On 16 September 1856, gentleman illusionist Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin embarked from Marseille on the steamship Alexandre bound for the embattled French colony of Algeria. Thirty-six hours later, a detachment of French soldiers met him in the port of Algiers. Recently retired as an entertainer to pursue research in optics and the emerging field of applied electricity, Robert-Houdin was about to return to the stage in a series of magic performances that a French general purportedly called the most important campaign in the pacification of indigenous Algeria (Chavigny Reference Chavigny1970: 134).

While France had captured Algiers in 1830, much of Algeria remained an unpacified tinderbox of anticolonial resistance. The political director of the Bureau of Arab Affairs, army colonel François-Edouard de Neveu, was particularly concerned about the subversive influence of Muslim holy men he identified as marabouts. According to intelligence, some of these marabouts feigned supernatural powers with conjuring tricks, gaining religious veneration as living saints and wielding their influence against the French. Faced with what appeared to be a dangerous form of charlatanism, de Neveu, with possible encouragement from Emperor Napoléon III himself (Fechner Reference Fechner2002: 39–40), solicited the help of France's most famous stage magician. It took de Neveu nearly two years and three requests to persuade him, but Robert-Houdin eventually agreed to undertake an improbable mission: counteracting the sway of wonder-working religious figures by performing modern, European, magic for Algeria's Arab chiefs. Two years later, Robert-Houdin explained the underlying logic of this campaign in his memoir, Confidences d'un prestidigitateur (A conjuror's confessions)Footnote 1:

Intriguers claiming inspiration from the Prophet, and whom the Arabs regard as God's messengers on Earth incited most of the revolts that have had to be suppressed in Algeria … . Now, these false prophets, these holy marabouts, are no more sorcerers than I am (indeed, even less so), but succeed in igniting the fanaticism of their coreligionists with the help of conjuring tricks as primitive as the audiences for whom they are performed … . It was hoped, with reason, that my performances would lead the Arabs to understand that the marabouts’ trickery is naught but simple child's play and could not, given its crudeness, be the work of real heavenly emissaries. Naturally, this entailed demonstrating our superiority in everything and showing that, as far as sorcerers are concerned, there is no match for the French (1995 [1858]: 502).

In the context of colonial conquest, modern illusionism would become a demonstration of power calculated to both disenchant local modes of religious authority and enchant European dominion.

Robert-Houdin's mission is an extraordinary example of the use of spectacle in European imperialist projects to astound, frighten, or beguile indigenous spectators and dramatize knowledge differentials, enacting and reinforcing assumptions about the superiority of Western civilization (Fabian Reference Fabian2000; Taussig Reference Taussig1991; Reference Taussig1993) and, in this case, orientalist stereotypes of North African Muslims as irrational, childish fanatics (Said Reference Said1979). After describing the magician's own account of these performances, I go on to examine the cultural logic behind the French army's curious choice of magic as a mode of “imperial spectacle” (Apter Reference Apter2002). I argue that, to a large extent, this choice depended on the way colonial ethnographers had already used entertainment magic as an analogy in describing Algerian religious practices, making it possible to imagine magic as a potential substitute for indigenous ritual.

In Algeria, Robert-Houdin was a spectator as well as a performer. Like many visitors, he witnessed a ceremony of the ‘Isawiyya (sing.: ‘Isawi),Footnote 2 a mystical Sufi order famous for ecstatic rituals involving displays of seemingly miraculous invulnerability to otherwise painful and potentially lethal self-mortifications. The ‘Isawiyya emerge from Robert-Houdin's narrative as the magician's principal adversaries, epitomizing the “primitive” trickery that he supposed kept Algerian Muslims in a state of religious thralldom. The magician was only one of myriad nineteenth-century French men and women to write about the ‘Isawiyya in these terms. As Trumbull (Reference Trumbull2007: 451–52) masterfully describes, “the ecstatic routines and physical excess” of the ‘Isawiyya “fascinated the French,” while also provoking a “sense of threat and fear.” Sensationalistic news features and mass-produced artist's renderings gave the order widespread notoriety in metropolitan France; ‘Isawiyya troupes from Algeria even toured Europe on several occasions, performing in Paris and London. Focusing on the period from 1845–1900, I explore the way these representational and exhibitionary practices confirmed the ‘Isawiyya's reputation as charlatans by associating their ritual performances with the trickery of Western stage magic.

As powerful as were discourses equating the ‘Isawiyya with illusionists, they did not gain unanimous support. During the period under consideration, the ‘Isawiyya also attracted sustained attention from members of French esoteric movements—Mesmerists, Spiritists, and Occultists—who hailed them as veritable scientific marvels and aggressively challenged allegations of trickery. Exploring a range of perspectives in the nineteenth-century ‘Isawiyya controversy, I focus particularly on both the deployment and contestation of analogies with magic. The articulation and enactment of this analogy, I argue, provides powerful evidence of the cultural role of magic in constituting what I will call the normative ontology of Western modernity—a set of assumptions about reality and perception that received widespread support in the scientific and scholarly institutions of post-Enlightenment Europe. Likewise, disputing representations of the ‘Isawiyya as tricksters was a means for heterodox intellectuals to assert alternative ontologies.

While my story inevitably intersects with the political history of French colonialism and the ethnohistory of North African Sufism, I do not purport to analyze either of these things per se, nor do I rely extensively on the kinds of archival sources such analyses would require. What I am proposing is a discussion of the place that entertainment magic occupies in published and publicized representations of prodigious Sufistic practices in order to clarify the cultural parameters of Western—French—magic itself. At the very least, the tendentious nature of these representations should raise suspicions about the ideological underpinnings of authoritative French discourses. I hope my presentation of these materials also generates provocative questions about politics and religion in colonial Algeria, but I am unable to explore these issues in any detail here.

MODERN MAGIC AND ITS DANGEROUS DOUBLES

Modern stage magic is a paradoxical form of entertainment, seeming at once the performative counterpart to a rational, disenchanted worldview, and a residual or compensatory locus of irrationality and enchantment. Magicians trade on this ambiguity, employing occult iconography at the same time as they pursue projects of demystifying occult practices and beliefs (During Reference During2002). In recent years, cultural historians have connected the efflorescence of entertainment magic with the formation of distinctively modern cognitive repertoires, as a genre that promotes critical, self-reflexive subjectivity. Just as the magician must be accountable to delight but not delude in Saler's memorable phrase (Reference Saler2006: 713), audiences must be willing to be deceived but not so credulous as to mistake illusions for reality. The kind of self-reflexive stance required for audiences to regard magical deceptions as a source of amusement ultimately made magic one of the most popular parlor recreations of the European Enlightenment and, subsequently, a crucial vector for the democratization of Enlightenment values and ideas (Stafford Reference Stafford1994). Commenting on this development, Schmidt writes that the “Enlightenment did not so much assault magic as absorb and secularize it,” transforming it into “a widely distributed commodity of edifying amusement,” and a medium for conveying “the skeptical professions of the philosophes in a performative and entertaining mode” (Reference Schmidt1998: 275–77).

Just as a long tradition of East Indian performance magic enacts the cosmological principal of maya, the world-as-illusion (Siegel Reference Siegel1991), Western illusionism converged with modern materialist cosmology and empiricist epistemology. Modern magical showmen exposed the public to new technological advances in fields such as optics and electricity, even adopting the performance conventions of scientific demonstration (Nadis Reference Nadis2005). They also associated themselves with the cause of progress by aggressively attacking what During calls the “dangerous doubles” of illusionism: occult magic and criminal fraud (2002: 81). Cook (Reference Cook2001: 169) argues that, by the beginning of the nineteenth century, the illusionist had emerged as “a powerful symbol of progress” in the West, as a scientific popularizer and a debunker of superstitions, but also as a catalyst of critical controversy in the expanding public sphere, claiming “disenchantment as [a] raison d’être in the post-Enlightenment world” (179). As a popular representative of European cultural modernity, the Western magician also became an icon of progress outside the West, in China, for instance (Pang Reference Pang2004).

Still known among magicians as the “Father of Modern Magic,” Robert-Houdin was the nineteenth-century avatar of magical modernism. The poster for an 1849 performance in London depicts him in an elegant salon, dressed in stylish eveningwear, demonstrating sophisticated automata of his own invention (fig. 1). In his “Confidences,” Robert-Houdin amplifies an image of himself as a principled man of science and good taste, who singlehandedly reforms magic into a respectable bourgeois entertainment by purging it of problematic associations with low culture, the criminal demimonde, and backwards superstition (Jones Reference Jones, Hass, Coppa and Peck2008). Depicting predecessors as “mystifiers” guilty of deceiving and deluding the public, he similarly decries the intellectual shortcomings of spectators prone to delusion. He plots relationships of correspondence between modes of apprehending magic and spectators' social stations, with the male monarch, Louis-Philippe, typifying an appropriate attitude of playful, self-reflexive detachment, and members of the working class, women, and African colonial subjects embodying naïve, uncritical perspectives. In this rhetorical framework, the Algerian episode serves not only to burnish the author's reputation as a national hero, but also to buttress his distinction between modern magic—a harmless mode of entertainment amenable to bourgeois sensibilities—and retrograde charlatanism linked with superstitious fanaticism. For Robert-Houdin, narrating the confrontation with the marabouts was therefore part of a broader strategy of staking out professional status and establishing illusionism as a legitimate form of expertise, compatible with a scientific worldview and opposed to unscientific forms of knowledge.

Figure 1 Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Robert-Houdin's memoir makes explicit a normative assumption that the performance of a trick should always elicit from spectators a line of etiological reasoning leading back to the magician's skill. Modern conjurors, while often dabbling in occult iconography, generally do not intend audiences to perceive supernatural forces at work in their performances. Far from it; they want individual credit for their technical prowess (Metzner Reference Metzner1998). In Gell's (Reference Gell1998) terms, the modern magic effect is an index through which the spectator should discern the magician's agency, and most assuredly not the influence of a supernatural agent. In a modern context, misconstruing tricks as evidence of anything other than the conjuror's manual dexterity or mechanical ingenuity becomes a potential mark of unreason or even insanity. Indeed, nineteenth-century French discussions about the ‘Isawiyya seized upon the ability to perform and interpret magic tricks successfully (i.e., according to the standards of secular entertainment) as metonyms for modernity itself.

The kind of self-reflexive subjectivity Robert-Houdin presents as essential to the appreciation of modern entertainment magic is a cognitive skill that colonial literature widely depicted Algerians as lacking. It is not entirely clear whether, in deploying a magician, the French intended to dispel the ignorance they attributed to indigenous people or exploit it (Robert-Houdin himself suggests both motives in the passage quoted above). Either way, the subsequent representation of his performances as a successful instance of the modern disenchantment of primitive superstition reaffirmed French convictions of cognitive superiority, as did the ethnographic representation and performative presentation of the ‘Isawiyya as insufficiently disenchanted magicians. By unfavorably comparing Algerians’ supposed credulity toward the alleged trickery of indigenous ritual practices to their own attitude of incredulity towards conjuring as a form of disenchanted entertainment, the French used magic as a powerful marker of cultural difference and divergent social evolution. In the following section, I describe the elaboration of this motif in Robert-Houdin's account of his 1856 performances.

THE FRENCH MARABOUT

Robert-Houdin's magic shows were scheduled to coincide with a colonial festival honoring Arab chiefs, on evenings of the second and third days of extravagant equestrian games. By the time the magician and his wife reached Algeria, however, armed rebellion had broken out in Kabylia; military operations would postpone his performances for five weeks, until 28 October. The evening of the first show found Robert-Houdin restless with anticipation. He recalls anxiously peering out from the wings of the cavernous Theater of Algiers at the Arab chiefs, with their large entourages and flowing burnouses, squirming uncomfortably in the unaccustomed seats (1995: 510). When the show finally began, the magician confesses, “I felt a bit like laughing … presenting myself as I was, with a magic wand and all the gravitas of a veritable sorcerer. I didn't give in. This wasn't a matter of entertaining a curious and receptive audience, but of striking a powerful impression on crude imaginations and backwards minds. I was playing the role of the French marabout” (511).

Unsure how this untested audience would respond, Robert-Houdin proceeded cautiously, opening with his most trusted material from the genteel magic act that had made him the toast of European polite society. The spectators were impassive at first, but when he produced cannonballs from an ordinary hat, he says they began to thaw, expressing, as the conjuror puts it, “their joyous admiration through the strangest and most energetic gestures” (512). Encouraged, he moved on to “The Horn of Plenty,” the trick depicted in the upper left cameo of the poster in figure 1. He held an ornate lacquered metal cornucopia up for all to see. It was clearly empty. The audience was amazed when he then pulled dozens of small presents from within the mysterious object and distributed them throughout the theater. More cheers. A seasoned professional, Robert-Houdin knew exactly how to choose tricks that would win over a diffident—in this case, potentially hostile—audience, even in an unfamiliar cultural setting. In Europe, one of his trademark routines, called “The Inexhaustible Bottle,” consisted in serving, from an improbably small receptacle, seemingly limitless amounts of any liquor the audience requested. Respecting Muslim custom, he instead magically filled an empty tureen with piping hot coffee. At first reluctant to ingest a seemingly diabolical beverage, Robert-Houdin says that the spectators were soon “unwittingly seduced by the perfume of their favorite liquor” (513).

But these were all trifles compared to the “irrefutable proofs” of supernatural power Robert-Houdin intended to provide. For this, he had prepared three blockbuster tricks. First, he invited a muscular young Arab to join him on stage, boldly announcing that he could take away all the man's strength and restore it at will. He placed a small wooden box at the man's feet and bade him pick it up. Easily obliging, the volunteer set it back down, scoffing, “Is that all?” (514). Then, with a portentous wave of his hands, Robert-Houdin proclaimed, “Presto! You are now weaker than a woman!” When the man tried to lift the little box a second time, it would not budge. Behind the scenes, stagehands had thrown a switch activating a powerful electromagnet hidden beneath the stage. The strongman struggled in vain. Panting and furious, he began to sulk back to his seat defeated, but shouts from the audience persuaded him to venture a second attempt. This time, however, Robert-Houdin signaled his assistants to pass an electric current through the handle of the box, toppling the stunned volunteer to the floor in a convulsive heap. Regaining his wits, the Algerian dashed from the stage. A ponderous silence fell upon the audience. Robert-Houdin reports hearing murmurs of “Satan” and “genii” passing among the spectators he calls “credulous” (516).Footnote 3

Next, the magician staged the infamous “Gun Trick,” a classic of nineteenth-century magic, hoping to match an alleged indigenous conjuring feat. It had been reported that marabouts, as a proof of invincibility, would sometimes ask followers to shoot firearms at them. After the holy men uttered a few cabalistic phrases, the guns would not discharge. Robert-Houdin reasoned that the marabouts secretly tampered with the firing mechanisms in advance, rendering the weapons useless. French military officers were particularly eager to discredit this kind of false miracle, which they feared could embolden Algerians to defy the occupying forces. When Robert-Houdin announced to the audience that he would perform this stunt, a wild-eyed man shot up from his seat and bounded onto the stage. “I want to kill you,” he announced impertinently (516). An interpreter nervously whispered to Robert-Houdin that this eager volunteer was, in fact, a marabout. Steadfast, Robert-Houdin handed the man a pistol to inspect. “The pistol is fine,” he responded, “and I will kill you” (517). The magician then instructed him to make a distinguishing mark on a lead bullet and load it in the pistol with a double charge of powder for good measure. “Now you're sure that the gun is loaded and that the bullet will fire?” Robert-Houdin asked. The marabout could not but assent. “Just tell me one thing: do you feel any remorse about killing me in cold blood, even if I authorize it?” By this point, the marabout's response was comically predictable. “No. I want to kill you.” The audience laughed nervously. Robert-Houdin shrugged. Stepping a few yards away, he held up an apple in front of his chest, and asked the volunteer to fire right at his heart. Almost immediately, the crack of the pistol rang out. Spectators' eyes darted from the gun's smoking barrel to the place where Robert-Houdin stood grinning across the stage. The bullet previously marked by the volunteer himself was lodged in the apple, which—the magician reports—the marabout, taking for a powerful talisman, would not give back.

In his final trick, Robert-Houdin invited a handsome “Moorish” gallant—in fact a secret accomplice—up from the audience. He stood the elegantly dressed volunteer on top of a table and covered him with a cloth canopy. Just moments later, he tipped the canopy over. The lad had vanished without a trace, having passed through a hidden trapdoor. According to Robert-Houdin, “The Arabs were so impressed that, beset by an indescribable terror, they instantaneously leapt from their seats in a frantic devil-take-the-hindmost scramble for the exit” (519). When the panic-stricken mob reached the door, it was amazed to find the resurrected boy waiting contentedly outside.

After repeating these same feats in a second performance the following day, Robert-Houdin says he instructed his interpreters to spread the word that his “seeming miracles were only the result of skill, inspired and guided by an art known as prestidigitation, and having nothing whatsoever to do with sorcery” (519). He claims an Arab who witnessed his performance was later heard to say, “Now our marabouts will have to work much more powerful miracles to impress us” (524). Several days later, on 5 November, the colony's official French-language newspaper, Le Moniteur algérien, reported enthusiastically on the performances: “Marshal [Randon] considered that showing the Arabs a Christian superior … to their phony shereefs, who have tricked them so often, would encourage them to uncover and frustrate future impostures, and to resist—through knowledge of the cause—their own shameful excitation. May these performances, of which all of Algeria long will speak, have their desired effect!” (reproduced in Seldow Reference Seldow1971: 13).

The following year, a story about Robert-Houdin's mission in the metropolitan newspaper Le Moniteur universel concluded triumphantly: “Today the marabouts are totally discredited among the natives, who, by contrast, hold the famous illusionist as an object of veneration” (reproduced in Seldow Reference Seldow1971: 17). Contemporaries mythologized Robert-Houdin as a modern-day Moses triumphing over Pharaonic magicians (Vapereau Reference Vapereau1859: 335). Years later, another Algerian newspaper recalled Robert-Houdin as the “extraordinary man who spared France much bloodshed and moved colonization forward twenty years” (quoted in Fechner Reference Fechner2002: 59).Footnote 4

A MOST PRECIOUS SOUVENIR

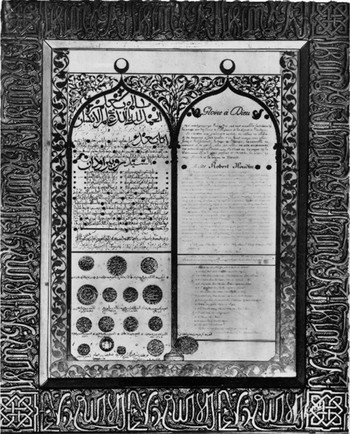

Three days after his second performance, Robert-Houdin was summoned to the governor's palace, where a group of Arab leaders formally presented him with a stunning, gold and turquoise illuminated certificate (fig. 2). Handsomely calligraphed in parallel columns of Arabic and French, the bilingual certificate heralds Robert-Houdin as “the marvel of the moment and of the century.” After Ali Ben el-Hadj Musa, the calligrapher who composed and signed the certificate, declaimed the Arabic text, sixteen chiefs solemnly impressed their seals on the document. A seventeenth seal, from Colonel de Neveu, points to the involvement of colonial authorities in engineering this legitimating transaction. Calling it the “most precious souvenir” of his career, Robert-Houdin (Reference Robert-Houdin1995: 522) introduces the certificate in his memoir as corroborating the success of his Algerian mission. Until only recently, it hung in a museum in his native Blois, seeming confirmation of France's triumph over the marabouts (it has recently been stored for preservation). Examined more closely, however, the certificate proves deeply equivocal.

Figure 2 Ville de Blois.

The Arabic text is a conventional panegyric.Footnote 5 The parallel French translation offers an accurate, idiomatic rendering, without replicating difficult effects of rhyme and meter. (For instance, all end-words in the first paragraph of Arabic verse rhyme with “Robert-Houdin.”) The author makes extensive use of rhetorical formulae associated with formal eloquence: “Our age has seen no one who can compare to Robert-Houdin. The radiance of his talent surpasses history's most brilliant achievements. Because it can boast him, his century is the most illustrious of all.” In a formulaic expression of indebtedness, the signatories promise to “keep [Robert-Houdin's] memory alive, attempting to elevate [their] praise to the level of his merit” and apologize to the magician directly for insufficient ability: “Nature gifted you with rich eloquence and before you, we admit our weakness. Excuse us, if we offer you so little. Is it fitting to offer nacre to one who owns the pearl?” The terms of encomium, while lavishly poetic, do not sound significantly different from compliments Robert-Houdin might have received from contemporary European spectators: “He has stirred our hearts and dumbfounded our minds … . Such feats had never before fascinated our eyes … . Thus, friendship for him has taken root in our hearts, and our bosoms preciously enfold it.” Nothing about this language suggests that the performances evoked supernatural associations and the author neither acknowledges the French project of demystification nor mentions the marabouts.

Quoting the French text of the certificate in his memoirs, Robert-Houdin writes, “I am going to give the translation … as it was done by the Arab calligrapher himself.” Technically, the text he presents is in the calligrapher's words, but Robert-Houdin made significant expurgations, removing phrases and entire sentences, present in both languages, that were potentially discordant with his construal of the situation.Footnote 6 It is unfortunate that subsequent biographers and magic historians overlooked these omissions since much of the French column of text (but surprisingly not the Arabic) has now faded into illegibility. Comparing the parallel texts using archival photographs, I have been able to make out all but a few omitted words. A number of Robert-Houdin's omissions link his magic with intellectual achievement. For instance, he leaves out sentences comparing him to three archetypically learned figures—a Greek philosopher, a Hellenistic magus, and a legendary Persian king: “He seems like a Greek sage. He has the profound genius of Aristotle, the science of sage Hermes [Trismegistus], and the wisdom of Chosroes [i.e., Kisra Anushirwan].” One can only speculate why Robert-Houdin chose to elide these lines, but the effect is to suppress a clear indication that his Arab interlocutors were not just primitive outliers on the fringes of modernity, but heirs to a cosmopolitan literate tradition. Likewise, in omitting a later sentence describing his “accomplishments” as “the obvious mark of his elevated intelligence, his knowledge, and his wisdom,” Robert-Houdin removed a further indication that the Algerian audience unproblematically construed his performances in terms of technical savvy rather than potentially supernatural agency.

Another omitted line gives a concrete sense of how the local Arab elite may have categorized Robert-Houdin's performances. The French text states, “Generous and knowledgeable men went to admire the marvels (prestiges) of his science (science).” Striking this sentence, Robert-Houdin suppressed a description of his performances as entertainments offered in the honor of Arab notables, promoting a more exoticizing narrative. In fact, French officials presented these spectacles as diplomatic prestations intended to mediate the tensions of empire, and the certificate itself can be seen as an extension of this political theater. The Arabic counterpart of this same omitted line conveys an equivalent idea: “He brought the marvels (‘adjā’ib) of his science (‘ulūm) an illustrious group to entertain.” The phrase translated as “entertain” here, “tuslī al-khawāṭir,” could be more literally rendered “divert the thoughts,” and serves to frame the marvelous exhibition as spectacle. The overall connotation is that Robert-Houdin's act was seen as a prodigiously amusing curiosity of knowledgeable performance—not terrifying sorcery as the magician's narration implies.

This brief reexamination of the certificate indicates that Robert-Houdin's performances may have received a somewhat different reception than the triumphalist accounts of the conjuror's memoir and the contemporary French press suggest. Of course, de Neveu's signature points to the difficulty of reading the certificate as a reflection of local reception independently of the different political projects and pressures that may have shaped its composition. Still, it seems clear that by editing the text for publication, Robert-Houdin made his tale as exotic as possible, surreptitiously distancing Algerian perspectives on his magic from the normative, modern ideal. In what follows, I examine how representations of another kind of marvelous performance—the ritual marvels of Algerian ‘Isawiyya Sufis—set the stage for this kind of dichotomizing logic.

A LESSON ON MIRACLES

During his time in Algeria, Robert-Houdin hoped to attend “a conjuring performance by the marabouts or by some other native jugglers” (1995: 525), and expressed particular curiosity about the ‘Isawiyya order, “widely reputed for their marvels” among European travelers in North Africa. “I was sure that all their miracles were nothing but more-or-less clever tricks that I would be able to see right through,” he recalls. De Neveu arranged a performance and, along with their wives, the colonel and the magician visited an Arab house for a hadra, the ‘Isawiyya trance ceremony infamous for its feats of self-mortification (526–27). After the male guests were seated in a large inner court and the women in an overlooking gallery, the ceremonialists filed in and arranged themselves in a closed circle. They began chanting slow prayers and devotions, eventually taking up cymbals and tambourines. The intensity gradually mounted. After approximately two hours, some of the chanters stood and began to yell “Allah!” at the top of their lungs. The mood quickly became paroxysmal. Sweat-drenched devotees shed much of their clothing. Some suddenly dropped to all fours imitating wild animals.

Only when the ceremony had reached this ecstatic peak did the much-anticipated wonder-working begin. Hidden behind a column to better detect any imposture, Robert-Houdin says he observed a number of the feats for which the brotherhood was so reputed. With the muqaddam, or spiritual leader, officiating, some ‘Isawiyya devotees devoured dangerous and inedible substances—glass, rocks, and cactus spines. Some placed scorpions and poisonous snakes in their mouths. Others handled a red-hot iron bar, touching it with their tongues, and walked upon a white-hot iron plate. Others still struck themselves with knives and swords, proving themselves impervious to razor-sharp blades.

Robert-Houdin devoted a long epilogue to his memoirs entitled “A Course on Miracles” to debunking the tricks of the ‘Isawiyya, both those he directly observed and others only reported to him.Footnote 7 As a showman, Robert-Houdin was struck by the highly rehearsed nature of the ‘Isawiyya rite, as evident in both the specialization of individual adepts and in the carefully orchestrated cooperation between them. “Not a soul among [the ‘Isawiyya] has any illusion about the true nature of their phony miracles,” he writes (557). “Indeed, they all help each other produce these feats.” Comparing them unfavorably to second-rate mountebanks, Robert-Houdin systematically demystifies each of their apparent miracles, showcasing his knowledge of illusionary principles: the ‘Isawi who appeared to stick a knife into his cheek was merely stretching his skin with a blunt instrument; the adept who ate the prickly pear spines must have prepared them in advance—“otherwise, he would not have failed to [let us examine them] … thereby doubling his prestige” (559); before laying bare-bellied on a sharpened saber, the devotee turned his back, providing an ample occasion to cover the likely dull blade with a protective cloth; finally, the apparently poisonous snakes the ‘Isawiyya handled were either defanged or altogether harmless varieties.Footnote 8

To Robert-Houdin's eyes, some other feats performed by the ‘Isawiyya relied on scientific principles: while the ‘Isawiyya who swallowed rocks and broken bottles distributed by the muqaddam probably discretely deposited them, in a gesture of prostration, back into the leader's robes, others had unquestionably chewed and swallowed shards of glass. Unimpressed, Robert-Houdin fed an “enormous meatball full of pounded glass” to one of his housecats (561). After the cat survived, he frequently repeated the procedure as a party stunt for friends, eventually consuming (much more carefully pulverized) glass himself. The fire-handlers fared no better against his withering positivism. Robert-Houdin cited research suggesting that a preparation of powdered alum could be used to protect the tongue from extremely high temperatures, much as his own experience confirmed that a thin layer of moisture provides sufficient buffer against red-hot—even molten—metal. Finally, Robert-Houdin reasoned that the frequently barefoot Arabs developed feet calloused “like horses’ hooves,” enabling them to walk on the white-hot iron plate without discomfort (565).

In his memoir, Robert-Houdin substantiates his characterization of the ‘Isawiyya as charlatanic impostors by exposing and explaining the alleged trickery behind the hadra ceremony. In the process, he equates the ‘Isawiyya with the anticolonial, prophetic “intriguers” he says he was sent to discredit (502). This likening seemed to satisfy contemporary readers. Favorably reviewing the “Confidences,” one literary critic wrote: “Hoping to see for himself the marvels of the indigenous prophets, the magician was lucky enough to procure a performance. He includes a chapter … explaining the most alarming tricks of jugglery used to impress the Arabs’ imagination” (Vapereau Reference Vapereau1859: 336). In the next section I discuss how Robert-Houdin and others came to identify the ‘Isawiyya as embodiments of Muslim fanaticism and construct a cultural image of them as the antithesis of secular, modern, Western magicians.

EARLY ETHNOGRAPHIC ACCOUNTS

François-Edouard de Neveu, the figure who orchestrated Robert-Houdin's mission and served as his guide in Algeria, was at the time the leading European expert on popular forms of North African Islam. Significantly, he also appears to be the first to describe the ‘Isawiyya as theatrical magicians guilty of inadequately disenchanting their own trickery. A gifted and well-educated officer, de Neveu took part in the 1839 scientific mission to Algeria, researching the social organization of Algerian Islam (Faucon Reference Faucon1890: 417–18). In 1845, he published a groundbreaking—though far from impartial—field manual on Sufi brotherhoods (Clancy-Smith Reference Clancy-Smith1990: 227), groups that have since become a widely documented feature of North African society.

Briefly stated, these Sufi orders originate in the mystical teachings and techniques of saints whose descendents inherit holy status and spiritual leadership (Crapanzano Reference Crapanzano1973: 15–21; Geertz Reference Geertz1971: 43–54).Footnote 9 While these saints are distinguished for descent from the Prophet, religious insight, and miraculous deeds, similar attributes characterize a broader field of holy men capable of mediating divine grace, whom the French identified as marabouts: “political chiefs, founders and leaders of the Sufi brotherhoods, eponymous ancestors and tribal chiefs, pious men, hermits, healers …” (Andezian Reference Andezian, Popovic and Veinstein1996: 390)—a list which also could include messianic insurgents (Clancy-Smith Reference Clancy-Smith1990: 232). The very term the French variously employed for both the general veneration of holy figures and the regulated religious life of Sufi confraternities—“maraboutism” (maraboutisme)—threatened to distort complicated relationships between messianic leaders and mystical religious orders (Clancy-Smith Reference Clancy-Smith1994), precisely as we have seen in Robert-Houdin's “Confidences.”

De Neveu argued that, due to the influence of Sufi confraternities, what had begun as nationalistic resistance to French occupation was evolving into a religious crusade against Christian invasion. Pointing to their hierarchical organization, transnational and interethnic scope, well-established communication networks, customary secretiveness, and devoted veneration of sanctified leaders, de Neveu portrayed the brotherhoods as a particularly pernicious threat (1846: 194). In the short term, he recommended “constant surveillance” through the infiltration of spies among the adepts. Ultimately, he advocated supplanting radical leaders with the French-educated, and Francophilic, indigenous elite Robert-Houdin's performances were supposed to help create.

After the publication of de Neveu's study, French preoccupation with Sufi orders quickly spiraled into “hysteria” (Clancy-Smith Reference Clancy-Smith1990: 225). Generally speaking, colonial observers were profoundly uncomfortable about what they saw as an interdependence of religion and politics characteristic of Islamic civilization, but the particular aversion to maraboutism was overdetermined by other factors. Lorcin contends that Republican anticlericalism was especially influential in the military academies that trained the majority of colonial officers, who in turn transferred longstanding anxieties about subversive Catholic parish priests to Sufi leaders (1995: 54–59). In addition, prevailing racialist stereotypes led the French to view Algerian Arabs as naïve, irrational fanatics, easily stirred to religious excess by rabble-rousers feigning divine inspiration (60). Given these preconceptions, the ‘Isawiyya, with their apparently false miracles and seemingly unhinged ecstasics, represented a troubling fulfillment of France's orientalist fears and fantasies (Trumbull Reference Trumbull2007), despite there being “absolutely no trace of political involvement from the ‘Isawiyya” (Andezian Reference Andezian, Popovic and Veinstein1996: 397) under either Ottoman or French rule.Footnote 10

As de Neveu (Reference de Neveu1846: 67–68) correctly explains, the order formed in early-sixteenth-century Morocco around Sidi Muhammad Ibn ‘Isa, a saint reputed for piety, asceticism, and miraculous deeds. According to tradition, during a long desert sojourn, Ibn ‘Isa saved his disciples from starvation by enabling them miraculously to eat noxious substances—scorpions, poisonous snakes, rocks, and cacti (92–93). Later, Ibn ‘Isa's avowed adversary the sultan of Meknes challenged the disciples to reproduce this miracle publicly by ingesting large quantities of poisonous and dangerous substances, which they did (102–4). From Morocco, the movement spread eastward, establishing regional outposts throughout North Africa and the Middle East. Especially in Algeria and Tunisia, ‘Isawiyya were reputed for reenacting the miracles of invulnerability associated with Ibn ‘Isa in their ecstatic hadra ceremony.

For de Neveu, these reenactments were nothing but crude legerdemain, harmless in itself, but rendered dangerous because of audiences’ naïveté and penchant for fanaticism.Footnote 11 “In essence,” he writes, “the ‘Isawiyya ceremonies resemble the tricks conjurors and strongmen exhibit in the fairgrounds of France, charming awe-struck peasants, but not convincing them. For there is one fundamental difference: in Algeria the Moslem religion imparts a powerful authority to these tricks, and the true believer thinks that God grants some of his power to the followers of Ibn ‘Isa. By contrast, in France everything unfolds with Mr. Mayor's blessing, and the peasant walks away thinking to himself, ‘Wow, those guys sure are slick!’” (1846: 91).

Making a clear distinction between the performance of trickery under the auspices of laic, temporal power (“Mr. Mayor”) and spiritual power (“the Moslem religion”), de Neveu claims that even the most stereotypically backwards Frenchman—a peasant—would not mistake the virtuosic feats of skilled performers for divine miracles. Ultimately, he concludes that the use of trickery among contemporary ‘Isawiyya constitutes probable evidence that the order's founding saint was not a miracle worker, but an exceptional trickster: “It is difficult not to consider Sidi Ibn ‘Isa himself a consummate juggler, a great prestidigitator, who managed to overwhelm the public with his skill, and who doubtless supplemented his talents as an actor with the exhibition of trained animals” (105–6).Footnote 12

The characterization of Algerian ‘Isawiyya as insufficiently disenchanted magicians proved a resilient topos in colonial ethnography. Louis Rinn, an army officer and the head of the Algerian Service of Indigenous Affairs, calls the ‘Isawiyya “religious fanatics who abandon themselves to … a bizarre form of an ardent, unhealthy, mysticism” (1884: 303) and use trickery “to strike the popular imagination and maintain the superstitious veneration they enjoy” (329).Footnote 13 In a short study of ‘Isawiyya in Tlemcen, Orientalist scholar Edmond Doutté later would agree that the hadra “reeks slightly of charlatanism” (1900: 11) and “prestidigitation” (12), and that the ‘Isawiyya “attract the curiosity of crowds through jugglery” (24). Doutté ends his essay with a recapitulation of Robert-Houdin's performances in Algeria and his demystifications of the ‘Isawiyya's tricks, but questions the overall success of the conjuror's mission: “Robert-Houdin was simply taken as an extraordinary sorcerer, and I doubt that his performances had any other effect. Those who planned the mission obviously did not consider sufficiently that childish peoples like indigenous Algerians are much less surprised by supernatural things. Or, more accurately, they do not distinguish, as we do, between the natural and the supernatural; the notion of the immutability of natural law is unfamiliar to them. Sorcery is, for them, a given; it is therefore easier for them to attribute a surprising phenomenon to occult powers than to offer a scientific explanation” (29).

René Brunel drew a sharp contrast between allegedly degenerate Algerian and Tunisian ‘Isawiyya who “in ecstatic furor stoop to the worst charlatanism” and their relatively austere Moroccan counterparts who “eschew all extravagance, contenting themselves with the state of ecstasy” induced strictly through dance (Reference Brunel1926: 98). These stereotypes of the ‘Isawiyya, particularly in Algeria, as jugglers and charlatans, were well established not only in the pages of colonial ethnography; they accrued widespread cultural support though emergent mass media representations and exhibitionary practices.

EVOLVING ICONOGRAPHY

Lurid reports of the hadra made congenial subject matter for artists; throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, French illustrated newsweeklies ran frequent features on the ‘Isawiyya with complementary engravings. Here, I examine two representative engravings from L'Illustration, France's first mass-market publication of this sort (Martin Reference Martin2006: 24–29). Separated by three decades, these images indicate a significant evolution in style and stance. The earlier engraving accompanies an eyewitness account of an ‘Isawiyya ceremony published in the 27 April 1850 issue. The author, Vivant Beaucé, describes a disorienting, phantasmagorical, nighttime scene: “To illuminate everything, there were only two candles on the ground, and all the people blocking the light … became black shadows, assuming an otherworldly quality” (1850: 263). Accordingly, the artist's rendering obscures the hadra almost entirely: onlookers encircle the ritual space, largely blocking our view (fig. 3). On the left, the muqaddam prepares to heat an iron implement; on the right, we glimpse seated musicians and seven or eight ecstatic dancers. The action in the center seems to correspond to a moment in the narrative when an ecstatic ‘Isawi lunges towards the author: “He rose nearly erect in front of me. His wild eyes, unseeing, bulging from their sockets, the drops of sweat covering his tensed face, the violent gnashing of his teeth, the opening and closing of his fists in nervous spasms, the topknot spread over his shaved head in disordered strands—all conspired to make his person a terrifying image of human unreason. I instinctively leapt up, on the defensive.” Torn between fascination and fear, desire, and disgust, Beaucé struggles to make sense of the ‘Isawiyya. What this drawing illustrates—and enacts—is the frustrated attempt to interpret intractable exoticness. By blocking clear sightlines, it invites viewers to imagine the disturbing ritual for themselves.

Figure 3 Courtesy Firestone Library, Princeton University.

With time, however, a new representational strategy emerged, one that isolated each performance feat as an easily digestible, individual vignette. The later engraving, from the 13 August 1881 edition of L'Illustration, exemplifies this strategy (fig. 4). The sole illustration for a pair of reports on Algeria's Sufi brotherhoods (Ney Reference Ney1881a; Reference Ney1881b), the engraving separately depicts ‘Isawiyya in several phases of a performance for a European audience in Algiers (clockwise from top): ingurgitating cactus leaves; ingurgitating a live scorpion; piercing the cheeks; walking on red-hot iron; dancing ecstatically; and balancing on a sword. In the central frame, an ‘Isawi presents the scorpion to European spectators for inspection; the lower left-hand frame depicts a regal individual identified as “the spectacle promoter.” This image does more than just dissect the hadra. The synecdochical representation of the performance in terms of its most strikingly dramatic moments overshadows its overall religious significance, reframing devotional ritual as sensational spectacle.

Figure 4 Courtesy Firestone Library, Princeton University.

Compare this image to Robert-Houdin's 1849 poster, in which small, framed scenes depict the magician's marquee tricks—a common graphic design element in nineteenth-century magicians’ advertisements (fig. 1). The convergent visual rhetoric of the 1881 image stylistically evokes the iconography of popular entertainment, reinforcing parallels between the ‘Isawiyya and stage magicians. A short text explaining the image underscores this reading: “Is this the work of saints, whose sanctity changes the very conditions of life, or the work of charlatans? It doesn't matter. Whatever the case … their stunts are certainly surprising, and they don't disdain to perform … for roumis [Europeans], and for money” (L'Illustration 1881: 116). It is crucial to recognize that, while deriving from the texts they illustrate, these images also produce meanings and associations of their own, both independently and through intertextual relationships with other images. Taken together, the engravings from 1850 and 1881 reflect an evolving visual idiom that, in tandem with other representational and presentational strategies, conspired to make the ‘Isawiyya hadra increasingly legible as a genre of spectacle.

EXHIBITIONARY RECONTEXTUALIZATIONS

As exotic stories about the brotherhood spread in metropolitan France, ‘Isawiyya performances became popular tourist attractions in North Africa (Trumbull Reference Trumbull2007: 468–70).Footnote 14 Capitalizing on their notoriety, the Parisian World's Fairs of 1867, 1889, and 1900 featured ‘Isawiyya as ethnographic exhibits. Their ecstatic self-mortifications and reputation for charlatanism suited them ideally for a context where ethnographic exhibitions were carefully designed to arouse curiosity about the exotic Other while vindicating France's “civilizing mission” in the colonies (Çelik Reference Çelik1992; Çelik and Kinney Reference Çelik and Kinney1990; Hale Reference Hale2008; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1989). The circulation of narrative and visual representations of the ‘Isawiyya had whet the curiosity of metropolitan spectators and, as audiences flocked to see the Algerians perform their repertoire of marvels firsthand, the Exhibitions provided an impetus for the production of new texts and images.

At least in print, the ‘Isawiyya received a somewhat ambivalent reception in 1867. The romantic chronicler Théophile Gautier (Reference Gautier1867), who had attended a hadra in Blida, Algeria, over two decades earlier,Footnote 15 complained that the “vaguely oriental decor” lacked the mysterious charm of a real “Arab courtyard.” Still, he wrote, “The spectacle, such as it is, maintains a high African flavor, and is well worth seeing.” Dr. Auguste Warnier, an army surgeon turned pro-colonist writer and politician, claimed in a review of the exhibit to feel “sorry that indigenous Algerians … didn't have any specialty more noble, human, and worthy of sympathy for Europeans to admire,” but he was “very happy to see France finally enlightened about the real state of indigenous civilization” in the colony (Reference Warnier and Ducuing1867: 39).Footnote 16 Charles Desprez gives a mischievous account of the ‘Isawiyya's first Parisian appearance:

A kind of hangar—hardly Levantine in appearance—was requisitioned for them on the Champs de Mars. Detailed posters, like those for a comic sketch at the [Théâtre des] Funambules or an operetta at the Folies-Bergères [music hall], announced their sacrosanct exercises. At first, crowds flocked—we've heard so much about them! But Parisians and their foreign guests—Kalmyk, Chinese, or Kamchadal—quickly lost their taste for such savage exhibitions. Women closed their eyes. Men yelled, “enough!” And taking those “enoughs” for “bravos,” our jugglers ferociously redoubled their furor. All fled, and the hall was empty well before the end of the performance (Reference Desprez1880: 202–3).

However shocked Parisians may have been in 1867, 1889 found them as curious as ever about the ‘Isawiyya. After initially performing in the Café Algérien on the Esplanade des Invalides, the ‘Isawiyya soon moved to the more favorable Concert Marocain on the Rue du Caire, achieving “widespread and consummate success” (Pougin Reference Pougin1890: 117–18). On 3 August, Le Figaro reported “Because of the immense success that the ‘Isawiyya now enjoy, the director of the Concert Marocain … has decided to give one performance a night instead of three times a week” (Grison Reference Grison1889). Lenôtre called them “one of the most extraordinary spectacles that one can see at the Exposition … extraordinary if not agreeable” (1890: 276).Footnote 17

Exhibitionary recontextualization of the hadra invited renewed accusations of charlatanism. Branding the ‘Isawiyya “mountebanks” (baladins), the acerbic Pougin wrote, “There is obviously nothing to it but jugglery, even if it depends on one or more secrets that we find impossible to penetrate” (1890: 117). French magicians eagerly stoked suspicions that ‘Isawiyya ceremony was nothing more than an inadequately disenchanted magic show. After witnessing the hadra at the 1889 World's Fair, music hall illusionist and wicked satirist Edouard Raynaly wrote: “In the famous [Algerian Concert], where there were many things, with the exception of music, I had the chance to see the epileptic extravagancies of a bunch of humbugs working their little angle” (Reference Raynaly1894: 215–16). Imputing meretricious motives to the ‘Isawiyya, Raynaly takes great pleasure in divulging what he considered the “crude” secrets behind their feats (216–17). His explanations of many mortifications largely follow Robert-Houdin's text (which he dutifully cites); in accounting for the ingestion of inedible substances, he points to surreptitious substitutions of harmless doubles—for the cactus leaves (219), scorpion (228), and serpent (230)—made under the cover of misdirection. “Thus,” he concludes, “with these facetious Arabs, those who have strong hearts can observe a peculiar kind of prestidigitation. It's not their tricks that I reproach, but the exaggerated importance attached to those tricks and, more than anything, the role they play in fanaticism. When real fanatics—they do exist, alas!—want to go about their mysteries, they do it at home, in a context appropriate to their religious convictions … . They don't cross the sea and act like mountebanks, ballyhooing to attract crowds” (231). While bringing a professional magician's zeal to demystifying what he considered insidious humbuggery, in his ultimate assessment of the ‘Isawiyya hadra, Raynaly seems to have been more disturbed by a fundamental incompatibility between religious ritual and show business spectacle—two performance modalities that World's Fairs aggressively confounded.

The World's Fair engagements gave ‘Isawiyya other opportunities still to exhibit their talents within what During calls the European magic assemblage—“a loose cluster of entertainment attractions based on effects, tricks, dexterities, and illusions” (2002: 215). After the Fair closed in 1889, they remained for some time in France, appearing at the Théâtre Dicksonn, a Parisian illusionist's eponymous magic theater, as headliners of a largely North African review. Ironically, Dicksonn had managed Robert-Houdin's Paris theater for several seasons, but after falling out with Robert-Houdin's daughter-in-law, he opened his rival venue just steps away in the Passage de l'Opéra (Dif Reference Dif1986: 220). The colorful poster from the ‘Isawiyya's engagement there (fig. 5) bills them as “The famous troupe from the Universal Exhibition of Paris,” and as “HOWLING DERVISHES” (in reference to their vigorous devotional cries). It depicts their legendary marvels (along with two other, adventitious acts) in captioned, individual images (clockwise from top): “Balances on the blade of a sword;” “Lying belly-down on the blade of a sword;” “Fire Eater;” “The Belly Dance;” “The Gladiators;” “Pops out his eyes with sharp nails;” “Drives spikes in his mouth and stomach;” and “The Snake Eater.” This attention-grabbing poster is not only remarkable evidence of how the machinery of show business could absorb the ‘Isawiyya's intensely physical displays of religious devotion to manufacture a commoditized, spectacular sensation. It also bespeaks Algerian ‘Isawiyya's resourceful and agentive adaptation to new performance opportunities.Footnote 18

Figure 5 Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY.

In addition to Paris, the ‘Isawiyya performed in London, appearing in 1867 at the Egyptian Hall, a theater famous for its magic acts. An English reviewer warned that the “performing Arabs” would “drive the strongest spectator to brandy-and-water” (Fun 1867). In 1889, they would return to London for an engagement at St. James Hall, playing to mixed reviews. A column in the Era (1889) described the show as “several brown-skinned individuals in Oriental costume” performing, “with a vast amount of ‘moping and mowing,’ roaring and tomfoolery, tricks which are most of them familiar to the patrons of the penny shows at country fairs, and others which, if they were really performed—which is doubtful—were simply disgusting and not at all dangerous.” The reviewer complained that the French impresario who brought the ‘Isawiyya to London “must have sanguine notions of the ‘gullibility’ and bad taste of the British public to believe that an entertainment of so tedious, unnovel, and repulsive a nature can be foisted on Londoners by the accompaniment of hideous tambourining, extravagant pantomime and pretended hypnotism.”

The reaction of the Era's critic suggests that it was not difficult for European audiences to equate the ‘Isawiyya with other cultural offerings on the contemporary stage. For centuries, there had been European entertainers specializing in extreme physical feats, as Harry Houdini (Reference Houdini1920) describes in his book Miracle Mongers and Their Methods, tellingly subtitled: A Complete Exposé of the Modus Operandi of Fire Eaters, Heat Resisters, Poison Eaters, Venomous Reptile Defiers, Sword Swallowers, Human Ostriches, Strong Men, etc. What is more, European spectators could associate the ‘Isawiyya with the vogue for “Oriental” acts by entertainment magicians from India and China, and the burgeoning field of Europeans impersonating them (Lamont Reference Lamont2005; Stahl Reference Stahl, Hass, Coppa and Peck2008). For instance, after attending a hadra, one French traveler in Algeria complained that the ‘Isawiyya could not compare “with the Indian [magician] who, without clothing, without music, without accomplices, without preparation, transforms a dry stick into a flowering bush, a bead into a terrestrial globe, a terrestrial globe into a bead, who knots poisonous snakes around his neck and suspends himself in the air on an iron cane!” (Maire Reference Maire1883: 537).

With ‘Isawiyya touring the European magic circuit, the process set in motion by Robert-Houdin's 1856 trip had come to a logical conclusion. Just as the French entertainer had gone to Algeria where he staged a ritual to enchant French colonial power, Algerian ritual experts came to Paris and London, where they assumed the role of disenchanted entertainers. ‘Isawiyya performances on metropolitan stages enacted an apparent similarity with Western illusionists, confirming suspicions of charlatanism. In the process, they substantiated French perceptions of Algerian Muslims as irrational fanatics. There were, however, dissenting voices. The most sustained critique of deflationary representations of the ‘Isawiyya as lapsed magicians came from an unexpected quarter: esotericism. As I will describe next, several heterodox intellectual and religious movements seized upon the ‘Isawiyya as evidence of claims about the undiscovered potential of occult powers.Footnote 19

BEYOND THE ILLUSIONIST'S ART AND BEYOND THE LAWS OF NATURE

If the figuration of the ‘Isawiyya (and, by extension, maraboutism) as charlatanic complemented France's colonial interests and largely received official support, constituencies with different agendas endorsed competing interpretations. In particular, followers of esoteric movements like Mesmerism, Spiritism, and Occultism hailed the ‘Isawiyya as exemplifying human potentialities unknown to the West. As Monroe (Reference Monroe2008) describes, all these movements shared a common concern with cultivating undiscovered human faculties and abilities at a moment of intense excitement about new scientific discoveries and technological breakthroughs.Footnote 20 These acolytes of the modern paranormal were immensely interested in the ‘Isawiyya and challenged dismissive comparisons of the hadra to Western illusionism.

Mesmerism had a long tradition as an alternative therapeutic practice using “animal magnetism” to unblock the circulation of patients’ “universal fluid” (Monroe Reference Monroe2008: 67). “Magnetizers,” as Mesmerist specialists called themselves, could also use animal magnetism to induce “magnetic sleep” or “somnambulism,” a trance state that “usually entailed a dramatic diminution or augmentation of perceptual or cognitive abilities” (68). For Mesmerists, these phenomena were not miraculous, but rather connected to natural human faculties academic science had yet to comprehend. The Journal du magnétisme, the dominant mid-century periodical of Mesmerism, published several articles on the ‘Isawiyya in the 1850s. In 1854, the journal reproduced a description of a hadra ceremony observed in Constantine. To prepare themselves “for eating snakes, scorpions, broken glass, swords, and a multitude of other indigestible objects,” the author claimed, “they put themselves in a kind of somnambulistic state” through music and dance (du Potet Reference du Potet1854: 353).Footnote 21 While the article established the relevance of the hadra for Mesmeric research on “magnetic phenomena” (355), the Mesmerist critique of discourses equating the ‘Isawiyya with European magicians would not develop for several more years.

In 1857, André-Saturnin Morin—also a proponent of spectacular, American-style Spiritualism (Monroe Reference Monroe2008: 74–75)—published a long article in the Journal du magnétisme, attacking skeptical views of the hadra. In particular, his criticism centers on an eyewitness account of the ceremony by Émile Carrey printed in the 10 April 1856 Moniteur universel. “The author,” Morin writes, “certifies the facts of his arresting account, but, far from sharing the admiration of other onlookers, describes them as one would a fairground spectacle, as if they were simply well executed magic tricks” (Reference Morin1857: 258). Morin's criticism focuses particularly on Carrey's explanation of the Isawiyya's feats, which he quotes as follows:

In regards to explaining these things, the youngest doctor of the smallest village can do it better than me. I will say only that the cactus doesn't hurt; that, under certain conditions well known to chemists (such as moistness, etc.), fire doesn't burn; that the skin of southerners, and particularly negroes, is much more porous and sweaty than that of northerners; and that in South America, I have seen negroes hold hot coals in their hand to light their own cigar or their master's; that the blades of a sword and even a razor do not cut when placed upright; that the human eye can be popped from its socket and reinserted without danger; and that—with apologies to the followers of ‘Isa—their ceremonies, as far as I'm concerned, are perfectly explicable. There's nothing divine about it (260).

Morin sneers at this demystification. “I seriously doubt,” he writes, “that either a city or a country doctor would accept Mr. Carrey's supposed explanation” of the ‘Isawiyya's eyeball feat. “Without a doubt, the eye, removed from its orbit, can be reinserted; what I deny is that this double operation can be performed for pleasure, and that any man in an ordinary state could make a habitual sport of it, without a display of suffering or emotion.” For Morin, writing off the ‘Isawiyya's performances as sideshow charlatanism is arrogance verging on willful ignorance: “That there's no miracle, fine. But what happens is beyond everyday reality, and should excite the attention of everyone interested in deepening human nature. This is a mystery that could put us on the path of an unknown or poorly understood law” (261). Morin explains that Mesmerists can induce comparable states of heightened resistance to pain and physical harm, but that ethical considerations have prevented sustained experimentation. The example of “fanatical” sects like the ‘Isawiyya, he writes, “persuade me that, by augmenting the force of magnetism, we could arrive at similar effects.” He concludes by asking whether the “extraordinary power” the hadra reveals, “instead of giving rise to vain and barbarous entertainments, could be instead applied to produce salutary and grandiose effects, great works to benefit all of humanity. But it is inexcusably flippant to regard these bizarre phenomena with disdain instead of reason, as nothing but magic tricks” (262). Thus, Morin's rejection of the analogy between the hadra and a magic act does not arise from any sympathy towards the ‘Isawiyya, but rather from what he considers the imperative of scientific objectivity.

The publication of Robert-Houdin's memoirs brought Morin back to the subject of the ‘Isawiyya. In an 1859 article, he reviews Robert-Houdin's deflationary account of the ‘Isawiyya hadra, which he calls “very persuasive”: “because the same effect can be produced by different causes, it seems likely that if the supposed miracles of the ‘Isawiyya aren't accomplished using the recipes [Robert-Houdin] provides, they involve analogous, equally natural, methods” (1859: 219). However, he recalls the rapturous ritual of chanting and dance through which the ‘Isawiyya enter a state of “ecstatic exaltation” (220) in preparation for the feats of self-mortification. He suggests that the hadra therefore should be seen as a “combination of conjuring tricks and phenomena of a magnetic sort”—an interpretation he claims Robert-Houdin himself endorsed in private conversation.

For figures like Morin, engaging in debates about the ‘Isawiyya was a means for advancing the intellectual prerogatives of Mesmerism. In this, Robert-Houdin, then at the height of his cultural authority, was a potentially powerful ally, whose support crusaders on both sides of paranormal controversies sought. Earlier in 1859, Paul d'Ivoi appealed publicly to the magician in the pages of the Messager, asking him to debunk French esotericists:

Robert-Houdin … has toppled the sorcery of the ‘Isawiyya and the marabouts of Algiers … . It would be a crying shame if the idiocy of civilized peoples were more difficult to vanquish than the superstition and ignorance of savages. But it wouldn't surprise me. Whatever the case, when Mr. Robert-Houdin decides to, I am sure that he can accomplish all of the miracles that spiritists, mediums, …, magnetizers, somnambulists and other magicians want us to believe in. Mr. Robert-Houdin must only will it, and it would be a great service to his contemporaries (quoted in Morin Reference Morin1859: 221).

Morin dismisses d'Ivoi's “attempt to explain everything by legerdemain” as “a self-evident exaggeration.” Many Spiritualist phenomena—the telekinetic movement of objects, the apparition of phantom members, and human levitations—could never, according to Morin, be produced through trickery: “Whatever opinion one has about these phenomena, we must admit that they are beyond the illusionist's art, and may even affirm that they are beyond the currently known laws of nature.” Morin therefore invites Robert-Houdin to subject Mesmeric and somnambulistic phenomena to careful scrutiny: “The control of conjurors … can be the touchstone for distinguishing gold from glittering fakery; conscientious magnetizers will not shrink from any mode of verification, persuaded that a severe examination can only profit the cause of truth” (222).

Mesmerists were not the only esotericists interested in the ‘Isawiyya. In 1867, an anonymous editor from the Revue Spirite, the flagship journal of the Spiritist movement, went to observe the ‘Isawiyya first-hand at the Parisian Exposition. Spiritists believed that trained mediums could communicate with dead souls, who revealed cosmological insights and moral verities. Like Mesmerists, they had a scientistic outlook, equating the medium as “an innovative religious instrument” with “the innovative scientific instruments that characterized the modern laboratory” (Monroe Reference Monroe2008: 108). They did not regard spirit manifestations as miraculous, but rather as “direct consequences of human physiology,” maintaining that “spirit phenomena appeared to transgress the laws of nature only because human beings did not yet understand the manner in which the body and soul … collaborated in their production.” In the ‘Isawiyya, the Revue Spirite saw evidence of Spiritist understandings of the dynamic relationship between matter and mind, body and soul: “I attended one of the ‘Isawiyya séances myself, and I can say … that it was not a matter of magic tricks, simulacra, or legerdemain, but rather of positive facts, physiological phenomena that derail the most mundane scientific notions … . Since those phenomena are neither miracles nor magic tricks, we must conclude that they are natural effects with an unknown cause, but one that is not unknowable. Who knows if Spiritism, that has already given us the key to so many misunderstood things, could give us this one as well?” (1868: 22–23).

In 1900, the ‘Isawiyya's appearance at the World's Fair again attracted esotericists. That year, a short-lived magazine published by the French Occultist Charles Bartlet produced a sympathetic booklet on the ‘Isawiyya, profiling members of the order then performing in Paris—Unas ‘Abd el-Kadir, a manuscript illuminator; Chula el-Hadj Mohammad, a coffee-shop owner; and Nubia Mohammad ben ‘Ali, a cobbler. In order to control for imposture, the editors assembled modern photographic equipment, along with two medical doctors and “over thirty” other observers “familiar with the trickery of mediums, the subtleties of prestidigitators, and the dexterity of conjurors” (L’Écho de l'au-delà et d'ici-bas 1900: 6). Satisfied by the authenticity of the phenomena they observed, the editors enlisted the help of spirit mediums to shed light on the ‘Isawiyya's superhuman feats. “Fontenelle” and “Julia,” disembodied spirits communicating through female mediums, attributed the ‘Isawiyya's powers to the assistance of spirit beings they identified as “Elementals” (61–69). The editors also consulted a psychic, who corroborated the involvement of Elementals, which he traced to a Sub-Saharan African origin. After the conquest of Senegal, he said, the Elementals had grown hostile and potentially harmful to the French. He continued: “In using them … for religious and often humanitarian purposes, and in employing them among us, the ‘Isawiyya help protect us from … malefic danger” (71). Inverting depictions of the ‘Isawiyya as religious fakes obstructing France's civilizing mission in Algeria, this psychic shockingly construed them as vital intermediaries between incursive Europeans and protective spirits of the African continent.

Among the esoteric movements that flourished in nineteenth-century France, Mesmerism, Spiritism, and Occultism all seized upon the ‘Isawiyya to substantiate claims—both natural and supernatural—about extraordinary human abilities and paranormal powers. It is important to remember that esotericists themselves often faced accusations of charlatanism from the mainstream press, the scientific establishment, and stage magicians. In challenging the representation of the ‘Isawiyya as mere magicians, members of these groups also sought to vindicate their own intellectual positions. That magicians disagreed with them about the authenticity of ‘Isawiyya marvels is not surprising. Beginning with Robert-Houdin, challenging charlatanism and superstition became one of magicians’ central vocational prerogatives (During Reference During2002; Mangan Reference Mangan2007). Crusading against mystics, mediums, fakirs, psychics, and other exponents of the paranormal, magicians sometimes blurred the line between public service and publicity stunt. Disagreements over the ‘Isawiyya thus reflected a growing metaphysical schism that would pit magicians and esotericists as adversaries to this very day (Hass Reference Hass, Hass, Coppa and Peck2008: 26).

DISCUSSION

To this point, I have intentionally avoided anything like an explanation of the ‘Isawiyya performances the French encountered and, in many cases, encouraged during the nineteenth century, focusing instead on patterns of conceptual association within colonial interpretations. These interpretations recur to a single, vexed question: were the ‘Isawiyya fraudulent tricksters, as French illusionists and colonial ethnographers contended, or did they have extraordinary abilities transcending trickery, as Mesmerists, Spiritists, and Occultists maintained? Such questions appear largely peripheral to the project of achieving and transmitting states of divine grace now generally understood as the central object of ritual procedures among the ‘Isawiyya (Andezian Reference Andezian2001: 114), other Sufi orders (Crapanzano Reference Crapanzano1973: 186), local maraboutic lineages (Eickelman Reference Eickelman1976: 160), and mystical trance groups (Kapchan Reference Kapchan2007: 33) in the Maghreb. In the period under consideration, however, an abiding preoccupation with adjudicating the authenticity of ‘Isawiyya marvels (and by extension, the sincerity of the ‘Isawiyya themselves) eclipsed ethnographic investigation of how these marvels were locally understood to function and signify in both contexts of traditional performance and intercultural contact zones. Taussig identifies a similar insistence on falsification in early twentieth century ethnographic representations of shamans who employed legerdemain in ritual settings (2003). Branding the shamans “frauds,” European observers reinscribed an Enlightenment opposition between tricks and reality under the “assumption that there [was] some other world out there beyond and bereft of trickery” (278).Footnote 22 My central concern here has been to explore the role of popular forms of magical entertainment in supporting this metaphysical assumption and providing a model for thinking about certain kinds of ritual as empirically falsifiable.

The French figuration of the ‘Isawiyya as charlatans involved what scholars of metaphor and analogy call “mapping” from the familiar “source” (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1993) or “base” (Gentner Reference Gentner1983) domain of entertainment magic to the novel “target” domain of an exotic ritual. The mapping of magic onto the hadra hinged on an outward resemblance between two genres of performances involving the spectacular display of seemingly superhuman abilities, but it also entailed the analogical inference that the ‘Isawiyya were religious charlatans, presenting techniques Europeans easily categorized as tricks for sacramental veneration. In essence, French accounts treated the marvels of the hadra as the performed equivalent of fetishes at a time when social theorists understood fetishism as the most primitive form of religion, based on the worship of a material thing with “no transcendent meaning beyond itself, no abstract, general, or universal essence with respect to which it might be construed as a symbol” (Masuzawa Reference Masuzawa2000: 248). Denying the possibility of more complicated symbolism or efficacy, de Neveu imagined that the religious awe indigenous Algerians attached to marvels like the ‘Isawiyya's could be easily transferred to high-tech trickery of a Western magician.

From a range of possible readings, nineteenth-century French depictions of the hadra consistently emphasized unfavorable comparisons with stage magic in a way that maximally distanced the symbolic and religious content of Isawiyya ritual practices. Of course, the selection of illusionism as the source domain for this ethnographic analogy was ideologically overdetermined. Wiener argues that, within a colonial framework, “the ‘irrationality’ of native superstitions and practices was necessary to demonstrate the rationality of modern European institutions” (Reference Wiener, Meyer and Pels2003: 140). French discourses accordingly seized upon the foil of illusionism, making an invidious comparison between an indigenous ritual system caricatured as pathologically enchanted, and a European entertainment genre figured as normatively disenchanted.

The analogy with magic was not ineluctable. For instance, a number of authors drew connections with the convulsionaries of Saint-Médard, eighteenth-century Parisian Jansenists famous for séances involving cataleptic trances (Kreiser Reference Kreiser1978) and extreme mortifications—beating, stabbing, burning, and eventually even crucifixion (Maire Reference Maire1985).Footnote 23 As I demonstrate above, Mesmerists, Spiritist, and Occultists proposed analogies of their own, likening the ‘Isawiyya to Western mediums capable of channeling unknown human abilities. Despite the availability of these alternative source domains, however, the analogy with entertainment magic largely dictated the terms of discussion about the ‘Isawiyya, spawning ceaseless debates over authenticity and fraud. Enactments in print and performance, from artistic renderings to ethnographic exhibitions, reinforced the fittingness of this analogy, assimilating the ‘Isawiyya to the modern magic assemblage. This is a pattern with clear parallels in other imperial settings, such as British Nigeria, where “the colonial perspective on native rituals and traditions transformed them into spectacles through categorical reframing, altering the context and projecting the object into wider spheres of circulation” (Apter Reference Apter2002: 589). It is important to recall here that these conceptual and institutional associations with spectacle, however denigratory, also allowed ‘Isawiyya to cultivate new performance possibilities, addressing displays of skill and devotion to ever-wider audiences.

Baudelaire wrote, “Only an unbelieving society would send Robert-Houdin to turn the Arabs from miracles” (Reference Baudelaire1887: 77). The poet implies that employing a magician to wage symbolic war on the reputation of saints does not suggest a high view of religion. It does, however, suggest a high view of magic. Though often dismissed as culturally trivial (During Reference During2002: 2), Western illusionism emerges through the extraordinary sequence of events I have examined here as a potent signifier of modernity, particularly in terms of the specific cognitive outlook and interpretative practices associated with it. Stage magic provided colonial officials a convenient interpretative framework for ethnographic descriptions of the ‘Isawiyya and a sensational mode of imperial spectacle. Equating the hadra with illusionism gave the French compelling evidence of Algerians’ primitive credulity, while diacritically confirming their own characteristically modern incredulity—a stance indissociable from Western magic as a form of entertainment.Footnote 24

As a form of entertainment, modern magic requires audiences to implement a culturally specific interpretive repertoire—indulging in awe but imagining naturalistic explanations for the magician's effects. From the normative perspective of Western modernity, it is therefore a genre of performance capable of confirming the cognitive skills of modern subjects and revealing the cognitive deficiencies of non-modern subjects. In this article, I have traced the symbolic work the French applied to mapping the model of illusionism onto the ‘Isawiyya by disregarding local interpretive norms and framing the hadra as a performance of legerdemain soliciting causal explanations. Attributions of fanaticism and superstition to Algerians made it possible to imagine them as incapable of explaining performed wonders in terms of anything but the crudest supernaturalism. This, in turn, justified not only the deployment of a stage magician to fight maraboutism, but also the categorization of the ‘Isawiyya hadra as charlatanism in ethnographic literature, and its recontextualization as spectacle in exhibitionary spaces.