William F. P. Burton's career straddled several worlds that seemed at odds with each other. As a first-generation Pentecostal he pioneered, with James Salter, the Congo Evangelistic Mission (CEM) at Mwanza, Belgian Congo in 1915. The CEM became a paradigm for future Pentecostal Faith Mission work in Africa, thanks to Burton's propagandist writings that were published in at least thirty European and North American missionary periodicals. His extensive publications, some twenty-eight books, excluding tracts and articles in mission journals, reveal that the CEM was a missionary movement animated by a relentless proselytism, divine healing, exorcism, and the destruction of so-called “fetishes.” The CEM's Christocentric message required the new believer to make a public confession of sin and reject practices relating to ancestor religion, possession cults, divination, and witchcraft. It was a deeply iconoclastic form of Protestantism that maintained a strong distinction between an “advanced” Christian religion, mediated by the Bible, and an idolatrous primitive pagan religion. Burton's Pentecostalism had many of its own primitive urges, harkening back to an age where miraculous signs and wonders were the stuff of daily life, dreams and visions constituted normative authority, and the Bible was immune to higher criticism. But his vision also embraced social modernization and he preached the virtues of schooling and western styles of clothing, architecture, and agriculture.Footnote 1 It was this combination of primitive and pragmatic tendencies that shaped the CEM's tense relations with the Belgian colonial state.

Burton was also one of a number of missionaries who found non-western cultures fascinating and who moved from their institutional settings to engage in scientific research, in his case, on the Luba speaking peoples of Katanga.Footnote 2 He collaborated with scholars from the Central Africa Museum in Tervuren, Belgium and the University of Witwatersrand in producing works of salvage anthropology about the Luba. He collected material culture and conducted ethnographic surveys. In keeping with the functionalist anthropology of the day, his research rendered the Luba in pristine condition untouched by the transformations of Belgian colonial capitalism. His studies focused on Luba religion and magic, proverbs and folktales, and have been used by two generations of historians and anthropologists working on the Luba.Footnote 3 While some of his writing was sympathetic, arising out of a curiosity and respect for what he encountered, his prose was littered with pejorative, even contradictory statements. He wrote with disdain about what he viewed as idols and fetishes, and condemned what he believed to be the brutish and debauched practices of so-called “secret societies.”Footnote 4 He often failed to recognize the ontological similarities between his own Pentecostal practice and the “heathen superstitions” with which he did spiritual battle. Burton also took hundreds of stunning photographs that he sent to Tervuren and to the embryonic Social Anthropology Department at the University of Witwatersrand. Other photographic images were used to illustrate missionary publications and were turned into magic lantern slides, adding a powerful new but unacknowledged visual component to Pentecostal religion, which supplemented the Bible as a source of revelation.

This essay on Burton's photography takes as its starting point the pioneering work of Paul Jenkins, who has convincingly demonstrated how photographic images can be used to expand understanding of the missionary encounter. Jenkins argues that photography allowed missionaries “a greater freedom” to pursue their interest in non-western cultures than did verbal reports to the “guardians of orthodoxy at home.” Indeed, photographs taken by missionaries can show a far more complex attitude towards their subjects than the simple oppositions that evangelical prose usually allowed.Footnote 5 The essay explores the multiple roles of missionaries, analyzing how different photographic genres mediated their often-contradictory positions. In so doing, it offers new insight into missionary aesthetics, as it was situated at the interface of different genres and their audiences, which ranged from supporters of mission to museum curators and social anthropologists.

In what follows, I draw upon recent methodological and interpretive developments in work on photography which have “moved away from a concern with representation per se in favour of the more complex discursive and political landscapes opened up by the concepts of media and the archive.”Footnote 6 As Elizabeth Edwards has argued with regard to anthropological photography, images are not mere representations of things but cultural objects with their own “social biographies.”Footnote 7 Their meanings are framed by the “different institutional, regional and cultural sites”Footnote 8 through which they move and by the actions of individual photographers.Footnote 9 Burton's photographs have a long and fascinating biography and in recent years have come to be viewed primarily in artistic terms, used in high-profile exhibitions to illustrate and expand notions of Luba figurative art.Footnote 10 However, this essay will restrict itself to their production and early circulation and consumption. In this opening stage of their trajectory, Belgian museum curators used them in the colonial enterprise of mapping tribes, they provided a material basis to an emergent South African social anthropology, and they were powerful media within missionary work. Burton made his images within well-established artistic and photographic genres. His interactions with his mission administrators, curators, and academics are well documented, and by combining this knowledge with fieldwork, and analysis of his published texts and correspondence, it is possible to gain a rare understanding of his aesthetics and the early meanings attached to his images.

“Photographic practices” is another of my themes here.Footnote 11 Although missionary and anthropological photographs were created in a power relationship within a colonial situation, there is a need to consider “the ‘photographic event’—the dialogic period during which the subject and the photographer come together” in which “lengthy negotiations under conditions of elaborate technical preparation” take place.Footnote 12 Such insights remind us that while “photographs are contrived and reflect the culture that produces them,” “no photograph is so successful that it filters out the random entirely.”Footnote 13 Burton's images, in particular, show human countenance, intimacy, and contingency making their presence felt.Footnote 14 Thus an examination of Burton's photography captures some of the tensions that surrounded his attempts at knowledge formation, and extends understanding of the range of his encounters with the Luba, offering an alternative history of the personal role of missionaries in colonial states.

The largest collection of Burton's photography, a set of 424 images, is located in the University of Witwatersrand. Most of the photographs, 325, are mounted on pieces of yellow card, with captions and comments on the back taken from notes he provided (Burton Photo Collection, henceforth BPC); the other ninety-nine are fixed in an album (henceforth AL), numbered in sequence and accompanied by a handwritten information sheet.Footnote 15 It is difficult to date the reception of the photographs at Witwatersrand because a fire in 1928 destroyed much of the early correspondence, but Burton commenced taking the album prints around 1923, while the mounted photographs date from the early 1930s. A second collection, in the Central African Museum (Musée Royal de l'Afrique Centrale: MRAC) in Tervuren, Belgium, is a set of approximately 174 photos (ref: EPH), along with thirty-four gouache paintings of coiffures and headdresses produced in the 1920s and 1930s. The Tervuren photographic collection was received as two sets, the first in 1928, and the second in 1935–1936. The photographs are assigned these dates although many were taken before 1928. A good number of the Tervuren photographs are also found in the Witwatersrand album, or closely resemble images in it, and were doubtless the “second shot” that well-trained photographers took as a matter of course. Lastly, there is a collection of photographs, quite different in nature, located in office of Central African Missions (CAM) (formerly the CEM) in Preston, England. There are the tattered remains of an album of 176 ethnographic photos. These are hidden away in a drawer because the Mission's successive administrators did not quite know what to do with the images of nudity. There are also two small wooden boxes containing approximately 163 glass slides. The CAM collection provides the greatest range of photos, including personal images and scenes of mission work as well as what Burton called “ethnographic” pictures.

Pentecostal Encounters with Photography

Burton's encounter with photography was shaped by a number of countervailing impulses. His Pentecostal conversion made him a deeply committed and driven man. He was moved by a sense of the truth, a faith in the redeeming work of Christ and the relevance of the miraculous in his own age. Like many radical evangelicals, he held a deep-seated Protestant suspicion of materiality. Religious mediation by a priesthood, clerical garments, church buildings, and religious festivals such as Christmas and Lent were expressions of the “satanic anti-God religion of Babylon” represented by Rome and her “harlot daughters”: Anglicanism and Methodism. The Bible alone was the believer's “guide.”Footnote 16 He would respond to “pagan idols” with equal vigor. Nevertheless, he believed that photographs and slides could show the transformations of modernizing mission Christianity and inspire believers at home. Unlike adventurers and missionaries working in the period of colonial occupation, Burton did not use photography as a form of magic to evoke fear or submission.Footnote 17 Instead, photographs recorded “signs following” the proclamation of the gospel. Indeed, inside the cover of a popular tract by Burton of this title is found his favorite set of visual illustrations, neither missionary or ethnographic photos, but two X-ray slides showing the “authenticated healing” of his cancer of the colon.Footnote 18 Here modern scientific technology was used to demonstrate divine healing.

The ease with which Burton appropriated modern technologies sprang from the strong pragmatic tendency within Pentecostalism “to do whatever is necessary in order to accomplish the movement's purposes.”Footnote 19 For a brief moment following his conversion he renounced all sources of knowledge save the Bible. But this constricting aspect of his post-conversion zeal had disappeared by the time he entered Belgian Congo, enabling him to draw upon his already developed sense of aesthetics, visual technologies, and colonial science to further his missionary work.Footnote 20 As we shall see, his research and photography also acted as a mode of scientific “witch-finding” that accompanied Pentecostal practices of witch-cleansing and exorcism.

Burton's embrace of the tools and scientific disciplines of modernity was shaped by pre-conversion upbringing that was distinctly upper middle class. He was born in March 1886 in Liverpool, where his father was Commodore of the Cunard Fleet. His mother, whose maiden name was Padwick, was related to the aristocratic Marlborough family of Shrewsbury. He benefited from a private education at St Laurence College, Ramsgate. At age seventeen Burton took an engineering course at Redhill Technical College and then moved to Preston, Lancashire, where he worked for General Electric, completing a Degree in Engineering at Liverpool University. He gradually entered the world of radical evangelicalism that would lead him and many others into Pentecostalism. In 1905 he attended the London revival campaigns of Torrey and Alexander and was deeply moved by them. Soon after his move to Preston he experienced a dramatic conversion and began attending the Keswick Conventions, which impelled him to search for a greater sense of holiness and an empowerment by the Holy Spirit. Around 1909 he heard of the Pentecostal outpourings in Azusa Street, California, and joined a group of pious believers in Preston who sought the gifts of tongues and prophesy through prayer and Bible study. In 1911 Burton was baptized in the Holy Spirit. He renounced engineering and took up a peripatetic existence, walking great distances across Lancashire and the Yorkshire Pennines, holding meetings in cottages, and preaching on village greens. Driven by belief in the imminent return of Christ and the need to proclaim the full Pentecostal message of salvation, he looked for opportunities to serve as a missionary and in 1914 traveled to Belgian Congo via South Africa.Footnote 21 The following year, Burton and Jimmy Salter founded what was to become the CEM at Mwanza on the upper waters of the Lualaba in south east Belgian Congo. Between 1917 and 1925, more than thirty other like-minded missionaries joined, vastly expanding the mission's reach across the entirety of the former Luba polity. It would also spread into Songye-speaking areas and later into towns and cities. By the year 2000, it had five hundred thousand members in three thousand assemblies in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).Footnote 22

In March 1918 Burton went to South Africa to recruit more missionaries and to marry Hettie Trollip, a young woman from a respectable farming family in the Cape who were members of the Pentecostal Apostolic Faith Mission.Footnote 23 In 1922 Salter left the field to run operations from England. Henceforth, Burton acted as secretary and répresentant légal of the CEM. As effective head of the mission he was not only responsible for evangelizing the villages around Mwanza but for oversight of the entire field. He fulfilled his duties with great energy and in his early days he would trek two to three thousand miles a year on foot, cycle, or canoe, preaching and healing. The Luba called him Kapamu, the Rusher Forth. He also took responsibility for raising finances. As a faith missionary he simply made known the CEM's activities and believed that God would supply their needs.

The primary means of mission propaganda was the Congo Evangelistic Mission Report (CEMR) printed in Preston, England from 1923 onwards. Prior to that, the Mission's activities had been publicized by ad hoc Reports of Work printed and disseminated by the Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa. Both publications were written, edited, and compiled in the field before the copy was sent to Preston for reproduction. Thus the CEMR differed considerably from other missionary magazines in that it had almost no home news or doctrine but rather a very strong local focus on missionary engagement with Luba culture. Burton acted as editor until 1935, even when on furlough.Footnote 24 He wrote 50 to 70 percent of the material himself, reproducing news and stories he had collected whilst on trek or from missionaries who passed through Mwanza.Footnote 25 The secondary means of propaganda was longer inspirational works: booklets and books providing histories of the mission, hagiographies of evangelists, compilations of Luba folklore, and sketches of Congo life.

Between 1921 and 1922, when the Burtons went on a lengthy furlough to Europe and the United States, William discovered the power of the photographic image. In May 1923 he wrote to Salter explaining his rationale: “As you know, there are many who do not have much time for reading, but like to look through the pictures, and will be drawn into prayer by them. Under such circumstances I feel that we should not stint the paper for good snaps.” Ten months later he reflected on the immediate success of the endeavor: “I feel that photographs will make all the difference to the magazine, and should not by any means be cut down five or six per number. Already folks have remarked on the PICTURES and I hope to spare no pains to send good ones.”Footnote 26 The regular bi-monthly CEMR, launched in July 1923, consistently contained photographs, some of them striking. Burton was aware of the high standard of his photography and its potential as a money-spinner: “I have really good secular copy and snaps here. They will probably sell well. But I have not got the address of home firms or papers that will take them. I should be grateful if you would send me a few addresses of Magazines such as Strand, Wide World, Windsor, Times Weekly … etc.”Footnote 27

Burton's photography drew from a number of genres: missionary, colonial, and anthropological. These overlapped but also had distinguishing themes and content. Most significantly, he participated in the well-established tradition of missionary photography. The CEMR occasionally published photographs by American Methodists and American Presbyterians, and these movements were pleased to receive his high quality photos, sketches, and paintings in exchange.Footnote 28 Burton learnt a great deal from his friend and missionary neighbor Dan Crawford, who also happened to be a photographer of some ability.Footnote 29 The CEMR images, and lantern slides that were shown to hundreds of church audiences by missionaries on furlough, were propaganda that Burton hoped would pique curiosity, shock, and stimulate in a manner that would cause readers to pray for or donate to the mission and perhaps consider a vocation as a missionary or fundraiser. They represented one of the first of many Pentecostal appropriations of the visual media. The intention was not just to broadcast the message but also reconfigure religious ideas and practices in the process, representing “new opportunities for public articulation and self-representation.”Footnote 30

The missionary genre shared many tropes with photographs used in colonial publications and exhibitions. There were images of the construction of roads, railways, and bridges to record the material progress associated with missionary and colonial presence. Other photos of schools, hospitals, and western clothing illustrated the shared mission of “civilization.”Footnote 31 Specifically religious ones showed filled churches and packed baptismal services as evidence of the popular affirmation of the missionary message. Shots of nuclear families outside brick houses demonstrated western Christian ideals of monogamy and moral decency.Footnote 32

It is not clear whether Burton engaged with a particular photographic school, but he subscribed to a good number of illustrated publications. Alongside the weeklies mentioned above, he also read the L'Illustration Congolaise, a bi-monthly publication of Belgian colonial propaganda, with many photographs of exotic images and landscapes and modernizing colonialism.Footnote 33 Within Belgian Congo, he was also aware of the work of the influential Polish photographer Casimir Zagourski. Both men's images were used to illustrate one 1936 missionary publication.Footnote 34 He was also very cognizant of art and aesthetics. His mother had been an accomplished artist who had studied under the celebrated Romantic landscape painter James Thomas Linnell. She taught William the techniques of oil and watercolor, and of sketching in pen and pencil. Burton himself was a very competent watercolorist and sold hundreds of paintings of Congo landscapes to Belgian settlers to finance the work of the mission. The South African Academy accepted four of his paintings in 1938, and seven of his watercolors painted around 1929–1931 are held in Museum Africa, Johannesburg.Footnote 35 Some of Burton's village scenes and portraits resemble those painted by Léon Dardenne, artist to the Scientific Mission to Katanga from 1898 to 1900, whose pictures he would have seen on his visits to Tervuren.Footnote 36 He certainly read widely on the style and technique of painting and it is likely that he did the same for photography.Footnote 37

Engaging with Colonial Science

In the late 1920s, Burton was drawn into colonial science and extended his interests from photography into ethnography and collecting. Science was always an important source of legitimation for Belgian colonization in the Congo, as much symbolic as practical. Burton joined the enterprise to demonstrate his loyalty and utility to the Belgian colonial regime as a Protestant Englishman. He saw colonial science as a powerful tool of Protestant iconoclasm, a means of unmasking “the powers of darkness” he believed to be present in traditional religion. Research accompanied by photography made public what lay hidden beneath surface appearances.Footnote 38 In the 1929 preface to his manuscript Luba Religion and Magic in Custom and Belief, he explained:

The casual white may scarcely notice the startled cry in the darkness of the night, the small white mark upon a native's body, or the waving of a few leaves in the hand of one of his caravan porters, accompanied by a muttered spell. Yet a few judicious enquiries conducted in the right way, would lay bare a whole underworld of fearful custom, of which the white man has not even dreamed. We are convinced that for lack of such knowledge much missionary preaching is like a boxer striking the empty air instead of planting well-directed blows in the spot where they are most likely to take effect.…Footnote 39

He was also driven by a desire to preserve “tribal” culture and an appreciation of aesthetics. In 1927 he made contact with leading figures in the Central African Museum in Tervuren, Belgium. Henceforth he sent them ethnographic data, material objects, photographs, and gouache paintings of coiffures and headdresses.Footnote 40 His collecting became an act of salvage of a culture that changed rapidly after 1915.Footnote 41

Burton's interaction with the University of Witwatersrand followed a similar trajectory. He established a good friendship with Winifred Hoernlé, head of the nascent Social Anthropology Department (1923–1937), and they arrived at a system whereby the University paid for his ethnological photographs and took prints for themselves. He would send the negatives, which would be returned to him with one print, allowing both parties to build up a considerable collection of images of “interesting subjects” relating to Luba culture.Footnote 42 This exchange continued after Hoernlé left Witwatersrand in 1937. Her replacement, Audrey Richards, found Burton's photographs “so good,” and encouraged him to continue photographing and collecting.Footnote 43 Burton actively solicited advice from Hoernlé and Richards on the content and type of images they required. It is more than likely that Hoernlé directed him to the fifth edition (1929) of Notes and Queries on Anthropology, which would have been well known to her.Footnote 44

Although his photographs emerged from a unitary social field, Burton compartmentalized in terms of genre when it came to placing them. He categorized only “a dozen or so” of his negatives deposited in the CEM office in Preston as “ethnographic”—“customs, types, superstitions”—and only this kind of image would be sent to Tervuren and Witwatersrand.Footnote 45 In terms of subject matter and style, Burton followed ethnographic fashions; like many of his contemporaries, he photographed coiffures and cicatrisation, dancers and diviners, hunters and fishermen, craftsmen and their artistic productions. Subjects were usually de-individualized, reduced to “types” involved in traditional activities as “exemplars of idealized racial categories.”Footnote 46 Missionaries, adventurers, and administrators had been photographing such things since the 1880s for journals such as Le Mouvement Géographique and Le Congo Illustré, self-consciously revisiting the fascinations of Livingstone (1857) and Cameron (1877), who had included sketches of these subjects in their travelogues.Footnote 47 Burton had a particular interest with religion and magic, especially as diviners and so-called “secret societies” practiced them.Footnote 48 In contrast to his missionary photography his ethnographic material contained few images of modernity—western clothes, brick houses, bicycles and the like—and those modern objects that did impinged were usually not alluded to in accompanying commentaries. This even though throughout the 1920s and 1930s the Luba were experiencing rapid social and economic change through labor migration, urbanization, cash-crop agriculture, and modernizing Christianity.Footnote 49 His ethnographic images acted as a perfect tool of salvage anthropology, reinforcing an essential notion of the Luba.Footnote 50

Many of Burton's photographic subjects came from villages in a 30-mile radius of his station at Mwanza Sope.Footnote 51 These were places which he knew best, the sites of his missionary activity, within a day's reach on foot or bicycle. In the course of forty-five years in Belgian Congo, Burton was able to construct deep relationships with many in these villages. Even those who were “spiritual” enemies—diviners, medicine men, secret society members—could be befriended through persistent interaction. But Burton was not restricted to his own locale. Good pictures of interesting subjects were also gained through the mediating influences of his colleagues, particularly Teddy Hodgson and Harold Womersley. Both also wrote their own books and were regular contributors to the CEMR. Hodgson, who arrived in 1920, pioneered the CEM at Kikondja, working amongst the fishing villages of Lake Kisale. Burton found Hodgson's material more “picturesque and out of the usual than other stations,” and it provided a contrast to his data on savannah-dwelling Luba.Footnote 52 Womersley arrived in 1924 and, after a brief period with Hodgson, spent seven years in Busangu, twenty-one in Kabongo, and another fourteen in Kamina. These locations, Busangu and Kamina in the Kasongo Niembo region in the south, and Kabongo in the north, put him at the heart of the two parts of the Luba polity that had been effectively divided in the 1890s.Footnote 53 Burton also noted, photographed, and sketched a great deal on treks to CEM stations. Staying in villages as he traveled, he saw and learnt a great deal. Trekking provided opportunities for shots of people at work, such as the Lomami fishermen (BPC 08.7–18), or to capture great landscapes (Preston 47, 68, 80).Footnote 54 He took most of his images during the dry season, and 1928 proved particularly productive, when he took four hundred photos.Footnote 55

Tensions of Empire

Burton made his research on the Luba available to the Belgian authorities and had sympathy for certain aspects of their “civilizing mission,” but the CEM's relations with the colonial state were difficult. The tensions created a space between mission and state that helped Burton to form good relations with the Luba.

There was a great deal of collusion between Catholic Missions and the Belgian colonial state to the extent that the Catholic Church was one of the Holy Trinity of powers that ran the colony, along with the administration and the corporations.Footnote 56 But Protestant groups in the Belgian Congo, who were mostly from Britain, North America, and Scandinavia, were viewed as outsiders whose loyalty to the Colony was always under suspicion. The colonial state preferred to deal with a monolithic Belgian Catholicism that sat well with its own homogenizing tendencies.Footnote 57 The CEM was in a particularly precious position. Belgian officials believed that Protestantism with groups animated by zealous lay adepts had a tendency towards independency: “Sous l'influence de leur enseignement, de prophètes thaumaturges et visionnaires se multiplieront en Afrique.” This prejudice was confirmed by the Kimbangu movement of the 1920s.Footnote 58 Reports by colonial officials were far from positive. What unnerved them was the Mission's Pentecostalism. Divine healing undermined the regime's commitment to medical science. Tongues, intercessory prayer, and other pneumatic practices seemed to stir up African believers in a manner that ran counter to the Belgian desire to create disciplined colonial subjects fit for industrial labor. As Governor General Tilkens observed in a retrospective 1934 report, the Mission's “superstitious practices” produced trouble and excitement in the spirit of the Black person.Footnote 59 A 1923 report recorded with approval that the catechists worked under European supervision with children learning to read and write in Kiluba. The carpentry shop at Mwanza and the introduction of basket making were noted with satisfaction. But Burton's claim to have healed Jimmy Salter's arm through prayer was met with incredulity, and his account of termites being chased from the house following a time of intercession was accompanied by a large exclamation mark in the margin from the provincial governor who received the report. “Certain members of the group,” the official observed, “bordered on otherworldliness or neurosis (Certains d'entre eux frisent l'illuminisme ou la névrose).”Footnote 60 When the colonial state did finally begin to have a significant transformative effect on Katanga after the Great War,Footnote 61 the CEM was not always able to draw upon its authority. Some chiefs, in alliance with Catholic priests, secret society leaders, or diviners, persecuted CEM evangelists.

Finally, the religious encounter was complicated by the mediating influence of African Christians who moved ahead of the missionary frontier. In Katanga, Burton and Salter encountered Africans who had already appropriated a modernizing Christianity and were committed to its propagation. These were former slaves, sold into captivity by the Batetela from the north by brigands from the east and south, of whom the most famous were the Yeke of Msiri, and by the Ovimbundu from the south. These ex-slaves had been Christianized at mission stations of the Plymouth Brethren, American Board, and United Church of Canada in Bié, Angola, and once freed in 1910 had returned to Belgian Congo, considering themselves as missionaries.

CEM missionaries entered Belgian Congo in an era when an African-led conversion movement was beginning to take off. From the 1880s, the exploitative and rapid social change that accompanied mining, plantations, and white settlement created intense social, intellectual, and religious disturbance. Africans sought a measure of conceptual control over these global forces by turning to world religion, Christianity or Islam. Converts also gained access to new and revolutionary ideas and tools that helped them relate to the colonial economy. The first major conversion movement happened in Catholic Buganda, East Africa, in the last fifteen years of the nineteenth century. Similar movements soon traversed other parts of the continent. In Belgian Congo the most famous example occurred amongst the Bakongo in the 1920s, in which the prophet and former Baptist catechist Simon Kimbangu was the most prominent of a number of actors.Footnote 62 But there was also a significant movement amongst the Luba, and this provides the context in which many of Burton's photographs were framed.

A Christian Youth Revolution

Most of the images in this section have hitherto been viewed as “ethnographic” photographs, used to illustrate so-called “fetishes” and the remarkable costumes of “secret society” members. However, they first found meaning in missionary texts, where they were used to throw light on the powers of darkness and to record victories over these forces.

The Luba Christian movement took off at the end of the First World War. The “war and its aftermath were collectively a traumatic experience.”Footnote 63 The forced recruitment of porters and workers, the requisitioning of crops, the influenza pandemic of 1918–1920, and the post-war price rises and shortages combined to take their toll.Footnote 64 These traumas followed an earlier series of shocks dating from the 1870s as the Luba polity was undermined and overwhelmed by a combination of internal and external forces: succession disputes within the royal family, Swahili and Afro-Portuguese slavers in alliance with the Yeke, the Batetela wars, and finally Belgian commercial penetration. The millennia-long equatorial “tradition” was shattered and the Congolese embraced new Christian ideas and practices.Footnote 65

Conversion followed a similar pattern to that of the Yoruba, which has been expertly explained by J. D. Y. Peel.Footnote 66 The initial converts were those on the social periphery such as outsiders and ex-slaves. These groups were more religiously biddable than natives. They had lost the spiritual support of home communities and, in the absence of relatives, were more at liberty to make revolutionary religious choices. The wider horizons that travel, enslavement, and relocation engendered made Christianity more metaphorically appealing.Footnote 67 The first major social category to adopt Christianity was young men, and in their hands it became a mass movement. Young men bore the brunt of gerontocratic power in Luba society and were least locked into existing religious institutions prior to their first marriage. As well as an exit strategy, Christianity offered in its ideology of individualism “a ready legitimation to the new cultural choices which now beckoned to the young.”Footnote 68 Where Luba conversion differed from that of the Yoruba was that it took the form of Christianized “witchcraft”-eradication movements, standing in a Central African tradition of cyclical cleansing. Conversion was followed by the abandonment of practices associated with sorcery and divination, and accompanied by the destruction of sacred objects.Footnote 69

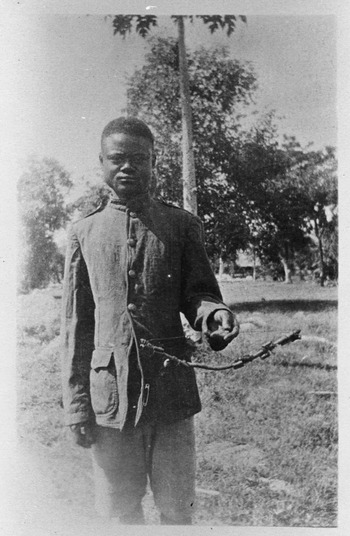

Plate 1 is found in the album of the Witwatersrand Collection. The accompanying notes read: “A charm shaped like a bow, left outside the house of those it is desired to kill.” Although the photograph's ethnographic purpose was to illustrate a fetish, far more significant was the young man holding it, who was the CEM's first convert.Footnote 70 His name was Kalume Nyuki, although after his conversion he chose the significant baptismal name of Abrahama. He was typical of early mission converts in two senses. First, he had already experienced an estrangement from his community when his father had pawned his mother and then him into domestic slavery in an attempt to secure his clan's claims to the Mwanza chieftainship. He had lived in the nearby village of Nkulu until freed by Belgian decree around 1913. In his youth, his family had lived a mobile and precarious existence in the forests in refuge from Batetela raiders. Secondly, Abrahama worked closely with Burton and Salter as their domestic servant, learning European manners and mores, seeing at first hand the tools of modernity.Footnote 71 Missionary accounts of his conversion emphasize his immense conceptual leap in response to a message from Burton and Salter, made in broken Kiluba, accompanied by gesticulations. Abrahama may have understood more than he let on, through his prior experience of Catholic and Brethren missionaries at nearby Nkulu, but African testimony stresses the significance of missionaries' demonstration of the power of the Holy Spirit though divine healing. Burton and Salter had straightened the back of a prominent local elder and may have healed Abrahama's arm after a thatching accident. All traditions stress Abrahama's fascination at missionary literacy: the power of scripture as a new source of knowledge and the magical quality of writing.Footnote 72 Abrahama was an important culture broker between missionaries and Africans. Burton and Salter taught him literacy, and in return he explained their presence to nearby communities, taught them Kiluba, and acted as a willing photographic subject.Footnote 73 So significant was his conversion that his photograph appeared in the first and second editions of the CEMR.Footnote 74 What is omitted from the Witwatersrand ethnographic caption, but not the CEMR, is that the bow was intended to kill Abrahama. While the photograph was posed, the look of distaste in his face as he holds the polluted object at arm's length was probably genuine.Footnote 75

Plate 1 “A charm shaped like a bow, left outside the house of those it is desired to kill” (Courtesy University of Witwatersrand [AL21]).

Abrahama became a leading agent of religious change amongst the Luba. After a period of formation in the missionaries' home and training in the mission Bible school, he pioneered churches in villages within a 30-mile radius of the mission and was instrumental in initiating many other men into evangelism.Footnote 76 As more missionaries arrived, each pioneered a station and built teams of African evangelists who would work in surrounding villages. The CEMR printed numerous photographs of such groups of evangelists and their grimfaced missionary, his arms folded ready for business. What is striking about such images is the youthfulness of the men photographed. Most were, like Nyuki-Abrahama, in their mid-teens when they commenced the work of proselytism.

The tradition of societal cyclical cleansing, of which the Luba Christian movement represented the latest trajectory, was a generational movement that occurred when the social costs of witchcraft became too high within communities.Footnote 77 Missionary accounts highlight the spontaneity of people coming forward to publicly burn their magic. However, there was also disjuncture from what had gone before. Transcriptions of African sermons in the CEMR and missionary hagiographies reveal how converts were captured by the new revolutionary idea of personal responsibility for one's fate which was underpinned by Christian notions of judgment, heaven, and hell.Footnote 78 Protestant Christianity created new types of subjectivity beyond kinship, the membership of associations and cults, and the patronage of big men, in which the individual, called by the Divine, took on a new fixed baptismal name and joined a new Christian community. Henceforth, the believer sought a new source of empowerment from the Holy Spirit. The Luba scriptures would have an electrifying effect on the movement, but in the early days new Christian ideas were often expressed in hymns, which were sung with much fervor and regularity, especially at bonfire meetings for the destruction of charms and fetishes.Footnote 79 The services encouraged first-generation converts to make a break with their traditional heritage in a manner more profound and pronounced than subsequent generations.Footnote 80 Such was the millennial fervor that drove the evangelists that many left their gardens uncultivated believing that their Christian movement heralded end times.Footnote 81

It was these groups of early converts who helped form Burton's perceptions of Luba religion and culture. Although he came to Congo with preconceived ideas about the pervasiveness of “fetishes” and cannibalism, a product of the well-established missionary tradition, these ideas were given force by his African co-workers. It is noteworthy how almost all of his accounts of cannibalism were second-hand, provided by evangelists or Christian porters. Stories of human flesh eaters were a distancing strategy, a means of asserting moral boundaries between their own respectable Christian communities and “heathen” neighbors.Footnote 82 Christianized young men were also prone to revealing the secrets of divination and the activities that took place in Bambudye lodges.Footnote 83 Thus converts turned their “old gods” into “devils.”Footnote 84

The Luba Christian movement engendered persecution from traditional authorities, who saw their activities as an attack on the social order. Young evangelists antagonized gerontocratic elites whose claims for hiership were legitimated by ancestral religion, and they threatened the livelihoods of diviners and healers by converting their clients. Moreover, Christian practices associated with monogamy, childbirth, and burial challenged “the very process of social reproduction, in its moral as well as in its physical sense.”Footnote 85 Evangelists also fought with Catholic priests and catechists who they believed were replacing one form of idolatry for another. The young Protestant zealots were pelted with dung, beaten, tortured, imprisoned, and one was even castrated.Footnote 86 Abrahama was the subject of hagiographies by both Burton and Salter. Most issues of the CEMR celebrated the work of individual evangelists, spurring readers on to prayer and financial support for their work.

As the Luba Christian movement gathered pace, persecution was countered by provocative acts by young male converts who “felt increasingly confident that the future was theirs.”Footnote 87 Such acts set the context of Witwatersrand photographs AL18 and AL19 (Plate 2). The accompanying commentary reads:

A Kanzundji—The medicine men make great gain from the belief that a man possesses a second self who is supposed to act & speak in sleep etc. Thus the native will often candidly admit having done something of which he has no recollection. Men are often made to pay very large sums for having given birth to a malignant little sprite “a Kanzundji” & the great sorcerers unite to catch & display the dead sprite. Some incredulous natives seized this one and brought it to the mission. It proved to be carved in “mulolo” wood covered with “lenda” pulp. Human hair was stuck on with wild owe [?] resin. Eyes were those of a “bikele” fish, intestine of a foul were hanging out, and the whole smeared with dog's blood.Footnote 88

Burton doubtless wrote the ethnographic commentary a good few years after the event, when his scientific knowledge and language skills were more developed. The above story's Christian import—a victory over the forces of darkness—also evolved as bonds of familiarity and trust developed between Burton and his African Christian informants. When the fetish was initially seized in April 1923 it was celebrated as an important trophy. Plate 2 (AL19) of the young man sitting behind his captured prey was published in the first edition of CEMR with the simple caption: “A ‘Kanzun[d]ji’: A sort of a little demon, accredited with calamity and death.” AL18, a picture of a man holding the same object, appeared on the front cover of the second edition, entitled, “Old man with a bogus demon which the wizard declared to have caused him sickness.” The same picture appeared four years later on the cover of another CEMR with a different caption “Old Inabanza with Kanzundji which the witch doctors accused him of exploiting. The lie was shown up and the supposed Kanzundji was captured.”Footnote 89

Plate 2 “A Kanzundji” (courtesy University of Witwatersrand [AL19]).

Burton shared his evangelists' beliefs that such objects were polluted. They were to be avoided so that the body remained a clean temple for the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. However, he also came to believe that others were part of elaborate scams that had a diabolic dimension in that they diverted the believer from biblically mediated truth. In this case, a sorcerer (Burton calls him a wizard) by the name of Djemuna had convinced a local elder living near the mission that he was responsible for a series of local calamities through his enslavement of a “dream child” or sprite, as a proxy. The sorcerer then organized a public hunt for the dream child and dug up the fetish he had previously buried in the elder's compound, extracting a large fine for damages. Convinced that a scam was taking place, Burton promised to pay the taxes of anyone who could steal the Kanzundji and bring it to the mission. The young man holding the object (Plate 2) is probably Lomami, the swiftest of the evangelists who grabbed it and fled while his fellows, including Abrahama, ensured his clear path. The old man holding the Kanzundji (AL18) is probably the local councilor Inabanza Kasongo, who, following his liberation from the sorcerer, became one of Burton's key Luba informants.Footnote 90 Burton subsequently sawed the Kanzundji in half to demonstrate its mundane nature and Abrahama transported it around adjacent villages, drawing large crowds. Justifying the theft, Burton wrote, “A simple demonstration of the heartless frauds of the witch doctor fraternity would help them to loosen their hold on the old and reach out to the new.”Footnote 91

While Luba diviners drew status from their “skill to see beyond the visible phenomenon and to interpret deeper meanings,”Footnote 92 Burton sought to make visible these “powers of darkness,” and photography provided him with an excellent means of “making it subject to the spectators gaze and thus neutralizing its power.”Footnote 93 Thus in a vignette entitled “Invading a Bambudye Sanctuary,” Burton describes how, by using information provided to him by former converts, he was able to follow secret entrance procedures and gain entrance to a Bambudye lodge. His success was marked by a series of photos (BPC 22.15, 16, 17).Footnote 94 Similarly, a deception by the “Tupoyo cannibal society” that there was a lion in their lodge was exposed by photo of a pot used to make a roaring noise (BPC 07I.5).

Sometimes, “unmasking” happened literally as members of secret societies dispensed with their costumes and dances to join the Christian movement. Such stories were celebrated in the CEMR and other mission journals through the conceit of “before and after” conversion, but they were rarely told in Burton's ethnographic writing and photography. Some of his best-known ethnographic prints are those of budye and kasandji associations. The former was a political faction whose function was to initiate political candidates into the rules and regulations of royal authority. The latter were doctors who dealt with malevolent spirits though spirit possession and controlled witchcraft accusation.Footnote 95 The striking picture (Plate 3, BPC 12G.19) is part of a series of shots from the Witwatersrand collection.Footnote 96 The picture itself has no caption but the following shot of the same men is accompanied by the words “LUBA 2 bavidye [mediums]—the one with big feathers is the head necromancer” (BPC 12G.20). An earlier print in the same series has the note: “LUBA. This necromancer said ‘If we do not make ourselves extraordinary to attract attention & excitement the people lose interest in us & our cures. We have some good cures but we have to excite the people to come and get them.’ This is the most intelligent answer given for their weird dances and paraphernalia” (BPC 12G.14). Burton's account of the mediums' dress marks one of the numerous instances where his written appraisals ran counter to his aesthetics. In spite of his derogatory commentary, he took many fine photographs of Luba religious practitioners, highlighting their complex body mnemonics through which they reproduced memories of Luba royal culture an its heroes. Many of these photographs were subsequently transformed into careful gouache and watercolor paintings and together they represent some of his most significant scientific work.Footnote 97

Plate 3 “LUBA 2 bavidye” (courtesy University of Witwatersrand [BPC 12G.19]).

The picture not included in the Witwatersrand collection is the post-conversion shot of same two men—now called Peter and Stephen—smiling and wearing modern clothing, found in a 1933 edition of CEMR (plate 4). Showing both photos side by side, the CEMR caption reads “Kabondo Dianda Sorcerers. Three years ago we photographed these Consulters with the spirit world. Since then they have been saved, and now they are happily testifying of Jesus Christ and his abounding grace.” The readers were told that some three or four years earlier one of the men, Milhanshi, had heard a white man preaching in Busangu and had become so intrigued that he had traveled four days to hear more “Words of God.” Just two weeks after his conversion, Milhanshi was reported preaching on the subject of Hell.Footnote 98

Plate 4 Peter and Stephen (courtesy CAM [CEMR 43, July–Aug. 1933]).

The outward transformation of the vidye medium (Plate 3) into Peter the convert (Plate 4) was not complete. He continued to wear what appears to be a cone-shell necklace as a mark of status amongst the Luba.Footnote 99 Like Luba Christians, Burton also chose to retain some pre-existing notions of hierarchy and authority.

Chiefs and Traditionalists as Trophies and Reformers

Burton's photographs of traditional leaders reveal a tension between his desire for cultural change and a desire to preserve. In mission publications, he disapproved of the reprobate lives of chiefs but his photographs show relations of intimacy and trust with some of the same figures.

While the lives of renamed individuals were celebrated in missionary literature, we are rarely told the identity of Burton's ethnographic subjects. One important exception was chiefs. Such figures were subjected to a great deal of coverage in the travelogues and missionary writings from which ethnography emerged. As representatives of their peoples they were often the first to be encountered and western enterprises often hinged on their cooperation. They personified the social and intellectual universe missionaries were learning. And stories of chiefly tyranny and excess made entertaining reading for western publics. All of these themes found their way into Burton's writing, but he had another more particular set of concerns when it came to traditional rulers.

Like many missionaries, Burton believed that chiefs were crucial to the conversion of their people. In a 1917 Report he discussed several traditional leaders in terms of whether they were sympathetic or hostile, explaining, “I have given prominence to the chiefs in this report, as it is around these that people gather.”Footnote 100 Burton was aware that the Belgian administration discouraged Christian villages because they undermined the authority of chiefs and sub-divided its neatly ordered regime of customary jurisdictions. But his 1933 inspirational text, When God Changes a Village, makes clear that his ideal was a Christian village under a Christian chief. He wished new converts to be isolated from the “contaminating” influences of “heathenism” found in towns, mines, and amongst non-Christian rural dwellers. In a Christian village, missionaries could teach, change landscape and architecture, and introduce literacy, schooling, and western notions of hygiene.Footnote 101

Modern Christianized chiefs were “Living Trophies,” celebrated on the pages of CEMR.Footnote 102 The prime example was Chief Penge of Bunda. A colonial report dated 1916 reveals that Penge was a minor chief with an ambiguous status in relation to the state. Modernizing Christianity was an alternative source of authority.Footnote 103 Abrahama had taken the captured and dissected Kanzundji to Bunda village and Penge had declared himself against such trickery. Henceforth Burton's letters to Salter contained updates on Penge as those around him—his wives, children, corporal, and soldiers—converted and entered the mission's schools and churches. In late 1931, Penge walked 23 miles to the mission station at Mwanza to make a public profession of faith. Soon he was preaching in his local chapel and even his counselors converted.Footnote 104 The story was given full coverage in the CEMR January–March 1931, and two years later Penge and his village, Bunda, was the subject of When God Changes a Village. Penge built a new brick church for his people and a brick house with veranda for himself. He also destroyed his charms, including those of a converted sub-chief, in a large bonfire (Plate 5). Penge became Burton's favorite, for whom the CEM imported bicycle parts.Footnote 105Plate 6 (EPH 3436) is located in the Tervuren Collection. It has the caption, “Chief Penge of Bunda with his Kobo on his head and an apron of leopard skin. Only the chief can wear them.” Burton subsequently turned the photograph into a watercolor, now in Museum Africa, Johannesburg. In both images, Penge's identity is frozen as traditional chief rather than the modernizing Christian that he had become.

Plate 5 “The Bonfire. Inset: Chief Penge's New House,” from W. F. P. Burton, When God Changes a Village. London: Victory Press, 1933, 134 (courtesy CAM).

Plate 6 Chief Penge of Bunda (courtesy MRAC [EPH 3436, collection RMCA Tervuren; photo W. F. P. Burton]).

If Penge represented the Christian chief, his antithesis was Chief Bululu of Ngoimani. Bululu was included in both the January 1931 edition of the CEMR and When God Changes a Village, as a visual and verbal contrast to Penge (plate 7, Preston 79). Like Penge, he is photographed on his chief's stool wearing rare skins, with fly whisk, spear, and shell necklace as marks of office. But the CEMR reader is alerted to the antelope [or buffalo] horn magic (dyese) on the mat that provides him with protection, and the disappointing presence of polygamous wives behind him. In When God Changes a Village we learn that Penge sent news of his conversion to neighboring chiefs, inviting them to take a similar step. But Bululu, “recently out of prison,” preferred his beer, and died three days later. Bululu's picture was also included in the set of Preston magic lantern slides, doubtless as an object lesson in what happened to unrepentant chiefs.

Plate 7 Chief Bululu of Ngoimani (courtesy CAM [Preston 79]).

However, bonds of loyalty and admiration forged over many years could transcend the simple evangelical dualism of saved and unsaved, as illustrated by Burton's relationship with his local chief. Plate 8 (BPC 13.11) is entitled “LUBA. My old friend chief Kajingu of Mwanza in full regalia.” A picture in same series, a side view of the chief with his regalia, which appeared in the CEMR in 1933, had the caption “Kajingu, the first chief to welcome this Mission to the Congo.”Footnote 106 In spite of the complaints of the Catholic Apostolic Prefect Callewaert that the projected Protestant Mission at Mwanza was too close to the work of the Holy Ghost Fathers at Kulu, and subsequent visits by colonial agents to persuade the chief to change his mind, Kajingu was adamant that he wanted a CEM mission in his village. He was perhaps irritated that Catholic promises of a mission had not materialized since their 1913 arrival in the area, but he was more likely to have concluded that a mission on his doorstep would help bring security to his people.Footnote 107 Prior to his succession, the chieftainship had been divided by a violent factional dispute between rival clans, and then the Batelela had raided from nearby stockades at Kijima and Kikondja.Footnote 108

Plate 8 “LUBA. My old friend chief Kajingu of Mwanza in full regalia” (courtesy University of Witwatersrand [BPC 13.11]).

In the context of indirect rule it was in the interest of traditional leaders to be photographed with symbols of their authority, and there are many similar shots of chiefs in ethnographic and missionary collections. But what is striking about this one is the friendship it suggests between the photographer and subject. The softness of Kajingu's gaze, enhanced by the intimate feel that comes from the use of the homestead to frame the picture, suggests a genuine closeness between the two men. Indeed, Burton's notes accompanying the Witwatersrand photograph continue, “I'm the only white man who has been allowed to see the bead work cap as he is afraid of having it taken from him.” Subsequently Kajingu would allow Burton to have a copy of the cap made for the South African collection.Footnote 109 Burton proselytized Kajingu like Penge, but made little headway. In a letter to Salter penned in 1932, he observed, “Old chief Kajingu seems very warmly inclined to us personally but no nearer the gospel. He imprisoned some Kabishi because a Vidye told him they were casting evil spells upon him.”Footnote 110 Although the sources reveal little about how the Luba responded to photography, the apparent ease of Kajingu and other chiefs before the camera may well have come from familiarity with similar imagery within their traditions of figurative art.Footnote 111 Given that self-presentation was an essential professional skill, they doubtless also quickly recognized that photography multiplied the impact of their efforts. The Mwanza chief, like others photographed by missionaries in West Africa, conveyed a sense of confident authority.Footnote 112

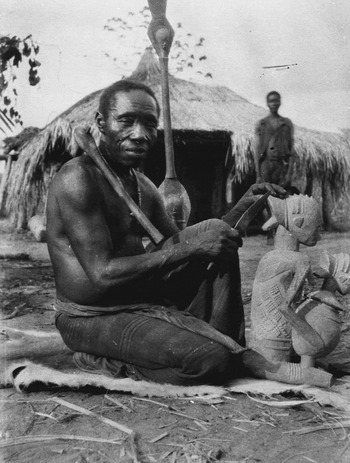

Burton also formed close bonds with other local traditionalists. He enjoyed the company of the Kitwa Biseke, the official sculptor of the Nkulu chieftainship who resided in the aforementioned Kabishi village. Kabishi intrigued Burton and he spent a good deal of time there. On its perimeter was a striking Mbuyu Bwanga shrine formed out of clay in the image of an enormous tortoise to which the villages offered libations of blood and beer for protection.Footnote 113 Burton photographed and painted the shrine. The village itself was an atelier, a community of sculptors who carved regalia for several chiefs in the region: Kajingu, Bunda Penge, Mulamba, Kasele, Lubembei Mukadi, Nkulu Kapoya, and Mulongo Mafinge. Biseke was most prominent among the sculptors but there was also Mfyama Kato, whose son Banze Zacharie was educated and employed at the mission. Burton would visit Kabishi to buy or commission objects for Tervuren or Witwatersrand. It was a place where he conducted research for his collection of Luba proverbs and it was of course a site of evangelistic activity. Located just a few miles from the mission station, he would stop on the way home to watch the sculptors at work and proselytize them.Footnote 114

In Congo Sketches (1950), Burton recounts one of his conversations with Biseke. The encounter took the form of an extended dialogue involving scripture and Luba folklore. When Biseke told the proverb, “The carver can fashion an idol, but bones and life are beyond his power to produce,” Burton seized the opportunity to launch a discussion about the value of life, its ephemeral nature, and Christ's death and the final judgment.Footnote 115 Burton had a fascination with Luba proverbs and compiled an immense collection of them, grasping their utility for amplifying Christian ideas.Footnote 116 He did make converts in Kabishi, but on learning of Biseke's death in January 1944 he lamented to Salter, “Old Kitwa, whom you knew at Kabishi, died last week. He had made a sort of profession of faith in the Lord Jesus once, but there was no solidity in it, and he has gone to eternity without any real hold on the gospel, tho' I've sat and talked to him of Christ, and those who gathered at his smithy for hours and hours.”Footnote 117Plate 9 (BPC 05.13) is skillfully crafted so that the sculptor becomes a sculpture, though his statuesque appearance remains human through his smiling demeanor. The image captures the production of a bowl figure with detail of cicatrisation and the kitwa's personal staff standing erect behind him.Footnote 118 Its arrangement was the result of a good deal of cooperation between the photographer and the kitwa-sculptor.

Plate 9 “A Kitwa (chief's personal wood carver) carving a Kitumpo (for divining) with a knife & adze only. The Kitwa's Kibango (carved staff) is behind him” (courtesy University of Witwatersrand [BPC 05.13]).

Women, Protestantism, and the Ambiguities of Aesthetics

In his propagandist piece for Congo Sketches, (103) Burton described Biseke rather pejoratively as an “idol maker,” and was none too complimentary about his sculptures, despite the fact that he took at least six shots of the kitwa in action (BPC 05.13–16; Tervuren EPH 3440; Preston 57). His missionary writing was intended for a sectarian Protestant audience whereas his painting and photography gave him far more scope to express his broad appreciation of aesthetics. Through these visual media he showed a more complex and ambivalent attitude towards Luba art and culture. Nowhere was his ambivalence deeper than in his representations of Luba women. In spite of his prudery, Burton reproduced familiar visual tropes that sexualized native women, which, when placed in the wrong context, forced him to have to explain himself.

The axiom that the twentieth-century African Christian movement was “a woman's movement” did not apply to Luba women, who initially proved more resistant to Christianity than young men.Footnote 119 Luba culture ascribed women a status complementary to men, in which they reproduced royal ideology and practice. Through coiffures, cicatrisation, and adornment, their bodies became “receptacles of spiritual energy and beholders of political secrets.”Footnote 120 Moreover, missionary strictures about Christian marriage seemed to limit their options to bear and successfully rear children. Burton was shocked by Luba notions of sexual hospitality. He was also unnerved by the advances of young women and felt unable to proselytize them.Footnote 121 Although he was dismissive about the contribution of “single lady” missionaries in the harsh bush environment, he was pragmatic enough to return from his first furlough in 1918 with a wife who could found women's work.Footnote 122 Salter quickly married, too. Women's work was thus a separate province of the mission enterprise conducted by female missionaries. The first converts were runaways, women fleeing domestic slavery or abusive relationships.Footnote 123 Hettie Burton built a women's refuge, which beside “runaways,” attracted other socially marginal women such as widows who lacked the security of living children, and abandoned infants. In time, other women converted, especially as the female missionaries developed their skills in midwifery.Footnote 124

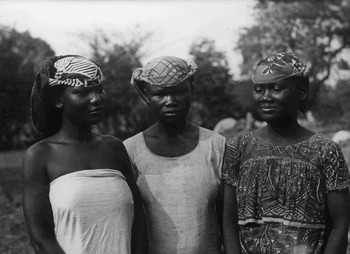

A key missionary strategy was to form respectable Christian wives for the growing cadre of young evangelists and pastors. Burton feared that without suitable Christian wives the young men would be drawn back into heathenism. The women were encouraged to cease traditional religious practices and taught devout domesticity. They were instructed on washing, ironing, and the virtues of cleanliness, hard work, and honesty. They were encouraged to weave mats for European tastes, and taught how to cultivate small vegetable gardens, European-style. Those who were fractious or who decided to marry non-Christian men were “chased away.”Footnote 125 The products of such patient work in Christian formation are depicted in the Preston magic lantern slide (plate 10) taken in the 1930s or early 1940s. It is an image of three Christian women (from left to right) Ndokasa, Luise, and Nshimbi Jennifer, described by male informants as “pastors wives.” Dressed in what Burton liked to describe as modest clean cotton clothes, their heads covered with simple turbans rather than complex coiffures, they represented a new type of Christian womanhood.Footnote 126 The slide complemented another of five male pastors dressed in simple cotton shirts. The images represented to western Church audiences the best fruit of missionary labors, providing outward and visible signs of conversion.

Plate 10 Ndokasa, Luise, and Nshimbi Jennifer (from left to right) (courtesy CAM [Preston 73]).

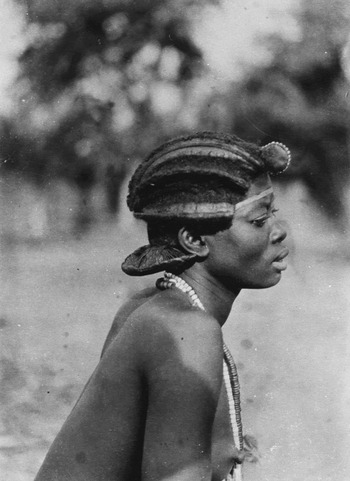

Burton also photographed many women beyond the mission station to record cicatrisation, jewelry, coiffures, and use of clay and chalk to mark liminal moments. He had an eye for beauty and pictured both striking men and women. Plate 11 (BPC 12G.29), of a beautiful woman from Busangu in the Lovoi Highlands taken for the University of Witwatersrand, sums up his ambivalence toward Luba aesthetics and the cultural change that accompanied Christianization. The caption simply reads, “LUBA Headdress of the BENE-MUNONGA.” The picture was one of four that had the ethnographic intention of “illustrating step” or “cascade” coiffure that was popular from the later nineteenth century until the 1930s. The final shot compared the coiffure and the design of a kinda stool (BPC 12G.31), highlighting how Luba notions of style and beauty were transmitted via its sculpture.Footnote 127

Plate 11 “LUBA Headdress of the BENE-MUNONGA” (courtesy University of Witwatersrand [BPC.12.G 29]).

Burton was obviously struck by his subject's beauty. He devoted a good deal of time and thought to her classically posed image, perpetuating a genre that sought to establish continuity between photography and classical art.Footnote 128 The blurred background created the effect of a studio shot such as those taken by 1930s Paris fashion photographers. Burton subsequently used the photo as the basis of two careful gouache paintings. The first is now in the Central African Museum in Tervuren, and the other became the cover of Congo Crosses: A Study of Congo Womanhood, by U.S. Presbyterian missionary Julia Lake Kellersberger.Footnote 129 A note on the cover picture revealed that the unnamed woman was married to a leader of a secret society that “ate human flesh.” Her hairstyle took sixty hours to complete and four hundred hours a year to maintain. She had recently become a Christian and “put on modest dress.” Burton also made a simple sketch of the photograph for the CEMR with the caption: “Headdress in S.W. Lubaland. This girl has since become a Christian, and feels that she cannot waste her time in such folly as hair braiding.”Footnote 130

The decisions to abandon traditional coiffures, cicatrisation, and the removal of the two bottom front teeth in young boys as a “tribal mark” came from Luba Christians rather than missionaries, and they highlighted a deep ambivalence about tradition in Burton's missionary practice.Footnote 131 He disapproved of the scant clothing Luba women wore, but observed that their bodies were “fantastically decorated with beads and mother of pearl shirt buttons.” And while men “wasted” hundreds of hours on elaborate “headdresses,” the resulting coiffures nevertheless “tickled his fancy.”Footnote 132 It is noteworthy that although the unnamed Busangu woman became a Christian, there is no after-shot. Burton preferred to photograph and to paint her in a state of heathen beauty. The photo is cropped in a manner that emphasized her breasts and nipples. Her back is tilted and her mouth open in a suggestive manner. In spite of his ascetic and puritanical nature, Burton was still moved by desire.

Although there was some overlap between mission and ethnographic genres, certain subject areas had to remain compartmentalized. In 1942 the CEMR accidentally confused the genres, scandalizing its readers. Harold Womersly, now editor of the magazine, fell ill and his replacement included a picture captioned: “A ‘bata’ water-lily, once worn on the head as a sign of engagement or marriage, or announcement of the first sign of womanhood.”Footnote 133 The subject was an attractive bare-breasted young woman in her prime. Her coquettish smile and the flower in her hair added to her allure. The ethnographic interest in the photograph lay in the cicatrisation around her waist and here Burton was following an “interest in tattooing” that was certainly “widespread among anthropologists at the end of the nineteenth century, and was part of a more general fascination with anthropological difference as inscribed on the body.”Footnote 134

But such photos were often also overtly sexual, used in other contexts for non-scientific purposes.Footnote 135 Once again Burton reproduced this visual trope, taking the photograph in such a manner that the light fell upon the woman's breasts. Plate 12 (BPC 21.1) caused a storm of Pentecostal protest. The photo of the Busangu woman with her cascade coiffure (plate 11) would have gone well in the CEMR, particularly the series run in the 1940s entitled “Curious Congo Customs: You will never see it again.” But Burton chose not to include it, doubtless because of the subject's bare breast. His gouache paintings of the same woman repositioned her beads to create a more wholesome image. Commenting on the saga in his correspondence with Salter, Burton scoffed, “Womersley would certainly not have put the snap in, had he been well. It is right as a scientific record, but fancy writing about ‘the first signs of womanhood in a missionary magazine.’”Footnote 136 The 1943 January–February edition of the CEMR carried “An Apology and an Acknowledgement”:

Some of our missionaries have done considerable work in helping put to record fast-disappearing customs among the natives. Among some excellent photographs was one which appeared in last issue under the “Native Life Series No. 13.” As a scientific study it was quite correct, but for our Report the head and shoulders alone should have been shown “A Water lily for an Engagement Ring.”

Thousands of natives who throng us everyday wear very few clothes, for we live quite near the equator. Yet it is hard to show pictures of the people as they really are. Our readers would not appreciate it. How often the Editor has to reject an otherwise splendid picture because of some semi-naked individual who has found his way into the snap.… The picture was originally taken for the Johannesburg University.Footnote 137

Plate 12 “A “bata” water-lily … announcement of the first sign of womanhood,” CEMR July-August 1942. Ethnographic caption reads: “Kime. Girls ornament their heads with the purple “bata” water-lily—worn jauntily on one side” (courtesy University of Witwatersrand of [BPC 21.1]).

Conclusion

Burton was representative of a small but influential group of people in his generation who had a keen interest in “native culture” but were also actors in colonial and missionary settings. This at times could lead to a somewhat schizophrenic attitude towards Africans. Many of Burton's photographs arose out of relationships of trust with his subjects—a concern for their material and spiritual development that transcended the designs of Belgian colonialism. Other images point to a respect between photographer and subject in spite of strong differences in religion and culture. Keenly aware of the expectations of different audiences, Burton remained mindful of the rules and effects of genre and separated them when necessary. When his collections are viewed together as a whole, the images offer fresh insight into the complex and ambiguous nature of the missionary encounter. There has been a tendency in the literature to see missionaries as unyielding proponents of a western lifestyle, but the photographs show Burton to be moved by Luba aesthetics. While his missionary prose characterizes his relations with traditional authorities in adversarial terms, his photographs reveal mutual respect and cooperation. The photos also illustrate the mediating roles of African agents in Christianization and in shaping missionary perceptions and texts.

Photography and painting enabled Burton to escape the narrow constructs of his Pentecostal faith. Younger missionary colleagues criticized him for wasting time on painting sunsets and village scenes. At one stage he even threw his paints away because he had become “too fond of them,” but then had “miraculously” received a new paint box the following day and happily taken it as a sign that he should continue painting to raise funds for mission work. For the most part, he managed his ambivalences towards the Luba and their representation by juggling different aesthetic styles and building personal relations with key figures, Christian and “pagan.” However, as in the case of the photograph of the nubile young woman adorned with little more than a water lily in her hair, sometimes the tensions were laid bare for all to see.