The readers of Quick, a glossy West German weekly, were treated to sensational news when they opened one of its late summer issues in 1951. ‘I know again what was there . . . Hypnosis restores memory of a returnee from Russia’, read the headline of a feature, which centred on Heinrich Gerlach, a former officer with the German Sixth Army that had been encircled and annihilated during the battle of Stalingrad in the winter of 1942–3.Footnote 1 During his years in Soviet captivity Gerlach had written an autobiographical novel detailing his experience of the encirclement and defeat of the German army. When he was freed in 1950 he was not allowed to take the manuscript with him. Two other copies of the novel that he had produced, one of them a small notebook into which he had fitted the 600 pages of his story in miniature script, were confiscated by the Soviet authorities as well. Back in (West) Germany, Gerlach sought to revive his memory, only to find it obscured by the ‘grey veil of the years spent in the camp’. In the autumn of 1950 he came across an article in Quick that presented hypnosis as a new method of awakening a patient's ‘unconscious memory’. A certain Dr Karl Schmitz in Munich was claiming ‘spectacular’ results with this therapy.Footnote 2 Gerlach contacted Schmitz and asked for his help. The doctor was interested in his case. The penniless Gerlach could not afford the trip to Munich, however. In a letter to Schmitz he wondered whether a magazine such as Quick might not be interested in sponsoring his journey, in return for the rights to report on it.Footnote 3

Quick covered the Munich experiment in a lavishly illustrated report with photographs of Gerlach, evidently in hypnosis, as he speaks to the doctor and his secretary, who is shown taking notes on a notepad. ‘The bridge of consciousness’, the reporter noted, ‘has again extended itself over the abyss of lost years’. Dr Schmitz was satisfied with the therapy: ‘Gerlach dictated in the form of amazingly colourful images. By the time he departed, two-thirds of his novel had been retrieved under dictation. He left with months’ worth of materials to work with.’Footnote 4 The full success of the hypnosis became apparent in 1957 when Gerlach published his Stalingrad novel. It was an instant bestseller. The novel was translated into at least eight languages and it is in print, in German as well as English, to this day. It is considered as one of the most authoritative personal accounts of the battle of Stalingrad.Footnote 5

Figure 1: ‘I know again what was there . . .’ The opening page of Gerlach's hypnosis story.

Quick, 26 August 1951.

From the first time I came across Gerlach's novel I was enticed by the story of its production, loss and retrieval, narrated by the author in a short preface. I wondered: couldn't the original have survived? Where might I be able to find it? And couldn't the repeated ruptures in Gerlach's story-telling be seen as symptomatic, in some ways, of the larger story of Stalingrad and its aftermath? I am interested in the battle of Stalingrad as a dramatic turning-point in the war, where German and Soviet wartime ideological regimes and the notions of self that they expounded clashed and became entangled. The clash involved, on the German side, a particularistic Nazi racial ethic with notable defensive tinges, which cast the conquering Aryan soldier as a defender of German culture against a subhuman ‘Judeo-Bolshevik’ menace. Countering it on the Soviet side was a historically optimistic ideology that was rooted in the Enlightenment and cherished the prospect of a limitless progression of human reason. The central hinge of this ideology was the human will. Once mobilized, and directed as mandated by history, Soviet activists believed, an individual will could achieve miracles. This ideology was universalistic; it extended to Soviet soldiers and the enemy forces alike. In accordance with their voluntaristic beliefs, Soviet political officers in the Red Army spurred their soldiers to unbelievable feats of courage on behalf of their nation and, indeed, world history, and they sought to convince German enemy soldiers that they were on the wrong side of the world historical track.

Gerlach's own story did not begin until well after the Germans surrendered to the Soviets in February 1943, and it will fill one of the later chapters in my larger project. But from this point on it weaves a thread through the remaining years of the war and beyond, extending into the fabric of the two post-war German states. Most histories of the battle of Stalingrad cover the soldiers’ subsequent fate in the form of an epilogue at most. My interest, however, is not in the military encounter per se, but in the wartime clash and entanglements of ideological regimes, and their shaping effects on the lives of those who fought their battles.Footnote 6 Gerlach's attempts to write and rewrite his life story between 1943 and 1957 can be studied as a palimpsest onto which conflicting ideologies of selfhood pervading wartime and post-war Europe – Nazi and Soviet, fascist and anti-fascist, communist and anti-communist – were subsequently inscribed, overwritten and erased.Footnote 7

With the defeat of the 6th Army, scores of Germans – the largest contingent of enemy forces to date – came into Soviet hands. Many of them, newly available protocols suggest, fell victim to the passionate hatred of their captors.Footnote 8 As for the survivors, the Soviets proceeded to ‘re-educate’ them, using their psychological register and the language of political enlightenment. As Mikhail Burtsev, Head of the Main Political Directorate of the Red Army (GLAVPURKKA), put it succinctly, the mission of Soviet political officers was to ‘help the deceived soldiers of the imperial armies to obtain the truth’.Footnote 9 Many German officers taken prisoner in Stalingrad were selected to become model citizens of a new Germany, and some of them later joined the political administration of the East German state. In Nazi Germany, and later in West Germany, these conversion scenarios were denounced and countered with a contrasting narrative of German captivity cast in terms of sacrifice and suffering.

‘Manuscripts don't burn’, a twentieth-century Russian writer famously pronounced. The branch of the Soviet security police (NKVD) that oversaw the network of camps housing enemy POWs – Germans, Romanians, Hungarians, Italians, Japanese and others – preserved extensive records testifying to their efforts to gauge the ‘moral-political state’ and ‘moods’ of the prison population, and to intervene and reshape these sentiments.Footnote 10 As part of their political re-education effort, the Soviet camp authorities exhorted enemy prisoners to write and reflect about themselves, whether in newspapers or pamphlets, poems or songs. They even sponsored the production of entire theatre plays and novels. It is among these cultural artefacts, which were produced by German POWs in Soviet captivity and later deposited in the archive of the Russian State Military archive (RGVA) in Moscow, that I found the original, typewritten manuscript of Gerlach's Stalingrad novel.Footnote 11

Gerlach's manuscript allows for fascinating insights into how his experience of the battle of Stalingrad took shape, and the role played in the creation of this personal account by distinctly Soviet values and practices pertaining to the self. The version he penned in the POW camp differs significantly from the published book on account of its pronounced self-reflective and repentant quality. This quality was due in great measure to Soviet re-educational designs. They prompted Gerlach's self-accusation as a Nazi soldier and lent his novel its unmistakable shape. Guilt and repentance, reflection and transformation, were core attributes of Stalinist autobiographical practice, before and during the war. For Gerlach, this practice compelled him to recognise German wartime crimes as well as his own personal complicity and guilt. After being released from the camp and arriving into West Germany, Gerlach sought to obscure the impact of Soviet education and the complicity of the German military forces in crimes in Russia. His published novel instead appeared to be a self-generated introspection about the tragedy of German soldiers caught up in the war between Hitler and Stalin. The significant efforts made by the Soviets to confront German soldiers with war crimes, and – even before the war ended – to shape a German conscience, are erased not only from Gerlach's own record, but also from much of the public record of German guilt and its development after Hitler.Footnote 12

I.

This exploration of Gerlach's wartime and post-war subjectivity begins with a comparison of the two versions of his Stalingrad story: the manuscript written in captivity and the published novel. When I first read these two texts side by side, I was struck by their similarities. They are virtually identical in chapter structure and plot line, down to individual episodes and the exact wording of very many sentences. The story, in both versions, begins on the eve of the Soviet counteroffensive of 19 November 1942. It is narrated from the point of view of Germans who find themselves encircled in Stalingrad, and it narrates the unfolding drama of the trapped 6th Army, as soldiers have to cope with progressively diminishing supplies of weapons, food and heating fuel, and are increasingly unable to defend themselves against the Soviet troops and the bitter cold.

In trenchant and increasingly gory detail, Gerlach describes the descent of a conquering army of soldiers, a quarter of a million strong, into a disorderly mob. The initial conviction on the part of many of the Germans that their setback is only temporary and that they will rebound against the inherently weaker Russians gives way to increasing doubt and, ultimately, feelings of panic and doom. Some cling until the very end to the belief that Hitler will bail them out, but most of the soldiers and officers feel increasingly abandoned and betrayed, and they denounce him as a criminal and callous tyrant. The test and demise of the Nazi world view (Weltanschauung) in Stalingrad is a central theme of the novel. While focusing on a select number of individuals and how they respond to the catastrophe unfolding around them, Gerlach's narrator also seeks to provide a general picture of the horrors of the battle and its effect on the army as a whole. Both versions include an author's note emphasising the story's factual authenticity: it is based on Gerlach's own personal experience in the encircled pocket at Stalingrad, and also on subsequent conversations with comrades in Soviet captivity. Gerlach explains that he gave fictional names only to the lesser characters, not however to the higher officers and political leaders, who appear under their actual names.Footnote 13

The novel's principal character is Senior Lieutenant Richard Breuer. As a divisional staff officer in charge of intelligence, he appears to be Heinrich Gerlach's alter ego in the novel.Footnote 14 He is the central character in other ways as well: intellectually and psychologically, Breuer occupies a middle ground, flanked as he is by individuals with more outspoken views on either side. To his political right are two ardent Nazis and anti-Bolsheviks, Lieutenant Dierck and Russian translator Froehlich, the latter a Baltic German who fled his homeland after the Soviet revolution. To Breuer's left are Lieutenant Wiese, a Christian believer and vocal critic of Nazi ideology from the very start, and driver Lakosch, an intellectually modest man with no aspirations towards a Weltanschauung of his own. Nevertheless, Lakosch grows increasingly receptive to communist positions in the course of the novel. Standing between them, Breuer comes across as a card-carrying Nazi with a bad conscience. He wants to believe as selflessly as Dierck in the ideals of national regeneration and comradeship upheld by the Nazis, but he cannot silence his ‘selfish’ longing to be reunited with his family, nor can he ignore the increasing feeling of exhaustion induced by the war. Breuer secretly admires Wiese, but publicly condemns him, for he feels that Wiese goes too far in questioning the entire pursuit of the war.Footnote 15

The tension between the characters comes to the fore early on after the capture of a Soviet pilot who makes a crash landing near the divisional staff quarters. Interrogated by Breuer, in the presence of Dierck, Fröhlich, Wiese and Lakosch, the pilot remains silent. Dierck suggests breaking his bones, but is lectured by Breuer that this is not an appropriate way for Germans to behave, as they ‘belong to a nation of culture . . . [We are] German soldiers, not mercenaries and vagrants’. Suddenly the pilot speaks out; he asks to be shot. Breuer reiterates his position: ‘We do not commit murder, we aren't criminals’. ‘Shoot me’, the pilot insists. His life is over, he explains. Either he will starve to death together with the encircled Germans or he will be killed by them in rage once they realise that they are hopelessly trapped. The startled Germans listen as the pilot proclaims a verdict over them and Nazi Germany as a whole, rendered in flawless, slightly accented German. Personally, he says, none of the Germans facing him may consider themselves to be criminals, but objectively all of them function as ‘henchmen’ of fascist aggression:

I know the Germans very well. They have raided our country, during peace time. They plunder and murder. They have murdered the Jews, and now they murder Soviet people. They hang them on gallows. Why . . .?’ Quizzically he looks at the Germans, but receives no answer. ‘I used to love Germany. I read Heine, Goethe, Hegel. Today I know that the Germans are criminals . . . But the peoples of the Soviet Union will take severe revenge on the German occupants. Our war is a just cause. Every man, every woman, the entire people is fighting in this Great Patriotic War. We are defending freedom, human rights, the achievements of the Great Socialist Revolution. And that is why we will win.

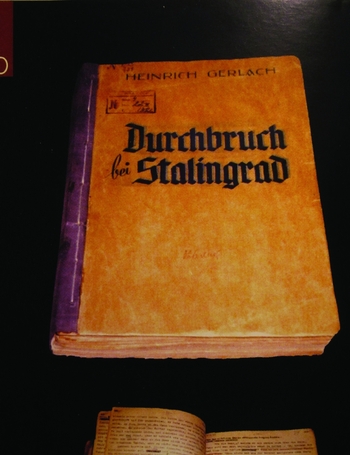

Figure 2: The cover of Gerlach's prison ms., ‘Breakthrough at Stalingrad’.

V. A. Vsevolodov, Lager’ UPVI NKVD N. 27 (kratkaia istoriia), ili: Srok khraneniia – postoianno (Krasnogorsk: Memorial'nyi Muzei Nemetskikh Antifashistov, 2003).

Figure 3: The cover of Gerlach's book, The Forsaken Army, published in 1957

Heinrich Gerlach, The Forsaken Army (London: Cassell, 2002)

After the prisoner is led away, a discussion erupts among the Germans: the Christian Wiese finds validity in the pilot's point about German aggression and the Soviet just cause. Dierck counters with a morality based purely on strength and the interests of the German people (Volk). Breuer is ‘impressed’ by the appearance of a political officer (among the pilot's personal documents they find a Communist Party card) who does not conform at all to the caricature of the Bolshevik commissar. Dierck calls him and Wiese to reason: ‘Gentlemen! I believe you are National Socialists as well?’ ‘Yes’, Breuer says with a ‘brittle voice’.Footnote 16 To the driver Lakosch, who silently witnessed the interrogation, the Soviet pilot's ode to his homeland comes as a revelation. What if the Soviet people are not the subhuman beasts portrayed by Goebbels? Perhaps the war is the result of a big misunderstanding between two peace-loving peoples? Impelled by further observations and events, Lakosch eventually crosses over to the Soviet side personally to broker a ceasefire between the warring armies.

While the action of novel is centred on the period of the Germans’ encirclement in Stalingrad between November 1942 and February 1943, repeated flashbacks to the principal characters’ lives before Stalingrad create a wider historical perspective on German society since the end of World War I. We learn that a militaristic old Prussian schoolteacher had indoctrinated young Breuer with the virtues of war, and that years ago Lakosch had a falling out with his father, a communist worker who condemned his son's enthusiasm for the ‘new era’. The father later perished in a concentration camp. Thus, each of the protagonists has a distinct sociological profile and is presented as an actor on a national and even world historical stage.

Gerlach's original manuscript, however, endows several of these characters with much more interiority than they have in the published novel. The reader of the manuscript shares in their inner stream of consciousness, a dimension that the book presents in sometimes heavily curtailed form, and more often not at all. The manuscript's chief concern is not the documentation of military events or the actions of the German soldiers per se; rather, it is with ‘Stalingrad’ as an ominous sign demanding to be deciphered, understood and internalised by soldiers participating in the battle as the only chance for them to remain alive. Crucially, the manuscript distinguishes between those who recognise the writing on the wall and turn in their tracks, and those who blindly march – later crawl – on. Whether or not a character engages with ‘Stalingrad’ decides whether he will be rescued or broken in the hell of the battle. Admittedly, even a character with a developed interiority, such as Wiese, dies in the pocket, but his moral example, coined in his last words to Breuer just before he dies, lives on in others and thus has redemptive meaning. In turn, many other characters stubbornly refuse to recognise Stalingrad as a watershed between old and new times.

Figure 4: A page from Gerlach's prison ms.

Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi voennyi arkhiv, Moscow.

Stalingrad's power as a life-changing force is muddled in Gerlach's published book account. Largely silenced, too, is the critical engagement with norms prevailing in the Wehrmacht, which takes up many pages of the camp manuscript. In laying out these problematic values, the manuscript calls for their re-evaluation. Consider Colonel Hermann, portrayed rather favourably as an upright soldier and officer. Hermann is disgusted by the opportunistic behaviour of other senior officers; until recently they had solemnly pledged to fight to the last bullet, but now many were trying to leave the pocket on evacuation flights reserved for the wounded, or they were thinking about surrendering to the Russians. Such behaviour contradicted Hermann's principles of soldierly honour and particularly the oath he had sworn to Hitler. Alone at night, however, Hermann was beset by doubts: ‘“Did one have to keep an oath sworn to a criminal? Weren't there ties that counted more, the family, the people – God?” . . . He felt with horror that he was losing the ground under his feet’. These questions, Hermann realised, had a revolutionary quality. But he also knew that a revolution was something only people from the gutter made. For him, coming from a family of officers, this was not an option. ‘It was the dawn of a new era’, Hermann sensed, ‘an era that he did not understand, with foreign ideals and values, an era of new men . . . The old world was vanishing, and he would perish together with it. He wanted to save his face, die as the last of the old order, as the last knight.’Footnote 17 Hermann, whose character is modelled on the real-life figure of General von Hartmann of the 71st Infantry Division,Footnote 18 meets his end in the final days of the battle of Stalingrad. Dressed in his best military garb, he emerges from the trenches, a rifle in hand, and begins to shoot at the Russian positions until he is felled by a shot in the forehead. Remarkably, Gerlach's published book lacks Colonel Hermann's inner monologue about the old and the new times. The staunchly anti-revolutionary colonel is represented as a moral exemplar. There is no suggestion that he may be historically outdated.Footnote 19

The differences between manuscript and book are most pronounced in the portrayal of the lead figure, Senior Lieutenant Breuer. Several other characters evolve psychologically and intellectually over the course of the novel as well, but it is Breuer who in the manuscript version undergoes the most pronounced inner transformation. The power of Stalingrad plays out with full force, redefining his life. Much of this power and the interiority that it produces is absent from the pages of the published novel. In the first days and weeks of the encirclement of the Germans, in late November and early December 1942, Breuer has no more than a dim awareness that something is deeply amiss with the Wehrmacht. He has ‘dark doubts and bitter questions’, but the hasty retreat gives him no time to think them through.Footnote 20 Only later, as Breuer is slowed down by the cold and by increasing hunger, does he begin to reflect. He increasingly recognises the drama unfolding around him in Stalingrad as a tragedy – as Germany's tragedy. The army's demise has an inexorable quality, and it is the price for Hitler's criminal policies that he, Breuer, and millions of other Germans have abetted.

Breuer arrives at this deeper insight not on his own, but largely thanks to his friend, Lieutenant Wiese. When Wiese is mortally wounded during an aerial attack, Breuer is at his side. The dying Wiese turns to him as his confessor. Guilt, a term that up to this point in the novel Breuer had only vaguely felt, is now spelled out.Footnote 21 A believing Christian who had never fired his weapon at the enemy, Wiese pleads guilty nevertheless because he has seen Germany's tragedy come but done nothing to prevent it.Footnote 22 After bidding farewell to his friend,

Breuer wandered over the icy main road over which still hung the sulfuric haze of the recent shelling. The road was covered with garbled bodies, scraps of flesh, torn limbs. The pools of blood were still fresh and red, and a light steam rose from them. Trucks hurried by like hunted animals. Breuer didn't see any of this. He was wrapped in the dialogue with his dying friend. Guilty! The word was burning inside him. ‘Yes, we are all guilty!’Footnote 23

Shortly after Wiese's death, Breuer is severely injured at the head. A piece of shrapnel enters his temple, he loses the sight in one eye. At a field hospital he is fortunate enough to receive an official evacuation order entitling him to be flown out of the pocket. But during the brutal storming of the last planes to leave Stalingrad, Breuer is pushed to the ground. The plane leaves without him. It is 23 January 1943, the day when the German airlift to the beleaguered city was discontinued. The following night Breuer realises with full clarity that he will not be able to leave Stalingrad. His personal fate is irrevocably tied up with Stalingrad as a whole. It is at this point that Breuer senses that his former self fades away and dies. He tries, but fails, to recall images from his past life:

His work study, the green chair and the floor lamp that he used when reading; the faces of his wife and children; the last trip on the steamship to the Nehrung sand dunes, only days before the beginning of the [military] ‘short term exercise’ that had never come to an end. He didn't succeed. It all remained pale and blurry. The old world was erased . . . He didn't understand: how was it possible that only a short time ago (was it two days ago? Yesterday?) he had been desperate . . . to fly out? Where was it that he had wanted to go? There was no more turning back . . . How had it happened? Had the old Breuer . . . really died? It almost seemed so. This well-behaved and willing Breuer, a caring bourgeois, really appeared to have died, along with everything that he had thought, believed in, loved, and hoped. What remained was a vessel without hope and pain, dull and infinitely empty.

Breuer feels that his entire past life, with its ideals and gratifications, is invalidated. The ‘awful unveiling at Stalingrad’ had put an end to Breuer as he used to be. Stalingrad symbolically bundled German criminality, hubris and guilt. ‘A harsh hand had wiped over the board and erased the colourful signs of a false happiness. All that remained was the wall – empty and black’.Footnote 24 A few days later, a doctor examines Breuer's blinded eye. He tears off the old bandage:

‘You were damn lucky’, the doctor said. ‘The eye hasn't discharged, but everything is sticky and crusted . . . Turn your head towards the light. Can you see something?’ ‘Yes, I see something’, Breuer said quietly, ‘a very weak glimmer. I think – yes, it is getting brighter’.

It is hard not to read the scene as a metaphor of Breuer's growing vision, following his debilitating knockout in the ruined city of Stalingrad, which in turn was a shorthand of the ruin of Nazi Germany.Footnote 25

It is in this context that the novel discusses Colonel Hermann's decision to fight to the last bullet and go down as Germany's last knight. After a paragraph break the perspective shifts to the staff officers cowering in a Stalingrad basement. Their mood oscillates between ‘insane hope’ (that Hitler will get them out) and ‘gloomy despair’. ‘Only Breuer experienced a great sense of calm. Everything was becoming increasingly light and clear to him’. Breuer's thoughts go back to his friends Wiese and Lakosch whose thoughts (Wiese) and actions (Lakosch) had helped him arrive at his new, unfolding insight:

Wiese, whose words he began to understand fully only now, had discerned the German tragedy . . . as clearly as anyone; but he had lacked the power to convert his knowledge into action. That had broken him. And Lakosch? Most likely the small private had only dimly sensed what this was about. Still, he had found the courage to act, on his own, against all law and all habits . . . New signs were on the dark wall. The script was becoming ever more legible.Footnote 26

Breuer's conversion, initiated with the death of his old self, is progressing steadily further. Not only does he possess a higher insight into what is going on; he also finds the strength to act, by speaking out. He does this in a Stalingrad basement in late January 1943, where scores of famished and wounded Germans await their fate. Some shoot themselves. Translator Froehlich, seized by fear of falling into Russian captivity, darts out of the basement, only to die in a rain of Soviet bullets. Most others prepare for captivity. As they do so, there is grumbling about the higher officers who are nowhere to be seen, having evidently betrayed the values of the good German soldier. Breuer barges into the discussion. We German soldiers, he maintains, have long forgotten about the meaning of these historic values – fidelity, duty and honour. ‘We are no soldiers! We have acted as mercenaries – stupid, paid mercenaries, for much too long already – ten years! It is time that we come around, high time!’ Breuer has come full circle, contradicting what he declared to the captured Soviet pilot in the initial part of the novel. An officer in the room reprimands Breuer for besmirching the German Wehrmacht:

‘I do not want to insult you’ [Breuer] calmly replies, ‘but should we survive Stalingrad and not have learned anything decisive from this, we wouldn't have a right to live . . . This is not a question of individuals, it is about the system, the very Wehrmacht that you were just talking about . . . Stalingrad had to happen in order to open our eyes . . . It is of no help to desperately cling to the old ways. You can't support a falling structure.’

His words are underscored by a powerful detonation that rocks the basement, interrupting the discussion.Footnote 27

Breuer's insight is shared by a few others, notably Captain Eichert, who speaks in one of the final scenes of the manuscript. By now, Soviet troops are guarding the entrance, and Eichert, standing on a chair in the crowded basement, seeks to prepare his comrades for the captivity awaiting them. ‘We are done with,’ he says.

We didn't want this. But we were blind in our obedience. We are not free of guilt . . . Now we want . . . to walk the last difficult path together as well. We don't know what the future holds for us. But whatever it will be, we will accept it as atonement . . . We used to be soldiers of the Führer. From now on we will be human beings. Break step!

Eichert's speech in the published book is markedly different. There, he absolves the soldiers of guilt: ‘That the uniform we wear is no longer an honourable one is not our fault’.Footnote 28

Both versions of the novel concur that Hitler is the principal evil spirit behind the tragedy of Stalingrad, and both conclude with a verdict on him:

In the spring of 1943 the Commander-in-Chief of the disbanded Army Group B . . . and his Chief of Staff were paying a farewell visit to the Führer's headquarters. At that moment the first letters from the Stalingrad prisoners of war had reached Germany. That was a sign, the two gentlemen remarked during lunch, that many of the Stalingrad soldiers were still alive, and they talked about the relief this would mean for their relatives. Hitler looked up with a glance that made the two officers fall silent. And he replied: ‘The duty of the men of Stalingrad is to be dead’.Footnote 29

In the published book version Hitler's reply confirms the victim status of the German soldiers in Stalingrad. Wanting them to go down as tragic heroes, he callously sacrificed an entire army. All along the book favours a clear ethical distinction between Hitler (along with top commanders such as the Commander of the 6th Army, Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, who anxiously or blindly followed his ordersFootnote 30) and his army of overall good, but deceived soldiers. The original manuscript speaks a more complex language. It portrays the soldiers as both victims of Hitler's designs and active perpetrators of a Nazi war of conquest and annihilation. Precisely because they bear responsibility for their actions and are deemed guilty they need to live on in order to repay their guilt – through the work of their conscience, and through active deeds. Most succinctly the divergence between the two versions is expressed in their respective titles. Gerlach's book was published as The Betrayed Army and is known under this title to this day. Originally the manuscript was entitled ‘Breakthrough at Stalingrad’, a title that aptly conveys Breuer's intellectual and psychological progression, indeed, his conversion experience in Stalingrad.

II.

Why the published book poses the guilt question in the way it does may not be surprising in the light of what we know about West German politics of memory in the 1950s. The concluding part of this essay will revisit this issue. More intriguing is the question of how to account for the marked conversion structure of the original manuscript that was later toned down or even erased from the published version. Which circumstances prompted Gerlach to write the account in the first place, and how may his writing of it have been shaped by his experience in the Soviet camps? Finally, how can we make sense of the narrative's strong introspective quality and the striking presence of individual guilt articulated in it?

Many details about the years Gerlach spent in the Soviet camps we know from him personally. They are presented in a sequel to his acclaimed Stalingrad memoir, which he published in 1966. Entitled Odyssey in Red, and composed in the same documentary style, the book spans the period from the German surrender in Stalingrad on 31 January 1943 to Lieutenant Breuer's liberation from the camp and repatriation to Germany in early 1950.Footnote 31 In some respects the documentary value of the book seems unreliable, especially when it comes to the Soviet camp authorities, whose shaping presence in the process of his coming to terms with the Hitler regime Gerlach (Breuer) consistently downplays or denies. (Gerlach may not have had much of a choice, for to acknowledge to a West German reading public in the mid-1960s the productive effects of Soviet re-education designs would have invited highly damaging charges of communist propaganda and treason.) Yet if placed alongside documents produced in Soviet POW camps in the 1940s – written by German POWs themselves or for their benefit – Red Odyssey and Gerlach's original Stalingrad manuscript make for a different picture: one of energetic and directed thought reform, of ‘re-educating’ ‘fascist’ soldiers into committed ‘anti-fascist’ citizens. Probably it was these Soviet policies that prompted Gerlach to write his account and that shaped the manuscript's narrative form.

Within weeks of the Germans’ rout at Stalingrad, Breuer is brought to Moscow's Burtyrka prison and questioned by the NKVD. The interrogators, who have a special interest in the captured German intelligence officer, trigger his memory. Conversing with him in German, they ask him to write down everything he has done in the Soviet Union. Breuer begins to take notes, starting with the first days of the war in September 1939, when he took part in the invasion of Poland, serving as a corporal. For pages he dwells on his memories of Warsaw, the hotel Europeski, cabaret shows with naked dancers, and the warehouse full of furs that a fellow soldier had confiscated from Jews evicted to the Ghetto:

The first SS officers, in the new grey uniforms, with inner fur lining, soft leather boots, riding crop. They were buying goods on the black market where pale Jewish girls were selling stockings. ‘You want me to pay, you dirty pig?’ ‘Please, dear Herr!’ Slap, slap. A picture of misery in the snow. Silent cries. Gloomy silence everywhere, glances . . . ‘Did you say something, corporal?’ ‘No, Herr Hauptsturmführer!’ The clicking of heels, a salute. The gentlemen walked away, laughing. This was only a rehearsal. Did you say something, corporal? Didn't say anything, didn't do anything . . . Footnote 32

The NKVD interrogators are impatient. ‘Write down what you have done in the Soviet Union!’ Breuer's memory shifts to the events following June 1941:

The pen scratched over the sheet of paper. ‘In the morning hours of 22 June 1941 the division crossed . . . the Bug river . . .’ . . . Look, the eye is functioning again! You only need to tilt your head to the left and turn the neck a bit. The muscle . . . has grown together again, autonomously and not requiring any medical assistance.

Gerlach's renewed reference to his eye wound, with its metaphorical implication, is noteworthy here, for while he insists that his new and better understanding of the atrocities in the East unfolds freely and without any professional assistance, it is also clear that it was the NKVD that instructed him to put pen to paper in the first place and reflect on the 6th Army's trail of blood. Breuer's reflections take him further, he recalls images of the first prisoners his division took in the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. He vividly remembers the hatred in the eyes of captors and their captives alike:

This wasn't Poland, France or Yugoslavia, where imprisonment put an end to the war. ‘Hello, comrade! Cigarette?’ . . . No, here nothing was over . . . So these were the Bolsheviks, subhumans. Two worlds stared at each other and realised: the war was on – a war about being or non-being.

Breuer also records the shooting of a commissar by unspecified members of his division, and he traces the division's further advance past Berdichev and Belaia Tserkov’, without dwelling on the atrocities committed by units of the 6th Army among the Jewish population.Footnote 33

Breuer was interrogated at such length because of his role as an intelligence officer in the Wehrmacht. Yet Red Army political officers often made a point of interrogating every individual Wehrmacht soldier who fell into their hands. Captured enemy soldiers were repeatedly interrogated, first on the battalion, and later on the regimental, divisional and army levels. The interrogation on the army level, performed by political officers, was the most comprehensive one. It built on a questionnaire of about 140 questions that sought, among other things, information on the prisoner's political convictions, his view of fascist Germany and of the Soviet communist state.Footnote 34 After his transfer to a POW camp, the prisoner was interrogated again, on the basis of yet another questionnaire that featured even more questions on the soldier's biography and his personal views. Clearly, these interrogations were meant to stimulate reflection and rethinking of ingrained views and values. Breuer's case is highly suggestive that the Soviet interrogation was effective in triggering a critical consciousness on his part, even though Gerlach, as Breuer's alter ego, did not fully acknowledge this link.

From the Butyrka prison, Breuer is brought to Krasnogorsk, a POW camp near Moscow reserved for senior enemy officers. It was at Krasnogorsk that the Soviet camp administration set up a ‘Central Anti-fascist School’ in spring 1943, the stated purpose of which was to ‘prepare from among the POWs steadfast anti-fascist cadres, who will not only in words, but also in deeds carry out work to the detriment of the Hitlerite clique and its vassals.’Footnote 35 Breuer remains in Krasnogorsk only briefly, before being transferred to the Suzdal’ camp in the late summer of 1943, and he makes no mention of any involvement in the anti-fascist school. He does, however, discuss his involvement in another institution that originated in Krasnogorsk: the National Committee ‘Free Germany’(Nationalkomitee ‘Freies Deutschland’, NKFD), which was founded in July 1943. German communist émigrés had been the first to suggest the creation of an institution that would speak to Germans not through the largely ineffectual prism of class but by appealing to their national sentiment and having the inclusive thrust of a popular front. German POWs were to turn against Hitler in the name of a new and better Germany, spearheaded by the National Committee.Footnote 36 In Suzdal’, Breuer comes across the founding issue of Free Germany, the organisation's newspaper, and reads:

Germany must not die! It is now a matter of life or death for our fatherland . . . If the German people continue to let themselves be driven into doom, without exercising their will and without resistance, they will not only grow increasingly weak with every day of the war, they will also assume more and more guilt . . . But if the German people become manly in time and show through deeds that they want to be a free people . . . they will conquer the right to determine their own future fate . . . This is the only way towards the salvation of the freedom and honour of the German nation.Footnote 37

Breuer likes the manifesto, it appears to be an ‘honest’ German initiative: ‘Here something arose from a deep foundation, from a commonality of language, culture and history. Here arose from the blood sacrifice at the Volga, in a time of utmost need, salvation for a people’.Footnote 38 Breuer is not alone in thinking like this; the National Committee appealed to many German survivors of Stalingrad, precisely because it lent meaning to their experience. Until then, Stalingrad connoted merely feelings of crisis and betrayal.Footnote 39 Hitler had not bailed the troops out; moreover, during the very final days of the battle, Breuer and others had been furious to hear Marshal Goering on the radio publicly celebrating their heroic end.Footnote 40 The NKFD initiative now lent a future perspective and meaning to a traumatic past. It refigured the ‘blood sacrifice’ at the Volga into the birth mark of a new and better Germany. While the story appealed to Breuer as a patriotic German initiative, its conversion narrative, and many other parts, were provided by German and Soviet communists working largely behind the scenes.Footnote 41

Within a few weeks of the founding of the NKFD, Breuer/Gerlach joined the team of six editors of Free Germany, the weekly newspaper issued by the Committee.Footnote 42 In issue after issue, the paper appealed to German officers and soldiers to break with Hitler and devote themselves to a better, renewed Germany.Footnote 43 The paper also featured articles submitted by National Committee representatives at the front whose task it was to analyse the enemy's moods and political morale, and to convert captured enemy soldiers to the anti-fascist cause. Some of these reports resonated with disbelief and outrage at what the captured Germans were saying or what they had been writing in their letters or diaries. In several cases, long diary passages were published in the paper as documentary proof. In the autumn of 1943 Lieutenant Heinrich Graf von Einsiedel, a former Luftwaffe officer shot down over Stalingrad,Footnote 44 sent in a report from the just liberated Melitopol’ region in south-eastern Ukraine. He was shocked at the devastation caused by German scorched earth practices, at the mass murder of the local population committed by the retreating troops, and at the fact that these atrocities were recorded in the German soldiers’ own letters. All of this brought home to him the utter ‘brutishness of the Hitler system’. ‘How can all of this’, Einsiedel wondered, ‘as well as the execution of 1 to 1 ½ million civilians be carried out solely by special commandos?’ Unless German officers and soldiers broke with Hitler, quickly and decisively, justice would run its course, for ‘world history is the world's judgment court!’Footnote 45

With its bow to Schiller and Hegel, Einsiedel's concluding sentence had a distinctive Soviet ring (Soviet predictions that fascism was due to appear in the ‘world's court of judgment’ were ubiquitous during the war); moreover, the investigative method and conclusions at which Einsiedel and other front-line representatives of the National Committee arrived were strikingly similar to wartime Soviet analyses of German soldiers. From the very start of the war, Ilya Ehrenburg, a towering commentator on the Soviet war effort who published columns nearly every single day of the war, had mined German personal documents, which he derisively called the ‘diaries of Fritzes and letters of Gretchens’, for insights about the enemy's character and fighting mood. One reason why Ehrenburg was so drawn to these documents was his belief that letters and diaries should elevate a person, turn him or her into a reflecting and morally self-aware human being. The Germans, or at least the German diaries he focused on, showed the very opposite. They used the instruments of culture, pen and paper, to record orgies of destruction. Instead of reflecting on their human essence, they gave in to their basest impulses. ‘Potatoes and pigs’ were their ‘sacred ideals’.Footnote 46 Against this foil, Ehrenburg extolled the moral superiority of Red Army men and other Soviet war participants, as revealed in their letters and diaries, from which he quoted at length.Footnote 47

A similar documentary method – reading German letters and diaries and interviewing captured Wehrmacht soldiers – was used by Theodor Plivier, a German émigré who had lived in Russia since the 1930s and began to write a novel devoted to the demise of the 6th Army in the autumn of 1943. Plivier's initiative inspired Gerlach to write his own Stalingrad novel. As Gerlach relates in his memoir, it was in early November 1943, when he and the other editors of Free Germany were preparing an issue devoted to the anniversary of the encirclement of the 6th Army. One of the proposed contributions, by Plivier, captivated Breuer. Entitled, ‘On the Road to Pitomnik’, it was a horrifying account of the failed evacuation of wounded German soldiers from field hospitals to the Pitomnik airstrip in the night of 13 January 1943. Breuer was impressed by Plivier's artistic grasp and the insight his piece demonstrated. His thoughts turned to his own experience of the battle:

Stalingrad is the turning-point for Germany. Nothing of it must be forgotten. His diary, in which he had chronicled even the most minute experiences during the days of the battle – he had burned it in Dubinskii on 11 January 1943. Would he be able to reconstruct it from memory? His memories were still fresh. He had to give it a try.Footnote 48

On 19 November 1943, the anniversary of the Soviet counteroffensive, Breuer sat down to begin his own Stalingrad novel.Footnote 49

There was yet another inspiration for Gerlach to write his memoir. During the editorial meeting of November 1943 in which Breuer learned of Plivier's article, he noticed a TASS report about the Moscow Conference of the three Allied Powers. It was posted right above Plivier's article, on page 4 of the issue that was being prepared for publication, and announced that the Allies had passed a

declaration about the responsibility of the Hitlerite fascists for their atrocities. Germans who have taken part in mass executions or the extermination of the population living in the Soviet Union . . . shall know herewith that they will be sent back to the sites of their crimes . . . The three Allied Powers will undertake every effort to find the culprits, even if they should hide at the end of the world, and they will hand them over to their accusers, so that justice may run its course.

As he read the report, Breuer ‘felt a lump in his throat. He thought of things of which he had heard, things he had seen with his own eyes. Isolated cases’.Footnote 50 Breuer's feeling of guilt had first arisen during the interrogations by the NKVD; it reappeared, and in stronger form, now that the Soviet state moved from indicting the ruling ‘clique of Hitlerites’ to a juridical stance that targeted every individual war criminal. The soul-searching, self-accusatory tone of the manuscript that Gerlach began to write in November 1943 may have been partly an effect of the pangs of conscience he felt reading the report from TASS.Footnote 51

Within weeks, more reports came in from National Committee representatives stationed at the Southern Front. Lieutenant Bernd von Kügelgen wrote from Kiev. During his stay in the newly liberated city, Kügelgen reported, he had ‘learned two new Russian words: umirat’ [to die] and rasstreliat’ [to shoot] . . . In all my conversations with the civilian populations these words are said. There is no family that is not grieving for a relative shot by the occupation forces’. Kügelgen also introduced his readers to the killing grounds of Babi Yar where German POWs were now exhuming the remains of the Jewish victims:

The German soldiers are digging. They are front soldiers, no strangers to the horrors of war. Yet this experience goes beyond the horrors that they have witnessed so far. They remain silent. They still lack the words to express what is moving them. Only every so often they protest, indict Hitler and his murderous troops. But they feel that a mere ‘It was not me’, a mere ‘Down with Hitler!’ will not be enough. This crime demands a clear statement, it calls on every one of them to join the vengeful war. For we are all guilty. The fact that Hitler rules, that he leads this murderous regime – this is a matter of the German people. And it must be for us to deliver these criminals to where a just punishment awaits them. This guilt can be overcome only through deeds.

Kügelgen went on to describe how the grisly discovery in Babi Yar was integrated into political enlightenment efforts on the part of Soviet camp administrators:

Every evening short meetings were held in the camp, after the work commandos had returned and cleansed themselves with disinfectants. Without being called upon, soldiers who had fought the Red Army only a few days ago stepped forth as discussants. They broke with Hitler, broke with the fascist ideology of murder, and joined the side of the antifascists, the side of the National Committee ‘Free Germany’.Footnote 52

What the German POWs were doing at Babi Yar was exactly what their Soviet captors had prescribed for them to do. In order to ‘re-educate’ ‘fascist soldiers’ into committed ‘anti-fascist’ citizens, Soviet authorities devised a host of institutions and practices, ranging from impromptu meetings and study circles to formal lectures and seminars held in ‘anti-fascist schools’, to newspapers, wall newspapers and cultural programmes offered in the camps. All of these institutions and activities had in common that they sought to foster an understanding on the part of the German captives of what Hitler and fascism ‘really’ meant, so that they would distance themselves from the Nazi regime out of true understanding and conviction. As a result they would become individuals endowed with a moral compass and a political will, people who ‘profoundly realise the political and moral obligation of the entire German people, who are filled with a firm resolution to fulfil this national duty . . . who will consciously work in order to compensate for the damage’.Footnote 53

Soviet re-educators emphasised the importance of not simply lecturing the Germans. It was important to get them to use their own voice to denounce Hitler and their own involvement in the Nazi system, to have them reflect publicly and in writing on their conversion from fascism to anti-fascism.Footnote 54 A recurrent problem with the Soviet re-education campaigns, internal reports generated by the camp authorities indicated, was that the political teaching often operated on a very abstract level and failed to engage POWs.Footnote 55 This could not be said of the meetings conducted at the killing grounds of Babi Yar. They spoke to a crime that was as chilling as it was concrete, and they prompted individual reactions that felt real enough. These sentiments were evidently shared by Gerlach, who cites Kügelgen's report at length in his memoirs and writes that Breuer was shocked to realise the ‘systematic’ criminality of the Nazi regime.

Throughout his memoir, Gerlach insists on Breuer's sole authorship in the making of this manuscript, and he is careful to insulate this project from the world of Soviet propaganda in the camps, which appears as enforced and inauthentic. ‘Breuer sought to escape from his depression by devoting himself to his Stalingrad project’, he writes. Unable to reconstruct his diary notes, he chose the format of a documentary novel. The communist Alfred Kurella helped with advice and supplied Breuer with paper. As an editor of Free Germany, Breuer had access to a typewriter, which he used during the evenings and at night to work on the text.Footnote 56 In the 1957 foreword to the published book, Gerlach claims that he wrote the manuscript secretly and did not show it to anyone, hiding the stack of paper beneath his pillow in the camp barracks.Footnote 57 How he was able to produce a 614-page manuscript without attracting notice in a camp environment swarming with guards and informers is difficult to imagine. In his memoir published in 1966, Gerlach allows for some qualifications. In fact, he writes, he had to part with the manuscript repeatedly, for it incited the interest of a German political instructor as well as a Soviet political commissar. Both times, Gerlach writes, his notes were later returned to him without any commentary.Footnote 58 That the camp authorities would not comment on the memoir seems unlikely, considering their enormous dedication to ‘enlightening’ the enemy POWs, and given their particular interest in confessional first-person narratives. Breuer's past as a German intelligence officer must have provided an extra incentive for his Soviet guards to read and analyse the Stalingrad novel.

How much at least some of Gerlach's writings in the camp were micromanaged by Soviet authorities transpires from a frankly worded secret report prepared by the Soviet Main Administration for Prisoners of War and Interns (GUPVI), which spelled out how the work of the newspaper Free Germany was actually carried out. In fact, the paper had two editorial bureaus. Soviet authorities secretly referred to the bureau staffed by Gerlach and the other POWs as the ‘backup’ bureau (redaktsiia-dublёr). The strings were being pulled from ‘Institute No. 99’ in Moscow, a secret institution controlled by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Comintern officials. On Mondays the main editorial office in Moscow decided on the theme for the next issue. The following day, a representative of ‘Institute No. 99’ consulted with the German editorial board. As the report pointed out,

the themes and arguments (contained in these articles) were never suggested to the backup bureau in the form of an order. The task of the representative from the main editorial office was to convince the members of the backup office about the correctness of the plan for the next issue. He had to create the impression that the plan was in fact their own . . . This was often a difficult task. The editors of the backup bureau appeared at the meetings with their own suggestions.

On Wednesdays and Thursdays the version prepared by the POW editorial board arrived in Moscow where, as a rule, 50–75% of the contents had to be edited. ‘Nevertheless, not a single formulation was changed against the author's will. In the end it was always possible to convince the author about the necessity of the editorial changes’.Footnote 59 It is tempting to consider a similar division of labour for Gerlach's novel project. Did Gerlach (have to) discuss his progress on the novel with Kurella and other communist officials? Who made the blue and red pencil marks on the margins of the manuscript?

In a short article (‘The New Road’) published in Free Germany in February 1945, part of a larger commemoration of the second anniversary of the defeat of the 6th Army, Gerlach took up central images and themes from his novel: in February 1943, when he and other German soldiers had surrendered themselves into Soviet captivity, ‘before us was an uncertain future that looked dreadful, like a menacing dark wall: captivity, “Bolshevism”!’ Against these fears he had chosen not to kill himself, for that would have been a last service rendered to Hitler. The decision to live on was a small, but significant first deed against Hitler. ‘We marched through the darkness. It became light. We saw the socialist people's state of the Soviet Union. We saw happy, free people.’ In February 1945, many people in Germany were enveloped by the same darkness that the German soldiers in Stalingrad had experienced two years ago. They were clinging to Goebbels's racialised propaganda of Asiatic Bolshevik hordes, unable to see the light that would lead them onto ‘the new road’.Footnote 60

Gerlach evidently sought to share with the readers of the paper issues that he was working through in his novel. The description of the defeat in Stalingrad as a black wall, blank and menacing at first, but gradually revealing an inscription, echoes the central image with which the novel concludes. While the novel ends in February 1943, with a view on the future that remains shrouded in uncertainty, Gerlach's article provided a more legible image of this (by now, nearer) future: it heralded the birth of a new, anti-fascist Germany cured of its anti-Bolshevik obsession. This article, in the context of the other institutions and practices discussed above, puts Gerlach's novel much more closely in dialogue with the language and the mechanisms of Soviet political enlightenment than Gerlach would ever acknowledge in his memoirs.

Lieutenant Breuer, who had begun work on his novel on 19 November 1943, finished writing it on another symbolically charged day: 8 May 1945. These framing dates were meant to underscore how much his Stalingrad novel was to be read as a parable of the demise of Nazi Germany as a whole. But in his memoirs Gerlach also sought to make clear that his novel was completed in immediate proximity to the events in Stalingrad, during the war, and not in the post-war period, which he characterised as a time of growing Soviet political and ideological pressures among the POWs. The novel, he implied, was free from these Soviet propagandistic influences. There is, however, at least one indication that Gerlach's manuscript was not completed until 1947.Footnote 61 That year, in order to boost the production of politically and morally valuable cultural activities among German POWs, the Soviet camp administration launched a public competition for the best anti-fascist play. The enthusiastic response from among the German POWs may have been because the main prize to be awarded to the author of the best play was immediate repatriation to Germany. A total of 632 submissions came in from camps all over the Soviet Union, many plays among them, but also poems and novels. Gerlach appears to have sent in his novel as well. The jury confirmed the presence of an ‘anti-fascist spirit’ in 425 of these works, and it awarded seven prizes. No one won first prize, however – a distinction reserved for a submission considered outstanding on both literary and political grounds.Footnote 62

Gerlach's piece did not win the jury over, but politically more dispassionate eyes recognise how strongly it was shaped in form and interpretation by Soviet wartime political enlightenment campaigns. The journey from darkness to light, the metaphor of a vision impaired and restored, and the seminal figure of death (of the fascist soldier and the bourgeois subject) and rebirth (as a morally purer, historically aware, and politically active citizen) all echo conceptions of selfhood that characterised the Soviet realm as a whole and came to be applied to enemy POWs as well in the course of the war. A political instructor in the Suzdal’ camp cited in Gerlach's memoir informs Breuer of the esssence of Soviet re-education: ‘The purpose here is to get people to deal critically with their past. To make them understand why they are here. To make them think differently and learn new ways.’Footnote 63 Gerlach's autobiographical novel, ‘Breakthrough at Stalingrad’, perfectly responded to all these points. This is not to suggest that Gerlach merely succumbed to a propagandistic language that was pervasive in the camp, or that he wrote the novel in a utilitarian vein. Arguably, Gerlach assimilated the Soviet notions of introspection, guilt and conversion so readily because they spoke powerfully to German survivors of Stalingrad who were no longer willing to identify with the Nazi call for a self-sacrifice in battle, and yearned for a larger purpose to rationalise and justify the experience of a battle, which in the accounts of Gerlach, Plivier and many other eyewitnesses was so overwhelming and grotesque that it appeared to defy human comprehension.

Gerlach's Stalingrad manuscript is remarkable for the voice it gives to the protagonist's unfolding conscience (a dimension glossed over or erased in the novel's published version). In this respect, his work even stands out in the context of other works produced by German POWs in Soviet captivity.Footnote 64 Gerlach's sense of personal responsibility, and indeed guilt for German crimes at the eastern front was brought to the fore by Soviet interrogations and political enlightenment campaigns. Yet the guilt professed by Gerlach's novelistic alter ego Breuer – recall the lump forming in his throat in reaction to his reading about the Moscow Conference – also raises troubling questions. Could it refer to crimes that Breuer/Gerlach had been involved in, but did not own up to during his interrogations, or in his memoirs? Was this a reason why Gerlach burned his war diary on 11 January 1943, when it was becoming clear that the German army was fatally trapped? Or could it be the other way around – that the very notion of guilt, which Gerlach/Breuer articulated as an expiatory gesture, brought his Soviet listeners and readers to suspect a personal criminal responsibility? Either way, by 1949, when the bulk of POWs had been repatriated to Germany, Gerlach was not among them. He was instead being investigated for possible war crimes. In his memoir Gerlach calls the charges invented and portrays them as a purely political move to turn him into a willing Soviet spy after his eventual release to Germany. Gerlach was allowed to return to Germany after agreeing to collaborate with the Soviet security police. His memoir ends with his repatriation to East Germany in April 1950 and his escape from there to West Berlin.Footnote 65

From West Germany Gerlach appears to have appealed to Soviet officials for a release of the Stalingrad manuscript that was withheld from him when he left the Soviet Union. It would seem, from sketchy, yet eminently suggestive archival traces, that Gerlach's appeal landed on the desk of Deputy Minister for Interior Affairs (MVD) Ivan Serov. Serov in turn notified the Politburo that Gerlach's novel ‘was written in an anti-fascist spirit. The author, who has escaped to West Germany, wants the manuscript returned to him for the only reason that he fears that it is a document that may compromise him in the eyes of the Anglo-Americans’. On 9 December 1950 the Politburo directed Mikhail Suslov, the Central Committee secretary in charge of ideology and propaganda, to review the manuscript. In their three-page joint review, dated 28 December 1950, Mikhail Suslov and Vagan Grigour'ian, Chair of the Foreign Political commission of the Central Commission, wrote that in spite of Gerlach's claim to have written a truthful account of events, ‘a quick perusal of the novel immediately shows that the book is not only very far from a truthful depiction of the battle of Stalingrad, but that it is mendacious to the core’.

They took issue with Gerlach's decision to restrict his account of the battle to ‘one side only’, that is, to the fate of the German army. They also objected to the fact that Gerlach appeared to show more interest in the biographies of officers than those of ordinary soldiers. The most damning charge, however, was that Gerlach looked at the war ‘not from the position of a progressive anti-fascist writer, but from the position of a rotten bourgeois intellectual, who sympathises with fascist ideology’. The reviewers saw evidence of this in Gerlach's choice of multiple protagonists, some of whom espouse openly fascist views. Sticking to a rigorously literal reading of the text, and not making any allowances for narratological liberties of any kind, the two Soviet reviewers excerpted at great length the positions of some of the unreformed Nazi characters in the book, claiming that they in fact expressed Gerlach's own beliefs. ‘From a literary standpoint’, the reviewers noted, the ‘novel has no value whatsoever. It is one-sided and gives a falsified depiction of the battle of Stalingrad . . . The language of the novel is poor . . . A book like this would currently play into the hands of the American-Anglo warmongers for the purposes of kindling revanchist tendencies in West Germany.’ Gerlach's request that his manuscript be returned to him remained unheeded.Footnote 66

III.

Gerlach settled in West Germany during a period of acrimonious scoresettling among former POWs in Soviet captivity. The first half of the 1950s saw in excess of a hundred so-called Kameradenschinder trials, trials of individuals who had served as ‘anti-fascist’ activists in the camps and denounced fellow soldiers to the Soviet authorities or even performed acts of torture on them.Footnote 67 Public resentment targeted not only these individuals on trial but any German who had sympathised with the Soviets during his internment and failed vocally to refute his past ‘errors’. Heinrich von Einsiedel, the fighter pilot and great-grandson of Bismarck who rose to deputy head of the National Committee ‘Free Germany’, demonstrated what was needed to restore one's civic credentials in the new West German state. After becoming disenchanted with the Soviet regime (or so he claimed) and leaving East Berlin for West Germany in 1948, he publicised the record of his intermittent Soviet ‘temptation’.Footnote 68

West German public opinion discerned only a handful of Germans as perpetrators of war crimes. ‘The overwhelming majority were victims, and no one was both: guilt and innocence were mutually exclusive categories’.Footnote 69 Stories of German suffering in Soviet camps, mass-produced by returnees from Russia, eclipsed public interest in the possible suffering Germans had caused others.Footnote 70 They could also fuel a ‘redemptive transformation’ that would effectively erase the consequences of German violence.Footnote 71

The two Christian churches had reasons of their own to promote stories of suffering in eastern camps. They held exceptional value for the purposes of ‘rechristianising’ post-war society.Footnote 72 Gerlach's autobiography, in the form he had penned it in Soviet captivity, did not fit any of these prescriptions. Against what was expected of a former Soviet POW, all the more so someone who had served on the National Committee, his complex narrative of victimisation and self-accusation; of feelings of betrayal and responsibility; of Soviet collaboration and German patriotism, hardly stood a chance of being understood, let alone being publicly embraced. To publish such an account in West Germany in the 1950s was to invite suspicion or, indeed, charges of treason.Footnote 73 Perhaps a medical intervention, such as hypnosis, could work to retrieve a primary script, freed from its Soviet imprint?Footnote 74

Figure 5: ‘Exhausted, Gerlach is letting his head rest on the pillow. Twenty hypnosis sessions have taken their toll. A stream of images and memories has awoken in him. In a matter of hours he relives, in compressed fashion, what he lived and suffered through over years. The curtain has risen over these concealed years’. Note not only the reference to suffering in the caption, but also the likeness to Jesus on the cross created by the photographic close-up of Gerlach, with his eyes closed and lips parted.

Quick, 26 August 1951.

There was an aftermath to Gerlach's hypnosis therapy conducted in Dr Schmitz's Munich practice. In 1957, the grateful author sent a signed copy of his bestselling novel to the doctor. Schmitz immediately wrote back. He reminded Gerlach of a contract they had signed in his practice in 1951. It stipulated that Gerlach would give Dr Schmitz 20% of the royalties, should his novel prove a commercial success. In his letter to Gerlach, Schmitz pointed out how successful his therapy had been: a ‘good two-thirds’ of the lost manuscript had been retrieved under its influence. He also reminded Gerlach that in 1951 he had treated the penniless returnee completely free of charge. This was the only reason for him to include the profit-sharing clause. Schmitz threatened to take the case to court. The altercation made headlines as far as in the American press.

In his response to Schmitz, Gerlach belittled the effects of the therapy: only about a quarter of the overall manuscript had been restored by it. As for the remaining 450 pages of the manuscript, it took him four years of documentary research and conversations with former comrades to recreate them. More importantly, even, Gerlach denied any knowledge about the contract that Schmitz was talking about. Only when a graphologist certified that the signature on the contract was indeed his did Gerlach give in. Asked by a reporter whether the contract might have been signed under hypnosis, Gerlach said that he would ‘take good care not to arrive at such a conclusion. But I can say that the therapy put me into a certain form of bondage.’Footnote 75 The dispute dragged on for three years before it was settled in front of a court. Gerlach formally acknowledged that Schmitz's therapy had aided him substantially in the recovery of his memory and he agreed to pay him a share of his royalties, 9,500 Deutsch Marks.Footnote 76

The story of the power of the hypnosis sessions alone was more than worth this price. When Gerlach published his account he competed with the memoirs of dozens, if not hundreds, of other Stalingrad survivors.Footnote 77 In this West German competition for the best book on Stalingrad, Gerlach's claim about a secretly written camp manuscript confiscated by the Soviets and subsequently recalled under hypnosis, a story broadly disseminated by the magazine Quick and cleverly marketed by Dr Schmitz, gave him a decisive edge. In tune with the staunch anti-communist sentiment prevailing in West Germany during the 1950s, hypnosis suggested the revelation of a pristine war experience, written in defiance of the Soviet regime only to be violently repressed by it. Perhaps the biggest gain for Gerlach in propagating this story of a restored vision was its obfuscatory thrust: it managed to obscure the imprint of Soviet re-education on Gerlach's narrative and, indeed, his very sense of self.