Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 March 2005

The Tanzimat—a series of legal and administrative reforms implemented in the Ottoman empire between 1839 and 1876—has been described by Roderic Davison as a modernization campaign whose momentum came “from the top down and from the outside in.” There can be little doubt about the basic historical veracity of this characterization. Ottoman reform was indeed the brainchild of a small, albeit influential, portion of the imperial bureaucratic elite and its direction and timing were undeniably influenced by foreign diplomatic pressure (in the context of the so-called “Eastern Question”). But by characterizing, correctly, the Tanzimat as a state-led, elitist project, Davison's argument enters an interpretive vicious circle which seems to be more a reflection of twentieth-century political sensibilities than of nineteenth-century realities. A “top-down” political project, according to this argument, is by definition less likely to succeed than a project that has “vigorous popular support.” And, since we know that the project in question ultimately failed to stop the breakup of the empire, it must indeed have lacked such support.

I thank Margarita Dobreva, Evgenii Radushev, Maria Kalitsin, Rositsa Gradeva, and the staff of the Ottoman section of the Prime Ministry archives of Turkey, for their help in facilitating my research in Sofia and İstanbul respectively. Professors M. Şükrü Hanioğlu, Stephen Kotkin, and Michael Cook, all of Princeton University, read drafts of this paper and provided helpful comments. My archival work was supported in part by a fellowship from the International Dissertation Field Research Fellowship Program of the Social Science Research Council, with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Transliteration, place names, and dates: Ottoman terms are transliterated according to their modern Turkish spelling, as given in Redhouse Türkçe-İngilizce Sözlük (İstanbul: SEV, 1997). The exception is the term sharia which is given in its popular English form—derived from Arabic with diacritics omitted—instead of the Turkish equivalent şeriat (although the corresponding adjective is transliterated in its Redhouse Turkish spelling: şerءî). Bulgarian terms are transliterated according to the Library of Congress system. Place names are given in their present form (Ruse instead of Rusçuk, Veliko Tûrnovo instead of Tırnova, etc.). All dates are Gregorian.

The Tanzimat—a series of legal and administrative reforms implemented in the Ottoman empire between 1839 and 18761

The periodization I use here (from the 1839 Gülhane Reform edict to the 1876 Ottoman Constitution) is the most widely accepted one; some authors use a narrower one (1856 to 1876).

Roderic Davison, Reform in the Ottoman Empire: 1856–1876 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963), 406.

Ibid.

It may be objected that the breakup of the Ottoman state itself was also a “top-down, outside-in” event in that most of the empire's post-Tanzimat territorial losses were the direct result of military defeats (in 1878, 1912, and 1918) that were, at best, indirectly related to popular support (or lack thereof) for the reform program. Indeed, as we become “less enamoured of the methods by which nation states were created, made homogenous and praised for their virility in the crude, brutal and Darwinian intellectual climate of the early twentieth century,”4

Dominic Lieven, Empire: The Russian Empire and Its Rivals (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 191.

Benjamin Fortna, Imperial Classroom: Islam, the State, and Education in the Late Ottoman Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 3.

The present study adds to this revisionist line by asking whether the Tanzimat reforms made a tangible impact on the cognitive and epistemological worlds of the non-elite Ottoman subjects. This is not a trivial question. A large body of scholarly literature maintains that no such impact existed, especially in regard to the non-Muslim minorities.6

Davison (Reform, 407–8) claims that the reforms' “most signal failure” was in their inability to popularize the supra-national ideology of Osmanlılık. Karpat suggests that the Tanzimat had a profound and positive impact on the political culture of Ottoman Muslim groups (e.g., by making it possible for Turks to eventually embrace Kemalism), but no impact on Christian ones. Kemal Karpat, “The Ottoman Rule in Europe from the Perspective of 1994,” in his Studies on Ottoman Social and Economic History: Selected Articles and Essays (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 504.

Takvim-i Vekayiע [8 Oct. 1864]. The organic statute of the province was published as Loi constitutive du département formé sous le nom de Vilayet du Danube (Constantinople: Imprimerie Centrale, 1865).

The main ethnic and religious groups in the province were the Orthodox Christian Bulgarians and the Sunni Muslim Turks. Smaller groups included Sunni Tatars and Circassians (immigrants from lands recently conquered by the Russian empire in the Crimea and the Caucasus respectively), Gypsies/Roma (who were split into Muslim and Christian sub-groups), Sephardic Jews, Orthodox Romanians and Greeks, and Gregorian Armenians. There was also a plethora of even smaller insular communities such as Pomaks (Bulgarian-speaking Muslims), Gagauzes (Turkish-speaking Christians), Bulgarian Roman Catholics, Shiite Muslims, Russian Old Believers, Ukrainian Cossacks, Ashkenazi Jews, Protestant Armenians, etc. The precise proportions of the different ethnic groups in the Danube vilayet are a subject of considerable controversy. An Ottoman census undertaken in the late 1860 (results published in 1874) indicated that Bulgarians made up just over 50 percent of the population; Turks—34 percent; Tatars and Circassians (combined)—5 percent, Gypsies—3 percent, smaller groups—8 percent. Figures from consular and other European sources tend to vary according to the political sympathies of the source and are altogether less reliable than the census. See Georgi Pletnءov, Politikata na Midkhat pasha v Dunavskiia vilaet (Veliko Tûrnovo: Vital 1994), 54–61.

This seems to be the consensus of the otherwise antagonistic Bulgarian and Turkish national historiographies. See Istoriia na Bûlgariia (Sofia: Izdatelstvo na BAN, 1987), vol. 6, 32–38; Khristo Khristov, Bûlgarskite obshtini prez Vûzrazhdaneto (Sofia: Izdatelstvo na BAN, 1973), 130; Hüdai Şentürk, Osmanlı Devletiءnde Bulgar Meselesi, 1850–1875 (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 1992), 87.

Ahmed Midhat Paşa is one of the best-known figures of the Tanzimat reforms, celebrated in Turkish historiography as architect of the Ottoman constitution (1876), founder of the system of agricultural credit cooperatives, and a successful provincial governor. For biographical details, see Ali Haydar Midhat, The Life of Midhat Pasha: A Record of His Services, Political Reforms, Banishment, and Judicial Murder (London: John Murray, 1903) and İbnülemin M. K. İnal, Osmanlı devrinde son sadrıazamlar (İstanbul: Maarif Matbaası, 1940–), 315–414. For various aspects of Midhat's policies as provincial governor, see Pletnءov, Politikata; Tevfik Güran, “Osmanlı İmparatorluğuءnda Ziraî Kredi Politikasının Gelişmesi, 1840–1910,” in Uluslararası Midhat Paşa Semineri (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 1986), 95–127; Maria Todorova, “Obshtopoleznite kasi na Midkhat Pasha,” Istoricheski Pregled 28 (1972):56–76; Nejat Göyünç, “Midhat Paşaءnın Niş valiliği hakkında notlar ve belgeler,” Tarih Enstitüsü Dergisi 12 (1981–1982):279–316; David Dean Comminis, Islamic Reform: Politics and Social Change in Late Ottoman Syria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990); Yaşar Yücel, “Midhat Paşaءhnın Bağdat Vilayetindeki Alt Yapı Yatırımları,” in Uluslararası Midhat Paşa Semineri, 175–85.

The reformist policies included the creation of a hierarchy of administrative and judicial council with mixed (Muslim and non-Muslim) membership; the building of some 3,000 km of roads, 150 km of railway, 1,420 bridges, and 34 telegraph stations; the chartering of several publicly traded shareholders' companies providing services ranging from coach and steamship travel to mail delivery; the rectification of city street layouts, planting of public parks and gardens, re-hauling existing arrangements for waste and sewage disposal and other urban reforms; and the establishment of seven hospitals and a provincial quarantine board. Also notable were Midhat's efforts to harness the labor and financial resources of ever broader segments of the population—the roads, for example, were built through a mandatory labor service, the expansion of the bureaucracy was often “self-financed,” and previously marginalized social groups such as orphans, vagrants, and prisoners were effectively conscripted in the service of reform through “imaginative” new policies. See Pletnءov, Politikata, 80–81 and 89–151; Hans-Jürgen Kornrumpf, “Islahhaneler,” in Économie et sociétés dans l'Empire ottoman (fin du XVIIIe—début du XXe siècle), ed. Jean-Louis Bacqué-Grammont and Paul Dumont (Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1983), 149–56; Dunav / Tuna [newspaper] (Ruse: Pechatnitsa na Dunavskiia vilaet, 1865–1876) (henceforth Dunav) III/232 [15 Nov. 1867]; Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivleri: İrade-i Meclis-i Vâlâ (İstanbul) (henceforth BOA İ.MVL.), 25972; Natsionalna Biblioteka Kiril i Metodii: Bûlgarski Istoricheski Arkhiv (Sofia), II A 1042.

As created in 1864, the province also extended over regions that subsequently became parts of Serbia, Romania, and Macedonia.

Moreover, even if the meta-narrative of “rise of nations” is temporarily set aside, we are still left with the question of whether the Ottoman state of the 1860s was at all capable, either technologically or institutionally, of engaging in any sort of transmission of ideas to its subjects. Although in 1865 the vilayet of Danube became the first Ottoman province to set up a government-owned printing press and to start publishing an “official” newspaper (the billingual Tuna/Dunav), the miniscule size of the reading public undoubtedly limited the impact of this propaganda outlet. Most state-to-subject communication would have occured, as in earlier periods, through the public reading of government edicts by policemen (zaptie) and town-criers (tellâl), or through the word-of-mouth of informal social networks which typically relied on the mediation of local notables. The two great avenues of state-led enculturation (or disciplining, depending on the perspective)—the conscript army and the school—were simply not available as such to Ottoman reformers of this period. The military and educational experiences of the empire's subjects varied so greatly depending upon their religious and ethnic affiliation (not to mention gender), that the overall institutional setup of the Tanzimat army and school system(s) probably undercut rather than reinforced the stated ideological goal of the reforms.13

Throughout the Tanzimat period, repeated promises to allow non-Muslims to serve in the army were never realized, while education remained dominated by confessional schools which were not subject of government regulation. See Davison, Reform, 94–95, Fortna, Imperial Classroom, 10. This makes for an interesting contrast with Mehmed Ali's Egypt, where both mass conscription and an experiment (however brief) with government education were introduced in the 1820s and the 1840s, respectively. For critical reassessments of Egyptian “modernization” in these fields, see Khaled Falmy, All the Pasha's Men: Mehmed Ali, His army and the Making of Modern Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997); and Timothy Mitchell, Colonising Egypt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), especially 69–74.

There is, finally, the question of timing. Undoubtedly, most individuals, regardless of their social status can be expected, over time, to modify their behavior according to the expectations of the prevailing political power, especially in situations in which the individuals come into direct contact with the agents or institutions of power. But insofar as the Tanzimat involved a certain degree of change in the state's expectations of ideal/proper subjecthood, the readiness with which “ordinary” men and women learned to “speak Tanzimat”14

I am greatly indebted here to Stephen Kotkin's discussion of “speaking Bolshevik” as a form of mandatory discursive self-identification “game” in Stalinist Russia—see his Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as Civilization (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), ch. 5. Of course, this is not meant to suggest that there was any ideological or institutional similarity between Stalinism and Ottomansim.

Apart from some commercial courts and courts specially designed to hear cases involving non-Ottoman subjects, the vilayet of Danube was the first instance in which a distinct hierarchy of judicial bodies separate from the Islamic (şerءî) courts was instituted in the Ottoman empire. See C. V. Findley and H. İnalcık, “Mahkama (2.ii),” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition (Leiden: Brill, 1980–), vol. 6, 5–9; Gülnihal Bozkurt, “The Reception of Western European Law in Turkey: From the Tanzimat to the Turkish Republic 1839–1939,” Der Islam 75 (1998):289; Şerif Mardin, “Some Explanatory Notes of the Origins of the ‘Mecelle’ (Medjelle),” The Muslim World 51 (1961):196, fn. 19; Sedat Bingöl, “Tanzimat sonrası taşra ve merkezde yargı reformu,” in, Osmanlı, ed. Güler Eren (Ankara: Yeni Türkiye Yayınları, 1999), vol. 6, 533–45.

The records of the nizamî courts remain one of the most inexplicably underutilized Ottoman sources.16

Khaled Fahmy's pioneering work has demonstrated the great potential of “reformed” or “secular” courts' records as sources for the social history of nineteenth-century Egypt. To date, there has been no comparable study of the structurally similar Ottoman nizamî court records. See Khaled Fahmy, “Law, Medicine, and Society in Nineteenth-Century Egypt,” Égypte/Monde arabe 34 (1998):17–51; idem., “The Police and the People in Nineteenth-Century Egypt,” Die Welt des Islams 39 (1999):1–38.

For a discussion of the methodological problems of using sicils as a historical source, see Dror Zeءevi, “The Use of Ottoman Sharīעa Court Records as a Source for Middle Eastern Social History: A Reappraisal,” Islamic Law and Society 5 (1998):35–56.

I have in mind here the outstanding studies of Natalie Zemon Davis, Carlo Ginzburg, and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie and others.

Haim Gerber, “Muslims and Zimmis in Ottoman Economy and Society: Encounters, Culture and Knowledge,” in Studien zur Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im Osmanischen Reich, ed. R. Motika, C. Herzog, and M. Ursinus (Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag, 1999), 99.

Besides Zeءevi's article quoted above, see Haim Gerber, State, Society, and Law in Islam: Ottoman Law in Comparative Perspective (Albany: SUNY Press, 1994), 15, 43; Suraiya Faroqhi, Coping with the State: Political Conflict and Crime in the Ottoman Empire: 1550–1720 (İstanbul: The İsis Press, 1995), xviii–xix; and Madeline Zilfi, ed., Women in the Ottoman Empire: Middle Eastern Women in the Early Modern Era (Leiden: Brill, 1997), 5.

By contrast, the nizamî court records of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century provide in abundance the kind of raw “social history” data whose absence in the sicils is so often regretted. The interrogation protocols (istintakname) attached to many nizamî court cases are especially valuable in this regard. Unlike virtually any other type of Ottoman legal source, the interrogation protocols are verbatim accounts of what was said during the investigative process. As such, these documents contain the first-person narratives of bona fide non-elite social actors, which have proven so elusive in other types of Ottoman sources, including sicil records. The interrogations, therefore, provide a precious glimpse into the “intellectual, moral, and fantastic worlds”21

Carlo Ginzburg, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things that I Know about It,” Critical Inquiry 20 (1993):23.

That is not to say that the nizamî court records pose no interpretative problems as historical sources; they do. One has to keep in mind the caveat that legal sources in general tend to describe real or inferred breaches of “normal” social behavior. There are pitfalls in trying to reconstruct a social reality from documents, which often “distort the picture in favor of the extraordinary”22

Amy Singer, Palestinian Peasants and Ottoman Officials: Rural Administration Around Sixteenth-Century Jerusalem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 120. The quote reflects Singer's methodological concerns about the mühimme registers upon which her work on sixteenth-century Palestine is based, but it strikes me as applicable to the nineteenth-century nizamî court records as well.

Natalie Zemon Davis, Fiction in the Archives: Pardon Tales and Their Tellers in Sixteenth-Century France (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987), 5–6.

The most accessible cases are those from the irade collections (particularly BOA İ.MVL.), which contain only those lawsuits that had required Sultanic approval (irade). That means that the irade collections are limited to cases involving either (a) capital punishment, or (b) reduction of a OPC-prescribed penalty at the discretion of the sovereign.

In other words, I avoid looking at these cases as being “representative” of, for instance, the types of crimes committed, or of the gender, age, or ethnic breakdown of criminality in the Danube province.

The criminal law applied in the Danube province during the 1860s was a blend of Islamic (sharia) and state-issued (kanun) regulations, practices, and institutions.26

A full discussion of the complexities of Ottoman criminal law is beyond the scope of this paper. My remarks here are intended simply to introduce the basic terms and concepts which are essential to understanding the legal cases discussed below. For detailed analyses of the Ottoman legal system in the classical period, see Uriel Heyd, Studies in Old Ottoman Criminal Law, ed. V. L. Ménage (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), 167–311; for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, see Gerber, State, Society and Law, 58–78; for the nineteenth century, see Rudolph Peters, “Sharia and the State: Criminal Law in Nineteenth Century Egypt,” in State and Islam, ed. C. van Dijk and A. H. de Groot (Leiden: Research School CNWS, 1995), 152–77.

(a) An Islamic court can be described as the institutional extension of the person of the judge (kadı)—a religious scholar formally trained in the principles of jurisprudence (fıkh). In theory, a kadı was not required to base his decisions on any specific legal text, but rather on his comprehensive knowledge of fıkh; in practice, most Ottoman kadıs followed closely one of several sharia manuals that effectively codified the legal views of the Hanafi branch of Islamic law.27

Gerber, State, Society, and Law, 30.

(b) By contrast, nizami courts could be described as bureaucratic judicial councils—they were staffed by a mixture of appointed government officials and “elected” local notables.28

The franchise system for electing members to the nizamî courts was very restrictive and ensured that the political authorities had ultimate control over the outcome of the “elections.” See İlber Ortaylı, Tanzimat Devrinde Osmanlı Mahallî İdareleri, 1840–1880 (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 2000), 70–92.

The Danube province consisted originally of forty-five districts (kaza) grouped into seven sub-provinces (sancak). Nizamî criminal courts (daavi or cinayet meclisleri) were established in each kaza and sancak center, as well as in the provincial capital of Ruse. Appellate courts (temyiz-i hukuk meclisleri) were set up at the sancak and vilayet levels.

The cases preserved in the BOA İ.MVL. and Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivleri: Sadaret Evrakı Mektubî Kalemi: Meclis-i Vâlâ (İstanbul) (henceforth BOA A.MKT.MVL.) in particular allow us to trace the unfolding of each lawsuit through the justice system.

Described in this way, the coexistence of two disparate sets of judicial norms and institutions may appear self-contradictory and unworkable. In practice, however, the elements of sharia and kanun meshed to form a stable legal environment. Article 1 of the 1858 Penal Code laid the groundwork for the compromise:

It concerns the State to punish offenses against private persons, by reason of the disturbance such offences cause to public peace, equally with those directly committed against the State itself.

And by reason thereof, the present Code determines the different degrees of punishment, the execution of which has by the [sharia] been committed to the supreme authority. Provided always that the following provisions shall in no case derogate from the rights of private persons given to them by the [sharia].31

The Ottoman Penal Code 28 Zilhiceh 1274, trans. C.G. Walpole (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1888) (henceforth OPC), Article 1.

In order to understand the importance of that passage, let us take as an example the prosecution of murder trials. The sharia, as was mentioned above, regards homicide as a violation of private rights. Consequently, it gives the victim's relatives (who are deemed to be the “injured party”) the prerogative to initiate prosecution, select the type of punishment, or absolve the offender of punishment altogether. Strictly speaking, the sharia allows the state to punish a murderer independently from the victim's relatives only when the killing has taken place in a context of certain other offenses (for example, highway robbery) that fall under the rubric of violation of the “rights of God.” That meant that the payment of “blood-money,” for example, was considered a sufficient penalty for murder under şerءHî rules. It is not difficult to see that a “modernizing” state dedicated to expanding its own authority, promoting public order,32

The preservation of public order (or, “tranquility and silence,” to use the officially favored euphemism), was referred to in several articles in the provincial newspaper (e.g., Dunav I/28, [20 Sept. 1865]) as the most important raison d'être of Midhat's administration.

Rudolph Peters used this term to refer to the criminal justice system of nineteenth-century Egypt. At least until the establishment of the so-called Mixed Courts in Egypt (1876), the fundamentals of the Egyptian and Ottoman legal systems were similar enough to justify my borrowing of the term. (Egypt, of course, remained an autonomous Ottoman province until World War 1). Rudolph Peters, “Murder on the Nile: Homicide Trials in 19th Century Egyptian Sharīעa Courts,” Die Welt des Islams 30 (1990):115.

OPC, Article 172.

Besides resolving the fundamental conflict between private and public claims, the system of dual trial also effectively bypassed certain practical problems inherent in criminal prosecution accordining to Islamic law. Proving intent, for example, is difficult under şerءHî rules, since it is contingent mainly upon the type of weapon used in committing the crime (for example, no murder by strangulation could be judged to have been intentional, since the human hand is not a lethal weapon in itself).35

Peters, “Murder on the Nile,” 103.

Peters, “Sharia and the State,” 167.

Peters, “Murder on the Nile,” 112–13.

For example, slander (other than the slanderous allegation of fornication which is a hadd crime), bribery, etcetera.

For example, embezzlement which could not be fitted into the şerءî definition of theft, since the latter required that the goods stolen be kept locked and hidden. Peters, “Sharia and the State,” 153.

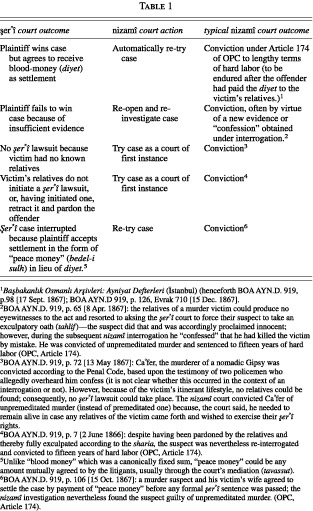

A brief look at the lawsuit summaries inscribed in the so-called Ayniyat registers for the Danube province suggests that the application of the system of dual trial did indeed enable Midhat's provincial administration to prosecute criminals more “vigorously” and to achieve a high rate of incarceration. Table 1 lists the main scenarios in which the state was able to modify “unsatisfactory” şerءHî outcomes in murder cases through a recourse to the nizamî courts.

The nizamî courts also proved instrumental in enabling the Ottoman political authorities to avoid certain cumbersome şerءHî procedures and rules. One example is the canonical mass exculpatory oath (kasame)—while still prescribed by Muslim jurists in homicide cases against unknown suspects, the evidence suggests that in practice the kasame was rendered obsolete by nizamî investigative practices.40

BOA AYN.D. 919, p. 127 [15 Dec. 1867]: as part of a homicide case against unknown perpetrators, the plaintiff sought the opinion of the office of the Chief Müfti (Şeyhülislam) in İstanbul as to how the şerءHî lawsuit could proceed. The Müfti's office replied by recommending the enactment of a kasame, whereby the plaintiff would select fifty (male) villagers and ask the court to require each one of them to swear to his own innocence of the crime. However canonically correct, the Şeyhülislam's recommendation remained a dead letter—instead of executing the kasame procedure the authorities conducted nizamî investigation, at which it “became known” that a certain villager had fatally shot the victim during a quarrel.

The plaintiff[s] must prove what each of the accomplices did, whether each accomplice acted willfully, and whether each of the accomplices' acts, if committed separately, would have resulted in death; it is the combination of these variables, plus the timing of the death relative to the attack, that decides how the criminal liability should be apportioned. See Peters, “Murder on the Nile,”106–7.

OPC, Article 175: anyone who “has assisted a murderer in the committing of a murder” was to be punished by from three to fifteen years of hard labor.

BOA AYN.D. 919, p. 44 [8 Nov. 1866]: two suspects (father and son) confessed that the son had held the victim's hands, while the father slit the victim's throat. That confession was used in a şerءHî case against the father, while the son was sentenced as an accomplice according to OPC Article 175 without any reference to the sharia.

It has been observed that legal reform played a uniquely ambivalent role in the Tanzimat modernization project. Partly because they were unwilling to antagonize the powerful religious establishment, the Tanzimat reformers typically tempered their support for new legislation with an essentially conservative historical analysis steeped in nostalgia for the lost glory days of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when the “rules of the sharia were always perfectly observed.”44

The quote is from the 1839 Gülhane Edict, translation in J. C. Hurewitz, ed., The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics: A Documentary Record, 2d ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975), vol. 1, 269–71.

Hıfzı Veldet, “Kanunlaştırma Hareketleri ve Tanzimat,” in Tanzimat I: Yüzüncü yıldönümü münasebetile (İstanbul: Maarif Matbaası, 1940), 165–209; see also Bozkurt, “The Reception of Western European Law in Turkey.”

It would be misleading, therefore, to describe the process of creating the Tanzimat legal codes as one of wholesale “borrowing” from European (usually French) models. Some of the legislative landmarks of the Tanzimat, such as the Land Law (1858) and the Civil Code (1870–1877), have been rightfully celebrated as original syntheses of Islamic and “Western” legal norms and principles. But even in criminal law, the “borrowing” model is only of limited use. Most of the 1858 Ottoman Penal Code may indeed have been copied from a 1810 French Penal Code, yet, as we saw above, the incorporation of the all-important Article 1 made the resulting criminal justice system a unique and—considering that, with some amendments, the OPC remained in force until the end of the empire and beyond—highly durable arrangement. Moreover, the privileged position of the sharia and the persistence of Islamic courts meant that legal reform was not accompanied by any significant process of cadre change within the judicial establishment. Reformist bureaucrats did not supplant medrese-trained ulema as the chief administrators of law in the empire. In fact, there was a significant degree of cadre continuity from the şerءHî to the nizamî courts: in the Danube province, for example, members of the ulema—from the local kadı to the province's chief âlim (the müfettiş-i hükkâm who held office in the provincial capital Ruse)—presided over all nizamî courts by virtue of the regulations of the provincial statute. Furthermore, the ulema managed to preserve their presence in all walks of the reformed Ottoman judicial system, even after its final major reorganization in 1879.46

David Kushner, “The Place of the Ulema in the Ottoman Empire during the Age of Reform (1839–1918),” Turcica 19 (1987):61–62.

Given the coexistence of şerءHî and nizamî legal institutions and processes it seems all but impossible to pinpoint “objective” elements of modernity in the Ottoman judicial system during the Tanzimat period. Max Weber's famous analysis of Islamic law (“kadi justice”) as the epitome of a pre-modern (“patrimonial”) social system and as the opposite of the substantive, rational, and predictable modern Western law47

On Weber's theory of legal systems, see Max Rheinstein, ed., Max Weber on Law in Economy and Society (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1969).

Gerber, State, Society, and Law, 26–27, 42–57. Gerber's study is based upon seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sicil material from the courts of Bursa.

In the end, the link between Ottoman legal reform and “modernity” can be seen most clearly and unambiguously at the level of contemporary discourse. The political powers-that-be in the Danube province consistently presented the new legal system as a qualitative break with the past. Specifically, the nizamî institutions and practices were promoted as a corrective to the sharia's perceived softness on certain crimes (such as murder) and clumsy evidence protocols.49

The “barbaric” hadd penalties prescribed by the sharia for certain crimes aroused the indignation of European observers but appear not to have worried Ottoman reformers—and, in any event, their application had been practically discontinued (with the exception of flogging). Peters, “Sharia and the State,” 170–71.

Some criminals delude themselves by thinking that they would not be caught and that punishment could only be meted out if [according to the sharia] they themselves confess, or if two witnesses testify to their guilt. So, they decide that they would deny everything in court, and, if they have accomplices, all make a pact about what they would say, thinking that, as they committed their crime in secret, it would be impossible to prove. Others, not knowing the degrees of punishment prescribed by law for their crimes, think that it [the punishment] would be something light. There are also those, who reflect on what has happened in previous times and make the mistake of thinking that they could find protection or intercession before the law from the notables or from some government officials.

All such plans come to nothing during the interrogations (istintak) which take place in the new courts. The rules of the interrogation and the courts are not as simple as some people think. In these courts, there take place long and detailed examinations and investigations of every crime—big or small—so that the truth is invariably revealed. Moreover, thanks to the corps of inspectors (müfettiş) dispatched to every place, day and night, secretly or in uniform, all events everywhere are easily made known.50

Dunav I/28, [20 Sept. 1865].

Here, the juxtaposition with “what has happened in previous times” creates the sense of historical rupture that is at the heart of every modernist discourse. The article's anonymous author uses phrases—“big or small,” “day and night,” “all events everywhere,” “invariably”—that emphasize the omnipresence and omniscience of the new legal system. Because a nizamî court never fails to reveal the “truth” (by virtue of its superior investigative tools) and to mete out the harsh sentences prescribed by the Penal Code, its main role shifts from the punishment to the prevention/deterrence of crime.

The self-righteous tone of the newspaper article was often echoed in the nizamî courtroom itself. In the following interrogation protocol for example, a certain Ahmed Hamzaoğlu, who is accused of murder, had attempted to reverse a previously made confession, claiming that he had been forced to falsely incriminate himself. The interrogators were not impressed:

Q: No one ever confesses simply as a result of [being subjected to] force and intimidation. And nowadays especially, governments don't trick criminals like you, or greater or smaller ones for that matter, into confessing by the use of force. If you persist in your denial, we shall officially send you to the police (polis). There you'll suffer in vain. Don't do this to yourself. Repeat here the confession you made in Razgrad [the town where Ahmed was first interrogated] and we will find you an easy way of making peace with the deceased's relatives!

A: I won't confess; put me in the police!

Q: Do you know what police means? Even if you regret this [decision] afterwards and even if you deny your guilt for eighty years, it's of no use—you are already condemned . . .

A: I know [what the police is]—it's the prison (habis). When I confessed my head was completely confused.

Q: No, the police is not the prison. But it is [such] an extremely narrow and cold place, in which one can be squeezed, that you would be finished there. Besides, no headache or drunkenness can be so great as to make one [wrongly] confess to such a great crime.51

BOA İ.MVL. 25897 [interrogation: 2 Jan. 1867].

It would be obvious that all the key elements of the language of the Tanzimat reforms are present in the interrogators' words above. There is a sense of a troubled past (when “force and intimidation” may indeed have been the government's tools in extracting false confessions) but also a clear sense that that past has been decisively transcended. The key phrase marking the transition from the pre-modern to the modern is “nowadays” (şu zamanda). It is inconceivable, as a matter of principle, that the state nowadays would have tortured a suspect, because torture is incompatible with the Tanzimat concept of law as a guarantee not only of public of order, but also of justice and individual rights. The beauty of this discursive device, of course, is that it is unaffected by the actual continuity of the practice of torture;52

Torture has been called “the most typical kanun innovation” (Gerber, State, Society, and Law, 68) and appears to have been routinely used in criminal cases in pre-Tanzimat times. OPC, Article 103, outlawed the use of torture but, judging by the numerous instances in which suspects attempted to reverse their previous confessions by claiming that they been “cheated” into providing them, the practice seems to have continued in the nizamî courts as well. Occasionally, we find specific allegations of torture: for example, a rape suspect alleging that his previous confession had been extracted by the police's application of pepper vapors (biber tütsüsü), tweezers, and tongs (BOA A.MKT.MVL. Dosya 312, Vesika 45 [3 Mar. 1867]); or a murder suspect claiming that the investigators had forced him to stand on his feet for two days without allowing him to sit or lie down (BOA İ.MVL. 25824 [17 Nov. 1866]).

Of course, it would be naïve to expect that the Ottoman state's interlocutors across the interrogation line accepted wholeheartedly the idealized official vision of the new justice system. Ahmed, the suspect in the murder case quoted above, seems to have viewed it all as a monolithic disciplinary force whose finer distinctions were irrelevant to him (hence the striking equation of “police” and “prison”). But, regardless of their “real” attitudes towards the reforms, the ordinary men and women of the Danube province proved quite skillful in playing the new judicial game, negotiating with state power, and using the peculiarities of the “dual trial” legal system to their advantage in court. This was a noteworthy achievement.

On the night of 20 October 1866, a certain Lambi from the town of Svishtov on the south bank of the Danube was mortally wounded in front of his own house.53

All documents relating to this case: BOA A.MKT.MVL. Dosya 349, Vesika 38 [8 Dec. 1867].

At first glance, the legal case seemed clear-cut. The victim himself (he had remained conscious after the attack), his mother, and his sister had all claimed that the murderer was the local policeman, Salih b. Abubekir. Yet when the relatives brought forward a şerءHî lawsuit against Salih, (14 May 1867), the case was dismissed due to the lack of independent eyewitnesses to the crime. The policeman's legal victory, however, was only temporary. He faced a determined opposition, particularly in the face of Simeona, Lambi's mother. Undeterred by the dismissal of the şerءHî case, Simeona wrote a petition to the provincial governor (7 November 1867) requesting that the case be re-tried in a nizamî court. Her request was granted and the first round of interrogations began on 10 November 1867 in Ruse.

The first fact of the case that became reasonably well-established was that, on the night of the murder, Salih had spent a substantial amount of time at a tavern (meyhane) near Simeona's house, getting increasingly drunk.54

As attested to by the tavern owner, his son, and a fellow Muslim customer by the name of Hüseyin who said he was embarrassed by Salih's inebriation in front of the Christians present at the meyhane (Hıristiyanlardan utandım).

For his part, Salih denied the accusations and underlined the fact that, as he had been acquitted of the crime at the şerءHî hearing, he would only accept a “guilty” verdict if any eyewitnesses to the crime were to come along, i.e., if the şerءHî standard of proof was met:

A: What can I say, sir—let those people [the eyewitnesses] come here; then I would be resigned to God's orders and the Sultan's law.55

AllahءHın emrine ve PadişahءHın kanununa razıyım.

It is ironic that Salih, who, in his duties as a police officer, would have had some involvement in the administration of the new nizamî justice, had failed to grasp its underlying principles. He seems to have regarded his interrogation as an extended and unnecessary repeat of the şerءHî hearings. Despite the interrogators' repeated offers to help him reconcile with Lambi's relatives,56

The interrogators offered Salih to reconcile him with the relatives and pleaded with him not to cause further complications to the case (bir takım teklifâta hacet bırakma!) and to admit that the murder had been a drunken accident (sarhoşluk haliyle bir kaza).

The policeman's poor choice of strategy was in stark contrast to the behavior of his main opponent. Simeona pursued all her legal options vigorously and shrewdly. In her letter to the governor she explained that she believed that Salih had been wrongfully acquitted and that she wanted him tried according to the “Imperial Penal Code.” In court, she repeated that all she wanted was for Salih to be punished in accordance with the law. Simeona correctly assessed the fact that the standard of proof in a nizamî court was different from the one in its şerءHî counterpart, and that, consequently, discursive choices which had no place before a kadı could prove decisive during an interrogation. Her testimony was based on dramatism—dramatic description, dramatic story-telling and dramatic action. Describing Lambi's wounds, she related her own horror at the sight of her son's intestines spilling out of his abdomen. Intriguingly, Simeona portrayed Salih not only as a cruel and calculating murderer, but also as a person recklessly indifferent to the certainty of his own upcoming punishment:

A: [after the first stab] my son and we began screaming and, when some neighborhood girls approached, Salih rushed to the yard door [trying to escape]. But then, telling himself: “I'd be put in chains one way or another; let me at least kill him completely,” he turned around, stabbed my son again in the stomach and pulled out his intestines. [Lambi] died eight or ten hours after that. Oh, my son!

The crux of Simeona's accusations was her claim that “emboldened by grief” she had rushed out of the house to her son's aid and had hit Salih with a piece of wood leaving an injury mark on his head. During the şerءHî hearings, such an injury mark would not have been considered as evidence; during the nizamî case, however, Simeona was taking no chances—as her cross-examination with Salih drew to a close, she reached out and knocked off his fes hat, pointing out, (in the words of an astonished court scribe), that the wound mark was indeed where she had predicted it would be.57

Heman merkum SalihءHin başını açub irae eylemiş ve filhakika eser-i cerh görülmüş.

The court hardly needed more persuasion. It found the defendant's repeated denials “futile” (vahi) and recommended a sentence of fifteen years of hard labor.58

OPC, Article 174 (unpremeditated murder).

Q: You are right to say that such a murder case requires [eyewitness] proof according to the sharia; however, according to the new rules it can be decided by clues and circumstantial evidence!59

. . . böyle katl maddesi şeraen isbata muhtac isede, nizamen emare ve serrişte ile tutulur!

We have no way of knowing through what mechanisms Simeona obtained her superior legal knowledge. Svishtov was a prosperous commercial center and the education level of its inhabitants was probably higher than the average for the Danube province. Yet, we have no reason to believe Simeona was literate or that her socioeconomic status was anything but average.60

Simeona “signed” the interrogation protocol by her fingerprint, which was usual for illiterate litigants. As for her socioeconomic status, the only indication we have is that her husband had been paralyzed for years and could not work—in a patriarchal society that would have been a heavy economic blow.

To be sure, unlike Simeona, most of the “subjects” we see in the nizamî criminal cases were caught up on the receiving end of the new Ottoman justice system. The stories told in the context of legal self-defense are significant not only for their literary merits (however considerable) but also because they reflect aspects of the contemporary social consensus on certain key dichotomies such as normalcy/deviance, culpability/innocence, or credibility/incredibility. In Davis' words, each such story incorporates “choices of language, detail, and order needed to present an account that seems true, real, meaningful and/or explanatory.”61

Davis, Fiction in the Archives, 3.

Let us begin with the most common discursive strategy. Almost invariably, the interrogated persons chose an overall tone and comportment which emphasized their complete submission to the judicial process and their willingness to accept its decisions, whatever they may be. Policeman Salih's arrogance with the interrogators is not matched in any other case I have read and even he, it would be recalled, pledged his resignation to the “will of God and the Sultan's law” if the case were proven to his satisfaction. Outright challenges to legal procedures or the courts' impartiality were rarely voiced and, when they were, proved ineffective.62

See the Kapucuk case, quoted below, in which one of the suspects claimed that the court had shown excessive leniency towards the village notables, while being too harsh on “us poor people.”

BOA A.MKT.MVL. Dosya 275, Vesika 93 [11 Dec. 1865]; BOA A.MKT.MVL. Dosya 312, Vesika 47 [4 Mar. 1867].

Such claims of ignorance and submission merit a degree of skepticism. For one thing, they were often part of a larger defensive strategy through which the accused sought to portray themselves as gullible rather than malevolent and their actions as misguided rather than outright criminal. On 17 April 1866, for example, a certain Halil b. Fatah was interrogated in Leskovač (now in Yugoslavia) in connection with his role in helping his son evade the military draft.64

BOA İ.MVL. 25186.

OPC, Articles 68 and 213 (defamation).

A: . . . I made it because, in my fear, I thought: “I have done a really bad thing!” [i.e., by hiring a substitute]

Q: What were you afraid of, . . . that made you say those things?

A: It was on account of my own stupidity (budalalığımdan) and fear. I was afraid that they would put me in prison and would take my son away.

Halil's defensive strategy, in other words, was to claim that the crime of which he stood accused (the bribery story) was nothing but an “ignorant” knee-jerk reaction to his realization that he had failed to follow proper procedure in the substitution (“I have done a really bad thing.”). That defense proved to be effective. The central criminal court of the Danube province recommended that his punishment be reduced from the six-year imprisonment (kalebendlik) term prescribed by the OPC to the much lighter one of exile (nefy) for two years to a place within the same district. The reasons for that leniency were precisely those emphasized by Halil's self-defense: “paternal devotion,” combined with “ignorance of the law.”66

Hasbelءebu-i şefkatinden ve ahkâm-i kanuniyeyi ârif olmamasından.

I find it intriguing that Halil presented his motives for trying to “keep” his son in emotional rather than economic terms. Peasant resistance to military service is often interpreted along economic lines: nineteenth-century French peasants are said to have resorted en masse to buying off their sons from the army draft, simply because “labor [was] scarce and expensive.” (Eugen Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914 [Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1976], 293.) The potential loss of a son's labor and its implications to the household's economy may well have shaped Halil's actions as well—but economic explanations had no place in his choice of defensive strategy.

“Gullibility” defenses proved effective in numerous other cases. A married woman savvy enough to have juggled at least two simultaneous extra-marital affairs (one of them with the village priest) managed to convince the court that she was “ignorant” of the consequences of setting a neighbor's house on fire—the court ruled that, “being a woman [she] could not have known the provisions of the law” on that matter and substituted the death penalty prescribed for her actions by OPC with a ten-year imprisonment at a place “suitable for women.”68

BOA İ.MVL. 25852, Lefs. 42–50; incidentally, the reduction of the penalty because the offender was a woman, although commonly practiced, had no normative basis in the OPC; on the contrary, Article 43 stated that “no distinction shall be made between the two sexes as regards punishment.”

BOA İ.MVL. 26059.

The telling of exculpatory stories was another commonly used defensive strategy. Often, such stories followed the “property-defense” narrative model. In this model, the narrator's peaceful daily routine (plowing the fields, herding sheep, guarding a village forest, etc.) is interrupted by an intruder, who is usually an outsider such as an inhabitant of a neighboring village, or a member of an ethnic community popularly associated with crime.70

For example, the Roma (Gypsies) or Circassians. Ethnic stereotyping (especially against the Roma) was common among interrogators as well. One defendant's protestations of innocence were bluntly dismissed by court members with the following words: “Look here: you are a Gipsy (ulan, kıbtısın): don't waste our time [with your denials].” (BOA İ.MVL. 25897).

BOA İ.MVL. 24852, Lefs. 8–14 (a murder on an estate farm [çiftlik] near Sofia, in which three Bulgarian estate workers confronted three Circassians who allegedly had entered the çıftlik forest with the intent of stealing firewood; in the ensuing fight one Circassian was killed); BOA İ.MVL 24852, Lefs. 35–40 (two Bulgarian suspects caught up with some Circassians from a neighboring village who were allegedly in the process of stealing the Bulgarians' sheep; after a short chase the Bulgarians murdered two of the Circassians). In BOA İ.MVL. 25897, on the other hand, the “property-defense” model is reversed: this time the alleged intruder has killed the person who had caught him red-handed stealing—accordingly, the suspect's defense recasts the intruder as an innocent bystander, and the “quarrel” as a gratuitous assault by an overzealous property owner.

Trying to deflect blame away from oneself and redirect it towards one's enemies, accusers or, as the case might be, accomplices was another recurring defensive strategy. In modern legal jargon this may be called “credibility defense” and the accusations and counteraccusations involved in it provide us with treasure troves of information concerning local politics and the “fault lines” of village society. I have described two such cases in detail in the following section. For the time being, I would only stress that nizamî court suspects tended to construct their stories with reference to concrete Tanzimat reform policies. Thus, a certain Yusuf b. Emrullah, a suspected arsonist from the Nis district, explained that his fellow villagers bore a grudge against his family because: “we never stop working with the little that God has given us. That is why, when the government recently distributed paper money (kaime),72

This probably refers to the pre-1852 period, when Ottoman kaime was an interest-bearing treasury bill used as a governmental monetary tool for internal borrowing, rather than modern paper money proper. See Şevket Pamuk, A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 209–11.

BOA İ.MVL. 25852, Lefs. 36–41.

In one stroke, Yusuf emphasized both his family's disproportionate contribution to state finances and his enemies' petty jealousy at the family's economic success. In another case, a suspect conceded that he had indeed participated in the theft of livestock from his employer, but specified that his accomplices, and not himself, were the real instigators. The suspect illustrated his ambivalence towards the crime by describing the remorseful reflection (tefekkür) that had seized him after the sheep had been stolen—until finally he split from his accomplices and went into hiding.74

Natsionalna Biblioteka Kiril i Metodii: Orientalski Otdel (Sofia) (henceforth NBKM OO) Fond 169/694.

Occasionally, exculpatory strategies took the form of entire alternative accounts of the facts of the case. This was a road on which the suspects had to tread lightly, since it inevitably involved some form of denial of the interrogator's version of the crime. A suspect caught in the possession of forged coins testified that he had received these as change from someone else and had kept them, thinking they were “antiques” (antika).75

NBKM OO Fond 112A/1603. This may have been a “believable” story: the trade in antiques was a growth sector in the economy of the nineteenth-century Ottoman Balkans. See Khristo Khristov ed., Dokumenti za bûlgarskoto vûzrazhdane ot arkhiva na Stefan I. Verkovich, 1860–1893 (Sofia: Izdatelstvo na BAN, 1969).

BOA İ.MVL. 25824.

BOA A.MKT.MVL. Dosya 275, Vesika 93 [11 Dec. 1865].

Even seemingly straightforward confessions were usually given a defensive twist. The most typical wording of a confession, “I/we yielded to the devil” (şeytana uydum/uyduk) suggested an attempt to dissociate oneself from the full extent of the blame.78

The use of this expression in the context of criminal confessions predates the Tanzimat period by several centuries. See Heyd, Studies, 244.

BOA A.MKT.MVL. Dosya 312, Vesika 47. [4 Mar. 1867].

Let us now turn from our general discussion of defensive strategies to a more detailed examination of two criminal cases which, in my view, illustrate the particularly skillful way in which Midhat Paşa's “subjects” managed to use the nizamî legal process in order embroil the state in their own local political struggles. The first case began on 27 December 1865, when the bodies of two Circassian immigrants were discovered in the vicinity of the Bulgarian village of Kapucuk, kaza Samokov (in the Rila mountains south of Sofia).80

All documents relating to the Kapucuk case: BOA İ.MVL. 24852; this archival unit also contains the correspondence for two other (unrelated) criminal cases.

In suretyship (kefalet) arrangements during the Ottoman “classical age,” a guarantor was chiefly responsible for ensuring that a person accused of a crime would be available to appear in court at a later date; Heyd, Studies, 238–40. In the Kapucuk case, the suretyship system functioned more like a communal check on “deviant” behavior—the guarantors, who had to be from among the “trusted and notable” (muءtemed ve muءteber) men in the village, were asked to provide either concrete alibis or statements of good character for each villager.

BOA İ.MVL. 24852, Lefs. 40–41.

Kapucuk was a typical mountain village, divided into several hamlets set some distance apart. Judging by the occupations of the arrestees, most villagers made a living as either shepherds or coal peddlers. The most prominent village notable, and a pivotal figure in the case, was one Anguel çorbacı83

Çorbacı (Bulgarian: Chorbadzhiia) is a term commonly used to refer to Bulgarian village or town notables during the Ottoman period (especially the nineteenth century.) See Georgi Pletnءhov, Chorbadzhiite i bûlgarskata natsionalna revoliutsiia (Veliko Tûrnovo: Vital, 1993); Milena Stefanova, Kniga za bûlgaskite Chorbadzhii (Sofia: Universitetsko izdatelstvo ‘Sv. Kliment Okhridski,’ 1998); Mikhail Grûncharov, Chorbadzhiistvoto i bûlgarskoto obshtestvo prez Vûzrazhdaneto (Sofia: Universitetsko izdatelstvo ‘Sv. Kliment Okhridski,’1999).

The relatives did initiate şerءHî lawsuits after the nizamî interrogations were over. The protocols of these şerءHî hearings (BOA İ.MVL. 24852, Lefs. 38–39) are dated 24 January 1866.

The first man to testify was Anguel çorbacı himself. An endnote to his interrogation protocol reveals that he was not summoned as a witness in the case, but came to court secretly (hafiyen) and of his own accord. On that occasion, Anguel volunteered to become a guarantor for three of the nineteen men then in custody, but emphatically refused to vouch for the trustworthiness of the remaining sixteen. That begged the question:

Q: Why would you not become [their] guarantor? Are these bad men?

A: These are not good men. They do not listen to me; they do things as they see fit.

Q: In what way do they not listen to you?

A: They did not listen to me when the Sultan's road was being built!

Out of the sixteen villagers who had allegedly shown such “road-building disobedience” (yol kazmakta adem-i itaat), Anguel singled out three as especially “suspicious.” In the end, it was these three men who were convicted of the crime.

The sixteen villagers to whom Anguel refused to become guarantor saw the events surrounding the investigation in a rather different light. Almost unanimously they testified that the çorbacı and his henchmen were using the lawsuit in order to settle old scores. The suspects described the suretyship episode as a chaotic affair: three of them claimed that they had found guarantors from among “the people,” whom the authorities had refused to recognize as legitimate; one said that he had been apprehended after becoming separated from his chosen guarantor “in the mêlée” (kalabalıkta); another testified that he had arrived late in the village (since he lived in a remote hamlet) and was therefore summarily arrested. One arrestee spoke for all when he described his frustration in the following terms:

A: I have no knowledge of this matter. But I know [this:] they gathered together and arrested us poor people, [while] the çorbacıs are walking around [free]. It is them you should bring here and interrogate! Even if I stay imprisoned here like this for five years, I would still know nothing

For our purposes, the most significant part of these men's testimony was their explanation of Anguel's refusal to vouch for their innocence. Most claimed that the village notable bore a “grudge” (garaz) against them and at least four described the reasons for this grudge in virtually the same words: “he would not become our guarantor because he wanted us to sell our sheep to him cheaply, and we did not agree.”85

Bizden ucuz hayvan satın almak isteyüb vermediğimizden kefil olmıyor.

Let us analyze this exchange of recriminations between Anguel and the sixteen suspects. Certainly, both sides formulated their claims so as to make them believable in the eyes of the interrogators. What I find more intriguing is that both narratives were linked to concrete aspects of the reform program that was being implemented in the vilayet of Danube:

(a) The villagers' allegation that Anguel had tried to buy their sheep at below-market prices can be linked to recent changes in the government policy of assessing the small livestock tax (ağnam resmi). Like other rusumat taxes, the ağnam resmi underwent a process of “regularization” and monetarization during the Tanzimat period. In 1840, a uniform tax rate per sheep/goat was set up throughout the empire, although in practice regional rate variations persisted. In 1856–1857, the tax assessment policy was changed again in order to recognize the wide variations in the market prices throughout the empire. Henceforth, the ağnam resmi tax rate would be announced yearly for each region based upon annual surveys of the local market prices.86

Feridun Emecen, “Ağnam Resmi,” in İslâm Ansiklopedisi (İstanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı, 1988), vol. 1, 478–79.

(b) Anguel, on the other hand, tried to undermine the detainees' standing by claiming that they had resisted participating in the government's road building program. This initiative was arguably Midhat Paşa's most cherished pet project. In 1865, the Paşa instituted a compulsory annual road-building labor service for most adult males in the Danube province. By 1868, more than 3,000 km of new roads and some 1,400 new bridges had been built.87

Pletnءov, Politikata , 106–13.

It may be objected that I have misrepresented stories that could have been factually true as elaborate schemes to achieve this or that litigant's goal. In fact, there is no contradiction here: even if Anguel had indeed tried to extort cheaper sheep from his fellow villagers, his opponents nevertheless faced real discursive choices in telling that story. And, vice versa, even if the sixteen suspects had indeed failed to report for their road-building service, Anguel's choice to highlight that particular offense of theirs remains significant. The broad outlines of these stories may appear “traditional,”88

For example, the villager's portrayal of Anguel as an exploitative and vindictive tyrant followed the familiar trope of the idealized Ottoman state as protector of its primary producers/taxpayers from the encroachments of corrupt local strong men (a.k.a. “the circle of justice”). See Metin Heper, The State Tradition in Turkey (Northgate: The Eothen Press, 1985) 25–26.

From the point of view of a small village, such as Kapucuk, the case of the two dead Circassians undoubtedly represented an episode of heightened intrusion by the imperial government into local life. For a brief moment in time, the Ottoman state had come to Kapucuk—literally through dispatching the Samokov meclis representatives and figuratively through the process of interrogation which looked inquisitively into the minutiae of local conflict. And the fact that the state “listened” also meant that it could it be won over and embroiled in village politics. Anguel, for example, professed his shame that such a ghastly crime could have occurred “within our [village's] borders”89

Fear of communal punishment, rather than shame, may have motivated Anguel's actions. Collective punishment is a well-known şerءHî penal provision (Heyd, Studies, 308–9). In principle, the practice was discontinued during the Tanzimat period (OPC contains no reference to it); in reality, there were attempts to reintroduce it in certain specific cases—in 1868, for instance, a printed proclamation informed the citizens of the Danube vilayet that henceforth the responsibility for payment of damages for arson would be shared by “the whole village” if the arsonist was not found (NBKM OO Fond 112A/2204.)

Michel Foucault, “Two Lectures,” in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 96.

We can see similar strategies at work in another case focused on another deeply divided village: Bebrovo, tucked away in the northern folds of the main Balkan range in the region of Veliko Tûrnovo (north-central Bulgaria). There an intriguing, if slightly farcical, series of accusations and counter-accusations took place in the winter of 1865.91

All documents relating to this case: BOA İ.MVL. 23896.

Stefan had claimed that the “poisoning” had taken place on the evening of 31 January 1865, at an informal meeting of some villagers at the müdür's house. Necib had ordered coffee for his guests and the local coffee-maker was carrying around a tray full of coffee cups. When Stefan's turn to take a cup had come, the coffee-maker allegedly steered Stefan's hand towards a “specially marked” portion. Taking a sip, Stefan said he felt a burning sensation in his mouth and throat and immediately realized he had been poisoned. He then allegedly stumbled out of Necib's house, felt extremely sick and repeatedly vomited along his way home, leaving him in no doubt that he had been the victim of an elaborate and pernicious plot masterminded by the müdür. Unfortunately for Stefan, witness testimony to confirm his story was not forthcoming. His neighbors did say that Stefan had seemed unwell that night, but they also suggested that his vomiting may have been induced by the baking soda solution he had taken (presumably as an antidote). The witnesses also reported several instances surrounding the incident, during which Stefan's behavior had been, to say the least, bizarre: he had, for example, the presence of mind to dispatch his wife, daughter, and son-in-law back to Necib's house, instructing them to look for the regurgitated matter he had left behind and collect it as evidence! (He was convinced that “his enemies” would have already buried or otherwise concealed these traces of their crime; and indeed, his relatives found nothing.) On the following morning, Stefan (now miraculously recovered) confronted some villagers at the coffeehouse and insisted on showing them “traces” of the poison on his tongue—traces that remained invisible to everyone but himself. The witnesses were unanimous on one point: Stefan had stayed at Necib's house until the end of the soiree, taking not one but up to three cups of coffee and leaving in visibly good health. The coffee-maker summed up the matter rather generously by calling Stefan “an old man whose memory has failed him.”

Why, then, did it take a run through the entire Ottoman judicial system to resolve a case where all the evidence pointed in one direction? In fact, Stefan's guilt was never the issue—the problem was that, in the course of the investigation, it became clear that the “poisoning” episode was but a symptom of a deeper and, from the government's perspective, more worrying malaise that was affecting the village of Bebrovo.

The interrogations were concluded on 13 February 1865. On 8 March the criminal court of Veliko Tûrnovo acquitted all defendants and found Stefan guilty of defamation. Pursuant to articles 168 and 213 of the Penal Code the court recommended a sentence of hard labor for three years. That opinion was seconded by the provincial criminal court in Ruse (7 April) and seemed headed for another routine review and implementation by the governor. Midhat Paşa, however, refused to rubberstamp the court decision. Instead, he produced a petition sent to him by some twenty inhabitants of Bebrovo (including Stefan and the current mayor, Kolyo) and directed against Necib Ağa and his clique. That document is written in Bulgarian and is dated 30 January 1865—the day before the “poisoning” episode occurred. The petition claimed to speak on behalf of all inhabitants of Bebrovo, whom it described as “oppressed and extremely frustrated” by Necib and his three aides—Khadzhi Stancho, Shishko Petre, and Simeon. The members of this “wicked” quartet were compared to “Janissaries”—a politically explosive term, since Sultan Mahmud II's destruction of the notorious Janissary corps (1826) was celebrated during the Tanzimat period as “the Auspicious Event” (Vakءa-i Hayriye) and was regarded as the historical sine qua non of Ottoman reforms. The petitioners claimed that Necib, Stancho, Petre, and Simeon had usurped for a number of years all the key intermediary posts between state and village society in Bebrovo, Necib serving as kaza superintendent and his cronies rotating as mayors (muhtar), village treasurers (kabzımal), and collectors of various taxes for the state (tahsildar) or for the church (epitrop). The result was, allegedly, the embezzlement and dissipation of both state revenue92

Bulgarian: tsarshtinata, i.e., what belongs to the Tsar (Sultan).

Bulgarian: siromashiiata, i.e., what belongs to the poor people.

Two days ago, we received the mayoral signet seals for the outlying neighborhoods of our village. Before giving these seals to the villagers, Necib Ağa and Khadzhi Stancho stamped them here and there for their own benefit. Some of the villagers objected [to that], but found themselves in trouble because these two raised hell, took the seals away from the chosen muhtars, selected instead some of their own followers and gave the seals to them, so that their own interests may be advanced. Thus they reshuffled the village elders' councils (ihtiyar meclisi) everywhere, against the villagers' wishes creating confusion and anxiety. Finally, today they planned to do the same in Bebrevo itself [as opposed to the outlying hamlets]: they reshuffled the twelve members of ihtiyar meclisi, created a panic at the government building, apprehended our mayor and demanded our seals—all against the wishes of the people.

This paragraph holds the key to understanding the conflict in Bebrovo. The village was not split along class or ethnic lines.94

The petitioners' claims to represent the “poor people” of Bebrovo should not be misconstrued in class terms: all but one of the signatories of the petition were wealthy enough to possess personal seals, all were literate (as evidenced by handwritten signatures), three were priests, two were khadjis (i.e., had performed the pilgrimage to Jerusalem) and one (Kolyo) was the local mayor. The conflict was not an ethnic one either, nor was it presented as such—the petition was aimed equally against the Albanian müdür and his Bulgarian henchmen.

Ortaylı, Tanzimat Devrinde Osmanlı Mahallî İdareleri, 98–101.

Muhtar-i evvel-i karye-i Bebrova. This is indeed one of the seals with which the petition against Necib is signed; it is only during the interrogations that we learn the name (Kolyo) of the actual person behind this seal.

Midhat Paşa seems to have read the petition along these lines. His letter to the Supreme Court in İstanbul recommended that Stefan's penalty be reduced from hard labor to the much lighter one of temporary exile. The Paşa conceded that Stefan was indeed an “objectionable and seditious” (uygunsuz ve müfsid) man deserving of some sort of punishment. Yet this punishment, Midhat argued, should not be based on the full severity of the Penal Code's provisions because Stefan's accusations belonged in the domain of “private law.”97

hukuk-i şahsiye. The term usually refers to the sharia, although in this case there is no evidence that Stefan ever filed a şerءHî lawsuit against Necib. (Moreover, as Midhat's letter correctly noted, “private law” makes no provision for the crime of “slander” as such).

Although the governor's intervention was couched in legal terms, it was motivated by political considerations. The summary of the case published in the crime chronicle of Dunav explained the causes for the leniency shown Stefan in political terms as well: although unquestionably guilty of slander, he had been “seeking to establish his rights” against an unjust state official.98

Dunav I/18 [30 June 1865].

The Bebrovo petition proved to be an effective defensive weapon for Stefan. As we saw in the Kapucuk murder trials, purely local political conflicts could be presented in such terms as to elicit the sympathies of the reformist bureaucratic cadre staffing the nizamî courts. The Bebrovo petitioners did better that that—they managed to embroil no lesser a figure than the top provincial bureaucrat into their “micro-historical” conflict. Midhat was clearly more concerned about the allegations put forth in the petition than about any part of the “poisoning” case per se. As in Kapucuk, these allegations struck a nerve because they suggested that key reform policies were being sabotaged. And no matter how insignificant in scale, such sabotage could not be tolerated.

In defining “everyday forms of resistance,” James C. Scott suggested that his famous concept had two distinct (if overlapping) dimensions. On the one hand, there is the physical aspect of resistance made up of activities such as: “ . . . foot dragging, dissimulation, desertion, false compliance, pilfering, feigned ignorance, slander, arson, sabotage, and so on.” But these “Brechtian” or “Schweikian” acts of physical resistance do not tell the entire story: the struggle is not merely “over work, property rights, grain, and cash. It is also a struggle over the appropriation of symbols, a struggle over how the past and present shall be understood and labeled, a struggle to identify causes and assess blame, a contentious effort to give partisan meaning to local history.”99

James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), xvi–xvii.

The evidence I have presented above contains, for the most part, descriptions of behavior that fits into the category not of “resistance,” but of its opposite—compliance. As a particular type of relationship between individuals and political power, compliance makes for a notoriously difficult historiographical subject since writing about it necessarily involves assessments of such intangibles as personal motivation and “willingness” (resistance, on the other hand, never seems to need a motivation). As an illustration, one only needs to recall the controversy caused by Daniel Goldhagen's recent book which attempted to make a specific claim regarding the nature of “ordinary” Germans compliance with the Third Reich's extermination project.100

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (New York: Vintage, 1997).

This argument is influenced by Ussama Makdisi's incisive analysis of the “crisis in Ottoman representation” in his The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 105–8.

Methodologically, then, the contribution of this paper has been to examine the system of “dual trial” not on the basis of its normative texts, but on the level of practice. As we saw, the nizamî court records of the Danube province in the 1860s abound with references to legal procedures, practices, and arguments that fell outside the provisions of the 1856 Penal Code, which was largely the “blueprint” for the system. In its application, the law proved to be much less monolithic than in its letter, largely because of the great skill with which litigants throughout the social spectrum deployed key elements of the Tanzimat discourse in their defensive (and offensive) legal strategies.

The ability and willingness of Midhat Paşa's subjects to play the new interrogation game constitute the most important empirical finding of the present study. There is no evidence that popular attitudes to the new criminal justice system were split along ethnic or religious lines. Specifically, despite the national meta-narrative's expectations to the contrary, there is nothing to suggest that the ethnic Bulgarian inhabitants of the province shied away from the new legal opportunities provided by the nizamî courts or in any way regarded the reformed Ottoman justice system as illegitimate or teetering on the brink of collapse. On the contrary, the fact that the Bulgarians in the province learned the complex rules of the nizamî interrogation so quickly suggests that, at least into the late 1860s, most of them regarded the imperial framework of which the interrogations were a part as a political arrangement that was likely to endure in the foreseeable future.