INTRODUCTION

In every neighborhood of Dakar, Senegal, large houses in various stages of construction stand as witnesses to and evidence of transnational movements of labor and capital. These ambitious building projects, funded by Senegalese migrants living and working abroad, have utterly transformed the city landscape, and their pervasiveness leads many Dakarois to assume that everyone must be migrating.Footnote 1 Intended as eventual family homes, investment properties, or a combination of the two, the innovative layouts and architectural flourishes of these not-yet houses echo lives lived elsewhere while drawing on local aesthetics and approaches to spatial design. Though some houses seem to near completion within just a year or two, most structures linger for several years or even a decade, slowly eroding as families and hired contractors wait for money transfers from abroad. Some constructions boast newly laid bricks or fresh paint, while others are obscured by overgrown vegetation and debris.

Dakar's half-built houses are not an anomaly, and such structures are likely familiar to many scholars who do research in contexts where globally circulating remittances infuse local economies. Development experts frequently index these projects as an “unproductive” use of migrant-earned capital or as “negative incentives” that discourage those supported by remittances from seeking employment (e.g., Kapur Reference Kapur and Kapur2005). In Senegal, as in many postcolonial states, the government regards these constructions with ambivalence: while often decried as wasteful or unnecessarily lavish, the state also acknowledges that they provide necessary and affordable urban housing solutions. Moreover, the Senegalese government has sought to tap into this housing boom through the formation of various state agencies and programs that facilitate and profit from migrants' projects and capital transfers (see Barro Reference Barro and Diop2008). Through these initiatives, the state has reconfigured the remitting migrant as a potential investor whose earnings and efforts can transform national futures. Migrant-built houses in Senegal and elsewhere have also caught the attention of comparative scholars who seek to understand the relationship between transnational migration and “home.” These theorists have indexed these ambitious houses as powerful symbols of emigrants' ongoing efforts to lay claim to local and national belonging (Thomas Reference Thomas1998; Pellow Reference Pellow2003), to accrue social capital (Buggenhagen Reference Buggenhagen2001; Reference Buggenhagen and Weiss2004), and to assert historical continuity in a local place, especially in a natal village (Van Der Geest Reference Van Der Geest1998). These studies often attend to the involvement of families in these construction projects and to the household transformations that result.

My work with residents of Dakar offers a complementary perspective that complicates the way we think about transnational migration, belonging, and “home.” Many Senegalese living abroad choose to build in Dakar not because it is their city of origin but because of the economic opportunities that the rapidly urbanizing capital offers. Houses built in this capital city are more likely to include étages (additional stories) and to be considered investments that require ongoing capital and construction. The houses that diasporic Senegalese slowly construct in Dakar are nearly always unfinished and are often uninhabited (see Osella and Osella Reference Osella and Osella2000); thus, for my informants, “house” and “home” are often disarticulated. These not-yet houses are in some ways turned inside out: their insides are not private or contained but rather spill into public spaces, where they are the focus of intense scrutiny and speculation. These constructions have profound impacts not on hidden domestic relations or households, I argue here, but on imaginations and experiences of the city as a shared space.

I gesture here to the work of Brian Larkin (Reference Larkin2004), who examines the expansion of pirated media in Nigeria in a climate of worsening poverty and increasing reliance on informality and illegality. He argues that the aesthetics of bootleg videos—whose images and sounds are degraded through techniques of replication—shape conceptions of time and space and produce very particular experiences of modernity. Larkin describes piracy as a global “infrastructure of reproduction” whose material artifacts bring modernity into view. Like Larkin, I take seriously the material reality of half-built houses, and I consider them not as aberrations of or alternatives to some “pure” or “original” form—one that bounds the household—but instead as legitimate and prominent urban artifacts that have social substance and consequence. These rising houses render transnational migration visible and tangible for many urban residents. In this essay, I pay close attention to the patterns of replication and repair, connection and anticipation of connection that characterize life in contemporary Dakar. I examine closely the competing exigencies that produce these half-built houses as material forms; amidst family expectations, multiple national taxation regimes, rising rent and food prices, and religious obligations, converting cash (which dissipates quickly in contemporary Dakar) into bricks, mortar, and shutters makes one's labor tangible and enables a reorientation of one's earnings, as an “investment” in the future (see also Guyer Reference Guyer2004).

The city's ubiquitous half-built houses—which are simultaneously rising and falling, ruined and repaired, intimate and public—are turning notions of belonging and diasporic presence inside out, as well. The fascination with housing construction in postcolonial Dakar reflects a larger cultural rubric that links construction with national development, one made explicit by Senegal's current president. Likewise, for urban residents, building a house is an important activity, one that both stakes claim to adult presence in the city and enables a future-oriented use of income. Low wages, the dismantling of state social programs, widespread land speculation, and chronic unemployment exclude most urban men from participation in housing-construction practices. Instead, the majority of building projects are initiated and sustained by transnational migrants who send money to families, business partners, and contractors in the city.Footnote 2 These half-built houses, slowly constructed as funds become available, act as placeholders for transnational migrants living abroad who hope to return to Dakar.

The structures, processes, sounds, and sights that I will describe are so pervasive and ubiquitous that they create the impression for some residents “left behind” that all of Dakar is under construction by the diaspora. From the perspective of most of my informants, then, building a house emerges not so much as a call by migrants for visibility and inclusion, but rather as a prerequisite for male urban belonging and individualized participation, one that is only available to those who have left. Abdou Maliq Simone (Reference Simone2004a) has suggested that urban belonging is not a matter of being able to “dwell” but rather involves the right to “future aspirations” and inclusion in economically productive networks and activities. Following this powerful intervention, I insist that urban participation in this particular locale is secured by actively and continuously building, by engaging in ongoing future-oriented techniques that carve out spaces of economic participation in a liberalized economy that emphasizes entrepreneurialism and self-sufficiency. Urban residents see these diasporic constructions as indisputable evidence that transnational migrants are, in fact, most at “home” in this cosmopolitan capital: these (often) absent residents can stake a claim to future presence and participation in the city in ways that non-migrants cannot. Moreover, while women “dwell” in the houses that transnational migration affords, it is most often men who build or are assumed by urban residents to build. In this way, urban belonging is also a highly gendered process, one that is imagined as contingent on male entrepreneurship. These ethnographic observations impel scholars of transnational migration to turn inside out existing theories that query the facile relationship between transnational migration and belonging and to consider the new exclusions created by global movements of labor and capital.

THE GENERATION OF CONCRETE

Since his ascendancy to power in 2000, President Abdoulaye Wade has popularized “construction” as a political-economic metaphor and as a literal state priority in the capital city. His urgent message of sopi (“change”) mobilized remarkable support among the country's disenfranchised urban youth, whose livelihoods had been deeply affected by structural adjustment reforms, rapid urbanization, and unemployment (see, for instance, Galvan Reference Galvan2001).Footnote 3 After his election, Wade allied himself with various international leaders and touted foreign investment as a cure for Senegal's economic woes. In particular, his administration prioritized massive investment in urban construction projects, with the aim of turning Dakar into West Africa's showcase capital, particularly as organizations and capital retreated from an embattled Abidjan.Footnote 4 These construction projects rendered impassable the two main arteries that linked Dakar's northern and southern sections, as existing surfaces and structures were uprooted to make way for foreign-funded roundabouts, overpasses, and tunnels. Lavish five-star hotels aimed at luring a global elite cropped up along the city's coastline. Meanwhile, prices for daily necessities and for transportation within the city skyrocketed. While some urban residents viewed Wade's grand public projects with hope and pride, many others grew frustrated with the aging leader's ostentatious spending and with his administration's failure to adequately address unemployment, escalating food costs, and mounting charges of political corruption.

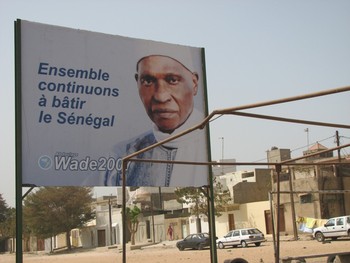

Despite widespread discontent, Wade was re-elected in 2007 on a platform that harnessed these construction projects: “Together, Let's Continue to Build Senegal” (Ensemble, Continuons à Bâtir le Sénégal) (see figure 2).Footnote 5 This message permeated the city through newspapers, radio and television broadcasts, leaflets, and billboards. In the months following Wade's re-election, a political movement began to crystallize within the president's party, the Parti Démocratique Sénégalaise (PDS). Dubbed the “Generation of Concrete” (La Génération du Concret), this nascent organization of party members sought to bolster support for Wade's son, Karim, in the 2012 presidential election. The catchy moniker made explicit reference to PDS's efforts to make “concrete” changes (rather than just offering empty paroles) through monumental building and infrastructural projects. But the name was also meant to valorize the strength and resiliency of the nation's young people, the “concrete generation,” who had been so crucial to the president's landmark victory in 2000. For Wade and his allies, foreign investment and ambitious construction projects had the power to transform the futures of Senegal's young people.

Figure 1 Map of Dakar, depicting the neighborhoods discussed in this article. The dashed lines indicate the two main arteries linking the city's northern and southern extremities, both under construction during the author's research.

Figure 2 A billboard erected by Wade's reelection campaign proclaims, “Let's continue to build Senegal together.”

Yet many of Dakar's youth, even those who had been key to the president's election in 2000, saw alternative futures and economic possibility as contingent on leaving this city-under-construction. In 2006 alone, over thirty thousand West African migrants were apprehended as they tried to seek clandestine passage by pirogue, a type of wooden fishing canoe, to the Canary Islands, an archipelago off the coast of Morocco that is under Spanish jurisdiction.Footnote 6 Another six thousand hopeful migrants are estimated to have died en route, though many officials fear the actual figures could be much higher. Dakar was the most popular point of departure for these voyages. In a 2007 address, Wade publicly blamed this “migration crisis” on the social pressure—exerted, in particular, he claimed, by mothers—to “construct a beautiful house” (in Bouilly Reference Bouilly2008, 16). In my interviews and conversations with Senegalese who had successfully migrated and with those who hoped to do so, many likewise emphasized their desires to build a home for their families and themselves. What remains obscured by Wade's rhetoric and by my informants' commonplace professions are the reasons that the house has come to play such a vital role in the social imagination, and it is this question that animates this essay.

While pirogue trips to the Canary Islands achieved international visibility during the time of my fieldwork, these transnational flows are by no means new, nor are they the only sort of migratory networks that link contemporary Senegal with other continents. A prolific body of scholarly literature traces these complex and shifting global routes, frequently beginning with Soninke labor migration from the Senegal River Valley to France in the mid-nineteenth century (Manchuelle Reference Manchuelle1997), but these outward flows have intensified since the economic crisis of the 1980s and 1990s. Today, Senegalese of various ethnic backgrounds migrate to other parts of Africa, as well as to Europe, the United States, Asia, and the Middle East, to secure both skilled and unskilled employment (Riccio Reference Riccio2005; Carter Reference Carter1997; Stoller Reference Stoller2002; Tandian Reference Tandian and Diop2008) or to seek educational opportunities at universities and prominent religious schools. The Senegalese government estimates that 76 percent of urban households have at least one member working abroad (République du Sénégal 2004). Although migration is popularly considered a male-dominated activity in Senegal, women are important actors in decisions that involve migration and remittances (Buggenhagen Reference Buggenhagen2001), and women and families increasingly participate in these migratory movements (Kane Reference Kane, Bryceson and Ulla2002; Ba Reference Ba and Diop2008). Islamic brotherhoods—most notably the Muridiyya, also called the Mouride Way—have played a particularly central role in solidifying and extending Senegalese migratory networks (Diouf and Rendall Reference Diouf and Rendall2000; Ebin Reference Ebin1992; Babou Reference Babou2002).

For decades, migrant earnings have been crucial to the economy of Senegal, a country with few profitable natural resources or other dependable sources of national income. Diasporic members of Islamic brotherhoods send money to religious leaders in Senegal (called marabouts) who, in turn, use some of this capital to care for community members and to finance construction and infrastructural projects in areas neglected by the state (Cruise O'Brien Reference Cruise O'Brien1971). Migrants also send remittances directly to families, particularly to female family members, who put the monies toward household expenditures like food, religious ceremonies, clothing, and education (Buggenhagen Reference Buggenhagen2001; Reference Buggenhagen and Weiss2004). Other migrants use their earnings to invest at home in village development projects (Kane Reference Kane, Bryceson and Ulla2002), small businesses (Diatta and Mbow Reference Diatta, Mbow and Appleyard1999), transportation, and housing construction. These hyper-visible displays of capital and tales of success abroad, various scholars have shown, have produced fantastic expectations and imaginaries of “exile” and “the elsewhere” (l'ailleurs) (Lambert Reference Lambert2002; Mbodji Reference Mbodji and Diop2008; Fouquet Reference Fouquet and Diop2008). Although urban residents are frequently confronted with the grim realities of migration—through news stories of tragic pirogue voyages, for instance, or tales that circulate of the racism and poverty migrants often face abroad—“the diaspora” nonetheless surfaces in contemporary Dakar as a powerful cultural myth, as a solution to current economic hardship and vanished opportunities, and as a means of achieving (especially masculine) adulthood.

In what follows I look specifically at how various Dakarois—both those who have lived abroad and those who have not—interacted with, experienced, and defined the diaspora through the city's rising houses and villas. I must emphasize that this data was collected just prior to the worldwide collapse of housing markets. In fact, frenzied housing construction in countries like Spain during these pre-bust years actually provided employment opportunities for many Senegalese laborers, who, in turn, were often eager to invest in their own housing projects back home. The ongoing housing-construction projects that characterized the city in 2006 and 2007, I argue, were tied to a broader cultural logic at play in Dakar, one that linked urban and national futures to investment in large-scale construction. These activities and artifacts must therefore be placed alongside and imbricated with Wade's high-profile urban projects and his party's political rhetoric and organizations. While housing construction is not funded by migrant earnings exclusively, this was nonetheless a popular assumption in Dakar, one that shaped how urban residents related both to an imagined “elsewhere” and to the city in which they lived.

THE CONTEMPORARY HOUSE IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The contemporary house in Dakar has a complicated history, one that speaks to the shifting relationship between the postcolonial state and its urban residents. During colonialism, so-called “African” quarters were spatially segregated from the “European” sections of the city, including Plateau, the administrative and financial center of Dakar inhabited by French colonial officials, their families, and other elites. The architecture of contemporary Plateau, which still houses the city's elite,Footnote 7 displays its colonial heritage; the grand villas with étages and administrative buildings built by the French remain, in various states of preservation. The Africans lived on the city's margins, just close enough to be able to supply labor to the European district, in homes dismissed by the colonial state as impermanent and even insalubrious (Ndione and Soumaré Reference Ndione and Soumaré1982; see also Betts Reference Betts1971).

In the late 1950s, just prior to independence, rapid urbanization and fears of outbreaks of disease in these African districts prompted colonial officials to institute programs for relocation and “sanitation” (see Betts Reference Betts1971). The Organization for Housing at Moderated Rents (OHLM) and the Real Estate Company of Cap Vert (SICAP) emerged; these public housing initiatives aimed at providing affordable housing to selected Dakarois with moderate incomes. SICAP and OHLM gained momentum after the fall of colonialism, when state officials were particularly interested in experimenting with styles of community making that broke with the French grid system, drawing in particular on Scandinavian notions of the modern suburb (Bugnicourt Reference Bugnicourt1982). These homes, which benefited state employees and other middle-income workers, were rather modest and small, with little room for extended families or visitors from the village, reflecting socialist ideals and European notions of family. The land was owned by the state.

While some residents received state assistance in making permanent homes in the city, scores of people that had settled in sections targeted for development were uprooted to make room for new construction and relocated to peripheral areas, both on peninsular Dakar (such as Grand Yoff) and on “mainland” Senegal (such as Pikine). These urban and peri-urban spaces have unique and complex histories of settlement and land use that I cannot detail here. What is of central importance to my argument is the intimate involvement of the postcolonial state in the production of the urban “house” (as distinct from “dwelling”), a claim of access to urban space and a privilege available to some and not others. Those resettled were forced to continue to “dwell”—to live in impermanent situations where there was no guarantee that they would not be removed by the state again (Tall Reference Tall1994). “Irregular” settlements quickly expanded. Residents in these unauthorized zones had no access to urban infrastructural benefits, such as potable water and electricity, and their participation in markets and urban exchanges was made more difficult by their peripheral situation (Ndione and Soumaré Reference Ndione and Soumaré1982; see Simone Reference Simone2004b).

Pockets of privately owned land existed in Dakar from the time of colonialism, and in the 1970s some Lebu inhabitants and others who had acquired land through sale or favors began to sell it,Footnote 8 encouraging intense real estate speculation and creating “a class of private real estate promoters” (Ndione and Soumaré Reference Ndione and Soumaré1982: 113). This situation of land speculation was exacerbated by the “Improved Parcels of Land” project. In 1971–1972, the state partnered with the World Bank to create Parcelles Assainies,Footnote 9 a new approach to affordable housing that offered land ownership at the margins of the city to lower-income urban residents (Tall Reference Tall1994). The World Bank and other governing bodies promoted private land ownership as a crucial component of a stable democracy and a liberalized economy. Some of Parcelles' residents, in turn, sold their land, contributing to the speculation happening in places like Yoff and Grand Yoff and further widening the gap between “dwelling” on and owning land.

These government activities and policies thus index a particular relationship between the postcolonial state and its (favored) citizens, one that combined reconfigured colonial institutions with socialist notions of state intervention, and that produced particular patterns of access, ownership, and permanence. In recent years, intense efforts at liberal reform in Senegal have included the privatization and “regularization” of land. Land outside of Dakar continues to be administered through village authorities, but the Ministry for Urbanism now controls the sale and purchase of terrains (plots of land) within the city.Footnote 10 SICAP has thus become a “privatized” real estate company, though the state is considered a major stakeholder. HLM (as the actual housing sections are called), SICAP, and Parcelles Assainies are now simply names of sections of the city; the complex relationships between the state and its people that they once described are now obscured. In the absence of state support for housing and amidst ongoing “relocation” projects, urban residents have become increasingly reliant on transnational migrants to help provide affordable and dependable housing options, an observation echoed by Tall (Reference Tall1994: 139): it is this real and perceived link between contemporary housing construction and transnational migration that I explore next.

TRANSFORMING URBAN LANDSCAPES AND ECONOMIC TERRAINS

I focus my analysis in this section on four Dakar neighborhoods, each with its own unique history of settlement and building practices. Early in my research, “Cité des Millionaires,” a neighborhood in Grand Dakar, seemed like the ideal place to begin, since the quarter of Grand Dakar is described as one of the first locations for migrant building projects in the 1970s (Tall Reference Tall1994: 142). A couple of urban residents had explained to me that the name of the Cité referred to the fact that this particular neighborhood was one of the first parts of the city (aside from Plateau, described above) where one could find houses with étages. I was told that these homes had been built by “millionaires,” by migrants who had gotten “rich” working abroad. I had therefore envisioned grand structures and gated entrances suitable for the “millionaires” who had built them.

Instead, I was astonished to find a neighborhood with relatively few ongoing construction projects and houses worn with age. Moreover, no one with whom I spoke during my visit knew anything about the origins of the neighborhood's name. When I explained that I was interested in studying the impact of money transfers on housing construction in Dakar, bewildered residents suggested that I instead visit Yoff or Parcelles Assainies, sections of the city that had been dramatically shaped by diasporic construction practices in recent years. There, one woman explained, I would find evidence of migrant-earned capital: grand étages, and many people building. For this woman and many others I spoke with, newer construction projects were evidence of enduring relationships with the diaspora. Because there were few ongoing building projects in the neighborhood, many residents assumed that flows of migrant-earned capital must be headed elsewhere in the city. Continuing relationships with the diaspora were made tangible and visible, I quickly learned, through active construction projects. Moreover, geographical names like Parcelles Assainies (often called simply “Parcelles”) and Yoff were employed in conversation as culturally transparent metaphors that indexed income levels, rates of flows, and degree of construction.

Yoff and Parcelles Assainies certainly do stand in stark contrast to Cité des Millionaires, as residents in Cité had pointed out. During fieldwork I lived first in a rented apartment in Parcelles, in a house built predominantly with diasporic capital (see figure 3). In recent years, migrants have played a dominant role in construction in this sprawling section of the city, where they erect family homes that often include an étage to be rented out as an investment (Tall Reference Tall1994: 146). Over the past decade and a half, Parcelles has been transformed from a low-income housing experiment into a densely populated neighborhood that, in the words of one of my interlocutors, “would not exist without the diaspora.” This intense population growth has been fueled in large part by the settlement of transnational migrants' families from other parts of Dakar and from rural areas, but also by the more affordable housing options these constructions provide to newcomers, many of whom come to the city with the hopes of earning money and migrating abroad. Tall (Reference Tall1994) has suggested that constructing in this neighborhood offered migrants a degree of prestige, but my own research showed that the neighborhood's status has faded as the area has become more populated. Instead, Dakarois often explained to me that Parcelles offered more affordable land than in other parts of Dakar and yet was still in close proximity to economic opportunities.Footnote 11

Figure 3 The house in Parcelles Assainies in which I lived in 2006 was built largely with capital from the diaspora. Though it may seem “finished,” the owner described it as an ongoing project. The third floor addition, unpainted and incomplete, testifies to her assertion.

The houses migrants construct in sections like Parcelles are undeniably inspired by time spent abroad: Mediterranean tiled roofs, “American kitchens,”Footnote 12 Parisian balconies, and Western-style bathtubs point to the origins of the capital used to build these homes. At the same time, these houses nearly always incorporate a more “African”-style family gathering space, one that is either enclosed or open-air, as well as other definitively African exterior aesthetics (see Pellow Reference Pellow2003). Some migrants buy undeveloped lots or raze existing constructions to start from scratch, while others extend vertically on existing properties, building étages. As noted earlier, building plans often combine family living spaces with individual rooms or entire étages that are rented to single men or families who come to the city to find work. The houses-in-process of Parcelles thus exhibit transnational migration's profound effects on urban spaces and movements, and they collapse the assumed boundary between housing-for-families and housing-for-investment.

In 2007, I moved to a seaside neighborhood in Yoff that was being dramatically transformed by ambitious housing-construction projects. The area in which I rented is located just across from the international airport and was home to well-to-do transnational families (many of whom have lived or still do live abroad), expatriates, government ministers, and prosperous Senegalese merchant families. Yoff more generally was not as densely populated as other sections of the city, though construction was intense and, in many cases, rapid. Migrants have been lured to the area because it is less congested, boasts spectacular ocean views, and offers privacy and prestige. Some of the neighborhood's finished houses remain vacant most of the year; the Senegalese who have invested in their construction, the majority of whom are transnational migrants,Footnote 13 typically prefer to rent to expatriates, who often pay upwards of 1 million CFA (US$2,000) per month. In the shadow of these climbing structures there were also modest houses with no electricity or running water. My friends and interlocutors often pointed to these as evidence of areas where there were no transnational migrants; one could tell because “there are no étages,” an unmistakable sign for many in urban Dakar of concentrations of diasporic capital.

Alongside well-appointed and occupied villas, other structures languished in the sun and disappeared behind encroaching trees as families waited for money to continue these projects. Many of these not-yet-houses of Yoff and elsewhere in the city were inhabited by men brought from the village to tend to the property (Figure 4). Some were paid a small salary for their services, while others paid rent to the owner in exchange for the opportunity to squat (and therefore avoid the high rents of the city). Still others worked as builders for the project and were thus permitted to occupy the structure as part of their salary arrangement. Villagers also served as gardiens, watchmen or custodians paid a small salary to tend to and secure inhabited villas and apartment buildings. Many of these villagers were Serer, an ethnic group concentrated in rural areas in west-central Senegal and the Sine-Saloum delta region, and most were poor even by Senegalese standards. They often brought their families to live with them. Their wives frequently took advantage of their position in the city and supplemented the family's income by washing clothes for other families or selling plates of fish and rice at lunchtime, particularly to the laborers building the massive villas (many of whom are also Serer). In the small corner of the neighborhood where I lived, Serer was spoken with remarkable regularity; in most of Dakar's public spaces, in contrast, interactions take place almost exclusively in Wolof or French.

Figure 4 A not-yet house in Yoff cared for by a Serer gardien. Clothes drying on the unfinished walls indicate occupation by a villageois.

Elsewhere in Dakar, too, the building practices of transnational migrants were said to be transforming the urban landscape and patterns of belonging, in different ways. This was the case, for instance, in what is now called SICAP Liberté III, a neighborhood originally built by the state to house police officers and their families. Atouma, a man in his thirties who worked selling tires in Medina, brought me to visit the neighborhood that he had called home since birth. His father was a former police officer, and his family had acquired a simple one-story house through SICAP's affordable housing programs in the late 1950s. While many of the modest houses in the neighborhood were constructed during this initial building phase, several on each street boasted newer, vertical additions, which residents explained were made possible by migrant transferts. Atouma was excited to show me his family home, which, thanks to money sent from abroad by his five brothers, was being transformed into a climbing six-story structure with unobstructed views of the dwarfed neighborhood below.

These emergent houses testify to a much broader shift in the relationship between state and citizen in contemporary Senegal. Although this neighborhood's residents once relied on the paternalistic state to help them construct family homes and carve out spaces of permanence and belonging, the move toward liberal notions of economic participation, individual empowerment, and privatization of land has meant that people are turning increasingly to transnational migration, an assemblage of individual- and family-level strategies, to construct houses and claim access to urban resources. As the state's involvement wanes, transnational migrants shoulder more of the responsibility for urban development and growth (see also Tall Reference Tall1994). Residents like Atouma's family still have a bit of an advantage, however, since constructing a house does not require, in their cases, buying a new plot of land. The cost of a square meter of land in Dakar was described to me as four to six times what it was a decade ago.Footnote 14 In this way, patterns of access and exclusion institutionalized by the state half a century ago continue to shape configurations of urban space and belonging in contemporary Dakar.

Through a discussion of building and dwelling practices in four different sections of the city, I have aimed to illustrate the complex patterns of access, construction, and occupation that characterize life in contemporary Dakar. These construction projects are transforming both the city's space and demographics as more rural people arrive seeking employment in housing-related services and industries. The frenzied focus on building houses coincides with a broader, state-supported emphasis on transforming economic futures through investment in ambitious urban construction projects.

THE PROBLEM WITH DWELLING

Here I want to reflect on dwelling—the process of inhabiting a space—both as an everyday worry for urban residents and as a conceptual problem for social theorists. The afternoon I spent in Atouma's neighborhood illuminated for me the increased reliance of Dakarois on transnational migration as a means to achieve their goals, like the construction of a family home. Our meeting also revealed the complex temporalities and ongoing processes involved in housing construction and urban belonging, and I will focus on these in this section. Atouma had lured me to SICAP by explaining, “I want to take you to see the house I was born in.” I was rather bewildered, therefore, when he brought me to an uninhabitable five-story structure. It was easy to see why he was proud to show me the ambitiously designed structure, with its sinewy staircases and impressive views. What I found curious was his assertion that he had been “born” there, when the raw walls and uneven cement floors betrayed its newness. There was no original foundation upon which the family was building; the entire lot had been razed and the walls rebuilt from scratch. When I asked Atouma when the house was likely to be complete and ready for occupation, he seemed bemused and shrugged, insisting that his family had never discussed that. In the meantime, he lived with his mother's sister a short walk away.

This was certainly not the first time that my own ideas about the point and directionality of building a house had seemed out of joint with those of my informants. A couple of months before I met Atouma, I had toured the emergent home of Ousmane, a middle-aged man of Lebu descent who was building a villa in an elite section of the city called Ngor. Ousmane was a returned migrant who had worked as a laborer in France and had returned to Dakar to begin his own housing constructing company. He had laid the foundation for this ambitious family villa nearly three years before, but it was evident that no work had taken place for quite some time (see figure 5). As we approached the staircase, I asked Ousmane what he had planned for the étage, and he became wildly excited. The second floor, he explained, would be built for his future second wife and for the children they would have; perhaps, he would even build enough bedrooms to take a third wife. Although he had not yet found a second wife, he assured me that the elaborate plans he had for the second floor of his villa would make his taking one a certainty.Footnote 15

Figure 5 Ousmane (at the far right) describes his plans for an étage.

Touring these emergent villas with Atouma and Ousmane, I was made aware of the temporal incongruities involved with housing construction. Claims to have been “born” in houses not yet suitable for living, open-ended plans for building, aging walls without roofs, and families that are contingent on future étages—these fractured and often contradictory trajectories defy teleological narratives of progress and development (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999). Building a house in Dakar, I suggest, is not a linear process but instead involves many stops and starts, simultaneous creation and deterioration, revised histories and fantastic ideas of future possibility. My ethnographic findings also call into question the participants' actual goals. A large number of houses being constructed by transnational migrants and their families remain incomplete, even uninhabitable; many of the families who construct them do not live in them, and some of the families for which they are designed are not yet assembled. Dakarois constantly emphasized to me the importance of building, of rendering concrete one's ongoing ties to the diaspora.

Despite the ubiquity of these unfinished structures, much of the existing literature on the house as an anthropological problem would render the processes and artifacts I have described as outliers, as exceptions to the general rule that one engages in building processes to produce a house to live in. For many who write on the topic, the house is a material reflection of abstract ideas about identity, social values, wealth, and belonging (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Pouillon and Maranda1970; Bloch Reference Bloch1971; Waterson Reference Waterson1990; Hestflatt Reference Hestflatt, Sparkes and Howell2003; Tell Reference Tell2007), and this physical structure is likewise thought to have a profound effect on social relationships (Lévi-Strauss Reference Lévi-Strauss1983). One can even “read” the house for clues about the culture that has built it (Keane Reference Keane1995). These divergent analyses share a theoretical assumption that the house is both more than the sum of its parts and an objective reality. Howell, in fact, suggests that the house is an appealing analytic concept because it resists deconstruction, thus enabling the ethnographer to “avoid the pitfalls of definitions, and, hence, engage in more meaningful comparative research” (Reference Howell, Sparkes and Howell2003: 32).

For those with whom I lived and worked in Dakar, however, the house was not considered a stable object, concept, or fact; it was instead caught up in very literal and ongoing processes of construction and deconstruction. Many theorists who have sought to push beyond the house as a reified object have turned their ethnographic gaze to the process of dwelling. These scholars describe the house as a dynamic space (Carsten and Hugh-Jones Reference Carsten, Hugh-Jones, Carsten and Hugh-Jones1995), and several suggest that the house only becomes culturally meaningful and distinct from other constructions through the process of dwelling (Robben Reference Robben1989). Miller (Reference Miller and Miller2001) has paid particularly close attention to the materiality of houses and to their power as cultural forces, but his attention, too, has been focused on the lives lived “behind closed doors.” Heidegger (Reference Heidegger1971) further argues that dwelling is made possible by building, and that building necessarily has dwelling as its end goal. These theories, while important scholarly interventions, have little to offer an analysis of Dakar's houses-in-process. Are these emergent constructions without meaning or specificity, since so many are unoccupied? Is it only through dwelling, through the making of a household, that the house is refashioned or that it becomes socially significant? What happens when the “house” is not an objective reality or given category, but rather a blurring of present circumstances and future possibilities?

I focus here not on the process of dwelling, but on the activities and artifacts of building as unlinked from dwelling. Whereas dwelling describes a day-to-day relationship with an already built (or at least habitable) structure, building references an assemblage of practices and discourses that articulate future realities and latent possibilities. Building is not passive, but rather is an ongoing and active engagement with physical materials, abstract hopes, available capital, networks of people, and spatial constraints. Ongoing construction, unlike dwelling, also testifies to an enduring relationship with flows of capital from the diaspora; as we have seen, residents of Dakar explicitly link building sites and practices to migrant “presence.” For my informants, dwelling was something quite different from building. Whereas dwelling (habiter) involved daily processes and activities, truly living (vivre) in the city required future-oriented spending (typically referred to as investissement) and involved participation in markets and decision-making. Building a home was an important way to claim a sort of permanence, a future participation in and access to the city. This distinction is echoed in the work of Abdou Maliq Simone (Reference Simone2004b), who insists that African urban belonging is not simply a matter of having access to housing or services, but rather involves the right to aspire and to pursue goals.

Who exactly belongs to the city and who is able to benefit from its resources is an increasingly contentious issue in Dakar. As I described earlier, neoliberal reform in Senegal has involved the dismantling of public programs and agricultural subsidies, privatization of state institutions, and the celebration of foreign investment as the foundation of the nation's future. As rural areas become increasingly marginalized by these policies and values, men and women leave villages across Senegal to seek employment in the country's capital. Some are lured by the hopes of jobs in the construction sector; many see Dakar as a stepping-stone to getting abroad.Footnote 16 At the same time, political violence and economic collapse elsewhere, in places like Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, and Liberia, have made Dakar, the capital of an ostensibly stable democracy, an increasingly attractive destination for foreign nationals.Footnote 17 As I alluded to earlier, the 2002 coup d'état in Côte d'Ivoire had particularly profound effects on Dakar. Violence and instability forced many residents to flee to Senegal and also encouraged the rerouting of huge sums of capital from Abidjan to Dakar. Because anyone can purchase land regardless of their residency status or nationality, many Ivoiriens have invested in real estate in Dakar, further contributing to land speculation and inflated rents. Moreover, many nongovernmental and international organizations have relocated from Abidjan to Dakar, bringing more expatriate workers to the city and spurring price increases and real estate speculation.

Dakarois are relatively receptive to migrants from rural areas and other countries, and many of them express pride that so many ethnic groups, nationalities, and religions are able to peacefully coexist in their city. At the same time, this urban influx has strained Dakar's infrastructure and has exacerbated tensions over limited resources and scarce jobs. Despite President Wade's ambitious efforts to transform Dakar into a world-class city through the construction of five-star hotels and modernized highways, the majority of the city's residents found it increasingly difficult to make ends meet. Sections of the city where rents were more affordable grew crowded, and seven or eight young male migrants from rural Senegal might share a single room. Constant price increases in fuel, water, food staples, and imports wreaked havoc on household budgets during my stay. New arrivals and longtime residents alike worried aloud that their stay in Dakar was always provisional; if the cost of living continued to rise they would be forced to return to their village or move in with family.

There was no real housing shortage in Dakar, but there was a dearth of affordable housing. The average taxi driver, for instance, made perhaps 40,000 CFA a month (US$80); but this sum often had to support a dozen people, as Senegalese families are typically large and many men are unemployed or underemployed.Footnote 18 A rented single room within someone else's house could easily cost 20,000 CFA or more. Little was left after one purchased necessities like food, cooking fuel, and clothing. In addition, many cab drivers and other workers came from villages, and their residual income often had to be sent to support rural households that were kept running by remittances. This left little or no income for savings or for other important expenditures such as baptismal ceremonies and funerals, school fees, or healthcare.

In contrast, building a house, according to my informants, enabled a complete reorientation of capital, priorities, and expectations. Savings accounts and home loans were not popular or accessible economic strategies for the majority of those who built.Footnote 19 Instead, fistfuls of cash sent via Western Union or passed by hand though transnational networks of migrants, merchants, and families were put directly into purchasing bricks, mortar, and window shutters. Foundations and walls rose slowly and in spurts as money became available, often over many years or even a decade. While it could take years of stop-and-start construction before a house could be occupied, engaging in this ongoing process was nonetheless a public proclamation that one intended, at some point, to make an emergent space a home. Regardless of whether they constructed family homes or investment properties, migrants and their families staked claim to future economic and social presence in the city.

The case of Ousmane, the building contractor who returned from Paris to build his family home, provides a particularly insightful example of the possibilities that are imagined to be opened up by building. His plans to construct well-appointed living spaces for a family that did not yet exist exemplifies the temporal reorientation made possible through home construction. Rather than worrying about daily expenses and “getting by,” constructing a house enabled Ousmane to make projections about the growth of his family. The house, in fact, was thought to bring about the family. Many Dakarois with whom I spoke insisted that having a family was contingent on first beginning to build a home. The dozens of taxi drivers that I interviewed and worked with daily were among the most vocal about this. None of them owned or were building a home in Dakar, and most lived hand-to-mouth, struggling to make ends meet and repay debts. Those who were married rented tiny apartments for their families or lived alone in the city while their wife (or wives) and children remained in the village. But many were unmarried and lived with their parents (if they were from Dakar) or rented a small room, often shared with other single men. While Senegalese have typically sought to marry young, the economic pressures involved with marriage payments, ceremonies, and having children, especially in Dakar, have meant that many urban men remain single well into adulthood.Footnote 20

Both single and married men lamented that they could not marry (for the first time or with additional wives) because they were unable to build a house. In fact, unless he is able to own his own house a son is not truly the head of the household (Buggenhagen Reference Buggenhagen2001: 382). Seydou, a taxi driver in his thirties, told me how he had paid 500,000 CFA to board a pirogue headed to the Canary Islands, desperate to find work in Europe. His attempt had failed, but he insisted that he would try again. He tried to explain to me why he had risked so much to go abroad: “Women today demand millions of CFA [thousands of U.S. dollars] and a house before they will consider marriage. They say it's hard abroad. But no matter how hard it is, migrants [living abroad] are still able to manage. If you work abroad, you can have a house [gagner une maison]. You can build. Migrants don't have to rent.”

Seydou's assertion typifies the assumption among many urban men that marriage is increasingly reserved for those who are able to migrate and, as an implicit corollary, build a house. His sentiments were echoed by Bocar, a Toucouleur man native to Dakar who had a wife and three children. Bocar had only left Senegal twice, both times as a hopeful clandestine migrant. Though he had close friends who had died trying to reach Europe, he was eager to try again: “How can I think of staying? There are no jobs, and everything costs so much. Life in Senegal is expensive. And renting is not living [vivre]…. It is not good for my family to live like this.” Bocar clearly felt that his family's well being was being threatened by their need to rent. Although native to Dakar, he still saw his presence there as contingent and precarious, and he actively sought avenues abroad so that he could make deeper roots in the city.

From the perspective of many Dakarois I spoke with, the building of a home is also important because it represents a break with “remittance” practices and signals an interest in “investment” on the part of the diaspora.Footnote 21 Remittances are imagined, in most cases, to alleviate short-term money concerns, to sustain a household and keep it going. In Senegal, a migrant often sends money, perhaps on a monthly basis, to his wife or his mother (or even to his sister) to take care of the family's daily needs for food, rent, schooling, and clothing. By contrast, my research found that migrants seeking to build houses in Dakar often rely on help from a brother, a friend, or a business associate or contractor who receives the money and puts it to use. That is, money sent for housing construction is kept separate from money sent for households, and signals participation in entrepreneurial activity.

The distinction between investment and remittance is to some degree a geographical one. Unlike “the village,” where life is imagined to be arduous and luxuries are few, Dakar is often experienced as a space of relative excess and indulgence. While a house in the village is seen as a necessity, constructions in Dakar are described as ostentatious and costly. Further, one builds in a village for the benefit of one's family or because one was born there; in Dakar, people are not always constructing for their families, nor are they necessarily native to the city.Footnote 22 Migrants and families who choose to build in Dakar are particularly interested in the potential for economic belonging and profit that such projects provide.

This was made particularly clear in a conversation that I had with Mansour, a middle-aged man from a village in southern Senegal who had worked for two years in Saudi Arabia and now owned a home furnishings store in Yoff. He chatted with me at length about his investments: his shop, called “Confort Mondial” (“World Comfort”), which sold imported living room sets and bedroom furniture and catered specifically to transnational migrants constructing in Dakar, and about the two houses he had built, one in a neighborhood of SICAP, another in a section called Ouest Foire. Surprisingly, however, when I asked which of these emergent houses he and his family lived in, he responded that he lived in neither. He rented the houses out to other families, and he and his family lived instead in a small, rented apartment in another section of the city. He said that he would likely move into one of these houses eventually, once he had exploited them as rental properties. Mansour's surprising revelation unhinges the migrant-built “house” from “dwelling,” and draws our attention instead to the temporal deferment involved with investing and building.

Theorizing the house in terms of dwelling thus misses the complex and diverse practices involved with migrant housing construction in Dakar. What happens when, rather than considering the half-built house to be an outlier, we think about it as a widespread reality? For my informants, these incomplete houses offered a glimpse not of abandoned projects or unmet goals, but of what could be; they represented latent possibilities and future articulations rather than present impossibilities. What does it mean, then, to live in a city that seems to be entirely under construction, in large part with capital from the diaspora? If belonging is contingent on building, where does this leave city residents who cannot migrate?

BELONGING TURNED INSIDE OUT

An interesting vein of scholarly literature reflects on the house as an assertion of belonging and presence on the part of the absent migrant. These ethnographic accounts trace the transnational linkages and flows that both engender and necessitate these ambitious constructions, and they pay close attention to how the migrant is made spectacularly present despite his bodily absence. Migrants frequently build a “home” in their natal villages as a means to resume historical and personal connections, but they do so in ways that also call attention to their transnational privilege and experiences, particularly through architectural design and imported materials (Thomas Reference Thomas1998; Van Der Geest Reference Van Der Geest1998). Others build homes in emergent areas and unfamiliar cities, thus profoundly reshaping their attachments with “home” while creating new places and forms of belonging (Pellow Reference Pellow2003). These new houses also have transformative effects on the families who live in them, on the households that they contain and nurture. In an especially useful scholarly piece, Buggenhagen (Reference Buggenhagen2001) examines the reconfiguration of domestic relationships and hierarchies amidst new transnational forms of belonging and wealth in Senegal, and she foregrounds how the migrant-built house actively extends and binds kin relations and produces ongoing circulations of capital and economic opportunity.

While insightful, these accounts are more narrowly concerned with the motivations and desires of migrant-builders themselves and with how their families participate in and are affected by these projects. These analyses focus exclusively on houses as dwellings—as places that contain domestic relations and that structure households. In doing so, they provide scant information about these constructions as public artifacts and neglect the ways in which these not-yet houses transform non-migrant livelihoods and spaces. How do the rising and crumbling structures of urban Dakar come to life, and how do non-migrants interact with these imposing signs of urban belonging? I turn my attention here to the material reality of these half-built houses and to the ways that residents perceive these unfinished structures as ubiquitous features of contemporary Dakar's landscape. I take my cue from recent scholarship that tends to the material replication, construction, and degradation of structures and artifacts, and to how these objects themselves produce social relationships and meaning. Justin Wilford (Reference Wilford2008), for instance, describes how New Orleans residents and American politicians came to experience and define “natural disaster” through the rubble of homes destroyed during Hurricane Katrina. In a somewhat similar way, Brian Larkin (Reference Larkin2004) emphasizes the way in which “modernity” is made tangible in Kano, Nigeria, through pirated videos. Economic uncertainty, techniques of replication, and the realities of technological breakdown in Nigeria mean that video images are distorted and sound quality is poor. These degraded images are not anomalies but are instead the general rule in Nigeria. It is therefore not in spite of the material state of these films but through them that “modernity” is lived and concretized. It is not only the content of the film but also the form itself that gives shape to African conceptions of the modern.

I draw on these theories to argue that it is through the city's half-built houses that many Dakarois encounter transnational migration and its possibilities. In doing so, I seek to complicate straightforward inquiries of transnational migration and belonging that often focus solely on the relationships migrants and their families have with both “home” and “away.” Transnational migration is instead a much more complex process, one that involves unexpected actors and mediators, both human and object. Dakarois constantly spoke to me of the city as a place that was under construction by those living in the diaspora. The building of houses by migrants was not considered an exception but rather the norm, and in every Dakar neighborhood one found at least one building project initiated by migrant-earned capital. I suggest here that these homes and processes, sounds and sights, are so pervasive that they are actively transforming notions of who can belong to the city and how. The artifacts and activities I describe here are so deeply valued that scores of clandestine migrants risk their lives and fortunes to reach the shores of “Europe,” where they, too, might save enough to build a home in Dakar. Grappling with what it means to live surrounded by houses under construction helps us to better contextualize and understand Senegal's current migration “crisis.” When we turn the migrant-belonging paradigm inside out what is revealed is a layered patterning of belonging that is contingent on one's relationship to and involvement in transnational migration processes. Like the rising and crumbling walls of the house, the insides and outsides of belonging in Dakar are constantly blurred, transgressed, eroded, and constructed. The city's unfinished houses are often public territories whose insides are exposed not only to sun and rain but also to public scrutiny and accusations of illicit behavior. These half-built houses generate intense anxiety and fascination among Dakarois.

Atouma, whose family home in SICAP Liberté III was still far from completion, was excited to take me on a tour of this emergent structure, but his most urgent desire was to talk with me about his own inability to migrate. He told me that he was the only son that had not migrated, had not married, and was not constructing a house. Though he “feared the seas” and did not want to board a pirogue, he also was emphatic that he would soon have to leave Dakar: “How much longer can I live in the house that my brothers are building?” His pleading question, I suggest, expresses configurations of migrant belonging turned inside out—it is not the house but the act of building that is socially valued, and, from the vantage point of Dakar, it is not the migrant but the non-migrant whose presence is dubious.

Although Atouma was worried about his inability to migrate and build his own home, his brothers' construction nonetheless made his continued presence in the city more certain. His situation thus stands in stark contrast to the circumstances of others whose sense of belonging was far more uncertain. This assertion is exemplified by the story of Cheikh, a middle-aged Serer man from the Fatick region of Senegal who had come to work as a gardien in Yoff during the time I lived and worked there. As I have explained, housing construction had brought many Senegalese villagers to Dakar seeking opportunities as custodians, guards, laborers, and squatters. Prior to his move to Dakar, Cheikh had never left Fatick, and his day-to-day life was still confined to a small corner of the city. He was responsible for looking after a sprawling property that was rented to expatriates by a Senegalese woman living in Paris. He lived in the garage of the villa, slept on a small second-hand sofa, and cooked rice on a portable gas stove. He made the equivalent of U.S.$100 each month. As the property's only gardien, he was expected to remain on site around the clock, seven days a week. This did not, however, prevent Cheikh from establishing an impressive social network that spanned the neighborhood. A self-described “entrepreneur,” Cheikh found innovative ways to supplement his small salary by running errands, bartering and selling his possessions, and, as he often described it, “meeting the right people.” In the seven months that I knew him he quickly learned conversational French, a strategic move that, he explained, would open up other opportunities. His professed goal was to find work as a chauffeur for a wealthy embassy worker or expatriate businessman in the neighborhood. He was certain that once he gained the respect and trust of his foreign employer he would be invited to work in Europe or the United States. Soon after, he would begin to build two houses: one in Fatick for his ailing mother, and one in Dakar like the one in which he worked.

Cheikh's story was similar to those of many rural Senegalese who came to Dakar to work in sectors related to housing construction. These newcomers were able to dwell in Dakar and to engage in future-oriented economic and social activities because of the ongoing nature of housing construction in the city. The uncertainty of remittance flows, for instance, produced a plethora of unfinished houses, which were then inhabited by rural Senegalese seeking access to the city's resources and markets. At the same time, these newcomers found that their presence in Dakar was always partial, contingent, and temporary. Shifts in housing construction or remittance flows, for instance, could threaten their continued stay. In contrast, as Cheikh and others explained, building a house could assure long-term presence in the city.

This act of building in Dakar is a gendered process that sometimes places women in a precarious position. Women are less likely to build and less likely to migrate. Although women do engage in these practices—as is evidenced by the diasporic Senegalese woman who employed Cheikh—they are usually considered the minority. Even when their husbands build, capital for construction projects in Dakar is most often sent to brothers or business associates, and these men are responsible for decision-making and site visits during the migrant's absence. In popular opinion, houses are built “for” women by men, and many villas bear names like “Keur Astou” (The House of Astou), signaling the gendered nature of the spaces built. Buggenhagen's useful piece (2004) examines how women extend networks and generate credit for trading activities through the conspicuous consumption practices enabled by transnational migration. But the prestige created by building itself is often available to women in Dakar only indirectly; the home and its continuity are contingent on the success and accumulated wealth of men living abroad.

Fatou, a close friend, lived in Dakar in an étage constructed by her husband, a successful bank manager living and working in Paris. She came from a relatively wealthy and well-educated family, and she herself made a good income as an accountant in the city. When her marriage ended abruptly in divorce, however, Fatou had to leave the house and moved in with her sister and brother-in-law. A bitter dispute over the étage and its contents erupted between Fatou and her husband's mother, who was charged with taking care of the situation in his absence. Fatou ended up leaving her husband's house with only what she had arrived with, along with the coveted microwave, purchased in France. Like Atouma, Fatou's living situation was contingent on her relationship with her husband, regardless of her own financial security and the economic position of her family. About six months after her divorce Fatou called to tell me that she had remarried; her new husband worked at the American Embassy, and he was eager to speak with me about his prospects for moving to the United States.

While excluded, in some respects, from full belonging through the construction of a house, the city residents whom I have described nonetheless play an integral role in the production and policing of this form of belonging. Who was building, how quickly, and with what money and materials was a popular topic of discussion. City residents saw a direct correlation between the rate at which one built and the type and viscosity of the flow. If a project neared completion unusually quickly, neighbors would whisper about the migrant's activities in Europe. Was he involved in selling drugs or some other illicit activity? A close friend, who had recently returned from Europe to live in the house he had built, often made reference to these emergent houses to demonstrate his point that many migrants were involved in illicit activities abroad. “Even if they are eating only rice in Paris,” he once said, “there is no way that they could build such a grand villa so quickly.” At the same time, if the construction of a house took an inordinate amount of time, the builder was susceptible to scathing critique of his spending habits abroad. Accusations of “squandering” (gaspillage) of money on women, alcohol, or personal consumption were likely if a house sat for many years without a new layer of bricks. While many residents wanted to migrate for the explicit purpose of building a house, they nonetheless blamed these houses for the risks taken by hopeful migrants.

At the same time that non-migrants describe themselves as excluded from urban (and thus diasporic) belonging, they also continually carve out a space for future presence. Migrant building practices, in fact, often open up unexpected and paradoxical opportunities for rural Senegalese to inhabit the city and to access its resources and markets, as was the case for Cheikh. These newcomers often explained that they had come to work and save money before heading abroad. Even men with family members abroad insisted that they would join their brothers or friends in Europe and would build a house for their families. Many women, too, spoke of their preference for finding a husband who worked abroad, since they would gain economic credit and social prestige through their husbands' projects and expenditures. Other women spoke of seeking educational opportunities or employment abroad, as female friends had done. Regardless of their financial circumstances or contingent presence in the city, my male and female interlocutors often imagined a different future, one that would give them access to spaces and resources not available at present. Seen from this perspective, urban belonging is necessarily a process, an ongoing, shifting, and complex relationship to transnational mobilities of labor and capital.

CONCLUSION

The emergent houses of absent migrants that I have described are not exceptional or aberrant. In so-called “sending” communities throughout the world, transnational migrants and their families engage in construction practices that shape the contours of communities and that stake claim to home. The ethnographic details presented here underscore the need to analytically separate “house” and “home,” to consider the role that building, rather than just dwelling, plays in the construction of belonging as a process, as always on the horizon. Economic uncertainty and the irregular rhythm and volume of transfers sent from the diaspora mean many houses linger in various stages of completion for many years. The aesthetics of these houses—where insides and outsides are poorly defined, where walls seem to fall as they climb—produce very particular ideas about how the diaspora and “home” are articulated. These ongoing construction projects index ongoing relationships with the diaspora and make future claims on space, participation, and effective presence. They also articulate with larger state-sanctioned rubrics for development, which explicitly link economic possibility to the act of building. The ubiquity of these migrant-built structures—intended for future occupation or as investment properties—produces Dakar as a city of exclusion, where only those absent can truly belong through housing construction. These not-yet houses also demonstrate that belonging is a process that is rooted in both present circumstances and future possibilities, for at the same time that non-migrants see themselves as excluded from full belonging in Dakar, they constantly foreground their future hopes to migrate and to build.

These not-yet houses and the broader economic and social landscape of which they are a part challenge scholars to reconsider the link between transnational migration and localized belonging. At the urging of international organizations like the World Bank and the United Nations, states and other governing institutions are increasingly reconsidering migration not as a tool for propping up households at “home” on a day-to-day basis, but as a strategy for transforming national futures (see Hernandez and Coutin Reference Hernandez and Coutin2006; DeHart Reference DeHart2004). I suggest that this reorientation of state and public priorities in places like Senegal has profound implications for those who do not and cannot migrate, as new hierarchies and ideas about wealth and participation emerge. Our analyses of transnational migration must therefore seek to grapple with the complex and often contradictory effects of neoliberal regulation, and we must push ourselves to devise new scholarly lenses that bring into focus emergent exclusions and connections.