Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is an early onset disorder characterized by perfectionism, need for control, and cognitive rigidity.Reference Butcher, Mineka and Hooley1 It constitutes a relatively under-researched area of psychiatry, and its nosological status is currently under review. Based on clinical similarities, arguments can be made for re-classifying OCPD together with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).Reference Murphy, Timpano, Wheaton, Miguel and Greenberg2, Reference Fineberg, Sharma, Sivakumaran, Sahakian and Chamberlain3 To date, however, little clinical or neurosciences data have addressed this issue, with few studies investigating “pure” OCPD in the absence of other major psychiatric comorbidity. Therefore, OCPD was not included in the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) obsessive compulsive and related disorder (OCRD) cluster, though its classification is undergoing review for the forthcoming World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases Version 11 (ICD-11). A better understanding of the neuropsychological status of OCPD would help inform the debate.

The prevalence of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is estimated to be high, with up to almost 8% of the general population thought to be affected.Reference Grant, Hasin and Stinson4 OCPD also represents one of the commonest personality disorders; a (weighted) life prevalence of 2% has been estimated in community samples,Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and Cramer5 with males and females roughly equally affected.Reference Grant, Mooney and Kushner6 OCPD shares a high comorbidity with many psychiatric disorders, especially those characterized by compulsive behavior, including OCD, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), and eating disorders.Reference Murphy, Timpano, Wheaton, Miguel and Greenberg2, Reference Pinto, Mancebo, Eisen, Pagano and Rasmussen7–Reference Phillips and McElroy9 Moreover, studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence of OCPD in cases of OCD compared with other “noncompulsive” comparator disorders, such as panic disorder, major depressive disorder,Reference Diaferia, Bianchi, Bianchi, Cavedini, Erzegovesi and Bellodi10, Reference Gordon, Salkovskis, Oldfeild and Carter11 and other forms of personality disorder.Reference Albert, Maina, Forner and Bogetto12 Nevertheless, a high frequency of OCPD among individuals with OCD does not necessarily imply a unique relationship between the 2 conditions.Reference Starcevic, Berle and Brakoulias13 Interestingly, several studies have also found a hereditary link between OCD and OCPD, suggesting that the first-degree relatives of OCD-affected probands are more likely to suffer with OCPD than the first-degree relatives of unaffected subjects, even after controlling for the potentially confounding effect of OCD in the relativesReference Calvo, Lazaro, Castro-Fornieles, Font, Moreno and Toro14 or OCPD in the probands.Reference Samuels, Nestadt and Bienvenu15, Reference Bienvenu, Samuels, Wuyek, Liang, Wang and Grados16 These data provide stronger evidence for a psychopathological relationship between OCPD and OCD.

The overlap between OCD and OCPD may relate to the similarities in the symptom profile that exist across the 2 disorders, such as perfectionism and preoccupation with detail, and so the disorders may be confused.Reference Eisen, Coles and Rasmussen17 Despite this, OCPD can be distinguished from OCD by its absence of engagement in highly repetitive, distressing, and disabling obsessions or compulsions.Reference Butcher, Mineka and Hooley1, Reference Pinto, Stienglass, Greene, Weber and Simpson18 A recent studyReference Pinto, Stienglass, Greene, Weber and Simpson18 of OCPD patients revealed they were better able to delay gratification than OCD patients, and this was highlighted by the authors as key feature of the behavioral rigidity associated with OCPD. Notwithstanding such differences, emerging evidence suggests that disorders marked by compulsivity, including OCD and OCPD, are associated with shared aspects of neuropsychological impairment in specific domains, including behavioral inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and executive planning, which can be demonstrated using laboratory-based tasks.Reference Fineberg, Chamberlain and Goudriaan19–Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Robbins and Sahakian21

OCD patients have demonstrated deficits in pre-potent motor inhibition, as measured on the stop-signal reaction time taskReference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Robbins and Sahakian21, Reference Aron, Fletcher, Bullmore, Sahakian and Robbins22 (SSRT); attentional flexibility, as measured on the intradimensional-extradimensional set-shift task (ID-ED), and executive planning, as measured on the Stockings of Cambridge (SOC) task.23 A small controlled study suggested that patients with OCD and comorbid OCPD demonstrated even greater cognitive inflexibility on the extradimensional set-shift paradigm than patients with OCD without comorbid OCPD.Reference Fineberg, Sharma, Sivakumaran, Sahakian and Chamberlain3 A recent studyReference García-Villamisar and Dattilo24 investigating a small group of nonclinical participants with obsessive compulsive personality traits (OCPT) using similar tests found significant differences between OCPT and control participants on the Spatial Working Memory tasks, ID/ED tasks, the SOC task, and the Dys-executive Questionnaire. These results suggest that (a) a similar range of executive dysfunction is present in people with prominent OCPT as in those with OCD, and (b) a high convergence between clinical and ecological measures of executive functions in patients with compulsive disorders may explain some of the clinical difficulties they experience, especially relating to their disabling behavioral rigidity and stubbornness.

The neuropsychological profile of OCD may extend beyond deficits in executive function to include emotional processing problems. Patients with OCD and trichotillomania have been compared on multiple aspects of cognitive function,Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbin and Sahakiana25 including affective processing using the affective no/go-no test.Reference Murphy, Sahakian, Rubinsztein, Michael, Rogers and Robbins26 While patients with OCD and trichotillomania were no different at recognizing happy words, the former made more errors in processing sad or negative emotion laden words. This finding is consistent with other recent studies suggesting that people with OCD are less able than healthy controls to recognize the facial expressions of negative emotions.Reference Aigner, Sachs and Bruckmuller27–Reference Daros, Zakzanis and Recto29

The aim of the current study was to investigate the neurocognitive profile of a nonclinical sample of people fulfilling diagnostic criteria for OCPD (in the absence of major psychiatric comorbidity). We particularly wished to discover the extent to which any deficits observed in OCPD resembled the published data for OCD. We chose to use a battery of neuropsychological tasks23 in order to be consistent with published OCD/OCPD/OCPT data.Reference Fineberg, Sharma, Sivakumaran, Sahakian and Chamberlain3, Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Robbins and Sahakian21, Reference García-Villamisar and Dattilo24 We selected a similar battery of tasks as used in the previous publications, including tests of emotion recognition and processing, executive planning (SOC), and attentional set shifting (ID-ED), as well as a decision-making task (Cambridge Gamble Task [CGT]), which so far has not consistently been found to be impaired in OCD or OCPD (despite the evident decision-making difficulties observed in the psychopathology of these disorders).Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbin and Sahakiana25

Methods

OCPD participants were recruited via a screening advertisement that was e-mailed to 20,000 students at the University of Hertfordshire (Hertfordshire, UK). The advert contained modified Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) OCPD criteria, and students were asked to respond if they thought they had any of the traits. The advertisement was also placed on a Web site used by the students, in a local newspaper, and on a local radio interview. The control participants were similarly recruited via e-mail and word of mouth. Participants who responded were provided with participant information and given a minimum of 24 hours to consider participation. The protocol was approved by the local University research ethics committee, and all participants provided written consent.

Clinical assessment

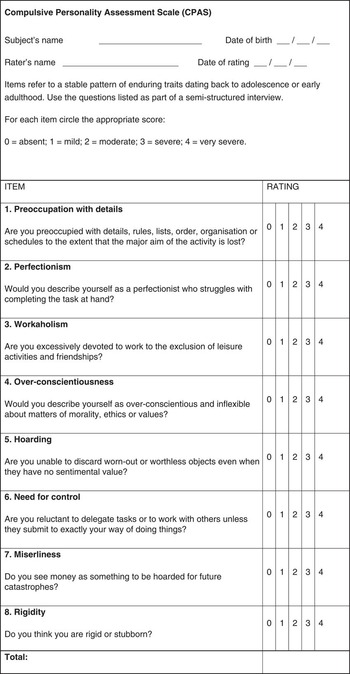

Each participant underwent a clinical assessment by psychiatrists with expertise in the assessment of OCD (NAF and GH). The assessment interview lasted 30 minutes and included administration of a brief demographic questionnaire and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI),Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Sheehan30 a structured screening interview designed to reliably identify most relevant DSM-IV mental disorders, supplemented by a semistructured clinical interview to identify other obsessive-compulsive related disorders not included in the MINI (such as body dysmorphic disorder, autistic spectrum disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, hypochondriasis, and trichotillomania). The diagnosis of OCPD was made using a semistructured clinical interview involving questions directed at each of the DSM-IV 301.4 criteria, using the published criteria as the stem question for each item. In each case, all the diagnostic criteria were endorsed either positively or negatively. In addition, participants were questioned on the DSM-IV general diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder in order to establish the extent to which the endorsed behaviors and traits impacted on the individual’s life, and to arrive at a decision as to whether a DSM-IV diagnosis was sustained. Syndrome severity was additionally measured using the observer-rated Compulsive Personality Assessment Scale ([CPAS]Reference Fineberg, Sharma, Sivakumaran, Sahakian and Chamberlain3; see Figure 1), which uses a semistructured interview to provide a quantitative measure of the extent to which each of the 8 DSM-IV or DSM-5 OCPD diagnostic behavioral/trait items is endorsed.

Figure 1 Compulsive Personality Assessments Scale (CPAS). Adapted from Fineberg NA, Sharma P, Sivakumaran T, Sahakian B, Chamberlain S. Does obsessive compulsive personality disorder belong within the obsessive-compulsive spectrum? CNS Spectr. 2007;12(6):467–482. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

Participants

Participants were aged between 18 and 65 years, and were required to have an adequate command of English. As noted above, participants recruited to the OCPD group were required to fulfill DSM-IV criteria for OCPD. Healthy controls were drawn from the same population, and attempts were made, as far as possible, to match age, gender, and IQ across the groups. For both groups, the presence of any other mental disorder, including depression, anxiety disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, OCD, obsessive compulsive related disorder, autistic spectrum disorder, anxiety disorder, depression, Tourette’s syndrome, hypochondriasis, or trichotillomania, resulted in exclusion. Participants in the control group were additionally required not to have any known history of mental illness and to score less than 5 out of a total of 32 on the CPAS, to ensure a low level of borderline OCPD traits.

A total of 59 people applied to participate in the study, and of those, 31 (52.5%) either withdrew or were not selected for participation. Of the 28 remaining, 4 were unsuitable after initial assessment owing to the presence of comorbid disorders, 2 did not have high enough OCPD scores, and 1 person expressed reservations regarding participation. Thus the final OCPD group comprised 21 participants (9 females and 12 males; mean age =26.5; SD=9.87).

We assessed 21 healthy controls; 3 did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and an additional 2 controls were later excluded because of extreme outlying data on cognitive tasks. Therefore, the control group comprised 15 participants (9 female and 6 males; mean age =23.40; SD=6.25).

Neuropsychological testing

Following clinical assessment, participants completed the computerized neuropsychological test battery in a quiet room at the University of Hertfordshire. Participants were tested on the following tasks, including some derived from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB).23

National Adult Reading Test (NART)Reference Nelson and Willison31

This is a measure of estimated “premorbid intelligence,” based on performance of reading aloud a list of irregular words. This assessment is scored according to the number of words pronounced correctly.

Facial Expression of Emotion (FEEST)Reference Young, Perrett, Calder, Sprengelmeyer and Ekman32

This computerized task assesses the ability to recognize a range of facially expressed emotions. The participants are presented with a series of standardized images of faces, each expressing an emotion, and are required to select 1 of 6 emotion names presented on the screen. The number of correct identifications is recorded. Patients with OCD and body dysmorphic disorder are known to perform poorly at recognizing negative emotions, such as anger or sadness, on this task.Reference Daros, Zakzanis and Recto29, Reference Jefferies, Laws and Fineberg33

The Famous Face Test (FFT)Reference Jefferies, Laws and Fineberg33

The famous face task investigates the processing and recognition of facial information. A set of 50 grayscale photographs of famous people is inverted and presented to the participant at a set distance for a set time. The participants are asked to keep their head upright (resist the urge to tilt the head, which may offer an advantage in recognition of the face) while verbally identifying the famous faces. Scoring is the total number of faces correctly named. Patients with BDD are superior to healthy controls at recognizing inverted faces,Reference Jefferies, Laws and Fineberg33 suggesting the existence of disorder-related processing changes that may be related to a focus on processing topographical detail, as opposed to emotional expression.Reference Jefferies, Laws and Fineberg33, Reference Feusner, Moller and Altstein34

Stockings of Cambridge Task (SOC)

The SOC is a version of the Tower of London task,Reference Shallice35 which assesses executive functioning and higher-level cognition, such as the ability to plan ahead. A set of colored balls is shown on the bottom of a computer screen. Participants are required to move them to match them up with another set of similar balls arranged at the top of the screen as efficiently as possible, ie, with the minimum number of moves. The task is repeated with varying levels of difficulty. Performance on the task is measured by the thinking time required to make initial and all subsequent moves, the number of moves required to create the target arrangement, and the number of tasks completed in the minimum number of moves. OCD patients have been shown to present with slowed planning and initial movements in the SOC task,Reference Nedeljkovic, Kyrios and Moulding36 and therefore this experiment was used to assess whether OCPD shares aspects of the same neurocognitive impairment.

Intradimensional/extradimensional set-shift tasks (IDED)

This test assesses rule acquisition and rule reversal ability, including the flexible adaptation of performance to suit the situation. Within the test, the participant is shown a pair of stimuli on the screen, composed of either a color-filled object or a line drawing. At first, the participant performs the intradimensional task, for example, choosing between 2 different shapes of the color-filled object based on trial and error and probabilistic computer feedback. After several trials, the rule governing the correct response is unpredictably changed to favor the alternative stimulus, ie, the previously correct shape no longer produces positive endorsement by the computer. Through trial and error, the participant learns the new rule, ie, to switch responding to the alternate color-filled shape. In the extradimensional switch (EDS) phase, an additional degree of complexity occurs whereby participants have to switch responding between different stimulus dimensions, eg, between color-filled objects and line drawings. Performance on the task is measured by the number of trials required to meet a criterion level of response and the number of errors made. Similar to the SOC test, the ID-ED test is known to be affected in OCD, specifically at the most difficult EDS phase of the task.

Cambridge Gambling Task (CGT)

This task investigates decision-making and risk-taking behavior in the context of gambling for rewarding “points.” Participants are required to select the location of a token hidden within a set of red or blue boxes on the screen. They are invited to gamble on how sure they are and can “bet” points. The objective is to end up with the largest number of available points. CGT performance is judged using measures of deliberation time, quality of decision making, risk-taking, and risk adjustment. The CGT task is not known to be impaired in OCD, though it is in impulse-control disorder, such as gambling disorder and alcohol dependency.Reference Lawrence, Luty, Bogdan, Sahakian and Clark37

Six Elements Test (from The Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome Battery [BADS])Reference Wilson, Evans, Emslie, Alderman and Burgess38

The Six Elements test, a component of the BADS, investigates higher-order executive functions, such as multitasking, planning, and organizing. Participants are required to tackle 3 pairs of tasks (maths, picture naming and describing 2 events) within a 10 minute time limit; there are 2 versions of each task, and the rules prohibit tackling these contiguously. Scoring is in terms of the number of tasks attempted, the number of times a rule is broken, and the time spent on each activity. To the best of our knowledge, the this test has not been used to assess executive functions in OCD; however, patients with schizophrenia and brain injury have shown deficits in this assessment.Reference Amann, Gomar and Ortiz-Gil39, Reference Evans, Chua, McKenna and Wilson40

Results

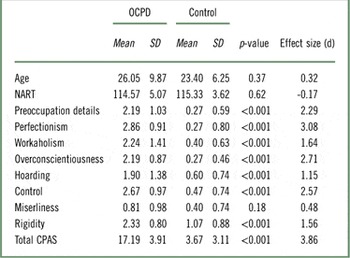

The OCPD group scored significantly higher than controls on all aspects of the CPAS at a significant level (p<.001), apart from the Miserliness item (t (34)=1.36, OCPD 0.81 [SD 0.98] vs. controls 0.40 [SD 0.74]: p=0.18, Cohen’s d=0.48), which supports the validity of the diagnostic grouping. The groups did not differ significantly in the NART IQ (see Table 1).

Table 1 Compulsive Personality Assessment Scale (CPAS) scores and background data for the OCPD group (n = 21) and controls (n = 15)

FEEST and Famous Faces Tasks

A significant between-group difference emerged on the FEEST task, with a relative failure in the OCPD group to recognize 1 expression (surprise) out of a total of 6 different expressions (t (34) –2.67, OCPD 8.29 [SD 1.01] vs. controls 9.13 [0.83]: p=0.01, Cohen’s d=–0.92). The Famous Face task also showed a numerical between-group difference with OCPD subjects naming fewer, although this marginally failed to reach significance (t (34) –1.93, OCPD 26.95 [SD 8.80] vs. controls 32.67 [SD –8.72]: p=0.06, Cohen’s d=–0.67).

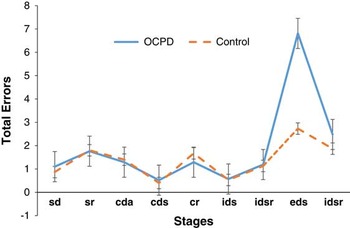

Cognitive Flexibility/Intradimensional/Extradimensional Set-Shift

The OCPD group made more EDS errors than controls (t (34)=2.33, OCPD 6.05 [SD 6.37] vs. controls 2.73 [SD 1.16]: p=0.03, Cohen’s d=0.69). Similarly, the OCPD group needed more trials to reach criterion on Stage 8 (t (34)=2.27, OCPD 6.81 [SD 8.10] vs. controls 2.73 [SD 1.16]: p=0.03, Cohen’s d=0.67) and made more total errors (adjusted) items (t (34)=2.06, OCPD 19.38 [SD 14.45] vs. controls 12.40 [SD 4.87]: p=0.05, Cohen’s d=0.62). No differences emerged for any pre-EDS stages (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Mean errors at each of the Intradimensional-Extradimensional stages (1–9); OCPD (n=21) vs healthy controls (n=15). sd = simple discrimination; sr=simple reversal; cda=compound discrimination adjacent; cds=compound discrimination superimposed; cr=compound reversal; ids=intradimensional shift; idsr=intradimensional shift reversal; eds=extradimensional shift; edsr=extradimensional shift reversal. Error bars=SE.

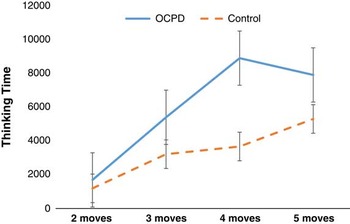

Stockings of Cambridge (SOC)

The SOC task showed that the OCPD took longer than and controls for initial think time, and this was significant at 3 moves (t (34)=2.03, OCPD 5415.24 [SD 4367.44] vs. controls 3224.43 [SD −1955.81]: p=0.05, Cohen’s d=0.63) and 4 moves (t (34) 3.35, OCPD 8925.17 [SD 6785.45] vs. control 3680.23 [SD 1984.51]: p< 0.001, Cohen’s d=1.01; see Figure 3). There was also a nonsignificant trend toward a difference in mean subsequent thinking time on 4 moves (t (34) 1.80, OCPD 1124.58 [SD 2161.54] vs. controls 238.62 [SD 523.16]: p=.08, Cohen’s d=0.54).

Figure 3 Mean initial thinking time (Msec) on the Stockings of Cambridge task for OCPD (n=21) vs. healthy controls (n=15). Error bars=SE.

Cambridge Gambling Task (CGT)

No significant between-group differences emerged on any outcome measure of the CGT.

Six Elements Test (from the BADS)Reference Wilson, Evans, Emslie, Alderman and Burgess38

The Six Elements test revealed similar mean scores for both the OCPD and control groups (raw score t (34)=–.29, OCPD 5.63 [SD 0.62] vs. controls 5.69 [SD 0.63]: p=.78, Cohen’s d =–0.10 and profile score t (34)=–.48, OCPD 3.69 [SD 0.63] vs. controls 3.77 [SD 0.44]: p=.64, Cohen’s d=–0.15).

Discussion

Overall, these findings are consistent with the notion that OCPD shares a similar range of executive dysfunction with compulsive disorders such as OCD, in terms of cognitive inflexibility and impaired executive planning, and that the characteristics of the impairment might explain some of the associated clinical difficulties, such as behavioral rigidity, perfectionism, and slowness.

As expected, clinical assessment with the Compulsive Personality Assessment Scale revealed significantly higher scores on rigidity, preoccupation with details, perfectionism, workaholism, over-conscientiousness, hoarding, and need for control, with our OCPD and control participants differing significantly on these items. This finding reinforces the strength of these specific characteristics as markers of OCPD.Reference Eisen, Coles and Rasmussen17 Miserliness was the only OCPD trait that was significantly higher in the OCPD group. The DSM-IV and DSM-5 definition of OCPD includes 2 behavioral items not included in the International Classification of Diseases Version 10 (ICD-10) definition, namely difficulty discarding (hoarding) and miserliness—both of which have been difficult to validate within the definition of OCPD.Reference Ansell, Pinto, Edelen and Grilo41, Reference Mataix-Cols, Frost and Pertusa42 Our results are consistent with the argument questioning the ongoing inclusion of miserliness as a reliable diagnostic criterion for OCPD.

Analysis of set-shifting ability on the ID-ED task showed that OCPD participants were significantly and substantially impaired on measures related specifically to the EDS. OCD patients are recognized to show robust deficits restricted to this domain within the task.Reference Fineberg, Chamberlain and Goudriaan19 Moreover, a recent study found that the EDS deficit observed in a group with OCD comorbid with OCPD exceeded that of “uncomplicated” OCD,Reference Fineberg, Chamberlain and Goudriaan19 suggesting that overlapping pathophysiology existing in each disorder summates in the comorbid group. Aside from OCD and OCPD, the EDS deficit has been found in many mental disorders, including eating disorder,Reference Roberts, Tchanturia and Treasure43 BDD,Reference Jefferies, Laws and Fineberg44 and schizo-OCDReference Patel, Laws and Padhi45—all disorders that show a high comorbidity with OCPD, though interestingly, not so far seen in those with trichotillomania.Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbin and Sahakiana25 EDS impairment has been postulated as a neurocognitive marker of cognitive inflexibility and a key component of behavioral compulsivity.Reference Fineberg, Chamberlain and Goudriaan19

How then might this set-shifting deficit contribute toward the phenomenology of OCPD? Extreme perfectionism affecting task completion; excessive devotion to work; and being overly inflexible, stubborn, rigid, judgmental, and conscientious can each be linked to a central deficiency in flexibly shifting thoughts and behavior from one topic or activity to another, in response to changing environmental contingencies. Interestingly, patients with OCD may also use more rigid moral reasoning in response to impersonal moral dilemmas, showing a thinking style characterized by reduced cognitive flexibility, demonstrating the convergence between clinical and ecological measures of cognitive inflexibility across diagnostic group controls.Reference Whitton, Henry and Grisham46

Consistent with previous findings in the OCD literature,Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Robbins and Sahakian21, Reference Kashyap, Kumar, Kandael and Reddy47 participants with OCPD also differed from healthy controls on the SOC executive planning task, with deficits seen in the mean initial and subsequent thinking times that were restricted to the higher levels of task difficulty. This finding suggests that OCPD patients, along with OCD patients,Reference Nedeljkovic, Kyrios and Moulding36 have a deficit in planning ahead, which indicates that they think for much longer before attempting a complex task. Such deficits may well become manifest in OCPD phenomenology; indeed, interference in task completion represents a diagnostic criterion for OCPD. According to the DSM-5, such slowness is directly linked to the need to complete the task to a “perfect” standard. A post-hoc analysis of our the data further investigated this relationship, revealing a significant correlation between perfectionism scores and SOC mean initial thinking time at 3 moves (r (36)=0.44, p=0.007). Thus, our results are consistent with such an account, ie, that the increased thinking time invested in executive planning represents the prioritization of the perfect result over timeliness. Further research is, however, required to test whether executive slowing is determined by a perceived need to achieve perfection or vice-versa. Other DSM-IV and DSM-5 OCPD criteria, including difficulty discarding unused items, a reluctance to delegate tasks, and miserliness, may also result from a weakness in planning capacity and too much time spent considering all the information before acting.

Similar to several studies in OCD,Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbin and Sahakiana25, Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg and Menzies48 no significant impairment in decision-making or risk-taking was found on the CGT. No impairment emerged on the BADS tests. In contrast, the FEEST showed a single significant difference between OCPD and controls on the surprise item, which may simply represent a chance finding, but unlike OCD, no differences were found in recognizing “negative” emotions such as fear, anger, and disgust.Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbin and Sahakiana25, Reference Aigner, Sachs and Bruckmuller27–Reference Daros, Zakzanis and Recto29 These results suggest that OCPD may be associated with relatively less difficulty in emotional processing than OCD. In addition, the OCPD group did not show superior face recognition on the FFT, despite scoring highly on the CPAS item that measures attention to detail. This finding contradicted our expectation and suggests that the greater skill on the FFT seen in BDDReference Jefferies, Laws and Fineberg33 may relate to other aspects of the disorder, such as a practice effect from habitually examining faces.

Taken together, the results of this study are consistent with an overlapping cognitive inflexibility and executive planning impairment that is shared across OCPD and OCD, and in the case of cognitive inflexibility, is shared also with some other compulsive disorders such as eating disorder,Reference Tchanturia, Anderluh and Morris49 body dysmorphic disorder,Reference Jefferies, Laws and Fineberg44 and schizo-OCD.Reference Patel, Laws and Padhi45 These impairments may constitute a neurocognitive fingerprint for compulsivity, and their clinical impact merits further clarification. Interestingly, OCPD subjects appeared relatively unimpaired on tasks of emotional processing, highlighting a potential area of difference with OCD and other obsessive compulsive and related disorders, such as BDD, where impaired recognition of negative expressions has been reported.Reference Corcoran, Woody and Tolin28 Importantly, in our OCPD sample, the neurocognitive dysfunction was observed in a nonclinical group of subjects who were not receiving any treatment whatsoever, and therefore cannot represent a confound of treatment. In the case of OCD, similar EDS deficitsReference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbin and Sahakiana25 and possibly SOC changesReference Vaghi, Hampshire and Fineberg50 are also seen in unaffected first-degree relatives, and are thus thought to represent vulnerability markers, involving changes in structure and function within cortico-striatal neurocircuitry.Reference Fineberg, Robbins and Bullmore51 It would therefore be interesting to investigate the extent to which the relatives of subjects with OCPD demonstrate similar deficits.

Limitations

We aimed to identify, as far as possible, a relatively “pure” form of non-comorbid OCPD. We employed an extensive screening test and interview, and excluded any individuals who might present criteria for major mental disorders, including, for example, major depressive disorder, OCD, body dysmorphic disorder, autistic spectrum disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, hypochondriasis, and trichotillomania. Given that we were assessing a treatment-seeking group of individuals, we consider it unlikely that, for example, significant depressive symptoms would have affected our results.

Recruiting participants in this category presented a challenge, and therefore the number of participants was small. Future research should anticipate this difficulty, and provide enough time to recruit a larger number of participants.

The choice of neurocognitive task mainly focused on domains known to be affected in OCRDs that are recognized as candidate transdiagnostic markers of compulsive behavior.Reference Fineberg, Chamberlain and Goudriaan19 Deficits on these tasks also occur in disorders classified outside the OCRD grouping. Systematic mapping of a broader range of compulsive disorder using a comprehensive battery of neurocognitive tasks could help parse compulsivity across different disorders.

We have hypothesized mechanisms by which the deficits might influence the clinical phenomenology of OCPD and other OCRDs. However, the functional impact of these neurocognitive impairments still remains to be established with any degree of certainty. The development of transdiagnostic rating scales for functional aspects of clinical compulsivity, such as the Cognitive Assessment Instrument of Obsessions and Compulsions 13 (CAIOC-13), would represent a relevant advance in this area.Reference Dittrich, Johansen and Fineberg52

Conclusions

This study contributes to the understanding of the neurocognitive basis of compulsivity across diagnoses. We have identified deficits in laboratory-based measures of cognitive flexibility and executive planning as significant findings in OCPD, which may potentially explain elements of the psychopathology and underpin disorder-related functional impairment. The neurocognitive profile for OCPD, in the absence of major psychiatric comorbidity, strongly resembled that seen for OCD. The results may be interpreted to support the classification of OCPD together with the OCRDs in the forthcoming WHO ICD-11 classification.

Disclosures

In the past 12 months, Naomi Fineberg has received research support from Jannsen, the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the UK Medical Research Council and the UK National Institute of Health Research. She has received financial support to attend scientific meetings from the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the British Association for Psychopharmacology and the World Health Organization and speaker fees from the British Association for Psychopharmacology and the College of Mental Health Pharmacists. She has received royalties from Taylor and Francis and Oxford University Press. Grace Day, Nica de Koenigswarter, Samar Reghunandanan, Sangeetha Kolli, Kiri Jefferies-Sewell, Georgi Hranov, and Keith Laws have nothing to disclose.