malouet in the guianas

Throughout the eighteenth century, Guiana had been a harsh testing ground for French colonialism. European imperial projections for the region had been marred from the outset by several failures, beginning with Walter Raleigh’s far-fetched plan to emulate the Spanish Empire through the conquest and exploitation of an “El Dorado” supposedly located somewhere between the mouths of the Amazon and the Orinoco (Pagden Reference Pagden and Canny1998: 33–35; Elliott Reference Elliott2005: 24). No less fanciful but far more tragic was the colonization plan the French set into motion in the Kourou region on the north coast of Cayenne, after the Seven Years War. In 1763, the metropolitan authorities, seeking to compensate for the loss of Canada but also stimulated by notable gens de lettres like Turgot (who defended the viability of European labor in the tropical world), promoted the recruitment of a large number of French and German families from Alsace and the Rhineland. The scale of the venture was vast. Between 1763 and 1764, around fourteen thousand Europeans left France for Kourou. Within a few months, though, two-thirds of them were dead from a typhoid epidemic brought on their own ships, widespread famine, and mismanagement of the entire enterprise (Rothschild Reference Rothschild2006).

The French enlightened statesmen would soon be back in action, trying to implement a plan devised by the German-born Baron Bessner, who had been active in recruiting Rhine and Alsatian settlers. Designed in 1768, this new project at least did not have the brutal human costs of the Kourou adventure. Bessner believed that, through the Jesuits living in the French colony, it would be possible to attract the some hundred thousand Indians scattered throughout the interior of Guiana to new colonial enterprises and thereby recreate the past model of the Paraguayan missions. Bessner also envisaged the recruitment of the Suriname maroon communities that, after 1762, had signed peace treaties with Dutch authorities. He thought he could count on up to twenty thousand former slaves from the neighboring colony to achieve his plan to boost French Guiana’s economy with free laborers (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1952; Duchet Reference Duchet and Arámburo1971: 117; Ghachem Reference Ghachem2012: 145–46).

By the end of 1775, Pierre-Victor Malouet was appointed by Antoine-Gabriel de Sartine, Secretary of State of the Navy, to serve as its commissioner in Guiana, charged with verifying the viability of Bessner’s overall plan, especially the hiring of Surinamese maroons. Born in France in 1740, Malouet had earned a law degree from the University of Paris. Between 1767 and 1773, he served in the French Navy in the opulent colony of Saint-Domingue, where he joined the thriving sugar planter class after marrying the daughter of a local planter (Bouscayrol Reference Bouscayrol, Ehrard and Morineau1989; Perrichet Reference Perrichet, Ehrard and Morineau1989). Malouet was part of a circle of “philosopher-administrators,” to which Bessner himself belonged, who had been promoting a broad redesign of the French colonial administration after the defeat in the Seven Years War. Hence the mission given to him by Sartine (Duchet Reference Duchet and Arámburo1971: 118; Tarrade Reference Tarrade1963; Reference Tarrade, Ehrard and Morineau1989). A few months after arriving in Cayenne, Malouet was able to visit Suriname, where he stayed for thirty-six days (Robo Reference Robo, Ehrard and Morineau1989). While there, he realized how unrealistic Bessner’s plan was, starting with the fact that all the information circulating in France through the influential pens of the enlightened gens de lettres, like Raynal, was distant from the truth. “Everything I have read about Suriname’s slave-maroons,” he wrote, “is absolutely false” (Reference Malouet1802: v. 2, 67). The supposed twenty thousand maroons that had made peace with the Dutch were actually only three thousand, and they showed no intention of leaving the lands they had conquered. The Boni, still at war with the Dutch, were too few to boost any economic plan, and their transfer to French Guiana would pose a serious risk to the local relations between the two European, overseas empires (ibid.: v. 3, 37).

Nevertheless, Malouet said, Suriname did have something to offer French Guiana. The geo-ecological conditions of the two colonies, with their very specific obstacles to the creation and expansion of export agriculture, were strictly the same. Indeed, since 1766 some French authorities had been thinking of replicating in Guiana the model of lowland cultivation employed in Suriname (Tarrade Reference Tarrade1972: v. 1, 334). Such was the perspective that informed Malouet’s voyage: to set aside Bessner’s unfounded plan and carefully learn the secrets of Suriname’s slave agriculture. Only in this way could they overcome the gap that separated, within the French Empire, Saint-Domingue—the most prosperous plantation colony in the Americas—from Guiana, “a badly constituted, useless, state-burdensome colony…, wild and miserable” (Reference Malouet1802: v. 2, 43, 368). For Malouet, the trip’s biggest achievement was a seemingly modest initiative to hire the Swiss hydraulic engineer Jean Samuel Guisan (ibid. 204–5). Guisan, who had extensive experience in building and managing plantations in Suriname, accompanied Malouet back to French Guiana, where he wrote and published an important French agronomic manual that synthesized all the agronomic knowledge of Suriname’s slave plantation economy (Guisan Reference Guisan1825[1788]).

Malouet went to a troubled Suriname between August and September of 1777. This was the final moment of the so-called Boni War, a long campaign against the eastern maroon groups of the colony, near the French Guiana border. Political and personal disagreements on how to wage the war led to tensions between the colony’s Governor Jean Nepveu and the military commander of the Boni campaign, Colonel Fourgeoud. The costs of war were also becoming prohibitive to the colonial budget (Groot Reference Groot1975: 43; Malouet Reference Malouet1802: v. 3). This was not the only economic problem registered by Malouet: he was amazed to note the sheer burden of Suriname’s planters’ debts under metropolitan merchants and financiers. According to his calculations, only 5 percent of the planters owed nothing to the Dutch capitalists; 25 percent owed one-quarter to one-third the value of their total assets; 37 percent owed half; and the remaining third owed three-quarters or more (Reference Malouet1802: v. 3, 87).

The challenge was how to combine this assessment of the poor financial health of the plantation investments in Suriname with the fact that the colony was being taken as a model for boosting French Guiana. For Malouet, this was a conjunctural and circumscribed problem. He saw no visible signs in the plantation landscape along the rivers and creeks that the colony was actually in crisis. Instead, he recorded in vivid pages all his admiration for the excellence of Suriname’s agronomic techniques, which had conquered for plantation agriculture the inhospitable lowlands and marshlands of the region (which were subject to constant strong tides). As an absentee Saint-Domingue planter, he also did not fail to note the contrast between the ease of cultivation in the French colony and the enormous hydraulic engineering work required for agricultural production in Suriname. According to him, “The colonist of Saint-Domingue … gets rich on fertile soil without being held to other work than plowing; but the colonists of Suriname succeeded in renewing the miracle of creation dividing the elements merged together; separating the silty earth from the water which holds it almost in solution; raising huge buildings on a marsh, and building them on solid foundations: enormous works added to those of the [agri]culture” (ibid.: 93). The comparison between “the lands of Suriname with those of Saint-Domingue” highlighted another important contrast: sugar lands in Saint-Domingue were more productive, but Suriname had larger coffee yields “because we use only our inferior lands, those of the hills; and the Dutch on the contrary use their best land there” (ibid.: v. 3, 99–100).Footnote 1 And for both Surinamese sugar and coffee, he concluded, erosion was not a problem.

The debt crisis was hitting mainly the coffee sector, whose planters, excited by the good prices of the 1760s, had become heavily indebted. The downturn in coffee prices in 1770, combined with unnecessary spending (e.g., to construct luxurious villas), led to a crisis. If the debt issue was not solved, Malouet said, the prosperity of Suriname was endangered, as evidenced by the fact that the transatlantic slave trade had been practically interrupted in 1777. Still, the solution to the problem was simple: it would be enough if the coffee market showed signs of recovery. Indeed, “It would be necessary for the capitalists to diminish the interest of the advances they made, and instead of six percent to require only half of that. But we do not dare to flatter ourselves with this condescension on their part: the rise in the price of coffee is the surest way to remove the inhabitant from the embarrassment in which he managed to put himself into” (Reference Malouet1802: v. 3, 135). Suriname, therefore, remained as a positive example to be followed in French Guiana.

coffee, slavery, and the world-economy

Malouet misread the environmental impositions on the two coffee colonies. I will argue that what he considered Suriname’s advantage—the complex hydraulic engineering that had turned swamps into fertile land for coffee production—in fact killed its competitiveness against the spatial economy of coffee growing in Saint-Domingue. Nonetheless, Malouet’s readings of slave resistance in Suriname played an important role in the reorganization of French policy toward slavery issue in the 1780s.

Whatever the shortcomings of Malouet’s coeval evaluation, it is unfortunate that twentieth-century historians never followed up on his comparative exercise. A brief note will make the point. The best study on the slave coffee plantation economy in Saint-Domingue is still Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s article published almost forty years ago. Through a critical engagement with the world-system perspective and an original proposal on the reciprocal conditioning between global forces and local responses, Trouillot put forward a sharp and in many ways surpassing analysis of the dynamics of slavery in the Saint-Domingue coffee economy. When addressing the takeoff of the colony, he mentioned Suriname and pointed out the Dutch pioneering role in large-scale coffee cultivation as well as the “series of unexpected problems in the 1760’s and 70’s” that this rival colony had encountered (Reference Trouillot1982: 342). That said, Trouillot’s analytical framework did not address the relation between what was happening in the two colonies. We find a similar lacuna in the most complete study of Suriname’s plantation system, Alex van Stipriaan’s outstanding Reference Stipriaan1993 book (which is the basis of my own analysis of that colony’s coffee culture). Stipriaan drew specific comparisons between the economic and demographic performances of various European possessions in the West Indies, including the coffee sectors of Suriname and Saint-Domingue. Yet, he (ibid.: 132–34) only points out the contrast between the crisis that struck Suriname and the rapid growth of Saint Domingue after the 1770s, without noticing the strict relationship between the one and the other. The analytical procedure of isolating imperial units has left historiographies dealing with both coffee economies unable to grasp the greater historical forces that shaped each through their mutual relations as parts of the same world economy.

The comparative study that I propose here is part of a larger project on the global history of coffee and slavery. To better ground the present analysis, let me briefly nominate the four global coffee complexes that overlapped in the longue durée: (1) the economy built by the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the sixteenth century, connecting peasant farmers in Yemen to urban consumers in the eastern Mediterranean; (2) the slave economy built in the West Indies by the metropolitan powers of northwestern Europe in order to supply their urban consumers, beginning in the first half of the eighteenth century; (3) the slave economy of the Paraíba Valley (in the Empire of Brazil), which emerged in the 1810s–1820s, followed by Dutch Java and British Ceylon, with all three articulated to urban consumers but also to the growing proletariat in the North Atlantic; and (4) the new plantation economy of western São Paulo (again, in Brazil) based on the large-scale mobilization of European immigrant labor at the end of the nineteenth century; other Latin American producers follow far behind, and the United States and the German-speaking countries were the final destination of its product. In each one of these four coffee global complexes we can observe specific combinations of land, labor, capital, and political power (Clarence-Smith and Topik Reference Clarence-Smith and Topik2003). As the basic social relation that shaped the second and third coffee complexes, slavery was a key institution in the making of the global coffee economy. However, this was an institution with its own history, and its legacies have also shaped the fourth complex in different but crucial ways.Footnote 2

That slavery was not always the same also draws our attention to the historicity of the plantation. The seemingly paradoxical combinations of this form of social and economic organization of exploitation in the tropics—in particular the articulation with metropolitan markets and the large-scale employment of coerced labor on large and heavily capitalized agricultural units—have led social scientists since the first half of the twentieth century to debate the nature of the plantation. Was it a full manifestation of the modern capitalist world, a pre-capitalist form associated with the latifundia of premodern Europe, or a specific product of the colonization of the New World? After the 1950s, three perspectives came to dominate the subject. The first, based on various theoretical contributions, tried to construct a typological model by abstracting particular geographic and historical features in order to identify characteristics (institutions, cultural standards) common to all plantations regardless of time, space, and modalities of labor. The second sought to understand the theme within the mechanics of the modes of production. The third perspective saw the plantation, whether employing slave labor or not, as a typical form of production of the periphery of the modern capitalist world economy. Notwithstanding their undeniable merits, each of these approaches has produced only partial and limited versions of the phenomenon, which have often led to ahistorical abstractions.Footnote 3

Moving away from these three perspectives, I will try to address the making and the transformation of the coffee plantation as a historical process mediated by the “metahistorical space conditions” and the “historical spaces of human organization” (Koselleck Reference Koselleck and Hediger2014: 73–89). Such a perspective allows the integration of factors of ecology, capital, technology, and labor, as well as social relations and political structures, into a unified analytical framework. The plantation thus appears as a set of relationships that operate on multiple temporal and spatial scales—from long to short duration, and from the world-economic arena to the national, regional, and local levels. Within such a framework we can reconstruct the concrete and specific conditions of the agency of social agents and their consequences. Space and time, after all, are inherent to any human action. Social relations necessarily have a spatial dimension, while spaces constrict and enable human agency. The proposed approach looks at the active processes that shaped the environments of coffee production units from historically determined social relations and, at the same time, the means by which these environments determined the social relations that made the exploitation of these units possible (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith1991: 68–168; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1996: 1–12; Tomich et al. Reference Tomich, de Bivar Marquese, Monzote and Fornias2021).

The coffee plantation constitutes the unit of observation, but not the unit of analysis. In other words, I follow the world-systems perspective to account for the articulations of the locus of coffee production with the global circuits of circulation and consumption of the product, examining the multiple constellations of land, labor, capital, and political power that were present in the formation and transformation of the world coffee market as an essential, constituent part of the capitalist world-economy (Hopkins Reference Hopkins, Hopkins and Wallerstein1982; Talbot Reference Talbot2011). In this sense, the “commodity frontier” category, as proposed by Jason W. Moore (Reference Moore2000), helps us understand the problem of the spatial mobility of coffee cultivation. The emphasis on commodity frontiers sheds light on the structural tendency of historical capitalism to degrade the environment, even before the Industrial Revolution. In investigating the means by which the production and distribution of specific commodities—primary commodities in particular—have structured geographical spaces on the margins of the world-system in such a way as to require further expansion, Moore makes the connections between ecological transformation and the expansive character of capital more explicit. The constant incorporation of new frontiers into the commodity chains of capital has been driven since the sixteenth century by the maximum appropriation of natural resources. In this sense, capitalism as a world historical system has been reproduced from its very beginnings by the constant production of new commodity frontiers and, in turn, environmental degradation.

How can this be useful for the study of the coffee complex in the longue durée? The multiple commodity frontiers of coffee, all of them involving some sort of compulsory labor, allow us to follow not only the expansion of capital but also its discontinuities over time and space. The continuous formation of new frontiers of the coffee commodity has meant profound transformations of land and labor on a global scale. Over-appropriation and simplification of ecosystems, necessarily implying over-exploitation and degradation of labor, have resulted in a steady decline in the productivity and profitability of coffee enterprises. The commodification of land and labor in the American and Asian landscapes dictated by the logic of capital thus involved the continual expansion of the boundaries of the coffee commodity.

In this article my focus is on the second global coffee complex, the West Indies slave economy, in which the Dutch colony of Suriname and the French colony of Saint-Domingue occupied a crucial place. Table 1 shows their respective positions in the global coffee exports in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 4

Table 1. World coffee exports estimates in metric tons, 1755–1790

Sources: Trouillot Reference Trouillot1982: 337 (Saint-Domingue, 1755); Tarrade Reference Tarrade1972: v. 1, 413 (Saint-Domingue, 1765, 1771–1775); v. 2, 747 (Saint-Domingue, 1776–1790); Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993: 430–31 (Suriname, 1755–1790); Samper and Fernando Reference Samper, Fernando, Clarence-Smith and Topik2003 (world total).

In the mid-eighteenth century the world’s leading coffee producer was Yemen, on the Red Sea, with a peasant-based economy capable of supplying about 12,000 tons per year (Tuchscherer Reference Tuchscherer, Clarence-Smith and Topik2003: 55). In fact, for nearly two hundred years (ca. 1550–1720) this region, where commercial coffee production was actually created, monopolized the world supply. Until the mid-seventeenth century, most buyers were in the urban markets of the Ottoman Empire, with its lush coffeehouses (Hattox Reference Hattox1985). Thereafter, in emulation of the Ottoman model, a solid culture of public cafes appeared in northwestern Europe (McCabe Reference McCabe2008; Cowan Reference Cowan2005), and by the end of the century there was an established, albeit fairly modest consumer market in Europe. The bottleneck for its growth was on the supply side—the Yemeni monopoly. This leads us to a price problem that emerged in Yemen’s markets as the eighteenth century began. In the midst of the War of Spanish Succession (1703–1713), the Yemeni imam allowed English, French, and Dutch merchant companies to settle trading posts in Moka. With the return to peace, the prices paid by the European companies rose dramatically due to strong competition among themselves and with the Cairo merchants who carried the product to the Ottoman Empire. Transactions in Moka, moreover, could only be paid in silver. Disputes between French, English, and Dutch companies led to high prices in Moka between 1713 and 1725, but prices in European markets (London, Amsterdam, Marseille) did not follow them (Genç Reference Genç and Tuchscherer2001: 171; Glamann Reference Glamann1958: 196; Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri1978: 362–64).

The problem of the Yemeni was the decisive impetus for the construction of the Dutch and French coffee plantation systems, which started relatively quickly. Between the 1720s and 1740s, the coffee bush was successfully acclimated in places as diverse as the islands of Java and Bourbon (now Réunion) in the Indian Ocean and in Suriname, Martinique, and Saint-Domingue in the West Indies. The slave plantation model was immediately adopted in all of them except Java, in a fundamental break with the previous peasant production patterns of Yemen (Talbot Reference Talbot2011). The structure of the overall supply was also rapidly transformed. In a few decades, the slave plantation colonies run by European powers came to dominate more than half of the world’s coffee production. At the outbreak of the Seven Years War (1755), Suriname and Saint-Domingue each accounted for about 10 percent of the world supply. Over the next ten years, both colonies expanded, together accounting for about 35 percent of the supply. After that moment, there was a decisive bifurcation: while Suriname stagnated (the volume level offered in 1765 remained roughly the same until the early 1790s), Saint-Domingue experienced a remarkable leap forward. Its coffee production increased sixfold in the twenty-five years before the slave revolution, enabling it to account for half of the world’s supply. As table 1 shows, the turning point occurred in the five years after 1771, when Saint-Domingue alone accounted for around 60 percent of the increase in the global coffee supply.

These trajectories may surprise, especially if we consider the broader institutional conditions of both plantation economies. When the Dutch West Indies Company’s monopolies ended in 1738, Suriname planters had an ample supply of enslaved Africans, easy access to metropolitan capital, and technical knowledge from the Netherlands that allowed them to turn the tidewater zones of the Guianas into highly productive fields for tropical crops based on the drainage method of the polders. The financial invention of negotiatie funds (explained below) gave them the opportunity to channel this capital to the agricultural export sector of the colony, which was increasingly dominated by coffee production. At the peak of the transatlantic slave trade to the colony, between 1750 and 1770, coffee investments—evaluated in terms of acreage and enslaved Africans per unit—exceeded sugar investments (Postma Reference Postma1990: 212; Oostindie and van Stipriaan Reference Oostindie, van Stipriaan and Palmié1995; Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993; Hoonhout Reference Hoonhout2012; Klooster and Oostindie Reference Klooster and Oostindie2018: 70). It was this opulence that attracted the attention of French authorities in the mid-1760s, leading to Malouet’s inspection trip in 1777.

His bet that the recovery in coffee prices would allow a quick exit from the economic crisis facing Suriname planters soon proved to be wrong. Coffee prices in Amsterdam began to recover on a strong upward trend exactly after 1777. The Suriname coffee economy, though, remained stagnant and was surpassed by Saint-Domingue. Given Suriname’s abundant land, labor, and capital, why did its coffee production lag behind in the 1770s, and why did Saint-Domingue’s grow? Was there a relationship between the two processes? What are the implications of this divergence for plantation slavery in these two colonies?

suriname

“It’s an enchanting glimpse of a belvedere in the Comwisne River,” Malouet enthusiastically wrote in 1777 (Reference Malouet1802: v. 3, 97). The sumptuousness of the plantation buildings, its boulevards planted with fruit trees parallel to the canals built with the advanced hydraulic knowledge of the Dutch, the lively beauty of the cane and coffee plantations, the perpetual movement of the river boats, the numerous slaves of the various plantations, everything reminded him of “the richest landscapes of Europe.”

Yet there was a brutal human cost to the production of this world that enchanted him. The enormous amount of manual labor required to construct this second nature resulted from Suriname’s specific geo-ecological conditions, which imposed their own mark on the exploitation of the region’s coffee plantations. The Guianas, from Cayenne to Demerara, can be roughly divided into two broader areas: the highlands and the coastal plain. Contrary to the previous indigenous pattern, agricultural export activities in the colonial period were concentrated in the coastal plain, a comparatively narrow strip of land between 30 and 100 kilometers wide. Due to the combined effects of river and sea deposits, these lowlands formed a marshy region with dense forest cover, very wet and subject to strong tides (Cardoso Reference Cardoso1984: 15–17). The system of land subdivision, concession, and privatization adopted by the Dutch colonial powers clearly reacted to environmental obstacles by ensuring that all future rural units had access to rivers and creeks, in order to simultaneously allow soil drainage (with the building of polders) and give them access to inland waterway transportation (Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993: 74–81).

These ecological conditions determined the elongated and rectangular shape of the plantations, all of which were perpendicular to the rivers and streams and parallel to each other. The general spatial organization of the colony, as well as its cognitive apprehension in cartographic representations, can be observed in several contemporary charts, such as the detail of a map (image 1) produced during the Suriname coffee boom (1758–1767).

Image 1. Detail of Landkaart van de Volkplantingen Suriname en Berbice (Map of the settlements in Surimane and Berbice), 1758–1767, 32 x 38.5 centimeters, Universiteit van Amsterdam, The Memory of the Netherlands Database (https://www.geheugenvannederland.nl/en/geheugen/view?coll=ngvn&identifier=SURI01%3AKAARTENZL-104-03-34).

We see in this map the network of plantations along the Suriname river, running south to north, with its affluents Para Kreek and Paulusm, and running west/southwest to east the Commewijn river (Malouet’s “Comwisne”), with its tributaries Kottika and Perika. The Suriname river channel was the first area explored for commercial agriculture, and sugar plantations began to be established there in the late seventeenth century (Postma Reference Postma1990: 174–84; Fatah-Black Reference Fatah-Black2015: 63–93). The plantations of the Commewijn and tributaries were established later, starting in the 1740s, and it was there that the coffee boom shown in table 1 took place (Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993: 47–50). The map also suggests that, in terms of their spatial distribution, there was no distinction between sugar and coffee plantation areas. Both occupied the same natural landscape and had to face the same environmental challenges. As Gert Oostindie and Alex van Stipriaan have pointed out, all the colonial agricultural exports depended on the polders: “Without this technology, the natural conditions of Suriname were not suitable for plantation agriculture; with it, the colony’s competitive powers were enviable” (Reference Stipriaan1995: 80). In this peculiar environment, the impositions of landscape management over labor management were brutal. This is indicated by the agronomic manual of Jean Samuel Guisan, the Swiss hydraulic engineer Malouet hired in 1777. Slashing and burning of the forest, a widespread practice in the tropics, was the first step. The greatest challenge followed: removing an enormous amount of land to build the dams to contain rivers and creeks. In contrast to tropical agriculture in dry areas, all rotten stumps and woods had to be removed from the fields to prevent seepage or breakage of the dams, which was a real risk due to the area’s strong tides (many plantations were below sea level) and heavy seasonal rains. Next came the opening of the longitudinal and perpendicular channels to drain the whole terrain; division of the regular plots for planting; construction of high paths between the plots to transport inputs and crops; and the building of a floodgate system to control all the water flow (Guisan Reference Guisan1825: 22–35). Alex van Stipriaan gives a detailed idea of the scale of these works by describing the Nooyt Gedagt plantation path network: built on a concession obtained in 1748, it was completed ten years later, with a central axis of 2.4 kilometers, two paths on the side dikes of 1.7 and 2 kilometers each, and twenty perpendicular paths totaling 6 kilometers in length (Reference Stipriaan1993: 84).

Even before the planted coffee trees reached full production, which takes about five years, Suriname’s slaves had to perform the difficult work of building the infrastructure that enabled proper agricultural operations. Many fled these severe conditions, and escapees formed the first maroon communities outside the plantation zone. This process predated the coffee boom, beginning when sugar plantations were still being built along the Suriname river in the late seventeenth century. As anthropologist Richard Price noted in his classic work on the Saramakas (one of the two maroon communities in the south of the map), “The heaviness of canal-building labor is cited as the specific motive for escape in the traditions of several Saramaka clans…. These widespread stories stand as collective witness to the perception by slaves that this particular form of supervised gang labor—moving tons of waterlogged clay with shovels—was the most backbreaking of the tasks they were called upon to accomplish” (Reference Price1983: 48).

In the early 1760s, after more than half a century of intermittent war with the maroons, the Dutch colonial authorities were forced to establish peace treaties with the Djuka, Saramakas, and Matawai. One reason was the need to stabilize the internal security of the Surinamese slave society at a time of great metropolitan investments in the formation of new coffee plantations on the Commewijn river. Inspired by the agreement that English authorities signed with Jamaican maroons in 1739, the Surinamese treaties included the mobilization of pacified communities to stop the creation of new maroon groups that might form in the future (Groot Reference Groot1985: 176). But such groups soon formed anyway. In 1765, just east of the Commewijn’s new coffee area, near the French Guiana border, a Djuka patrol captured maroons who were attacking local plantations (the maroon communities noted to the east of the map). These were the initial forays in the serious war against the Boni, a group of distinct maroon troops formed by runaways, mostly from the new coffee zone (Groot Reference Groot1975). These were the maroons, pacified or at war, that Bessner expected to attract into French Guiana in the early 1770s. Malouet witnessed the final moments of the first Boni war in 1777 (Hoogbergen Reference Hoogbergen1990: 105). The event was immortalized by Gabriel Stedman’s classic account (Reference Stedman1796), combined with William Blake’s moving engravings (with his own antislavery reading of it).

The environmental impositions expressed in the demand for dikes and canals also determined the scale of the labor force on the Surinamese coffee plantations. My research on the slave coffee economies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries found wide variation in slave ownership patterns across places like Jamaica, Cuba, and Brazil (Marquese Reference Marquese and Piqueras2009; for Martinique, see Hardy Reference Hardy2014). This is no surprise given that coffee production is viable on both small and large units. Contrary to what happened in these other New World slave zones, Suriname’s coffee plantations varied little in terms of their areas and labor forces. The construction and maintenance of dikes and canals required many slaves, with a rather low deviation between minimum and maximum numbers of workers per unit. In the 1770s, coffee plantations had around 158 slaves and were about 295 hectares in size, very similar to the human and spatial scales of sugar plantations (Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993: 104).

Such a profile gave to the coffee plantations a standardized feature, a recurring theme of the maps that represent the procedures of building a plantation or its divisions when in full operation. This is clear, for example, in the plan of the Adrichem plantation (image 2), located on the Matapica canal between the Commewijn and the sea. Founded in 1751, it was about 500 acres (202 hectares) in size and had 151 slaves when the map was drawn in 1775 (Voort Reference Voort1973: 288; Crespo Solana Reference Crespo Solana2006: 188). The map shows the strict geometrization of the space, produced by the vast network of paths that divided the plots and the regularity of their dimensions. The complex ecosystem that existed prior to land privatization had been extremely simplified. The astonishing human work that went into transforming a tropical marshland into a fully functioning plantation is visually obliterated by the color scheme that was used to distinguish the coffee fields, slave plots, worn-out land, pastures, and woodland reserves. These same colors help transmute market value into beauty. The geometric space of the plantation and its map, in short, constitutes the essence of the simultaneous exploitation of nature and laborers.

Image 2. Plattegrond der Plantage Adrichem (Plan of the Adrichem Plantation), 1775, 94.5 x 58 centimeters, Universiteit van Amsterdam, The Memory of the Netherlands Database (https://www.geheugenvannederland.nl/en/geheugen/view?coll=ngvn&identifier=SURI01%3AKAARTENZL-101-12-14).

The final result of the landscape management method employed in the coffee plantations of Suriname can also be observed in a beautiful watercolor, a bird’s-eye view of a pair of contiguous units (image 3). The arrangement of the forest reserves at the bottom of the painting, with the channels of the two plantations marking the vanishing point of the representation, remarkably affirms the discourse of the domestication of tropical nature by the force of European mercantile capital.

Image 3. Gezicht op de koffieplantage Leeverpoel in Suriname (View of the coffee plantation Leeverpoel in Suriname), 43 x 63 centimeters, Rijskmuseum, Amsterdam (https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-T-1959-119).

The modular pattern of Suriname’s slave coffee plantations was reinforced in the mid-eighteenth century by a major financial innovation. The construction of the sugar complex at the turn of that century had been funded by private merchants from the metropolis, who maintained current accounts with the Suriname planters through a commissioning system. Starting in the 1750s, a completely new credit system emerged as a result of the excess capital in the Netherlands, the opening of new areas for plantation agriculture in Suriname, and especially the favorable conjuncture for coffee prices. In this system, a merchant/financier in the Netherlands would set up a “business plan,” or “negotiatie,” a fund that provided fixed annual interest payments (of 5–6 percent) for those who invested in it in the form of bonds worth 1,000 guilders each. Once the fund had been created, the merchant entrepreneur who took the initiative would become its director. Then he would make this capital available to different planters in Suriname, who would offer their plantations as collateral. The advance had features of mortgage credit, but in reality “these negotiatie loans were more like financial securities. Each year a fixed amount of money was to be paid to the holder of the negotiatie bond, irrespective of the profits of loss of the plantation” (Hoonhout Reference Hoonhout2012: 11). As a security measure for investors, only five-eighths of the whole property value (stipulated by a supposedly independent appraiser) could be contracted for mortgage-lending purposes. The planter would cover the fixed annual interest and trade his product and ordinary imports only with the fund director. After ten years of contracting the original loan, he would have to start repaying the debt honoring 10 percent of its total amount annually, so that in twenty years bondholders would get back the full value of their investment (Voort Reference Voort1973: 91–100; Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1995).

In the decade following the Seven Years’ War, 240 negotiatie funds were set up for the whole of the Dutch and British Caribbean (Dutch capital never worried much about borders), half of which went to Suriname (Voort Reference Voort1973: 100–10; Crespo Solana Reference Crespo Solana2006: 146). It was this huge influx of capital that allowed the building of several new coffee plantations along the Commewijn river, its tributaries, and canals. The coffee economy leapt forward: between 1750 and 1775, its export value was three times higher than sugar (Souty Reference Souty1982: 212; Vries and van der Woude Reference Vries and Van Der Woude1995: 473). In the 1770s, around thirty-eight thousand slaves were working on Surinamese coffee plantations compared to seventeen thousand on its sugar counterparts (Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993: 311). Easy credit gave rise to a new group of coffee planters who had with no previous capital, management experience, or technical knowledge, but who drew on the know-how of managers and engineers already established in the colony to quickly build their properties (ibid.). Thus, the modular system of the Surinamese plantations reinforced and was reinforced by the negotiatie system. According to Fernand Braudel’s conceptualization, the third level of the modern economy, that of high capitalist finance, had come to intervene directly in the first level, the so-called “ground floor” of agricultural production (Reference Braudel and Telma Costa1996, v. 2; Talbot Reference Talbot2011).

In a few years, many coffee plantations had their assets artificially revalued upward to expand credit flows. Without major transformations in their spatial and human scales, coffee plantations in the first half of the 1770s were being valued almost two and a half times higher than twenty years earlier. However, the steady flow of mortgage credit over-capitalized the newly formed coffee plantations (Emmer Reference Emmer1996), even before they could demonstrate their effective yields—remember that new coffee trees take five years to reach full production. Local environmental conditions were taking their toll. The Dutch polder technique was exquisite but very costly: environmental demands for coffee production imposed heavy initial costs for the construction of dikes and canals, and later their maintenance. It was no coincidence that the most expensive factor of production in Suriname was land, not labor (see table 2).

Table 2. Relative value of the factors of production to the total capital of the Suriname coffee plantations, 1750–1779

Source: Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993: 125, table 22.

Between 1775 and 1779, when loans made after the Seven Years’ War began to expire with the obligation to annually repay 10 percent of them, the crisis struck. This was just when Malouet visited Suriname. According to him, by stimulating unnecessary sumptuous spending, easy credit played a large role in the crisis, but the real problem was the fall of coffee prices in the 1770s. Malouet did not wonder why they had fallen, nor did his prediction prove true: coffee prices began recovering exactly in 1777, but the Suriname coffee crisis became permanent. We must now turn to the other side of this history: the colony of Saint-Domingue, where Malouet was a coffee planter.

saint-domingue

In Amsterdam, the hub of tropical commodities in Europe, the coffee from the main French colony began to be separately valued from that of Moka, Java, and Suriname in 1756. Saint-Domingue slaveholders entered the global coffee market with a very differently productive plant. The economic geography of French Saint-Domingue was marked by an opposition between the plains, dominated by sugar plantations—the great plain to the north around Cap Français, the Cul-de-Sac region, Port-au-Prince as its harbor, and the minor plain of Les Cayes to the south—and the so-called mornes, the high, mountainous terrains in the backlands. The irregular geomorphology of the mornes, added to their high rainfall and more temperate climate, made them unsuitable for those who invested in sugar activity from the beginning of the eighteenth century, but in that century’s second half, these same lands became the coffee kingdom (Trouillot Reference Trouillot1982).

In 1789, coffee in Saint-Domingue was concentrated in four distinct regions. The first and most important, with the highest volume of production, was the so-called Massif du Nord, which ran from the border with Spanish Santo Domingo to the rich coffee parishes of Borgne, Plaisance, and Port-Margot.Footnote 5 This region’s main export harbor was Cap-Français. The next region was the Chaîne des Matheux, a newer area formed in the 1770s with larger and more capitalized plantations and served by the ports of Saint-Marc and Port-au-Prince.Footnote 6 Finally, two subregions in the colony’s southern peninsula were articulated by the ports of Jacmel and Jérémie, respectively. There the coffee units were smaller and had fewer slaves, and they often combined the cultivation of coffee with cotton and foodstuffs.Footnote 7

There was a stark contrast between Suriname and Saint-Domingue in terms of the land. In the Dutch colony, because of the spatial contiguity of sugar and coffee plantations in the lowlands and their common hydraulic techniques for land occupation, the relative price of the land in either activity was almost the same. Alex van Stipriaan’s detailed and conclusive quantitative study of Suriname (Reference Stipriaan1993) has no counterpart for Saint-Domingue. For this reason, my argument here can only approximate the problem. First, it is important to note Trouillot’s correct assessment (Reference Trouillot1982: 344–45) that the mornes’ lands were much cheaper than those in the sugar plains. A preliminary analysis of notarial records of the coffee parishes of Port-Margot, Plaisance, and Borgne, northern Saint-Domingue, indicates that between 1776 and 1791 the prices of virgin land for coffee cultivation ranged between 200 to 400 livres per carreau (the aerial unit employed in Saint-Domingue, equivalent to 1.13 hectares). When already planted for coffee production, this value increased from 500 to 700 livres. Land was more expensive in Dondon, the oldest and most valuable coffee parish in the north, with land already planted bringing as much as 2,000 livres per carreau in the 1780s. At that moment, when almost no virgin lands remained on the northern sugar plains, a carreau planted in cane was worth 4,500 livres.Footnote 8

In other words, differences between the relative values of the plain (sugar) and mountain (coffee) lands made the mornes more accessible to resource-poor investors, such as the free blacks and mulattos wishing to enter the ranks of slave-owning classes. According to Trouillot (Reference Trouillot1982: 354–58) and Stewart R. King (Reference King2001: 124), free blacks and mulattoes eventually dominated the Saint-Domingue coffee economy as the main planters. However, the notarial transactions of the northern part of the colony with which I have worked so far show something different, a point that is also highlighted in other studies (see Manuel Reference Manuel2005, Geggus Reference Geggus, Geggus and Fiering2009: 14, 20, and Garrigus Reference Garrigus, Geggus and Fiering2009: 50). Notwithstanding the presence of free blacks and mulattos in multiple transactions involving coffee activity in northern parishes (especially in the purchase and sale of land), the values of their transactions were much lower than those involving white planters. In any case, we can identify several strategies those would-be planters with little capital or credit employed to establish coffee plantations. Noteworthy was the practice of forming small or medium-sized coffee partnerships involving two investors who agreed to share, for a set period (usually nine years) and under the direct management of one of them, their slaves, land, and facilities already in their possession or to be acquired.

These notarial records of the northern coffee parishes of Saint-Domingue only cover the period after 1776, when metropolitan authorities established that copies (double drafts) of all notarial transactions made in Saint-Domingue should be sent to Versailles. In turn, the indispensable private documentation that historian Gabriel Debien collected and analyzed throughout his career, which includes the papers of large coffee plantations, broadly covers the same period as the double drafts of the notarial records, from the mid-1770s onward (Reference Debien1943; Reference Debien1945; Reference Debien1956; Reference Debien1978; see also Roussel Reference Rousssel2015). Hence the invaluable importance of the coffee manual published in 1768 by M. Brevet, secretary of the Port-au-Prince Chamber of Agriculture and a planter in Mirebalais.Footnote 9

In what is probably the first agronomic work devoted exclusively to coffee,Footnote 10 Brevet sought to synthesize the prevailing practices in the quarter-century prior, the formative period of Saint-Domingue’s coffee economy. His handbook clearly indicates the differences from Suriname practices. Brevet’s investment profile for building an ideal coffee plantation had a maximum of twenty slaves and around 15,000 coffee trees. Saint-Domingue coffee production was characterized by the absence of a modular pattern. Alongside properties such as the one designed by Brevet, French investors founded coffee plantations in the 1770s and 1780s that were equivalent to the spatial scale of Suriname’s large coffee plantations. The contemporary data of Moreau de Saint-Méry (Reference Moreau de Saint-Méry1798), as well as a study by David Geggus (Reference Geggus, Berlin and Morgan1993), clearly show the impossibility of establishing what would be the “typical” Saint-Domingue coffee plantation, since plantations with up to three hundred slaves and units with less than five slaves coexisted side by side.

The areas occupied by small, medium, and large properties were the same in the mornes. Thus, Brevet explained, Saint-Domingue’s coffee economy, and Martinique’s, were repeating Yemen’s pioneering experience of growing coffee only in the mountains. However, unlike practices in the highlands of the Red Sea area, cultivation in the Caribbean did not occur on terraces prepared along the contours of the mountains, since the costs in terms of slave labor would be prohibitive. The model was cautious investments, year by year, with no major capital stipend for land purchase and preparation: the largest planned investment would be the purchase of those few slaves. More important, though, was the landscape management, with steady, “managed” destruction of the forest resources. Planting a new coffee area in the mornes worked only on freshly cleared virgin land. Coffee trees would be aligned from the bottom to the top of the hills to make it easier to surveil slaves “and for the ease of weeding and picking” (“tant pour le coup-d’oeil, que pour la facilité des sarclaisons, & pour le cueillir”) (Brevet Reference Brevet1768: 22). The unavoidable erosion would imply twenty to twenty-five years of productive life for coffee fields. Virgin forest reserves were thus the mainstay of the future expansion of coffee production within the plantation.Footnote 11

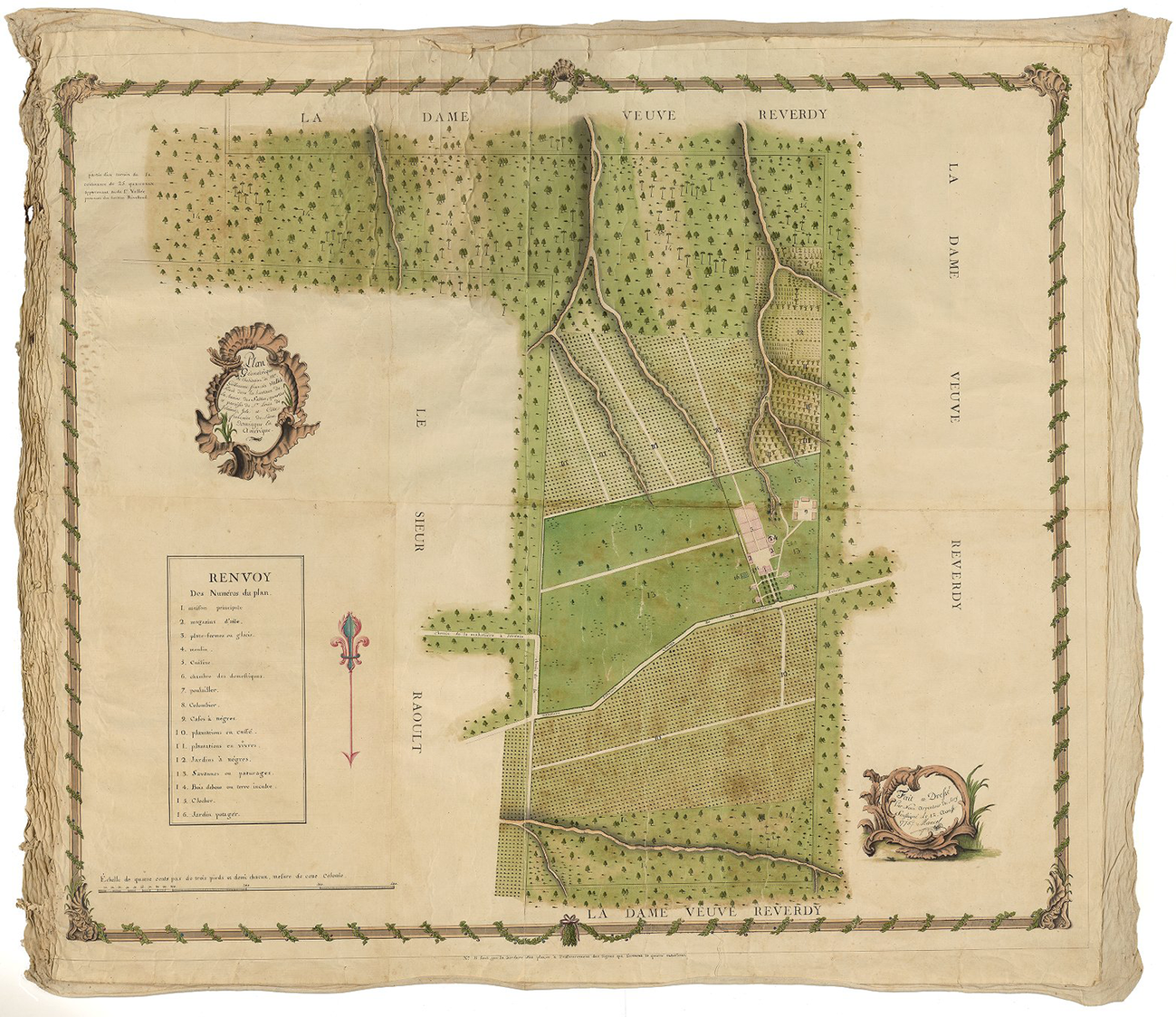

An excellent visual document of this pattern of coffee landscape management is a plan of a plantation located in the Fond Rouge, Jérémie, south of Saint-Domingue, drawn in 1775 (image 4). This large property map is framed with coffee beans and branches. Although the names of the neighbors (“widow Reverdy” to the north, south, and west; “mister Raoult” to the east) and property boundaries are carefully marked, this is not a cadastral map, but rather a deliberate representation of the owner’s wealth in all of its elements. It carefully, numerically, marks off the main buildings: 1. the villa in front of the main entrance at the Mahotière-Jérémie road, with an aligned small grove between both spaces; at the back of the villa are the facilities for coffee processing; 2. coffee barns; 3. drying platforms; 4. a circular mill; 9. slightly apart, five slave quarters arranged in a courtyard; then, 10. the coffee fields; 11. fields for foodstuffs; 12. the slaves’ garden plots; 13. the pastures surrounding the main buildings; and finally, 14. the forest reserves.

Image 4: Plan Géométrique de l’habitation de Mr. Guilleaume François Vallée (Plan of Guilleaume François Vallée plantation), 1775, John Carter Brown Library, 123 x 140 centimeters (https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/JCBMAPS~1~1~6414~115902724:Plan-g%C3%A9ometrique-de-l-habitation-de).

With a closer look we can understand the topography of this plantation’s terrain and its landscape history. The Mahotière-Jérémie road, which crosses the estate, runs through a hillside, and the main buildings are located one step above the road. Therefore, the northern and southern coffee fields, on both sides of the public road, were on sloping ground, as was the practice throughout the colony (another proof of this topography is in the three southern ravines down the hill, and another on the northern fields, in the plantation’s lower grounds). The sequence of agrarian transformation described by Brevet (Reference Brevet1768) would begin with the conversion of cleared forests to coffee plantations that, after twenty to twenty-five years of production, would be abandoned. This is what the map suggests: new coffee plantations were prepared by clearing the forest up the hill; the virgin forest belts to the north and, above all, to the south of the property constituted a reserve for future plantations. Slave plots and foodstuff fields occupied a marginal place in a ravine-broken zone on the property’s southwest border.

Apart from the map, we have no information about the general condition of this property in 1775. A rough and tentative calculation using the map scale gives us 68 carreaux of total area; the forest belt to the south seems to contain at least 30 carreaux; it appears a quarter of the terrain was planted with coffee, which would mean almost sixty thousand coffee trees (a carreau usually contained 3,500 trees). Fortunately, we have an inventory of this plantation made sixteen years later, in June 1791, when its total value was estimated at 304,800 livres. By then it had 71 carreaux, fifty-nine slaves (twenty-five men, fourteen women, twelve boys, and eight girls), eighty thousand coffee trees in production, and twelve thousand additional trees that had been planted the year before. Here we can see the agrarian system in continuous motion and the rapid depletion of natural resources. The forest reserves had been greatly reduced across the sixteen years in order to keep the coffee production moving forward: the 1791 inventory counted 50 percent more coffee trees than would have been there in 1775, but only 6 carreaux in virgin forests remained.Footnote 12

To conclude the comparison between production in Suriname and Saint-Domingue, let me briefly examine the values of a coffee plantation complex owned by a French nobleman who was also a sugar planter. Guy le Gentil, marquis of Paroy in 1754, inherited from his mother—just when he was buying his title—two sugar plantations in Limonade, on Saint-Domingue’s northern plain. The scale of operation of these sugar plantations increased considerably over the next two decades: in 1755 they had 253 slaves; by 1774 they had 398. In the latter year, Paroy’s wealth took an additional leap, again through family relationships: he inherited from his stepbrother four coffee plantations (La Grande Place du Moka, La Petite Place du Moka, Les Ecrévisses, Bellevue des Monts), quartier de La Grande-Rivière-du-Nord. With a total value of around 648,000 livres, they encompassed three hundred slaves, 549 carreaux, and 430,000 coffee trees. The spatial and human dimensions of these plantations were comparatively uniform, containing half of the slaves per unit, and half the area, of a medium-profile Suriname coffee plantation at the time. The figures in table 3, read through the data in table 2, indicate a crucial reversal: in the Saint-Domingue coffee economy, land was cheap while slaves were the most expensive factor of production. This finding is buttressed by a more specific comparison between La Grande Place du Moka plantation and the Bleyenhoop plantation (table 4), whose 1773 accounts were carefully examined by Alex van Stipriaan (Reference Stipriaan1995).Footnote 13

Table 3. Relative value of the factors of production to the total capital of the four habitations caféières belonging to the marquis de Paroy, Saint-Domingue, 1774

Source: Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence, FP 164/3.

Table 4. Land and labor prices in coffee plantations, 1773–1774 (in guilders)

Sources: Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence, FP 164/3; and Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1995.

Van Stipriaan (Reference Stipriaan1993: 133) also estimated the average coffee production per slave in both colonies in 1789–1790. The numbers are remarkably similar: 230 kilograms per slave in Saint-Domingue, and 219 kilograms in Suriname, which is no surprise since the productivity of coffee bushes, the proportion of trees allocated to each field slave, and the daily harvesting task during crop seasons were very similar in both colonies (Guisan Reference Guisan1825: 130–31; Brevet Reference Brevet1768: 54). Malouet was wrong to consider Suriname’s coffee lands more productive than those of Saint-Domingue. The relative costs of production factors, articulated through specific spatial economies, determined the overall performance of the coffee economy in each colony.

the coffee crisis of the 1770s and its distinctive outcomes

The difference between relative costs could have been irrelevant if the Suriname and Saint-Domingue coffee markets were not integrated. The British case clarifies this point: because of its Navigation Acts and corresponding tariff policies, the British sugar market became closed to mainland competitors, which allowed British Caribbean planters to maintain the viability of their business throughout the long eighteenth century even with higher production costs (Ryden Reference Ryden2009). This is not the case with the coffee markets. From its very beginning at the turn of that century, the commodity chain of the second global coffee economy was determined by freer competition between the different coffee-producing zones of the European colonies. This was due largely to the spatial concentration of consumers within northern Europe’s urban centers. In terms of per capita consumption, the Dutch market was the largest, since it was part of the most urbanized European economy from the sixteenth century (Vries Reference Vries2008: 152–61; de Vries and van der Woude Reference Vries and Van Der Woude1995: 57–71). Yet Dutch colonial coffee production proved unable to fully meet metropolitan demand. Between 1750 and 1790, Suriname coffee supplied only half of the Dutch consumer market, and the rest had to be imported from other colonial zones (Voort Reference Voort1973: 90; van Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1993: 25; Klooster and Oostindie Reference Klooster and Oostindie2018: table 16, 94). Moreover, Amsterdam was one of the two gateway ports for the growing consumption of coffee in the Baltic and German markets, Hamburg being the other (Combrink Reference Combrink2021).

The French consumer market for colonial products was fairly restricted before the nineteenth century, and for this reason France had to rely on re-exporting its tropical commodities from the beginning of its overseas colonization. Historically linked to northern European ports through its wine exports, in the early eighteenth century, Bordeaux became the greatest port of French colonial products, with other Atlantic ports such as La Rochelle, Nantes, Brest, Saint-Malo, and Le Havre as distant contenders (Butel Reference Butel1974: 15–23). In the 1770s and 1780s, no less than 85 percent of the coffee produced in the French Caribbean was re-exported to northern Europe (Tarrade Reference Tarrade1972: 753). The main markets were in the German lands and the Baltic, and the main distribution centers for the product reshipped through Bordeaux were Hamburg and Amsterdam (Carmagnani Reference Carmagnani2012: 191; Butel Reference Butel1974: 47–49).

Coffee competition in the Amsterdam market was fatal to the Surinamese coffee economy. By lowering coffee prices in European consumer centers over the following decade, Saint-Domingue’s leap after 1763 altered the operating conditions of its rivals, as is clearly expressed by price curves. As graphic 1 shows, the sharp drop in the value of the Surinamese and Saint-Domingue product in Europe between 1770 and 1776 was a direct result of oversupply from the second region.

Graph 1. Annual coffee prices in Amsterdam, brand Suriname/Saint-Domingue, 1750–1790, guilders per pound

Source of statistics: Posthumus Reference Posthumus1946: v. 1, 75–79.

Surinamese slaveholders, despite having access to relatively cheaper slaves, had to operate in environmental conditions that, in the context of speculative investment from the negotiatie funds in the 1760s and 1770s, eventually over-capitalized their plantations (Emmer Reference Emmer1996: 16), especially regarding land investments (Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan1995: 77). With the boom of Saint-Domingue exports and the fall in world prices caused by it, the Surinamese coffee economy stalled after 1775. Malouet, in 1777, noted the relationship between low prices and high debts in the coffee sector, but did not relate the first variable to developments in the colony where he had his own sugar and coffee plantations. And why was the Saint-Domingue coffee economy unaffected by the price drop brought by its oversupply of the commodity? The answer lies in the character of its spatial economy. Based on the colony’s geo-ecological conditions, the flexible, productive plant largely explains the trajectory of its coffee economy: coffee planters in Saint-Domingue were able to steadily increase supply by incorporating more land (which was relatively cheap) and slaves (who cost about the same as in Suriname).

Brevet’s coffee manual provides information key to understanding how Saint-Domingue coffee planters faced the price drop that they caused between 1770 and 1777. To estimate the returns and possibilities for expanding coffee activity, Brevet drew three scenarios for the equation slaves/coffee prices, assuming a fixed amount of per capita production. The first scenario: if the product was sold in Saint-Domingue at 5 sous per pound, the financial loss would be certain, making it impossible for the planter to honor his commitments to his local creditors. The second: with coffee prices at about 10 sous, it would be possible for the planter to withstand a difficult situation by modestly increasing his investments, “but only with the greatest economy, and assuming that no accident occurs to him.” In the third: with coffee at 15 sous, the planter could easily “increase his strength through slave purchases” (Reference Brevet1768: 55). The local price series in Saint-Domingue ports in the decade after the publication of Brevet’s treatise indicates that the first—and most critical—scenario never came close to becoming a reality (table 5).

Table 5. Coffee prices in Saint-Domingue, 1768–1777

Source: Les Affiches Américaines (https://dloc.com/AA00000449/00009/allvolumes).

Without the flexibility offered by the Saint-Domingue spatial economy, and heavily indebted to negotiatie funds, Suriname planters were unable to cope with the falling prices in European markets that had been produced by the rival colony. Graphic 1 shows how prices began to recover precisely in 1777 and, contrary to Malouet’s prediction, Suriname’s coffee economy remained stagnant.Footnote 14 The crisis in the transatlantic slave trade that Malouet observed in 1777 worsened over the following decade. Indeed, the peak of the transatlantic slave trade to Suriname occurred at the height of the coffee fever in the second half of the 1760s, when 26,741 enslaved Africans were disembarked in the colony. Between 1771–1775 this number decreased to 22,676, but this was nothing compared to what followed when the speculative bubble of negotiatie funds burst: 10,827 slaves disembarked from 1776–1780, 7,305 from 1781–1785, and 5,694 from 1786–1790.Footnote 15 The collapse of the transatlantic slave trade contributed to the definitive spatial sedimentation of maroon communities within the territory, in areas away from a slave economy that had lost momentum and, consequently, Suriname’s ability to expand its plantation frontier. Even the Boni managed to reach equilibrium. After taking refuge in French Guiana lands, they seldom attacked the plantations of Suriname. Following a short resumption of the conflict in 1789, in 1791 they finally signed a peace treaty in which they placed themselves under the tutelage of the Djuka community (Groot Reference Groot1975: 46–47; Hoogbergen Reference Hoogbergen1990: 162).

malouet and the genesis of the saint-domingue revolution

We must now return to the official mission that brought Malouet to Suriname and how his agenda after that visit was related to the growing tension of social relations in Saint-Domingue. Since the mid-eighteenth century, an important fraction of the French Enlightenment thinkers had been discussing with some intensity the problem of African slavery in the colonial world. One of the most common themes in this literature was the issue of slave resistance and what it revealed about the negative role of slavery in a world that should be regulated by natural rights (Duchet Reference Duchet and Arámburo1971: 121–68; Ehrard Reference Ehrard2008; Dobie Reference Dobie2010: 199–251). Generally speaking, this was the frame of reference for both the Kourou colonization project and Baron Bessner’s plans to recruit Surinamese maroons to develop French Guiana with free laborers. Bessner’s plan informed the literate Jean-Joseph de Pechmejá, one of many contributors to the Histoire des Deux Indes, the collective enterprise signed by L’Abbé Raynal. In the 1770 edition, Pechmejá wrote the critical passages concerning slavery in the Americas, incorporating Bessner’s proposal for the mobilization of Surinamese maroons (Thomson Reference Thomson2017: 260). The next edition of the Histoire, in 1774, raised the critical tone by combining direct references to slave resistance in Jamaica, Suriname, and Saint-Domingue (as the 1757 Makandal case) with the prognosis—taken from the utopian writer Sebastién Mercier—that a failure to reform African slavery in the New World colonies would lead European colonial powers back to the classical world, but now with different results: “Where is he, this new Spartacus, who will find no Crassus?” (Raynal 1774 in Thomson Reference Thomson2017: 265).

Malouet’s visit to Suriname was informed by this prognosis. He was able to see the difficulties in the war against the Boni, Nepveu’s efforts to build a solid defensive line east of the colony, and, above all, the utter infeasibility of Bessner’s plan that was incorporated into the 1770 and 1774 editions of Histoire des Deux Indes. Bessner and Raynal/Pechmeja, in Malouet’s opinion, were speculative intellectuals who had no idea of the realities of colonial slave relations. Counting on the maroons to colonize French Guiana was far-fetched, but the experience of Suriname showed the risks of slavery for the French Empire. In a report on the Surinamese maroons sent to the French government in August 1777, Malouet argued, “The masters who abuse in all European colonies the terrible right of the strongest are the real authors of the inner disorders; and governments that tolerate these abuses, which refuse all protection to the slave for as unjust respect for the masters’ property, truly compromise this very property and the security of the masters themselves” (Reference Malouet1802: v. 2, 61). We can be sure he was paying attention to not only what was happening in Suriname but also the events occurring in the place where he had his investments. Marronage was endemic in Saint-Domingue, especially in its highlands (Fick Reference Fick1990: 46–75). There was nothing similar in Saint-Domingue to the scale of the Surinamese maroon communities, and coffee expansion was significantly reducing the backland spaces for marronage there (Geggus Reference Geggus2002: 74), yet Malouet’s experiences in both colonies was signaling to him the common ground of the dangers that slave resistance presented to the colonial order. Therefore, the metropolitan public powers needed to take a more active stance to secure the private interests of the colonial slaveholders. Malouet’s conclusion, expressed earlier in texts he had written in 1775 and based on his experience as a member of the French Navy stationed in Saint-Domingue and as an absentee planter, was that the state should intervene in the private management of slaves to curb “domestic despotism and its excesses.” He directly related overwork and excessive punishment, without the counterweight of slave religious doctrine, to the slave flights and rebellions. As he made clear in a 1777 private letter, “If we do not soften the condition of the slave…, as a result, our colonies will experience the same revolutions as Suriname” (Debien and Kraal Reference Debien and Kraal1955: 56; Ghachem Reference Ghachem2012: 150–54).

The French monarchy’s response to these and similar demands came in the following decade, with the ordonnances of December 1784 and December 1785. Focusing primarily on the jewel of the Empire—the colony of Saint-Domingue—these new legal norms laid down rules for the management of plantations owned by absentee planters (like Malouet) and opened channels for slaves to complain of ill-treatment to the public authority (in this case, in courts elected locally by the masters). The ordonnances also reiterated the Code Noir’s provisions regarding the supply of clothing and food; gave slaves free time on Saturday afternoons; obligated planters and managers to allow slaves to cultivate their own garden plots; sanctioned their free access to the local Sunday markets; and limited the powers of managers of absentee plantations to punish them. These legal measures were strongly opposed by the colonial planters residing in Saint-Domingue. They understood that they represented the demolition of the principle of domestic sovereignty, which assumed that the determination of slave labor and discipline should be the exclusive responsibility of the owners. Faced with the new policy of the French metropolis, colonial planters developed another doctrine to justify the unrestricted rule over their slaves: slavery was despotic by its innate nature, they argued publicly after 1785, and thus any attempt at external interference with the domestic government of slaves would undermine the foundations of the institution by preventing the master’s effective command over his laborers (Marquese Reference Marquese2004: 120–21; Debbasch Reference Debbasch1985: 43–46; Tarrade Reference Tarrade and Dorigny1995; Ghachem Reference Ghachem2012: 155–64).

These disputes between the state and planters on one hand, and masters and slaves on the other, were part of the growing politicization of slavery in Saint-Domingue in the years before the French Revolution. The slaves made their own reading of these 1784–1785 clashes and saw in the king an ally against their masters, which helps explain their initial royalist allegiances in the immediate aftermath of the big 1791 slave rebellion (Dubois Reference Dubois2004: 36–59). In short, the experience of Surinamese maroons made an important contribution to the formation of the French antislavery culture while sparking divergent responses within the proslavery camp to which Malouet belonged. While slave disembarkations fell in Suriname due to the coffee crisis, which reduced the tensions between masters and slaves, the coffee boom in Saint-Domingue (the central variable of the Suriname coffee crisis) led to a slave-trading boom in the second half of the 1780s. This introduced into the colony the actors who, inspired by the antislavery ideals of Enlightenment, would later overthrow colonialism and slavery in France’s “Pearl of the Antilles.”

This article has proposed a substantive comparison between the coffee economy of Suriname and that of Saint-Domingue. Rather than taking the specific combinations of land, labor, capital, and political power as an independent and locally determined set, as a formal comparison would do, I have examined how the coffee trajectories of Suriname and Saint-Domingue were mutually formative through the specific evolving relationships that each space had within the world-system. Due to the particular articulations each region had with the wider constellation of the historical forces of European capital and colonialism, what was happening in the Dutch colony changed the general conditions of what was happening in the French colony, and vice versa. Indeed, the success of the Saint-Domingue coffee plantation economy was decisive for the crisis of the coffee plantation economy in Suriname, while the experience of slave resistance in the Dutch colony was a critical factor within the bundle of tensions that led to the revolutionary explosion in Saint-Domingue in 1791.