In Done into Dance: Isadora Duncan in America, Ann Daly writes that Isadora Duncan defined her dance as high art, and describes how Duncan raised the dance from the bottom of the cultural landscape to the top of American society:

Dancing was considered cheap, so she associated herself with the great Greeks, who deemed the art noble, and she associated herself with upper-class audiences by carefully courting her patrons and selecting her performance venues. Dancing was considered mindless, so she invoked a pantheon of great minds, from Darwin to Whitman and Plato to Nietzsche, to prove otherwise. Dancing was considered feminine, and thus trivial, so she chose her liaisons and mentors—men whose cultural or economic power accrued, by association, to her. Dancing was considered profane, so she elevated her own practice by contrasting it to that of “African primitives.” The fundamental strategy of Duncan's project to gain cultural legitimacy for dancing was one of exclusion. (Daly Reference Daly1995, 16)

Regarding Duncan's career path, Daly identifies Duncan's dance as one defined by exclusion (a dance that situated itself outside potentially scandalous discourses that raised questions of propriety and morality), and drives the point home in her appraisal of Duncan's oppositional conception of art. She notes that in her later writings, Duncan saw the “harmonious fluidity” of her own dance as “prayerful liberation,” while criticizing the “spastic chaos of ragtime and jazz dancing as a reversion to ‘African primitivism’” (Daly Reference Daly1995, 6). Daly's theory of Duncan's dance of exclusivity explains how Duncan situated her dance outside of the discourses of eroticism and exoticism, yet does not account for why Duncan needed to exclude them, nor how Greece became the lingua franca for her art. While Duncan condemned others for allowing their dance to appeal to audiences seeking erotic performance, she discreetly diverted attention from her own Parisian audiences' tastes. Focusing on her American tours, Daly highlights the “African” as the abject pole that the dancer positioned herself against; however, her French audiences had a whole host of alternative “uncivilized, sexual, and profane” dances to compare to Duncan's (Daly Reference Daly1995, 7).

This article examines the roots of Duncan's mature elevated “Hellenized” aesthetic reified in her prose writings and lectures as she garnered international fame touring Europe and America between 1903 and 1908. Once internationally successful in the 1910s, Duncan formulated an art of realignment, reinterpretation, and exclusion, reconfiguring and separating her elevated vision of ancient Greece in opposition to the Sapphic Greek fantasies of her early patrons in Paris and the erotic and exotic “Greek” fantasies on public stages. Upon her arrival in Paris in 1900, Duncan formed relationships and performed for an influential group of expatriate lesbian American women who received Duncan's early performances of private “Greek” gestures within the context of the private Sapphic music and dramatic activities popular in Paris between 1900 and 1910.Footnote 1 Interpretations and appropriations of antiquity in Parisian culture of the period between the Franco-Prussian War and WWI were unstable and changed according to venue and audience—a circumstance that allowed Duncan to redefine herself and her art years later, while insisting on a connection to antiquity.

Duncan's social and aesthetic involvement with Natalie Clifford Barney's (1876–1972) private community and the later claims of ignorance regarding the lesbian audiences' reception of her dance attest to Duncan's complex navigation and appropriation of varying meanings of antiquity in the first three decades of the twentieth century. This article suggests that Duncan's early private audiences in the years around 1900 shaped the aesthetics of her performance and, in particular, her writings from “The Dance of the Future” (Reference Cheney1903) through her autobiography, My Life (1927). Due to initial associations with exotic and erotic conceptions of ancient Greek arts and culture as seen in the choreography at the Paris Opéra, it quickly became necessary for her to devise a new aesthetic framework in her public speeches and published writing in defense of her movement vocabulary and to appeal to a public audience. Comparisons to writings and reviews of the Mme. Mariquita's (1830–1922) exotic choreography for the famously erotic dancer at the Opéra, Régina Badet (1876–1949), as well as Duncan's contemporary Eva Palmer-Sikelianos's (1874–1952) dances, writings, and navigation of queer spectatorship, help illustrate how Duncan used writing to universalize her dances.

Revisiting Duncan's Greek dance within the context of lesbian spectatorship in Paris allows us to see her writings from 1903–1927 as a way to pivot from one mode to another—to realign, reinterpret, and exclude discourses of ancient Greece, modern dance, and sexuality. Whereas Daly's argument privileges the American response to Duncan's dancing, this article focuses on the overlooked Parisian context of the artist's Greek dancing.Footnote 2 It was in Paris, not the US., where Duncan found patronage from an influential and wealthy network of lesbian women living in Paris interested in the types of dances and the modes of scholarship exhibited in Duncan's work. It is within this context that Duncan's changing relation to the Greeks, and her audiences' changing responses to her own changing views on antiquity, should be evaluated.

Not only did Duncan exclude discourses, she reshaped and re-evaluated familiar discourses to suit her needs. In this way, Duncan used antiquity to differentiate herself from certain contemporary uses of Greek culture, and she did this in a way that embraced and realigned the discourses of nakedness and sensuality in Greek art honoring women's bodies connecting to what she viewed as the rhythms of the universe in both sacred and erotic ways. As I will illustrate, Duncan's relationships to Greece, to sensuality, to dance itself, are not just dialectical. The shifting, realigning positions bump against each other, like members of a crowd, with different ideas shifting position at the front of the line. As Mark Franko writes,

To question whether Duncan's version of ancient Greece was authentic, whether her research into quattrocento art qualified as real scholarship, or whether her interest in classical antiquity did not flagrantly contradict her burnished image as modernist innovator, are pointedly irrelevant. Such approaches to dance history fail to perceive the very dialectical relationship of the past and the future to the present in Duncan's choreography. (Franko Reference Franko1995, 20)

Although Duncan's aesthetics shift and adapt in more organically complex ways than Hegelian dialectics, Franko's point is well put. Duncan's changing attitudes in her writings, along with her dances, influence each other and reveal an artist with an eye toward the past (ancient Greece, her own past performances), her audience (her early patrons in Paris, and later international audiences), as well as the future (her legacy, modernism).

Nonetheless, while Duncan may have elevated dance for American audiences by attaching it to the universal aesthetics of Greek antiquity,Footnote 3 her original forays into Greek dance were displayed for a private (mostly American expatriate) audience who understood Greek dance as part of a larger exotic and erotic discourse. As Jane Desmond stated in her introduction to Dancing Desires, “The ‘swish’ of a male wrist or the strong strides of a female can, in certain contexts and for certain viewers, be kinesthetic ‘speech-acts’ that declare antinormative sexuality” (Desmond Reference Desmond and Desmond2001, 6). This project not only identifies those contexts and viewers, but places them within the artist's own discourse of her developing art.

Since my argument is centered around impressions of Duncan's art as well as the dancer's own words on the subject, I do not include specific dance examples. The reception history discussed here has little to do with what Duncan may or may not have actually done on stage, and more with what some of her audiences imagined they saw, or what the dancer ultimately wanted her audiences to read in her writings.

Dancing for the Elite: Duncan and the Parisian Salon Circuit

Disillusioned with American theater, Isadora Duncan sailed to London with her mother and brother, Raymond, in May 1899, where she struggled for recognition. In a year she would leave for Paris, where her London contacts helped her secure an introduction to the important salons (Kurth Reference Kurth2001, 55–67). Duncan was not the only woman performing “Greek” dances in Paris in 1900, and the dancer was “bitterly disappointed” by what passed as “Greek dancing” in Paris upon her arrival. In a letter from the same year, she noted that the “Greek” dance at the Opéra was “a sort of modified Ballet in white gowns.” She characterized it “as all stupid, vanity and vexation […] Not the slightest glimmering knowledge of Apollo—or the Graces—or even of the kindly Pan” (I. Duncan 1900).

While many “Greek” dancers drew notorious reputations as dancer/courtesans (Liane de Pougy and Cléo de Mérode, for example), Duncan managed to deflect most of this attention. A large part of this was due to her ability to negotiate discourses of the past and to carefully choose with whom she associated. Chief among Duncan's benefactors were respected and established members of the aristocracy and social elite: Countess Elisabeth de Greffulhe, and the homosexual Prince and his lesbian wife, the Princesse Edmond de Polignac.Footnote 4

The Polignacs first saw Duncan at the salon of Meg de Saint-Marceaux in the winter of 1901. They found themselves immediately drawn to the young American dancer: the Prince envisioned artistic collaborations, and the Princesse sought a friend, perhaps a lover, and an artistic muse. After this first encounter, Duncan was quickly brought into the Polignac salon after the Princesse paid a surprise visit to Duncan's studio.Footnote 5 Her collaboration with the Prince yielded a program of “Danses-Idylles” planned for performance, chez Polignac: The greatly expanded guest list for this particular event on May 22, 1901 signals the Polignacs' aim at assisting the young Duncan in wooing more patrons (Kahan Reference Kahan2004, 117). Years later, after Duncan had already established herself as the leading figure on the international dance scene, she famously started a relationship with Paris Singer, the similarly wealthy brother of the Princesse de Polignac.

Naturally, the Polignacs saw something in Duncan's dance that attracted them, and the dancer could count on the Polignac and Singer families' assistance (at least through her affair with Paris Singer), but Duncan also had other patrons in these early years. Comtesse Elisabeth de Greffulhe, another queer-friendly leader of Parisian social society, staged one of Duncan's first major salon debuts in Paris, quickly followed by a recital at the salon of Madame Madeleine Le Marre, where Duncan noted that she “saw among [her] spectators for the first time, the inspired face of the Sappho of France, the Comtesse [Anna] de Noailles …” (I. Duncan 1927, 61), a poet and one of the Princesse de Polignac's most intimate friends and lovers. Natalie Barney, yet another lesbian American expatriate, also sat in the audience of one of these early recitals.

A tantalizing story has come down to us from one of these early salon performances in Paris from 1900, where Barney, her lover Renée Vivien,Footnote 6 and her mother were in attendance. The three Americans sat in the front row, and when Duncan learned that fellow countrywomen were in the audience, she asked her accompanist (reportedly a young Maurice Ravel) to play the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Suzanne Rodriguez retells the rest of the story in her biography of Barney as follows:

[Duncan] invented a free-flowing dance to match the music, and, at its climax, grabbed the skirt of her Greek tunic and lifted it high. Beneath the graceful, flowing white robes she was completely nude. Natalie was no doubt delighted by the unexpected ending, but Alice [her mother] was shocked to the core. Stunned, she turned to her daughter and sputtered: “Darling, do you see what I see”? Natalie collapsed with laughter. (Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2002, 113–114)Footnote 7

Duncan's “Star-Spangled Banner” performance would then precede her famous “La Marseillaise” by at least a decade. Concerning this dance, Daly notes that in 1914, “Duncan's body was enfolded in a blood-colored robe that bared her shoulders and, according to some reviewers, bared a breast at her moment of triumph” (Daly Reference Daly1995, 185).

Barney and Duncan became friendly after that encounter in 1900, and in 1909 (when Barney opened her famous salon on rue Jacob), Duncan was an early regular. Like Singer-Polignac, Barney was another wealthy American expatriate. She had inherited the family's railcar fortune in 1902 and used it to set up her salon first in Neuilly and then at 20 rue Jacob, where she attracted sensationalist gossip. She studied French and Greek, and in 1897 she suggested to two of her lovers—Olive Custance (1874–1944) and Renée Vivien (1877–1909)—that they start their own “Sapphic circle” dedicated to the love of beauty and sensuality. Other initiates to the circle included the dancer/courtesan Liane de Pougy and the artist Romaine Brooks.

Like other women of letters at this time, Barney learned Greek and poetic forms with private tutors in order to gain the mark of the “intellectual aristocracy” (Marcus Reference Marcus, Heilbrun and Higgonet1983, 86). Knowledge of Greek and Latin, previously unavailable to nineteenth-century women, had by this point become the benchmark of true excellence in female education. While for men the study of the classics was de rigueur, for women it required expensive specialized tutoring, since classes at many universities were closed to them (Marcus Reference Marcus, Heilbrun and Higgonet1983; Prins Reference Prins1999, 76–79). Barney's dedication to her classical studies was quite serious.

While mainly known for her literary contributions, Barney also supported music and dance. Early in Neuilly, Barney staged “Greek” theatrics and tableaux vivants incorporating music and dance for the women in her circle. Dressed in elaborate costumes as ladies and pageboys, Greek nymphs, or nude muses, visitors to Barney's home enjoyed a place where many women could express their sexuality freely without fear of persecution or judgment, amidst a bouquet of exotic incense and under the watchful gaze of Sappho's statue.

On the heels of major discoveries of Sappho's poetry beginning in 1892, the Sappho worship in Barney's garden began when Barney still resided in Neuilly circa 1900.Footnote 8 A photograph from one of the early performances form around 1905 or 1907, shown as Photo 1, depicts a group of women in Greek costume, hands raised, circling a raised platform holding an unidentified flute player, Penelope Duncan (Isadora Duncan's sister-in-law) playing harp, and a singer or orator who may be Eva Palmer. The courtesan Liane de Pougy appears on the far left side of the image looking at the camera, and Natalie Barney is in the center (in white in half-profile).

Photo 1. A gathering of women including Eva Palmer, Natalie Barney, and Liane de Pougy in Barney's garden in Neuilly. Smithsonian Institute Archives, Alice Pike Barney Papers Acc. 96-153, folder 6.193.

Colette discussed one early Greek-inspired performance in Neuilly where she and Eva Palmer dramatized Pierre Louÿs's Dialogue au soleil couchant (a simple Arcadian tale of a Greek shepherd, who falls for the beautiful Greek maiden, who at first remains hesitant until she succumbs to the shepherd's voice). In Barney's garden, the aspiring actresses, Palmer as the maiden to Colette's shepherd, performed this homoerotic fantasy adorned in ancient Greek costumes and accompanied by a group of violinists hidden behind a boulder (Colette Reference Colette1936, 158; Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2002, 155).

June 1906 saw the production of Barney's Équivoque, a play derived from Sappho fragment 31, one of the most famous, most complete, and most discussed shards of poetry we have from the historical poet.

He seems to me equal to gods that man

whoever he is who opposite you

sits and listens close

to your sweet speaking

and lovely laughing—oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking

is left in me

no: tongue breaks and thin

fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead—or almost

I seem to me.

But all is to be dared, because even a person of poverty […] (Sappho Reference Sappho and Carson2002, 63)

As both Joan DeJean and John J. Winkler have noted, the classic geometry of Sappho's love triangle in this poetic fragment is radically altered not only by gender, but, perhaps most importantly, by angle (DeJean Reference DeJean1989, 49–50; Winkler Reference Winkler1981). The three sides of Sappho's triangle are far from equal. The female narrator (identified by the gendered cases of the original Greek, and the familiar French translations) almost eliminates her male competitor, lavishing her poetic attention on her own sublime suffering and her object of desire. The man has been relegated to merely a pronoun: “whoever he is” renders him “any man,” diminishing the male character side of the triangle brings the other two sides closer together (also see Latacz Reference Latacz1985; Lidov Reference Lidov1993; O'Higgins Reference O'Higgins1990). Barney's drama uses Sappho's geometry. The performance in her garden casts Colette and Eva Palmer as Sappho and her lover, a bride-to-be, who abandons Sappho for marriage. “Within a circle of columns on the lawn stood a five-foot wrought-iron brazier wafting incense toward the audience. The barefoot or sandaled actresses, clad in gauzy white floor-length Greek robes, danced to Aeolean harp music and traditional songs performed by Raymond Duncan and his Greek wife, Penelope” (Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2002, 157).

Rodriguez notes that Duncan only occasionally danced at these gatherings. Whether she attended the salon for social, business, or amorous reasons, one cannot be sure; however, as Susan Manning has demonstrated, Duncan indeed had lesbian affairs with women: the dancer, Mercedes de Acosta among others (Manning Reference Manning1999, 18–25). The descriptions of Barney's outdoor theatrics resonate with Duncan's own aesthetic for natural movement, ancient Greek culture and costume, and performance en plein air. Upon her arrival in Greece in 1903, Duncan made the following statement, which could very easily describe Barney's garden scene depicted in Photo 1: “My idea of dancing is to leave my body free to the sunshine, to feel my sandaled feet on the earth […] My dance at present is to lift my hands to the sky” (I. Duncan Reference Rosemont1994, 36).

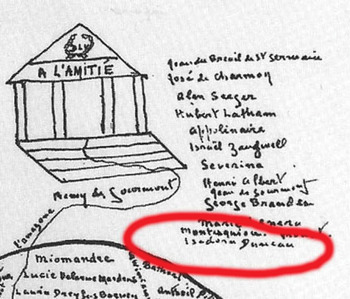

Duncan also knew another famous member of Natalie's inner homoerotic circle, the actress and dancer, Eva Palmer (later known as Eva Palmer-Sikelianos, one of Barney's lovers and artistic collaborators). Later married to the Greek poet Anghelos Sikelianos (whose sister was later married to Raymond Duncan), Eva harbored bitter jealousy of Duncan yet remained friendly with her due to their shared expatriate status and love of Ancient Greece. And in the 1920s—while it was apparently more common to see Raymond and Penelope Duncan in their flowing “Greek” robes at Barney's salon than his sister (Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2002, 247)—Duncan was not too far away from Barney's world. At least in Barney's mind, Duncan featured prominently in her backyard temple à l'amitié [Temple to Friendship].Footnote 9 In 1929, Barney drew up a “map” of the leading figures behind her salon, where among the names closest to the temple, Duncan would have found herself along with other such notables as Renée Vivien, Proust, Apollinaire, and Pierre Louÿs (see Photos 2 and 3).

Photo 2. Natalie Barney's Drawing of her “Temple à l'Amitié,” frontispiece to l'Aventures de l'espit (Reference Barney and Gatton1929).

Photo 3. Isadora Duncan's name is the last name listed on the right hand column at top.

Clearly there was an active lesbian spectatorship of Duncan's early semi-private performances, but more importantly, an early American, expatriate, lesbian patronage of Duncan in her first years in Paris. Barney's garden—her infamous backyard at 20 rue Jacob on the Left Bank of Paris—was perhaps the epicenter of this reception.

While scant documentation survives from the private performances, responses to Duncan's dances in more public venues are plentiful and may shed light on some of the potential modes of reception by her American audiences in Paris. Margherita Sargent Duncan provided an insightful vignette into her famous sister-in-law's art and its capacity to take hold of an audience. She first saw Duncan dance at a Carnegie Hall performance of Gluck's Iphigénie. She wrote:

I experienced what I can only describe as an identification of myself with her. It seemed as if I were dancing up there myself. This was not an intellectual process, a critical perception that she was supremely right in every movement she made; just a sense that in watching her I found release for my own impulses of expression; the emotions aroused in me by the music saw themselves translated into visibility. Her response to the music was so true and inevitable, so free from personal eccentricity or caprice, her self-abandonment to the emotion implicit in the music so complete that although I had never seen nor imagined such dancing, I looked at it with a sort of delighted recognition. (M. Duncan Reference Duncan and Cheney1928, 17)

Margherita's recollection might serve as a response to Duncan's dancing in the Parisian salon. Finding recognition in her movements, the sense of abandon, finding release for her own impulses, can all very easily be read with a not too subtle hint of eroticism.

Isadora Duncan's “Greece”

It is clear that Isadora Duncan's early patrons in Paris appreciated the “Greek” aspects of her dance that fit into their own identifications with feminine agency and the license of Greek eroticism. Duncan's dance had often been characterized as “Greek” by the dancer herself as well as by her critics. Still, the question remains, what was Greece to Isadora Duncan? Her writings raise more questions than they provide answers. She did not write any coherent system for engaging with ancient Greece through dance. Instead, Duncan left lofty language and contradictions for her readers to work with. Without a clear statement from Duncan, we have to explore Duncan's conflicting and varied discussions of her dance and antiquity with care. Of all the influences on Duncan's writing, Nietzsche's dominated. The philosopher played a central role in Duncan's conception of dance and philosophy. However, while the dancer's own elliptical prose asserts Nietzsche's prominence in her thinking, she rarely provides opportunities for her readers to isolate Nietzsche's philosophy in her work. Kimerer L. LaMothe writes, “Both [Nietzsche and Duncan] embraced ancient Greece as an ideal—an ideal of an alternative mode of valuation, that identifies what Nietzsche and Duncan called the Dionysian energies of life” (Reference LaMothe2006, 113). While Nietzsche may have proved revelatory to Duncan, it should be noted that the dancer discovered an interest in ancient Greece prior to finding a sympathetic thinker in Nietzsche (LaMothe Reference LaMothe2006, 112).

Perhaps first drawn to ancient Greece through the family's visit to London in 1899, Duncan's interest in the physical remnants of ancient Greek culture led to visits to the British Museum, as well as trips to Greece in 1902, all before reading a word of Nietzsche. It was not until 1903 that she seriously began reading the philosopher's works; moreover, that year Duncan most famously discussed her art in a speech, Der Tanz der Zukunft, a most consciously composed Nietzscheian and Wagnerian essay on the future, present, and past of dance (see LaMothe Reference LaMothe2006, 105–110, and 112–114). The speech delivered to the Berlin Press Club became her artistic manifesto outlining how she wished her dance of the future to be viewed by her expanding public audience. In this speech, the American Duncan, an ardent admirer of Nietzsche and Wagner, remained ignorant, or at least purposefully removed, from the French sectarian battles (see Deudon Reference Deudon1982; Forth Reference Forth1993, Reference Forth2001; Nematollahy Reference Nematollahy2009). The dancer freely cited the philosopher throughout her writings (My Life and The Art of the Dance) and unabashedly equated her dance of the future with a Nietzeschian call for a new moral order—a new religion. As Ann Daly writes in her monograph on Duncan's dance on tour in America, “Most significant, Duncan used this opportunity [The Dance of the Future] to build upon a compelling, but largely imaginary, past—specifically, the ancient splendors of the Greeks—to create a foundation for the ‘Dance of the Future’” (Daly Reference Daly1995, 29).

What will this dance of the future look like, and how will it be Greek? Duncan stated early on in her public speeches and writings that: “If we seek the real source of the dance, if we go to nature, we find that the dance of the future is the dance of the past, the dance of eternity, and has been and will always be the same” (I. Duncan Reference Cheney1903, 54). She then, of course, demonstrated the eternal beauty of the ancient Greek poses she studied in statuary and on pottery in museums and concluded

The Greeks in all their painting, sculpture, architecture, literature, dance and tragedy evolved their movements from the movement of nature, as we plainly see expressed in all representations of the Greek gods, who, being no other than the representatives of natural forces, are always designed in a pose expressing the concentration and evolution of these forces. That is why the art of the Greeks is not a national or characteristic art but has been and will be the art of all humanity for all time.

Therefore dancing naked upon the earth I naturally fall into Greek positions, for Greek positions are only earth positions. (I. Duncan Reference Cheney1903, 58)

Echoing statements made earlier about nakedness and nature, Duncan equated the aesthetic of ancient Greece as an ideal, a universal aesthetic, with an elemental nakedness, simplicity, internationalism, and an ahistorical sensibility. Her interest in universals in art reveals a very familiar modernist approach, one that privileges an artificial objective concept of form and simplicity over subjective ideas of identity. Duncan's dancer of the future will be international: she is not a nymph, not any other mythological, heavenly, or supernatural creature; she will not be a “coquette” either, she said. She will be a woman “in her greatest and purest expression” (I. Duncan Reference Cheney1903, 62–63).

While Duncan often reconfigured and realigned antiquity to suit her needs, at times, she was not opposed to the art of exclusion (Daly Reference Daly1995, 16). In an essay on the Greek dance, Duncan traced the oldest dances to Asia and Egypt, which she believed obviously influenced Greek dancing. She reminded her readers that “those earlier dances were not of our race; it is to Greece that we must turn, because all our dancing goes back to Greece” (I. Duncan Reference Cheney1928a, 92). Any example of grotesque figures “expressing Bacchic frenzy,” she mentioned in another article, “expresses a ‘stop;’ one knows that it cannot continue, that it can only be its own end” (I. Duncan Reference Cheney1928b, 91). Ancient Greek movements that Duncan found unacceptable for high art were either made extinct or relegated to the fault of other races. Duncan drew a teleological line from primitive man to the Ancient Greeks, which then (of course) led straight to her dance of the future. Nakedness is equated with authenticity, freedom, and timelessness—a Hellenic primal bodily language—not eroticism or wantonness.

Thus, Nietzsche provided Duncan with the resources to embrace Greece from a new perspective, allowing her to engage with a newly conceptualized mystical Greek nudity, a bodily being, a human agency, and erotic freedom free of lascivious connotations. This is not to say that prior to her acceptance of Nietzsche, Duncan lacked the language to express her aims. Rather, Duncan saw Greece in less lofty terms, as a vehicle for self-expression and self-promotion among a class of patrons who could further her career and separate herself from her imitators.

As a contrast to the dancer “free from personal eccentricity or caprice,” Margherita Sargent Duncan related an anecdote concerning the famous dancer's “Greek” imitators. Isadora Duncan was slated to help inaugurate a performance in New York City in 1916,

… and while waiting to begin, she found herself near a group of “Greek” dancers, trained by one of her imitators. One of these girls, excited by the occasion and the proximity of the great dancer, said to Isadora archly, “If it weren't for you, we wouldn't be doing this. Don't you feel proud?” Isadora looked at the poor child and said, “I regard what you do with perfect horror.” (M. Duncan Reference Duncan and Cheney1928, 18)

Isadora Duncan objected to these imitators saying, “Their movements are all down, groveling on the earth. They express nothing but the wisdom of the serpent, who crawls on his belly” versus her own “rhythmic line [which] was always up” (M. Duncan Reference Duncan and Cheney1928, 18–19). These portraits from Duncan's writings illustrate an idealized transcendent artistry that she promoted in her later career beginning around 1908: an uplifting universal “Greek” spirit removed from the base displays of her “Greek” imitators.

Dancing Orientalist Delights and Desires: Régina Badet in Aphrodite

In addition to her numerous imitators, Duncan sought distance from her contemporaries specializing in the “Greek” dance performed on the public stages of the opera and music halls. While her prose might have attempted to elevate her dances toward an idealized Greek mode, her movements were not significantly different from dancers who sought to titillate. Between 1870 and 1912, numerous “Greek” ballets and operas with large ballet sequences graced the public stages of Paris. Operas, ballets, and music-hall productions with “Greek” themes such as the operas Polyeucte (1878), Hérodiade (1881), Thaïs (1894), Briséïs (1897), Sapho (1884, revival of Gounod's 1851 opera), Sapho (1897), Aphrodite (1905), and La danseuse de Tanagra (1911), as well as the ballets Fleur de Lotus (1893), Phryné (1897), The Vision of Salome (1906), La tragédie de Salomé (1907), Rêve d'Egypte (1907), and Narcisse (1911) very often appealed to the public's taste in works that were exotic, erotic, and ancient.

As a contrast to Duncan's idealized “Hellenized” Greek discourse, take the opening scene from the 1906 production of Camille Erlanger's opera based on Pierre Louÿs orientalist Greek novel of the same name, Aphrodite. This public performance of the private homoerotic “Greek” dance resists Duncan's discourse of universal art and “Hellenized” naturalness in favor of colorful and exotic decors, revealing costumes, lurid plots, and erotic movements. Set in Greek Alexandria in the year 57 BCE, the opera tells the tale of a gifted sculptor, Demetrius, and the lesbian courtesan, Chrysis. Demetrius, enraptured by the half Greek and half Jewish Chrysis's beauty, offers her gold for her services, but she instead asks for three items: Sappho's mirror, the pearl necklace around Demetrius's own sacred idol of Aphrodite, and the comb of the wife of the High Priest. Once the gifts are delivered she promises to be entirely his. Fuelled by passion, the sculptor murders and steals in order to obtain the objects. At the end of the opera Chrysis emerges nude, bearing the comb, necklace, and mirror in front of the crowd of mourners. They initially take her for a goddess, but soon realize that she was the mastermind behind the thefts and murders. She is put to death for her crimes. The novel's eroticism and references to lesbianism were not subtle, and adapting Chrysis's raw sexuality for the opera stage required some delicacy (McQuinn Reference McQuinn2003). Despite these difficulties, these topics proved particularly appealing to fin-de-siècle Parisian audiences. Emily Apter writes that such Parisian fantasies of ancient Greece often leaned toward the exotic and oriental, noting that “[t]his conflation of Greece and the orient was of course particularly common in turn-of-the-century art, literature, opera, dance and theatre; syncretistic otherness was the fashion, spawning a wild hybridity of styles—Egypto-Greek, Greco-Asian, Biblical-Moorish (Apter Reference Apter and Diamond1996, 24).”Footnote 10 Sappho's liminal status as Lesbian (Eastern Greek, that is) lyric poet proved particularly fertile for exotic and oriental fantasies (Prins Reference Prins and Greene1996, 46–53; Reynolds Reference Reynolds2000).

Similarly, according to Apter, the “orientalist stereotypes” were used as a vehicle to express “sapphic love,” most notably for Colette and Ida Rubinstein, but this could apply to popular dancers Régina Badet, Liane de Pougy, and Cléo de Mérode as well. And, it should be noted that each of these women were fixtures at one time or another in the salon of Natalie Barney (Apter Reference Apter and Diamond1996, 19).Footnote 11 She also points out that the unique and interesting aspect of Colette and Ida Rubenstien's forays into orientalism “is the use of orientalism as an erotic cipher, a genre of theatricality in which acting ‘oriental’ becomes a form of outing” (Apter Reference Apter and Diamond1996, 20). Rubinstein and Colette were not alone in their use of antiquity as cipher for queer eroticism.Footnote 12Aphrodite represents a much more explicit statement of the collision of these worlds.

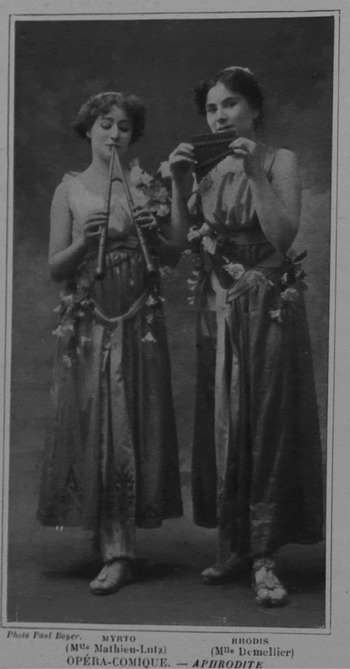

The opera opens with Chrysis's two very young lesbian handmaidens (Myrto and Rhodis) playing flutes and singing an erotic song about Eros and Pan. While they perform their music, Théano (Rhodis's sister) “exécute des poses et des pas [performs poses and steps]” (Gramont 1914 and Reference Gramont1905, 2); see Photo 4.

Photo 4. Production Photo of Myrto and Rhodis in Aphrodite. Le Théâtre No. 176 (April – II, 1906).

While it was the famed English soprano, Mary Garden, who created the role of Chrysis for Aphrodite, apparently, the real draw of Erlanger's opera was Régina Badet, the dancer who originated the role of Théano, the dancing sister of Rhodis; see Photo 5.

Photo 5. A Russian postcard of Régina Badet in Aphrodite. Author's personal collection.

In numerous reviews, Badet received more press than Mary Garden herself. Julie McQuinn distills a number of these reviews below when she writes:

The critics raved: […] “Mlle Régina Badet flies into a passion and writhes, whirls, and dances with an extreme frenzy;” “even more colorful, striking, real … are the evolutions of the dancer Théano, for which M. Erlanger was inspired by ancient Greek songs—totally authentic.” […] she has the “grace of a little savage.” (McQuinn Reference McQuinn2003, 165)

The performance made Badet a star, and the dancer went on to appear in numerous other exoticized Greek dance performances. Her performance in the 1912 operetta Sapphô not only featured exotic locals, but garnered more attention for its piquant political commentary and satirical pokes at other erotic “Greek” performances (Dorf Reference Dorf2009; Roubier Reference Roubier1912). But how different was Badet's dance from that of Duncan? Scant information is available, save the reviews. A manual for the Opéra-Comique's staging of Aphrodite includes no information about Badet's actual choreography except that she was always the center of attention while on stage (see McQuinn Reference McQuinn2003, 165). While there is little critical material to compare, the dancer's inspirations show how Duncan's dancing found its way to Régina Badet's opera stage. In an article for Comœdia Illustré, Mme. Mariquita (1830–1922),Footnote 13 then the maîtresse de ballet at the Opéra-Comique and a renowned expert of exotic dance, discussed how she approached the Greeks:

I write nothing … I think, I consider, I arrange things in my head, but this mental work is only a preparation.… I do not fix anything definitively until I am in the studio with my dancers. By that time I know the poem [scenario] well … I have thought about this for a long time. […] I made haste to visit museums, to examine ancient vases, frescoes and statues … and I studied many documents carefully and at length to find the poses, attitudes and gestures on which all my entertainment will be based…. What can you expect? I am just the interpreter! … I neither invented nor created Greek art. (Talmont Reference Talmont1908, 23)Footnote 14

The similarities in her methodology and prose correspond all too closely with that of Duncan, albeit without Duncan's rhetoric of universal beauty. In 1928, Shaemas O'Sheel wrote concerning Duncan's dance:

She found image and evidence for this in Greek sculpture and frescoes and the figures on vases. Rationalistically she overlooked, but instinctively she understood, that many of these were made in a time of sophisticated and urban civilization, and pictured a dance that was not immediately from nature, but was part of centuried ritual. […] Isadora went to Niké Anapteros, to Nature; Greece was merely on the way. (O'Sheel Reference O'Sheel and Cheney1928, 34–35)

And Duncan herself wrote how her search for “primary movements [of] the human body” brought her to classic Greek art:

[W]e might take the pose of the Hermes of the Greeks. He is represented as flying on the wind. If the artist had pleased to pose his foot in a vertical position, he might have done so, as the God, flying on the wind, is not touching the earth; but realizing that no movement is true unless suggesting sequence of movements, the sculptor placed the Hermes with the ball of his foot resting on the wind, giving the movement an eternal quality. […] In the same way I might make an example of each pose and gesture in the thousands of figures we have left to us on the Greek vases and bas-reliefs; there is not one which in its movement does not presuppose another movement.

This is because the Greeks were the greatest students of the laws of nature, wherein all is the expression of unending, ever-increasing evolution, wherein are no ends and no stops. (I. Duncan 1909, 57)

Whereas Mariquita focused her attention on the physical evidence to develop her interpretation of these movements for the present, Duncan and her admirers followed the implied movements of artifacts of Greek dance like the North Star to find their way to a dance of “nature.” Both carefully situated their own creations between the evidence of the past and the tastes of the present, or more precisely in Duncan's case, the evidence of the past and the art of the future distilled through Nietzsche's reading of antiquity.

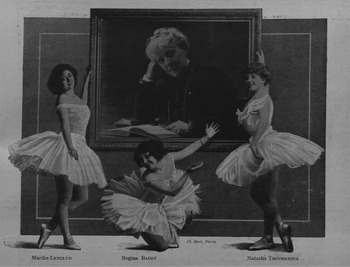

As the foremost authority in her day on creating exotic dances for the stage, it is quite telling that Mariquita's work for the public stage resembled Duncan's work stemming from her performances for private audiences (the Comtesse de Greffuhle, Natalie Barney, and the Prince and Princesse de Polignac among others). Anne Décoret-Ahiha writes of her, “Mariquita's talent certainly lay in her ability to create the illusion of exoticism in the gestures” (Décoret-Ahiha Reference Décoret-Ahiha2004, 152).Footnote 15 Like Duncan, Mariquita choreographed contemporary dances rather than recreating ancient ones, and as Badet's teacher and overseer of dance at the Opéra-Comique, the maîtresse de ballet led the young dancer and supervised her choreography (Talmont Reference Talmont1908, 23); see Photo 6.

Photo 6. Students (Marthe Lenclud, Régina Badet, and Natacha Trouhanova) honoring Mme. Mariquita. Comœdia Illustré 1e Année, No. 1 (December 15, 1908).

Louis Laloy, the French music critic and scholar, also saw a connection, or at least similarities, between Badet and Duncan when he wrote:

All the adepts of antique gesture, not excepting Isadora Duncan, a pastoral Greek, and Régina Badet, a sugarplum Tanagra figurine, have made the mistake of transferring to the stage appearances which they copied from bas-reliefs or vases, not sparing one art any of the conventions peculiar to the other. (Laloy Reference Laloy1912, 847)

At least in Laloy's mind, the two women failed in the same way, and while they represent different fantasies of Greece for Laloy, they nonetheless both played out similar malapropisms of Greek movement vocabulary as imagined by Laloy.Footnote 16 Neither seemed to embody the perfect blend of ancient sensibilities for the critic.

Even more telling is the photographic evidence. A photo spread from Le Théâtre on Badet's performance of Théano from Aphrodite shows strikingly similar poses to those of Isadora Duncan; see Photo 7.

Photo 7. Régina Badet as Théano in scene three of Aphrodite, 1906. Le Théâtre (April – II, 1906).

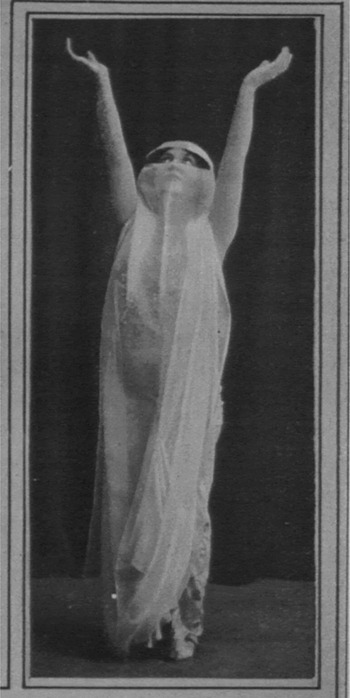

See in addition Photos 8 and 9. In particular, compare the detail from the upper right hand corner depicting Badet from the third scene of the opera with a photo of Duncan taken years later from her Ave Maria.

Photo 8. Detail of Régina Badet in Aphrodite (1906).

Photo 9. Isadora Duncan in Ave Maria (1914). Photo by Arnold Genthe. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Arnold Genthe Collection: Negatives and Transparencies.

The resemblance between Badet and Duncan is uncanny, and perhaps more than coincidental. While there is a distinct difference between the plots of the two works, and Badet's more mimetic arm position (as if she is lifting or carrying an object) compared to Duncan's lowered elbows and relaxed wrists (a praise, or despair, gesture), there are clear similarities between the Badet spread and photographs from Duncan's later work (Manning Reference Manning1993, 34–37). Although Mariquita and Duncan shared movement vocabularies and some methodologies, Duncan set her work apart through writings and speeches as well as through her choices of dance subject, costuming, and movement vocabulary. By diminishing the erotic and exotic aspects of her dances discursively, Duncan further differentiated herself from the numerous scantily costumed nymphs, satyrs, and bacchantes on the public stages.

Distancing Queer Eroticism: The Case of Eva Palmer

Isadora Duncan attended the private salon and knew Barney personally, but in her autobiography, she claimed to be ignorant of the exact connection Barney and her comrades formed between antiquity and queer subjectivity. Duncan's denials of intentionally eroticizing Greek performance are not convincing.

Duncan associated with the important group of lesbian upper-class patrons of Paris. But was Isadora Duncan representative of this homoerotic Graecophilia? Duncan herself made sure (à la Daly's aesthetics of exclusion) to distance herself in many ways from some of this group's activities. Most pointedly, she demonstrated this in her description of the 1900 debut chez Elisabeth de Greffulhe. “The Countess hailed me as a renaissance of Greek Art,” wrote Duncan in her autobiography, “but she was rather under the influence of the Aphrodite of Pierre de Louÿs and his Chanson de Bilitis, whereas I had the expression of a Doric column and the Parthenon pediments as seen in the cold light of the British Museum” (I. Duncan 1927, 60). Duncan's published recollections of this event, twenty years after the fact, conveniently distance the dancer from the salons by claiming ignorance of their erotic sensibilities. Later biographers have also relied on this passage to purge Duncan of sexual impropriety. In his biography of Duncan, Peter Kurth notes that she had read the works of Sappho along with Louÿs's ravishing lesbian poetry; however, he writes “the lesbian sensibility went right over her head” (Kurth Reference Kurth2001, 74). Duncan herself wrote:

The Countess [de Greffulhe] had erected in her drawing-room a small stage backed with lattice, and in each opening of the lattice work was placed a red rose. This background of red roses did not at all suit the simplicity of my tunic or the religious expression of my dance, for at this epoch, although I had read Pierre Louys [sic] and the Chansons de Bilitis, the Metamorphoses of Ovid and the songs of Sappho, the sensual meaning of these readings had entirely escaped me, which proves that there is no necessity to censor the literature of the young. What one has not experienced, one will never understand in print. (Emphasis mine; I. Duncan 1927, 60)

She was “still a product of American Puritanism,” after all (I. Duncan 1927, 60); however one could not read Louÿs's Chanson de Bilitis without noting the sensuality. Unless, Duncan was literally a child when she read these poems describing in voyeuristic erotic detail the ways in which Bilitis and her female companions made love, she could not have missed some eroticism there. Even if she read them in a watered-down English translation (such as the private pressing translated by Alvah C. Bessie's in 1926), or early on in her French education, the language is simple enough; moreover, the majority of these editions had illustrations. For those who might not have caught the subtlety of the poetry, erotic drawings of Bilitis and her companions graced the opposite page. In the poem, “Les seins de Mnasidika,” for example, Louÿs unambiguously depicted a homoerotic scene between two women.Footnote 17 Louÿs's writings were not something one would pick up at the local bookseller on the Seine on a whim. Les Chansons de Bilitis was a book one sought out, bought, and read privately (Barney Reference Barney and Gatton1929, 32). Lastly, one cannot overlook that these poems were the talk of all of Paris. Louÿs's Bilitis showed his readers his own Orientalist fantasy of what women are capable of doing in private without men.

Unlike Maud Allan who found herself permanently branded as decadent, treacherous, treasonous, and Sapphic due to her “highly erotically charged” Greek and Salome dances, Duncan successfully fought to quiet similar charges (see Koritz Reference Koritz and Desmond2003, 135; Macintosh Reference Macintosh and Macintosh2010, 192–197). Duncan's claims of ignorance can only be read as a way to separate herself from Barney and the “Greek” performances in her garden. In this venture, Duncan was not alone; Barney's close friend, Eva Palmer, similarly used her unpublished autobiography to create distance between the dancer's early theatrical work in Paris and Barney, the “Queen of the Amazons.” Like Isadora Duncan, Eva Palmer-Sikelianos used autobiography as a public universalizing and distancing medium to divert attention from her private life.

Palmer, the daughter of a wealthy New York City family, spent her childhood summers in Bar Harbor, Maine, with Natalie Barney. The two women shared a fascination with ancient Greek literature and culture as well as an interest in amateur theatricals. When Palmer moved to Paris, she spent enough time in Natalie Barney's garden to establish a reputation for homoerotic ancient Greek performance. However, by 1938, when she began writing her autobiography, Eva Palmer's narrative of her own vision of antiquity had become fraught with artistic anxiety and she intentionally distorted her biography to distance herself from her youthful ideas and associations (see Albright Reference Albright2007; Leontis Reference Leontis, Kolocotroni and Mitsi2008; Palmer-Sikelianos Reference Palmer-Sikelianos and Anton1993). Ironically, her autobiography is not really a biography at all. As John P. Anton writes, “Ultimately, Upward Panic is more the biography of an idea than the autobiography of a person …” (Palmer-Sikelianos Reference Palmer-Sikelianos and Anton1993, xii). In this way, Palmer's and Duncan's autobiographies took up similar missions. Both attempted to promote a universalizing conception of art rooted in Greek thought partly in order to smooth over questionable activities in their private lives.

Unsurprisingly, Eva Palmer distanced herself not only from Barney but from Isadora Duncan as well. For Palmer, Duncan's dance (unlike the work of Duncan's brother) corrupted and distorted the true art of Greek antiquity. She noted how Duncan's body always flowing, fell into curves—rarely were there the pauses or straight hard angles, which Palmer deemed authentic to true ancient Greek dance (Palmer-Sikelianos Reference Palmer-Sikelianos and Anton1993, 181–82). Later, Palmer discussed Duncan's work pejoratively as Dionysian due to her Nietzscheian obsession with the music of Beethoven, and even blamed Duncan for her children drowning due to her refusal to listen to warnings sent to her by the gods (Palmer-Sikelianos Reference Palmer-Sikelianos and Anton1993, 185 and 187–88).Footnote 18

Earlier, however, Palmer focused her ire on Barney. Discussing Barney's salon and the famous frontispiece to her Aventures de l'Esprit (see Photo 2 again), she listed two dozen names from the map, burying Duncan's name somewhere in the middle and pulling out some less notable names from the bottom of Barney's map to the top of her list—archaeologists (the Reinach brothers, Salomon and Théodore), for example. As for Barney, Palmer painted her as an unfairly cruel individual who relished in her mistreatment of others.Footnote 19

Palmer devoted multiple sections of her book to Barney; however, the author buried them within other sections, and refused to title a chapter “Barney” despite their years of friendship. While chapter 5 of Palmer's autobiography is almost exclusively about Natalie Barney, she titled it “Paris.” Chapter 6, however, concerns a very long discussion of weaving fabric to retain the types of folds seen in Greek statuary, Palmer's troubling friendship with someone we can only assume to be Barney, and finally, Palmer's introduction to the Duncan family. Nonetheless, this chapter is titled “Penelope” (Raymond Duncan's wife).

The extended section concerning the unnamed friend who we can assume to be Barney begins with a lengthy discussion of a potential theatrical engagement with the London stage actress, Mrs. Patrick Campbell, to take part in a touring production of Pélléas et Mélisande in the United States and Britain. This tour was ultimately cancelled due to Campbell's reservations about one of the aspiring actress's friends. Palmer wrote:

Presently, however, it appeared that there was a condition attached to Mrs. Campbell's proposal. She made it clear that, in order to act with her, I should have to give up a friend of mine in Paris of whom she disapproved. What she objected to was an occasional theatre or dinner engagement, or a ride or drive in the Bois de Boulogne. I was not living with this person, and Mrs. Campbell knew it. She was quite explicit about the fact that she considered my personal behavior exemplary, but that I was careless about the people with whom I was seen, and that this carelessness was bad for my reputation. I suggested that when she and I would be acting together we would undoubtedly be either in England or in America, that therefore these dinner and the tea parties in Paris which she objected to would automatically cease, so what difference did it make to her if I continued to maintain friendly feelings toward this person whose name she had brought up?

“No,” she said. “There must be no friendly feeling, and there must be no correspondence; there must be an open and permanent break if you are to act with me.” (Palmer-Sikelianos Reference Palmer-Sikelianos and Anton1993, 44)

Palmer brushed off the request, noting that her friendship with this individual was not a matter of “life and death.” In the end, though, Palmer declined Mrs. Campbell's offer and remained loyal to her anonymous friend. This proved ultimately unnecessary as Palmer soon moved to Greece with the Duncans (Raymond and Penelope) and dedicated her time to creating the first modern Delphic Festival.Footnote 20

While this friend remains unnamed in the text (surprisingly, the editor does not venture to guess who it might be), it is quite clear that individual who was “bad for [her] reputation” was none other than Barney. All of the clues point to the “Amazon,” especially the reference to the Bois de Boulogne, the rendezvous point for courtesans such as Liane de Pougy (Barney met Pougy there for the first time) as well as a favorite spot for lesbian women to gather and seek partners (see Erber Reference Erber2008, 181–182; Taxil Reference Taxil1891, 263).

The story demonstrates that the activities of Barney and her friends had not escaped Mrs. Campbell, and that involvement and association with this openly lesbian company could severely hamper one's chances of gaining access to more professional theatrical, dance, and musical opportunities. For women like Duncan and Palmer who occasionally took part in lesbian social activities, public distance in autobiographies and personal associations soon became necessary for career development.

One can then reasonably assume that Duncan, like Eva Palmer, knew about the full implications of this sensuality, and she knew that the women for whom she danced had first-hand knowledge of it too (as had she). Lurid stories inundated the newspapers, and rumors spread by word of mouth quickly on the streets and in the salons of Paris.Footnote 21 Yet the question remains: Did Duncan intentionally cater her dances to the lesbian spectators among her early private audiences? Was Barney's tale of Duncan's “finale” to the “Star-Spangled Banner” one of the many untold stories of Duncan responding to the sexual tastes of her audience? Her personal associations with the Princesse de Polignac and Natalie Barney, and later fervent denial of any sexual component to these relationships, demonstrate that her universal Hellenistic art was not entirely separate from the sexualized Greek dances of her Orientalist contemporaries.

When Daly writes that Duncan “… elevated dancing from low to high, from sexual to spiritual, from black to white, from profane to sacred, from woman to goddess, from entertainment to ‘Art’” (Daly Reference Daly1995, 16–17), she neglects to consider that while this might have been true for many Americans, some lesbian Americans in Paris may have seen her differently. Perhaps Duncan's later popularity with wealthy cosmopolitan American women was in part due to the leftover Oriental flavor of Greece portrayed in a new way: a dialectical understanding of not only past present and future, but of Orientalism and Hellenism, sexual and spiritual, black and white, profane and sacred, woman and goddess, and entertainment as Art.

Dancers such as Duncan and Palmer benefited from this early patronage and were not opposed to delivering a Cyprian flavor to Greece to please their audiences. To return to the possibly apocryphal story of Isadora Duncan's naked finale to the “Star-Spangled Banner,” we need to ask what hides beneath Duncan's tunic? Behind the “doric column” seen in the “cold light” of museums, some audiences hoped to catch a glimpse of the horny faun, the libidinous nymph, and the Sapphic scenes of youth written and performed across Paris. Duncan's later choreography may not have changed significantly due to her involvement with Parisian lesbian audiences, but it is clear that her attitude toward her dance changed as well as the ways she framed it for her audiences. This supposition should not be applied to every artist or to every aspect of Duncan's art. The conclusions we can draw from this case study are limited to the subjects involved and are primarily based on writings and receptions rather than on choreography. It would be inappropriate to generalize Barney's tastes to all lesbians, but we can conclude that Duncan was aware of her audience, which allowed her to cater her performances accordingly. In shaping receptions of ancient Greek dance in early twentieth-century Europe, we must accept the roles audiences played in encouraging and promoting their own fantasies of antiquity.

By accepting historical audience receptions into our narratives of dance scholarship, we simultaneously open the door to apocryphal stories, gossip, innuendo, hearsay, yellow journalism, and mediocre biography and history. Relying on “memory” does not differ too much from relying on “facts,” for as Paul Ricoeur reminds us, historical facts are nothing but recorded memories. Memory's duty then is to remain faithful—“to do justice, through memories, to an other than the self” (see Ricoeur Reference Ricoeur, Blamey and Pellauer2004, 89). With this in mind, how can we appraise the authenticity of performances of the past from the past? Simply: we cannot. Writing this type of history leads one through mazes of such questionable data. I have stumbled upon details of performances retold (often secondhand) by less than reliable sources; however, while what they say may never have actually happened, the fact that these people remember them that way is reason enough to include them in the reception and impressions of these artists and their works. Just because Barney remembers Duncan's dance as erotic and Duncan saw her art as universal does not mean that either was wrong, or that either was necessarily right. We can not surmise that Duncan was necessarily more popular with lesbian audiences than Badet or Palmer just because we have more responses from lesbian viewers to Duncan's work than her contemporaries (Manning Reference Manning1999, 3).

Despite her universalizing claims, Duncan's writings and performances illustrate an awareness of her audiences' unique tastes. Duncan's and Palmer's careers demonstrate that antiquity, not just Orientalism, could be used both as an erotic cipher, and a stamp of the lofty aims of the Greek classical tradition. Their success at manipulating antiquity to serve the tastes of the present leads us to ask how the seated audience might participate in the dynamic movements of the dancer on stage. Acknowledging the multiple ways Duncan performed “Greece” brings us closer to understanding the art of movement at the nexus of erotics, reception, and dance history.