Let us acknowledge it, let us feel that India is not confined in the Geography of India—and then we shall find our message from our part. India can live and grow by spreading abroad—not the political India, but the ideal India

———Rabindranath Tagore, 1920Footnote 1In his Foreword to Revealing India's Past (1939), the famous French Sanskritist and expert on Buddhist iconography Alfred Foucher reflected on the trend of “Pacific Ocean” congresses that archaeologists had been organizing in Asia since the late 1920s. He suggested also having “Indian Ocean” congresses, where, he reasoned, scholars could contemplate the remarkable Hindu-Buddhist civilization of Asia. To understand this civilizational puzzle, he argued, one had to recognize that India was the “center” and “cornerstone.”Footnote 2 The island of Java in the Netherlands Indies was, in that same regard, “only an Indian colony,” as he had explained in a public lecture much earlier.Footnote 3 Foucher did not seem to care whether local subjects in Java, colonized by the Dutch and forming a majority of Muslims since at least the sixteenth century, would agree with this. Nor would he have imagined the potential violence of this common scholarly habit of his time: treating what today are South Asia and Southeast Asia as a single cultural region.

This article analyzes, for the period from the 1890s to the 1960s, the makings and politics of a persistent framework of thinking about Asia, for which Foucher's ideas and the label “Greater India” are representative. The latter was both an academic and political concept in Foucher's time, but in this essay I use it to refer to a much larger and more fluent yet palpable set of ideas that people in both Asia and the West project on today's South and Southeast Asia. This Greater India implies the idea of a spiritual Hindu-Buddhist civilization that, since ancient times, had spread its wellness from India over a receiving southern region. To its influential believers, it provided the superior standard for understanding culture in what we now call Southeast Asia. In the light of the spatial turn and trans-oceanic and transnational approaches to Asian history, it is pertinent to explore the workings and legacies of this way of viewing the region. Over the past three decades, in the context of a widely felt discomfort about state- and empire-centered historiographies and the artificial boundaries of Area Studies, the “Indian Ocean” has once again become a popular frame for historians of South and Southeast Asia, driven by historical and empathic efforts to understand marginalized “local” and diasporic perspectives.Footnote 4 As the example of Foucher shows, however, the framing of transregional geographies as an analytical tool is not new, but rather is indebted to older colonial scholarship that, as others have pointed out, was problematic. Although inspired by these more recent transnational, “Oceanic” approaches to Asian history, this article also warns against their pitfalls, as they can reproduce essentializing views on the region as a cultural unity and, in doing so, reify ideas of Greater India.Footnote 5

Greater India thinking has displayed a continuity and worldwide reach that, via academia, museums, and popular culture worldwide, has exercised a lasting influence on how people in Asia and the West view South and Southeast Asia. Ideas of Greater India resonate in the worldwide popularity of Yoga and Ayurveda, perceived as unchanged, wholesome goods from an ancient India. And, as this article highlights, they dominate in archaeological research and study in and on Asia, in “Asian art” collecting, exhibits and marketing, and the category of Asian art itself. The question is how and why such ideas developed in that field, and how it thereby became part and parcel of (epistemic) violence, structuring the way many people across the world think of Asia. From the Metropolitan Museum in New York to Musée Guimet in Paris and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, well-choreographed exhibitions strategically use light and space to emphasize the spiritual power and inner beauty of Hindu and Buddhist statues, evoking ideas of Greater India (see Figs. 1, 5, and 8). In this way, they obfuscate the violence underlying how objects were collected and depict Southeast Asia as the passive recipient of a superior Indian civilization.Footnote 6

Figure 1. “Indonesia, Java,” part of the Southeast Asia section in the Metropolitan Museum. The first phrase of the introductory text is: “The roots of the classical tradition of Southeast Asian art lie in historical contacts with India.” Author's photo, November 2014.

At the same time, Indonesia, home to the world's largest Muslim population, is usually absent from both old and new permanent displays of “art” from the Islamic world, like those in the Louvre in Paris (2012) or the Metropolitan in New York (2015). This parallel and complementary problem of ignoring Indonesian Islam has been observed by other scholars as well, though they have focused on the imagination, collecting, and study of Islam.Footnote 7 We need to scrutinize why and how this double bias developed and helped create a persistent moral-cum-spatial imagination of “Asia” as a greater Hindu-Buddhist India.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the idea of Greater India became most clearly embodied politically in the Greater India Society, founded in Calcutta in 1926. As other scholars have discussed, this society was formed by Bengali historians and intellectuals with whom the internationally well-connected Nobel Prize winning Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore associated. It heralded a nationalist vision of a benign, spiritual, Indian civilization having disseminated across Asia in the past, and it propagated the study and revival of that civilization in the present.Footnote 8 In a groundbreaking essay, Susan Bayly showed how much this society's vision of Greater India was inspired by French scholars, in particular one of Foucher's colleagues, the Sanskritist Sylvain Lévi in Paris, and how it took on explicit political forms in India.Footnote 9 Most critical studies have explored this problem from an India-centered perspective. Here, I will instead follow the perspective of the outsider inside: Indonesia. The question is why and how a predominantly Islamic Indonesia became situated in this Greater India-mindset. To answer this, I explore the roles of sites in Indonesia (ancient religious sites, transforming into heritage sites), their moveable objects, and the affections they stir, as well as the knowledge networks that connect these three categories. I employ a mobile, sites-centered, objects-biographical approach, zooming in on the charmed knowledge networks that objects created, in order to understand how multiple, changing power relations and violence shape knowledge and vice versa.Footnote 10

Engaging with recent debates on the role of religion in the study of Orientalism,Footnote 11 I propose that the motif of love, or empathy, and the related concept of “cultural understanding,” and (perceived) affections in knowledge production can help explain the ossifying endurance of ideas of Greater India. I argue, moreover, that the Greater India mindset has plural forms and centers and has had a reach far beyond Calcutta in time and space. To understand the magnitude of its global socio-political impact, we need to explore Greater India thinking beyond India-centered perspectives and understand the workings of “transnational” power relations elsewhere, such as those generated by intercolonial and inter-Asian knowledge networks located in colonial and postcolonial Indonesia.

I begin by elaborating on why and how I use the concept of “moral geographies” to tackle this problem,Footnote 12 and by introducing this article's second motif: the role played by affections, love for objects, and friendships in collecting networks in fostering a Greater India mindset. This is followed by an exploration of scholarly criticisms of the Greater India paradigm that have developed since the 1920s and 1930s, after which I return to the question of why, where, and how, despite this criticism, Indonesia, through its “moveable” objects, came to be situated in moral geographies of Greater India.

MORAL GEOGRAPHIES OF GREATER INDIA, AND THE POLITICS OF AFFECTIONS

A counterpart to the shining reputation of Greater India is a long history of principled distrust toward Islam and so-called “Islamic regions.” This raises important questions: Why do we construct ideas about space in moral and civilizational terms? How and why does the reputation of one idea (here Greater India) come to dominate at the expense of others? And how does this affect our relationships with others, whether we live or move inside or outside of that space?

Since the spatial turn of the 1990s, scholars have become aware that space is not a neutral object of study: spatial relations are socially constructed and they change, compete with, and influence social relations.Footnote 13 The concept of moral geographies sharply captures the phenomenon of how the spatial imagination can surpass and even shape social relations. However, in social-cultural geography,Footnote 14 cultural history,Footnote 15 or, comparably, in Asian studiesFootnote 16 it has been overwhelmingly applied in what we might call inward-looking ways, to analyze how people perceive and use space within particular states or communities and exclude other people from them. Here, by contrast, I use the concept of moral geographies in ways that are transnational and outward-oriented. First, it serves as a heuristic device to understand how people have imagined their own or other peoples’ belonging to a distant, transnational space—Greater India—while excluding others, whether or not they live within that space. Second, moral geographies of Greater India are a social phenomenon to be scrutinized in their own right, as they are shaped through time and space and travel within and outside of the region, from Asia to the West and back again. The study of how such transnational moral geographies compete with those of nations and communities is fundamentally important. For, like Greater Slavic Russia or Greater Syria, while they have the power to connect people across time and state boundaries, they can also violently exclude and oppress other people at both local and global levels.

In exploring the role of affections in creating such moral geographies I am inspired by the work of literary scholar Leela Gandhi.Footnote 17 Her Affective Communities (2006) focuses on the politics of friendships between figures that have been marginalized by postcolonial and national histories and that seem to have crossed the divide between colonizers and colonized: the theosophists, vegetarians, and spiritual seekers who traveled between Europe and India during the high tide of imperialism around 1900. Though not taken seriously in national historiographies, these figures were cultural elites who often had financial and political power as well. They were part of the kinds of networks that I focus on here: scholars of Asia and connoisseurs and collectors of “Asian art.” They came together in an associational movement of Asian art lovers against the background of a taxonomical shift, starting in the 1910s, toward the appreciation of ancient religious sculpture from Asia as high-brow art. Followers of this movement self-identified as “Friends of Asian Art” or “Friends of Asia.” Gandhi argues that the “affective communities” she discerns could transcend colonial difference and feed into anti-colonial critiques.Footnote 18 In what follows, I build on that insight to argue that affective relationships between scholars or connoisseurs, and their love for “art” objects, became both part of anti-colonial critiques and supportive of European colonialism. Moreover, they generated blindness toward, or passive tolerance of, the violence of heritage formation within and beyond colonial and postcolonial state borders. All along, these affections fed into India-centered forms of cultural imperialism that ignored Islam or pushed it out of sight.

LOCAL GENIUS: CRITICIZING INDIANIZATION THEORY

A long line of scholarly critiques of the Greater India paradigm reach back to the heyday of Greater Indian scholarship. These critiques have been predominantly archaeological and have had little impact beyond that field. Only recently has it started to subtly influence museums of Asian art, and it has triggered some alternative exhibits of Islamic art that include or even focus on Southeast Asia.Footnote 19 In most older museums, though, curators wishing to show more interactive perspectives on ancient Hindu-Buddhist Asia are hampered by bias in their collections and perhaps by their love for them.

From the 1910s, colonial scholars working in the Netherlands Indies, French Indochina, or British Burma and the Malay States began to write critiques of the Greater India paradigm. They did so partly in reaction to their India-oriented Sanskrit teachers, and in the context of a booming study of prehistory in Asia, which resulted in the trendy “Pacific Ocean” congresses mentioned earlier.Footnote 20 Against “Greater India,” and working with terms like “flows,” “acculturation,” and “adaptation,” they postulated another romantic concept, that of a creative “local genius” which functioned before the Indians arrived.Footnote 21 Basing their thoughts on research they conducted in the region, and sympathizing with what they deemed “local,” these scholars provided alternative concepts, sources, and methods of research that could contribute to a recognition and gauging of the role of local agency in the region's civilizational history. In that sense, their work influenced the postcolonial generation of scholars, and in postcolonial Indonesia “local genius” became an argument in archaeology and history writing that emphasized the creative nation.Footnote 22

After World War II and violent recolonization wars, when countries in Asia gained formal independence, criticism against Indianization theory continued in archaeological and historical studies, including in the West. In the United States, the new “Area Studies” departments and approaches were developed partly with the help of colonial scholars who had, by today's standard, unusually long-term research experience in Asia. These new university departments set Southeast Asia apart from South Asia, now as separate regions. Against that backdrop, from the early 1960s “Indianization” theory, along with European and colonial state-centered historical writing on the region, met with new forms of criticism. These took the form of a sub-regional focus on “autonomous” history and, in handbooks, on the study of Southeast Asia “in itself.”Footnote 23 The influential Southeast Asian scholar O. W. Wolters, based at Cornell University, critiqued the idea that “Indianization” had introduced an “entirely new chapter in the region's history.” Taking stock of pre-Indian, prehistorical, and archaeological research, he preferred to talk about “Hindu” or “religious” influences (rather than “Indian” or “political” ones), which in his view, much in line with the notion of “local genius,” “brought ancient and persistent indigenous beliefs into sharper focus.” Wolters argued that Southeast Asian Kingdoms had developed all along while “localizing” the (Indic) model of a mandala in the form of multiple overlapping mandalas—circles around one king with divine, universal authority.Footnote 24

And yet, in the postwar period the Greater India perspective continued to dominate the field of the arts of South and Southeast Asia. The Metropolitan Museum in New York, for example, after a huge renovation of its Asian art galleries, reopened in 1960 with an exhibition encapsulating material remains of Southeast Asia entitled “The Sculpture of Greater India.”Footnote 25 Similarly telling is the opening sentence from a popular academic handbook of 1967, Art of Southeast Asia: “The culture of India has been one of the world's most powerful civilizing forces […] the members of that circle of civilizations beyond Burma clustered around the Gulf of Siam and the Java Sea virtually owe their very existence to the creative influence of Indian ideas.”Footnote 26

Still today, despite persistent scholarly criticisms of Greater India views,Footnote 27 and though some institutions, most notably the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, have produced more nuanced efforts that emphasize reciprocity, we continue to encounter the shining presence of Greater India not only inside most prestigious museums of Asian art or world civilization, but also outside, in influential media. This is apparent in a jubilant review in the New York Review of Books of two blockbuster Metropolitan Museum exhibits: “Buddhism along the Silkroad” (2012–2013) and “Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Southeast Asia” (2014). Contemplating the two shows, the Scottish historian William Dalrymple concluded: “For it is now increasingly clear […] India during this period radiated its philosophies, political ideas, and architectural forms out over an entire continent not by conquest but by sheer cultural sophistication.”Footnote 28 He emphasized that “the cultural flow was overwhelmingly one way,” quoting in affirmation Michael Wood, from Wood's BBC television series on India, that “history is full of Empires of the Sword, but India alone created an Empire of the Spirit.”Footnote 29

Nor is it helpful that even some of the scholarship that problematizes Indianization theory still works with conference titles like, “Early Indian Influences in Southeast Asia.”Footnote 30 If we continue to think of a Hindu-Buddhist India as the source of the cultural-political developments of other regions, then concepts such as adoption, adaption, acculturation, localization, and even interaction remain mere ornaments to a shining center, and a shining idea.Footnote 31 More nuanced scholarly studies critical of Indianization theory will, moreover, do little to enlighten popular culture worldwide, in which Asia still often stands for India, yoga, the Buddha, and spiritualism. Why, we must ask, is it still so hard for curatorial experts of the region's ancient Hindu-Buddhist past and the material sources it left behind to write about Southeast Asia or its sub-regions without starting with India? I think the answer lies in the questions, priorities, and networks of archaeological knowledge production, art collecting, and art marketing; in taxonomic shifts in the appreciation of ancient religious objects from Asia; and thus in love and its potential epistemic violence. By loving, capturing, or moving away an object, we may destroy a unity between the object and its site of origin, and disregard local memories, concerns, and care. This is to enact a form of injustice, because these local concerns matter, whether or not the objects still carry the same meanings as they did for those for whom they were originally made.Footnote 32

MOVEABLE OBJECTS, PETRIFYING LOVE

In 1884, in the midst of the ongoing war of conquest waged by the Dutch colonial army in Aceh, on Sumatra in the Netherlands Indies, the French adventurer-geographer Paul Fauque visited an old, and—he apparently presumed—abandoned Islamic graveyard near Kota Raja and took away three fourteenth-century stiles that he thought were wonderfully sculpted. He sent them to France as a gift to the Musée de Trocadéro, the ethnographic museum in Paris founded by the Ministry of Public Education in 1878. In his official report, Fauque described the Islamic funeral practices he had observed in the region and the particularities—date, form, and size—of the stiles, information he must have gotten from local informants. He also provided drawings of the stiles.Footnote 33 Partly for documentation, he made sure photographs were taken of himself at the graveyard and of the three tombs from which he took the stiles (Fig. 2). Later, in November 1885, these images were used in a seminar at a session of the French Geographical Society in Paris.Footnote 34

Figure 2. Islamic graveyard in Aceh, with the three old stiles that were selected by Paul Fauque. Photograph by François Marie Alfred Molténi, 1884 (Bibliothèque Nationale Française, Société de Geographie, Collection Molténi, inventory no. 0530, 12).

Accentuating the conventional self-image of the colonial archaeologist as a great discoverer of unknown and neglected ancient civilizations, Fauque provided no information as to the conditions under which he took hold of the Islamic stiles.Footnote 35 What had impressed him most was not necessarily their function but rather their beauty, or the aesthetic characteristics with which he could identify. He recognized in them a mix of “Hindu and Arab arts,” which he thought exemplified the “high level” of taste among the ancient population living in Aceh during the “invasion of the Muslims” in the Malay archipelago, which he situated in the mid-fourteenth century.Footnote 36

Thus, a selective aesthetic sensation of a French scholar-adventurer, generating his love for the objects, and his abducting them from their original site, signed the curious fate of three ancient Islamic stiles from Sumatra. The stiles were transferred a number of times between various ethnographic museums in Paris and, along the way, they were elevated from the category of ethnographic artifact to that of religious art. Since 1930, they have been held by the Museum of Asian Art in Paris, Musée Guimet.Footnote 37

Fauque recognized the objects as unmistakably Islamic, and he noted the Arabic text on the back of one, which his unnamed informant translated as a five-times repetition of “Allah.” As such, the stiles are today the only objects from Indonesia on display in Musée Guimet that we can clearly identify as Islamic (see Figs. 3 and 6).

Figure 3. Stiles that Fauque sent to France, now on display at the Indonesian section of Musée Guimet. Author's photo, November 2017.

The museum modernized its permanent exhibition in the 1930s under curator Philip Stern, and like most prestigious museums of Asian art across the world it has ever since employed seductive exhibition techniques to create a modern shrine of ancient remains of Asian Hindu and Buddhist pasts, defined as religious art. The museum was founded in 1889 by the French industrialist and social reformer Émile Guimet (1836–1918), who, before he opened his first museum in his hometown of Lyon in 1876 had traveled to Egypt, Greece, Japan, India, and China.Footnote 38 Set up originally as a museum of the history of religion for the education of the French people, today it exhibits objects originating from Afghanistan in the west to Japan and Korea in the east. India is presented as the creative source of inspiration, but, in a French touch, the treasures from former French Angkor, in the museum's central court, form the proud and beating heart of the permanent exhibition. Here, within the framework of “Indianized Buddhist” art from Southeast Asia, the Indonesian section—located between those of Burma and Vietnam—also shows mostly material remains of Indonesia's pre-Islamic, Hindu-Buddhist past. Most of the objects date from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries. For the visitors’ guidance, the museum's general introduction to this section presents India as the standard: “Dans la statuaire les apports Indiens sont encore discernible, quoique transfiguré par un art empreint de grâce et du douceur (In the sculptures, the Indian influences are still visible, however transformed by an imprint of grace and softness).Footnote 39

Again, this narrative and the manner of exhibiting is not unique. The three Islamic stiles from Sumatra seem therefore all the more remarkable, contradicting as they do the contention of this article that, from the 1880s–1960s, what drew the eyes of self-made Orientalists, adventurers, archaeologists, and collectors in Indonesia was Hindu-Buddhist by dedication. The stiles also seem to defy my previous observation that Indonesia, in almost all the world's prestigious museums of Asian art, ends up represented as a Hindu-Buddhist country. At the same time, due to their “mixed Hindu-Arab style” the Islamic stiles were well-suited to the scholarly diffusionist theorizing on civilizational history that emerged around 1900.Footnote 40 Like the other Indonesian objects kept in museums of Asian art or of universal civilizations (such as the British Museum), the Islamic stiles were subjected to a dominant interest among scholars and collectors in the external, Indian, civilizational influences in local Asian histories. From around 1910, this interest became pivotal to the inception of a new category of, and theorizing on, “Asian art,” and the emergence of the “Friends of Asian Art” movement and market, which I will address below in more depth.

Importantly, the stiles also exemplify a practice of carrying away ancient sculptures and statues from their sites of origin, whether graveyards or temples, which does not seem to have troubled those doing the taking. In our monograph on the politics of heritage in Indonesia, centralizing sites, and the mobility of objects, Martijn Eickhoff and I discuss several such nineteenth-and twentieth-century abductions.Footnote 41 One, stark example of unfortunate appropriation is the statues of the ninth-century Buddhist Singasari temple in East Java, famously carried away by colonial administrator Nicolaus Engelhard in 1804, and since 1815 kept in the Netherlands. Today they are displayed at the Museum of World Cultures in Leiden.Footnote 42 Dutch colonial, foreign, and local elites, as well as commoners, all have moved antiquities away from their original sites, for reasons ranging from love, to local and transnational religious practices, care for or fear of the spirits they entailed, a sense of status, colonial national pride, political and economic calculation, blunt practical reasons, or some combination of these motives. Yet, if we think further on the fate of Fauque's Islamic stiles, such acts can be perceived as inappropriate or as looting, and at times, including in the past, they have been seen as such. This should make us feel still more uncomfortable about their present fate.

Even in the nineteenth century, the removal of antiquities was sometimes condemned. For example, in 1897 the board of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences in the Netherlands Indies’ capital of Batavia were outraged to learn, through passing mention, that the Dutch director of the Arts and Crafts-school in Haarlem, E. A. von Saher, intended to take away actual objects from niches of the ninth-century Siva temple at Prambanan, instead of only making plaster casts on location. Von Saher was in Java to take casts of the eighth-century Buddhist temple of Candi Sari, a full copy of which would serve as the Dutch colonial pavilion at the world exhibition in Paris.Footnote 43 In a letter to the organizing committee of that pavilion, the Batavian Society prohibited von Saher, with emphasis, from taking the Siva temple's objects. Apparently, however (as I have discovered since first writing about this case), he was allowed to take away some loose objects scattered around the sites of the eighth-century Buddhist shrine of Borobudur and the ninth-century Hindu temple complex Prambanan, both in Central Java, which were put on display at the then-new Colonial Institute in Amsterdam between 1918–1946. In 1951 they were offered to the Metropolitan Museum by von Saher's son, who had become a law consultant in New York. For this gift, von Saher Jr. was honored as a fellow of the museum for life.Footnote 44

If one thing is clear for these sought after, token objects, it is the place they belonged to, as attested by the vacant space in an ancient graveyard, the empty niche in a temple, or the headless Buddha that cannot watch over its realm. Place and space here have connotations other than the essentializing notions of “patria,” “home,” or “ownership” implied by ongoing global debates over “repatriation,” “return,” and “restitution.” These debates are part and parcel of a much needed cultural-political decolonization, but they are unhelpful if one's goal is to understand the wider, complex socio-political histories of these objects, their changing meanings and values, and the roles they play in moral geographies other than those of “patria” or the nation.Footnote 45 Provenance, and the moment and aims of creation, are not the only aspects of an object that make it matter.Footnote 46 The objects’ subsequent social histories, as they travel in space and time within various forms of exchange, including thefts or sales, their meanings and values steadily changing in route, are highly relevant if we seek to know the political history and impact of heritage formation. “Restitution” can be seen as merely another phase in an object's complex socio-political life. However, that life may “end” in a museum's depot via a simple legal acquisition that conceals an essential form of injustice. While these same objects can tell of this injustice, they are rarely given the chance to do so. In the examples discussed in this article, this injustice is related to not only Western colonial expansion in the region but also India-centric forms of cultural imperialism and moral geographies of Greater India.Footnote 47

FROM BOROBUDUR TO THE WORLD

The eighth-century Buddhist shrine of Borobudur in Central Java, the world's largest, has since 1991 been drafted as a world heritage site (Fig. 4). It provides a telling example for this history of love, violence, and injustice that contributed to creating moral geographies of Greater India. It does so together with the multitude of heads from Borobudur's Buddha statues that are now scattered through world premier museums of Asian art or world civilization. These Buddha heads display the intercolonial, transnational, and international dimension of a developing art market in Hindu-Buddhist antiquities, as well as the violence this has entailed.Footnote 48 Originally, Borobudur counted 504 Buddha statues, representing six meditative postures of the Buddha. Four postures—bumisparsa mudra (touching the earth), vara mudra (giving), dyana mudra (meditating), and abaya mudra (eliminating fear)—were each represented ninety-two times at the four lower levels on each side of the temple, and the fifth, vitarka mudra (preaching), was represented sixty-four times in the highest gallery. Seventy-two Buddha statues in the smaller stupas sat in preaching postures on the three circular terraces that surround the central, largest stupa.Footnote 49 Finally there was the so-called “unfinished Buddha,” once posted in the main stupa but moved from there by Theodor van Erp during his famous restoration of the temple in 1907–1910. We find it now in the site museum, carrying the debates over its original location and receiving regular offerings in its lap.Footnote 50 Today, of these 504 Buddha statues, forty-three are fully “missing,” their posts left vacant. Over three hundred others are damaged, of which 250 are “headless” (Fig. 5). According to the Borobudur Conservation Centre, only fifty-six “loose” heads remain on site.Footnote 51

Figure 4. Borobudur, Central Java, Indonesia. Author's photo, May 2016.

Figure 5. Headless Buddha statues at Borobudur. Author's photo, May 2016.

The Borobudur Buddha heads, and the ways in which they came to be displayed in their new museum housings and private collections, tell us as much about the rising interest in Hindu-Buddhist antiquities as Indian art as they do about the casualness with which such ancient objects were removed, and gifted or sold. The following examples may seem “selective” or arbitrary, but like the Islamic stiles, they prove my general point: that violence, love, and heritage formation are connected with each other and also with the formation of moral geographies of Greater India. They also show how, as Eickhoff and I have argued (2013; 2020), Marcel Mauss’ theories of “the gift” are crucial to understanding the political dynamics of heritage formation. By the act of giving or taking (in the present case of an object), the one who gives or takes presumes ownership, generating complex relationships of interdependency.Footnote 52

The case of the Borobudur Buddha heads also illustrates how and why an emerging Asian art market based on new taxonomies of Hindu-Buddhist antiquities, and interacting with modern museum tastes, facilitated such acts of violence. For a new sense of love for the objects (often in the guise of greed), whether felt by the amateur-tourist or the self-made expert, along with the growing market values projected on Java's Hindu-Buddhist antiquities, spread along intercolonial and international knowledge networks to locations elsewhere in the world. There, the violent acts of dislocation and appropriation (taking) took on the guise of innocence, friendship, and cultural understanding (giving).

In April 1910, Émile Guimet received a letter offering to fill in what the sender perceived to be a gap in his collection. The French engineer (and former senator of Seine-et-Oise) Paul Decauville (1846–1922), famous for creating a light, small, and portable railway system named after him, explained to Guimet that when he had visited the museum's galleries a few days before, he had noticed that it had no “heads” of Buddha statues on display. He himself happened to have two, which, he wrote, derived from the eighth-century ancient Buddhist shrine Borobudur in Java. He had always kept them in his country house, but now offered to sell them to the museum, with a discount, from 5,000 francs apiece (which he initially had in mind) down to 3,000 francs each.Footnote 53

It is unclear whether Guimet actually bought the two Buddha heads, since the file holds no answer to this letter, nor do the heads show up in Musée Guimet's catalogue of its Indonesian collections.Footnote 54 Be that as it may, what matters to us here is their previous biography, the “casualness” with which they were taken from the site, and the context that legitimized this act, of the modernizing and opening up Java—growing private/tourist heritage interests and a local market stepping in. Twenty years before, Decauville explained to Guimet, the two Buddha heads were brought to him by one of his engineers who was in Java to study the possibilities for implementing his railway system. In Central Java, the area richest in Hindu-Buddhist temple remains, he must have met the Dutch engineer J. W. IJzerman, in charge of constructing a railway system there, who had co-founded the private Archaeological Society in Yogyakarta in 1885. IJzerman became an engaged, self-made archaeologist, co-responsible, with the support of the sultan of Yogyakarta and his Javanese photographer Cephas (a Christian convert), for the first photographing and clearing up of the nearby ninth-century Prambanan temple in 1885 and 1887–1889, and for uncovering, photographing, and recovering the so-called “hidden” reliefs of Borobudur's lowest gallery in 1889–1891.Footnote 55 It must have been in that context that Decauville's engineer also visited Borobudur. How his engineer got his hands on the two heads remains unclear, though Decauville wrote that he had done so “with great difficulties.” Decauville included photographs (which are not in the archives) to convince Guimet of the artistic effect of the heads sculpted in lava stone, and of that temple which competed with that in Angkor.Footnote 56

To compare trajectories and market values, we can follow another Borobudur Buddha head that between 1913 and 1917 traveled from Paris to New York. In Paris it had been shown at the Buddhist art exhibition of 1913 in Museum Cernuschi, founded in 1898 in the mansion of Italian banker and Asian art-collector Henri Cernuschi (1821–1896). There, such religious sculptures became desirable as “distinguished” works of art. As such, this Buddha head changed owners, moving from the famous French art collector Alphonse Kann (1870–1948) to the New York-based Armenian art collector Dikran Kelekian (1866–1951), who in turn sold it in 1917 to the Metropolitan Museum for US$3,000.Footnote 57 How the prices of the Borobudur Buddha heads from Decauville and Kelekian compare by today's valuations is difficult to estimate, since inflation calculators differ wildly in their methods and reasoning. For a general idea, though, one website sets Decauville's 3,000 Francs at US$442 in today's dollars, and Kelekian's US$3,000 at US$,2,240, indicating a rise in price of US$1,798 within seven years.Footnote 58 Within that same span of time their aesthetic and moral valuation also changed tremendously.

It seems that Decauville's Borobudur Buddha heads did not enter Musée Guimet in 1910, but later two other samples, acquired from other French private collections, did. One arrived in 1932 as a gift from the famous French-American banker and art collector and patron David David-Weill (1871–1952), and the other in 1956 as a gift from a certain Dr. André Got in the memory of his son Claude, who had died “pour la France.” Today, Got's Borobudur Buddha-head, in the center of Musée Guimet's Indonesian section, gives Buddhist meditative aura to this Indonesian space, as one religious-artistic step, like the Islamic stiles, in an external, Indian civilizational art history of a Hindu-Buddhist Asia (Fig. 6). It is as yet unclear how the Buddha heads entered into the collections of either David-Weill or Got,Footnote 59 but the museum acquired them through an exchange, sealed by a form of honoring in the name of France that covered an original deed of injustice with a religious, aesthetic valuation.

Figure 6. The Indonesian section, Musée Guimet. Got's Borobudur Buddha head is in the front, and the Islamic stiles from Aceh are visible in the back left corner. Author's photo, November 2017.

If we want to understand the functioning and violent implications of the global trade in “Asian” antiquities, better we let our historical imagination speak, not through the art displays in the museum, but through the sites of ancient Hindu-Buddhist temples and shrines in Asia that delivered objects for them. Such a site-centered imagination may explain the wave of criticism that followed the news that King Chulalongkorn, while in Java in 1896 on a diplomatic visit and Buddhist pilgrimage, had carried away “eight cartloads” of Javanese antiquities, notably also from Borobudur. These souvenirs from Java's Buddhist and Hindu temples, however, were gifted to the King, by the Netherlands-Indies government and by private colonial and Javanese elites, all thus presuming the role of owner.Footnote 60 Yet, such gifts, by that time, raised awareness of a market that encouraged such site-destructive actions. As early as 1899, the Dutch colonial newspaper Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad had reported that it was common for tourists to cut parts of “one statue or another” from Borobudur and that Javanese did so as well to sell them to tourists.Footnote 61 This awareness legitimated the colonial state's push to centralize heritage politics. Within this context of growing public and official concern about the deteriorating state of Borobudur, in 1913 the Netherlands Indies Archaeological Service took shape, developing from the Archaeological Committee formed in Batavia in 1901. The service took charge of caring for Dutch Colonial, Hindu-Buddhist, Islamic, and Chinese antiquities in the Netherlands Indies, and drew up a Heritage Law (officially implemented in 1931). That said, it never fully controlled what happened at its selected sites regarding either local narratives and meaning-giving or private destructive interventions out of “liking.”Footnote 62

The worries expressed in the public reports and private correspondence of the Archaeological Service from the 1920s and 1930s reveal its lack of control and the complicity of an emerging Asian art market in destroying temple sites.Footnote 63 In January 1926, newspapers reported that five American tourists had damaged a relief of Borobudur. A subsequent, thorough inspection of the temple by the Archaeological Service, and comparisons with pictures taken during Van Erp's restoration, showed more damage caused by others.Footnote 64 Coming back from Central Java in January 1937, director F.D.K. Bosch wrote to his friend and successor, the Dutch archaeologist W. F. Stutterheim, “Just returned from Borobudur, where people have been hacking and chopping again. This time a Sundanese [of West-Java] and a Javanese: they wanted oleh-oleh [presents],” he added jokingly, warning Stutterheim not to make the case public since to do so would expose the weakness of the Service's surveillance at Borobudur.Footnote 65

Nor was the Archaeological Service itself above trading Hindu-Buddhist antiquities to other parties who self-identified as “Friends of Asian Art.” It was in charge of inventorying antiquities and selecting which sites were appropriate for conservation or even reconstruction, and it also decided whether objects could be sent overseas, as gifts, or on a long-term loan, by categorizing these as “duplicates” or because their exact provenance was unknown. In this way, in 1931, the Archaeological Service decided for the fate of twelve loose sculptures located at the Prambanan site, gifted on a long-term loan to the Vereniging Vrienden voor Aziatische Kunst (Friends of Asian Art, VVAK, founded in 1918) in Amsterdam, and its soon to be opened new museum of Asiatic art. Today the sculptures are still on display in the Netherlands, in the Rijksmuseum's Asian Pavilion.Footnote 66 All the examples of site-destruction mentioned here reflect not only a growing market for these “moveable” antiquities but also patriotic and paternalistic concern, weakness, and complicity on the part of the Archaeological Service.

Meanwhile, around 1900, Java's Hindu-Buddhist sites became better known internationally, connecting the networks of scholars, local elites, pilgrims, collectors, and intellectuals from Asia and the West, within a context of rising nationalism, transnational religious revival movements, and multicentered forms of pan-Asianism. These networks, feeding into a new Asian art market that set the standards of valuation, helped situate Javanese moveable antiquities, and thereby Java and (Hindu) Bali, in moral geographies of Greater India, albeit with different centers.

WHOSE ASIA IS ONE?

In June 1899, Borobudur and the nearby ninth-century Hindu-temple complex of Prambanan in Central Java hosted the French Mission archéologique de l'Indo Chine, founded in Saigon the previous year. This mission was the first of a series of institutional research missions-in-exchange between colonial Java, Indochina, and India. It was prompted by the hypothesis that Indochina's civilizations, in particular the kingdom of Champa (second–fifteenth centuries), via India, owed much to Java: “son origine, sa religion, et ses arts” (its origin, its religion, and its arts).Footnote 67

Newer in the field than other European Asiatic Societies, the Mission archéologique was founded for the good of a Greater France and in conscious competition with research taking place in older European colonies in Asia. By the end of 1899, it had changed its name to Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO) and in 1902 it moved to Hanoi. In its founding charter, the EFEO formulated its aim as to study the archaeology and philology of Indochina and “neighboring civilizations” in “l'ensemble des pays d'Extrême-Orient” (the cluster of countries of the Far East).Footnote 68 At the first Orientalist Congress it organized in Asia, in Hanoi in 1902, it legitimized this aim by declaring Asia a “civilizational” unity.Footnote 69 “The geographic situation of Indochina, the variety of civilizations to be found here, the mingling of races and languages, religions and arts that has taken place here, mark it out as a natural home for all research on East Asia, from India to Malaysia and Japan.”Footnote 70

This vision of the region as “one” placed French Indo-China at its center. It suited the EFEO's diffusionist (and then dominant) interest in the origins and flows of ancient Indian civilizational influences in the region, from what was then called “India proper,” in “Further India,” which encompassed today's South and Southeast Asia.Footnote 71 It implied more than just a field of study: it had moral-political implications since it seeded site-based ideas about the differentiated beauty of “Asian civilization,” and hierarchies between its divisions in terms of their origin, diffusion, importation, and deviation and/or (poor) imitation and thus decline. From this perspective, Indologist Louis Finot, the EFEO's first director, wrote that Panataran temple in East Java represented a stage “plus avancé” and was a prototype for studying temple art of Champa.Footnote 72

In 1903, the Japanese intellectual and art-connoisseur Okakura Tenshin, in his The Ideals of the East, likewise declared “Asia” as “one.” His message was famously received as the dawn of a new age amongst cultural elites in wider Asia.Footnote 73 Okakura based his ideas of a unity of Asia on the same domain as did the French, but he referred to it as “the great civilizational arts of China and India,” reflecting “the aesthetic values of Buddhism.” Okakura's Asia, moreover, had different moral centers. Ancient Vedic India played an honorable role as “the motherland” of all Asiatic thought and religion.

Through his connections with art collectors and Japan aficionados in Boston, Okakura became an advisor for collectors of “Asian art” in Europe and the United States. In 1904, he was invited to catalogue the collection of Chinese and Japanese paintings of the new and prestigious Boston Museum of Fine Arts (a civil initiative founded in 1876).Footnote 74 This museum would soon develop a strong interest in “Indian” art as well, within which it included art of Java. Starting in 1917, the year Lankan-English intellectual and art-critic Ananada K. Coomaraswamy, at the advice of Okakura, became its curator, this museum hosted a set of objects originating from the Netherlands Indies/Indonesia, collected and displayed in Greater India framing.Footnote 75

In the same inspiration, Okakura would, for a time, become a good friend of another famous thinker, the internationally adored Bengali poet, philosopher, and globetrotter Tagore, Asia's first Nobel prize winner (in 1913), who briefly associated with the Greater India Society. Like Okakura, Tagore situated the heart of Asian civilization in India. Unlike Okakura, Tagore would, in 1926 and 1927, travel southeast from India to visit Malaysia, Indochina, and the Netherlands Indies, which he recognized as “India beyond its modern political boundaries.” He thereby incorporated this wider region into his idea of Greater India.Footnote 76

Some scholars have discussed Tagore's journey to the Netherlands Indies as an example of his cosmopolitan and mobile way of life. Others, including this author, have also pointed to the rather exclusive Greater India mindset by which it was driven.Footnote 77 Moreover, while Tagore may have heralded a more inclusive vision of the character of Asian civilization than Okakura did,Footnote 78 he emphasized the high value of ancient Hindu-Buddhist India, not Islamic India, as its unifying force. Prepared by an encounter with Bali-afficionados in Amsterdam and a visit to the colonial museum there during his stay in the Netherlands in 1920, Tagore longed to see Bali and its Hindu population as the remainder of a pure India. Writing about the Balinese, without ever having met them, he inferred, “These people, who had their seclusion that saved their simplicity from all hurts of the present day … have, I am sure, kept pure some beauty of truth that belonged to India.”Footnote 79

In September 1927, the sixty-six-year-old Tagore traveled to Bali, where he was disappointed by the lack of modern comforts, and to Java, where he admired the temples (Fig. 7). At Borobodur, as he wrote in his poem of the same title, he was while looking at it overwhelmed with a deep sense of loss: of Buddha's gift to the world and thus ancient India's message of “immeasurable love.”Footnote 80 In 1928, apparently still overwhelmed by his impressions, Tagore wrote to a friend that his visit to Java and Bali had filled him with the wish to send Indian scholars to that region to study and to help recover these “neglected and forgotten outposts of Indian civilization … for our own enrichment and for the benefit of the inhabitants.”Footnote 81 And indeed, in the late 1920s some members of the Greater India Society did gather data in Java and publish histories that depicted the archipelago as ancient colonies of a wholesome India.Footnote 82

Figure 7. Borobudur, with some of its famous visitors, September 1927: Rabindranath Tagore (in rear), accompanied by (to his right) Keesje Bake Timmers (wife of Indologist Arnold Bake), and his company from Santiniketan: the linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji (to his left), painter and musician Dhirendra Krishna Deva Varman (front, second from left), and architect Surendranath Kar (front far right). Also in the front (far left) are the Dutch social-democrat Sam Koperberg (secretary of the Java Institute), and, representing the Netherlands Indies Archaeological Service, Dutch archaeologist Pieter Vincent Van Stein Callenfels (second from right). Photograph by Arnold Bake. (University Library Leiden, KITLV Collection, Collection Bake).

ART OF GREATER INDIA—A MATTER OF UNDERSTANDING

In 1918, the Metropolitan Museum's Bulletin published a description of the above-mentioned Borobudur Buddha head it had bought from the art-collector Kelekian. The author, a certain “J. B.,” recognized it as a proof of “Indian genius”: “It is to native Indian genius that we owe the familiar type of Buddha, the Enlightened One, the type which is so superbly illustrated in addition to our collections of Asiatic art.”Footnote 83 Borobudur, he said, was a “conspicuous” example of “the masterpieces of Indian art of the classic period.”Footnote 84

With this kind of connoisseurship, not extraordinary at that time, J. B. identified with a remarkable international movement of art historians, connoisseurs, and collectors who, from the 1910s, came to qualify religious sculpture made in Asia as Indian Art with capital A, of the highest Western standards. They were inspired by new and influential art theories that emphasized the Asian sculptures’ capacity to visualize the divine. Aesthetics-cum-divinity became a powerful motif for evaluating ancient religious sites in Asia, whether they were still in use or not, and carrying away objects from them to museums in Asia and the West. We shall see that a Buddha statue from Borobudur came to play a decisive role in this taxonomic shift, both inside and outside of the museums, which helped place moveable antiquities from Indonesia into moral geographies of Greater India.

As Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Parta Mitter have shown, around 1910 a new trend emerged in the theorizing of ancient Hindu and Buddhist sculpture with provenance in Asia, conceived as high art. It found fertile ground in Asia and the West alike through the highly-influential works pioneered by Ananda Coomaraswamy and Ernest Binfield Havell (1864–1937).Footnote 85 Havell had served as superintendent of the Madras School of Arts (1884–1895) and then at the Government School of Art in Calcutta, before he returned to England in 1906, where he published his most influential works. Coomaraswamy, born of Lankan and English parents, presented his views around 1908 to an international public. Through Okakura, he became the first curator of the new “Indian Section” of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where he enjoyed a guru-like status.Footnote 86 In a pilot study, I explained how the theories of these two intellectuals not only entailed new evaluations of Hindu-Buddhist antiquities from Asia as expressions of “one” Greater Indian civilization, but also helped to disseminate new, influential exhibition techniques that situated Javanese antiquities more firmly in Greater Indian views on art.Footnote 87 Most crucial to us here is that both Havell and Coomaraswamy, charmed by the circle around Tagore in Calcutta, placed artistic expressions in Asia under the rubric of Indian art. From this India-centered perspective, both men further argued that Indian art should be appreciated as high art in its own right, and not as a derivative of Greek and Roman standards. The latter view had become commonplace since the late nineteenth-century discovery of Gandharan sculpture, in which Foucher had played such an important role.Footnote 88 Coomaraswamy, at the Fifteenth International Oriental Congress in Copenhagen in 1908, reasoned that Indian art, with its capacity to conceptualize the divine, was decidedly superior to European forms, where the “gods are but grand and beautiful men.”Footnote 89

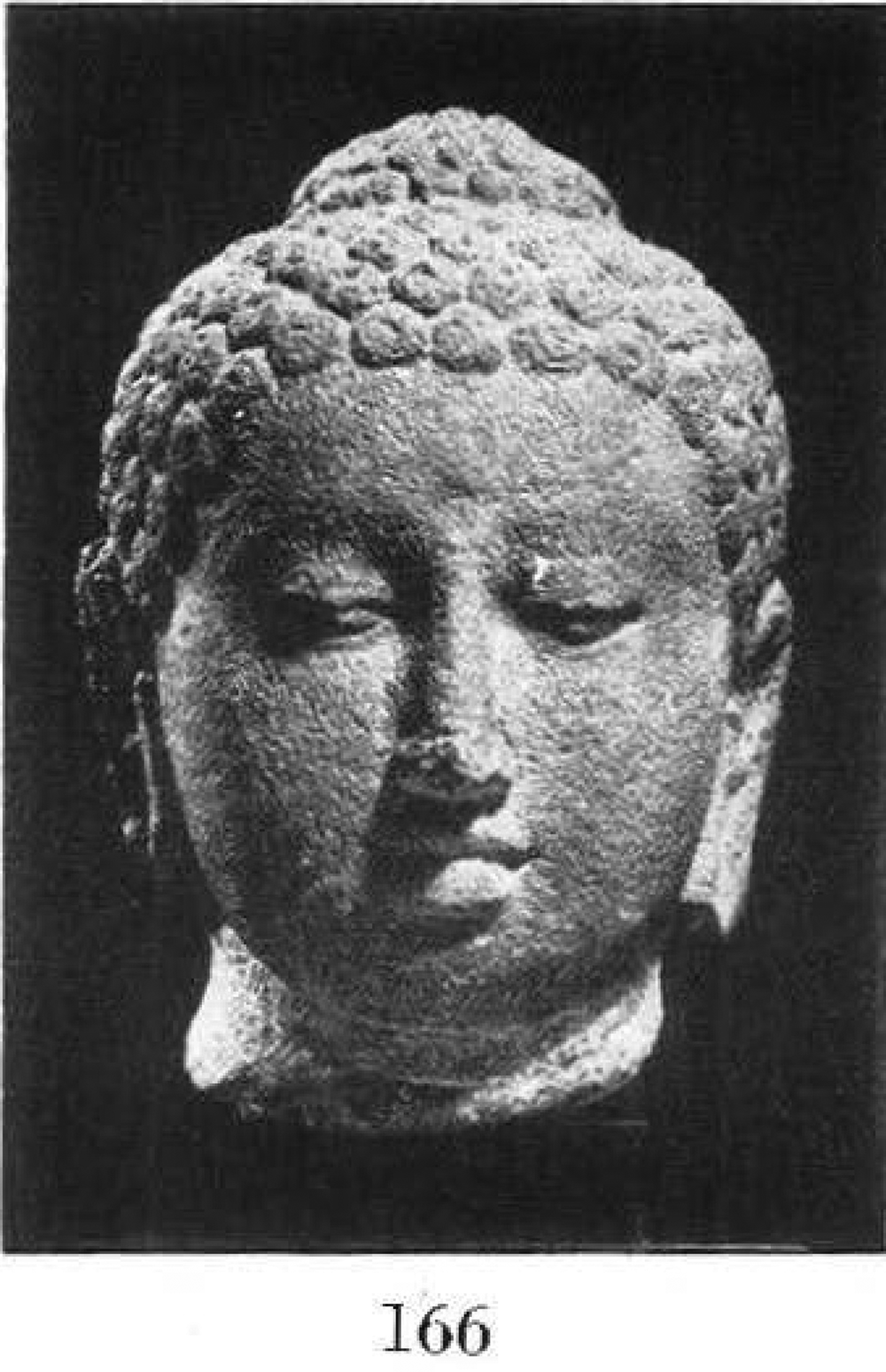

Havell, in his standard work Indian Sculpture and Painting (1908), chose one of the Buddha statues from the north side of Borobudur to make the same argument: “How beautiful it is when the spiritual rather than the physical becomes the type which the artist brings into view.” Though his example was located in Java, Havell concluded that the art was most assuredly “Indian.”Footnote 90 This same statue from Borobudur (or its photographic representation in Havell's book (Fig. 8) sparked a heated dispute at the Indian Section of the Royal Society of Arts regarding its “artistic quality.” This debate underscored the fate of Hindu-Buddhist antiquities originating from Indonesia in the transforming world of Asian art networks and marketing. The Royal Society's chair, Bombay-born naturalist Sir George Birdwood (1832–1917), who was a great defender of what was then referred to as Indian “applied arts,” condemned the statue as an “uninspired brazen image.” He added, “A boiled suet pudding would serve equally well as a symbol of passionate purity and serenity of soul.” This qualification, made public in the Royal Society's journal, incited a manifesto in the Times of 28 February 1910 signed by the prominent painter, art-critic, and India aficionado William Rothenstein (1872–1945) and twelve like-minded artist-critics, which sealed the statue's taxonomic future and prepared the foundation of the India Society. To the signers, the Buddha of Borobudur stood for the supreme embodiment of the central religious and divine inspiration of Indian art, which was “one of the great artistic inspirations of the world.”Footnote 91

Figure 8. “One of the great artistic inspirations of the world.” The disputed Buddha Statue from Borobudur, Photographer unnamed. Published in Havell Reference Havell1908: 28.

Tellingly, neither in the contemporary disputes over the appreciation of Asian art that followed, nor indeed in the critical historiography of this alteration in the evaluation of Hindu-Buddhist material remains—from “malign” to high art—does one encounter anyone questioning of the label “Indian.”Footnote 92 In the context of this inventive moment and the celebration of Greater Indian art, as well as of Asia-based nationalism, from the 1910s onward cultural and economic elites in Asia, Europe, and the United States began to engage with new academic and private associational activities while self-identifying as “Friends of Asian Art” and “Friends of Asia.” Protagonists, amongst them theosophists, proliferated as modern, avant-gardist connoisseurs of art. Others were esteemed academic experts on ancient Asian languages, archaeology, or cultures. These associations reflected a globally connected, powerful movement of Greater Indian thinking that fed into colonial and intercolonial networks of knowledge. Examples include the India Society, founded by Havell and others in London in 1911; the Vereniging voor Vrienden van Aziatische Kunst (Society of Friends of Asian Arts, VVAK), founded in Amsterdam in 1918 by the publicist of modern art H.F.A. Visser with the support of Rijksmuseum Director F. Schmidt-Degener, and the Association Française des Amis de l'Orient, founded in 1920 at Musée Guimet with Indologist Emile Senart (1847–1928) and Sylvain Lévi as vice-president and secretary, respectively. This era also saw the establishment of new academic institutions directed toward the study of the civilization of “Greater India”: the Instituut Kern in Leiden, founded in 1926 by Sanskritist Jean Philippe Vogel with the support of archaeologist and director of the Netherlands Indies Archaeological Service F.D.K. Bosch, and the Institut de Civilisation Indienne in Paris, founded in 1927 by Sylvain Lévi. Last but not least, back in the Netherlands Indies, a group of Javanese cultural-nationalist elites and Dutch colonial (self-made) scholars of Javanese culture in 1918 founded the Java Instituut in Surakarta. Among the many relevant associations in British India that made efforts to connect with this movement were the Greater India Society and the Indian Society for Oriental Art. The latter published a journal and was run by the fiercely nationalist and Greater India-oriented art historian C. O. Gangoly.Footnote 93

These associations shared powerful honorary members. Coomaraswamy is on many of their lists. The Javanese prince Mangkunegara VII, patron and collector of Javanese antiquities, was not only chair of the Java Instituut but also an honorary member of the India Society. His friend, the Dutch archaeologist Stutterheim (who would become head of the Netherlands Indies’ Archaeological Service), promoted the India Society in both the Netherlands Indies and the Netherlands, despite making some ambiguous criticisms of Greater India thinking.Footnote 94

The India Society, helped by a governing language, endeavored to play a key role in the Friends of Asian Art movement. One of its first publications, in 1912, was Tagore's own English translation of a portion of his lyrical, Veda-inspired poetic writings in Bengali, “Gitanjali,” with an introduction of the by then already world famous and influential poet W. B. Yeats.Footnote 95 One year later this publication brought Tagore the Nobel prize, partly thanks to lobbying by charmed and influential intellectuals and artists he had befriended in Europe. In the 1920s, the India Society hosted and published lectures by international scholarly experts on the wide region of Asia, for which Dutch scholars such as Vogel, Stutterheim, and Visser, the secretary of the Dutch Society of Friends of Asian Arts, were invited as well. They were all asked to discuss the influence of India on the arts of the sub-region of their expertise.Footnote 96 The India Society's volume Revealing India's Past (1939), from which Foucher's reflections in this article's introduction were taken, also brought together many internationally admired scholars of the field.

What matters here is how these associations, at least those developing in the West, firmly shared a belief that the collection, study, and united display of Asian (read “Indianized”) arts, and contemplation of the civilization in which they could flourish, would benefit the West and the East—it would be good for both empire and Asian nationalist self-esteem. In a 1931 letter to the Times, board-members of the India Society used this argument to defend their long-standing (but never realized) plans for a central Museum of Asiatic art in London: “Sir, … the international value of a Central museum for Asiatic art raises a matter of great importance to the British empire and in fact the world.… [T]hroughout Asia & especially in India, art has been the means by which the deepest convictions of humanity have … found expression. The study of art of Asiatic people is as necessary as that of their literature, if we are to understand them and appreciate their present aspirations.”Footnote 97

Foremen of this Friends of Asian Art movement in Europe came to believe that the understanding and appreciation of this (superior) spiritual Oriental “civilization,” perceived as essential to a people or race, and including its spiritual art, was a condition for world peace and reciprocal understanding.Footnote 98 To achieve these aims, they called for the further study and collecting, and the popularization of the arts and the civilization of Asia, which they defined as spiritual, peaceful, and Indian. They thereby presumed, and identified with, a global as well as Indian nationalist need for Asian (Greater Indian) art museums.Footnote 99

CHARMED ACROSS DECOLONIZATION

The idea of an Asiatic museum in London never materialized, probably because it could not compete with the Victoria & Albert Museum and the British Museum, which fostered their own Hindu-Buddhist treasures, which were reframed in the 1930s under comparable ideals of universal understanding.Footnote 100 Modern museums of Asian art did take shape elsewhere in Europe. The modern galleries of Musée Guimet, developed in the 1930s under curator Philippe Stern, provide one example;Footnote 101 another is the Rijksmuseum's Asian art collection, today on display in its new (as of 2013), white, serene Asian Pavilion (Fig. 9). The greater part of this collection is owned by the VVAK, kept as such in the Rijksmuseum since 1952, and as a long-term loan since 1972. It goes back to the VVAK's Museum of Asiatic Art that in 1932 opened in the Museum of Modern Art in Amsterdam (the Stedelijk Museum, City Museum). At that 1932 opening, VVAK's secretary Visser spoke of the wholesomeness of understanding Asian art as something that would better the world. He dwelled on the ideals of Okakura, Coomaraswamy, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and on debates he had attended at the India Society in London.Footnote 102 The Friends of Asian Art were charmed and connected via their esteemed, modern institutions and associations in the United States, Europe, and Asia, and built on the trending theorization of Asian art in their collecting and exhibiting activities. In this way, they built up a strong base for the imagination of Hindu-Buddhist antiquities from Asia (including Indonesia) as art of Greater India. This imagination became useful again after World War II and the formal independence of the formerly colonized countries in Asia.

Figure 9. First room of the Asiatic pavilion of the Rijksmuseum, showing “a selection of arts from Asia,” starting here with South and Southeast Asia, then Pakistan and India (on the left) and Indonesia (on the right, and on the wall in the back). Most of the Rijksmuseum's “arts from Asia” collection is on loan from the VVAK. Author's photo, September 2020.

In the 1950s, the newly independent Republic of Indonesia once again became part and parcel of “Art of Greater India” exhibits, supported by Indian Embassies in several places in the world. To all indications, for their curators the categorization remained unproblematic. One such exhibit was held at the Los Angeles County Museum in 1950.Footnote 103 Organized by the museum's German curator Henry Trubner, it was introduced by a map of “Greater India,” and displayed loans from private and museum collections in the United States (the majority), Canada, and Europe (Figs. 10 and 11). Indonesia was represented as “Java,” and exclusively by ancient Buddhist objects from American collections.Footnote 104 Formed by his studies of Oriental Art at Harvard University, Trubner in his introduction to the catalogue followed Coomaraswamy's idealist theorizing, explaining how the exhibition's visitors should appreciate Indian art differently from Western art, as objects made not exclusively to please “aesthetically” but “to satisfy a spiritual need.” Indian art was “not to be judged subjectively on the basis of its outward beauty but primarily … to be an aid in bringing to life the deity represented, acting as intermediary between the worshipper and the invisible divinity.”Footnote 105 He thus suggested the possibility of spiritually connecting with this form of art through empathy.

Figure 10. Map of Greater India. From Henry Trubner 1950a: ii. Courtesy Museum Associates/LCMA.© Museum Associates/LCMA.

Figure 11. Buddha head from Borobudur, lent by the All Bright Art Gallery, Buffalo, on display at The Art of Greater India exhibition in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1950). Figure from Trubner Reference Trubner1950b: 259. Courtesy Museum Associates/LCMA.© Museum Associates/LCMA.

This exhibition and its catalogue are enlightening regarding how moral geographies of Greater India can become etched in people's minds: powerful tools toward this end were the map of Greater India, which framed all objects on display, and the way Trubner defended the initiative: “Today … sincere efforts are being made to bring about closer relations between the East and the West, it is important that we attain knowledge of India's great cultural past and realize the tremendous role that country has played in the history of Far Eastern art. The immediate purpose of the exhibition is to bring about an unbiased and true appreciation of Indian art and a deeper understanding of India's great heritage.”Footnote 106

So much for the heritage of the other new independent nation-states, the borders of which were obfuscated on the map of Greater India, and whose people were working at home, in parallel, on nation-building through cultural politics. Ironic here is President Soekarno's December 1953 inauguration of the reconstruction of the Siva temple at Prambanan as Indonesia's first national monument, a project initiated by the colonial Archaeological Service in the 1920s. In the country's National Museum in Jakarta, formerly the museum of the Batavian Society, the Hindu-Buddhist antiquities collected and abducted in the archipelago since colonial times emphatically tell the history, not of India, but of Indonesia.Footnote 107 Nonetheless, in museums outside of Indonesia, from Los Angeles to Calcutta, Amsterdam to Paris, Hindu-Buddhist temple remains from Java still serve narratives of a Greater India.

The study and collection of Indonesian antiquities by the seekers central to this article may have been driven by love, inclusiveness, or motives of peace through cultural understanding. But their search also reveals the potential that love has to spawn epistemic violence and appropriation. Fauque, informed by Western theories of civilizational progress, recognized a transformative civilizational moment in the Islamic stiles in Aceh as beauty. The Friends of Asian Art, captivated by Coomaraswamy's and Havell's theories, identified the Indian artist's capacity to visualize the divine in what were, to them, self-familiar images of a meditative man. Through this kind of self-understanding, and through their networks, and by means of text- and object-based interpretations, sales, and exhibitions, the Friends of Asian Art, whether due to Indian nationalist ideals, art-historical connoisseurship, or a longing for world peace, contributed to the global spread of moral geographies of Greater India, with Indonesia situated therein. Multi-sited and varying in form and outlook, these moral geographies entailed exclusion—a steadfast blindness regarding Indonesia's predominantly Muslim population, which had so many other pasts to identify with beyond those of Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms and mandalas labeled as Indian, Indianized, or Indic.

This article warns of the dangers and distortions that transpire from transnational, civilizational-cum-spatial framings of Asia, or any other region, as a homogenized and exclusive field of study. It also alerts us that grounding research and the collection of knowledge, including knowledge of art, in “sympathy” or “affection” will not guarantee truer understandings of “other” people's cultures, histories, and memories.