Since the advent of the seminal Centers for Disease Control (CDC)/Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Study in the mid-1990s, research has consistently found graded relationships between cumulative ACEs (traditionally defined as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction) and maladaptive physical and psychosocial outcomes in adulthood (e.g., Anda et al., Reference Anda, Felitti, Bremner, Walker, Whitfield, Perry and Giles2006; Giovanelli, Reynolds, Mondi, & Ou, Reference Giovanelli, Reynolds, Mondi and Ou2016; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004; Danese et al., Reference Danese, Moffitt, Pariante, Ambler, Poulton and Caspi2008; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Giles, Felitti, Dube, Williams, Chapman and Anda2004; Kelly-Irving et al., Reference Kelly-Irving, Lepage, Dedieu, Bartley, Blane, Grosclaude, Lang and Delpierre2013; Nurius, Logan-Greene, & Greene, Reference Nurius, Logan-Greene and Green2012; Turner & Lloyd, Reference Turner and Lloyd2004). Adverse childhood experiences studies, many of which have been published in prominent medical journals, have increased awareness of the long-term consequences of ACEs and the molecular mechanisms through which adversity contributes to poor outcomes (e.g., alterations in brain structure, neuroendocrine stress, immune functioning and inflammation, metabolism; Berens, Jensen, & Nelson, Reference Berens, Jensen and Nelson2017; Bush, Lane, & McLaughlin, Reference Bush, Lane and McLaughlin2016; Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012; Koss & Gunnar, Reference Koss and Gunnar2018; McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic, & Tottenham, Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019). Changes at the biological level are crucial; however, a developmental psychopathology perspective (Cicchetti & Cohen, Reference Cicchetti and Cohen2006; Cummings & Valentino, Reference Cummings, Valentino, Overton and Molenaar2015) requires exploration of the effects of adversity across levels of the eco-biodevelopmental system.

It bears mentioning that the term “ACEs” and the current ACE research as it is known today emerged in a medical and epidemiological context; however, adversity, life stress, and resilience over the life-course had been subjects of developmental and medical research for decades prior to the first CDC ACE studies (e.g., Masten & Garmezy, Reference Masten, Garmezy, Lahey and Kazdin1985; Rutter, Reference Rutter1979; Werner, Reference Werner1989). Generally, such research has taken a far more comprehensive and nuanced approach than that of the ACE research. The present paper seeks to use this developmental lens to enhance the utility and relevance of the highly influential and resonant ACE framework.

From this perspective, three major questions remain largely open vis a vis the effects of cumulative ACEs: (a) what are the psychosocial processes through which ACEs contribute to adverse outcomes, including broader social and economic outcomes (e.g., educational attainment, crime); (b) what scalable strategies can be employed to promote resilience among ACE-affected populations; and (c) how can we shift the field of ACE research to a transactional-ecological perspective of ACE effects over the life-course? The present study advances the literature by examining these three questions in the context of a longitudinal early intervention study spanning over three decades.

This introduction will provide a brief overview of relevant theoretical frameworks and research on the associations between ACEs and development over the life course. Next, it will touch on the complex relationships between poverty and ACEs. Finally, it will review evidence of the role that early intervention can play in initiating healthier developmental trajectories for ACE-affected children, which leads into the present study's empirical investigation.

Disrupted Neurodevelopment

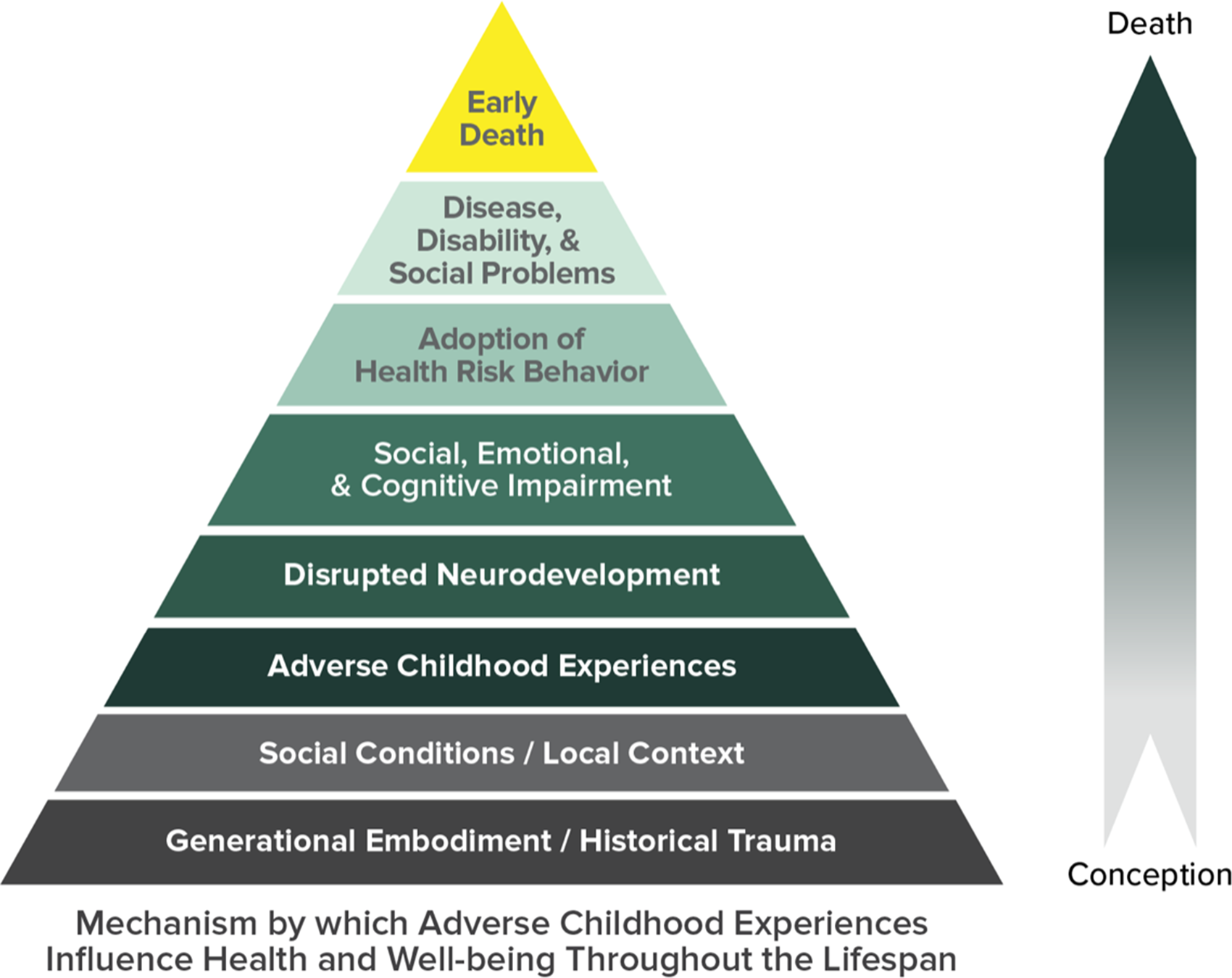

Medical and developmental researchers have applied a number of theoretical frameworks to study ACEs and the mechanisms of their influence on developmental outcomes. The ACE pyramid (Figure 1), originally created by the CDC, illustrates the hypothesized mechanisms by which ACE effects are transmitted over the life-course. As Figure 1 shows, these mechanisms primarily operate via a cascading effect that begins with ACE-related disruptions in neurodevelopment. These processes are situated within larger sociocultural contexts, represented by the foundational layers of the pyramid.

Figure 1. ACE pyramid (Centers for Disease Control, CDC).

Alterations in the structure and function of neurophysiological systems in response to ACEs have been termed the “biological embedding of early experiences” (Hertzman, Reference Hertzman1999). Research has demonstrated that ACEs can cause prolonged inflammation and systemic pathology as well as psychopathology, especially when ACEs are severe, chronic, or occur during sensitive periods (Anda et al., Reference Anda, Felitti, Bremner, Walker, Whitfield, Perry and Giles2006; Andersen & Teicher, Reference Andersen and Teicher2008; Berens et al., Reference Berens, Jensen and Nelson2017; Bremner, Reference Bremner2003; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lane and McLaughlin2016; Cicchetti & Cannon, Reference Cicchetti and Cannon1999; Crews, He, & Hodge, Reference Crews, He and Hodge2007; Danese & McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012; Koss & Gunnar, Reference Koss and Gunnar2018; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019; Perry & Pollard, Reference Perry and Pollard1998; Pervanidou & Chrousos, Reference Pervanidou and Chrousos2012). The alterations at the level of behavioral and psychosocial functioning that can result from these neural changes are quite relevant for interventionists, as they can be targeted and influenced by environmental supports (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019).

Cumulative Effects and Psychosocial Processes

Adverse childhood experience-related alterations in neurophysiological functioning can influence well-being directly through inflammation and allostatic load. Evidence suggests that these alterations are also dose-dependent, with effects accumulating commensurate with ACE exposure (Anda et al., Reference Anda, Felitti, Bremner, Walker, Whitfield, Perry and Giles2006). The neurodevelopmental impairment resulting from the stress response that often accompanies ACEs can initiate a developmental cascade of impaired cognitive, social, and emotional functioning (represented by subsequent, ascending levels of the pyramid in Figure 1). This is often referred to as cumulative effects theory, wherein risk factors tend to accrue over time, progressively increasing the probability of negative outcomes (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer1987; Evans, Li, & Whipple, Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013; Pollard, Hawkins, & Arthur, Reference Pollard, Hawkins and Arthur1999; Rutter, Reference Rutter1979). In short, ACEs beget ACEs. This pattern of exacerbated impairment with increasing doses of ACEs has been borne out in research reporting dose–response relationships between cumulative ACEs and a panoply of outcomes (Anda et al., Reference Anda, Felitti, Bremner, Walker, Whitfield, Perry and Giles2006).

Research shows that this cascade increases the likelihood that individuals will engage in health risk behaviors as compensatory or coping mechanisms. These behaviors (e.g., substance use, overeating) have, along with alterations in information/reward processing and emotion regulation associated with threat or deprivation, been causally linked to adverse outcomes (Dube et al., Reference Dube, Felitti, Dong, Chapman, Giles and Anda2003; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019; Van der Kolk, Perry, & Herman, Reference Van der Kolk, Perry and Herman1991). These factors are part of the story regarding the mechanisms through which social, emotional, and cognitive impairment contribute to maladaptation; however, this continues to be a fertile area of inquiry, particularly regarding mechanisms that can be translated to scalable primary and secondary prevention (e.g., social support, sleep, exercise; Giovanelli et al., Reference Giovanelli, Reynolds, Mondi and Ou2016; Nurius et al., Reference Nurius, Green, Logan-Greene and Borja2015).

Resilience: Promotive and Protective Factors

The concept of resilience, or “good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or development” (Masten, Reference Masten2001), is central to any discussion of psychosocial processes of adversity. As evident in Figure 1, ACE research is traditionally presented within a cumulative disadvantage or deficit framework. However, outside of the ACE field, the literature has long demonstrated that early adversity can be counteracted or overcome through the accumulation of protective factors and through promoting processes of resilience (Garmezy, Reference Garmezy and Stevenson1985; Lazar et al., Reference Lazar, Darlington, Murray, Royce, Snipper and Ramey1982; Singh-Manoux, Ferrie, Chandola, & Marmot, Reference Singh-Manoux, Ferrie, Chandola and Marmot2004). The other side of cumulative effects theory, cumulative advantage, can promote resilience and can be conferred through intervention programs (Consortium for Longitudinal Studies, 1983; Schweinhart & Weikart, Reference Schweinhart and Weikart1980; Walberg & Tsai, Reference Walberg and Tsai1983). For example, research has shown that participation in the Child–Parent Center intervention program has compensatory benefits for children affected by high levels of demographic and economic risk factors (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Robertson, Mersky, Topitzes and Niles2007; Reynolds, Temple, White, Ou, & Robertson, Reference Reynolds, Temple, White, Ou and Robertson2011).

A number of studies have also investigated factors promoting resilience within an ACE framework (e.g., family and social support, sleep, exercise, a range of positive childhood experiences; Allem, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, Reference Allem, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati and Unger2015; Chandler, Roberts, & Chiodo, Reference Chandler, Roberts and Chiodo2015; Narayan, Rivera, Bernstein, Harris, & Lieberman, Reference Narayan, Rivera, Bernstein, Harris and Lieberman2018; Nurius et al., Reference Nurius, Green, Logan-Greene and Borja2015; Bethell, Newacheck, Hawes, & Halfon, Reference Bethell, Newacheck, Hawes and Halfon2014), and several neurodevelopmental processes linking ACEs and impaired functioning have been identified (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019). However, resilience is not accounted for in the CDC ACE pyramid model, and our understanding of the psychosocial mechanisms through which resilient functioning may be conferred in the face of ACEs continues to evolve. The benefit of employing a contextual theoretical approach to identify the processes that shape the development of ACE-affected individuals cannot be overstated, particularly regarding the potential utility of such information for intervention efforts.

Transactional-Ecological Perspectives

Figure 1 is useful in understanding ACE processes to a point; however, it fails to illustrate the transactions across levels of the model, which are central to processes of resilience. Transactional-ecological models (Cicchetti & Lynch, Reference Cicchetti and Lynch1993) and various dynamic transactional models broadly hypothesize that processes occurring across levels of the ecobiodevelopmental system interact to shape development (Belcher, Volkow, Moeller, & Ferré, Reference Belcher, Volkow, Moeller and Ferré2014; Cicchetti & Garmezy, Reference Cicchetti and Garmezy1993; Halfon, Larson, Lu, Tullis, & Russ, Reference Halfon, Larson, Lu, Tullis and Russ2014; Heim & Binder, Reference Heim and Binder2012; Luthar, Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Cohen2006; Masten & Obradović, Reference Masten and Obradović2006; Rutter, Reference Rutter, Rolf, Masten, Cicchetti, Neuchterlein and Weintraub1990; Shonkoff et al., Reference Shonkoff, Garner, Siegel, Dobbins, Earls and McGuinn2012), and there is also a critical need for research that examines these interactions vis a vis the development of ACE-affected individuals.

Transactional-ecological models allow investigators to parse the processes that underlie the outcomes associated with ACE exposure (Davies, Reference Davies1999; Guterman, Reference Guterman2000; Nurius, Green, Logan-Greene, & Borja, Reference Nurius, Green, Logan-Greene and Borja2015). Through this lens, ACEs can be conceptualized as stressors that (a) are situated in the context of current and historic social conditions and environments (e.g., socioeconomic status; community characteristics); (b) reduce adaptive capacities on many levels (likely simultaneously); (c) increase the likelihood of encountering additional adverse experiences and secondary stressors (as posited by cumulative effects theories); and consequently, (d) increase the probability of maladaptation over time (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, Reference Ben-Shlomo and Kuh2002; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Giles, Felitti, Dube, Williams, Chapman and Anda2004; Nurius et al., Reference Nurius, Green, Logan-Greene and Borja2015).

Poverty and ACEs

The implications of the larger systemic forces mentioned in point (a) above remain under-studied within the ACE literature, and a more accurate Figure 1 might depict the two foundational layers as a separate, overlapping pyramid, illustrating how context suffuses all aspects of ACE experiences. This perspective, in addition to research suggesting that deprivation relating to poverty can have neurological effects that are similar to those found with abuse and neglect (Dennison et al., Reference Dennison, Rosen, Sambrook, Jenness, Sheridan and McLaughlin2019; Luby, Belden, & Botteron, Reference Luby, Belden, Botteron, Marrus, Harms, Babb and Barch2013) has led to a call for expansion of ACE measures to include experiences of adversity that are more prevalent in poverty (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2013; Karatekin & Hill, Reference Karatekin and Hill2019; Wade et al., Reference Wade, Cronholm, Fein, Forke, Davis, Harkins-Schwarz and Bair-Merritt2016).

Research has long indicated that there is a complex interplay between poverty and adversity. Children living in poverty are more likely to be exposed to some types of ACEs than are their wealthier peers (Bradley & Corwyn, Reference Bradley and Corwyn2002; Cronholm et al., Reference Cronholm, Forke, Wade, Bair-Merritt, Davis, Harkins-Schwarz and Fein2015; Evans, Vermeylen, Barash, Lefkowitz, & Hutt, Reference Evans, Vermeylen, Barash, Lefkowitz and Hutt2009; Halonen et al., Reference Halonen, Vahtera, Kivimäki, Pentti, Kawachi and Subramanian2014; Parker, Greer, & Zuckerman, Reference Parker, Greer and Zuckerman1988; Rabkin & Struening, Reference Rabkin and Struening1976; Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, Reference Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen2009). The effects of ACEs can also be amplified in contexts of poverty and, reciprocally, ACEs can amplify the effects of the neighborhood disadvantage that often accompanies low-income status (Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey, & Rose, Reference Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey and Rose2018; Odgers & Jaffee, Reference Odgers and Jaffee2013; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Greer and Zuckerman1988; Wang & Maguire-Jack, Reference Wang and Maguire-Jack2018; Williams & Jackson, Reference Williams and Jackson2005). Bradley and Corwyn (Reference Bradley and Corwyn2002) hypothesized that both intrinsic factors (e.g., neurobiological alterations, diminished self-efficacy) and extrinsic factors (e.g., limited access to basic necessities, lower quality parenting due to diminished resources) interact to amplify the effects of stress in contexts of poverty. Extrinsic factors may act as additional ACEs and diminish children's ability to combat intrinsic risk factors; however, this framing is also heartening in that extrinsic risk factors in particular are often malleable and responsive to intervention (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007; Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2011).

Notably, the large-scale ACE studies did not assess for experiences that are more common in low-income or marginalized communities, and they focused exclusively on in-home and within-family experiences. This is limiting from a transactional-ecological perspective, as poverty is a diffuse construct that permeates both psychosocial and environmental aspects of life. Children, in high-poverty contexts or otherwise, do not exist inside a vacuum of family life, and it is important to recognize that adversity experienced in the community context can influence functioning commensurate with adversity experienced in the home. As such, if researchers do not measure broader contextual experiences, particularly those that are specific to an impoverished environment, they may be missing or masking the effects of influential adverse experiences (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Sealand, Reference Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov and Sealand1993). An “Expanded ACE” framework with community-level indicators and indicators of experiences associated with socioeconomic status (e.g., community violence, foster care, Giovanelli et al., Reference Giovanelli, Reynolds, Mondi and Ou2016; Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2013; difficulty affording basic necessities, Koita et al., Reference Koita, Long, Hessler, Benson, Daley and Bucci2018) is necessary to illuminate potential consequences, mechanisms, and moderators of ACEs for individuals in high-risk settings.

When poverty is used as an item-level measure of psychosocial adversity in research design, it is often operationalized as family income or occupational prestige (Danese et al., Reference Danese, Moffitt, Pariante, Ambler, Poulton and Caspi2008; Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2013). However, the nature of a child's experience can vary widely even between households or neighborhoods of the same socioeconomic strata or social class (Berens et al., Reference Berens, Jensen and Nelson2017; Galster, Reference Galster, von Ham, Manley, Bailey, Simpson and Maclennan2012). More explicit hardships associated with lower socioeconomic status (e.g., difficulty affording food, clothing, medical care, or housing; low neighborhood safety; discrimination), as well as the individual's subjective awareness of family financial struggles, more clearly operationalize stress on both the child and the family unit. Measuring expanded ACEs as we have done herein can both specify the effects of poverty-related adversity in a more nuanced way and illuminate mechanisms of transmission of ACE effects for diverse populations.

Mechanisms and Intervention

While research examining how neurobiological processes resulting from ACEs can shape brain development and behavior has pointed to some factors that may confer resilience, this information has only recently begun to be used to inform interventions (e.g., McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019), and thus far has relatively limited utility for large-scale preventive efforts. As such, there remains a particular need for studies that will identify mediators that could feasibly be targeted via universal social and behavioral interventions.

Early Childhood Education Programs

Early childhood education (ECE) programs are one potential avenue for promoting healthy development among ACE-affected individuals (Copeland-Linder, Lambert, Chen, & Ialongo, Reference Copeland-Linder, Lambert, Chen and Ialongo2011; Reynolds, Tample, Ou, Arteaga, & White, Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga and White2011; Sciaraffa, Zeanah, & Zeanah, Reference Sciaraffa, Zeanah and Zeanah2018; Shonkoff et al., Reference Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen2009). Early childhood education programs provide an array of intervention services from preschool through third grade, including educational interventions for children and services that are directed at enhancing parent involvement and broader family well-being.

Longitudinal research has indicated that high-quality ECE programs yield significant financial returns to society by promoting participants’ multidimensional well-being including higher rates of educational attainment, economic productivity, and health insurance coverage and reduced rates of incarceration, welfare use, and mental illness (Belfield, Nores, Barnett, & Schweinhart, Reference Belfield, Nores, Barnett and Schweinhart2006; Reynolds, Temple, Ou, et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga and White2011). Notably, program participation typically yields the greatest returns on investment for children with the most significant psychosocial risk at program entry (Karoly & Bigelow, Reference Karoly and Bigelow2005; Schweinhart et al., Reference Schweinhart, Montie, Xiang, Barnett, Belfield and Nores2005). For example, research indicates that the Child–Parent Center (CPC) ECE program exerts the strongest benefits for children at the highest levels of sociodemographic risk (e.g., children in the highest-poverty neighborhoods, those whose parents are high school dropouts, and males; Giovanelli, Reference Giovanelli2018; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Robertson, Mersky, Topitzes and Niles2007; Reynolds, Temple, Ou, et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga and White2011).

A growing body of research has also indicated that ECE programs can attenuate the short- and long-term repercussions of life stress and adversity (Giovanelli, Reference Giovanelli2018; Karoly, Kilburn, & Cannon, Reference Karoly, Kilburn and Cannon2006; Reynolds, Tample, Ou, et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga and White2011; Schweinhart et al., Reference Schweinhart, Montie, Xiang, Barnett, Belfield and Nores2005; Temple & Reynolds, Reference Temple and Reynolds2007), although relatively little research has examined the mechanisms through which such universal programs can build youth resilience to ACEs specifically (Chandler et al., Reference Chandler, Roberts and Chiodo2015; Larkin, Felitti, & Anda, Reference Larkin, Felitti and Anda2013). Existing evidence suggests that further such investigations are warranted, as mechanisms similar to those that lead to improved outcomes in underserved communities may be at play in the face of ACEs. For example, some ECE programs have been linked to lower rates of maltreatment as well as mitigation of the effects of prior maltreatment (Temple & Reynolds, Reference Temple and Reynolds2007; Karoly et al., Reference Karoly, Kilburn and Cannon2006). Several potential mediators have been explored to explain intervention effects on well-being, particularly in the domains of family involvement and school quality (Matthews & Gallo, Reference Matthews and Gallo2011; Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2004; Singh-Manoux et al., Reference Singh-Manoux, Ferrie, Chandola and Marmot2004).

Longitudinal research on the CPC program has investigated the explanatory power of five CPC-related factors on program effects (The 5 Hypothesis Model; 5HM): (a) Cognitive Advantage; (b) Family Support; (c) School Support; (d) Motivational Advantage; and (e) Social Adjustment (e.g., Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2000; Reynolds, Ou, Mondi, & Hayakawa, Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Hayakawa2017; see Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2011 for a more complete explication of the history and validation of this model in the present sample). The 5HM views cumulative advantage theory through a developmental ecological lens, hypothesizing that early educational enrichment can lead to increased competencies at many levels of the child's ecological system (e.g., increased family support, school support, cognitive abilities, motivation, and social adjustment). These competencies are thought to accumulate and to positively affect well-being across domains. Findings have suggested that cognitive advantage, school support, and family support make the greatest contributions to educational attainment, with some sex differences (Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2010; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Hayakawa2017). Other developmental studies have also linked these factors to a wide range of developmental outcomes, and scholars suggest that early childhood programs that provide cognitive, social, and linguistic enrichment can enhance developmental trajectories (Conger & Donnellan, Reference Conger and Donnellan2007; Hackman et al., Reference Hackman, Gallop, Evans and Farah2015; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Nelson2017). Given that the 5HM is based in an enrichment and adversity perspective, and in light of longstanding convergent research pointing to resilience to adversity specifically via social and cognitive capacities, family support, and external (e.g., school and community) support (Garmezy, Reference Garmezy and Stevenson1985; Luby et al., Reference Luby, Belden, Botteron, Marrus, Harms, Babb and Barch2013; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007), we hypothesized that variables that have been shown to explain how CPC influences well-being by providing enrichment and reducing adversity may also explain how ACEs transmit effects over time (see Figure 2 for an illustration of the pathways through which ACEs are hypothesized to influence well-being in adulthood within this framework). Until now, the robustness of these mediational patterns in this sample has only been assessed by CPC attendance, not by levels of ACE exposure. Generalizing this model may both shed further light on the developmental origins of multidimensional well-being and illuminate the psychosocial processes of ACE exposure and adaptation.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework of mediation model. ITBS, Iowa Test of Basic Skills. MA, motivational advantage hypothesis. CA, cognitive advantage hypothesis. SA, social adjustment hypothesis. FS, family support hypothesis. SS, school support hypothesis.

The Present Study

The present study seeks to address gaps in knowledge on the mechanisms of risk and resilience in ACE-affected individuals, with a particular focus on mechanisms that have direct relevance to prevention and intervention efforts. The research questions will be examined in a sample of low-income adults who have been studied since early childhood. We posited three hypotheses: (a) cumulative ACEs from birth to 18 years will predict adverse outcomes in the domains of educational attainment, occupational prestige, criminal justice system involvement, and smoking in early adulthood. As the brain is uniquely sensitive to experience in early childhood (Gunnar & Quevedo, Reference Gunnar and Quevedo2007), we also hypothesized that ACEs from birth to age five years will be uniquely influential on early adult outcomes; (b) associations between ACEs and outcomes will be strongest for males and for participants in the highest poverty neighborhoods; and (c) the 5HM mediators will partially to substantially explain the direct associations between ACEs and outcomes.

Method

Sample and Design

Data was drawn from the Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS), which has prospectively tracked a cohort of 1,539 individuals since they attended kindergarten in low-income Chicago neighborhoods in 1985. The original CLS sample was evenly split by sex and representative of participants’ neighborhood demographics (92.9% African American and 7.1% Hispanic).

Data have been collected from early childhood through adulthood via participant, parent, and teacher surveys as well as through school and government records. The original and present study samples were comparable on key demographic characteristics, although there was a slightly higher proportion of females in the current sample than in the original sample (see Table 1), and sex was included as a covariate for the full sample analyses. Of the original sample, 74.2% of participants (n = 1,142) completed a follow-up survey at age 22–24, and 71.8% (n = 1,107) completed a follow-up survey at age 35–37.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and prevalence, CLS sample

Note: †Participants were designated “high risk” if they had four or more of eight family and sociodemographic risk indicators prior to age 3. *p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Participants reported on age 0–18 ACEs during both follow-up surveys. The present study solely used ACE data from the age 22–24 survey for most participants (n = 1,010). This decision was intended to reduce elapsed time between ACE occurrences and reporting. Age 35–37 data was only used for two subgroups of participants (n = 331): (a) participants who did not complete the age 22–24 survey but who did complete the age 35–37 survey and (b) participants who completed both surveys and provided new information about ACEs during the age 35–37 survey. Incorporating this information did not significantly alter the results, and it yielded a total sample size of 1,341 for ACE analyses, with an overall attrition rate of just 12.9%. The sample sizes varied by outcome in the individual analyses (see Table 1); however, all members of the study sample had valid data for at least one outcome measure.

Measures

Predictors

ACEs

Information about ACEs was drawn from participant surveys as well as court and county records. During the age 22–24 survey, participants completed a checklist of ACEs that was comparable to that of the original ACE Study checklist (e.g., Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004), which also included additional adverse experiences that are common among children living in urban poverty (e.g., Bell & Jenkins, Reference Bell and Jenkins1993; Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, Reference Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz and Simons1994; Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2013; Karatekin, Canan, & Hill, Reference Karatekin and Hill2019). Participants reported whether they had experienced each of nine ACEs, and if so, their age bracket at the time (zero to five, six to ten, ten to fifteen, or sixteen and older). The self-reported ACE categories were: (a) prolonged absence or divorce of parents, (b) death of a parent, (c) death of a sibling, (d) death of a close friend, (e) family financial problems, (f) frequent family conflict, (g) parental substance abuse, (h) witnessing a violent crime, and (i) being a victim of a violent crime. Due to the age categories provided, the self-reported ACEs were only counted up to age fifteen. Five additional ACEs were assessed by inspecting court and county records from the Department of Child and Family Services, and these spanned the period from birth through age eighteen: (a) child welfare reports (abuse or neglect) from birth through age three; (b) physical abuse; (c) sexual abuse; (d) neglect from age four to up to age eighteen; and (e) foster care or out of home placement from birth to age eighteen. Each of the fourteen ACEs was scored for presence (1) or absence (0), and these scores were summed to yield a continuous ACE score. Scores were then polychotomized, consistent with conventions in the field, to indicate the number of ACEs experienced during two different time periods: (a) zero, one, or ≥2 between birth and age five (“early ACEs”) and (b) zero, one, two, three, or ≥4 between birth and age 18.

Outcomes

High school graduation

Information about high school graduation was drawn from school records and supplemented with self-report. Participants who graduated from high school by age 25 were coded as 1, all others were coded as 0.

Juvenile arrest by age 18

Record searches were conducted at the Cook County Juvenile Court and two other Midwest locations for formal petitions regarding criminal charges by 18 for participants who resided in Chicago at age ten or older. Searches were conducted blind to intervention status, repeated twice for 5% random samples, and cross-checked against computer records. Individuals arrested as juveniles were coded as 1; all others were coded as 0.

Felony charge (ages 18–24 years)

Information about felony (e.g., battery, arson, sexual assault, possession of narcotics) charges between 18 and 24 years were drawn from federal prison, state, county, and circuit court records.

Smoking

Information about smoking behavior was drawn from self-reports on the age 22–24 survey. Participants who reported that they were currently smoking cigarettes daily were coded as 1, and all others were coded as 0.

Occupational prestige

Participants reported information about their most recent jobs on the age 22–24 survey. The skill level of the current and/or two most recent jobs reported were coded according to the Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (Barratt, Reference Barratt2006); 1 = low levels of job skill or education classification; “5” = moderate levels of job skill or postsecondary training; and “9” = high levels of job skill requiring an advanced degree). Missing data were imputed using education and income data. A dichotomized variable indicating a semiskilled or higher level of occupational prestige (≥4) was used in present analyses.

Covariates

Information on covariates was primarily drawn from school records.

Child–Parent Center (CPC) intervention

The CPC intervention is the second-oldest federally funded preschool program after Head Start, and the oldest extended early intervention in the United States. The CPC intervention provides comprehensive, center-based educational and family support services to low-income children between preschool and third grade. The CPC intervention is designed to enhance academic success, well-being, and parent involvement (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2000).

Preschool intervention

Participants who attended the CPC preschool program for one or two years were coded as 1, and all others were coded as 0.

School-age intervention

Participants who attended the CPC program between grades 1 and 3 only were coded as 1, and all others were coded as 0.

Sex

Males were coded as 0, and females were coded as 1.

Race/ethnicity

African American participants were coded as 1, and Hispanic participants were coded as 0.

Family risk index

Information about common sociodemographic risk factors was drawn from parent and participant surveys, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Chicago Public School Student Information System, and the Illinois Public Assistance Research database. Eight risk factors were coded for presence (1) or absence (0) by age three: (a) mother was under age 18 at the participant's birth, (b) mother did not complete high school, (c) mother was unemployed or employed part-time, (d) participant lived in a single-parent household, (e) participant lived in a household of four or more children, (f) participant lived in a school attendance area where ≥ 60% of households were impoverished, (g) participant was eligible for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) based on family income, and (h) participant was eligible for free lunch. A sociodemographic risk index was constructed by summing participants’ scores for each indicator. Approximately 10% of cases with missing data were imputed with the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm in LISREL (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997).

Mediators

Cognitive advantage hypothesis

Early childhood cognitive skill

Participants completed the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS Level 5; Hieronymus, Lindquist, & Hoover, Reference Hieronymus, Lindquist and Hoover1982) in October of their kindergarten year. The ITBS includes assessments of early vocabulary and mathematical knowledge. The internal consistency reliability of the ITBS has been reported at .94 (Hieronymus et al., Reference Hieronymus, Lindquist and Hoover1982). Data was missing for approximately 25% of the sample and was imputed using the EM algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997). Composite standard scores were analyzed in the present study.

Third grade reading achievement

Participants completed the Iowa Test of Basic Skills battery (ITBS; Level 8 or 9; Hoover & Hieronymous, Reference Hoover and Hieronymus1990) in the spring of third grade. The reliability of this scale exceeded 0.90. Data was missing for approximately 10% of cases. These scores were imputed using prior ITBS scores or, if those scores were also missing, using the EM algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997). The reading comprehension subtest was used in the present study.

Retention between kindergarten and eighth grade

Information about grade retention was drawn from school administrative records. A dichotomized variable was created to indicate whether participants had ever been retained between kindergarten and eighth grade. A small number of cases were imputed using the EM algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997).

Eighth grade reading achievement

Participants completed the Iowa Test of Basic Skills battery (ITBS; Level 13 or 14; Hoover & Hieronymous, Reference Hoover and Hieronymus1990) in April of eighth grade. The reliability of this scale has been reported at .92. Approximately 10% of cases had missing data and were imputed using prior ITBS scores or, if those scores were also missing, with the EM algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997). The present study analyzed the reading comprehension subtest.

Family support

Parent expectations in early elementary school

Parents completed surveys when participants were in second and fourth grade. On both surveys, they indicated how far they expected their children would go in school on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (8th grade) to 7 (graduate degree). These responses were recoded into years of education. Missing values (20% of the sample) were imputed with 14 years (high school completion). If data were available from the fourth-grade survey, this was used; if not, data from the second-grade survey was used. If data were not available from either the survey, data from an 11th-grade parent survey was used.

Parent involvement in school (Grades 1–3)

Information about parent involvement in school activities in grades 1 through 3 was drawn from teacher reports. Each year, teachers rated parent participation in school activities (e.g., parent communicates with school regularly; parent picks up report cards) on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (poor/not at all) to 5 (excellent/much). The final measure was created by computing the mean teacher ratings of parent involvement across grades 1–3.

School support

Magnet school attendance (Grades 4–8)

Information about magnet school attendance was drawn from school records. Participants who attended magnet schools, which had selective enrollment policies, between grades 4 and 8 were coded as 1; all others were coded as 0.

School mobility (Grades 4–8)

This continuous variable, drawn from school administrative records, indicates the number of times participants changed schools from fourth through eighth grade.

Motivational advantage

School commitment (Grades 5–6)

Participants’ school commitment was assessed via self-report in grades 5 and 6. Over the two years, participants indicated how much they agreed with 32 items regarding their feelings about school (e.g., “I like school”) and their attitudes and behaviors around school-related activities (e.g., “I give up when schoolwork gets hard”) on four- to five-point Likert scales. This variable is the mean of each participant's school commitment scores across both grades. Reliability for these measures was good (α = .71 and .73, respectively).

Student expectations of college attendance

Participants’ expectations for their educational attainment were assessed via self-report in fourth grade. Participants indicated how far they thought they would go in school on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (8th grade) to 4 (college attendance). Data were dichotomized to indicate whether participants expected to attend college. If the fourth-grade report was not available, data were drawn from a nearly identical item on a tenth-grade survey.

Social adjustment

Socio-emotional adjustment in the classroom (Grades 1–3)

Each participant's socioemotional adjustment in the classroom was assessed in early elementary school. In first grade, teachers rated participants on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (poor/not at all) to 5 (excellent/very much) on six items (e.g., “complies with classroom rules,” “displays confidence in approaching learning tasks”). In second and third grades, teachers again rated participants on the same 5-point Likert scale, with slightly different questions measuring the same construct. Participant's ratings were averaged across grades. Approximately 5% of the sample was missing data due to teacher nonresponse. These scores were imputed using the EM algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997). The scales from first to third grades demonstrated reliabilities of .92, .93, and .91, respectively.

Task orientation

Each participant's task orientation in sixth and seventh grades was assessed using items from the Teacher-Child Rating Scale (T-CRS; Hightower, Reference Hightower1986). Teachers rated how much of a problem five behaviors were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not a problem) to 5 (very serious problem) in response to items such as “completes work,” “works well without supervision”). Approximately one third of the cases were missing data in both grades, and these scores were imputed using the EM algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997).

Frustration tolerance

Each participant's frustration tolerance in grades 6 and 7 was assessed using items from the T-CRS (Hightower, Reference Hightower1986). Teachers rated how well participants demonstrated attributes of social and emotional maturity on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very well) for five items (e.g., “accepts things not going his/her way,” “accepts imposed limits,” “copes well with failure”). The internal reliabilities of the sixth- and seventh-grade subscales were .92 and .91, respectively. For participants with data for both grades, these subscales were averaged to create a single frustration tolerance score. For participants with data for only one grade, that score was used. As with task orientation, approximately one-third of cases were missing data in both grades, and these scores were imputed using the EM algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using STATA (Version 14.0, StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Probit regressions with marginal effects were run to determine relations between ACE counts and outcome variables. Four dichotomous ACE frequency indicators were included in the model (1, 2, 3, and ≥4), with zero ACEs as the reference group. To examine the early childhood period, relations between ACEs and outcomes were estimated separately for ACEs experienced from birth through age 5. Given the shorter time period, two dichotomous ACE frequency indicators were used (1 and ≥2), with zero ACEs as the reference group. Sex, race, CPC preschool and school-age participation, and risk index were entered as covariates.

For moderation analyses, participants were run separately by sex and by neighborhood income level. Mediators from the 5HM Model (Social Support, School Support, Motivation, Family Support, and Cognitive Advantage) were entered into the full and subsample models separately by category as well as simultaneously to determine whether these factors explained some of the adverse effects of ACEs on well-being in adulthood. Bivariate correlations among mediators were explored prior to analyses to discern the degree of associations and to assess for collinearity (Table 6). The majority of the mediators were moderately correlated, though it is known that significant p-values are more likely in large data sets. No correlations were ≥ .70, which is a conventional cutoff for collinearity and classification as “highly correlated” (Büh & Zöfel, Reference Bühl and Zöfel2002; Vittinghoff, Glidden, Shiboski, & McCulloch, Reference Vittinghoff, Glidden, Shiboski and McCulloch2012). Emerging adulthood variables, juvenile arrest and high school graduation status, were then entered as additional mediators to determine potential contributions of later life experiences.

The difference-in-difference (percent reduction) approach was used to assess mediation (MacKinnon, Reference MacKinnon2008). Given the scope of the model and number of mediators, the alternative strategy of goodness-of-fit via maximum likelihood estimation of alternative structural models was not feasible. The percent reduction approach is most recommended in confirmatory models with a few key constructs (Joreskog & Sorbom, Reference Joreskog and Sorbom2005). In this approach, two sets of models are estimated. The first assesses whether a significant main effect is detected between ACEs and the outcome. If a main effect is identified, the second set of models assesses the percentage of this main effect that is associated with (explained by) the hypothesized mediator(s). The difference between the coefficient in the main effects model and the mediator model is summarized as the percentage of the main effect coefficient explained by the mediators.

We estimated the percentage reduction in main effects separately for each hypothesis and in combination to determine the relative contribution of each hypothesized mediator to the main effect of ACEs. Mediation can be absent, partial, or full. Partial mediation is defined as a 20–40% reduction in the main effect that typically does not lead to a change in the statistical significance of the main effect (MacKinnon, Reference MacKinnon2008). Full mediation is defined as a reduction in the main effect that results in a nonsignificant difference in hypothesized effects after the mediator is added to the model. In cases of full mediation, approximately half to nearly all of the main effect is explained by the mediator(s). Like all modeling approaches to mediation, mediation is a correlational approach and causation should not be inferred. To the extent that the model accounts for the main effect and contributes unique variance to outcomes, the inference that the mediators are important contributors to the hypothesized relations is strengthened.

Results

As previously discussed, the first hypothesis was that cumulative ACEs would predict adverse outcomes in adulthood. The second hypothesis was that the effects of ACEs would differ by sex and school neighborhood poverty level. The third hypothesis was that the 5HM mediators would explain the relationships between ACEs and outcomes.

The relationships were examined in the full sample and in subsamples by sex and poverty level for each hypothesis. The results will be presented as follows: (a) prevalence rates of ACEs occurring between ages 0–18 and 0–5, respectively; (b) associations and mediational pathways among ACEs, educational attainment, and occupational prestige, including subgroup analyses and examinations of age 0–18 and 0–5 ACEs; (c) associations and mediational pathways among ACEs and smoking, including subgroup analyses and examinations of age 0–18 and 0–5 ACEs; and (d) associations and mediational pathways among ACEs and criminal justice system involvement, including subgroup analyses and examinations of age 0–18 and 0–5 ACEs. Due to the large volume of results, the focus is on select findings in the highest ACE groups (3- and ≥4-ACE). Full results are available in Supplementary Tables 1–18. Additionally, select effects of the School Support mediator alone are presented in Figure 6.

ACE Prevalence Rates

All ACEs (0–18 years)

The ACE prevalence rates for this sample are shown in Table 1. In this sample, 70.1% of the participants (n = 940) reported experiencing at least one ACE by age 18; 22.60% of the sample reported experiencing one ACE; 15.14% reported experiencing two ACEs; 13.72% reported experiencing three ACEs; and 18.64% of the sample reported experiencing four or more ACEs. From birth through age 5, 32.5% of the sample reported experiencing at least one ACE. The most commonly experienced ACEs across childhood and adolescence were prolonged absence of a parent or divorce of parents (43.62% of the sample), followed by parent substance abuse (31.44%), death of a close friend (30.45%), family financial problems (28.69%), frequent family conflict (24.61%), and witnessing a violent crime (21.73%).

Among the subgroups, participants with four or more demographic risk factors were more likely to endorse having experienced at least one ACE, χ2 = 12.34, p < .001; see Table 1, and more likely to have a substantiated report of neglect, χ2 = 5.36, p < .05. Overall, males were more likely to report the death of a close friend, χ2 = 11.05, p < .001, more likely to have witnessed and to have been victims of violent crime, χ2 = 82.49, p < .000; χ2 = 15.49, p < .000, and more likely to report having experienced four or more ACEs by age 18, χ2 = 15.25, p < .001, whereas females were more likely to have a documented history of sexual abuse, χ2 = 10.65, p < .001. The CPC intervention participants were also less likely to have a report of neglect or to have been in out-of-home placement (e.g., foster care) than comparison group participants were, χ2 = 17.87, p < .001; χ2 = 6.90, p <.01.

Early ACEs (0–5 years)

Given the evidence for early childhood as a uniquely sensitive period, ACE counts occurring only from birth to age 5 were examined separately. As this is a shorter period, the participants were placed in zero-, one-, or ≥2-ACE groups.

For early childhood ACEs, 18.27% of the sample reported having experienced one early ACE and 14.24% reported having experienced two or more. There were no significant differences in prevalence rates by sex, but the higher demographic risk group was significantly more likely to have had at least one ACE, χ2 = 7.77, p < .01. See Table 1 for further detail.

Associations among ACEs and Adult Outcomes

Educational attainment and occupational prestige

Associations with cumulative ACEs (0–18 years)

Consistent with the convention in ACE research and grounded in cumulative effects theory, the present study examined ACEs cumulatively, rather than individually. When analyses were conducted using individual ACEs, many ACEs significantly predicted adult outcomes, but associations between ACEs and outcomes were not primarily driven by any one type of ACE.

Full sample (Table 2, Figure 3)

Participants in the 3- and ≥4-ACE groups were significantly less likely to obtain a high school diploma by age 25. For occupational prestige, only the 2-ACE group was less likely to have a higher-skill job.

Table 2. Direct effects for full sample and by sex, ACEs 0–18

Note: Reference group = 0 ACEs; *p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 3. Associations between ACEs and outcomes Zero ACEs is reference group. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

By sex (Table 2)

Males in the 2-, 3-, and ≥4-ACE groups were significantly less likely to graduate from high school than the reference group. For females, only an ACE score of ≥4 ACEs was associated with reduced likelihood of high school graduation.

By school neighborhood poverty level (Table 3)

For participants living in higher poverty areas, the 3- and ≥4-ACE groups were significantly less likely to graduate from high school than the reference group. For lower poverty participants, only participants in the ≥4-ACE group were less likely to graduate from high school.

Table 3. Direct and mediation effects by school neighborhood poverty, ACEs 0–18

Note: Reference group = 0 ACEs; *p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

For higher poverty participants, there was an association between the 3- and ≥4-ACE group and less-skilled jobs, whereas for lower poverty participants, ACEs and occupational prestige were not associated.

Mediational pathways (Table 3, Supplementary Tables 1–5)

School support mediators reduced the effects of ACEs on high school graduation for participants in the ≥4-ACE group across all subgroups, with percent reductions ranging from 2.5% to 17.8%. In the higher poverty group, School Support also reduced the association between ≥4 ACEs and occupational prestige by 15.4%.

All 5HM mediators, plus late adolescent well-being (Supplementary Tables 6–10)

All 5HM mediators, plus juvenile arrest and high school graduation status, were entered into the models to determine if these variables contributed to increased explanation of ACE effects. Among the higher poverty group, the seven mediators attenuated the association between ACEs and occupational prestige by 21.7% for the 3-ACE group and by nearly half (47.3%) for the ≥4-ACE group.

Associations with cumulative early ACEs (0–5 years)

Full sample (Table 4, Figure 3)

For high school graduation, the 1-ACE group was less likely to graduate from high school than the reference group.

Table 4. Direct effects for full sample and by sex, ACES 0–5

Note: Reference group = 0 ACEs; *p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

By sex (Table 4)

ACEs were associated with decreased chances of graduating high school for males in the ≥2-ACE group and for females in the 1-ACE group.

By school neighborhood poverty level (Table 5, Figure 4)

For higher poverty participants, the 1- and ≥2-ACE groups were significantly less likely to graduate from high school, whereas educational attainment and early ACEs were unrelated in the lower poverty group.

Table 5. Select effects by school neighborhood poverty, ACEs 0–5

Note: Reference group = 0 ACEs; *p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 6. Bivariate correlations among mediators

Note: All correlations were significant at p < .05 or below.

Figure 4. Associations between early childhood ACEs and outcomes by neighborhood poverty. Zero ACEs is reference group.

Mediational pathways (Supplementary Tables 12–14)

In the full sample, School Support accounted for 12.2% of the association between ACEs and high school graduation for the 1-ACE group. For males in the ≥2-ACE group, the Motivation mediator reduced the association between ACEs and high school graduation by 15.3% (see Figure 5), whereas the School Support mediator reduced this association by 14.8% for females in the 1-ACE group. Several different mediators attenuated the relation between ACEs and educational attainment in the higher poverty subgroup, with Motivational Advantage, Family Support, and School Support percent reductions ranging from 7.3–14.6%. There were no direct effects of ACEs on outcomes when the lower poverty subgroup was examined alone.

Figure 5. Effects of motivational advantage mediator: Males with high ACEs in early childhood. Zero ACEs is reference group. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

All 5HM mediators

There were no mediating effects on education or occupational prestige when all 5HM mediators and all 5HM mediators plus the two indicators of late-adolescent well-being were entered into the model.

Smoking

Associations with cumulative ACEs (0–18 years)

Full sample (Table 2, Figure 3)

The 2-, 3-, and ≥4-ACE groups were significantly more likely to smoke.

By sex (Table 2)

For males, participants in the 3- and ≥4-ACE groups were significantly more likely to be smokers at age 24. For females, only membership in the ≥4-ACE group was associated with smoking in early adulthood.

By school neighborhood poverty level (Table 3)

Higher poverty participants in the 3- and ≥4-ACE groups were significantly more likely to be smokers at age 24, whereas the smoking status of the lower poverty participants was only significantly related to ACE scores of ≥4.

Mediational pathways

The addition of mediators to the model had small but significant effects on the association between ACEs and smoking. School Support mediators attenuated the effects of ≥4 ACEs and smoking by 8.7% in the full sample and 5.8% in males.

All 5HM mediators, plus late-adolescent well-being

Juvenile arrest and high school graduation status were entered into the models along with the 5HM mediators to determine whether these variables contributed to increased explanation of ACE effects. For the full sample, the addition of all seven mediators to the model reduced the association between 2 and ≥4 ACEs and smoking by 12.6% and 29.5%, respectively. In males, the seven mediators accounted for 21.4% of the association between ≥4 ACEs and smoking. In females, mediation effects from the seven mediators were less pronounced, with a 17.4% percent reduction in the association between ≥4 ACEs and the smoking outcome. The strongest mediation effects were seen in the higher poverty group. In this group, the seven mediators attenuated the association between 3 and ≥4 ACEs and smoking, with percent reductions of 23.6% and 42.9%, respectively.

Supplementary Table 10 shows a comparison of select direct and mediation effects in this study and Giovanelli et al., Reference Giovanelli, Reynolds, Mondi and Ou2016, which highlighted a preliminary investigation of the association between ACEs and outcomes in this population. Results show that the model in the present study accounted for more of the main effect of the ≥4-ACE group for health compromising behavior/smoking (29.5% vs. 0%). The main effect for the 3-ACE group is much greater in the present study, which may explain why the mediators did not account for as much of this effect.

Associations with cumulative early ACEs (0–5 years)

By sex (Table 4)

Males in the 2-ACE group were significantly more likely to be smokers at age 24, but early childhood ACEs were significantly associated with smoking status only for females in the 1-ACE group.

By school neighborhood poverty level (Table 5)

Higher poverty participants in both the 1- and ≥2-ACE groups were significantly more likely to be smokers by age 24. ACE scores had no effect on reported smoking habits in lower poverty participants.

Mediational pathways (full results in Supplementary Tables 12–14)

The Motivational Advantage mediator reduced the association between the 1-ACE group and smoking in the full sample by 13.7%. This same mediator attenuated the relation in the ≥2-ACE group and smoking in males by 12% (see Figure 5). For females, School Support mediated the effects of ACEs on smoking in the 1-ACE group (16.5%). In the higher poverty subgroup, the addition of each set of mediators led to small percent-reductions between ACEs and smoking across groups. For example, the Motivational Advantage mediator reduced the association between ACEs and smoking by 8.3% in the 1-ACE group and 10.4% in the ≥2-ACE group. There were no direct effects of ACEs on outcomes when the lower poverty subgroup was examined alone.

All 5HM mediators, plus late adolescent well-being

When the 5HM mediators were entered into the early childhood model along with juvenile arrest and high school graduation, the seven mediators reduced the associations between ACEs and smoking by 13.4% for females in the 1-ACE group. For higher poverty participants, the association between smoking and ACES was reduced by 19.2% for the 1-ACE group and 5.2% for the ≥2-ACE group.

Criminal justice system involvement

Associations with cumulative ACEs (0–18 years)

Full sample (Table 2, Figure 3)

The ≥4-ACE group was significantly more likely to be arrested prior to age 18 and to be charged with a felony by age 24.

By sex (Table 2)

For both sexes, members of the ≥4-ACE group were significantly more likely to be arrested before age 18. Males in the ≥4-ACE group were also more likely to be charged with a felony by age 24, while females in the 1-ACE group were, unexpectedly, significantly less likely to be charged with a felony than the reference group with zero ACEs. However, as just 4.22% of females in this sample (with eight in the 0-ACE group versus one in the 1-ACE group) had a felony charge, this result should be interpreted very cautiously.

By school neighborhood poverty level (Table 3)

Higher poverty participants in the ≥4-ACE groups were significantly more likely to have been arrested by age 18 and to have an adult felony charge. For lower poverty participants, the ≥4-ACE group was more likely to be arrested by age 18, and there was no association between ACEs and felony charge.

Mediational pathways

School support mediators accounted for 12% of the association between ≥4 ACEs and felony charge in the full sample and 6.2% of this association in males. This same group of mediators attenuated the association between ≥4 ACEs and juvenile arrest by 12.6% in the full sample, 14.9% in males, and 15% in the lower poverty subgroup.

All 5HM mediators, plus late adolescent well-being

Adding all 5HM mediators into the model simultaneously evinced small to medium effects on the juvenile arrest outcome (See Table 5 and Supplementary Tables 6–9). The 5HM mediators partially mediated the associations between ≥4 ACEs and juvenile arrest in the full sample, the female sample, and the higher poverty sample (14.7, 16.2, and 21.4%, respectively).

Associations with cumulative early ACEs (0–5 years)

Full sample (Table 4, Figure 3)

The ≥2-ACE group was significantly more likely to have been charged with a felony by age 24.

By sex (Table 4)

For both males and females, participants in the ≥2-ACE group were significantly more likely to have a felony charge in adulthood than the reference group with zero ACEs, while ACEs were not associated with juvenile arrest.

By school neighborhood poverty level (Table 5)

For higher poverty participants, the ≥2-ACE group was significantly more likely to have a felony charge by age 24. ACEs were not associated with criminal justice system involvement in the lower poverty subgroup.

Mediational pathways (full results in Supplementary Tables 12–14)

In the full sample, School Support, Motivational Advantage, and Family Support all partially mediated the association between ACEs and felony charge in the ≥2-ACE group, with percent reductions ranging from 3.9% to 6.9%. These same mediators reduced the association between ACEs and felony charge in the higher poverty group by 5.4, 9.3, and 4.7%, respectively. For males in the ≥2-ACE group, the Motivation and Family Support mediators reduced the association between ACEs and felony charge by 15.5% (see Figure 5) and 8.6%, respectively. For females, mediation effects were present but smaller, with percent reductions of 6.1% from both the School Support and Family Support mediators. There were no direct effects of ACEs on outcomes when the lower poverty subgroup was examined alone.

All 5HM mediators, plus late-adolescent well-being (Supplementary Tables 14–17)

When the 5HM mediators, along with juvenile arrest and high school graduation, were entered into the early childhood model simultaneously, the association between ≥2 ACEs and felony charge was reduced by 19.6% in the full sample and 25.9% for males. For higher poverty participants, the association between ACEs and felony charge was reduced by 20.2% in the ≥2-ACE group.

Discussion

The present study examined whether elements of the CPC 5HM model (Cognitive Advantage, Family Support, School support, Motivational advantage, and Social Adjustment; Figure 2) and other relevant factors mediated the relation between cumulative ACEs and early adult outcomes. The results will be discussed with respect to the study's three guiding hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1

As predicted, participants with high ACE scores (defined as 3 or ≥4 from birth to 18 and ≥2 from birth to age 5) were significantly more likely to experience multiple adverse outcomes, particularly in the education, health behavior, and crime domains by emerging adulthood. This held true even when the focus was narrowed to early childhood ACEs, although the strongest associations in this period were found in subgroups. Much attention has been paid to the deleterious developmental effects of impoverished environments, and justifiably so; however, our results suggest that discrete adverse experiences can significantly affect well-being in adulthood above and beyond poverty. Reduction of income inequality is an ethical imperative and an important goal, but reducing the prevalence rate of preventable ACEs is a key attainable objective in the shorter term.

Hypothesis 2

When ACEs were examined by sex, graded associations between ACEs and outcomes (e.g., high school graduation; smoking) emerged for males such that even just two or three ACEs were associated with maladaptation. For females, when ACEs were associated with outcomes, these associations were generally seen for the ≥4-ACE group only. The pattern of sex differences was less clear for early childhood ACEs. Expected associations with high school graduation, smoking, and felony charge emerged for males, but for females, effects on these outcomes only emerged for the 1-ACE group.

Among participants who lived in higher poverty neighborhoods as children, 3 and ≥4 ACEs were consistently associated with negative multidimensional outcomes. Meanwhile, among participants who lived in relatively lower poverty neighborhoods as children, ACEs were associated with fewer outcomes (high school graduation, smoking, and juvenile arrest only) and the threshold was higher (≥4 ACEs). For early childhood ACEs, the differences between the higher-poverty and lower-poverty groups were pronounced. The ACEs that occurred early were associated with criminal justice system involvement, high school graduation, and smoking in the higher-poverty group but not the lower-poverty group.

In the present study, while males were more likely to report high (3 or ≥4) ACEs (37%), a substantial number of females also reported high ACEs (28%). This is inconsistent with rates in the Kaiser/CDC ACE study (17.7% of males and 25.5% of females; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016), but this is to be expected given the different ethnic and socioeconomic makeup of the populations as well as the additional measurement of Expanded ACEs in the present study. Direct effects from ACEs to outcomes were also weaker for females in this sample. Meanwhile, participants who lived in relatively lower poverty neighborhoods as children actually experienced high levels of ACEs at around the same rate (34%) as participants from relatively higher poverty neighborhoods (32%). The stronger associations between ACEs and outcomes for males and participants from the higher poverty neighborhoods raise the possibility that lower neighborhood poverty and female sex may have rendered participants less susceptible to the negative effects of ACEs.

While the results of Hypothesis 1 support the idea that ACEs are associated with multidimensional outcomes beyond poverty, the results of Hypothesis 2 also provide evidence suggesting that the negative effects of ACEs may be amplified in the context of neighborhood disadvantage. These findings contribute to a growing body of literature that indicates that living in poverty can deplete cognitive, socioemotional, and physical resources that may contribute to resiliency, thereby compounding the effects of adversity (Cronholm et al., Reference Cronholm, Forke, Wade, Bair-Merritt, Davis, Harkins-Schwarz and Fein2015; Williams & Jackson, Reference Williams and Jackson2005). These results are especially important considering that in the present study, the lower poverty participants were still living below the poverty line, suggesting that even a minimal increase in neighborhood socioeconomic standing could exert protective effects.

The results of the present study also suggest that the interplay between ACEs and poverty is particularly deleterious for males. These results are consistent with a growing research base indicating that ACE-affected males are at increased risk for addictive behaviors and delinquency (e.g., Maas, Herrenkohl, & Sousa, Reference Maas, Herrenkohl and Sousa2008; El Mhamdi et al., Reference El Mhamdi, Lemieux, Bouanene, Salah, Nakajima, Salem and Al'absi2017). Previous research has suggested that males exhibit higher stress reactivity in the context of intrafamily adversity (e.g., family conflict, other household dysfunction) than females, and, as is evident in the present study, that males are more likely to be witnesses and victims of violent ACEs, which have been hypothesized to be associated with particularly severe developmental repercussions (e.g., Luthar, Reference Luthar2003; Schwab-Stone et al., Reference Schwab-Stone, Chen, Greenberger, Silver, Lichtman and Voyce1999). The interactions of the aforementioned factors may initiate negative biological, social, and academic cascades for males who have experienced ACEs, placing them at increased risk for negative outcomes. Although a detailed treatment is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to acknowledge that African American males, in particular, are affected by high levels of systematic discrimination and stress which may interact with ACEs to increase risk for negative outcomes (e.g., Ward & Mengesha, Reference Ward and Mengesha2013, Watkins, Reference Watkins2012). Previous research has found that the interactions among gender discrimination and racial discrimination exert particularly salient effects on academic achievement in African American boys (e.g., Cogburn, Chavous, & Griffin, Reference Cogburn, Chavous and Griffin2011). Overall, the results of this study indicate that males who have experienced ACEs—especially those living in the highest poverty neighborhoods—may benefit from additional social and academic support services.

Hypothesis 3

The present study's third hypothesis was that 5HM mediators would explain more of the effects of ACEs for participants with high levels of cumulative ACEs. The results partially supported this hypothesis. Analyses of the effects of each separate set of 5HM mediators on the associations between ACEs from birth to eighteen and outcomes generally revealed small to medium partial mediation effects in both the full sample and the subsamples. In these cases, the School Support and Motivational Advantage mediators (Figures 5 and 6) evinced the most consistent effects. Additionally, when all 5HM mediators were entered into the model along with key adolescent experiences (high school graduation and juvenile arrest), the associations were significantly reduced. These effects were particularly noteworthy for the higher poverty sample, where the seven mediators reduced associations between ACEs and occupational prestige, smoking, and felony charge by around 20–50% for high ACE groups. The latter mediational pattern is particularly strong, given that analyses investigated direct effects only, and statistical power was reduced due to the reduction of sample sizes when analyzing participants by ACE scores and further in the analysis for ACE score within subgroups. In early childhood, several mediation effects emerged for participants with high ACE scores across subgroups; however, the results did not fit a clear pattern.

Figure 6. Select effects of school support mediator for participants with high ACEs 0-18. Zero ACEs is reference group. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The 5HM mediators entered separately did not account for relationships between ACEs and adult outcomes in the group from lower poverty neighborhoods as consistently as they accounted for outcomes among participants from higher poverty neighborhoods. Furthermore, while the mediators did suggest some effects for females, both direct and mediational effects were weaker for females and patterns were less clear. This finding builds on previous research indicating that the CPC program may transmit the most benefits to males and participants who are affected by high levels of sociodemographic risk (Reynolds, Temple, Ou, et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga and White2011; Reynolds, Temple, White, et al., Reference Reynolds, Temple, White, Ou and Robertson2011). Diminished mediation effects could be attributed to the aforementioned diminished direct effects.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study exhibits several strengths, including use of data on substantiated abuse and neglect, criminal justice system involvement, and educational attainment from administrative records as well as the wide array of prospectively collected longitudinal data from a variety of sources and the low attrition rate. It also adds to the growing evidence base of larger-scale ACE studies in a primarily African American, low-income sample, and is, to our knowledge, one of the first investigating psychosocial mechanisms of ACE effects in a large sample.

It is also important to acknowledge several limitations. First, the survey relied on administrative records of abuse, neglect, and out-of-home placement. While this is in some ways a strength of this study, as it addresses concerns about the reliability of self-report, it is also well documented that abuse and neglect are often severely under-reported (Flaherty, Reference Flaherty, Sege and Hurley2008; Swahn, Reference Swahn, Whitaker, Pippen, Leeb, Teplin, Abram and McClelland2006) and we must acknowledge that we are almost certainly missing abuse and neglect cases in this sample. Second, we did not have administrative data on psychological abuse or emotional neglect; as such, we did not measure these ACEs. All other ACEs were self-reported, which presents methodological challenges as well. Research has indicated that false-positive ACE memories are rare (Hardt & Rutter, Reference Hardt and Rutter2004), but it is possible that adult participants may not have recalled, or may have been reluctant to disclose, certain ACEs. Third and relatedly, while this is in many ways a prospective longitudinal study, all self-reported ACEs were primarily reported retrospectively at age 22–24. Retrospective reporting bias is possible; however, by relying on data from the age 22–24 survey rather than more recent surveys, we sought to minimize the elapsed time between the occurrence of ACEs and participants’ reports. Consistency analyses indicated that most participants were acceptably consistent across reporting periods. Fourth, the present study's ACE measure, which was similar to ones used in previous ACE studies, did not comprehensively assess all ACEs relevant to a sample in urban poverty. As such, we may have underestimated the true prevalence of ACEs in the sample. Fifth, this study was conducted with a predominately African American, urban sample, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results. Additional work is needed to examine whether elements of the 5HM model mediate the relations between ACEs and adult outcomes for individuals from different races and ethnicities, geographic locations, and generational cohorts. Finally, given that the modeling approach to mediation is correlational, causation should not be inferred and further research is needed.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The results of the present study have important implications for policymakers and practitioners. Primarily, these results complement and expand previous findings indicating that ACEs are associated with increased risk of negative outcomes in emerging adulthood across multiple domains of functioning (Giovanelli et al., Reference Giovanelli, Reynolds, Mondi and Ou2016). Moreover, acknowledgement of the reverberation of these effects beyond physical health problems to broader well-being plays an important role in identifying effective, scalable prevention and intervention efforts. There is a critical need for primary prevention initiatives directed at reducing the incidence of ACEs and identifying ACE-affected youth. Such initiatives will ideally include individuals from multiple levels of children's social ecologies. For example, previous research has demonstrated that it is feasible to conduct ACE screenings in clinical and school settings and to conduct follow up trauma-symptom screenings with ACE-affected youth (e.g., Bethell et al., Reference Bethell, Carle, Hudziak, Gombojav, Powers and Braveman2017; Giowa, Olson, & Johnson, Reference Giowa, Olson and Johnson2006; Gonzalez, Monzon, Solis, Jaycox, & Langley, Reference Gonzalez, Monzon, Solis, Jaycox and Langley2016).

Previous work has also demonstrated the value of assessing parental mental health and family well-being at prenatal and postnatal medical appointments, to identify families facing adversity or at risk of ACEs (e.g., Marcus, Flynn, Blow, & Barry, Reference Marcus, Flynn, Blow and Barry2004; Olson, Dietrich, Prazar, & Hurley, Reference Olson, Dietrich, Prazar and Hurley2006). Beyond child self-report and parental report, trauma-informed training has been shown to increase other caregivers’ and educators’ abilities to identify and support ACE-affected children and families (e.g., Ko et al., Reference Ko, Ford, Kassam-Adams, Berkowitz, Wilson, Wong and Layne2008; Layne et al., Reference Layne, Ippen, Strand, Staber, Abramovitz and Pynoos2011).