisocial behavior (Frick, Stickle, Dandreaux, Farrell, & Kimonis, Reference Frick, Stickle, Dandreaux, Farrell and Kimonis2005; Frick & White, Reference Frick and White2008). Research on CU traits led to the “limited prosocial emotions” specifier in the diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which may help identify individuals with serious antisocial behavior.

Recently, our group examined whether low “concern for others” and high “disregard for others,” two constructs negatively associated with empathy assessed very early in life (14 to 36 months), predict later conduct problems (4 to 17 years; Rhee, Friedman, et al., Reference Rhee, Friedman, Boeldt, Corley, Hewitt, Knafo and Zahn-Waxler2013; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, HInk, Johnson and Zahn-Waxler2016). “Concern for others” encompasses the behavioral, affective, and cognitive factors associated with empathic and prosocial reactions to others’ distress, such as helping the victim or proximity to the victim, whereas “disregard for others” is characterized by responding to others’ distress with active, negative responses, such as anger and hostility. Low concern for others did not predict later conduct problems, and mother-reported disregard for others was only associated with later parent-reported conduct problems, suggesting method covariance. In contrast, observed disregard for others predicted later parent- (r = .26, p = .04), teacher- (r = .34, p = .01), and self-reported (r = .36, p < .01) conduct problems and a higher order conduct problems factor (r = .51, p < .01).

These results were consistent with conclusions from previous studies suggesting that empathy deficits are not always associated with antisocial behavior. For example, although autism spectrum disorders are associated with significant empathy deficits, they are not always associated with antisocial behavior (Rogers, Viding, Blair, Frith, & Happé, Reference Rogers, Viding, Blair, Frith and Happé2006). In addition, individuals with psychopathy and autism spectrum disorders may have different types of empathy deficits (e.g., deficits in resonating with others’ distress in psychopathy and deficits in cognitive perspective taking in autism spectrum disorders; Jones, Happé, Gilbert, Burnett, & Viding, Reference Jones, Happé, Gilbert, Burnett and Viding2010). The results also supported the hypothesis that conduct problems are associated with “active” empathy deficits (i.e., reactions charged by negative affect and aggressive responses to others’ distress marked by anger and amusement) rather than the “passive” empathy deficits (i.e., a lack of either interest or capacity for empathy and prosocial behavior) that characterize autism spectrum disorders (Decety & Meyer, Reference Decety and Meyer2008).

Distinction Between Psychopathy Factor 1 and Factor 2

Although psychopathy is often described as a taxonic construct, there is evidence suggesting that it is on a continuous dimension in both children and adults (e.g., Edens, Marcus, Lilienfeld, & Poythress, Reference Edens, Marcus, Lilienfeld and Poythress2006; Marcus, Lilienfeld, Edens, & Poythress, Reference Marcus, Lilienfeld, Edens and Poythress2006; Murrie et al., Reference Murrie, Marcus, Douglas, Lee, Salekin and Vincent2007). Researchers examining several measures of psychopathy also suggest that there are two distinct factors with a weak to moderate positive correlation. Factor 1 has been called primary psychopathy (Levenson, Kiehl, & Fitzpatrick, Reference Levenson, Kiehl and Fitzpatrick1995), the interpersonal affective factor (Hare, Reference Hare2003), and the fearless dominance factor (Benning, Patrick, Blonigen, Hicks, & Iacono, Reference Benning, Patrick, Blonigen, Hicks and Iacono2005). Items loading on these factors include those assessing superficial charm, grandiosity, manipulation, shallow affect, and low empathy. Factor 2 has been called secondary psychopathy (Levenson et al., Reference Levenson, Kiehl and Fitzpatrick1995), the antisocial deviance factor (Hare, Reference Hare2003), and the impulsive antisocial factor (Benning et al., Reference Benning, Patrick, Blonigen, Hicks and Iacono2005). Items loading on these factors include those assessing impulsivity, aggression, and poor behavior control. Levenson et al. (Reference Levenson, Kiehl and Fitzpatrick1995), whose Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy scale (LSRP) is examined in the present study, used the terms primary and secondary psychopathy to describe dimensions associated with the primary and secondary psychopathy subtypes described by Karpman (Reference Karpman1941). In the present study, the terms “psychopathy factor 1” and “psychopathy factor 2” are used to describe the LSRP primary and secondary psychopathy dimensions. Although some have found that a three-factor model of the LSRP fits the data better than a two-factor model (e.g., Brinkley, Diamond, Magaletta, & Heigel, Reference Brinkley, Diamond, Magaletta and Heigel2008; Salekin, Chen, Sellbom, Lester, & MacDougall, Reference Salekin, Chen, Sellbom, Lester and MacDougall2014), evidence from analyses evaluating convergent and discriminant validity suggests that the two-factor model may still be the best way to interpret the LSRP (Salekin et al., Reference Salekin, Chen, Sellbom, Lester and MacDougall2014).

The Present Study

The present study addressed whether early empathy deficits can be identified as a propensity for adulthood psychopathy, a question not yet addressed in the literature. It extends our recent work showing that early disregard for others rated by independent observers is a significant predictor of parent-, teacher-, and self-reported conduct problems (Rhee, Friedman, et al., Reference Rhee, Friedman, Boeldt, Corley, Hewitt, Knafo and Zahn-Waxler2013; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, HInk, Johnson and Zahn-Waxler2016) by examining mother-reported and observed concern and disregard for others assessed during toddlerhood as predictors of adulthood ASPD symptoms and psychopathy.

First, we predict more robust results for observed rather than for mother-reported empathy deficits, given that there may be rater bias (e.g., tendencies toward social desirability) in the assessment of mother-reported empathy deficits used in the present study (Rhee, Boeldt, et al., Reference Rhee, Boeldt, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, Young and Zahn-Waxler2013). Given previous results’ support of the suggestion that conduct problems are associated with “active” rather than “passive” empathy deficits (Decety & Meyer, Reference Decety and Meyer2008), we hypothesized that early observed disregard for others, rather than lack of concern for others, will be associated with later ASPD symptoms and psychopathy. We hypothesized also that observed disregard for others will have stronger associations with psychopathy factor 1 than psychopathy factor 2, given that empathy deficits are a hallmark trait of psychopathy factor 1 (Levenson et al., Reference Levenson, Kiehl and Fitzpatrick1995).

Second, we examined whether the associations between toddlerhood empathy deficits and adulthood psychopathy/ASPD symptoms were significant after controlling for aggression observed during toddlerhood, to test the hypothesis that empathy deficits, not behavioral aggression alone, predict adulthood psychopathy/ASPD symptoms. We were also interested in addressing this question because the coding for disregard for others included aggressive responses to others’ distress (i.e., “hits” in mother report and “hits offending object” in the observations), and there was a moderate correlation between disregard for others and aggression (r = .41, p = .04).

Third, given significantly higher prevalence of disregard for others, ASPD symptoms, and psychopathy in boys/men than in girls/women, we explored potential sex differences in the associations, and whether they were significant after controlling for sex. Given results of previous studies, we hypothesized that the associations between disregard for others and ASPD/psychopathy would be present in both boys/men and girls/women, and that the associations would be significant after controlling for sex.

Fourth and finally, we explored whether childhood/adolescent conduct problems mediate the association between toddlerhood empathy deficits and adulthood psychopathy/ASPD symptoms, and whether toddlerhood empathy deficits have a direct influence on adulthood psychopathy/ASPD. We hypothesized that the association would be mediated by childhood/adolescent conduct problems given research demonstrating that interpersonal and affective deficits are associated with stable, severe antisocial behavior (e.g., Byrd, Loeber, & Pardini, Reference Byrd, Loeber and Pardini2012; Frick et al., Reference Frick, Stickle, Dandreaux, Farrell and Kimonis2005; Frick & White, Reference Frick and White2008). We also conducted this analysis to examine whether the association between adult psychopathy and ASPD is explained by early empathy deficits and conduct problems.

Method

Participants

Participants were from the Colorado Longitudinal Twin Study (LTS), a sample of same-sex twin pairs who were born in Colorado between 1984 and 1990 and recruited through the Colorado Department of Health. Inclusion criteria included birth weight not lower than 1000 g, gestational age of at least 34 weeks, and living within a 2-hr drive of Boulder, Colorado. More than 50% of parents meeting these criteria enrolled in the study. The ethnicity distribution of the LTS is 86.6% Caucasian, 8.5% Hispanic, 0.7% African American, 1.2% Asian, and 2.9% other. Mothers of twins had a mean of 14.29 years of education, and fathers of twins had a mean of 14.42 years of education. Additional information regarding the LTS is reported in Rhea, Gross, Haberstick, and Corley (Reference Rhea, Gross, Haberstick and Corley2006, Reference Rhea, Gross, Haberstick and Corley2013).

The present study examined data collected from age 14 months to 23 years. It examined a subset of the LTS (956 individuals; 484 girls/women and 472 boys/men) with data for at least one measure included in the study. There were 261 monozygotic twin pairs, 215 dizygotic twin pairs, and two pairs whose zygosity could not be confirmed. The sample size for each measure assessed from toddlerhood to adulthood is presented in Appendix A in the online-only Supplemental Materials. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants (the parents of the twins when they were children or the twins themselves when they were adults), and written assent was obtained from children age 7 years old and older after complete description of the study. Research protocols and consent forms were approved by University of Colorado Boulder's institutional review board.

Zygosity determination

Testers rated each twin pair's similarity on 10 physical characteristics (Nichols & Bilbro, Reference Nichols and Bilbro1966) each time participants were seen in person across the ages. Twins were coded as monozygotic if they were rated highly similar, and coded as dizygotic if 2 or more features were rated only somewhat similar or not at all similar. Zygosity was considered unambiguous if 85% of the raters agreed, and blood testing was used to resolve ambiguity in nine twin pairs. Zygosity ratings were also confirmed for all participants using 11 polymorphic DNA microsatellite markers.

Measures

The descriptive statistics of the measures described below are presented in Appendixes B and C in the online-only Supplemental Materials.

Concern and disregard for others

Observed concern and disregard for others were assessed at 14, 20, 24, and 36 months in the home and the laboratory. During separate episodes in both settings, the mother and the examiner pretended to hurt themselves for 30 s while vocalizing pain and simulating pained facial expressions, then gradually decreased their expression of distress during the next 30 s. A 30-s recording of an infant crying broadcast from a speaker (in a laboratory observation room containing 10 toys, including a baby doll) was also an empathy probe at 14, 20, and 24 months. Observers coded children's responses, including “concern for victim,” “helps victim,” “proximity to victim,” “hypothesis testing” (i.e., nonverbal or verbal attempt to understand distress; e.g., looking at the injured body part), “anger,” “hits offending object,” and “hostility.” Interobserver reliabilities ranged from .76 to .99. Different observers coded twins within a twin pair. Codes were averaged across empathy probes to maximize reliability, and then the average scores were transformed into ordinal variables given high skewness.Footnote 2 The number of categories was chosen to maximize variability while avoiding small cell sizes, and choices regarding the number of categories were made before any analyses were conducted (three or four categories for the four observed concern for others items and two categories for the three observed disregard for others items).

At 14, 20, 24, and 36 months, mothers completed an interview assessing concern (α = .74) and disregard (α = .47) for others. They were asked, “Do you ever see ___ spontaneously help (prompt: pick up things, getting dressed, offering toy)?” and asked whether their children show particular responses when either the co-twin or mother is distressed, including “approaches,” “comforts,” “hits,” “runs,” and “laughs.” Given high skewness, mother-reported concern and disregard for others were transformed into ordinal variables, with the number of categories chosen to maximize variability while avoiding small cell sizes; there were four to six categories for the four mother-rated concern for others items and four categories for the three mother-rated disregard for others items.

In a previous study, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of items from each assessment method (observed and mother reported) suggested two underlying factors at each age (Rhee, Boeldt, et al., Reference Rhee, Boeldt, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, Young and Zahn-Waxler2013). At each age, the two-factor model fit the data well. In the mother interviews, “helps,” “approaches,” and “comforts” had significant loadings on the “concern for others” factor and “hits,” “runs,” and “laughs” had significant loadings on the “disregard for others” factor. The correlations between the mother-reported “concern for others” and “disregard for others” were significant and positive at each age except age 14 months (r = .13 to .28), raising concerns regarding rater bias. In the observed measures, “concern for victim,” “helps victim,” “proximity to victim,” and “hypothesis testing” had significant loadings on the “concern for others” factor, and “anger,” “hits offending object,” and “hostility” had significantly loadings on the “disregard for others” factor. The correlations between the two factors were significant and negative at each age (r = –.14 to –.31) except 36 months. The correlations between observations and mother reports were modest and not consistently significant (.21 to .29 for concern for others and .03 to .20 for disregard for others); therefore, observed and mother-reported concern and disregard for others were examined separately.

There were several cases of bivariate missingness when examining longitudinal data from 14 to 36 months (e.g., no one who had nonzero score for both “hits offending object” at 14 months and “anger” at 24 months). Therefore, composite variables were created at each age by summing the items loading on each factor in individuals with data for all items. Given the significant skewness of the composite variables, they were transformed into ordinal variables with four categories for mother-rated concern for others, observed concern for others, and mother-rated disregard for others, and three categories for observed disregard for others (% of individuals in each category in Appendix B of the online-only Supplemental Materials). Latent variables with loadings on each time point (14, 20, 24, and 36 months), which capture common variance across time points, were examined.

Observed aggression

A free-play session in the family's living room, with toys set in a standardized array on the floor, was observed at 14, 20, and 24 months. Children played freely without interruption by the examiners or the mother for 15 min. The level of aggression (four categories from unaggressive to highly aggressive; % of individuals in each category in Appendix B of the online-only Supplemental Materials) of each twin's interactions with the co-twin was rated by coders. Each twin within a twin pair was rated by two separate coders.

Conduct problems

Conduct problems were assessed via parent and teacher report throughout childhood and self-report at age 17 years. Parent reports of conduct problems were assessed via the externalizing scale (α = .94) of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991a) at age 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, and 12 years. Teacher reports of conduct problems were assessed via the externalizing scale (α = .95) of the Teacher's Report Form (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991b) yearly from age 7 to 12 years. Given the significant skewness, the externalizing scale scores were binned into ordinal variables with four categories, with the number of categories chosen to avoid small cell sizes (% of individuals in each category in Appendix B of the online-only Supplemental Materials).

Conduct disorder symptoms were assessed via the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children—IV (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, Reference Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan and Schwab-Stone2000), a structured interview, at age 17 years. Past-year conduct disorder symptoms (as defined by the DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) were not common in the LTS, so stem questions for lifetime conduct disorder symptoms were assessed. Two items, “stealing with confrontation” (0.8%) and “forced sex” (0.1%), were dropped from the analyses because of extremely low prevalence. Prevalence of the remaining items ranged from 1.5% for cruelty to animals to 38.1% for stealing without confrontation.

In Rhee et al. (Reference Rhee, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, HInk, Johnson and Zahn-Waxler2016), we examined a hierarchical model with latent variables underlying parent-reported conduct problems (with loadings on each age), teacher-reported conduct problems (with loadings on each age), and self-reported conduct problems (with loadings on each symptom), and a higher order conduct problems factor (with loadings on the parent-, teacher-, and self-report latent variables) representing the common variance across the three informants. This model fit the data well (see Analyses section for criteria for good data fit), χ2 (296) = 420.54, p < .01, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .02.

Psychopathy

The LSRP Scale (Levenson et al., Reference Levenson, Kiehl and Fitzpatrick1995) was used to assess psychopathy at age 23 years. Items loading on the two psychopathy factors determined by Levenson et al. were summed, after reverse-scoring the appropriate items.Footnote 3 Examples of factor 1 scale items (α = .82) include “I enjoy manipulating other people's feelings” and “For me, what's right is whatever I can get away with.” Examples of factor 2 scale items (α = .63) include “I have been in a lot of shouting matches with other people” and “I don't plan anything very far in advance.” The factor 1 and factor 2 scale scores had skewness and kurtosis <1 (see descriptive statistics in Appendix C of the online-only Supplemental Materials).

ASPD symptoms

Lifetime endorsement of the seven ASPD criteria (e.g., deceitfulness and lack of remorse) were assessed at age 23 using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule–IV (Robins et al., Reference Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, Compton, North and Rourke2000), a structured clinical interview. Endorsement of the seven criteria ranged from 4.1% for deceitfulness to 34.3% for lack of remorse, and criteria for ASPD diagnosis was met by 4.5% of the sample. We examined a latent variable with loadings on the seven criteria. This model fit the data well (see Analyses section for criteria for good data fit), χ2 (34) = 65.92, p < .01, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .05, and all loadings were statistically significant.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in Mplus, version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). Most variables being ordinal necessitated the use of the weighted least squares, mean- and variance-adjusted estimation method, which uses pairwise deletion to handle missing data. In the phenotypic analyses, nonindependence of twin pairs was taken into account when computing standard errors and model fit using the TYPE=COMPLEX option (Rebollo, de Moor, Dolan, & Boomsma, Reference Rebollo, de Moor, Dolan and Boomsma2006). We had a specific, primary hypothesis that observed disregard for others would be significantly associated with psychopathy factor 1. Therefore, an α of .05 was used to determine statistical significance. The parameters’ significance was determined by p values for the z statistic, or the ratio of the parameter estimate to its standard error, but the χ2 difference test was used if there was an inconsistency between the conclusions regarding the parameter significance reached from the p value and the χ2 difference test. In addition to the χ2, supplementary fit indices less sensitive to sample size were examined. Specifically, we used a TLI (Bentler, Reference Bentler1990) >.95 and a RMSEA <.06 (Browne & Cudeck, Reference Browne, Cudeck, Bollen and Long1993) as indicative of good model fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1998).

A model examining whether the association between toddlerhood disregard for others and adulthood psychopathy factor 1/ASPD symptoms is mediated by childhood/adolescent conduct problems was tested. For the mediation model, bootstrapping with replacement on 1,000 samples was used to estimate an empirical approximation of the sample distributions of the parameters, allowing asymmetrical confidence intervals, as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2008).

The LTS is a genetically informative sample, and our previous study (Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, HInk, Johnson and Zahn-Waxler2016), found that shared environmental influences promoting disregard for others also predisposed individuals to conduct problems in later childhood and adolescence. We explored whether these shared environmental influences also influenced adulthood psychopathy and ASPD symptoms. Specifically, we estimated the magnitude of genetic and environmental influences on the associations between toddlerhood empathy deficits and adulthood psychopathy and ASPD symptoms. We also examined the association between childhood/adolescent conduct problems and adulthood psychopathy/ASPD symptoms that are due to genetic and environmental influences shard in common with toddlerhood empathy deficits. Overall, there was not adequate power to distinguish between genetic and environmental influences. Additional details regarding these analyses and results are presented in the online-only Supplemental Materials (Appendixes D to I).

Results

Associations between toddlerhood concern and disregard for others and adulthood ASPD symptoms and psychopathy

The correlation between psychopathy factor 1 and factor 2 scale scores was significant (r = .47, p < .01) and consistent with the correlation of .40 found by Levenson et al. (Reference Levenson, Kiehl and Fitzpatrick1995). The correlation between the latent ASPD variable and the psychopathy factor 2 scale score (r = .51, p < .01) was significantly higher than that between the latent ASPD variable and the psychopathy factor 1 scale score (r = .28, p < .01), Δχ2 (1) = 29.22, p < .01, which is also consistent with previous findings (e.g., Crego & Widiger, Reference Crego and Widiger2015).

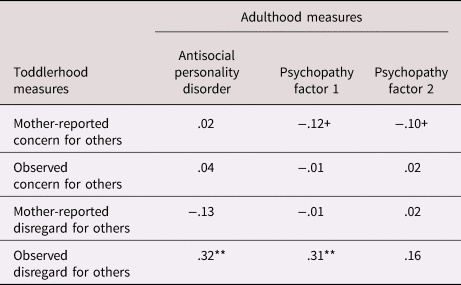

Table 1 presents the correlations between the latent variables capturing the common variance for toddlerhood concern and disregard for others assessed from 14 to 36 months and adulthood ASPD symptoms and psychopathy. There was a modest negative correlation between mother-reported concern for others and psychopathy factor 1 and factor 2. Although these correlations are in the expected direction, they were not significant. As predicted, the only significant correlations were between observed disregard for others and ASPD symptoms (r = .32, p < .01) and between observed disregard for others and psychopathy factor 1 (r = .31, p < .01); higher disregard for others was associated with higher levels of ASPD symptoms and psychopathy. In addition, as predicted, the correlation between observed disregard for others and psychopathy factor 2 was not statistically significant (r = .16, p = .10), although equating the correlations of observed disregard for others with psychopathy factor 1 and factor 2 did not lead to a significant decrement in the fit of the model, Δχ2 (1) = 1.96, p = .16. Observed disregard for others assessed during toddlerhood was not associated with later participation in the study during adulthood (r = .05, p = .73).

Table 1. Correlations between toddlerhood concern and disregard for others and adulthood antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy

Note: Latent variables with loadings on each time point were examined for the toddler measures, and a latent variable with loadings on each criterion was examined for antisocial personality disorder. χ2 (256) = 339.54, p < .01, Tucker–Lewis index = .95, root mean square error of approximation = .02. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Given the correlation of .47 between psychopathy factor 1 and factor 2, we examined whether observed disregard for others was associated with each psychopathy scale after controlling for the other. The regression of psychopathy factor 1 on observed disregard for others remained significant after controlling for psychopathy factor 2 (β = .25, p = .02), but the regression of psychopathy factor 2 on observed disregard for others after controlling for psychopathy factor 1 was near zero (β = .02, p = .78). The regression of ASPD symptoms on observed disregard was significant after controlling for either factor 1 (β = .33, p = .03) or factor 2 (β = .32, p = .01) psychopathy or both (β = .32, p = .02), suggesting that the association between observed disregard for others and ASPD symptoms is not mediated by psychopathy.

Appendix J in the online-only Supplemental Material presents the correlations between observed disregard for others assessed at each age and ASPD and psychopathy assessed in adulthood. Observed disregard for others assessed at 14 and 20 months was significantly associated with psychopathy factor 1, and observed disregard for others at 24 months was significantly associated with ASPD. Observed disregard for others assessed at 36 months was not significantly associated with any outcome.

Toddlerhood observed aggression was significantly correlated with toddlerhood observed disregard for others (r = .41, p = .04) and adulthood ASPD symptoms (r = .22, p = .05), but not with psychopathy factor 1 (r = –.03, p = .69) or factor 2 (r = .07, p = .44). In the analysis regressing psychopathy factor 1 on disregard for others and aggression, disregard for others was significantly associated with psychopathy factor 1 after controlling for aggression (β = .36, p = .01). Aggression was not associated with psychopathy factor 1 after controlling for disregard for others (β = –.15, p = .26). Similarly, disregard for others was significantly associated with ASPD after controlling for aggression (β = .36, p = .05), but aggression was not associated with ASPD after controlling for disregard for others (β = .07, p = .66).

ASPD symptoms’ correlation with psychopathy factor 2 was greater than that with psychopathy factor 1, consistent with other findings in the literature (Crego & Widiger, Reference Crego and Widiger2015). This is not surprising, given that the ASPD criteria include mostly behavioral symptoms. For example, Patrick (Reference Patrick, O'Donohue, Fowler and Lilienfeld2007) noted that only two of the seven ASPD criteria (i.e., deceitfulness and lack of remorse) intersect with the emotional and interpersonal features of factor 1 (or interpersonal affective factor) of the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (Hare, Reference Hare2003). It is somewhat surprising that disregard for others had a significant association with ASPD symptoms despite a higher correlation between ASPD symptoms with psychopathy factor 2 than psychopathy factor 1. Therefore, we conducted exploratory analyses examining the correlation between disregard for others and each ASPD criterion (see Appendix K in the online-only Supplemental Materials). Disregard for others was significantly correlated with three of the seven criteria, including deceitfulness and lack of remorse.

Sex differences

Regressing observed disregard for others (β = .86, p < .01), ASPD symptoms (β = .48, p < .01), psychopathy factor 1 (β = .65, p < .01), and psychopathy factor 2 (β = .36, p < .01) on sex showed that all of these variables were significantly higher in boys/men than in girls/women. We examined whether the association between toddlerhood observed disregard for others and adult outcomes was significant after controlling for sex. The regression of psychopathy factor 1 on observed disregard for others remained significant after controlling for sex (β = .21, p = .03), and the regression of ASPD symptoms on observed disregard for others was marginally significant after controlling for sex (β = .21, p = .07). The association between observed disregard for others and psychopathy factor 2 (β = .05, p = .55) remained nonsignificant after controlling for sex. The sex effects on ASPD symptoms (β = .48, p < .01), psychopathy factor 1 (β = .65, p < .01), and psychopathy factor 2 (β = .36, p < .01) remained significant after controlling for observed disregard for others, suggesting that the sex differences in the adult outcomes are not explained by earlier observed disregard for others.

We also examined potential sex moderation. Specifically, we analyzed boys/men and girls/women in separate groups, and then examined whether the correlations between toddlerhood observed disregard for others and adult outcomes could be constrained to be equal across boys/men and girls/women.Footnote 4 The correlations between observed disregard for others and psychopathy factor 1, Δχ2 (1) = 0.05, p = .82, and between observed disregard for others and psychopathy factor 2, Δχ2 (1) = 0.69, p = .41, could be constrained across sex. There was a statistical trend of a significant sex difference in the correlation between observed disregard for others and ASPD symptoms in boys/men and girls/women, Δχ2 (1) = 3.51, p = .06; r boys/men = .44, p < .01, r girls/women = –.04, p = .84.

Does childhood/adolescent conduct problems mediate the association between toddlerhood observed disregard for others and adulthood psychopathy factor 1/ASPD symptoms?

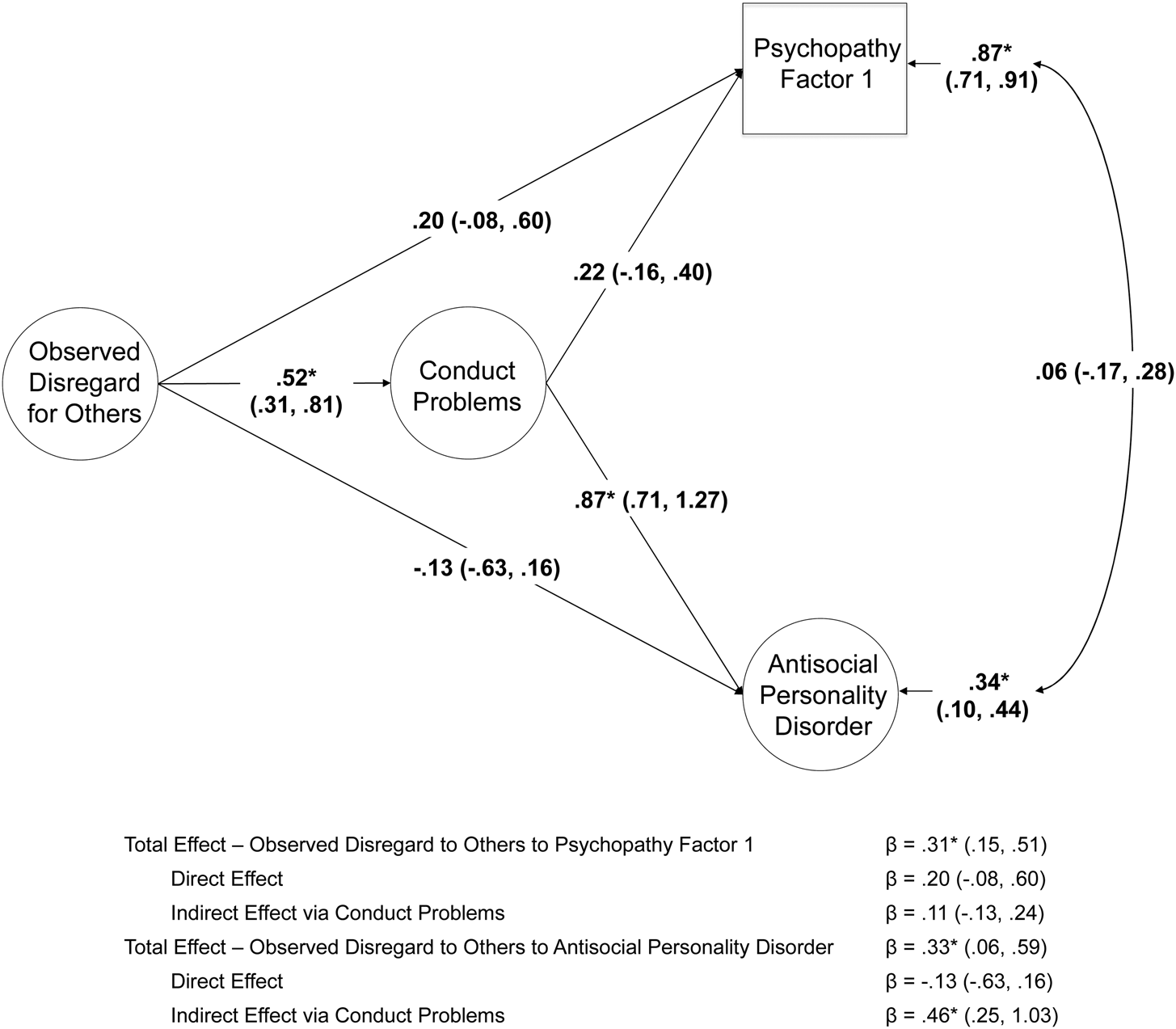

Figure 1 presents the results of a model testing whether the association between toddlerhood observed disregard for others and adulthood psychopathy factor 1/ASPD symptoms is mediated by childhood/adolescent conduct problems. Disregard for others did not have a direct influence on either psychopathy factor 1 or ASPD symptoms. The indirect effect via childhood/adolescent conduct problems was significant for ASPD symptoms, but not psychopathy factor 1. The residual correlation between psychopathy factor 1 and ASPD symptoms was not significant.

Figure 1. Association between toddlerhood observed disregard for others and adulthood psychopathy factor 1/antisocial personality disorder mediated by childhood/adolescent conduct problems (higher order factor with loadings on parent-, teacher-, and self-reported conduct problems). Standardized parameters and 95% confidence intervals are presented. *p < .05.

Discussion

The primary goal of the present study was to examine whether empathy deficits assessed very early in life (age 14 to 36 months) predict symptoms of ASPD and psychopathy in adulthood (age 23 years). Consistent with our hypotheses, toddlerhood observed disregard for others, not low concern for others, was a modest but significant predictor of adulthood psychopathy factor 1, but not factor 2. Moreover, the associations between disregard for others and psychopathy factor 1 were similar in boys/men and girls/women and significant after controlling for sex.

These results bolster previous suggestions that conduct problems and antisocial behavior are associated with “active,” not “passive,” empathy deficits (Decety & Meyer, Reference Decety and Meyer2008; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Happé, Gilbert, Burnett and Viding2010), and may help explain the lower than expected association between empathy deficits and aggression found in the literature (Vachon, Lynam, & Johnson, Reference Vachon, Lynam and Johnson2014). Moreover, our findings suggest that these deficits can be observed in the second year of life in the form of active disregard for others in distress. They also suggest that psychopathy factors 1 and 2 have differing correlates and predictors. This conclusion is further supported by results from recent studies suggesting that executive functioning deficits (Friedman, Rhee, Ross, Corley, & Hewitt, Reference Friedman, Rhee, Ross, Corley and Hewittin press) and internalizing disorders (e.g., Eisenbarth et al., Reference Eisenbarth, Godinez, du Pont, Corley, Stallings and Rhee2019) are associated with factor 2, not factor 1, psychopathy.

Responses to others’ distress are assessed more reliably in older than younger toddlers (Nichols, Svetlova, & Brownell, Reference Nichols, Svetlova and Brownell2015), and the ability to view harming others as wrong increases across toddlerhood (Dahl & Freda, Reference Dahl, Freda, Sommerville and Decety2017). In contrast to results expected by these findings, the association between observed disregard for others and psychopathy factor 1 was significant for observed disregard for others assessed at 14 and 20 months, not 24 and 36 months. First, it is possible that these results may be spurious. A second possibility is that observed disregard for others at earlier ages is a better measure of the individual risk for antisocial propensity than that assessed at later ages, which may have more heterogeneous etiology. For example, one study reported that parental harshness was associated with increases in CU behavior from age 2 to 4, over and above earlier behavior problems (e.g., Waller et al., Reference Waller, Gardner, Hyde, Shaw, Dishion and Wilson2012). A third possibility is that the construct validity of observed disregard for others is lower at 36 months, when the empathy probes may not seem as genuine because the children have had several previous exposures to the empathy probes by then.

There was also a significant association between toddlerhood observed disregard for others and ASPD symptoms, although ASPD symptoms correlated more strongly with psychopathy factor 2 than with psychopathy factor 1. Exploratory post hoc analyses showed that disregard for others correlated significantly with the two ASPD criteria that intersect with the emotional and interpersonal features of psychopathy (Patrick, Reference Patrick, O'Donohue, Fowler and Lilienfeld2007), and only one of the other ASPD criteria intersecting with the behavioral features of psychopathy.

Toddlerhood observed disregard for others and aggression were significantly correlated, and aggression was significantly correlated with adulthood ASPD symptoms (although not with psychopathy). Observed disregard for others predicted both psychopathy factor 1 and ASPD symptoms even after controlling for toddlerhood observed aggression, where aggression predicted neither psychopathy factor 1 nor ASPD symptoms after controlling for disregard for others. These results suggest that the significant associations in the present study are not explained by the simple continuity of aggression or conduct problems from toddlerhood to adulthood or the inclusion of aggressive responses to others’ distress in the assessment of disregard for others.

Observed disregard for others’ association with adulthood ASPD symptoms was mediated by childhood/adolescent conduct problems, and the direct effect of observed disregard for others was not significant. The overall association between observed disregard for others and adulthood psychopathy factor 1 was significant, but neither the direct nor indirect effects were significant. The lack of direct effect of observed disregard for others suggests the possibility that addressing conduct problems in childhood or adolescence may mitigate the stable continuation of interpersonal and affective deficits into adulthood. Interesting as well is the result that the residual correlation between adulthood psychopathy factor 1 and ASPD symptoms was small and not significant, suggesting that its association is explained largely by earlier disregard for others and conduct problems.

Implications for early identification and prevention

The present study's results suggest that the propensity toward adulthood ASPD symptoms and psychopathy, especially psychopathy factor 1, can be identified early in development. They also suggest that early assessment of disregard for others may help identify those most at risk for antisocial outcomes that persists into adulthood. These results are consistent with other findings suggesting stability of CU and psychopathic traits from toddlerhood to childhood (e.g., Waller et al., Reference Waller, Dishion, Shaw, Gardner, Wilson and Hyde2016) and childhood to adulthood (e.g., Burke et al., Reference Burke, Loeber and Lahey2007).

Researchers who conducted the first seminal studies on the development of empathy have suggested that assessment of empathy in young children may be improved by the use of objective measures, such as autonomic responses and facial expressions (e.g., Zahn-Waxler & Radke-Yarrow, Reference Zahn-Waxler and Radke-Yarrow1990). There has been significant advancement in this area of research; recent studies have demonstrated distinctive neural responses to others’ harm (e.g., Decety & Cowell, Reference Decety and Cowell2018; Decety, Meidenbauer, & Cowell, Reference Decety, Meidenbauer and Cowell2017), prosocial and antisocial actions (e.g., Cowell & Decety, Reference Cowell and Decety2015), and fearful emotional body expressions (Rajhans, Missana, Krol, & Grossmann, Reference Rajhans, Missana, Krol and Grossmann2015) in infants and young children. In addition, children's prosocial behavior is predicted by neural responses to others’ distress (Decety et al., Reference Decety, Meidenbauer and Cowell2017).

In a recent review, Waller and Hyde (Reference Waller and Hyde2017) discussed the ethical implications of studying CU behaviors in early childhood. They cautioned against inadvertently conveying that “preschool psychopaths” can be identified, given that CU traits are only weakly to moderately related to psychopathy, or suggesting that CU behaviors are purely genetic or untreatable. Our results support their caution, given that toddlerhood disregard for others, which is largely influenced by shared environmental influences (Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, HInk, Johnson and Zahn-Waxler2016), had a modest association with adulthood psychopathy.

There has been some disagreement in the literature regarding whether psychopathy and CU traits are resistant to treatment (Hawes & Dadds, Reference Hawes and Dadds2005, Reference Hawes and Dadds2007; Salekin, Reference Salekin2002). However, there is general consensus that it is important to identify individuals most at risk for psychopathy as early as possible in order to maximize the potential for prevention (Frick, Reference Frick2016; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Shaw, Neiderhiser, Ganiban, Natsuaki, Reiss and Hyde2017). In addition, the development of potential prevention strategies of psychopathy in individuals most at risk for stable antisocial outcomes is an important future direction. The significance of shared environmental influences on observed disregard for others suggests that the family environment may be an important target for prevention, and several lines of research provide supportive evidence.

Preventing childhood maltreatment may be an important prevention strategy. The influence of maltreatment on the interpersonal features of psychopathy begins early. Physically abused toddlers and young children exhibit more aggression toward peers in distress than those who were not abused (Klimes-Dougan & Kistner, Reference Klimes-Dougan and Kistner1990; Main & George, Reference Main and George1985). The influence of childhood maltreatment on adulthood psychopathy is persistent (Weiler & Widom, Reference Weiler and Widom1996), and the association between childhood maltreatment and adulthood psychopathy is strongest between physical abuse and the antisocial features of psychopathy (Dargis, Newman, & Koenigs, Reference Dargis, Newman and Koenigs2016).

Another important facet of early prevention is the enhancement of positive parenting. First, several researchers have noted the importance of early socializing interactions with parents in the development of empathy, such as parental directiveness or parents explaining how a victim feels (e.g., Janssens & Gerris, Reference Janssens, Gerris, Janssens and Gerris1992; Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow, & King, Reference Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow and King1979). Second, the negative association between positive parenting and CU traits is significant even after controlling for the effects of maltreatment (Kimonis, Cross, Howard, & Donoghue, Reference Kimonis, Cross, Howard and Donoghue2013), and there is a prospective association between both negative and positive parenting and CU traits (Waller, Gardner, & Hyde, Reference Waller, Gardner and Hyde2013). Moreover, the protective effect of early positive parenting against the development of CU traits is environmentally mediated (i.e., not due to confounding with gene–environment correlation). For example, in a recent adoption study, Hyde et al. (Reference Hyde, Waller, Tretacosta, Shaw, Neiderhiser, Ganiban and Leve2016) found that adoptive mother positive reinforcement assessed at 18 months protected against CU behaviors assessed at 27 months, and that high levels of positive reinforcement buffered against the heritable risk for CU behaviors. Similarly, a study examining monozygotic twin differences in parental harshness and warmth found that the twin who received less harsh parenting and more parental warmth had lower CU traits (Waller, Hyde, Klump, & Burt, Reference Waller, Hyde, Klump and Burt2018). Additional evidence comes from recent studies reporting that the influence of the Fast Track interventionFootnote 5 on reductions of the level of CU traits was mediated by higher parental warmth (Pasalich, Witkiewitz, McMahon, Pinderhughes, & Conduct Problems Prevention Group, Reference Pasalich, Witkiewitz, McMahon and Pinderhughes2016), and that the positive effects of a parent training intervention on CU traits was mediated by positive parenting (Kjøbli, Zachrisson, & Bjørnebekk, Reference Kjøbli, Zachrisson and Bjørnebekk2018). In addition, a recent open trial pilot study reported that parent–child interaction therapy with a focus on positive parenting strategies led to significant decreases in conduct problems and CU traits and increases in empathy in preschoolers (Kimonis et al., Reference Kimonis, Fleming, Briggs, Brouwer-French, Frick, Hawes and Dadds2019).

In regard to prevention and intervention strategies directed at children at risk of developing psychopathy, a review examining the neurocognitive vulnerabilities of children with CU traits suggests that consistent reward-based interventions may be more effective than those using punishment (Viding & McCrory, Reference Viding and McCrory2012). Children with CU traits are relatively insensitive to punishment (Frick & Viding, Reference Frick and Viding2009), and aggressive children who experience greater parental warmth and lower physical punishment show greater decrease in CU traits (Pardini, Lochman, & Powell, Reference Pardini, Lochman and Powell2007). Results from a pilot intervention study suggesting a lower emphasis on punishment (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Haas, Waschbusch, Willoughby, Helseth, Crum and Pelham2014) and a case study suggesting rewards delivered using specific and predictable treatment goals in children with CU traits (Waschbusch et al., Reference Waschbusch, Bernstein, Mazzant, Willoughby, Haas, Coles and Pelham2016) support these ideas. More recently, a comparison between personalized behavioral treatment emphasizing rewards and de-emphasizing punishments and standard behavior therapy showed mixed results across outcome measures (Waschbusch et al., Reference Waschbusch, Willoughby, Haas, Ridenour, Helseth, Crum and Pelhamin press). Additional research regarding these reward-based interventions is needed.

Strengths and limitations of the present study

There is a lack of literature on very early predictors of adult psychopathy, despite suggestions that the interpersonal affective deficits of psychopathy begin early in life (e.g., Dadds, Jambrak, Pasalich, Hawes, & Brennan, Reference Dadds, Jambrak, Pasalich, Hawes and Brennan2011; Kimonis et al., Reference Kimonis, Fanti, Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, Mertan, Goulter and Katsimicha2016). The present study is the first to demonstrate that empathy deficits assessed in toddlerhood predict psychopathy and ASPD symptoms in adulthood. It built upon previous work by examining longitudinal data spanning toddlerhood, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, allowing us to demonstrate that the association between toddlerhood empathy deficits and adulthood ASPD symptoms is mediated by childhood/adolescent conduct problems. Another strength is the multimethod assessment of concern and disregard for others, including observational data.

The results of the present study should be interpreted while considering the following limitations. Several aspects of the sample may limit the generalizability of the results. The present study examined a twin sample, and we did not directly assess the potential influence of having a same-age, same-sex sibling. The sample examined was mostly Caucasian. In addition, the present study examined a community sample with low levels of ASPD and psychopathy. However, a significant association between observed disregard for others and externalizing problems has been reported in a study that oversampled children with subclinical and clinical levels of externalizing problems (Hastings, Zahn-Waxler, Robinson, Usher, & Bridges, Reference Hastings, Zahn-Waxler, Robinson, Usher and Bridges2000), suggesting that these results may replicate in clinical samples as well.

There were some limitations to the assessments used in the present study. The correlations between the mother-reported and observed empathy deficits were low, and the correlations between mother-reported concern and disregard for others were positive, raising concerns regarding rater bias. Additional assessments appropriate for preschool children, such as CU behaviors (e.g., Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2017), would have strengthened the study. The assessment of toddlerhood aggression was limited to observations, as parent or teacher ratings were not available. In addition, the LSRP primary psychopathy scale does not capture fearlessness or boldness, unlike other measures of psychopathy (Drislane, Patrick, & Arsal, Reference Drislane, Patrick and Arsal2014). Finally, although the present study's sample was large, there was a lack of power to distinguish between the effect sizes for the association between disregard for others and psychopathy factor 1 versus factor 2 and between the genetic and environmental influences on the association between disregard for others and psychopathy factor 1.

There are significant shared environmental, but not genetic, influences on disregard for others (Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Friedman, Corley, Hewitt, HInk, Johnson and Zahn-Waxler2016). Although this result seems inconsistent with findings that antisocial behavior with CU traits, including those present in childhood, are particularly heritable (Viding, Reference Viding2004), this discrepancy may be explained by differences in age of assessment and assessment method. Researchers have found greater evidence of shared environmental influences in studies using observational assessments in young children compared to those using parent report or self-report, which cannot be used in young children (e.g., Kendler & Baker, Reference Kendler and Baker2007; Roisman & Fraley, Reference Roisman and Fraley2006). These differing results may be due to differing limitations of the two methods. Parent reports are influenced by the rater contrast effect, or exaggeration of differences between their dizygotic infants (Loehlin, Reference Loehlin1992). In contrast, observations are based on ratings by unbiased, trained individuals. Parent reports provide a general perspective of behaviors across situations and time, whereas observations are usually based on short segments of behavior. In the present study, this time-specific limitation of observational measures was offset by examining a latent factor of observations of empathy deficits across four time points.

Conclusions

Toddlerhood disregard for others, rather than lack of concern for others, had a modest but significant association with ASPD symptoms and psychopathy assessed in adulthood, and early disregard for others was significantly associated with psychopathy factor 1, but not factor 2. These results are consistent with the hypotheses that antisocial behavior is associated with “active” rather than “passive” empathy deficits, and that empathy deficits are a hallmark trait of psychopathy factor 1. The assessment of early disregard for others may facilitate the identification of individuals with a propensity toward adulthood ASPD symptoms and psychopathy factor 1 for early prevention.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419001676.

Acknowledgments

We thank Corinne Gunn, Sally Ann Rhea, and the participants. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the biannual meeting of the Society for Research on Child Development on April 6, 2017.

Financial support

This study was supported by the MacArthur Foundation, the Fetzer Foundation, and National Institutes of Health grants MH016880, HD007289, DA017637, HD010333, HD050346, DA011015, and AG046938.