In January 1975, the journal Révolution Afrique published a rallying speech that the editors had addressed to hundreds of African workers at a meeting organized a few months earlier in Paris: “All behind the people of Guinea, Angola, Mozambique! Against the slavery policy of the French neocolonial government! Unity of African workers! Let's create action committees of African workers everywhere for a mobilization of the black immigration front! Angola! Victory! Mozambique! Victory! Guinea-Bissau! Victory! Immigration! Unity!”Footnote 1 Two photographs illustrated the page. The first, seemingly taken in Africa, portrayed an armed black soldier hunkered down on the sand. At the bottom of the snapshot a handwritten caption read: “soldier, producer, student.” The second image, most probably of a Parisian street, showed a rally of a racially mixed crowd. Demonstrators’ faces were masked by blindfolds superimposed on the photograph. The slogans were only partially legible due to poor print quality, yet two flags carried the easily recognizable symbol of defiance, resistance and unity—a raised fist—which also adorned the journal's front cover.

From its creation in 1972 until its last issue in 1977, Révolution Afrique was run by an eponymous group,Footnote 2 originally constituted as the African cell of the French radical leftist organization Révolution! in the aftermath of the French May ’68, which marked the beginning of a renewed political engagement of immigrants in France (Gordon Reference Gordon2012). Against a backdrop of increasingly restrictive immigration policies and rising Cold War tensions, its West African and French activists mobilized for political causes in both Africa and France until the group was eventually banned by the French government.Footnote 3 Influenced by Third-Worldism, Révolution Afrique's ideological basis was grounded in a Marxist critique of neocolonialist ideologies and policies as well as their interrelated exploitative dynamics “abroad” and “at home.” Its activists fought in France against the persistence of legal and racial discrimination and in favor of improving migrants’ living and working conditions. At the same time, they called for an end to one-party regimes in francophone African countries, denounced the support of France for military rule on the continent, supported independence for the Portuguese colonies, and later, the downfall of apartheid in South Africa.

In spite of a scholarship on the worldwide dimensions of youth protests in 1968 (Daniels Reference Daniels1989; Suri Reference Suri2003), and more recently in the French post-imperial space (Hendrickson Reference Hendrickson2013; Monaville Reference Monaville2013; Blum Reference Blum2014), the radical politics embraced in the late 1960s and 1970s by West Africans in France has been overlooked.Footnote 4 Révolution Afrique, whose declared goal was to forge revolutionary movements tying together both sides of the Mediterranean, embraced what we are now accustomed to think of as a “transnational” political agenda. Introduced in migration studies by anthropologists, transnationalism is defined as the processes by which “immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement” and that “cross geographic, cultural, and political borders” (Basch, Schiller, and Blanc Reference Basch, Schiller and Blanc1994: 7). The advent of this paradigm has allowed scholars to break free from “methodological nationalism” (Wimmer and Schiller Reference Wimmer and Schiller2002), paving the way for an investigation of the political participation of migrants in their sending and receiving countries (see e.g., Bauböck Reference Bauböck2003; Guarnizo, Portes, and Haller Reference Guarnizo, Portes and Haller2003; Martiniello and Lafleur Reference Martiniello and Lafleur2008) and the emergence of mobilizations across territorial boundaries (e.g., Matera Reference Matera2015). Based upon this scholarship, our study investigates the meanings of transnationalism in the historical context of post-imperial France. By examining the social, material, and temporal dimensions of activism by West Africans, we question the possibilities of, but also the limits inherent to, transnational political engagement. For this purpose, we scrutinize the ways in which pleas for revolutionary mobilizations in France and Africa materialized in concrete decisions and specific actions. In particular, we examine how Révolution Afrique covered political events on both sides of the Mediterranean, how news, written material, and individuals circulated from one activist scene to another, and ultimately which affective ties and intellectual frames allowed militants of the time to dream, think, and act in the hope of revolutionary upheaval in Africa and Europe.

Expanding the studies on the French May ’68 to take into consideration the circulation of ideas and militants across the post-imperial space requires innovative methodologies (Hendrickson Reference Hendrickson2017). Our study combines several distinct types of material. First, French administrative and police archives, which permitted us to reconstruct the legal and political context of the period. Second, militant material produced at the time, mainly the journal itself, which is a unique source that has not yet been thoroughly used. Finally, retrospective oral and written accounts, consisting of the memoir published by a central figure of the group, French activist Gilles de Staal (Reference Staal2008), and in-depth interviews that we conducted with African former group members as well as with other French and African activists.Footnote 5 Such a combination of source material paves the way for two analytical processes. On one hand, we have been able to engage in cross-checking. For instance, the journal offers various grandiloquent claims on the group's influence; other sources nuance these claims, but nonetheless provide convergent evidence that the group was involved in specific events and sites. On the other, certain sources offer new levels of intelligibility, notably the interviews, which shed light on the group's internal dynamics and help to understand its demise, an aspect that is a blind spot in the archival records.

The diversity of this material opens an approach that bridges existing scholarly divisions and disciplinary boundaries, more specifically the social history of postcolonial migrations and the intellectual history of leftism and Third-Worldism. As observed for the colonial period by Michael Goebel, the intellectual history of anti-imperialist movements is “more firmly rooted in [a social history of migration] than is commonly acknowledged” (Reference Goebel2015: 3). His study, devoted to the activism of non-Europeans in interwar Paris, pays attention to their sociability networks and their urban experience, as well as to the family histories that ultimately shaped their intellectual output and political stances at a time of rising national consciousness. This perspective, which captures the multi-layered social experiences of migrants, is integral to our study of the postcolonial period. Two comparative lines of inquiry shape our approach to the group and its boundaries. First, Révolution Afrique brought together migrants from various social backgrounds, particularly workers but also students, two social groups that still tend to be studied separately.Footnote 6 By promoting a strategic alliance between them, the group embraced a call for revolutionary unity that was an integral part of the 1968 social movements.Footnote 7 The extent to which this actually worked is an empirical question that our study attempts to answer. Second, in line with its internationalist stance, Révolution Afrique tried to develop joint actions with radical North African migrant organizations. The limited effectiveness of such consolidation highlights the lasting impact of different colonial histories into the post-imperial period.Footnote 8

In tracing back the rise and fall of Révolution Afrique in the second decade after decolonization we revisit and reassess established chronologies. Independence has long been understood as a defining moment for African migrations and the newly formed nation-states. However, this seemingly obvious chronology has recently been questioned, opening up a more refined reading of those historical trajectories. Scholars of African migrations to France have shown that the “decolonization of migrations” by the French government happened a decade later, with the beginning of a global economic crisis in the aftermath of the oil shock, and particularly with the official suspension of migratory flows in 1974 (Noiriel Reference Noiriel2007: 675). In parallel, historians of French West Africa have emphasized that this was the moment when West African migrants began to think of themselves as “foreigners” to France, and legal arrangements between France and its former colonies in matters of migration governance began to be uncoupled (Cooper Reference Cooper2014; Mann Reference Mann2015).

In exploring this intersection, we provide these studies, which are mainly based upon an analysis of public policies, with an additional perspective closer to the experience of the migrants themselves, notably documenting their hesitation toward the idea of a revolutionary-motivated return to Africa. We demonstrate how a transnational project could make sense among African workers and students until the early 1970s, but progressively ceased to be meaningful with the tightening of migration laws, the increasing repression of political dissent, and the French state's implementation of return policies in the late 1970s. These drastic changes forced them in the late 1970s to reevaluate their collective action and personal goals and to focus on more national agendas, thereby setting aside their transnational revolutionary project. Theoretically, we demonstrate that transnational activism cannot be taken as a stable frame of analysis. Instead, we show that it is always dependent on the positions of activists in their life cycles, the structure of political opportunities, and changing national and international contexts.

“GLOBAL 1968” AND ITS AFTERMATH

Scholars have conceptualized 1968 as “the culmination of previous years” and “the point of departure for the years to come” (Dirlik Reference Dirlik, Fink, Gassert and Junker1998: 296).Footnote 9 Such analysis is based on a consideration of the deep transformation of international relations, as well as the increasing cross-cultural exchange of people and ideas that came to challenge the “national demarcation” of borders and citizenships (Jobs Reference Jobs2009: 376). The case of the French “post-colonial historic bloc” (Bayart Reference Bayart2009: 193) offers decisive insights into this crucial period and the possibility of reevaluating the place of Africa and its diasporas in 1968's lives and afterlives.Footnote 10 The late 1960s and the following decade witnessed an intensifying intellectual and political connection between the fate of African societies and postcolonial migrants.

In terms of ideology, French intellectuals were at the forefront of Third-Worldism in Europe. The “Third World” concept, which had acquired a global relevance with the Asian-African Conference held in Bandung in 1955 (Berger Reference Berger2004), was forged by the French demographer Alfred Sauvy (Reference Sauvy1952) by analogy with the “third estate” of pre-revolutionary France. Much more than the “national” origins of this notion, the “heroic ideology” of Third-Worldism was the indirect result of critical encounters in Metropolitan France between “the Third World resident forced to endure the consequences of colonial rule” and “the Third World migrant worker or student confronted with metropolitan reality” (Malley Reference Malley1996: 18), which explains its impact on both French political and intellectual life in the 1960s. French thinkers and scholars strongly shaped Third-Worldism (Kalter Reference Kalter2016). The influential editor François Maspero published many of their works and translated significant foreign texts into the French language, while his bookstore La Joie de Lire, located in central Paris and close to the main universities, offered readers a wide range of journals and books (Hage Reference Hage, Artières and Zancarini-Fournel2008). Within this multilayered intellectual trend, anthropologists specialized in Africa challenged in particular the close military cooperation between France and its former colonies, as well as the choice of development programs initiated in the region by postcolonial governments under the aegis of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Cooperation. They also denounced the neocolonial influence that had led to increasing poverty in the region and to rising migration to postcolonial France (Copans Reference Copans, Bonte and Izard2000).

In terms of politics, France had seen a pronounced de-legitimation of the established left-wing parties during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962). This conflict was a pivotal moment in the redefinition of French political life (Shepard Reference Shepard2006). Under Guy Mollet's government (1956–1957), the Section Française de l'Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO) saw its political legitimacy eroded due to the declaration of the state of emergency and the repression of Algerian fighters. The Parti Socialiste Unifié (PSU), founded in 1960 in reaction to SFIO's hardline stance, became one of the left-wing political organizations most able to unify anti-colonial networks and to coordinate the engagement of French intellectuals and youths (Fisera and Jenkins Reference Fisera, Jenkins and Bell1982; Bertrand Reference Bertrand, Damamme, Gobille, Matonti and Pudal2008; Kalter Reference Kalter2016). Already weakened by the Soviet intervention in Hungary after the Budapest uprising of 1956, the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) lost further credibility due to its ambiguous position on Algerian independence since its leader Maurice Thorez backed the Mollet administration's request for emergency powers in March 1956 (Matonti and Pudal Reference Matonti, Pudal, Damamme, Pudal, Gobille and Matonti2008). Testifying to a generational and political transition, the alteration of the French political landscape accelerated with the emergence of radical movements. These groups included Maoist organizations such as the Union des Jeunesses Communistes Marxistes-Léninistes (UJCml) in 1966 and the Gauche Prolétarienne (GP) in 1968, as well as Trotskyist organizations such as the Ligue Communiste in 1969 and, following that organization's split, Révolution! in 1971. Révolution! emerged from a minority current inside the Ligue Communiste who found more appeal in the Chinese Cultural Revolution than did the organization's leadership (Salles Reference Salles2005: 101–2). Influenced by Third-Worldist ideologies, each of these radical groups developed recruitment efforts toward militants from former French colonies and protectorates, which led to collaborative actions of variable duration and scope.

As was the case with North African students (Hendrickson Reference Hendrickson2012), sub-Saharan students, who were politically active, benefited from the enduring legacy of the anti-imperial activism forged in colonial France and deeply reshaped in the wake of the “global 1968.” The Fédération des Étudiants d'Afrique Noire en France (FEANF), created in 1951, had acquired a prominent position in the anti-colonial struggles spanning sub-Saharan independence movements and the Algerian national liberation project. After decolonization, FEANF's position became more ambivalent and complex. The return of many of its former members to Africa and their appointment to senior positions in new governments led to repeated critiques of collusion with increasingly authoritarian regimes. Yet the continuing presence of French students in African universities and, conversely, of African students in French universities ensured the circulation and consumption of Third-Worldist literature, as well as the strengthening of direct connections and the framing of common causes between politicized youths scattered across different countries and regions.Footnote 11 This interrelationship is particularly evidenced in the occupation of the Senegalese embassy in Paris led on 31 May 1968 by Senegalese students active in the Parisian May against the repression of their counterparts in Dakar (Blum Reference Blum2012; Guèye Reference Guèye2017). Among them was Omar Blondin Diop (1946–1973), the Senegalese activist and student who played his own role in Jean-Luc Godard's La Chinoise (Reference Godard1967), a movie that portrayed a Maoist cell called “Aden Arabie.”Footnote 12

In 1968, and over the years that followed, left-wing organizations started placing postcolonial migrants’ working and living conditions on their agendas for the first time. The decolonization era had transformed West African migrations; it brought a rising number of unskilled workers to France and contributed to a diversification of the demographic composition of country's sub-Saharan population. The independence of the former French African colonies had led to multilateral agreements offering the freedom of circulation to Africans in order to preserve the economic and political interests of France in Africa, as well as to avoid “mass returns” of Europeans settled there (Viet Reference Viet1998: 279–95). A sharp rise in migratory flows to France can be observed in the aftermath of the decolonization process: the sub-Saharan African migrant population multiplied by a factor of almost ten between 1954 and 1962 to reach around eighteen thousand (Dedieu Reference Dedieu2012: 24–25), the vast majority of whom came from a small area of the Senegal River Valley at the junction of Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal (Manchuelle Reference Manchuelle1997).

Most of the migrants were hosted in dormitory-style facilities subsidized by the French State, called “foyers” (Diarra Reference Diarra1968). Despite an economic context marked by strong growth and full employment, the living and working conditions of West African migrants were dire. These conditions provided a new opportunity for radical movements to denounce and challenge the monopoly of the PCF and the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) union over the working class at the local and national levels, particularly in the “red belt,” the string of communist municipalities around Paris where many migrants lived (Stovall Reference Stovall1989).

The social trajectories of students and workers became increasingly blurred from the late 1960s, particularly from the next decade onward. Many African students experienced a significant loss of social status compared to their peers from the preceding imperial era. African governments started to reduce their scholarships due to the looming economic crisis in West Africa, while the most authoritarian regimes fully eliminated them in order to curb student dissent. Furthermore, the crisis faced by the African public sector, in which many students sought to work at the end of their studies in France, led them to abandon or postpone their plans of returning to Africa and instead look for jobs in a France at grips with conspicuous racial discrimination. For low-skilled workers, the situation was to a certain extent the reverse. Though many of them had arrived in France illiterate,Footnote 13 some began enrolling in literacy programs set up by local associations, charity organizations, and radical leftist groups. A few even embarked on vocational education that proved important for their upward social mobility. As a result, the distinction between these two categories, often emphasized in scholarship, became less relevant.

Foyers that were built to house workers also occasionally hosted students. These spaces constituted the main site for the politicization and recruitment of West African activists into radical leftist organizations (Dedieu and Mbodj-Pouye Reference Dedieu and Mbodj-Pouye2016). The latter worked at developing political activities in the foyers through literacy classes and cultural events and West African migrants increasingly became part of these movements. That said, their engagement in radical politics cannot be solely attributed “to the after-effects of May 1968,” but must also take into consideration “the dynamism of political life “at home” in West Africa itself,” as pointed out by Gregory Mann (Reference Mann2015: 157). The political participation of the migrants was propelled still further by events unfolding in Africa, especially in their home countries, whether the urban youth protests in Senegal against the regime of Léopold Sédar Senghor in the late 1960s, or the overthrow of socialist Malian president Modibo Keïta by Lieutenant Moussa Traoré in 1968.

This convergence was vividly demonstrated when a foyer supervised by Senegalese authorities burned down on 1 January 1970, in Aubervilliers, an industrialized suburb in northern Paris. This tragedy, in which five West African migrants died, provoked a general outcry from migrant associations as well as from left and radical left organizations (Gastaut Reference Gastaut2000: 52–60). On the day of the funerals, radical activists occupied the headquarters of the Conseil National du Patronat Français (CNPF) with the support of prominent intellectuals engaged in Third World causes, including Marguerite Duras, Jean Genet, and Jean-Paul Sartre. During the occupation, the emerging links between national and international issues were highlighted in slogans such as “Imperialism kills in Aubervilliers like in Chad,” a reference to one of the numerous French military interventions in its former colonies Gordon Reference Gordon2012: 101).

THE EMERGENCE AND IDENTITY OF RÉVOLUTION AFRIQUE

The organization Révolution Afrique was created by two French activists who had been members of the Ligue Communiste before the split that gave birth to Révolution! in February 1971: Gilles de Staal (b. 1948) and Madeleine Beauséjour (1945 or 1946–1994).

Staal had earned his Baccalauréat in 1968 and had undertaken training in journalism. His partner Beauséjour, a black woman from the French island of Réunion, had studied cinema at the University of Nanterre and was working as a film editor. In the spring of 1969, she had traveled to Senegal with another filmmaking student and Révolution! member, Richard Copans, for a project to document peasant life.Footnote 14 Back in France in the summer of 1969, Beauséjour filmed and interviewed Boubacar Bathily, one of the leaders of a foyer strike in Saint-Denis. This encounter was the starting point of her entry, together with Staal, into the foyers (Staal Reference Staal2008: 25–26). From that moment, both endeavored to support and develop immigration-related struggles and to recruit African “comrades” as part of their activities within the Ligue Communiste. They set up tenant committees (comités de locataires) in the foyers, and in 1971 initiated a short-lived journal with Staal as its deputy director.Footnote 15 Apart from Staal and Beauséjour, a handful of French activists from Révolution! worked closely with the group.

Foyers were at the time becoming scenes of fierce competition to recruit migrant activists, both between parties and organizations of the established left and between Trotskyist and Maoist movements (Dedieu and Mbodj-Pouye Reference Dedieu and Mbodj-Pouye2016). Révolution!’s activists made their first foothold on the ground in the foyers in the suburbs north of Saint-Denis, notably in Pierrefitte and Drancy, where they recruited many African activists.

In July 1970, West African residents of the foyer located at rue Lénine in Pierrefitte initiated a rent strike to protest housing conditions.Footnote 16 Throughout 1971, they persevered with the strike in the face of police repression in July and subsequent judiciary action. The group's involvement in the protest allowed them to enroll one of their first African activists, Mamadou Konté, born in rural Mali in 1948, who was a worker at that point.Footnote 17 Konté was pivotal in forging the link between the Révolution! activists and residents of the foyers, and later became the group's leading figure.

In December 1971, a second rent strike in the neighboring area of Drancy further catalyzed both mobilization and recruitment.Footnote 18 This strike is acknowledged, both in activist narratives and in period administrative accounts, as the starting point of the first “organized movement” or “wave” of strikes in the foyers, a fact which illustrates the influence of the group due to its ability to connect protests scattered across different locations.Footnote 19 Another migrant, Amadou D., joined Révolution! during this protest. He was born in Senegal, where he had been schooled up to the secondary level, unlike Konté who had not been to school.Footnote 20 Amadou D. had long been exposed to politics. As an adolescent at the time of his country's independence, he recalls initially hoping that Léopold Sédar Senghor and Mamadou Dia would succeed in their transformative project of Senegalese society, before he became disillusioned after Dia's imprisonment in 1962. As part of his early political training he mentions reading Marxist literature and, though not heavily involved himself, taking part in the May 1968 “mouvance” in Senegal. He migrated to France to join a French friend who was a member of the PSU. He worked in a chemical plant and moved to the Drancy foyer in early 1972, where he was immediately attracted by the theoretical discussions among French and African activists.

Recruitment later extended from Drancy and Pierrefitte to several other foyers located in central Paris. New members were notably recruited in the foyer located on rue de Charonne from among a group of Senegalese and Malians, both workers and students (Staal Reference Staal2008: 57), and in another foyer on rue Saint-Denis, from which several Malian workers joined. One of them, Samba Sylla, born in 1948 in rural Mali, had migrated to France in 1965. Before moving to the rue Saint-Denis foyer he had lodged in a private building along with other West African workers in the eighteenth arrondissement in Paris, and he signed up for literacy classes provided by African students in the neighborhood. In May 1968 he found himself working in a factory that produced elevators, where he was active in the strike.Footnote 21

In the beginning, membership in Révolution Afrique necessitated integration within Révolution!, and the first African activists such as Konté therefore joined the parent organization. After a few months, though, the recruitment process became more informal and new participants did not need to become members of Révolution! Sylla remembers that when he joined the movement it was considered an autonomous African section. Later on, recruitment also took place in Dakar, where Staal traveled in June 1973 (ibid.: 100–12). He stayed in a house owned by Amadou D.’s family and next to the Blondin Diop family in the middle-class area of SICAP. Arriving shortly after Omar Blondin Diop's death, he connected with his brothers. He also met politicized high school and university students living in the same neighborhood, including Mamadou Mbodji (b. 1948), who had just obtained his Baccalauréat.Footnote 22 Mbodji migrated to France a few months later and became an active member of the group, together with his Franco-Senegalese partner Aïda Ndiaye (b. 1953).

As the group consolidated over its first few years and extended to Marseille, Révolution Afrique's original team recruited a sizable number of African activists. Among the hundred mentioned by Staal (Reference Staal2008: 143), we have been able to identify thirty members and establish their socio-demographic characteristics, including their nationalities, occupations, and genders. In terms of national origins, they were from francophone West African countries. More than ten were from Mali and almost as many from Senegal, two or three were from the Ivory Coast, one was from Mauritania, and one from Niger. So far as occupations, most Révolution Afrique members were workers who typically lived in foyers. There were also a handful of students from Senegal and two Ivoirian students. Regarding gender, Beauséjour and Ndiaye were the prominent female figures in the Paris cell of Révolution Afrique. The Marseille cell had at least three female members, including a black woman from the French Caribbean islands.Footnote 23

The growing number of African activists within Révolution Afrique provided the group with “indigenous” resources to which other radical organizations had no access. As memories from non-members attest, the presence of leftists was an issue within the foyers. In Drancy, often presented as Révolution Afrique's stronghold, revolutionary slogans were met with suspicion by some of the residents who were either aligned with the Communist municipality or resented the politicization of the protests. This disapproval even led to the temporary physical ban of Révolution Afrique from the foyer.Footnote 24 However, the presence of African activists with linguistic skills eased a breaking of initial resistance by those who spoke no French. Furthermore, these activists also drew from a political repertoire developed in Africa prior to their migration, which allowed them to reach out to a larger number of African migrants than other radical organizations.Footnote 25

Extending the long literary and activist history forged by Caribbean and African migrants and intellectuals in Paris since the imperial era (e.g., Mudimbe Reference Mudimbe1992; Edwards Reference Edwards2003; Wilder Reference Wilder2005), Révolution Afrique published its inaugural issue in 1972. This was the group's first public appearance; they had not complied with the French legal requirement for associations to register with the police and were as a result simply being described as a “groupement de fait.”Footnote 26 The journal would go on to constitute the backbone of the organization and to reflect its multifaceted political activism. Over the years it maintained a consistent visual identity, despite irregularities due to its homemade character, with variations in length, presentation, and format. Some columns appeared in one issue, only to disappear in the next. The number of pages, generally sixteen, was occasionally reduced to eight, while its size varied from less than A4 in 1973 to a full A3 in 1977. Each issue, however, had a cover page adorned by a clenched fist reminiscent of a drawing of the African continent, and displayed photographs, drawings, and caricatures that echoed the cultural activities pursued by the group. These included film reviews, documentary screenings, and the production of movies. In some cases the journal offered its readers posters, a common art form and powerful vehicle popularized starting in the 1960s for civic engagement and communication, such as one of Amílcar Cabral (see figure 1).Footnote 27 This sensibility to visual forms illustrates how Révolution Afrique’s editors were attuned to the radical aesthetics embraced by leftist organizations in the aftermath of May ’68 (Seidman Reference Seidman2006: 129–49).

Figure 1. Poster of Amílcar Cabral published in Révolution Afrique, 1973. Courtesy of Bernard Dréano. Picture: Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC).

Just as the activists in pictures were made unrecognizable by black blindfolds, most of the journal's articles were unsigned. The first person plural—the collective “we”—often appeared in opinion pieces and articles throughout the journal, while the use of imperative forms in titles, almost acting as slogans, was widespread, for example, “Let's demand” (“Exigeons”) or “Free” (“Libérez”). In a handful of issues, mostly later ones, more or less cryptic signatures were used. This is the case, for instance, in a “reader's corner” section signed by “A.D.,” who presents himself as “a worker, former high-school student in Dakar,”Footnote 28 or in an open letter to President Lamizana signed by “Yero, Voltaic worker.”Footnote 29 These suggest the contribution of a larger number of people, but two figures emerged as central to the writing process: Staal, obviously equipped with the relevant skills as a journalist, and Konté, whose inspiration and eloquence are said to have shaped much of the discursive output, though he himself could read but not write.

THE AMBIGUITIES AND CHALLENGES OF TRANSNATIONAL POLITICAL ACTIVISM

The revolutionary struggles in both France and Africa were the two main themes developed by Révolution Afrique’s editors and contributors,Footnote 30 and a willingness to embrace a transnational political agenda was notable from its inception. In November 1972, it publicized its activities as follows: “Révolution Afrique is an organization, in France, of revolutionary African immigrants.… The day we return home, we will participate in the revolutionary fight against the exploitative regimes of Senghor, Moussa Traoré, etc.… Participating in struggles in France and preparing revolution in Africa are two related tasks.”Footnote 31

Ideologically, the joint struggles in both destination and origin countries were in line with dependency or world-system neo-Marxist theories, a component of leftist and Third-Worldist literature at the time, which explained international migrations through the disruptive impact of capitalist expansion in peripheral societies that had taken place since the imperial period (Massey et al. Reference Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouaouci, Pellegrino and Taylor1993: 444–48). Révolution Afrique's militants were attuned to these ideas and more largely committed to the Marxism-Leninism advocated in the courses they organized. In 1974, Révolution Afrique ran a long article entitled “Our tasks in the struggles.”Footnote 32 The editors referenced crushed revolutionary upheavals such as the Paris Commune in France and the confiscation of independence from urban classes in Africa, and underlined the stark differences between African and French “proletariats.” They highlighted how African peasants hired by trading companies to grow cotton or peanuts became, without the long historical process of industrial revolution, migrant workers employed in French factories. “We African workers have a whole different story,” they wrote. “We brutally and without transition became industrial proletarians when we had to leave the bush and the village to come and sell ourselves in France.”Footnote 33 For Révolution Afrique's militants, both African peasants and migrants were facing common destitution and subjection originating in the same causes. “The African worker is exploited here as we all know,” they recalled, “because our countries are under the neo-colonial yoke, because peasantry is over-exploited in Africa, because economic development is blocked by imperialism.”Footnote 34 This analysis led them to promote the idea of organizing themselves by means of a revolutionary vanguard both in Africa and in France.Footnote 35

Révolution Afrique’s aspiration to forge and unify revolutionary movements on both sides of the Mediterranean translated into an editorial angle that consistently combined reports of situations in France and on the African continent, as shown in Table 1. By combining these two struggles, Révolution Afrique positioned itself within the fragmented, post-1968 field of French radical leftist organizations. It was by embracing such a transnational approach that Révolution Afrique succeeded in defining its stance toward other organizations operating in the same terrain. This was particularly true of the Ligue Communiste, whose African cell made up primarily of students created the journal Afrique en Lutte in 1973 (Salles Reference Salles2005: 166). The Ligue Communiste operated an editorial strategy that lay counter to the transnational stance of Révolution Afrique: immigrants’ experiences and struggles were covered in the organization's main journal Rouge, while the situation on the African continent was almost exclusively dealt with by Afrique en Lutte.Footnote 36

Table 1. Countries most frequently referred to in Révolution Afrique’s articles. Among sixty-six named countries, the table indicates those that appear more than ten times.

Révolution Afrique also expressly tried to assert its differences from the main existing African associations. FEANF, which still enjoyed the legacy of its contributions to anti-colonial struggles, was harshly denounced as being led by African students with “petty bourgeoisie” orientations. The Union Générale des Travailleurs Sénégalais en France (UGTSF), created in the late 1950s under the aegis of Léopold Sédar Senghor and supported by French charities, human rights associations, and trade unions, was accused of collusion with the Senegalese embassy. This even though the UGTSF was trying to gain autonomy from the Senegalese government during the same period, while attempting to reach out to leftist organizations such as the Centre Socialiste d’Études et de Documentation sur le Tiers-Monde (CEDETIM) (Dedieu Reference Dedieu2012).

The transnational political and structural position adopted by Révolution Afrique was not without ambiguity. The dynamics of power relations within the group itself were complex in terms of race, citizenship, and class. Staal, as a French white man, was accused by other African groups of “being manipulative and colonialist” (Staal Reference Staal2008: 82). However, the racial boundaries within the leadership and the group were blurred by the presence of black French citizens such as the Réunionese Beauséjour and Franco-Senegalese Ndiaye, as well as couples made up of African migrants and their French white partners. Still, the issue of nationality was crucial. To borrow the concept forged by Doug McAdam (Reference McAdam1986), African citizens bore the brunt of this “high-risk activism.” French activists were relatively protected by their nationality, while African activists were more exposed, given the risk of expulsion from the country at a time of intense police repression and the deportation of foreign activists and trade unionists.Footnote 37 Sylla recalls, for example, that on one of his trips back to Mali the Malian police interrogated him about his political activities in France and confronted him with clippings from Révolution Afrique. Further, French activists were often from intellectual backgrounds while migrant activists were mostly workers, with a minority of students.Footnote 38 Still, the visibility of African migrants and their active roles and inclusion in the leadership helped legitimize the group both internally and externally with regard to other associations.

The independence of Révolution Afrique from its parent organization Révolution! was another critical issue, which partly overlapped with the racial issue. The growing autonomy of Révolution Afrique was frowned upon by Révolution! leaders, who subsequently designated a white French activist as the leader of Révolution Afrique in 1973 as part of a strategy to tighten their control over the group, a move that African activists resented (Staal Reference Staal2008: 112–13). This crisis led to the inclusion of African activists as representatives of Révolution Afrique within Révolution! Discussions about the possibility of full autonomy from Révolution! continued, and in 1975 the journal dissociated itself from Révolution!’s press.Footnote 39 The final step was the creation in 1976 of a new structure, the Organisation des Communistes Africains (OCA), but the group was banned within a year of its founding.

Beyond these internal difficulties, Révolution Afrique faced a wider structural challenge in asserting that struggles in France and in Africa were part of a larger and common struggle. The actual position of migrant activists within this transnational movement remained ambiguous, and was interpreted following one of two contradictory lines: they were either being trained to provide a vanguard for revolution in Africa, or were part of the sphere of immigrant struggles in France. Tied to a prospect of return, the first interpretation shaped the activists’ time spent in France as formative to further action back home; the second viewed them as participants in wider anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist struggles in a country where their political action endeavored to carve out a better place for themselves.

INSTIGATING AND DOCUMENTING MIGRANTS’ STRUGGLES IN FRANCE

Révolution Afrique devoted articles to migration-related struggles in France that reflected the group's political objectives: to integrate West African workers into the fight taking place on the factory floor, coordinate action in the foyers, and oppose the immigration agreements signed between France and its former African colonies.

The housing conditions of migrants featured prominently in each issue. The dominance of this topic not only reflected the heavy politicization of the housing issue at the turn of the 1970s, but also Révolution Afrique's strategy of enrolling migrants in foyers. The group's links to the foyers gave them access to privileged information. African and French activists alike recall that each of the group's members was assigned particular foyers to cover.Footnote 40 This targeting of the foyers as sites from which to access African activists and engage them in a political cause was the strategy of most groups concerned with immigrants’ rights. However, Révolution Afrique's combination of local recruitment among the residents and political activity by outsiders, whether French activists or students coming from outside the foyers, was unique and explains its journal's detailed coverage of rent protests throughout the 1970s.

The second area of politicization was the workplace. Accordingly, the other recurring topic in Révolution Afrique was the participation of West African migrants in strike actions in the factories, where most of them had menial jobs that exposed them to continuous racial discrimination and infringement of their working rights at a time of rising unemployment (Pitti Reference Pitti2009). This focus was in line with the stance of Révolution!, which advocated revolutionary action in sites of production, leading Révolution Afrique to set up a branch at car manufacturer Renault. Strikes in the car industry,Footnote 41 the shipyards,Footnote 42 and the cleaning servicesFootnote 43 were the most covered subjects due to their economic importance, highlighting the CGT's ambiguous position toward the migrant working population, despite the worker internationalism publicly advocated by its leaders (Dedieu Reference Dedieu2012).

The period of the journal's existence coincided with a tightening of migration laws. The early 1970s were marked by heightened questioning within the French government, especially in the Ministry of the Interior, of the postcolonial migrants’ rights negotiated during the decolonization process. The adoption in 1972 of the Marcellin-Fontanet circularFootnote 44 was a major turning point in what was a general attempt to control migratory flows and it prompted the first mobilizations of undocumented migrants (Siméant Reference Siméant1998), whose hunger strikes were reported in Révolution Afrique.Footnote 45

Révolution Afrique’s articles devoted to the social and political situation in France demonstrate the organization's ambition to unify action on crucial issues such as housing, employment, and residency rights (see figure 2). These rallying calls reflected the political debates of the time around self-determination (autogestion) endorsed by the PSU and the Confédération Française Démocratique du Travail (CFDT). Such debates were far from being purely rhetorical. The most marked aspect of this drive to unify efforts was that it sought to transcend ethnic and regional boundaries. Révolution Afrique's ambition was to forge an “authentic immigration front” that would bring together sub-Saharan African and North African migrant populations.Footnote 46 An editorial published in 1975 stated, “We respect the right and necessity for each nationality and major regional grouping to unite and organize themselves.… However, we are in favor of, and struggle for, the coming together of the different immigrant nationalities to act jointly, marching side by side, for our exploiter is the same; our interests are the same. The defeats and the blows that Arabs suffer are defeats and blows for Africans, the victories and successes won by Arabs are also victories and successes for Africans. Since we stand together in the factories, on the building sites, and under the racists’ blows, we are convinced that we must live and win together.”Footnote 47

Figure 2. Cover of Révolution Afrique, 1977. Courtesy of Bernard Dréano. Picture: Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC).

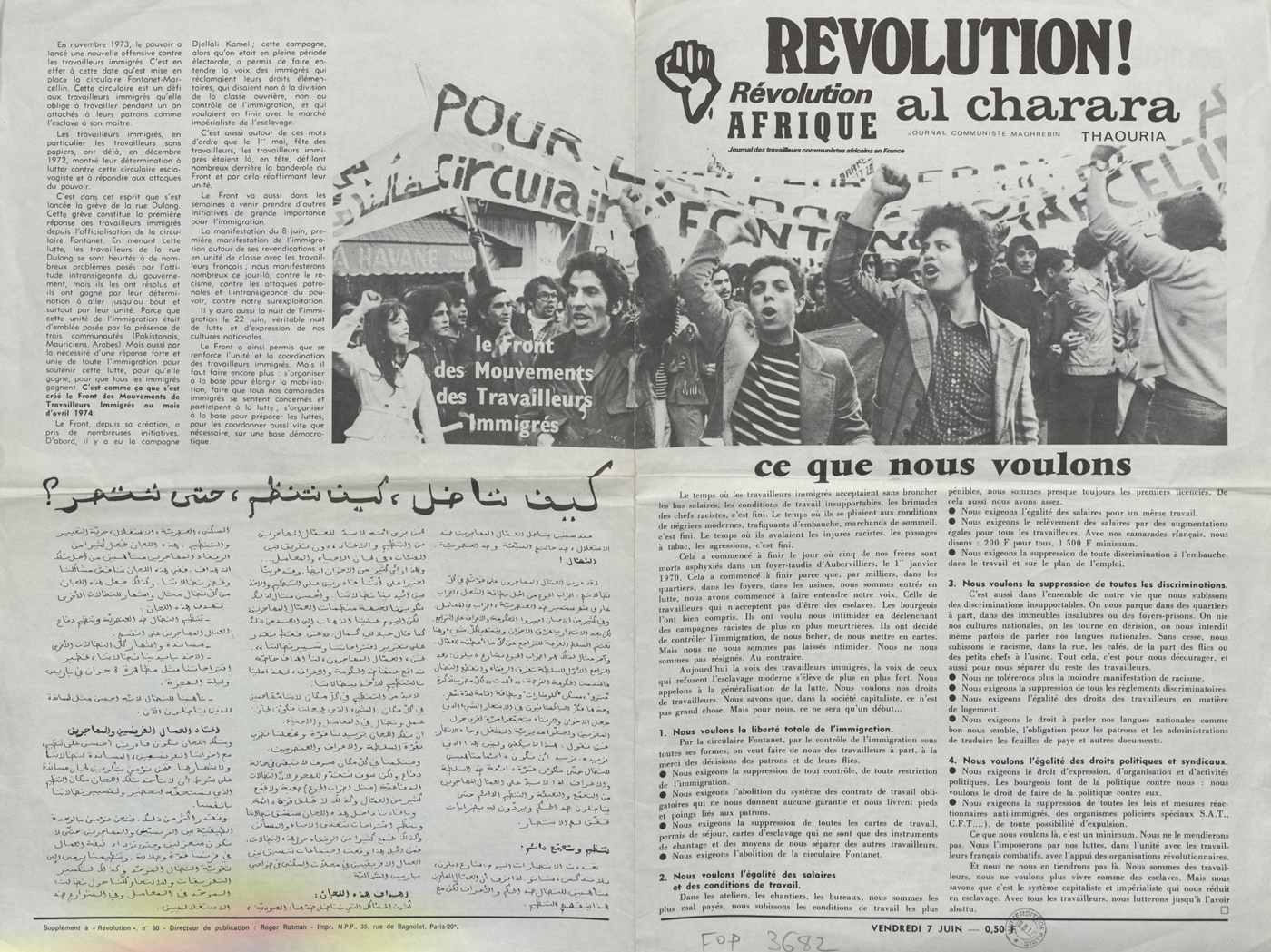

Révolution Afrique held several meetings with North African associations, such as the Comité des Étudiants-Travailleurs (Tunisiens) de Vincennes, the Comité des Travailleurs Algériens (CTA), and the Mouvement des Travailleurs Arabes (MTA).Footnote 48 The development of ties with North African organizations highlights the fact that the tightening of migration laws placed both populations of postcolonial migrants in a similar situation. Furthermore, the legacy of anti-colonial struggles led by North Africans before independence was a source of inspiration. Two of Révolution!’s activists involved in the creation of Révolution Afrique refer to the Algerian nationalist organization Étoile Nord-Africaine, created in 1926 in Paris by Messali Hadj, as the model they wished to emulate due to its transnational existence, first in France, then in Algeria.Footnote 49 This willingness is apparent in the joint publication in 1974 of a special issue by Révolution Afrique and Révolution!’s journal Al Charara Thaouria: Journal Communiste Maghrébin, aimed at North African migrants. The issue gathered together articles, in both French and Arabic, which advocated a joint front line of postcolonial workers that could address their common social destitution together (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Joint Issue of Révolution Afrique and Al Charara Thaouria, 1974. Credit: Courtesy of Bernard Dréano. Picture: Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC).

The ambition to create a lasting unification of North African and sub-Saharan organizations met difficulty in traversing a number of social, historical, and racial boundaries. These materialized in xenophobic sentiments expressed between sub-Saharan Africans and North Africans, rooted in their experience in Africa, the memories of West African soldiers enrolled in the French army during the Algerian war, and inter-ethnic tensions in France due to their competition for menial jobs and scarce housing (Dedieu and Mbodj-Pouye Reference Dedieu and Mbodj-Pouye2016: 961–62). A generational and political asymmetry was also pronounced. The North African activists mainly belonged to the second (or even third) generation settled in France. In contrast, Révolution Afrique's sub-Saharan activists had been there for several years at most. Ultimately, Révolution!’s attempts to create the North African equivalent to Révolution Afrique failed, and Al Charara Thaouria was much shorter-lived and less remembered. Révolution Afrique occupied a space that was vacant, while existing groupings such as the MTA were organizing North African migrants and the second or third generations.Footnote 50

COVERING AND RALLYING FOR AFRICAN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS

To unify African movements was another of Révolution Afrique’s calls for action (see figure 4). Each issue contained detailed articles on Africa that ranged from editorials and interviews with African dissidents to movie reviews and the reproduction of leaflets distributed in African cities. Two main themes emerged, which were also publicized at Révolution Afrique's meetings and rallies: denunciation of West African regimes, and solidarity with the struggles for independence in Portuguese colonies and anti-apartheid movements in South Africa.

Figure 4. Cover of Révolution Afrique, 1973. Credit: Courtesy of Bernard Dréano. Picture: Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC).

West Africa was a focus because Révolution Afrique's African activists originated from this region, as did the overwhelming majority of sub-Saharan migrants in France. The spiraling deterioration of the social and political situation in that region from the late 1960s onward, alongside repeated French military interventions (Luckham Reference Luckham1982), highlighted that the collective hopes born out of the decolonization process had simply been crushed.

West Africa was, however, unevenly covered in the journal, as shown in Table 1. Senegal was documented much more than any other country in the region, though it was heading toward a limited multi-partyism as early as the mid-1970s (Diop and Diouf Reference Diop and Diouf1990). Several factors explain this discrepancy. Even though most Révolution Afrique articles were unsigned, it was less risky to cover Senegal than to write about dictatorships. News of Senegal regularly circulated between Dakar and France within the migrant community and Révolution Afrique's networks, which included many Senegalese. Senegal enjoyed a prominent political position in the postcolonial bloc due to the strong ties between Senegalese and French political figures dating back to the imperial age. The death in detention in May 1973 of Omar Blondin Diop, after his expulsion from France and his arrest in Mali, prompted a general outcry in both France and Senegal. In the Summer 1973 issue, a tribute paid to this “internationalist militant” praised him: “He was not among those who say: ‘I'll only fight when I am in my country,’” thereby offering his iconic trajectory as a model for revolutionary struggles across borders.Footnote 51 The democratization process initiated by Léopold Sédar Senghor was repeatedly vilified in the journal, while support was expressed for the clandestine Marxist-Leninist party And-Jëf, with ample coverage of the trial of its leaders in 1975.Footnote 52

Independence and anti-racist movements on the African continent were the second most prevalent topic. Liberation movements in Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique (Chabal Reference Chabal2002) were at first heavily covered. Articles were mainly devoted to revolutionary movements such as the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), the latter founded by the revolutionary theorist Amílcar Cabral. Révolution Afrique presented Cabral, who was murdered on 20 January 1973 in Guinea's capital of Conakry, as an exemplary figure to be emulated. The journal's treatment of his death highlights the transnational dynamics of mobilization as well as the circulation from the African continent to France of the framing of events and news. Indeed, the journal not only reported meetings organized in both France and Senegal to pay tribute to Cabral's memory and advocate the pursuit of revolutionary action, but it also held up Senegalese reactions to the events as a lesson to follow. “Like the pupils and students of Dakar, who turned their homage rally to Cabral into a violent struggle against Senghor's regime,” reads one article, “we think that, all things considered, the best form of support is to incorporate a revolutionary anti-imperialist element into our struggles.”Footnote 53 In late 1974, meetings were organized in Paris and Marseille in order to support “people from Guinea, Angola, and Mozambique.”Footnote 54

After the Portuguese colonies attained independence,Footnote 55 coverage of Southern Africa gained momentum. As the journal stated on its front page after Angola had won its independence: “Victory for Angola. Tomorrow Southern Africa.”Footnote 56 The coverage of anti-apartheid struggles reflected the rise of transnational protests against the South African regime (Thörn Reference Thörn2006). The 1975 tour to France of the Springboks, South Africa's national rugby team, was harshly denounced.Footnote 57 The journal displayed the connections Révolution Afrique had established with members of the African National Congress (ANC) when it published an interview with Winnie Mandela the following year in which she asked for the support of the French people: “[T]he people of France have proved their attachment to the cause of freedom during the country's history, leading up to the revolt of the students and young workers in May 1968 that serves as an example for many young Africans. Naked, we fight today for our freedom; the French people cannot be anywhere but at our sides.”Footnote 58 In such instances, the struggle in Africa was tied to possibilities of mobilization in France, for example when the journal provided templates of letters to be addressed to consulates.

While the situation of immigrants in France was often reported first-hand and tied to specific sites and ongoing actions and mobilizations, the reports on the situation in Africa were more fragmented. The analysis of political and social events involved more generic than specific calls for support, due to not only the multiplicity of national contexts but also the practical difficulties in covering them and getting reliable information.

THE FIRST END OF RÉVOLUTION AFRIQUE: THE BANNING OF THE OCA

The tightening of restrictive laws on migration had a lasting and dramatic impact on migrant political organizations. Culminating with the suspension of labor migration in 1974, they created the start of the “decolonization of immigration” (Noiriel Reference Noiriel2007: 675). From the beginning of the 1970s, an administrative struggle over the management of postcolonial migration was waged between the French Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the latter of which had managed issues of post-independence migration (Spire Reference Spire2005). The Ministry of the Interior considered the political engagement of migrants to be a breach of public order. In 1971 one of its representatives noted: “Highly politicized associations, generally Marxist-Leninist, are composed in their majority of students opposed to the governmental authorities in their origin countries. They operate in close connection with French extremist groups and frequently take part in events affecting public order.”Footnote 59 Through a circular issued on 22 July 1976, the Ministry of the Interior put an end to the freedom of association that had been granted to citizens from former French colonies in the aftermath of decolonization.

Thereafter, migrants were forced to comply with the Decree-Law of 1939 that required foreign associations in France to obtain formal authorization from the Minister of the Interior. This measure was intended to affect “associations which will be now formed” as much as “African associations already established.”Footnote 60 A result was that more than a dozen organizations were dissolved between October 1976 and November 1980, including the iconic FEANF (Dedieu Reference Dedieu2011). The Organisation des Communistes Africains, newly emerged from Révolution Afrique, was one of the first to be banned, in December 1976.Footnote 61

The daily newspaper Libération, cofounded by Jean-Paul Sartre in the early 1970s, protested with a front-page headline on 6 January 1977 (see figure 5), and a second the next day that read: “After the banning of the OCA, the freedom of association is taken away from foreigners.” On 7 January, a meeting was organized by leading human rights associations and professional unions representing lawyers and magistrates in order to challenge the ban.Footnote 62 Immigration had become an important internal issue within the process, led by François Mitterrand, of the unification of left-wing political parties known as the Union of the Left (Union de la Gauche). On 4 February, another meeting was convened by Révolution Afrique and the Association des Amis des Communistes Africains to mobilize against the banning of the OCA and, more broadly, call for the abolition of the Decree-Law of 1939. Later, Révolution Afrique published a special issue entirely devoted to the government's decision to dissolve the OCA, entitled: “The Organisation des Communistes Africains has been banned. The leaders of the now banned OCA speak to the African workers.” It called for the “unconditional freedom of association, expression, and movement.”Footnote 63 Notwithstanding the mobilization of the French left, the ban against the OCA was upheld. Révolution Afrique became clandestine and ceased its activities at the end of 1977; its journal's last two issues are dated as January and April of that year.

Figure 5. Cover of Libération, 1977. Courtesy of Libération. Picture: Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC).

THE SECOND END OF RÉVOLUTION AFRIQUE: DEBATING RETURN

Révolution Afrique did not end only due to legal and political constraints; also involved were internal debates concerning the possibilities and politics of return for African activists. Though return had featured as the logical horizon of action for Révolution Afrique since its inception in 1972, the issue took on a distinct meaning in the mid-1970s. Against a background of rising unemployment and a global economic crisis, the “reintegration” of migrants in their home countries had become a central part of immigration policies and public debates (Dedieu Reference Dedieu2012). Policymakers pushed for the repatriation of third-country nationals and the negotiation of bilateral agreements between sending and receiving countries. In 1977, these policy debates led to the implementation of a grant system (aide au retour) aimed at encouraging immigrants to leave France. The question of return had also gained momentum within migrant associations during the mid-1970s in the wake of the Sahel drought of 1973 and the growing poverty of the communities that had been left behind. In 1976, these dynamics led to one collective project in which migrants returned to Mali and, supported by humanitarian associations, negotiated with the Malian regime (Soumaré Reference Soumaré2001). At the same time, French governmental bodies, in particular the Ministry of Cooperation, advocated development programs in West Africa in order not only to curb migratory flows from the continent but also to promote returnees as developers of their home countries. These programs were increasingly endorsed by charitable associations, grassroots organizations, and trade-unions. This shift stressed the collapse of revolutionary Third-Worldist utopias (Liauzu Reference Liauzu1987; Szczepanski-Huillery Reference Szczepanski-Huillery2005) that had been born out of the anti-colonial struggles. It also announced the transformation of radical activism into professional humanitarianism (Davey Reference Davey2015) against the background of the “anti-totalitarian moment” spread by left-wing political thinkers in France and the emergence of the “human rights movement” onto the world stage (Moyn Reference Moyn2010: 120–75).

By the mid-1970s, the political project and the practical conditions of return for Révolution Afrique's African activists had become an ever more complex subject within the group. Révolution Afrique denounced the reintegration policies promoted by the French government, while at the same time pleading for a revolutionary-inspired return to Africa (Staal Reference Staal2008: 173–83). Most of the African members in the group resented this command to return, which was problematic in terms of their own life choices. In 1977, the same young men and women who had initiated or actively supported the movement in the early 1970s, most of whom were born around 1948, found themselves at a distinct stage of their life cycle. They had to make crucial decisions as to whether to return to Africa or instead remain in France for the pursuit of studies or work, and this brought to the surface their differences in terms of class, education, and nationality. Within the analytical frame commonly applied to return migration, politically motivated return would fit into the category of “return of innovation,” intended as transformative (Cerase Reference Cerase1974; Cassarino Reference Cassarino2004), and would be opposed to “return of conservatism” aimed at reinforcing social structures in the sending countries. The actual paths taken by Révolution Afrique's activists who positioned themselves in favor of this project of return testify to a more complex picture.

Collective return amounted to a short-lived experiment in the Senegalese city of Thiès, where Konté and Ndiaye decided to open a cultural center and bookshop. The endeavor lasted from 1978 to 1981, with several members of the group present for shorter durations. More significantly for the future of the group, Konté decided to fund this experiment by organizing a concert called “Africa Fête” in 1978, the first of a series that survived him. This move toward involvement in cultural activities, whether the Thiès project or holding concerts to raise funds, was in line with Révolution Afrique's long-standing interest in counterculture. It nevertheless reoriented the group's networks towards artists, journalists, and intellectuals driven by Konté’s charisma, and elicited fierce criticism from his comrades who felt that he had betrayed his base by personalizing the group's activities and succumbed to the lure of celebrity.Footnote 64

People's sense that they were at a crucial point in their personal trajectory could heighten tensions and disrupt group dynamics. Mbodji, for example, failed to abide by the order to return. Though he embraced the prospect of return at a personal level, he resented the way that French leftists tended to discourage African students from pursuing their studies:

At that time, revolutionary movements most often involved children of the French bourgeoisie such as students or holders of university degrees, and many of them had left their jobs…. Nonetheless they still had their diplomas and their level of education. So one thing that made me distance myself from Révolution! was, without it being openly stated, that we were encouraged, made to think that studies were something bourgeois, that we had to be part of the workers’ movement.… I said: “Fair enough, I want to go back to Africa, but I can't see myself being there … more so as a nurse or a worker, or in any kind of factory—it's not possible, it won't allow me to earn a decent living.” That's one of the things that made me distance myself from the organization.

Mbodji thus frames the collective decision on the subject of return as being oblivious of the social and material imbalances between African and French activists. In 1977, he chose instead to focus on finishing his studies in France, and only after he had obtained his diploma in psychology did he eventually returned to Dakar.

Outright opposition to the idea of return was expressed by Samba Sylla, who explained that the project did not agree with his political convictions and aspirations as a migrant. “There were differences of opinion on the subject of leaving for Africa. Because it was all about sending people to prepare for revolution over there. We did not support that. There was the Maison des Jeunes in Thiès, and a library in Dakar I think, well, sure we favored such initiatives. But not for us to return. We had not come for.… We would not be the ones who would start the revolution in Africa. We could contribute and even support, but not lead. On this point, there were disagreements.”

Committed to political action for migrants’ rights, Sylla was active in demonstrations, film screenings, and the distribution of the journal and leaflets. Through connections with members of the Maoist Union des Communistes de France marxiste-léniniste (UCFml), he pursued his anti-racist activism by joining the group Permanences Anti-Expulsion, created in 1977 to support the rent strikes in the Sonacotra foyers and to contest migration policies. Divorced from Révolution Afrique's transnational agenda and its focus on “Black Africa,” anti-racist activism in France was an option for those who remained politically involved. They could take part in movements that soon adapted to accommodate the demands of the second generation, mainly North African youth.Footnote 65 Sylla later became active in the Groupe de Recherche et de Développement Rural dans le Tiers Monde (GRDR), a non-governmental organization that promoted development projects for migrants in West Africa and was regularly supported by the French government.

Returns were therefore either short-lived, as in the cases of Konté and Ndiaye, or people refused or postponed, like Sylla and Mbodji did. In addition to the national framework for action of the French immigrants’ rights movement that was publicly emerging, two paths of reconversion arose, at the transnational level, as the main avenues for applying migrants’ political skills and networks: culture and development.

One example of choosing the first alternative is Konté, who turned to a form of cultural activism that retained discursive references to the political line of Révolution Afrique. At the same time, though, it was in keeping with the French State's program of promoting immigrant cultures in order to advance their cultural “integration,” but also to counter autonomous forms of expression (Laurens Reference Laurens2009). The second avenue, development, was instigated as a public policy in order to tackle the migratory flows from former colonies, and it expanded more intensely after the electoral victory of François Mitterrand in 1981, materializing in a strong transnational network of hometown associations. It also led to the movement abandoning its hardline revolutionary stance.

Despite the diversity of their trajectories, both from personal and militant perspectives, many former members insist that their experience in Révolution Afrique was a key formative aspect of where they ended up. While reflecting on activities they pursued while in their early twenties evoked a sense of nostalgia, participants often cited as unique the co-presence of both French and African activists, and students and workers. The ultimate divergence of their paths echoes generational choices, and also reflects that many objectives of the period's transnational political activities were unattainable within the social and political contexts of either region.

CONCLUSION

Though Révolution Afrique took part in a “transnational imagination” of radical politics (Prestholdt Reference Prestholdt2012), it operated at a time when the institutional and intellectual environments in the post-imperial French space drastically changed. In the post-independence era, political alternatives dwindled due to the spread of the single-party apparatus across the African continent and repression of dissent in France and in African countries. With the suspension of migratory flows in 1974 and the proscription of African radical groups, the late 1970s saw the definitive closure of the political opportunities that had been created by and available to several generations of African activists in France. The demise of the project borne by Révolution Afrique shows how “migrants do not create their communities on their own,” but are ultimately always dependent for their transnational political activism on the national policies of the states that sent and received them (Waldinger and Fitzgerald Reference Waldinger and Fitzgerald2004: 1178).

Historians working on France and West Africa have pinpointed the mid-1970s as the decisive period when migrants from the former African colonies came to be treated as any other migrant group. Here we have brought in the migrants’ own perspectives, their reflections on this historical juncture, to bear on understanding this period, and in the process we have assessed their agency. While Gregory Mann suggests that the activism of migrants during this period may have reinforced the processes that defined them as “foreigners” (Reference Mann2015: 158), scrutinizing Révolution Afrique has led us to a different conclusion. Through active participation in a racially and socially mixed group, African activists immersed themselves in French leftist and Third-Worldist countercultures and movements, and became acquainted with other immigrants’ organizations as potential mainstream allies. In doing so, they expanded their political repertoire and social networks. In the end, beyond the intricacies of their personal trajectories, their time within Révolution Afrique provided them with formative training in the creation of new organizations, and offered them grounds on which to claim that they belonged to France as much as to Africa. This is one reason so many resented the command to return to Africa.

Beyond Révolution Afrique's intransigent demands on the French State and its impassioned critique of African regimes, its journey seems most unique in the way that it delineated the Franco-African space as a viable sphere of political action and life. The initial indeterminate nature of the trajectories of its African members reflected a wider set of circumstances in which the social and migratory destiny of African migrants in France was still uncertain. After the advent of neoliberal doctrines and reforms on both sides of the Mediterranean, other forms of transnational action emerged. These had the support of French and African governments as well as non-governmental organizations, such as the institutional capacity of migrants to act as agents of development between “here” and “there,” to borrow a recurring trope used by humanitarian professionals, policy-makers, and scholars alike. This shift, though, was defined within a narrow and apolitical developmentalist frame that concealed the stark differences between, on one hand, an immigrant working class struggling with economic crisis in France and incited to channel their financial remittances into African rural projects, and, on the other, a small elite with an extensive social capital inherited from their years in France, benefitting from opportunities of mobility and recognition. It was on this disparity that the hopes of transcending national and social boundaries that once characterized Révolution Afrique were dashed.