INTRODUCTION

The once-glorious seat of the Ottoman Empire resembled a sprawling refugee camp in the immediate aftermath of World War I. Several tragedies pulled groups of Greeks, Turks, Russians, Armenians, and others to Constantinople/Istanbul from various locations including Thrace, Anatolia, Levant, Mesopotamia, and southern Russia. Among the camps that sheltered the survivors of the 1915 Armenian genocide, the one in Galata served as the makeshift home of a teenaged girl who had spent the war years among Muslims. Like many of her counterparts, she had been kidnapped and raped. After the Ottoman defeat was sealed by the Mudros Armistice in October 1918, an unknown set of developments had led her to the capital. She may have been rescued by the Armenian relief organizations, or freed by her abductor, or perhaps she had escaped. Be that as it may, she was heavy with child, conceived by the man who had first forced her former fiancée, an Armenian, to witness her violation, and then killed him.

In Allies-occupied Istanbul and under the institutional care of fellow Armenians, she tried every means possible to terminate the pregnancy. Sometime in her first trimester she reached the house of a fellow Armenian woman, Zaruhi Kalemkiarian, who would later tell of her in her memoirs.Footnote 1 I will refer to this “girl” as X, since Kalemkiarian did not provide her name. X pleaded with Kalemkiarian to help her get an abortion (vizhoum), but despite her deep sympathy for the girl, Kalemkiarian refused to help, even after X began visiting her house every day, banging her head on the wooden floor in an attempt to injure herself since “her soul was fired up with the need to curse and take revenge.”Footnote 2

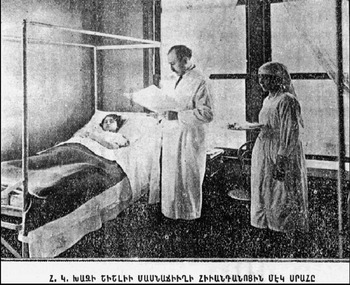

X sought out Kalemkiarian's help because she was one of the founders of the Armenian Red Cross, which operated a hospital where X could possibly get an abortion. Instead, alarmed that X might commit infanticide, Kalemkiarian and other khnamagal diginner (female relief workers) ordered her incarcerated in the maternity ward of the Armenian Red Cross Şişli branch hospital (see Image 1). This ward only housed “forlorn young mothers” (anderunch yeridasart mayrer), refugees expecting babies of Muslim fatherhood.Footnote 3 In that “special” ward, within hours of giving birth to a healthy boy, X committed suicide. Despite the customary practice of the shared nursing of infants, other mothers cursed the newborn by collectively refusing to nurse him. Kalemkiarian does not record the baby's fate.

Why did the Armenian authorities deny X an abortion?Footnote 4 Why did the expectant mother's perception of the fetus as “the continuation of the vojrakordz (criminal)” conflict so profoundly with what Kalemkiarian and other relief workers saw in such babies, whose “chirping cries elevated [their] souls.”Footnote 5 At first glance, Kalemkiarian's view may seem puzzling because both Muslims and Christians had long believed, and the law endorsed, that a baby belonged to its father and his group. Yet the Armenian National Relief Committee, the umbrella organization in charge of providing relief to refugees in Istanbul, referred to babies of Muslim fatherhood as “our orphans” (mer vorpere). What conditioned the decision to render fatherhood irrelevant in determining Armenianness?

Image 1: A ward at the Armenian Red Cross Şişli hospital, date unknown. Source: Biennial Report of the Armenian Red Cross in Constantinople (dissolved in 1922) covering the period 18 Nov. 1918 to 31 Dec. 1920; Yergamya Deghegakir H. G. Khachi Getr. Varchoutyan, 1918 Noy. 18–1920 Teg. 31 (Constantinople: M. Hovagimian, 1921), 30; Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate Library.

I answer this question in the context of immediate postwar era (1918–1922) Istanbul. My research is grounded in institutional reports, Ottoman state and Armenian Patriarchate archives, writings in the Armenian and Turkish press, unpublished private papers of intellectuals, and memoirs. I begin with the gendered and age-conscious orchestration of the Armenian genocide as well as the Ottoman historical repertoire that rendered such policies—particularly the abduction of women and children—possible and effective. I then turn to the immediate postwar era during which the Allies occupied the defeated Ottoman capital. When the Great Powers convened in Paris to redraw the world map, one section on that map was claimed by Armenians and Turks alike. International diplomacy, revolving around the Wilsonian principle of self-determination, inextricably linked territorial claims to demographics, and this led Armenians and Turks to take all possible measures to increase their ranks. The intersection of this political context with the shared symbolic and functional importance of women and children for each group engendered not only a postwar Armenian effort to rescue the abducted, but also fierce fights about who belonged where. The rescue effort was sometimes aggressive, and rape victims and babies of Muslim fatherhood were officially welcomed into the new coordinates of Armenian collectivity. I will demonstrate that these actions, in addition to exemplifying a common post-genocidal victim response, were intended to reverse the results of extermination campaigns and also represented a conscious choice on the part of Armenian leaders striving to revive their nation and their state.Footnote 6

This analysis of a metamorphosis of rules of ethno-religious belonging provides a striking example of how, under certain circumstances, patriarchy may relax one of its central tenets—the primacy of paternity over maternity. But this did not translate into women's agency in determining group belonging. On the contrary, Armenian rescue efforts left the target population with few options for controlling their own lives and bodies, and far from subverting patriarchal norms they reproduced patriarchal hierarchies and left intact long-established assumptions about women's nature, culture, and potential.

A CLIMATE FOR ABDUCTION: ARMENIAN WOMEN AND THEIR CHILDREN DURING WORLD WAR I

The Ottoman Turkish state's campaign to get rid of its Armenian population involved a variety of strategies, all sex-selective and age-sensitive. The goal was to destroy Armenianness and prevent its reproduction in the future, and this did not require the wholesale killing of every human being considered Armenian, but only annihilation of those who had or carried the capacity to transmit Armenianness. Hence the general, though by no means universal tendency in the first stage of the process to massacre adult men. Groups incapable of passing on an Armenian ethno-religious identity could be spared death, and even put to good use; hence the cooptation of female bodies and appropriation of small children of both sexes. This strategy, which has been a common means of destruction in many other demographic engineering projects, would not only mitigate depopulation from war, deportation, and massacres, but would also offer incentives to mass participation in the genocidal process.Footnote 7 The “spoils of war” would include plundering of Armenian property as well as near-free access to females and minors. In short, following its centuries-old tradition of pragmatism in domestic and foreign policy, the Ottoman ruling party, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), known as the Young Turks, created the conditions for, allowed, and openly encouraged Ottoman Muslim households (Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Circassians, Chechens, Gypsies, and émigrés from the Balkans) to incorporate Armenian women and children, and to a lesser extent those of other Christians groups such as Greeks and Assyrians.Footnote 8 Following a metamorphosis, these groups would be remade into proper Ottoman Muslims and cease to threaten the Young Turks' final solution: population homogeneity.

The systematic nature of this strategy has yet to be studied adequately,Footnote 9 yet there is ample evidence, particularly in Ottoman state correspondence, that it was calculated state policy.Footnote 10 The Interior Ministry, the state branch entrusted with coordinating the “Temporary Law of Deportations of Armenians,” issued a number of orders explaining the procedure regarding widowed and parentless young Armenians. A memorandum that Interior Minister Talat Pasha sent to various provinces and copied to the Minister of War Enver Pasha, on 30 April 1916, provides a snapshotFootnote 11:

(1) Those families who had been rendered kimsesiz [literally, “without any one,” in the sense of being unattended] and parentless (velisiz) because their men have been deported or currently serve in the Ottoman army [are] to be distributed (tevzî') to villages and towns without any foreigners or Armenians. Their living expenses are to be paid from the Refugees Fund (Muhacirîn Tahsîsâtı) and they are to be adjusted to the local customs (âdat-i mahalliye ile îstînaslarına).

(2) Young and widowed women [are] to be married off (tezvîclerine).

(3) Children up to the age of twelve [are] to be distributed to our orphanages.

(4) If orphanages are insufficient for this job, they shall be given to prominent, well-to-do (sâhib-i hâl) Muslims to be assimilated to local manners and ways of life (âdâb-ı mahallıye ile terbiye ve temsîllerine).

(5) If a sufficient number of such prominent Muslims cannot be found, effort should be made to distribute them to peasants with the assurance that every month 30 kurushes will be paid by the Refugees Fund. Lists of all these transactions [of the families who get children] are to be sent to the center periodically.Footnote 12

Analyzed in its totality, and in conjunction with press reports and memoirs, it is clear that the Young Turk policy regarding Armenian women and children created a climate for abduction wherein Ottoman Muslims were entitled to incorporate Armenians into their homes, businesses, farms, and state institutions. Armenians experienced this climate in different ways, depending on their geographical location as well as their luck. More massacres were wholesale toward the eastern border, in what Armenians considered to be their “historical homeland” and where they had been concentrated before the war. Toward the west and the south, the genocidal policy was usually more gendered and age-selective. A general trend was that while adult men were massacred, women, children, and older men were put on deportation routes toward the Mesopotamian deserts, typically by foot or by train.

Children were often separated from their female kin even before their caravans departed. Many girls and boys were quickly taken in by local Muslims or government personnel and transferred into specific households, mosques, schools, or orphanages. They were converted to Islam, and some were made available for local Muslims to pick from (at times in the presence of a medical doctor), while others were distributed. Still other mothers handed children over to trusted neighbors who promised to care for them until their return. Young women, including teenaged girls and newlywed mothers of young children, were commonly abducted right before the exodus of Armenians. Some women took the initiative and found a Muslim man to whom they would provide sexual services in return for protection from deportation, or to save their immediate kin.Footnote 13

The deportation convoys turned into death marches, and many of the elderly and the very young died early on. Women, girls, and young boys remained vulnerable to sexual violence and kidnapping.Footnote 14 Locals searching for goods, females, and children raided encampments. Often the gendarmerie supervising the caravans coordinated these raids, or simply turned a blind eye. Sometimes Armenians exchanged their children for money, food, or the protection of other family members.Footnote 15 Many young girls and women were captured to be prostituted or integrated into the eastern slave trade. That trade was energized during and after the genocide due to women and young girls being taken from Anatolia and sold in Arabia, a topic beyond this article's scope but in dire need of study.

In Muslim households, abducted boys usually served as slaves and/or servants tending the land. It was more common for boys than girls to be taken into institutions such as orphanages and military schools. Girls and women were usually absorbed into households, where they worked as domestic helpers, concubines, or wives. Typically, Armenians' assimilation would start with a change of religion, a new name, and usage of a predominant language (Kurdish, Turkish, Arabic, etc.). They were usually forbidden to mingle with other Armenian converts, though we know that this happened frequently, especially if a household took more than one Armenian.Footnote 16

Those in Istanbul lived through the war years quite differently than those in other Ottoman territories. Because of the capital's visibility to the European powers, the government did not order the mass deportation, slaughter, abduction, or assimilation of Constantinopolitan Armenians.Footnote 17 To prevent the mingling of other Anatolian Armenians with those in Istanbul, deportees were barred from entering the city. Similarly, the Interior Ministry forbade civil servants and military officers bringing any captive Armenians into Istanbul, perhaps to avoid their coming to the attention of resident Europeans.Footnote 18

The Interior Ministry organized the transfer to Istanbul of Anatolia's orphaned children—not just Armenian but also Greek, Kurdish, Turkish, and others—through the Society for the Employment of Ottoman Muslim Women (Kadınları Çalıştırma Cemiyet-i İslâmiyesi), established in 1916 by the Minister of War Enver Pasha to encourage the entry of Ottoman Muslim women into the workforce. Since the number of orphans—about sixteen thousand in the war's first year—was far above what Istanbul's orphanages could shelter, the Society found a more permanent solution: girls were distributed to Muslim households selected by the Interior Ministry, and boys were given away to factories, workshops, ranches, and small businesses in both Istanbul and Anatolia.Footnote 19 Regardless of their ethnic origin, and though it was known that many of them were Armenians, all were either assumed to be Muslims or had to go through conversion.

Turkish official and nationalist historiography claims that this ethnicity-blind policy of incorporation demonstrates that the Ottoman state was benevolent even toward non-Muslims. Rather than a policy of kidnapping, the argument runs, this should be seen as a rescue operation.Footnote 20 There is no question that many Armenian children evaded certain death thanks to the Muslim families or institutions to which they were transferred. Yet the precondition for their survival was that they stop being Armenian, which exposes a motive other than humanitarianism. None of the Anatolian orphans transferred to Istanbul were given away to native Christian or Jewish families, of whom there were many in the capital, nor were they hosted in any of Istanbul's Christian orphanages. Although many Ottoman Muslims welcomed Armenians in their households out of pity and took excellent care of them, the orders from the center and their implementation on the ground reveal a policy that we might call “abduction for extinction.” The process resembled how boarding schools for Native American children were meant to turn them into “civilized” Americans.Footnote 21

What historical repertoire enabled Ottoman politicians to conceive this policy, and what made the Muslim population implement it so effectively? These questions are important to ask because their answers will illuminate postwar Armenian responses to those previously abducted, and their progeny. First of all, in the Ottoman Empire, populations were organized according to their religions, at least until the very end of the empire. This perspective was very different from that which fueled the Holocaust, because according to “this logic ‘Armenianness’ to the Turks [was] less indelibly fixed than ‘Jewishness’ would be to the profoundly racist Nazis.”Footnote 22 During the Holocaust, pregnant Jewish women or those with young children were among the first targets for elimination. Rape was officially forbidden, and when it did happen Jewish victims were usually killed in order to prevent “racial pollution/defilement.”

By the beginning of the Great War, Committee of Union and Progress leaders had become increasingly radical and did use racist vocabulary. Anatolian Armenians were frequently referred to as “tumors” requiring an operation, as “leeches” feeding on the Muslims, or as “microbes within the organism of the fatherland” that had to be eliminated for good.Footnote 23 Yet such terminology did not preclude conception and implementation of policies based on the assumption that the difference between groups were not innate and indelible, but rather changeable. The blood of Armenian women and young children was seen to be devoid of the capacity to pollute the Muslim nation because it had no agency or consequence. According to the patrilineal and patrilocal tradition shared by both Christian and Muslim Ottomans, any child a woman bore automatically belonged to the father's family and his community. As Carol Delaney maintained in light of her fieldwork in a Turkish village, women were thought to have no role whatsoever in procreation. This expresses the shared logic of paternity in Islam and Christianity, within which a monogenetic mentality dictates that the father is the sole creator. Women do contribute physiologically to the child, but in no way are they thought to engender it.Footnote 24 The womb is reduced to an empty vessel (or a field) that takes the shape and form of whatever fluid fills it (i.e., the seed).

Ottoman history is replete with examples that demonstrate how women and young children were regarded as re-programmable therefore valuable. The Islamic Hanafi School of law that the Ottomans adopted expressed this mentality by allowing Muslim men to marry non-Muslim women but forbidding non-Muslim men to marry Muslim women.Footnote 25 During the empire's six hundred years of continuous rule, the sultans practiced ethnic and religious exogamy. Except for a few instances in the first centuries, none of the royal consorts were Muslim or Turkish by birth. Even though almost all sultans' mothers were originally Christians, the empire's subjects never thought to question the Muslimness of the ruling family. Since according to Islamic tradition a man's child by a slave is considered legitimate (unlike Euro-American laws of bastardy), slave concubinage remained a preferred mode of royal reproduction.Footnote 26 Partnering sexually with non-Muslim slaves was advantageous because slaves lacked lineage—an extended family entitled to intervene in the royal household and potentially in Ottoman politics.

The motives of Ottoman Muslim men in picking or abducting an Armenian for marriage were probably not so different from those of the sultans—they would evade paying brideprice and get a wife deprived of the precious support of a natal family. Some sources suggest that Armenian females were in high demand since both the Muslim locals and politicians considered them to be more beautiful, advanced, and educated, and even more Westernized than Muslim women.Footnote 27 The most common practical motive for obtaining an Armenian female, however, was that she was free, exploitable labor, and Ottoman households were accustomed to the practice. Many middle-class and upper-class families, both Christian and Muslim, had fostered children (besleme or evlatlık), usually girls, and raised them to become household servants. Foster-daughters served as unpaid domestics to masters who considered themselves “charitable” since they were feeding, sheltering, and clothing a soul who would have perished otherwise.Footnote 28 It is quite likely that during the Great War Ottoman Muslims who abducted Armenians (or “protected/rescued” them, depending on one's reading) made sense of the process in terms of their own generosity. Moreover, the Ottoman government gave incentive to this transfer either by agreeing to pay those who took in an Armenian orphan, or by transferring the orphans' deceased parents' property to his or her new Muslim family.Footnote 29

Another foundational Ottoman practice, the devshirme, serves as a quintessential example of the Ottoman state's deep trust in children's potential for acculturation. In this child-levy system, Ottomans recruited young Christian boys, usually from the Balkans, converted them to Islam, assimilated them to Muslim traditions, and trained and enrolled them in high imperial institutions, including the palace and the military. This system was intended to prevent the formation of nobility that would compete for janissaries' loyalty. In other words, even though the goal was not to increase the Muslim population by eliminating or converting non-Muslims, the devshirme system functioned to turn non-Muslim boys into Muslim men.

Abduction, both by the sultan himself and of commoners, had long been practiced in the Ottoman lands, even before the arrival of Turks. Abduction asserted power, valor, masculinity, and courage and had a meaning that both victims and abductors knew well: it shamed the abductees and dishonored their families, communities, and nation.Footnote 30 “Lesser” abductions of girls and women were usually carried out for sex and marriage, while most boys were taken to incorporate into potentially rebellious brigand gangs, as what are now called “child soldiers.” The latter practice led the state, beginning in the sixteenth century, to add the punishment of castration for the crime of abduction.Footnote 31 Yet sultans themselves abducted; “heroic” abductions, whereby a sultan took an enemy leader's wife or children captive, were considered the ultimate victory, and this practice in turn legitimized Ottoman soldiers' taking many captives as war booty.

Even before the Interior Ministry's orders regarding Armenian women and children reached the authorities, perpetrators and victims alike knew that the long journey south would involve pervasive violations and snatchings of persons. Everyone would have recalled the Hamidian massacres (1895–1897), during which men were killed, property looted, and women and children kidnapped. In its aftermath, and as a result of growing pressure from the French and British consuls, the state had sent a commission of inquiry to the provinces to investigate Christian captives in Muslim households. Even the head of the commission, Abdullah Paşa, concluded that Arif Efendi, a local Kurdish leader and influential organizer of the massacres and abductions, had to be exiled “as an example to others of like mind.” The Ottoman government, however, refused to exile him, and instead suggested to Abdullah Paşa that “he remove himself temporarily to Mosul.”Footnote 32 Only a tiny fraction of those kidnapped was rescued. The “meddling” of the foreigners proved unhelpful since the sultan remained the absolute leader of an influential state that mattered to European powers.

In the immediate aftermath of World War I, the defeated Ottoman state looked very different, however. As early as May 1915, the Entente had warned the Sublime Porte that the Ottoman government would be held responsible for the massacres and the “fresh crimes committed by Turkey.”Footnote 33 The Young Turk leaders escaped the country on 1 November 1918. The new government ordered that all “Christian girls and children that had been kept by force (cebren) in Muslim households be freed and returned to their relatives.”Footnote 34 Worded with the hope of mitigating the terms of the Armistice, signed nine days later, the order warned that forcibly taking captives was “against the high stakes of our fatherland and violates our Constitution [Kânûn-i Esâsî' of 1876] which grants personal freedom to everyone regardless of religion and sect.” Those who were refusing to return their captives, the document continued, “could lead to accusations against the Ottomans. Therefore this should not happen again and must stop immediately.”Footnote 35

The signing of the Mudros Armistice sealed the Ottoman defeat and initiated a new political climate in which Armenians could rescue or be rescued. It stipulated the release of Ottoman prisoners of war, a clause that everyone interpreted to include Islamized women and children. Deported Armenians were given the right to return to their original hometowns. Soon after, the Allies occupied Istanbul and parts of Anatolia. The exiled Patriarch Zaven Der Yeghiayan returned to the capital in February of 1919 and resumed his duties as the head of the Armenian millet (ethno-religious community). The Armenian National Assembly, a semi-autonomous parliament composed of elected clerical and laymen that had overseen Armenian affairs since the 1860s, reopened. One of the first responsibilities that the Patriarch took upon himself was the liberation (azadakrum) of Islamized Armenians; he had to come up with resources and personnel, and the logistics and a policy to run the rescue operation. I now turn to explore this effort, after which I will detail debates between Turkish and Armenian authorities over the “true” identity of war widows and children.

A CLIMATE FOR REDEMPTION? THE ARMENIAN RESCUE EFFORT (VORPAHAVAK) IN ISTANBUL

Armenians' campaigns to find, liberate, and reintegrate children and women sequestered in Muslim households and orphanages were collectively called “vorpahavak”—“the gathering of orphans” in Armenian. Here the term “orphan” (vorp) referred to not only children without one or both parents but also women who lacked a surviving male family member. Rather than age or sex, orphanhood connoted the absence of a dependable male relative, and was thus translated to and from Turkish as bi-kes, kimsesiz, or sahipsiz (unprotected, unclaimed, or forlorn), in addition to yetim (fatherless orphan) and öksüz (motherless orphan).

The vorpahavak in Istanbul began after the Mudros Armistice, but in the Sinai, Palestine, Syria, and Iraq it started in late 1917, after the British arrived.Footnote 36 In Istanbul, the Patriarchate created and financially supported an Orphan Gathering Agency (Vorphavak Marmin) composed of a supervisor—Arakel Chakerian, a Paris-educated professor of chemistry at the University of Istanbul—and four young men personally known to and trusted by the Patriarch.Footnote 37 Some young girls and women were also employed to facilitate easier and more respectful access to Muslim places.Footnote 38 The British Embassy gave each vorpahavak agent a letter of introduction addressed to the allied police force asking them to provide assistance if needed. The British also facilitated the requisition of former Turkish pashas' residences for sheltering the rescued. The Armenian Red Cross, founded and operated by native Constantinopolitan elite women, supervised the operations of most of the shelters. According to the memoirs of the Patriarch, until the end of 1922 vorpahavak agents in Istanbul retrieved about three thousand of the five thousand kidnapped Armenians.Footnote 39

The Sèvres Treaty, the first postwar peace treaty the Ottomans signed with the Allies (later superseded by the 1923 Lausanne Treaty), further boosted vorpahavak efforts. It not only annulled all conversions to Islam between 1914 and 1918, but also required the Ottoman Turkish government to assist in all efforts to find those concerned and deliver them back to their original communities. The newly formed League of Nations, too, became involved in uniting Near Eastern families torn apart by the war.Footnote 40 Beginning in 1922, the League's Commission of Inquiry for the Protection of Women and Children in the Near East carried out rescue operations in Istanbul and Aleppo, and opened shelters; from 1922 to 1926, it rescued four thousand adults and four thousand children, the majority of them Armenians.Footnote 41

Especially in the months immediately following the Mudros Armistice and the de jure occupation of Istanbul, the Ottoman government remained supportive of the vorpahavak.Footnote 42 Orders were sent to the provinces warning those who kept Armenians in their homes to surrender them to the authorities within a week's time, and that those who hid their Armenians would be punished severely. Armenians could be handed over to church authorities or, in their absence, to the local police department.Footnote 43 These warnings found receptive ears, and during the first months after the Armistice some Turkish/Muslim families voluntarily gave their Armenians to the Patriarchate.Footnote 44

However, as 1919 unfolded the government's support of vorpahavak diminished, and at times it turned openly hostile to it. Many Armenians now had to be extracted forcibly. The shift was both a response to and an indication of the changing political conditions. The last sultan Vahdettin's anti-CUP policies, aimed at appeasing the Entente, lost credibility after the Greeks occupied western Anatolia in May 1919. The Turkish nationalist movement in Anatolia, which had been growing since the Armistice, was now organized around the leadership of Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) and was becoming increasingly anti-Armenian and anti-Greek. Moreover, as early as February 1919 the Muslim populations and the government became concerned that Armenians were retrieving and Armenianizing Muslim orphans, a topic to which I shall return.Footnote 45

Vorpahavak agents knew the location of Armenian orphans through a variety of sources. Most importantly, Arakel Chakerian reclaimed the registry books of the Society for the Employment of Muslim Women (Kadınları Çalıştırma Cemiyeti İslâmiyesi) in Istanbul. In them he was able to find the names of the Islamized children since their parents' Armenian names were still visible despite having been partially erased and overwritten with Turkish names.Footnote 46 Other orphans were located by following intelligence provided by neighbors and relatives, and rescued Armenians often supplied information on other captives.Footnote 47 Quite often, Islamized Armenians, hearing of the ongoing vorpahavak initiatives, found the courage and means to escape to the nearest shelter. Sometimes vorpahavaks found Greek children and returned them to the Greek Patriarchate, which was engaged in a similar operation to retrieve Islamized Greek Orthodox orphans.Footnote 48

A problem that deeply troubled both Greek and Armenian rescue efforts was those persons who refused to be rescued. Many “captives” wanted to remain where they were. Research conducted in different parts of the world suggests that abducted people often resist being forcibly returned to their natal communities. This is most common when they have assimilated relatively well into the abductors' group and suffer no severe discrimination there, when they have spent several years away, and when they foresee being stigmatized if they return. Many abducted women in both India and Pakistan resisted efforts to “liberate” them from households into which they were forcibly integrated during the 1947 Partition. Similarly, many white women and children held captive by Native Americans were reluctant to return to white society. These situations contrast sharply with those conflicts, such as in central and West Africa, in which kidnapped girls have been isolated and confined in huts to serve as sex slaves, and have usually welcomed rescue efforts.Footnote 49

We can begin to understand why some women and children resisted re-Armenianization through eyewitness testimonies, memoirs, and oral history interviews, and also a report prepared in March 1919 for the Armenian National Delegation in Paris.Footnote 50 Their abduction, loss of chastity, abuse at enemy hands, or having had a child by an enemy man constituted such deep disgrace that many married women did not want to leave their relatively bearable situations for lives of certain stigmatization back in their native communities.Footnote 51 Those who had converted to Islam, even at gunpoint, and even men, were seen to have blackened their group's name.Footnote 52 Some assumed that Armenians would refuse to accept their “Muslim” children and did not want to leave them behind. Most knew they had no family to return to. Many had been purchased or saved from the gendarmes by “peaceful Muslims who ensured them a relatively tolerable life,” for which the women remained grateful.Footnote 53 Some loved and were loved by their husbands.Footnote 54 Some women in unhappy marriages before the war may have found life with their new families an improvement, and abduction to have bettered their lots as wives.Footnote 55

Children were even less willing to return, and many younger returnees escaped back. By the time of their rescue they had spent an average of four to five years in their new households or institutions, and many knew no other life. Especially in cases where a child was happily integrated into a household, vorpahavak felt more like abduction than redemption. There were also cases where children were simply too afraid to admit their Armenianness.Footnote 56

The Patriarchate's and the Ottoman government's policies of handling the reluctant abductee differed. In general, Armenians of all strands agreed that all Armenian children, regardless of their wishes or whether or not they claimed to be faithful Muslims, had to be returned to the nation's bosom. Ottoman regulations supported this policy by ordering that all former Armenians below age twenty, irrespective of their inclinations, be presumed to have converted to Islam by force—thus their conversions were annulled automatically.Footnote 57

Where the two centers of authority diverged was on the question of how to deal with people older than twenty. The Ottoman government decreed that such individuals had the right to choose what was best for themselves. The main problem here was married women—the 28 November 1918 order to the provinces maintained “the constitution commands freedom of conscience” and that married women over twenty be free to re-Armenianize, in which case both their conversion to Islam and their Muslim marriages would be annulled. If they wished to return to their original religion but not divorce their Muslim husbands, they had to apply to the courts.Footnote 58 Married women under twenty, even though their conversions to Islam were considered invalid, would not be forced to re-Armenianize and divorce; their cases, the government said, would be resolved in court, in the presence of members of their natal family (if they had any), church authorities, Christian missionaries (or other Westerners), and Ottoman officials.Footnote 59

The Patriarchate took a different stance, and insisted that irrespective of their age, choice, marital status, or self-identification, every former Armenian had to be reclaimed, and if they insisted on escaping, they would be imprisoned.Footnote 60 It is important to note that not every Armenian who took part in the vorpahavak initiatives agreed with this position. Some—including Avedis Aharonian, a member of the Armenian Republic's Parliament and the co-chair of the Armenian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference—thought those women who lived with “relatively bearable Muslims,” had children, and were accustomed to their way of life should be left where they were. Aharonian did not believe that women who were fine in the Muslim homes would be able to successfully reintegrate among Armenians. He emphasized that Armenians should spare no effort to rescue each and every Armenian girl and woman who was suffering at the hands of “savage races” (vayrak tsegh), then cautioned that if a woman chose the new Muslim family, to aggressively seize her against her husband's wishes would agitate such “savage races,” who were Armenia's future neighbors with whom the survivors had to live.

For others, like Zaruhi Bahri, considerations of individual happiness occasionally demanded a respect for personal wishes. She was a colleague of Zaruhi Kalemkiarian, the recorder of X's story in this paper's opening vignette. Like Kalemkiarian, she was a native Constantinopolitan from an elite intellectual background. During the Armistice era she remained very active by directing an orphanage/shelter, penning articles in periodicals, and working for the Armenian Red Cross, which she had helped found in Istanbul. The Patriarch personally asked her for assistance in directing a Neutral House orphanage/shelter across from her house in Şişli where women and children of contested identities were sheltered until their true identities were determined.

In her memoirs, Bahri took a cautiously critical tone when detailing how the Patriarch himself never sympathized with liberated women who wanted to go back to the homes they had been abducted to. Bahri herself was clearly a tough inspector, who more than once brought out the Armenianness of children and women who veraciously and for days denied their origins, but in at least two cases she begged the Patriarch to let captives go. In the first case, the Patriarch suspected that Bahri might help the escape of a certain Aghavni Kazazian (who had already tried to run away twice) and so ordered Aghavni declared mentally ill and institutionalized in the Armenian National Hospital. This even though Aghavni showed no signs of an illness except for longing for her husband and her son, whom Bahri defined as “a Turk, yes, but of her own blood and ultimately her very own child.”Footnote 61 In the second case, a young Armenian woman was happily married to an Iranian who had saved her during the deportations. Though National Assembly officials forbade this woman returning to her husband, as Bahri bitterly noted, at about the same time her husband's equally Iranian brother was in the process of marrying an Armenian girl in Istanbul, freely and with the full consent of both parties.Footnote 62 The Patriarch's memoir includes detailed passages on the Neutral House but is silent on the topic of orphans and women who preferred to stay among Muslims.

Turkish officials and the broader public were disturbed by news of such cases as well as by the many complaints that vorpahavaks were retrieving true Muslims, both mistakenly and intentionally. As women and children were transferred from one group to another, they found themselves caught up in fierce debates over who had kidnapped whom.Footnote 63 Turks accused Armenians of being baby snatchers “who hoped to replenish their wartime losses from the Muslim pool.”Footnote 64 Government-led Turkish newspapers claimed that Armenians were beating and threatening Muslim children to make them “admit” their Armenian origin.Footnote 65 Armenian editors responded by accusing the Turkish press of maintaining the genocidal mentality by blaming victims for the perpetrators' crimes. One Armenian editor ended his piece about the issue with: “It would be naïve to talk about colors with a blind person, about sounds with a deaf person, and of conscience with a perpetrator [of massacres].”Footnote 66

In the Ottoman lands, political competition over the redefinition of children's true belonging has a history reaching back to the late nineteenth century. Notwithstanding that children are allocated powerful symbolic roles by collectivities that imagine themselves as nations, the late-Ottoman battle over “nobody's children” expressed also the demographic concerns of a crumbling empire. These concerns, combined with the changing urban fabric of a fast-modernizing Istanbul, led to a competition over foundlings and abandoned children, between the state, non-Muslim civil and religious leaders, and missionaries.Footnote 67 While the central state and the municipality wanted to assume all foundlings' Muslimness, non-Muslim leaders argued that at least those who were left in front of churches and synagogues should be taken in by the respective communities. Greek and Armenian patriarchates were alarmed at Catholic missionaries' active roles in foundling care, because the missionaries, who were forbidden to convert Muslims, continued to take in Christian children and convert them to Catholicism.

In immediate postwar Istanbul, the fights between opposing parties escalated to the degree that when the British occupying forces intervened, “Neutral Houses” were opened to determine which children or women belonged to which group. In Istanbul, the Neutral House (Chezok Dun in Armenian, Bitarafhane in Turkish) was established in Şişli, close to the Armenian Red Cross's special maternity ward that I described earlier in this paper. It was managed by a joint committee composed of one Turk, one Armenian, and one American female director. There, children and young women who claimed Muslim identity but were suspected of hiding their Armenian identity out of fear of Muslim retaliation, or simply due to brainwashing, were isolated from their Muslim families. After a few weeks' stay at the house, surrounded by Armenians, most admitted they were Armenian.Footnote 68 During this process, the Turkish director resigned in protest, claiming that Turkish Muslim children were being Armenianized.

Available evidence indicates that the vorpahavak initiative did not employ a conscious, widespread Armenianization policy, and some mistakes were corrected by returning children or women to their families.Footnote 69 They were corrected not only to straighten out the record, but also because Armenian authorities were wary of what they believed were Turkish plans to present Armenians to the occupation forces and the League of Nations as kidnappers of Turkish children. In a March 1922 internal report, Arakel Chakerian cautioned the Patriarch that if Turks found even one Turkish child in an Armenian orphanage they would make a serious issue of it. He strongly advised letting go from Armenian orphanages the few children who still insisted that they were Turks. We do not know if this was done.Footnote 70

Even though Armenianization was not the general policy, vorphavak agents' criteria for considering someone Armenian were very broad: if a suspect did not protest otherwise, and if no other party claimed them, they were considered Armenian whether or not they remembered their previous language, family, or location. Zaruhi Bahri narrated how a certain Zekiye, a Turkish woman who had introduced herself as an Armenian, was easily sheltered in Armenian orphanages despite the facts that she neither knew Armenian nor “looked like an Armenian.”Footnote 71 Aghavni Kazazian's Muslim husband had hired Zekiye to enter the shelter and convince his wife to return to him.

In addition to always erring on the side of the potential Armenianness of any orphan, authorities at times forced confessions (true or possibly false), and did occasionally Armenianize Muslim children, or ignored when others did.Footnote 72 Aram Haygaz, a teenager at the Yesayan orphanage at the time, in his memoirs told of a ten-year-old boy who, unlike many others like him, would not admit his Armenianness, and even after some time at the orphanage, and suffering threats and pressure, continued to insist that he was Turkish. Ultimately, Haygaz and his friends believed him, but they decided that “even if he was a pure-bred (zdariun) Turk, we would keep him to Armenianize him gradually (asdijanapar hayatsnenk).”Footnote 73

Haygaz's explanation of why they kept this boy, who they knew had a Turkish mother and father outside the orphanage walls, leads us to ask why this rescue effort was at times so aggressive, passionate, and determined. One of the orphans who worked on this “case” with Haygaz maintained, “They Turkified thousands from among us. Now it is our turn to at least Armenianize one among them.”Footnote 74 Haygaz, the sole survivor in his family, who had spent the war years in Ottoman Kurdistan where he was converted and adopted by Muslim families, noted that the issue here was one of reprisal (pokhvrezh). Revenge was definitely part of the story, but only one part. To understand the whole we must understand the contemporary international political framework and the fight over territory that was ongoing.

RECLAIMING PEOPLE, RECLAIMING LAND

The fight at this time over women and children epitomized the larger, ongoing conflict between Armenians and Turks. It centered on a piece of land, today within eastern Turkey, that Ottomans referred to as their “Eastern Provinces” and Armenians as “Western Armenia.” As with the minors and women, each side claimed and reclaimed the land as its own and fought for it militarily, or diplomatically, or both.

Around the same time that the story of X was unfolding in Istanbul, the great powers gathered at Versailles to redraw the world map. Armenians sent a well-equipped delegation to the Paris Peace Conference to lobby for their entitlement to a share of the soon-to-be-dismembered Ottoman Empire. The goal was to expand the tiny Republic of Armenia in Transcaucasia (established in May 1918) to include the western parts of the Armenian historical homeland that had been under Ottoman rule since the sixteenth century. The establishment of Greater Armenia or United Armenia would not only realize Armenians' “age-old dream,” but would also gain revenge against “the Turk” who had recently attempted to exterminate the whole Armenian nation.Footnote 75

Yet, having just survived this annihilation campaign, Armenians lacked the numbers needed to people the land, a particularly harsh challenge in the immediate postwar era. The Paris Peace Settlement negotiations, with their emphasis on Wilsonian “self-determination,” came to an agreement that the nationality of a region was to devolve to that community that made up the majority of the population.Footnote 76 Armenians had to come up with numbers, and quickly.

Patriarch Zaven learned about the intricacies of international diplomacy first-hand during his European tour in support of the Armenian Delegation. In London, the commission charged with Armenia's future borders told him, “The more people you have the more land you will get.”Footnote 77 British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon's assistant also advised the Patriarch to “hearten the dispersed Armenians to immediately return and populate Armenia.”Footnote 78

Both the Armenians and the leaders of the Kemalist movement anticipated the unleashing of a “war of statistics.”Footnote 79 One of the most important tasks of the emerging defense committees was to prove, by “scientific means,” that Muslims had always constituted the majority in the regions that Armenians claimed to be their historical homelands, places that the Armenian delegation in Paris attempted to prove, also statistically, had to belong to Armenians.

Armenian populations away from Paris were clearly aware of the link between numbers and territory. In December 1919, the editor of Hay Gin (Armenian women), the prominent Armenian women's journal of the time edited by Hayganush Mark (a colleague of Zaruhi Kalemkiarian and Zaruhi Bahri), wrote with alarm that Islamized Armenians had to return to their natal religion so that “we get our Armenia.”Footnote 80 In order to accumulate statistical proof and create the necessary demographic profile, Armenians launched a worldwide pro-natalist campaign, which was part of a broader campaign called “National Revival/Rebirth” (Azkayin Veradznunt).Footnote 81 Their goal was to raise the Armenian population, Armenian landholdings, and Armenian life generally, back to, or beyond, their prewar levels.

Predictably, this campaign placed women at the heart of the Armenian state-building project, both as real actors and as objects of discourse. To lower infant and juvenile mortality, columns in Armenian periodicals urged mothers to employ scientific childrearing practices. The pages of the press poured out detailed information on topics such as babies breastfeeding, getting enough fresh air, and wearing proper clothing. Women's journals organized “pretty baby” contests to encourage mothers, while journalists and professionals urged young women and men to marry early and produce many children.Footnote 82 Abortion became tantamount to treason. The medical journal Hay Puzhag (Armenian healer), which published regular reports on how many marriage certificates the Patriarchate had issued, characterized abortion-seeking women as “egoist and undutiful.” Equating abortion with infanticide, it addressed the Armenian woman: “Keep away all thoughts and principles of degeneration and devote yourself to your procreation, which is your sole duty. It is the complete fulfillment of this duty that will realize our ideal.”Footnote 83

The push to realize this “ideal” justified policies that would have been nearly unthinkable before the war. Most significantly, Armenian authorities—political and religious leaders as well as intellectuals and professionals—were willing to change the coordinates of legitimate belonging. Both the administrative practices toward and discourses about rescued pregnant women and their offspring reveal that, facing a perceived existential crisis, Armenian authorities changed the criteria for inclusion in the national collectivity by making room for one group that would otherwise have been excluded—babies of Muslim fatherhood.Footnote 84

In the summer of 1920, Dr. Yaghoubian, in charge of the Armenian Red Cross hospital where X was incarcerated, delivered a lecture at the center of the Armenian Women's Association. The doctor argued that depopulation was the “worst enemy of a nation's development” and therefore had to be fought with every medical, social, and material effort. After emphasizing mothers' unique role in realizing this national goal, he encouraged non-refugee women and girls to become nurses and midwives so that they could prevent abortion and infanticide among refugees, especially rescued women and girls. He stated:

We respect the offspring of lawful marriages and curse free love. The Armenian baby has to be parented by those who have been lawfully married in the Armenian Church. But we cannot dismiss some unfortunate realities of life; many of our deported sisters and wives became mothers by force, with the fear of the knife or death; many in half-dead state have become victims of savage races' pleasures. […] A smart midwife knows how to support and console such poor women and will try to conceal [dzadzgel] their shame; more importantly, she will hinder them from aborting their unlawful baby. Big governments build special shelter houses for such unlucky people and they protect the children born out of wedlock [aboren] with special laws. We, however, as the tiniest of small nations, how can we exterminate our fetuses, even though they may be out of wedlock?Footnote 85

That Yaghoubian considered products of rape to be “our fetuses” is telling, especially since it follows his statement that the fathers of these babies belonged to a “barbarian race.” Given that Muslim and Christian traditions as well as law asserted that progeny was made up primarily of a fathers' substance and thus belonged to him, Yaghoubian's statement, like many vorpahavak practices, stood in stark contrast to established practice. Women were now seen to have a creative and not just a receptive role in procreation; they were assumed to have engendered, not simply contributed to, their progeny.

This response to rape babies of mixed heritage has by no means been the universal one in similar cases. For instance, in Bangladesh during the 1971 War of Independence, Pakistani army personnel raped about two hundred thousand women. In the war's aftermath, the Bangladeshi state elevated the rape victims to the status of “war heroines,” but excluded their children by categorizing them as Pakistani. It was decided that the presence of these babies would adversely affect the country's social structures and perpetuate painful memories of the war, and abortion and foreign adoption, once criminal and unaccepted, were made legal.Footnote 86 In contrast to the Armenian case, where women were not allowed to abort their rape babies, Pakistani women were “de-kinned” from their offspring by coerced abortions or forced surrender of their babies for adoption.

What is perhaps most unique about the Armenian case is the lack of discussion of, let alone opposition to the changed paternity rules. A contrasting case is that of the enfants du barbare, children of French women raped by Germans during World War I. There were fierce debates in France over how to handle their situation, what to do with the babies, where they belonged, and to whom, and so forth. Some people, including even Catholic priests, advocated abortion in the name of racial purity. Others remained anti-abortionists, and argued that women's contribution to procreation was greater than men's, that in any case French “civilization” in a child would triumph over its German barbarism, and that France needed nationals.Footnote 87

The lack of Armenian opposition to the Patriarchate's policies might be explained by the felt immanency of the realization of the “national ideal.”Footnote 88 Perhaps the vision to establish Mayr Hayasdan (Mother Armenia) justified these extraordinary measures. Moreover, the genocidal nature of the conflict might have influenced both the policy and the absence of discussions. We know, for another comparative instance, that after the Rwandan genocide the state forbade the international adoption of rape babies. Rwanda needed citizens, yes, but it did not go so far as to ban abortions. In fact, the former ban on abortions was temporarily relaxed so rape victims could obtain them. The Armenian administration's attitude regarding abortion, then, stands in contrast to comparable cases.

That said, the alarmist tone of the above quotation from Dr. Yaghoubian reveals that not all refugees shared “the national agenda.” Many of those on whom motherhood was forced simply did not want to have the babies, which, again, is a common response among genocidal rape survivors. Among the Bosnian Muslim and Rwandan Tutsi women, scholars documented soaring rates of self-induced abortion, infanticide, neglect, and child abandonment.Footnote 89 For Armenians, the rare anecdotal evidence comes from the writings of Constantinopolitan women, both Armenian and American, who worked with the rescued. They recount how some rescued pregnant women, like X, were relieved when their newborns died (and may have neglected them intentionally),Footnote 90 and that some explicitly asked orphanages to take their Muslim children from them so that they would not kill them as a rapist's offspring.Footnote 91 One, after being told that she was at an early stage of pregnancy, responded to her American doctor simply, “Very well, I will send it to its father.”Footnote 92

Under vorpahavak policy, authorities would not allow the baby to be sent to the father; it would be sheltered in an orphanage and baptized by the church.Footnote 93 Clearly, the “half-caste” progeny represented radically different things for their mothers, for their surviving maternal relatives, and for Armenian leaders. The Turkish state and public seem to have overlooked the issue, focused as they were on the threat of losing fully Muslim orphans, and integrated women, to the enemy.

Available evidence indicates a general pattern of surviving Armenian relatives being eager to get back their kidnapped women and children, whether or not they had been raped, or wanted to return, or had given birth to “wrong children.” Indeed, they insisted on their return. But relatives sometimes did not want to bring “the enemy's children” into their midst. One survivor in an interview recalled a woman who had been abducted at age twelve, was married to a Turk, and had two children by him. After the genocide, her father found out where she was and wrote to her to say that he wanted her to rejoin him, but did not want her children, “who belonged to a Turk.” “She kept crying and crying, not knowing what to do. Finally she decided to leave and went to Beirut; once in Beirut, she could not take it without her children but was too afraid to return.… She was miserable.”Footnote 94

Some mothers chose, and managed, to escape with their children. One of these women lived in the same refugee camp as Kerop Bedoukian, who was then a young boy. In his memoirs Bedoukian recalled that this twenty-two-year-old's one-year-old son not only made impossible her marriage to an Armenian but “also branded her as a whore.” This did not prevent the woman's skillful mother from marrying her to a handsome Armenian man from America, who had arrived in Istanbul to find a wife. The American was first engaged to his future wife's sister, a pretty eighteen-year-old who the mother apparently used as bait. Bedoukian told the story of the family sleeping in the next blanket in the refugee camp: “Their mother arranged it that he should go to America with the older girl and the child, to help them get settled or possibly find her a husband, before he sent for his own bride. Three months later, the bride-to-be flew into a great rage on receiving the news that her fiancé had married her sister. The mother tried to explain that it was easy to find her a husband, but for her sister it was another matter. If she loved her sister, she should be glad. Well! She did not love her sister and she did not mind telling the world about it!”Footnote 95

For many rescued women and refugees, a proper marriage represented the most viable way to exchange the transient life for some sense of stability and security.Footnote 96 Here the goals of the rescued and their rescuers converged. For the vorpahavak agenda, marrying younger women and girls to Armenian men and placing their children with Armenian families as foster children or adoptees represented an ideal solution: they retrieved what the Turks had stolen, and employed them to reproduce Armenianness.

Given the pre-genocide ideas about purity and propriety, Armenian leaders had their work cut out for them in packaging rescued women as proper marriage candidates and future mothers. As early as 1916, Hairenik (Fatherland), a daily of Boston, announced, “An Armenian man should not reject a woman who has been abducted since she is an innocent victim who cannot be held morally responsible for her condition.”Footnote 97 A contributor to Hay Gin warned that victims should not be blamed for the actions of “bestial packs of wolves that deflowered and mutilated Armenian virgins.”Footnote 98

As norms regarding paternal lineage were suspended, so too did ideas about proper marriageability change, at least temporarily. But unlike the new lineage norms, changing conceptions of marriageability seem to have been shared by the mass of the people, and for good reason. Men in the diaspora, at least, were eager to marry rescued women. In 1919, out of the seventy women sheltered in the Scutari Women's Shelter for the Rescued, twenty-one married within their first year there.Footnote 99 Most went to America, many as picture brides. Many of the grooms had settled in North America before the war, and had lost their families in the Ottoman lands during the war. A survivor observed that men “returned from America for the sole purpose of marrying orphans and widows to help heal and make them forget their tragic past, to give them a new home, and to create new hope—this was the least they thought they could do for those who had survived.”Footnote 100 Even the tattoos that many of the rescued bore on their faces and hands (an Arab and Kurdish tradition) did not necessarily leave them unmarriageable.Footnote 101 Understandably, many of these women hated their tattoos, and some disfigured themselves trying to burn them away with acid.Footnote 102

There were various reasons that men living abroad, many of them disempowered laborers, might want to marry rescued orphans, including a desire to partner with someone in their daily struggles, and for someone to help them overcome the loss of their families. At the same time it was a way to re-masculinize. This was true for those men who rescued women, ordered their rescue, or fathered them, married them, or married them off. Armenian men who were made to witness violations of their families, or were away when they were violated, now had a chance to do what they felt they should have been doing before: protecting their women and minors. While saving them, either literally or by marrying them despite their defiled state, they also saved themselves from feelings of guilt and emasculation. In addition to the chance to regain people and land, vorpahavak offered a chance to reclaim manhood.

The relevant discourse did not employ an explicit language of masculinity but rather a vocabulary of protection (der ganknil in Armenian, sahip çıkmak in Turkish), benevolence, honor, and revenge.Footnote 103 For instance, when in 1921 the Armenian Church in Baghdad received hundreds of recently reclaimed children, among them many girls tattooed according to Bedouin traditions, the priest collectively baptized them “Vrezh” (Vengeance).Footnote 104 The Patriarch himself, suiting his function as parens patriae, took the guardianship of his unprotected flock quite seriously.Footnote 105 All the rescued, even the prostitutes that he had saved in Mosul where he had been exiled, were the nation's “unfortunate sisters” (darapakhd kuyrer), and crucially, they still represented the honor of the nation, the precious Armenian national honor that men had to protect by marrying them.Footnote 106

The first such wedding in Istanbul was narrated by Anayis (Yeprime Avedisian), another prominent native Armenian woman of Constantinople, an activist and writer, and a colleague of Kalemkiarian, Bahri, and Hayganush Mark. The wedding celebration took place nowhere other than in the Neutral House, and the Patriarch presided over the church ceremony, which Anayis described:

Only rarely has a wedding ceremony been this serious and impressive. When the priest, amidst the smell of incense, was blessing the young groom and the bride in white, we felt as if we recognized the smells of martyrs' souls, who (forgetting their tortures, the suffering of exile, the blood-filled lakes that they had seen, and the whip of the merciless Turkish sergeant) came, with the company of little angels, to witness the wedding of a sweet budding flower who was going to sprout on top of embellished mountains and give beautiful flowers so that the nation/race [tsegh] continues invincibly.Footnote 107

The passage is striking from a number of perspectives. The bride wore the color of purity despite having been rescued from a Muslim household where she probably served as a wife or concubine. Her dressing in white negated her previous experiences, thus denying, both literally and figuratively, the rapist or perpetrator the right to violate an Armenian girl's virginity, and by extension, to dishonor what she represented: the honor of her male relatives and her nation. This was also a retaliation ceremony which the martyred dead would have watched with satisfaction: the wedding of two Armenians, including one who could have been lost to Turks forever, meant that Armenianness would continue despite the Turks. That this sweet budding flower was going to sprout atop “embellished mountains” takes us directly to the issue of land. Given that the ultimate territorial symbol of the Armenian historical homeland had long been Mount Ararat, the reference to mountains connected the reclamation of land to the reclamation of people, the two sides of the overall Armenian project.

CONCLUSION

Subsequent historical developments soon revealed that this Armenian project had failed: no Greater United Armenia was ever established, and the independent republic in the Caucasus lasted only twenty months until its Sovietization in December of 1920. The 1923 Lausanne Treaty not only did not grant Armenians any territory, but it declared a general amnesty for war crimes, effectively pardoning the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide. Turkey, including the Ottoman Six Provinces, was declared a republic that October, ending the rule of the six hundred-year-old Ottoman Empire.

The vorpahavak ended in the autumn of 1922, when the first Turkish officers victoriously entered Istanbul and the Allied evacuation began. Many people associated with the vorpahavak, including the Patriarch, Zaruhi Bahri, Anayis, Arakel Chakerian, and others who had worked in collaboration with the occupation forces, fled the country in panic or were expelled.Footnote 108 The League of Nations' rescue effort ended in Istanbul in 1926 and in Aleppo in 1927. Thousands of Armenian women and children who continued to live in Muslim households or orphanages, by their choice or against it, lived and died as Turkish citizens of Muslim religion.Footnote 109 Some found ways to resume relationships with their former Armenian relatives, exchanging letters, money, or even visits.Footnote 110 Their stories remained mostly silent and silenced in Turkey until recently, when their memories began to resurface via their grandchildren.Footnote 111 For Armenians, orphans and orphanhood have remained central both to a defining national discourse and as a focus of humanitarian and charitable giving. By contrast, the attention given to the rescued girls and women slowly receded.

This article has remembered them as policy objects of a post-genocide nation that badly needed to people a promised land. Females were incredibly valuable assets both during the war, for the perpetrator group, and afterwards for survivors, because of not only what women possessed but also what they lacked. Wombs reproduced the group physically while their holders reproduced it socially. However, what rendered women golden for opposing nationalists with similar goals was the perceived female deficiency for naming: while performing these vital functions for each group's present and future, women could define neither the group nor their progeny. The same nationalist ideology that portrayed women as the national core, the nation's essence and critical difference, remained patriarchal at all times, denying women any creative potential. Perceived genetic ineffectiveness, then, needs to be added to the list of reasons why women may matter to national, ethnic, and state projects.

Herein lies the central problematique of this essay, why a patriarchal structure like that of the Armenian community in Istanbul, led literally by a Patriarch, reversed these assumptions in order to make space for those who would have otherwise been left out. Like many other states or state-like structures facing real or imagined existential crises, Armenians passed emergency laws and crafted new technologies with gendered implications. The temporary change in Armenian descent rules led to many children of Muslim fatherhood growing up Armenian. While some “hidden Armenian” grandparents in contemporary Turkey have become publicly visible, we have yet to learn the story of X's baby boy, who, if he survived without breast milk, would have continued life as Armenian.Footnote 112