1. Introduction

From the early modern period onwards, and at different times and at different paces, European countries witnessed the privatisation of common land, which by definition meant repealing collective rights of use over this land (e.g., grazing livestock, gathering fuel and other forest resources and even ploughing and cultivating). Historians have identified two processes that prompted this: first, ‘enclosure’, that is ‘ending the exercise of common use-rights over land, usually accompanied by the construction of a physical barrier around the land’; and, second, ‘privatisation’, understood as ‘the transfer to individual ownership of previously collectively owned land’.Footnote 1 In conceptual terms, communal property regimes thus took two forms: ‘operational’ rights and ‘collective-choice’ rights, each form allowing the exercise of different actions within a ‘bundle’ of rights. The right of access and the right of withdrawal or taking define use, whilst ownership also includes the rights of management, exclusion and alienation.Footnote 2 Taking this distinction into account, past research has revealed different possibilities for combining the exercise of the bundle of property rights by individuals and collectives. Table 1 summarises four alternatives. Individual use and ownership identify private property, the most extended formula, associated with the development of capitalism. The opposite is collective ownership and use that define common property. There are other interim options, too. Collective use over individual ownership was commonplace both in the British tradition, until the enclosure movement put an end to it, and in Roman Law countries, where such rights of use were known as profit á prendre (right to take) or servitudes (servidumbres in Spanish).Footnote 3 Finally, individual use over collective ownership can also be found, for instance, when communal pastures were leased to stockbreeders in short-term contracts, or when communal land was distributed for individual cultivation as allotments in a long-term scheme. These cases involved a sort of individualization without privatisation.Footnote 4

Table 1. A conceptual framework for the commons: typologies of land according to ownership and use rights

Until the 1980s, historical narratives tended to describe the processes of enclosure and privatisation (i.e., equalising individual use-rights and ownership) as necessary companions to modernisation and economic growth. For North and Thomas, for instance, the transformation from communal to private ownership was the inevitable outcome of the increase in population, prices and rents, which led to a more efficient organisation of the economy through a better design of incentives.Footnote 5 It seemed to be a linear, inexorable fate, as in a Greek tragedy. However, common lands did not totally disappear in Europe, and far from being a footnote of ‘rare and curious miniatures of archaic character’, their survival in industrialised countries defies simplistic explanations.Footnote 6

Since the mid-1980s, there has been a shift in the consideration of common property regimes. Interdisciplinary approaches to the question of sustainability and a second generation of New Institutional Economics have provided a renewed perspective on long-standing communal organisations. These studies contend that a certain degree of social and ecological efficiency has allowed communal arrangements to survive for centuries, and have sought to understand their rationale.Footnote 7 The reappraisal of the common property regime in the social sciences has also had a parallel in historiography. Numerous works published over the past two decades provide a renewed narrative that dismisses the old stereotype of mismanaged residual property.Footnote 8

In the narrative that emerges from these studies, the process of dismantling common property regimes is not a natural consequence of demographic and economic growth, but instead the outcome of social interactions and political struggles in specific historical contexts. This was already the perspective adopted by influential Marxist historians, such as M. Bloch and E. P. Thompson.Footnote 9 If there are confrontations among social classes and corporations in defence of one or other solution, then the outcome may depend on the correlations of existing forces in each case and on external determinants, with no preconceived notions or linearity. This explains the uneven and limited process of privatisation that took place in several parts of Europe before the eighteenth century, derived from clashes between feudal lords and peasants or between neighbouring communities, as well as from the financial problems of local councils, aggravated by wars.Footnote 10

Between 1750 and 1900, as Demélas and Vivier stress, the nature, intensity and extension of this process totally changed, because the new economic thinking of physiocrats, agronomists and liberal thinkers provided an ideological platform for privatisation, and the modern state assumed the role of catalyst. The attacks against collective property rights, reinforced by doctrinarian notions and the rule of the State were widespread and effective, although not wholly successful at first. The dismantling of the common property regime needed several rounds of legislative and executive actions in most European countries.Footnote 11 This is a symptom of the existence of different projects for the commons within rural society, as well as of changing situations depending on the political and economic context. Vivier and Brakensiek have shown, for France and Germany, respectively, the plurality of regional trajectories in countries where communities were governed by similar legislation. Both highlight the fact that rivalry and the correlation of forces within different communities could either delay or accelerate the privatisation process and could explain the persistence of old attitudes towards the land.Footnote 12 Demélas and Vivier have also avoided the simplified and long prevailing image of a top-down impulse from governments, intellectual elites and great landowners. State-centric narratives cannot therefore properly reflect the complexity of a process whose main feature is the diversity of social contexts and results.

In the case of Spain, the General Disentailment Law of 1855 (Ley de Desamortización General), also named Madoz's Law after Pascual Madoz, Minister of Finance, has been considered the start of the privatisation process. The law was justified by the need to suppress the obstacles to economic development and pave the way for public wealth and well-being. More specifically, the law sought to mobilise the land market, while at the same time resolving the State's financial problems and facilitating the building of railways. Municipal lands were sold at public auction, with the State retaining 20 per cent of the sale price and the other 80 per cent being delivered to the municipalities in the form of public debt securities.Footnote 13 Research conducted from 1980 onwards, however, has revealed that the process of privatisation began much earlier than 1855 and operated in several ways, including the distribution of allotments among rural labourers and decommissioned soldiers from 1766 to 1854, and the enactment of enclosure legislation (acotamientos in Spanish) by the Cadiz Parliament (1813).Footnote 14

There are no countrywide data on the volume and pace of the privatisation process during the first half of the nineteenth century or for individual provinces, but Navarre is probably the most documented regional case so far. Figures are given for Navarre as regards the sale of lands arranged by local councils during the Peninsular War and its immediate aftermath (1808–1820), as too for the sales made by the Spanish government from 1862 onward pursuant to the General Disentailment Law of 1855.Footnote 15 What we are still largely unaware of is the amount of land alienated between those two dates. This article fills this lacuna for one of Spain's 50 provinces, by trawling through the sales made between 1820 and 1855, which provide an overall view of the privatisation process and a better understanding of its implications.Footnote 16

Common lands in Navarre had different profiles. As in other Spanish regions, most of these lands were controlled by municipal corporations, and only a registered resident in the village (vecino) was entitled to full access. These lands were legally classified into two types: those that were regularly leased and provided cash income for the municipal coffers (bienes de propios, or ‘patrimonial assets’), and those that were freely used by local people under council stewardship (bienes de aprovechamiento común, or ‘communal assets’). In practice, however, these uses were not so clear-cut. Municipalities in dire financial straits often changed the assets’ purpose to obtain income from their lease. Some communal assets therefore changed their legal status and were considered patrimonial assets. In other cases, there was no formal change in status, but instead a duality of municipal accounting, with separate ledgers for patrimonial assets (ramo de propios) and communal assets (ramo vecinal). These changes did not usually affect all the other possible uses. For instance, for reasons of financial imperative, the pasture of a communal asset could be leased by the highest bidder in an auction for a short-term contract, but local people could still forage for firewood and acorns, hunt game and quarry stone, for example, or practice seasonal cultivation. In order to facilitate the management of these lands and their use as extensive pastures for livestock, they were usually divided into large plots that were known by different names, such as dehesas, ejidos or, in the case of most of Navarre, corralizas.Footnote 17 Common meadows (prados) were reserved for working animals (oxen, horses and mules), combining grass with the planting of riverside trees. These plots were not physically enclosed, but their boundaries were clearly defined (with markers) and enforced by local stewards.

This article's aim is to report certain findings from a regional perspective to formulate a narrative on the privatisation process of common lands in which local agency and non-linearity nuance the traditional importance attributed to state-centric and irreversible development outlines. The starting point here is to consider communal regimes from a multifunctional perspective, whereby the logic of these systems of organisation that linked natural resources, peasant communities and political powers tended to guarantee the reproduction of structures that were hierarchical and unequal to different extents. In short, it is understood that the communal regime did not necessarily operate in an egalitarian manner, nor did it guarantee the subsistence of the rural poor, unless the specific arrangement of internal power relationships derived from access to the land, among other factors, pushed in that direction.Footnote 18 The notion upon which this approach is based is that of equilibrium, an unstable one, or better still, an uninterrupted succession of limited equilibria.

This study is based on a detailed examination of exhaustive notarial records and other supplementary documents, such as municipal accounting ledgers, legal proceedings and administrative papers. The article is organised into two sections: the first carefully examines the process of privatising the commons in Olite, a small town in the heart of the province of Navarre, while the second ups the ante to address the phenomenon from a regional perspective. Without forgoing the long-term approach, the greatest effort focuses on the period 1820–1860, which is hitherto little known. It is the prelude to the State's direct intervention of communal assets that was enacted in Spain in 1855 through the Madoz Law, but which did not begin to take effect in Navarre until 1862. The main focus of study here, therefore, is the decentralised process of privatisation that responded to the extraordinary circumstances that displaced the old equilibria, introduced the need to find unique solutions, modified the relationships of power that lay at the heart of the rural community, satisfied individual appetites and expectations and led to further conflicts and solutions.

2. A town in the eye of the storm: Olite, 1808–1854

In the book, The Fatal Knot. The Guerrilla War in Navarre and the defeat of Napoleon in Spain, John L. Tone writes:

Wherever the communal and municipal lands were alienated, the result was poverty, depopulation, and social violence, as exemplified in the case of Olite. Beginning in the War of Independence, Olite´s town fathers sold off practically all the city's lands to pay off war debts. A few big landowners, who promptly removed themselves from the city and became absentee lords, came to control the local economy, and as a result, Olite lost population during the nineteenth century. It was only after a long and bitter struggle that the community recovered some of its assets.Footnote 19

The town of Olite is, indeed, the paradigmatic case in Navarre of the disposal of communal lands during the nineteenth century and of the social struggles to recoup those selfsame assets between 1880 and 1936. The protests of October 1884, which led to the death of four local people, shattered the peace and quiet of provincial life, highlighting the problem of peasant access to the land. In March 1885, in response to the Comisión de Reformas Sociales (Social Reforms Committee), reference was made to Olite, albeit without actually naming it, ‘as a historic town in Navarre, where Spain already knows that certain class struggles turn into bloody conflicts’.Footnote 20 The struggle for the lands escalated again in 1908, with occupations of estates and bitter legal wrangles, culminating in 1914 with another uprising, with the outcome this time being three people shot dead by the Civil Guard and court-martial proceedings. Following these episodes of protest and repression, negotiations between owners and the council enabled the latter to recover 1,101 hectares of commons in 1885–1887, and 284 hectares in 1916–1918, which were immediately divided into plots and distributed among the local people for their cultivation.Footnote 21 Again in the 1930s, the desire for agrarian reform led to further popular mobilisations, which were crushed by the repression following the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, with the outcome now being the murder of 45 local people by the fascists.Footnote 22

The interest here, however, does not involve analysing these struggles for the land that characterised the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but instead in understanding the nature of a privatisation process that had left too many loose threads. Martin Blinkhorn was already aware of this when stating the following:

properties acquired as a result of disentailment, or the alienation of ‘corralizas’, or both, were regarded by smallholders, tenants and labourers as the fruit of greed, dishonesty, the abuse of power and downright theft. Such attitudes were encouraged by the extraordinary complexity of the customary and contractual rights attached to ‘corralizas’, and by the ambiguities often surrounding the terms upon which ‘corraliceros’ had acquired them.Footnote 23

What is meant by these ambiguities in the deeds of purchase? Why wasn't privatisation undertaken in an unequivocal and unquestionable way? A study of this town's experience may help to answer these questions.

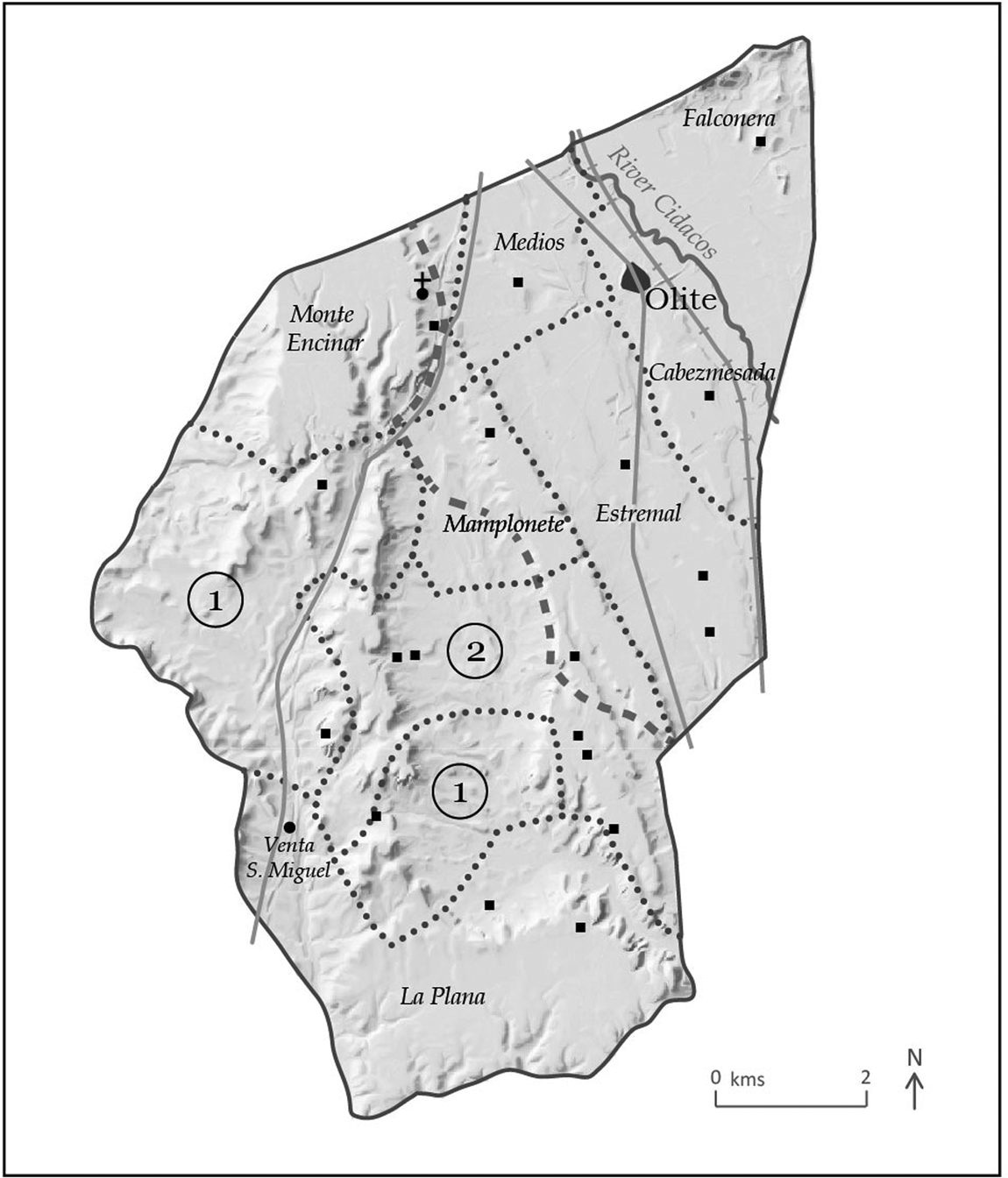

As a seat of the royal court in the Late Middle Ages, from 1407 to 1836, Olite was the capital of one of the Kingdom of Navarre's five administrative districts (merindades), and in 1630, it even purchased a Royal Charter granting it the grand status of ‘ciudad’ (city), even though its population in 1787 amounted to no more than 1,488 people. Although it was a large jurisdiction (83.2 km2), agricultural land in 1818 accounted for only 29 per cent of the municipal area (2,390 hectares).Footnote 24 The remaining 71 per cent was used for grazing cattle and sheep, with some woodlands of Mediterranean evergreens (Quercus ilex, Q. faginea, Q. pubescens). Most of this uncultivated land belonged to the municipality, either owned by the council (bienes de propios) or by the local people (bienes de aprovechamiento común), being organised into different units of use and management: corralizas (pasture estates) and prados (meadows).

This distinction between ‘patrimonial assets’ and ‘communal assets’ meant that their management involved two separate bookkeeping arrangements; in the former case involving a de propios y rentas account, and in the latter, an efectos vecinales account. The latter recorded the income obtained by the council through the annual sale of certain easements (the grass from Monte Encinar, where the firewood was gathered free of charge by the locals, and the manure collected from several animal enclosures), which towards the end of the eighteenth century were used to finance certain expenses that benefited the local community, such as the wages paid to teachers, the midwife and the doctor, the repair of streets and paths, or the planting of riverside trees.Footnote 25 As for the de propios assets, their management was more complex. Part of the corralizas considered to be de propios were leased to the local guild of sheep farmers (mesta) through an agreement that was renewed every six years. In 1827, the following retrospective explanation was provided:

From a long time past until the years of wars and revolutions, the livestock farmers of Olite were accustomed to leasing the corralizas belonging to the town by paying the sums that were agreed between the farmers and the town itself, with prior permission from the Real Consejo de Navarra (Royal Council of Navarre), which granted it for six years, and in the year it expired it was extended, which meant it never came to public auction, because the town and the court of the Real Consejo de Navarra considered it highly appropriate that the farmers with their sheep should use the corralizas by paying the fair price, as otherwise many ills would be caused, especially in the time of the shearing, as not being guaranteed local pastures they would incur very high costs in collecting the wool, which would mean that because of these hardships the community would be left without sheep, seriously inconveniencing agriculture (upon which this community depends) because of the lack of manure.Footnote 26

There were 12 corralizas, each one designed to hold 450 head of sheep, which the farmers’ guild, the mesta, was responsible for distributing among its members for the winter, and for which an agreed rent had to be paid. Between 1784 and 1805, it amounted to 729.50 reales de vellón (rvn)Footnote 27 per corraliza and year, being increased in the latter year to 1,164 rvn (a 60 per cent increase), before falling to 834 rvn in 1812. In 1805, the agreement between the town and the guild of sheep farmers was extended to include the use of the large wilderness of La Plana, in the far south of the municipal area, for 3,126 rvn, which was added to the 13,968 rvn that the guild paid for the 12 corralizas. In addition, in 1806–1808, the town also charged the guild 2,710 rvn for the lease of the summer pastures (from 29 June, St. Peter, to 29 September, Michaelmas), reserved for the lambs that would not survive the trashumancia, the seasonal migration to the summer pastures in the mountains. The arrangement of these easements required the head of the guild to draw up an annual list of its members (29 in 1807 and 1809, and 25 in 1812) and of their livestock (7,882 heads in 1808, and 6,387 in 1812) and submit it to the local council. Three more corralizas (Cabezmesado, Corral de Medios and Mamplonete) fell outside this arrangement, being used by the council to collect funds by auctioning them off to the highest bidder for three-year periods (5,586 rvn in 1803–1805, and 8,044 rvn in 1806–1808). Finally, one corraliza (Estremal) was set aside for the flocks pertaining to the municipal slaughterhouse, whose administrators paid an annual sum of 4,168 rvn under that item between 1805 and 1811. All-in-all, the local council and the people of Olite accrued a substantial revenue (22,676 rvn in 1805, and 40,308 rvn in 1807) for ceding the right to exploit the pastures according to two formulas: the direct assignment for an agreed price to two players of strategic value, namely, the local guild of sheep farmers and the municipal slaughterhouse, and the public auctioning to the highest bidder of three corralizas de propios and a communal one.Footnote 28 The municipal scrublands also provided other income, such as that accrued annually by the auctioning of manure from the animal enclosures (4,110 rvn to the de propios municipal account in 1805, and 3,293 rvn to the communal or vecinos account), and the amount collected from the sale of the trimmings from pruning holm oaks (306 rvn that same year).

At the end of the ‘Ancien Régime’ the commons provided the local people not only with pastures for their working livestock, firewood for household consumption, and the foraging of different fruits, but also regular income that paid for a broad range of expenses (Table 2). This annual income also served as collateral for securing council borrowing. In 1805, the communal or vecinos account was burdened with eight loans (censales) for a combined capital of 80,450 rvn, while the corresponding sum in the case of the de propios amounted to 281,535 rvn in fourteen loans (three of them arranged that same year at 4 per cent interest, compared to the rate of 2 per cent for the previous ones), and 41,684 for the municipal slaughterhouse. The level of borrowing, therefore, was already high (403,669 rvn), and the cost of servicing the debt amounted to 9,588 reales de vellón per year, a figure that seems manageable when one considers the amounts accrued through the leasing of pastures.

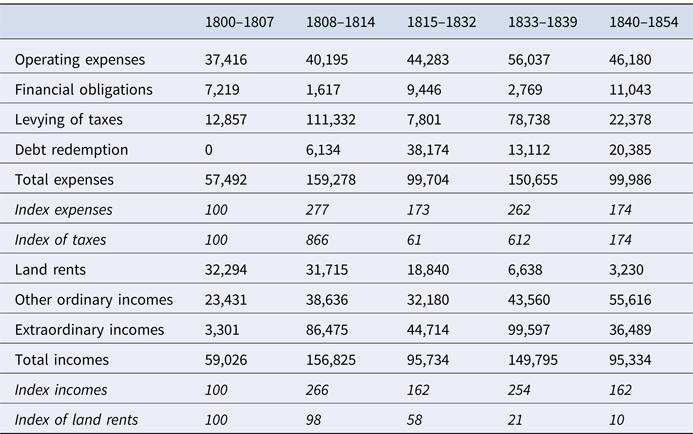

Table 2. Municipal expenses and incomes in Olite, 1800–1854

Notes: Municipal expenses and incomes. Annual average expressed in ‘reales vellón’ (rvn) at current prices. This includes three sets of separate accounts: the depository of municipal property, Propios y Rentas (1800–1854), communal property Efectos Vecinales (1800–1811, 1815–1820, 1822–1831, 1834–1842) and council taxes, Contribuciones (1818, 1823, 1825, 1833–1835, 1839, 1846, 1851).

Sources: Archivo Municipal Olite (AMO), books 60, 78, 82, 89; ARGN, Consejo Real de Navarra, boxes 36627, 36628; ARGN, Diputación Foral, boxes 49133–49136, 49140; ARGN, Protocolos, Olite, Joaquín Erro, boxes 8391 (143), 8396 (76), 8398 (144), 8406 (43, 82), 8407 (78–81), 8408 (20, 33–35), 8415 (14).

This scenario, already subject to tensions, as revealed by the steep increases in the prices of grasslands and the aforementioned interest on capital, was suddenly turned upside down in 1808 by Napoleon's military invasion and the outbreak of the Peninsular War. Olite's location on the main road from Pamplona to Tudela, and from those points toward France and Zaragoza, made it a staging post for troop movements, whereby on 11 October, the town council declared that ‘for many months the town has been supplying the French troops with provisions and for that reason all the branches upon which it depends have been completely exhausted, and for the past twenty days over four thousand men have been billeted there’.Footnote 29 The extent of these military demands over the next seven years both in kind and in cash far exceeded anything that had been experienced before (Table 2), with the ensuing repercussion for the council's coffers.Footnote 30 The extraordinary means used to deliver the rations in kind and the cash demanded by the occupiers involved unprecedented measures that subverted the old order, such as the imposition of levies on the privileged (the Marquis of Feria, the Bishop of Barbastro, and parishes of San Pedro and Santa María), or the seizure and sale of properties and silver from churches and convents.Footnote 31 The council summed up the urgency and confusion involved in meeting the tax requirements imposed by the occupying authorities and their troops in the following terms in 1818:

That in recent wars, and specifically because Olite is on the royal highway, it incurred such excessive costs through the presence of the French troops that, as these could not be met by the demands they made for sharing them out among the local population, households were called upon individually to make an increasingly greater effort in the financial expectations required of them, without keeping to the order that justice requires in fairness, and for the same they were given their promissory notes throughout the town; this has given rise to the case that the same people are pestering the town to pay from its coffers those advances or loans, whereby it is incurring numerous expenses.Footnote 32

In short, the long-term municipal debt (censales) was increased by a huge volume of short-term borrowing in the form of local promissory notes for supplies and advances (calculated in 1814 to amount to more than 512,000 rvn), besides other sums due, such as that owing to the segment of tradesmen in Pamplona for payment of the contribution foncière of 1812 (84,673 rvn).Footnote 33 Faced with the prospect of the depreciation in value of such a vast number of promissory notes, the creditors (both large and small) saw the need to transform them into tangible assets, whether cash, land or other property. Therein, the pressure on successive councils from different sectors in the community to convert these debts into ready cash.

Yet who made up the council? Until then, the members of the town hall had been chosen each year by drawing lots from three separate bags or sacks that held a certain number of names for the election of the mayor, four councillors to represent wealthy families and two more to represent the less fortunate. This system, known as insaculación, provided a varied social representation on the local council (see Figure 1, in which councillors’ wealth was expressed as a multiple of average tax wealth). This system was suspended in 1810 (when the Viceroy annulled the election and handpicked wealthier people for the office), in 1814 and 1820 (when the ephemeral constitutional regime introduced indirect suffrage by the two parish assemblies). Indirect suffrage permanently replaced the lottery system from 1837 onwards, after the promulgation of a new liberal constitution.Footnote 34Figure 1 shows the cycles in which the appointment of councillors seems to have favoured the common people (1816–1819, 1824–1830, 1854) and others (1810–1812, 1815, 1820–1823, 1843–1852) when the wealthy prevailed.

Figure 1. Social composition of Olite's town hall (1800–1855). Members' wealth as a multiple of average tax wealth.

The sale of municipal property as a way of paying off the debt began in 1810, following a pattern that apparently sought to uphold the existing status quo. The process involved measuring, valuing and auctioning 28 plots of 0.54 hectares each for growing crops at Prado Fenero, which were purchased by 10 buyers.Footnote 35 In addition, and foreseeing a possible alienation, instructions were given to value one of the corralizas de propios (Cabezmesado), explaining that the value of 172,200 rvn did not involve full ownership of the plot because ‘it consists mostly of lots of land that belong to the local people’, but instead only the right to exploit the pastures. A valuation was also made (at 800,000 rvn) of the distant wilderness of La Plana, where the plan was to maintain the villagers’ right to collect firewood for household use (in which case the price would be only 576,000 rvn). Meanwhile, numerous plots of land were sold off, most of which were already under cultivation. The aim of doing so was to regularise a de facto situation, permitting labourers to legalise their occupation, accepting as their method of payment the promissory notes on advances, and requiring the payment in cash solely of an eighth part of the valuation figure. Table 3 identifies the buyers of these lands by matching the names to a tax rating of the villagers conducted in 1809. This list classified the heads of the household into eight groups according to wealth, with an additional one for the poor. The bulk of the land bought (62 per cent) was concentrated into an intermediate segment on the scale (groups 3, 4 and 5). The richest (group 1) also played a major part (11 per cent), and even some of the least well-off were involved, albeit only on a sporadic basis.Footnote 36

Table 3. Olite, 1809–1826: Distribution of the buyers of common lands (except corralizas) according to the tax classification made in 1809

Note: Data in hectares and ‘reales de vellón (rvn) at current prices.

Sources: ARGN, Protocolos, Olite, Joaquín Erro, box 8378, no. 31, for the tax classification; Ibid. boxes 8378 to 8399, for the sales deeds.

A different profile applied to the purchase of grazing rights on the corralizas, which involved individuals in groups 1 and 2, as well as a number of non-residents. Cabezmesado was sold in 1812 for a sum (112,000 rvn) that was 35 per cent lower than its valuation figure, as the local council reserved the right to recover its ownership as soon as it repaid the money received (a formula known as carta de gracia perpetua (perpetual letter of grace) or pacto de retro (right of redemption)). Three individuals were involved in the purchase, of whom one (the Count of Ezpeleta) settled half the amount, paying a third in cash and the rest in promissory notes on advances made to the troops.Footnote 37 The following year saw the sale of two portions of La Plana to an outside moneylender for 147,316 rvn.Footnote 38 The third portion, including another corraliza (Venta de San Miguel), was ceded for 200,000 rvn to a consortium of 12 creditors (among whom was the aforementioned Count of Ezpeleta and four members of the mesta), who made a cash payment of 12.5 per cent of that amount, with the remaining 87.5 in promissory notes on advances. The final price for the three portions was 40 per cent less than the lowest valuation made in 1810. In 1818, the Count of Ezpeleta, who had held the office of Viceroy of Navarre since 1814 as the supreme authority in the Kingdom, approved a petition made by the parliament, the Cortes of Navarre, to legalise the sales made without the due formalities during the war, a short time before the Crown decreed the same thing for the whole of Spain.Footnote 39 In 1816, the Count's attorney had already sought to secure his ownership of Cabezmesado by offering 8,000 rvn to meet its valuation figure. The operation did not live up to his expectations, as when recovered and auctioned again, the corraliza was purchased by another outside buyer for 120,320 rvn, despite the official protest lodged by the Count's attorney.Footnote 40 Yet his intentions were soon fulfilled when the council recovered the three portions of La Plana in 1819 with a view to alienating them once again.Footnote 41 The auction held in 1820 reveals the interplay of alliances between local interests and outside players. The Royal Council of Navarre, the Consejo Real, had approved the sale, but on the condition that no loans were to be accepted as payment, solely cash. The bidding, which began 22 per cent below the valuation figure, was hard-fought between two outside investors, one of whom (the Count of Ezpeleta) had been purchasing property in Olite since 1798. Although a Basque called Miguel-José Iriarte submitted a better bid by promising to pay in cash, the Count garnered the support of several local people (belonging to groups 2, 4 and 5), who challenged the submission of that bid with the paradoxical reasoning that ‘if it were accepted it would mean that whoever had money could lay down the law’. After his final bid had been rejected, the Count ended up calling for the auction to be rendered null and void. When it was repeated, he was assigned the property in return for a payment of 680,000 rvn in cash and a further 200,000 rvn in the form of a 4 per cent loan in the town's favour.Footnote 42

Map 1. Olite (Navarre). Corralizas and arable land at the end of the 19th century.

This episode is enlightening for several reasons. Firstly, it testifies to the council's flexible use of a sale with the right of redemption to finance its extraordinary expenses without forgoing the possibility of recovering the alienated assets. Furthermore, it confirms the creditors’ interest in turning their promissory notes into more secure assets, such as land and buildings, but also cash in the event of applying the right of redemption. It also reveals the interest that some powerful outside investors had in exploiting the council's financial difficulties to build up their own large estates.Footnote 43 Political influence and the alliances forged with local individuals played a key role in this process of monopolising the land.

Even before the litigation arising from the previous indebtedness could be resolved, another armed conflict, this time a civil war, again sent costs and levies soaring between 1833 and 1839 (Table 2).Footnote 44 The council this time had official valuation data from the land register that enabled a fairer distribution of the tax burden, whereby in 1833, one-off charges were made at a rate of 11 per cent on the cadastral wealth, 56.50 per cent the following year and 25 per cent in 1835.Footnote 45 Nevertheless, the level of default in 1837 amounted to a fifth of the sum of those payments, which meant that other formulas were required, such as the sale of land for cultivation.Footnote 46 Once again, the efforts made to use municipal property to gather funds with which to pay for military provisions became a flexible alternative. In 1835, without permission from above and without resorting to an auction, the mesta's 11 corralizas (118,492 rvn), the two de propios (21,544 rvn) and the slaughterhouse's one (70,000 rvn) were all alienated.Footnote 47 The following year, the council created a new corraliza (Falconera, with a capacity for 400 head) on land that up until then had been used free of charge to graze local livestock, immediately putting it up for sale. The same applied to another one (Fontanaza, for 200 head) which had been used by a convent of monks until their expulsion.Footnote 48 In October 1836, the corralizas were recovered, although they were auctioned off again between March and June 1837. The income from the two corralizas de propios and the 11 belonging to the mesta amounted this time to 210,293 rvn, 50 per cent more than two years earlier, although on this occasion the amount paid in promissory notes accounted for 92 per cent of the total price. Those who acquired property rights over the pastureland in this way were mostly sheep farmers who had belonged to the former guild, which by then had been disbanded, and which had advanced livestock for provisioning the troops. Finally, between 1839 and 1841, with the permission of the provincial authorities, all these properties were consolidated, largely by the same bidders, settling the difference between the amount paid in 1837 and the value recorded in the auction. Outside investors saw their opportunity to exploit the council's weakness.Footnote 49 The best example of this involves the slaughterhouse's corraliza, recovered in 1836 and then sold off again in 1837 to Francisco Barbero, responsible for military provisioning in the nearby town of Tafalla, the new district capital, for a cash payment of 80,000 rvn. Once again reinstated to the council in 1842, it was auctioned off to a speculator from the province of Gipuzkoa (Miguel A. Amorena) for 166,346 rvn, which was paid in two bills of exchange. In both cases, the sale included the right of redemption (limited to 40 years on the second occasion) and the two conditions of allowing the pastures to be used for working livestock by the local people and of respecting any private crops already being grown.

The second post-war period brought certain developments, such as the full integration of the economy of the old Kingdom of Navarre within the Spanish market, and a particular form of political integration, which granted the provincial council, the Diputación, some room for manoeuvre in matters of local administration and taxation that was far more favourable than in other provinces (with these rights being referred to as the foral regime). The upward trend in the economy boosted the returns on land purchase investments, making this a much sought-after asset.Footnote 50

The problem of debt continued to be the main concern in the municipal administration, compounded by the fact that the short-term debt incurred during the war was raised by the deferment of the long-term debt, whose payment had ceased during the conflict (Table 2). In 1849, the council declared that it was overwhelmed by the accumulated default in the payment of interest. Being reluctant to cover its obligations through the distribution of levies on property wealth, arguing that ‘the local people are immersed in the greatest sorrow and destitution’, it asked the provincial authority to grant further permissions for the sale of land. This led to yet more sales of plots for cultivation on Prado Fenero, and the communal grasslands on Monte Encinar, valued at 90,000 rvn, were auctioned off, albeit with major restrictions for the buyer. These included limiting the use of grazing to a maximum number of livestock (800 rams or 1,200 sheep, with only those goats as required for leading the flock), a prohibition on ‘even the slightest’ tilling and the obligation to keep the livestock overnight in enclosures, leaving the manure for the town. The local people were also entitled to collect firewood (now in very short supply following the massive felling of trees throughout the century), hunt and graze their collective flocks from 1 December to 1 April. Three local livestock farmers attended the auction through their agent, bidding only 46,660 rvn, half the valuation figure. In spite of how low the bid was, the land was awarded to them. A new corporation successfully called for the annulment of the sale in 1854, based on the irregularities committed, and unsuccessfully looked for someone to advance them money on the rent. In view of the differences of opinions in the local council, the provincial council ordered the definitive sale of the land at public auction. That same year, it was bought for its 1849 valuation figure by three outside investors: a trading company from Tafalla (Arroyo, Ruiz & Zorrilla), a corralicero from the nearby town of Beire (Francisco Jaurrieta), and the widow of an ennobled military man (Countess of Espoz y Mina). The buyers again had to accept certain major restrictions, as the council held back certain rights for the local people, such as gathering firewood and hunting, as well as grazing their communal flocks from 1 November to 31 March.Footnote 51 The aim, therefore, was to make the privatisation of the most commercial exploitation compatible with the protection of those easements that guaranteed the local people's subsistence. It was a delicate balance that soon gave rise to frictions.

The social transformation process described here led to greater inequality. In 1818 (according to the lists of taxpayers), the Gini index (applied here to tax assessment values) stood at 0.634 (0.616 if we consider only residents); in 1834 it rose to 0.680 (0.649), in 1849 it reached 0.717 (0.684), and in 1860, it stood at 0.756 (0.730).Footnote 52 There is a need, however, to discuss some of the points made by John L. Tone that are cited at the start of this section. Mass privatisation did not lead to depopulation, as by 1887, Olite already had 3,071 inhabitants, doubling its 1787 population. Poverty was not strictly an issue either. It is true that a large number of households did indeed live on the poverty line because they lacked direct access to the land and depended on a daily wage at certain times during the farming year. Yet output had increased, as had the opportunities for work. The cultivated area had increased by 27 per cent over 1818 (3,043 hectares 1889), but this applied especially to the land taken up by vineyards (426 Ha in 1818 and 1,476 Ha in 1889), a labour-intensive commercial crop whose growth at the time was driven by French demand.Footnote 53

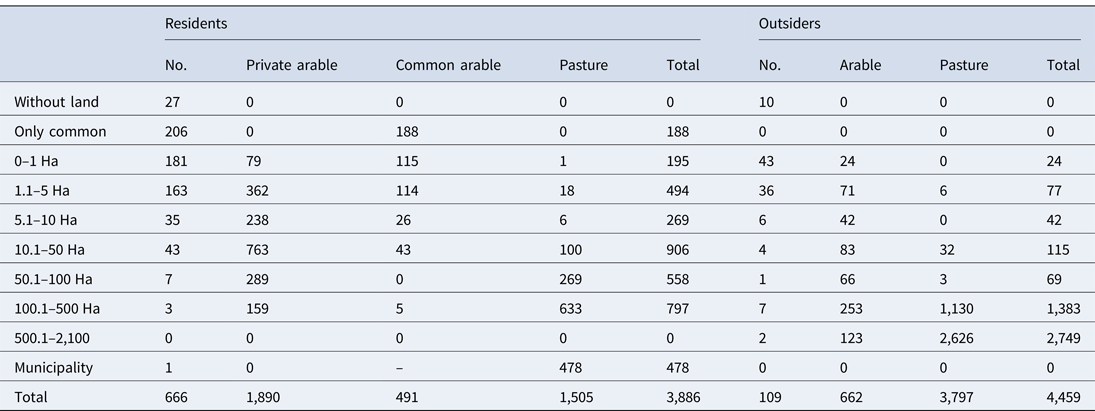

The fateful events of 1884 need to be understood within this context, defined not only by greater inequality, but also by the opportunities provided by foreign demand for wine and the lack of access to reserve land that could be used to extend the vineyards. Between 1885 and 1887, therefore, and as a consequence of the 1884 uprising, an agreement was reached between the council and the owners of certain corralizas that led to the removal of this obstacle, with the ensuing distribution among 492 local people (206 of whom had no other property) of small plots of land (0.90 hectares) for cultivation, a third of which were immediately planted with vines. Table 4 based on the 1889 tax assessment that lists taxpayers according to their place of residence reflects the consequences of the processes described. It reveals the unequal distribution of the cultivated land under private ownership (with a Gini index of 0.817 over land in hectares), the compensating effect of communal plots distributed in the recouped corralizas (which reduces the index for the entire surface worked to 0.695), and the size of the grazing area privatised between 1810 and 1854, a large part of which could be used for growing crops, in the hands of absentee owners (45 per cent of the total), whereby the Gini index for the entire area under private ownership rose to 0.927 (0.827 when taking into account the communal plots distributed a few years earlier).

Table 4. Land ownership in Olite, 1889

Note: Distribution of land ownership (data in hectares).

Source: ARGN, DFN, box. 7280 (16127).

3. Two steps forward, one step backward: reversible privatisation and institutional bricolage in Navarre

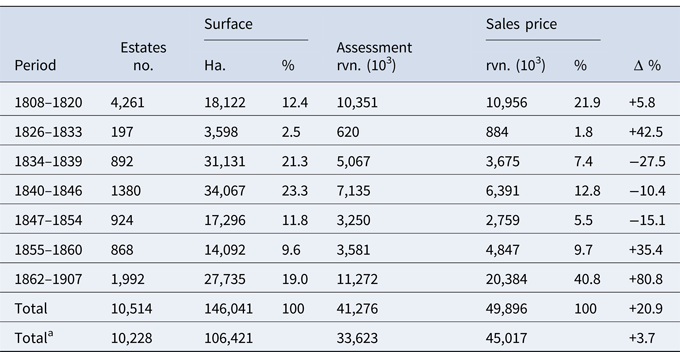

Olite is an extreme case in terms of the extent of the privatisation process, whereby one might wonder how far the rest of the province is reflected in this narrative. Table 5 provides a snapshot of the pace of privatisation in the province of Navarre between 1808 and 1907.Footnote 54 It includes data on the number of plots sold, the surface area involved, the valuation figure and the final sales price. The first finding is that the sales arranged during the stage instigated by the central government through the General Disentailment Law (1862–1907) involved barely a fifth of all the land under private ownership. Nevertheless, because these sales had taken place during a time of greater political and economic stability, and due to the competitive bidding at auctions, the property sold by the state amounted to 40 per cent of the final sales price (with its valuation figure at an intermediate point of 32 per cent). In other words, the sales made earlier by the local councils themselves, with or without the prior approval of the provincial authorities, accounted for over three-quarters of the surface area alienated, two-thirds of its valuation figure, and just over half of the final sales price. In short, decentralised privatisation in this province far outweighed centralised privatisation.Footnote 55

Table 5. Balance of the sale of municipal property in Navarre, 1808–1907 (current prices in thousands of ‘reales de vellón’)

Notes: where there was no prior valuation, I have assigned the sales price. Figures for 1862–1907, given by Iriarte-Goñi in constant prices, have been transformed into current prices using Sardá's deflator. Totala: ‘corralizas’ repurchased by the town halls have been excluded. The last column reflects the variation (in percentage) in sale prices compared to assessment prices.

Sources: De la Torre, Los campesinos, for the period 1808–1820; Iriarte-Goñi, Bienes comunales, for 1862–1907; J. Sardá, La política monetaria y las fluctuaciones de la economía española en el siglo XIX (Barcelona, 1998), 301–307. ARGN, PN (deeds pertaining to various notary offices: note 16) for the remainder.

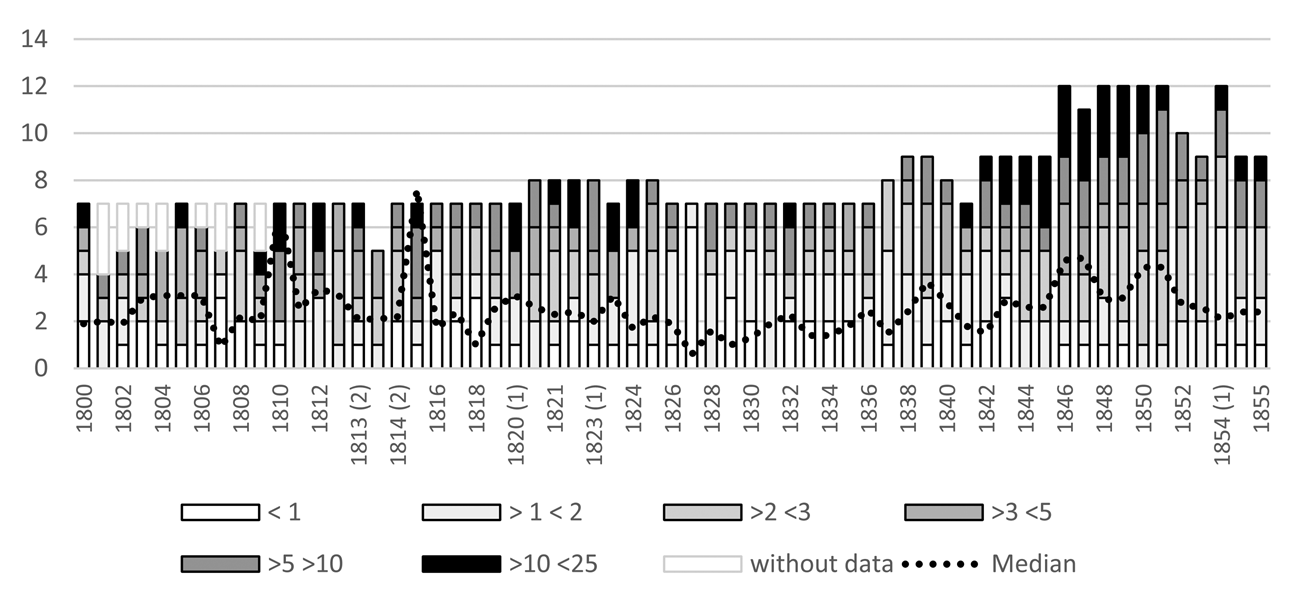

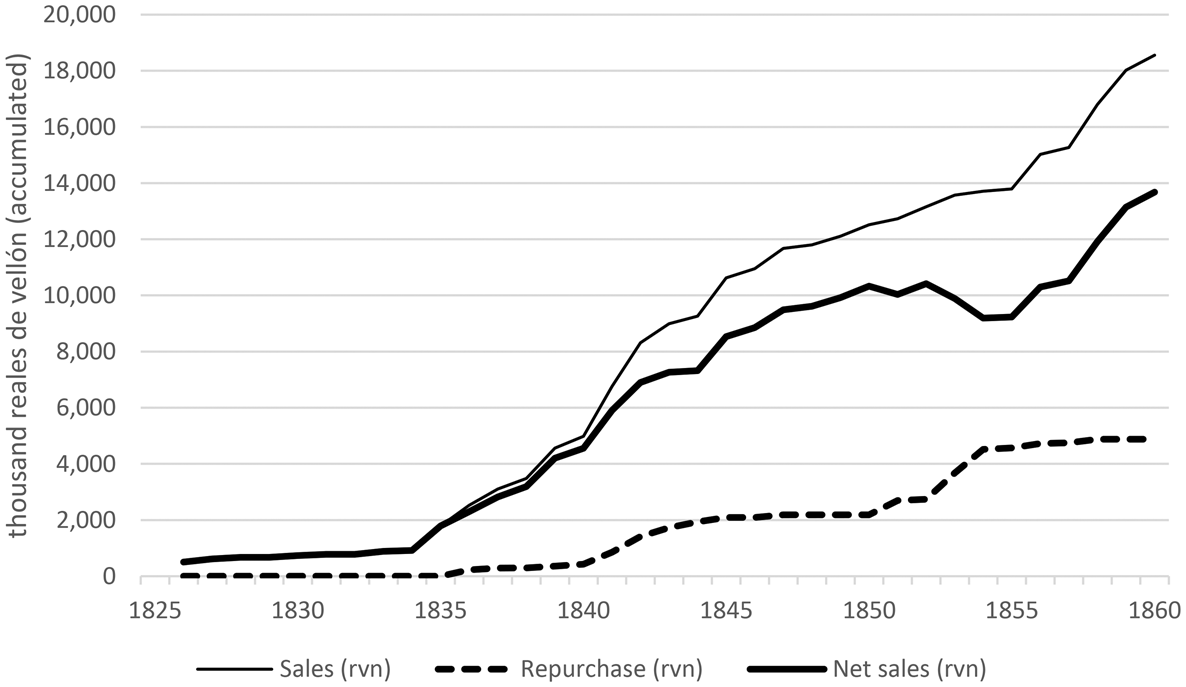

The quantitative importance of each one of these stages varies according to the chosen criteria – surface area or monetary value – as the final sales prices during the second quarter of the nineteenth century were, on average, below the valuation figure set by local surveyors. The most negative stage in this sense corresponded to the civil war years (1833–1839), when the final sales price was, on average, 27 per cent below the valuation figure. Selling below the valuation figure was common practice in those operations in which the local council reserved the right to recoup the property by reimbursing the price paid. Table 6 summarises the timeframe and volume of those sales of corralizas that used this credit arrangement between 1834 and 1860. The final balance shows that of the 256 corralizas privatised using this instrument, 197 were subsequently recovered, whereby the net balance was 59 plots and 12,426 hectares, with a value of just over two million reales de vellón. The arrangement was extensively used during the First Carlist War (accounting for 74 per cent of the revenue from the sale of corralizas between 1834 and 1839) and continued to have a major presence (46 per cent of those sold) in the post-war period, with its use becoming rarer as of 1847 (25 per cent of the corralizas sold in 1847–1854, and 10 in 1855–1860). As also revealed by the annual series of net balance of sales shown in Figure 2, not all the sales made during this period ended up becoming private property.Footnote 56 Privatisation was seen as a flexible arrangement for dealing with fiscal and financial commitments, although definitive and irreversible sales gradually prevailed.

Figure 2. Navarre (1826–1860): Sale and repurchase of common and municipal lands. Data in current reales vellón (accumulated).

Source: see endnote 16

Table 6. Navarre, 1834–60

Note: Balance of the sale of large pasturelands (corralizas) in carta de gracia (sale with right of redemption).

Sources: ARGN, PN (note 16).

a Percentage of carta de gracia sales over the total sales of corralizas (calculated by auction prices).

b Average deviation of the sale price over assessment value (%).

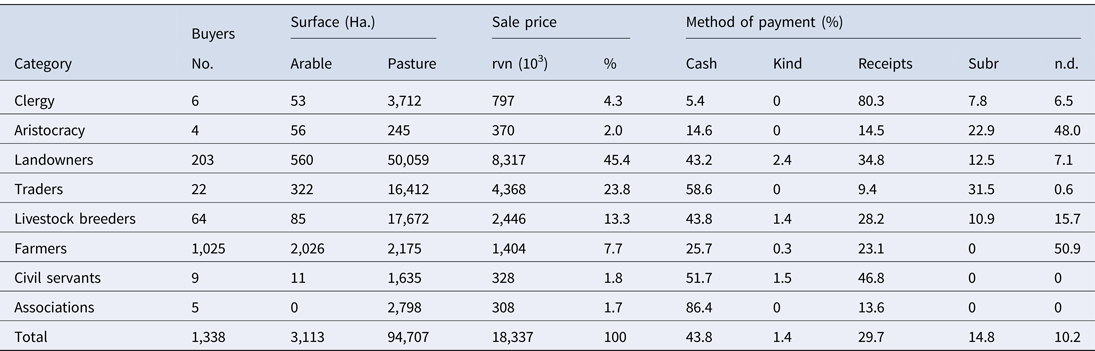

Table 7 shows the buyers according to their social position and the amount of land they purchased, as well as the method of payment they used. The buyer profile differs depending on whether we are referring to cultivated land or grazing plots. In the former case, two-thirds of the surface area registered was purchased by a segment of the peasantry. In some cases, they attended public auctions, where they bought suertes or plots of land ready for cultivation. In others, they legalised arbitrary occupations, roturos, through the payment of a sum that the valuation surveyors considered fair.Footnote 57 As regards the grazing lands, the purchases were concentrated among hacendados-landowners (58 per cent), individuals who in many cases belonged to the minor nobility (hidalgos), and who added a distinctive title to their name (don) as a sign of respectability. These were followed by large livestock farmers that owned migrating flocks of sheep or fighting bulls (19 per cent), and tradesmen (17 per cent).Footnote 58 Cash payments were made in similar proportions by hacendados and livestock farmers, being higher among tradesmen (59 per cent). A greater proportion of the latter ones were also more willing to accept the subrogation of long-term debt, while the first two tended to use promissory notes more often on short-term debt, as they had greater exposure to tax pressure during the war. In sum, large swathes of land changed hands over the course of these years, leading to greater inequality in income within the heart of these communities, the strengthening of the elites from the minor nobility, trade and livestock breeding (together accounting for 82.5 per cent of the amount of sales), and the loss of rents for the local coffers.

Table 7. Navarre, 1826–60

Notes: Classification of the buyers of municipal property according to social categories. Subr. = subrogation of mortgage; n.d. = no data. The figures corresponding to pastureland (corralizas) should be used with caution, as the balance of sales and repurchases has not been calculated. Thus, in some cases we will encounter double or triple entries, although this is not a problem for the analyses conducted here.

Sources: ARGN, PN (note 16).

A process such as this one, which increased the wealth of those segments better placed in the community and led to the powerful entry of outside investors, inevitably increased tensions in the countryside. Given that the traditional status quo had been swept away by two devastating wars, with profound changes in the political system, more marked social differences, and the loss of communal resources, how could a minimally stable order be re-introduced?

An initial answer might lie in the double direction and the protagonists of the privatisation process. While large swathes of pastureland were privatised through public auctions that benefited wealthy groups, more croplands ended up in the hands of intermediate segments in the community, in many cases, without involving an auction, but instead through the payment of their valuation figure. This meant that the disruption caused by the alienation of large tracts of land to major investors, in many cases non-residents, was offset by the involvement of part of local society in the transfer of property rights.

Secondly, the very terms and conditions under which privatisation took place tended to safeguard certain property rights in favour of local councils and households. Full and complete privatisation was the exception rather than the rule. When the lands for cultivation were alienated, specification was made of the reservation of the right to graze once the crops had been harvested, thereby rendering null and void the law passed by the Spanish parliament (Cortes de Cádiz) in 1813, which gave owners the freedom to enclose their plots. When selling the property rights over the ‘grasses and waters’ of the extensive corralizas, a series of easements were also reserved for the local people, thereby restricting the new owner's full rights over the use of this property. In many cases, the deeds of sale required the purchaser to respect the cultivated enclaves within the corraliza's perimeter. In some cases, matters went even further, upholding the local people's right to extend their cultivation by sowing new crops and planting vines. On other occasions, the deeds of sale recognised the right to collect certain resources of plant origin (firewood, cane, esparto), animal origin (game, manure), and mineral origin (stone, adobe, lime, gypsum) within the plot alienated. In other cases, the buyer was even required to allow the local people to graze their livestock on the land, sometimes in the form of communal flocks, and at others on an individual basis, albeit restricted to the labouring cattle belonging to those that had crop areas within the corraliza or in its immediate vicinity. In short, the transfer of property rights was not complete, and a combination of individual ownership and collective uses emerges in these cases (Table 1), or maybe it should be considered a combination of collective ownership and individual uses. The establishment of a hierarchy of rights is not an easy task and depends on the stakeholders’ correlation of forces.Footnote 59

These developments fit the concept of ‘institutional bricolage’ well, broadly understood as a ‘process by which people consciously and unconsciously draw on existing social and cultural arrangements to shape institutions in response to changing situations’.Footnote 60 Bricolage practices and the preservation to different degrees of these profit à prendre arrangements allowed a certain amount of consensus at the time of alienation by permitting traditional users to continue with their easements after the land had been sold.Footnote 61 Although in the short term this change in ownership may have been socially acceptable, in the long term it became a source of conflict. When the stimulus of expanding markets favoured the conversion of pasturelands into fields for cultivation, as occurred with the French demand for table wine in the 1880s, there was an inevitable clash between the heirs of those who had bought the corralizas (understood as property rights over ‘grasses and waters’) and those who thought they were entitled to occupy the land and cultivate it because they were local people (vecinos). During the first third of the twentieth century, the conflict deteriorated and adopted new political expressions (socialism, anarchy). When in 1931, the first government of the Second Spanish Republic offered villages the possibility of reclaiming ownership of those assets that they considered had been stripped away from them through unlawful practices during the nineteenth century, local councils responded en masse, and the applications for their recovery swamped the offices of the Institute for Agrarian Reform. The process that had begun in 1808 remained unfinished business.Footnote 62

4. Conclusion

Debt crisis produces favourable scenarios for introducing far-reaching institutional reforms, either because there is no alternative or because they become a suitable excuse for justifying radical changes to existing structures. One should not, however, lose sight of the fact there is not just a single solution, and the one adopted will depend on the correlations of existing forces. During the first half of the nineteenth century in Navarre, a profound crisis affecting local council finances combined with a new ideological climate that was well disposed to the privatisation of land, and with the appetites of wealthy social groups, gave rise to a profound transformation of land ownership structures and greater wealth inequality. Unless the privatisation process witnessed in this province should prove to be an exception within the Spanish context, for which there are still not enough studies, the 1855 General Disentailment Law promulgated by Pascual Madoz, a progressive minister of Navarrese origin, can be better understood as an attempt by the government to direct and control a process that had been taking place spontaneously since 1808, and to use it to resolve the problems of the public treasury.

Privatisation processes and the dismantling of the communal regime led to the consolidation of a powerful landowning elite of diverse origins (major and minor nobility, tradesmen, livestock farmers, moneylenders) but also enriched certain intermediate segments among the peasantry. In 1929, a lawyer named José-Joaquín Montoro-Sagasti summarised these two different sides of the change when, in a report drawn up for the local council in Olite, he distinguished between two ‘tendencies’ in the privatisation process: the minifundista (small estate) and the latifundista (large estate). Does this distinction reflect two different projects within rural society? Or should we consider them complementary rather than antagonistic? Ultimately, the former could make it easier to accept the latter. Yet this was insufficient. A transformation of such magnitude would have been hard to achieve without the traumatic experience of the two devastating wars (1808–1814 and 1833–1839) and without the spiral of tax levies that affected local councils and the community as a whole. Within that context, the privatisation of council and communal property may have seemed the right way to cover the council's extraordinary expenses or to convert the short-term debt arranged with private individuals, thereby avoiding the need to resort to further direct taxation. Even so, the necessary consensus for the privatisation process involved using an intermediate formula between borrowing and sale, namely, sale with the right of redemption (venta con carta de gracia), which enabled local councils to recover their assets through a cash reimbursement of the amount collected from the sale. The downside for the council was that the amount received was up to a third less than what would have been obtained through an irreversible sale. The use of this formula did not entitle the buyers to make full and unrestricted use of the land, as it could be taken back if the amount was repaid, but in the worst of cases, it would have meant transforming short-term promissory notes of uncertain liquidity into cash. Making privatisation socially acceptable in the short term also involved ensuring that the deeds of sale included several easements in favour of households and the local council, such as the exploitation of pastures for communal flocks or labouring cattle, gathering firewood and even crop farming within the corralizas sold. Institutional bricolage allowed the satisfaction of private appropriation to be compatible with a partial maintenance of collective uses.

The privatisation process in this case was, therefore, neither complete nor irreversible. This may have facilitated its social acceptance in the affected villages over the short term, but in the long term, it led to a latent conflict among those vying for the pre-eminence of their property rights over the land. When it came to a head, as in the case of Olite in the 1880s, it prompted a recovery of property rights in favour of the municipality and, in the end, of the landless labourers that pressed for an allotment. The transformation of collective use and ownership into individual ownership and use was not a default outcome.

Acknowledgements

This article has benefited from the research projects HAR2012-30732 and HAR2015-64076-P, financed by Spain's Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and the ERDF. Many scholars have helped to improve the text, with constructive suggestions being made by Josemari Aizpurua, Giuliana Biagioli, Salvador Calatayud, Iñaki Iriarte-Goñi, Ramón Garrabou, Juan Pan-Montojo, Ricardo Robledo, Alberto Sabio, Joseba de la Torre, Nadine Vivier and the manuscript's anonymous reviewers and the editors, particularly Julie Marfany. I am also indebted to sundry curators, particularly those at the municipal archive in Olite and at the Royal General Archive of Navarre (ARGN). My work with notary records was greatly assisted by Javier Ayesa. Any errors are the author's sole responsibility.