INTRODUCTION

In 1895, the German former missionary, amateur architect and Orientalist Conrad Schick published an original map of Jerusalem in the Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins, the chief journal of German Holy Land studies. Cribbing from the first “scientific” map produced by the British Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) three decades prior as well as drawing upon his half-century of residence in Jerusalem, Schick's map documented the city's expansion and was otherwise unremarkable save for one unique characteristic. In addition to the four quarters of the walled city that already had been labeled in the PEF's map as “Mahometan,” “Jewish,” “Christian,” and “Armenian,”Footnote 1 Schick's map also featured a “Gemischtes Quartier”—a “mixed quarter.” Although he failed to comment on this cartographic innovation in his accompanying text, this was the first published map that recognized that there were areas of Jerusalem where demographics and space did not neatly overlap.Footnote 2

Schick's map was largely ignored by his fellow Orientalists and cartographers and instead the PEF's formulation continued to dominate for decades as the basis for the city's maps. In many respects, this is an understandable product of the Weltanschauungen of the time, when religious, ethnic, and racial difference underpinned European conceptions of state and society and ethnographic maps became a tool of empire- and nation-building.Footnote 3 Simultaneously, urban segregation was becoming increasingly promoted, legislated, and normalized across the world, as a policy of imperialism and settler colonialism but also as a result of mass migration, urbanization, industrialization, and the institutionalization of racism.Footnote 4 The unease that European observers repeatedly expressed at the messy taxonomies of other heterogeneous Ottoman and Levantine cities such as Istanbul, Salonica, Izmir, Beirut, and Jaffa stemmed from these worldviews and contributed to a lasting desire to place Jerusalem's residents in neatly sealed quarters.

Indeed, over the course of subsequent decades, numerous local actors had a vested interest in passively ignoring or actively erasing the messy demographic-geographic seepage in Jerusalem that Schick had quietly pointed out. After the British occupation of Jerusalem in late 1917 and its subsequent mandatory regime over Palestine, colonial urban policy institutionalized the PEF's confessionalization onto the Jerusalem landscape.Footnote 5 In addition, Zionist ideology and urban policy as well as Palestinian nationalist expression further solidified a vision—and increasingly, a reality—that insisted on a city and country comprised of hermetically sealed, nationally-pure spaces and groups.Footnote 6 The subsequent division and “unmixing” that took place during the course of the 1948 war, during which Jerusalem was divided militarily in two and ethnically cleansed on both sides, rendered Schick's earlier mention of urban mixing little more than a historical footnote.Footnote 7

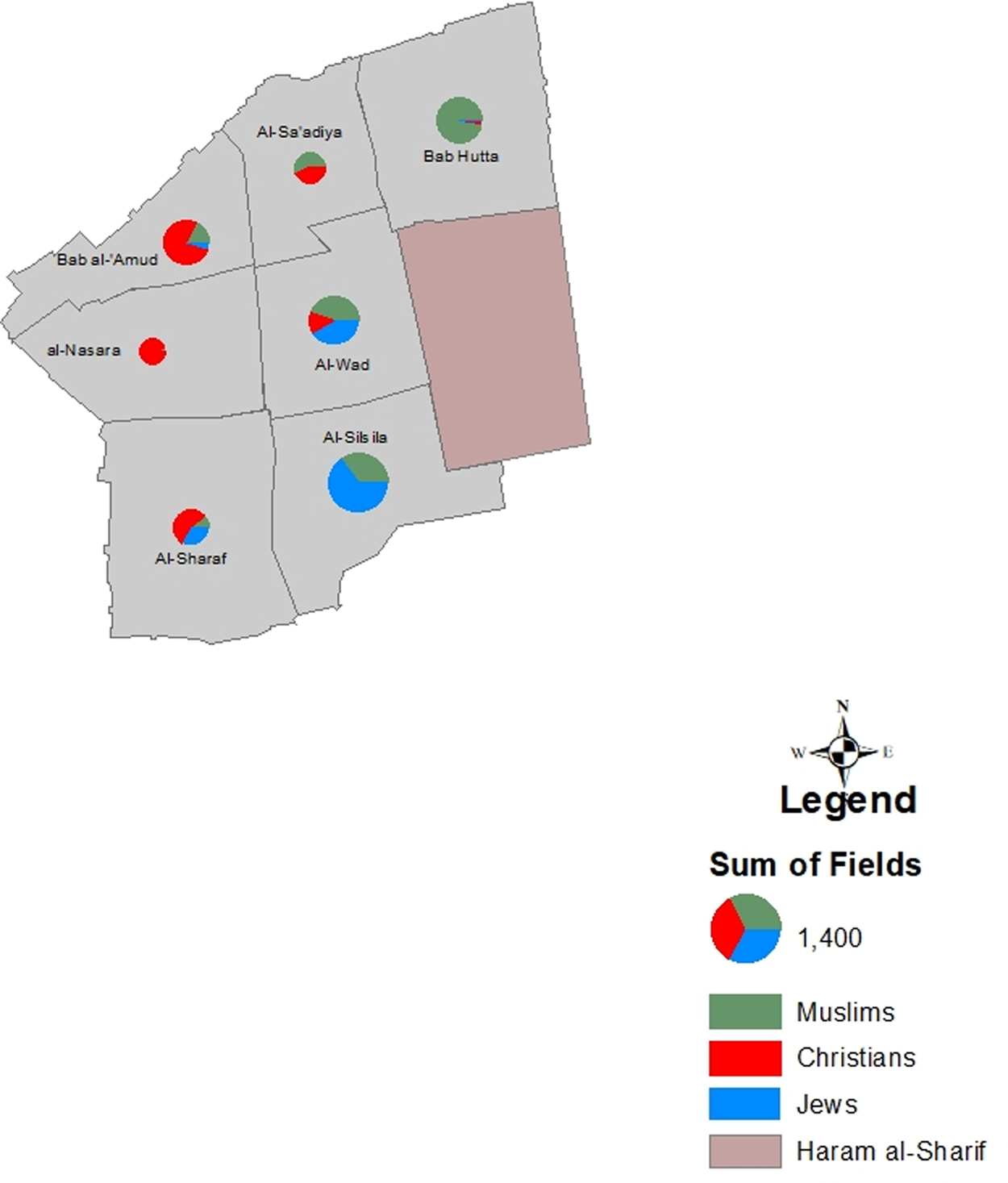

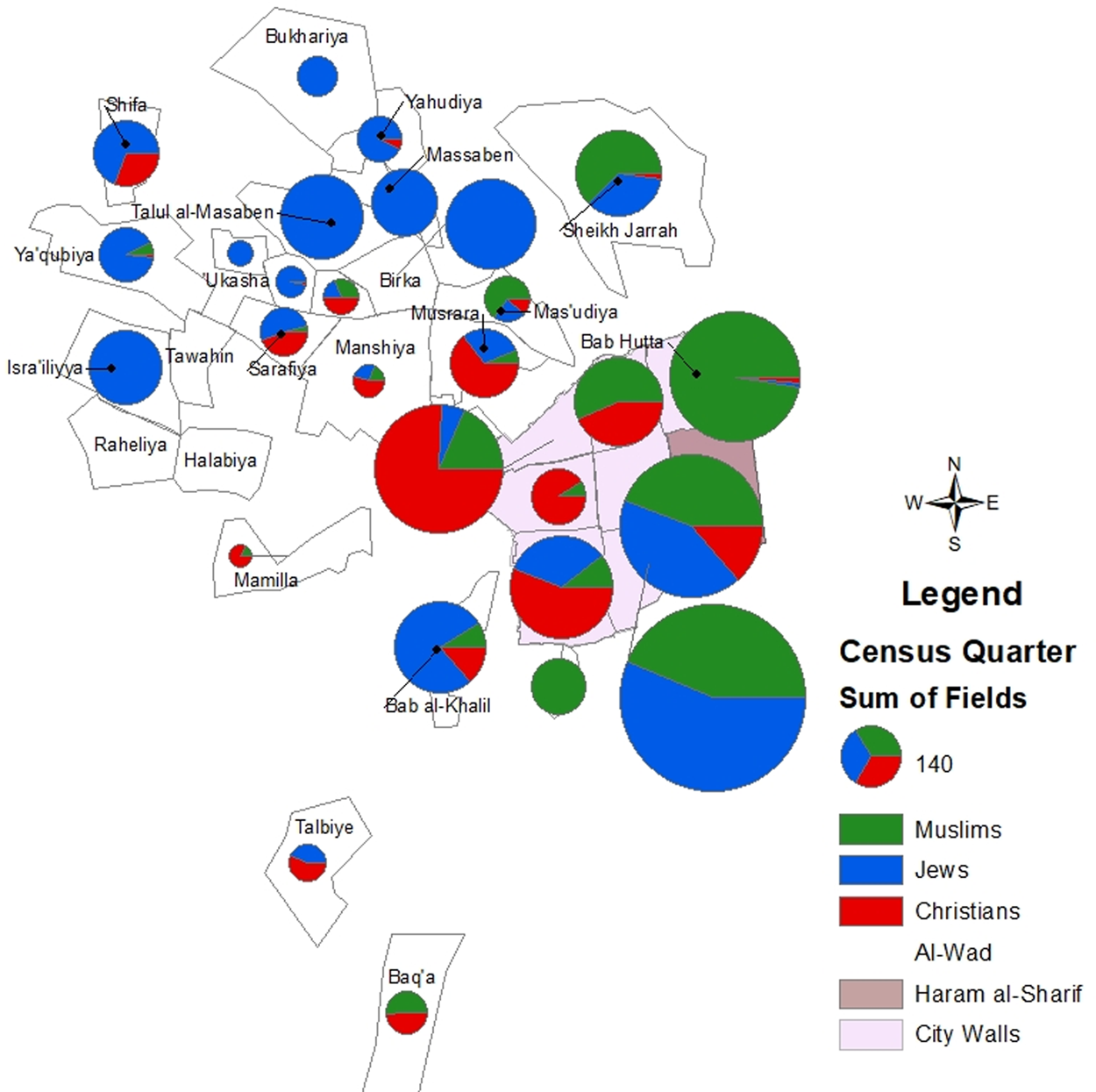

The current state of the historiography, in which a relational history approach that places Arabs and Jews in the same historical, territorial, and conceptual space has become dominant,Footnote 8 as well as methodological advances in spatial analysis make this an opportune moment to dust off Schick's map and subject it to further scrutiny. Demographic analysis of the Ottoman census taken within the same decade not only validates Schick's observation of a “mixed quarter”Footnote 9 at the center of the city, but further reveals that the other four quarters that Schick and other European cartographers routinely delineated as “Muslim,” “Christian,” “Armenian,” and “Jewish” actually concealed heterogeneous neighborhoods in which lived sizable numbers of residents from religious groups other than that of their presumed eponym.Footnote 10 As we see in figure 1, only two of the seven intramuros neighborhoods were characterized by extreme religious homogeneity exceeding 85 percent, whereas the other five were characterized by a moderate (20 percent) to substantial (45 percent) residential heterogeneity. Expanding beyond the city walls (figure 2), the Ottoman census also shows that while the extramuros city was developing along different lines with quite a number of new ethnically or religiously homogeneous compounds and settlements, nevertheless overall two-thirds (66 percent) of the city's Ottoman population lived in mixed neighborhoods.Footnote 11 In other words, the census records reveal that far from being the only mixed neighborhood in turn of the century Jerusalem, al-Wad was simply the most mixed of them all, what one group of sociologists would classify as a “pluralism enclave.”Footnote 12

Figure 1. Old City according to the 1905–06 Ottoman census, scaled to size. (Schmelz aggregate data; author's mapping.)

Figure 2. Jerusalem religious groups according to the 1905 Ottoman census, scaled to size. (Schmelz aggregate data; author's mapping.)

How does this remapping alter our understanding of the city's history specifically and of Ottoman intercommunal urban relations more broadly? At first glance, these modified maps appear to complement revisionist approaches to Jerusalem's history that characterize it as “cosmopolitan,” “diverse,” and “mixed,” emphasizing episodic and sustained connection and interaction between Arabs and Jews,Footnote 13 as well as strengthening a view of Ottoman urban pluralism that has become prevalent in recent decades.Footnote 14 However, it bears remembering, as the critical cartographers have warned, that all “maps lie.”Footnote 15 In fact, while these modified maps do refute the PEF's simplistic “four quarters” formulation, they fail to challenge some of the PEF's broader cartographic and conceptual lies about identity, space, time, and agency in the city. Namely, they continue to homogenize diverse social groups under a religious umbrella, flatten Jerusalem's neighborhoods and streets into discrete administrative units, ignore synchronic and diachronic movement through the city, and obscure causes and effects of these settlement patterns. In short, on their own, these maps tell us little about the history of urban heterogeneity inside these various neighborhoods. Instead, they should be used as a starting point to further interrogate the nature of ethno-religious diversity in the late Ottoman city, in particular around the question of urban “sorting” (where people settled in the urban landscape) and the subsequent consequences for urban life and social networks.

To that end, this article examines residential patterns and intercommunal life in the quintessential “mixed quarter” of fin de siècle Jerusalem, the al-Wad neighborhood. I return to the original Ottoman censuses (of 1883 and 1905) to understand the social make-up of the residents of the neighborhood and to reconstruct the neighborhood as a social space. Then, through a series of GIS-generated maps I re-embed al-Wad's residents in their spatial environment.Footnote 16 By disaggregating the city and shifting the scale of analysis between the neighborhood, street, and building levels, residential mixing in al-Wad is revealed to be much more contingent, partial, and bounded than the overall picture of “mixedness” suggests. Put plainly, Ottoman al-Wad emerges as both a highly integrated and deeply segregated neighborhood. The highest levels of segregation are seen at the building level, but street- and quadrant-level patterns of clustering and concentration are also visible.

Drawing on communal and legal sources, I then explain the various structural and opportunistic factors that contributed to these urban patterns. Religious law and religious institutions played an important role in both deliberately and inadvertently extending religious boundaries from the spiritual to the spatial and made a lasting imprint on the Jerusalem landscape. At the same time, we find that religion was not the only force that mattered: ethnic and national origin, length of time in the city, and social class also played important if uneven roles in urban sorting. I conclude by considering the meaning of social space in the late Ottoman city. The census alone cannot account for the wide variety of contact and interaction that took place outside of the residence, nor can GIS maps fully capture these contexts, relationships, and dynamics.Footnote 17 Memoirs, court cases, and the press suggest additional ways in which physical patterns not only restricted or enlarged zones of contact between and within religious and ethnic groups, but more importantly, they reveal how these zones of contact were central to the flattening and congealing of religious and ethnic boundaries themselves. While these important qualitative and conceptual aspects are neither visible in the census nor fully mappable, together they help to more concretely historicize the structure of Ottoman cities, the experience of different groups in the Ottoman urban landscape, and the urban “ecosystem of interaction”Footnote 18 in which they participated.

SORTING THE LATE OTTOMAN CITY

Most of the scholarship on urban sorting is focused on segregation, the physical separation of groups from each other in the urban landscape based on ethnic, racial, religious, or economic criteria, which could be coercive or by choice.Footnote 19 The Ottoman Empire did not forcibly separate religious or ethnic populations through a ghetto or mellah, like in Europe and Morocco, respectively, but it is clear from the robust historical scholarship that the experiences and interactions between religious and ethnic groups in Ottoman cities varied considerably across imperial space and time.Footnote 20 In certain rare circumstances government policy restricted the residence of non-Muslim communities on a localized scale,Footnote 21 while in many Ottoman cities, preexisting patterns of residence, endogamy, and preferences for proximity to religious institutions and fellow coreligionists established and reinforced geographic concentrations and even some spatial separation of religious groups.Footnote 22 At the same time, many Ottoman cities also contained mixed neighborhoods comprised of several religious and ethnic groups.Footnote 23 Property sales and other legal records have allowed us to gain important insights on residential housing patterns in some cities and eras,Footnote 24 but demographic and spatial analysis of these cities and their urban patterns remains limited.Footnote 25

Residential segregation is only one part of the puzzle, of course, and looking at other urban contact zones and measures is also important for understanding intercommunal relations in the Ottoman city. As Ottomanists have shown, residents worked and shopped in the same markets, sued and were sued in the same courts, and utilized many of the same public and leisure spaces.Footnote 26 At times, public spaces such as streets and squares were confessionalized in practice, and the erection of physical, symbolic, or other borders and boundaries was a meaningful mechanism underpinning and limiting Ottoman urban heterogeneity.Footnote 27 The original Ottoman censuses of the late nineteenth century thus offer exciting possibilities not only for reconstructing residential spaces but also for juxtaposing residential with commercial and public spaces.

In the early 1880s, the Ottoman Ministry of Interior instructed provincial officials to begin collecting population figures for the first empire-wide census (nüfus).Footnote 28 In order to facilitate tax collection and administration, Ottoman officials collected census information according to millet (an ethno-confessional/religious category) that they recorded in separate notebooks.Footnote 29 The mukhtar (selected representative) of each millet was responsible for keeping records of his coreligionists in order to collect taxes, appear in court as a witness, and otherwise contribute to maintaining urban stability. Beyond its governmental purpose, millet belonging also had some practical repercussions, since personal status matters such as betrothal, marriage, divorce, inheritance, and the like were governed by the relevant ecclesiastical or rabbinical law. In addition, members of different millets often worshipped in different churches and synagogues, studied in different schools, and maintained their own charitable and communal institutions.

At the same time, it should not be assumed that millet was the sole or primary “group” to which one belonged and around which all individual, collective, and urban life was structured.Footnote 30 Millet membership was not immutable, but rather could be and often was changed strategically. Throughout Ottoman history, individuals, extended families, and in some cases entire villages joined a different church or converted to a different religion for strategic, spiritual, and personal reasons alike. In other cases, millets fragmented and broke apart in order to secure additional administrative, legal, or financial privileges or communal autonomy.Footnote 31 Important recent scholarship has highlighted the various ways that millet belonging intersected with other communal identities—ethnic, professional, regional, and imperial.Footnote 32 For example, İpek Yosmaoğlu's fascinating work on late Ottoman Macedonia analyzed the multifaceted politicization of millet, religion, ethnicity, and nation, as well as the distinctly modern role of violence in this process; in that case, the census registration process itself was highly fraught as peasants were forced to choose between “Rum” (Greek Orthodox) and the relatively new “Bulgar” millet categories, while others pushed for non-millet terms like “Serbian” or “Vlach” that were being vested with new political meanings.

Dealing with a slightly later period, Sarah Shields shows that postwar Mosulis found colonial ethno-national labels (“Arab” or “Turk”) to be incomplete or unnatural in their multilingual and multiethnic society; these categories flattened the importance of the social space of the neighborhood (mahalle) in Mosuli's self-perceptions and social relations.Footnote 33 Late Ottoman Jerusalem did not have the same circumstances of nationalist and colonial agitation as did Macedonia and Mesopotamia, respectively, but these cases serve as an important reminder that while we pay attention to the social and political use of millet, we should not project an all-encompassing character nor should we ignore the impact of social space on collective identities.

In fact, by privileging the millet as the administrative category of recording the census, Ottoman officials inadvertently or deliberately obscured the geographic and social proximity of Jerusalem's residents. Neighbors on the same street resided divided among up to eight different notebooks, and instead “naturally” resided in the state's mind alongside their coreligionists who might live in a separate part of the neighborhood or even in a distant part of the city. Part of the imperative of re-embedding Jerusalem's residents into their urban landscape, then, is to undo this administrative erasure and to uncover the social and historical implications of geographic proximity of Jerusalemites of different ethnic and religious origins. Let us now return to our neighborhood in question.

OTTOMAN AL-WAD

In the last half of the nineteenth century Jerusalem was a city in the throes of ambitious imperial reform, geopolitical wrangling, and tremendous urban change.Footnote 34 The city's busy markets housed over nine hundred shops that provided food from neighboring villages, household supplies and raw materials from the region, and imported luxury goods. A building boom was beginning to transform the landscape, especially outside the sixteenth century walls; while it was most visibly dominated by the large foreign churches, hospitals, and schools, there was also a great deal of residential construction contributing to Jerusalem's expansion and growth.

Against this backdrop, in the 1883 census, Ottoman officials counted over four thousand households of Ottoman subjects (more than seventeen thousand people) living in eight intramuros neighborhoods in Jerusalem. Of the city's population, Muslims constituted the plurality, at 38 percent, Jews comprised 35 percent, and Christians 27 percent.Footnote 35 From the registers we can see that some of these residents were migrants to the city, having arrived in the 1860s and 1870s, although no comprehensive figures have yet been calculated for this period.Footnote 36 Census officials only recorded Muslim Jerusalemites within their respective neighborhoods, while Christian and Jewish Jerusalemites as well as “foreigners” (yabancılar)Footnote 37 were collected in separate notebooks without any spatial indicators. As a result, from this first census we can draw only a partial portrait of the urban distribution of the city's permanent residents in the early 1880s.

Located in the center of the walled city, al-Wad was a significant center for political, religious, economic, and intellectual life in Jerusalem.Footnote 38 Comprising approximately fifteen streets in total with a 1.3 kilometer perimeter, al-Wad was bounded on the east by the Ḥaram al-Sharif complex (The Noble Sanctuary, which included the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa mosques) and on the west by three parallel markets, and was sandwiched between the Bab al-‘Amud quarter to its north and al-Silsila quarter to its south. Its designation as an administrative unit as well as a neighborhood (“Vad mahalesi,” or “mahallat al-Wad”) appeared in government documents, shari'a court records, and municipal registers by the mid-nineteenth century, but the neighborhood's boundaries were not always consistent, with the border streets at times reported as belonging to the adjacent neighborhoods.Footnote 39

The Ottoman administrative offices, the Islamic courthouse, and the prison were all located within al-Wad. Scattered throughout the neighborhood were several important as well as more minor Muslim, Christian, and Jewish religious sites and schools: Sufi zawiyas, mosques, madrasas, and shrines, several Stations of the Cross, and synagogues and religious schools. The neighborhood boasted several public water fountains as well as three public baths, an important consideration in a city which then had no running water and relied on private cisterns, wells, and spring water purchased from water carriers. Commercial spaces and workshops were interspersed throughout the neighborhood on major streets, which provided for both residents’ daily needs as well as employment, along with charitable institutions like a soup kitchen and orphanages that aided the neighborhood's and city's needy. Furthermore, at least three cafés were located in al-Wad or on its edges; they were not only sites for social gatherings, but also places where people came to read or hear about local, imperial, and international news, to gossip, and to be entertained.

In the 1883 census, al-Wad appeared as the fourth most populous neighborhood in the city, with 242 Muslim households totaling over sixteen hundred people.Footnote 40 The vast majority of these households, 85 percent, were headed by native Jerusalemites, and another 7 percent of household heads had arrived from other towns in Palestine. The remaining 6 percent of household heads were from neighboring Ottoman provinces, including Egypt, Sudan, and greater Syria. These residents were professionally and socioeconomically diverse, with household patriarchs working in crafts guilds, the provision of foods, governmental and religious office, commerce, and the service industry.Footnote 41 The extended family appears to have been critical to the economic and social lives of the households and neighborhood: many households consisted of several related nuclear family units, and marriage within extended families was widespread. Overall, in the pages of the census, mid-1880s al-Wad appears as a tightly knit, all-Muslim neighborhood, heretofore not visibly affected by global transformations.

However, this census portrait obscures important transformations that were already well underway. Jews began moving to al-Wad by the 1850s as spillover from the neighborhoods to its south where Jewish community life had been concentrated for over three hundred years.Footnote 42 Islamic court records show that between 1868–1875 at least a dozen Jewish families purchased homes in the neighborhood. It is reasonable to assume as well that there were already a number of Jewish renters in the neighborhood.Footnote 43 Indeed, individual Jewish residents of al-Wad pop up in a variety of other court cases in these decades, as investors or landlords registering power of attorney, widows suing for their inheritance, pious philanthropists dedicating property, divorcees requesting child support, or residents giving witness testimony. Additionally, several Jewish communal institutions had already taken root in the neighborhood in this period, such as the North African (Maghrebi) Jewish community compound that was built in the late 1860s with a synagogue, religious school, and residences for the poor, as well as several Ashkenazi Jewish institutions.Footnote 44 Thus, despite its erasure in the census records, there is substantial evidence that by 1883 al-Wad already had a religiously and ethnically diverse population.

Over the next twenty years, both al-Wad specifically and Jerusalem generally underwent even more significant demographic, physical, economic, and political transformations. The new railroad from Jaffa facilitated transportation to the city and brought thousands of pilgrims and foreign tourists annually. Because several stations on the Via Dolorosa were located at the edge of the neighborhood, as were several Muslim Sufi hospices and the Austrian hospice, al-Wad's residents must have seen a substantial seasonal flow of international visitors. More importantly, there was a huge increase in (im)migration to Jerusalem in the 1880s–1890s.Footnote 45 While we have scant autobiographical data about most of these migrants, we can surmise that they came for a variety of economic, religious, political, and personal reasons.Footnote 46 Government clerks and soldiers, students, slaves, servants, brides, laborers, and merchants circulated in an intra-imperial network connecting Jerusalem to neighboring Ottoman provinces. In addition, the incorporation of the Middle East into the world economy resulted in an increased circulation of international immigrants from Eastern Europe, Africa, and the Islamic East who arrived in Jerusalem in search of economic success or spiritual succor.

As a result of this rapid growth across the empire, new imperial regulations were issued in 1901 to begin a second round of census registration, which took place in Jerusalem in 1905 (1321 in the mali calendar). The Ottoman government both incentivized participation and punished lack of participation: census registration was a prerequisite for receiving the nüfus tezkeresi, a vital government document necessary for school registration, land purchases, court appearances, and passport applications, among other things. Shirkers were threatened with fines, imprisonment, and deportation.Footnote 47 As a result, public compliance was widespread even if, presumably, not absolute, with participation from elites to the middle and artisan classes to the unemployed and poor, and on to the native-born, long-term residents, and even recently arrived immigrants.Footnote 48 Foreign citizens, though, were once again excluded from the count, although consular records suggest that up to ten thousand of them lived in the city by this point.Footnote 49

By that time, the Ottoman population of Jerusalem had almost doubled to comprise over thirty thousand individuals in over seven thousand households, with Jews now constituting the plurality (41 percent), followed by Muslims (34 percent) and Christians (25 percent). Over a quarter (26 percent) of all heads of household had been born outside the city.Footnote 50 During these two decades, al-Wad had grown to become the second most populous neighborhood in the city overall—over 3,400 inhabitants now lived there in 748 households.Footnote 51 Thanks to a change in the census procedures that recorded the neighborhood of all Ottoman residents, including Christians and Jews, we can learn a great deal more about the neighborhood and its residents at this moment in time, not least the major attributes recorded in the census: millet, place of birth, and occupation.

The residents of al-Wad belonged to eight different millets, closely divided between Muslims (44 percent) and Jews (42 percent), with the remaining being Christians. (The specific millet breakdown is reproduced in table 1.) It is clear that al-Wad at this point was an immigrant-heavy neighborhood, with nearly half (45 percent) of its households headed by a migrant to the city or an immigrant to the empire, a rate that was almost twice as high as for the city overall (table 2 shows the region of origin of al-Wad's household heads).Footnote 52 While we do not know exactly when most of these immigrants arrived in the city, or for that matter in the neighborhood, at least one hundred al-Wad household heads arrived in Jerusalem within the preceding decade, while eighty households had resided in Jerusalem for between two to five decades (table 3 shows estimated decade of arrival).Footnote 53

Table 1. Millet of heads of household (HoH) and female heads of household (HoH-f) in al-Wad, 1905 Ottoman census.

Table 2. Region of Origin for al-Wad households, 1905 Ottoman census.

Table 3. Estimated decade of arrival for al-Wad immigrant households, 1905 census.

From this breakdown, it is apparent that “immigrants” or “non-natives” cannot be treated as a single group, because the difference was likely stark between the old-timers and the newcomers in terms of language, employment, marriage, and other social networks. Some of these migrants and immigrants undoubtedly became culturally and socially embedded in the life of their neighborhood and the city, and family, professional, religious, or ethnic communal networks helped integrate them further. Although Jerusalem was a multilingual city in many ways, acquisition of Arabic was an important practical skill and a marker of acculturation; at least seven Russian-born Ashkenazi Jewish heads of household in al-Wad, including the mechanic Nissim Levi and carpenter Moshe Grubsky, reported the ability to speak Arabic, presumably at least enough to communicate for their professional needs.Footnote 54

Marrying a local Jerusalemite was also a critical strategy for unmarried newcomers looking to create or solidify their urban social networks. This was the case for most of the non-native Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox men residing in al-Wad, as well as significant numbers of immigrant Jewish and Muslim men, with one major exception. Sub-Saharan African Muslims in al-Wad typically married women from their hometown and rarely married Jerusalemites, and then usually only if the woman was the daughter of an African father. Thus, although sub-Saharan Africans were administratively folded into the Muslim millet, it is likely that both race and class were factors that marked them in Jerusalem and contributed to a certain degree of social difference or perhaps even marginalization. As we will see, this is further borne out by their occupational status and spatial location in the neighborhood.

Scattered occupational and household composition data provides clues about the socioeconomic status of the residents of al-Wad. They were a diverse lot, ranging from notable families heavily involved in commerce, government administration, and religious office, to the new middle class of teachers and translators, to skilled artisans, unskilled manual laborers, and the unemployed poor. That said, it is difficult to determine the financial status of the neighborhood's residents based on their reported occupation alone, and unfortunately we do not have records of housing costs in the neighborhood. Very few residents listed full-time servants as residing in their household, although certainly at least some must have employed day servants who lived in their own households. We can also determine that to a notable extent immigrants and migrants occupied the lower rungs of the economic ladder in al-Wad. Manual labor was dominated by non-Jerusalemites at an overall rate of 2:1. Among Greek Orthodox Christians, this was even higher: almost all of the Greek Orthodox manual laborers (17 percent of Greek Orthodox HoH) were non-locals. The case was even starker for Muslim migrants from sub-Saharan Africa and the non-Ottoman Islamic world, who were virtually exclusively employed in these two areas of private security and manual labor.Footnote 55 In contrast, Ottoman Muslim and Jewish migrants were far more occupationally diverse.

What emerges by 1905, then, is a portrait of a neighborhood with several very different sides. For the native Jerusalemites and long-term residents, al-Wad was a tight-knit neighborhood of dense networks of families who resided there for generations,Footnote 56 with close ties of marriage and kinship within the neighborhood as well as to adjacent neighborhoods. At least one hundred Muslim households lived in the same building as one or more other family members heading up a different household, suggesting intergenerational residence in the neighborhood that is otherwise not visible. For example, notable ‘Afifi households occupied four of the six apartments at building number 61 in Suq al-Qattanin: the families of Muhammad Nafr al-Din Effendi, a policeman; Sheikh Rashid Effendi, a religion teacher; ‘Umar Effendi and his brother Muhammad, both government employees with large families and two servants; and Yusuf Effendi, profession unknown.Footnote 57 This extraordinary geographic proximity facilitated the regular exchange of resources and services, allowed for frequent supervision and advice, and blurred the boundaries of household, family, and kin. This also certainly relayed an intimate familiarity to the neighborhood and social life. At the same time, the presence of large numbers of new people and immigrants in the neighborhood, with different levels of connectivity and acculturation, was unmistakable.

MAPPING PEOPLE ON THE NEIGHBORHOOD SCALE

Because al-Wad had a uniquely high proportion of households (92 percent) with a recorded quarter/street/alley in 1905, we are able to map residents’ location within the neighborhood at a variety of scales, something that is not possible to this extent for the other Jerusalem neighborhoods. Plotting the Jerusalem census households on a georeferenced map of the neighborhood (figure 3) reveals that this ‘most mixed’ neighborhood was itself very unevenly mixed, with areas of extreme segregation, on the one hand, and areas of significant integration, on the other. In order to better understand this process, I will refer to several widely-accepted dimensions of segregation: evenness, or the distribution of social groups in the city; concentration, the amount of space taken up by a group; clustering, the contiguity of group members in the urban landscape; and exposure, the possibility of contact and interaction between different groups.Footnote 58

Figure 3. Distribution of al-Wad Households, 1905 Ottoman Census. (Map by Joe Aufmuth, Geospatial Consultant, University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries.)

Within al-Wad, high levels of spatial evenness characterized some millets, while spatial concentration was much more pronounced for others. Muslims and Ashkenazi Jews were the most diffuse millets: Muslims lived in all of the dozen streets/alleys listed in al-Wad, while Ashkenazi Jews lived in most of them and were spread fairly evenly throughout the quarter. Maghrebi Jews lived on about half of the neighborhood's streets but were most heavily concentrated (75 percent) on only three streets, ‘Aqabat Rasas, Hukumet, and al-Wad. This pattern is born out in the most common measure of evenness, the dissimilarity index; by this index, if we only consider the two largest groups, Muslims and Jews, al-Wad rates as fairly “even” (.325 on a 0-1 point scale), meaning that only around one-third of Muslims and Jews would have to relocate to be perfectly distributed in the city.

Christians were much less evenly distributed in the neighborhood, with almost 90 percent of Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Christian households concentrated in the northwestern quadrant (figure 4). Roman Catholics lived on only four streets total, and 83 percent lived in just six buildings on one of these streets. Greek Orthodox Christians were more spread out than were Catholics, but even so, most of them lived on those same four streets in the northwest quadrant of the neighborhood. It bears noting that this quadrant adjoined the heavily Christian neighborhoods of Bab al-‘Amud and Ḥarat al-Naṣara, where there were majority Christian populations and numerous Christian institutions, demarcating a fairly contiguous bloc of Catholic and Orthodox Christian life. The outlier from this pattern is the tiny Protestant population in the neighborhood, all of whom (eleven households) lived in the southeasternmost street in the neighborhood, in their own cluster. In terms of the dissimilarity index, almost two-thirds of al-Wad's Christians (.595 on this same scale) would have to be relocated to attain an ideal distribution in the city, twice the rate of Muslims and Jews. Note that these Christian clusters do not imply Christian isolation in the neighborhood, because these streets on which they were concentrated were overall very mixed, as we will see.

Figure 4. Christian Households in al-Wad Neighborhood, 1905 Ottoman Census. (Map by Joe Aufmuth, Geospatial Consultant, University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries.)

While Muslims were generally widely dispersed throughout the neighborhood, the five alleys east of Tariq al-Wad that led up to the interior gates of the Haram al-Sharif compound had a particularly heavy concentration of Muslim households. One street in particular, Bab al-Hadid, which was at the time the most populous Muslim street, was almost exclusively (>90 percent) Muslim, and another small alley, Ghawanme, had only Muslim households. However, these are rare examples of Muslim isolation at the street level.

In marked contrast to these areas of intense millet-based concentration, clustering, and isolation, most streets in the neighborhood had variable levels of millet heterogeneity, as shown in figure 5. The most mixed streets, where no single millet comprised more than 37–42 percent of the residents, consisted of the major north-south axes as well as two major west-east arteries. Overall, it is apparent that micro-location within the neighborhood mattered, echoing the importance in segregation studies of sensitivity to scale rather than simply focusing on arbitrary administrative boundaries.Footnote 59 Other critics have pointed out that segregation is best considered multiscalar—that is, as taking place simultaneously at multiple scales in the city.Footnote 60 Rather than being opposite ends of the spectrum, segregation and diversity are “enfolded.” In other words, the aggregate heterogeneity of al-Wad existed simultaneously with the street- and quadrant-level patterns of both segregated clusters and isolation, on the one hand, and integrated streets, on the other.

Figure 5. Street-Level Household by Millet, 1905 Ottoman Census. (Map by Joe Aufmuth, Geospatial Consultant, University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries.)

Before we turn to the important question of why there was such variable concentration and mixing in various parts of al-Wad, let us briefly think spatially about the two other major social attributes recorded in the census—profession and place of birth. For most residents of al-Wad, there was little direct correlation between occupation and neighborhood location. The one exception, however, is the high spatial concentration for people in the building industry, with almost half of al-Wad's building workers living on a single street. This correlates to the high concentration of Christians in this industry, where they were 60 percent of al-Wad residents employed in the building trades, triple their ratio in the neighborhood population. Overall, though, there also was no strict class segregation in the intramuros city: the same street could—and often did—house the elite, the working class, and the very poor. For example, on one side of the home of the neighborhood's most illustrious resident, Mufti of Jerusalem Muhammad Taher al-Husseini, lived two Christian master builders and their families, along with Habib al-Shami, a Greek Orthodox cobbler whose sons worked as a carpenter and an apprentice; on the other side, the mufti's neighbors were Muslims of more modest lineage and occupation: ‘Abd al-Burhan Fawakhiri, a post-horse driver, Hasan Dib, a sweets shop owner originally from Sidon, and Muhammad ‘Arif al-‘Arif, a greengrocer, and their families.Footnote 61 In immediate proximity to the mufti was also the courtyard rented by Israel Dov Frumkin, a Jewish immigrant from Russia who set up a printing press and published the long-running Hebrew-language newspaper, Ḥavatzelet.Footnote 62

When we turn to examine the spatial implications of place of birth, on the other hand, we find that there is a significant correlation between immigration and living on the most mixed streets. Overall, ‘Aqabat al-Raṣaṣ was the most immigrant-heavy street, with 73 percent of its household heads born outside of Jerusalem, followed closely by Ḥukumet (63 percent), Tariq al-Wad (62 percent), and Khan al-Zeit (51 percent). That these streets were among the most mixed and the locations of the most recent arrivals to Jerusalem raises questions about both the structural and economic contours of property rentals and the cultural and social attitudes that shaped residential sorting, which we will revisit below. In other words, native and long-term residents had different choices available to them, and possibly different preferences, than did newcomers to the city.

On this point, we also observe a clustering of sub-Saharan African immigrants living with or near each other; for example, in one building, Tariq al-Wad number 14, Sudanese and Nigerian Muslims comprised nine out of twelve households, fully half of all sub-Saharan African-headed households in the neighborhood.Footnote 63 At least two other African households were located nearby on the same street. Furthermore, while many of the remaining entries for guards and manual laborers are blank under “sub-neighborhood,” preventing us from mapping their locations, clusters of these households were registered consecutively in the census books, suggesting an extant social network that led them to visit the census office together. As a result, it appears that ethnic/racial origin had significant spatial implications for sub-Saharan Africans, concentrating half of them in a single building and clustering most of the others either spatially or socially in addition to professionally.

LEGAL, RELIGIOUS, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL, AND CULTURAL FACTORS EXPLORED

What factors explain these concurrent areas of marked heterogeneity and homogeneity in the same neighborhood? First, we must consider the structural limitations of the real estate market. Private property was, of course, bought and sold regularly in Jerusalem,Footnote 64 but most ordinary, non-elite Jerusalemites were chronic renters rather than property owners. The high level of rentership had to do with the fact that much of the city's intramuros real estate had the legal status of religious endowment—waqf khayri (philanthropic endowment) or waqf ahli (family trust)—which in theory could not be sold, given, inherited, mortgaged, or turned back into private property, but which was rented out for income for the waqf beneficiaries.Footnote 65

In al-Wad numerous properties were waqf endowments, ranging from prominent Islamic institutions in the neighborhood dating back hundreds of years to at least Mamluk times, to stores, businesses, and houses whose income was dedicated to the Ḥaram al-Sharif or other Islamic pious purpose. Such was the case of all of the stores and houses in the Suq al-Qaṭṭanin, and at least another forty-five houses, 164 stores, six storehouses, and a café within the neighborhood.Footnote 66 In addition, there were also a large number of family awqaf in the neighborhood, including at least four dozen houses and almost three dozen stores and other businesses.Footnote 67 Waqf properties were leased by Jerusalemites of all religious backgrounds as well as by foreigners, a pattern which in the eyes of one historian was “an ordinary occurrence … and a sign of the religious permeability of the economic geography in Islamic cities.”Footnote 68 Numerous sources, from legal to rabbinical to biographical, testify to the common occurrence of waqf property rental across religious lines in Jerusalem.Footnote 69

However, one important element of this rental equation that has been little examined in terms of its impact on the urban landscape is the role of perpetual lease usufruct (ḥikr) rights over waqf properties. In Jewish law, this institutionalized practice was called ḥazakah, and it gave a Jewish lease-holder (maḥazik; pl. maḥazikim) the rights to sublet a given property to whomever he chose; the subletters in turn paid all rents directly to him, which included a healthy commission for the maḥazik.Footnote 70 According to various rabbinical writings, the practice emerged in the sixteenth-century Ottoman world for a number of reasons, but primarily was inspired as a means to control rent increases in a period of large-scale immigration in the aftermath of the Iberian expulsions.Footnote 71 Additionally, the ḥazakah practice effectively limited the interaction with and financial exchange between Jews and non-Jews as well as gave Jews a say over potential renters/neighbors, both of which had the effect of creating and preserving Jewish communal enclaves.

In 1859, a series of violations of this custom led Sephardi and Ashkenazi rabbinical leaders in Jerusalem to jointly issue a proclamation forbidding individual Jews from turning to non-Jewish landlords on their own when there was a Jewish maḥazik in the neighboring courtyards. While much of the text of the proclamation was concerned with the financial burdens facing the Jewish communities due to rising rents in the city, it also underscores the role this legal institution played in establishing and reinforcing Jewish spatial boundaries.Footnote 72 In the absence of a comprehensive study of the Jerusalem ḥazakah market, we can gain a glimpse by surveying the Sephardi/Maghrebi results of the 1875 Montefiore census, which reveals that close to two-thirds (59 percent) of the 247 courtyards in which members resided were owned by a Muslim or Christian but had a Jewish ḥazakah contract in place.Footnote 73 In more than half of these, the maḥazik himself or his widow lived in the courtyard and rented out other apartments to tenants, underscoring the important supervisory and boundary-enforcing role they played since their tenants were also their most immediate neighbors. In contrast, only around 20 percent of the total courtyards in which Sephardi and Maghrebi Jews lived were reported as belonging to non-Jewish or indeterminate owners without a Jewish intermediary contract. By comparison, 15 percent of courtyards were privately owned by Jews, and another 5 percent were owned by Jewish institutions. Thus, there is substantial evidence that the ḥazakah institution played an important role in shaping Jerusalem's social topography in the late Ottoman period, even if it never succeeded in establishing a monopoly.

This dominance meant that some courtyards and some areas of the city were opened for Jewish clustering and concentration with rabbinical oversight. As a result, we see that many of al-Wad's Jews still lived in all-Jewish buildings in 1905, presumably rendered so by the maḥazik of that courtyard. The census records only twelve mixed Jewish-Muslim buildings in the entire neighborhood which housed forty-six Jewish and Muslim households, barely more than 6 percent of all al-Wad households; these inhabitants were almost all from the lower to middle strata, employed in the crafts, building trades, manual labor, or as minor religious officials.Footnote 74 Two of these mixed buildings were on ‘Aqabat al-Raṣaṣ: number 78 housed Maghrebi Jewish and Muslim households, including the grocer David Levi Maghrebi, Mustafa Effendi ‘Abd al-Nabi, a government clerk, and Ahmad Effendi al-Rimawi, a religious scholar from the village of Beit Rima, and their families; number 83 housed Ashkenazi Jewish and Muslim households, including the Pinsk-born cobbler Moshe Asher Goldberg, the Loshen-born Yekutiel Margolis, whose three sons worked in the building industry, and Ahmad Ruka, a coffee-maker, and their families.Footnote 75

In Jerusalem, buildings were commonly constructed so that rooms (apartments) surrounded a central courtyard (hosh); amenities like latrines, cisterns or wells, kitchens, and outdoor spaces were typically shared by all residents. Given the close quarters and religious dietary and other laws that regulated daily home life, it is perhaps not surprising that inter-religious mixing was rare at the building level. In fact, in the 1890s the Chief Rabbi Ya'kov Sha'ul Elyashar had ruled that renting space in a Jewish courtyard to non-Jews was permissible only in cases where it could not be avoided.Footnote 76 What is somewhat more surprising, though, is that the ḥazakah institution appeared to preserve ethnic lines almost as much as religious lines: in the aforementioned 1875 Montefiore census, not a single Ashkenazi tenant was listed in the Sephardi and Maghrebi courtyards, and by the 1905 Ottoman census, only thirteen buildings in al-Wad with thirty-four households were ethnically mixed between Maghrebi/Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews.Footnote 77 From this we can see that social networks and cultural preferences played a large role in residential patterns. In addition to praying and studying in different institutions, Maghrebi/Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews intermarried only infrequently at this time, and their separation into distinct courtyards easily followed this reality.Footnote 78

Beyond the Islamic waqf properties, Jewish and Christian religious endowments similarly served both communal charitable and family trust purposes. Between 1882 and 1904, over a dozen Jewish endowments (hekdesh) were established on properties within al-Wad, the majority by owners who lived in the neighborhood.Footnote 79 The endowments ranged from the modest (one to two room parts of a house) to sizable (a building with thirty-three rooms, four courtyards, two water wells, a kitchen, and an adjacent garden and storeroom). Most of these endowers were Ashkenazi Jews who dedicated the proceeds of the property after their deaths to their specific immigrant religious congregation (kollel) for religious education or ritual, or for upkeep of the poor of their community. These endowed properties thus served as a metaphorical brick rooting specific congregations and communities in the city.

The role of the Christian churches was even more transformative in the Jerusalem landscape. Both the Roman Catholic Custodian de Terra Sancta and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate were large landholders and owners of property in the city, some of which they rented or distributed for use of their co-religionists. Although neither patriarchate has released data on their property ownership, today church-owned properties are marked by a plaster engraved cross on the outside of the building; many of the buildings in the northwest quadrant in al-Wad display this mark. When we consider that almost every building in which Roman Catholics or Greek Orthodox Christians lived was entirely comprised of that denomination, it becomes clearer that church ownership likely determined Christian settlement patterns in al-Wad. In that neighborhood, there was only one case of Christians living in mixed housing, a building comprised of Catholic and Protestant households on the southeastern edge of the neighborhood.

Petitions to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate further support this understanding of Christian housing as deeply connected to denominational identity and religious boundaries. Property-less Orthodox Christians regularly turned to the church for housing allocation or, secondarily, rent subsidies, and saw it as a right of community membership. One petitioner wrote to the patriarchate in 1889 to ask that the housing council give her a place to live “like it is normally being offered to other Christians,”Footnote 80 while another echoed this demand that he be “treated equally, like the other Christians” and receive housing.Footnote 81 Migrants to Jerusalem and returning Jerusalemites also requested housing assistance,Footnote 82 and their petitions suggest that the native-born enjoyed priority over “foreigners.” One long-term resident complained about the lack of attention to her petition, despite the fact that many “foreigners, Greeks, and peasants” were regularly housed in community buildings, and another petitioner complained about being evicted despite his fifty years in the city and his three native-born wives.Footnote 83 Several petitioners referenced their registration in the Ottoman census books as a way to prove their long ties to the city, while others emphasized their native Jerusalemite spouse.Footnote 84

Indeed, housing was such a valuable commodity that it was not unheard of for individuals to convert to Orthodoxy in the hopes of receiving accommodation. The Roman Catholic couple Yusuf and Thekla Hanna, for example, requested conversion to Orthodoxy in 1885 so that they might receive “a small place to live.”Footnote 85 Orthodox petitioners also dangled the threat of joining another church or conversion to Islam in order to pressure church officials to give them housing. Eleni Halil Kaxbaxti, for example, implored the patriarchate to give them housing so as to prevent her husband from joining the Roman Catholic Church.Footnote 86

Overall, housing parishioners in church-owned property had the effect of creating and enforcing confessional boundaries on the building level. Jamila, the Greek Orthodox widow of a Roman Catholic, petitioned the patriarchate so she could move out of the Roman Catholic monastery she had lived in with her late husband in order to return to her own community.Footnote 87 Another petitioner complained when his neighbor rented out a spare room in her church-owned assigned house to a “foreigner,” and insisted that either she be forced to rent to an Orthodox Christian or that he be reassigned elsewhere.Footnote 88 Other petitioners complained about neighboring properties being rented to Protestants, either instrumentally voicing a concern that was expressing a real personal aversion to converts or likely to please the housing committee.

In addition to these intra-Christian boundaries, housing petitions also revealed preferences for strong inter-religious boundaries, or at least a hope that inter-religious complaints might draw the swift attention of the housing council. Several petitioners mentioned their dissatisfaction about living in the “Turkish” neighborhood or among “Turks” and requested that they instead be housed in church properties or in the Christian quarter.Footnote 89 For example, Jiryis and three other fellow petitioners wrote that they, their wives, and their children had daily conflicts with their Muslim neighbors.Footnote 90 The poor widow Anna went so far as to imply that her daughter's honor would be in danger if they were not moved to the monastery or a Christian house.Footnote 91 Other petitioners had practical or spiritual reasons for requesting assistance in moving or to Christian-dominant neighborhoods, such as seeking proximity to school or church, or longing for overall spiritual succor.Footnote 92 For poor and property-less Christians, then, housing was intimately connected to confessional identity, church and family networks; in contrast, for the fortunate more affluent Christians who owned their own housing, whether intramuros or in the new extramuros neighborhoods, housing was a source of economic autonomy and savvy investment.Footnote 93

In addition to the efforts of Jewish and Christian authorities to limit their parishioners’ housing choices and boundaries in the city, Ottoman interpretations of Islamic law also tried to prevent non-Muslims from building or residing in the area around mosques and to limit the establishment of non-Muslim religious or educational institutions in Muslim-dominant areas. To a certain extent this was successful—as mentioned earlier, two of the streets adjacent to the gates leading to the Ḥaram al-Sharif were exclusively Muslim streets. Memoirs also state that these streets were patrolled, and non-Muslims were excluded from them de facto. Paradoxically, however, the Ottoman census reveals growing Jewish presence in the three other streets adjacent to the Haram al-Sharif.

The most significant in this regard is the southeasternmost street segment, the area known as Mahkama, half of whose households came from the three Jewish millets, one-third of whom were Muslim, and the remainder primarily Protestant. This street segment leads immediately to the Maghariba quarter, the location of the Wailing Wall, considered the last remaining part of the Second Temple and therefore the holiest site in Judaism. Proximity to the wall was highly esteemed among pious Jews, and as a result, historically it was the residence of prominent Sephardi Jewish families such as that of Chaim Moshe Elyashar, a member of the administrative council (majlis idara) and the Jewish spiritual council (majlis ruhani) as well as the son of the late Chief Rabbi, Ya'akov Sha'ul Elyashar. Similarly, we see that Ashkenazi Jews moved onto the streets leading up to the Ḥaram al-Sharif, in particular ‘Ala’ al-Din/Bab al-Nazir Street, where they comprised twelve out of twenty-one households. The Jewish clustering in four buildings on the west end of the street likely began as a single ḥazakah secured to coincide with the founding of an Ashkenazi yeshiva, Torat Ḥaim, nearby in 1886, which certainly would have had the effect of making the area a magnet for Ashkenazi Jewish work, study, worship, and settlement.

In addition to these legal and religious factors that seemed to work against and for mixing on the building and street levels, we should also consider the question of street morphology, economics, and sociocultural values. Al-Wad's population density was among the highest in the intramuros city, second only to the neighborhood to its south, al-Silsila.Footnote 94 As a result, from the 1890s on, residents of means were choosing to leave the crowded city for the new expanses outside the city wall.Footnote 95 This process of affluent flight from the intramuros city was only in its first generation at the time of the 1905 census, but it would accelerate considerably in subsequent decades. Moreover, the two main north-south axes, Tariq al-Wad and Khan al-Zeit, were highly trafficked main thoroughfares with constant wagon, cart, and pedestrian traffic and a high presence of commercial spaces and activities;Footnote 96 in contrast, al-Wad's narrower arteries and alleys provided a less public, more private, more protected environment for residents. We already have seen that both of those main streets had a high ratio of newcomers, suggesting their relatively high turnover in residential real estate, whether due to affordability or to undesirability for longtime residents, or both. The latter explanation is supported by the fact that relatively few of the neighborhood's elites (charted by honorific titles such as “Bey” or “Effendi”) lived on either street—only 11 percent and 13 percent, respectively—and most were located on the smaller, more “private” streets, such as Bab al-Hadid, for example, where 55 percent of its heads of household boasted an honorific title.

Although it is difficult to reconstruct social attitudes in general, at least some sources from the time period have suggested a strong preference for living among one's coreligionists, such as the Greek Orthodox petitioners we encountered earlier who sought housing reassignment to leave the “Turkish neighborhood” and Protestant neighbors. In another example, in an article in the Hebrew press about the tribulations of the Jewish residents of a new extramuros neighborhood who were harassed by a Christian anti-Semite, the author ended by praising the wisdom and security of “Israel living alone.”Footnote 97 To be sure, these are isolated examples and cannot represent the whole of social attitudes, and they also are self-serving sources where millet had an obvious political and economic power or cultural and religious values to uphold.

In contrast, numerous memoir sources recount the multiple ways that individuals were embedded into their neighborhoods and among their neighbors—ritual visits and food exchanges were conducted with new residents, neighbors played a socially expected role in family celebrations, mourning, and daily socializing, and the security of shops and homes as well as family honor were left in the hands and under the watchful eye of one's neighbors. Neighbors also quarreled, gossiped, and sued each other.Footnote 98 Residential mixing on the ground led to or correlated with other social ties across religious lines—friendship, economic partnership, milk brotherhood, and even including illicit sexual liaisons and intermarriage. For example, the memoirs of Musa al-‘Alami recount the ritual social ties his elite Muslim family developed with the family of his “milk brother,” the son of a Jewish greengrocer who was born at the same time in al-Wad—each was nursed by the other's mother.Footnote 99 Likewise, the memoirs of the musician Wasif Jawhariyya, whose family owned their home in the al-Sa'adiya neighborhood and rented out apartments to their coreligionists, are devoid of confessional boundaries, whether social or spatial: his neighbors included fellow Christians and Muslims who celebrated, protected, and supported each other.Footnote 100

While we need not uncritically accept all nostalgic memories of a pre-nationalist utopia, we can use them to think about the importance of space in facilitating certain social interactions and ties. In his “memory walk” through his childhood neighborhood of al-Wad, for instance, Gad Frumkin illustrated the importance of physical proximity and everyday encounters for the lived experience of his neighborhood and for his identity as rooted among his neighbors.Footnote 101 This example reinforces the sociologist Rick Grannis's observation of the importance of pedestrian circulation routes for “neighboring” ties and activities.Footnote 102 In this regard, briefly returning to the sociological indices might offer a helpful counterpoint for these anecdotal narratives.

One of the important indices in measuring segregation and its effects is called an interaction or exposure index, which is essentially a numerical value given to the likelihood of encountering a member of a different group on the streets of the city. The exposure index for al-Wad between Muslims and Jews and Muslims and Christians is similar, 0.29, meaning that there is a better than 1 in 3 chance they will encounter each other in the street. This makes sense given the diffusion of Muslims and Jews throughout most parts of the neighborhood, in the first case, and because Christian clustering in the northwest quadrant of the neighborhood was still along streets with Muslim residents, rather than in isolated areas, in the second. In contrast, the exposure index for Christians and Jews in al-Wad was significantly lower, 0.12, meaning they had only a one in ten chance of encountering each other on the street. This can be explained by the different geographies of their concentrations in the neighborhood: virtually no Christians lived on the streets where most Jews lived. These numbers also happen to echo the memoir literature that recalled closer relations and contact between Muslims and Jews, but tense or absent relations between Jews and Christians, the latter no doubt due to high theological and social tensions in addition to this spatial distance in many quarters.Footnote 103

At the same time, exposure simply cannot be reduced to a number, since every single street in al-Wad intersected one of the main mixed streets. Because of its centrality and diversity, al-Wad residents could not stray far from their homes and streets without literally bumping into neighbors of a different religion, ethnicity, place of origin, or social class, not to mention the steady stream of other Jerusalemites attending to their business, administrative, or commercial needs in the neighborhood. In this regard, the major arteries of the neighborhood with high expectations of encounter might be considered “cosmopolitan canopies,” as described by the sociologist Elijah Anderson, that is to say, pluralistic spaces of urban civility where ethnic, racial or religious borders might be deemphasized and a certain “social neutrality” is achieved.Footnote 104 Indeed, the “mixed” neighborhood of al-Wad seems to have been an ideal site for settling people on the margins of religious groups. Intriguingly, the 1883 census notebook additions over the twenty years before the 1905 census document that of the thirty-one Muslim households who registered their move into al-Wad with the government authorities, fully half were headed by converts to Islam. These religious marginals could be settled in a neighborhood that was “in between” without being conspicuous or vulnerable, or perceived as having a deleterious effect on the neighborhood, unlike in places that were more homogeneous or had a more fragile religious identity.

CONCLUSION

As the authors of an interdisciplinary survey of the spatial turn put it, “geography matters, not for the simplistic and overly used reason that everything happens in space, but because where things happen is critical to knowing how and why they happen.”Footnote 105 To that I would add, and with whom they happen. In other words, the mere fact of physical location created and sustained networks of positive and negative relations, contacts, and everyday interactions, many if not most of which are otherwise absent from the historical archive. Understanding where people lived and why, as well as who their neighbors were, is thus a necessary precondition for understanding intercommunal urban relations. Mapping census data using GIS allows us to shift the scale from the aggregate to the micro, to move between and within census neighborhoods to identify both localized and transcending patterns such as concentration and clustering. Incorporating additional legal, memoir, and other sources also can allow us to better understand this multidimensional process as well as to map change over time, which is critical to understanding whether or not the kinds of patterns of integration and segregation discussed in al-Wad were transitory in the life of the city or in the lifetime of its residents.

What becomes apparent is that while confessional boundaries were more porous than impermeable, they were far from completely absent in the late Ottoman city. In the years surrounding World War I the rise of ethnic nationalism and European colonialism would have devastating consequences across many Mediterranean cities—Istanbul, Salonica, Izmir, Van, Alexandretta, and Jerusalem—which convulsed with urban violence that bore some component of religious and/or ethnonational conflict. The genealogy of this violence, in my mind, is incomplete without closer analysis of the structural contours of Ottoman urban heterogeneity. The case of Jerusalem shows that residential patterns restricted or enlarged zones of contact between different religious and ethnic groups, but these zones were never divorced from the broader economic, legal, political, and social transformations surrounding them.