Introduction

Munchausen syndrome (MS) was characterized by Richard Asher in 1951, describing patients who falsified illness and sought medical help in several different locations for long periods of time. Most of Asher’s original cases resembled organic emergencies of several types: abdominal (laparotomophilia migrans), haemorrhagic (haemorrhagica histrionica), and neurological (neurologica diabolica).Reference Asher1 These recounts of illness, “dramatic and untruthful,” were compared to those of the “Baron of Munchausen,” a character created in 1785 by writer Rudolf Erich Raspe and based on German-born baron Hieronymus Karl Friedrich Freiherr von Münchhausen (1720–1797), who would often tell exaggerated tales of impossible achievements. Currently, MS is often used interchangeably with the term “factitious disorder imposed on self” (FDIS); however, the correct definition of MS would be of a particularly severe and chronic presentation of FDIS.Reference Yates and Feldman2

Factitious disorders have been reported in literature as a separate entity from hysteria (currently, conversion disorder) and malingering since the 19th century, the earliest being by Hector Gavin in 1838, and have been stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders since its third edition (DSM III) in 1986.Reference Gavin3 However, there were still be many cases of deception likely due to factitious illness, which have been described as hysteria or malingering throughout the medical history.Reference Kanaan and Wessely4 More recently, MS has arisen in a new technological context, generating terms like “Munchausen syndrome by phone” and “Munchausen syndrome by internet.”Reference McCulloch and Feldman5, Reference Pulman and Taylor6 Table 1. highlights the most important aspects whenever distinguishing factitious disorder from other more common psychiatric disorders. Ganser syndrome was not included in this discussion, as it seems to be a rather unspecific manifestation of either a psychiatric disorder or malingering.Reference Knobloch7

Table 1. The Differential Diagnosis of Factitious Disorder

In 1977, Roy Meadow described “a sort of Munchausen syndrome by proxy,” with two families in which parents portrayed their children as ill by causing intentional harm and further seeking medical assistance for them. Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) describes a type of abuse in the form of caregiver-fabricated illness, in which the perpetrator is diagnoses with FDIA.Reference Meadow8, 9

Currently, the recommendation is that the term MSBP should be used to define the abuse itself, whereas the psychopathology of the perpetrator is referred to as FDIA. When addressing the abuse, centring the problem in the victim, the appropriate term is “paediatric condition falsification” or “medical child abuse.”Reference Meadow10, Reference Flaherty and MacMillan11

According to the 5th edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5), FDIA is a psychiatric condition of the perpetrator, who deceives to portray the victim as ill, impaired, or injured, even when there are no clear external rewards. The perpetrators put their psychological needs over the needs of the victim, resulting in the abuse.12 The current International Classification of Diseases by the World Health Organization (ICD 10) contemplates factitious disorder (F68.1) as a synonym to MS. There is no separate classification for MSBP or FDIA. On the other hand, the ICD 11, which is already online but will be only in effect by 2022, delineates the difference between FDIS (6D50) and FDIA (6D51).

The prevalence of MSBP is unknown, likely due to the deception caused by the perpetrators. The DSM 5 estimates that among patients in hospital settings, about 1% meet the criteria for factitious disorder.12 It is widely thought that MSBP is significantly underdiagnosed and therefore underreported.9, Reference Schreier and Libow13

The victims are mostly children, but can also be elderly or otherwise vulnerable people, and may be directly harmed by the abuser’s falsifications or indirectly harmed by undergoing unnecessary evaluations and invasive medical interventions. For children, missing developmental opportunities and being kept out of the school setting are also part of the abuse.9 The victims often consider themselves as ill and may reveal anxieties about their diagnosis. In older children or adults, FDIS might be comorbid.14

Certain characteristics are common between most perpetrators. They are predominantly female, and, in cases where the victim is a child, the perpetrator is usually the mother. She is articulate, socially adept, and manipulative; she spends plenty of time in the hospital and is familiar with medical terminology; she may have had prior training in the medical field (nurse, medical technician, social worker, etc.); she may have a history of similar symptoms as the current fabrication in the victim; she is friendly toward the staff; she may act devout and portray the victim as being dependent on her; she may have a history of abuse as a child, substance abuse, or self-destructive behavior; she may have a coexisting personality disorder (usually DSM IV Cluster B: Antisocial, Borderline, Histrionic, and Narcissistic) but does not necessarily have a psychiatric diagnosis.9, Reference Rosenberg15, Reference Leonard and Farrell16

Cases of MSBP may present as an acute situation in the hospital. However, they often have a chronic evolution, with frequent exacerbations of fabrications in a wide variety of clinical situations.14 Not only primary care doctors or paediatricians are particularly susceptible to contacting with this form of abuse, as they are the first contact with most pathological situations. Any child victim of abuse may have encounters with nurses, pharmacists, therapists, lab technologists, and many other allied professionals.

MSBP is a difficult diagnosis because of its varied clinical appearance. Any illness could be the subject of falsification, even psychiatric disorders. Common medical conditions that are induced include: allergies, asthma, diarrhoea, seizures, fever, or failure to thrive.9 Interestingly, healthcare providers play an unintentional role in cases of MSBP, by enabling the abuse and subjecting the victim to unnecessary diagnostic investigations and treatments.Reference Criddle17 The American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (APSAC) has classified the deception of MSBP into several categories of falsification (Table 2). Some victims have preexisting conditions, which are intentionally exploited by the perpetrator; in other cases, the clinical condition of the victim results from complete fabrication by the perpetrator.9, Reference Stirling, Jenny, Christian, Hibbard, Kellogg and Spivak18

Table 2. Types of Falsification in MSBP

Through this review, we hope to raise awareness among medical professionals about the varied presentations of this clinical entity, so that it may, when appropriate, be included in the differential diagnosis algorithm.

Methods

We performed a PubMed database search with the term “Munchausen syndrome by proxy.” The last date of research done on this database was December 1st, 2019. We considered all case reports written in English, with an established diagnosis or high suspicion of MSBP, published in the last 15 years prior to the date of the search (details of the database search: “Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy”[Mesh] AND (“2004/12/01”[PDAT]: “2019/12/01”[PDAT]) AND Case Reports[ptyp]).

We choose 2004 to 2019 because it was during the period when the number of MSBP scientific-related papers publication started to decrease in PubMed registry. Probably because MSBP is being less and less used in clinical and academic communities in the last 15 years. We were intentionally focused only in the description of adult perpetrators characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment, not in the child victims. Child victims studies certainly deserve much bigger attention and efforts but, unfortunately, fall outside our clinical and academic work.

The search yielded 88 results from the PubMed database. We excluded all articles which were not case reports or case studies, which did not provide sufficient data of the victim, and/or perpetrator, which were not in a setting of medical attention seeking, and cases in which the final diagnosis was not MSBP.

After screening, 54 papers fit the inclusion criteria. From these papers, we extracted information from 81 case reports regarding the victim (age, sex), the perpetrator (age, sex, relation to victim, known psychiatric diagnosis), and the clinical presentation (type of falsification, acute or recurrence in months, outcome and follow-up).

Additionally, we included relevant papers for the theoretical discussion of MSBP through the PubMed database for the term “Munchausen syndrome by proxy,” as well as a citation chaining search for papers containing relevant data for the discussion of this topic in the aforementioned papers. We included 54 extra papers through this search strategy. In total, 108 papers were included in this review. The screening and selection process is specified in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Article screening and selection process.

Results

We used 108 articles in this review. Half (54) of the articles were used for theoretical background and discussion. The other half (54) described 81 case reports of MSBP, of which data were extracted and presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Data of Included Papers

Abbreviations: A, acute; ACA, antecedents of child abuse; C, coaching; d, days; F, female; FDIS, factitial disorder imposed on self; FI, false information; I, induction; M, male; mo, months; NOS, not otherwise specified; PD, personality disorder; R, recurrent; S, simulation; wk, weeks; WI, withholding information; y, years.

Nineteen (23%) cases presented as acute cases in a medical setting. The remaining 62 (77%) were reported recurrent cases. The time period of recurrence was varied, ranging from 11 days to 11 years. In 13 (16%) cases, the period of recurrence was not specified.

Of the victims, 41 (51%) were male, 35 (43%) were female, and 5 (6%) were not reported in the papers analysed. Of the victims who were children, the mean age was 62 months (approximately 5 years). There were two cases describing adult victims, both females aged 21 and 23.

Almost all perpetrators were female, 74 (91%) in a maternal role, while in 6 (7%) gender was not reported. One paper (1%) described two perpetrators, one male and one female, the parents of the victim. It is the only paper in our study with a reported male perpetrator (Figure 2). The age of the perpetrators was not reported in 66 cases (81%). Fourteen cases (17%) reported perpetrators that supposedly were working or having interest in healthcare, but unfortunately case reports were not standardized in order to understand if this is a real or bias prevalence. Twenty-three cases (28%) had a perpetrator with a known psychiatric diagnosis, namely depression in 11 (14%) cases, FDIS in 8 (10%) cases, and personality disorders in 6 (7%) cases. Anxiety (2%), psychosis (1%), addiction (1%), bipolar disorder (1%), and conversion disorder (1%) were lesser reported. More than one third (36%) were divorced or had family conflict or abuse.

Figure 2. Sex of the victims and perpetrators.

Twelve cases (15%) had more than one type of falsification. Induction was present in 60 cases (74%), false information was present in 16 (20%), simulation was present in 9 (11%), and withholding information was present in 2 (2%), coaching was present in 7 (9%), included children playing along or being trained by the perpetrator. In four (5%) cases, the type of falsification was unknown.

As for the outcome (Figure 3), 30 cases (37%) describe separation, 11 (14%) resulted in imprisonment of the perpetrator, 10 (12%) resulted in the death of the victim, 8 (10%) described psychological or psychiatric treatment for the perpetrator, 3 (4%) reported that the victim continued to live with the perpetrator, and 1 (1%) case reported the suicide of the perpetrator. Eighteen cases (22%) lacked reporting a follow-up.

Figure 3. Reported outcome.

Discussion

The Diagnosis of FDIA and MSBP

In a systematic review of case reports, there is inevitably inconsistent reporting of variables between authors, as there is no standard format for what should be included. This can lead to misleading results. Therefore, we shall be very careful discussing our results, as they are vulnerable to various kinds of bias.

While many papers still use the term “MSBP” to describe their clinical cases, there is ongoing discussion in the literature regarding the use of “MSBP” and its interchangeability with “FDIA.” The most recent APSAC guidelines (2017) define MSBP as “abuse by paediatric condition falsification, caregiver-fabricated illness in a child, or medical child abuse that occurs due to a specific form of psychopathology in the abuser called factitious disorder imposed on another,” justifying its use due to the historic significance of the term, despite not being a formal diagnosis in the DSM or ICD.9 However, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2009) considers the term MSBP “inappropriate” as it may imply a psychiatric diagnosis and furthermore takes the focus away from the victim, suggesting the term “fabricated or induced illness spectrum,” with a more detailed description focused on the type of falsification in the abuse.14

An essential criterion in the DSM 5 for the diagnosis of FDIA is identified deception, which is conscious, carefully planned, and well concealed. The distinction between abuse in MSBP and other situations lies in the intention of the perpetrator. In MSBP, the falsification provides gains to the perpetrator, unconscious motivations which fulfil psychological needs of solitude, attachment, family status, or love. These gains might be tertiary (as often happens in some cases of malingering) as the perpetrator draws benefit from the illness, not their own, but of another (albeit induced).Reference Fishbain, Schmidt and Willis73, Reference Dansak74 However, unlike malingering, tertiary gains in FDIA usually have no monetary reward. Similarly, falsification alone is not enough to constitute MSBP, as other unspecified abuse also causes caregivers to falsify symptoms in the victim, in order to hide their abuse.9, 12

To facilitate the diagnosis, Rosenberg described the characteristics which should be met in a case of MSBP: (1) illness in a child produced by a parent or someone in loco parentis; (2) persistent presentation of the child for medical assessment and care, resulting in multiple medical procedures; (3) denial of knowledge by the perpetrator regarding the aetiology of the child’s illness; and (4) symptoms and signs stop when the child is separated from the perpetrator.Reference Rosenberg15

There is no single aetiology for the behavior of a perpetrator in MSBP, as the motivations vary among the abusers: often the hospital environment is a distraction from the difficulties in their personal lives, causing even an improvement in their relationships, namely with their partner. They gain sympathy and respect, along with a new purpose or role in life (eg, “the devoted mother”). Many enjoy having conversations in which they can show their medical knowledge.Reference Criddle17, Reference Meadow75

Several hypotheses have been presented to provide an insight into the psychopathology of perpetrators. Rand proposed a behavioral model based on a perpetrator who causes harm to discharge dysphoric affects such as anger or anxiety (drive). This behavior is accessible because the perpetrators depersonalize their victims (breakdown of internal inhibitions), and manipulate healthcare workers through their deception, thus avoiding the consequences of their abuse (neutralization of external inhibitions).Reference Rand and Feldman76 Libow and Schreier describe three categories of perpetrators based on their motivation: Help seekers use the factitious illness to communicate their own feelings of distress and usually readily accept psychotherapy; doctor addicts are obsessed with the goal of obtaining medical treatment and are typically more suspicious, antagonistic, and paranoid; active inducers cause active and direct harm and are very resistant to therapeutic interventions. It is difficult to place a perpetrator in one of these categories, as their motivations are often undisclosed. However, it can be inferred that active inducers, being the more insistent type of perpetrator, engage in more aggressive falsification behavior (perhaps induction, simulation, and coaching), whereas doctor addicts might opt for more subtle forms of falsification (false information or withholding information) without necessarily causing direct harm. On the other hand, help seekers usually only falsify for a short period of time, until the underlying reason for the falsification can be addressed—as such, they are the farthest from original MSBP abusers, as external motivations may be present for the abuse.Reference Libow and Schreier77 Adshead argues that the pathological caregiving in FDIA can be explained by attachment theory, particularly care giving and care eliciting attachment behavior, pointing insecure attachment as a risk factor for abuse in MSBP context.Reference Adshead and Bluglass78, Reference Adshead and Bluglass79

Identifying MSBP in a clinical setting is a challenge, as deception might not be evident at first glance. Doctors trust and do not question the medical history provided by caregivers, who seem concerned and unlikely to cause harm.Reference Meadow8 The difficulty lies in differentiating between genuine and fabricated illness. In fact, the two can coexist, as people with FDIA might exploit genuine illness of their victims. Almost one third of children with fabricated illness have an underlying medical condition.Reference Rosenberg15 It is not necessary, therefore, to exclude true illness to apply the diagnosis of MSBP.Reference Flaherty and MacMillan11, 14

The strange clinical presentation of the victim leads to intensive and often invasive diagnostic work-up, which facilitates the manipulation by the perpetrator and feeds their psychological needs. Additionally, multiple hospitalizations come with their own risks, as they can cause complications such as infections, which not only further harm the victim, but can further confuse the medical staff.Reference Tamay, Akcay and Kilic60, Reference Meadow75

Current guidelines are very clear on the role of the doctor in a case of suspected MSBP. The approach to any case of suspected abuse should be multidisciplinary. Firstly, a clinical history, with a chronological description of events, should be written and complete with information from family members and previous medical records. Secondly, if the victim is at risk of direct or iatrogenic harm, the situation should be reported to the appropriate authorities (eg, Child Protective Services). Although confronting the perpetrator can sometimes deter further abuse, falsification due to FDIA is unlikely to stop simply upon diagnosis and confrontation.Reference Flaherty and MacMillan11, Reference Meadow75, Reference Sanders and Bursch80 Therefore, the child and perpetrator should be separated, and healthcare professionals should evaluate the persistence of signs and symptoms in the absence of the caregiver. Psychiatric support should be sought, both for the victim and the perpetrator.9, 14

An option available to confirm abuse is covert video surveillance (CVS). CVS could potentially be lifesaving and may elicit a more open response from the abusers, leading them to confess and even try to rectify their behavior.9 However, while CVS is recommended by some authors, others view it as an unnecessary perpetuation of abuse for the sake of obtaining proof, especially when there is compelling evidence, and therefore suggest separation as the recommended approach.Reference Flaherty and MacMillan11, 14, Reference Foreman and Farsides81 On the other hand, CVS in hospitals raises very complex ethical, deontological, and even legal issues, as most healthcare systems have a pathway for child protection that should not be deviated from.

Factitious disorders during pregnancy may present an even more problematic diagnostic discussion: is it just another case of FDIS or is it an FDIA phenomenon where the pregnant woman is the perpetrator and foetus is the victim?Reference Feldman, Rosenquist and Bond82, Reference Rabinerson, Kaplan, Orvieto and Dekel83 We decided to exclude the two case reports which mentioned obstetric factitious disorder from our study,Reference Feldman and Hamilton84, Reference Jones, Delplanche, Davies and Rose85 as the endangerment of the foetus is done through self-harm, thus putting at risk the mother’s health as well—a matter which is also discussed by the authors in the respective papers. However, pregnancy can be a catalyst to shift between FDIS and future FDIA.Reference Jureidini86 Yates and Bass reported that approximately 25% of their reviewed cases mentioned a personal history of obstetric complications among the perpetrators.Reference Yates and Bass87 Therefore, a pregnant woman with a previous diagnosis of factitious disorder (FDIS or FDIA) should suggest an increased risk of obstetric factitious disorder.Reference Jureidini86

The Treatment of FDIA and MSBP

Despite most perpetrators of MSBP being the mothers of the victims, anyone in a caring role could be a perpetrator: in more rare occasions, the fathers are more likely to have MS or a somatising disorder and are described as over demanding, overbearing, and unreasonable.Reference Meadow88

The treatment of FDIA has difficulties and should be approached on a case-by-case basis. Many perpetrators have a history of family disruption and loss.Reference Bass and Jones89 In our study, the number of perpetrators who had a background of family disruption (abuse, marital, or family conflict) was close to one third (32%). Though cluster B personality disorders (borderline, histrionic, antisocial, and narcissistic) and somatic symptom disorders (including FDIS) are overrepresented in perpetrators of MSBP, often there is no definitive psychiatric diagnosis. An abuser may seem normal during the interview and strongly deny any involvement in the abuse.Reference Bursch, Emerson and Sanders90 Nevertheless, a mental health evaluation, including a standardised assessment (relationship scales questionnaires), allows for professionals to recognize specific behavioral patterns, understand their motivations, and infer acknowledgment for the abuse.9, 14, 90–92

The focus of therapy should be on the perpetrator taking accountability for their abuse. Psychological treatment (eg, narrative therapy, trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, family therapy)9, Reference Bursch, Emerson and Sanders90 has many advantages: creating a plan for the child, enabling the parents to be active participants in the care and improving the quality of life of the family.Reference Berg and Jones93

Special targets of intervention should be the siblings and father of the victim. The siblings may have been neglected during the abuse of the index child.Reference Sanders and Bursch80, Reference Bass and Glaser91 The father needs individual help to process these new findings and any possible feelings of guilt for his lack of knowledge of the abuse. Couples therapy or marriage counselling is equally important, especially in cases where the perpetrator herself is the victim of domestic abuse or marital conflict, and coparenting is the end goal of both parents.Reference Sanders and Bursch80, Reference Schreier94 In cases of reunification or lack of separation, the risk of reabuse is significant and lethality rates are higher, especially in younger children.9, 14, Reference McGuire and Feldman95, Reference Davis, McClure and Rolfe96

The diagnosis of FDIA excludes other psychiatric disorders such as psychotic disorders or delusional disorders, as in factitious disorders, the deception is carefully planned.12 However, many perpetrators are diagnosed from other psychiatric morbidities, which should be treated accordingly.9, Reference Bass and Glaser91 For instance, depression and anxiety disorders (present in 13 cases in our study) should be target of treatment with antidepressants and anxiolytic drugs for acute symptom control. Alcohol and substance abuse can also be prevalent among perpetrators, thus the need for pharmacological therapy to promote abstinence. Other psychiatric disorders comorbid with FDIA, such as FDIS, conversion disorder, as well as personality disorders (prevalent in seven cases in our study) should be object of treatment during psychotherapy.

As some perpetrators are prior childhood trauma victims themselves and may have consequently developed attachment disorders, psychotherapy should be oriented toward addressing the underlying trauma. Some studies show positive effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and oxytocin, posing as promising therapeutic options for trauma victims, but to our knowledge, no such studies have been done particularly for trauma holders with FDIA or those who have engaged in abusive behavior in MSBP context.97–101

The Prognosis of FDIA and MSBP

There is evidence of intergenerational transmission of abnormal illness behavior in the perpetrators of MSBP.Reference Bass and Glaser91 Grandmothers often support the perpetrating mothers. Children of parents with somatoform disorders are at higher risk of increased healthcare seeking and abnormal health beliefs, namely more bodily preoccupation and illness anxiety disorder, both care-seeking (eg, hypochondriasis) and care-avoiding types (eg, nosophobia). The presence of MSBP seems to be a factor in developing child illness falsification behavior and later, adult factitious disorder.Reference Bass and Jones89, Reference Marshall, Jones, Ramchandani, Stein and Bass102, Reference Libow103 The morbidity of survivors of MSBP abuse is high.Reference Davis, McClure and Rolfe96 Besides direct consequences of the abuse, there are several problems that could develop in the victim: iatrogenic disease, anxiety, somatisation, FDIS, and attachment disorders. Victims may not be aware that they were abused, especially younger children. Older children and adults are more likely to understand the abuse and may even feel loyal to their abuser. Collusion is often present among these age groups.9, 14, Reference Meadow75 Blended cases, in which both the parent and the child actively falsify illness, have been described in literature as the continuum between MSBP and MS.Reference Libow103 Waller depicted the relationship between the perpetrating mother and her child as symbiotic: while the mother fulfils her emotional needs by causing harm, this harm brings proximity, which is welcomed by the child.Reference Waller92

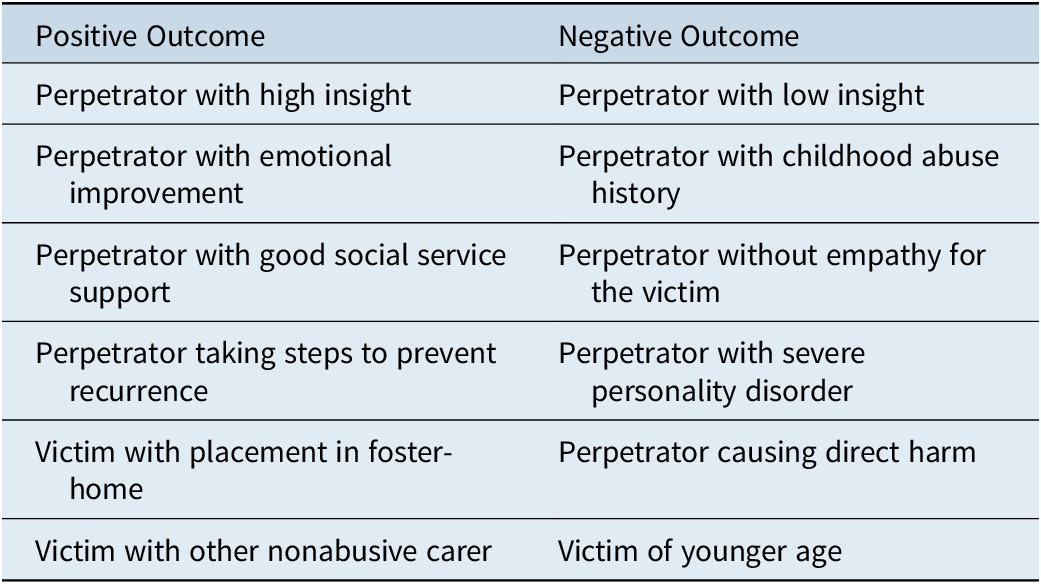

The prognosis of patients with FDIA is poor, and most cases tend to chronicity. As such, treatment and reunification failures should be expected.Reference Schreier94 From our findings, despite separation of the victim and perpetrator being the most common outcome (37%), in most reports, there was little detail into the treatment offered, if any, to the perpetrator. In 10% of cases, treatment was offered in the form of psychological or psychiatric therapy. Davis and McClure reported that approximately one-third of the children were allowed to return home after assessment.Reference Davis, McClure and Rolfe96 In our study that number was much lower (4%). We consider this a factor for poor outcome, as it poses as a high risk of reabuse. Almost one quarter of cases had no follow-up or reported outcome, which causes us to question whether appropriate action was always taken toward the perpetrators in order to ensure the safety of the victims. Few longitudinal studies have been made to assess the outcomes of successfully treated perpetrators of MSBP. However, there are some factors which have been proposed to affect the prognosis in these cases,Reference Berg and Jones93, Reference Schreier94, Reference Davis, McClure and Rolfe96, Reference Bools, Neale and Meadow104, Reference Jones105 which we have summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Factors Contributing to Prognosis in MSBP Cases

Conclusions

Strengths

This review aimed to identify the most common findings in cases of abuse in MSBP context. Based on the analysis of data provided from 54 articles regarding 81 case reports published in the last 15 years, we gained some insight into the identity and personal history of victims and perpetrators, as well as the most common methods of falsification identified in the clinical context.

These results are in accordance with prior results in the literature, further substantiating the need to identify patterns in the clinical presentation of this form of abuse.

Despite being a rare form of abuse, MSBP should be considered alongside other medical diagnoses in a clinical context. There are several models that explain the motivation behind the abuse. Regardless of the intentions of the perpetrator, the victims, who are mostly children, sustain direct (induced) and indirect (iatrogenic) consequence of the abuse. The long time periods of recurrence, multiple hospitalizations, and eagerness to help by medical personnel lead to missed occasions of diagnosis of MSBP. Therapy should approach the victim and the perpetrator, always on a case-by-case basis.

Limitations

During this research, we encountered some limitations:

The data from the case-reports are very incomplete, due to the absence of a definitive diagnosis of MSBP, and the lack of data on perpetrators, namely their motivation. Furthermore, some papers excluded, for example, those 19 articles not written in English, could contain some interesting input to our review.

The search method may have caused some selection bias, as some case reports published in the databases we searched were not identified as such and were probably missed as a consequence. Therefore, the size of our sample is nonrepresentative of the universe. We are afraid that, due to our very limited resources, we had to make a choice, focusing in just one term during our search. Unfortunately, it was never in our plans to look for articles regarding alternative terms in our search methodology. We were only able to search for MSBP case reports published in the last 15 years in PubMed. We are aware that other authors may be interested in the equivalent terms, or in other clinical entities, or even phenomena included in the wide spectrum of child abuse.

Future Research

The elaboration of this review brought forward some questions which could elicit further research in this area.

The multigenerational transmission of factitious disorders has been explained in the literature mostly by social and familial cues. But there could be also, synergistically speaking, some genetic factors involved, which would be similarly of interest to study.

As FDIA seems to be almost exclusive of women (and among them, mothers), it would also be interesting to explore in perpetrators, the impact of sexual hormones such as oestrogens, progesterone, and even testosterone, which is regarded as a biomarker for aggressive behavior.Reference Denson, O’Dean, Blake and Beames106, Reference Glynn, Davis, Sandman and Goldberg107

On the other hand, the attachment disorder hypothesis should also be explored with neuroendocrine studies looking for possible correlations with oxytocin and even prolactin metabolism, two very important hormones in the interactions between the infant and the caregiver.Reference Cochran, Fallon, Hill and Frazier108

Finally, while there is no doubt on the importance of individualized psychotherapy for perpetrators with FDIA, no efficient pharmacological treatment has been proposed. We believe that further biological-oriented studies will open opportunities for more specific pharmacological treatment of such a fascinating disorder.

Reviews like this one open the possibility of creating international multicentre databases of cases of abuse in MSBP context. Through these databases, it would be interesting to pool data on perpetrators, in order to understand whether a certain profile of perpetrator uses a specific type of falsification to induce the illness.

Last but not least, we would like to invite all interested readers to join efforts in the creation of an international database, with inclusion of all single case reports, in order to collect more information regarding this fascinating topic, in a multidisciplinary and biopsychosociocultural approach.

Acknowledgments

Nuzhat Abdurrachid would like to acknowledge her family and friends for support.

Disclosures

Nuzhat Abdurrachid and João Gama Marques have nothing to disclose.