Introduction

In the year 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Version-5 (DSM-5) 1 included the specifier “with anxious distress” (ADS) for major depressive episode (MDE) in both major depressive disorders (MDD) and bipolar disorders (BD). This specifier consists in the presence of two or more of the following symptoms during most of the days: (1) feeling keyed up or tense (A1); (2) feeling unusually restless (A2); (3) difficulty concentrating because of worry (A3); (4) fear that something awful may happen (A4); and (5) feeling that the individual might lose control of himself or herself (A5). Several studies supported the validity of the DSM-5 criteria for MDE with ADS, while showing that it is a common clinical presentation with a prevalence ranging between 54% and 78%.Reference Gaspersz, Lamers and Kent 2 –Reference Zimmerman, Clark and McGonigal 7 Depressed ADS patients share higher rates of BD family history, including higher scores on hyperthymic temperament, greater severity of the disease, higher number of hospitalizations, higher rates of suicidal ideation, greater frequency of antidepressants (ADs) side effects and poor ADs response, and higher rates of chronicity,Reference Gaspersz, Lamers and Kent 2 –Reference Tundo, Musetti and Filippis 5 , Reference Zimmerman, Clark and McGonigal 7 –Reference Shim, Bae and Bahk 8 as compared with their counterpart without ADS. Notably, epidemiological and clinical characteristics of MDE with ADS are quite similar to those of mixed depression (MXD) (for a review of the different diagnostic criteria for MXD see Malhi et alReference Malhi, Byrow and Outhred 9): the prevalence of MXD ranges from 20% to 80% (depending on setting, samples and diagnostic criteria used),Reference Miller, Suppes and Mintz 10 –Reference Vazquez, Lolich and Cabrera 11 and patients with this diagnosis share the same features as mentioned above.Reference Miller, Suppes and Mintz 10 –Reference Stahl 14 This evidence suggests at least a partial overlap between MDE with ADS and MXD, but, to the best of our knowledge, no research study examined how these conditions might be interrelated.

In exploring this topic, the main problem is probably related to the controversial diagnostic criteria for MDX. The DMS-5 proposed the diagnosis of unipolar and bipolar MDE “with mixed feature” (MF) that implies the presence of at least three of the following manic symptoms: (1) elevated, expansive mood (MF1); (2) inflated self-esteem or grandiosity (MF2); (3) more talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking (MF3); (4) flight of ideas or racing thoughts (MF4); (5) increase in energy or goal-directed activity (socially, at work or school, or sexually) (MF5); (6) increased or excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (eg, engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretion, foolish business investments) (MF6); and (7) decreased need for sleep (MF7). 1

However, several authors criticized these DSM-5 criteria, as they do not include the three most common manic symptoms of MXD (psychic or motor agitation, irritability, and distractibility).Reference Koukopoulos 15 –Reference Perlis, Cusin and Fava 18 The rationale behind the exclusion of these symptoms has been that they are unspecific, because they recur in pure (hypo)mania, depression, and anxiety disorders. As a consequence of this exclusion, DSM-5 criteria for MDE with MF have a highest specificity (100%), but a low sensitivity (5.1%),Reference Stahl 14 and delineate a psychopathological condition that is extremely rare in clinical settings, with a prevalence ranging between 0% and 7.5%,Reference Tundo, Musetti and Filippis 5 , Reference Perugi, Angst and Azorin 13 , Reference Koukopoulos and Sani 16 , Reference Kim, Kim and Citrome 19 –Reference Takeshima and Oka 20 although in a large naturalistic study it reached 31%.Reference McIntyre, Woldeyohannes and Soczynska 4 Among the potential alternatives to DSM criteria for MXD proposed by many research groups (for a review see Malhi et alReference Malhi, Byrow and Outhred 9), Koukopoulos’ criteria have been validatedReference Sani, Vöhringer and Napoletano 21 and extensively used in the clinical practice since 1992.Reference Koukopoulos and Tundo 22 –Reference Koukopoulos and Koukopoulos 23 They consist in the presence of three or more of the following symptoms during a MDE (in MDD or BD): (1) psychic agitation or inner tension (K1); (2) racing or crowded thoughts (K2); (3) irritability or unprovoked feelings of rage (K3); (4) absence of retardation (K4); (5) talkativeness (K5); (6) dramatic description of suffering or frequent spells of weeping (K6); (7) mood lability and marked emotional reactivity (K7); and (8) early insomnia (K8).

The aim of this study is to analyze the relationships among symptom criteria for MXD and DSM-5 criteria for depression with ADS in patients with mood disorders. We chose to assess Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD in addition to DSM-5 criteria for MDE with MF to possibly overcome the lack of sensitivity of these latter.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were enrolled for an ongoing-research study described in full detail elsewhere.Reference Tundo, Musetti and Filippis 5 Briefly, the study cohort was consecutively recruited from January 2015 to January 2016 at the Section of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa, Italy and at the Institute of Psychopathology in Rome, Italy, two Italian centers specialized in mood and anxiety disorders. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18–75 years; (2) meeting DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for MDD single or recurrent episode, or for bipolar I or II disorder; (3) meeting DSM-5 criteria for a current MDE; and (4) a 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS21]Reference Hamilton 24 total score ≥14. Written informed consent for data collection and for their use in anonymous and aggregate form was routinely collected. The procedure was approved by the local ethical committee and is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Assessments

The diagnostic assessment was carried out by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5).Reference First, Williams and Karg 25 Depressive symptoms were assessed using the HDRS21, and the presence of the DSM-5 criteria for MDE with ADS and MF, and of Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD using a structured clinical interview. The rating scales were administered by RdF, CDG, VF, and LP, four psychiatrists experienced in mood disorders.

Statistical analysis

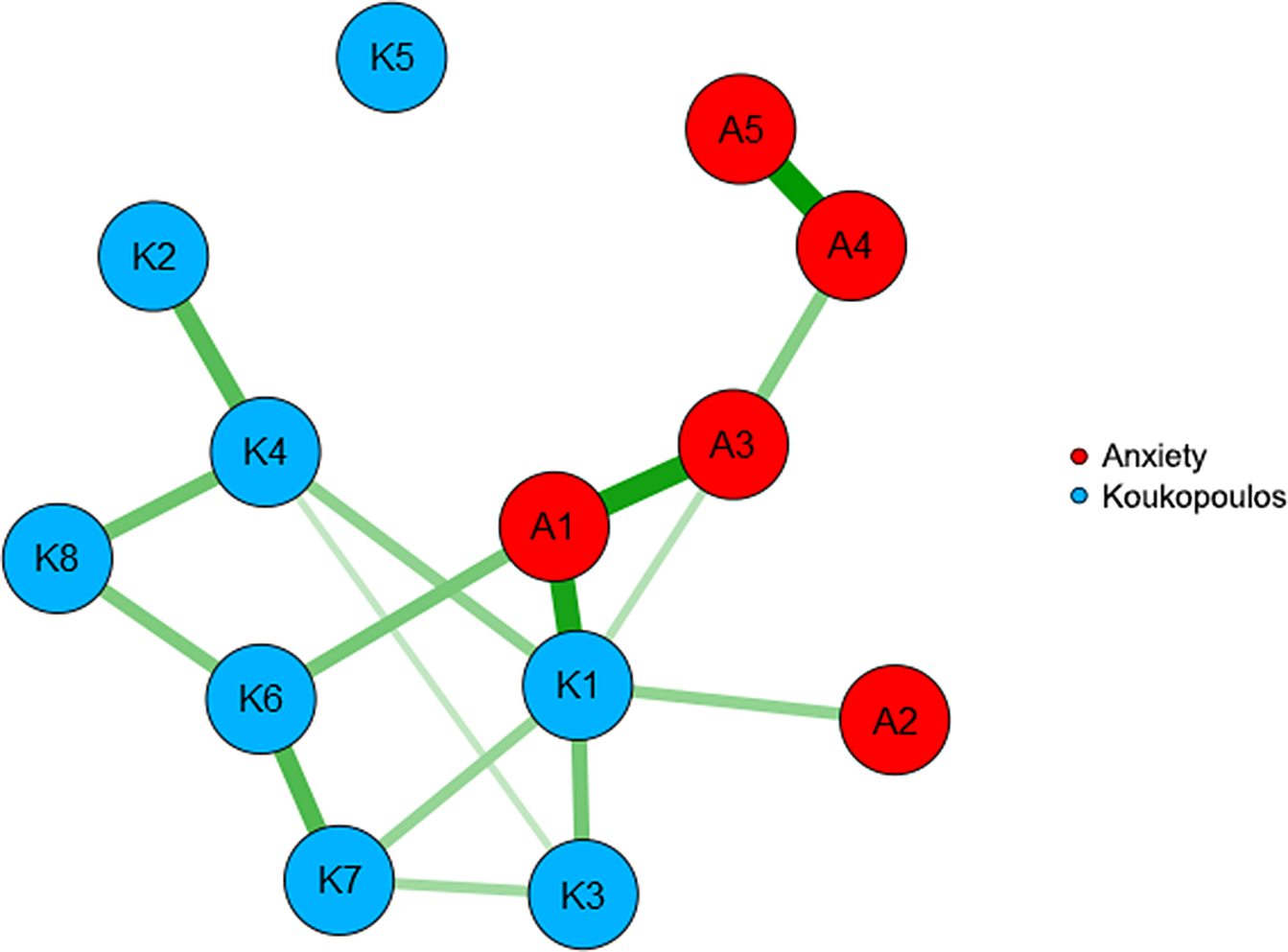

The relationship among the symptom criteria for mixed depression and MDE with ADS was investigated using the network analysis. A psychopathology network is displayed graphically as a set of symptoms (nodes) connected through a set of relations (edges). Green edges denote positive correlations, and red edges denote negative correlations. The stronger the correlation between symptoms, the thicker the edge is. Symptoms may be directly connected with each other or indirectly connected through other symptoms that act as a bridge. Node placement in the network is determined by the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm that places nodes with stronger average correlations closer to the center of the graph.Reference Fruchterman and Reingold 26

To estimate the network structure, an Ising model was fit, that is suitable for binary data (symptoms coded as present or absent).Reference van Borkulo, Borsboom and Epskamp 27 Tetrachoric correlation was used to measure the pairwise associations between symptoms. These coefficients approximate Pearson’s correlation coefficients, assuming bivariate normality for continuous variables underlying the binary ones. Then, the symptom network was obtained using the eLASSO algorithm, which is a computationally efficient model for estimating network structures from binary data. In the eLASSO method, lasso regularization is used in combination with logistic regression to estimate a sparse matrix, where zero entries indicate the conditional independence of the two variables given all the others; this allows to obtain a more parsimonious graph, hence, a better interpretation of the network structure.

To quantify the relevance of each node in the network, two centrality indices (strength and betweenness) of the Ising network were computed: strength is the sum of the absolute values of the connections of each symptom with the other symptoms, while betweenness is the degree to which a node lies on the shortest path between two other nodes. A central symptom is usually one with strong connections with the other symptoms, while a peripheral symptom is one with only few or weak connections. Centrality measures were standardized so that they have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation (SD) of 1; therefore, positive values higher than 1 indicate symptoms with a high centrality (>1 SD from the mean). The edge accuracy and the stability of centrality measures were investigated using bootstrap procedures, described by Epskamp et al.Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried 28 In particular, we tested whether the edges and centrality indices were robust to change in population size using the case-dropping procedure. In order to do so, we bootstrapped subsamples with increasingly higher percentages of dropped-out cases (from 5% to 75%), and measured correlations between the original centrality indices and those obtained in the reduced subsamples. If correlations remain high even after dropping a relevant proportion of cases, then edges and centrality indices can be considered stable. Lastly, we used the spin-glass community detection algorithm to identify clusters of symptoms. This is an approach derived from statistical physics, based on the so-called Potts model.Reference van Borkulo, Borsboom and Epskamp 27 In this model, each symptom can be in one of two states (present or absent), and the interactions between symptoms specify which pairs of symptoms tend to stay in the same state and which ones tend to have different states.

Network analysis was carried out using JASP, version 0.10.0.1 (https://jasp-stats.org) and R.

Results

The study sample included 241 patients, predominantly married women, with a mean age of 47 (±13.6) years (Table 1). One hundred and forty-two (58.9%) patients met DSM-5 criteria for MDE with ADS, 117 (48.5%) Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD, and 6 (2.5%) DSM-5 criteria for MDE with MF. Notably, 53 patients (22%) met only DSM-5 criteria for MDE with ADS, 24 (9.95%) only Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD, and 90 patients (37.3%) met both DSM-5 criteria for MDE with ADS and Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD. All six patients meeting DSM-5 criteria for MDE with MF met also Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Sample (n = 241).

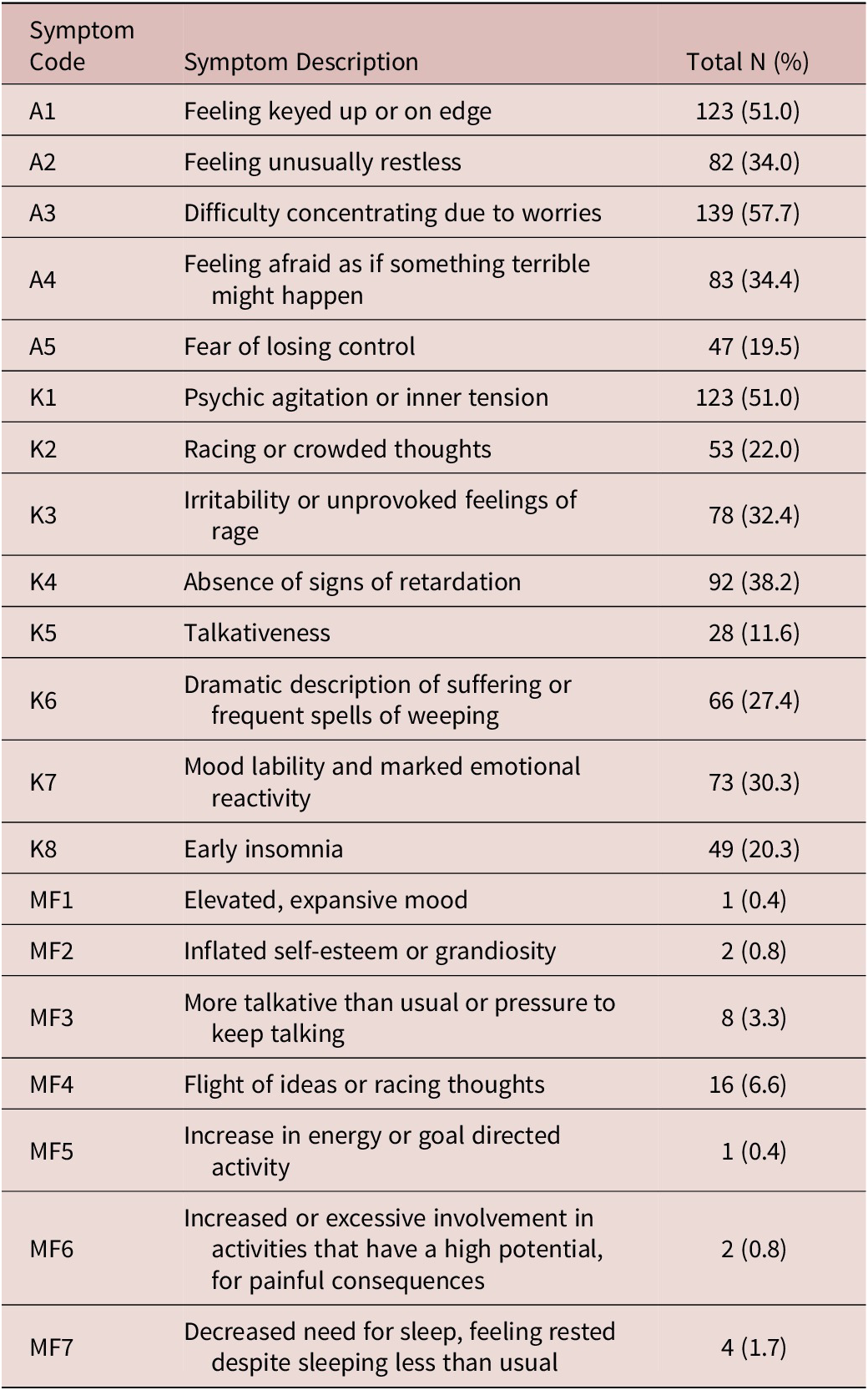

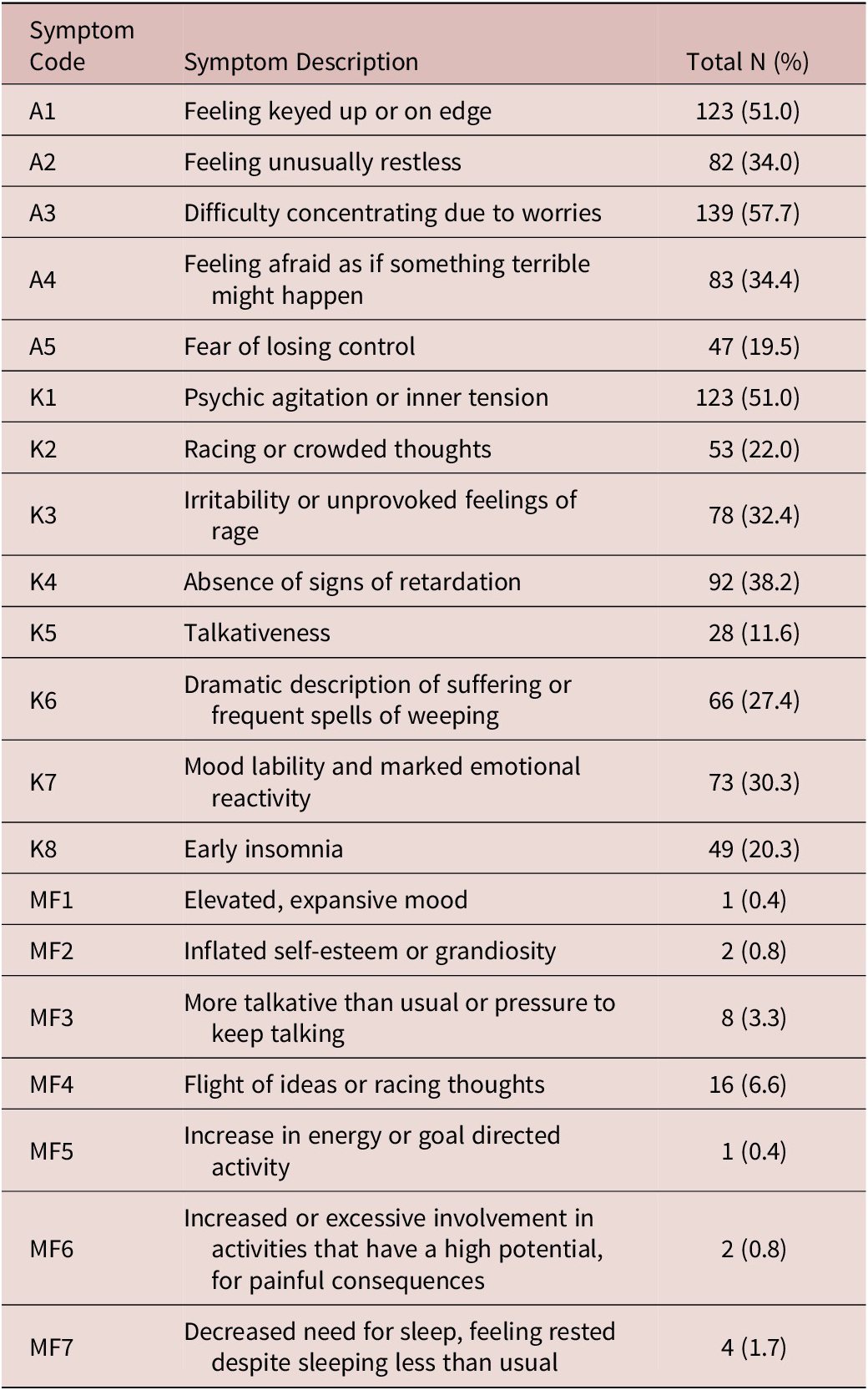

Table 2 provides the absolute and percentage frequencies of each symptom in the overall sample. Difficulty concentrating due to worries (A3), psychic agitation or inner tension (K1), and feeling keyed up or on edge (A1) were the most frequent symptoms.

Table 2. Symptom Frequency.

Abbreviations: A, major depressive episode with anxious distress (DSM-5 criteria); K, mixed depression, Koukopoulos’ criteria; MF, major depressive episode with mixed features (DSM-5 criteria).

The DSM-5 criteria for MDE with MF were very uncommon with frequencies ranging from 0.4% (MF1—elevated or expansive mood) to 6.6% (MF4—flight of ideas). Because of the small frequency of endorsement of these criteria, we focused only on the relationships between Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD and DSM-5 criteria for MDE with ADS in the subsequent analyses.

Network analysis

The LASSO network (Figure 1) shows that anxiety symptoms and mixed depression symptoms tend to cluster together: symptoms of MXD are located in the left part of the network, whereas those of ADS are located in the right part. Psychic agitation or inner tension (K1) and feeling keyed up or on edge (A1) have a central position in the network, and bridge mixed to anxiety depression.

Figure 1. LASSO network. Symptoms comprising the DSM-5 with anxious distress specifier are colored in red and those belonging to Koukopoulos’ criteria for mixed depression in turquoise. (Symptom labels are provided in Table 2).

Two anxiety symptoms are strongly correlated: fear of losing control (A5), which is located in a peripheral position, and feeling afraid as if something terrible might happen (A4). A similar strong link is found between feeling keyed up or on edge (A1) and difficulty concentrating due to worries (A3). Notably, feeling unusually restless (A2) is only connected with psychic agitation or inner tension (K1) when controlling for all other variables, and talkativeness (K5) is disconnected from the remaining symptoms. However, except for talkativeness (K5), Koukopoulos’ criteria are more densely populated of edges than anxiety symptoms.

The centrality measures (Table 3) indicate that symptom K1 (psychic agitation or inner tension) has the highest strength and that K1 and A1 (feeling keyed up or on edge) have the highest betweenness, that is they lie in the shortest paths connecting the other symptoms.

Table 3. Centrality Measures for the 13 Symptoms.

Symptom labels are provided in Table 2.

Abbreviations: A, major depressive episode with anxious distress (DSM-5 criteria); K, mixed depression, Koukopoulos’ criteria.

Network stability

Figure 2 shows that the connections among symptoms and the centrality measures remain stable even if the sample size is reduced by sampling smaller subsets of patients.

Figure 2. (A) Edge and (B) centrality stability. Correlations of edges and centrality measures with those of the original sample remain high (above 0.70) until 60% of patients are sampled.

Symptom clustering

Using the spinglass community detection algorithm, we identified 4 clusters of symptoms (Figure 3). The first comprising symptoms K1 (psychic agitation or inner tension), A1 (feeling keyed up or on edge), A2 (feeling unusually restless), A3 (difficulty concentrating due to worries); the second symptoms A4 (feeling afraid as if something terrible might happen); A5 (fear of losing control); the third symptoms K2 (racing or crowded thoughts), K4 (absence of signs of retardation), K8 (early insomnia); and the fourth symptoms K3 (irritability or unprovoked feelings of rage), K5 (talkativeness), K6 (dramatic description of suffering or frequent spells of weeping), and K7 (mood lability or marked emotional reactivity).

Figure 3. Community structure of the network. Four symptom communities can be identified, in different colors.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the relationship between MDE with ADS (DSM-5 criteria), and MXD (DSM-5 criteria and Koukopoulos’ criteria) in patients with unipolar and bipolar I and II depression. To reach the purpose of the study, we used network analysis.Reference Beard, Millner and Forgeard 29

Our findings indicate that only 2.5% of patients met DSM-5 criteria for MDE with MF, a figure in the range 0% to 7.5% of other studies.Reference Perugi, Angst and Azorin 13 , Reference Koukopoulos and Sani 16 , Reference Kim, Kim and Citrome 19 –Reference Takeshima and Oka 20 This prevented us from using these criteria in the network analysis. Moreover, the set of symptoms for MDE with MF does not include psychomotor agitation, which is the most common feature in Koukopoulos’ criteria in our sample with a prevalence of 51%. In our opinion, the exclusion of psychomotor agitation from DSM-5 criteria for MDE with MF would contributes to the low sensitivity of the MDE with MF diagnosis, with the severe consequence that a large number of patients with mixed depression are not recognized, so they receive AD monotherapy which could worsen the agitation and increase the risk of suicide.

Our findings confirm that there is a large overlap between MDE with ADS and Koukopoulos’ MXD with the majority of patients meeting the criteria for both diagnoses. Koukopoulos’ MXD criteria and DSM-5 ADS criteria are interconnected through the first Koukopoulos’ criterion for MXD (K1—psychic agitation or inner tension) and the first DSM-5 criterion for ADS (A1—feeling keyed up or on edge). The item feeling keyed up or on edge (A1), derived from the similar item of generalized anxiety disorder, designates the physical symptoms that accompany (ie, or are secondary to) the excessive anxious expectation regarding the routine life circumstances. 1 As Koukopoulos specified, the item psychic agitation or inner tension (K1) designates a primary physical manifestation (reported by patients as “an internal shaking or an electrical current passing through the body,” “I feel there are blades tearing through my guts”) that secondarily makes patient very anxious and fearful.Reference Koukopoulos and Sani 16 It is very hard for clinicians to differentiate between K1 and A1 criteria, as currently stand, during the limited time of a visit and when the patient has a severe depressive episode with both anxious and mixed features.

The results of network analysis support the key role of the psychomotor symptom K1 (inner tension/agitation), located in a central position and showing strong correlations with the other Koukopoulos’ symptoms. We argue that assessing the presence of this symptom, regardless of the subtle differences between physical tension and psychic agitation, should be at the core of the diagnostic process and should not be overlooked in the decisions regarding depression treatment. Again, other MXD symptoms with direct correlations with this core symptom should be considered, such as irritability and marked emotional reactivity, while the absence of retardation signs is implied (is a consequence of) by psychomotor agitation.

Concerning depression with anxiety, the direct links of the key symptom “feeling on edge” with “difficulty concentrating because of worries,” “feeling restless” could either have a causal interpretation (feeling on edge causes restlessness and poor concentration), or can be seen as mutual interactions, while “feeling afraid as if something terrible might happen” and “fear of losing control,” that are peripheral to the network, are very strongly correlated and are most likely symptoms that reinforce each other.

As far as the four clusters identified are concerned, cluster 1 corroborates the observation that criteria K1 and A1 are hardly distinguishable, while the other three clusters separate symptoms belonging to the same set of criteria.

The results of our study should be interpreted while keeping its strengths and limitations. The strength of the study is its in-depth assessment within a controlled setting which allows a fine-grained analysis of symptoms and capturing of the clinical phenomenology. Limitations include the cross-sectional design and the absence of a follow-up of the anxiety and MXD symptoms to determine whether they are stable and how they are causally related.

Conclusion

Anxiety depression (DSM-5 criteria) and mixed depression (Koukopoulos’ criteria) are two correlated sets of symptoms. The bridge symptoms include psychic agitation or inner tension and feeling keyed up or on edge that are difficult to distinguish in clinical practice. Clarifying whether DSM-5 criteria for MDE with ADS and Koukopoulos’ criteria for MXD identify the same psychopathological condition or two different psychopathological conditions and showing that bridge criteria, as they currently stand, generate overlapping and should be rewritten, is very relevant for clinicians. Such clarification could not only contribute to better sub-typing of patients with MDE, but also have important treatment implications, in particular concerning the use of antidepressants.Reference Sani, Napoletano and Vohringer 30

Disclosures

The authors do not have any disclosures, and the authors do not have any affiliation with or financial interest in any organization that might pose a conflict of interest.