Since Max Weber's classic work Economy and Society (Reference Weber1978), sociologists and other social scientists have shared the insight that rational-legal authority is one of the definitive features of modern state power. Defined as the power to set, enforce, and govern populations on the basis of codified legal rules over a territorially defined society, legal authority is a unique feature of the rise of the modern state. Following Weber's footprints, historical sociologists are increasingly recognizing the significance of law in the emergence of modern political and economic systems, including the rise of mass democratic regimes and capitalist forms of production (Somers Reference Somers1993; Steinberg Reference Steinberg2003). Yet some states have failed to gain a monopoly over the administration of law, and been unable to displace alternative norms, institutions, and mechanisms of social regulation that gain hold among significant portions of their population, and we must ask why.

Establishing a monopoly over legal authority seems most problematic for newly centralizing states that are expanding their authority to incorporate “stateless” rural regions with traditions of communal autonomy, tribal organization, and customary law. The classic literature on modern state formation has long recognized that national authorities have often faced rural populations that are reluctant or refuse to cooperate with them (Scott Reference Scott1976; Tilly Reference Tilly1978; Weber Reference Weber1976). Such communities remain significant to understanding the development of states and legal authority in the non-Western world. In northwestern Europe such communities were common until the early modern period, when they were defeated by the church, feudal lords, towns, states, and other powerful, translocal organizations (Berman Reference Berman1983; Lachmann Reference Lachmann2000; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1988). In the Balkans, however, such communities survived well into the twentieth century owing to the decentralized nature of Ottoman rule and the persistence of pastoral and subsistence-based rural economies (Stoianovich Reference Stoianovich1980). In this paper, I use the historical case of state building in the Albanian highlands to develop a theoretical framework to explain the conditions under which modern states succeed, and fail, to establish national legal authority in remote regions.

The case of the Albanian national state's early attempts to establish authority in the highlands illustrates problems faced by modern states when making claims to legal authority in such regions. In the 1920s, the state made earnest attempts to impose political and legal authority in the highlands. After successfully confronting and defeating local resistance, national authorities were able to establish permanent administrative offices and routine taxation, and a fairly effective gendarmerie force. However, this apparent success is accompanied by a puzzling paradox: over time, while the state's capacities of exercising coercion increased, the ability of its agents to enforce a state-based legal order declined. What explains this development?

Based on original archival research, this paper argues that the state's failure to maintain its legal order in the highlands was the direct consequence of its early institutionalization of juridical authority in the region. My historical narrative contrasts two periods of state building. During the first, the state engaged in a creative elaboration of new institutional forms that allowed for the rise of shared legal jurisdiction between state and local institutions. In the second period, the state abandoned its flexible approach and moved to consolidate a unitary national legal order enforced by its expanding organizational infrastructure. Rather than leading to greater state control, the move provoked social conflict between national and local highlands institutions, manifested in a deterioration of local authorities' ability to effectively govern.

I will critique, and also build upon, two distinct but related sets of theoretical literatures on state building. Influential “state-centric” accounts stress the import of a state's organizational capacities for coercion and resource extraction as determinants of successful state building. “Neo-institutionalist” approaches argue instead that the construction of state institutions in the global periphery has to do less with local dynamics of contention than with “decoupling” that results from implementing global models. I will argue that while both sets of theories provide important insights, they ignore the degree to which locally driven cultural claims to legitimacy can structure the processes and outcomes of building legitimate legal orders in emerging peripheries. I draw upon and extend Abbott's (Reference Abbott1988) work on professional claims of jurisdiction to develop a theoretical framework that combines cultural and organizational approaches to explain the structure of state-society conflicts during the formation of centralized, state-administered legal orders.

THEORIES OF STATE BUILDING IN AGRARIAN SOCIETIES

State building is commonly defined as the process by which a political authority establishes differentiated, centrally controlled, bureaucratically organized structures claiming to exercise sovereign control, and accumulates a monopoly of regulatory and coercive power within a distinctly defined territory (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz and Steinmetz1999; Tilly Reference Tilly1992). In other words, it is the process through which institutional mechanisms for the expansion and exercise of state power emerge. We can define state power as the capacity of state organizations to engage in rationalized administrative and coercive practices without facing continual, organized, and active opposition from individuals, organizations, or social groups within their territory. State building also implies a process of differentiation between the state organization and its attendant roles and other social organizations, in that the state claims primary legal authority and regulatory power. As I have said, two macro-level models of state building—state-centric and neo-institutionalist—vie to explain the causal dynamics of this process.Footnote 1 I will outline the defining features of each and the problems each faces in explaining cases of non-Western state building.Footnote 2

State-centric models see state building as a product of political conflict, whether protracted or episodic, involving a central ruler and local elites (Barkey Reference Barkey1994; Brustein and Levi Reference Brustein and Levi1987; Levi Reference Levi1981; Mann Reference Mann1984; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979; Reference Skocpol, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985; Tilly Reference Tilly1978; Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985; Reference Tilly1992).Footnote 3 In this tradition, state building is primarily a political struggle over the exercise and expansion of political power by a ruling authority over rivals. The state is represented by either an individual ruler or a specific set of coercive and administrative organizations. It is often treated as a unitary, autonomous actor, with its power based on its exclusive control (aspired to or actual) of the means of coercion. This permits the state to successfully compete with and ultimately triumph over rival social groups vying for political control. In northwestern Europe, the historical subordination to a political center of local authorities such as feudal lords, ecclesiastical authorities, urban councils, and other communal organizations signaled the successful rise of what Braudel called the “territorial state” (Reference Braudel1972). The capacity to mobilize and apply force stands as the key determinant of this outcome. As Tilly wrote in an influential article, “The personnel of states purveyed violence on a larger scale, more effectively, more efficiently, with wider assent from their subject populations, and with readier collaboration from neighboring authorities than did the personnel of other organizations” (Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985: 173). In other words, it is ultimately the state's social organization of the means of physical violence, and its mobilization of it, that best explains the success of state building.

NEO-INSTITUTIONALISM AND THE STATE

While the classic “state-centric” theoretical tradition emphasizes the agrarian origins of modern states, for neo-institutionalist theorists the global diffusion of modern, hierarchical, state-like organizations was generated by the distinctly modern features of professional, bureaucratic organization. However, sociological neo-institutionalist theory has mostly treated the state as a residual category, or an environmental fact that provides the framework for the actions of other, non-state organizations.Footnote 4 The tendency to treat the state as a background actor that structures the behavior of other organizations has persisted despite the common recognition that the state itself is none other than an organization or cluster of organizations (Laumann and Knoke Reference Laumann and Knoke1987; Skocpol Reference Skocpol, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985). To be sure, sociological neo-institutionalism acknowledges that the state “is not simply another actor in the environment of an organization,” but “a quite distinctive type of actor” (Scott Reference Scott2008: 98). Scott identifies the distinctiveness of the state mainly in terms of its ability to use coercion to “[exercise] authority over other organizations” (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1977: 21, cited in ibid.). That said, the historical institutionalization of state power remains a theoretical “black box” in neo-institutionalist theory.Footnote 5 This is evident even in more recent efforts to theorize the emergence of the national state by sociologists working in the neo-institutionalist tradition. For the most part, this theorization, branded as the “world society” model, argues that membership in the international state system is sufficient to create mechanisms for the diffusion of organizational models, and generates pressures for state actors to conform to global processes of institutional and normative homogenization (Meyer Reference Meyer and Steinmetz1999; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997).

In this vein, the world society perspective argues that the national state, rather than being simply an organization defined strictly by local processes and policies, is also (and perhaps more importantly) an isomorphic world model, in the meaning of the term articulated in a seminal article by DiMaggio and Powell (Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). In contrast to alternative approaches, the world society perspective gives ontological and causal priority to the global cultural system that establishes the normative, cognitive, and organizational frameworks within which state organizations and their policies are constructed (Meyer, Boli, and Thomas Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas, Scott and Meyer1994). Its practitioners argue that norms, professional and associational groups, policy models, and legitimation schemas operating at a transnational level are powerful causal mechanisms in the isomorphic diffusion of the modern national state model, in terms of both formal institutional structures and substantive policy orientations and organizational means (Meyer Reference Meyer and Steinmetz1999; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997). The increasing similarities found in modern forms of state organization and in the formal and substantive contents of policies and political ideologies lend credence to this claim. But one encounters an analytical problem in the model's inattention to significant differences in state capacity, or in what Mann (Reference Mann1984) has more precisely dubbed the state's “infrastructural power.”Footnote 6 It is clear that if neo-institutionalist theory is to offer a viable alternative model to the state as an institutional reality then it must contend with problem of variation, rather than only isomorphism and diffusion, in the structures of state institutions, state policies, and policy-making and policy-implementing capacities. This problem has been central to the field of state theory.

Decoupling and Its Explanatory Insufficiency

The world society model addresses the issue of state capacities in a partial manner through its emphasis on decoupling. Decoupling is the contradiction that arises between the official goals, norms, and sanctioned practices of organizations and the actual practices of agents striving to enact and maintain them (Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977). In this view, it is expected that a gap will emerge between the formal goals and rules of state organizations and the practices of their members in implementing them. Every complex organization based on institutionalized norms must adapt to environmental contingencies and become embedded in local processes. Therefore, every formal organizational order must continuously negotiate between its formal rules, goals, and legitimizing ideologies and the localized, embedded practices of social actors. The challenge for state builders is to ensure that the particular state's organizational structures and practices mimic the standardized organizational schemas of world society: “Decoupling is endemic because nation-states are modeled on an external culture that cannot simply be imported wholesale as a fully functioning system” (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997: 154). From this perspective, national states in the global periphery, which presumably borrow external organizational forms most heavily, are most likely to experience decoupling. This occurs as local social structures cope with and adapt to the pressures of internationalizing world norms. These local structures must negotiate the construction of modular organizational forms and practices that use universalized rationalities and legitimacy schemas, expressed via catchwords such as “progress,” “development,” “modernization,” and “the rule of law.”

A problem of the concept of decoupling is that it remains too broadly and descriptively defined to provide any causal account of the processes of institutional structuration that lead to variation in state institutions and their capabilities. A perfectly isomorphic model would predict either that all states will become weak (because of endemic decoupling processes), or that all will become strong (because state organizations are isomorphic). That this is not the case suggests that processes other than decoupling must account for the divergence between a given state's institutional claims of power and its actual ability to shape the behaviors and beliefs of the population it claims to rule. In the case of legal authority, these behaviors and beliefs must be shaped in fundamental ways. This is because legal authority is not merely coercive but must at some level correspond to generalized social beliefs about the legitimacy of the regulation and administration of social life by the plethora of interconnected, third-party organizations that we typically designate under the umbrella term “state”: the police, an independent court system, educational and penal institutions, and so forth.

The challenge faced by states builders does not necessarily lie in legitimizing the idea of the state institution, but rather its organizational practices among the ruled. For legal authority this involves transforming existing conceptions of right, law, and justice and replacing them with those premised upon the institutional monopolization of the legal order by the state. This must begin with the definition of the state as the single social institution vested with the power to define, articulate, enact, and enforce a single body of legal precepts that are, in theory, universally applicable. The question for institutionalist theorists, then, is not only one of the mechanisms of diffusion; it is also about the mechanisms through which new forms of authority, and new understandings of social order, are implanted while existing ones are marginalized, stigmatized, or repressed. Anthropologists have documented the great diversity of social institutions among human societies, particularly those related to the organization of law (Geertz Reference Geertz1983; Malinowski Reference Malinowski1926; Watson Reference Watson1974). The world society model's emphasis on isomorphic processes of state development neglects the complex interplay and contradictions that emerge between state-based and socially and culturally embedded forms of legal norms and social regulatory claims. It downplays or ignores the deeply contentious processes involved in the establishment of modern state authority.

To summarize, state-centric approaches emphasize the role of political power premised upon the capacity of sustained and durable coercion as a key factor in the construction of modern state power. This model is theoretically efficient, but fails to explain how states are able to build effective coercive organizations in the first place. The world society model points to the global diffusion of cultural models as a key process in the making of modern states. For these theorists, organizations are the result of cultural scripts of the modern nation-state, originally formulated in the West and implemented by national elites worldwide. While these are both crucial and necessary conditions for the making of modern state authority, they are neither by themselves nor in combination sufficient conditions for the emergence of durable state power.

The Albanian state failed to gain durable institutional authority in its highlands region despite reasonably fulfilling the condition specified by state-centric theories: the accumulation of sufficient infrastructural capacities to exercise force. Moreover, a key reason for this failure was that state elites broke from a path of an endogenously driven institutional formation and tried to implement what they described as a “Western” model of legal governance. This presents a problem for both of the aforementioned theoretical approaches in that neither considers the intersection between the rise of modern state power and cultures of legality. Organized coercive capacities are certainly a necessary condition for the rise of the modern state, but are by themselves insufficient because organized political power alone does not determine the efficiency of modern political governance (Loveman Reference Loveman2005; Parsons Reference Parsons and Parsons1967). Global cultural scripts may explain why state elites choose to implement particular institutional models, but when those models prove ineffective in local contexts, then theorists who forefront them can only resort to the inadequate explanation of “decoupling.”

I argue here that attempts at state building that involve rapid expansions of bureaucratic authority over society are prone to “jurisdictional struggles” (Abbott Reference Abbott1988) between competing political authorities. These struggles more often than not involve intense cultural contestations of the legitimacy of state authority and of the actors who attempt to wield it. As Bourdieu argued (Reference Bourdieu1991; Reference Bourdieu and Steinmetz1999; Reference Bourdieu2004), states struggle to accumulate cultural forms of “symbolic power” as much as they strive to concentrate coercive capacities. Modern bureaucratic states typically have the upper hand in such struggles. Yet attempts to substitute malleable, “pre-national” arrangements with stable, centrally controlled organizations can provoke marginal social groups to evade “political capture” (Scott Reference Scott2009) simply by refusing to comply with state-sanctioned norms of social behavior. Under such conditions, state-building efforts end up weakening rather than strengthening the state's governing capacities. The Albanian case I present here will illustrate this.

ESTABLISHING AND EXPANDING STATE AUTHORITY IN HIGHLAND ALBANIA, 1919–1939

Here I will draw upon archival documents to historically reconstruct two key episodes of state building in highland Albania.Footnote 7 For convenience, I label these the “pre-code” and “post-code” eras—the periods before and after the Albanian state's adoption of modern penal and civil codes between 1927 and 1929.Footnote 8 These designate not only periods of legislative change but also two distinct modes of governance in the region. Briefly, in the pre-code era, the freedom of local authorities to negotiate local compacts with communal institutions produced a system that effectively divided legal jurisdiction between national institutions and highland communal ones. The costs of this arrangement were concessions to demands for local self-government and acceptance of limitations on the exercise of juridical regulation by central authorities. In the post-code era, central authorities abandoned their tolerance for local legal diversity and sought to establish a legally homogenous society throughout the state's territory. However, this policy led to deterioration in the state's ability to govern the highlands, with a concomitant rise in social disorder there.

Communal Institutions in the Service of State Building: Honor and State Building in the Pre-Code Period

Soon after the defeat of the Ottoman military in the Balkan wars of 1912–1913, the new state of Albania was recognized by Western powers at the London Conference of Ambassadors in 1913 with the territorial reconstitution of four former Ottoman provinces. Around 70 percent of the new state's territory was mountainous terrain, most of it in the northern and northeastern parts of the country. In the early twentieth century these highland regions were estimated to be home to about a quarter of the country's people. They constitute Albania's greatest concentration of mountain village settlements. The rest of the populace lived in the more arable lowland hills, coastal plains, and urban centers of central and southern Albania.

Albania established its first sovereign national government in 1919, after World War I ended. As foreign combatants of the war—mainly Austrians, French, Greeks, and Serbians—withdrew, territorial control became a key imperative, and national authorities established a system of centralized territorial governance based on the French post-Napoleonic prefectural system. The government successfully established territorial jurisdiction throughout most of the country, but the highlands became a problematic region due to the intransigence of local peasants and the refusal of rural communities to relinquish their autonomy. A series of 1919 reports from the northern prefecture of Shkodër, which included part of the highland region, illustrate challenges the prefecture faced in extending its authority into the highlands surrounding the town. They point to difficulties in convincing communities to accept government rule, sign up gendarmes, and pay taxes.Footnote 9 This warned of the sort of resistance the state would face in trying to establish its authority in the region.

Over the years that followed, the state's intrusion into the highlands provoked a number of rural rebellions; the historical record indicates armed uprisings by highlanders in 1921, 1922, 1924, and 1926. These were more than minor local disturbances—each posed severe threats to state control in the region as well as nationally. The 1921 rebellion in the Mirdita region became a full-fledged secessionist movement to establish an independent highland peasant “republic” (Skendi Reference Skendi1954). In this case and others, rural rebels failed to repel the state and the national government reestablished military control. Nonetheless, military dominance proved inadequate to imposing permanent administrative control. In this context, how state builders developed local networks to assert cultural claims of national authority proved critical to their eventual success in consolidating political control.

State Building and Peasant Honor Society

The Albanian highlands of the early twentieth century were characterized by a local system of communal organization based on an indigenous tradition of customary law, known locally as the ligj or kanun (words for law in Albanian and Turkish, respectively). The specific norms and practices of customary law were locally embedded and varied across distinct microregions, but several basic institutional features were shared across the population. These included norms that regulated aspects of domestic and family life within the household such as paternal authority and the division of labor, and communal affairs such as property relations, use of commons, and defense against outside threats. In this sense, the communal system of the Albanian highlands represented a specific form of rural political, economic, and territorial organization (Doçi Reference Doçi1996). These were mainly pastoral communities that secured a meager but steady existence through household production and commerce with local towns. They followed the peasant zadruga organization typical of the Balkan peasantry (Lampe and Jackson Reference Lampe and Jackson1982; Mile Reference Mile1984; Stoianovich Reference Stoianovich1980). While extended family production became less common in the Balkans over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this form of peasant economic organization persisted in Albania and especially in the highlands. The 1923 census found highlands households to have upward of thirty extended family members.

The household (shpi) was represented by the elder patriarch and identified by the name of a real or mythical ancestor, and was the key political and social unit (Doçi Reference Doçi1996; Hasluck Reference Hasluck1954). Customary law functioned as a public system of norms and rules that regulated relations between households and their members (Gjeçov Reference Gjeçov1989; Illia Reference Illia1993). Intra-household disputes were typically handled by councils of elders (pleqësi) made up of respected men of the community noted for their wisdom and knowledge of customary law. More general communal affairs were deliberated in assemblies (kuvend) in which usually all households of a village or village alliance were represented.

The exception to the collective mediation and management of affairs under customary institutions was homicide cases, especially those resulting from interpersonal conflict. In such cases restitution was gained through blood vengeance. The victim's male kin exercised executive power directly against the perpetrator or a male member of his kin group. Here legal restitution was based on a self-help principle in which aggrieved parties were responsible for securing their own retribution through vengeance, although within a regulated framework of norms and procedures of proper blood taking (Whitaker Reference Whitaker and Lewis1968: 265–74).Footnote 10 Outside observers often saw blood feuding to be the main cause of highlands interpersonal violence, since a feud did not always end with the taking of the original perpetrator's life but could persist if his kin avenged his death. This gave feuds a cyclical nature that often carried over from one generation to the next (Durham Reference Durham1909; Reference Durham1928).

Blood feuds and the social standing of clans were intricately embedded in a system of honor. Honor-based societies, found in many parts of the world, are historically characteristic of Mediterranean mountain societies, where honor serves as a highly effective status principle and medium of social transactions (Peristiany Reference Peristiany1966; Schneider Reference Schneider1971). Studies of social relations in honor-based societies have found that strategies to optimally ensure the accumulation and conservation of honor structure the entire “game” of peasant interactions and social relations (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977; Miller Reference Miller1990). Similarly, Albanian highland customary law was organized as a cultural order in which all forms of injury were treated as violations of honor, and its restoration was the primary purpose of restitutive actions, including revenge killings. Vengeance was dictated by the loss of “blood”—loss of a male member of the group—and taking vengeance, or threatening to do so, was a fundamental social obligation. Failure to do so could cost the group its honor in the eyes of the wider community (Gellçi Reference Gellçi2005).

Honor was a general property ascribed to family (household) and extended kinship groups, but was more fundamentally a personal characteristic of men. A man's honor was on the line when he made a pledge, offered protection to a guest, or received injury from another, especially when that injury occurred in the view of third parties.Footnote 11 Honor and its symbolism organized all-important aspects of social relations. It provided an interpretive frame that gave normative meaning to transactions, and was a mark of social status and privilege, and a source of personal dignity and self-worth. Among Albanian highland men, honor was also constitutive of gender relations and identities since women were not considered legitimate bearers of honor, but rather were the objects of male honor (Shryock Reference Shryock1988).Footnote 12

Frequent rebellions and peasant intransigence made state building in the highlands especially difficult. In Ottoman times the region enjoyed a high degree of political autonomy from imperial authorities, either by political design or, more likely, by sheer omission and disinterest. Ottoman authorities were based in urban centers and ruled the highlands mostly through intermediaries (Mile Reference Mile1984).Footnote 13 Albanian highland peasants also provided the Ottoman state with a pool of irregular military recruits, though evidently—at least during the late nineteenth century—an unreliable one (Erdem Reference Erdem, Anastasopoulos and Kolovos2007). For the most part, Ottoman elites saw the highlands as an unruly and ungovernable region best left to its own devices (Blumi Reference Blumi2003; Gawrych Reference Gawrych2006).

During the final struggle for Albanian national independence in the early twentieth century, the highland peasantry had largely accepted the premises of the Albanian nationalism promoted by urban elites and the notion of a distinct Albanian ethnic nation. The most imposing challenge to state builders after 1919 was not so much to convince peasants of the existence of the ethnic nation as an abstract “imagined community” (Anderson Reference Anderson1991), but rather to instill in them the idea of the state as an authority with the right to administer local society.Footnote 14

The solution state builders found was to turn to a local institution, the honor-based pledge called a besa, as a means of establishing the national state's political authority. The besa was a central institution in the clan-based, honor-centered rural highlands society.Footnote 15 A besa pledge could engage diverse parties, ranging from individuals to clans to entire regions, into temporary, limited pacts upheld by pledges of honor. While the besa's primary function was to create temporary truces between feuding parties, such as when going to war together against rival clans, its invocation also extended into other occasions that required establishing trust between parties. Thus, the besa could be given as a personal pledge of loyalty or faith in affirming an agreement between parties during a transaction or joint enterprise, or in resolving a dispute. It could also form the basis of alliances between adversarial groups in extraordinary situations, or in negotiating pacts between communities and external third parties. In addition to its institutional function, the besa played a central symbolic function in highland peasant culture—the violation of a besa was considered among the most treacherous of acts, and the surest road to dishonor for an individual and his clan (Durham Reference Durham1909; Gjeçov Reference Gjeçov1989; Hasluck Reference Hasluck1954).

In the early months of establishing state authority in the highlands, this element of local culture offered itself as the most effective resource through which to mobilize highland communities, demand loyalty to the government, and compel peasants to submit to the new administrative claims of local prefectures being established in the region. The besa institution was used in two ways. The first was its actual ritual performance, in which local officials such as military officers, prefects, and their subordinates invited communities to make solemn pledges of allegiance to the government, to give their besa word of honor to obey its officials and laws. One such compact is appended below.

Second, and more significantly, during the early period of state building the government compromised its goal of creating an administratively and legally homogenous society by establishing special committees that combined, and therefore divided, jurisdictional authorities between central and rural communal institutions. The framework was provided by a 1921 government order that established a distinct set of institutions in charge of governance and the maintenance of public order in the highlands. A crucial institution within the system was “the besa committee,” a body that mediated between the prefecture and local society. In its formal structure, the besa committee was headed by a subprefect appointed by the local prefect (who was accountable to the national Ministry of the Interior), and included “representatives” of highland communities from the subprefecture. The duty of the committees was to administer the besa between local communities and the national government. While they were given authority to decide local matters, their two main functions were to mediate between the state's administrative claims and local society and to ensure the maintenance of public order on behalf of the prefecture and other national authorities.

This policy of creating besa committees to fuse state control with communal authority followed from a 1920 government regulation that stipulated a distinct legal regime for the highlands based on customary law. It effectively excluded the highlands from the civil and penal authorities that would be applied in the rest of Albania. According to this regulation, “When delinquent acts take place in subprefectures and regions, such as banditry or murder within the boundaries of the subprefecture or region, as acts against the existing besa, the committees formed by the besa are obliged to act together with government forces to capture the responsible individuals.… The subprefecture committees will penalize those found guilty of delinquent acts in accordance with local custom and the [region's] customary law” (in Elezi Reference Elezi1997: 35).

These early arrangements were reinforced in the aftermath of highlander rebellions and during times of political unrest. For example, in 1924, when Albania underwent a revolutionary change in government the new government renewed besas with highland communities, claiming their loyalty to the state and the new regime. When the revolutionary government itself fell, the new one under the conservative President Ahmet Zogu instituted a new set of besas with highland communities. In 1926, under Zogu's patronage, the government organized a ceremonial event in which notables from the highlands were summoned to the national capital and required to pledge their besa to the state and to Zogu as its supreme leader. In exchange, the government recognized the exclusive jurisdiction of communal institutions and customary law in the highlands. While these measures required constant renewal and negotiation with local communities, they largely consolidated national political (if not administrative and legal) control in the highlands. By the late 1920s, rebellious movements there had largely subsided and the national government's presence, in the form of military and gendarmerie posts and subprefectural offices, extended into even the most remote and intransigent regions.

Legal Modernization in the Post-Code Period and the Rise of Social Disorder

After the establishment of President Zogu's authoritarian regime in 1925 (he became King Zog after 1928 constitutional changes), Albania experienced a period of relative political stability that was used to channel energies toward legal and administrative reforms (Anastasi Reference Anastasi1998; Fischer Reference Fischer1984; Tomes Reference Tomes2004). An important marker of this new period was the Albanian parliament's passage of new penal and civil codes during 1927–1929, modeled upon similar Western codes. Their adoption was seen as not only an effort at legal reform but also a more fundamental civilizational drive to eradicate vestiges of cultural backwardness and bring Albania into the fold of Western “civilized” nations. In a speech to parliament describing the reforms, Zogu insisted that “retrograde customs that damage the State morally and materially” would no longer be tolerated. “We must understand that the geographical position of our State forces Albania as soon as possible to enter the ranks of civilized States” (in Tomes Reference Tomes2004: 158).

This policy shift at the center had direct ramifications for governance in the highlands. The immediate impact came with implementation of the penal and civil codes there. The main problem, as we will see, was that in order to fully implement the codes the state had to gain jurisdiction over domains once reserved for communal institutions. What ultimately weakened the state's claim to legal authority in the highlands was not only its manifest claims of authority, but also its attempt to bypass the earlier process of cultural legitimation and guarantees of social autonomy.

The government turned increasingly against local institutions in the post-code period, for a number of reasons. First, it had strengthened its administrative capacities by consolidating a national apparatus of administration throughout the country, including by expanding the presence of the national gendarmerie (Tomes Reference Tomes2004). With increasing police presence came more successful disarmament campaigns and dramatic improvements in taxation. The xhelep was the in-kind tax on livestock that was the main tax collected in the highlands, and in 1927 xhelep revenues were a staggering sixteen times higher than only two years prior. They continued to increase annually by an average 3.6 percent until 1929.Footnote 16

A second reason for the government shift was that a middle-class intelligentsia with growing influence increasingly decried Albania's cultural backwardness, and called for authoritarian measures to “civilize” Albanian society by applying a putative Western cultural model.Footnote 17 This elite particularly decried peasant law and communal institutions, which they saw as remnants of local cultural ways that had to be eradicated.Footnote 18

Third, confrontation with communal institutions was instigated when officials, especially from the Ministry of Justice, grew less tolerant of the special jurisdictional areas in the highlands that lay outside the purview of state authority. This intolerance intensified after passage of the penal and civil codes. The Ministry of Justice trumpeted the new laws as a great victory, “especially for the highlands…, where the fate and the rights of the population have thus far been judged arbitrarily by special committees following the traditions inherited from [customary law]” (in Musaj Reference Musaj2002: 187–88).

When the codes were implemented, voices within the state administration decried the continuing authority of local councils and other communal bodies. This became most prominent in a pivotal 1927 report that the General Inspectorate of Administration submitted to the Presidency of the Republic. In response to a complaint sent by the highland subprefecture of Malësia-e-Madhe, the Inspectorate warned that local councils seemed to exercise greater authority in the administration of local matters than did the subprefecture office. In some instances, the Inspectorate claimed, local councils blocked the gendarmerie from carrying out official subprefecture orders such as arrests. The Inspectorate suggested that corruption, crime, and violence in the highlands could be traced to the power of the councils and elders, and urged the immediate “abolition” of their authority and of customary law. The report is unclear as to the basis for this charge that customary law and its communal authorities were corrupt, abusive, and incited violence, and it seems doubtful that those authorities had changed their behaviors from the past. What had more likely changed was the vision held by government officials (who were still largely urban-based) as to what constituted a properly administered social order; the new vision categorically excluded autonomous collective bodies exercising legal powers independently from the state.

The Ministry of Justice framed the problem as a matter of improper jurisdiction over legal cases. In response to the report, in 1928 parliament passed a law “on reviewing inherited cases in the highlands governed by customary law.” It abolished the authority of elder councils and other communal institutions and required the “transfer” of legal cases from them to state courts. But state authorities in the highlands lacked the power to demand that legal cases be so “transferred.” For one thing, those handled by councils were not “cases” in the manner understood by modern bureaucratic systems of justice. No written documents or formal procedures were followed during hearings and rulings. Second, disputes were typically resolved in a few hearings, and sometimes in just one, and so there was no ongoing caseload to be transferred to state courts. The unrealistic law may have been intended as a mere political display. Alternatively, it might have simply reflected the ignorance of lawmakers living in the capital as to how elder councils operated in the highlands, and lawmakers' disregard for the knowledge and advice of the state's own local officials.

In addition to demanding the general “abolition” of councils' authority and customary law, national officials worked to encroach upon specific council prerogatives. For example, through the civil code the state claimed greater jurisdiction over the domain of matrimony. State officials in the highlands portrayed agreements for matrimonial exchange as a significant cause of conflict between clans, thus giving cause for the government to assert greater regulatory control over this domain. The state claimed the power to regulate brideprices, set limits on wedding expenditures, and establish procedures for households making nuptial agreements, which had to be registered with prefecture offices. One byproduct of state regulation in this domain was that it advanced women's rights in matters of marriage, child custody, and inheritance. But overall the measures further galvanized local councils against what they saw as undue government interference deep within the domestic and communal realm (Musaj Reference Musaj2002: 208–11). Political confrontations between councils and local authorities increased, as did practices of evasion.

The state's attempts to regulate other domains failed as well. Official data show that out of 1,800 murders penalized by state courts from 1930–1938, 738 were motivated by blood vengeance. As late as 1939, ten years after institution of the penal code, some 40 percent of deaths in the highlands were attributed to blood vengeance (Elezi Reference Elezi1983: 199–204). Banditry also seemed ineradicable, despite the Ministry of Interior enacting stiff penalties against convicted bandits and even though the government had developed a vast network of informants in the region.Footnote 19 Enforcement of the civil and penal codes made it harder to carry out more routine government activities such as tax collections (Meta Reference Meta1999: 89–90).Footnote 20 In the late 1930s, nearly two decades after the state had expanded its presence in the highlands, local officials complained to central authorities that peasants were still routinely submitting disputes to local councils rather than prefecture offices or state courts.

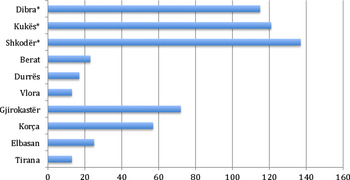

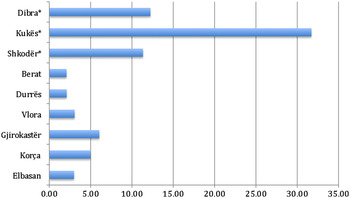

The rise in public disorder is displayed in the high rates of reported crime. One would normally expect crime levels to be higher in the more densely populated urban and lowland regions, but a paradox of modern Albania was that crime was overwhelmingly concentrated in the rural highlands. An internal Ministry of Interior report in 1935 showed that the number of men wanted for ordinary and political crimes in the highlands prefectures of Shkodër, Kukës, and Dibra ranged between 115 to 137, while the mean number for non-highland districts was about twenty-four (see figure 1). In per capita terms, the numbers of people per ten thousand wanted for criminal acts in the highlands ranged from eleven in Shkodër to thirty-two in Kukës. By contrast, the mean for districts outside the highlands was 3.5 (see figure 2).Footnote 21 The gendarmerie imposed collective punishments when people refused to reveal the whereabouts of family members who were wanted renegades. Family members were in some cases detained, while in others local councils were pressured to impose traditional punishments on them such as the burning of their homesteads. Local officials also employed local peasants as “hired guns” to pursue wanted criminals.Footnote 22 By using local actors to carry out the executive's legal mandates the state amplified the cycle of feuds and violence.

Figure 1 Total number of people wanted by the Ministry of Interior for criminal acts in 1935, by district (* denotes districts that encompass the highlands).

Figure 2 Number of people wanted by the Ministry of Interior in 1935 per ten thousand inhabitants, by district, based on 1923 census data (* denotes districts encompassing the highlands). Population data for the district of Tirana is unavailable.

The degradation of local political authority led further to an overall disintegration of the region's legal culture during the post-code period. With more than one path for legal redress now available, even the manner in which it was pursued became an object of contention. Local observers report peasant litigants strategically choosing to involve either state courts or elder councils in disputes, based on which they would provide the most favorable ruling. It also expressed a growing moral and spiritual destitution of highland society in the modern nation state era. The Roman Catholic priest Anton Harapi, writing in 1932, described this condition in regards to a dispute between two phratries in the Shala region over water rights:

They tried hard to resolve the matter but could not come to an agreement. One party wanted to resolve the issue according to the kanun [customary law]; the other, because that method did not suit it, appealed to the law and the courts. Each party had its strong claims, but the matter remained unresolved, hearts remained enraged, and the water of the well, instead of watering the fields, gushed over rocks. This is only one of many cases that prove to us that the Albanian spirit today belongs neither to the law [of the state] nor to lek [customary law]: the kanun is insufficient, while the law does not persuade him. He wanders about like a disoriented bird, smashing into everything with every movement. He cannot stay with the old if he accepts the new, nor does he know how; the new ways of life are a parody to him; he is too afraid to embrace them because he knows not where they will lead him. “It was better then,” says a man from Puka [a highland village], “when you feared no one but God; you knew what belonged to you, today it is no longer so….” His demoralization has reached rock bottom… (Reference Harapi1999: 126).

Government efforts to assert state legal authority by implementing the codes not only failed to bring adherence to state law, but also helped galvanize highland peasants to politically confront the state. This is seen in the changed political attitudes that local councils displayed regarding their willingness to cooperate with state officials. During the pre-code period councils had been relatively open to cooperating in the establishment of state institutions; now their political outlook became increasingly conservative and they came to see their mission as the defense of customary law. The more that councils resisted state authority, the more national officials found fault in the “primitiveness” and “backwardness” of local culture. Although the state displayed a conspicuous inability to impose a new social order, a widely distributed government report in 1937 boasted that it was successfully “teaching” highland peasants “basic notions of the state” and eradicating their “compromises against the payment of taxes, living in accordance with primitive custom, and refusal to recognize a central authority.” These were described as expressing traditional features of their society (Selenica Reference Selenica1937: 266). For the traditional elites of the highlands region, customary law became as symbol of an alternative social order and of resistance against an illegitimate and increasingly repressive political authority.

DISCUSSION

A primary cause of the growing social disorder in the highlands was that the state was not only fighting crime but also changing its mode of administration. The same local institutions that had acknowledged the legitimacy of state regulations in the initial, pre-code wave of state building were in the post-code period attacked and delegitimized. This destroyed the pre-code system that had divided authority between national and communal institutions.

The pre-code state succeeded in establishing political control in the highlands by compromise: instead of trying to seize full administrative and legal control, as was originally intended, it recognized the authority of communal institutions and customary law in specific domains of jurisdiction. Two aspects of this approach were particularly important. First, the state established its authority by communicating it in terms that were intelligible to local cultural practices and affirmed them. The besa agreements were not only formal agreements between national and communal authorities, but also acts that effectively institutionalized the state via local rituals. By following the besa ritual these agreements recognized both the rights and the limits of state authority. In other words, the besa institution forced government officials to articulate state authority as corresponding to existing highland cultural schemas. The hybridization of the state, and the formation of mechanisms bridging and binding state and society, were results of cultural work undertaken by local government officials—they articulated state claims in the language of local cultural practices, and treated local bodies as partners in local state building.

The second, and most important aspect of the government approach was that the besa agreements instituted a jurisdictional division between national and communal authorities. We must remember that jurisdictional claims are not claims to territory, but claims over the right to regulate specific domains of social life. This divided jurisdiction was not a strict and static arrangement, but rather a set of overlapping and sometimes ambivalent claims to regulation that left room for further negotiation. For example, we see in the besa document in Appendix 1 ambiguities in the very definition of “public order” and the ascribed roles of national authorities and local communities in its maintenance. The text demonstrates the compromises required to devise an administrative structure and jurisdictional division that reconciled radically incommensurate understandings of public order. One understanding was grounded in concerns of substantive justice based on self-help principles, the other in procedural justice and compulsory third-party arbitration. In a strictly formal reading, these differences led to contradictory definitions of what constituted a criminal act. For example, the besa demands full submission to the laws of the state, which prohibit murder, yet the agreement does not ban acts of vengeance, but can only—as the practice of the besa allows—suspend feuds for a determinate period (in this case one year). It demands that murder be prosecuted jointly by the prefecture and the councils, but makes exceptions for murders resulting from violations of honor. Yet most perpetrators would have justified their acts of interpersonal violence as a consequence of the other party having offended their honor. The document is unclear as to how one determines whether a murder was committed with the motive of defending honor, or which authority would make that judgment. Here the state's compromise with local communal practices shows the sorts of institutional contradictions it faced as it attempted to reconcile bureaucratic legal authority with communal institutions of social regulation. But it also reveals the degree of freedom that state officials had during this period in negotiating the terms of rule with local subjects.

Though tenuous, such jurisdictional divisions enabled state authorities to penetrate the highlands, albeit mediated by the power of local councils and other communal institutions. The latter arguably became not merely tools of the center but effective partners in local state building. The continued agency of local communities was also evident in the post-code period, when cooperation shifted to resistance while effective governing capacities diminished. Local public order consequently deteriorated in a way that not only harmed local communities but ironically also undermined national authority.

Why were jurisdictional conflicts not resolved, but instead maintained as ever-more-politicized bases of the struggle between state and society? Abbott's model of jurisdictional struggle between professions identifies a variety of mechanisms that enable the resolution of competing jurisdictional claims. One key factor is that jurisdictional conflicts between professions take place in the context of relatively institutionalized political, administrative, and legal frameworks. In such conflicts the state is often both the arena of conflict and a resource for parties, and is a means of establishing exclusivity for particular professions at the expense of others (e.g., establishing licensure requirements or legal criteria for the exercise of certain tasks). But in cases when the jurisdictional claim involves the limits of the legal authority of the state itself, the dynamics of jurisdictional struggle are directly political in nature. Their resolution therefore lies in a terrain in which political, social, and cultural claims operate simultaneously and methods of direct domination prevail.

Another important feature of the Albanian highlands case is that the system of divided jurisdiction was never fully formalized. This may have contributed to the organizational uncertainty that led post-code state builders to pursue the path of trying to eradicate communal institutions altogether. The lack of formalization meant there was no mechanism of internal differentiation that could resolve the conflict by institutionalizing distinct jurisdictional divisions and roles. In no proper legal sense did elder councils, assemblies, or other communal institutions ever become formal components of the state's administrative and legal apparatus. Their members were never considered formal employees of the state, nor did they enjoy the status of civil servants. The salary and benefits elders received were paid for through the traditional collection of fees. Jurisdictional conflict could therefore not carry on inside the state itself as a conflict between competing bureaucratic sectors, which could have been resolved internally through an administrative elaboration and definition of distinct jurisdictional domains. Instead, jurisdictional struggle took place as a political battle between communal bodies and state officials over their jurisdictional claims and counterclaims. This conflict's central mechanism stemmed from the ability of both groups to mobilize the same “client” base toward denying legitimacy to the others' claims.

The path of state building might have been different had the pre-code structure been formalized as a fully institutionalized form of divided governance. This might have been made similar to, though perhaps not identical with, the sorts of formal jurisdictional separations modern colonial states have instituted between state and customary law (Chanock Reference Chanock1985; Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996).Footnote 23 Such a system did not eventuate because Albanian state builders were deeply committed to a unitary national legal order and centralized legal administration. It is clear that the state's organizational framework for attaining this goal was too rigid to tolerate organizational innovations like those in the pre-code period.

CONCLUSION

The case of state building in the Albanian highlands demonstrates how the factors emphasized by classic state-centric models are insufficient for explaining how state authority is institutionalized among ruled populations. Such models assume state power to be a function mainly of the state's endogenous organizational capacity to coerce and to mobilize resources. Yet here we have the case of a state that increased its organizational capacities to coerce but proved unable to assert its claims of legal regulation. Its very attempts to assert control generated growing social disorder and difficulties in governance. Legal authority involves claims to the power to define acceptable norms of social behavior and sanction transgressors, and a state's claim of such authority cannot succeed based on political dominance alone, construed narrowly as possessing a superior means of coercion. The problem is not that such models focus on violence and coercion, the instrumental goals of actors, and political conflict—these are part of all processes of state building. The difficulty is that they assume what they are supposed to explain—the formation of new state organizations with specific, historically novel powers; they assume that coercive and regulatory powers exist by definition, that is, as components of the state in the theoretical sense. For this reason, such models disregard the crucial dynamics through which the institutions and unique powers that constitute the modern state are elaborated organizationally and articulated culturally.

The formation of state organizations with a monopoly claim over legal authority, even when their designers follow models of established states, is heavily constrained by the local institutional and cultural environments in which the process of state building takes place. In confronting such environments in peripheral rural regions without traditions of centralized rule, state builders engage in creative organizational work. They interweave state and non-state organizations and legitimize state authority through the mobilization of local cultural schemas. These organizational innovations are strained when state builders try to conform to standardized legal models, such as national legal codes, that require standardization and homogenization of legal understandings and the administrative practices of law. In such cases, tenuous divisions of jurisdictional domains and the respective legal authorities of state and rural institutions come under stress, producing jurisdictional conflicts that undermine state claims of legal authority. When there are no formal mechanisms to resolve jurisdictional conflict between state and rural institutions, efforts to impose legal authority generate political conflict and non-cooperation, which undermine both state-building goals and the welfare of subject populations. Building modern states inevitably carries political, economic, and cultural costs for modernizing societies. But those costs are particularly heavy for marginal rural groups to whom state building means not simply a recognition of new authorities at the expense of others but also a dismal increase in state repression, collective cultural stigmatization, and social disorder.

APPENDIX 1

This besa document established the terms of rule of the Albanian central government in the highland region of Mat in 1919. Source: Central State Archives of Albania, fund 152, record 1, 1919.

In order to secure our beloved homeland Albania, to secure peace and to increase the love and fraternity between each other, those of us who have gathered in Mat have agreed to commit to a general besa, and become subject to all the orders of the government in accordance with its laws.

(1) We are all brothers and have as our goal the best for our homeland.

(2) We recognize the government and are bound by our will and our soul to all the commands it issues.

(3) Every Albanian, whatever his issue or trouble, shall demand his rights from the government.

(4) Murder and the seeking of blood by one Albanian against another is banned for one year. For an entire year, blood vengeance will be suspended.

(5) Theft is forbidden, and an Albanian that takes the life of another will be punished as follows:

(6) His property will be confiscated and his family banished from the Mat region, the perpetrator's home will be burned down, and he will be sent to face a military court.

(7) He who steals the property of another will be punished by three months to three years in prison, and will pay double the value of the stolen property.

(8) For an Albanian that kidnaps the daughter or wife of another, kidnapping will be considered by the people as equal to murder, and will be punished in accordance with point 5.

(9) According to local custom, if one takes the life of another for questions of honor, or catches one in the act of stealing, the murder will be considered justified and the perpetrator will not be penalized.

(10) Dishonoring another and fighting among the people is not permitted, and will be punished severely.

(11) Firing weapons without the permission of the government is forbidden and will be punished severely.

(12) Those who take and offer shelter to criminal perpetrators in their home and do not notify the government or the local council of elders [pleqësi], but provide assistance to them, will be punished the same way as the perpetrators, in accordance with points 5 and 6.

(13) Italian soldiers and their equipment will not be touched. Anyone who tries to lay a hand on them will be hanged.

(14) He who cuts telegraph or telephone wires or steals poles will be handed to the Italian military court, which will issue its punishment.

(15) Those that did not accept and did not enter into this besa are considered enemies of the homeland and are not our brothers. For this reason their families will be deported from the country.

(16) All, young and old, will conduct their own affairs and will not engage in politics.

(17) Those who deal with politics and foreign propaganda are against the goal of organizing Albania or have the intention of causing disorder and upheavals, and will have their families deported and their homes burned to the ground.

(18) By offering our hand in besa to each other, we agree to uphold these agreements and protect the honor of our country.

(19) In accordance with custom, we give our pledge and sign this paper and agree that for its implementation we will follow the decisions of the subprefect and the commission.

(20) For all matters the people must address the Albanian Government, he who does not do so we do not consider our brother.

(21) If for any reason the government requires a national militia we will obey all commands issued by the government.

(22) In due time, after the government and commission have made their decision, the bearing of arms will be forbidden.

Burgajet, 5 March 1919

[signatories]

The establishment of a commission consisting of twenty representatives of the people of Mat to act in accordance with the rule of the government is hereby certified, as demanded by the honor of our country.