Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and tic disorder (TD) represent highly disabling, chronic and often comorbid psychiatric conditions.Reference Dell’Osso, Benatti and Hollander 1 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) introduced the “tic-related” specifier for OCD, highlighting the tendency of patients with obsessive-compulsive tic-related disorder (OCTD) to show different clinical characteristics (eg, symptoms, comorbidity, course, and familial transmission) compared to OCD alone. 2 , Reference Zohar 3 Available literature identified several distinctive features for OCTD, such as early onset, prevalent male gender, sensory phenomena, specific obsessions (eg, symmetry, aggressiveness, hoarding, and exactness), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) comorbidity, and positive family history for OCD and/or TD. 4-6 A previous study from our group on socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with OCTD reported several unfavorable socio-demographic and clinical characteristics compared to patients with OCD without a history of tic, including higher rates of suicidal behaviors in patients with OCTD compared to patients with OCD.Reference Dell’Osso, Benatti and Hollander 1 A recent consensus article identified the need of further studies to better characterize OCTD with a particular focus on clinical aspects, such as epidemiology, etiology, course of illness, overall burden and disability, treatment response, and suicide risk.Reference Dell’Osso, Marazziti and Albert 7

Historically, focusing on suicidal behaviors, OCD has been considered to show an overall low suicide risk, which was mainly attributed to comorbidities, such as mood disorders.Reference Amerio, Stubbs, Odone, Tonna, Marchesi and Ghaemi 8 Recent studies, however, highlighted how OCD per se is associated with increased levels of suicidality compared with the general population,Reference Angelakis, Gooding, Tarrier and Panagioti 9 , Reference Angelakis and Gooding 10 even without other psychiatric comorbidities.Reference Fernández de la Cruz, Rydell and Runeson 11 A previous meta-analysis by Angelakis and coworkers and a recent review by Albert and colleagues estimated a median rate of suicidal ideation ranging from 26.3% to 73.5% and a median rate of suicide attempts from 10.3% to 14.2% for patients suffering from OCD.Reference Angelakis, Gooding, Tarrier and Panagioti 9 , Reference Albert, De Ronchi, Maina and Pompili 12 Several studies found an association between a higher suicide risk in patients with OCD and specific clinical factors, including: previous history of suicide attempts, suicide attempts in a family member, tobacco smoking, hopelessness, specific obsessions and compulsions (eg, aggressive, symmetry/ordering, sexual/religious obsessions, and obsessions subjectively considered as unacceptable), substance use disorder, childhood trauma, alexithymia and psychiatric comorbidities.Reference Angelakis, Gooding, Tarrier and Panagioti 9 , Reference Albert, De Ronchi, Maina and Pompili 12 , Reference Velloso, Piccinato and Ferrão 14 , Reference Kamath, Reddy and Kandavel 13Among comorbidities, depression has been largely investigated in patients with OCD and several studies suggested an association between higher suicidality and mood disorders or, more in general, higher depressive/anxiety symptoms.Reference Angelakis, Gooding, Tarrier and Panagioti 9 , Reference Velloso, Piccinato and Ferrão 14 , Reference Narayanaswamy, Viswanath, Veshnal Cherian, Bada Math, Kandavel and Janardhan Reddy 15 Suicidality has been poorly and only recently explored in TD. Indeed, patients with TD often present clinical features related to a well-established suicide risk, such as social isolation, bullying, rejection, and psychiatric comorbidities, particularly ADHD, OCD, and depression.Reference Fernández de la Cruz, Rydell and Runeson 11

In light of the above, the present multicenter study aimed to investigate and compare clinical and sociodemographic features in a sample of OCTD vs OCD subjects with no history of tic, with a specific focus on suicidal ideation and attempts, hypothesizing that patients with OCTD might exhibit a different profile in this respect compared to patients with OCD.

Methods

Patients with a DSM-5 diagnosis of OCD with and without comorbid TD of either gender or any age were recruited from nine different psychiatric departments across Italy. Diagnoses were assessed by means of a semi-structured interview based on DSM-5 (SCID-I and II).Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams 16 , Reference First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams and Benjamin 17 Additional protocol details have been fully described elsewhere.Reference Dell’Osso, Benatti and Hollander 1 In brief, patients recruited in different psychiatric departments were assessed using a novel questionnaire, under validation, developed to better characterize OCTD and composed of 35 questions assessing the following areas: (a) prevalence of OCTD; (b) patient’s main socio-demographic features (ie, age, gender, occupation, level of education, and marital status); (c) clinical history (ie, age at OCD onset and TD onset, presence of other psychiatric comorbidities and age at comorbidities’ onset, psychiatric family history including affective disorders, anxiety disorders, OCD and related disorders, TS/TD, psychotic disorders, neurodevelopment disorders, personality disorders, and psychiatric polycomorbidities), OCD duration of untreated illness (DUI); and (d) perceived quality of life, course of illness, current psychotherapy and psychopharmacological therapies, treatment response (defined as a decrease of at least 35% of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale—Y-BOCS—total scoreReference Goodman, Price and Rasmussen 18) and treatment resistance, presence of past/current suicidal ideation (SI), or suicidal attempts (SA).

In order to compare clinical and demographic features of patients with OCD and OCTD with and without suicidal behavior, after a preliminary analysis of these features on the whole sample, we further divided it in patients with OCD with and without past SA and patients with OCTD with and without SA. SI and previous SA were assessed with two detailed open questions respectively on patients’ previous and actual suicidal ideation and previous attempts of suicide.

The whole sample and related subgroups were analyzed using Pearson Chi-squared test for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SPSS 24 for Windows software (Chicago, IL) with the level of statistical significance set at 0.05.

Results

Three hundred and thirteen patients were enrolled in the study, distributed as follows: 50 (13.7%) from Policlinico Hospital and Ospedale Universitario Luigi Sacco, Milan; 43 (16%) from Galeazzi Hospital, Milan; 16 (5.1%) from San Paolo Hospital, Milan; 60 (19.2%) from Istituto di Psicopatologia, Rome; 63 (20.1%) from Rita Levi Montalcini Department of Neuroscience, Turin and the Department of Biomedical Sciences of Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna; 24 (7.7%) from Institute of Neuroscience, Florence; 19 (6.1%) from the Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine of Pisa and 38 (12.1%) from Teramo Hospital.

The sample consisted of 156 patients with OCTD and 157 patients with pure OCD. With regard to suicidal behavior, no differences between the OCTD and OCD group were found in terms of SI (OCTD 23.7% vs OCD 25.4%) while SA rates were found to be significantly higher in patients with OCTD compared to patients with pure OCD (OCTD 16% vs OCD 13.3%; P < .05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive tic-related disorder subgroups. *P < .05.

The two groups were then divided into four subgroups on the basis of presence or absence of SA: OCD with SA (OCD-SA), OCD without SA (OCD-noSA), OCTD with SA (OCTD-SA), and OCTD without SA (OCTD-noSA). Main socio-demographic and clinical features of the total sample and related subgroups are reported in Tables 1 and 2.

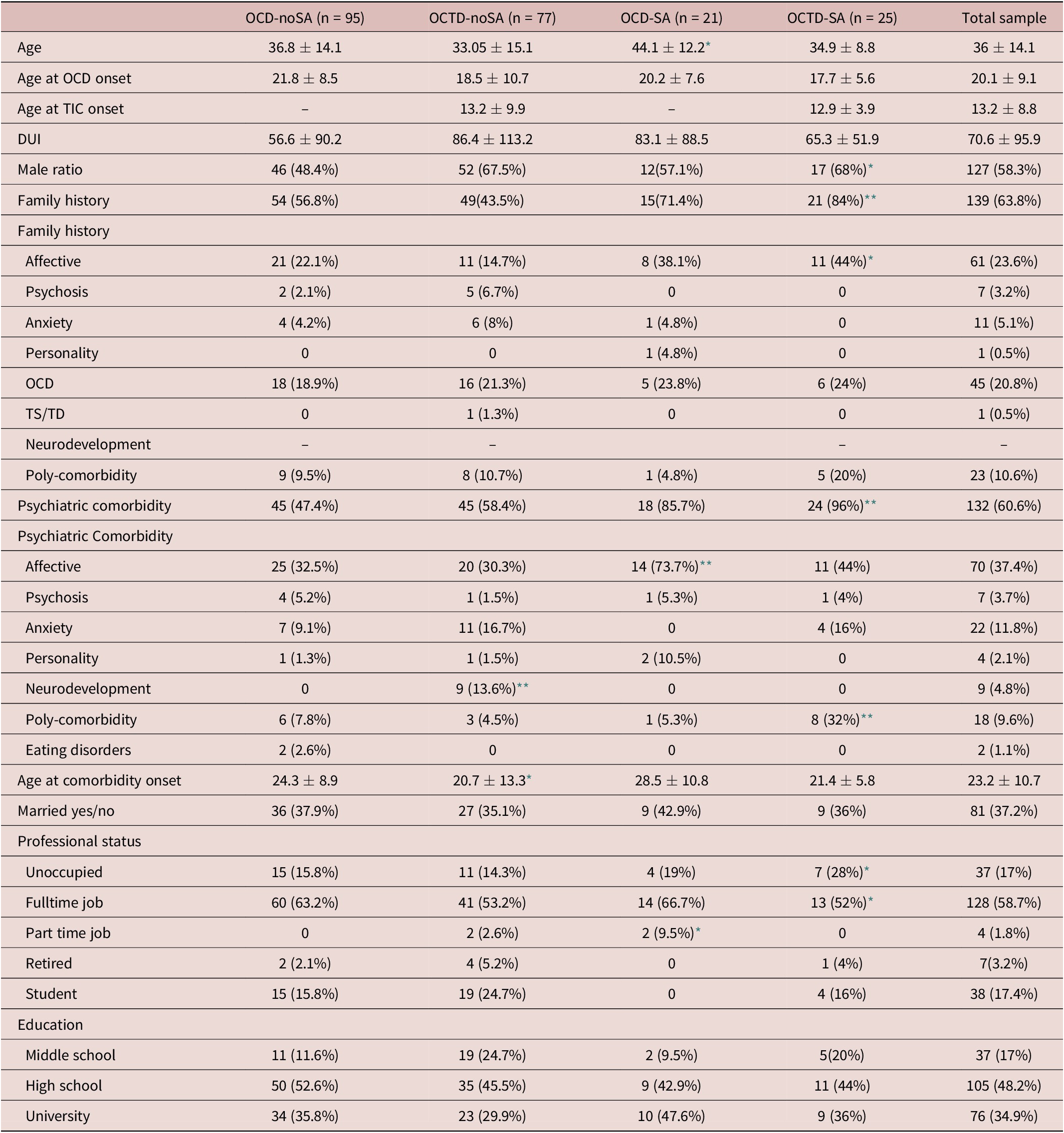

Table 1. Socio-Demographical and Clinical Data of the Sample.

Values for categorical and continuous variables are expressed as N (%) and mean ± SD, respectively. Reported variables had a percentage of missing data ranging from 0% to 15%.

Abbreviations: DUI, duration of untreated illness; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OCD-noSA, OCD without suicide attempts; OCD-SA, OCD with suicide attempts; OCTD-noSA, OCTD without suicide attempts; OCTD-SA, OCTD with suicide attempts; TD, tic disorder; TS, tic symptoms.

* P < .05.

** P < .001.

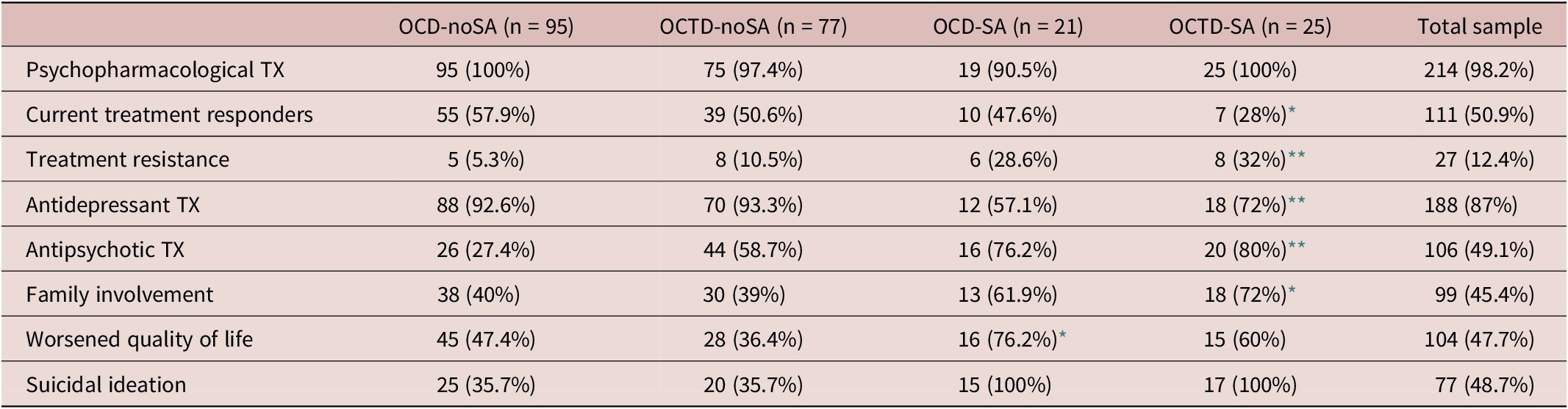

Table 2. Treatment-Related Features of the Sample.

Values for categorical and continuous variables are expressed as N (%) and mean ± SD, respectively. Reported variables had a percentage of missing data ranging from 0% to 15%.

Abbreviations: OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OCD-noSA, OCD without suicide attempts; OCD-SA, OCD with suicide attempts; OCTD-noSA, OCTD without suicide attempts; OCTD-SA, OCTD with suicide attempts; TX, treatment.

* P < .05.

** P < .001.

As concerns socio-demographic features, the OCTD-SA group was characterized by a significant male prevalence compared to OCD-SA and OCD-noSA groups (respectively: 68% vs 57.1% vs 48.4%; P < .05). In addition, the OCTD-SA and OCTD-noSA mean ages were significantly lower compared to the OCD-SA sample (respectively: 34.9 ± 8.8, 33.05 ± 15.07 vs 44.1 ± 12.2 years; P < .05). No differences were found in terms of marriage rates and educational status, while the OCTD-SA sample showed significantly lower rates of full-time occupation when compared to patients with OCD-SA and to OCD-noSA (OCTD-SA: 52% vs OCD-SA: 66.7% vs OCD-noSA: 63.2% P < .05). Moreover, the OCTD-SA sample revealed significantly higher unemployment rates compared to patients with OCD-SA, OCTD-noSA, and OCD-noSA (OCTD-SA: 28% vs OCD-SA: 19% vs OCTD-noSA: 14.3% vs OCD-noSA: 15.8%; P < .05).

The age at OCD onset was lower in the OCTD-SA group compared to the other three groups, though not reaching statistical significance (OCTD-SA: 17.7 ± 5.6 years vs 21.6 ± 9.0 years, OCD-SA: 20.2 ± 7.6 years, OCTD-noSA 18.5 ± 10.7 years, OCD-noSA 21.8 ± 8.5 years; P = .07; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Age at obsessive-compulsive disorder onset and age at comorbidity onset across the sample. *P < .05.

With regard to psychiatric comorbidities, patients with OCTD-SA and OCTD-noSA showed an earlier age of comorbidities onset compared to the OCD-SA sample (21.5 ± 5.8 years vs 20.8 ± 13.3 years vs 28.5 ± 10.8 years; P < .05; Figure 2). Moreover, patients with OCTD-SA showed a higher rate of psychiatric comorbidities compared both to the OCD-SA group and to the OCTD-noSA and OCD-noSA groups (OCTD-SA: 96% vs OCD-SA: 85.7% vs OCTD-noSA: 58.4% vs OCD-noSA: 47.4%; P < .001). The most frequent comorbidities in patients with SA were represented by affective disorders (OCTD-SA 44% vs OCD-SA 73.7% vs OCTD-noSA 30.3% vs OCD-noSA 32.5%; P < .001) and poly-comorbidities (OCTD-SA 32% vs OCD-SA 5.3% vs OCTD-noSA 4.5% vs OCD-noSA 7.8%; P < .001), while neurodevelopmental disorders were present only in the OCTD-noSA group (13.6%, P < .001).

Positive psychiatric family history was significantly higher in the OCTD-SA group vs the OCD-SA group and compared to patients without SA (OCTD-SA 84% vs OCD-SA 71.4% vs OCTD-noSA 63.6% vs OCD-noSA 56.8%; P < .001). In particular, family history for affective disorders was significantly more represented in the OCTD-SA and OCD-SA groups compared to OCTD-noSA and OCD-noSA groups (OCTD-SA 44% vs OCD-SA 38.1% vs OCTD-noSA 14.7% vs OCD-noSA 22.1%; P < .05).

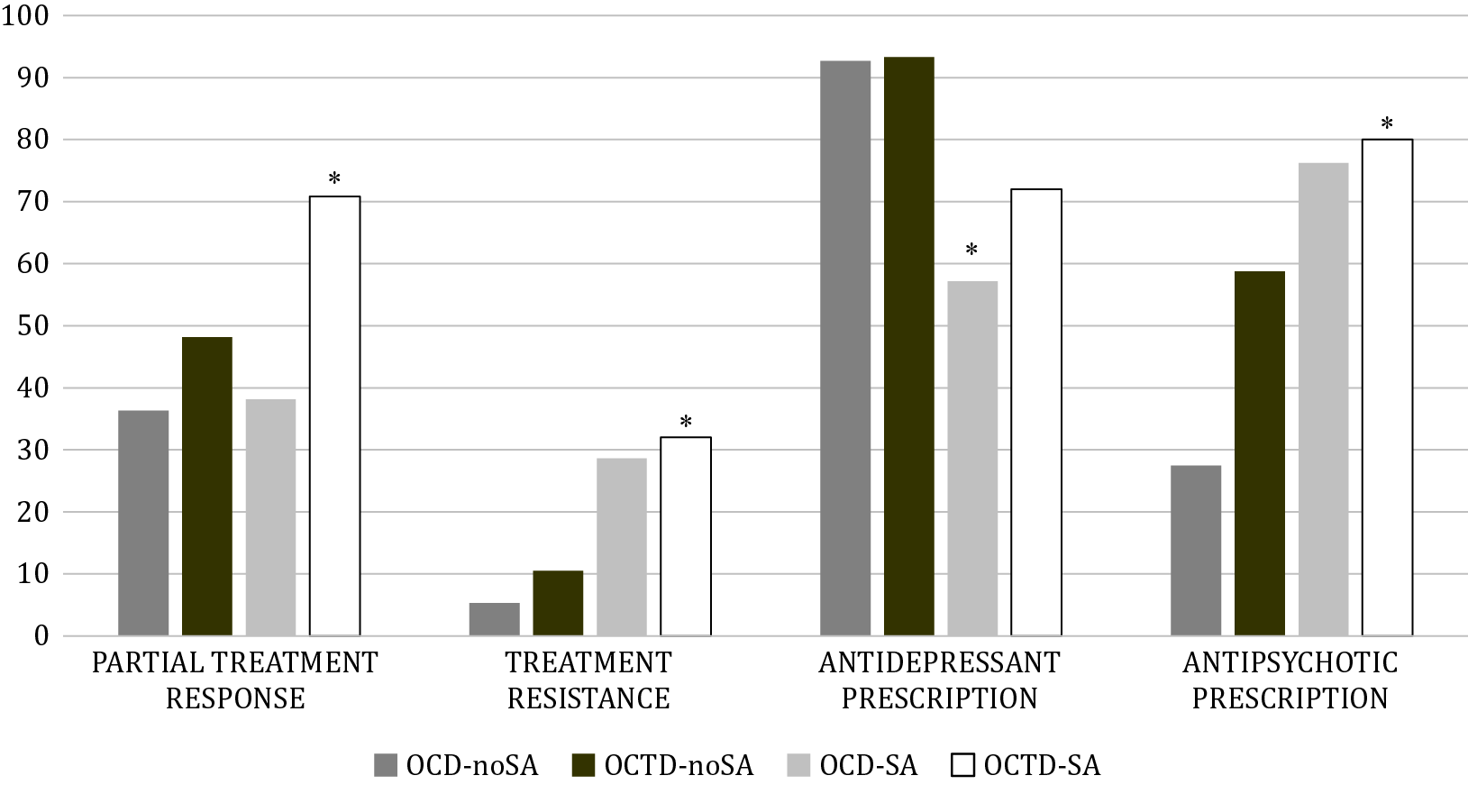

With respect to pharmacological treatment, patients with OCTD-SA compared to patients with OCD-SA showed a higher rate of antidepressant use (72% vs 57.1%; P < .001), while OCTD-SA and OCD-SA samples were treated with a higher rate of antipsychotics augmentation therapies compared to OCD-noSA and OCTD-noSA groups (OCTD-SA 80% vs OCD-SA 76.2% vs OCTD-noSA 58.7% vs OCD-noSA 27.4%; P < .001; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Treatment related variables of the sample. *P < .05.

Significantly lower treatment response rates were found in the OCTD-SA group compared to the OCD-SA, OCTD-noSA, and OCD-noSA groups (OCTD-SA 28% vs OCD-SA 47.6% vs OCTD-noSA 50.6% vs OCD-noSA 57.9%; P < .05; Figure 3) and treatment resistance was reported in a significantly higher portion of patients in the OCTD-SA and OCD-SA groups, compared to patients with OCTD-noSA and OCD-noSA (OCTD-SA 32% vs OCD-SA 28.6% vs OCTD-noSA 10.5% vs OCD-noSA 5.3%; P < .001; Figure 3).

Finally, rates of family involvement were significantly higher in the OCTD-SA group compared to the other groups (OCTD-SA 72% vs OCD-SA 61.9% vs OCTD-noSA 39% vs OCD-noSA 40%; P < .05), while perceived worsened quality of life rates were higher in OCD-SA group compared to OCTD-SA, OCTD-noSA, and OCD-noSA groups (OCTD-SA 66% vs OCD-SA 76.2% vs OCTD-noSA 36.4% vs OCD-noSA 47.4%; P < .05).

Discussion

This open-label, multicenter, cross sectional study on patients with OCD and OCTD showed different unfavorable epidemiological and clinical features in the OCTD sample. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating SI and SA in a multicenter sample of patients with OCTD vs OCD.

Compared to OCD, the OCTD subgroup revealed a higher rate of SA (OCTD: 16% vs OCD: 13.3%), but no differences in terms of SI (OCTD: 23.6% vs OCD: 25.4%). This result may be related to the latent impulsiveness characterizing subjects affected by OCTD.Reference Roessner, Becker, Banaschewski and Rothenberger 19 Patients with OCTD, in fact, often experience anger, frustration and externalizing behaviors that could emerge in a sudden and disruptive way and may end with SA.Reference Roessner, Becker, Banaschewski and Rothenberger 19 A previous study from our group on a sample of 266 patients with OCTD and OCD showed higher rates of SI and SA in patients with OCTD compared to patients with OCD.Reference Dell’Osso, Benatti and Hollander 1 The difference with present results may be due to the increased number of subjects recruited and to a further selection of the sample, given the tertiary care setting of the psychiatric centers performing the assessment.

After dividing the two subgroups on the basis of previous SA, several socio-demographic and clinical differences were observed.

In terms of gender differences, the OCTD-SA group was characterized by a significant male prevalence compared to OCD-SA and OCD-noSA sample. Limited studies have recently analyzed suicidality and its correlates not specifically in OCTD but, separately, in TD and OCD. Mixed results emerged in previous reports on suicidal behaviors in patients with TD. In 2015, Storch and colleagues did not find any gender differences between youth with chronic TD with and without suicidal behaviors,Reference Storch, Hanks and Mink 20 while in 2017, Fernández de la Cruz and colleagues found that female gender was associated with an increased risk of SA in a sample of 7736 cases of patients with tic symptoms (TS)/chronic TD selected from the Swedish National Patient Register, compared with control subjects.Reference Fernández de la Cruz, Rydell and Runeson 11 In 2017, the ICOCS group investigating clinical correlates of patients with OCD with a previous SA did not find any gender difference between patients with and without previous SA.Reference Dell’Osso, Benatti and Arici 21

Patients with OCTD-SA showed significantly lower rates of full-time occupation and higher unemployment rates when compared to individuals with OCD-SA and OCD-noSA. These findings are consistent with previous results on patients with OCTD, showing lower full-time employment ratesReference Dell’Osso, Benatti and Hollander 1 and, to authors’ knowledge, no previous study on SA in TD, TS or OCTD investigated this variable. However, previous studies focused on suicidal behavior in OCD found no significant differences in terms of employment status between patients with vs without SA or SI.Reference Alonso, Segalàs and Real 22 , Reference Balci and Sevincok 23

As previously mentioned, both OCD and OCTD can extensively affect patients’ and their caregiver’s quality of life. Thus, we investigated their family involvement, representing an important source of support in patients’ overall management and, in some cases, an essential help for their everyday life. In the present sample, the OCTD-SA group showed a significantly higher rate of family involvement compared to the other groups, revealing a higher need for caregivers’ support. This result could be partially explained by the younger mean age of the OCTD-SA group compared to the OCD-SA and noSA groups; however, mean ages of patients with OCTD-SA and OCTD-noSA did not show any difference, suggesting a greater need for family support in the OCTD-SA group independently from age and probably related to an overall higher clinical severity. To authors’ knowledge, no other studies investigated this aspect in the context of suicidal behavior in OCD/OCTD.

To further investigate the burden of patients with OCD and OCTD, we examined their perception of a globally worsened quality of life with an open question. In this case, the OCD-SA group showed the highest rate of perceived worsened quality of life, compared both to the groups of OCD-noSA and OCTD with and without SA. This finding could be related first to a globally worse clinical picture of OCD-SA group compared to the OCD-noSA group. Also, when comparing OCD-SA with the OCTD-groups, this result may depend on a better illness insight in patients with OCD compared to patients with OCTD, leading to a worse perception of the impact of OCD in the decline of quality of life. Moreover, in two previous studies, patients with OCD reported levels of quality of life that are lower than those exhibited by individuals with chronic and disabling conditions, such as schizophrenia.Reference Fontenelle, Fontenelle and Borges 24 , Reference Moritz 25 Eventually, the perception of a worsened quality of life in the OCD-SA group compared to the OCTD-groups could be linked to a higher OCD severity in the first group. However, in the present study OCD severity was not measured through specific psychopathological scales.

The analysis of the clinical features of the sample revealed an overall worse condition in patients with a history of SA.

First, the age at onset of OCD was found to be earlier in the OCTD-SA group compared to the other three groups, but this difference only trended toward statistical significance. An earlier age at onset, however, has been frequently associated with a higher severity of illness in OCD.Reference Taylor 26 , Reference de Mathis, Diniz and Hounie 27 It has to be noted that OCTD-SA and OCTD-noSA mean ages were significantly lower compared to the OCD-SA sample. Moreover, patients with OCTD-SA showed a higher rate of psychiatric comorbidities compared to OCD-SA, OCTD-noSA, and OCD-noSA groups, affective disorders and poly-comorbidities being the most frequent comorbid conditions, and an earlier age of comorbidity onset compared to the OCD-SA individuals. Similarly, in 2015, Storch and colleagues reported that, in patients with TS and TD, higher frequencies of suicidal thoughts and behaviors were frequently associated with comorbid disorders such as depression, OCD, and anxiety disorders.Reference Storch, Hanks and Mink 20 More recently, Fernández de la Cruz and colleagues, in a sample of patients with TS and chronic TD, reported that 78.13% of the individuals who died by suicide in the TS/TD cohort had other recorded psychiatric comorbidities vs 41.89% in the population-matched control group. This pattern was more pronounced for SAs, with almost all the patients in the TD/CTD cohort that had attempted suicide showing comorbidities (94.28%) vs less than half of the control subjects (46.14%).Reference Fernández de la Cruz, Rydell and Runeson 11 No reports showing differences in terms of age at onset or age at comorbidity onset are available for TS/TD with suicidal behaviors. With respect to patients with an OCD diagnosis and suicidal behavior, a recent study by the ICOCS group highlighted that patients with OCD with a previous SA showed a significantly higher rate of psychiatric comorbidities compared to patients with OCD with no SA (60% vs 17%), being TD the most frequent comorbidity (41.9%), followed by major depressive disorder and poly-comorbidity (8.1%) and TS (1.6%). No differences were found in terms of age at OCD onset.Reference Dell’Osso, Benatti and Arici 21 Previous studies also reported an increased risk of SA in patients with OCD with comorbid depressive, personality and substance abuse disorders.Reference Alonso, Segalàs and Real 22 , Reference Balci and Sevincok 23 , Reference Fernández de la Cruz, Rydell and Runeson 28

Positive family history resulted significantly higher in the OCTD-SA group compared to the OCD-SA group and compared to patients without SA. More in detail, the most common type of family history was represented by affective disorders in OCTD-SA and OCD-SA groups compared to OCTD-noSA and OCD-noSA groups. As regards suicidal behaviors in OCD, Alonso and colleagues in 2010 followed up from 1 to 6 years a sample of 218 outpatients and did not find any difference in terms of family history between patients with and without a history of SAs.Reference Alonso, Segalàs and Real 22 In 2016, Velloso and colleagues conducted a study with 548 patients with OCD comparing subjects with vs without suicidality and their associations with specific clinical characteristics. Of note, they found that having a family member who attempted suicide increased by 78% the risk of suicidality.Reference Velloso, Piccinato and Ferrão 14 No data are currently available in patients diagnosed with TD/TS reporting associations between family history and suicidal behaviors.

Finally, we analyzed prescribed pharmacological treatment, treatment response, and treatment resistance in the four subgroups. Patients with OCTD-SA compared to patients with OCD-SA showed a higher rate of antidepressant use, while OCTD-SA and OCD-SA samples showed a higher rate of antipsychotic augmentation treatments compared to OCD-noSA and OCTD-noSA groups. Lower treatment response was found in the OCTD-SA group compared to the OCD-SA, OCTD-noSA, and OCD-noSA groups and, consistently, a higher treatment resistance rate was found in the OCTD-SA and OCD-SA groups, compared to the patients with OCTD-noSA and OCD-noSA. Taken as a whole, these results highlight a higher severity in the OCTD-SA group; the presence of both TD/TS comorbidity and SA seem to require a higher rate of antidepressants and antipsychotics prescriptions, that often do not lead to a satisfying response and, ultimately, evolve in treatment resistance.Reference Walsh and McDougle 29 However, OCD-SA also showed higher rates of augmentation therapies with antipsychotics and higher rates of treatment resistance compared to OCTD-noSA and OCD-noSA groups. A possible explanation could be that, independently from the comorbidity with TS/TD, features related to treatment resistance in a context of higher severity of illness and distress may have increased the risk of SA. In 2008, a French group compared a sample of treatment resistant patients with OCD with a group of “good responders”: the inter-group analysis showed significantly higher rates of SA, psychiatric admissions and psychiatric comorbidities in treatment-resistant OCD subjects.Reference Hantouche and Demonfaucon 30 As regards TD/TS, to authors’ knowledge, there are no data on treatment resistance/response in TS/TD and suicidal behavior. However, Storch and colleagues in 2015 and Fernández de la Cruz in 2017 observed that tic severity, tic-related impairment, poor overall functioning, social withdrawal and the persistence of tics in adulthood—all common consequences of a low treatment response/treatment resistance—were more frequently related to an increased risk of SA.Reference Fernández de la Cruz, Rydell and Runeson 11 , Reference Storch, Hanks and Mink 20

Moreover, as mentioned on a recent paper on mediators in association between affective temperaments and suicide risk among psychiatric inpatients, a further assessment on affective temperaments, feeling of hopelessness, psychological pain, and mentalization skills through assessment instruments such as the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, and San Diego Autoquestionnaire (TEMPS-A), the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), the Psychological Pain Assessment Scale (PPAS) and the Mentalization Questionnaire (MZQ) should be performed in order to further enhance prevention of possible suicidal behavior. 31-35

The main limitations of our study include possible recall bias in the retrospective information that was collected using a cross-sectional design and the lack of information on the severity of the disorder (measured with specific psychopathological scales). Despite we did not use a structured interview for suicidal behaviors, such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS), suicidal behaviors were assessed through a new questionnaire for this study containing detailed open questions covering most of the main clinical information covered by the CSSRS. As regards suicidal behavior per se, it has to be noticed that, in the attempt of clarify the terminology of the current scientific literature in suicide, Silverman and colleagues in 2007 proposed a revised nomenclature for suicidology, accounting for a smaller number of terms capturing the essential components: suicide-related ideations, suicide-related communications (suicide threats and suicide plans), and suicide-related behaviors (self-harm, suicide attempts, and suicide).Reference Silverman, Berman, Sanddal, O’Carroll and Joiner 36 Future study on suicide behaviors and ideation should take into account these suggestions.

Moreover, further follow-up studies are needed to better characterize long-term course and suicidal behavior of patients with OCTD, their functional impairment and treatment response.

Disclosures

Beatrice Benatti, Silvia Ferrari, Nicolaja Girone, Sylvia Rigardetto, Benedetta Grancini, Anna Colombo, Monica Bosi, Caterina Viganò, Donatella Marazziti, Mauro Porta, Roberta Galentino, Domenico Servello, Giacomo Grassi, Federico Mucci, Liliana Dell’Osso, Matteo Briguglio, Domenico De Berardis, Orsola Gambini, Roberta Necci, Antonio Tundo, Umberto Alberto, Andrea Amerio, Sara De Michele, Mario Amore, Benedetta De Martini, Alberto Priori and Stefano Pallanti declare nothing to disclose.

Giuseppe Maina has served as consultant/speaker for Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Angelini, and Boheringer; Bernardo Dell’Osso has served as consultant/speaker for Janssen, Lundbeck, Angelini, Arcapharma, Livanova, and Neurapharma.