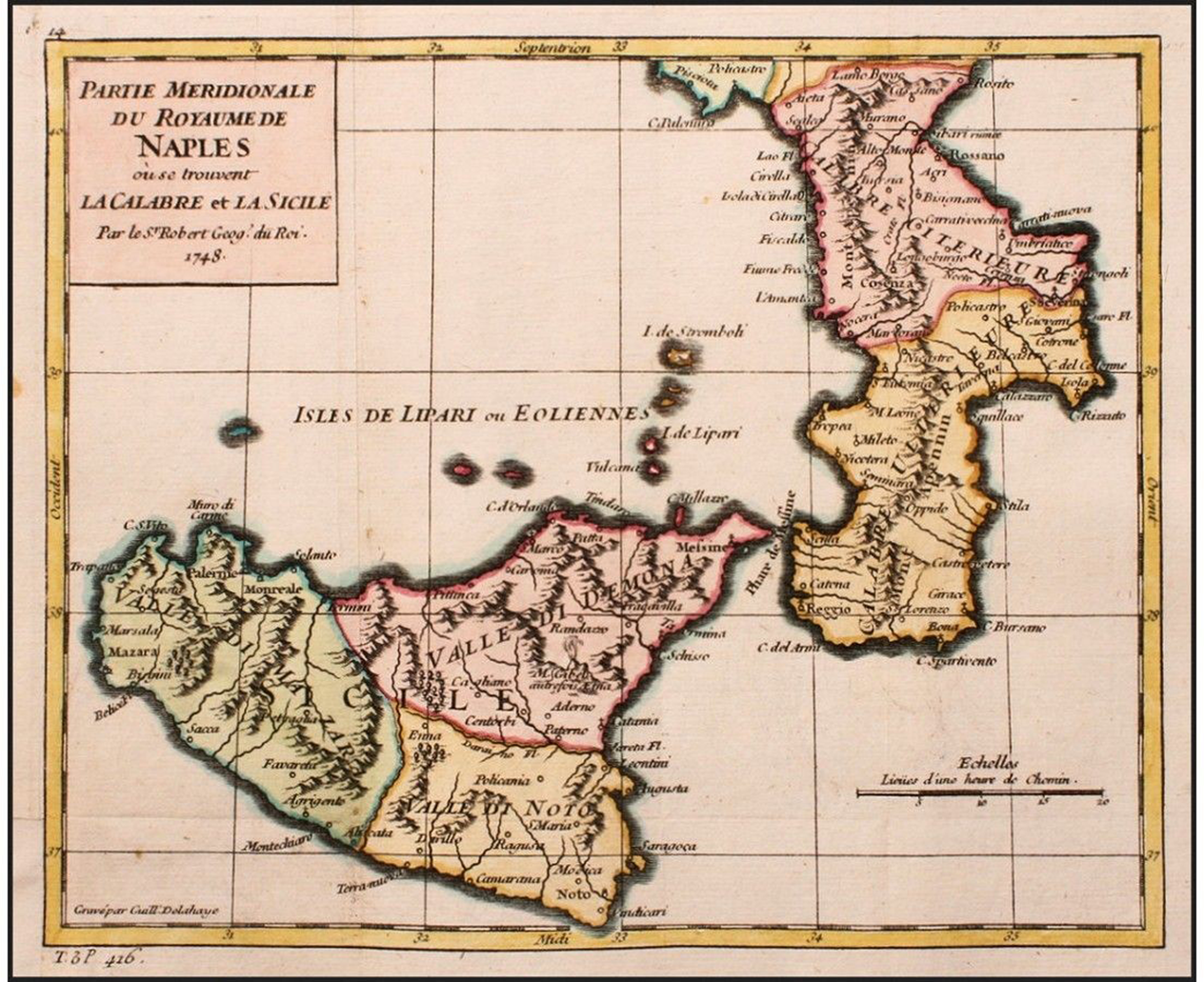

The small island of Stromboli is one of the seven islands making up the Aeolian Archipelago, which lies in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the North coast of Sicily. At the time of the Napoleonic Wars, and before Italian unification, Stromboli was part of the Kingdom of Sicily. During the Wars with Napoleon, Sicily, along with Sardinia and the Papal State, fought on the British side along with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russia, Prussia, Sweden and certain German Duchies. France's allies, including many of the states it managed to conquer, were Spain and the kingdoms of the Netherlands, Italy, Naples, Bavaria, Saxony, Württemburg, Westphalia, Denmark and Norway. The Wars lasted from 1803 to 1815, and in 1806 France set up what became known as the Continental Blockade; British ships were prohibited from docking in French ports, or those of their allies, and vice versa. The Blockade remained in place until 1814, creating a crisis in the legitimate trading of goods between the warring states,Footnote 1 and forms of illicit trade flourished across Europe as people struggled to circumvent the prohibitions.Footnote 2

This article examines the impact of the trade crisis on a local, family-based economy of the Mediterranean, which relied heavily on fishing and agriculture, by focusing on the illicit trades which flourished on Stromboli. As an island lying in the seas between the Kingdom of Sicily (hereafter ‘Sicily’), which was allied to Britain, and the Kingdom of Naples (hereafter ‘Naples’), which was under French rule, Stromboli became a perfect base for smuggling.

Moreover, during the war Sicilian corsairs, who had state backing to attack ships flying an enemy flag, used the island as a centre where they could sell the goods they had seized from the ships they had captured as ‘prizes’ without paying 10 per cent of the value to the State. Stromboli became a highly strategic location between the warring kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, and this article argues that the crisis in international trade caused by the Continental Blockade opened up additional resources and opportunities for the inhabitants of Stromboli, by giving them the chance to integrate the island into the network of maritime traffic that had, until that point, been dominated by the two biggest islands in the archipelago, Lipari and Salina.

This article will highlight, first of all, the importance of illegal forms of trade across the entire area of the lower Tyrrhenian Sea during the Continental Blockade, and will then consider the reform of the local institutions, such as Customs and Health Offices, which controlled this trade along with the Prize Court. Finally, the article will consider the differences between the roles that men and women played in two separate types of illegal trade which flourished on Stromboli during the international trade crisis of the Napoleonic period: the traffic in corsairs' prize goods and salt smuggling. There are no sources giving details of Stromboli's economy before 1800, so we must rely on early nineteenth-century accounts of the roles of the two sexes in the island's household economies. However, the main sources used for this study are the documents generated by two judicial inquiries, carried out by the Sicilian government in an attempt to curb salt smuggling and the illegal sale of prize goods. These documents will be used to demonstrate that although the island's men and women played integrated, and often overlapping, roles in agriculture and fishing which formed the basis of their household economies, their experience when it came to illegal trading activities was rather different. Women on Stromboli, it would appear, were fully involved in the minor, low-level transactions associated with the fraudulent sale of prize goods but were excluded from large-scale smuggling operations involving large quantities or high-value goods, which often required the connivance of officials from various institutions. We must therefore also address questions regarding the position of women in the family economies of Mediterranean Europe during the early-modern and modern periods.

In the decades following World War II, anthropologists studying the Mediterranean suggested that women were largely excluded from work outside the home because of an ‘honour-shame complex’. This thinking has strongly influenced our understanding of the social and community history of southern Italy.Footnote 3 There has been considerable debate over the ‘honour-shame’ paradigm, and it has been criticised by a number of women historians and anthropologists, particularly those studying work in agriculture and in urban areas and those interested in the history of the family.Footnote 4 As yet, however, there has been no analysis of women's role in informal trade networks as the information to be found is often fragmentary, dispersed across various archives, and is mainly drawn from legal or court documents. Although Stromboli's position might be thought to be a peripheral one, it actually lay on a very important intersection of established trade routes. Our analysis of the roles played by men and by women in illicit trading in such a context during a commercial, diplomatic and military crisis not only increases understanding of the asymmetry between the genders in this part of the Mediterranean but also shows that women's work outside the home was important to the economies of the island.

1. Illicit trading activities in the Tyrrhenian Sea

Before examining the specific case of Stromboli, it will be helpful to outline the geopolitical context which encouraged illicit trading activities around the Mediterranean and its islands, and particularly in the Tyrrhenian Sea, during the Napoleonic Wars, and to discuss the historiographical analyses of this phenomenon which have been undertaken.

Ports and islands are particularly suited to the illicit trading of goods, and certainly some, like the ones on the Atlantic coast of France, specialised in such activities during the Ancien Régime.Footnote 5 Such localities are thus excellent places to study how local communities become integrated into large trading networks, how the individuals involved were able to avoid the institutions and regulations which were supposed to govern trade, and how involvement in unlawful activities brought together individuals from across a range of social, cultural and institutional strata; so that labourers worked alongside the ruling classes, officials alongside ordinary citizens and men alongside women.

Events such as wars, revolutions and institutional upheavals tend to alter the productive and commercial fabric of a society, and to accelerate and intensify the development of illicit trading.Footnote 6 According to Montenach, illicit trading activities and fraudulent practices arise particularly in periods of crises because they offer versatile solutions to the problems besetting most of the populations involved.Footnote 7 Fraud introduced flexibility into the economy of the Ancien Régime, for example, when traders were forced to operate in a state of uncertainty.Footnote 8 This certainly happened on Stromboli.

Marzagalli has underlined how in Europe, during the years of the Continental Blockade, there was a ‘tipping point’ after which both fraud and smuggling intensified.Footnote 9 Both those formally involved in legal trade and those working within the informal economy were involved. Marzagalli showed that merchants and businessmen across Europe who were involved in maritime trade reacted to the trade crisis created by the Blockade by using neutral ships, rather than those carrying national flags, by adopting alternative trade routes and by smuggling. As Salvemini has noted, trade – a source of ‘Public Happiness’ – was pursued by every means possible during times of war, even when bureaucrats and the war itself put serious obstacles in the way.Footnote 10

During the Napoleonic War and the years of the Continental Blockade, these geopolitical and economic dynamics were played out around the southern Tyrrhenian Sea.Footnote 11 Fraud in the sale of prize goods and smuggling intensified in the waters between Sicily and Calabria, the southernmost region of the Kingdom of Naples. Individuals from all walks of life were involved, from high ranking officials and merchants of all sorts to men and women living in small villages along the coast. Illicit trading activities were closely intertwined with legal forms of trade and all those involved had to negotiate the rapidly changing rules and institutions during times of war. Research by Heurgon into smuggling around the Strait of Messina, a narrow stretch of water between Sicily and Calabria that shared the same geopolitical conditions with the nearby Aeolian Islands, highlights the latter issue with great clarity.Footnote 12 Heurgon describes how, when the French took Naples on 14 February 1807 and the British landed in Sicily two days later, the breach between the two regions was total; all legal trade ceased. With the consequential establishment of the Continental Blockade, the Strait of Messina lost its function as an important sea route and took on the character of a trench between two opposing armies. The war did not suppress completely the trading relationships between the neighbouring regions; instead, it altered them, transforming them into illegal ones. In short, the lower reaches of the Tyrrhenian became a ‘prime seat for smuggling’.Footnote 13

Smuggling had long been one of the many forms of mercantile exchange between Sicilians and Neapolitans.Footnote 14 However, Heurgon noted a significant intensification during the Napoleonic years in both small-scale, or ‘filtration’,Footnote 15 smuggling and more substantial illegal trading between Calabria and Sicily, organised by top- and middle-ranking officials from both local and national institutions.Footnote 16 The British established a system of licences that gave special authorizations to merchants and ship owners of the belligerent countries to trade with the enemy, thus overcoming the obstacles posed by the Blockade.Footnote 17 These legal trade routes and the illicit ones became closely interwoven.

Sailing from the south, the narrow Strait of Messina, ‘an undivided space, a treacherous “river” crowded with boats’, opens onto the wide triangle of the southern Tyrrhenian Sea, in which Stromboli and the other Aeolian Islands lie.Footnote 18 At the tips of the base of the triangle lie the important Sicilian ports of Palermo and Messina. The latter was a free port (a common institution in Mediterranean and Atlantic countries since the sixteenth century, that is, a port that granted merchants special exemptions from custom duties with the purpose of facilitating trade), making it even more attractive to smugglers and those hoping to trade goods illegally because its superintendents protected smugglers' boats coming from Calabria in order to attract their trade.Footnote 19 The apex of the triangle was formed by the Sorrento peninsula, which lies on the coast of the Italian mainland between the Gulfs of Salerno and Naples. All along the neighbouring coastline, there were numerous bays, ideal for unloading goods unseen, as well as harbours of various sizes.Footnote 20

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Aeolian archipelago, along with the rest of Sicily, was affected by the economic transformations wrought by the British. The latter had held the protectorate of the Kingdom of Sicily since King Ferdinand of Bourbon, who previously ruled both Naples and Sicily, had fled to his second kingdom when the French occupied Naples in 1807.Footnote 21 Apart from Malta, Sicily was the only place in the Mediterranean not to fall under French rule. Sicily, thus, had an important role to play in the international trade crisis brought about by the Blockade. As François Crouzet has pointed out, ‘the impact of the (Napoleonic) wars upon the long-term development of industry [in Britain] was felt mostly through the dislocations in international trade which were brought about by the twenty-year long conflict between Britain and France and by the progressive involvement of all other European countries in which economic warfare played a prominent part’.Footnote 22 Sicily was an important market where British goods could be bought and sold during the Blockade,Footnote 23 as its large population (about 1,600,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the nineteenth centuryFootnote 24) could buy and consume far more imported goods than the much smaller population of Malta, and it could also provide commodities such as wheat, wine, oil and soda ash – the last two in great demand for industrial use – which could be loaded onto vessels returning to Britain. Numerous British merchants settled in Sicily during the Napoleonic Wars, and once hostilities ended, many of them remained permanently.Footnote 25 Whether Britain's interest in Sicily and its lesser islands during the War years had tangible economic repercussions for the Aeolian Islands is hard to tell,Footnote 26 but the economic and demographic development of the archipelago certainly grew steadily across the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century.Footnote 27

2. The economy of Stromboli: male and female roles in agriculture and fishing

Let us now turn to focus on Stromboli, to place the inhabitants in their social and economic context and to consider the effect of the maritime trade crisis on their household economies. The Aeolian archipelago is, as we have seen, made up of seven islands. The most important islands at the beginning of the nineteenth century were Lipari, which held the See of a rich bishopric, and Salina, which had a flourishing agricultural economy. The latter would go on to develop substantial merchant and fishing fleets over the course of the nineteenth century. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Lipari and Salina were relatively well populated, each with several villages. They both supported agricultural activities, including the production of wine and raisins. They also had mining industries and, of course, maritime trades. Salina was home also to an affluent middle class of ‘sea merchants’ and, as the most important island, Lipari's population was more socially stratified.Footnote 28 In the eighteenth century, the four peripheral Aeolian Islands; Alicudi, Filicudi, Panarea and Stromboli, had very few inhabitants. Stromboli, formed by a volcano which remains active today, is the most north-easterly of the islands, lying closest to the coast of the Mezzogiorno, or the southern half of mainland Italy. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Stromboli grew in importance and its population expanded.

The growth of the economy of the Aeolian Islands during the nineteenth century was largely due to the development of mines producing pumice stone, alum and sulphur, as well as to the extension of the sailing routes passing through the Archipelago which connected the Sicilian coast to the harbours of Salerno, Naples and Calabria. This growth continued until the last quarter of the nineteenth century when the Archipelago's economy was adversely affected by a number of developments, including the completion of a steamboat service connecting Palermo and Naples which bypassed the Islands; the spread of vine blight, phylloxera, which severely damaged grape harvests at the end of the 1880s; and then, in the 1890s, an acute and permanent crisis ensued with the decline of the merchant marine.Footnote 29

Unfortunately, there are no demographic or notarial sources relating to Stromboli or the rest of the Aeolian Archipelago before the second decade of the nineteenth century.Footnote 30 Therefore, to obtain any information on the islands in earlier times, we have to rely on the reports of visiting travellers, scientists and naturalists. According to the well-read Pietro Campis, writing in 1694, Stromboli was uninhabited and supervised only by two custodians who were entrusted to notify the authorities in Lipari if Muslim corsairs from the Barbary States that used to raid Mediterranean coasts from the sixteenth century were seen to pass by the island. In 1737, the abbot Vito Amico noted that the inhabitants of nearby islands were planting cotton on Stromboli. When, in 1776, the traveller and painter Jean Houel came ashore he found a few, welcoming inhabitants gathered on the beach and observed that wheat and Malvasia grapes were being cultivated. In 1781, the geologist Déodat de Dolomieu was also greeted by generous, helpful inhabitants and observed the cultivation of vines, as did the scientist Lazzaro Spallanzani in 1788. In 1769, the diplomat William Hamilton estimated that the population of Stromboli consisted of around one hundred families, a figure also suggested by the poet Ippolito Pindemonte in 1779.Footnote 31 During the eighteenth century, successive Bishops of Lipari let out some of the land on Stromboli under ‘permanent lease’, or emphyteusis, in order to encourage settlement, a practice seen on other small Italian islands in this period. It was not until the following century, by which time the Church no longer offered concessions of land to the inhabitants, that Stromboli's population began to increase rapidly; by the 1860s, it had around 1800 residents.Footnote 32 Nineteenth-century travellers wrote of an island where wheat, capers, figs and vines were cultivated, even high on the slopes of the volcano.Footnote 33

There is also virtually no information on the economy of households on Stromboli before the nineteenth century, and even after that most of what we know again comes from the writing of travellers. The inhabitants integrated their work on the land with both fishing and coastal trading, local men working as sailors on board the local inshore fleet or skippering vessels travelling further afield. The pursuit of such multiple activities appears to have been made possible by the integration of male and female work. Women, as well as men, toiled in the fields to support their families, and they also helped to process agricultural and maritime products, by drying grapes to produce raisins, for example, or salting fish or capers. The women also participated in maritime activities such as fishing or rowing.Footnote 34 In 1826, Alexis de Tocqueville, stormbound on Stromboli on his way to Sicily, watched a boat coming in to harbour rowed by three generations of men and women from the same family.Footnote 35 Archduke Ludwig Salvador Von Österreich, the son of Leopold II of Tuscany and a traveller, naturalist and amateur anthropologist, who visited and studied the Aeolian archipelago from 1869 onwards, wrote: ‘It is often a whole family, father, mother, sons and daughters, that crew a fishing boat, and that boat, as they say here, represents the entire household’,Footnote 36 he also noted that it was very common for women to sail boats without a man's help, sailing them ‘stern forward, so that it is not difficult to identify a boat sailed by a woman (or women), even if from a distance’.Footnote 37 Von Österreich further reported that on Stromboli ‘after five o'clock in the afternoon … a merry crowd of girls and women, swimming and laughing, would bring their boats ashore for the night, or come back from fishing, or from tilling the soil on the distant slopes of the volcano’.Footnote 38 It is not clear, however, whether this had been the case from the first substantial settlement on the island in the previous century. We have similar reports from the 1800s of women working on other islands in the archipelago: on Panarea and Lipari, ‘little girls can be seen carrying heavy loads of pumice stones on their shoulders. [ … ] They work merrily and fast, all on their own’.Footnote 39

It is not only the men who carry out the work on the Aeolian Islands, but women too. They till the soil most meticulously and perform the manliest tasks. They hoe the ground, and look after their vines with great expertise, and harvest capers as well as muscadine and other sorts of grapes with the utmost care

wrote the botanist Michele Lojacono Pojero in 1878.Footnote 40

Women on Stromboli were also involved in property transactions. Notaries’ records from the island show that women owned both movable goods and immovable property, such as plots of land and houses.Footnote 41 The local system of inheritance was characterised by the partition of wealth between heirs, by bilateral descent down both the paternal and maternal line, and often by sons and daughters receiving an equal share of inheritance or any endowments. It also appears that relatives could, and did, swap or sell their portions of an inheritance for mutual advantage. A wife who survived her husband held the usufruct of either the whole or a significant part of his property, which she would manage together with her adult children, or on her own if the children were still minors.Footnote 42

3. The sale of prize goods on Stromboli

Stromboli lay semi-deserted for centuries as a consequence of several volcanic eruptions.Footnote 43 In the early modern period, like many other Mediterranean islands, it was subjected to raids by corsairs from the Barbary States under Ottoman rule.Footnote 44 These were a scourge of the Aeolian Archipelago during the wars between Christians and Muslims especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Lipari, for instance, was sacked by Hayreddin Barbarossa in 1544 and then had to be repopulated after the victors took the islanders into slavery en masse.Footnote 45 The Archipelago frequently features in the history of Mediterranean slavery, both as a place of origin of captives arriving on the Barbary Coast as well as a place where slavers could meet or trade their cargoes. Certainly, slaves are known to have been bought and sold on Stromboli, which had always attracted illicit or semi-licit traders as it was wild and inhospitable and, of all the outposts of Sicily, lay nearest to the southern coasts of the Italian peninsula.Footnote 46

During the very late eighteenth century and the years of conflict between France and Britain in the early years of the nineteenth century, the population of Stromboli were able to exploit its strategic position. The Aeolian Islands were recognised as ‘a key zone, and their role throughout those years was intensified by the disjointedness of the current of traffic and political-military events’,Footnote 47 and the Sicilian government saw Stromboli as a particular seat of ‘disorder and disorientation’,Footnote 48 thanks to the continual smuggling and fraudulent trading going on there.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Stromboli was used as a base for the black market in goods taken from ships captured by corsairs sailing under the authority of Ferdinand, King of Sicily. According to maritime law, Ferdinand's corsairs had to have the ships and any contents they seized declared as legitimate prizes by the Prize Court of the Kingdom of Sicily, which was situated in Palermo. Once this was done, the prize could be sold, but 10 per cent of the value would be claimed by the State. Corsairs were not only captains of their ships, they were also often businessmen who had invested in their enterprise and many of them tried to avoid paying the 10 per cent levy by selling the goods they had seized before arriving in Palermo. Stromboli, lying midway along the route between Sicily and Naples, was a perfect trading point.

The prohibitions on trade put in place by the warring nations, along with the obstacles to trade created by the war, and the island's strategic position, created many opportunities for the inhabitants of Stromboli, particularly as in the Archipelago there was both a public and private demand for the goods brought by corsairs. The corsairs became embedded in the social and economic fabric of Stromboli as the prize goods they sold became increasingly important to the island's economy, along with goods being smuggled in both directions from Naples, through Calabria and across the Strait of Messina into Sicily. Stromboli became a sorting house on these trade routes, through which the flow of goods was directed towards other islands within the archipelago, particularly Lipari.

In a previous study of maritime fraud, I examined the fencing of corsairs’ prize goods on Stromboli between 1807 and 1811, reported in great detail by an investigation undertaken by the Prize Court of Sicily.Footnote 49 This Court was active on the orders of the Government of the Kingdom of Sicily between 1808 and 1813 in order to legitimate the capture of prize ships by corsairs armed by all the warring parties in the Mediterranean during the Napoleonic Wars, and to regulate the resale of the goods they contained. Here, I return to the same source to consider the involvement of local families in the trade between corsairs and the islanders; to examine the presence, and roles, of women in that trade; and to examine the similarities and differences between this form of activity and the smuggling of goods such as salt, wheat, cattle, sheep or goats, ropes and tar, pasta, rice and salted meat.

Officials from the Sicilian Health and Police departments, who controlled the circulation of men and goods into, out of and across the Kingdom, are known to have taken advantage of their powers; sometimes they would expose the illicit activities, sometimes turn a blind eye; some clamped down on clandestine landings, while others would facilitate them. The powers, and the officers, of the Police, Health and Customs forces which watched over Sicily were all interconnected. Health surveillance on the island was improved in the second half of the eighteenth century, after the plague of Messina hit in 1743, but the Customs and Police Services were not reformed until the very beginning of the nineteenth century.Footnote 50 Between 1806 and 1808, a Maritime Police force was established to monitor everything entering and leaving Sicily: people, goods or ideas.Footnote 51 The Customs reform, passed in 1802, was meant to safeguard the interests of the Kingdom's Revenue and to collect indirect taxes according to clear criteria. In doing so, it reshaped maritime Customs on Sicily and abolished certain special exemptions from duties which Lipari had enjoyed.Footnote 52 The years of the war and the Blockade were also the years of the difficult launch phase of these recently reformed institutions, still stuck in the logic of bargaining between local powers and unable to control the lawfulness of the trades.

On Stromboli, this rather confused situation was exacerbated by the intertwined networks of personal alliances which connected the various institutions, increasing the opportunities for illegal trade even further. The entire population of the island built up extensive commercial, personal and working relationships with the Police, Health and Customs officials on the one hand and with the corsairs on the other. They provided the corsairs and their crews with warehouses and storehouses where illicit exchanges of goods could take place or equipment and goods could be stashed. They also offered boat-repairing services, hospitality, health or personal care, and credit and supplies in both money and in kind.Footnote 53 Many islanders participated in the purchase or resale of goods from the prize ships captured by those corsairs who had given their allegiance to Ferdinand but who preferred to unload the ships’ cargo on Stromboli and sell it clandestinely, rather than take it before the Prize Court and forfeit 10 per cent tax of their value.Footnote 54 The situation on Stromboli was well known, even by the Royal Secretary, the Secretary of State, War and Navy, and the chiefs of Police in Palermo. As early as 1807, complaints and reports had been filed to the Government of ‘serious inconveniences which have been and continue to be committed on the island of Stromboli by Sicilian corsairs, hiding there [ … ] and perniciously passing off goods from captured ships’.Footnote 55 In 1810–1811, the Prize Court conducted the Camerale processo, an inquiry into the activities on Stromboli, which was triggered by a conflict on the island over a bale of raw silk which had been used as a bribe. The inquiry uncovered a network of collusion and complicity encouraging the small-time fraudulent sale of prize goods.Footnote 56

The corsair system could also work like a big business as shown in the records of the Amministrazione dei corsari di conto regio (Administration of corsairs working on behalf of the Monarch), through which the Sicilian Monarchy managed its own fleet of corsairs, arming vessels to attack ships flying enemy flags. The Amministrazione was controlled, from Palermo, by Queen Maria Carolina and her emissary, the Chief of Police, Giuseppe Castrone, both of whom recognised Stromboli's strategic position.Footnote 57 Castrone occasionally sold prize goods on Stromboli himself, as did Gaetano Gambardella, probably one of the most powerful, unscrupulous and well-connected corsairs operating clandestinely in the Aeolian Islands and on the coasts of Sicily and Italy.Footnote 58 For such ‘big players’, the archipelago was just one of many business locations; Castrone and Gambardella also made use of other landing places in and around the Tyrrhenian, such as Ponza, and traded on Vis and the islands off the Dalmatian shore in the Adriatic.

On Stromboli, the ‘big players’ were surrounded by a host of men and women who bought and sold the goods unloaded by the corsairs on a much smaller scale, often on their own account. These activities are described in the testimonies collected during the Camerale processo, which allow us to outline the salient facts of the illicit trades and provide some illustrative examples. The trading activities appear to have been ‘regulated’ in one sense by the seemingly random arrival of a ship and its cargo, as this of course depended on whether the corsairs successfully met with, pursued and captured enemy ships in the southern Tyrrhenian sea. When a prize ship and its cargo did arrive the islanders took advantage of it in every way possible. Some goods served to supply the islands of the Archipelago; oil seized by corsairs and sold on Stromboli was often bought on behalf of the Giurati, or City Council, of Lipari, for instance, and was also used to supply Albanian troops serving King Ferdinand on Sicily.Footnote 59 A ship's cargo could be bought and sold wholesale, or sold in dribs and drabs to people on the beach where a corsair came ashore. Individual items could then be sold on to local families needing everyday supplies or artisans requiring materials. The Camerale processo records empty vats, soles and thread for shoemakers, iron, various types of rope, cattle, liquorice, pasta, oil, raw silk, sturdy fabric to make clothes and bedlinen, hemp and cotton yarn all findings their way into homes and workshops on Stromboli and its neighbours.Footnote 60

Given that such illicit trade was often inextricably interwoven with more legal forms of exchange, and quickly became part of the economic strategies adopted by households, it is not surprising that the records often show family groups active in these activities. One set of brothers, Domenico and Vincenzo Cincotta, sons of the late Girolamo Cincotta, bought nautical equipment, cables and raisins from the corsairs Senese, Gallo and Gambardella.Footnote 61 Another two brothers, Gaetano and Giuseppe Cincotta, along with their 70-year-old father Simone, who loaned money to the corsairs, bought fishing nets and equipment, vats, sheep, oil and a heifer from the corsairs Gambardella, Mulinaro and Di Mauro.Footnote 62 A third set of brothers, Gaetano, Giuseppe and Vincenzo Panjo, purchased large amounts of raisins, oil, cattle, a shotgun, a boat and other goods. Described as ‘boat owners’, the trio also lent money to the corsairs, provided supplies for their ships, were implicated in various smuggling activities, and were allegedly ‘deeply involved’ in a case of corruption.Footnote 63

The records also show married couples or entire families involved in the illegal trafficking of goods. Maria Tesoriero, either acting for others or on her own behalf, along with her husband, Giuseppe Panettieri, were an example of the former, and the D'Albora family: Mastro Bartolo D'Albora and his wife Eleonora Lo Curcio plus their son Pietro and his wife Giuseppa, along with Pietro's sister Maria and his mother-in-law Maria Moleti, were an example of the latter.Footnote 64 The D'Albora men had close ties with the corsairs, being fully complicit in their activities and providing them with storehouses. The women traded and worked silk brought in from Calabria by smugglers and corsairs.Footnote 65

The records generated by the Camerale processo also allow us to identify numerous women who, like Eleonora and the two Marias, bought, sold, estimated, worked and had others work the smuggled silk which arrived on Stromboli. While some played a ‘team game’, others acted on their own, including Sister Maria Galletti and Sister Maria Tesoriero, two bizzoche, well-to-do women who had taken religious vows of chastity, but did not join a religious order or enter a convent, remaining in their own homes.Footnote 66 Sister Maria Galletti was recorded as buying an empty vat from the corsair Gaetano Gambardella, while Sister Maria Tesoriero bought three vats and some oil from the corsairs, which she then exchanged on the island for some wine. Women on Stromboli can, thus, be seen to have participated in this type of relatively small scale, illicit trade, just as they did in all other forms of economic transaction on the island.

4. Salt smuggling between Stromboli and Calabria

Women do not feature in the Prospetto del processo de’ controbandi, immissioni ed estrazioni del sale in Stromboli, an inquiry into the smuggling of salt and other goods conducted by the Sicilian government at the end of the Napoleonic War, between 1814 and 1817.Footnote 67 Smuggling was probably the most important – and most profitable – illegal economic activity on Stromboli at this time. Although many of the same individuals seen in the reports of the Camerale processo as being involved in the fraudulent sale of prize goods also appear to have taken part in salt smuggling, the latter activity would appear to have worked in a different way to the former, with women being completely excluded. Organised gangs of smugglers on and around Stromboli transported quantities of salt from saltpans on Sicily, such as those at Trapani on the island's north-western coast, to the Kingdom of Naples. On their return, the smugglers brought other goods to the archipelago without, of course, paying Customs taxes. The operations between 1814 and 1816 were very well planned and coordinated by a group of collaborators from key institutions such as Customs, the Police and the Deputazione di Sanità (Quarantine Board). At their head was the Chief of Customs on Lipari, Lieutenant-Colonel Don Felice Tricoli. Gaetano Gambardella was also part of the group, leading its most daring exploits. It was the well-to-do inhabitants of Stromboli, the owners of boats and warehouses, who had an interest in this type of smuggling, as they had the resources to transport, load, unload and store the goods, enabling them to make excellent profits.Footnote 68 Less well-off inhabitants of the island served in more subordinate roles as sailors or porters, but no women were involved.

The island was suited to the hiding and handling of large quantities of salt and other smuggled goods which were in transit. The situation was somewhat different in the nearby Strait of Messina. There merchants organised large-scale smuggling of salt, tobacco and other goods into and out of the free port of Messina, but there was also a great deal of ‘filtration’ smuggling on both sides of the Strait.Footnote 69 Numerous small boats, crewed by local men and women, either ferried limited quantities of goods across the narrow Strait between poorly guarded sites on the coast or, more often, brought goods to shore from passing ships.Footnote 70 Messina, like any other free port, both attracted smugglers and facilitated smuggling. Merchants undertook illegal imports and exports as just another aspect of their ‘active trade’ with neighbouring Calabria, which had traditionally used the sickle-shaped port as its gateway to international markets.

In the Kingdom of Naples, salt was a monopoly product from which a significant portion of taxes was derived, guaranteeing the public debt (arrendamenti).Footnote 71 The law had always imposed heavy sanctions on smugglers, albeit with little effect. A particular concern for the authorities in Naples was the smuggling of salt from nearby Sicily, with its many saltpans, particularly those at Trapani and the nearby Marsala. When Sicilian Customs laws were reformed in 1803, a decree was issued indicating that shipments of salt from Sicily to Naples and further afield were to be strictly regulated; the routes and the destinations which could be used by those exporting salt were to be strictly controlled in order to curb smuggling.Footnote 72 When the French arrived in Naples during the Napoleonic Wars and King Ferdinand transferred his court to Sicily, the law evolved inconsistently, following the progression of warfare and the changes over control of the ports and islands.Footnote 73 Special measures covering the ships of the Royal Marine and ships owned by the Crown and under the control of Giuseppe Castrone were put in place. Castrone, as we have already seen, was active in the illicit sale of prize goods and well aware of Castrone's unscrupulousness, the authorities feared that the ships under his command would load greater amounts of salt than needed by the crew, thereby leaving the Chief of Police, and by association, the Royal Navy itself open to accusations of smuggling.Footnote 74 During the years of the War and the Blockade, however, smuggling, including salt smuggling, was supported by all sides; by Joseph Bonaparte and Murat in Naples, who needed to supply both the occupying French army and the local population, and by King Ferdinand on Sicily. When Ferdinand returned to Naples after hostilities ceased, the legislation was modified once again: Salt could only be shipped from anywhere to Naples under contract with the General Administration of Indirect Taxes of the Kingdom of Naples, and ship owners were obliged to obtain certificates, issued by the Neapolitan Customs authorities, giving them permission to load or unload their cargoes.Footnote 75

Not surprisingly, it was not until after the King's return to Naples in 1815 that the first report of salt smuggling on Stromboli appears in the records.Footnote 76 In the autumn of 1815, the King, his Minister of Internal Affairs, the Duke of Gualtieri, and the Secretary of State for Business and Commerce, the Marquis Ferreri were informed by Lieutenant Francesco Casselli, the Police Deputy on Stromboli, that ships loaded with salt and bound for Naples had arrived on the island without the required shipping licenses. The largest of the ships had sold its salt at sea, transferring it to smaller vessels, as the captain had not wanted to come too close into the Calabria shore in case he was seized by Ferdinand's Royal Navy. Throughout the following year, the Chief of Customs on Lipari, Don Felice Tricoli, who was suspected of being a major supporter of the smugglers, if not in overall charge of their operations, tried to clear his name. He accused the Police Deputy Francesco Casselli of stopping ships in order to extort a componenda, a bribe or payment for immunity from prosecution. The Marquis Fardella, Chief of Customs in Trapani, where most of the salt shipments originated, denied that ships leaving Trapani then headed to the Aeolian Islands with the intention of handing over some or all of their cargoes to the smugglers. When, however, on the 6th of September 1816, a Royal Navy ship captured a fishing boat off the coast of Stromboli which had taken on a cargo of smuggled salt in Lipari, smuggling could no longer be denied. The owner of the boat and his crew of three were arrested, although they later managed to escape. The Police Deputy Casselli informed the Ministers Gualtieri and Ferreri and the Chief of Customs in Messina, Prince Sant'Elia, decided to ‘carry out a formal investigation’ into the smuggling of salt and other goods.Footnote 77 At the same time, the Police Deputy on Stromboli reported that there were large quantities of salt lying in warehouses on Stromboli, some of which belonged to the priest, Father Tesoriero. The salt had been brought to the island by Father Famularo on a boat belonging to the former corsair, Gambardella. Gambardella was arrested in Calabria and brought to the Vicaria prison in Naples. Deputy Casselli drew up many reports in November 1816, reconstructing the dynamics of the smuggling operations. He highlighted the fact that it was Lipari's Chief of Customs, Tricoli, who had organised of the illegal trafficking with the help of his main collaborator, Cristoforo Ventrici, while the ‘meddlesome priest’ Famularo had presented false witnesses to the formal investigation.Footnote 78

The 27 cases of salt smuggling reported by the investigators in the Prospetto, where the loose documents regarding the inquiry were summarised, detail how the smugglers Tricoli and Ventrici and their accomplices, having brought the salt from Sicily to Calabria, sold it on to local smugglers who probably then conveyed it to Naples.Footnote 79 Their profits from the sale were then used to purchase merchandise which they smuggled back to the Aeolian Islands, evading all checks thanks to the Chief of Customs who was the main businessman behind the entire enterprise. They were thus able to supply the merchants of Lipari with cattle, sheep and goats, wheat, oil, pasta, rice, lard and ham, in addition to some of the smuggled salt. Tricoli and Gambardella also transported oil from the Aeolian Islands to Ponza, in the Gulf of Gaeta, an island that, like Stromboli, was at the centre of corsair activity during the war.

On Stromboli, the main figures involved in smuggling were the same as those playing a leading role in the resale of prize goods: Fathers Tesoriero and Famularo, the Pajno brothers and the Cincotta brothers, among others. Between them, this group managed the transport routes and the warehouses, and owned and piloted the boats that sailed for Calabria. They became rich through smuggling, and managed to avoid prison, and the seizure of their goods, by paying for costly guarantees of immunity. This was not the case with those who masterminded the smuggling operations. We do not know what happened to Gambardella, the corsair, after he was imprisoned in Naples. Maybe an adventurer of his calibre, ‘a true corsair in all things’, was able to escape from prison, or avoid punishment; he does not appear again in the records.Footnote 80 We do know that Lieutenant-Colonel Tricoli, Chief of Customs on Lipari, was brought to trial on Lipari and jailed in Palermo, as was his accomplice Ventrici. Tricoli also had his goods confiscated. The records show that following the political uprising of 1820, the two men, along with other inmates of the prison, were released, arousing ‘great palpitations’ in the judge that had condemned them, who was present in the city and feared revenge.Footnote 81 In 1822, Tricoli was back in police custody in the town of Patti on Sicily's north-east coast. He petitioned to be transferred to Milazzo, the port closest to the Aeolian Islands.Footnote 82 Three years later, the records show that he was sentenced to serve 20 years in the Castle, by a special Military Board in Palermo.Footnote 83 A decade later, in 1836, Tricoli made a will leaving a farm, some warehouses and the income from a rental property to the Women's Hospital in Lipari; he died soon afterwards.Footnote 84

5. Conclusions

During the international trade crisis created by the Continental Blockade of 1806–1814, the people of Stromboli were able to take advantage of the favourable position which geography and geopolitical circumstances had bestowed upon them. Sitting in the Tyrrhenian Sea between opposing French and British forces and their allies, the people of Stromboli participated in salt smuggling and the fraudulent sale of prize goods as these illicit trades became increasingly important across the Mediterranean, and the Tyrrhenian Sea in particular. They were able to offer their services as intermediaries, and provided provisions, services, credit, labour and warehouses to the smugglers and corsairs, thus adding to the income they earned through agriculture and fishing. The illicit activities in the South Tyrrhenian Sea attracted the attention of the Sicilian authorities, who duly investigated them, leaving behind documents which describe the commercial networks and material culture of the smaller islands of the Aeolian Archipelago at a time when information on the demography and economy of the islands is completely lacking. From these sources, it emerges that although women were involved in the fraudulent resale of prize goods, they do not appear to have been major players in the smuggling of higher value or greater quantities of goods.

When the Napoleonic Wars ended, the restrictions which had been imposed on maritime trade ceased, alleviating the trade crisis. International trade was able to resume, following the rules laid down by negotiated trade agreements. Corsairing was interrupted with the French conquest of Algeria in 1830. It was finally prohibited, in 1856, by the Treaty of Paris drawn up after the Crimean War.Footnote 85 At that point, the fraudulent sale of prize goods ceased but salt continued to be smuggled between Sicily and Calabria also after 1860, when Sicily, now part of a united Italy, was still granted a fiscal exemption on the salt it produced.Footnote 86

The illicit trading which flourished, thanks to the crisis in legal trade brought about by the Napoleonic Wars and the Continental Blockade, made Stromboli a port of call on maritime trade routes passing through the southern Tyrrhenian Sea, opening up new opportunities for the inhabitants and contributing additional income to their household economies. When normal trading conditions returned, the island remained an integral part of these trade routes until the 1880s, when the Aeolian fishing and commercial fleets became entirely marginalised.Footnote 87

Some interesting points regarding the different involvement of men and women in illicit trading remain to be discussed. It would seem that the size and type of goods being exchanged dictated which islanders participated in the different forms of illegal exchange.

Scholars have identified two kinds of smuggling: on the one hand, such activities were part of the ‘makeshift economy of the poor’, and on another they were much more organised and run by authority figures such as soldiers, clerics or customs officers.Footnote 88 Female participation in a smaller scale, ‘filtration’ smuggling through ports and across borders fits the former characterisation and has been found in many contexts, both maritime and non-maritime.Footnote 89 Anne Montenach, for example, suggests that poor women played an integral part in the calico smuggling which took place in many border areas of eighteenth century France.Footnote 90 Women do appear to have been involved in salt smuggling between Sicily and Calabria, but only in those areas, such as the Strait of Messina, where crossings were short and small quantities of salt could be transported in small rowing boats or hidden in the smugglers' clothing. Such operations had no need of the complicity of custom officials.Footnote 91 On Stromboli, the smuggling of salt and other commodities involved much longer crossings, and larger loads, requiring the collusion of a variety of officials. This activity, therefore, remained the preserve of the island's well-off menfolk.

Giovanna Fiume examined the records of crimes committed by women among the documents of the Sicilian Police force between 1819 and 1855. Following Arlette Farge,Footnote 92 Fiume describes the crimes as ‘banal’ or ‘workaday’.Footnote 93 The women's transgressions involved everyday objects, such as food or utensils; everyday activities, such as work or taking a daily walk; and everyday spaces. The latter included not just private or domestic spaces; as Cristina Vasta has noted, early-modern Italian women conducted their lives in and around the streets, courtyards, churches and fountains of their neighbourhoods.Footnote 94 In coastal villages and on the islands, women would also have frequented local beaches and landing places. By taking these aspects of life into consideration when studying the ways in which women on Stromboli participated in illicit trading activities, we must question the conclusions of those anthropologists studying the Mediterranean who believed that women in southern Italy were excluded from work and relationships outside the home because of an ‘honour and shame complex’.Footnote 95 Although the separation of the public and private spheres for women may have been an ideal, and was certainly to be found in the legal sphere, with wives under the authority of their husbands and women excluded from public office, this did not exclude the women of Stromboli and elsewhere in Southern Italy from being active in the economy and building up informal business relationships. Nevertheless, when the population resorted to illicit trading during the trade crisis created by the Napoleonic Wars, the institutional frameworks within which women in the region had to operate put them at a disadvantage as they were excluded from the most profitable transactions.