ENVISIONING A POLITICS OF APPARITION

In the dark midnight hours of 11 December 2009, the Virgin Mary (al-‘adhra) burst into visibility against the skyline of al-Warraq, a working-class district on the neglected peripheries of Giza, Egypt.Footnote 1 Hovering within a glowing triad of crosses, the apparition attracted spectators to the Church of the Virgin and the Archangel Michael along the main thoroughfare, Nile Street, even in the inconvenient hours between dusk and dawn. Within days, the Virgin was being discussed far and wide by Christians and Muslims, Egyptians and foreigners, skeptics and believers. Reactions were diverse: A journalist announced to his friends, “Even if the Virgin appeared before my very eyes, I would deny her.” A cab driver explained, “It is a trick, a big laser show in the sky.” A young mother urged, “Why [forbid oneself] the joy that the Virgin brings?”

A few weeks later, on 6 January, after Orthodox Christmas Eve mass, three Muslims killed six parishioners outside a church in a drive-by shooting in the Upper Egyptian village of Nag Hammadi. These killings marked the beginning of a series of violent acts against Copts that continued throughout 2010, characterized in much commentary as the worst year of “sectarian violence” to date.Footnote 2 In November, Coptic clashes with state police in al-‘Omraniyya resulted in two deaths and the arrest of 120 rioters, and on New Year's Eve, a car bombing in Alexandria left at least twenty-three dead and over one hundred wounded. These incidents immediately preceded the 25 January revolution, and by way of contrast they highlight the triumphant inter-confessional displays famously enacted at Tahrir Square. These included sheikhs and priests leading mixed crowds chanting, “One hand! One hand!” Christians encircled Muslims in moments of ritual prayer and vice versa. Just days after Mubarak's downfall, the celebratory spirit of national unity was subdued by news of a church attack in Helwan, reportedly over a forbidden romance, and of rioters killed in Manshiyet Nasr. Months later, in May, two churches in Imbaba were torched in the midst of street battles between locals. Immediately after each of these incidents crowds of Copts and Muslims gathered in squares and organized conferences in performance of their national solidarity, seeking to dispel discord and regain the glory of Tahrir. This ongoing fluctuation between acts of sectarian violence to counter-assertions of national unity raises the question concerning where Copts figure in relation to the Egyptian nation and, more precisely, what form of “national unity” Copts envision for themselves and their Muslim co-citizens.

The present study is based on more than twenty-four months of fieldwork conducted intermittently between 2004 and 2011. I will draw on both ethnographic and historical material to analyze the relationship between holy images, church territory, and the politics of Coptic belonging in Egypt. In particular, I explore the politics of Marian apparitions, at a moment when the politics of Coptic belonging are the subject of much debate, as many Egyptians aspire toward an era of democracy in which minorities and women will play larger roles. Composing roughly 10 percent of the national population,Footnote 3 Egypt's “indigenous” Christians have been commonly regarded as a “religious minority,”—a designation once rejected among both Copts and Muslims, including by the leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church, Pope Shenouda. In the widely quoted words of journalist Hassanein Haykal, “Copts are not a minority, but an integral element of Egypt's unbreakable fabric” (Al-Ahram, Apr. Reference Haykal1994). Despite such claims, a political landscape of religious identities persists through national identity cards and various legal frameworks of administering personal rights, which makes it impossible for any Copts to extricate themselves from the minoritarian structure of national belonging. For a number of intellectuals and activists, the solution to sectarian divisions lies in a new “secular state” (ad-dawla al-madaniyya) in which an enlarged and robust civic space, devoid of religious authority and influence, serves as the grounds for equal citizenry. And yet, as many of these same individuals openly admit, establishing a substantive basis for national belonging in Egypt, with “deep attachments” and “emotional legitimacy” (Anderson Reference Anderson1991), will be a formidable task if all forms of religiosity are removed from the political imagination.

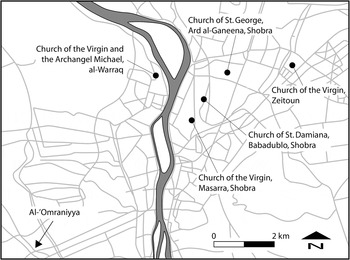

Marian apparitions, I argue here, offer us valuable and much-needed insights into how the Coptic Orthodox tradition of saintly imagination sustains the potential to exceed the minoritarian logic of the nation-state. They do so by shifting contours of religious and national belonging. To their critics, images of an illumined Virgin in the sky are far outside the realm of the politically concrete or public commonality, and perhaps even outside the speculative luxury of academics who are all too distant from the urgencies of church burnings and panicked calls for national unity. In this essay I follow the ethic that we should try to comprehend the significance that others find in what may seem negligible; it seeks to stay close to how visionaries value the Virgin, and to understand how her public appearances affect landscapes of visibility and violence. I should note at the outset that we err if we perceive such events to be “Christian” as opposed to “Muslim”: there are Muslim eyewitnesses who believe they are true and also Christian skeptics, both Orthodox and Protestant, who deny their reality. In Egypt, Marian apparitions are frequent and sustained enough to animate reliable, commemorative ties to saintly power. The apparition of al-Warraq in 2009 joined a lineage of recent apparitions and collective viewings in Egypt, including those of Assiut in 2001 and Babadublo (Shobra) in 1986. Most famous is an apparition that appeared at Zeitoun in 1968, which I will examine in detail in this essay (see map 1). As a number of ethnographers of Sufi cults across North Africa have thickly detailed (Gilsenan Reference Gilsenan1973; Crapanzano Reference Crapanzano1973; Pandolfo Reference Pandolfo1997), practices of saintly veneration and visionary experience, including those of the Virgin Mary in Egypt (Hoffman Reference Hoffman1995; Mittermaier Reference Mittermaier2011), flourish and shape the public landscape of divine mediation. Given how prevalent the mediation of saintly activity is, how do we take serious, attentive account of the political logic and effects of Marian apparitions?

Map 1 Map of greater Cairo showing church sites where Marian apparitions were sighted.

For the most part, research on Marian apparitions has focused on occurrences in Catholic Europe, the most prominent being those of Lourdes, Fatima, and Medjugorje.Footnote 4 A number of studies have analyzed apparitions’ social and political influences in terms of how they both consolidate and disrupt clerical orders (Christian Reference Christian1996; Reference Christian1981; Blackbourn Reference Blackbourn1994; Olds Reference Olds, Christian and Klaniczay2009), express popular beliefs and emotions (Turner and Turner Reference Turner and Turner1978; Scheer Reference Scheer, Christian and Klaniczay2009; Carroll 1992), and communicate responses to crises of war and national instability (de la Cruz Reference de la Cruz2009; Bax Reference Bax1995; Claverie Reference Claverie2003; Valtchinova Reference Valtchinova, Christian and Klaniczay2009). My interest lies in building upon this growing body of scholarship by exploring various forms of church authority and national belonging that are configured by apparition events across different historical moments and political contexts. In Egypt and elsewhere, Marian apparitions have certainly served as vehicles of priestly instrumentality, ideological symbols of nationalism, and occasions for vocalizing competing confessional claims to truth. I want to argue here that the making of religious and national authority entails all of these, but also much more. The topography of Marian apparitions is far from isomorphic with the terrain of national-identitarianism, that is, of a national unity in which religiosity is reduced to a form of identity expression or political utility. What the Virgin can elucidate for us is a mediating infrastructure of otherworldly origin.

As many scholars have shown, in different ways, various modes of mediation are integral to the making of both a national imagination (Anderson Reference Anderson1991; Ivy Reference Ivy1995; Shryock Reference Shryock1997; Messick Reference Messick1996; Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod2005) and a church body politic (de Certeau Reference de Certeau1992; Castelli Reference Castelli2007; Milbank Reference Milbank1997; Mondzain Reference Mondzain2005). As vehicles of saintly intercession (shafa'at al-qadiseen), Marian apparitions extend the politics of national and Christian belonging into spaces where divine power and presence is availed, accessed, and distributed. As saintly likenesses of the Virgin, they link and organize the earthly relation to heavenly authors and institute “the visible body of Christ”—they render the church perceptible. In communicative relation with other holy images like relics, they inscribe a theological polity of saintly belonging—a body of intercessors. To intercede, one on behalf of another, is to advocate for others through the representation of images. Again, this activity is not strictly “Christian” because the scope of intercession is not restricted to the Coptic Orthodox Church; it includes Muslims and even other Coptic Christians. The politics of Marian apparitions, and of saintly mediation writ large, converges in spaces where nations and church body politics are imagined.

I will examine the effects of intercessory images with two purposes in mind. First, rather than presuming the foundational status of either the nation-state or the clerical order, I will explore the historically untidy and shifting entanglements of nation and Christendom. Nation and church are not so much distinct institutions of belonging as they are different modalities of imaginary mediation that have historically emerged in a shifting and at times overlapping interrelationship.Footnote 5 My second, related purpose is to consider the possibility of a politics of mediation that extends beyond the recursive trappings of religious identity—in the case of Copts, of minoritarianism. I will discuss how the politics of intercession is distinct from the politics of clerical arbitration and state citizenship, and how it puts forward a representational order that transcends the marginalizing terms in which Coptic Egyptian belonging continues to be cast.

More specifically, I ask how church territory tracks the contours of intercessory mediation and the spatial grounds of Coptic belonging, both national and Christian. What is the nature of the space of the Church? What is at stake in its destruction and growth? By “church territory,” I do not mean territorial inscriptions of sectarian belonging—Muslim or Christian in the case of Egypt—that are stable designations of religious exclusivity across spaces and time. Their distinguishing feature is their consistent and relatively stable occurrence near the domes and steeples of Coptic Orthodox church buildings. This is a significant ritual form in the spatial politics of the Marian presence. As scholars of apparitions and saintly visions have found elsewhere, images of saintly disclosure and distribution often lead to the building of new sites of veneration, particularly shrines, churches, and monasteries (Christian Reference Christian1996; Olds Reference Olds, Christian and Klaniczay2009; Valtchinova Reference Valtchinova, Christian and Klaniczay2009; Mittermaier Reference Mittermaier2011). In Egypt, church-building and the topographical expansion of saintly likenesses take place in distinct contexts and moments, and these divinely political extensions do not correspond neatly to the politics of Muslim-Christian difference. I will argue that in fact it is a mistake to conceptualize church space as exclusively “Christian” territory. I will probe the histories of churches and church-building in Egypt as these structures are both “Christian” and “national” in the way they spatially intersect with the territories of nation-state and Christian empire, and also those of sectarian interests. In other words, Marian apparitions, through their appearances at multiple church sites, bring about political shifts and expansions across landscapes of varying scales and involving different polities.

What follows is a two-part examination of two Marian apparition events. The first part begins with the formal and phenomenal features of the most recent apparition, at al-Warraq in 2009, and then examines the territorial politics that define that Muslim-Christian segregated neighborhood. The second offers an alternative history of what is perhaps the most famous apparition, at Zeitoun in 1968. I will highlight the territorial stakes surrounding the Arab-Israeli war of 1967, and Coptic Orthodox relations with the Roman Catholic Church as they stood at the time of that apparition.

TOPOGRAPHIES OF MARIAN INTERCESSION

To recognize a Marian apparition as truthfully divine, one must remember how the Virgin came before, and anticipate how she will return (Hanks Reference Hanks1990; Keane Reference Keane1997). In the words of one eyewitness, “The Lady Virgin comes in the language in which we understand her.” Among Coptic Orthodox Christians, the Virgin is understood to assume standard form in individual visions and dreams as well as in her public appearances. Al-manzar at-tagali (“the vision of apparition”)Footnote 6 consists of the Virgin dressed in a blue and white robe, her waist wrapped in a belt, and her head encircled by either a crown or a halo of light.Footnote 7 Unlike the Marian apparitions of Lourdes, Fatima, or Medjugorje, in collective apparitions in Egypt the Virgin does not communicate through appointed mediums or seers, and is entirely speechless. According to reports gathered at different sites (e.g., Zeitoun, Assiut, Shobra) the Virgin's arms are outstretched, moving at times as if blessing a crowd, or she is holding something in her hands. The radiant image of her body is nearly always accompanied by the unnatural flight of luminous doves at nighttime. Doves are considered an “expression of the Virgin” (ta'abeer al-‘adhra), and the Virgin is referred to in praises as a “beautiful dove” (hamam al-hasuna).

Eyewitnesses described these characteristic features, but also emphasized the way in which the Virgin was made visible. What makes the Virgin of al-Warraq authoritative for spectators is not only what she looked like, but how she appeared in space. Like past apparitions in Egypt, this one was suspended high above, and moved between the church dome and two steeples as a bright, bluish-white light that emerged out of the midnight sky. As one eyewitness conveyed the force of her radiance, she was “a big light,” like “the explosion of a luminous planet” (infigar kawkib noorani). The drama of the Virgin's image, with interruptive brilliance at such great heights, drew viewers’ gaze toward the Church of the Virgin and Archangel Michael in al-Warraq. Sightings were reported from rooftops near the church but also from as far away as Ma'adi and Faisal districts 15–20 kilometers distant. Muslims and Copts alike were among both the witnesses and those who were there but saw nothing. Clear to all was the way in which the Marian apparition magnified the church site as one of visitation and future memory, in the way she is ritually imagined to appear in the past and faithfully return. This spatial redistribution of visibility, one that raises church territory into miraculous exposure, is the very form of her intercessory power.

Within days of the first sightings, television stations aired images of the apparition that people had captured on their mobile phone cameras. On one popular daily show, al-Qahira al-Yowm (‘Cairo Today’), hosts Amr Adeeb and Moustafa Sidqy discussed with two Coptic Orthodox priests the distinctive form that the Virgin Mary assumes in Egypt and its significance. Father Saleeb of Saint George Church in Shobra described a national topography of Marian apparitions:

These events are Egyptian, not Christian events, because they belong to all of Egypt. And it is not strange that the Virgin appears in Egypt but it is strange that she doesn't appear. Because the Virgin doesn't appear in the heart of Egypt, but Egypt is in the heart of the Virgin [his emphasis]. Right now, Egypt is in the heart of the Virgin herself. This is not the first appearance of the Lady Virgin. As you said, [in history books, there were other apparitions], and she appeared to Pope Abraham, Ibn Zura'a, the 62nd Patriarch during the days when Muqattam Mountain was moved. And she appeared to Haroun Rashid when the Church of Atreeb was about to be destroyed.…Footnote 8

In this description to a largely Egyptian audience, Father Saleeb crafts a commemorative topography of Marian presence that highlights al-Warraq as a national site of blessing. Copts often recite the phrase “Blessed be my people Egypt” (Isaiah 19:25). Rather than comparing the apparition directly with European ones, he draws upon an Egyptian and more specifically a “Coptic” history of apparitions to foreground the iterability of divine power in national form. This does not merely assert the prominence of the Coptic Virgin over and against other “national” Virgins; it also suggests that the Virgin is remaking space and history, the parameters by which Egypt is inhabited and remembered.

In Coptic Orthodox liturgical memory, both Muqattam Mountain and the Church of Atreeb are sites that mark the Marian salvation of church territory through visionary experiences during different periods of persecution. More widely known is the “Miracle of Muqattam,” in which the Virgin's appearance to Pope Abraham in a dream ultimately resulted in the moving of a mountain outside of Cairo in a divinely authored response to the caliph's demand for a sign.Footnote 9 Such a sudden twist in landscape reverses the fate of the Coptic community, from one of expulsion or death to growth in the promise of new and restored churches. Less known, but often reenacted during the Fast of the Virgin in August, is the deliverance of the Church of Atreeb near present-day Benha (Qalubiyya) (Map 2). In this narrative, the Virgin appears to the Caliph Haroun Rashid in Baghdad and orders him to send a signed missive to Cairo by way of a dove, in order to halt the destruction of the magnificent church. In both of these cases of visually mediated intercession, Marian power is transmitted through a dream in which, unlike the collective apparitions, she communicates to individuals. Nevertheless, Father Saleeb's recollection of these images foregrounds the political possibilities entailed in apparitions, since they form part of a deeper lineage of the Virgin's faithfulness to Egypt, understood through the infrastructural consequences of her appearance on endangered territories.Footnote 10

Map 2 Map of Egypt showing places referred to in the text.

The Marian apparition of al-Warraq, with her expansive, saintly presence, elevated multiple churches simultaneously: “The Virgin was not confined (mahdooda).”Footnote 11 Within days of the initial sighting of the Virgin “at-tagali”—as an illumined bodily silhouette—witnesses reported seeing her over several nights in the form of doves in nocturnal flight at churches in neighboring Shobra and in al-Warraq. The majority of eyewitness accounts detailed the images and movements of doves.Footnote 12

An older woman from the Church of the Virgin and Archangel Michael at al-Warraq recalled, “I came to that steeple [she points], and I found doves flying, two doves and before that, one white dove. A white dove at 2 a.m. It was flying toward the church and then came back again.” A teenage boy of the Church of the Virgin in Shobra al-Haafziyya remembered, “There were crowds gathered in front of the church and when we left the house, we saw the steeple and there were doves. And their appearance was abnormal; they looked strange and now there is a halo of light that is moving in the sky.” A younger mother of the same church said, “We looked and we saw big doves coming from the Nile, and I found them around the church, and afterwards they came to the ground as people were cheering very loud, and each time they cheered the doves would come down a bit as if the were patting [the backs] of the people.”Footnote 13

It was widely understood that the doves were the spectral offspring of the originary Marian figure of 11 December, saintly images that distributed her blessing to surrounding areas. These areas included three churches in Shobra: the Church of the Virgin in al-Haafziyya, the Church of the Virgin in Masarra, and the Church of Saint George in Ard al-Ganeena. Moving fast and lingering at great heights, they communicated comfort and joy at church sites, drawing crowds and summoning attention to various church locations mapped as kindred points of divine visitation. Through bursts of light and the travel of doves, these churches of greater Cairo moved to the forefront of the urban landscape.

Such signatures of intercessory activity compose and extend an imaginative topography of Marian power. The appearance of doves at multiple churches quickly gathered spectators who experienced and witnessed the Virgin's signs and remembered other such events of the past. It is the particular blessings bestowed upon various church sites, and the memory of churches that endured threats of destruction, which indicate the Virgin's spectacular care for Egypt. In her regular form, phenomenal and territorial, Marian apparitions illumine a national terrain of divine mediation, weaving neighborhoods, cities, and buildings into interrelated places of commemoration. In doing so, they palpably change how these new sites are inhabited and what viewers might envision as miraculous transformations in the future. The authority of Coptic churches to intercede on behalf of Egypt turns upon these acts of eyewitnessing and anticipation. In this kind of political imagination, what are at stake for the status of church territories are not merely locations of religious identity, but also related places of national belonging.

BUILDING CHURCHES IN SEGREGATED SPACES

“It should have been illegal.” Father Bishay is speaking to me of al-Hoda mosque down the street, and how its newly reconstructed building carves meters away from Nile Street, the main thoroughfare in al-Warraq district. As one of the priests of the Church of the Virgin and Archangel Michael, Bishay has endured the changing tides of the working-class neighborhood of Giza, a short distance across the river from the better-known Shobra district. Erected in 2000, the church's steeples and crosses once stood as the tallest structures among the shops and along the traffic of cars. Within just a few years, by 2002, the neighboring mosque extended its minarets upward and its base outward into the public road.

The building of churches in Egypt is among the pressing issues for religious rights activists, one in which church territory is conceived to be a right due to a “persecuted Coptic minority.” In recent years, locally presiding priests and government officials, representing church and state power, have negotiated the terms for establishing and expanding places of worship. Permits required for church-building and repair are issued at the discretion of provincial governors and are notoriously difficult to acquire in a timely fashion.Footnote 14 The district of al-Warraq, a transit point across the Imbaba Bridge from Rod al-Farag to the Delta, is populated largely by textile workers. Since the 1970s, the Coptic population has risen steeply, due mostly to an influx of rural migrants; Cairo housing is now overcrowded. This has necessitated more sites for worship and improvements to church facilities. The first Church of the Virgin, which locals call al-athariyya (“the old one”) or al-‘adhra ‘and ag-gazaar (“the Virgin next to the butcher”), has existed since the early 1900s, tucked behind the alleyways off of Nile Street. Along with an older and smaller church located some 250 meters away, the Church of the Virgin and Archangel Michael serves the growing Coptic community. The church that faced the most serious challenges during its construction, in the late 1990s, is the Church of Saint Mark, located on the island al-Hadar, part of al-Warraq. In order to reduce the church's visibility, state officials ordered the priests in charge to have tall, forbidding walls built that concealed the domes and steeples. According to Father Bishay, neighborhood anxieties surrounding the new cathedral were high enough to prompt state appeals to public order: a seeable church might pose a substantial threat to the Muslim-Christian order.

Marian apparitions draw attention through a brilliant, panoramic burst of light against the dark sky. As described earlier, nearly all of the sightings, including the one at al-Warraq in 2009, have assumed perceptible form in ritually repetitive fashion near the towering dome and steeples of a Coptic Orthodox church during midnight hours.Footnote 15 From speaking with its inhabitants I learned that al-Warraq is a district thick with tension (at-ta'asub) between Muslims and Christians, exacerbated by the segregated order of residential spaces. Like most neighborhoods in Cairo and Giza, it is composed of mixed religious groups, but its most distinguishing feature is its division by sharp territorial lines. The Church of the Virgin and Archangel Michael functions as a conspicuous boundary-marker, and as we peered down from its rooftops, two locals explained to me the divided lay of the land: the majority of homes on the church's north side are occupied by Muslims, and on its south side by Copts.

In such spatially segregated conditions, the publicity of saintly apparitions is the domain of state control and regulation. When the Virgin appeared at the church, Nile Street was quickly flooded with crowds of tourists and pilgrims, prompting the arrival of Egyptian state security personnel. Competing with the forceful heights of divine light and the whirling movement of doves, the police worked to dampen the perceptibility and occupation of the saintly image. Within days of the Virgin's abrupt arrival, her reappearances circulated through the Internet, mobile phones, and television, and state security trucks became a constant presence at the church's main doors. Streets and public environs surrounding the apparition event were cleared of pilgrims and journalists and became spaces of state regulation and control. Visitors could only witness the apparition from within the confines of the church itself, into which they had to shuttle single-file past and under the surveillance of guards.Footnote 16 In similar fashion, the state carefully monitored the production and circulation of replicas of the church site and of potentially miraculous images. All photographers, journalists and pilgrims alike, had to show a state-approved permit to enter, and photographs of the apparition were confiscated.

In al-Warraq, priestly custodians of church buildings have been generally obliging of a police presence in times of heightened church visibility. Its parishioners, though, have long been suspicious of state security; they think that it provides inadequate protection, and even suspect that it has been complicit in acts of violence around churches.Footnote 17 In the cases of the Nag Hammadi killings of January 2010 and the Alexandrian car bombing nearly a year later, Copts were angered by a notable absence of state protection of church sites. Human rights activists worldwide pointed to the police surrounding the al-Warraq church and the failure to protect Christians in Nag Hammadi as evidence of minority persecution in Egypt. Prior to the attacks during midnight mass, Bishop Kyrollis of Qenas province had alerted police to threats made against his parishioners. Days later, Coptic protestors demanded of General Mahmoud Gohar: “Why can't you protect us, General?” Amidst the fires and lootings that followed, and murders in neighboring districts of Nag Hammadi, charges against the police resounded: “Where is our security?” After talk surfaced of a Marian apparition at the Church of the Virgin in Nag Hammadi, it was quickly quieted by governing priests trying to deflect attention away from the church.Footnote 18 In this fragile period of sectarian tension, they knew, a miracle-image would draw Christians into a public and vulnerable position.

At the same time, violent acts and apparition events can generate opportunities for church expansions into new places. Events and images, interwoven by strands of coincidence (de la Cruz Reference de la Cruz2009), have varied effects upon the realm of potential territories of intercession. Outbreaks of sectarian violence in one place can have consequences for the political dynamics of Christian-Muslim space-making elsewhere. For example, the dead of Nag Hammadi were seen to be martyrs, and this opened new opportunities for church-building in al-Warraq. In 2000, when the Church of the Virgin and Archangel Michael was renovated and new administrative offices were added, it grew taller, but to the happy surprise of its priests the state did not protest. Father Bishay told me a theory in local circulation: “In 2000, the government was nervous after the Kosheh massacres. It let us do whatever we wanted.”Footnote 19 The Nag Hammadi killings have often been referred to as the “worst case of sectarian violence in Egypt since al-Kosheh,” and are cited as exemplifying the state's failure to protect its Christian minority. Unlike its sibling church on the island, the church along the Nile constructed towering steeples and domes even while under state surveillance.

Apparitions articulate risks and opportunities for the churches where they occur. Whereas the Virgin of Nag Hammadi was obscured from public recognition, her image in al-Warraq caused a sensation. In both cases, both clerical and state political authorities were wary of the hazards that heightened church visibility might bring. Apparitions, as vehicles for expanding church space, are here partially assimilated into a sectarian-identitarian landscape of minority endangerment. In neighborhoods that are divided and embattled, such as al-Warraq, the possibilities for spatial occupation are shaped by the unevenness of publicity and state security. Residences and places of worship, as sites of violation and reconstruction, reveal lines of territorial conflict and structure terrains of religious rights. In such topographies of competition, building churches entails more than gaining the necessary government permits and enforcing minority rights for equal opportunity; it also draws traffic of devoted viewers and holy images into tense spaces. The publicity of apparitions makes saintly veneration a problematic, political affair.

DYNAMICS OF INTERCESSORY POWER

In recent years, the Coptic Orthodox Church has been widely criticized for unwelcome meddling in the civic and political affairs of Copts. In situations ranging from conversion scandals, to bans on divorce, to property disputes, Pope Shenouda III and the highest-ranking bishops have regularly assumed the role of arbiter between Coptic Christians and the Egyptian state. Consequently, there is an increasing identification of “the Coptic community” and “the Coptic minority” as a single, coherent political unit, even though Copts in fact belong to disparate denominational orders and have varied interests vis-à-vis the state and society. Many activists and commentators have cogently argued that the ascendance of the Church as a political actor, which speaks in the name of its designated beneficiaries, has stripped Copts of their capacity to fully negotiate their rights as state citizens and members of the civic public (Fawzy Reference Fawzy2009; Morcos Reference Morcos2002; al-Gawhary Reference al-Gawhary1996; el-Amrani Reference el-Amrani2006).

What such criticisms highlight are the particular forms of church power and political mediation that have crystallized during Shenouda's papacy and the Mubarak regime, and the ways in which both consolidated the minority status of Copts as a group to be governed by church and state authoritarianism. Scholars have characterized recent transformations in Coptic Orthodox Church politics in terms of two main features. First, the Church's internal government has become more centralized, with decision-making capacities concentrated in the hands of the Pope and a few presiding bishops (Hasan Reference Hasan2003; Makari Reference Makari2007).Footnote 20 Second, the Church has promoted allegiance to the Egyptian state in exchange for concessions—a bargain that political scientist Mariz Tadros (Reference Tadros2009) has referred to as a church-state “entente.” This relationship was significantly strained in the late 2000s. These same studies show how the political representation of Copts is shaped by shifts in the organization, ordering, and distribution of church power. More specifically, the minoritarian status of Copts, far from being a natural identity, is inextricably enmeshed with specific forms of religious and state authority. To explore an alternative terrain of Coptic politics, we need to consider various modalities of church power and the ways they differentially shape Copts’ relationships to the nation as a whole.

I want to understand how saintly intercession structures a politics of Coptic belonging in relation to imaginaries of both national and Christian character, how a politics of divine mediation situates Copts within shifting terrains of nation and Christendom. Recalling Father Saleeb's assertion, “Egypt is in the heart of the Virgin,” how might we identify and analyze the effects of saintly activity by examining how national and Christian belongings are interconnected and perceived? Against the aim of eliminating religion from Egypt's political affairs, I want to explore how various types of religious mediation introduce a political imagination different from that generated by church and state authoritarianism. We can begin with a mode of Coptic representation that exceeds the narrow scope of papal domination or clerical arbitration, since the church's interventions are not always equal to acts of saintly intercession. In order to understand the grounds for intercession we must seriously engage religious beliefs about divine authority and examine their implications for national and geopolitical imaginaries of political belonging.

Saintly intercession—the advocacy of one saint for another—relies upon bodies and objects that make divine presence palpable, things that some Orthodox theologians call “sacramental” (al-Miskeen Reference al-Miskeen1952; Lossky Reference Lossky1976). At the heart of intercessory practice lies a material dynamics of hiddenness and visibility, potential and exposure. Saints, like the Virgin, serve as communicative “middlemen” (al-wasta), vehicles that doubly represent and mobilize fleshly longings, desires, pleas, and grief, as well as thanksgiving and praise. As the material substrate of intercessory activity, images form an integrated network of saintly “likenesses” whose efficacy depends upon other likenesses: apparitions, icons, oils, and relics, and bodily practices of remembrance and virtuous imitation. The contexts of apparitions, therefore, include other images, both corporeal and transitory, that are variously positioned relative to each other. To comprehend the Virgin's efficacy in al-Warraq one has to understand the dynamics of divine representation and mobility, worked out in time and space through saintly likenesses. This requires that we track the accessibility and contiguity of images, and the ways in which Marian apparitions produce an infrastructural imaginary in concert with other vehicles of holy mediation.

In the establishment of a church polity, the convergence of nation and Christendom begins with the foundational act of saintly imagination—martyrdom. The history of the Coptic Orthodox Church begins with Saint Mark, its founding apostolic figure (Davis Reference Davis2004; Telfer Reference Telfer1953; Reference Telfer1955), whose martyrdom marks the origin of church expansion in Egypt. Copts often say, following Tertullian, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” In the figure of Saint Mark, saintly powers and clerical authority are combined: as the revered martyr, he is the icon of a death honored in heaven, and he is the first in the papal line, the predecessor of Pope Cyril VI (1959–1971) and Pope Shenouda III (1971–present). In this way, saintly mediation, rather than subsuming priestly representation within nation-state politics or minoritarian belonging, organizes a national imaginary in which the clerical order is part of a diffuse structure of remembrance, of originary death and the passage of papal power. Put another way, the Coptic Orthodox papal-clerical lineage, as the foundation of the “national church,” relies upon commemorative acts of martyrdom, and the continuous making of both Christian and Egyptian contours of belonging.

Relics are the media through which martyrs are remembered, and they invoke and authorize saintly presence in the spaces where they reside. The Coptic Orthodox Church extends itself through the distribution of martyrs’ body parts. In addition to the Cathedral of Saint Mark, another main church that serves the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate is al-‘Abbasiyya, a small shrine devoted to the martyr-saint. Adjacent to the Cathedral of Saint Mark, the main church of the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate in al-‘Abbasiyya, there is a small shrine devoted to the martyr-saint. It attracts many visitors, some of whom rest their heads on the tomb-like reliquary in its middle, which is enshrouded with layers of velvet cloth and plastic. Others stare at the icon panel that covers the walls, which is a narrative portrait of foundational violence—Saint Mark's body tied in rope and bleeding beneath a sneering Roman soldier. The stakes of remembrance are territorial in nature in that the commemorative imaginary generates spaces of memory with bodily fragments in physical proximity. Churches, monasteries, and shrines are erected as consecrated places where relics, icons, and other objects convey the memory of martyrdom. The movement of relics establishes the terrain of ecclesiastical power, and mobile pilgrims are drawn to the churches and shrines where they are kept. The circulation of visionaries and holy images links devotees with the papal-saintly origins of the church.

In her stunning study of the Byzantine Orthodox imaginary, Marie-Jose Mondzain asserts that “Christianity's true genius” was its attempt to “organize an empire [by] linking together the visual and imaginal” (2005: 151). In an “image economy” of dispensing divine power, circulating objects and traveling visionaries establish the parameters of a territory of sacramental proportions. Church territory is marked out and elaborated through the spatial grounds of visual imagination: relics and apparitions establish and bolster sites of saintly precedence and ritual visitation. The material forms of church expansion include distributions of images of intercessory activity such as relics, icons, and apparitions. The bodily and infrastructural visibility of saints turns upon the ability of such images to reproduce through remembrance their partibility, or their iterative appearances.

What state security officials found so alarming about al-Warraq was the traffic there in images and pilgrims and that the church attracted so much public attention. It should be noted here that the “church,” as composed of objects and their viewers, transcended the bounds of Coptic Christian identity, and state guards identified as a security threat the many foreigners, Muslims, tourists, and journalists who made their way there. Visiting one site after another, pilgrims accumulate different spaces of memory. Intercessory practices of pilgrimage join the visibility of images to ecclesiastical territory as the remembrance of a place grants it religious legitimacy. Churches are not significant merely as vessels for divine images; they are holy insofar as they distribute possibilities (Rancière Reference Rancière2006) for political expansion.

Both relics and apparitions are carriers of saintly presence characterized by a high degree of material instability: relics impart fragile incorruptibility, and apparitions transient corporeality. Through these, different saints emerge out of a nexus of the church's foundational pillars. If Saint Mark institutes papal-saintly authority through martyred parts, the Virgin Mary iterates maternal generativity through bodily light. As the unique Theotokos, or “bearer of God,” her distinguishing feature is her capacity to convey the divine and give birth to Christ's body—birth to the church.Footnote 21 Saint Mark and the Virgin Mary work within the same network of holy mediation, relics, and apparitions, and play a special role in legitimating the physical locations of churches and bodies and their orientation toward each other. Relic translations and apparition events materially structure opportunities for church-building and pilgrimage.

Aspirations for a church polity that is a “coherent whole” remain unfulfilled. The nature of intercessory space is such that contiguous sites of veneration are rare, and the distances between churches mean this is a scattered polity without enclaves of occupation. Saintly images lack integrity (relics) and defy permanence (apparitions), but the potential for imperial expansion relies upon their ability to break off ad infinitum, to appear and reappear without schedule—to be unstable. To remember the journeys of Saint Mark and the Virgin is a bodily practice that lays out the furthest reaches of Christendom. Objects of remembrance index at once the peripheries of empire and the attenuated lines of national territory. At times, these images invoke histories of conflict beyond the scope of the Coptic Orthodox Church, and signal toward other clerical headships and geopolitical orders. The next two sections delve into how relics and apparitions reveal the convergence of different political realms.

TERRITORIAL RETURNS OF WAR

The Marian apparition of al-Warraq in 2009 evoked deeper histories of territorial contests and alternative prospects for national unity. In 1968, one apparition usurped all others: the world-famous Virgin of Zeitoun, who night after night over two or three years drew millions of people to Tumanbay Street in the Cairo suburb.Footnote 22 Nearly forty years later, photographs of the Zeitoun apparition were the measure by which those of al-Warraq were evaluated. The events were compared in terms of everything from the Virgin's stance, to her crown and dress, to her movements and gestures. Zeitoun still serves as the benchmark Marian event that draws all succeeding apparitions in Egypt into the potential horizon of national history.

The Church of the Virgin sits on land that President Nasser endowed to the Coptic Orthodox Church in honor of the apparition. It was originally the site of a garage of the Egyptian Transportation Authority, and the first eyewitness of the Virgin, on the evening of 2 April 1968, was a Muslim driver named Farouk ‘Atwa who alerted the local priest to the “white lady kneeling at the dome.” By May, Pope Cyril VI had issued a papal statement confirming “the apparitions are true,” and the most important state newspapers published front-page photos of the Virgin and the attending crowds. The moment at which President Nasser submitted his eyewitness testimony to the papal investigation committee marked the alliance of saintly memory with national history. By 1974, the new church's first cornerstone had been laid, and consecrated by Pope Shenouda III.

Today, the Church of the Virgin in Zeitoun is a magnificent, double-cathedral complex that straddles the artery road: the older cathedral built in 1924, where the apparition stood, is less than 20 meters high, but the newer cathedral, finished by the late 1970s, measures several stories and towers over neighboring buildings. The new Cathedral of the Virgin is recognized as the second largest in the Middle East, by surface area, superseded only by the Cathedral of Saint Mark in the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate of al-‘Abbasiyya. Near the regal sanctuary sit buildings for practical purposes, including administrative towers, dormitories, a hospital, and a charity center.

The Arab-Israeli war of 1967 is the principal historical event that explains the national prominence of the Zeitoun apparition from 1968–1971. The Virgin of Zeitoun became a topic of discussion and analysis among Arab nationalists like Syrian intellectual Sadiq Jalal al-‘Azm, who in his Naqd al-Fikr al-Dini (Critique of religious thought) (Reference al-‘Azm1969), wrote with frustration, “It will not help us gain our national and vital rights if the Virgin was angered, or not, by the loss of Jerusalem.”Footnote 23 Anthropologists (Nelson Reference Nelson1973; Hoffman Reference Hoffman1997) attributed the collective nature of the phenomenon to the shared national experience of “chaos” and “self-doubt and questioning” that were the byproducts of military humiliation. There is certainly truth to this, but the relation between war and miracles involves more than social meaningfulness and psychological vulnerability. If we understand that the political impacts of the Arab-Israeli war were more complicated than simple demoralization, we should analyze the apparition's impacts in the same complex terms. We need to examine the entanglement of territorial violence from the 1967 war with the intercessory expansion brought about by the Virgin of Zeitoun in 1968.

Shifts in the territorial landscape of nation-states have been closely tied to the topography of saintly power.Footnote 24 The 1967 Arab-Israeli war resulted in Israeli capture of the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights, all of which were soon labeled “occupied territories.” In the 1970s, Israeli authorities granted to the Armenian Church Coptic territorial rights over the stairwell in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (Cohen Reference Cohen2008). The effects of war on mobility across borders transformed saintly spatial priorities. Even before the Coptic Orthodox Church struggled to retain its partial custodianship over holy sites in Jerusalem, Pope Cyril VI, in a show of solidarity with Arab states, prohibited pilgrimage to Israel (a ban still maintained by Pope Shenouda III).Footnote 25 Pilgrims who travel outside papal jurisdiction can be punished by excommunication—expulsion from communication with holy signs.

Provisions were made to allow access to saints, however. Sadiq Jalal al-‘Azm directed his Marxist critique at the reasoning of Zeitoun visionaries who claimed, “The Virgin visited because we could not visit her” (al-Watany Report 1968). At the heels of the 1967 defeat, 1968 was a watershed year for enlarging the Coptic Orthodox terrain in Egypt. That spring, two of the Middle East's largest cathedrals were made publicly visible, through different means. Both were in Cairo, only 5 kilometers apart. The first event, in June, was the inaugural consecration of the Patriarchate Cathedral of Saint Mark in al-‘Abbasiyya, a celebration of the newly finished papal complex for the Coptic Orthodox Church.Footnote 26 President Nasser had laid its cornerstone in 1965 (Meinardus Reference Meinardus1970).Footnote 27 The second was the apparition in Zeitoun in April, which served as the miracle-catalyst for planning the newest addition to the global itinerary of Marian pilgrimage, on land gifted by the state. In this image economy, holy images lost to Israel in the war were reclaimed by constructing new spatial-imaginary venues.

With holy Jerusalem now inaccessible to pilgrims, the new venues in Cairo helped shift attention to Arab sites of divine presence. As a “problem of presence” (Abu el-Haj Reference Abu el-Haj2001; Engelke Reference Engelke2007), claims on territory are part of a broader set of practices that link land with memory, and material replication with future possibility. Pilgrims heading to Zeitoun honor the Marian visitation to Egypt, the apparition being a reminder that God has long favored the country. The preeminent refugee from Israel is the Virgin, and her flight with the Christ-child in tow set the archetypal pilgrimage itinerary. Devotees follow her in a commemorative veneration of places: from Bethlehem to the Nile Delta, and southward to Assiut. With historical-theological clarity, Stephen Davis describes pilgrimage as the “reenactment of the Incarnation” in which both “bodies and territory are transformed into ritual sites” (Reference Davis2008: 113). Such ritual sites are reproductive, fertile, and restorative. Landmarks of Marian visitation represent expansive possibilities borne out: the sycamore tree of Matariya miraculously rooted, the dried well renewed in Harat Zuwayla, the resurrection of a dead man in Bilbays. Pilgrims across the world recognize the miracles of healing that occur in Egypt's holy sites, with the churches of Zeitoun and al-‘Abbasiyya annexed to bodily memory.

Image reproduction can drive violent expansion; when intercessory dominion overlaps with state territory, saintly images can propel acts of conquest across borders. The Virgin of Zeitoun is a Janus-faced sign of peace and war. In Pope Cyril VI's papal statement released through the state press, he spoke of her: “She is a harbinger of peace and speedy victory … the salvage of the Holy Land and the entire Arab land from the hands of the enemy. We shall triumph in God's Name” (Meinardus Reference Meinardus1999; Hoffman Reference Hoffman1997). Here, papal prophecy converges with a Nasserist vision for a unified Arab state in a political-theological promise of military reclamation. In its transitory occupation of Zeitoun, the Marian apparition supports a durable, territorial vision of Arab nationalist justice set down upon the Egyptian landscape. At the new cathedral in Zeitoun, parishioners and visitors commemorate and re-invoke the Virgin's fidelity, inflected with postwar ferocity.

As many writers have observed, the Virgin, “Magna Mater,” and “Um al-Noor,” serves as a figure of translation across Christian and Muslim traditions. During my time in the field I was often told of Muslim pilgrims visiting the monasteries and churches of the Virgin, though there were only a few. The Virgin is polysemic and she is exchanged across denominations and nations, making her an important presence at boundaries of identity and difference. In Zeitoun in 1968 she was most important as an icon of national unity, as the emblem of Coptic-Muslim integration and co-citizenry. This suggests that the collective sightings of the Virgin must be understood as they occurred on the phenomenological ground of nation-state history, and that Egypt's military defeat led to this miracle of inter-religious experience.

Territorial loss represents more than an issue of state politics, since it is enmeshed with spatial practices of invoking holy power. In the context of the Virgin's repeated appearances, her disappearances signal histories loosely held together in a dynamic set of images and bodies—in topoi of saintly passage across religious identities. As I have detailed here, a shifting assemblage (Sassen Reference Sassen2006) of erected churches, commemorative practices, and saintly images make for an intercessory polity with the potential for national growth. In the case of Zeitoun, apparitions of the Virgin make Egypt into a site of both Arab territorial contest and Marian pilgrimage, wedged between spaces of political nationalism and intercessory power.

HISTORIES OF ECUMENICAL DISPOSSESSION

In 1968, Israel was not the only foreign power with an increasing territorial presence in Egypt. In June of that year, Pope Paul VI of Rome presented the delegation of Pope Cyril VI of Alexandria with a small particle of bone from Venice, a relic of Saint Mark.Footnote 28 In the minds of some Copts, Saint Mark and the Virgin had a public relationship, as one eyewitness of the Zeitoun apparition explained to me: “The Virgin came to bless the return of the relics of Saint Mark.” By their simultaneous “return” to Cairo, holy apparitions and relics acted as intercessory vehicles, circulating in a shared economy of saintly presence and instituting the territorial contours of divine power in Egypt. The relics arrived, sent by the Vatican as a sign of good will, in time for the inauguration of the new Coptic Orthodox papal headquarters in al-‘Abbasiyya. This movement of Saint Mark's remnants congratulated Coptic Church growth, represented by the new administrative centers of the Patriarchate complex, which were themselves a response to a substantial increase in lay participation in church activities that had started in the late 1950s.

Christianity, as an “ecumenical” religion (Ho Reference Ho2007), pursues the institution of Christendom worldwide in ambitious if sometimes unwieldy fashion. Through various empires—Roman, Persian, Byzantine, Arab—the Coptic Orthodox Church, as Egypt's “national” church, has been accustomed to geopolitical instabilities entangled with shifting configurations of trade, territory, and political loyalties. A politics of “ecumene” (oekumene, “inhabited world”) is one of “visible order,” of empire established through world-making.Footnote 29 In ancient Greek and early Christian contexts, such world-making activity secured territorial dominion through a sense of “saintly existence” (Voegelin Reference Voegelin1962). The Coptic Orthodox, referred to as “anti-Chalcedonian” in reference to their break from the victors of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, are often distinguished by their Christological confession as “monophysites.”Footnote 30 What this identification conceals is the territorial nature of imperial violence and its impact on the saintly foundations of the Coptic Orthodox Church. According to Coptic liturgical memory, Saint Mark was martyred at the hands of an expanding Roman Empire. Here, we might consider Chalcedon less as the touchstone of Coptic Christian identity and more as representing one of many conflicts within a deep, intractable history of tensions between the Coptic Orthodox and the Roman “Melkite” (malik, “ruler”) churches.Footnote 31

Relics work ambivalently in the making of Christendom, at once forging unities and causing fractures. As the commemorative media of martyrdom, they represent the presence of founding saints. The givers and receivers of relics are made spiritual kin through the media of metonymy, and they signify a saintly-bodily whole, although one attenuated by contested histories. The movements of relics convey different valences, depending upon how their passage is perceived, whether they are seen to travel via friendship, dominion, theft, or as gifts. Relics institute bishoprics, the terrain of ecclesiastical headship. Their transfer is not so much an act of diplomacy as one of imperial rule, creating as they do asymmetrical relationships of gift exchange.Footnote 32 Relics have a proclivity for “breaking from cultural context” (Geary Reference Geary1991), and thus they also mark discontinuities, disseminated as residual traces of conflicts unresolved and lineages dispossessed. More strongly stated, even as Christendom expands through the circulation of relics, in doing so it can produces internal, “sectarian” divisions. Relics can disrupt ecclesiastical unity.

It is significant that Copts used the term “return” (al-i'aada) to refer to the travel of Saint Mark's relics from Rome to Cairo, rather than “translation” (al-intiqaala). For Rome, the gift of favor fortified “unanimity and concord” (Brown Reference Brown1981), whereas for people in Cairo it affirmed a just homecoming. The shattering of the apostolic body not only disseminated seeds of the new church, but also sowed future cleavages within Christendom, deposited in fragments across the space of empire. In response to Pope Cyril's request for Saint Mark's body, ownership was transferred from Cardinal Urbani of Venice to the Coptic Orthodox papal crypt. For both the Venice and Cairo churches, the location of their shared patron saint inscribes the legitimacy of saintly ancestry onto place. There is a long history, familiar to Copts, of imperial urgings from the Pope to recognize Rome over Alexandria (Sharkey Reference Sharkey2008). Practices of benevolent “catholicity” suggest dubious, if expropriative claims to a common belonging.

Following Vatican II in 1965, Coptic Orthodox relations with the Roman Catholic Church were strained by alliances of Christianity and nation. Pope Cyril denounced Rome's absolution of Jews from Christ's crucifixion as “an imperialist-Zionist plot against the Arab nations and Arab Christians” (Meinardus Reference Meinardus1999). The losses of land that soon followed were seen to confirm this accusation. Following the war of 1967, Bishop Samuel (the bishop-pioneer of “ecumenical” relations) linked the fate of Israeli Jews to that of Roman Emperor Julian who died while battling Persia's military conquest.

Popular folklore casts Venetian sailors of 827 as the thieves who stole Saint Mark's body from Alexandria. But the story of its dispossession arguably began centuries earlier. In his widely circulated account, “Saint Mark the Evangelist,” Pope Shenouda's history of the apostle's head and body begins with Roman persecution from 451–644, the period between the Council of Chalcedon and the Arab conquest: “The Roman Melkites confiscated our churches. Many of our Patriarchs never sat in Alexandria.” The head and body of Saint Mark, separated, differentially indexed various forces of empire then operating in Egypt: the head was stolen by a Muslim sailor and returned to Coptic Pope Benjamin I by military commander Amr Ibn Al-‘As. The body was left behind with the Melkites and was later taken by the Venetian merchants Bonus and Rusticus. In a strange twist of fate, the Venetian sailors had stolen from “Rome,” their own imperial church based in Alexandria.

Through bodily rituals of investiture (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Thompson, Raymond and Adamson1991), the “Popes of Alexandria” (Coptic Orthodox) secured a continuous lineage of apostolic succession through the head of Saint Mark. Until the mid-eighteenth century newly appointed Patriarchs transferred powers of church headship by kneeling and bowing before the head, then embracing and kissing it. On 24 June 1968, Pope Cyril VI met the body of Saint Mark at Cairo airport, and transported the reliquary to a car and then to the old Patriarchate in Azbakiya, and finally, days later, to the new Patriarchate in al-‘Abbasiyya. Papal legitimacy turns upon shifting grounds of mobility and stasis among saintly images and consecrated bodies traveling in relative positioning to each other. From one papal seat to another, Coptic Patriarchs have long shifted locations of authority, under varying political conditions, by jointly moving with Saint Mark's relics: Pokalia, the site of burial; al-Mu'allaqa, a site of hiding; and finally al-‘Abbasiyya, a site of expansion. With Saint Mark's body returned to its rightful owner, a territorial politics of church dispossession converged with a spatial politics of bodily integration. Through the image of the broken martyr restored, head and body united on Egyptian land. The holy return prefigured the fulfillment of divine justice and the integrity of the church body in heavenly resurrection.

Relics, the means of “ecclesiastical colonialism” (Davis Reference Davis2004), also introduce material limits on imperial expansion. Portable and partible, they make dislocation and reproduction relatively easy. When the Venetians stole Saint Mark's body in 827, they did so in order to secure regional autonomy from both the Carolingian west and the Byzantine east. By displacing Saint Theodore as the patron saint of Aquileia, Saint Mark became identified as the “specifically Italian apostle” (Demus Reference Demus1988, my italics). According to Geary's narration of Translatio Sancti Marci, the two custodians of the church of Alexandria were “properly shocked by this suggestion and reminded the Venetians that Mark had been the first apostle to Alexandria.” Theft, as “translation” of a particular kind, enables an ambiguous legitimacy to emerge through routes of trade instead of church consecration. Through the Venetian theft the aim of independence from the imperial stronghold was definitively realized.

The Copts were less successful. Their request for a full “return” of Saint Mark's relics was only partially fulfilled since Cardinal Urbani retained one portion and the Vatican gifted another to the Greek Orthodox in Cairo in June 1968. Many Coptic Orthodox Christians, situated as they are in relation to various bodies of domination inscribed upon territory and holy images, remain wary of associations with other churches, particularly those identified as foreign and Western. Being “Coptic Christian” in the world is thus not so much a “religious” identity, in the sense of reliable allegiance with other “Christianities,” as it is an identity that articulates historical shifts in the relationship between the Coptic Orthodox Church and imperial rule.Footnote 33 Aspirations for world “catholicity,” pursued in various forms via imaginary links across churches and imperial territories, can weaken the very ties they create.

CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS

In early January of 2011, a little over a month after it had faced near destruction, I visited a partially constructed church building in al-‘Omraniyya on the southwestern outskirts of Giza. Because the church lacked a government permit, the Giza police arrived on the scene with bulldozers prepared to destroy the large edifice and clash with rioters. Amid the despair and mounting anger of Copts, this turn of events provided further evidence for the narrative of a Christian minority persecuted by a Muslim-majority society and a repressive state regime. As we walked along the shoulder of the Ring Road, a resident guided me toward a better vantage point from which to view the unfinished building, which stood only yards away from a newly built mosque. In a gentle, matter-of-fact tone she explained how it is easy to obtain permits for mosques, but difficult for churches. This led me to remember a similar conversation and scene from four years before. In March of 2007, driving through al-Warraq on Nile Street on my way to the Wadi Natroun monasteries in the Delta, I first noticed the Church of the Virgin and Archangel Michael. My traveling companions pointed out, as proof of discrimination, how the minarets of the neighboring al-Hoda Mosque towered above the church steeples. Little did I know that only two years later the Virgin of al-Warraq would bring me back to these landscapes of church visibility to consider the political potential introduced by saintly images and the creation of church territory.

I began this essay with Marian apparitions and the politics of Coptic belonging, and I want to close by providing some of the context in which I am now considering the broader stakes of church territory. Coptic churches have gained political importance in post-revolution Egypt as shrines of minoritarian vulnerability and religious rights. Church burnings, and petitions for church buildings, have brought Coptic Christian international visibility, much to the dismay of a number of frustrated activists. As one Coptic intellectual said to me: “What will Copts gain with one more church? How does this change anything for a future Egypt?” The emphasis on places of worship as religious sites of competition on a national scale is hardly unique to Egypt. For example, Peter van der Veer, writing about the politics of the Ayodhya temple-mosque controversy in northern India, another context of majority-minority violence, describes sacred sites as foci of “one's identity in relation to the other world and to the community of believers” (Reference Van der Veer1994). As the case of al-Warraq demonstrates, Marian apparitions intercede in topographies of Muslim-Christian rivalry and shore up the political visibility of a “beleaguered minority” against a dominant majority in relation to the nation-state. As apparitions illuminate and expand church territories, we might interpret them as symbols of Coptic Christian minoritarian assertions and communal livelihood.

Given the widespread sectarian tensions in Egypt, how might one understand churches as more than places of Christian exclusivity, or strongholds of Coptic community recognition and survival? The term “religious minority” has not always regulated the politics of Coptic inclusion into the national whole. Conventional wisdom begins by specifying the horizons of political belonging: where are Copts situated in Egypt, within pan-Arabism, and in World Christianity? The story of Copts as an integral part of the national “Egyptian fabric”—both as secular co-citizens with Muslims, and as a “national” Christianity against foreign ones—is an old and often told one. Reminiscent of a hallmark slogan of the 1919 revolution, “Religion is for God and the nation is for all,” many secularists in the wake of the 25 January revolution have called for prioritizing national allegiance over religious affiliations. From this perspective, in which religious and national belonging are categorically at odds, battles for the expansion of church spaces undermine the greater necessity of finding national unity. In more substantive terms, however, to understand what form of Egyptian “nation” grounds Coptic integration will require a search for the detailed parameters of inclusion and exclusion that demarcate national belonging.

In this study of how Marian apparitions clarify various stakes of church visibility and growth I have tried to rethink the spatial-imaginary terms of Coptic belonging with respect to national and Christian scales of territorial expansion. The examples of al-Warraq in 2009 and Zeitoun in 1968 show that Marian apparitions occur in different contexts and can produce varying effects. Signaling everything from Fatimid-era persecution, to the tragedy of the 1967 war, to the scandals of Venetian trade, they index memories of divine intercession that cast and recast scenes of Coptic marginalization and integration. As I have sought to track by way of saintly images in circulation, the imagined perimeter of the Egyptian nation runs alongside a territorial geopolitics of displacement and occupation, through the making of state boundaries (the Arab-Israeli war of 1967) and imperial Christendom (the Venetian theft of 827). In doing so, the nation-state (Egypt's Copts) and national Christendom (Coptic Orthodox Christianity) are visible as contiguous bodies of power, communicable through divine images that reveal interwoven histories of injustice and ambiguous ties.

The connections made are unstable and shift over time. Here, to trace the modes of saintly mediation—of the Virgin in concert with Saint Mark—is to engage the politics of a religious tradition (Asad Reference Asad1986; Reference Asad2003; Mahmood Reference Mahmood2005; Hirschkind Reference Hirschkind2006) in order to understand a political imagination that transcends the primacy of religious identities at the service of nation-states. “Religion” is not necessarily a term of fundamental exclusivity, subordinated to the inclusionary promises of “nation.” Beyond the bond between minoritarian affiliation and nationalist ideology, the intercessory tradition offers insights into the ways in which apparitions of the Virgin and relics of Saint Mark have historically transected multiple social and political orders—of nation-states, empires, and Christendoms. In doing so, holy images serve as vehicles of national and church mediation that variously situate saintly territories of Coptic belonging. Reading saintly intercession as a “religious” mark of Christian as opposed to Muslim identity is to misperceive the ways in which it takes place under variable conditions of belonging and exclusion that upend sectarian affiliations. Apparitions and relics, as media of expanding power of divine origins, and with their own exclusionary risks, can constrain competing forms of polity-making.