The paper examines mobilization to reduce the deepest inequalities in the two largest democracies: along racial lines in the United States and caste lines in India. I compare how the groups at the bottom of these ethnic hierarchies, African Americans and India's formerly untouchable castes (called Dalits or “broken people”), mobilized to attain full citizenship, including enfranchisement and political representation, civil rights including freedom from bondage, and social rights such as entitlements to equal education, employment, income, and social security. I compare these mobilizations at their peaks, between the 1940s and 1970s, and also consider their effects on political representation and policy benefits.

Comparison of race relations in the United States and caste relations in India, and specifically these two mobilization projects sheds new light on both cases due to similarities in their historical backgrounds and crucial differences in group experiences since the 1940s. There are greater similarities between these two cases than between race relations in the United States and other former European settler colonies with regard to socioeconomic relations, group boundaries, demographic patterns, enfranchisement timing, and post-enfranchisement regimes and experiences.

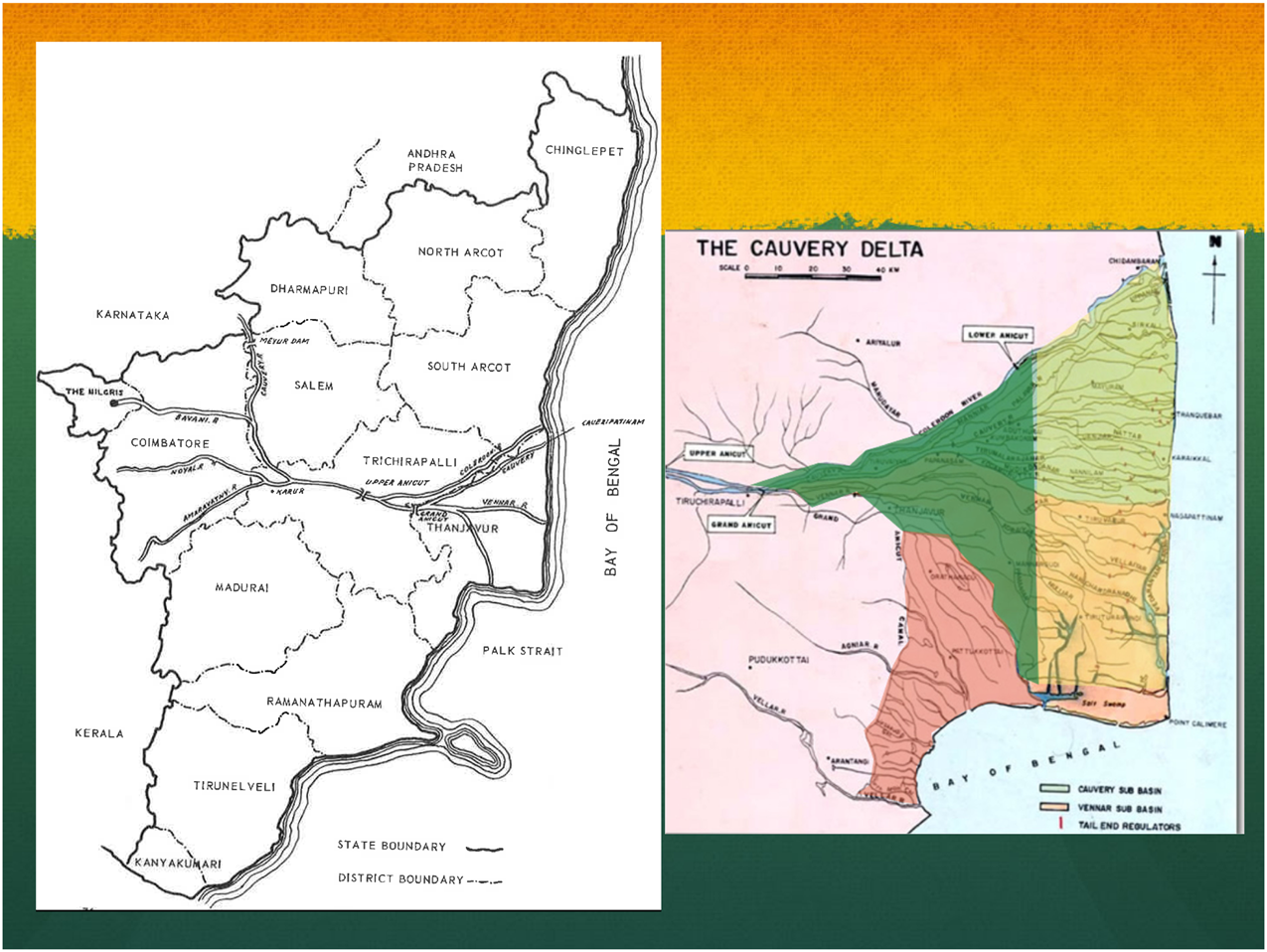

After outlining some national trends, I will focus on two specific regions—the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta in the southern United States and the Kaveri Delta (Kaveri) in Tamil Nadu (TN), southern India—where certain key group circumstances were similar until the mid-twentieth century: their population shares were high, group relations were particularly unequal, and attempts at group advancement faced greater resistance. Since group-formation was tied to coercive agricultural labor extraction, group inequalities and subordinate group concentrations were greatest in large-scale agricultural zones. This was particularly so in the Black Belt around the lower Mississippi, which had the most extensive system of plantation slavery and then other forms of agrarian bondage, and in India's major river deltas. Throughout the Jim Crow years, blacks had least access to economic independence, white arenas, political parties, and state institutions around the Mississippi Delta, where they also encountered greatest violence. Even today, more whites in the Black Belt are opposed to black rights and mobility than in any other region (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018). For Dalits, until decolonization Kaveri was among the regions where they suffered the greatest economic, social, and ritual constraints, violence, and indignities. The subordinate groups in both of these areas mobilized extensively starting in the mid-twentieth century.

Despite these similarities, African American and Dalit mobilization patterns differed both at their peak and thereafter. African American mobilization in Mississippi did not intensify until rather late, in the mid-1960s, but at that point it became especially strong. Dalit mobilization accelerated relatively early in Kaveri, in the late 1940s. Dalits built much stronger interethnic alliances in Kaveri than did African Americans in Mississippi, but Dalit mobilization remained more regionally restricted.

Social groups tend to be more successful in their mobilization if they tap already existing group cohesion and effectively exploit emergent opportunities. Four factors help disadvantaged groups gain representation and policy benefits: group solidarity, favorable alliances, bargaining power, and polity insiders’ accommodative inclinations. Discourses about the political community and patterns of group classification and stratification especially influence whether these conditions favor ethnic minorities. The key group had stronger community institutions in Mississippi, which different political organizations tapped to promote greater cross-regional ethnic solidarity by adopting specific strategies suited to distinct locales. But in Kaveri mobilization was more sustained, and mobilizers were able to build stronger interethnic alliances there since Indian caste relations are less polarized than American race relations, Kaveri's mobilizers had more multiethnic visions and leadership, and repression declined sooner.

Group projects diverged in these regions beginning in the 1970s. In Mississippi, high mobilization did not enable commensurate political representation for two decades or significant policy benefits even thereafter. The black representation gap (between group share in population and political offices held) and black poverty remained highest there and relative black wellbeing lowest (Timberlake et al. Reference Timberlake, Williams, Dill and Tukufu1992; Burd-Sharps, Lewis, and Martins Reference Burd-Sharps, Lewis and Martins2009). In Kaveri, by contrast, high mobilization transformed Dalit circumstances from particularly backward to relatively advanced. Bondage ended in the 1950s, earlier than in neighboring areas, while agricultural wages, sharecroppers’ and tenant-farmers’ returns, and agrarian contractual duration became highest. Dalit local government representation increased faster than elsewhere in TN, and the already entrenched Dalit power deterred the anti-Dalit violence that erupted elsewhere in TN from the 1990s onward.

Kaveri Delta Dalits gained greater representation and benefits than did black Mississippians, even though they mobilized intensively in a smaller region. This was because they built better alliances, parties competed more for their support, and parties and movements mobilized more across caste than they did across U.S. racial lines, and therefore policymakers accommodated them more readily. Nationalist discourses and classification patterns helped Dalits form more favorable alliances and make greater policy gains than African Americans did across the two countries, and this was especially so where ethnic equality had been high until recently.

Scholars have systematically explored neither the striking similarities nor the important differences in Dalit and African American experiences. Doing so highlights the circumstances under which deeply disadvantaged ethnic minorities mobilize successfully. Addressing why the mobilization in Kaveri won more long-term gains in power, representation, and policy benefits than that in Mississippi elucidates conditions under which such groups access various dimensions of citizenship. I examine why Dalits mobilized longer and gained more even though African Americans’ community institutions were stronger, and they mobilized across a larger region.

Section I compares our cases to several other instances of durable group inequalities. It explains how official and popular community discourses and forms of classification, as well as stratification patterns, influence mobilizers’ and polity insiders’ responses to socioeconomic contexts and political opportunities. It compares how these factors influenced Dalit and African American mobilization, enfranchisement, representation, alliances, and party incorporation nationally. Section II outlines social relations in the case regions up until the mid-twentieth century. Section III compares the regional mobilizations, while section IV briefly examines respective gains in representation and policy benefits. The Conclusion highlights how group solidarity, alliances, party strategies, party competition, polity insider-mobilizer interactions, and the discourses framing these phenomena influenced citizenship.

I. SITUATING THE COMPARISON OF THE TWO COUNTRIES

The paper provides a paired comparison of two phenomena (African American and Dalit mobilization) and two regions. Although they are importantly comparable, the two regions have never been compared, and the two phenomena have not been systematically compared. The larger study employs a multilevel, matched transnational comparison of subnational and national experiences based on multi-sited ethnography, interviews, archival research, electoral and socioeconomic analyses, and sample surveying. I will explain how different regional outcomes eventuated despite initial similarities based on regional circumstances, national contexts, and regional-national interactions, and suggest ways of understanding particular national differences and intranational variations, combining the depth of single-case research with the analytical advantages comparison provides.Footnote 1 The paper employs data from archival research, interviews, and ethnography to explain mobilization, indicates electoral, socioeconomic, and policy trends, and draws inferences about the conditions that enable citizenship extension.

In both cases, the majority of subordinate group members endured agrarian bondage—forms of slavery or other legal and customary constraints on labor supply that shaped relationships of stark inequality between landowners and agrarian workers, sharecroppers, and insecure tenant-farmers. Also in both, group boundaries are relatively sharp and the subordinate groups’ population shares are similar: in India between 16.6 percent and 20.6 percent (the latter if we, unlike state authorities, include Christians and Muslims), and in the United States between 12.6 percent (black only) and 13.6 percent (black and another racial group). Majorities of both key groups were permanently enfranchised at about the same time, through India's first postcolonial elections in 1952 and the United States Voting Rights Act of 1965. This is also about when both groups gained several civil rights. Both advanced less consistently after enfranchisement than did lower classes that faced no ethnic prejudices, and more than a half-century after enfranchisement both remain deeply disadvantaged despite inhabiting largely stable democracies. Relative to these two cases, we find greater differences in these key factors between the United States and other former settler colonies with which the United States is often compared regarding race relations: bondage was far less extensive in South Africa, group boundaries were more porous in Brazil, groups of partly or entirely African ancestry were the majority in Brazil and South Africa, formal equal citizenship was extended far earlier in Brazil and much later in South Africa, and democracy was less enduring in Brazil and emerged more recently in South Africa.

Scholarly comparisons of the African American and Dalit cases have been deficient. The “caste school of race relations” (Warner Reference Warner1936; Powdermaker Reference Powdermaker1939; Davis, Gardner, and Gardner Reference Davis, Gardner and Gardner1941) and certain critics (Myrdal Reference Myrdal1944; Cox Reference Cox1948; Berreman Reference Berreman1979) analogized the two groups. Some Dalit intellectuals emphasized parallels between the group projects, and some scholars compared preferential policies favoring them (Weisskopf Reference Weisskopf2004; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2003). Others have claimed there were reciprocal influences, although while Dalits borrowed from African Americans, African Americans drew mainly from Indian elites (Pandey Reference Pandey2013; Slate Reference Slate2012; Natrajan and Greenough Reference Natrajan and Greenough2009; Thorat and Umakant Reference Thorat and Umakant2004).

Pandey juxtaposed, without systematically comparing, African American and Dalit experiences. His framing claims were inaccurate. He explored aspects of “vernacular prejudice” informing local discrimination based on group stigmatization, which he contrasted with “universal prejudice,” associated overtly with post-Enlightenment rationality, law, and the state, and tacitly with dominant groups (2013: 1–2). This obscured how, during modern state formation, stigmatization shaped generalized socio-legal barriers, some of which continue to constrain the subordinate groups. Associating the post-enfranchisement American state solely with colorblind racism expressed through reduced redistribution toward racialized groups, Pandey failed to conceptualize persistent, state-driven color-conscious racism, for example through racialized incarceration and felon disfranchisement. More crucially, he underestimated group cultural autonomy and misunderstood key group differences. He claimed, “Dalits have remained trapped in a more intractable position than African Americans because of a poorer economy and slower economic growth in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and more restricted opportunities for escape from the stranglehold of caste, which is countrywide” (ibid.: 16). Per capita decadal GDP has grown faster in India since 1980, and growth has uncertain distributive implications. Besides, caste relations vary more cross-regionally than do race relations, and status changes more gradually across the caste than across the American racial spectrum. Consequently, Dalits have been able to build more favorable alliances and parties have marginalized them less, especially over the past three decades. Greater political marginalization and stronger community institutions, however, enabled greater African American solidarity. In sum, Pandey's reflections do not help us compare the Dalit and African American projects.

Understandings of American social structure as racial capitalist highlight links between unequal class structures and ascriptive stratification, and they could be extended to features of South Asian caste. They place under the capitalist rubric too many forms of distribution of property, as well as work obligations, life chances, and rights, and thereby obscure the different ways in which ascriptive stratification and class inequality interact. Indeed, Beckert states that “cotton capitalism” “rest[ed] … on a great variety of labor regimes,” including chattel slavery, sharecropping, insecure tenant-farming, and free labor (Reference Beckert2014: 308, passim). Applying such a view to Mississippi, Woods (Reference Woods1998) underscored that planters retained much authority and limited black lives even while agrarian bondage declined, cropping diversified, low-wage industrialization with racialized labor control grew along with federal spending-driven capital-intensive industrialization, and black mobilization, enfranchisement, and representation increased. He saw autonomous black “working-class” initiatives (including those of tenant-farmers, sharecroppers, leased convicts, and wage labor) alone as sources of effective change, and did not address how they interacted with white elite projects to change Mississippian race relations. Understandings that caste capitalism drove Indian social change, similarly, would not capture the different ways in which economic activities, elite initiatives, mass politics, and Dalit circumstances changed interactively around India, or the consequences party-driven Dalit-centered multi-caste mobilization had in Kaveri. Such theories fail to explain the different political initiatives and contending alliances that emerged amid deep ascriptive stratification, or why some redistributive projects were more successful than others.Footnote 2

Citizenship Extension, Mobilization, Democratization

Cases where class structures and hierarchized ethnic identifications were formed in close mutual association elude theories of citizenship, democratization, and inequality that are based mainly on working-class experiences and class-state relations. T. H. Marshall (Reference Marshall1977) inadequately attended to the determinants of membership in the political community, which is crucial for citizenship. Men of dominant ethno-racial groups were included earlier and more fully than were women and people of marginalized ethnicities, such as formerly enslaved groups, indigenes of settler colonies, Romany and Sinti, many mountain- and forest-dwelling Asians and Africans, and South Asian Dalits and tribes. Predominant discourses initially justified the latter groups’ exclusion from citizenship and impeded their subsequent gains (Somers Reference Somers2008; Smith Reference Smith1997; Kessler-Harris Reference Kessler-Harris2001).

Barrington Moore's (Reference Moore1966) view that “labor-repressive” agriculture deterred democratization does not accord with India's democratic consolidation despite persistent caste bondage, although the more nuanced observation that such oppressive socio-economic relations reduce the quality of democracy is sustainable. Discourses of unequal group capacity and political community membership influenced the perceived requirements of surplus-generation and institution-building more than Charles Tilly (Reference Tilly1998) recognized. Such discourses induced southern American planters to oppose black rights even after agrarian mechanization; made “New South” entrepreneurs until the 1960s skeptical that workforce desegregation would benefit them and limited black recruitment to better-paid positions thereafter; motivated India's commercializing landlords to limit Dalit rights; led many Indian administrators to consider Dalits incapable of participating in the upper bureaucracy; and induced these elites to offer poorer dominant group members better arrangements so as to limit the formation of cross-ethnic, lower-class alliances (Wright Reference Wright2013; Schulman Reference Schulman1994; Jacoway and Colburn Reference Jacoway and Colburn1982; Mendelsohn and Vicziany Reference Mendelsohn and Vicziany1998).

African Americans and Dalits initially mobilized significantly along ethnic lines because associations representing the classes to which they largely belonged—agrarian workers, sharecroppers, tenant-farmers, small landholders, and industrial and urban workers—inadequately promoted their interests. Many trade unions initially refused them admission and resisted giving them equal pay and workforce status. Many agricultural organizations did not reduce their unpaid labor obligations or obtain them higher wages or cheaper inputs (Arnesen Reference Arnesen2007; Frymer Reference Frymer2008; Viswanath Reference Viswanath2014a). These groups initially enjoyed limited influence in multiethnic movements and parties. The Democratic Party drew non-southern African Americans yet represented them inadequately, as the Congress Party (Congress) did with Dalits (Frymer Reference Frymer1999; Jaffrelot Reference Jaffrelot2002). Black Americans and Dalits had limited policy influence due to their minority status and the weak cross-ethnic alliances available to them, and as a result the social rights granted by the New Deal and early postcolonial Indian development did not fully reach them (Lieberman Reference Lieberman1998; Mendelsohn and Vicziany Reference Mendelsohn and Vicziany1998; Harriss-White Reference Harriss-White2003: 176–99).

Due to these hard constraints, African Americans and Dalits made major gains only in special circumstances. They therefore mobilized for and gained various civil, political, and social rights nearly simultaneously, not sequentially as Marshall suggested. African American leaders such as M. L. King, Jr. resisted federal pressures to target voter registration while postponing accessing public spaces and white institutions, and soon after passage of the Civil Rights Acts and the Voting Rights Act, they pressed for poverty alleviation and desegregation. Dalit leaders like B. R. Ambedkar resisted elite nationalist compromises on accessing temples and common property and lobbied, unsuccessfully, for separate Dalit electorates. Such initiatives gained Dalits, upon decolonization, voting rights, quotas in education, government jobs and representation, anti-poverty measures, and laws against untouchability, forced labor, and discrimination. They similarly gained African Americans in the 1960s the franchise, greater civil rights, affirmative action policies, desegregation measures, and Great Society programs.

African American and Dalit influence over civil society and parties remained limited, which left their entitlements vulnerable. They diminished in the United States with regressions in educational desegregation and in preferences regarding public provision, education, and employment. Likewise, for Dalits, Indian economic liberalization reduced wage goods subsidies and the effects of government job preferences.

Discourses of Community, Forms of Classification, and Stratification

Discourses about the political community shape both official and popular social classification, and thereby influence institutional norms, interest-formation, mobilizations, and alliances. Dominant narratives characterize the norms, capacities, and national memberships of formerly bonded groups in ways that can impede their mobilization and limit their alliances and the degree to which political elites prioritize their interests. Alternative discourses articulated in partial autonomy shape subaltern agendas. Such competing narratives interact with social changes and political opportunity to form citizenship projects.

Specific differences between the predominant American and Indian political discourses influenced citizenship extension. Although African Americans and Dalits were comparably marginal in colonial society, the nation was imagined as including Dalits earlier than African Americans, especially relative to sovereign state-formation. Inegalitarian racial discourses led federal authorities to support black enslavement and then Jim Crow restrictions and kept most white Southern political elites from even formally accepting African American inclusion until the 1970s, while still marginalizing them covertly. By contrast, prominent Indian nationalists signaled Dalit inclusion after the First World War to broaden anti-colonial mobilization, although Mohandas Gandhi resisted autonomous Dalit mobilization, opposed Dalit electorates, and advocated paternalist uplift (Jayal Reference Jayal2013; Jaffrelot Reference Jaffrelot2002; Gandhi Reference Gandhi1954). Thus, Dalits were politically included, clearly albeit unequally, two decades before sovereignty, while African American inclusion remained precarious two centuries after sovereignty.

Moreover, official and popular classifications differed. Race was the primary official and popular identity axis in the United States, often prioritized over ethnicity, religion, and sect. In India, religion and language were as salient as caste, which they crosscut. The relative status of many of the thousands of jatis (largely endogamous castes) was disputed, and caste mobility existed for centuries. This contrasts with the primarily bipolar racial classification and more restricted mobility avenues in the United States (Bayly Reference Bayly1999; Dirks Reference Dirks2001; Smith Reference Smith1997).

The boundaries between Dalits and lower-middle castes were context-specific. In official classifications, dating from the nineteenth century, they were blurred and regionally diverse, until national scheduled caste quotas were introduced in 1935. Likewise, in popular perceptions until the early twentieth century, when socioeconomic mobility among some lower-middle castes and Dalit mobilization and preferences sharpened the boundaries, while inclusive policies and cross-caste alliances blurred them. Complex caste stratification, language differences between similarly ranked castes, regional cross-caste cultural similarities, and some shared Dalit and lower-middle-caste circumstances meant there was less dominant caste and Dalit distinctiveness and cohesion than typified American white-black relations. These factors influenced national differences in group mobilization, enfranchisement, representation, alliances, and party incorporation.

Mobilization

The two groups were marginalized in ways that enabled different types of solidarity. Bipolar racialization promoted African American solidarity but distanced blacks from other groups; caste stratification created barriers between Dalit jatis but enabled links between Dalits and some lower-middle castes. How far solidarity leads to mobilization depends on whether a group has common goals and resources on which to base mobilization, and how much other groups impede or contain them. Dominant groups constrained both Dalit and African American mobilization, but blacks had space to develop autonomous churches, schools, and self-government organizations throughout the slavery and Jim Crow epochs. While dependence and repression limited African American mobilization on these bases, imaginative strategies helped Garveyism and the Civil Rights Movement (CRM) acquire a near-national scale, although they grew later in parts of the Deep South where they faced more constraints (Hahn Reference Hahn2003; McAdam Reference McAdam1999).

Language and jati differences limited Dalit solidarity and the scale of Dalit mobilization far more.Footnote 3 They mobilized extensively, beginning in the late nineteenth century, only where they enjoyed early socioeconomic mobility—in Maharashtra and Punjab, and somewhat less in Kerala and Bengal. Moreover, Dalit movements were led by and gained support mainly among relatively advanced jatis—Mahars in Maharashtra; Chamars/Jatavs in Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh; Pulayar and Parayar in Kerala; and Rajbanshis and Namasudras in Bengal. The most successful Dalit-led parties, the Scheduled Castes’ Federation (SCF)/Republican Party of India (RPI) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), built consistent support only among Mahars and Chamars, ever polling over 10 percent only in Maharashtra (RPI), Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab, and Delhi (BSP). Pigment and class differences limited African American mobilization less especially at its peak and in the Deep South.

Alliances

Due to the primacy and bipolarity of the U.S. racial order, the greater cohesion of American races, and the more exclusionary nature of American civic discourse, it was harder for African Americans to mobilize with other groups. By contrast, Dalit-focused movements (and some lower-middle-caste movements) articulated porously bordered notions such as bahujan samaj (popular community) to ally advantageously with lower-middle castes and the predominantly middle- or lower-caste Muslims. Integrationist African American organizations upheld similarly inclusive visions, though they gained little support from white Protestants. They often felt pressed to support parties and unions that subordinated black interests, but sometimes formed beneficial alliances with white Catholics, Latinos, Asians, and Jews (Frymer Reference Frymer1999; Reference Frymer2008). The latter alliances usually assembled groups that mobilized along distinct ethnic lines. Dalits, on the other hand, more often participated in mobilizations that formed cross-caste subcultures.

Layered caste stratification did not ensure Dalits beneficial alliances everywhere. How much support Dalit-focused movements gained depended on their discourses and their leaders’ caste identities. For instance, when Ambedkar formed the Independent Labor Party he gained little support beyond his Mahar jati, which later led him to adopt the caste-specific Scheduled Castes’ Federation name. The Bahujan Samaj Party's bahujan vision built broader support, but it remained consistent only among the leaders’ Chamar/Jatav jati, the base of its predecessor civil society organizations. Communists and socialists better reconciled support among Dalits and other lower strata since they consistently pursued cross-caste class projects and had crucial non-Dalit leaders, for instance in Kaveri. In the United States, racial stratification was more multi-layered and cross-racial alliances were more effective in states such as California, Texas, and Oklahoma, where there were large Latino/indigenous populations marginalized in some ways similar to African Americans.

Enfranchisement and Representation

Polity insiders resisted black voting and representation, often fiercely. After Reconstruction, most African Americans lost the vote, which was reinstated only when intense white repression made it clear that black mobilization could not ensure voter registration in the Black Belt based on pre-1965 voting laws. The major Indian nationalists, in contrast, all supported universal franchise starting in the 1920s, accepted Dalit electoral districts in 1932, and enfranchised Dalits after independence when Dalit mobilization was low. After black enfranchisement, the United States saw more vote dilution through multi-member districting, at-large voting, and gerrymandering, and disfranchisement through felon disqualification and stringent voter identification laws (Davidson Reference Davidson1984; Pettit Reference Pettit2012; Pedriana and Stryker Reference Pedriana and Stryker2017). As Dalit participation increased beginning in the 1980s, in 1996, authorities extended to local assemblies the Dalit representative quotas, which they set at the levels of the state-specific Dalit population share. Moreover, they raised the Dalit quota in the lower parliamentary house marginally to 15.5 percent in 2009, a little below the group's official national population share of 16.6 percent.

Party Incorporation

Other groups opposed African Americans’ demands far more than they impeded Dalit agendas. Mobilization against Dalit preferences was limited, while most white Americans opposed the adoption of racial preferences. Frymer (Reference Frymer1999) demonstrated that such white opinion enabled one party (the Republicans until the New Deal, and the Democrats from the late 1970s onward) to virtually monopolize the black vote, and such limited party competition for black votes meant that neither party had much incentive to advance black interests extensively. There was no similar electoral capture of Dalits in India; other parties competed for Dalit support even in Congress's heyday, such as the RPI in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh, the communists in Kerala and Bengal, the Dravidianists in TN, and the socialists in Bihar. Starting in the 1980s, the Dalit vote dispersed still further and the resulting party competition pressed politicians to address Dalit interests. In the United States, political party disengagement channeled African American mobilization mainly through black-led civil society organizations, especially in the South before the Voting Rights Act. By contrast, parties were important agents of Dalit mobilization. As a result of all this, from the 1980s onward Dalits wielded greater policy influence than did African Americans.

II. Case Study RegionsFootnote 4

From the early nineteenth century, Mississippi had large plantations, initially cultivated mainly by slaves and later by otherwise bonded sharecroppers and tenant-farmers. From the mid-nineteenth century, it had the country's greatest concentration of blacks, who made up 58.5 percent of its population in 1900 and the majority until 1930. In the Mississippi Delta, blacks were 74.0 percent of the population in 1930 and 53.8 percent in 2010 (McMillen Reference McMillen1989: 155; United States Bureau of the Census, 1930 and 2010 figures). During the Jim Crow period, African Americans experienced the most stringent restrictions, repression, and poverty, and held the least land and fewest professional jobs in Mississippi.

Kaveri was among the regions with greatest Dalit concentration, agrarian bondage, and caste inequalities (Kumar Reference Kumar1965; van Schendel Reference van Schendel1991: 45–51, 81–85, 92–96, 116–30, 143–55). Dalits are 30.8 percent of Kaveri's population and 20.0 percent of TN's, and these figures have changed little since the early-twentieth century. Group shares in the two deltas’ populations reflect their relative territorial concentration. Over 90 percent of blacks lived in the South until the First World War, 55 percent still did so in 2010, and blacks comprise the majorities in 105 of the 3,143 counties in the United States. Dalits were never so territorially concentrated and are the majority in only one of India's 626 districts. The largest Dalit jatis of TN and Kaveri, Parayar and Pallar, account for 12.6 percent and 3.3 percent of the state's population, and 21.1 percent and 8.3 percent of Kaveri's, respectively. The middle castes previously experienced relatively high restrictions in Kaveri, and had shared occupations with Dalits as agrarian laborers, sharecroppers, and tenants, and this enabled Dalit-middle-caste alliances. Unlike Dalits, the middle castes were not slaves or pannaiyaatkal (hereditary bonded labor). Collective landed elite control over slave castes and land was converted into individual property in the nineteenth century, slavery was officially abolished in 1843, and there were shifts from sharecropping to renting, but these changes did little to reduce lordly control or improve Dalit status until the century's end (Gough Reference Gough1989; Viswanath Reference Viswanath2014b).

Agrarian and ethnic relations changed from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries in both regions. Colonial officials did not reduce taxes as much as demand declined for Kaveri's main crop, rice, and this strained state-lord relations. New middle-caste landed groups emerged, labor contracts became shorter-term, and landlord clientelism weakened. Many agrarian workers, peasants, and tenants, about half of them Dalit, migrated to other British colonies. Some émigrés returned and acquired minor property, while others’ remittances improved their families’ circumstances. While away, migrants experienced less pervasive restrictions and acquired resources, and this helped them contest caste dominance upon returning home. Starting in the late nineteenth century, some middle castes and lesser numbers of Dalits gained education. Landlords tried to restore their dominance through debt bondage, re-appropriating homestead land, and repression, which starting in the 1910s led to increasing conflict (Menon Reference Menon1983; Baker Reference Baker1984; Basu Reference Basu2011: 111–64).

In Mississippi, the demand for labor declined in the 1930s due to a drop in the production of the state's major crop, cotton, and then an acceleration of agrarian mechanization starting in the late 1950s (Cobb Reference Cobb1992: 254–66; Schulman Reference Schulman1994: 4–5, 20, 103). In the early twentieth century the state had begun to urbanize, but at the slowest rate in the United States. Although black education rates improved, with 25 percent of school-age blacks attending (but only 7 percent finishing) secondary school by 1950, levels of black education remained lower in Mississippi than in other states. Black dependence declined more slowly there than in any other state. Black urbanization (13 percent in 1930) and employment in other than agriculture and domestic and personal services (16.7 percent in 1940) remained lowest, while concentration in planter-controlled occupations stayed highest—blacks made up 65 percent of landless agrarian workers in 1930, and in 1945, 58 percent of black farmers were sharecroppers (Mickey Reference Mickey2014: 90, 411; Bolton Reference Bolton2005). Nevertheless, whites, both landed elites and the poor, only began to resist black autonomy more sharply from the 1950s (McMillen Reference McMillen1989: 72–110, 154–94). Migration to Midwestern and Northeastern industrial centers forged links between Mississippi blacks and political currents in the more autonomous southern black diaspora. The migrations also left blacks a minority in Mississippi by 1940, and by 2010 they made up just 37.6 percent of the population. Their electoral influence was reduced accordingly.

Socio-Ecological Zones

Within both deltas, mobilization and representation patterns varied by socio-ecological zone. Simplifying McMillen's (Reference McMillen1989) typology for Mississippi, I distinguish (a) the Delta (in the northwest), which had the most fertile soil, extensive irrigation, largest plantations, greatest bondage, and highest black population (currently 53.8 percent); (b) the Lowlands and Brown Loam and Loess Hills (in the southwest), where the black population (47.8 percent) and bondage were lower; and (c) the Hills (in the more ecologically-diverse east), which had less land concentration, more small white farmers, more propertied blacks by the mid-twentieth century, and the lowest black population (29.7 percent). For Kaveri, I simplify Béteille's (Reference Béteille1974: 142–70) and Bouton's (Reference Bouton1985: 102–35) typologies to distinguish: (a) the Coastal Old Delta, with unreliable canal irrigation, the greatest land concentration, more middle-caste landlords, and the most Dalits (44.3 percent today) and the most bonded Dalit workers until the mid-twentieth century; (b) the Central Old Delta with abundant canal irrigation, particularly fertile land, upper castes and religious institutions controlling most land, middle castes having small land parcels, and fewer Dalits (24.1 percent) and bonded workers; and (c) the New Delta, with canal irrigation only since the 1930s, the least land concentration but regions controlled by zamins and inams (royal land grants), the most middle castes, and the fewest Dalits (16.3 percent). Elite power was challenged least in (b). Zones (a), (b), and (c) of the two regions are comparable in many ways. Group relations changed most in the Mississippi and coastal Kaveri deltas.

I studied mobilization closely in three representative pairs of localities that vary in social structure, demography, mobilization, representation, and policy agendas: the revenue blocks of Kilvelur (Coastal Old Kaveri Delta), Papanasam (Central Old Delta), and Madukkur (New Delta); and the counties of Leflore and Holmes (Mississippi Delta), Pike and Amite (Lowlands), and Lee and Pontotoc (Hills). Of these localities, (1) Leflore and Holmes counties and Kilvelur block have the highest prior inequality, key group concentration, mobilization and representation, and redistribution. (2) Pike and Amite counties and Papanasam block exhibit high prior inequality, but greater current elite power, and lower key group concentration, mobilization and representation, and redistribution than (1). (3) Lee and Pontotoc counties and Madukkur block feature the lowest prior inequality, subordinate group concentration, mobilization and representation, and redistribution.

Map 1. Mississippi and Its RegionsFootnote 5

Key: (a) Green: Delta; (b) Yellow: Lowlands, Brown Loam & Loess Hills; (c) Rust: Hills

III. MOBILIZATION

Explanations and Regional Patterns

Doug McAdam (Reference McAdam1999) found that these conditions enabled the southern CRM: peonage decline, agricultural mechanization, urbanization, links with non-Southern blacks, the non-Southern black vote, Cold War ideological battles, and non-southern white support. The movement grew where it could and did base itself on prior community organizations: churches, educational institutions, and the NAACP. These were the interwar conditions in Deep South regions that were industrialized, urbanized, or had major black educational institutions or military bases such as Atlanta, Savannah, Rome, and Fort Benning (Georgia), New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Lake Charles, and Lafayette (Louisiana), and Birmingham and Montgomery (Alabama) (Tuck Reference Tuck2001; Fairclough Reference Fairclough1995; Jeffries Reference Jeffries2009; Dejong Reference Dejong2016). These conditions emerged late in Mississippi, where black colleges had meager resources and low attendance, most clergy depended on whites, urbanization and industrialization were low, and agriculture became mechanized and peonage declined latest. This hampered CRM growth until the 1960s, after which strategic innovation helped the Mississippi CRM become very strong.

Map 2. Kaveri Delta and Its RegionsFootnote 6

Key: (a) Light Green/Orange: Coastal Old Delta; (b) Dark Green: Central Old Delta; (c) Rust: New Delta

No comparable analysis exists of conditions during the periods when and in the regions where Dalits mobilized effectively. Scholars have instead explained when parties incorporated Dalits. Kanchan Chandra (Reference Chandra2004) and Christophe Jaffrelot (Reference Jaffrelot2002: 144–213) claimed that multi-caste parties incorporated more “low castes” earlier in South India because these castes mobilized earlier (Chandra), the caste gap in power, land control, and status was lower, and colonial officials relied less on landlords there (Jaffrelot). They inaccurately identified loci of late colonial Dalit mobilization, which included parts of north (Punjab), west (Maharashtra), south (Kerala), and east (Bengal) India (Juergensmeyer Reference Juergensmeyer1988; Rao Reference Rao2009; Bandyopadhyaya Reference Bandyopadhyay2004); the status gap between upper and lower castes, which was greater in south India (Mendelsohn and Vicziany Reference Mendelsohn and Vicziany1998); and the effects of colonial land settlements. The latter empowered landed castes no more in zamindari regions, where the state gathered taxes through them, than in raiyatwari regions, where peasants supposedly paid taxes directly (Viswanath Reference Viswanath2014b). While zamindari was more widespread in north and east India, and raiyatwari in the south, officials gathered taxes through landlords everywhere, and reduced revenue more in zamindari areas (van Schendel Reference van Schendel1991: 81–83). Upper castes were more numerous and dominated landholding more in North India. But middle castes, not Dalits, had more power and property in South and West India and produced Congress leaders in the mid-twentieth century. Chandra insufficiently differentiated between Dalit and middle-caste mobility, and underestimated the barriers Dalits faced.

Moreover, parties did not engage Dalits extensively in all early Dalit mobilization locales. Starting in the 1940s, some parties incorporated Dalits in Punjab (Congress, communists), Maharashtra (RPI, Congress, communists), and Kerala (Congress, communists). Congress and the communists only aided Dalit demobilization in postcolonial Bengal. Thus, Dalit mobility continued after independence in Punjab and Maharashtra through public sector growth, agrarian commercialization, and industrialization, and in Kerala through land reform, but came to a halt in Bengal (Juergensmeyer Reference Juergensmeyer1988; Jodhka Reference Jodhka2015; Rao Reference Rao2009; Herring Reference Herring1983; Chandra, Heierstad, and Nielsen Reference Chandra, Heierstad and Nielsen2016).

Congress incorporated Dalits extensively only in South and West Indian regions where Dalits had significant education and white-collar jobs: in Maharashtra and Kerala, but not in TN, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, or Gujarat. Even in Maharashtra and Kerala, party leaders did not promote Dalits prioritizing rapid entitlement. Neither the initially upper-caste-led Congress nor TN's middle-caste-led non-Brahmanist movements did much to accommodate Dalit demands. The elite Justice Party opposed Dalit access to temples, pathways, and homestead land, and the Dravidar Kazhagam, which engaged in greater grassroots mobilization and gained much more mass support, curtailed untouchability but resisted the increase in Dalit preferential quotas in the 1940s. The Satyashodhak Samaj promoted Dalit aspirations more because Dalit mobilization was stronger in its Maharashtra stronghold and its leaders were from lower-middle castes that shared more Dalit disadvantages than did middle castes (Rao Reference Rao2009; Subramanian Reference Subramanian1999: 82–129; Basu Reference Basu2011: 165–377). Ambitious Dalit initiatives followed other paths, including in Kaveri beginning in the late 1930s.

To illustrate how emancipatory visions guided mobilization that overcame great obstacles, I will outline the approaches of six early leaders in the case regions: Medgar Evers, Robert Moses, and Aaron Henry in Mississippi, and B. Srinivasa Rao, A. K. Subbiah, and S. G. Murugaiyan in Kaveri.

Mississippi

Blacks undertook extensive mobilization earlier in more urbanized areas and in the upper South where they enjoyed greater independence. But by the 1960s black mobilization in Mississippi grew quickly despite the low level of prior opportunities available there. John Dittmer's contrasting assessments indicated this: “Nowhere were prospects for black protest less encouraging,” and “the Mississippi movement became strongest in the South” (Reference Dittmer1994: 424). Dittmer and Charles Payne (Reference Payne1995) emphasized the Mississippi movement's links to local institutions and expressive forms but did not fully explain how it overcame the high barriers. Their exclusive emphasis on its local roots was in tension with their recognition that leaders who shaped mobilization in Mississippi arrived there as adults (Moses) or had national and international experiences (e.g., in the military: Evers, Henry, and Amzie Moore), and that regional and national developments interacted. For Laura Visser-Maessen, these supralocal links were indispensable: “Stressing the indigenous southern base of the CRM downplays cosmopolitan influences crucial in bringing practical skills, resources, and contacts, a wider political vision, ideas and strategies” (2016: 317). Similarly, Henry, a major regional leader, remembered, “Outside forces brought the change—we had so few tools to do it ourselves” (Curry and Henry Reference Curry and Henry2000: 84). As scholars have focused on mobilizational success, they have not fully explained why gains in representation and wellbeing were comparatively limited in Mississippi.

Black disfranchisement and disentitlement proceeded furthest in Mississippi after its particularly short-lived Reconstruction. The NAACP barely existed until the Second World War, and black voter registration was lowest here: 0.4 percent in 1940 and only 6.7 percent in 1964, compared to 41.9 percent in the former Confederate states overall (Garrow Reference Garrow1978: 7). The segregationist Democratic Party faced no opposition until the 1940s, and from the 1940s to the 1970s the factions with greatest white support resisted integration.

Many whites and blacks were sharecroppers, tenants, and small farmers, or agricultural and poor urban workers. Despite their shared situation, no significant cross-racial class alliances were developed in Mississippi. This was in contrast to what the populists accomplished in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas in the 1890s, and the more extensive alliances built in the 1930s and 1940s by the communists, the Alabama Sharecroppers Union, the National Farmers’ Union, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina.Footnote 7 Delta and Hills whites defended white supremacy complementarily. When challenging Delta planter control, Mississippi's poorer Hills whites sought to tighten segregation due to their sharper competition with blacks. This is contrary to Key's (Reference Key1949) claim that Black Belt planters were always the staunchest segregationists (Kirwan Reference Kirwan1951; McMillen Reference McMillen1989: 41–44). There were more pre-Second World War lynchings in the Delta, but in the 1950s and 1960s the Lowlands and certain Hills counties saw the most Ku Klux Klan violence (Andrews Reference Andrews2004: 66, 72; McMillen Reference McMillen1989: 229–33). Delta elites led party resistance to federal integration and promoted the State Sovereignty Commission, which reinforced racial boundaries, and the Citizens’ Council, which hampered black voter registration and resisted judicial desegregation (Andrews Reference Andrews2004: 174–90; Dittmer Reference Dittmer1994: 27–28, 34, 45–89).

Certain choices helped the CRM overcome these Mississippian conditions. First, emancipatory discourses developed elsewhere engaged regional black communitarian, religious, musical, and oratorical traditions. Second, national organizations like the NAACP engaged regional initiatives such as of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), led by the doctor T.R.M. Howard, which promoted economic self-help in the 1950s. The state NAACP responded better to local activism than did the centralized, litigation-focused national organization, aided by the Council of Federated Organizations’ (COFO) coordination of CRM organizations in the 1960s. Third, the NAACP was built mainly among economically independent blacks who owned property or worked for the federal government or northern companies. Their spatial concentration and economic links enabled mobilization that was more effective than elsewhere in the Black Belt, specifically southwest Georgia and eastern Louisiana (Andrews Reference Andrews2004: 42–43, 79–80; Payne Reference Payne1995: 27–283; Tuck Reference Tuck2001: 158–91; Fairclough Reference Fairclough1995). Fourth, the CRM's prioritization of racial visions and the early emergence of Black Power ideas built cross-class racial solidarity (Woods Reference Woods1998: 183). High racial polarization aided, without determining, such solidarity, which was weaker in other polarized states like Louisiana. Fifth, civil rights leaders emphasized community organization rather than massive protest because of high repression and black vulnerability. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) conducted big boycotts and demonstrations elsewhere, but not in Mississippi (Jeffries Reference Jeffries2009; Garrow Reference Garrow and Eagles1986: 59). Sixth, activists organized nonviolently but armed themselves to counter repression, following practices “deeply ingrained in rural southern America” (Visser-Maessen Reference Visser-Maessen2016: 201). The paramilitary United League (UL) and Deacons for Defense and Justice as well as broader-based organizations patrolled black neighborhoods, protected boycotts, and retaliated against violent white vigilantes and policemen.Footnote 8

The movement grew in the 1950s and early 1960s in parts of the Delta where black tenant-farmer initiatives of the 1880s, 1910s, and 1930s remained in folk memory, and southwestern Mississippi. CRM organizations emphasized different methods (community organization and direct-action protest) and goals: voter registration, public space desegregation, Democratic Party and legislative entry, access to welfare benefits, conducting “freedom schools” that broadened education, providing food and medicine, and promoting black jobs and cooperatives. They initially promoted community organization, voter registration, and Democratic Party entry, and launched direct action only later, in some Delta counties (Holmes, Leflore, Coahoma, and Sunflower).

Many blacks benefitted from land distribution and the establishment of a cotton gin cooperative in the 1930s in Holmes County. In Holmes and Leflore counties, the CRM was built around owner-farmers, military veterans, shop-owners, teachers, “working-class intellectuals” (Payne Reference Payne1995: 181), small businessmen, and Mississippi Vocational College faculty. Higher prior solidarity, more economically independent activists, better organization-building, and the adoption of varied mobilizational methods and goals overcame considerable repression led by the strong Citizens’ Councils through the 1960s and 1970s. These circumstances also aided early success in Holmes and to a lesser extent Leflore in voter registration and elections to county Boards of Supervisors (on which blacks became predominant earliest in Holmes), Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation committees, Community Action Program committees, Head Start centers, and local government. Holmes had the strongest Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and Child Development Group of Mississippi (CDGM) units, and freedom schools. It became the locus of a major court case (Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 1969) which ended “freedom-of-choice plans” and started the south, including thirty-three Mississippi school districts, on the path of extensive school desegregation. The movement was therefore sustained in Holmes and Leflore, and spread to other Delta counties (Sunflower, Washington, Bolivar, Coahoma) and adjacent southwestern counties (Warren, Madison, Hinds, Claiborne, Jefferson), though it was constrained by insufficient middle-class support in Jackson town. These counties saw the greatest black cooperative development in the 1960s and 1970s, and black legislative representation from the late 1960s onward. The second Congressional district, which encompassed these counties, provided the state's only black representative from 1967 to 1976, and it alone consistently elected black representatives.Footnote 9

By contrast, activists were younger and less economically independent in the southwest, where Klan and state repression were higher due to sharper interracial competition resulting from higher white poverty. Moreover, they confronted authorities to desegregate eateries and change school curricula with less prior community organization. This resulted in lower black support and higher repression, which from the mid-1960s undermined the movement in Pike and Amite counties. Civil rights activities were discussed again only in the 2010s in Burgland High School in McComb (Pike County), where protest had centered in 1960–1961. Black representation also remained limited there—McComb, with a 66 percent black population, elected its first black mayor only in 2006. The movement succeeded where it stressed community organization and declined where direct action drew insufficient support, and this reinforced the former methods.

CRM mobilization was limited until the early 1970s in the Hills, except in the southeastern counties of Jones, Forrest, Harrison, and Jackson. Beginning in the 1970s, it grew in the northeastern Hills counties of Marshall, Lee, Pontotoc, Chickasaw, and Tippah. There, the United League utilized marches, boycotts, and armed self-defense to oppose Klan and police violence, the misappropriation of black land, and job and service discrimination, and to demand anti-poverty programs. Active until the late 1980s, the League initiated black local government representation in northeast Mississippi.Footnote 10

Mississippi's CRM leaders pursued different strategies suited to different regions which proved compatible until the mid-1960s. Participation in the Second World War connected Medgar Evers to racially inflected African nationalisms and the Kenyan Mau Mau Uprising, from which he drew lessons for racially polarized Mississippi. While the daunting local constraints convinced Evers to mobilize nonviolently for racial integration, his early inclinations helped him to reconcile nonviolence with armed self-defense and connect the NAACP, whose field secretary he was in the 1950s and early 1960s, with SNCC and CORE Black Power advocates. Close association with militant organizations distinguished Mississippi's NAACP from some southern units (e.g., Louisiana's) that disengaged from the 1960s upsurge, and helped it to mobilize the Delta, in particular. Such coalitions were less effective where community organization was weaker (Dittmer Reference Dittmer1994: 49–52, 77–89, 158–69; Payne Reference Payne1995: 43–68, 158–64, 185–86, 285–90; Williams Reference Williams2011).

Robert Moses focused the cosmopolitan-egalitarian vision he had developed in Harlem on addressing rural Mississippi's extreme racial inequities. Due to high repression, in the 1960s he directed Mississippi's SNCC toward community organization, grassroots leadership development, and voter registration rather than big demonstrations for public facility integration such as SNCC launched in South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. He promoted militant direct action where community mobilization had built a prior base (e.g., Holmes and Leflore counties), but discouraged it elsewhere (e.g., Pike and Amite counties). This strategy accelerated lower-class participation and bridged classes, generations, and outlooks at the CRM's peak (Dittmer Reference Dittmer1994: 73–89, 101–19, 146–55, 158–69; Payne Reference Payne1995: 3–4, 43–68, 93–140, 240–50; Moses et al. Reference Moses1989; Visser-Maessen Reference Visser-Maessen2016).

Aaron Henry, from a Delta sharecropper family, entered the propertied middle-class as he rose to the NAACP's state presidency. He was also the Council of Federated Organizations’ President and became important in the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, the clergy-based Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and MFDP. Such flexibility enabled him until the mid-1960s to unite blacks across “age, ideology, and social class” and embrace SNCC's organizational focus (Curry and Henry Reference Curry and Henry2000: x, 215). However, his economic mobility and a white employer's early mentorship probably inclined him toward class and interracial compromise. After accepting limited black Mississippian representation at the 1964 Democratic Party national convention, he opposed SNCC's, CORE's, and MFDP's militancy, while promoting black access to education, health care, housing, the media, the Democratic Party, and the legislature. Henry helped form the Loyalist Democrats, based among middle-class blacks and integrationist whites, which promoted planter and industrialist interests. Working with white economic elites, he built the Mississippi Alliance for Progress, a federal government-supported alternative to the grassroots Child Development Group of Mississippi. Most federal aid was channeled through the Alliance, which constrained the distribution of War on Poverty benefits through CRM networks (Payne Reference Payne1995: 56–66, 340–45; Dittmer Reference Dittmer1994: 120–23, 377–78; Curry and Henry Reference Curry and Henry2000; Sanders Reference Sanders2016: 153–87; Hamlin Reference Hamlin2012).

Cooperation across such diverse outlooks became more difficult after black mobilizers reached shared goals through the major national rights legislation of the 1960s that gave blacks access to representation and the Democratic Party. The NAACP thereafter emphasized institutional integration, biracial alliances, and Democratic Party entry, while SNCC, CORE, and MFDP developed black schools, neighborhoods, and cooperatives, built exclusively black political institutions, presented independent electoral slates, and called for Black Power. These differences widened over Mississippian representation at the 1964 Democratic national convention, the terms of biracial alliances, and cooperative development, and led to dissolution of the Council of Federated Organizations. As federal resources were channeled primarily through the NAACP and Loyalist Democrats, MFDP declined and CORE and SNCC retreated from Mississippi. Integrationists, allied with moderate and elite whites, predominated among black Mississippian Democrats, and racial egalitarianists remained marginal to parties. But civil society organizations formed by former MFDP, CORE, and SNCC activists continued to promote black community development, institutional access, and jobs.

Kaveri

Considerable lower-class agrarian mobilization occurred primarily among Dalits in Kaveri from the 1930s into the 1970s. Similar agrarian initiatives were more widespread in Kerala, but Dalits were less centrally involved in them. Dalit mobilization grew later in Kaveri than in Maharashtra, Punjab, Kerala, and Bengal, but earlier than in other regions, including elsewhere in TN, where it mushroomed only starting in the 1980s and 1990s. Analyses have highlighted agrarian socioeconomic features that enabled the high mobilization of lower strata in parts of the Kaveri Delta and not elsewhere (Bouton Reference Bouton1985; Gough Reference Gough1989). They did not focus on mobilization patterns, non-agrarian social change, or the effects of the caste-class overlap. Nor did they indicate why Dalit mobilization was less extensive than in Maharashtra or Punjab or why agrarian protest was less widespread than in Kerala, Bengal, and Andhra Pradesh.

Starting in the early twentieth century, Kaveri Dalits advanced more than did black Mississippians, through education, employment elsewhere in the British Empire, becoming middling tenant- or owner-farmers, gaining homestead land, or commercial enterprise. As in Mississippi, such upwardly mobile individuals were among the early political activists. Some built links with the Dalit-led neo-Buddhist Adi-Dravida Mahajana Sabha and Indian nationalist organizations committed to universal franchise and ending untouchability (Basu Reference Basu2011: 224–342; Viswanath Reference Viswanath2014b: 190–216). Nevertheless, prior community institutions were weaker than in Mississippi, and mobilizers used them ineffectively. Dalit elites and upper-caste reformers started Dalit schools to avoid discrimination in common schools, but less extensively than African Americans. Movements reached people at monthly Dalit hamlet meetings, but not through Dalit temples and churches.

While community institutions were weaker, party competition and relations between regional, state, and national politics favored group mobilization more in Kaveri. Whereas the Democratic Party and its segregationist offshoots dominated Mississippi and suppressed participation there until the 1970s, Kaveri was TN's most politically competitive region from the 1940s onward, with greatest voter participation (Subramanian Reference Subramanian1999: 19). Congress grew there from the 1920s, as did the communists and Dravidianists starting in the late 1930s. There were tensions between the National Congress's call for Dalit inclusion and the predominance of dominant caste landlords, such as Kunniyur Sambasivayyar and A. Krishnasami Vandayar, in the Delta party leadership. These leaders tolerated minor increases in Dalit public access more than their Mississippian counterparts did regarding blacks, but they equally resisted changing agrarian relations.Footnote 11 The middle- and lower-middle-caste-led Dravidar Kazhagam and Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam gained significant Dalit support in parts of the coastal Delta (Nagaipattinam, Kilvelur, Thiruvarur blocks) by promoting Dalit public access and peasant welfare without opposing agrarian bondage due to their associations with big landlords like Nedumbalam Samiappa Mudaliar.Footnote 12

Beginning in the late 1930s, the communists engaged Dalits much more closely by modifying a Marxist focus on industrial workers to address the main inequities in a predominantly agrarian caste-stratified society. They also moderated their vanguardism to engage prior concerns, much as nationally influential African American discourses were altered in Mississippi. Strategic flexibility was easier in Kaveri because mobilization began there at the outset of Indian communist agrarian initiatives. Sensing Kaveri society's main fault lines, B. Srinivasa Rao, a Brahman from Karnataka who led regional communist mobilization until his death in 1961, initiated a focus on lower agrarian strata and Dalits. He incorporated some earlier mobilizers in the Old Delta like Manalur K. Maniammal, a veshti-wearing Brahman widower who had formed the Kisan (Peasant) Socialist Party in Kilvelur block. He also developed new local leaders like Kalappal K. Kuppuswami, a Dalit pannaiyaal, and A. K. Subbiah, a Dalit tenant-farmer turned owner-farmer, who led agitations against the Kottur block's major landlords and landowning religious institution.

In TN, the communists gained greatest support in Kaveri because their egalitarianism effectively engaged the region's deep inequalities. They addressed Dalit concerns and gained the greatest backing among Dalits, being called parties of the Pallar and Parayar. Their Marxist vision led them to link Dalit and pannaiyaatkal demands to those of other lower agrarian strata, such as agricultural workers, sharecroppers, and tenant-farmers from Dalit, lower-middle, and middle castes. These Marxists translated “proletariat” as paattaalikal (toilers), popularly understood to fit this multi-caste coalition. Such renditions of class categories limited caste tensions within the communist regional coalition, which included different Dalit jatis and middle castes, which posed greater problems for Dalit organizations. They also meant that Dalit solidarity enabled class assertion, unlike the trends where lower-class politics was weaker (Harriss-White Reference Harriss-White2003: 190–93).

The communists countered landlord and state violence, as Mississippi's mobilizers did, using armed self-defense. They initially put a stop to whipping and other anti-Dalit indignities (specifically, force-feeding excreta) and enforced Dalit entry into upper-caste streets. Subsequently, their pressures ended bondage, raised agricultural wages and sharecroppers’ and tenants’ returns, and extended the duration of agrarian contracts, but they directly brought about little land redistribution (Tamil Nadu Vivasayigal Sangam 2008; Veeraiyan Reference Veeraiyan2010; Menon Reference Menon1979; Ramakrishnan Reference Ramakrishnan2007; Krishnan Reference Krishnan2014).

Dalits predominated among regional communist cadres but not in the leadership. Nevertheless, regional upper- and middle-caste communist leaders opposed caste exclusions, and certain Dalits became early local leaders, notably K. Kuppuswami in the 1940s, and A. K. Subbiah, S. G. Murugaiyan, and P. S. Dhanushkodi in the 1950s. Bouton reported Kaveri Dalits feeling in the 1970s that non-Dalit communists defended their interests better than did non-communist Dalits. The communists however formed an Untouchability Eradication Front only when Dalit parties emerged in the 2000s.Footnote 13

The communists retained two of Rao's tactics—using armed power and addressing intertwined caste-class demands—but after his death they entered local governance more and increased Dalit local leadership. Both these continuities and changes were represented in the careers of S. G. Murugaiyan, who became TN's first Dalit block Chairman in 1962 in Kottur, and A. K. Subbiah, among the first Dalit communist state legislators elected in 1952, from Mannargudi. Murugaiyan used local office to improve Dalit hamlet infrastructure and gain Dalits access to village temples, streets, and wells. Carrying arms helped him overcome local resistance. Reforms benefiting secure tenant-farmers in the 1970s led the upwardly mobile to shift to the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam. They included some Dalits, most notably Subbiah, who allied himself thereafter with local elites, much as Aaron Henry had in Mississippi.Footnote 14

The coastal Delta's polarized social structure and early twentieth-century advancement helped its lower agrarian strata mobilize. These groups’ ambitions were contained since the less polarized conditions in much of India did not favor such mobilization, and the Indian state repressed radicalism while accommodating specific agrarian and caste demands. Furthermore, landowners’ shift to high-yielding grains and double-cropping enabled them to pay higher wages, which reduced demands for land distribution (Bouton Reference Bouton1985: 229–30). Mobilization was extensive in the southern and central coastal Delta, linking pannaiyaatkal, free agricultural labor, sharecroppers, and insecure tenants, and Dalits (44.3 percent of the population) with middle castes, in Kottur, Thiruthuraipundi, Thiruvarur, Kilvelur, Thalagnayiru, Kizhayur, Nagaipattinam, and Thirumarugal blocks. Communists controlled 20–30 percent of village panchayats there throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Starting in 1938 Kilvelur, TN's sole Dalit-majority (52.1 percent) block, witnessed mobilization of the agrarian poor, drawn both from Dalits and middle castes, against landlords, such as the Madathunatha Desikar family of Valivalam and Kamma Naidu families of Thevur, Radhamangalam, and Venmani. Dalits such as ex-pannaiyaal Dhanushkodi became local communist leaders, and many Dalits and former pannaiyaatkal and sharecroppers gained higher wages, small agricultural plots, and access to teashops, temples, and elite streets. These gains were aided by circular Dalit migration to towns, Southeast Asia, and the Persian Gulf, extensive communist and Dalit local government representation from the 1960s onward, the Dravidar Kazhagam's Agricultural Workers’ Association's agreements with the less repressive Muslim landowners numerous in the block's northern part, and, beginning in 1969, the involvement of a Gandhian reform organization.Footnote 15

Communist agrarian mobilization drew moderate support, mainly among Dalits, in the northern coastal Delta (Mayiladuthurai, Sembanarkoil, Sirkazhi, Kollidam blocks), and parts of the central Delta (Nannilam, Nidamangalam, Valangiman blocks). It remained limited elsewhere in the central Delta, which had more middle-caste small farmers and secure tenants who were disinclined to challenge same-caste landlords and landowning religious institutions. Nevertheless, beginning in the 1980s various agrarian associations did secure tenure in agricultural and homestead land there.

In Papanasam block, upper- and middle-caste landlords retained considerable land and authority even after agricultural land ceilings were lowered throughout TN in the 1960s and 1970s, notably the Moopanar lineage of Kabisthalam and Sundaraperumalkoil, whose G. Karuppiah Moopanar became a national-level Congress leader. The V. S. Thyagaraja Mudaliar clan of Vadapathimangalam, which shifted much of its over 5,000 acres of land from paddy to sugarcane so as to evade land ceilings, established a sugar factory in Thirumandangudi that operated profitably through the 1990s and 2000s. Many other landowners, particularly Brahmans, sold land to pursue urban occupations. In the 1950s and early 1960s, communist mobilization in the block's eastern part against debt bondage and for higher wages and public access, gained some support among Dalits, who in 2011 were 21.6 percent of the population, but that mobilization and support declined thereafter. Dalit local government representation and lower strata gains remained limited. Nonetheless, in southern Papanasam block many tenant-farmers, including some Dalits, bought land from Muslims who sold it below market value as they were working in the Persian Gulf and Southeast Asia.Footnote 16

Middle-caste tenants and small farmers participated in Congress-led mobilization in the 1940s to distribute zamindari and inamdari estates, and to seek debt relief and community control over commons land and ponds in the New Delta's Pattukottai, Orathanad, Peravurani, Aranthangi, and Gandarvakottai taluks. Communists gained support in Madukkur block through agitations against the Madukkur and Athivetti zamins, but the party faded throughout the New Delta after the zamindari and inamdari arrangements were abolished in the late 1940s. Since most local Dalits (who in 2011 made up 16.3 percent of the New Delta population, and 12.8 percent of Madukkur block's) were non-agrarian workers or gained little leverage to reduce their dependence on landholders, they did not engage with these primarily agrarian conflicts and, unlike many middle- and lower-middle-caste tenant-farmers, they gained little land when zamins and inams were dissolved.Footnote 17

Regional communist strategies were suited to the polarized coastal Delta, and had limited impact elsewhere in Kaveri and TN. In Kerala and Bengal, by contrast, communists adopted more varied agrarian strategies and linked them better with urban mobilization. These latter approaches built broader coalitions and gave communists prolonged state government control, which in turn helped them offer more extensive benefits than could local and state representatives from Kaveri. The close connection of Dalit and agrarian lower-class mobilization also limited the spread of Dalit mobilization in TN, unlike in regions where it was based in a broader Dalit lower-middle-class that had formed through greater urbanization and industrialization (Maharashtra, twenty-first-century north TN), agrarian commercialization (Punjab), or education and land redistribution (Kerala) (Rao Reference Rao2009; Jodhka Reference Jodhka2015; Heller Reference Heller1999). Limited middle-class formation similarly delayed movement growth in Mississippi, but it did not restrict its geographical spread as much there because more diverse organizations and strategies were involved.

Comparison of Cases

Agents: The polarized agro-ethnic structure of the coastal Kaveri and Mississippi deltas proved conducive to mobilization when politico-economic changes created opportunities. Locals used these opportunities best when extra-regional forces engaged local concerns. Black-led civil society organizations led mobilization in Mississippi and elsewhere in the United States. Political parties played this role in India: the communist parties, which had upper- and middle-caste leaders, mobilized Dalits mainly in Kaveri, while the Congress, communist, socialist, and Dalit parties did so in many other regions. Parties engaged Dalit civil society differently: Dalit parties emerged from it, the communists and socialists sometimes engaged with it closely, and Congress sought paternalistic control.

Visions, Alliances, Parties

Organizational strategies were shaped by the interplay of movement organizations’ pan-regional ideologies with regional stratification and contention. In Mississippi, the greater social gap between the key group and others made the exclusionary category (race/caste) more central to organizers’ visions. Encountering overwhelming local white hostility, Mississippi's CRM organizations mainly mobilized blacks. Multiracial alliances were feeble there until the mid-1960s, which pressed both integrationists and Black Power proponents to rely on black community institutions and racial visions. The Democratic Party gained black votes beginning in the late 1960s, but the party underserved black interests so as to retain white support because party competition for black support declined, as happened elsewhere in the United States.

Kaveri's communists focused on class, but they also addressed caste exclusions due to the high caste-class overlap. Championing Dalit opposition to exploitation, repression, and indignity shaped communist strategy in Kaveri, and to a degree in Kerala, Maharashtra, and Punjab, but not in Bengal. The communists’ class focus and engagement of Indian nationalist, language-based, and anti-caste discourses aided multi-caste alliances, which in Kaveri were strong from the outset. However, their close association with Dalits hastened communist decline among other groups from the 1970s. The Dravidian parties grew thereafter, also dispersing Dalit support in the process. That the key group in Kaveri was highly mobilized forced parties there to serve its interests, which they did that much more as the group's support dispersed. In Mississippi, by contrast, the key group aligned with a party that did not pursue its interests much.

Timing, Location

High group mobilization in Kaveri lasted from the late 1940s to the mid-1970s, but in Mississippi only from the early 1960s into the early 1970s. In both cases it was highest and most sustained in the zones that were the most polarized and had the greatest key group concentrations (coastal old Kaveri and Mississippi deltas), was less extensive in moderately polarized zones (central Kaveri Delta, Mississippi Lowlands), and was more limited in the least polarized zones (new Kaveri Delta, Mississippi Hills). The high mobilization in both regions and the higher mobilizations in the more polarized zones, even though group autonomy had been less in these zones, exemplify how deeply disadvantaged ethnic minorities can press their interests effectively if they adopt imaginative strategies. Mobilization spread more widely in Mississippi because CRM organizations there were more diverse and less centralized than were Dalit-oriented organizations in Kaveri, and this enabled them to pursue more varied strategies that better matched zone-specific opportunities.

Accommodation

Mobilizers faced considerable repression until the 1960s in both regions, but were accommodated sooner in Kaveri, from the 1950s to the 1970s, than in Mississippi, where accommodation began only in the late 1960s and remained less complete. In Kaveri repression declined after a landlord's goons killed forty-four Dalit women and children in Venmani in 1968. The high level of violence, and that the Madras High Court overturned the District Court's punishment of Irinjur Gopalakrishna Naidu, the landlord-President of the Paddy Producers Association, and instead found some Dalit survivors guilty of violence, brought national attention to the region's iniquities and motivated the Gandhian Sarvodaya movement to support the coastal Kaveri's agricultural workers, especially Dalits. This movement relied elsewhere on voluntary land donations, but to compete with the communists among Dalits and the agrarian poor in Kaveri, it organized campaigns to press landowners to sell land cheaply. Its Land for Tillers Freedom (LAFTI) bought 13,000 acres of land from landlords and sold an acre or less each to fifteen thousand coastal Delta Dalit women at low prices, offered housing subsidies, organized artisanal cooperatives, and imparted skills. Sarvodaya provided benefits, including minor landownership that communists rarely enabled directly, independent of communist militancy, even to communist cadre who overcame their party leaders’ resistance.Footnote 18 The accommodation of some demands and the increase in viable alternatives for the coastal Delta's lower strata reduced their resort to militant protest but pressures remained to benefit these groups, particularly as party competition increased among Dalits. African American gains were more limited in Mississippi, though less so where black community institutions endured, because those seeking racial equality quickly were marginalized from political parties.

IV. INSIDER RESPONSES, POLICY BENEFITS, AND REPRESENTATION