Historians documenting the religious and political dimensions of printing have written extensively about the complications caused by colonial struggles and Christian missionary rivalries, yet they have not fully explored how printing technologies that contributed to Orientalist knowledge production also propagated beliefs about linguistic and other semiotic phenomena. The mid-nineteenth-century archives of two marginal and failing colonies, French India and French Guiana, offer important insights into the ideological and technological natures of colonial printing, and the far-reaching and enduring consequences of the European objectification of Indian vernaculars. The French in India were torn between religious, commercial, and imperialist agendas. They differed significantly from their Portuguese Jesuit predecessors, who from the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries focused exclusively on religious conversion, and their British competitors, who from the eighteenth century pursued language and ethnological study mostly to modernize the Raj's bureaucracy. French writers and printers throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries both promoted Catholicism among so-called Hindu pagans and advanced the scientific study of Indian languages and peoples. They concentrated on Tamil, the majority language spoken in the colonial headquarters of Pondicherry. There, a little-known press operated by the Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP) (Paris Foreign Missions) published far and wide, including works for the colony of French Guiana, where several thousand Tamil indentured laborers had migrated since 1855. These included bilingual Tamil and French dictionaries, vocabularies, grammars, and theological works printed for the “good of the colony.”

In what follows, I draw on seldom-discussed materials from the Archives nationales d'outre-mer in Aix-en-Provence, France. I analyze the lexical, orthographic, and typographical forms, metalinguistic commentaries, publicity tactics, citational practices, and circulation histories of vocabularies, dictionaries, and grammars produced in French India throughout the nineteenth century. My purpose is to identify their “semiotic ideologies,” defined as everyday beliefs about what constitutes a sign and how signs act as agents in the world (Keane Reference Keane2003). I explore how these ideologies changed over time, and trace their social consequences. I argue that signs of “error” in and as texts became publicly interpretable at the historical convergence of disparate religious and scientific movements that questioned the veracity of knowledge and fidelity of sources from different perspectives. I employ a comparative approach to situate Tamil colonial linguistics within a transnational field of knowledge production encompassing rival countries and rival missionary orders. I seek to illuminate the evolving relationship between Dravidian and Indo-Aryan colonial linguistics, French Indology and other Orientalist agendas, and Catholicism and secularism. I also examine the interdiscursive and material—that is, technological—linkages between language, educational, and immigration policies in French India and French Guiana.

Since the sixteenth century, European writers and printers of Tamil books had perceived “errors” in linguistic forms, communicative practices, and racialized bodies, and wrote extensive commentaries about the need to standardize, reform, and convert them. Europeans in colonial South Asia believed they had a moral obligation to transform Indians’ supposed sinfulness and backwardness by inculcating them with the signs of a perfected language, religion, and racial comportment.Footnote 1 There were loud disagreements as to which standardized code, theology, and model of civil society best represented this ideal. What all agreed upon was that the material affordances of the printing press and wood and metal types in Indian fonts promised greater durability and fixity, and the ability to eradicate linguistic and stylistic errors through print and thereby dramatically transform the cultural practice of writing. In this way, print technologies introduced alternative notions of authorship, copyright, and translation (Venkatachalapathy Reference Venkatachalapathy2012) and ideologies of perfectibility and error, and greatly influenced the evolution of linguistics and literature in India over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2009).

In the century following the French Revolution, beliefs about the perfectibility of languages also reflected enduring political, religious, and scientific debates concerning the universality of citizen rights, the legitimacy of caste hierarchies, and the value of European or vernacular education. All of these impinged upon the scientific study of Indian history, languages, and cultures. For example, in comparing classical languages such as Latin and Greek with those found in India and elsewhere in Asia, French Indologists based in Pondicherry and Paris differed as to whether Dravidian- or Sanskrit-derived languages should be considered and taught as primordial Indian languages par excellence. Underlying these wide-ranging debates was a shared classificatory logic of a sort that Keane (Reference Keane2003) has called a “representational economy,” through which disparate signs failing tests of religious truth or scientific rigor could be readily interpreted as iconic of, and substitutable for, one another through explicit metalinguistic labor.

These “errors” spanned the domains of linguistics (e.g., lexicography and orthography), metalinguistics (e.g., copying, translation, interpreting, labeling), and stylistics (e.g., typography), as well as theology, policy, and pedagogy. Widely differing concepts of religious error, including heresy, paganism, and adversarial theology, were equated with scientific errors such as grammatical irregularity, ethnolinguistic and philological miscategorization, and flawed immigration and educational policy. This occurred via publicity tactics that connected presses across South Asia with institutions in other colonies. By the mid-nineteenth century, these discourses intersected in the spice plantations of French Guiana, where the children of Tamil indentured laborers attending French-medium Catholic schools likely received Tamil books shipped from the MEP-run press in Pondicherry. Thus the publicity tactics of an obscure press, looking overseas to enhance the fame of the failing French Indian colony and to market books to broader religious and secular audiences, rendered Catholic and scientific ideals of “perfectibility” as more-or-less interchangeable signs. This signaled a turning point in Tamil colonial linguistics. Such tactics display not only how printing technologies mediated ideologies concerning the agency of “erroneous” books, bodies, and polities, but also how refrains of “error,” echoing across multiple discursive domains, made colonial projects appear more or less liable to success or failure.

To provide evidence for this argument, this article begins by detailing how a linguistic anthropological analysis of colonial linguistics differs from other approaches to the historical relationship between language and printing by highlighting key processes of interdiscursivity that constitute the archives. I will then briefly trace the evolution of a semiotic ideology of “perfectibility” and “error” that guided missionary and scientific work in Tamil from the sixteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries. I discuss how printers and printing technologies, rather than authors and scribal practices, preeminently shaped this colonial enterprise. The paper's next section analyzes the linguistic and typographical forms, metalinguistic commentaries, publicity tactics, citational practices, and circulation histories of select dictionaries, vocabularies, and grammars written or printed in Tamil and French over the nineteenth century. I discuss whether and how religious and scientific conceptions of error coincided, as French officials struggled unsuccessfully to compete against more enterprising British officials. A final section explores the sociohistorical context within which bilingual grammars and dictionaries printed in Pondicherry could have been gifted as end-of-year prizes to the children of Tamil indentured laborers attending secularizing schools in French Guiana. My conclusion examines the nature of technological and interdiscursive linkages between the Indian and Atlantic Ocean worlds.

COLONIAL LINGUISTICS, INTERDISCURSIVITY, AND POWER

Descriptive linguistic projects first became resources for “figuring and naturalizing inequality in the colonial milieu” (Errington Reference Errington2001: 20) in the mid-sixteenth century. Yet not until the nineteenth century did a “veritable explosion in the grammar factory” produce what Thomas Trautmann has aptly called an “impulse to blanket the world in grammars and dictionaries” (Reference Trautmann2006: 39). Bernard Cohn famously described how grammars and dictionaries transformed “indigenous” forms of “textualized knowledge” into powerful “instruments of colonial rule” (Reference Cohn1996: 21). Crucial here were technological inventions like the printing press, which Elizabeth Eisenstein presented as “the first ‘invention’ which became entangled in a priority struggle and rival national claims” (Reference Eisenstein1983: 4). These inventions dramatically altered the practice of writing in Europe and its colonies and made it possible for authors and printers of grammars and dictionaries to attain immortality (Finkelstein Reference Finkelstein and Bazerman2007). By standardizing variation in native language use and highlighting errors in the scribal transmission of knowledge, European presses presented themselves as producing visually perfected texts, with uniform orthographies, modernized typefaces and aesthetics, and in some cases, more Christian-friendly or virtuous knowledge than found in the Indian sources from which they freely plagiarized. Collectively, these assertions index the language and semiotic ideologies of “perfectibility” and “error” characteristic of colonial printing. They reinforce the conclusion that “the pursuit of perfection … has always been the aim of the type cutter and the printer” (Jury Reference Jury and Bazerman2007: 42), whether by striving for lines of regular thickness and balance of angle or searching to advance religious, linguistic, and ethnological knowledge.

The linguistic anthropological study of colonial linguistics reveals additional dimensions of power through its attention to whether and how reflexive processes of “interdiscursivity” and “intertextuality” (Briggs and Bauman Reference Briggs and Bauman1992; Silverstein and Urban Reference Silverstein and Urban1996) also institutionalize and normalize language and semiotic ideologies within and across sociohistorical settings. Briggs and Bauman assert that generic tools of “discursive ordering” (Reference Briggs and Bauman1992: 164) can foreground the status of utterances or written phrases as recontextualizations (or citations) of prior discourses to naturalize or disrupt texts and their cultural realities. Since recontextualized utterances found in multilingual translations are often less obvious to monolingual readers, their role in constituting or challenging power relations and social categories can go unnoticed. To compensate, scholars studying the generic conventions that influence the printing of multilingual grammars and dictionaries, and their political, economic, and ideological realities, need to compare metalinguistic commentaries and linguistic forms across both genres and historical periods.

William Hanks articulates this methodology in his study of the fifteenth- through nineteenth-century Spanish documentation of Yucatec Maya. He compares the format, content, and style of two different genres: the bilingual dictionaries, vocabularies, grammars, and other metalinguistic works that were “at once descriptive and prescriptive, analytic and regulatory,” and the translations of Christian catechisms and sermons that redefined the moral and spiritual order of vernacular language use (Reference Hanks2010: 4). Hanks further points to “strong ties between the two kinds of discourse,” including the “many details of linguistic form, common authorship, consistent pedagogical aims, many cross-references, and other intertextual ties” that highlight a common Christianizing project of reducción (ibid.: 11–12). These “spread by way of linguistic practices … through speech and gesture, writing, reading, and different genres of discourse” (ibid.: 88). Such intertextual practices thus brought together the work of linguists, government officials, and missionaries to achieve the widespread institutionalization of Spanish colonial power.

Also attesting to how interdiscursive processes reinforce or disrupt power are historical and anthropological studies of value-laden and potentially self-reflective “citational practices” (Goodman, Tomlinson, and Richland Reference Goodman, Tomlinson and Richland2014; Nakassis Reference Nakassis2013). For example, Miyako Inoue (Reference Inoue2011) discusses how court stenography in late nineteenth-century Japan changed from being a skilled and scholarly craft to a more routinized form of mechanical reproduction that reinforced images of a modernizing state. Although court documents cited the names of both stenographers and court speakers, they held only speakers responsible for the testimony's accuracy and elevated stenographers to the status of quintessentially modern Japanese men. Other studies describing far-flung financial and technological networks of authors, printers, sponsors, and subscribers have discussed how such interconnections facilitated the circulation of books and other print media between colonial centers and peripheries to propagate imperial systems of domination (Errington Reference Errington2001). Hence, when Cohn attributed the fame of Sir William Jones’ “discovery” of the Indo-European proof in 1786 to “the rhetorical force that accrued to his work as it traveled from India to a European readership” (Reference Cohn1996: 31), he alluded to provincial French and German efforts to reconstruct this language family, which were perceived as flawed, and to how Jones’ proof justified the expansion of British colonial power into intimate spheres of Indian social life.

In the present paper I want to synthesize from these theoretical approaches to characterize and trace the language and semiotic ideologies afforded by printing and writing technologies across space and time. In doing so, I inquire specifically into the political, economic, and social impacts of Tamil books printed in French India and shipped to French Guiana. This framework hinges on the insight that, whether one measures a book's success in terms of its sales, reprints, and domestic or international reputation, one can also link its fame metonymically to the rise or fall of the printer, the quality of the press and types, and the power and reach of the sponsoring empire. Such metonymic signs, which bring to mind the objects to which they have a spatiotemporally associative or contiguous (that is, indexical) relationship, can appear similar (that is, iconic) and also substitutable with one another. This is much like the way in which different entextualized chunks of discourse can appear to be easily transposable across space and time, depending on the overarching ideological framework (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2005). Thus, in addition to analyzing lexical entries, orthographic and typographical choices, citational practices, and circulation histories, I will examine how metalinguistic commentaries embedded in publicity tactics also evaluated the relative fame of books, the reputations of printers, and the outcomes of colonial policies. My intent is to identify which iconic signs—linguistic and otherwise—collectively constitute a semiotic ideology of “perfectibility” and “error.”

Few historiographies have closely examined the interdiscursive features of circulating South Indian texts to explicate the factors that contribute to, and the consequences of, colonial language and semiotic ideologies. A few exceptions include A. R. Venkatachalapathy's (Reference Venkatachalapathy2012) analysis of Tamil scribal and publishing traditions, Lisa Mitchell's (Reference Mitchell2009) monograph on Telugu colonial linguistics and ethnolinguistic nationalism, and Xavier and Županov's (Reference Xavier and Županov2015) historiography of Catholic Orientalist scholarship. Whereas Venkatachalapathy highlights the political and economic factors and technological changes that have influenced copying, printing, and publishing since the nineteenth century, Mitchell interrogates the very premise that “comparative historical linguistic analysis is regarded as a universal method of knowledge production existing outside of language ideology” (Reference Mitchell2009: 102) and identifies an ideology that attributes error to scribal documents and perfectibility to printed textbooks (especially educational primers). Xavier and Županov explore the deeper religious history of this ideology by analyzing literary and scholarly activities outside of the British Protestant canon. They did not include French sources, however, and they and others caution that without this missing analysis “the comprehensive history of French … Orientalism is yet to be written” (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015: xxx; see also James Reference James2000). I make a similar claim here, that in order to understand the relationship of French Indology to the policies of failing French colonies we must analyze how the interdiscursive processes institutionalizing and naturalizing an ideology of “error” and “perfectibility” emerged from four centuries of European printing in Tamil. By highlighting how interdiscursivity is achieved through metalinguistic labor and afforded by the material properties of printing technologies, we can clarify how texts constitute and are constituted by colonial power.

ERROR AND PERFECTIBILITY IN TAMIL PRINTING

The first four centuries of writing and printing by Europeans in Tamil was characterized by intense competition and outright animosity between rival Catholic and Protestant missionary orders in India, including the Portuguese, Italian, and French Jesuits, Danish Lutherans, the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, and the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Printers and writers also included the occasional merchant, physician, traveler, and government official, but whether sponsored by wealthy converts, landlords, or royal crowns (Županov Reference Županov2007), they often disagreed about the truthfulness of Indian knowledge and the accuracy of Tamil texts in ways that touched upon contentious matters of theology and colonial policy. Also, despite limited funds, paper and ink supplies, and skilled workers to cut movable types (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015), printing technologies engendered an epistemological shift among Indian pandits and other “local knowledge experts” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2009: 21). They learned to view their languages from a foreign perspective as something to be “acquired, manipulated, and reformed” rather than used practically or venerated (Blackburn Reference Blackburn2003: 27). Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the activities of European printers of Tamil books led to the identification and categorization of textual errors based on interchangeable criteria of linguistic irregularity and religious and scientific falsehood. A growing focus on “error” gave rise to a semiotic ideology dialogically constituted by multiple Orientalist discourses, each imagining a different state of perfection, or at least pathway to perfectibility, through competing Christian beliefs, European languages, and colonial models of civil society.

The first notion of error, which conflates religious falsehood and linguistic irregularity, coincided with the Portuguese Jesuit presence in southern India. In the aftermath of Francis Xavier's evangelization of Tamil-speaking Parava fishermen living along the eastern Fishery Coast during the 1530s, Portuguese Jesuits established the first Indian printing presses in Goa, Cochin, Quilon, and Ambalacat. There, they later fabricated wooden and metal types in Tamil to print multilingual catechisms and other theological texts, botanical and pharmacological books, dictionaries, and grammars translated or written in Tamil, Latin, and Portuguese (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015: xxxiii). The first Portuguese catechism translated into Tamil, Cartilha ē lingoa Tamul e Portugues, was printed in 1554 in Lisbon by three Indian priests, Vincente de Nazareth, Jorge Carvalho, and Thome da Cruz (Županov Reference Županov1998; Zvelebil Reference Zvelebil1992). In 1679, Antão de Proença printed the first Tamil-Portuguese dictionary, Vocabvlario tamvlico (James Reference James2000). Jesuits paid little regard to citing authors as a means to authenticate the fidelity of their sources. They shared informants with one another and borrowed liberally from Indian and Christian texts to produce dictionaries and grammars featuring multiple, anonymous authors. Rarely printed and continuously revised, these books represented “temporal and universal refutations of adversary theologies,” such as Saivism, Vaishnavism, and Protestantism (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015: 231; Županov Reference Županov2007).

Xavier and Županov refer to the corpus of Portuguese Jesuit scholarship on India as “Catholic Orientalism,” a religious enterprise that inherited the Roman idea of “universalism” yet also incorporated the modern notion of “discontinuity” or “singularity” to explain errors in classical knowledge not verified by empirical research (Reference Xavier and Županov2015: 8–9). Jesuits touted the dominant Christian point of view that “there was only one ‘true’ religion or law and all others were thus compared with it negatively and by degrees of falsity, error, inadequacy, monstrosity, diabolic imitation, and so on” (ibid.: 117). They sought to identify falsehoods by comparing religions through the scientific methods of ethnology, linguistics, philology, and historiography, as well as critical theological refutation. The Third Provincial Council of Goa further instructed missionaries to expose the “religious errors” and “lies” of idolatrous authors and the Satanic and historical origins of early Christian and pagan books, and to revise or burn such works. Converts to the “true” faith received new books printed by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries (ibid.: 140). Thus, from the very beginning, printers of Tamil books cast the authority of Tamil and other Christian authors in a dubious light.

With regard to linguistic irregularities, the Portuguese Jesuits were of two minds. Most agreed that studying Latin, considered the most perfect language, would ultimately reveal the universal laws of grammar, yet they also identified Portuguese, the lingua franca of Catholic missionaries working in Asia, as an especially elegant language made perfectible through the close influence of Latin (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015; Županov Reference Županov1998). Tamil, on the other hand, was deemed “theologically deficient,” “phonologically barbaric,” “laborious,” and “difficult” to learn. Due to its perceived lack of conformity with Latin, the preferred language of Christian scripture and mass, Tamil appeared sinful and prone to producing misinterpretations on account of many mispronunciations and improper transliterations (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015). Overall, the Portuguese indiscriminately identified in Tamil signs of “linguistic excess” in a grammar that refused to succumb to universal laws, phonology that resisted graphic representation, and orthography and script that defied standardization (Županov Reference Županov1998). Some missionaries endeavoring to rectify Tamil's imperfections endorsed a process of “grammaticalization” that involved translating catechetical literature and Catholic concepts from Portuguese and Latin into Tamil (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015). Others, such as Henrique Henriques, trained “topazes,” or low-caste native interpreters, to teach a simplified Tamil that reflected Latin grammar at Portuguese schools, although critics later accused them of mistranslating the true message of God (Županov Reference Županov1998).

Xavier and Županov explain that as Catholic Orientalism gradually fed and merged “into other and later Orientalisms and scholarly disciplines,” Orientalists discredited earlier Catholic scholarship for having lacked “scientificity” and “objectivity” and “being too close to the ‘native’ point of view” (Reference Xavier and Županov2015: xxi). This critique underscores the fact that many adversarial Christian theologies and European political regimes were competing for influence in South India. For example, during the eighteenth century, as the Portuguese government withdrew its support for printing in Tamil (Blackburn Reference Blackburn2003), Paris overtook Rome as the European center of Orientalist scholarship, and in India Pondicherry became the archival repository for manuscripts written in Tamil (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015). After 1706, a new Danish press founded by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) at a Pietist Lutheran mission in Tranquebar dominated the book market by printing hundreds of Bibles, gospels, catechisms, grammars, dictionaries, and almanacs. These included the first Tamil translation of the New Testament, under the leadership of Bartholomaus Ziegelbalg (Bugge Reference Bugge1998; C.E.K. 1873; James Reference James2000; Neill Reference Neill1970).

While Jesuit priests at the rival Madurai mission denounced these Lutheran writings as being “full of errors against the true faith” and decried Ziegenbalg's poor command of “coarse Tamil” (Blackburn Reference Blackburn2003: 51), Lutheran missionaries forcefully responded by objecting to the indulgent and sinful writing of Tamil poetry by Madurai's preeminent Italian Jesuit priest, C. G. Beschi. In addition to penning the celebrated Tembavani poem (1726), Beschi authored two grammars, one focusing on common Tamil (Reference Beschi1728) and the other on literary Tamil (Reference Beschi1730), as well as several dictionaries in Tamil, Portuguese, French, and Latin. Since the Madurai mission had no press, Lutheran scholars in Tranquebar printed Beschi's common Tamil grammar without his permission in 1738, and British officials later published the literary Tamil grammar as an English translation in 1822 (Chevillard Reference Chevillard1992). As the most widely consulted books printed in Tamil up until 1850, these grammars confirmed Beschi's fame as a preeminent author of Tamil literature and scholar of linguistics. Yet they yielded greater profit and political influence for the Lutheran, French, and British printers who controlled their reprints, translations, and access to faraway markets (Vinson Reference Vinson1903; Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015).

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the study of Sanskrit rather than Tamil preoccupied the interests of “scientific Orientalists,” most of whom were working in French, German, and British academic institutions. They devalued earlier Catholic works as plagiarized texts falsified by the prejudices of Indian converts-cum-informants, and they further defamed Portuguese translations for being written in a colloquial or impure style of Tamil (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015; Županov Reference Županov1998). British scholars went a step further and questioned the basic veracity of Catholic texts, which they described as being “full of errors and coming from an ‘earlier’ period or stage in the development of ‘sciences,’ wrapped in the blinding mantle of popish trickery” (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015: xxxiv). By re-conceptualizing Catholic texts as raw data devoid of scientific analysis and stripped of the virtues of authorship, the British justified their simultaneous defamation, plagiarism, and reanalysis of Catholic sources, employing the supposedly more scientific and accurate tools of statistics and surveys popularized by the Raj. At the same time, Indian pandits, influenced by European philological studies, printed instructional primers and textbooks in Tamil and English that reoriented the goals of education toward the acquisition of grammar and away from precolonial conventions such as oral elicitation and text memorization (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2009). With schools, presses, and books all promising to perfect Indian grammars, British officials cast Indian scribal traditions as producing relatively backward texts that “swarmed with errors” (Cohn Reference Cohn1996: 55–56; see also Blackburn Reference Blackburn2003; Trautmann Reference Trautmann2006).

It is important to note that plagiarized copies or mistranslations counted as sources of error only when perceived as being linked to adversarial theologies or anti-colonial activities. Hence, when the British began printing Tamil books in the early nineteenth century they limited their patronage to Beschi's canonical grammars and an ethnological study, Hindu Manners, Customs, and Ceremonies (1906 [Reference Dubois1816]), written by the Frenchman Jean-Antoine Dubois. He had resided in the British-controlled Madras Presidency and is now believed to have plagiarized this text as well (Trautmann Reference Trautmann2006). The British were generally ignorant of grammars and dictionaries printed by the Portuguese, German, Danish, and Dutch (Moussay Reference Moussay and Weber2002; Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015). Threatened by the lurking menace of French Revolutionary activity in Europe and India, they had imposed tough censorship laws in the late eighteenth century (Raj Reference Raj2000) and prohibited Christian evangelization in British territories until 1819. During this period, Christian missionaries could only consult Tamil books stored in libraries in Goa, Tranquebar, and Pondicherry, but not Madras (Bugge Reference Bugge1998). In the 1830s, British officials also required Indian-owned presses to send the names and addresses of their printers, and copies of their publications, to be reviewed for possible seditious content against the Raj (Venkatachalapathy Reference Venkatachalapathy2012).

In a catalog reviewing recently published Tamil books, British literary agent John Murdoch bemoaned that there were so few texts registered with the Madras office and the lack of trustworthy information about Indian authors, and then offered a dismal assessment of Tamil scholarship as essentially void of truthfulness and standards of accuracy (Reference Murdoch1865: lxvii–ix). Murdoch also included a figure (see figure 1) in which he arranged samples of reputable European-cut Tamil types in chronological order, starting with those fabricated in Halle in 1751 and finishing with those cut by the American Mission Press in 1865 (Blackburn Reference Blackburn2003). He did so to insinuate a narrative of technological and stylistic progress (Murdoch Reference Murdoch1865: lviii). In contrast, Murdoch categorized samples of Indian types using ahistorical and judgmental terms such as “bad,” “medium,” and “good” (ibid.: lix) that connoted an overall substandard quality. This “chronotopic” (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2005) contrast between the progressive, international orientation of European Orientalists and the ahistorical, parochial orientation of their Indian counterparts illustrates how interdiscursive retellings of the aesthetic and technological properties of Tamil types and fonts reaffirmed the image of a powerful British Empire. It is no coincidence that at this time Indian-owned presses were out-competing a once-thoroughly-European printing enterprise.

Figure 1. Comparison of European and native-cut Tamil types. From John Murdoch, Classified Catalogue of Tamil Printed Books, with Introductory Notes (Madras: Christian Vernacular Education Society, 1865), lvii–lix.

This brief history of European contributions to Tamil colonial linguistics reveals the naturalization and institutionalization of a belief that religious falsehoods could function as criteria for evaluating linguistic irregularities as types of scientific error, and vice versa. This ideology gradually took shape from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries and also implicated the metalinguistic labor of rival imperial powers and missionary orders, but it required French input to be transported abroad. French officials and Catholic missionaries added to the corpus of bilingual dictionaries and grammars featuring Tamil and European languages, and thereby cemented their legacy in India despite the colony's failing prospects.

LEGACIES OF TAMIL BOOKS IN FRENCH INDIA

Like the Portuguese and British before them, French travelers, missionaries, and scientists commonly consulted and plagiarized from earlier Catholic texts without citing their European or Indian authors (James Reference James2000). They faced British disparagement for emulating the Catholic model of imperialism that linked commerce with conversion, but the British still considered the French a step above the Portuguese for emphasizing the “‘scientific’ side of the enterprise” (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015: 305), and they recognized the good reputation French scholars enjoyed in the field of Tamil colonial linguistics. Animesh Rai, writing appreciatively of French imperialism in India, states: “The French had succeeded, better than any other nation, in earning the loyalty of Indians while still respecting their traditions” (Reference Rai2008: 77). Contemporary Tamil scholar Joseph Moudiappanadin, who teaches at the Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientale in Paris, also pays “special tribute … to the MEP missionary fathers who published manuals, dictionaries, and other books of great value to make known the Tamil language and culture to the French public” (Reference Moudiappanadin and Weber2002: 281). The fame enjoyed by the two printers Abbots Louis-Savinien Dupuis and Louis-Marie Mousset, and the relative lack of recognition given the military officer Amédée BlinFootnote 2 or other anonymous authors who handwrote vocabularies and dictionaries in Tamil and French, suggests that nineteenth-century technological changes instigated ideological shifts in religious and linguistic conceptions of error.

The first sub-section below analyzes the metalinguistic labor involved in handwriting vocabularies and other textbooks. My intent is to examine the consequences of secular French officials uncritically adopting the erroneous Jesuit practices of conflating Tamil and Malayalam as “Malabar” languages and presuming a close relationship between Tamil and Sanskrit or Hindi. A second sub-section will discuss how new Tamil presses and types in French India accentuated the pedagogical value of metalinguistic texts intended to counter the “false” theology of Protestant missionaries and cultivate readers’ morality. A final sub-section reveals how a quasi-religious ideal of perfectibility accompanied the circulation of dictionaries, grammars, and religious texts across both secular and non-secular contexts, and how it authorized a colonial ideology of “error” and framed colonial immigration and educational policies as either successes or failures.

Tamil Books in French India, 1800–1840

“French India” was founded by a royal charter from King Louis XIV in 1664 granting the French East India Company (Compagnies des Indes orientales) permission to establish trading outposts along the coast. It encompassed almost two-thirds of South India during its peak years from 1742 to 1754 before being labeled a failed empire (empire manquée) (Sen Reference Sen1971; Subramanian Reference Subramanian1999). Ultimately, the British vanquished the French in India, starting with their first military conquest in 1763, which forced King Louis XV to relinquish his imperial ambitions in the subcontinent. A second, in 1814, required France to recognize England's complete “sovereignty over the Indian possessions of the East India Company” (Sen Reference Sen1971: 598). Despite these setbacks, the French continued to antagonize the British by forging secret alliances with princely states, converting Hindus to Catholicism, propagating Republican critiques of colonialism, promoting the French identity and citizenship of high-caste, elite Catholics of European, Indian, and mixed race ancestry (Carton Reference Carton2012), and advancing the Orientalist study of Tamil language and society (Vinson Reference Vinson1903).

French scholarship of India was known as Indology, an academic field pursuing the scientific exploration of universal history by comparing the so-called great civilizations of the world (Sauvé Reference Sauvé1961). It was deeply rooted in Catholicism, having borrowed from the early seventeenth-century writings of the Italian Jesuit missionary Roberto de Nobili (Murugaiyan Reference Murugaiyan, Kremnitz and Broudig2013). Indology's comparative goals meshed well with the Jesuit mission to adopt a “transnational (Christian) identity” and forsake country, nation, and family for God (Županov Reference Županov2007: 95). As we might expect, the most notable eighteenth-century French Indologists were also Jesuits priests, including Jean François Pons, Jean Calmette, and Gaston-Laurent Cœurdoux, all acclaimed for their “scientific” studies of Sanskrit (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015). Most French Indologists’ quests for universal history translated into a preference for studying Sanskrit texts over Tamil language and literature, which were perceived to be more parochial (Filliozat Reference Filliozat1953; Sauvé Reference Sauvé1961; Murugaiyan Reference Murugaiyan, Kremnitz and Broudig2013: 5). At an Orientalist conference held in Paris in 1873, only one panel focused on Dravidian languages. Secretary to the French Delegation M. Duchâteau afterward stressed in a report the value of studying Tamil and Telugu for advancing the scientific study of philology, ethnography, and ancient history. He controversially claimed that Dravidian languages were autochthonous to pre-Aryan India and insisted that a permanent chair of Tamil studies be instated in Paris to train magistrates, bureaucrats, missionaries, and merchants and promote Orientalist studies in general (Murugaiyan Reference Murugaiyan, Kremnitz and Broudig2013: 6). Julien Vinson, appointed the first chair of Tamil studies at the École des langues orientales in 1885, regretted that Dravidian languages were “almost completely unknown” to the French and so knowledge of them could not be used to promote commerce, advance the pure sciences, or improve the careers of officials and tribunals in French India, Bourbon (Réunion), the Antilles, French Guiana, and Cochinchine and Tonkin (Vietnam) (Vinson Reference Vinson, Hovelacque and Vinson1878: 83–84, quoted in Murugaiyan Reference Murugaiyan, Kremnitz and Broudig2013: 886).

Linguistic assimilation was common practice throughout the French Empire, but French India was unusual in that colonial officials there more-or-less neglected French at the expense of Tamil (Rai Reference Rai2008). Although the French Capuchins who first settled in India in the late seventeenth century had denounced learning Tamil on religious grounds and counseled Europeans and Creoles living in Pondicherry exclusively in French, they were soon joined by members of the Paris Foreign Missions (MEP) who actively learned Tamil so as to communicate with their Eurasian and Indian parishioners (Bugge Reference Bugge1998; Matthew Reference Matthew and Weber2002; Neill Reference Neill1984). French Jesuits working in nearby Madurai, following the example of the mission's founder Roberto de Nobili, studied Tamil as well and also adhered to Hindu caste distinctions and adopted certain Brahmanical practices such as vegetarianism. In 1691, King Louis XIV ordered the Jesuits to establish a Carnatic Mission in Pondicherry to oversee the evangelization of all of French India (Matthew Reference Matthew and Weber2002). Together with the Capuchins and the MEP, these clergymen transformed Pondicherry into “a place of incredible missionary and intellectual effervescence” during the eighteenth century (Xavier and Županov Reference Xavier and Županov2015: 305) despite a shortage of native priests and persistent conflicts over the observance of caste. While the Jesuits formally accepted caste, the Capuchins vehemently denounced it and the MEP only tolerated it (Bugge Reference Bugge1998; Neill Reference Neill1970). When King Louis XV in 1764 and then Pope Pius VI in 1773 suppressed the Jesuit order for adopting Hindu manners and condoning the caste system, the MEP put aside their differences, welcomed them into their order, and let them evangelize in French India until the Pope restored them in 1814 (Matthew Reference Matthew and Weber2002; Neill Reference Neill1970).

Revolutionary ideas infiltrating the Indian colony soon obliged missionaries to make further concessions to civic, and not just religious, duties and take oaths of liberty and fraternity to a newly secular French government (Bugge Reference Bugge1998). Starting with the founding of the Seminary in Pondicherry in 1790 and Collège Royale in 1826, the French provided higher education to high-caste Indians, many of whom trained to become priests. Classes were offered in Latin, church history, and philosophy using Latin and Tamil (but rarely French) books (Annoussamy Reference Annoussamy2005; Bugge Reference Bugge1998; Neill Reference Neill1970; Rai Reference Rai2008). The French lagged further behind their British adversaries in Madras in the field of primary education. Between 1827 and 1870, they slowly established Tamil vernacular schools for European, métis, and topaz Christians, and later for Malabar and Pariah Hindu children (Bugge Reference Bugge1998). Although British schools sought to eradicate caste inequalities, French schools focused on the implicit Catholic mandate rather than social reform, and they zealously restricted bilingual English and Tamil books that espoused Protestant theology (Rai Reference Rai2008). Hence, on 17 August 1843 the governor denied permission to Reverend Bachelor, an English missionary living in Negapatam, to open an English-Tamil school in Karaikal on account of his problematic religious, rather than his linguistic, affiliation (Governor General of Pondicherry 1843).

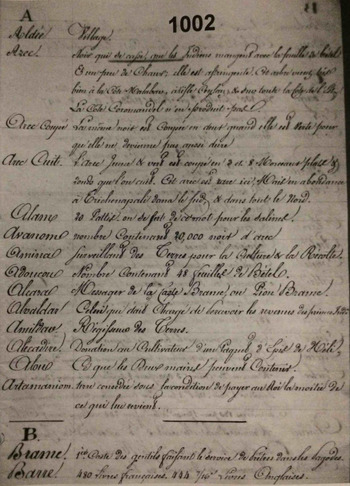

Prior to the expansion of primary schools, civil servants and elected officials in French India had acquired competence in Tamil or French through individual study or private tutoring and eagerly sought out texts to assist in this regard, including rudimentary vocabularies prepared by anonymous colonial officials. On 1 September 1825, a ship captain sent to the governor of French India a handwritten list of 168 “Malabar” (that is, Tamil) words spoken in Karaikal and their French translations (Explication 1824–1825). The vocabulary itemized the proper names of select castes and villages and common names of foodstuffs, measurements, administrative posts, agricultural items, soil types, and spices, and ethnological terms. It included no religious terms and highlighted only the secular and administrative concerns of colonial linguistics in French India. Moreover, although labeled “mots malabares” (Malabar words), not all the entries were actually in Tamil. Some, such as “boys,” defined as domestic coolies who carry palanquins, originated from English; others such as “Chenglai,” defined as Christian sailors native to Ceylon, came from a dialect specific to Karaikal (see figure 2). In 1830, a shorter vocabulary featuring twenty-nine words spoken in Pondicherry and Chandernagore included terms of unspecified Tamil, Bengali, and foreign origins (Relevé 1830). Several such words also appeared in the preceding Karaikal vocabulary, including “aldées” (village), “chelingues” (boats for embarking and disembarking), and “maniagar” (a person who collects duties in the market). This duplication of terms draws attention to an interdiscursively constituted contact zone connecting three of the territorially non-contiguous departments of French India, and also hints at the limited scale of documents written in unfamiliar francophone orthography in targeting broader European and Indian audiences.

Figure 2. Vocabulary of Malabar words used in Karaikal. Courtesy of Archives Nationales d'Outre-Mer.

Other officials seeking textbooks were aspiring interpreters participating in the “Children of Language Institution” (Institution des enfans de langue) established in 1827 by Governor Desbassyns. Modeled on a similar British competition, this institution offered small monetary prizes and employment incentives for lower-level bureaucrats in the tribunal and police to demonstrate their mastery of Tamil and other local vernaculars (Rai Reference Rai2008; Trautmann Reference Trautmann2006). The governor dismantled the program in 1838, officially due to high costs, insufficient results, and the growing availability of bilingual Indians educated in vernacular schools. However, in a private letter he expressed his disappointment to the minister of the Navy and Colonies that the program had mostly benefited Indian-born “creole” residents of disputed European descent rather than the intended European-born white residents and, moreover, had worsened caste tensions by letting Pariahs participate alongside the higher castes (Minister 1857). To meet the demand for books during the institution's short-lived operation, the lieutenant of a French battalion of cypahi (Indian infantry) soldiers, Amédée Blin, wrote to the minister of the Navy and Colonies on April 3, 1831 offering to sell copies of his self-authored French-to-Tamil dictionary, which he claimed was the first of its kind to be printed in France (see figure 3). Blin explained that he had written the dictionary to help the cypahi learn French and French officers to learn Tamil, but he also recognized the book's relevance for the enfans de langue, the tribunal, Collège Royal students, merchants, and Orientalists studying Indian theological texts written in Sanskrit, which he described as “the language from which Tamil was derived” (Blin Reference Blin1831). The minister concurred that, apart from the enfans de langue, members of the cypahi and Europeans living in French India would benefit from such a dictionary, and he sent the governor twenty copies (Minister 1831) and forwarded others to Garcin de Tassy, Professor of Hindustani at the École spéciale des langues orales, Jouamin, secretary-interpreter of the King for Oriental languages, Secretary of the Asiatic Society E. Burnouf, and M. Richy, a judge in Chandernagor (Director 1831).

Figure 3. Tamil-Malabar dictionary by Amedée Blin, Reference Blin1831. Courtesy of Archives Nationales d'Outre-Mer.

Figure 4. “Sipahy” written in Turkish (Turc) and Tamil (Malabar). Courtesy of Archives Nationales d'Outre-Mer.

Several metalinguistic labels sought to capture the title of this dictionary, including “Malabar-French,” used by Blin himself, “Tamil” by Garcin de Tassy, and “Malabar,” “Tamil-French,” and “French-Tamil” alternatively by the minister. “Malabar” was coined by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, and according to French Indologists referred indiscriminately to the languages, scripts, and peoples from both the Malabar and Coromandel coasts of India (Cohn Reference Cohn1996: 33; Murugaiyan Reference Murugaiyan, Kremnitz and Broudig2013).Footnote 3 Despite their preoccupation with eradicating scientific errors in colonial linguistics, prominent French Indologists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries produced handwritten texts and correspondences that incorrectly conflated the Tamil and Malayalam languages as “Malabar.” They also mistakenly presumed a close relationship between Tamil and Sanskrit or Hindi. For example, upon receiving a copy of Blin's dictionary, Garcin de Tassy informed the minister that Blin was able to easily learn Tamil in India after attending his Hindi class in Paris for several months (de Tassy Reference de Tassy1831). Perpetuating this confusion about language families, on 24 December 1834 the minister of the Navy and Colonies received a letter from the governor of French India who deplored the poor knowledge of Tamil possessed by the Collège Royale's Muslim teacher of Hindustani—his “imperfect command of the Malabar language”—and then requested additional books for students to teach themselves Hindustani (Governor General of Pondicherry 1834). The minister obliged and sent a copy of Garcin de Tassy's recently published grammar, Corrigé de thêmes hindoustany, which by its title alludes to the existence of prior, “erroneous” Hindustani grammars. It was printed by Albert Kazimirski, a Polish Orientalist who authored an Arabic-French dictionary in 1860, and it featured a “trendy Oriental typeface,” for which reason it was well-received by the British in Madras and Calcutta and the French in Pondicherry (Director 1837).Footnote 4

Such publicity tactics provide scholars with a rare view of colonial French attitudes toward Hindustani, an Indo-Aryan language seldom spoken or heard in French India. These correspondences further highlight a contrast between the reception of handwritten and printed texts in Tamil. They suggest a high degree of compatibility between the administrative concerns of the French colonial government and the scientific and religious interests of Indologists and missionaries who authored bilingual grammars and dictionaries in Tamil and other Indian languages. Generally speaking, French scholars did not regard knowledge of Tamil and Sanskrit or Hindustani as diametrically opposed until the latter half of the nineteenth century. Instead, lexicographies in French, Tamil, Hindustani, and Bengali postulated different ideas about language origins, possibly before news of the “Dravidian proof,” published by Sir Francis Ellis Whyte in Madras in 1816, had spread to Pondicherry (Trautmann Reference Trautmann2006). The subsequent rise of comparative philology required higher standards of perfectibility for metalinguistic scholarship.

Tamil Books in French India, 1840–1911

The next phase in Indology in French India brought a renewed focus on Catholicism and its weeding out of heresy and disproving of Protestant claims, a stronger commitment to publishing in Tamil, and the introduction of new printing technologies in Pondicherry. Clément Bonnand, the Vicar Apostolic of the MEP from 1833 to 1861, successfully shifted the Catholic Church's attention away from caste issues toward infrastructure, education, and media investments by founding more than a hundred churches and a seminary college, library, and printing press (Moussay Reference Moussay and Weber2002: 335). In 1844, Bonnand also convened the First Synod of the Apostolic Vicariate of the Coromandel Coast to “decide what would be the best for the good of the Missions.” Chief among the priorities listed were to educate Indian boys and girls, train native priests, expand the congregation, and print Catholic books in Tamil. In 1845, eighty-three thousand of the eight million Christians living in India were Catholic, including twenty-four missionaries, five native priests, 102 catechists, and 164 sacristans. To train additional Indian priests, the Seminary in Paris sent twenty-nine European missionaries to Pondicherry between 1831 and 1848, and another forty-three from 1847 to 1861. Arriving with these reinforcements were Abbots Louis-Savinien Dupuis and Louis-Marie Mousset, who had previously corresponded with Monseigneur Bonnand about India's caste issues and cultural differences between the Malabar and Coromandel coasts (Matthew Reference Matthew and Weber2002).

In 1840, with a letter of permission from the Vatican and moveable Tamil types in hand, Dupuis was appointed director of the first Tamil press in Pondicherry. Previous presses in this French colonial city, including one stolen by the British in 1762, had printed Catholic texts using Roman types (Murdoch Reference Murdoch1865). When Bonnand wrote a catechism in 1837 he had to have it printed at a foreign press and at considerable cost to the MEP. The same was true of a catechism and a booklet to refute heresy written by Father Charbonnaux, and A Treatise on Religion by Father Bigot Beaucian (Moussay Reference Moussay and Weber2002). Unsurprisingly, apart from the Catholic annals, there is little mention of these books. Similarly, few historiographies have acknowledged the existence of an earlier French-Tamil dictionary written by Father Louis-Noël de Bourzès, a missionary who lived in Madurai from 1710 to 1735 (Filliozat Reference Filliozat1953) and gifted his handwritten text to the king of France in 1734 (James Reference James2000: 115; Sauvé Reference Sauvé1961: 2442). Dupuis's first act as printer was to publish two books that he had authored in Tamil denouncing Protestantism (Dupuis Reference Dupuis1863). He also began to write a Tamil-English-Latin-French dictionary, but abandoned this ambitious project to collaborate with Mousset, director of the Seminary, on a Tamil-French dictionary, publishing volumes one in 1855 and two in 1862 (James Reference James2000). Jean Filliozat (Reference Filliozat1953) has argued that Dupuis and Mousset's lexicography contributed substantially to the twelve-volume Tamil Lexicon printed by the University of Madras in 1923, and borrowed freely from Bourzès’ dictionary, which they cited along with a few works by Beschi, Rottler, Spaulding, and Gury (James Reference James2000: 94). As I have said, Catholic writers rarely charged each other with plagiarism and claimed to care less about personal fame than gaining glory for God (Moussay Reference Moussay and Weber2002).

Dupuis and Mousset also published a newspaper in Reference Dupuis and Mousset1855 that featured on its front page a book inventory of religious treatises promoting Catholicism and refuting Lutheranism and Protestantism, in addition to spiritual exercises, catechisms, prayers, meditations, lives of saints, and litanies, as well as poetry, almanacs, and alphabet books written in Tamil and French with fables and advice for children (Dupuis Reference Dupuis1855b). Among the metalinguistic works were an abridged French-Tamil-Latin grammar and a Tamil-Latin grammar, a Latin-French-Tamil dictionary, a French-Tamil vocabulary, and a book of easy lessons in French and Tamil. Reproduced in a separate catalog, this inventory contained specific information about each book's size, price, intended use, and exceptional characteristics. For example, Dupuis and Mousset declared that their self-authored Tamil-French dictionary, printed in two volumes to accommodate ethnological details on Indian sciences, arts, and mythology, was more thorough than were competing dictionaries (Governor General of Pondicherry 1863b). It stressed the perfection attributed to Mousset and Dupuis's Latin-French-Tamil dictionary (Reference Dupuis and Mousset1846) for its avoidance of the grammatical and typographical errors common in Latin-French dictionaries: “Latin-French-Tamil Dictionary, 8 inches bound, 10 fr, the dictionary has the advantage of reforming an enormous irregularity that you generally find in dictionaries in France regarding the way they use verb tenses, the way they use noun classes and adjectives” (Governor General of Pondicherry 1863b).

Dupuis and Mousset also emphasized the pedagogical function of their books, highlighting a French-Tamil vocabulary and a French-Tamil grammar meant to replace Beschi's Tamil-Latin grammar and teach Tamil to French officials. In addition to a Tamil-French grammar intended to teach French and a Tamil-Latin grammar designed for teaching Latin, they indicated an abridged Tamil grammar that could be used to teach Indians the rules of their native language:

Tamil-Latin Grammar to teach Latin to natives, 12 in. hardback, 1 fr 80. French-Tamil Grammar, 12 in. bounded 3 fr 60. It was just published as a replacement for the Tamil-Latin grammar of Father Beschi, which was not answering the needs of the Colony. It is intended to teach Tamil to Europeans, etc.

Tamil-French grammar called Prangdilaccanasourcam, 12 in. hardback 1 fr 50, it is used to teach French to natives.

Abridged grammar entirely in Tamil called Flaccanaculadaram, intended to teach the rules of their language to natives, 12 in. hardback 1 fr 60 (ibid.).

The catalog was written largely in the passive voice and downplayed the status of authors (who were not always mentioned) to point out works published by Dupuis and Mousset or sponsored by the “Colony.”

These metalinguistic comments did more than simply describe the language of texts; they interdiscursively constructed a chronotopic contrast that elevated the progressive, global vision of Catholic theology and French imperialism above that of their European competitors. For example, two columns on the right-hand side of the newspaper's front-page juxtaposed biblical passages printed with Tamil types that had been recently fabricated by the MEP press with older (anciens) ones of undisclosed origins (Dupuis Reference Dupuis1855a; Reference Dupuis1855c) (see figure 5). Dupuis (Reference Dupuis1855a) proudly explained in a separate letter that the colonial administration had requested that these types be sent as models to the World Expo in Paris in 1855. He later wrote regretfully that he lacked money to fabricate newer ones to further improve the typeface: “…we had already melted the types and trained the typesetters to give these types the desired proportions to make them more pleasant to the eye and durable, however we have not been able to renew them often enough to have cleaner publications” (Dupuis Reference Dupuis1863). The governor highlighted this imperial victory in a letter to the minister of the Navy and Colonies, stating, “English experts who saw such a clear and easy victory, instead of the confusion that existed previously, were amazed, and it is no doubt that this reform will be soon introduced among their ranks, and I reckon that France will take the same path of making major improvements and reforms to typography, which originated with one of its subjects and colonies” (Governor General of Pondicherry 1863b).

Figure 5. Comparison of Tamil fonts in newsletter printed by Missions Étrangères de Paris (1855). Courtesy of Archives Nationales d'Outre-Mer.

Mousset and Dupuis declared in the preface to the second volume of their Tamil-French dictionary that it was the most complete to date (Reference Mousset and Dupuis1862: v) and specified that the second edition surpassed Indian, British, and other French dictionaries plagued by copyist errors (Reference Mousset and Dupuy1895: v). To further distinguish French scholarship written in Tamil, de Bourzès (Reference de Bourzès1734) and Baulez (Reference Baulez1896) each attempted to codify a French-based orthography to transliterate Tamil sounds into Roman script. They rejected common British, Portuguese, and Indian conventions to write, for example, உ as < ou > rather than < u > or <oo>, ஆ as <á> or <â> rather than < aa > or <ā>, and ழ ழ as < J > rather than < zh> (see figure 6) (James Reference James2000: 115). Since Mousset and Dupuis's dictionary entries were printed in Tamil and not transliterated into Roman script, they avoided entirely the semblance of orthographic irregularities (see figure 7). Also in the preface to their Tamil-French dictionary reprinted in 1895, the authors stated a preference for using a “High Tamil” orthography, which they believed to be purer and more ancient than the “Low Tamil” version (Reference Mousset and Dupuy1895: xxii). Finally, despite differentiating between tamoul vulgaire and tamoul poétique, they described these varieties as part of a linguistic continuum “not distinguished by absolute markers that are stark enough for us to separate them in a dictionary without causing frequent difficulties for those who study one or the other” (ibid.: v). Unlike British and Jesuit scholars, Mousset and Dupuis (and also de Bourzès) combined entries from both varieties.

Figure 6. Tamil-French orthography in M éthode de Tamoul Vulgaire (Baulez Reference Baulez1896).

Figure 7. First page of the Dictionnaire Français-Tamoul, Seconde Édition (Mousset and Dupuis Reference Mousset and Dupuy1911).

Without the French colonial government's help in publicizing typographical and orthographic innovations originating from Pondicherry, such signs of national distinction would enjoy little recognition outside the scholarly circle of French Indology. On 17 February 1863, therefore, Abbot Dupuis wrote to the governor of French India to promote selected books. He began by stating that the minister of the Navy and Colonies had asked several years earlier, through the previous governor, if there were any books printed in Tamil or the “Malabar language” that could be sent to Guadeloupe or Martinique. After explaining that Europeans often mistakenly labeled the peoples and languages of both the east and west coasts of South India as “Malabars,” Dupuis stated that he had assured the governor that there were several books of interest, but also explained that his best dictionaries and grammars were still unfinished. In a second letter, Dupuis announced that his newly completed Tamil-French dictionary and French-Tamil grammar had been printed “for the good of the colonies” (pour le bien de nous colonies):

…but in order to let the metropolitan government decide if the products of our printing press, of which I am enclosing a catalog, could not be of use in learning Tamil in the various colonies where the many people who speak this language could render it useful for government officials; whether they would not be useful also for Tamil classes offered in Paris and paid for by the government, and, most of all, whether they could not be exceedingly useful in teaching and inculcating morals to the large number of immigrants who work in our colonies, nevertheless if his Excellency the Minister judged that the “good” this printing press produces deserves some encouragement, that would be welcome with gratitude and could contribute even more to the general good (Dupuis Reference Dupuis1863).

According to Dupuis's pedagogical vision, the books would not only assist European officials and Indians in learning their own and each other's languages, but also, by teaching them a perfected grammar, they would inculcate “good” morals in Indians.

He then mentioned that his press had distributed 140,000 books between 1840 and 1863 for free or at a modest price to counter the aggressive distributions of works by biblical societies: “However, being among a people who are generally very poor, and dealing with Protestant biblical societies that are handsomely rewarded for spreading everywhere at no cost and especially among our Christians erroneous books that are hostile to our faith, we find ourselves needing to give away our books at the lowest price, and even often to distribute them for free” (ibid., my emphasis).

That Dupuis referred to Protestant books as “erroneous” indexes his simultaneous condemnation of their rejection of Catholicism, misinterpretations of the Gospels, and use of incorrect Tamil grammar or poor-quality types. In a statement that alluded to multiple types of errors, Dupuis lamented that “the low wages we pay to our workers, who are only natives, do not permit us to have men skilled enough to do a perfect job.” He also bemoaned that the rare, expensive, and inaccessible books that discussed Christian religion and piety, and were handwritten on palm leaf manuscripts, were “full of errors” (remplis de fautes) (ibid.). Finally, he cited the lack of printed instructional materials available to teach Tamil to French officials attending the Seminary College and to French and Indian civil servants attending primary schools, and invited the minister to judge for himself how useful the books could be for French India and other colonies benefiting from Tamil immigration, including Ceylon, Mauritius, Réunion, Burma, Malaysia, Aden, and Hong Kong.

Dupuis closed by asking the governor to forward his letter, book catalog, and newspaper to the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs in Paris and to the governors of Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, and Réunion, who oversaw Tamil indentured migration. The governor heeded Dupuis’ request and soon wrote to the minister of the Navy and Colonies on his behalf:

My attention focused especially on the Tamil-French dictionary and grammar that was just published, important works long in the making that are due to the science and irrepressible zeal of two members of the Mission. After examining these works, I asked the Head Father if the colonies with Tamil-speaking immigrants have been informed of the resources that are being offered by such an institution, as much for easing relations between property owners and laborers as to guarantee the functioning of courts and tribunals. Since no positive response was given to me concerning this request, I asked to be given an update about this situation and the works of the printing press, as well as the book catalog that could be given either to the other colonies, Réunion, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Cayenne, or to the scientific institutions of the metropole (Governor General of Pondicherry 1863a).

This letter was the first to mention the “science and irrepressible zeal” of the MEP press in the same phrase, and target the “scientific institutions” of Paris as potential book subscribers. By translating Dupuis’ religious mission into a secular one, the governor employed publicity tactics carefully tailored to both the bureaucratic needs of an embattled imperial power and the scientific mission of French Indologists. Together, these letters articulated for the first time a semiotic ideology in which disparate signs of religious, linguistic, and scientific error could be read as iconic of one another, as well as indexical of the ebbing influence of French colonies. Dupuis had initially implied the opposite: French-Tamil grammars and dictionaries teaching a “perfected” European or Indian language in schools could potentially reform a failing colonial enterprise, improve interracial relations between European officials and Indian subjects, and better the moral and religious conduct of immigrants. Yet in his letter the governor failed to repeat Dupuis’ last point and mentioned only the utility of Tamil books for easing “relations between owners and workers [and] guarantee[ing] the functioning of courts and tribunals” overseas. Perhaps due to this omission, the governor's publicity efforts brought few subscriptions.

The minister was the first official to subscribe to the press and requested that a small shipment of books be sent to libraries in Paris and French port cities. These included the Dictionnaire tamoul français, Arithmétique tamoule, Grammaire française tamoule, Grammaire tamoule française, and Grammaire tamoule latine (Governor General of Pondicherry 1863c). Every year afterward, from 1864 to 1870, he received updated inventories and additional books. The Minister of Education and Religious Affairs ordered a single shipment of dictionaries (Dictionnaire tamoul français and Dictionnaire latin français tamoul), grammars (Grammaire française tamoule; Grammaire tamoule française dite francilacana sourcam; Abrégé de la grammaire toute tamoule dite Nouladaram; Grammaire tamoule latine; and Grammatica latina tamulia), vocabularies (Vocabulaire français tamoul), poetry (Tembavani), and fables (Garamartagourou), as well as evangelical texts, almanacs, and atlases. Yet he declined to purchase a subscription due to a lack of funds and an insufficient demand for Tamil books in Paris, where Indologists preferred Sanskrit books. Among the four governors the minister contacted, only French Guiana's ordered any: seventy-one books in 1863 and a smaller shipment in 1870. A “chest contain[ing] various works written in the Tamil language, published by the Pondicherry Apostolic Mission Press, and destined for the Guyanese colony as well as for the libraries of the Navy Ministry and ports of the metropolis” (Governor General of Pondicherry 1864), departed Pondicherry in 1863 and arrived in Bordeaux in February 1864, then left again in May 1865 aboard the ship L. Mauritius headed for French Guiana. It contained mostly metalinguistic texts, including a Tamil-French and Latin-French-Tamil dictionary, a French-Tamil vocabulary, a French-Tamil grammar, an arithmetic book, an alphabet book, and simple lessons in French and Tamil for novices. Less prominent was an assortment of almanacs, storybooks like Arabicide (“1001 Nights”), and Catholic texts like catechisms, lives of saints, and The Imitation of Christ. Although the book trail ends abruptly at this point, its subsequent trajectory can be gleaned from evidence regarding colonial policies of Indian immigration and religious and secular education in French Guiana, to which I now turn.

Tamil Books in French Guiana, 1863–1870

French Guiana, a former colony on South America's northeastern coast, was sandwiched between the more populous colonies of British Guyana and Dutch Surinam and overshadowed by the more prosperous colonies of the French Antilles, Martinique, and Guadeloupe. Its history has been described as a “misleading chronicle about colonial failure” (Spieler Reference Spieler2012: 3). Various efforts were made to render the colony profitable for France through settlement or immigration initiatives, and between 1789 and 1890 thirty thousand people arrived there as slaves, convicts, immigrants, or political criminals. Yet most initiatives either failed outright or never came to fruition. One involved recruiting spice cultivators to come from Asia in exchange for small parcels of land (Sahaï Reference Sahaï1989). In April 1819, Father Louis Sénégal suggested to the minister that Cholas from Ceylon, a caste known for cultivating cinnamon bark, and caste groups known for their farming of pepper on the Malabar Coast of India and Sumatra, might be desirable laborers for French Guiana because they were supposed to be patient, mild-mannered, and cheap to hire (Sénégal Reference Sénégal1819; Minister n.d.). The minister conveyed Sénégal's request to the governor of Cayenne. The idea was that a policy for the immigration of Indians, Ceylonese, and Sumatrans could be formulated once it was known which cash crop—pepper or cinnamon—fared best on Guyanese soil.

Financial and legal difficulties delayed this experiment in indentured servitude in French Guiana until African slaves were emancipated in 1848. Even then, the British denied the French access to cultivators living within the spice-growing regions of British-controlled Ceylon and the Malabar Coast of India for more than a decade (Northrup Reference Northrup1995; Samaroo Reference Samaroo and Hangloo2012; Spieler Reference Spieler2012). The French instead recruited Tamil speakers from Pondicherry, Karaikal, and Yanaon, colloquially known as “Malabars.” That led the minister to make a costly error: when he signed a treaty with the General Transatlantic Company in 1864 to bring four to six hundred Indians per year, he mistook rice cultivators, masons, shepherds, weavers, and servants from the Coromandel Coast for the desired spice farmers from the Malabar Coast (Traité 1864). Cajoled with promises of lucrative work opportunities or kidnapped aboard ships, 42,326 Indians migrated to Guadeloupe and 25,509 to Martinique between 1854 and 1889 (Vertovec Reference Vertovec1995). In 1855, the ship Sigisbert-Cézard ran ashore near the coast of Cayenne and eight hundred passengers, including Tamil-speaking laborers destined for Guadeloupe, found employment in French Guiana and sent the news back home (Sahaï Reference Sahaï1989). Subsequently, from 1855 to 1877, 8,472 men ages sixteen to thirty-six, women ages fourteen to thirty, and children migrated to French Guiana (ibid.).Footnote 5 Indo-Caribbean historians have made scant mention of this migration.

After an exhausting voyage of from 90 to 111 days, Tamil indentured laborers arriving in Cayenne were forced to sign contracts to work for 300 francs for seven years, 250 francs for five years, or 30 francs for one year, at nine hours a day and six days a week, in exchange for their annual salary along with basic clothing, food, lodging, and medical care (ibid.). Most preferred spice cultivation to gold mining and were undeterred by reports of squalid living conditions, high rates of depression and suicide, and a mortality rate of over 50 percent due to syphilis, beriberi, dysentery, and malaria in the interior plantations (Roopnarine Reference Roopnarine2003; Sahaï Reference Sahaï1989; Vertovec Reference Vertovec1995). In contrast with the Antilles, French Guiana's sparsely populated and dispersed forested settlements made it difficult for laborers to access medical care. Even the governor's belated proposal in 1876 that “two hospices should be built in the neighborhoods of Sinnamary and Mana plantations, where the laborers are more numerous and important” (Governor of Cayenne 1876), did little to improve conditions because he disregarded the British requirement to provide bilingual interpreters to assist doctors working in plantations or aboard ships (Governor of Cayenne 1874). In his opinion, “All coolies aboard the ship speak Creole and many of them understand French” (Governor of Cayenne 1877b). In 1877, the British terminated Tamil immigration to French Guiana on account of the high mortality rate and planters’ negligence. The governor briefly considered replacing Tamils with Annamite laborers, viewed as “superior to Indians, in every respect and notably from the standpoint of their ability to acclimate and their punctual execution of required tasks,” even though most spoke little French (Governor of Cayenne 1877a). This immigration policy also failed because the sole Annamite interpreter, M. Meyer, returned to France and could not be easily replaced by an “Annamite interpreter of European origin” (ibid.).

In 1885, 1,184 Tamil indentured laborers in French Guiana repatriated to India and another 184 relocated to Guadeloupe; among the 2,931 remaining in French Guiana after 1877, 448 had been born there (Sahaï Reference Sahaï1989). The descendants of Tamil laborers living in French Guiana have primarily converted to Catholicism and adopted English-lexifier or French-lexifer creoles as their lingua francas (Goury and Léglise Reference Goury and Léglise2005; Murugaiyan Reference Murugaiyan, Kremnitz and Broudig2013; Sahaï Reference Sahaï1989). This is in contrast to the descendants of laborers living in the former British colonies of Mauritius and Natal where Tamil is still spoken today (Northrup Reference Northrup1995), and the French colonies of Martinique and Guadeloupe where Tamil has become a liturgical language of Hindu worship, dance, and music (Desroches Reference Desroches1995; Muraigayan Reference Murugaiyan, Kremnitz and Broudig2013). It is likely that many first-generation Tamil children born in French Guiana learned to speak Creole and French at Catholic schools at the Mana and Sinnamary plantations, founded in 1832 and 1846, respectively, under the direction of the noted abolitionist leader Anne-Marie Javouhey (Delisle Reference Delisle1998; Puren Reference Puren2007; Roopnarine Reference Roopnarine2003; Spieler Reference Spieler2012).Footnote 6 Her congregation, the Sisters of Saint Joseph de Cluny, helped to overturn a 1685 law criminalizing literacy among blacks and established French-medium schools to teach the children of freed slaves religious and civic duties, reading, writing, and arithmetic, and, for the girls in particular, gardening, sewing, and bleaching (Delisle Reference Delisle1998; Governor of Cayenne 1841; Puren Reference Puren2007). The schools came under attack by colonial officials, and in 1842 the governor wrote of their problems with low enrollment, a shortage of well-trained teachers, and classes interrupted by inclement weather. In 1863, he considered the following recommendation to secularize the schools: “I have the honor of proposing to you the closing of the school run by the Sisters of St. Joseph at Sinnamary and to establish at this location a secular school according to the conditions dictated by the decision of March 27, 1860” (Governor of Cayenne 1863). Two and a half decades later, in 1888, all of French Guiana's schools became secular (Alby Reference Alby2009).

At the beginning of the secularization process, from 1857 to 1861, the governor purchased dictionaries and grammars printed in French and Latin as end-of-year prizes for students attending the Collège de Cayenne and Sinnamary school. In 1857, Collège students received Livres classiques and Geoffrey dictionnaire élèves re: français-latin, and in 1858 Langue latine, Grammaire latine, Dictionnaires élémentaires français-latin et latin-français de chacun, Dictionnaire français-latin et latin-français, Langue grecque, Manuel de verbes irréguliers, and Langue française. Between 1859 and 1861, the students at Mana school received a similar shipment. There are no administrative records of French and Latin books being shipped to French Guianese schools after this date. In 1863 and 1870 there were only Tamil and French books, including bilingual dictionaries, grammars, workbooks, catechisms, and Bible stories, sent by the MEP to French Guiana. Based on historical precedent and Dupuis’ pedagogical vision, the children of Tamil indentured laborers attending secularizing schools at Sinnamany and Mana likely received these books as end-of-year prizes. Perhaps they were intended to help them to learn French and Tamil grammar, or at least to adopt more virtuous Christian morals. Given the perilous state of Indian bodies, minds, and spirits toiling in the Guyanese interior, the notion that studying grammar would have a salutary effect on the children's moral constitution was akin to a belief popular among Catholic missionaries that learning the gospel would reform Indian immigrants’ souls. The Sisters of Saint Joseph de Cluny, who also established primary schools in French India, took this line. This idea that grammars and dictionaries could substitute for or enhance the gospel's work in perfecting Indian immigrant languages and morality highlights the far-reaching and longstanding repercussions of a semiotic ideology, and renders visible the work of interdiscursive processes in normalizing and institutionalizing European colonial power.

CONCLUSION