Introduction

Several studies highlighted a significant association between social anxiety disorder (SAD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). According to the literature, the comorbidity between SAD and full-blown OCD may lie between 15% and 43.5% in the general population, and between 12% and 42% in clinical samples.Reference Baldwin, Brandish and Meron1, Reference Assunção2 From a clinical point of view, both OCD and SAD show an early onset and generally a chronic course, with a high risk of developing other comorbid disorders, and so a long-term treatment strategy is usually required to prevent relapses.Reference Bruce, Yonkers and Otto3–Reference Isomura, Brander and Chang9 The most common comorbid disorders among OCD patients are anxiety disorders (75.8%), in particular SAD (43.5%), followed by mood disorders (63.3%), in particular major depression disorder (MDD) (40.7%); on the other hand, OCD has been reported as a frequent comorbidity in anxiety disorders.Reference Bartz and Hollander10, Reference Ruscio, Stein and Chiu11 Despite that, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorder, fifth edition (DSM-5), OCD has been distinguished from anxiety disorders, and it is now included in a specific category encompassing also related conditions such as body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), trichotillomania, hoarding disorder and skin-picking disorder. Similar changes have also been made in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11): while the previous categories of “Phobic anxiety disorders” (which included also SAD, namely “social phobias”) and “Other anxiety disorders” were merged in the broader group of “Anxiety and fear-related disorders,” OCD was removed from anxiety disorders. The new category of “Obsessive-compulsive related disorders” has been created, featuring also BDD, olfactory reference disorder, hypochondriasis, hoarding disorder, and body-focused repetitive behavior disorders.

However, some researchers stressed that this novelty, while better highlighting the specific features of obsessive-compulsive spectrum, neglects the shared features between OCD and anxiety disorders, which are instead demonstrated by both the frequently reported comorbidity between these conditions and the response to similar treatments.Reference Baldwin, Brandish and Meron1, Reference Assunção2 As already mentioned, the incidence of anxiety disorders in OCD patients seems to be more frequent among subjects with an early onset of the disorders. Authors have reported that, compared with the OCD patients with a late onset, those with an early onset (<10 years) were more likely to suffer from other obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders, such as tic disorder and hoarding disorder, as well as panic disorder and SAD.Reference Janowitz, Grabe and Ruhrmann12–Reference Hannah Frank, Elyse Stewart and Walther15 Moreover, the literature also pointed out that different kinds of anxiety disorders seem to be associated with specific phenotypes of OCD: in this framework, Nestadt et al. suggested a classification of OCD phenotypes based on comorbid relationships with anxiety/affective disorders.Reference Bartz and Hollander10, Reference Ruscio, Stein and Chiu11, Reference Nestadt, Addington and Samuels16, Reference Nestadt, Di and Riddle17 According to this hypothesis, some authors investigated in a sample of 1001 OCD patients the specific features of OCD patients with comorbid SAD symptoms, such as fear of judgment, interpersonal sensitivity, and low self-esteem.Reference Assunção2 Results showed that OCD patients with SAD symptoms were more frequently men with a lower socioeconomic status and were often affected with other OCD spectrum disorders and/or with binge eating disorder. Moreover, evidence from other studies reported also that when SAD and OCD co-occur in comorbidity, especially if both disorders have their onset in childhood, frequently patients would show more severe symptoms, a poor response to both drugs and psychotherapy strategies, and a worse outcome.18–22 Again, another cluster analysis on 317 OCD patients highlighted how OCD symptom dimensions may show relationships to comorbid disorders, for example, aggressive, sexual, religious, and somatic obsessions, and checking compulsions were associated with comorbid anxiety disorders and MDD.Reference Hasler, LaSalle-Ricci and Ronquillo23

Others also addressed the presence of OCD subthreshold spectrum symptoms and associated features in SAD patients. In particular, a strong association was found between perfectionism, as well as BDD symptoms and SAD, 24–Reference Hasler, LaSalle-Ricci and Ronquillo26 while outlining a landscape of recurrent patterns of symptoms spread across these two conditions, as well as a frequent co-occurrence in the form of comorbidity. Recently, it emerged that the co-occurring presence of OCD and SAD may be associated also with problematic Internet use (PIU), a label used to describe the combination of addiction-like symptoms and social problems in subjects spending huge amounts of time on the Internet.Reference Vries, Nakamae and Fukui27 Taken together, these findings seem to suggest the presence of a specific clinical presentation in patients with a diagnosis of both OCD and SAD. Moreover, the literature has frequently reported a significant comorbidity between MDD and SAD, as well as OCD. Whereas about 59.2% of MDD subjects meet the criteria for at least one anxiety disorderReference Kessler, Berglund and Demler28 and the most common anxiety disorder in comorbidity with MDD seems to be SAD, Reference Adams, Balbuena and Meng29 among SAD patients, up to 70% of subjects meet the criteria for MDD.Reference Adams, Balbuena and Meng29, Reference Merikangas and Merikangas30 In particular, some SAD and OCD symptoms, such as interpersonal sensitivity and obsessive rumination, respectively, seem to be common in MDD patients.Reference Pini, Cassano and Simonini31–Reference Murphy, Moya and Fox35 This evidence seems in line with the hypothesis, increasingly reported in the literature, that repetitive negative thinking (RNT), characterized by worry and ruminations (including also brooding on social difficulties and obsessive doubts), should be considered as a broader, transnosological dimension: in particular, RNT has been demonstrated to increase vulnerability to both anxiety and depressive disorders and, as a shared risk factor, it might be a common underpinning for different kinds of psychiatric conditions, including SAD and OCD.Reference Nolen-Hoeksema , Wisco and Lyubomirsky36–Reference Carmassi, Corsi and Bertelloni38 However, only a few studies addressed the overlapping features between SAD and OCD, as well as the relationship between SAD and OCD symptoms and MDD, and so this topic remained poorly explored, in both clinical samples and in the general population. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the correlations between SAD and OCD spectrum in a clinical sample composed of subjects with SAD, OCD, and MDD, as well as in a healthy control subjects. In particular, our objective was to investigate the presence of a possible shared core of symptoms among these conditions, which may eventually be related to ruminative thinking. According to a dimensional approach, Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Harnett Sheehan39 identifying possible transnosographic symptoms among psychiatric conditions may lead to a better understanding of psychopathology, eventually overcoming the issues of the current nosological classification, such as the high rates of comorbidity. In this framework, a better understanding of the nuclear features underlying different psychiatric disorders may also allow an improvement of current therapeutic strategies, especially for treatment-resistance patients.

Methods

The clinical sample was recruited among outpatients followed at eight Italian psychiatric departments (Universities of Pisa, Siena, Florence, Bologna, Trieste, L’Aquila-Pescara, Messina, and Cagliari). Eligible subjects for the three clinical groups had to meet DSM-IV TR diagnostic criteria for (1) MDD without a current diagnosis or a history of SAD or OCD; (2) SAD without a current diagnosis or a history of MDD or OCD; and (3) OCD without a current diagnosis or a history of MDD or SAD. Exclusion criteria were age below 18 or over 65 years; substance abuse/dependence; presence or history of psychosis; presence of neurodegenerative diseases or severe somatic comorbidities; and intellectual impairment. The healthy control group (HC) was recruited among university students of the same Italian university departments. The presence of a psychiatric disorder was an additional exclusion criterion for this group. Eligible subjects were assessed by means of The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Sheehan40, Reference Dell’Osso, Cassano and Sarno41 to evaluate the presence of full-blown diagnosis. Patients with mood disorders and students who met the MINI criteria for full-blown SAD or OCD were excluded from the analysis. Subsequently, patients were assessed by means of the Structured Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum (SCI-OBS) and by the Structured Clinical Interview for Social Phobia Spectrum (SCI-SHY). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria of Pisa (CEAVNO) approved all recruitment and assessment procedures. All participants provided a written informed consent after having received a clear description of the study and having the opportunity to ask questions.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) is a brief structured interview designed by both American and European psychiatrists, commonly employed as a diagnostic instrument for psychiatric disorders in research settings. The MINI was specifically designed for rapid administration (about 15 minutes), and it has been demonstrated to be reliable in multicenter clinical trials and in epidemiological and clinical studies.Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Sheehan40, Reference Dell’Osso, Cassano and Sarno41

The Structured Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum (SCI-OBS) is composed of 196 dichotomous items, grouped in seven domains: obsessive-compulsive traits during childhood and adolescence, doubt, hypercontrol, temporal dimension, perfectionism, repetition and automation, and obsessive-compulsive themes. The instrument is devised to evaluate not only full-blown OCD, but also the wide spectrum of subthreshold symptoms or isolate traits that can be found in general population or in clinical groups of patients with other psychiatric disorders. The SCI-OBS showed good psychometric properties, with a Kuder–Richardson coefficient for single domains ranging from 0.61 to 0.93.Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Harnett Sheehan39

The Structured Clinical Interview for Social Phobia Spectrum (SCI-SHY) is an instrument developed to evaluate the broad range of manifestations associated with SAD spectrum, including full-blown as well as subthreshold symptoms of SAD. It is composed of 167 dichotomous items divided into four domains: social phobic traits during childhood and adolescence, interpersonal sensitivity, behavioral inhibition and somatic symptoms, and specific anxieties and phobic features. The instrument includes also an appendix, substance use, considering the frequent comorbidity between SAD symptoms and substance use disorders. The Kuder–Richardson coefficient ranges from 0.87 to 0.94.Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Harnett Sheehan39

Statistical analyses

The chi-square test was employed to compare the rate of men and women among groups. Univariate analysis of variance (ANOVAs) was used for intergroup comparisons of continuous variables (age, SCI-SHY, and SCI-OBS scores), followed by post hoc analysis with Tukey’s tests. Correlations between SCI-SHY domains and SCI-OBS domains in each group were investigated by Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 20 (IBM, Statistical Package for Social Sciences [SPSS, 2011]).

Results

We globally recruited 209 subjects: 78 men, 131 women; mean age = 32.7 ± 11.4 years. The sample was composed as follows: 56 patients affected by OCD, 51 by SAD, 43 by MDD, and 59 HC.

The results showed that groups did not significantly differ with respect to gender, with a rate of women and men of 66.1% (N = 39) versus 33.9% (N = 20) among HC, 53.6% (N = 30) versus 46.4% (N = 26) in the OCD group, 56.9% (N = 29) versus 43.1% (N = 22) in the SAD group, and 76.7% (N = 33) versus 23.3% (N = 10) in the MDD group (χ 2 = 6.65, p = 0.084). The mean age in the HC group was 24.1 ± 3.4 years, 35.1 ± 11.6 in the OCD group, 33.5 ± 10.6 in the SAD group, and 40.2 ± 12.1 in the MDD group (F = 24.59, p = 0.001). The MDD group mean age was significantly higher than in the HC (p = 0.001), OCD (p = 0.04), and SAD group (p = 0.006), while both the SAD and the OCD subjects were significantly older than the HC group (p = 0.001).

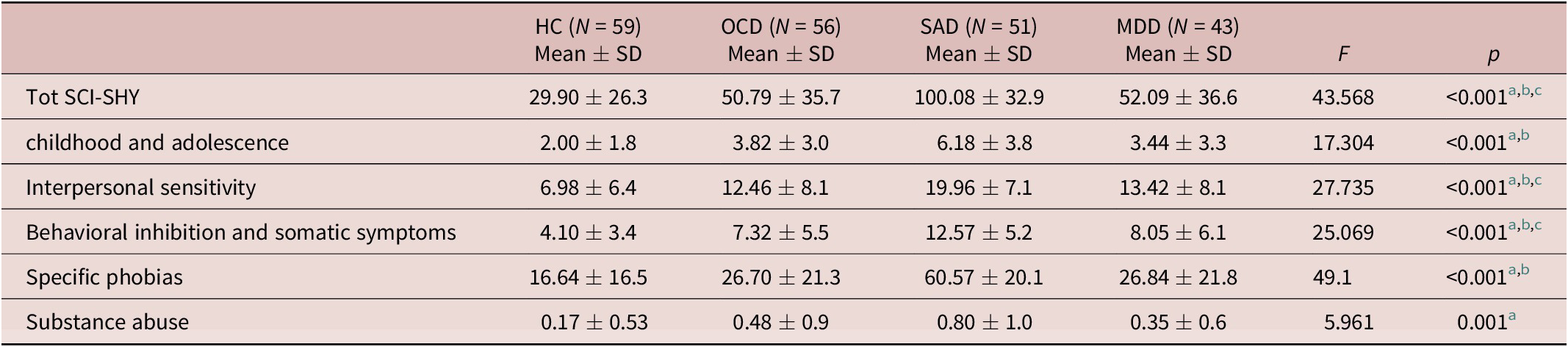

Considering the SCI-SHY, SAD patients showed significantly higher scores than HC (100.08 ± 32.9 versus 29.90 ± 26.3; p < 0.05), MDD (100.08 ± 32.9 versus 52.09 ± 36.6; p < 0.05) and OCD patients (100.08 ± 32.9 versus 50.79 ± 35.7; p < 0.001), as well as significantly higher scores than the other groups in all SCI-SHY domains. OCD and MDD patients showed significantly higher SCI-SHY total scores than HC (p < 0.05). When compared with the latter, the OCD patients scored significantly higher on all SCI-SHY domains, while MDD patients only on the Interpersonal sensitivity and on Behavioral inhibition and somatic symptoms domains. On the Substance abuse appendix, SAD patients reported significantly higher scores than HC and MDD groups, with no significant differences with the OCD group ( Table 1).

Table 1. SCI-SHY total and domain scores among groups.

a SAD>HC, MDD, p < .05

b SAD>OCD, p < 0.001; OCD>HC, p < 0.05

c MDD>HC, p < 0.05

OCD patients reported significantly higher scores on all SCI-OBS domain and total scores than HC (81.50 ± 29.5 versus 37.69 ± 22.6; p < 0.005), MDD (81.50 ± 29.5 versus 49.12 ± 26.2; p < 0.005) and SAD patients (81.50 ± 29.5 versus 54.02 ± 31.5; p < 0.005), with the exception of Doubt domain, that was similar in OCD and SAD patients. Moreover, SAD patients showed significantly higher scores than HC on SCI-OBS total (p < 0.05), Childhood and adolescence, Doubt, and Hypercontrol domain scores, while MDD patients scored significantly higher than HC only on the SCI-OBS Hypercontrol domain ( Table 2).

Table 2. SCI-OBS total and domain scores among groups.

a OCD>HC, MDD, p < 0.005

b OCD>SAD p < 0.005

c SAD>HC, p < .05

d MDD>HC, p < 0.05

While considering the correlation analysis between SCI-OBS and SCI-SHY, significant findings were found in HC between most of the domains, with the strongest correlation between SCI-OBS Doubt and SCI-SHY Interpersonal sensitivity domains (r = 0.743; p < 0.001), followed by SCI-OBS Obsessive-compulsive themes domain and SCI-SHY Interpersonal sensitivity (r = 0.739; p < 0.001) and Specific anxieties and phobic features domains (r = 0.706; p < 0.001) ( Table 3). SAD patients showed significant correlations between all SCI-OBS and SCI-SHY domains, with the exception of SCI-SHY Specific anxieties and phobic features, and SCI-OBS Temporal dimension and Perfectionism domains. Stronger correlations were found between SCI-OBS Childhood and adolescence, Doubt, and Hypercontrol domains and SCI-SHY Childhood and adolescence, Interpersonal sensitivity, and Behavioral inhibition and somatic symptoms domains. The overall highest correlation (r = 0.688; p < 0.001) was between SCI-SHY Interpersonal sensitivity and SCI-OBS Doubt domains, followed by the correlation between SCI-SHY Interpersonal sensitivity and SCI-OBS Hypercontrol domains (r = 0.674; p < 0.001), as well as between SCI-SHY Childhood and adolescence and SCI-OBS Doubt domains (r = 0.626; p < 0.001) ( Table 4). Among OCD patients, correlations between SCI-SHY and SCI-OBS were lower in number and less robust. Only SCI-OBS Childhood and adolescence, Doubt, Hypercontrol and Obsessive and compulsive themes domains significantly correlated with all SCI-SHY domains, while SCI-OBS Repetition and automation domain reported a significant correlation only with SCI-SHY Childhood and adolescence domain. The strongest correlations were found between SCI-OBS Obsessive and compulsive themes and SCI-SHY Interpersonal sensitivity (r = 0.541; p < 0.001) and Behavioral inhibition and somatic symptoms domains (r = 0.518; p < 0.001), and between SCI-OBS Doubt and SCI-SHY Interpersonal sensitivity (r = 0.474; p < 0.001) ( Table 5). The MDD patients showed significant correlations between all SCI-SHY and SCI-OBS domains, with the exception of SCI-OBS Temporal dimension and SCI-SHY Childhood and adolescence and Specific phobias domains. The highest correlations in this latter group was noted between SCI-SHY Interpersonal sensitivity and SCI-OBS Doubt (r = 0.545; p < 0.001), Hypercontrol (r = 0.583; p < 0.001) and Obsessive and compulsive themes (r = 0.556; p < 0.001) domains, followed by those between SCI-SHY Behavioral inhibition and somatic symptoms and Specific anxieties and phobic features domains and SCI-OBS Hypercontrol and Obsessive and compulsive themes domains ( Table 6). As for as the SCI-SHY Substance abuse appendix was concerned, we found a significant correlation with SCI-OBS Repetition and automation domain in the MDD group only.

Table 3. Correlations between SCI-SHY and SCI-OBS domains scores in HC.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.001

Table 4. Correlations between SCI-SHY and SCI-OBS domains scores in SAD group.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.001

Table 5. Correlations between SCI-SHY and SCI-OBS domains scores in OCD group.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.001

Table 6. Correlations between SCI-SHY and SCI-OBS domains scores in MDD group.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.001

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate and compare the presence of possible associations between SAD and OCD spectrum in a clinical population composed by different diagnostic groups and in HC recruited in different centers. In particular, we focused on exploring patterns of association between specific features of OCD and SAD spectrum. Our data suggest that these two conditions are significantly related in all groups of subjects investigated. First of all, we found significant levels of SAD symptoms in both MDD and OCD patients when compared with HC. However, while in the MDD group SAD symptoms seemed to be limited to those related to behavioral inhibition and interpersonal sensitivity, OCD patients showed higher levels of all SAD dimensions. On the other hand, SAD patients reported significantly higher levels of OCD symptoms than HC and in particular on the dimensions of hypercontrol (where also MDD subjects reported higher scores) and doubt. It is noteworthy that SAD and OCD patients scored equally high on SCI-OBS Doubt domain. Moreover, SAD patients showed a significant correlation between the presence in childhood and adolescence of both SAD and OCD symptoms, as well as between the presence of obsessive doubts and hypercontrol and SAD interpersonal sensitivity and inhibition during lifetime. The presence of symptoms like obsessive doubts and hypercontrol in SAD patients with higher interpersonal sensitivity, behavioral inhibition, and somatic symptoms may suggest a possible role of OCD traits as an indicator of more severe forms of SAD. Within this framework, our results seem in line with previous studies that reported how patients with an early onset SAD frequently show higher levels of behavioral inhibition and impairment, as well as a higher frequency of comorbidities, including with OCD.Reference Lim, Ha and Shin42, Reference Menezes, Fontenelle and Versiani43 Taken together, this pattern might also suggest a possible role of OCD traits in worsening and chronicizing SAD symptoms.Reference Lochner and Stein24, Reference Lim, Ha and Shin42–Reference Nagata, Yamada and Teo46 These findings seem to be in agreement with those of a previous study, Reference Nagata, Yamada and Teo46 which evaluated the relationship between SAD and “hikikomori syndrome,” a severe form of social withdrawal defined as isolation lasting more than 6 months.Reference Kato, Tateno and Shinfuku47 This study showed that SAD patients fulfilling the criteria for hikikomori had an earlier onset and more severe symptoms than non-hikikomori SAD, together with higher rates of a comorbid OCD. Moreover, according to our results, the interpersonal sensitivity in SAD patients showed the highest correlation with obsessive doubts. These data, which suggest possible specific (and eventually more severe) clinical presentations in patients with SAD showing OCD traits, are also somewhat in line with the literature that stresses the similarity between SAD and BDD, considering also this latter as a possible link between the overlapping SAD and OCD spectrum.Reference Lochner and Stein24–Reference Egan, Wade and Shafran26 It is noteworthy that Lochner et al.Reference Lochner and Stein24 reported that BDD, classified in DSM-5 as an OCD-related condition, was more common in SAD than in OCD: SAD and BDD would share, as a common basis, negative interpretation biases for ambiguous social information and fear of negative evaluations, and even the presence of interpersonal sensitivity and ruminative thinking. Fang and HoffmanReference Fang and Hofmann44 again suggested a similarity between BDD and Taijin Kyofusho (TKS), a Japanese conceptualization of SAD frequently comorbid with OCD. In TKS the concern is about offending others due to one’s physical deformities, often with an impaired insight.Reference Nagata, Matsunaga and van Vliet45 Moreover, others reported that OCD patients suffering from BDD seem to show peculiar features, such as an earlier onset of OCD symptoms, greater severity of OCD, comorbid MDD and anxiety symptoms, as well as poorer insight and higher suicidal risk.Reference Conceição Costa, Chagas Assunção and Arzeno Ferrão48 The link between OCD and SAD spectrum seems to be confirmed in our study by their wide association also when subthreshold, as reported among HC. Specifically, even in this group, OCD-related features like doubt seem to be associated with interpersonal sensitivity, while obsessive-compulsive contents are highly associated also with specific phobias typical of SAD. Interestingly, in the OCD group, fewer and lower correlations were detected between OCD and SAD symptoms, with a different pattern, in the sense that SAD symptoms were actually associated mainly with obsessive-compulsive contents. The globally lower and more restricted correlation of SAD and OCD symptoms in OCD patients compared with the higher correlations found in SAD patients may be explained introducing an increased OCD variability paradigm, as already described by Nestadt et al.Reference Nestadt, Addington and Samuels16, Reference Nestadt, Di and Riddle17 In particular, Assuncao et al.Reference Assunção2 already hypothesized that only a specific phenotype of OCD patients would show SAD features, and in particular male patients with a lower socioeconomic status, comorbid BDD and/or Tourette syndrome, as well as dysthymia and binge eating disorder. Our results are partially in line with this latter study, Reference Assunção2 which also reported interpersonal sensitivity, low self-esteem and fear of judgment as the most common SAD features represented in OCD patients. In our OCD group the highest correlations were actually found between the presence of obsessive-compulsive contents, interpersonal sensitivity and behavioral inhibition. MDD patients showed a significantly higher presence than in HC of specific symptoms, such as SAD interpersonal sensitivity and behavioral inhibition, as well as OCD-like tendency to hypercontrol. The highest correlations were measured between interpersonal sensitivity and obsessive doubts, hypercontrol, and the presence of obsessions/compulsions. In addition, hypercontrol and proper obsessions/compulsions were also significantly related to behavioral inhibition and specific phobias. This finding seems to confirm the significant presence of some SAD and OCD symptoms in MDD patients, frequently reported in the literature.Reference Pini, Cassano and Simonini31 Moreover, the presence in HC and MDD patients of a correlation between interpersonal sensitivity and OCD symptoms (specifically with obsessive doubts) may suggest a possible association of these dimensions, both linked to RNT, in a transnosological way. In a more recent study, it was suggested that the development of MDD in association with anxiety disorders and vice versa seems to be significantly mediated by the presence of RNT.Reference Spinhoven, Van Hemert and Penninx49 This evidence suggests that RNT, in the form of worry and ruminations, may constitute an important transdiagnostic factor susceptible of a transdiagnostic treatment. In particular, RNT seems to reflect a common pattern of ruminative thinking among these two conditions. Although the tendency to rumination may eventually feature some differences in the specific kind of contents, this cognitive pattern shows correlations among all three groups. In our study we observed how doubt and interpersonal sensitivity seem to be linked in a transnosological fashion. The literature shows how rumination may lead to both anxiety and depression through a variety of mechanisms. When subjects with a higher proneness to rumination were exposed to tasks that may enhance the ruminative response, requiring one to focus on self-centered questions (such as the ruminative response task), they showed more maladaptive, negative thinkingReference Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 50; less effective coping with problemsReference Lyubomirsky, Caldwell and Nolen-Hoeksema 51–Reference Watkins and Moulds54; uncertainty and immobilization in the implementation of solutionsReference Ward, Lyubomirsky and Sousa55, Reference Lyubomirsky, Kasri and Chang56; and lower willingness to engage in distracting, mood-lifting activities.Reference Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 57 Other studies demonstrated also that individuals with high rumination scores are characterized by impaired inhibition and switching in working memory when negative information is in focal attention.Reference Ansari, Derakshan and Richards58, Reference Joormann59 Further Meiran et al.Reference Meiran, Diamond and Toder60 noted that OCD and depressive ruminations are both associated with similar cognitive rigidity, while suggesting that rigidity may be a common risk factor and perhaps even a common etiological factor for both disorders. As for SAD, Kashdan et al.Reference Kashdan and Roberts61 suggested that SAD and depressive symptoms could have a synergistic effect in predicting post-event ruminations about social interactions. Moreover, ruminative thinking and interpersonal sensitivity are symptoms frequently associated also with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and with autistic traits (AT), which are often comorbid with SAD, obsessive symptoms, and mood disorders.Reference Dell’Osso, Dalle Luche and Maj62 This clue is particularly interesting considering the increasing body of studies suggesting a possible role of AT as a promoting factor for different psychiatric conditions.63–70 As Dell’Osso et al.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita63, Reference Dell’Osso, Muti and Carpita71 pointed out, ruminative thinking, often associated with subthreshold AT, could be considered as a common transnosological underpinning of several different psychiatric disorders that may affect prognosis and increase the risk of chronic course and suicidality. According to this paradigm, our study may contribute in supporting the dimensional association between depressive ruminations, SAD and OCD subthreshold symptoms, considering the high correlations, found also in MDD patients and in HC, between doubt and interpersonal sensitivity. The present study suffers from a series of limitations that should be acknowledged. First, its cross-sectional design does not allow us to infer about causal relationships. Second, during the clinical interviews, it would be possible that retrospective information, such as those about symptoms in childhood, were affected by recall bias. Third, groups were not homogeneous in terms of age, and this difference may have affected the results, especially the comparison among groups. However, the small sample size did not allow us to perform a random extraction for obtaining homogeneous groups. Moreover, subjects were recruited in several centers, coming from different geographical locations, and this difference may have led to bias when interpreting our results. Finally, considering also the multicentric design of the study, the sample size was very limited and thus our results may not be representative of the investigated populations. Globally, this is an exploratory study, and further researches in wider sample and with longitudinal design are warranted to clarify the relationship between OCD and SAD spectrum.

Conclusions

OCD and SAD spectrum significantly overlap among clinical and general population. In particular, we are of the opinion that interpersonal sensitivity and obsessive doubts may represent a common core for SAD, OCD, and MDD.

Disclosures.

Barbara Carpita, Dario Muti, Alessandra Petrucci, Francesca Romeo, Camilla Gesi, Donatella Marazziti, Claudia Carmassi, and Liliana Dell’Osso have nothing to disclose.