The 1970s is now widely recognised as a dynamic, foundational moment in the world's collective engagement with human-made environmental degradation, formally launched with the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) and the establishment of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) the following year. This was a moment when scientists, conservationists, activists, diplomats, international bureaucrats and computer engineers brought ‘the environment’ into focus as an object of international knowledge, government, and management.Footnote 1 The UNEP was established as what Maria Ivanova calls the ‘anchor institution’ for international environmental governance, although as Perrin Selcer has demonstrated, its origins and capabilities were decisively shaped by earlier post-war hopes and anxieties, Cold War geopolitics, and Global North-South conflicts.Footnote 2 These immanent tensions in international environmental institution building were not only geopolitical, but as Stephen Macekura and others have argued, also intellectual. Economists, demographers, futurists and other experts debated the appropriate measures and calculations of intersecting human progress, environmental conservation, and collective well-being.Footnote 3 And as Steve Bernstein, Iris Borowy and others have suggested, ‘sustainable development’ – the master concept of contemporary environmentalism developed in the early 1980s – is best understood as a mediation of these 1970s geopolitical and intellectual tensions.Footnote 4

This article further develops this evolving picture of intersecting ideas, institutions and individuals in the history of the fashioning of international environmental governance, and its shifting historical characteristics, by turning our historical attention to corporate actors, business associations and multinational corporations (MNCs). It sketches a new conceptual as well as institutional framework for conceptualising the relationship between ‘business’ broadly understood and international environmental governance. It also focuses on the genealogical importance of the 1970s moment epitomised by the UNCHE. In conceptual terms, this was a moment when the language of the ‘planetary’ – reflected in the idea that all humans share a common, terrestrial home – sat in increasing tension with the ‘global’ as a paradigm that referenced industry, commerce, and trade, the rise of multinationals, and transnational flows of money.Footnote 5 Although the subordination of the planetary to the global has become a defining characteristic of contemporary neoliberal globalism, we argue that the 1970s constituted a moment in which economists, social scientists and business leaders both espoused and negotiated planetary rationales, while navigating global alternatives.

Histories of early environmental governance have tended to focus on the role of non-government institutions, especially NGOs and IGOs, or the development of abstract concepts and norms.Footnote 6 By contrast, we take our historical cues from diverse individual actors in this international history, including British economist Barbara Ward, Italian industrialist Aurellio Peccei and Canadian oilman-turned-UNEP boss Maurice Strong. These actors’ networks and connections typify the alternative lens through which we view the formation and exercise of international environmental governance emanating from the UNCHE. People whose motivations are laden with telling ambiguities and ambivalences are at the heart of governance projects in ways not always apparent in the more formal study of NGOs or concepts. As a result, examining these networks has led us to uncover the significant involvement of business and corporations in the origins of international environmental governance.

The role of business and MNCs in early environmental governance is not well understood. While there is a growing literature on what major carbon emitting corporations ‘knew’ during this period, most scholarly attention on corporate contributions to international environmental governance has focused on instances since the 1980s in which business interests promoted market mechanisms as a preferred technique or even principle.Footnote 7 In this literature, the 1992 Rio Earth Summit is the apogee of ‘business’ influence over international governance frameworks for the environment and climate.Footnote 8 Meanwhile, management and business scholars are especially interested in developments since the 2000 UN Global Compact, a non-binding agreement between the UN and business to achieve sustainable development goals, critiquing things like the efficacy and politics – or even ‘green-washing’ – of corporate sustainability reporting, Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) self-assessments.Footnote 9 For others, it now appears that corporations and business leaders – rather than government – have emerged as providing the primary leadership and means for abating anthropogenic climate change. Alternatively, Bernstein, in his classic study of the rise of the discourse of sustainable development as providing a liberal ‘compromise’ between market and environmental ambitions, denies that business communities played any significant role in that process. Rather, they ‘consistently came late and often fought the compromises that eventually evolved into liberal environmentalism’.Footnote 10 Here, instead, we show that there is evidence of business influence on environmental governance from at least the 1970s in the context of the UN and its international system.

Although business proved a complicated and ambivalent affiliate for an environmental governance regime that was initially organised by the UNEP along inter-national lines, we are able to highlight their presence at this early stage, and to show just how the organisation of capital underwent significant transformation at this time, and the consequences for environmental governance. At a time when globalising, borderless MNCs were regaining their pre-Second World War status as predominant business actors, often represented by associations such as the International Chamber of Commerce, business was no homogenous actor. That said, business sought representation to have a voice, and it was sought after as a sponsor of international environmental governance. Some scholars have also noted that the Secretary-General of the UNCHE and UNEP's first Executive Director, Maurice Strong, was a Canadian oilman; what they have not recognised – as we recover – is how Strong mobilised his business and corporate networks to incorporate industry and MNCs into the work of international institutions developing approaches to environmental governance, not least their goal of harmonising environment and development.Footnote 11 Business actors – and their underlying personal networks – engaged the contested place of environmentalism in the history of twentieth-century capitalism, and led the general transition from planetary to global framings of international environmental governance.

Recovering the 1970s ‘planetary’ history of business and international environmental governance is of considerable contemporary relevance to contemporary scholarship across the social sciences and in public discourses.Footnote 12 In recent years, this history has gained added salience as scholars turn to a new conceptualization of the ‘planetary’ as a means of grasping the socio-political world and its complex dynamics, whether as ‘planetary boundaries’, or ‘planetary health’, and to challenge prevailing ideas of global connection provided by economists and business leaders, usually as globalisation.Footnote 13 At its most radical, ‘planetary’ denotes a recalibration of the ordering frame through which we understand the world, replacing other concepts that have served this role, such as ‘international’ and ‘global’.Footnote 14 We argue that early 1970s business involvement in environmental governance is historically connected to earlier self-consciously planetary critiques of the existing socio-capitalist orders. As we note in our conclusion, by the 1980s the rise of the neoliberal formula of ‘sustainable development’ coincided with a global language that superseded the political possibilities of this earlier era of specifically planetary thinking. While this global language acknowledged the limits of purely inter-national interactions in the face of environmental challenges, it eventually stymied the possibility of a radical questioning and rethinking of the international statist and capitalist order. Our focus here is not on adjudicating this process, but recovering a moment of transition, of conceptual possibility and institutional experimentation. In this way, we offer a different slant to Dispesh Chakrabarty's history of the interconnections between globalisation and global warming. Chakrabarty argues the domain of the planetary (or Earth-time and Earth-systems) became knowable to scientists due to the intensification of global capitalism. We show how pre-eminently global actors were implicated in both constructing and diluting an earlier iteration of planetary thought in the context of the 1970s institutionalisation of environmental governance.Footnote 15

The interplay between planetary and global framings of environmental governance provides the framework for this history of the activities of personalities, institutions and business tackling environmental questions. In the first section, we examine the nature of 1970s planetary thinking through the writings of Ward, who was a critical member of Maurice Strong's international networks, and herself seconded into the organisation of the UNCHE, and business leaders, such as Peccei, who helped define the UNCHE's development agenda. We survey the ways in which, in this institutional context, the cohorts of ‘business’ and ‘industry’, and the multinational corporations these classifications increasingly represented, engaged these same intersections of environmental and economic concerns by invitation and by design. Second, we examine how the UNCHE's outcome, UNEP, led by Strong, attempted to institutionalise the interplay between the planetary and the global in the form of the UNEP Industry Programme, which brought together international business associations and MNCs in seminars and workshops to develop environmental guidelines for industry. Returning to the origins of international environmental governance manifest in the 1972 UNCHE in Stockholm and the activities of the UNEP in Nairobi, we argue, reveals a remarkable moment of transition, from the planetary to the global, and from an idea of international institutions representing states to the rise of multinational ‘business’ as a crucial authority informing the launch of international approaches to environmental governance. We conclude by considering some of the possible pathways from our depiction of the 1970s to understanding the present.

A Planetary History

As historians reflect on the UNCHE's fiftieth anniversary, the conference is increasingly cast as an originary moment in the genealogy of international environmental governance. Eventually held in June 1972, the UNCHE was first proposed by Sweden at a UN General Assembly four years earlier, ‘to encourage and to provide guidelines for action by Governments and international organizations . . . to protect and improve the human environment and to remedy and prevent its impairment, by means of international cooperation’.Footnote 16 Its special mission was to enable developing countries ‘to forestall the occurrence of such problems’.Footnote 17

At this same moment, in the lead-up to Stockholm, the UN Secretary-General U Thant called for a planetary imagination that could match ‘the realities of the present-day world’.Footnote 18 Famously, the circumstances encouraging that reimagining were in part technological, not least the space race that beamed back a vision of planet Earth as a precious blue marble hanging in an infinite space. This same planetary imagining shaped the thinking of individuals involved in organising the UNCHE, most prominently the English-born economist Barbara Ward, who was at the time the Albert Schweitzer Professor of Economic Development at Columbia University. In Spaceship Earth, published in 1966,Footnote 19 Ward connected planetary imagery to questions about social justice and what she called ‘The Balance of Wealth’. The extremely well-connected Ward also used her networks to spread her ideas, including by ghost-writing a well-known speech delivered by Adlai Stevenson II, US Ambassador to the UN, in 1965 at UNESCO, in which he spoke confidently of a ‘world society’, ‘the planet earth and nature, along with man and his works upon the planet’. In the context of the UNCHE, Ward's reputation as someone who tackled the intersections of environmental and economic issues made her the person the UN turned to help prepare for Stockholm. She was specifically tasked with drafting Only One Earth that would provide ‘a conceptual framework for participants’ at the conference, ‘and the general public as well’.Footnote 20 What is significant for our purposes is the connection at this point between this planetary language and a specific economic view, announcing the limits of the market, the threat of permanent growth, and the importance of taxing externalities.Footnote 21 Only One Earth echoed her earlier planetary thinking, hinting already at the importance that innovative economic policies had in enabling a planetary imagination. Her favourite words were ‘planetary order’ and ‘planetary interdependence’, concepts Ward believed captured the facts of a shared biosphere.Footnote 22 Humankind also shared what she variously called a ‘planetary society’, a ‘planetary community’ (or ‘ecumenopolis’) and a ‘planetary economy’, in which no nations in the world were outside the network of trade and investment.Footnote 23 She ended by emphasising the importance of making ‘the planet . . . a centre of rational loyalty for all mankind.’Footnote 24 Indeed, mankind needed to learn ‘planetary modesty’ if ‘his human order is to survive’.Footnote 25

These planetary themes were also struck by the spokesperson for the NGO Forum at the Stockholm meeting, the elderly anthropologist Margaret Mead, who was Strong and Ward's friend. Mead's emphasis was on the danger posed to ‘our planet’ by ‘the way in which we use our technology, the way we produce energy, the way in which we treat the land, exhaust the resources and abuse and deprive half of the planet's population. . . . Beside the picture of danger and the picture of injustice, we must place a picture of what is now possible, as it has never been before, for man to become’.Footnote 26

Planetary language and framings were as much on the mind of the businessman Aurelio Peccei, one of the most influential voices at Stockholm. Peccei too emphasised the importance of planetary thinking. Man had a responsibility as the ‘governor’ of ‘Spaceship Earth’ to prevent the overexploitation of nature, ‘or what is left of it’. He even brokered that ‘individual initiative and profit must become subordinate’. This was despite his long business career, working for Fiat and the Italian industrialist Agnelli in pre-communist China and then Latin America, as Vice-President of Olivetti, and the overseer of a private development bank.Footnote 27 In 1968, he had translated his business connections into the creation of the (still-surviving) think-tank the Club of Rome. Many members of the Club of Rome, which gathered ‘some thirty European scientists, economists and industrialists . . . to discuss global problems’, were also involved in Peccei's commercial entrepreneurship.Footnote 28 However, it was Peccei's role in the conception and production of the study Limits to Growth,Footnote 29 that earnt him Ward's invitation of an opening slot at the UNCHE's ‘Who speaks for the Earth?’ lecture series.

Eventually, Limits to Growth came to define the Stockholm mantra more effectively than Ward's own Only One Earth. Strong would describe ‘The Limits to Growth idea’ as supporting ‘the whole concept of Stockholm, that is, the growing need for man to acquire the economic and social and political instruments to deal with new interdependencies.’Footnote 30 Peccei's motivations, like Ward's, were neo-Malthusian; they also continued the emphasis on the planet's limited capacity to sustain growth, and the limits of the market as a guide to environmental policy.Footnote 31 Indeed, Peccei's planetary thinking, like that of Ward and Mead, is evidence of the complex conceptual context in which the UNCHE took place. It is important to note, for all the variety of discourses, Stockholm discussions acknowledged the earth's fragility, and the 1972 conference briefly manifested a popular as well as scientific and governmental engagement with these issues. It inspired economic solutions grounded in equity questions, with an eye to social justice across the planet as well as within nation-states. Ward and Mead captured this mood in their promotion of the Stockholm conference as the ‘starting point for a new sense of planetary realism – beyond our narrow nationalisms, our divisive ideologies, our gulfs of wealth and poverty’. Both Ward and Mead wanted this planetary realism to acknowledge that ‘all human life, black, white, communist, capitalist, wealthy . . . depends for sheer survival on the health, fertility and balance of the earth's life support system, on the oceans, air, and climates, on the soils and harvests which we all have to share and which we can irretrievably damage. This is the ultimate rationale for world cooperation’.Footnote 32

Even as the planetary conclusions of Limits captured corporate imaginations like those of Peccei, they elicited strong criticism from mainstream economists and corporations – including Robert Solow in academic journals and oil giant Mobile in whole-page newspaper advertisements.Footnote 33 In 1974, oilmen proceeded to create their own environmental body, the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA). The following year, oilman and real estate developer George Michell sponsored a gathering of economists, experts, politicians, policymakers and business leaders, including Carl Madden, the chief economist for the US Chamber of Commerce, and Sicco Mansholt, the former president of the European Common Market, to discuss the findings of Limits. Mitchell offered a cash prize for the most promising research on transitioning to a steady state economy.Footnote 34

Against this background, it is no simple matter to dissect the influence Peccei exerted on the UNCHE's conceptual framing. On the one hand Peccei equally bemoaned the privileging of markets over the environment and implied that the problem of sustainability and limits to growth was a problem of the Global South desiring the same prosperity as the Global North. On the other hand, he had a close relationship with the UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim, significant enough to arouse consternation in the UN bureaucracy.Footnote 35 At the same time, the UN as an institution was eager to attract the support of business in this same period. Ward and Mead also understood ‘business’ as having critical roles in achieving their environmental objectives.

Then there are the other strands of contemporary radical rethinking of modern conceptions of human relations with the environment in play at that time. The language of ‘spaceship’ and ‘limits’, found also in the work of Kenneth Boulding, were varieties of such rethinking.Footnote 36 As geologists and natural scientists reconceived the planet as an integrated system, a ‘biosphere’, social scientists pushed hardline critiques of the ‘growth paradigm’ and resource use in mainstream economics.Footnote 37 Paul Ehrlich predicted a ticking ‘population bomb’ and Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen recast the foundations of economics with the laws of entropy and thermodynamics.Footnote 38 What is striking is that in the midst of this broader individual and institutional context of the UNCHE, transnational businesses were curiously present at international environmental governance forums since the very beginning of the 1970s, and they had a say in how that governance was conceived and conducted. Here too, there were other contexts that might have prepared the terrain for this input. For example, environmental issues were being incorporated into business forums in national settings. The Second Clean Air Congress in 1970, comprising mostly UN, NATO and US representatives, was also attended by Standard Oil chairman John Kenneth Jamison and the director of a large American electronics engineering firm, TRW Inc. In the early 1970s, the conservative US-based Hudson Institute held conferences across the United States, Europe and Japan on the Futures of the Corporate Environment, which promoted ‘corporate scenario planning’ to deal with uncertain technological, social, cultural and environmental ‘futures’.Footnote 39 The Association for Education in International Business, a business think tank, debated the implications of Stockholm for multinational enterprises in their December 1972 meeting in Toronto.Footnote 40 In the immediate aftermath of Stockholm, Strong encouraged the Paris-based Centre for Education in International Management, of which he was a board member, to develop a special programme that would aid chief executives’ in thinking about how multinational companies should handle their environmental responsibilities.Footnote 41 In 1976, the Conference Board, an American-based business and research organisation, convened a symposium on ‘Environmental Protection’ to debate the mechanisms and costs of environmental regulation. The following year, the Brookings Institute ran a conference in Bellagio, Italy, on ‘New means of financing environmental and other international programmes’.Footnote 42 These reflect only a smattering of examples evidenced in Strong's papers alone. Elsewhere, there were new institutions researching the intersection of business and environment: the International Institute for Environment and Society (Berlin), the Centre international de recherche sur l'environnement (Paris) and the Centre d'etudes Industrielles (Paris).Footnote 43

It is not surprising that representatives from a range of implicitly transnational and explicitly multinational ‘business’ and ‘industry’ interests thought it important to participate and have a voice in a process that would set an agenda for environmental issues that impacted them. What is surprising is that their presence and influence, particularly in European settings, was neither uniform nor unilateral. It involved a range of often competing, or at least multiple, motivations and interests, some of which resonated with planetary thinking. In March 1972, business interests groups participating in Stockholm identified with the Association of World Federalists met at St. George's House Windsor Castle to contemplate the UNCHE. There, the president of Business International Inc. N.Y., the vice-director of Pharmaceutical Division Biological Research, CIBA-GEIGY, Ltd., Basel, and the senior consultant to Royal Dutch/Shell Group of Companies on Environmental Conservation, who was also a member of the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution, UK, criticised the forthcoming UN conference for its ‘too modest’ approach given the ‘magnitude of the rapidly accumulating problems of environmental degradation’.Footnote 44

Just as business representatives were part of the delegations of some countries, international business associations and federations were among the 700 accredited NGO observers partaking in the UNCHE. This included the The International Chamber of Commerce [ICC] – a Paris headquartered NGO that was omniscient in this early period of international environmental governance with heightened advisory status at the UN, more so than the European Economic Community at that time.Footnote 45 Born of a movement that, in the early twentieth century, intentionally mirrored the League of Nations, the ICC was an early ally of the Geneva school of neoliberals with ambitions to legally constitute a global economy of free-flowing capital that transcended democratic nation-states.Footnote 46 However, in the 1970s, its leaders too echoed the kind of planetary concerns the UN movement had tabled. The ICC set up its own special environmental committee at its annual meeting in Vienna in anticipation of Stockholm. Adding to its observer status at the 1972 Conference, the ICC intended to extend the activities of its own environmental committee by serving as a conduit between international business, the UN's emerging environmental program and national governments.Footnote 47 Prior to Stockholm, ICC executives arranged a meeting in Gothenberg at which they called for the urgent establishment of an official link with the UN unit working on the environment. In February 1972, they co-sponsored business leaders briefings in Paris and at UN Headquarters in May that same year. At both briefings, funded by US companies such as American Metal Climax and Continental Can, Maurice Strong set forth the central aims and likely consequences of the UNCHE.Footnote 48

It was through the ICC that business had a voice in commenting on Ward's first draft of Only One Earth. The ICC led the UN to the views of the president of Imperial Oil (Canada), the chair of Bayer (West Germany), the executives of Nippon Steel Corporation, Scandinavian Airlines System, Fiskeby (the Swedish pulp and paper group), Shell Chemicals (London), Tata (New Delhi), and the Ford Motor Corporation (Michigan). Most accepted the need for an antipollution mentality but wanted it balanced with the need for economic growth. The LSE-trained researchers at Bombay-based Tata Industries’ Department of Economics explored how ‘the preoccupation with economic growth at any price with its emphasis on “full-employment” [had], if anything, aggravated rather than corrected the ecological imbalances inherited from the previous century and a half of industrial development.’ Contrary to Shell, which wanted a critical analysis of ‘the real dilemma that we all face – whether economic growth is compatible with improving the environment’, the Tata sociologists preferred an antipollution mentality ‘without frustrating the legitimate demands of rapid economic growth.’ Even so, they acknowledged forecasting based on GNP had to be reoriented ‘to an intelligent anticipation of “the chain and side effects” of this process.’Footnote 49 What we learn from this evidence is that criticisms of the text of Only One Earth had little impact on its final version, and that while industry multinationals were the key businesses represented, and in some settings they went on the defensive. Preferring to protect their industries, in others, at this stage at least, their own delegates might call for more ambitious environmental targets, on planetary grounds.Footnote 50 In the next section, we survey the ways in which, after Stockholm, the cohorts of ‘business’ and ‘industry’, and the multinational corporations these classifications increasingly represented, engaged these same intersections of environmental and economic concerns by invitation and by design.

From the Planetary to the Global

From the outset, the ambitions for international environmental governance were in tension with the dominant ambition of international institutions, namely development. This reflected both the legacy of the UN's own historical raison d'etre and postcolonial priorities. As a result, by the late 1960s, conflicts had emerged between environmental growth critics and Third World intellectuals and government officials, who while acknowledging environmental arguments, wished to promote poverty reduction and industrialisation.Footnote 51 These same tensions shaped the UNCHE, which was born of a 1969 resolution that required the accommodation of development. Indeed, countries such as Brazil and India argued they would be unfairly hampered by any proposed international environmental protection schemes.Footnote 52

In 1971, Strong pursued his mandate as Secretary-General of the UNCHE by attempting to reconcile developing nations’ rights to growth with aims of environmental protection, drawing in business. He organised a Panel of Experts on Development and Environment in Founex, Switzerland, that included economists, development bank officials and other national representatives. The group settled on antipoverty as a key platform of the forthcoming conference. After Stockholm, UNEP. led by Strong. funded a second gathering of Third World intellectuals and leaders at Cocoyoc, Mexico, at the Symposium on Patterns of Resource Use, Environment and Development Strategies, dubbed ‘Founex II’, with the aim of reconciling environmental and development interests. Barbara Ward, who Strong invited to chair the symposium, was lead author of the final Cocoyoc Declaration. The document categorically defined development as not the Third World playing economic ‘catch up’ with the Global North but, rather, as consistent with the UN's 1974 proclamation of a New International Economic Order [NIEO], which prescribed resource sovereignty for postcolonial states and regulation of multinationals (but not limits on growth). The aim of Founex II was an economic self-reliance that balanced, as Ward wrote in her now-familiar terms, ‘the “inner limits” of basic human needs and the “outer limits” of the planet's physical resources’.Footnote 53 While issuing support for the NIEO claims of the ‘Third World’, Strong and the UNEP maintained the cooperation of the rich North in investment-intense economic programmes, promoting market mechanisms as the appropriate approach to environmental management.Footnote 54

Against this same background of shifting geopolitical and economic realities, and policy emphases, Strong used UNEP's so-called ‘Industry Programme’ to pursue a balance between environment and development, North and South, markets and resource sovereignty. Nairobi-based UNEP was itself a product of the Stockholm conference, a new international organisation intended to focus on the environment, and symbolically located at the centre of international development activities. Drawing on Strong's rich business networks, especially at the ICC, the new UNEP's industry programme cultivated a space of intersecting environmental and development practice. This project effectively began in mid-1973, when Sir Duncan Oppenheim, chairman of the British National Committee of the ICC, announced that a proposed joint ICC-UNEP International Centre for Industry and Environment (ICIE) was to be established in Paris in the coming months, with a branch also at UNEP's headquarters.Footnote 55 Oppenheimer slated the new centre as a ‘clearing house of information on environmental problems and a channel of communications for all the various private bodies concerned’. Later that year, ICC chairman John Langley – also a board director of the tobacco giant, Imperial Group – arrived in Nairobi on Strong's invitation to establish the branch attached to UNEP. ‘We think businessmen are constructive and responsible people’, Langley told journalists on his arrival. ‘If Mr Strong has a problem on say, marine pollution, we can get all the relevant men together. Equally, if some over enthusiastic environmentalist wants to introduce measures that might have adverse reaction, such as massive unemployment, in developing countries, we can point that out’.Footnote 56

Initially, it was planned that members of the ICIE – and the ICC-UNEP relationship more generally – would comprise international business associations representing specific industries worldwide as well as national bodies representing domestic business.Footnote 57 This assumption reflected the structure of mid-century international business. Between the Second World War and the 1970s, national federations and international business associations, led by the ICC, and not multinational corporations were the chief modes for organising capital. That is, organised capital was nationally and internationally organised.Footnote 58 The ICC's Charles Dennison was appointed as a senior advisor to UNEP to help identify relevant bodies, while Strong wrote personally to almost a dozen secretaries of various international federations (all based in Europe), covering agribusiness, superphosphate, chemicals, automobiles and manufacturing.Footnote 59

Within three years, the ICIE had seventeen full members consisting of various international industry federations, all headquartered in Europe or North America.Footnote 60 Yet it also soon became clear that the resurgent multinational corporations would need to be recognised in the programme. At the same moment UNEP was established, the Bretton Woods international order of pegged exchange rates and capital controls was coming undone, triggered by innovations in Eurobonds and offshore tax havens. These circumstances encouraged the re-emergence of foreign investment and multinational corporations. Large and integrated corporations were relocating their manufacturing operations to developing economies while new service, consultancy, and finance multinationals emerged across the Global North. A globalist economy of complex supply chains and capital flows was coming to challenge the mid-century world of managed national economies, and even national sovereignties.Footnote 61 Accordingly, when Strong asked the ICC to assemble the cooperation of six major industries – pulp and paper, iron and steel, chemical and pharmaceuticals, automobiles, petroleum, and agriculture – that UNEP might work with, it was predominantly multinational corporations rather than business associations that were contacted. From the outset, there was a tension as to whether international institutions or these resurgent multinational global actors were best suited to meeting the UNEP's planetary aims.

When Strong pitched the UNEP's Industry Programme to the first UNEP Governing Council in June 1973, he identified ‘the environmental problems of specific industries’ as one of five areas in which the UNEP Secretariat were conducting preliminary work for the council's consideration.Footnote 62 He appointed his friend, Baron Leon de Rosen, who had headed up the French union of sugar manufacturers, Syndicat National des Fabricants de Sucre, to lead the industry programme. In May 1974, Rosen drew up the first terms of reference for the programme, which was instituted in 1975 as the Industry and Environment Office and based in Paris, neighbouring both the OECD and ICC.Footnote 63 Rosen set the office a wide scope of investigation, including not only ‘industry nuisances’, such as pollution and noise, but labour, consumer relations, trade and development. He imagined the office would investigate tensions between anti-inflation price control and environment investment costs, the energy crisis and environmental issues, natural versus synthetic products and the international division of work.Footnote 64 In establishing such wide parameters, Rosen was perhaps overly conscious of the concerns of some delegates to UNEP's second Governing Council a month earlier, who, while endorsing the consultations between UNEP and the ICC, stressed final decisions ‘lay with governments’ and consultations should be conducted ‘not only with industrial managers’, but unions and employees organisations.Footnote 65

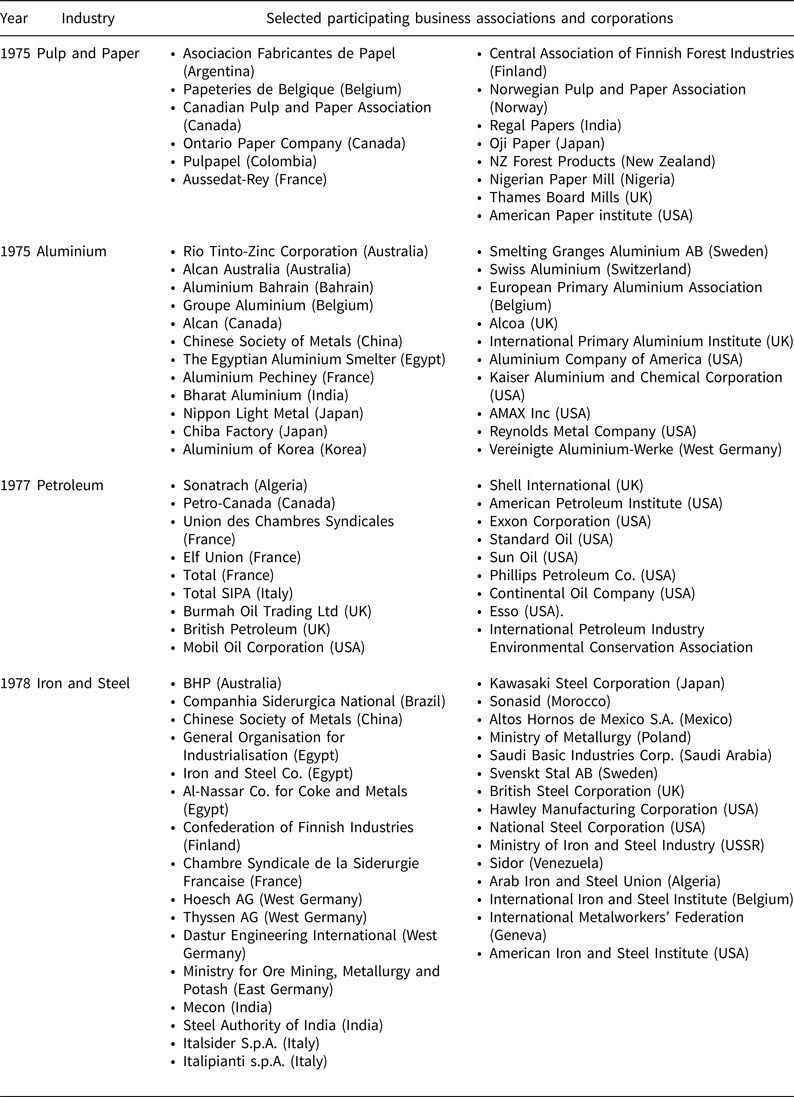

The main activities of UNEP's Industry Programme were a series of industry sector seminars. These were conducted for the pulp and paper industry (Paris, March 1975), aluminium (Paris, October 1975), motor vehicles (Paris, December 1976), agriculture, (Rome, January 1977), petroleum (Paris, March 1977), iron and steel (Geneva, October 1978) and chemicals industry (Geneva, May 1979).Footnote 66 The seminars were evidently the product of the enthusiastic network Strong and others had been cultivating since the early 1970s, including with the president of the World Bank, Robert MacNamara, (another member of Ward's close circle). Indeed, the first two seminars were held at the offices of the World Bank in Paris, giving the program global importance. Participants at each seminar involved delegates from national government departments and agencies; ministries of the nationalised industries in the USSR, Poland, East Germany; IGOs, including the OECD and ILO, other UN bodies, especially the UNECE and UNCTAD; and, of course, the business associations and firms coordinated by the ICC's ICIE. These actors were largely dominated by North American and European actors, but as is reflected in Table 1, they captured a smattering of firms from Australia, Asia, Africa and South America. Representatives from the ICIE's full members, including the German Industries Federation, Netherlands Industries Federation, Confederation of British Industries and the International Iron and Steel Institute, attended all seminars.

Table 1. Participating business actors at selected UNEP Industry Programme seminars, 1975–8

The aims of the seminars reflected UNEP's overarching goals of mediating between environment and development. As Rosen told the pulp and paper industry seminar, its programme was a ‘consultative process between UNEP and industry on problems of environment’, where environment was understood not simply as pollution abatement, but the integration of human health and economic and social effects. Rosen said the task of governments and producing companies was to discuss how ‘the human environment can be improved and the earth's resources used prudently, while permitting industry to make its vital contribution to society and the economy with minimum cost and disruption’.Footnote 67 The general plan was for participants to find points of agreement on collective action needed by national governments, and compile a set of recommendations which the UNEP Executive Director would then submit to the annual Governing Council for adoption by individual nations. At the same time, it was assumed the industry federations would take the agreed recommendations back to local firms in their respective nations, seeding a grassroots process whereby board members of local companies would submit recommendations to their own governments.Footnote 68 It would be a properly consultative, collaborative multi-directional process, with several points of buy-in for affected parties. More strikingly, however, the seminars’ main participants and audience – individual corporations and firms – had ambiguous roles in reporting, recommending, and implementing.

In practice, the nuts and bolts of the seminars were prosaic, aimed at information sharing. Nonetheless for Strong, Rosen and others, this went to the heart of the Industry and Environment Office's mission. It soon became apparent the seminars were best suited to surveying different national environmental regulations and their underlying rationales, and promoting environmental concerns and priorities. Participants devised mechanisms for sharing non-proprietary technologies for pollution abatement and control, along with analytic methods and management tools that evaluated the cost-benefits of pollution control. The seminars also provided a basis for working with agencies such as the International Standards Organisation to develop monitoring goals. The UNEP's Governing Council was impressed with the potential of this information sharing, which cut through North-South divides. The Governing Council requested that the Industry and Environment Office produce standardised guidelines for the use of governments and industries to minimise adverse environmental effects – including public health effects – of major industries.Footnote 69 Further consultative committees followed each seminar, which in turn produced overviews, technical reviews, manuals, and guidelines for industry-specific environmental management.Footnote 70 By the late 1970s, the Industry and Environment Office had established computer data bases containing bibliographic references and technological standards to enhance information transfer.Footnote 71

The industrial seminars therefore reflected the general logic of UNEP's programme of environmental assessment, management, and support measures.Footnote 72 For Strong, this logic had been refined to a single concept: ‘ecodevelopment’. The intellectual history of this term remains shadowy, partly because unlike its successor, ‘sustainable development’, its ambiguities were ultimately obfuscating rather than unifying.Footnote 73 But in the early 1970s, ‘ecodevelopment’ served for Strong and others as a variation on planetary thinking – consistent with Ward's ‘spaceship’ or the Club of Rome's ‘limits’. Strong had first coined the term in a report to the UNEP General Council in 1973 as one of five areas of investigation. Here, ecodevelopment was intended to designate the specific legal and labour problems faced by rural as opposed to industrial societies. Strong's colleague, the Polish-born French economist Ignacy Sachs, extrapolated the concept into a more capacious category that captured the UNCHE's essential finding (at least in Sach's opinion): ‘that far from being antithetical, socioeconomic development and environment are but two different facets of the same concept’. Ecodevelopment, said Sachs, was about the ‘rational management of resources in order to enhance the global habitat of man’. It ‘implied’ a ‘special technological style’ – or ‘ecotechniques’ – and a ‘pattern of social organisation and a new education system . . . In short, a style of development’.Footnote 74 A few years later, Sachs elevated the concept to a general theory of development resting on three pillars – self-reliance, needs-oriented production harmonising development with environment, using emerging technologies to provide solutions – and addressing the key questions of participation, education, organisation, access, urban planning.Footnote 75

Such framing was clearly vague, but useful for the UNEP's early projects. It departed from both the inhibitive neo-Malthusian and anti-growth rhetoric of some planetary thinking, and the anti-market rhetoric of the NIEO. Ecodevelopment was also some distance from inferring that market mechanisms were the most appropriate option for achieving environmental protection, as the OECD was beginning to promote, and which ‘sustainable development’ would eventually codify. Rather, consistent with Ward's ideas of inner and outer limits, ecodevelopment proposed economic growth within recognised environmental constraints. For Strong, the industry seminars practised this thinking. As he told steel and iron producers, the seminars were intended not to discover ‘general cures’ – each nation's environmental, raw material, labour and regulation circumstances were too different to achieve ‘absolute standards’ – but were an interface for mediating the tensions in the contrasting goals and responsibilities of government and industry in different parts of the world. Where governments, Strong said, were concerned primarily with human health, industry had the goal of economic growth as its principal responsibility. In both respects, ‘environment’ was no longer a ‘add-on and add-in stage’, but central to both human health and economic growth.Footnote 76

Overall, the seminars were characterised by two features that reflected shifting attempts to reconcile environment and development, planetary and global concerns. First, they situated each industry as pushing at different points in the Earth's ‘outer limits’ and determined ways this might be diminished. Paper manufacturers worked through issues of water consumption, the effluent discharge of toxic products and the emission of air pollutant chemicals. Aluminium producers were concerned with fluorides, hydrocarbons, and the solid waste disposal of bauxite residues from the production of aluminium, as well as the difficulties of recycling aluminium products and lower energy techniques. Agriculturalists discussed residue utilisation strategies of the by-products from commodity production. Petroleum producers focused on the issues that arose with the sequence of extraction, transportation, and refining. Automobile makers dealt with air pollution. Rather than calculating a given industry's carbon emissions or greenhouse effects – nascent concepts at this time – the activities of industry were grounded in their observable impacts on their immediate ‘environment’.

The second feature of the seminars was the the UNEP's treatment of business. The consultative approach of the Industry Programme, which encouraged industry to design their own guidelines, contrasted significantly with the command-and-control environmental regulations nation-states were imposing on local industry. It also differed from the disciplinary approaches of intergovernmental organisations – including other UN agencies – to multinational corporations in the early 1970s. For many intergovernmental bodies, the floating of the dollar, a series of corporate bribery scandals, the oil crisis and self-determination of the Global South raised questions about how resurgent multinational corporations should be regulated in the international community. The most strident response was the NIEO's calls for resource sovereignty and restrictions on the activities of multinational corporations.Footnote 77 More moderately, in 1974, on the recommendations of Agnelli no less, the UN established a Centre on Trade and Corporation (UNCTC) that, over the next two decades, would attempt to have multinationals subscribe to a global code of conduct.Footnote 78 At the same time, the ICC, OECD and ILO all developed guidelines for multinational conduct too.Footnote 79

While promoting business engagement on environmental protection broadly, the UNEP's own relationship with MNCs, specifically, was not so straightforward. As noted, the Industry Programme's approach was underpinned by Rosen's tactic of engaging national and international business associations, especially through the ICIE. The ICIE liaised between international industry and intergovernmental organisations for the UNEP's consultative groups on the International Register of Potentially Toxic Chemicals and the Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution – two of UNEP's major achievements in the 1970s.Footnote 80 The UNEP Governing Council delegates from both North and South approved the ‘consultative process on environmental aspects of specific industries’ and suggested the seminars be extended to South Asia, which the UNEP delivered in Thailand in December 1979.Footnote 81 Meanwhile, with UNEP support, the ICC led an East-West conference on the cost-benefits of environmental protection in Moscow in 1980.Footnote 82 In this setting, however, the designated role and agency of individual corporations remained more circumspect, dependent on the coordination of business associations that held sway in the expanding domains of international environmental governance. This ambiguity in calibrating the multinational corporation with planetary thinking provides perhaps one explanation for the eventual triumph of a global paradigm.

Towards a Conclusion

In 1992, Susan Strange observed in International Affairs that multinational corporations were assuming the role of ‘firm diplomacy’, or ‘firm diplomats’. While transnational business engagement in world politics was nothing new, and merchants, bankers and business leaders had organised and represented their interests on a global stage for centuries, the mature multinational corporation was beginning to represent a different kind of force in world-making, one that could perhaps even challenge nation-state sovereignty.Footnote 83 Though Strange did not refer to it, she might well have been talking about events at the Rio Earth Summit that year. Among much else, Rio 1992 has become synonymous with the new alliance between corporates and government on environmental action, and a high watermark in the international governance of climate change. For some, it achieved the necessary ‘liberal compromise’ to engage big business in environmental action. For others, it marked the beginning of a subordination of environmental concerns – and what we have defined as existing planetary thinking – to the imperatives of corporate globalism. Indeed, the perspective we have been sketching in this article poses a different set of questions about a longer history and alternative alignments of corporate and environmental governance.

By the 1990s, the global had superseded planetary thinking, all but eradicating the legitimacy of alternative economic scenarios of environmental governance, particularly no-growth and anti-market stipulations. Our aim in this article has been to develop a perspective that questions not only the inevitability of this outcome, but also to demonstrate that key actors in the history of environmental governance attempted to do more than deliberate or prosecute an either/or choice between markets or no-growth in managing the interlinked challenges of environmentalism, economic development and poverty eradication. By re-assessing the moment around the 1972 UNCHE in Stockholm, as preserved in Strong's papers, in terms of the interplay between ‘planetary’ and ‘global’, we have begun to excavate a moment of considerable conceptual and institutional experimentation that attempted to transcend the existing international reality to meet these challenges. A key discovery of this re-evaluation of the 1970s has been to highlight the prominence of business and corporate actors from the outset of the environmental movement. As we have demonstrated, globally-minded business actors (together with economists) were influential in contributing to the first era of planetary thinking – including ideas of Spaceship Earth, the Limits to Earth, Only One Earth, or ecodevelopment – and participating in new institutional frameworks, such as the UNEP Industry Programme.

According to Bernstein, concepts such as ecodevelopment failed to gain traction because they were difficult to translate into concrete measures, while their emphasis on self-sufficiency could not square the global political economy of North-South conflicts. Sustainable development, by contrast, was capacious and malleable enough to capture the imagination of environmentalists, planners, industrialists, and governments, and to equally accommodate market and environmental concerns. Our argument emphasises that personalities and institutions mattered as much as norms. The ambiguity of Ward's thinking and agency, the Club of Rome and the UNEP Industry Programme in their various projects to accommodate resurgent multinational corporations suggests a clear weak spot in the UNCHE moment. Crucially, the 1970s were an era of new forms of globalist business association – the European Management Forum (now World Economic Forum) from 1971; the Business Roundtable from 1972 – which challenged the established pattern of twentieth-century international business associations, including the ICC. From this perspective, a successful interplay of the planetary and global meant more than reconciling environment and development, or even North and South, as had absorbed Ward and Strong during the early 1970s.

Importantly, we show that the complicating factor in this moment was re-emergent MNCs. These corporate actors, which today are central to contemporary thinking about environmental governance, were only returning to global prominence from the late 1960s as the strictures of the post-war Bretton Woods order came undone. Corporations were central contributors to a language of planetary environmentalism, and then the UNEP Industry Programme where seminars and their outcomes focused on meeting industry-specific challenges to be regulated at a national scale, as approved by the UN Governing Council. For UNEP, national and international business associations, rather than MNCs, were treated as the natural leaders of industry. As the various efforts at this time to regulate resurgent MNCs – by the UNCTC, the OECD and others – along inter-national lines indicated, the distinctive nature of late-twentieth-century MNCs and the globalist logic they reproduced was not yet fully comprehended. The UNEP Industry Programme was no different, and by the 1980s there was a shift to alternative frameworks to accommodate these actors. The key sites of these developments were not by accident European, but the domain of action and thought was significantly trans-regional as much as transnational, a characteristic which came to define the period, and which complicates the writing of both economic and environmental histories.Footnote 84 Today we see again an interplay of planetary and global which might hold the chance of exploring the planetary path already imagined in the 1970s.

Our lens has resolutely been one of capitalist connections to environmental and climate issues via the United Nations. Focus on other institutions and individuals may take the story of planetary and global thinking in other directions. The well-known conceptual history of ‘sustainable development’ suggests there are further threads that need tracing back into the 1970s and to the actors and institutions we have been discussing. Sustainable development had its first formal expression in the UN-commissioned Brundtland report, Our Common Future (1987). However, the idea had already been toyed with at the Economics and Environment conference in 1984 hosted by the OECD, which began developing a market-based approach to environmental protection in the early 1970s. As we have seen, at the Club of Rome, Peccei invoked the failure of markets and money to guide environmental policy, but also preferred to talk about ‘limits of growth’ rather than ‘no-growth’. By the time UNEP hosted its World Industry and Environment Management conference in 1984, it, too, was promoting the language of ‘sustainable development’ and embracing global markets as a solution to environmental protection. The threads between Stockholm and Rio, through the organisation of Europe-based seminars and societies, and the transition from planetary to global thinking – and more importantly, the space and interplay between them – are complex and replete with alternative possibilities. Business agency and influence took multiple forms, but notably, it was sought out by the UN, and through individual transnational business actors extended across the problem of development. It rendered the international governance of the environment an integral part of the global history of capitalism, with its privileging of markets, reconfiguring the international, planetary and global as more simply, and reductively, globalisation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank three anyonymous reviewers, the special issue editors, and Professor Thomas David for comments, feedback and advice on earlier drafts of this article. Research for this paper has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 885285).